Abstract

Background

Mental health problems are common in primary care and mental health workers (MHWs) are increasingly working in this setting delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients. In addition to treating patients directly, the introduction of on‐site MHWs represents an organisational change that may lead to changes in the clinical behaviour of primary care providers (PCPs).

Objectives

To assess the effects of on‐site MHWs delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care on the clinical behaviour of primary care providers (PCPs).

Search methods

The following sources were searched in 1998: the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Specialised Register, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CounselLit, NPCRDC skill‐mix in primary care bibliography, and reference lists of articles. Additional searches were conducted in February 2007 using the following sources: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time series analyses of MHWs working alongside PCPs in primary care settings. The outcomes included objective measures of PCP behaviours such as consultation rates, prescribing, and referral.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed study quality.

Main results

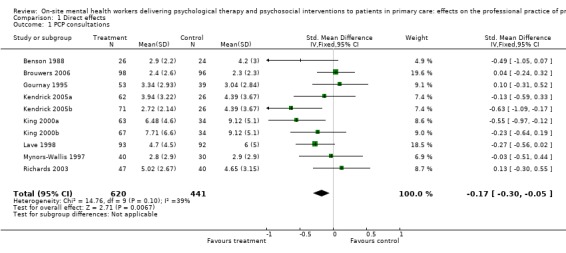

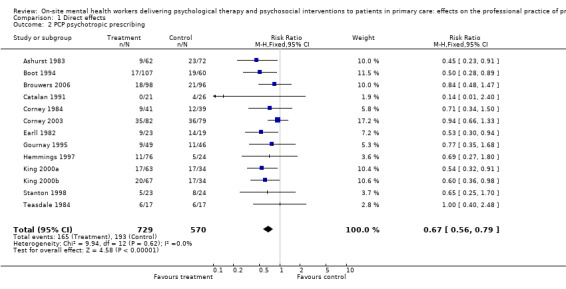

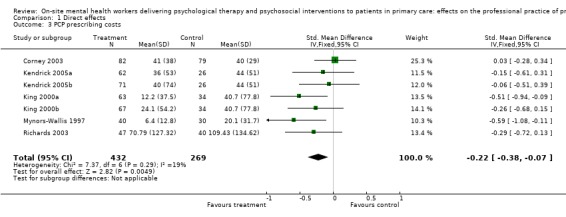

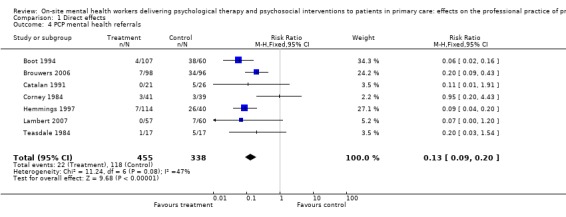

Forty‐two studies were included in the review. There was evidence that MHWs caused significant reductions in PCP consultations (standardised mean difference ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.05), psychotropic prescribing (relative risk 0.67, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.79), prescribing costs (standardised mean difference ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.07), and rates of mental health referral (relative risk 0.13, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.20) for the patients they were seeing. In controlled before and after studies, the addition of MHWs to a practice did not affect prescribing behaviour towards the wider practice population and there was no consistent pattern to the impact on referrals in the wider patient population.

Authors' conclusions

This review provides some evidence that MHWs working in primary care to deliver psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions cause a significant reduction in PCP behaviours such as consultations, prescribing, and referrals to specialist care. However, the changes are modest in magnitude, inconsistent, do not generalise to the wider patient population, and their clinical or economic significance is unclear.

Plain language summary

On‐site mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients in primary care: effects on the professional practice of primary care providers

Most people with mental health problems are treated by their family physician or general practitioner. Physicians will treat these problems, often without referral to mental health specialists, and at times the care is not consistent and could be improved. This review investigated whether having mental health workers on‐site to work with physicians at their offices would change the care that physicians provide. Forty‐two studies were reviewed in which on‐site mental health workers, such as counsellors or psychiatrists, worked alongside physicians to provide therapy to patients. The review found that when there were mental health workers on‐site, patients may reduce the number of visits to their doctors; doctors may reduce how often they refer patients to off‐site mental health specialists; doctors may reduce the number of drugs they prescribe to the patients who see the mental health workers; and the costs related to those drugs may be lower. However, these reductions were small and not found consistently in all the studies. The review also found that there may be little or no difference in how the doctors prescribe drugs or refer patients who have mental health problems but are not seeing the on‐site mental health workers. It is also not known what the effect of on‐site mental health workers had on how well physicians recognised and diagnosed mental health problems.

Background

In most healthcare systems primary care providers (PCPs) act as 'gatekeepers' to care in specialist settings (WHO 2001). Research indicates that the vast bulk of mental health problems in the community are dealt with by PCPs without referral to mental health specialists; and there is also evidence that the care provided by PCPs is variable, with significant room for improvement (Gilbody 2003; Goldberg 1992).

In response, mental health workers (MHWs) from a variety of disciplines are increasingly bringing their specialist skills into primary care to provide a range of interventions to patients, including psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions (Sibbald 1993). In addition to their role in treatment provision, the addition of an on‐site MHW represents an organisational change which may lead to changes in professional roles, the alteration of established clinical routines, and improvements in the clinical practice of PCPs.

There are a number of different models of the interface between MHWs and PCPs (Bower 2005; Gask 1997; Pincus 1987). The mechanisms of change by which MHWs may change PCP behaviour range from specific education and skill sharing between professionals to more diffuse processes, such as raising the profile of mental health in the primary care setting. Some models are organised such that the PCP refers the patient to the MHW, who assumes responsibility for the management of the patient's mental health problem by providing psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions. This way of working has been described as a 'replacement' model (Bower 2005). In this model, the main focus of interest concerns the effects of the direct provision of psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions on patient outcomes. Any changes in the behaviour of the PCP are viewed as a beneficial 'side effect' of the direct treatment function of the MHW. Nevertheless, these 'side effects' may have a beneficial impact on the overall costs of mental health care and the workload of PCPs. For example, referral of patients to on‐site MHWs operating in a replacement model may reduce both consultation rates with the PCP (thus freeing up clinical time for other duties) and prescribing of psychotropic medication (thus reducing the overall costs of care). The costs of employing on‐site MHWs in a replacement model is sometimes hypothesised to be recouped from the savings associated with these changes. Medical utilisation may decrease as a result of the MHW intervention if the psychological therapy or psychosocial intervention leads to changes in patients' mental health, social function, or need for care. This is referred to as a 'cost offset' (Fiedler 1989) and has been a significant feature of the literature on psychological therapies both generally and in primary care following the introduction of large numbers of MHWs in this setting (Martin 1985; Mumford 1984; Pharoah 1996). Cost offset reflects an economic perspective on service delivery since the focus is on reduction in health service utilisation, rather than quality of care or patient outcomes.

In other models, the PCP remains at the forefront of mental health care. In this case the main aim of the MHW is to support the PCP's management of the patient's mental health problem through education, advice, and support to the PCP (although the MHW may, in addition, provide some direct intervention to patients). These models have been described as 'consultation‐liasion' or 'collaborative care' (Bower 2005). Although MHWs and PCPs in a replacement model will interact and collaborate in informal ways (through common medical records, opportunities to discuss potential referrals, or informal discussions about patients), such interactions are explicit and standardised in consultation‐liaison and collaborative care. Because such models explicitly seek to change the clinical behaviour of PCPs, they are generally much more complex interventions involving behaviour change interventions with the PCP (Bower 2002). The effects of these models are the subject of separate future reviews (Fletcher 2007; Parker 2008).

This review sought to determine the effects of a replacement model by systematically reviewing evidence on the influence of MHWs on the clinical practice of PCPs. On‐site MHWs functioning in a replacement model potentially have two different effects on the behaviour of the PCP. Direct effects involve changes in PCP behaviour towards clients under the direct clinical care of the on‐site MHW. For example, does referring a patient to a clinical psychologist for psychological therapy change the likelihood that a PCP will prescribe antidepressant medication for that patient compared to patients who remain under the care of the PCP? Direct effects will largely reflect the impact on the PCP of referring their patient to an MHW.

Indirect effects are changes in PCP behaviour which occur in the wider primary care population, not just for those patients who were referred to MHWs. For example, does the addition of a clinical psychologist working on‐site in primary care change the overall prescribing of antidepressants by the PCPs within that organisation for their entire practice population? Indirect effects indicate whether the presence of a MHW has a more general effect on PCP behaviour.

Objectives

To determine the direct and indirect effects of on‐site mental health workers (MHWs) delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care on the clinical behaviour of primary care providers (PCPs).

Investigation of direct effects involved comparison of PCP behaviour towards patients who were allocated to an on‐site MHW for psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions with those patients who remained under the care of the PCP.

Investigation of indirect effects involved comparison of PCP behaviour towards patient populations in practices, clinics, or other primary care organisations with or without access to on‐site MHWs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled before and after studies (CBAs), and interrupted time series (ITS).

Types of participants

Primary care providers. In order to ensure comparability of interventions, the review was restricted to PCPs who fulfilled the following definition:

'PCPs are medical health care professionals providing first contact and on‐going care to patients, regardless of the patient's age, gender or presenting problem'.

Types of interventions

For the purposes of the present review, the addition of the MHW on‐site in primary care was the intervention, rather than the particular therapeutic approach taken by that worker in his or her management of individual patients.

MHWs working on‐site in primary care settings differ in terms of experience, training, therapeutic approach, funding, and relationship with the PCP (Sibbald 1993). Mental health interventions may be conducted by a wide range of staff with an equally wide range of qualifications and experience: practice counsellors, social workers, psychiatric or non‐psychiatric nurses, psychiatrists, psychotherapists, psychologists, clergy, and lay volunteers. Equally, the interventions may vary from psychotherapy and counselling to broader psychosocial interventions such as occupational therapy and social casework. PCPs may take on a specialist MHW role and provide psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions with additional training and a change in clinical role. Furthermore, the patient groups served by these individuals may differ widely. For the purposes of the review, the main requirements for the interventions to be included were:

(1) psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions provided by an on‐site MHW as a separate and distinct activity and not solely part of normal primary care consultations;

(2) the MHW was employed by or attached to the PCP organisation and worked on‐site i.e. the PCP and MHW worked for at least part of the time in geographical proximity and as part of the same clinical team.

For the purposes of the review, psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions were defined broadly. Psychological therapy refers to formal treatments based on a theory of psychological functioning; whereas psychosocial interventions represent less specific interventions designed to improve mental health through general support, advice, and encouragement.

Interventions where the MHW additionally provided behaviour change interventions directly to the PCP (such as provision of guidelines or in‐practice training), or where the MHW provided psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions as part of a wider quality improvement intervention which included behaviour change interventions delivered directly to the PCP, were excluded from the review. These interventions will be the subject of future reviews (Fletcher 2007; Parker 2008).

Psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care based on the use of technology such as screening tools, computerised aids, or self‐help interventions, without the use of a specific MHW, were excluded from the present review.

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures used in the review for the analysis of both direct and indirect effects included the following objective PCP clinical behaviours. Although some of these behaviours may reflect, in part, the behaviour of the patient (for example adherence to medication, primary care consultations), PCPs have an important role in determining such patient behaviours and thus the PCP clinical behaviours were considered relevant for the review.

(1) Diagnostic behaviour ‐ this included both the accuracy of specific psychiatric diagnoses or more general detection of disorder i.e. whether a patient was recognised as 'psychiatrically distressed' (Marks 1979). It was hypothesised that recognition and diagnosis would increase with the presence of a MHW.

(2) Prescribing behaviour ‐ this involved overall prescribing rates and costs, types of prescription, patient adherence to medication, and the overall adequacy of medication compared with clinical guidelines. It was hypothesised that prescribing would decrease with the presence of a MHW.

(3) Referral behaviour ‐ this involved off‐site referrals (both to psychiatric and non‐psychiatric agencies), laboratory tests and investigations, and overall referral costs. It was hypothesised that referrals would decrease with the presence of a MHW.

(4) Consultations ‐ in the review a consultation referred to visits by patients to the PCP or other primary care staff (such as primary care nurses) and the associated costs of these visits. All consultations (both mental health, non‐mental health, and mixed) were included, where reported. Visits to specialist staff (including other mental health providers) were labelled as referrals in the present review. It was hypothesised that consultations would decrease with the presence of a MHW.

Although outcomes involving changes in the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of PCPs were of potential relevance, the present review focussed on objective measures of PCPs' actual clinical behaviours rather than psychological characteristics which may potentially impact on those behaviours.

Patient mental health outcomes (for example scores on standardised depression questionnaires) are of obvious relevance to the evaluation of the cost‐effectiveness of MHWs delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care. However, the present review was restricted to the impact of MHWs on the behaviour of the PCP, and studies examining patient mental health outcomes only were excluded.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search strategy used in 1998 is shown in Appendix 1. These searches were augmented in February 2007 through searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library) to cover the period 1998 to 2007. An example of the search strategy is outlined below, and the full strategies are listed in Appendix 2.

CENTRAL

#1 MeSH descriptor Primary Health Care explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Physicians, Family explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Family Practice explode all trees #4 family near/2 pract* #5 general near/2 pract* #6 primary near/2 care #7 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) #8 counsel* #9 psychotherap* #10 clin* near/2 psy* #11 beh* near/2 therap* #12 group near/2 therap* #13 psychoanal* #14 psychiat* #15 cog* near/2 therap* #16 psychodynam* #17 MeSH descriptor Counseling explode all trees #18 MeSH descriptor Psychotherapy explode all trees #19 MeSH descriptor Psychology, Clinical explode all trees #20 MeSH descriptor Mental Health explode all trees #21 MeSH descriptor Mental Disorders explode all trees #22 (#8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21) #23 (#7 AND #22) #24 (#23), from 1998 to 2007

Data collection and analysis

A single review author (PB) read all the abstracts or full articles of the citations retrieved from the searches to identify potentially relevant studies. These publications were then independently read by both review authors who included studies that met the relevant criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Information concerning each study was extracted independently by both authors using a modified version of the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) checklist (http://www.epoc.cochrane.org/Files/Website%20files/Documents/Reviewer%20Resources/datacollectionchecklist.pdf). Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

EPOC quality criteria for RCTs involve consideration of unit of allocation and analysis, concealment of allocation, follow‐up rates, blinding, comparability of groups at baseline, reliability of outcome assessment, and protection against contamination. For inclusion in the review, CBAs must include contemporaneous data collection and the use of appropriate control groups. Quality criteria include baseline measurement in intervention and control groups, comparability of characteristics of intervention and controls, blinded assessment of primary outcome, protection against contamination, follow‐up rates, and reliability of outcome assessment. For inclusion in the review, ITSs must include an intervention delivered at a defined point in time, contemporaneous data collection, and the presence of more than three data points before and after the intervention. Quality criteria include protection against secular change, presence of sufficient data points before and after the intervention, formal test for trend, data collection uncontaminated by the intervention, data identical before and after the intervention, blinded assessment of outcome, reliable outcomes, and completeness of the data set (Bero 2000).

As noted earlier, the review included examination of both direct and indirect effects. The examination of direct effects is amenable to RCTs. However, a number of CBAs of direct effects were also reported. Given the weakness of the CBA design and the availability of a significant number of RCTs, CBA studies of direct effects have been identified and extracted into tables but the data have not been presented in the text and have not been used in the interpretation of the main findings. In the examination of indirect effects, the use of an RCT design is potentially problematic and the proportion of CBA studies is much higher. Therefore, CBA studies have been presented and analysed fully in the examination of indirect effects.

Meta‐analysis was conducted where multiple trials were reported examining the same outcome, and outcomes were reported in a standardised fashion suitable for pooling. The following data were used for the pooled analysis.

PCP consultations were pooled when the data were reported as mean number of consultations (with a standard deviation). Trials reporting consultation outcomes in alternative formats (for example medians, range of consultations, costs of consultations, or means without standard deviations) were excluded from the pooled analysis and reported narratively.

Psychotropic prescribing data were pooled when the data were reported as the percentage of patients in each group taking psychotropic medication. Where different types of psychotropic prescriptions were distinguished in the same paper (for example antidepressants, anxiolytics), a decision was made to include the most frequently reported psychotropic prescriptions in the pooled analysis.

Costs of prescribing were pooled when data were reported as mean cost of prescribing (with a standard deviation).

Mental health referrals were pooled when the data were reported as the percentage of patients in each group referred to a mental health professional other than the MHW involved in the intervention. Trials reporting mental health referral outcomes in alternative formats (for example mean number of referrals) were excluded from the pooled analysis and reported narratively.

Where two comparisons from the same trial were included in a meta‐analysis, the sample size in the control group was halved to avoid a unit of analysis error. The proportion, or mean outcome, in the control group was not changed.

For the pooled analyses, relative risks (RR) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes and standardised mean differences (SMD) for continuous outcomes. Although the same outcome (number of consultations) was used in the pooled analysis of consultation rates it should be noted that this outcome relates to a clinical behaviour which is a function of time. Since the included studies calculated outcomes over varying time periods, the SMD was reported for consultations. It should be noted that cost data are sometimes skewed and demonstrate much higher levels of variability than clinical outcomes, and caution must be exercised in the interpretation of statistical significance in single studies reporting cost data, and in the interpretation of SMD in meta‐analysis of cost data.

Heterogeneity among the study results was assessed using the Chi2 test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic. Where heterogeneity was low to moderate (I2 < 50%), a fixed‐effect model was reported. Otherwise a random‐effects model was used.

In accordance with EPOC guidelines, all results (both those included in the meta‐analyses and those excluded) were also presented in the 'Comparisons and data' tables as 'Other data'. For all data, the following statistics were computed.

Absolute change (mean or proportion in experimental group minus control).

Relative percentage change (absolute change divided by post‐test score in the control group).

Absolute change from baseline (pre‐intervention to post‐intervention changes in both groups).

Difference in absolute change from baseline.

In studies without baseline data, only absolute change and relative percentage change were calculated.

Results

Description of studies

Forty‐two studies comparing MHW and usual PCP care were included in the review; four were included in the same two papers (Kendrick 2005a; Kendrick 2005b; King 2000a; King 2000b). Thirty‐three were studies of direct effects and nine examined indirect effects. One hundred and fifty‐four studies were excluded as they met several inclusion criteria but not all (for example, trials of MHWs in primary care that failed to report objective PCP behaviours). These trials are listed in the excluded studies section.

Study populations

Generally, as PCPs were not the main focus of the studies, only very basic information was available on the PCP characteristics. Thirty‐five studies involved PCPs from the UK, two from the United States, and one each from Australia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, Netherlands, and West Germany. PCPs were general practitioners and family physicians in all the studies.

Information was only routinely provided on patients participating in the studies of direct effects. However, studies could be broadly categorised according to whether they involved professionals managing common mental health problems (for example anxiety and depression), which represented the bulk of the studies, and those involving professionals dealing with patients with more severe and enduring disorders (Bruce 1998; Hunter 1983; Wells 1992). Of the studies in common mental health problems, two dealt specifically with patients identified as high utilisers of medical care (Benson 1988; Sumathipala 2000) and two studies were conducted in patients with chronic illness (Basler 1990; Spurgeon 2007).

In most randomised studies of direct effects patients were recruited by the participating PCP, although some used alternatives such as patients recruited through screening in the primary care centre. The types of patients recruited to the trials varied. Some studies used specific patient groups identified through screening procedures. These included specific diagnostic groups (such as DSM‐IIIR major and minor depression), problem types related to the intervention provided by the MHW (for example neuroses amenable to behavioural treatment, marital problems), or other groups (such as high utilisers of services or frequent attenders). Other studies recruited patients identified by the PCP as requiring psychological therapy or psychosocial intervention and thus included a heterogeneous mixture of patients.

Interventions

The studies involved a variety of MHWs including: counsellors (16 studies); psychologists (11 studies); psychiatrists (five studies); community psychiatric nurses (seven studies), nurse therapists (one study), practice nurses (one study), and social workers (one study). In two studies, the MHW profession was not clear (Lambert 2007; Walker 1989). Some studies examined more than one type of therapist, or treatments provided by therapists working together. Psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions provided by these MHWs included non‐directive counselling, behaviour therapy, cognitive‐behaviour therapy, cognitive‐analytic therapy, brief dynamic psychotherapy, problem solving therapy, interpersonal therapy, facilitated self help, occupational therapy, practice‐based psychiatric clinics, and social casework.

Risk of bias in included studies

Studies of direct effects

Twenty‐five studies of direct effects were RCTs. Concealment of allocation was adequate in 10 studies (Brouwers 2006; Corney 1984; Corney 2003; Harvey 1984; Kendrick 2005a; Kendrick 2005b; King 2000a; King 2000b; Richards 2003; Sumathipala 2000), unclear from the information provided in 12 studies (Boot 1994; Brodaty 1983; Catalan 1991; Earll 1982; Ginsberg 1984; Gournay 1995; Lambert 2007; Lave 1998; Mynors‐Wallis 1997; Robson 1984; Stanton 1998; Teasdale 1984), and the allocation procedure was considered open to bias in three studies (Ashurst 1983; Benson 1988; Hemmings 1997). There were eight studies of direct effects using a CBA design (Ashworth 2000; Basler 1990; Blakey 1986; Brantley 1986; Bruce 1998; Lyon 1993; Martin 1985; Spurgeon 2007). As noted above, details have been provided in the tables but these studies were not considered further in the text.

Although PCP behaviours were assessed objectively through medical record searches and chart reviews, the reliability of data gained through medical record searches and chart reviews was not assessed. Because patients were the unit of allocation in these studies of direct effects, the possibility of indirect effects associated with the presence of a MHW in the practice meant that contamination was always possible (whether the study was an RCT or CBA). Although a number of studies did report power analyses these were always related to the clinical outcome data rather than the PCP behaviours analysed in the present review, so their utility is unclear.

Studies of indirect effects

One RCT of indirect effects was identified (Lester 2007) and allocation concealment was adequate. There were eight studies of indirect effects using a CBA design (Baker 1996; Coe 1996; Hunter 1983; Pharoah 1996; Simpson 2003; Tarrier 1983; Walker 1989; Wells 1992). In the CBA studies, extensive information concerning the comparability of the sites chosen as controls was provided in two studies (Baker 1996; Simpson 2003). One used random selection of controls from a sample but did not provide any descriptive statistics (Pharoah 1996). Other studies described qualitative similarities between practices (Hunter 1983; Tarrier 1983; Walker 1989) or used practices in the same geographical area (Coe 1996; Wells 1992). The comparability of control and intervention practices in terms of outcome variables at baseline was examined statistically in only three studies (Hunter 1983; Pharoah 1996; Simpson 2003) and confirmed in two (Pharoah 1996; Simpson 2003). Four studies provided data on baseline measures without statistical testing (Coe 1996; Baker 1996; Tarrier 1983; Walker 1989).

In the indirect studies, most of the PCP behaviours were assessed objectively and the reliability was enhanced through the use of automated recording systems. Practices were the unit of allocation and control practices were specifically chosen so as not to have access to the intervention under test.

Effects of interventions

Studies of direct effects

Consultations

Ten RCTs provided data for the pooled analysis of the effects of an on‐site MHW on consultation rates, involving 1061 patients (Benson 1988; Brouwers 2006; Gournay 1995; Kendrick 2005a; Kendrick 2005b; King 2000a, King 2000b, Lave 1998; Mynors‐Wallis 1997; Richards 2003). The test for heterogeneity was not significant (Chi2 = 14.76, df = 9, P = 0.10, I2 = 39.0%). Overall, consultation rates for patients under the care of a MHW were significantly lower than for patients under usual care (SMD ‐0.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.30 to ‐0.05).

Of those studies excluded from the pooled analysis, consultation rates were significantly lower in the intervention group in three out of seven studies that reported the significance of post‐intervention differences (Robson 1984; Sumathipala 2000; Teasdale 1984). No significant difference was found in the remaining studies (Ashurst 1983; Boot 1994; Corney 1984; Earll 1982). Five studies did not report tests of statistical significance (Catalan 1991; Corney 2003; Ginsberg 1984; Harvey 1998; Stanton 1998); in four, consultation rates or consultation times were lower in the intervention group (Catalan 1991; Corney 2003; Ginsberg 1984; Harvey 1998) and in one the rate was higher in the intervention group (Stanton 1998).

Prescribing

Thirteen RCTs provided data for the pooled analysis of the effects of an on‐site MHW on psychotropic prescribing rates, involving 1299 patients (Ashurst 1983; Boot 1994; Brouwers 2006; Catalan 1991; Corney 1984; Corney 2003; Earll 1982; Gournay 1995; Hemmings 1997; King 2000a; King 2000b; Stanton 1998; Teasdale 1984). The test for heterogeneity was not significant (Chi2 = 9.94, df = 12, P = 0.62, I2 = 0%). The proportion of patients under the care of an on‐site MHW prescribed psychotropic medication was significantly lower than for those under usual care (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.79).

One study excluded from the pooled analysis did not report tests of statistical significance but showed increases in the intervention group (Brodaty 1983).

Seven RCTs provided data for the pooled analysis of the costs of prescribing, involving 701 patients (Corney 2003; Kendrick 2005a; Kendrick 2005b; King 2000a; King 2000b; Mynors‐Wallis 1997; Richards 2003). The test for heterogeneity was not significant (Chi2 = 7.37, df = 6, P = 0.29, I2 =8.6%). Overall, prescribing costs for patients under the care of a MHW were significantly lower than for those under usual care (SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.07).

One study excluded from the pooled analysis showed significant reductions in psychotropic prescribing costs in the intervention group (Robson 1984).

Ten studies reported data on the effects on non‐psychotropic or combined prescribing. Four studies reported no significant differences in prescribing (Earll 1982; Ginsberg 1984; Richards 2003; Robson 1984). Of the six studies not reporting statistical significance, three reported higher rates or costs in the MHW group (Brodaty 1983; Brouwers 2006; Corney 2003) and three reported lower rates or costs (Harvey 1998; Kendrick 2005a; Kendrick 2005b).

Referral

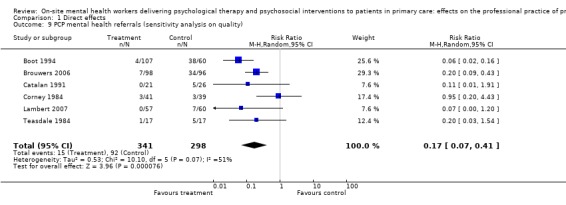

Seven RCTs provided data for the pooled analysis of mental health referrals, involving 793 patients (Boot 1994; Brouwers 2006; Catalan 1991; Corney 1984; Hemmings 1997; Lambert 2007; Teasdale 1984). The test for heterogeneity approached significance (Chi2 = 1.24, df = 6, P = 0.08, I2 = 46.6%). The proportion of patients under the care of a MHW referred for mental health care was significantly lower than for those under usual care (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.20, fixed‐effect model). A post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding the study with inadequate concealment (Hemmings 1997) reported similar results (Chi2 = 10.10, df = 5, P = 0.07, I2 = 50.5%; RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.41, random‐effects model).

Of those studies excluded from the pooled analysis, one found no significant difference (Richards 2003); five studies did not report tests of statistical significance but found lower mean referrals and costs in the intervention group (Harvey 1998; Kendrick 2005a; Kendrick 2005b; King 2000a; King 2000b).

Four studies examined the effect on non‐mental health referral. Three reported very similar mean referrals in intervention and control groups (Brouwers 2006; King 2000a; King 2000b) while one reported slightly higher proportions of referrals in the control group (Lambert 2007).

Seven studies examined the effect on overall referral, including both mental health and non‐mental health patients. One found no significant differences between groups (Earll 1982). The other studies did not report tests of statistical significance. One reported a lower rate of referral in the intervention group (Harvey 1998), two reported lower costs in the intervention group (King 2000a; King 2000b), and three reported a higher rate of referral in the intervention group (Kendrick 2005a; Kendrick 2005b; Stanton 1998).

Studies of indirect effects

Consultations

One RCT found no significant difference in primary care consultation costs (Lester 2007).

Prescribing

One RCT found no significant difference in combined psychotropic and non‐psychotropic drug costs (Lester 2007).

Four CBA studies found no significant differences in rates of psychotropic prescribing (Baker 1996; Coe 1996; Pharoah 1996; Simpson 2003).

Referral

One RCT examined the effects on referrals (Lester 2007) and found largely similar rates of referrals but increases in referrals to psychiatrists and an overall increase in costs. The same study also reported effects on non‐mental health referrals and costs and found reduced rates and costs in the intervention group.

Six CBA studies examined the effects on mental health referrals (Baker 1996; Coe 1996; Hunter 1983; Tarrier 1983; Walker 1989; Wells 1992). In one study the intervention group had higher rates of referral to clinical psychology services, but that there were no significant differences in rates of referral to other services (Baker 1996). A second study found higher referral rates to psychiatry in the intervention group before the intervention and lower rates after the intervention (Coe 1996). Intervention practices also had lower referral rates to community mental health teams. A third study found an increased referral rate of chronic psychiatric cases to both outpatient and inpatient facilities in the intervention group (Walker 1989). In a fourth study, the intervention reduced overall referrals to psychiatry, first referrals, and emergency referrals, but had no effect on re‐referrals (Wells 1992). In a further two studies, there were conflicting results in the different intervention practices studied with some outcomes showing increases and others no change in mental health referrals (Hunter 1983; Tarrier 1983).

Discussion

Literature search

The literature search was restricted to English language publications. At present it is not known whether there is a significant foreign‐language literature relating to these issues. Future updates of the review may benefit from inclusion of studies without language restriction and searches of the NHS Economic Evaluation Database for further studies of cost effectiveness.

Analysis and outcomes

As noted in the introduction, the perspective taken in this review is related to issues of cost offset, which is concerned with the effects of mental health workers on service utilisation rather than issues of quality of care or patient outcomes. Service utilisation was reported as a secondary outcome in most of the studies included in the present review. It is likely that decisions concerning the provision of MHWs in primary care, in replacement models, will depend crucially on the clinical or cost effectiveness of the psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions that they provide in terms of patient outcomes (such as symptoms and perceived distress). Many of the direct studies included in the review reported data on patient outcomes; and reviews of the effects of MHWs in primary care on patient outcomes are available (Bower 2006; Brown 1995; Churchill 1999; Friedli 1996; Schulberg 2002). However, the present review was focussed on a second issue, the influence of MHWs on PCP behaviour and the consequent resource use and costs of mental health care in primary care.

Although patient outcomes are important, it should be noted that the effects examined in the present review are important determinants of the overall cost effectiveness of MHWs in primary care, and thus may inform decision making alongside studies of patient outcome. Adherents of the replacement model suggest that the costs of provision of on‐site MHWs will be recouped from savings in health service utilisation, although the cost offset may not always be sufficient to overcome the costs of the MHW (Bower 2003).

It should be noted that changes in PCP behaviour, such as reductions in antidepressant prescribing, are generally viewed as positive from the cost‐offset perspective as they reduce the costs of care, all other things being equal. This assumption was present explicitly or implicitly in the bulk of the papers in the review. However, other commentators have pointed out that this assumption can be challenged as reductions may alter the overall cost effectiveness of care if the new pattern of care (for example the treatment provided by the MHW) achieves inferior clinical or quality outcomes to the treatment that it is replacing (Wessely 1996). The net effect of this on cost effectiveness will depend upon the relative magnitude of changes in costs and effectiveness. Consultation‐liaison and collaborative care models often seek to increase certain aspects of utilisation (such as medication).

Quality of included studies

Overall, the quality of studies of direct effects was variable. In part this reflects the fact that issues of relevance to the present review were often secondary to the main aim of the primary studies. This meant that information was often not presented on quality issues, for example the proportion of patients for whom information was available from medical records about PCP behaviour.

The examination of direct effects is amenable to RCT designs and the utility of CBA designs must be questioned. However, because care over a significant time span is a key characteristic of primary care, RCTs would benefit from longer follow up in order to examine the degree to which direct effects endure past the initial response of the PCP to the MHW referral.

The use of RCTs in the examination of indirect effects was rare and only one study using a cluster randomised design was identified (Lester 2007). This may be the result of the fact that the introduction of MHWs in primary care may reflect service innovation in individual primary care practices (Sibbald 1993) and practices that have independently introduced a MHW are unlikely to allow removal of the service for the purposes of research. CBA designs may have an important role as methods of evaluation where random allocation is unacceptable to participants. As differences between control and intervention groups in the characteristics of both providers and practices introduces selection bias, more consistent and detailed reporting of such characteristics would undoubtedly aid interpretation of results from such studies. It is likely that the interpretative difficulties caused by lack of control over allocation can only be offset by a significant weight of evidence from a number of CBA studies demonstrating consistent results. Studies in the present review (for example Baker 1996) have demonstrated that service evaluations using automated databases can provide both large samples of participating practices and examination of the long‐term effects of interventions. However, it is important that studies using a unit of allocation other than the patient (for example practitioner or practice) use appropriate statistical techniques to take into account the clustering of patients within practices or organisations.

It should be noted that data were lacking on the degree to which the PCPs and organisations in the studies were representative. It is likely that volunteers to such research studies differed from non‐volunteers. It is not clear how such bias would impact on the results. Volunteers to such studies may have more positive attitudes to mental health issues, or may have less positive attitudes (and thus are more likely to take part in studies where access to MHWs is part of the protocol). The majority of the studies in the review were conducted in the UK, which might limit the applicability of the studies to other contexts with different systems of primary care and mental health service delivery.

Results of the included studies

There was evidence from the pooled analysis that referral to a MHW caused reduction in PCP consultations. The effect size was 'small' according to current convention (Cohen 1988; Lipsey 1990). To give an example of the size of such an effect, patients in the control group of a UK study included in the review reported a mean of 9.12 consultations over 12 months, with a standard deviation of 5.1 (King 2000a; King 2000b). If the effect on consultations estimated in the meta‐analysis was robust over 12 months, this would equate to a reduction of approximately one consultation over that period that was associated with referral to a MHW. The modest nature of the difference was consistent with the heterogenous results from studies excluded from the pooled analysis. It should be noted that two of the studies (Benson 1988; Sumathipala 2000) examined interventions specifically aimed at those who frequently consulted in primary care and both reported positive results.

The pooled analyses also suggested that referral to a MHW reduced the likelihood of the PCP prescribing psychotropic medication and the overall costs of psychotropic prescribing. The impact on costs was again 'small' according to current convention (Cohen 1988; Lipsey 1990).

Finally, the pooled analyses suggested that referral to a MHW reduced the likelihood of the PCP referring to another MHW off site. Although the effect was of significant magnitude, it should be noted that the effects included in this analysis were highly heterogenous; the largest effect was found in a study which failed to use adequate concealment of allocation (Hemmings 1997). However, most of the studies not included in the pooled analysis also showed reductions, and a post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding the inadequately concealed study made little difference to the results.

In terms of the indirect effects, four CBA studies were consistent in showing that there is no statistically significant reduction in psychotropic prescribing in the primary care population associated with an on‐site MHW, although the possibility of bias remains with this type of design. In terms of mental health referrals, the evidence is mixed, with some studies reporting decreases in referral rates and some studies finding that the intervention may actually increase certain types of mental health referrals.

These observed outcomes of the replacement model seem reasonable to the degree that an on‐site MHW provides an accessible alternative to off‐site referral and medication for an individual patient. Given the modest direct effects on PCP behaviour, it would be expected that indirect effects would be rare. Indeed, the presence of an on‐site MHW may sometimes increase referral rates, possibly through sensitising the PCP to psychological and psychiatric problem presentations which cannot be managed within the resources available to the on‐site MHWs.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence presented provides some support for the hypothesis that MHWs providing psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions on‐site in primary care cause reductions in consultation rates, psychotropic prescribing, and mental health referrals among patients treated by the MHW. However, the effects are modest. There is evidence that on‐site MHWs do not impact on prescribing behaviour towards the wider practice population. The impact on referral rates is very inconsistent and no firm conclusions can be stated.

Overall, the present evidence suggests that on‐site MHWs are associated with changes in PCP behaviour. The evidence does not support the addition of MHWs to primary care teams with the aim of reducing demand on PCPs or achieving enduring changes in their clinical behaviour which will generalise to the wider practice population.

Implications for research.

Evaluation of the effects of MHWs on PCP behaviour would generally benefit from longer‐term follow up in order to determine the stability of any effects that are demonstrated and their deterioration over time. This is especially true of the indirect effects of MHWs, which may only occur when the MHW is a permanent and integral member of the primary care team.

The use of quasi‐experimental designs (CBAs and ITSs) and routinely collected data may provide a model for the efficient evaluation of indirect effects where participants (for example PCPs and MHWs) object to random allocation (Baker 1996). Greater detail concerning the baseline characteristics of participating practices and PCPs would allow more accurate judgement concerning the magnitude of selection bias in those variables.

The addition of MHWs to primary care teams is a complex intervention in the sense that it operates by altering inter‐professional as well as inter‐personal working relationships in ways which are poorly understood. Pragmatic RCTs treat such interventions as a 'black box' and generally give little information on how or why a particular intervention has (or has not) caused change. Future RCTs of MHW in primary care would benefit from the addition of qualitative research to increase knowledge about the conditions (relating to person, profession, and practice) which facilitate or prevent behaviour change in PCPs by MHWs. This might be facilitated if the interventions were more specifically linked to a model of PCP clinical behaviour and decision making in mental health work.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 June 2010 | Amended | Typos corrected |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1997 Review first published: Issue 3, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 November 2008 | New search has been performed | Review Updated Nov 2008 |

| 12 November 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Review has been divided into two reviews. The second will be published at a later date. |

| 10 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 1 February 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The review authors would like to thank Jeremy Grimshaw, Graham Mowatt, Alain Mayhew, and Emma Tavender of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group for advice and support throughout; Steve Rose (ex‐National Primary Care Research and Development Centre) and Doug Salzwedel for assistance with the literature searches; and Nick Kates, Marjukka Makela, Lisa Rubenstein, Luke Vale, Craig Ramsay, Sarah Hetrick, and Andy Oxman for their helpful comments on drafts of the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Original Search Strategy

| Given the broad range of study designs that are of relevance to Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) reviews (i.e. RCTs, CBAs and ITSs) and the expectation that data of relevance to the present review might be included in studies with a different primary aim (e.g. those evaluating clinical outcome of management by MHWs), it was decided to use a broad strategy for the identification of studies based on the types of mental health professionals in the primary care setting rather than specific methodological keywords (except when searching specialist mental health databases). The searches described below were therefore of relatively low specificity. MEDLINE (1966 ‐ 1998), PsycInfo (1984 ‐ 1998) and EMBASE (1980 ‐ 1998) were searched using the following terms: (family pract* OR general pract* OR primary care OR primary health care) AND (counsel* OR psychotherap* OR clin* psy* or beh* therap* OR fam* therap* OR group therap* OR psychoanal* OR psychiat* OR cog* therap* OR psychodynam*) The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register was searched using the following terms: ((primary near care) OR (general near pract*) OR (fam* near pract*)) AND (counsel* OR psychotherap* OR (clin* near psy*) OR (beh* near therap*) OR (fam* near therap*) OR (group near therap*) OR psychoanal* OR psychiat* OR (cog* near therap*) OR psychodynam*) The EPOC register was searched using the following terms: primary (near) care (or) general (near) practitioner (or) general (near) practice (or) family (near) practice (or) family (near) practitioner (or) family (near) medicine and psychiat* (OR) psycho* (OR) mental* (OR) emot* The Counselling in Primary Care Trust CounselLit database was searched using the following search terms: random OR meta OR trial OR effectiveness OR efficacy OR outcome OR control OR evaluation OR review OR comparative 2. The references lists of all relevant studies were searched for further studies. Searches for the initial review were conducted between 18‐22 June 1998. Papers of potential relevance that were identified after this date through means other than electronic database searching were added to the list of studies 'awaiting assessment'. Given the broad range of study designs that are of relevance to Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) reviews (i.e. RCTs, CBAs and ITSs) and the expectation that data of relevance to the present review might be included in studies with a different primary aim (e.g. those evaluating clinical outcome of management by MHWs), it was decided to use a broad strategy for the identification of studies based on the types of mental health professionals in the primary care setting rather than specific methodological keywords (except when searching specialist mental health databases). The searches described below were therefore of relatively low specificity. MEDLINE (1966 ‐ 1998), PsycInfo (1984 ‐ 1998) and EMBASE (1980 ‐ 1998) were searched using the following terms: (family pract* OR general pract* OR primary care OR primary health care) AND (counsel* OR psychotherap* OR clin* psy* or beh* therap* OR fam* therap* OR group therap* OR psychoanal* OR psychiat* OR cog* therap* OR psychodynam*) The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register was searched using the following terms: ((primary near care) OR (general near pract*) OR (fam* near pract*)) AND (counsel* OR psychotherap* OR (clin* near psy*) OR (beh* near therap*) OR (fam* near therap*) OR (group near therap*) OR psychoanal* OR psychiat* OR (cog* near therap*) OR psychodynam*) The EPOC register was searched using the following terms: primary (near) care (or) general (near) practitioner (or) general (near) practice (or) family (near) practice (or) family (near) practitioner (or) family (near) medicine and psychiat* (OR) psycho* (OR) mental* (OR) emot* The Counselling in Primary Care Trust CounselLit database was searched using the following search terms: random OR meta OR trial OR effectiveness OR efficacy OR outcome OR control OR evaluation OR review OR comparative 2. The references lists of all relevant studies were searched for further studies. Searches for the initial review were conducted between 18‐22 June 1998. Papers of potential relevance that were identified after this date through means other than electronic database searching were added to the list of studies 'awaiting assessment'. |

Appendix 2. Search strategies for the updated review

| CENTRAL #1MeSH descriptor Primary Health Care explode all trees #2MeSH descriptor Physicians, Family explode all trees #3MeSH descriptor Family Practice explode all trees #4family near/2 pract* #5general near/2 pract* #6primary near/2 care #7(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) #8counsel* #9psychotherap* #10clin* near/2 psy* #11beh* near/2 therap* #12group near/2 therap* #13psychoanal* #14psychiat* #15cog* near/2 therap* #16psychodynam* #17MeSH descriptor Counseling explode all trees #18MeSH descriptor Psychotherapy explode all trees #19MeSH descriptor Psychology, Clinical explode all trees #20MeSH descriptor Mental Health explode all trees #21MeSH descriptor Mental Disorders explode all trees #22(#8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21) #23(#7 AND #22) #24(#23), from 1998 to 2007 MEDLINE 1randomized controlled trial.pt. 2controlled clinical trial.pt. 3intervention studies/ 4experiment$.tw. 5(time adj series).tw. 6(pre test or pretest or (posttest or post test)).tw. 7random allocation/ 8impact.tw. 9intervention?.tw. 10chang$.tw. 11evaluation studies/ 12evaluat$.tw. 13effect?.tw. 14comparative studies/ 151 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 16Primary Health Care/ 17Family Practice/ 18(family adj2 pract$).mp. 19(general adj2 pract$).mp. 20(primary adj2 care).mp. 2116 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 22counsel$.mp. 23psychotherap$.mp. 24(clin$ adj2 psy$).mp. 25(beh$ adj2 therap$).mp. 26(group adj2 therap$).mp. 27psychoanal$.mp. 28psychiat$.mp. 29(cog$ adj2 therap$).mp. 30psychodynam$.mp. 31Counseling/ 32exp Psychotherapy/ 33Preventive Psychiatry/ or Community Psychiatry/ 34exp Psychology, Clinical/ 35exp Mental Health/ 36Mental Disorders/ 3722 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 3815 and 21 and 37 39limit 38 to yr="1998 ‐ 2007" EMBASE 1randomized controlled trial/ 2(randomised or randomized).tw. 3experiment$.tw. 4(time adj series).tw. 5(pre test or pretest or post test or posttest).tw. 6impact.tw. 7intervention?.tw. 8chang$.tw. 9evaluat$.tw. 10effect?.tw. 11compar$.tw. 121 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 13Primary Medical Care/ 14exp General Practice/ 15(family adj2 pract$).mp. 16(general adj2 pract$).mp. 17(primary adj2 care).mp. 1813 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 19counsel$.mp. 20psychotherap$.mp. 21(clin$ adj2 psy$).mp. 22(beh$ adj2 therap$).mp. 23(group adj2 therap$).mp. 24psychoanal$.mp. 25psychiat$.mp. 26(cog$ adj2 therap$).mp. 27psychodynam$.mp. 28exp Counseling/ 29exp PSYCHOTHERAPY/ 30exp PSYCHIATRY/ 31exp Mental Health/ 32exp Mental Disease/ 3319 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 3412 and 18 and 33 35limit 34 to yr="1998 ‐ 2007" CINHAL 1clinical trial/ 2(controlled adj (study or trial)).tw. 3(randomised or randomized).tw. 4(random$ adj1 (allocat$ or assign$)).tw. 5exp pretest‐posttest design/ 6exp quasi‐experimental studies/ 7comparative studies/ 8time series.tw. 9experiment$.tw. 10impact.tw. 11intervention?.tw. 12evaluat$.tw. 13effect?.tw. 1410 or 11 or 12 or 13 15exp Primary Health Care/ 16exp Family Practice/ 17(family adj2 pract$).mp. 18(general adj2 pract$).mp. 19(primary adj2 care).mp. 2015 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 21counsel$.mp. 22psychotherap$.mp. 23(clin$ adj2 psy$).mp. 24(beh$ adj2 therap$).mp. 25(group adj2 therap$).mp. 26psychoanal$.mp. 27psychiat$.mp. 28(cog$ adj2 therap$).mp. 29psychodynam$.mp. 30exp Counseling/ 31exp PSYCHOTHERAPY/ 32exp PSYCHIATRY/ 33exp Mental Health/ 34exp Mental Disorders/ 3521 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 3614 and 20 and 35 37limit 36 to yr="1998 ‐ 2007" PSYCINFO 1Clinical Trial/ 2exp Treatment Effectiveness Evaluation/ 3exp treatment outcomes/ 4experiment$.tw. 5(time adj series).tw. 6(pre test or pretest or (posttest or post test)).tw. 7intervention?.tw. 81 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9exp Primary Health Care/ 10exp General Practitioners/ 11exp Family Medicine/ 12exp Family Physicians/ 13(family adj2 pract$).mp. 14(general adj2 pract$).mp. 15(primary adj2 care).mp. 169 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 17exp Counseling/ 18exp Psychotherapy/ 19exp Psychiatry/ 20exp Mental Health/ 21exp Mental Disorders/ 22counsel$.mp. 23psychotherap$.mp. 24(clin$ adj2 psy$).mp. 25(beh$ adj2 therap$).mp. 26(group adj2 therap$).mp. 27psychoanal$.mp. 28psychiat$.mp. 29(cog$ adj2 therap$).mp. 30psychodynam$.mp. 3117 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 328 and 16 and 31 33limit 32 to yr="1998 ‐ 2007" 34cost offset.mp. 35exp "Costs and Cost Analysis"/ or exp Health Care Costs/ or exp Health Care Utilization/ or exp "Cost Containment"/ 36 34 or 35 37 8 or 36 38 16 and 31 and 37 39 limit 38 to yr="1998 ‐ 2007" 40 39 not 33 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Direct effects.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PCP consultations | 10 | 1061 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐0.30, ‐0.05] |

| 2 PCP psychotropic prescribing | 13 | 1299 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.56, 0.79] |

| 3 PCP prescribing costs | 7 | 701 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.38, ‐0.07] |

| 4 PCP mental health referrals | 7 | 793 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.09, 0.20] |

| 5 PCP consultations | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6 PCP prescribing | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6.1 PCP prescribing ‐ psychotropics | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6.2 PCP prescribing ‐ non‐psychotropic or combined prescribing | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7 PCP referrals | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7.1 Mental health referrals | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7.2 Non‐mental health referrals | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7.3 All referrals | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 8 Total costs | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 9 PCP mental health referrals (sensitivity analysis on quality) | 6 | 639 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.07, 0.41] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Direct effects, Outcome 1 PCP consultations.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Direct effects, Outcome 2 PCP psychotropic prescribing.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Direct effects, Outcome 3 PCP prescribing costs.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Direct effects, Outcome 4 PCP mental health referrals.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Direct effects, Outcome 5 PCP consultations.

| PCP consultations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study design | Outcomes | Results |

| Ashurst 1983 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations Average length of consultation | GP consultations 12 months post‐treatment Int 7 (n=112) Con 6.3 (n=121) Absolute change=0.7 Relative % change=11% Average length of consultation Int 10.4 (n=112) Con 10.1 (n=121) Absolute change=0.3 Relative % change=3% Total GP time Int 64 Con 59 Absolute change=5 Relative % change=9% Reported t=0.91, df=231, p=0.36 |

| Ashworth 2000 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | GP consultations 1 year comparison 2 Pre treatment Int 6.33 (5.67) (n=75) Con 1.6 (1.59) (n=75) Post treatment Int 7.08 (6.33) (n=75) Con 1.41 (1.27) (n=75) Absolute change post 5.67 Relative % change 402.1 Absolute change from baseline Int 0.75, Con ‐0.19 Difference in absolute change from baseline 0.94 GP consultations 2 year comparison 2 Pre treatment Int 6.33 (5.67) (n=75) Con 1.6 (1.59) (n=75) Post treatment 3.93 (3.58) (n=71) Con 1.71 (2.15) (n=63) Absolute change post 2.22 Relative % change 129.8 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐2.4, Con 0.11 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐2.51 GP consultations 1 year comparison 1 Pre treatment Int 7.23 (6.67) (n=30) Con 4 (3.98) (n=30) Post treatment Int 8.23 (7.54) (n=30) Con 5 (3.36) (n=30) Absolute change post 3.23 Relative % change 64.6 Absolute change from baseline Int 1, Con 1 Difference in absolute change from baseline 0 GP consultations 2 year comparison 1 Pre treatment Int 7.23 (6.67) (n=30) Con 4 (3.98) (n=30) Post treatment Int 4.74 (4.43) (n=27) Con 4.48 (3.88) (n=27) Absolute change post 0.26 Relative % change 5.8 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐2.49, Con 0.48 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐2.97 |

| Basler 1990 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | GP consultations 3 months pre‐treatment Int Pre 7.08 (3.43) (n=25?) Con Pre 6.15 (3.07) (n=20?) 3 months post‐treatment Int 3.90 (1.13) (n=25?) Con 7.8 (4.14) (n=20?) Absolute change=‐3.9 Relative % change=‐50% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐3.18 Con 1.65 Difference in absolute change from baseline=‐4.83 Reported chisq=22.43, df=1, p<0.01 |

| Benson 1988 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Consultations 12 months pre‐treatment Int 4.6 (2.8) (n=26) Con 5.8 (5.3) (n=24) 6 months pre‐treatment Int 5.5 (3.3) (n=26) Con 5.0 (3.4) (n=24) 1st 6 months during treatment Int 2.9 (2.2) (n=26) Con 4.2 (3.0) (n=24) Absolute change=‐1.3 Relative % change=‐31% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐1.7 Con ‐1.6 Difference in absolute change from baseline=‐0.1 2nd 6 months during treatment Int 2.5 (1.6) (n=26) Con 3.2 (2.8) (n=24) Absolute change=‐0.7 Relative % change=‐22% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐2.1 Con ‐2.6 Difference in absolute change from baseline=0.5 6 months post‐treatment Int 1.5 (1.5) (n=26) Con 3.1 (2.5) (n=24) Absolute change=‐1.6 Relative % change=‐52% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐3.1 Con ‐2.7 Difference in absolute change from baseline=‐0.4 Reported t=2.84, df=36, p<0.01 versus treatment group 12 months post‐treatment Int 1.6 (n=14) Con 3.0 (n=19) Absolute change=‐1.4 Relative % change=‐47% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐3.0 Con ‐2.8 Difference in absolute change from baseline=‐0.2 (s.d. not given) |

| Blakey 1986 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | Note: Data presented in form of tables only |

| Boot 1994 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Consultations 6 weeks Int 54/107 (51%) Con 39/60 (65%) Absolute change=‐14% Relative % change=‐22% Reported p=0.1 (chisq) |

| Brantley 1986 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | FP visits 12m pre treatment Int 9.14 (8.59) (n=21) Con 5.52 (4.25) (n=21) 12 months post‐treatment Int 5.95 (6.26) (n=21) Con 4.38 (3.35) (n=21) Absolute change=1.57 Relative % change=36% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐3.19 Con ‐1.14 Difference in absolute change=‐2.05 Int greater decrease than con (reported z=‐1.891, p<0.05) |

| Brouwers 2006 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | GP consultations Post treatment Int 2.4 (2.6) (n=98) Con 2.3 (2.3) (n=96) Absolute change post 0.1 Relative % change 4.3 GP surgery contacts Post treatment Int 5 (5.1) (n=96) Con 5.7 (3.3) (n=96) Absolute change post ‐0.7 Relative % change ‐12.3 GP telephone contacts Post treatment Int 0.7 (1.1) (n=96) Con 0.6 (1.3) (n=96) Absolute change post 0.1 Relative % change 16.7 GP home contacts Post treatment 0 (0.2) (n=96) Con 0 (0.5) (n=96) Absolute change post 0 Relative % change NA GP minor surgery contacts Post treatment Int 0.5 (0.8) (n=96) Con 0.5 (1) (n=96) Absolute change post 0 Relative % change 0.0 GP prescription contacts Post treatment Int 2.6 (4.1) (n=96) Con 3.3 (4.6) (n=96) Absolute change post ‐0.7 Relative % change ‐21.2 |

| Bruce 1998 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | GP mental health Pre treatment Int 1.6 (n=16) Con 3.3 (n=11) Post treatment Int 0.4 (n=16) Con 2.3 (n=11) Absolute change post ‐1.9 Relative % change ‐82.6 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐1.2, Con ‐1 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐0.2 p<0.05 GP physical health Pre treatment Int 3 (n=16) Con 3.2 (n=11) Post treatment Int 3.8 (n=16) Con 3.6 (n=11) Absolute change post 0.2 Relative % change 5.6 Absolute change from baseline Int 0.8, Con 0.4 Difference in absolute change from baseline 0.4 GP other Pre treatment Int 3.6 (n=16) Con 1.8 (n=11) Post treatment Int 2.8 (n=16) Con 1.5 (n=11) Absolute change post 1.3 Relative % change 86.7 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐0.8, Con ‐0.3 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐0.5 Practice nurse Pre treatment Int 14.8 (n=16) Con 8.1 (n=11) Post treatment Int 18.4 (n=16) Con 3.6 (n=11) Absolute change post 4.8 Relative % change 35.3 Absolute change from baseline Int 3.6 Con 5.5 Difference in absolute change from baseline‐1.9 Total GP Pre treatment Int 8.43 (n=16) Con 8.36 (n=11) Post treatment Int 6.93 (n=16) Con 7.73 (n=11) Absolute change post ‐0.8 Relative % change ‐10.3 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐1.5, Con ‐0.63 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐0.87 |

| Catalan 1991 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Median consultations 4 weeks Int 3 (n=21) Con 2 (n=26) 5‐10 weeks Int 2 (n=21) Con 3 (n=26) 11‐28 weeks Int 1 (n=21) Con 3 (n=26) |

| Corney 1984 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Note: No data presented although stated that no significant differences were found 12 months post treatment |

| Corney 2003 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | GP consultation 6 months Pre treatment Int 97.8% (n=91) Con 97.8% (n=89) Post treatment Int 92.7% (n=82) Con 98.7% (n=79) Absolute change Post treatment‐6 Relative % change ‐6.1 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐5.1, Con 0.9 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐6 PN consultation 6 months Pre treatment Int 48.4% (n=91) Con 57.3 (n=89) Post treatment Int 42.7% (n=82) Con 39.2% (n=79) Absolute change Post treatment 3.5 Relative % change 8.9 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐5.7, Con ‐18.1 Difference in absolute change from baseline 12.4 GP consultation 12 months Pre treatment Int 97.8% (n=91) Con 97.8% (n=89) Post treatment Int 90.7% (n=75) Con 95.6% (n=68) Absolute change Post treatment ‐4.9 Relative % change ‐5.1 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐7.1, Con ‐2.2 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐4.9 PN consultation 12 months Pre treatment Int 48.4% (n=91) Con 57.3% (n=89) Post treatment Int 34.7% (n=75) Con 35.3% (n=68) Absolute change Post treatment ‐0.6 Relative % change ‐1.7 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐13.7, Con ‐22 Difference in absolute change from baseline 8.3 |

| Earll 1982 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | GP consultations Treatment Int 3.4 Con 2.8 Absolute change=0.6 Relative % change=21% Reported n.s. 7m follow up Int 5.6 Con 5.2 Absolute change=0.4 Relative % change=8% Reported n.s. |

| Ginsberg 1984 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | Consultations 12 months pre‐treatment Int 5.7 (n=19) Con 6.4 (n=23) 12 months post‐treatment Int 4.4 (n=19) Con 7.0 (n=23) Absolute change=‐2.6 Relative % change=‐37% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐1.3 Con 0.6 Difference in absolute change from baseline=‐1.9 (no sds or tests reported) Home visits 12 months pre‐treatment Int 0.14 (n=19) Con 0.18 (n=23) 12 months post‐treatment Int 0.0 (n=19) Con 0.04 (n=23) Absolute change=‐0.04 Relative % change=‐100% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐0.14 Con ‐0.14 Difference in absolute change from baseline=0 (no sds or tests reported) Costs of GP visits 12 months pre‐treatment Int £8.00 (n=22) Con £9.00 (n=26) 12 months post treatment Int £6.27 (n=22) Con £9.10 (n=26) Absolute change=‐2.83 Relative % change=‐‐31% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐1.73 Con 0.1 Difference in absolute change from baseline=‐1.83 |

| Gournay 1995 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Consultations 6 months pre‐treatment Int 4.37 (3.46) (n=53?) Con 5.30 (4.01) (n=39) 6 months post‐treatment Int 3.34 (2.93) (n=53?) Con 3.04 (2.84) (n=39) Absolute change=‐0.3 Relative % change=‐10% Absolute change from baseline Int‐1.03 Con ‐2.26 Difference in absolute change from baseline=1.23 Authors reported that reduction in control significant over time (p<0.05), n.s. between int and con |

| Harvey 1998 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | Mean GP time 4 months Int 0.63 hours Con 1.50 hours Absolute change=‐0.87 Relative % change=‐58% (no s.d. or tests reported) Costs of GP time Int £15.75 Con £28.75 Absolute change=‐£13 Relative % change=‐45% |

| Kendrick 2005a | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | GP surgery consultations 26 weeks Post treatment Int 3.94 (3.22) (n=62) Con 4.39 (3.67) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment ‐0.45 Relative % change ‐10.3 GP surgery consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 81 (67) (n=62) Con 91 (76) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment ‐10 Relative % change ‐11.0 Home visits 26 weeks Post treatment Int 0.05 (0.28) (n=62) Con 0.04 (0.2) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 0.01 Relative % change 25.0 Home visits costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 3 (18) (n=62) Con 3 (12) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 0 Relative % change 0.0 CMHN telephone consultations 26 weeks Post treatment Int 0.63(1.76) (n=62) Con 0.27 (0.69) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 0.36 Relative % change 133.3 Telephone consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 15 (42) (n=62) Con 7 (16) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 8 Relative % change 114.3 PN surgery consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 0.4 (0.73) (n=62) Con 0.48 (0.7) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment ‐0.08 Relative % change ‐16.7 PN surgery consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 4 (8) (n=62) Con 5 (7) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment ‐1 Relative % change ‐20.0 |

| Kendrick 2005b | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | GP surgery consultations 26 weeks Post treatment Int 2.72(2.14) (n=71) Con 4.39 (3.67) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment ‐1.67 Relative % change ‐38.0 GP surgery consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 56 (44) (n=71) Con 91(76) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment ‐35 Relative % change ‐38.5 Home visits 26 weeks Post treatment Int 0.11(0.65) (n=71) Con 0.04 (0.2) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 0.07 Relative % change 175.0 Home visits costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 7 (41) (n=71) Con 3 (12) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 4 Relative % change 133.3 Telephone consultations 26 weeks Post treatment Int 0.49(1.58) (n=71) Con 0.27 (0.69) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 0.22 Relative % change 81.5 Telephone consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 12 (38) (n=71) Con 7 (16) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 5 Relative % change 71.4 PN surgery consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 0.56(1.08) (n=71) Con 0.48 (0.7) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 0.08 Relative % change 16.7 PN surgery consultations costs 26 weeks Post treatment Int 6 (11) (n=71) Con 5 (7) (n=51) Absolute change Post treatment 1 Relative % change 20.0 |

| King 2000a | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | GP surgery 12 months Post treatment Int 6.48 (4.6) (n=63) Con 9.12 (5.1) (n=67) Absolute change post ‐2.64 Relative % change ‐28.9 GP home visits 12 months Post treatment Int 0.03 (0.18) (n=63) Con 0.05 (0.27) (n=67) Absolute change post ‐0.02 Relative % change ‐40.0 PN 12 months Post treatment Int 0.69 (0.95) (n=63) Con 0.53 (1.1) (n=67) Absolute change post 0.16 Relative % change 30.2 |

| King 2000b | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | GP surgery 12 months Post treatment Int 7.71 (6.6) (n=67) Con 9.12 (5.1) (n=67) Absolute change post ‐1.41 Relative % change ‐15.5 GP home visits 12 months Post treatment Int 0.04 (0.27) (n=67) Con 0.05 (0.27) (n=67) Absolute change post ‐0.01 Relative % change ‐20.0 PN 12 months Post treatment Int 0.41 (0.68) (n=67) Con 0.53 (1.1) (n=67) Absolute change post ‐0.12 Relative % change ‐22.6 |

| Lave 1998 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | Non protocol consultations 12 months Post treatment Int 4.7(4.5) (n=93) Con 6 (5) (n=92) Absolute change post ‐1.3 Relative % change ‐21.7 Non protocol consultations costs Post treatment Int 308.04 (353.2) (n=93) Con 553.2 (490.48) (n=92) Absolute change post ‐245.16 Relative % change ‐44.3 |

| Lyon 1993 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | GP consultations 3 months pre‐treatment Int 8.6 (n=38) Con 9.1 (n=33) 3 months post‐treatment Int 4.6 (n=38) Con 7.8 (n=33) Absolute change=‐3.2 Relative % change=‐41% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐4.0 Con ‐1.3 Differences in pre‐post change=‐2.7 No tests reported |

| Martin 1985 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | GP consultations 12 months pre‐treatment Int 7.8 (n=87) Con 3.4 (n=87) 12 months post‐treatment Int 7.4 (n=87) Con 2.6 (n=87) Absolute change=4.8 Relative % change=185% Absolute change from baseline Int ‐0.4 Con ‐0.8 Difference in pre‐post change=0.4 No tests reported |

| Mynors‐Wallis 1997 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | GP consultations During treatment Int 2.2 (1.8) (n=40) Con 2.3 (1.5) (n=30) Absolute change=‐0.1 Relative % change=‐4% Reported p=0.844 4 months Int 2.8 (2.9) (n=40) Con 2.9 (2.9) (n=30) Absolute change=‐0.1 Relative % change=‐4% Reported p=0.975 Treatment plus follow up combined Int 5.0 (4.1) (n=40) Con 5.1 (3.7) (n=30) Absolute change=‐0.1 Relative % change=‐2% Reported p=0.914 Cost of consultations During treatment Int £28.1 (22.9) (n=40) Con £29.3 (19.2) (n=30) Absolute change=‐£1.2 Relative % change=‐4% p=0.844 Cost of consultations 4 months Int £36.2 (37.7) (n=40) Con £36.5 (37.5) (n=30) Absolute change=‐£0.3 Relative % change=‐1% p=0.975 Treatment and 4 months combined Int £63.9 (52.0) (n=40) Con £65.2 (46.9) (n=30) Absolute change=‐£1.3 Relative % change=‐2% p=0.914 |

| Richards 2003 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations and costs of consultations | GP consultations 12 months Post treatment Int 5.02 (2.67) (n=47) Con 4.65 (3.15) (n=40) Absolute change Post treatment 0.37 Relative % change 8.0 GP consultation costs 12 months Post treatment Int 57.45 (43.87) (n=47) Con 84.6 (55.92) (n=40) Absolute change Post treatment ‐27.15 Relative % change ‐32.1 Mean difference ‐27.15, 95% CI ‐48.44 to 5.87, p=0.013 |

| Robson 1984 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Consultations 10 weeks to 6 months Int (1‐2) 35 (3‐4) 20 (5+) 22 (n=77) Con (1‐2) 60 (3‐4) 40 (5+) 30 (n=130) Reported p=0.0008 by chisq test |

| Spurgeon 2007 | Controlled before‐after study | GP consultations | GP consultations 12 months Pre treatment Int 52.9 Con 42.18 Post treatment Int 42.5 Con 49.16 Absolute change post ‐6.66 Relative % change ‐13.5 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐10.4, Con 6.98 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐17.38 Home visits 12 months Pre treatment Int 0.5 Con 1.9 Post treatment Int 0.48 Con 1.86 Absolute change post ‐1.38 Relative % change ‐74.2 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐0.02 Con ‐0.04 Difference in absolute change from baseline 0.02 |

| Stanton 1998 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Consultations 6 months Int 0‐2 (30%) 3‐4 (22%) 5+ (35%) Missing (13%) (n=23) Con 0‐2 (46%) 3‐4 (25%) 5+ (12%) Missing (17%) (n=24) No tests reported |

| Sumathipala 2000 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Visits (adjusted means) 6 months Pre treatment Int 6.3 (4) Con 7.7(6.3) Post treatment (adjusted) Int 3.1 (n=34) Con 7.9 (n=34) Absolute change post ‐4.8 Relative % change ‐60.8 Absolute change from baseline Int ‐3.2, Con 0.2 Difference in absolute change from baseline ‐3.4 Difference in means 6.3 (95% CI 1.8 to 11.0, p<0.001) |

| Teasdale 1984 | Randomized controlled trial | GP consultations | Consultations During treatment Int 0.51 (n=17) Con 1.07 (n=17) Absolute change=‐0.56 Relative % change=‐52% Reported t=2.11, p<0.05 3 months Int 0.41 (n=17) Con 0.41 (n=17) Absolute change=0 Relative % change=0% No s.d.s or tests reported |

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Direct effects, Outcome 6 PCP prescribing.

| PCP prescribing | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study design | Outcomes | Results |

| PCP prescribing ‐ psychotropics | |||

| Ashurst 1983 | Randomized controlled trial | Psychotropic prescribing | % on tranquilisers 12 months post treatment Int 14.5% (n=62) Con 31.9% (n=72) Absolute change=‐17.4% Relative % change=‐55% Reported chisq=4.65, df=1, p=0.03 % on antidepressants 12 months post treatment Int 17.1% (n=41) Con 18.2% (n=55) Absolute change=‐1.1% Relative % change=‐6% Reported chisq=0, df=1, p=1.0 |