Summary

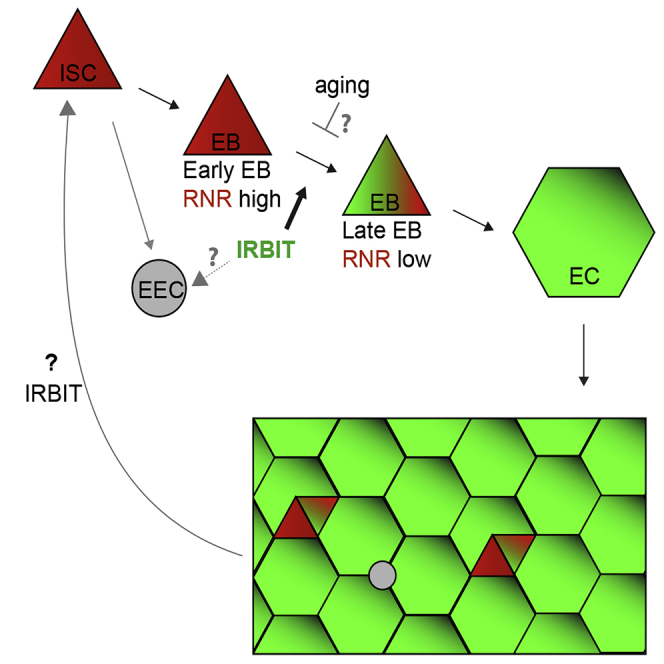

The maintenance of the intestinal epithelium is ensured by the controlled proliferation of intestinal stem cells (ISCs) and differentiation of their progeny into various cell types, including enterocytes (ECs) that both mediate nutrient absorption and provide a barrier against pathogens. The signals that regulate transition of proliferative ISCs into differentiated ECs are not fully understood. IRBIT is an evolutionarily conserved protein that regulates ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), an enzyme critical for the generation of DNA precursors. Here, we show that IRBIT expression in ISC progeny within the Drosophila midgut epithelium cells regulates their differentiation via suppression of RNR activity. Disruption of this IRBIT-RNR regulatory circuit causes a premature loss of intestinal tissue integrity. Furthermore, age-related dysplasia can be reversed by suppression of RNR activity in ISC progeny. Collectively, our findings demonstrate a role of the IRBIT-RNR pathway in gut homeostasis.

Subject Areas: Cell Biology, Stem Cells Research, Developmental Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

IRBIT is required for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium

-

•

IRBIT inhibition of RNR ensures proper intestinal stem cell differentiation

-

•

Suppression of RNR in intestinal stem cell progeny reverses age-related dysplasia

Cell Biology; Stem Cells Research; Developmental Biology

Introduction

Like the mammalian intestinal epithelium, the Drosophila midgut epithelium is continually renewed by controlled intestinal stem cell (ISC) proliferation and differentiation of their progeny (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006, Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006). ISC proliferation is finely tuned by diet, aging, and the microbiota ecosystem (Choi et al., 2011, Koehler et al., 2017, O'Brien et al., 2011), using many of the same biochemical pathways that control intestinal epithelial renewal in mammals (Pasco et al., 2015). In addition to self-renewal, ISC division produces two types of postmitotic progeny: enteroendocrine cells (EECs) and enteroblasts (EBs). EBs ultimately mature into adult enterocytes (ECs) (Figure 1A). Mature ECs form the absorptive and protective surface of the epithelium (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006, O'Brien et al., 2011, Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006, Zhai et al., 2017). Although ISC maintenance and proliferation has been extensively studied, the signals that mediate transition of ISC progeny into terminally differentiated absorptive ECs are not fully understood. The decision of ISC progeny to undergo differentiation is dictated by various intrinsic and extrinsic cues including nutrient availability and the presence of a physical damage in the intestinal epithelium and relies upon the level of interaction between ISC daughter cells. Daughters exhibiting low-level Notch signaling suppress Ttk69 transcriptional repressor and develop into EECs (Beehler-Evans and Micchelli, 2015, Wang et al., 2015, Zeng and Hou, 2015). Daughters with tight connections and strong Notch signaling commit to the EB lineage (O'Brien et al., 2011, Zhai et al., 2017). The process of terminal differentiation of the EB into the absorptive EC is not completely understood but was shown to require the activity of several transcription factors, including Sox21a and GATAe (Zhai et al., 2015, Zhai et al., 2017) (Figure 1A). The delay or block in terminal EC differentiation leads to accumulation of undifferentiated EBs, either causing dysplasia, which can physically damage tissue integrity, or even neoplasia, with mosaic expression of various genes implicated in cancer progression (Chen et al., 2014, Chen et al., 2016, Hsu et al., 2014, Krausova and Korinek, 2014, Zhai et al., 2015).

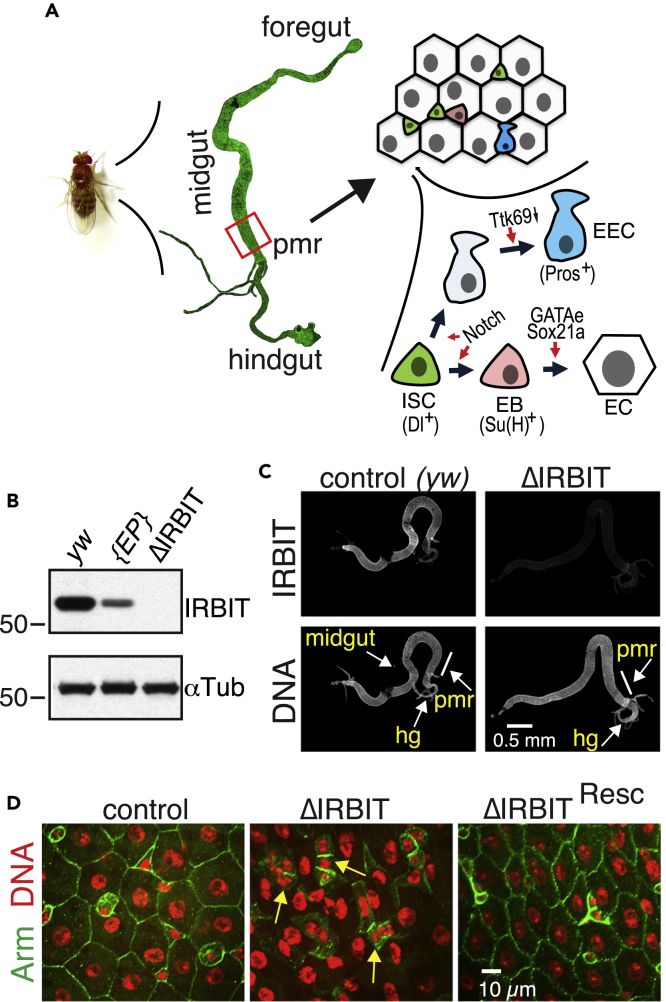

Figure 1.

IRBIT Is Required for Intestinal Epithelial Maintenance

(A) A scheme of digestive system in Drosophila and differentiation routes of intestinal stem cells (ISC) within posterior midgut region (pmr). EB, enteroblast; EC, enterocyte; EEC, enteroendocrine cell.

(B) Total lysates of adult control (yw), P[EP]G4143, and ΔIRBIT flies were analyzed by western blot for the presence of IRBIT. αTubulin was used as a loading control. The position of protein markers (shown in kDa) is indicated on the right.

(C) Guts of control and ΔRBIT flies stained with IRBIT antibodies and Hoechst 33342 (DNA). Posterior midgut region (pmr) is indicated.

(D) Disruption of ΔIRBIT midguts architecture. Midguts of 12-d-old control (yw) ΔIRBIT and ΔIRBITResc flies stained for Armadillo (Arm, adherens junctions, green) and DNA (red). Arrows denote clusters of cells with small nuclei.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) is a critical enzyme in the pathway for the de novo dNTP synthesis, as it makes dNDPs from corresponding ribonucleotide precursors via a remarkably complex mechanism (Ahluwalia and Schaaper, 2013, Fairman et al., 2011). RNR consists of two subunits: the R2 subunit provides the free radical that is necessary for R1 subunit-mediated reduction of ribonucleotides. In addition to the catalytic site, R1 subunit has two nucleotide-binding sites that control the state of R1, and one of them, the A-site, monitors R1's overall activity. RNR is active when ATP binds to the A-site, whereas dATP binding inhibits the enzyme (Ahluwalia and Schaaper, 2013). As the A-site has low affinity for ATP/dATP, the concentrations of dATP required to inhibit RNR usually exceed physiological dATP levels inside dividing cells. We have previously shown that an evolutionarily conserved protein IRBIT (IP3-receptor-binding protein released with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate) controls RNR activity by locking the R1 subunit in an R1∗dATP inactive state, in the presence of physiologically relevant dATP concentrations (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014). The dNTP pool in HeLa cells is sensitive to IRBIT levels, but the organismal importance of IRBIT-dependent RNR regulation remained unknown, although we speculated that it could control cell-cycle progression and exit (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014). High dNTP levels, produced by RNR, are critical for cells to transit through S phase. During Drosophila embryogenesis, the maternal pool of dNTP is only sufficient for the first 10 divisions, after which endogenous RNR activity becomes indispensable (Djabrayan et al., 2019, Song et al., 2017). On the other hand, overexpression of RNR appears to be detrimental for normal progression of embryogenesis (Song et al., 2017), suggesting that there must be mechanisms to curtail RNR activity during cellular specialization. Because dNTP abundance is critical for S phase progression and because the suppression of the cell cycle could regulate differentiation (Djabrayan et al., 2019, Jiang and Kang, 2003, Ruijtenberg and van den Heuvel, 2016, Vastag et al., 2011), we decided to test whether manipulation of the RNR activity could affect cellular decision between proliferation and differentiation.

Here, we tested the function of IRBIT in tissue homeostasis, particularly the proliferation and differentiation of ISCs and maintenance of the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. We found that the IRBIT-RNR pathway is essential to ensure correct differentiation of ISC progeny. We show that conserved transcriptional factor GATAe stimulates IRBIT expression in postmitotic ISC progeny to inhibit RNR and promote differentiation. The intestines of flies lacking IRBIT demonstrate dysplasia, with profound accumulation of undifferentiated ISC progeny. Additionally, we provide evidence that the GATAe-IRBIT-RNR pathway may become dysfunctional as flies age, resulting in characteristic accumulation of undifferentiated ISC progeny. Such dysplasia can be successfully reversed by specifically inhibiting RNR in the ISC progeny. Collectively, these findings show that suppression of RNR activity by IRBIT is an indispensable mechanism that allows the ISC daughter cell to proceed toward differentiation and to maintain intestinal tissue homeostasis.

Results

IRBIT Is Required for Intestinal Epithelial Maintenance

There are two Drosophila genes that encode proteins with significant sequence similarity to vertebrate IRBIT: AhcyL1 (CG9977, IRBIT) and AhcyL2 (CG8956, IRBIT2). Only IRBIT but not IRBIT2 bound RNR efficiently (Figure S1A), suggesting that IRBIT controls RNR in Drosophila. Notably, only IRBIT but not IRBIT2 mRNA was expressed in the midgut during embryogenesis (Figure S1B). Thus, both protein-protein interactions and localized expression prompted us to focus on IRBIT control of RNR regulation in the midgut. We generated two null alleles of IRBIT and we termed flies bearing both as “ΔIRBIT” (Figure S1C). We stained digestive tracts isolated from adult female flies with anti-IRBIT antibodies, confirming IRBIT protein expression in the midgut, as well as its absence in ΔIRBIT flies (Figures 1B and 1C). To verify the specificity of IRBIT loss-of-function phenotypes, we introduced a genomic rescue fragment to a defined docking site in the ΔIRBIT background and termed these flies as “ΔIRBITResc.” ΔIRBIT flies expressed non-functional RNA and lacked IRBIT protein, whereas ΔIRBITResc flies expressed IRBIT RNA at levels similar to controls (Figures S1D and S1E).

We focused on the function of IRBIT in the female posterior midgut region of adult flies (pmr, R5 region [Dutta et al., 2015]) because this tissue has a well-characterized and relatively simple structure (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006, Miguel-Aliaga et al., 2018, O'Brien et al., 2011, Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006, Zeng et al., 2010, Zeng and Hou, 2015, Zhai et al., 2017) (Figure 1A). By 12 d post-eclosion, the ΔIRBIT pmr epithelium showed degenerate tissue with hyperplastic-like polyps (Figures 1D, S2A, and S2B), which consisted of cells with small nuclei instead of large differentiated ECs. The midguts of ΔIRBITResc flies appeared normal (Figure 1D), confirming that the defects seen in ΔIRBIT midguts result from IRBIT loss. EM ultrastructural analysis revealed that ΔIRBIT midguts have thinner peritrophic membrane (PM), an extracellular matrix barrier against microbial infection (Figure S2C). We examined peritrophic membranes from the midguts of 8-d-old axenic (free from microorganisms) flies by staining with lectin-HPA (Helix pomatia agglutinin). The PMs of ΔIRBIT's midguts were thinner than PMs of control or ΔIRBITResc flies (Figure S2D), consistent with the EM ultrastructural analysis (Figure S2C). Altogether, our results indicate that the loss of IRBIT in flies leads to formation of intestine that has weak PM and demonstrate tissue dysplasia.

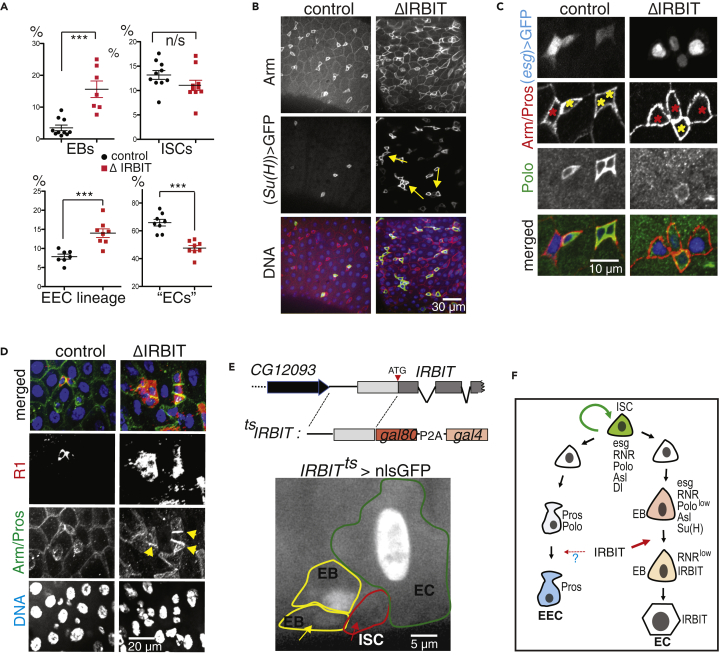

IRBIT Mediates Differentiation of the ISC Progeny

ΔIRBIT midgut dysplasia could result from increased ISC proliferation, failed transition of ISC progeny into EECs and EBs, and/or failed maturation of EBs into ECs. To test these possibilities, we determined the relative abundance of these cell types using specific GAL4 drivers (Figures 2A and S3). esg-Gal4 has a well-defined pattern in the midgut and is expressed in both ISCs and EBs, whereas the expression of Su(H)GBE-Gal4 is restricted to EBs. Antibodies against Delta (Dl) mark ISCs, whereas antibodies against Pros faithfully detect cells of EEC lineage (Zeng et al., 2010). To enhance our arsenal of detection tools, we additionally used antibodies against several proteins that play key functions during the cell cycle and found that antibodies against Asterless (Asl, centriole component) uniformly stain EBs and ISCs, whereas antibodies against Polo (Polo kinase, Plk) preferentially detect ISCs. Antibodies against R1 (RnrL), the large subunit of RNR, revealed that R1 is specifically expressed in both ISCs and EBs (Figure S3). Midguts of ΔIRBIT flies had normal levels of ISCs, increased numbers of the ISC progeny—EBs and immature EECs, and reduced population of ECs. This pattern would be consistent with a block or delay in the differentiation of ISC progeny (Figures 2A, 2B, S4A, and S4B). Clusters of small cells in 8-d-old ΔIRBIT pmr typically consisted of a single ISC and two to four attached undifferentiated progeny (Figure 2C). Moreover, these clusters invariably showed high levels of RNR by immunostaining (Figure 2D), suggesting that ISC progeny in ΔIRBIT midguts expressed high levels of RNR, failed to separate from mother ISCs, and failed to differentiate. By contrast, we did not observe EB groups associated with ISCs in pmr of 8-d-old control flies, indicating that EBs detach from mother ISCs and differentiate rapidly, maintaining normal homeostasis (Figures 2B–2D). Importantly, these R1+ clusters in ΔIRBIT midguts develop rapidly (as early as day 8 post eclosion) because we did not detect significant accumulation of R1+ cells in midguts of newborn ΔIRBIT flies (1 d post eclosion) (Figure S4C).

Figure 2.

IRBIT Mediates Differentiation of the ISC Progeny

(A) Cell composition in midguts. Control is in black, ΔIRBIT is in red. Quantifications of EBs (Su(H)+ cells), ISCs (Delta+ cells), cells of EE lineage (Pros+ cells), and ECs (large nuclei, Su(H)-, Delta−, Pros−) in pmr of 8-d-old female flies. (EECs: N = 8 guts; ISCs: N = 10 guts; EBs: N = 10 [control], N = 7 [ΔIRBIT] guts); (ECs: N = 10 guts). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. p Values derived from unpaired t test with Welch's correction, n/s, not significant, ∗∗∗p < 0.003.

(B) EBs were marked with GFP in 8-d-old female guts using temperature-sensitive expression system (tsSu(H): Su(H)GBE-Gal4, UAS-mCD8GFP; tub-Gal80ts). Note that the cell aggregates in ΔIRBIT (yellow arrows) are GFP+.

(C) ISC progeny in 8-d-old control and ΔIRBIT guts were marked using tsesg (esg-Gal4, UAS-nlsGFP, Gal80ts) (marker of ISCs and EBs, pseudo colored in blue) and probed for Arm (red) and Polo (marker of ISCs, green). Note a single stem cell (high Polo, yellow asterisk) with several (here: 3) attached enteroblasts (GFP+, low Polo; red asterisks) in ΔIRBIT.

(D) Accumulation of R1+ cells in ΔIRBIT. Eight-day-old female guts stained for Arm (green), R1 (RnrL, large subunit of RNR, red), and DNA (blue).

(E) IRBIT is expressed in the ISC progeny. A genomic construct that contains a putative IRBIT promoter and its 5′UTR was fused with Gal80ts-P2A-Gal4 (tsIRBIT) and used to drive nlsGFP expression (pseudo colored in white). Note the presence of nuclear GFP in EBs (yellow circles) and ECs (green circle) but not in the ISC (red circle, red arrow). Young EB (yellow arrow) is indicated.

(F) Summary: IRBIT promotes differentiation of ISC progeny in the EC lineage.

See also Figures S3–S6.

To visualize IRBIT expression during ISC-EB-EC transitions, we used a tsIRBIT promoter (Figure 2E) to express nlsGFP (nuclear GFP) and examined the ISC niche. We found that nlsGFP was not detected in ISCs but accumulated in ISC progeny that were committed to differentiation and remained highly expressed during the EB-EC transition (Figures 2E, S4D–S4F). This pattern suggested activation of IRBIT expression in the differentiating progeny.

Of note, we observed a similar distribution of IRBIT in mouse jejunum (middle part of the small intestine), with high levels in differentiated ECs but low levels in the ISC niche (Haber et al., 2017) (Figure S5), suggesting that IRBIT may play a similar role in mammalian ISC differentiation.

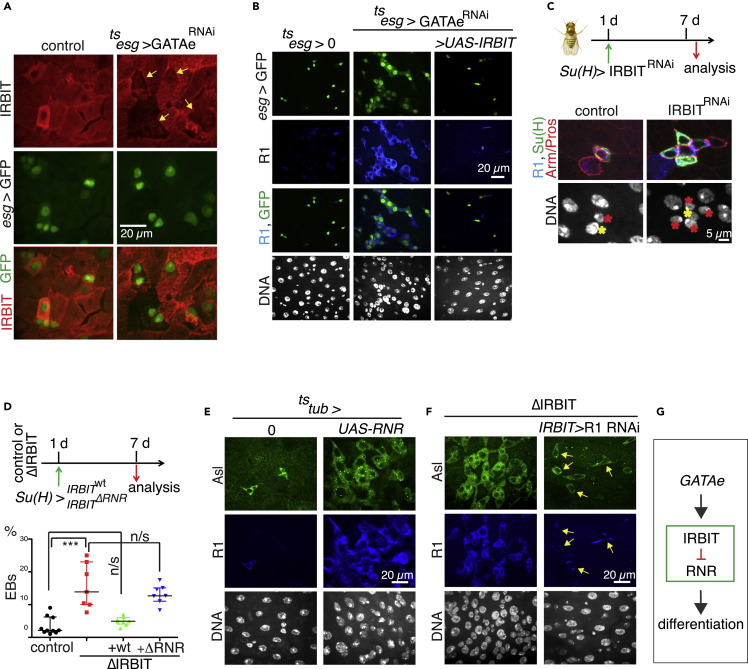

GATAe Stimulates IRBIT Expression to Suppress RNR and to Allow Differentiation of the ISC Progeny

We next tested whether IRBIT expression is controlled by known transcriptional regulators of ISC progeny differentiation (Chen et al., 2016, Zhai et al., 2017). We focused on GATAe, because we noted that during embryogenesis the expression of GATAe (Okumura et al., 2005) is remarkably similar to that of IRBIT. Moreover, the patterns of IRBIT and GATAe expression remain superficially similar in adult midguts, although during the ISC-EB-EC transition, GATAe expression commences earlier than IRBIT and can be detected in ISCs (Figure S6). Knockdown of GATAe in Esg-positive cells (ISCs and EBs) reduced IRBIT expression, with concomitant accumulation of undifferentiated progeny showing high R1 expression (Figures 3A, 3B, and S7A), suggesting that GATAe is a transcriptional regulator of IRBIT. Although the minimal IRBIT promoter (Figure 2E) does not contain “classical” GATAe motif (WGATAR) (Okumura et al., 2005), GATAe stimulates its activity (Figure S7B), indicating that either there is a yet unidentified GATAe motif or/and that GATAe stimulates IRBIT transcription via another transcription factor(s) that lies downstream of GATAe. Importantly, IRBIT overexpression rescued the phenotypic defects in GATAeRNAi, indicating that IRBIT is an important downstream target of GATAe in the intestine (Figure 3B). Interestingly, a phospho-mimetic IRBIT mutant that presumably is a much more potent R1 inhibitor (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014) rescues GATAe knockdown even better than the IRBITwt (Figure S7A), suggesting that phosphorylation of dIRBIT plays an important role during EB maturation.

Figure 3.

GATAe Stimulates IRBIT Expression to Suppress RNR and to Allow Differentiation of the ISC Progeny

(A) GATAe is required for IRBIT expression in the ISC progeny. The expression of GATAe was silenced with RNAi in the progeny using tsesg for 4 d, and the midguts were stained with IRBIT antibodies. IRBIT expression of IRBIT was reduced in esg+ cells (yellow arrows).

(B) IRBIT is a downstream target of GATAe. The expression of IRBIT was induced in GATAe-silenced cells for 7 d (tsesg, UAS-GATAeRNAi, UAS-IRBIT). Note that midguts with reduced GATAe develop RNR+/esg+ dysplasia, which is rescued by overexpression of IRBIT.

(C) IRBIT functions cell autonomously in EBs. Expression of IRBIT was silenced in EBs (tsSu(H), UAS-IRBITRNAi) for 7 d, and the accumulation of EBs was monitored by GFP+ cells. Note that IRBIT-silenced EBs (red asterisks) remain attached to mother ISC (yellow asterisks).

(D) Quantifications of EBs in pmr of 7-d-old ΔIRBIT flies rescued with tsSu(H)>IRBIT or tsSu(H)>IRBITΔRNR. N = 7–8; error bars represent mean ± SEM. p Values derived from the Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn's multiple comparison test, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(E) Overexpression of RNR mimics ΔIRBIT phenotype. The expression of RNR (both R1 and R2 [Rnrs]) was induced for 5 d using tstub expression system (tub-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts). Note accumulation of progenitor cells (Asl+).

(F) Suppression of RNR bypasses the requirement for IRBIT in the midguts. The expression of RNR (R1) was silenced in ΔIRBIT midguts by RNAi for 5 d using tsIRBIT promoter. Note that the ISCs remain positive for RNR (yellow arrows).

(G) A model of GATAe-IRBIT-RNR pathway.

See also Figures S7 and S8 and Table S1.

Genetic manipulations of IRBIT specifically in EBs indicated that IRBIT acts cell autonomously in these cells to mediate their differentiation: IRBIT knockdown induced excessive EBs accumulation in the midgut, whereas IRBIT overexpression in ΔIRBIT EBs restored their normal progression through differentiation (Figures 3C and 3D). Notably, an IRBIT mutant lacking the RNR binding region (aa 53–67, IRBITΔRNR) (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014) failed to suppress the EBs accumulation in ΔIRBIT midguts (Figure 3D). In contrast, suppression of RNR activity by hydroxyurea effectively rescued the EBs number and restored the midgut integrity in ΔIRBIT (Figure S7C).

Moreover, overexpression of RNR (using tub, esg, or Su(H) drivers) resulted in ΔIRBIT-like tissue dysplasia with prominent accumulation of EBs, whereas silencing RNR using the IRBIT promoter rescued the ΔIRBIT phenotypes (Figures 3E, 3F, and S7D), strongly indicating that high levels of RNR is detrimental for differentiation and that IRBIT functions to suppress RNR in order to maintain differentiation of ISCs.

Silencing IRBIT expression by using myo1A promoter, which is expressed in EBs and in ECs, recapitulated ΔIRBIT phenotype (Figure S7E). Although we cannot rule out the possibility of additional EC-specific effects of IRBIT that influence EB maturation, our findings collectively indicate that IRBIT is expressed in EBs and that IRBIT-mediated suppression of RNR in EBs is necessary for ISC progeny differentiation (Figure 3G). Consistent with this conclusion, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of midguts further indicated that IRBIT promotes differentiation of ISC progeny (Figure S8; Table S1). Importantly, accumulation of undifferentiated progeny in ΔIRBIT midguts was not dependent on intestinal bacterial load per se, because we observed similar phenotype in axenic flies, indicating that the problem of ISC differentiation was not a result of microorganism-induced inflammation (Figure S8A; Table S1).

To further verify the function of the IRBIT-RNR pathway during the ISC-EB-EC transition we employed lineage-tracing method esg-ReDDM (Antonello et al., 2015). This approach relies on tsesg-mediated expression of short-lived (mCD8-GFP) and long-lived (H2B-RFP) proteins thus allowing time-dependent discrimination between progenitors (RFP+/GFP+) and newly formed progeny (RFP+) upon tsesg induction. Suppression of IRBIT or overexpression of RNR in progenitor cells (esg+) had detrimental effect on formation of new progeny (Figure S9). Although our study primarily focused on midguts of virgin females, we also observed the inhibitory effect of the IRBIT-RNR disruption in progenitor cells in midguts of mated females, where the rates of ISCs proliferation and differentiation are naturally elevated (Reiff et al., 2015). After 2 weeks of tsesg-ReDDM induction, midguts of virgin or mated females with disrupted IRBIT-RNR pathway in their progenitors demonstrated both accumulation of EBs and suppression of EC formation, with no apparent effect on ISCs levels (Figures 4 and S9), thus supporting our prior observations. Altogether, these results indicate that suppression of RNR by IRBIT in EBs is required for normal EB-EC transition.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of the IRBIT-RNR Pathway Results in Delayed EB-EC Transition

Left: esg-ReDDM lineage tracing method (Antonello et al., 2015). Right: Mated flies bearing esg-ReDDM and indicated transgenes were transferred to 29°C to induce both transgene activation and lineage tracing and incubated for 14 d. Midguts were isolated and stained with antibody against Polo to detect ISCs. Note that a typical configuration of the ISC surroundings in IRBITRNAi- or UAS-RNR- expressing midguts consists of one to two ISCs (Polo+, GFP+) and two to four adjacent EBs (GFP+, Polo−); only few clones also contain one adjacent differentiated ECs (Polo−, GFP−, RFP+). Clones in control midguts typically show one ISC, zero to one EBs, and one to three ECs. EBs are marked with green asterisks. See also Figures S9 and S10.

We also probed esg-ReDDM-induced midguts for both protein and mRNA abundance of IRBIT. IRBIT protein levels gradually increased during the ISC-EB-EC transition, and maximum expression was reached in newly formed ECs. Little or no IRBIT protein or its mRNA levels were detected in ISCs (Figure S10), consistent with our prior observations.

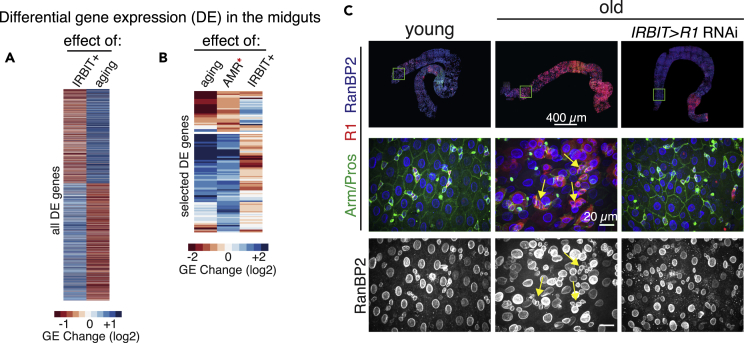

Maintenance of IRBIT-RNR Regulatory Circuit Prevents Formation of Age-Related Phenotype in the Intestine

The characteristic tissue dysplasia that rapidly develops in ΔIRBIT or in GATAeRNAi midguts is reminiscent of dysplasia in aging flies and mammals (Jasper, 2015, Regan et al., 2016), prompting us to ask whether loss of the GATAe-IRBIT-RNR pathway may underlie loss of intestinal homeostasis with age. To address this, we performed RNA-seq analysis of midguts under a variety of conditions. We measured expression genome-wide and assessed significant differential expression (DE) in pairwise comparisons. To visualize DE, we performed a hierarchical clustering analysis of log ratios of DE genes. Changes in gene expression pattern during normal intestinal aging were opposite to the changes induced by IRBIT expression in young guts (Figures 5A and S11A; Table S2), suggesting that IRBIT protects guts from age-induced changes. We also analyzed the anti-microbial response (AMR), an innate immune mechanism that helps flies control intestinal microbiota. The AMR increases with age because the frail aging epithelium becomes more susceptible to bacterial infection (Broderick et al., 2014, Chen et al., 2014, Regan et al., 2016). Gene expression changes in young ΔIRBIT midguts showed induction of genes associated with the AMR, consistent with the idea that these midguts had prematurely developed characteristics similar to age-associated frailty (Figures 5B and S11B). In addition, we also observed a significant overlap between genes whose regulation is controlled by both IRBIT and Sox21a (Chen et al., 2016, Zhai et al., 2017), suggesting that ΔIRBIT midguts might accumulate EBs at their Sox21a-dependent stage of differentiation (Figure S11C; Table S3). Because GATAe may act downstream of Sox21a (Zhai et al., 2017), these data support our model in which IRBIT is an effector of GATAe.

Figure 5.

IRBIT Is Required for Intestinal Homeostasis

(A) The loss of IRBIT mirrors aging program in the gut. Clustering of “IRBIT+” (comparison of gene expression in 8-d-old midguts control [yw] versus ΔIRBIT) and “aging” (comparison of gene expression between yw, 40 d old and yw, 8 d old) DE genes. Note the strong anticorrelation of DE between “aging” and “IRBIT+” (Pearson's r = - 0.54, p < 2.2 × 10−16, F test).

(B) ΔIRBIT midguts elicit strong AMR. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of AMR genes (Broderick et al., 2014)∗ with “IRBIT+” and “aging”-dependent genes. We performed separate hierarchical clustering for those upregulated genes (top) as well as downregulated genes (bottom). Note the anti-correlation of “IRBIT+” and the AMR response.

(C) Maintenance of IRBIT-RNR pathway prevents formation of aging phenotype in the intestine. RNR (R1) was continuously silenced in midguts by RNAi using tsIRBIT driver, and the midguts of 40-d-old flies were stained with Arm/Pros (green), R1 (red), and RanBP2 (nuclear pores, blue). Note the disappearance of dysplasia (yellow arrows) and the maintenance of normal tissue architecture.

See also Figures S9 and S11, Tables S2 and S3.

Moreover, midguts of old flies develop RNR-positive clusters of undifferentiated cells, similar to young ΔIRBIT or GATAeRNAi midguts (Figure 5C). Importantly, reducing RNR levels in the ISC progeny but not in the ISCs by using the IRBIT promoter antagonized dysplasia and restored gut tissue integrity, suggesting that the GATAe-IRBIT-RNR pathway might play an important role during intestinal homeostasis.

Discussion

IRBIT acts as an allosteric inhibitor of RNR (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014). Here, we have examined the biological importance of this mechanism using the midgut of Drosophila, a well-established system for stem cell function and differentiation. Collectively, our results indicate that IRBIT is required for maturation of EBs into ECs, and our data suggest that IRBIT acts through RNR in this process. Numerous findings lead us to this interpretation. First, IRBIT expression correlates with the EB maturation (Figure 2E). Second, IRBIT loss of function resulted in accumulation of EBs (R1+, Su(H)+ cells) (Figures 2 and 3). Third, suppression of IRBIT specifically in EB mirrored ΔIRBIT phenotype (Figure 3C). Fourth, suppression of RNR activity in ISC progeny that stalled in ΔIRBIT midguts promoted their differentiation (Figure 3F). Fifth, expression of IRBITwt but not IRBITΔRNR specifically in EBs rescued the ΔIRBIT phenotype (Figure 3D). Sixth, lineage-tracing analysis demonstrated that disrupting IRBIT-RNR pathway in progenitors (ISC/EB cells) stalls EBs at their undifferentiated state (Figure 4). Based on these observations, we propose a model in which IRBIT acts in newly formed EBs to attenuate RNR and to induce differentiation. As RNR is expressed in both ISC and EB, the absence of IRBIT inhibition of RNR activity presumably results in an ISC-level dNTP pool within EBs and delays their differentiation. Because the differentiation of EBs is critical for replenishing aging ECs, the block of differentiation in the absence of IRBIT ultimately results in frail midgut epithelium that cannot maintain strong anti-bacterial protective wall (Figures S2C and S2D), causing continuous immune response (Figure 5B).

How would IRBIT-RNR pathway mechanistically work? We propose the following scenario: activated (phosphorylated) IRBIT binds and stabilizes dATP∗RNR complex in newly formed EBs. This inhibitory IRBIT∗dATP∗RNR complex may either be targeted for degradation or restrict RNR in cytosol and prevent its nuclear translocation, as previously suggested (Fu et al., 2018). Whichever is the case, elimination of RNR from the reaction could delay the cell cycle and trigger the EB-EC transition. In the future, it would be interesting to test whether imbalancing the dNTP pool in EBs causes effects similar to disruption of IRBIT/RNR. If so, it will be important to identify targets that sense dNTP levels.

Phenotypically, IRBIT deletion (an accumulation of undifferentiated EBs without accumulation of ISCs) is similar to the phenotypes that had been previously observed in flies where expression of Sox21a, GATAe, JAK/STAT, or Dpp was silenced (Zhai et al., 2017). Our results suggest that IRBIT acts downstream of GATAe, because suppression of GATAe expression in ISC progeny resulted in accumulation of progeny with reduced IRBIT levels. Moreover, the progeny in GATAeRNAi midguts, as in the case of ΔIRBIT midguts, remained positive for R1, indicating an incomplete suppression of RNR in these cells. In addition, overexpression of IRBIT stimulated differentiation of EBs, stalled in the absence of GATAe, indicating that IRBIT is an important downstream target of this transcription factor.

The C-terminal domain of IRBIT shares significant homology to S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH, AdoHcy) hydrolase (SAHH), a crucial enzyme that is responsible for the removal of a by-product of the methylation reaction. It has been suggested that IRBIT acts as a negative regulator of canonical SAHH enzyme to regulate methionine metabolism in flies (Parkhitko et al., 2016). We have performed extensive biochemical and genetic experiments to test whether this domain could work either as an SAHH or as a natural inhibitor of SAHH. The full-length IRBIT or IRBIT's core domain did not show SAHH activity, binding to canonical SAHH, or the capacity to interact with AdoHcy agarose, indicating that IRBIT does not bind SAHH or the SAHH substrate (Figure S12). Therefore, we consider it unlikely that IRBIT acts as a dominant negative form of SAHH (Parkhitko et al., 2016). Biochemical, genetic, and histological approaches all strongly indicate that IRBIT's N terminus is critical for its function as an inhibitor of RNR (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014). We speculate that the function of the IRBIT's core domain is to form a dimer interface between the two IRBIT molecules for proper positioning of their intrinsically disordered N termini, thus allowing them to interact with IRBIT-corresponding partners that, too, typically exist as dimers, or as a complex of dimers, like RNR (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014).

As suppression of the cell cycle promotes differentiation, the choice between proliferation and differentiation may, in principle, be controlled by many cell-cycle checkpoint components (Ruijtenberg and van den Heuvel, 2016). Our results indicate that the maintenance of dNTP levels could be one such mechanism. The maturation of EBs could be viewed as a two-step process: first, Notch-mediated signals pause the ISC daughter in G1 and induce a strong Su(H) expression to commit it to the EB lineage; second, a committed EB undergoes polyploidization to fully mature into an adult EC. We initially suspected that IRBIT-mediated control of RNR in EBs might be essential for their polyploidization, i.e., switching replication/mitotic program into endoreplication. Based on our data in IRBIT-depleted HeLa cells (Arnaoutov and Dasso, 2014), we reasoned that the general speed of the replication fork progression could be the trigger point behind such mechanism and the delay in endoreplication would result in the accumulation of EBs that are not fully endoreplicated. We tested this hypothesis by an artificial reduction of RNR activity in EBs that had been accumulated in ΔIRBIT guts. To our surprise, the administration of hydroxyurea hydroxyurea (HU, a known suppressor of RNR) at 20 mM to the diet of ΔIRBIT flies that already accumulated undifferentiated progeny rapidly reduced the population of EBs. More importantly, suppression of RNR abundance in ISC progeny using RNAi, driven by IRBIT promoter, also rescued tissue dysplasia in ΔIRBIT midguts. Although it is formally possible that inhibition of RNR may have resulted in clearance of progenitors by apoptosis or by some other mechanism, we favor the idea that it is the presence of high RNR activity in EBs that is detrimental for the initial step of EBs maturation and that the decrease of the RNR activity is necessary for the decrease of Su(H)- or esg-signal and normal progression of EBs into ECs, even if endoreplication is not completed. We speculate that RNR activity within the newly formed EBs must be suppressed by IRBIT to a certain threshold in order to pause them in early S phase and to proceed with their differentiation. Once the EB is fully committed to this transition, it commences endoreplication, which also could be under the control of IRBIT, consuming endogenous dNTP produced by the residual activity of RNR. Alternatively, endoreplication of ECs may rely upon deoxynucleosides that could be absorbed from the gut lumen.

In summary, we have shown a role of IRBIT and RNR during homeostasis of midgut epithelium. IRBIT expresses in postmitotic intestinal stem cell progenitors to suppress RNR and to assist their differentiation into adult epithelial cells, a process that is essential for sustainability of the tissue during the animal's lifespan. Our study contributes toward the understanding of dysplasia, potentially facilitating development of strategies that could help containing intestinal diseases.

Limitations of the Study

We used lineage-tracing method based on stability of Histone-RFP marker. Although this approach is both straightforward and sensitive, it does not allow clonal analysis within the tissue. Therefore, MARCM-based tracing methods currently employed in the field could provide additional information, and further studies are warranted to fully understand the involvement of the IRBIT-RNR pathway during ISC differentiation.

The cues involved in the regulation of differentiation in the Drosophila midgut are complex and involve other players that likely work in concert with the IRBIT/RNR pathway to maintain homeostasis. Even though the role of RNR and IRBIT in stem cell differentiation is likely conserved within higher eukaryotes, it is also likely that the decisions for differentiation in mammalian intestine are controlled by more complex cues. Therefore, it will be interesting to probe how disruption of RNR activity in various cell types within mammalian intestine affects differentiation decisions of progenitor cells.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by 2018 NICHD DIR Director's Award. We are grateful to K. Ten Hagen and N. Rusan for reagents. We are also indebted to M. Jaime, L. Fu, L. Bao, and Y.B. Shi for their help and technical assistance. We thank M. Lilly and O. Demidov for the critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the Bloomington Stock Center at the University of Indiana and VDRC for fly stocks and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa for antibodies.

Author Contributions

A.A. conceptualized the study. A.A., K.P.H., B.O., and M.S. designed the experiments. A.A., K.P.H., H.L., M.J., and V.A. conducted the experiments. A.A., M.S., B.O., and M.D. wrote the paper.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 27, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.100954.

Data and Code Availability

All the data and methods necessary to reproduce this study are included in the manuscript and Supplemental Information. Reagent request will be readily fulfilled following the materials transfer policies of Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

The GEO accession number for the data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE109862.

Supplemental Information

DE is provided as fold changes, in log2 scale. Raw counts from the RNA-seq analyses were also provided. Gene IDs and names are based on the FlyBase annotation.

DE is provided as fold changes, in log2 scale. Raw counts from the RNA-seq analyses were also provided.

References

- Ahluwalia D., Schaaper R.M. Hypermutability and error catastrophe due to defects in ribonucleotide reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:18596–18601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310849110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonello Z.A., Reiff T., Ballesta-Illan E., Dominguez M. Robust intestinal homeostasis relies on cellular plasticity in enteroblasts mediated by miR-8-Escargot switch. EMBO J. 2015;34:2025–2041. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutov A., Dasso M. Enzyme regulation. IRBIT is a novel regulator of ribonucleotide reductase in higher eukaryotes. Science. 2014;345:1512–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.1251550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beehler-Evans R., Micchelli C.A. Generation of enteroendocrine cell diversity in midgut stem cell lineages. Development. 2015;142:654–664. doi: 10.1242/dev.114959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick N.A., Buchon N., Lemaitre B. Microbiota-induced changes in Drosophila melanogaster host gene expression and gut morphology. MBio. 2014;5 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01117-14. e01117–01114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Xu N., Huang H., Cai T., Xi R. A feedback amplification loop between stem cells and their progeny promotes tissue regeneration and tumorigenesis. Elife. 2016;5:e14330. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zheng X., Zheng Y. Age-associated loss of lamin-B leads to systemic inflammation and gut hyperplasia. Cell. 2014;159:829–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi N.H., Lucchetta E., Ohlstein B. Nonautonomous regulation of Drosophila midgut stem cell proliferation by the insulin-signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:18702–18707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109348108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djabrayan N.J., Smits C.M., Krajnc M., Stern T., Yamada S., Lemon W.C., Keller P.J., Rushlow C.A., Shvartsman S.Y. Metabolic regulation of developmental cell cycles and zygotic transcription. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:1193–1198.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D., Dobson A.J., Houtz P.L., Glasser C., Revah J., Korzelius J., Patel P.H., Edgar B.A., Buchon N. Regional cell-specific transcriptome mapping reveals regulatory complexity in the adult Drosophila midgut. Cell Rep. 2015;12:346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairman J.W., Wijerathna S.R., Ahmad M.F., Xu H., Nakano R., Jha S., Prendergast J., Welin R.M., Flodin S., Roos A. Structural basis for allosteric regulation of human ribonucleotide reductase by nucleotide-induced oligomerization. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:316–322. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Long M.J.C., Wisitpitthaya S., Inayat H., Pierpont T.M., Elsaid I.M., Bloom J.C., Ortega J., Weiss R.S., Aye Y. Nuclear RNR-alpha antagonizes cell proliferation by directly inhibiting ZRANB3. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:943–954. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0113-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber A.L., Biton M., Rogel N., Herbst R.H., Shekhar K., Smillie C., Burgin G., Delorey T.M., Howitt M.R., Katz Y. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature. 2017;551:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature24489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y.C., Li L., Fuchs E. Transit-amplifying cells orchestrate stem cell activity and tissue regeneration. Cell. 2014;157:935–949. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper H. Exploring the physiology and pathology of aging in the intestine of Drosophila melanogaster. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 2015;59:51–58. doi: 10.1080/07924259.2014.963713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.W., Kang C.M. Induction of S. cerevisiae filamentous differentiation by slowed DNA synthesis involves Mec1, Rad53 and Swe1 checkpoint proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:5116–5124. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler C.L., Perkins G.A., Ellisman M.H., Jones D.L. Pink1 and Parkin regulate Drosophila intestinal stem cell proliferation during stress and aging. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:2315–2327. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201610036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausova M., Korinek V. Wnt signaling in adult intestinal stem cells and cancer. Cell. Signal. 2014;26:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli C.A., Perrimon N. Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature. 2006;439:475–479. doi: 10.1038/nature04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Aliaga I., Jasper H., Lemaitre B. Anatomy and physiology of the digestive tract of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2018;210:357–396. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.300224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien L.E., Soliman S.S., Li X., Bilder D. Altered modes of stem cell division drive adaptive intestinal growth. Cell. 2011;147:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein B., Spradling A. The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2006;439:470–474. doi: 10.1038/nature04333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura T., Matsumoto A., Tanimura T., Murakami R. An endoderm-specific GATA factor gene, dGATAe, is required for the terminal differentiation of the Drosophila endoderm. Dev. Biol. 2005;278:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhitko A.A., Binari R., Zhang N., Asara J.M., Demontis F., Perrimon N. Tissue-specific down-regulation of S-adenosyl-homocysteine via suppression of dAhcyL1/dAhcyL2 extends health span and life span in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1409–1422. doi: 10.1101/gad.282277.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasco M.Y., Loudhaief R., Gallet A. The cellular homeostasis of the gut: what the Drosophila model points out. Histol. Histopathol. 2015;30:277–292. doi: 10.14670/HH-30.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan J.C., Khericha M., Dobson A.J., Bolukbasi E., Rattanavirotkul N., Partridge L. Sex difference in pathology of the ageing gut mediates the greater response of female lifespan to dietary restriction. Elife. 2016;5:e10956. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiff T., Jacobson J., Cognigni P., Antonello Z., Ballesta E., Tan K.J., Yew J.Y., Dominguez M., Miguel-Aliaga I. Endocrine remodelling of the adult intestine sustains reproduction in Drosophila. Elife. 2015;4:e06930. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruijtenberg S., van den Heuvel S. Coordinating cell proliferation and differentiation: antagonism between cell cycle regulators and cell type-specific gene expression. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:196–212. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1120925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Marmion R.A., Park J.O., Biswas D., Rabinowitz J.D., Shvartsman S.Y. Dynamic control of dNTP synthesis in early embryos. Dev. Cell. 2017;42:301–308 e303. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vastag L., Jorgensen P., Peshkin L., Wei R., Rabinowitz J.D., Kirschner M.W. Remodeling of the metabolome during early frog development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Guo X., Dou K., Chen H., Xi R. Ttk69 acts as a master repressor of enteroendocrine cell specification in Drosophila intestinal stem cell lineages. Development. 2015;142:3321–3331. doi: 10.1242/dev.123208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Chauhan C., Hou S.X. Characterization of midgut stem cell- and enteroblast-specific Gal4 lines in drosophila. Genesis. 2010;48:607–611. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Hou S.X. Enteroendocrine cells are generated from stem cells through a distinct progenitor in the adult Drosophila posterior midgut. Development. 2015;142:644–653. doi: 10.1242/dev.113357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Z., Kondo S., Ha N., Boquete J.P., Brunner M., Ueda R., Lemaitre B. Accumulation of differentiating intestinal stem cell progenies drives tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:10219. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Z., Boquete J.P., Lemaitre B. A genetic framework controlling the differentiation of intestinal stem cells during regeneration in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DE is provided as fold changes, in log2 scale. Raw counts from the RNA-seq analyses were also provided. Gene IDs and names are based on the FlyBase annotation.

DE is provided as fold changes, in log2 scale. Raw counts from the RNA-seq analyses were also provided.

Data Availability Statement

All the data and methods necessary to reproduce this study are included in the manuscript and Supplemental Information. Reagent request will be readily fulfilled following the materials transfer policies of Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

The GEO accession number for the data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE109862.