Abstract

Background

Amantadine hydrochloride (amantadine) and rimantadine hydrochloride (rimantadine) have antiviral properties, but they are not widely used due to a lack of knowledge of their potential value and concerns about possible adverse effects.

This review was first published in 1999 and updated for the fourth time in April 2008.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the efficacy, effectiveness and safety ('effects') of amantadine and rimantadine in healthy adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2008, issue 1), MEDLINE (1966 to April Week 4, 2008), EMBASE (1990 to April 2008) and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised studies comparing amantadine and/or rimantadine with placebo, control medication or no intervention, or comparing doses or schedules of amantadine and/or rimantadine in healthy adults.

Data collection and analysis

For prophylaxis (prevention) trials we analysed the numbers of participants with clinical influenza (influenza‐like‐illness or ILI) or with confirmed influenza A and adverse effects. Analysis for treatment trials was of the mean duration of fever, length of hospital stay and adverse effects.

Main results

Amantadine prevented 25% of ILI cases (95% confidence interval (CI) 13% to 36%), and 61% of influenza A cases (95% CI 35% to 76%). Amantadine reduced duration of fever by one day (95% CI 0.7 to 1.2). Rimantadine demonstrated comparable effectiveness, but there were fewer trials and the results for prophylaxis were not statistically significant. Both amantadine and rimantadine induced significant gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects. Adverse effects of the central nervous system and study withdrawals were significantly more common with amantadine than rimantadine. Neither drug affected the rate of viral shedding from the nose or the course of asymptomatic influenza.

Authors' conclusions

Amantadine and rimantadine have comparable efficacy and effectiveness in relieving or treating symptoms of influenza A in healthy adults, although rimantadine induces fewer adverse effects than amantadine. The effectiveness of both drugs in interrupting transmission is probably low. Resistance of influenza viruses to amantadine is a serious worldwide problem as shown by recent virological surveillances. Both drugs have adverse gastrointestinal (stomach and gut) effects, but amantadine can also have serious effects on the nervous system. They should only be used in an emergency when all other measures fail.

Keywords: Adult; Aged; Humans; Middle Aged; Influenza A virus; Amantadine; Amantadine/adverse effects; Amantadine/therapeutic use; Antiviral Agents; Antiviral Agents/adverse effects; Antiviral Agents/therapeutic use; Drug Administration Schedule; Emergencies; Influenza, Human; Influenza, Human/drug therapy; Influenza, Human/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Rimantadine; Rimantadine/adverse effects; Rimantadine/therapeutic use; Virus Shedding; Virus Shedding/drug effects

Plain language summary

Antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine for preventing and treating the symptoms of influenza A in adults

The drugs amantadine and rimantadine can both help prevent and relieve the symptoms of influenza A in adults, but amantadine has more adverse effects.

The flu can be caused by many different viruses. One type is influenza A, with headaches, coughs and runny noses that can last for many days and lead to serious illnesses such as pneumonia. Amantadine and rimantadine are antiviral drugs. The review of trials found that both drugs are similarly helpful in relieving the symptoms of influenza A in adults, but only when there is a high probability that the cause of the flu is influenza A (a known epidemic, for example). It is likely that neither drug will interrupt the spread of influenza A and by treating symptoms may encourage viral spread in the community by people who are feeling better but are still infectious. Resistance of influenza viruses to amantadine is a serious worldwide problem as shown by recent surveys. Both drugs have adverse gastrointestinal (stomach and gut) effects, but amantadine can also have serious effects on the nervous system. They should only be used in an emergency when all other measures fail.

Background

Description of the intervention

The M2 ion channel blocking antiviral compounds amantadine hydrochloride (amantadine) and rimantadine hydrochloride (rimantadine) were licensed in 1976 and 1993 respectively as anti‐influenza drugs in the USA. Recently the World Health Organization has encouraged member countries to use antivirals in seasonal influenza "interpandemic periods". The rationale given is as follows: "wide scale use of antivirals and vaccines during a pandemic will depend on familiarity with their effective application during the interpandemic period. The increasing use of these modalities will expand capacity and mitigate the morbidity and mortality of annual influenza epidemics. Studies conducted during the interpandemic period can refine the strategies for use during a pandemic" (WHO 2005). It is also likely that given their low cost amantadine and rimantadine may be used in epidemic or pandemic situations.

This review was first published in 1999 and updated for the fourth time in April 2008.

Objectives

To identify, retrieve and assess all studies evaluating the effects of amantadine and rimantadine on influenza A in healthy adults.

To assess the effectiveness of amantadine and/or rimantadine in preventing cases of influenza A (prophylaxis) in healthy adults, both at an individual level and to interrupt transmission.

To assess the effectiveness of amantadine and/or rimantadine in shortening or reducing the severity of influenza A in healthy adults (treatment).

To estimate the frequency of adverse effects associated with amantadine and/or rimantadine administration in healthy adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any randomised or quasi‐randomised studies comparing amantadine and/or rimantadine in humans with placebo, control medication or no intervention or comparing doses or schedules of amantadine and/or rimantadine. Only studies assessing protection or treatment from exposure to naturally occurring influenza were considered initially.

Types of participants

Apparently healthy individuals (with no known pre‐existing chronic pathology known to aggravate the course of influenza) aged 14 to 60.

Types of interventions

Amantadine and/or rimantadine as prophylaxis and/or treatment for influenza, irrespective of target viral antigenic configuration.

Types of outcome measures

Clinical

Numbers and/or severity (however defined) of influenza cases and/or deaths occurring in amantadine and/or rimantadine and placebo or control groups.

Infectivity of index cases (measured by variables such as length of nasal shedding of influenza viruses or persistence in the upper airways).

Adverse effects

Number and seriousness of adverse effects, including cases of malaise, nausea, fever, arthralgias, rash, headache and more generalised and serious signs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In the original review, published in The Cochrane Library 1999, issue 3, an electronic search of MEDLINE was carried out using the extended search strategy of the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) Group (ARI Group 1998) with the following search terms or combined sets from 1966 to the end of 1997 in any language:

Influenza Route (oral) Route (parenteral) Amantadine Rimantadine

We read the bibliography of retrieved articles and of reviews of the topic in order to identify further trials. We also carried out a search of the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CCTR) and of EMBASE (1985 to 1997). In order to locate unpublished trials we wrote to the following:

manufacturers;

researchers active in the field;

first or corresponding authors of studies evaluated (but not necessarily included) in the review.

In the first updated review published in 2001, the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group's Trials Register was searched in March 2001, and CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2001, issue 2) was also searched for new trials.

In the second updated review in 2003, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2003, issue 4), MEDLINE (January 1966 to November week 2, 2003), EMBASE (1990 to November 2003) and reference lists of articles. We also contacted manufacturers, researchers and authors. There were no language restrictions.

In the third updated review, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2005, issue 3), MEDLINE (2003 to August Week 4, 2005), EMBASE (October 2003 to July 2005) and reference lists of articles. We also contacted manufacturers, researchers and authors. There were no language restrictions.

In the fourth updated review, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2008, issue 1), MEDLINE (2005 to April Week 4, 2008) and EMBASE (July 2005 to April 2008). There were no language or publication restrictions.

We ran the following search strategy on MEDLINE (a similar search strategy was used to search for trials on CENTRAL and EMBASE).

MEDLINE

1 exp INFLUENZA 2 influenza$ 3 or/1‐2 4 exp AMANTADINE 5 amantadine 6 exp RIMANTADINE 7 rimantadine 8 or/4‐7 9 3 and 8 10 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.pt. 11 CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 12 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS.sh. 13 RANDOM ALLOCATION.sh. 14 DOUBLE BLIND METHOD.sh. 15 SINGLE‐BLIND METHOD.sh. 16 or/10‐15 17 (ANIMAL not HUMAN).sh. 18 16 not 17 19 CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 20 exp Clinical Trials 21 (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 22 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 23 PLACEBOS.sh. 24 placebo$.ti,ab. 25 random$.ti,ab. 26 or/19‐25 27 26 not 17 28 18 or 27 29 9 and 28

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (VD, TOJ) independently read all trials retrieved in the search and applied the inclusion criteria. VD and TOJ assessed trials fulfilling the review inclusion criteria for quality, and analysed results.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (TOJ and DR) extracted data from included studies on standard forms. The procedure was supervised and arbitrated by VD. The following data were extracted, checked and recorded:

Characteristics of participants.

Number of participants.

Age, gender, ethnic group and risk category.

Characteristics of interventions

Type of antiviral, type of placebo, dose, treatment or prophylaxis schedule and length of follow up (in days).

Characteristics of outcome measures

Number and severity of influenza and ILI cases and deaths in amantadine/rimantadine and placebo groups.

Length of nasal shedding of influenza viruses or persistence in the upper airways.

Adverse effects

Four categories were used:

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhoea and constipation).

Increased central nervous system (CNS) activity (insomnia, restlessness, light‐headedness, nervousness and concentration problems).

Decreased CNS activity (malaise, depression, fatigue, vertigo and feeling drunk).

Dermatological changes (urticaria and rash).

(Adverse effect data were collected as the number of participants experiencing each (or any) adverse effect).

Number of withdrawals due to adverse effects.

Date of trial.

Location of trial.

Sponsor of trial (specified, known or unknown).

Publication status.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We carried out assessment of methodological quality for RCTs using criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We assessed studies according to randomisation, generation of the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding and follow up. We entered extracted data into Cochrane Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). Aggregation of data was dependent on the sensitivity and consistency of definitions of exposure, populations and outcomes used.

Assessment of trial quality was made according to the following criteria:

Generation of allocation schedule (defined as the methods of generation of the sequence which ensures random allocation).

Measure(s) taken to conceal treatment allocation (defined as methods to prevent selection bias, that is to say, to ensure that all participants have the same chance of being assigned to one of the arms of the trial. It protects the allocation sequence before and during allocation).

Number of drop‐outs of allocated healthcare worker participants from the analysis of the trial (defined as the exclusion of any participants for whatever reason ‐ deviation from protocol, loss to follow up, withdrawal, discovery of ineligibility, while the unbiased approach analyses all randomised participants in the originally assigned groups, regardless of compliance with protocol ‐ known as intention‐to‐treat analysis).

Measures taken to implement double‐blinding (a single blind study is one in which observer(s) or subjects are kept ignorant of the group to which the subjects are assigned). When both the observer and the participants are kept ignorant of assignment the trial is called double‐blind. Unlike allocation concealment, double blinding seeks to prevent ascertainment bias and protects the sequence after allocation).

For criteria 2, 3 and 4 there is empirical evidence that low quality in their implementation is associated with exaggerated trial results (Schulz 1995) and it is reasonable to infer a quality link between all four items.

The four criteria were assessed by answering the following questions:

Generation of allocation schedule

Did the review author(s) use?

Random number tables.

Computer random‐number generator.

Coin tossing.

Shuffling of allocation cards.

Any other method which appeared random.

Concealment of treatment allocation

Which of the following was carried out?

There was some form of centralised randomisation scheme where details of an enrolled participant were passed to a trial office or a pharmacy to receive the treatment group allocation.

Treatment allocation was assigned by means of an on‐site computer using a locked file which could be accessed only after inputting the details of the participant.

There were numbered or coded identical looking compounds which were administered sequentially to enrolled participants.

There were opaque envelopes, which had been sealed and serially numbered, utilised to assign participants to intervention(s).

A mixture of the above approaches including innovative schemes, provided the method appears impervious to allocation bias.

Allocation by alternation or date of birth or case record or day of the week or presenting order or enrolment order.

Concealment methods were described as 'adequate' for (1), (2), (3), (4) or (5). Method (6) was regarded as 'inadequate',as were trials using a system of random numbers or assignments. For some trials allocation was regarded as 'unclear' if only terms such as 'lists' or 'tables' or 'sealed envelopes' or 'randomly assigned' were mentioned in the text.

Exclusion of allocated participants from the analysis of the trial

Did the report mention explicitly the exclusion of allocated participants from the analysis of trial results?

If so did the report mention the reason(s) for exclusion? (if yes, specify).

Measures to implement double blinding

Did the report mention explicitly measures to implement and protect double blinding?

Did the author(s) report on the physical aspect of amantadine/rimantadine administration, that is, appearances, colour, route of administration.

Arbitration procedure

There was no disagreement between TOJ and VD on the quality of trials, but DR was appointed as arbitrator.

Measures of treatment effect

The risk ratios (RR) of events comparing prophylaxis and placebo groups from the individual trials were combined using the DerSimonian and Laird (DerSimonian 1986) random‐effects model to include between‐trial variability. We carried out a sensitivity analysis of methods used, comparing our results obtained using the fixed‐effect and random‐effects models. In the prophylaxis trials efficacy was derived as 1‐RR x 100 or the RR when not significant. Odds ratios (OR) were used to estimate association of adverse effects with exposure to antivirals. In treatment trials the choice of methods for combining the estimates of severity of influenza depended on the format in which the data were presented. We made comparisons between the mean duration of symptoms in the two groups, and methods for combining differences in means were used. Specifically, where the data were presented as the number of subjects with duration of symptoms beyond a cut‐off time period these were presented as 'cases with fever at 48 hours'. The bewildering array of outcomes used in the treatment trials prevented us from using more than the 'cases with fever' outcome.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 198 reports possibly fulfilling our inclusion criteria and retrieved 55 reports. We excluded 22 and classified one as pending translation from Polish. For descriptions see the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Prophylaxis trials

We identified 20 reports of 21 prophylaxis and safety trials fulfilling our inclusion criteria. We were unable to identify any unpublished trials, despite receiving nine letters and three electronic communications from manufacturers, authors and researchers.

The mean amantadine arm size was 327 individuals (median 140.5, 25th percentile 92.5, 75th percentile 348.2), the mean rimantadine arm size was 87 individuals (median 102, 25th percentile 63, 75th percentile 114) and the mean placebo arm size was 265 individuals (median 139, 25th percentile 99, 75th percentile 269). Differences in mean and median size were due to few bigger trials (Peckinpaugh 1970a; Peckinpaugh 1970b; Smorodintsev 1970) and several smaller ones.

The mean sample was 599 individuals (median 297, 25th percentile 202, 75th percentile 536). Mean length of follow up was 30 days (median 30 days, 25th percentile 16.5 days, 75th percentile 42 days). The duration of the epidemic was specified by only one trial (Kantor 1980) and was 49 days.

The identified trials are listed below (using the name of the first author):

Brady 1990 Callmander 1968 Dolin 1982 Hayden 1981 Kantor 1980 Máté 1970 Millet 1982 Monto 1979 Muldoon 1976 Nafta 1970 Oker‐Blom 1970 Payler 1984 Peckinpaugh 1970a Peckinpaugh 1970b Pettersson 1980 Plesnik 1977 Quarles 1981 Reuman 1989 Schapira 1971 Smorodintsev 1970 Wendel 1966

Treatment trials

We identified 13 published treatment trials (one by Máté 1970 contained both treatment and prophylaxis data). We were unable to identify any unpublished trials. The mean amantadine arm size was 80 individuals (median 63, 25th percentile 18.5, 75th percentile 90.2), the mean rimantadine arm size was 47 individuals (median 20, 25th percentile 11.5, 75th percentile 82.5) and the mean control arm size was 66 individuals (median 35.5, 25th percentile 13.5, 75th percentile 87.6). Again, differences in mean and median size were due to one bigger trial (Kitamoto 1968) and the others being smaller ones. The mean sample was 140 individuals (median 90.5, 25th percentile 29.7, 75th percentile 87.6). Mean length of follow up was 23 days (median 21 days, 25th percentile 10 days, 75th percentile 30 days).

Identified trials are listed below using the name of the first author and year of publication in the case of there being more than one trial by the same author. One trial (Hornick 1969) was broken down further into four sub‐trials (see below for explanation).

Galbraith 1971 Hayden 1980 Hayden 1986 Hornick 1969a Hornick 1969b Hornick 1969c Hornick 1969d Ito 2000 Kitamoto 1968 Kitamoto 1971 Knight 1970 Máté 1970 Rabinovich 1969 Younkin 1983 van Voris 1981 Wingfield 1969

We identified 10 reports related to 11 trials which had been carried out during the 1968 to 1969 pandemic (Galbraith 1971; Kitamoto 1968; Knight 1970; Máté 1970; Muldoon 1976; Nafta 1970; Oker‐Blom 1970; Peckinpaugh 1970a; Peckinpaugh 1970b; Schapira 1971; Smorodintsev 1970).

Risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (VD, TOJ) assessed allocation method, allocation concealment, blinding and completeness of follow up. There were 30 trials in all, 28 of which considered either amantadine and/or rimantadine efficacy and two (Hayden 1981; Millet 1982) which considered adverse effects only. Twelve prophylaxis trials and seven treatment trials reported sufficient data on adverse effects. The quality of the prophylaxis trials was relatively good, considering their age. Among the 20 prophylaxis trials, 17 stated that the allocation method was randomised, although only four mentioned a particular method (Brady 1990; Monto 1979; Pettersson 1980; Reuman 1989) and two did not mention random allocation at all (Plesnik 1977; Schapira 1971). These two trials have therefore been classified as controlled clinical trials (CCTs) rather than RCTs. All prophylaxis trials were stated to be double‐blind, with the exception of Payler 1984 which was open and had no placebo group (the comparison group was no intervention other than influenza vaccine at the beginning of the season). Among the 13 treatment trials, 11 stated that the allocation method was randomised and no trials mentioned a particular method. For Hornick's trials (Hornick 1969a; Hornick 1969b; Hornick 1969c; Hornick 1969d) there was no mention of random allocation at all. Very limited information was available for one trial (Ito 2000).

Major flaws in the reporting of trials were:

Lack of information on the completeness of follow up. In many trials there was a large difference between the number randomised and the number who actually participated.

Lack of detailed description of methods to conceal allocation with many trials just describing a "double‐blind" procedure.

Frequent inconsistencies in the reporting of numerators and denominators in various arms of trials.

In the treatment trials, the use of a bewildering variety of outcomes, such as severity scores, of which none were alike.

A full description of all trials is available in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Effects of interventions

We carried out nine comparisons:

Comparison A ‐ oral amantadine compared to placebo in the prophylaxis of influenza or ILI. Comparison B ‐ oral rimantadine compared to placebo in the prophylaxis of influenza or ILI. Comparison C ‐ oral amantadine compared to oral rimantadine in the prophylaxis of influenza or ILI. Comparison D ‐ oral amantadine compared to placebo in the treatment of influenza. Comparison E ‐ oral rimantadine compared to placebo in the treatment of influenza. Comparison F ‐ oral amantadine compared to oral rimantadine in the treatment of influenza. Comparison G ‐ oral or inhaled amantadine versus placebo or aspirin in the nasal viral shedding or persistence in upper airways at two to five days. Comparison H ‐ oral amantadine compared to control medication in the treatment of influenza. Comparison I ‐ inhaled amantadine compared to placebo in the treatment of influenza.

For comparisons A, B and C we analysed the effects on 'cases', stratified either as influenza (a defined set of signs and symptoms backed up by serological confirmation and/or isolation of influenza virus from nasal fluids) or clinical criteria alone (ILI) or asymptomatic cases (serological confirmation and/or isolation of influenza virus from nasal fluids without symptoms). The effects on nasal viral shedding were assessed by single studies: Reuman 1989(amantadine) and Dolin 1982 (rimantadine). We stratified comparisons on the basis of whether participants had received vaccination or not.

Additionally we assessed adverse effects in both comparisons.

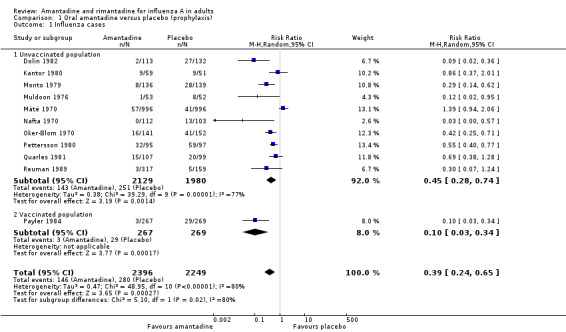

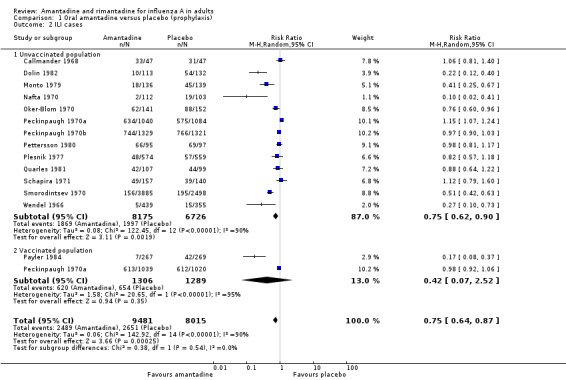

In Comparisons A and B significant heterogeneity between the trial results was evident for both types of influenza analyses, so all results quoted are average treatment effects based on random‐effects models. In Comparison A, amantadine prevented 61% (95% CI 35% to 76%) of influenza cases and 25% (95% CI 13% to 36%) of ILI cases. Both of these results are highly statistically significant (P < 0.001). There was no effect on asymptomatic cases (risk ratio (RR) 0.85; 95% CI 0.40 to 1.80), nor any difference in efficacy between unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals (RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.28 to 0.74 and RR 0.10; 95% CI 0.03 to 0.34). The effectiveness in unvaccinated subjects is significantly higher than that of placebo in unvaccinated subjects (RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.07 to 2.52), but not in vaccinated individuals 0.75 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.90).

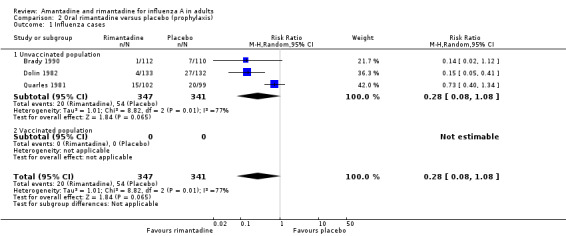

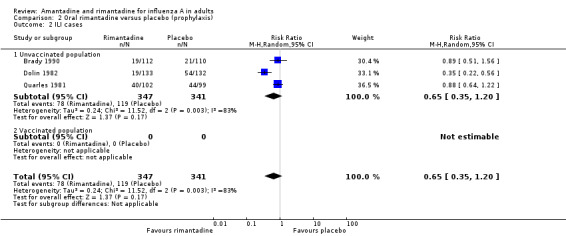

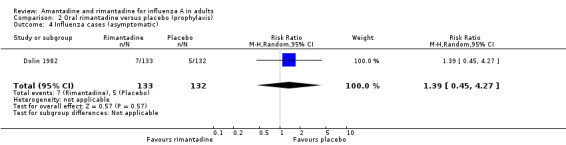

In Comparison B rimantadine was not effective against either influenza (RR 0.28; 95% CI 0.08 to 1.08) or ILI (RR 0.65; 95% CI 0.35 to 1.20), however, analysis using a fixed‐effect model shows significant protection against influenza and ILI in unvaccinated participants. Whilst these results are conventionally not statistically significant (P = 0.07 and P = 0.17, respectively), the estimates are based on only 688 individuals, and are of a very similar magnitude to those for amantadine. There was no effect on asymptomatic cases (RR 1.39; 95% CI 0.45 to 4.27), although this observation is based on one study only (Dolin 1982).

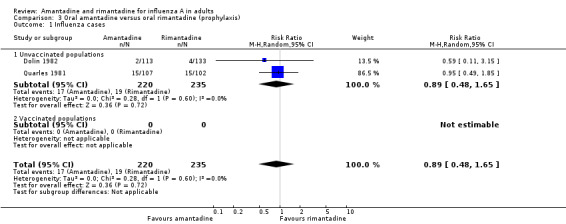

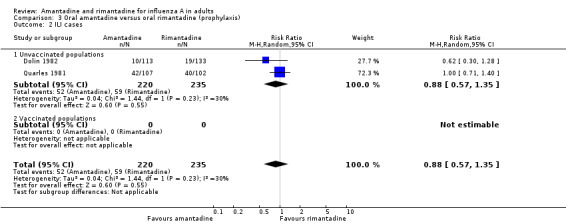

In Comparison C there is no evidence of a difference in efficacy between amantadine and rimantadine, although the confidence interval is quite wide (RR amantadine versus rimantadine 0.88. 95% CI 0.57 to 1.35). In comparisons B and C there were insufficient data to stratify by vaccine status of participants.

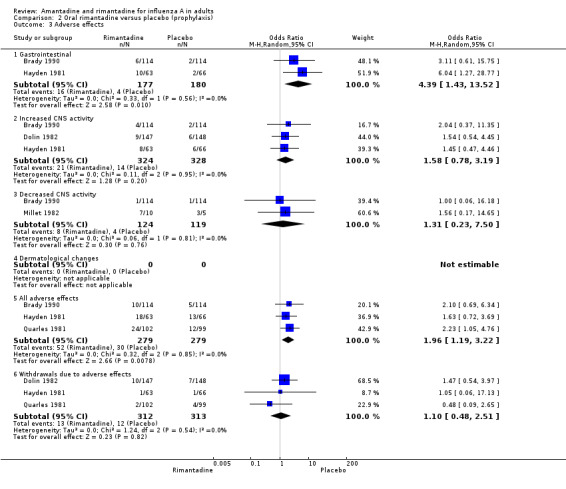

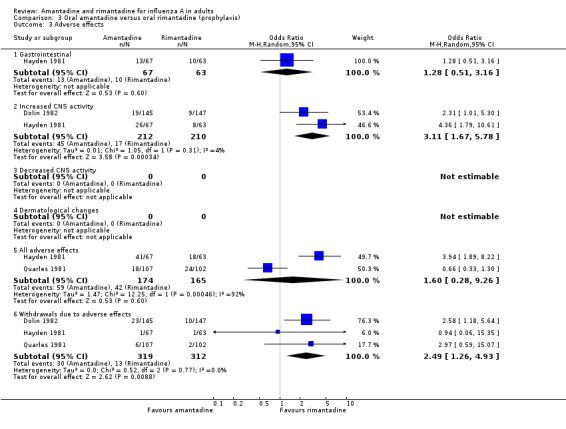

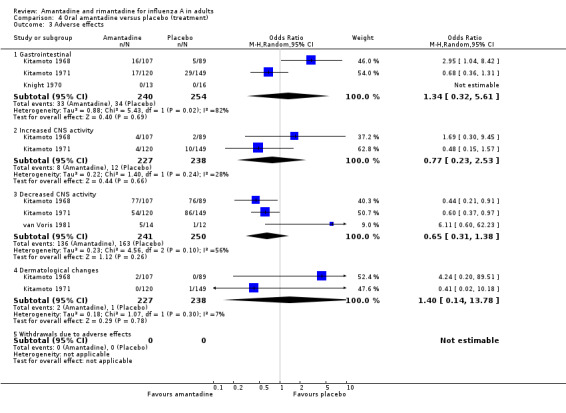

The 'all adverse effects' category includes all types and was derived from those trials which either did not report sufficient information to allow a more detailed classification or which presented aggregate data. Adverse effects incidence is reported in our meta‐analysis as the number of participants with at least one event, thus the incidence of individual adverse effects cannot be summed to give the total with any adverse effect as more than one adverse event is likely to have taken place in the same individual during the trial.

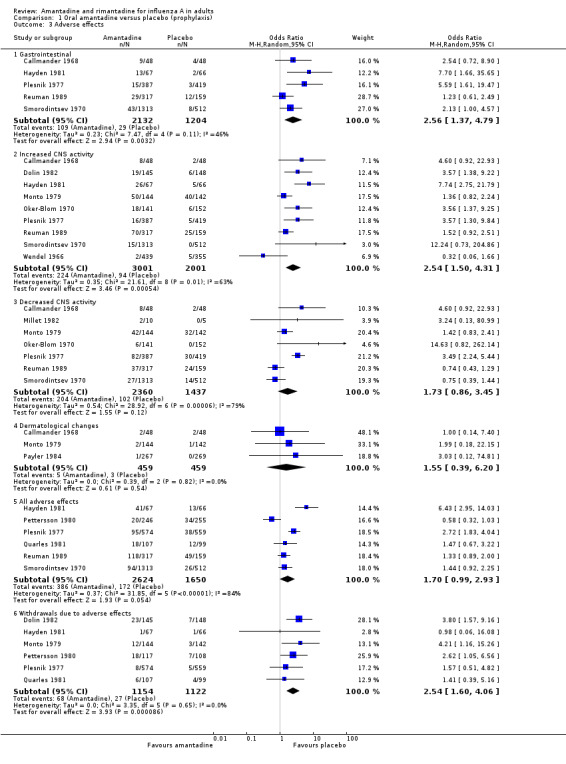

In Comparison A gastrointestinal symptoms (mainly nausea, odds ratio (OR) 2.56; 95% CI 1.37 to 4.79), insomnia and hallucinations (OR 2.54; 95% CI 1.50 to 4.31) and withdrawals from the trials because of adverse events (2.54; 95% CI 1.60 to 4.06) were significantly more common in participants who received amantadine than placebo. Analysis using a fixed‐effect model shows a significant association with depression, insomnia and the 'all adverse events' category.

In Comparison B, rimantadine recipients were also more likely to experience 'all adverse effects' than placebo recipients (OR 1.96; 95% CI 1.19 to 3.22). However, there was no evidence of an increase in CNS‐related effects with rimantadine, and withdrawal rates were similar in both groups.

The direct comparison of amantadine with rimantadine (Comparison C) confirmed that CNS adverse effects and withdrawal from trials were significantly more frequent among amantadine recipients than rimantadine recipients (CNS effects, OR 3.11; 95% CI 1.67 to 5.78; withdrawals OR 2.49; 95% CI 1.26 to 4.93).

Thus rimantadine may be no less efficacious but safer than amantadine in preventing cases of influenza in healthy adults. Readers should bear in mind that the study sizes of the safety trials of rimantadine are considerably smaller than those of amantadine, so that the conclusions that can be drawn for rimantadine are somewhat less certain than those for amantadine.

We considered meta‐analysing symptoms outcome data to further inform the assessment of the effects of amantadine and rimantadine in the treatment role. When we tabulated the outcome typology we discovered that such a meta‐analysis would be impossible as can be seen from Table 1.

1. Trial symptom outcomes used.

| Galbraith 1971 | Average time to clearance of symptoms |

| Hayden 1980 | Aggregate scores of systemic and respiratory symptoms |

| Hayden 1986 | Aggregate scores of systemic and respiratory symptoms |

| Hornick 1969a | Percentage of patients in three symptoms clearance time periods |

| Kitamoto 1968 | No symptoms |

| Kitamoto 1971 | No symptoms |

| Knight 1970 | Between arms symptoms concordance. Aggregate data only |

| Máté 1970 | Duration of fever (aggregate) and length of stay in infirmary |

| Togo 1970* | Percentage of patients in three symptoms clearance time periods |

| Younkin 1983* | Significance of the difference of symptoms scores |

| van Voris 1981 | Percentage of improvement of symptom scores at different time periods |

| Wingfield 1969 | Significance of difference of proportions of patients in three symptoms clearance time periods |

We resorted to using duration of fever (defined as a temperature greater than 37 °C) as the only common outcome. One obvious cost of this approach is the possible confounding effect of the presence of fever for a variable length of time prior to and after entry to the study (and hence at the moment of commencement of treatment). However, if random allocation had been properly carried out, this effect should disappear.

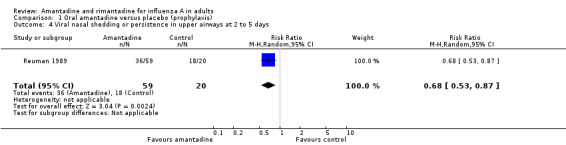

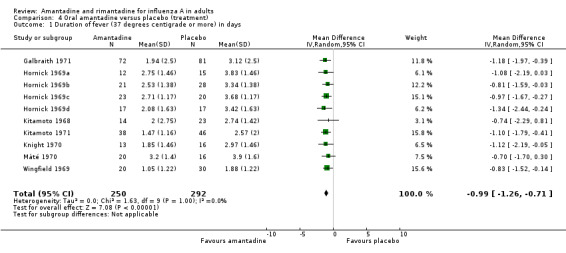

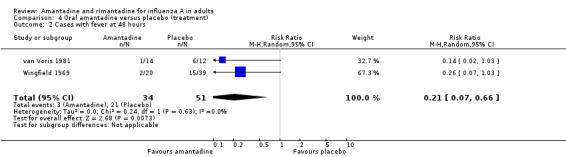

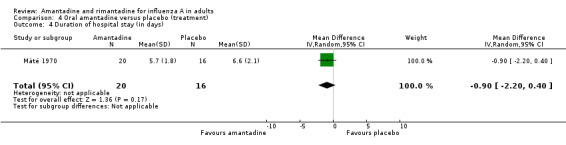

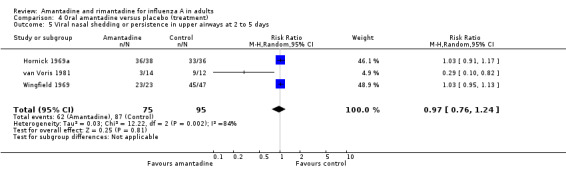

In Comparison D amantadine significantly shortened duration of fever compared to placebo (by 0.99 days; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.26). The meta‐analysis is based on 542 subjects (250 in the amantadine and 292 in the placebo arm). Where time to fever clearance data were not available (as in van Voris 1981 and Wingfield 1969), a dichotomous outcome was used (cases with fever at 48 hours). This comparison showed that amantadine was significantly better than placebo (RR 0.21; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.66). However, there was no effect on nasal shedding or persistence of influenza A viruses in the upper airways after up to five days of treatment (RR 0.97; 95% CI: 0.76 to 1.24).

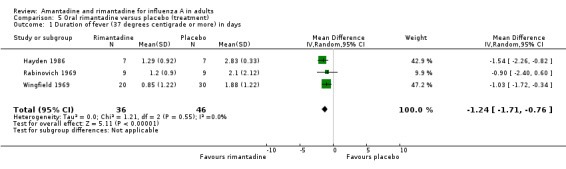

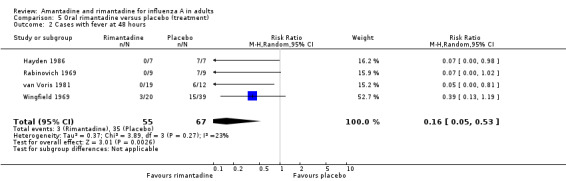

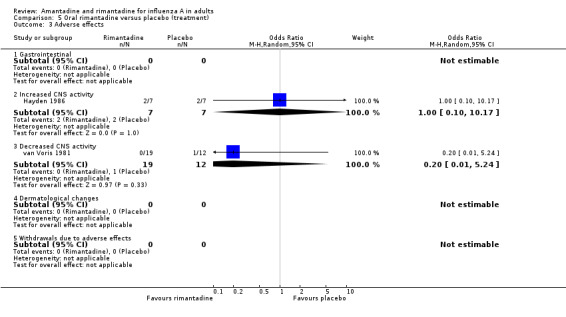

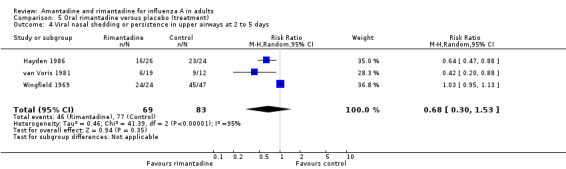

In Comparison E rimantadine shortened duration of fever compared to placebo (by 1.24 days; 95% CI ‐0.76 to ‐1.71). There were a significantly higher number of afebrile cases 48 hours after commencing rimantadine treatment (RR 0.16; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.53). However, there was no effect on nasal shedding or persistence of influenza A viruses in the upper airways after up to five days of treatment (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.53), although this finding may be due to the small number of observations in this comparison (152) and is sensitive to analysis using a fixed‐effect model.

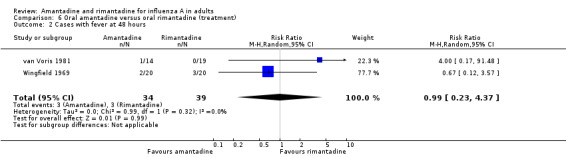

The few data available directly comparing amantadine and rimantadine for treatment (Comparison F) showed that the efficacy of the two drugs was comparable, although the confidence intervals are very wide (for example, cases with fever at 48 hours RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.23 to 4.37).

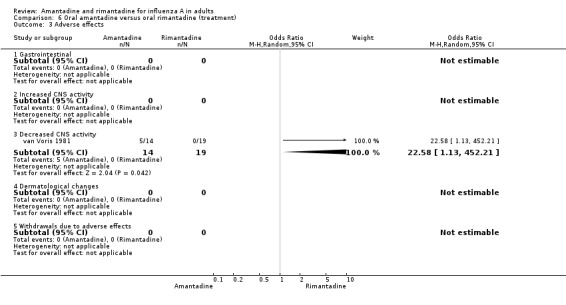

In contrast to the increased adverse effect rates for prophylaxis, there was no evidence that amantadine recipients had higher adverse effect rates than placebo recipients (Comparison D), but data were only available from three trials (Kitamoto 1968; Kitamoto 1971; van Voris 1981 with combined denominator of 491) and the association with decreased CNS activity is sensitive to the application of a fixed‐effect model. There were very few data available for the assessment of adverse effects of rimantadine for treatment (45 participants in Hayden 1986 and van Voris 1981) or the direct comparison between amantadine and rimantadine (33 participants in van Voris 1981).

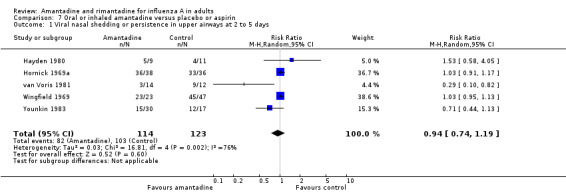

In comparison G the effects of oral or inhaled amantadine on shedding of influenza A viruses are still not significant (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.74 to 1.19), despite meta‐analysis of five studies with a combined denominator of 237 observations.

Readers of this review should bear in mind that the difference in incidence of adverse effects is of importance, rather than the estimated incidence itself, as the adverse effects reported with these drugs are very similar to the clinical manifestations of influenza infection.

Overall both drugs appear to be effective and well‐tolerated, but the evaluation of the effects of rimantadine was carried out on a very small population.

Insufficient data were available to analyse the relationships of dose (or duration) of treatment and clinical or virological effects. However, other data suggest that equivalent doses of amantadine and rimantadine at steady‐state are associated with similar plasma concentrations and similar total clearance values (Aoki 1998).

We carried out further comparisons (H and I).

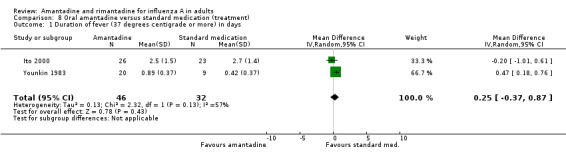

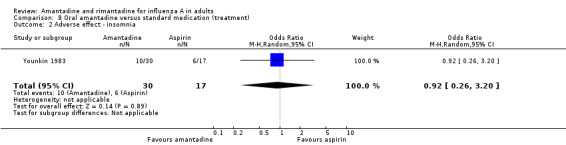

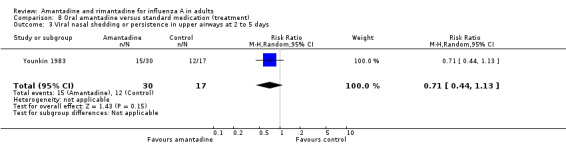

In Comparison H, based on Younkin 1983 and Ito 2000, standard medications (aspirin and other antipyretic or anti‐inflammatory drugs or antibiotics were equally effective compared with amantadine in reducing the length of fever (mean difference (MD) random‐effects model 0.25; 95% CI ‐ 0.37 to 0.87). This observation is based on 78 individuals and in the trial by Ito 2000 amantadine was given at the lower dose of 100 mg. Aspirin and the other antipyretic drugs appear to be as potent as amantadine in treating symptoms, however they do not inhibit viral replication and as such remain a symptomatic remedy.

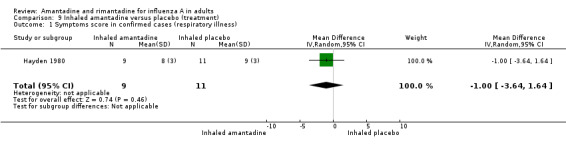

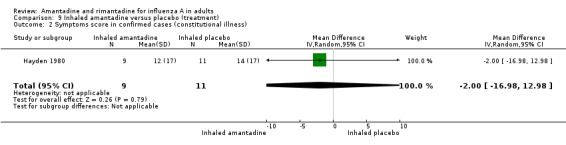

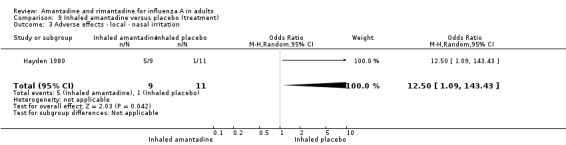

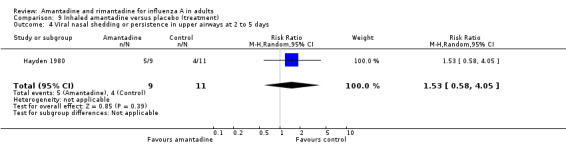

In comparison I (based on the Hayden 1980 trial) inhaled amantadine was no more efficacious than placebo in bringing down the respiratory or constitutional symptom score (MD ‐1.00; 95% CI ‐3.64 to 1.64 and ‐2.00; 95% CI ‐16.98 to 12.98, respectively). This comparison is based on small numbers of participants (20). Not surprisingly, amantadine caused significantly more nasal irritation (RR 12.50; 95% CI 1.09 to 143.43). Inhaled amantadine does not appear to be particularly effective but has a high incidence of local adverse effects, which would make compliance difficult.

Neither comparison showed an effect on nasal shedding or persistence of influenza A viruses in the upper airways after up to five days of treatment, although the interpretation of Comparisons H and I is made difficult by the small numbers involved and the absence of multiple trials.

All trials tested the effects of amantadine and rimantadine on a wide variety of influenza A viruses. None tested the effects on influenza B, on which the molecules are known to be ineffective. No trial tested the role of the compounds on workplace outbreak control, which is a pity considering the trial settings (prisons, factories, schools, barracks).

Some trials are likely to have included individuals who took aspirin to relieve symptoms (especially in the treatment trials). However the effects of this potential confounder should have been eliminated by the process of randomisation.

All trials commenced administration of the compounds within a reasonable time frame. Treatment started at the latest 48 hours after positive identification of the first case in the population and prophylaxis when the results of surveillance made it reasonable to do so.

No trials assessed onset of resistance, but data in one study demonstrated that 10% to 27% of patients treated with amantadine secreted drug‐resistant virus within four to five days of commencing treatment (Aoki 1998).

Separate analysis of the 11 pandemic trials did not affect our findings. Finally, we considered carrying out sub‐analysis by dose (100, 200, 300 mg daily), but decided against this given the small size of the resulting meta‐analysis. We will re‐consider this policy if any further data become available.

Discussion

The results of our review show that both amantadine and rimantadine are efficacious and relatively safe in the prophylaxis and treatment of influenza A symptoms. The role of amantadine in prophylaxis of symptoms (61% effective) and treatment (shortens duration of illness by one day) is beyond question and does not need to be investigated further compared to placebo. Rimantadine appears equally efficacious in prophylaxis (72%), but in direct comparison with placebo, when a random‐effects model is applied, the lower bound of the 95% CI does not achieve statistical significance.

There are two explanations for this difference in the significance of the findings. The first is that the rimantadine result is a 'false negative'. This idea is supported by noting that its average efficacy is both large and similar to amantadine, and that there have been many fewer participants in rimantadine trials than amantadine trials (there are clinical data for approximately only 700 rimantadine compared to 2500 amantadine recipients in the review).

The second explanation is centred on trial heterogeneity. If a fixed‐effect analysis is used (effectively ignoring the heterogeneity) then the difference between rimantadine and placebo for the prophylaxis of influenza cases is highly significant (P value less than 0.001 for both outcomes). All of the analyses of influenza outcomes demonstrated excessive variation in the results of the trials. Such a pattern has been noted in other reviews of preventive procedures, such as influenza and cholera vaccination, and may reflect differences between the trial populations to natural exposure and immunity to influenza A and other similar viruses. We have not been able to explain this heterogeneity in this systematic review.

Rimantadine was also seen to be equally therapeutically efficacious, shortening duration of fever by just over one day. However, again, this observation is based on 82 subjects only.

There is a marked difference between the two drugs in the capacity to prevent influenza and the capacity to prevent influenza‐like‐illness (ILI). The practical importance of this difference, which is rarely explained to the public, is that neither can be used to good effect against ILI, which is the clinical picture presenting to both the patient and the doctor. In the absence of a likely influenza diagnosis their routine use is not to be recommended. This conclusion is also supported by widespread evidence of resistance to both amantadine and rimantadine (Bright 2005).

There do not appear to be significant differences in effectiveness in either role between the two compounds, although again our comparisons are based on small numbers with large confidence intervals.

Our conclusions must be tempered by our finding of a lack of effect of both compounds both on influenza A cases with no clinical symptoms (asymptomatic) and on viral excretion (clearance) from the upper airways (although viral concentration in nasal mucus may be reduced). Both compounds are effective in preventing or treating symptoms, but have lower effectiveness in preventing infection and probably transmission, an observation made in one of the trials included in the review (Monto 1979). As a consequence, it is likely that the estimates of clinical efficacy and effectiveness presented in this review are optimistic. This finding is of crucial importance in planning the use of both compounds in a situation of very high viral circulation and infectivity (such as a serious epidemic or pandemic). In addition, symptom relief may lead to convalescing subjects who are still infected and infectious increasing viral transmission in the community. On the basis of this evidence the WHO recommendations should be redrafted to include the use of amantadine and rimantadine only in emergency situations when all other measures fail.

The safety profile of the two drugs appears significantly different in prophylaxis, with rimantadine causing significantly fewer central nervous system (CNS) adverse effects than amantadine and fewer withdrawals from the trials. Although these observations are based on smaller numbers of rimantadine recipients, amantadine definitely causes signs of significantly increased CNS activity, an effect which is not easily acceptable by healthy adults, especially in employment which requires concentration and mental fitness. Rimantadine has a different pharmacokinetic profile from amantadine, reaching prophylactic concentration in the nasal mucus at much lower plasma concentrations than amantadine. There was a tendency for lower doses of amantadine (100 mg daily) to cause fewer adverse effects than higher doses at the cost of lower effectiveness (data not shown).

We conclude that from the available evidence, rimantadine appears the better choice for individual protection in emergencies.

In future, more attention should be paid to the assessment of adverse events of the two compounds, particularly those of rimantadine which at present are based on relatively small numbers.

The quality of the trials was not good with significant numbers of studies failing to give adequate descriptions of methods and of results. This may be in part due to the number of older trials in the review. Both quality of trial conducting and reporting should be improved and adverse effects and case outcome definitions should be standardised. Finally, the bewildering array of outcome definitions used in treatment studies made the task of meta‐analysis difficult and led to a great loss of information.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Both drugs should be used only in emergency situations when all other measures fail.

Implications for research.

Given our findings we do not believe any further research should be carried out on these compounds.

Feedback

Missing study?

Summary

I recently stuck upon a paper that may be relevant for this review, either to include (am not sure whether the trial was randomized, but it was placebo‐controlled) or as 'excluded study'. Here are the details: Máté J, Simon M, Juvancz I, et al. Prophylactic use of amantadine during Hong Kong influenza epidemic. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung 1970;17: 285‐296. Can send a copy if necessary.

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter of my criticisms

Reply

The study identified by Van Wouden has been included in the review.

Tom Jefferson

Contributors

Johannes C van der Wouden Feedback comment added 27/05/04

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 June 2012 | Review declared as stable | Intervention superseded ‐ as of 07 June 2012, this Cochrane Review is no longer being updated. The editorial team believes that the question addressed by this Cochrane Review no longer relevant to decision making, as amantadine and rimantadine for influenza A in adults has been replaced by neuraminidase inhibitors and are no longer used. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 26 April 2008 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. |

| 14 February 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. |

| 15 September 2005 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. |

| 26 April 2004 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback and reply added. |

| 9 November 2003 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. |

| 29 March 2001 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. |

| 29 April 1998 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. |

Notes

In the 2004 update we included two more studies which had not been identified during the original searches (Máté 1970 and Nafta 1970) and updated text and references. We also assessed and excluded five more trials (Clover 1986; Dawkins 1968; Finklea 1967; Knight 1969; Togo 1968) and are awaiting translation of a further study from Polish (Tkaczewski 1972). The results and conclusions of the review do not change much. The confidence intervals around the effects of amantadine are narrower, but the findings on rimantadine are identical as both Máté and Nafta assessed the effects of amantadine.

The terms 'laboratory‐confirmed influenza' and 'clinically confirmed influenza' have been changed for the more correct terms 'influenza' and 'influenza‐like‐illness' (ILI). We believe these words to reflect the difference between real influenza, caused by A and B viruses and what is colloquially known as 'the flu'. The two are rarely clinically distinguishable in real‐time unless a very good surveillance apparatus is in place, as in most of the trials in our review.

The practical importance of this difference, which is rarely explained to the public, can be seen in the markedly different effectiveness profiles of the two drugs. Rarely can amantadine or rimantadine be used to good effect against ILI, which is what presents to both patient and doctor.

In the 2006 update we included one more treatment trial comparing rimantadine with placebo (Rabinovich 1969) and one comparing amantadine with standard treatment (Ito 2000) and excluded one more study, by Bricaire and colleagues. We also updated and shortened the text.

Because of the threat of a pandemic and on the basis of a comment made by Professor Robert B Couch we assessed the effectiveness of both compounds in preventing infection (as opposite to preventing or treating its symptoms) and in interrupting the chain of transmission (measured by the quantity and duration of viruses voided from the upper airways of infected people). We found no evidence of effectiveness of either compound. This led us to revise 'downwards' our estimates of effectiveness and warn readers that amantadine and rimantadine should be used only in emergencies. This conclusion was also based on the mounting evidence of resistance of influenza A viruses to both compounds.

In this April 2008 update we re‐ran the searches but found no items relevant to the review. The conclusions and the text stand unaltered.

Acknowledgements

The review authors would like to thank Drs Aoki, Couch, Hayden and Monto for helpful comments; Dr van der Wouden for providing the Máté 1970 trial report; and Mrs Carol Hobbs, Ms Ruth Foxlee, Ann‐Charlott Johansson and Jessika Wejfalk for assistance with trial identification and retrieval. The review authors wish to acknowledge Jon Deeks for his contribution as a co‐author on the original and subsequent updates until 2004. The review authors also wish to thank Melanie Rudin for her assistance with the administrative organising of the 2005 update and for keeping track of the information, and to thank the following people for commenting on earler versions of the review: Amy Zelmer, Douglas Fleming, Kuldeep Kumar and Allen Cheng. Finally, the review authors wish to thank the following people for commenting on the 2008 updated draft: Mina Mahdian, Fred Aoki, Mark Jones, and Allen Cheng.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oral amantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Influenza cases | 11 | 4645 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.24, 0.65] |

| 1.1 Unvaccinated population | 10 | 4109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.28, 0.74] |

| 1.2 Vaccinated population | 1 | 536 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.03, 0.34] |

| 2 ILI cases | 14 | 17496 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.64, 0.87] |

| 2.1 Unvaccinated population | 13 | 14901 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.62, 0.90] |

| 2.2 Vaccinated population | 2 | 2595 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.07, 2.52] |

| 3 Adverse effects | 13 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Gastrointestinal | 5 | 3336 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.37, 4.79] |

| 3.2 Increased CNS activity | 9 | 5002 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.54 [1.50, 4.31] |

| 3.3 Decreased CNS activity | 7 | 3797 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.86, 3.45] |

| 3.4 Dermatological changes | 3 | 918 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.55 [0.39, 6.20] |

| 3.5 All adverse effects | 6 | 4274 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.70 [0.99, 2.93] |

| 3.6 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 6 | 2276 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.54 [1.60, 4.06] |

| 4 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days | 1 | 79 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.53, 0.87] |

| 5 Influenza cases (asymptomatic) | 4 | 963 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.40, 1.80] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral amantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 1 Influenza cases.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral amantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 2 ILI cases.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral amantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 3 Adverse effects.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral amantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 4 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral amantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 5 Influenza cases (asymptomatic).

Comparison 2. Oral rimantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Influenza cases | 3 | 688 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.08, 1.08] |

| 1.1 Unvaccinated population | 3 | 688 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.08, 1.08] |

| 1.2 Vaccinated population | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 ILI cases | 3 | 688 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.35, 1.20] |

| 2.1 Unvaccinated population | 3 | 688 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.35, 1.20] |

| 2.2 Vaccinated population | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Adverse effects | 5 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Gastrointestinal | 2 | 357 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.39 [1.43, 13.52] |

| 3.2 Increased CNS activity | 3 | 652 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.78, 3.19] |

| 3.3 Decreased CNS activity | 2 | 243 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.23, 7.50] |

| 3.4 Dermatological changes | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.5 All adverse effects | 3 | 558 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.96 [1.19, 3.22] |

| 3.6 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 3 | 625 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.48, 2.51] |

| 4 Influenza cases (asymptomatic) | 1 | 265 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.45, 4.27] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 1 Influenza cases.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 2 ILI cases.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 3 Adverse effects.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (prophylaxis), Outcome 4 Influenza cases (asymptomatic).

Comparison 3. Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (prophylaxis).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Influenza cases | 2 | 455 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.48, 1.65] |

| 1.1 Unvaccinated populations | 2 | 455 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.48, 1.65] |

| 1.2 Vaccinated populations | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 ILI cases | 2 | 455 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.57, 1.35] |

| 2.1 Unvaccinated populations | 2 | 455 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.57, 1.35] |

| 2.2 Vaccinated populations | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Adverse effects | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Gastrointestinal | 1 | 130 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.51, 3.16] |

| 3.2 Increased CNS activity | 2 | 422 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.11 [1.67, 5.78] |

| 3.3 Decreased CNS activity | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.4 Dermatological changes | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.5 All adverse effects | 2 | 339 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.60 [0.28, 9.26] |

| 3.6 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 3 | 631 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.49 [1.26, 4.93] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (prophylaxis), Outcome 1 Influenza cases.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (prophylaxis), Outcome 2 ILI cases.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (prophylaxis), Outcome 3 Adverse effects.

Comparison 4. Oral amantadine versus placebo (treatment).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days | 10 | 542 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.99 [‐1.26, ‐0.71] |

| 2 Cases with fever at 48 hours | 2 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.07, 0.66] |

| 3 Adverse effects | 4 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Gastrointestinal | 3 | 494 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.32, 5.61] |

| 3.2 Increased CNS activity | 2 | 465 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.23, 2.53] |

| 3.3 Decreased CNS activity | 3 | 491 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.31, 1.38] |

| 3.4 Dermatological changes | 2 | 465 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.14, 13.78] |

| 3.5 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Duration of hospital stay (in days) | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.90 [‐2.20, 0.40] |

| 5 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days | 3 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.24] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oral amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oral amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 2 Cases with fever at 48 hours.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oral amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 3 Adverse effects.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oral amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 4 Duration of hospital stay (in days).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oral amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 5 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days.

Comparison 5. Oral rimantadine versus placebo (treatment).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days | 3 | 82 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.24 [‐1.71, ‐0.76] |

| 2 Cases with fever at 48 hours | 4 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.05, 0.53] |

| 3 Adverse effects | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Gastrointestinal | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.2 Increased CNS activity | 1 | 14 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.10, 10.17] |

| 3.3 Decreased CNS activity | 1 | 31 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.01, 5.24] |

| 3.4 Dermatological changes | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.5 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days | 3 | 152 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.30, 1.53] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 2 Cases with fever at 48 hours.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 3 Adverse effects.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oral rimantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 4 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days.

Comparison 6. Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (treatment).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

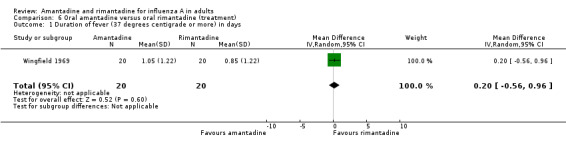

| 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [‐0.56, 0.96] |

| 2 Cases with fever at 48 hours | 2 | 73 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.23, 4.37] |

| 3 Adverse effects | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Gastrointestinal | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.2 Increased CNS activity | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.3 Decreased CNS activity | 1 | 33 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 22.58 [1.13, 452.21] |

| 3.4 Dermatological changes | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.5 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (treatment), Outcome 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (treatment), Outcome 2 Cases with fever at 48 hours.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oral amantadine versus oral rimantadine (treatment), Outcome 3 Adverse effects.

Comparison 7. Oral or inhaled amantadine versus placebo or aspirin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days | 5 | 237 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.74, 1.19] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oral or inhaled amantadine versus placebo or aspirin, Outcome 1 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days.

Comparison 8. Oral amantadine versus standard medication (treatment).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days | 2 | 78 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐0.37, 0.87] |

| 2 Adverse effect ‐ insomnia | 1 | 47 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.26, 3.20] |

| 3 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days | 1 | 47 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.44, 1.13] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oral amantadine versus standard medication (treatment), Outcome 1 Duration of fever (37 degrees centigrade or more) in days.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oral amantadine versus standard medication (treatment), Outcome 2 Adverse effect ‐ insomnia.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oral amantadine versus standard medication (treatment), Outcome 3 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days.

Comparison 9. Inhaled amantadine versus placebo (treatment).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Symptoms score in confirmed cases (respiratory illness) | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐3.64, 1.64] |

| 2 Symptoms score in confirmed cases (constitutional illness) | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.0 [‐16.98, 12.98] |

| 3 Adverse effects ‐ local ‐ nasal irritation | 1 | 20 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 12.50 [1.09, 143.43] |

| 4 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.53 [0.58, 4.05] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Inhaled amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 1 Symptoms score in confirmed cases (respiratory illness).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Inhaled amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 2 Symptoms score in confirmed cases (constitutional illness).

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Inhaled amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 3 Adverse effects ‐ local ‐ nasal irritation.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Inhaled amantadine versus placebo (treatment), Outcome 4 Viral nasal shedding or persistence in upper airways at 2 to 5 days.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Brady 1990.

| Methods | Prophylaxis, randomised, double‐blind, controlled trial of rimantadine during an epidemic of influenza A/Leningrad/87 [H3N2] virus | |

| Participants | 228 healthy, not previously vaccinated, adult volunteers aged 18 to 55 | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomised to receive either rimantadine 100 mg daily or placebo for 6 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Laboratory: paired sera were taken from all participants at the beginning and the end of the study. Within‐trial surveillance was carried out on a weekly basis and cases were defined on the basis of seroconversion and a pre‐defined list of symptoms and signs. The study reports separately on the efficacy of asymptomatic cases of influenza (diagnosed from a rise in antibody titres). Viral isolation took place by nasal washout |

|

| Notes | Brady is a clearly written and well‐reported trial (with the exception of the minor discrepancy between text and tables on the affiliation of drop‐outs). Randomisation was computer‐generated and allocation was concealed with a centralised scheme. Additionally, intention‐to‐treat analysis is clearly stated in the text |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Callmander 1968.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial conducted in a community, including some military personnel. During the period of the trial there was considerable influenza A2 (Leningrad) activity | |

| Participants | The age range of the 94 volunteer participants is 20 to 60 years (44 male and 50 female) | |

| Interventions | The intervention arm received 100 mg of amantadine hydrochloride twice daily and the control arm (a not further described placebo) | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: ILI cases (from a symptoms list) in each arm and a symptom score (reported in Table 1 without an indication of time of intensity). Surveillance for adverse effects (systemic) was carried out. A list of symptoms (without a denominator) is reported in Table 2 | |

| Notes | The practices of randomisation, allocation and concealment are not further defined, making it impossible to assess methodological rigour although as the distribution of sex and age was checked and found to be similar, randomisation is likely to have been satisfactory | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dolin 1982.

| Methods | Prophylaxis, randomised, double‐blind, placebo controlled trial carried out in Burlington Vermont, USA. The trial was commenced on 10 January 1981 during an outbreak of influenza A/Bangkok/1/79H3N2 and A/Brazil/11/78H1N1 detected by surveillance (see Figure 1 in the text of the trial report) | |

| Participants | Participants initially were 450 healthy non‐vaccinated volunteers aged 18 to 45 (mean age 25.6 + 0.45 years). The final total of participants was 378 (132 in the placebo arm, 133 in the rimantadine arm and 113 in the amantadine arm) | |

| Interventions | Amantadine 200 mg daily or rimantadine 200 mg or placebo | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: case definition was based on a list of symptoms plus virus isolation or a rise in serum antibody titres to influenza A. Table 1 presents both ILI cases and cases defined on the basis of laboratory confirmation. The study reports separately the efficacy on asymptomatic cases of influenza (diagnosed from a rise in antibody titres) |

|

| Notes | Although a well‐written report, no real information is given on random allocation, blinding and concealment. Intention‐to‐treat analysis was not carried out | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Galbraith 1971.

| Methods | Treatment trial carried out in December 1969 to January 1970, at the time of an epidemic (possible pandemic) caused by a variant of A2/Hong Kong/68 | |

| Participants | Participants were unvaccinated family members aged more than 2 years recruited by 57 family doctors in the United Kingdom | |

| Interventions | 153 participants with laboratory‐confirmed diagnosis of influenza A2 were randomised to receive either doses appropriate to their ages: for adults amantadine 200 mg a day (n = 72, mean age 37.4 years), or placebo (n = 81, mean age 39.1). Treatment was commenced within 48 hours of symptoms and continued for 7 days | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: outcomes are clinical (Tables 2 and 3) and serological (Table 4 and 5). In our meta‐analysis, we have included the time of duration of fever (in days after commencement of treatment (Table 2) approximating the standard deviation of duration (not reported in the text) from the P value reported in the table. No adverse effect is mentioned or reported in the text | |

| Notes | The authors conclude that amantadine treatment was effective in controlling fever, but no other symptoms, possibly due to lack of sensitivity of surveillance methods. Although randomisation is clearly mentioned, no detailed description of allocation and concealment is given, making its assessment impossible | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hayden 1980.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo controlled treatment trial of inhaled (20 mg daily) amantadine | |

| Participants | 20 participants | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomised to receive either amantadine (n = 9, mean 19.1 years) or diluted water placebo (n = 11, mean age 20.3 years) within 48 hours of developing symptoms for a duration of 4 days | |

| Outcomes | Laboratory: influenza A/Texas/77[H3N2] and influenza A/USSR/77[H1N1] caused infection in the participants Efficacy : cases were ascertained clinically and immunologically and outcomes in all cases are presented as scores at day 2 of follow up for “respiratory illness” and “constitutional illness” which does not include ILI symptoms (Figures 1 and 2). Adverse effects reported in Table 2 are all local and due to the aerosol. We only included nasal burning as the most significant The study reported data on persistence and shedding of influenza A viruses from the upper airways. Viral titres were significantly lower in the treatment arm |

|

| Notes | The trial was clearly randomised, but no description of allocation and concealment is given making its assessment impossible. Additionally the rationale for distinguishing between constitutional and respiratory illness is unclear, results of outcomes are not clearly reported (mean scores only are given) and reasons for drop‐outs are not explained | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hayden 1981.

| Methods | A toxicity study reporting a randomised controlled trial undertaken in an unspecified period in USA and published in 1981 | |

| Participants | The setting is that of a state farm insurance company and the participants were 251 adult volunteers, aged between 18 to 65 (mean age of 32) | |

| Interventions | Two trials were carried out simultaneously, both involving rimantadine and amantadine. One was a low dose (200 mg daily of each drug, n = 52) and the other a higher dose trial (300 mg daily of each drug, n = 199). The low dose trial, however, has been excluded due to the absence of any 'cases' data, and the lack of outcomes | |

| Outcomes | Safety: systemic symptoms only with no other classification were noted, although not specified | |

| Notes | The practices of randomisation, allocation and concealment are not further defined, although all doses were stated as being administered by a project nurse. This is a poorly reported trial as no detailed classification of adverse effects is given, which is a strange practice for a toxicity study. Additionally, data reported in the text are not consistent with that in Table 1.c. Overall 41 out of 67 (61%) in the amantadine arm, 13 out of 66 in the placebo arm (20%) and 18 out of 63 in the rimantadine arm (29%) experienced adverse effects | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hayden 1986.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blind, placebo controlled treatment trial of oral rimantadine The trial took place in the universities of Virginia and Michigan in 1983 | |

| Participants | 14 adults with confirmed A/Bangkok/1/79(H3N2) influenza | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomised to receive either rimantadine 200 mg once daily (mean age 28 years) or placebo (mean age 23 years) for 5 days. Treatment started within 48 hours of symptom onset | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: nasal virus shedding, duration of fever (in hours) and symptom scores (presented broken down into systemic – headache, chills, malaise, etc. and respiratory). Average duration of fever in the rimantadine arm was 31 hours (SD 22 hours) and 68 (SD 8 hours) in the placebo group | |

| Notes | Although the trial is extremely clearly reported, no description of allocation and concealment is given | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hornick 1969a.

| Methods | Placebo controlled, double‐blind treatment comparison of amantadine 100 mg with lactose placebo twice daily for 10 days. 94 inmates were randomised to receive amantadine and 103 placebo in January 1968, during an epidemic of influenza A2 | |

| Participants | Participants were 153 inmates of 4 prisons: Jessup, Richmond, Walls and Wynne. Hornick 1969a reports results from the Jessup site (renamed Jessup/Maryland) | |

| Interventions | Amantadine n = 15 mean duration 66 hours, placebo n = 15, duration 92 hours, duration SD = 35 hours (for both arms). We transformed the duration data into 24‐hour days | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: influenza diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings. The study reported data on persistence and shedding of influenza A viruses from the upper airways | |

| Notes | The word “randomised” in not visible in the text, however denominators in each of the arms are highly suggestive of randomisation. No mention of the allocation procedure is made in the text, nor are drop‐outs mentioned. Overall results show that participants could be divided into "rapid resolvers" to treatment (whose illness resolved within 36 hours or less), medium resolvers (whose illness resolved within 24 to 36 hours) and slow resolvers (whose illness resolved in more than 36 hours) in both arms of the trial |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hornick 1969b.

| Methods | Placebo controlled, double‐blind treatment comparison of amantadine 100 mg with lactose placebo twice daily for 10 days. 94 inmates were randomised to receive amantadine and 103 placebo in January 1968, during an epidemic of influenza A2 | |

| Participants | Richmond site (renamed Hornick/Richmond) | |

| Interventions | Amantadine n = 21, mean duration 60.9 hours, placebo n = 28, mean duration 80.1 hours, duration SD = 33 hours (for both arms) | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: influenza diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings. The study reported data on persistence and shedding of influenza A viruses from the upper airways | |

| Notes | The word “randomised” in not visible in the text, however denominators in each of the arms are highly suggestive of randomisation. No mention of the allocation procedure is made in the text, nor are drop‐outs mentioned. Overall results show that participants could be divided into "rapid resolvers" to treatment (whose illness resolved within 36 hours or less), medium resolvers (whose illness resolved within 24 to 36 hours) and slow resolvers (whose illness resolved in more than 36 hours) in both arms of the trial |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hornick 1969c.

| Methods | Placebo controlled, double‐blind treatment comparison of amantadine 100 mg with lactose placebo twice daily for 10 days. 94 inmates were randomised to receive amantadine and 103 placebo in January 1968, during an epidemic of influenza A2 | |

| Participants | Walls site (renamed Hornick/Walls) | |

| Interventions | Amantadine n = 23 mean duration 65.1 hours, placebo n = 20, mean duration 88.3 hours, duration SD = 28 hours (for both arms) | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: influenza diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings. The study reported data on persistence and shedding of influenza A viruses from the upper airways | |

| Notes | The word "randomised" in not visible in the text, however denominators in each of the arms are highly suggestive of randomisation. No mention of the allocation procedure is made in the text, nor are drop‐outs mentioned. Overall results show that participants could be divided into "rapid resolvers" to treatment (whose illness resolved within 36 hours or less), medium resolvers (whose illness resolved within 24 to 36 hours) and slow resolvers (whose illness resolved in more than 36 hours) in both arms of the trial |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hornick 1969d.

| Methods | Placebo controlled, double‐blind treatment comparison of amantadine 100 mg with lactose placebo twice daily for 10 days. 94 inmates were randomised to receive amantadine and 103 placebo in January 1968, during an epidemic of influenza A2 | |

| Participants | Wynne site (renamed Hornick/Wynne) | |

| Interventions | Amantadine n = 17, mean duration 49.8 hours, placebo n = 17, mean duration 82.1 hours, duration SD = 39 hours (for both arms) | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: influenza diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings. The study reported data on persistence and shedding of influenza A viruses from the upper airways | |

| Notes | The word "randomised" in not visible in the text, however denominators in each of the arms are highly suggestive of randomisation. No mention of the allocation procedure is made in the text, nor are drop‐outs mentioned Overall results show that participants could be divided into "rapid resolvers" to treatment (whose illness resolved within 36 hours or less), medium resolvers (whose illness resolved within 24 to 36 hours) and slow resolvers (whose illness resolved in more than 36 hours) in both arms of the trial |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ito 2000.

| Methods | Controlled treatment trial of the efficacy of amantadine during the 1999 A/Sidney/05/97 influenza season. The trial was carried out in Japan among clinic attenders within 48 hours of testing positive for influenza. Allocation is described only as semi‐randomised. Follow up is not described | |

| Participants | 49 people aged 35.6 (mean) with influenza took part No drop‐outs are mentioned | |

| Interventions | Participants were assigned to either oral amantadine 100 mg daily and standard medication (combination of antibiotics, NSAIDs, antihistamines and cough mixtures) or standard medication only for 4.2 + 1.2 days | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: maximum body temperature (in degrees C) after treatment in days Duration of fever > 37 ºC and > 38 in days Duration of aching in days Duration of fatigue in days | |

| Notes | The authors conclude that amantadine hastens significantly the resolution of fever > 38 ºC by 0.7 a day. Assessment of the trial was hampered by the limited information available in English | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Kantor 1980.

| Methods | Prophylaxis, double‐blind, randomised controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of oral amantadine compared to a (not further defined) placebo. The trial took place over the period 20 February to 7 March 1978 in the military barracks at Fort Sam Houston (FSH), Texas and the target serotype was A/USSR/77 | |

| Participants | Trial participants were 139 healthy paramedic recruits (mean age 22 years) | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomised to receive either amantadine 100 mg tablets twice daily (n = 64) or placebo (n = 62) | |