Abstract

Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) are some of the most significant pollutants in human serum, and are reported to be potentially toxic to humans. In this study, the binding mechanism of PFCAs with different carbon lengths to human serum albumin (HSA) was studied at the molecular level by means of fluorescence spectroscopy under simulated physiological conditions and molecular modeling. Fluorescence data indicate that PFCAs with a longer carbon chain have a stronger fluorescence quenching ability. Perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) and perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) had little effect on HSA. Fluorescence quenching of HSA by perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) was a static process that formed a PFCA–HSA complex. Electrostatic interactions were the main intermolecular forces between PFOA and HSA, while hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions played important roles in the combination of PFDA and HSA. In fact, the binding of PFDA to HSA was stronger than that of PFOA as supported by fluorescence quenching and molecular docking. In addition, infrared spectroscopy demonstrated that the binding of PFOA/PFDA resulted in a sharp decrease in the β-sheet and α-helix conformations of HSA. Our results indicated that the carbon chain length of PFCAs had a great impact on its binding affinity, and that PFCAs with longer carbon chains bound more strongly.

Keywords: perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs), human serum albumin (HSA), fluorescence, toxicity, carbon chain length, molecular docking

1. Introduction

Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs), such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), have been widely used in the manufacture of global consumer goods, including non-stick kitchen utensils, surface treatment agents, and surfactants [1,2]. Since 2000, their persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxicity have attracted global attention [3,4]. Low concentrations of PFCAs are detected in environmental media samples, wildlife, and even in human serum [5,6,7,8,9]. Most interestingly, PFCAs are mainly accumulated in plasma, liver, and kidney due to their protein affinity [10,11]. In recent years, many studies have been conducted to assess the potential impact of PFOA on human health [7,12,13,14]. However, owing to the lack of toxicological data for other PFCAs, the risk assessment of environmental pollution caused by PFCAs is still very limited.

The study of PFCA–protein interactions was first conducted in the 1950s with the objective of protecting bovine serum albumin (BSA) from denaturation by interaction with PFOA and subsequent precipitation [15]. Since organofluorine chemicals have been reported in human plasma [16], and PFCAs have been regarded as global pollutants, the interactions between PFCAs and proteins have once again captured the attention of researchers. So far, PFCA–protein binding properties have been used primarily to study the toxicity of PFCAs through direct or competitive binding tests. Many studies have used direct binding tests to discover the effects of interactions on protein structures and functions and the potential mechanisms [10,17,18,19,20]. Besides toxicity assessment, the binding of PFCAs to proteins was also studied to understand bioaccumulation, biotransformation, and elimination of PFCAs [3,21,22].

Serum albumin is the main binding target of PFCAs in vivo [23]. Two studies previously described by Han et al. [11], and Jones et al. [24] confirmed the interaction of PFCAs with serum albumin. Chen and Guo [23] studied the binding of five perfluorinated compounds to human serum albumin (HSA) via site-specific fluorescence, and found that these chemicals bind to HSA with similar affinity to fatty acids at the same sites. MacManus-Spencer et al. [25] compared three experimental methods to examine the binding of PFCAs to serum albumin, and pointed out that although fluorescence is an indirect method, it can provide a more comprehensive description of the nature of the interaction. Qin et al. [26] investigated the effect of PFCAs on BSA through fluorescence spectroscopy, and demonstrated that PFCAs did affect the structure of BSA, and that PFCAs with a longer carbon chain length had greater toxicity at lower concentrations. Our previous work investigated the effect of functional groups (carboxylate or sulfonate headgroup) of perfluorinated compounds on binding sites and binding affinities [27]. However, the interaction between PFCAs with different carbon chain length and transporters in aqueous media is still far from being fully understood, so this topic needs to be carefully explored from different perspectives.

Liu et al. [10] summarized the main methodologies for characterizing PFCA–protein binding, including separation methods, calorimetric techniques, surfactant nature-based methods, spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, surface plasmon resonance, and molecular docking. Fluorescence has proven to be a reasonable way to supply comprehensive quantitative and qualitative information about the PFCA–albumin complexation [25]. As a continuation of previous research [20,23,26], the goal of this paper was to systemically characterize the molecular mechanism of the PFCA–HSA complexation by means of fluorescence spectroscopy under simulated physiological conditions. Additionally, the effects of PFCAs with different carbon chain length on secondary structure changes of HSA were compared using FT-IR spectroscopy. Furthermore, the binding affinity of PFCAs on HSA was also interpreted by molecular docking. This study may help to understand the molecular mechanism of PFCAs’ toxicity on HSA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade, including fatty acid-free HSA (A1887, lyophilized powder, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), PFOA (98%, Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan), perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The stock solution of each PFCA was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4 ± 0.1). HSA solution was freshly prepared in PBS (pH 7.4 ± 0.1) 15 min before use. In order to prevent PFCAs from adsorbing to glass surface, polypropylene containers were used.

2.2. Fluorescence Spectrometry Measurements

A Hitachi spectrofluorometer (Model F-2700, 1.0 cm quartz cell, Hitachi, Tyoko, Japan) equipped with a xenon lamp (150 W) and a thermostat was used to record fluorescence emission spectra at different temperatures (296, 303, and 310 K) in the 290–500 nm wavelength range. The widths of excitation slits and emission slits were both set to 5.0 nm. The excitation wavelength was set to 295 nm. The PBS spectra were subtracted to correct the background fluorescence.

2.3. FT-IR Spectroscopic Measurements

A Thermo-Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was employed to measure infrared spectra. The attenuated total reflectance (ATR) method was applied to collect all spectra at a resolution of 4 cm–1 and 64 scans. The infrared spectra of HSA with and without PFCAs were recorded at 1800–1400 cm–1. The molar ratio of each PFCA to HSA was 1:1 [27]. The spectra of PBS and each PFCA were determined at the same condition and subtracted to observe the infrared spectra of the sample solution. The second derivative was used in this range to assess the number, position, and width of component bands. The best Gaussian-shaped curves were obtained through curve fitting of the Galactic peak based on these parameters. After identification, the area of each band of HSA with a representative secondary structure was determined [28].

2.4. Molecular Docking Study

The crystal structure of HSA (PDB ID: 1H9Z) was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org). PFBA (ZINC ID: 3861259), PFHxA (ZINC ID: 38141478), PFOA (ZINC ID: 6844606), and PFDA (ZINC ID: 6845007) were obtained from the Zinc (http://zinc.docking.org/) site as 3D mol2 text [29]. The Scripps Research Institute’s AutoDock Vina (http://vina.scripps.edu/) and MGLTools (http://mgltools.scripps.edu/) sites were used for docking calculations [30]. A grid of 40 Å × 40 Å × 40 Å spacing was calculated. The docking with the grid box centered at (32.033, 10.568, 4.112) in HSA indicates binding at site I for PFCAs [23]. The output of AutoDock Vina was rendered using Discovery Studio 3.5 (Discovery Studio 3.5, Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Binding Mechanism between PFCAs and HSA

Figure 1 illustrates the fluorescence spectra of HSA at 296 K in a series of PFCA concentrations. As shown in Figure 1A,B, fluorescence intensities change to a small extent by adding PFBA and PFHxA, and there is a slight shift in the emission wavelength. On the contrary, the spectra of the PFOA–HSA and PFDA–HSA systems show remarkable fluorescence quenching with increasing concentration (Figure 1C,D). At the same time, as the PFOA/PFDA concentration increases, the fluorescence intensity of HSA decreases being accompanied by a blue shift, suggesting that Trp transits from a more polar environment to a less polar environment [31].

Figure 1.

The fluorescence quenching spectra of human serum albumin (HSA) by perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) (A), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) (B), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (C) and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) (D) at 296 K, λex = 295 nm; the inset corresponds to the molecular structure of PFCAs; (E) Normalized fluorescence intensity of HSA with different PFCA concentrations. [PFCAs] (×10–6 mol/L) 1–10: 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 30, 40 and 80. [HSA] = 2 × 10–6 mol/L; Buffer: PBS, pH = 7.4.

To make the trend clearer, Figure 1E displays the normalized fluorescence F/F0 of spectrum versus PFCA concentration, where F0 and F are the fluorescence intensity of HSA before and after adding PFCAs, respectively. When comparing the general trend of four curves in Figure 1E, the slight fluctuation of the PFBA/PFHxA curve shows that PFBA and PFHxA have little effect on the fluorescence intensity of HSA. However, PFOA and PFDA obviously decrease the fluorescence intensity of HSA in the studied concentrations. In addition, based on the slopes of PFOA and PFDA curves, the combination of PFDA and HSA is stronger than PFOA. That is to say, PFDA is more likely to cause a health hazard than PFOA. Our further study of the fluorescence quenching mechanism was limited to PFOA and PFDA.

In order to further study the quenching process of PFCAs, fluorescence assays were conducted at different temperatures. The reduction of fluorescence quenching intensity is normally defined by the famous Stern–Volmer formula [31]:

| (1) |

where F0 and F are the fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of a quenching agent, respectively. KSV is the Stern–Volmer quenching constant calculated using a linear regression curve of F0/F versus [Q]; kq represents the quenching rate constant of biological molecules; τ0 is the average fluorescence lifetime without a quenching agent, and it is considered to be 10–8 s in general [31]; and [Q] is the concentration of the quenching agent. Under normal conditions, the maximum dynamic kq of various quenching agents is 2.0 × 1010 L/mol·s [31].

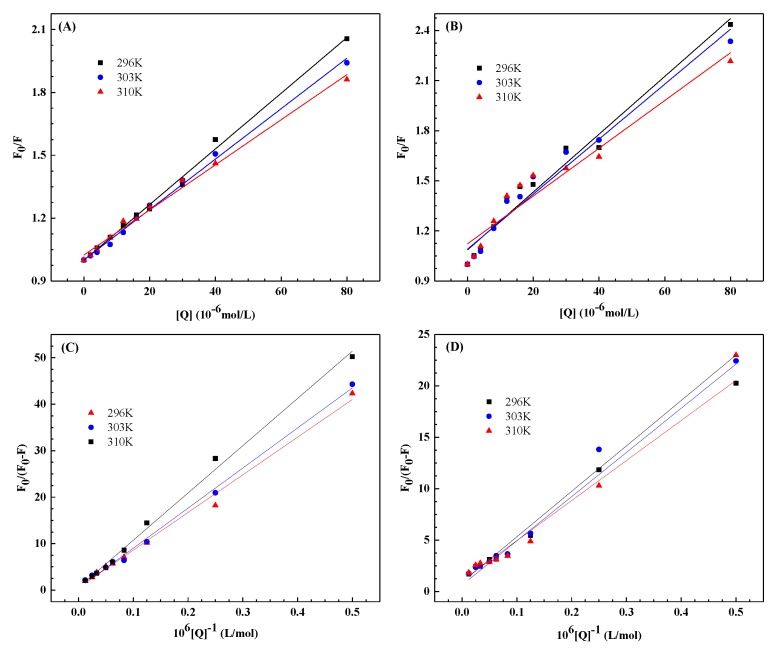

Figure 2A,B shows the Stern–Volmer diagrams of HSA quenched by PFCAs at different temperatures (296, 303, and 310 K). Table 1 lists the quenching constant calculated at the corresponding temperature. The results indicate that KSV is inversely proportional to temperature with kq higher than 2.0 × 1010 L/mol·s, meaning that the interaction between PFOA/PFDA and HSA is complicated by formation not caused by dynamic collisions.

Figure 2.

(1) Stern–Volmer plots of the PFOA–HSA (A) and PFDA–HSA (B) systems at different temperatures; (2) The modified Stern–Volmer plots of the PFOA–HSA (C) and PFDA–HSA (D) systems at different temperatures.

Table 1.

Stern–Volmer quenching constants of the PFCA–HSA system at different temperatures.

| PFCA | T (K) | KSV (×104 L/mol) | kq (×1012 L/mol·s) | R a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA | 296 | 1.328 ± 0.003 | 1.328 ± 0.003 | 0.9978 |

| 303 | 1.203 ± 0.003 | 1.203 ± 0.003 | 0.9981 | |

| 310 | 1.076 ± 0.001 | 1.076 ± 0.001 | 0.9964 | |

| PFDA | 296 | 1.731 ± 0.001 | 1.731 ± 0.001 | 0.9836 |

| 303 | 1.647 ± 0.002 | 1.647 ± 0.002 | 0.9814 | |

| 310 | 1.431 ± 0.001 | 1.431 ± 0.001 | 0.9648 |

aR is the correlation coefficient for Stern–Volmer plots.

The data were analyzed for the static quenching procedure following the modified Stern–Volmer formula [32]:

| (2) |

where fa represents the fraction of accessible fluorescence, and Ka represents the effective quenching constant of accessible fluorophores. The dependence of F0/ΔF on the reciprocal of the quencher concentration [Q] is linear, and its slope equals to (faKa)−1; fa–1 is fixed on the ordinate; and Ka is the quotient of fa−1 and (faKa)−1. Figure 2C,D shows linear graphs at different temperatures on the basis of formula (2). Table 2 displays the corresponding values of Ka. The tendency of Ka to decrease with increasing temperature is consistent with the temperature dependence of KSV as mentioned above in accordance with the static quenching mechanism. A decrease in the Ka value with temperature indicates that the binding reaction of PFOA/PFDA with HSA is exothermic [33]. The negative enthalpy change (ΔH) determined in the next section verifies this. Moreover, the Ka of PFDA–HSA is far higher than that of PFOA–HSA, suggesting that the affinity of PFDA with 10 carbons is higher than that of PFOA with 8 carbons, which is consistent with the results in Figure 1E; this discovery is supported by the fluorescence study conducted by Qin et al. [26]. As suggested by Cheng and Ng [34], the relationship between carbon chain length and binding affinity was mainly caused by the van der Waals interaction energy and entropy change during binding, both of which were closely related to carbon chain length. The results in Table 2 indicate as well that the binding constants of PFOA/PFDA to HSA are moderate, suggesting that PFOA/PFDA can be stored and transported in vivo by HSA [35].

Table 2.

Modified Stern–Volmer association constants Ka and relative thermodynamic parameters of the PFCA–HSA system at different temperatures.

| PFCA | T (K) |

Ka (×104 L/mol) |

R a | ΔH (kJ/mol) |

ΔS (J/mol·K) |

ΔG (kJ/mol) |

R b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA | 296 | 0.6153 | 0.9965 | −17.48 ± 0.33 | 13.53 ± 0.17 | −21.49 ± 0.03 | 0.9971 |

| 303 | 0.5332 | 0.9975 | −21.58 ± 0.02 | ||||

| 310 | 0.4463 | 0.9984 | −21.67 ± 0.04 | ||||

| PFDA | 296 | 2.6788 | 0.9962 | −33.37 ± 0.46 | −27.91 ± 0.29 | −25.11 ± 0.03 | 0.9988 |

| 303 | 2.0093 | 0.9929 | −24.92 ± 0.04 | ||||

| 310 | 1.4514 | 0.9926 | −24.72 ± 0.02 |

aR is the correlation coefficient for modified Stern–Volmer plots; b R is the correlation coefficient for van ’t Hoff plots.

3.2. The Characterization of Binding Force between PFOA/PFDA and HSA

Generally, interactions between drugs and proteins can contain electrostatic interaction, van der Waals interaction, hydrophobic force, and hydrogen bonding. To clarify the binding of PFOA/PFDA to HSA, the thermodynamic parameters were determined based on the van ’t Hoff formula:

| (3) |

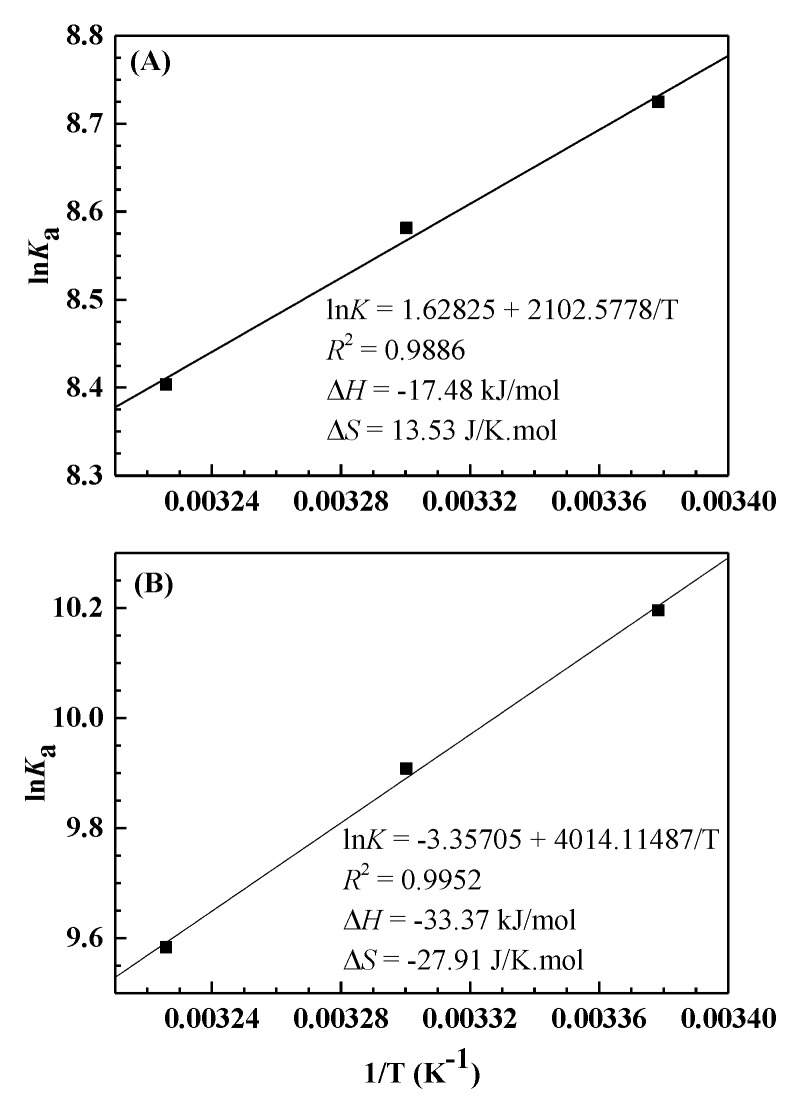

where K is similar to the effective quenching constant Ka, and R represents the gas constant. As we can see in Figure 3, there is a good linear relationship between lnK and 1/T, which means that the enthalpy change (ΔH) is constant. Then the free energy change (ΔG) is obtained according to the following formula:

| (4) |

Figure 3.

Van ’t Hoff plots of the PFOA–HSA (A) and PFDA–HSA (B) systems at different temperatures.

Table 2 presents the corresponding results. According to the thermodynamic laws for determining the binding type summed up by Ross and Subramanian [36], the positive ΔS and negative ΔH for the PFOA–HSA complex demonstrate that electrostatic interaction is the major force in the binding process, while the negative ΔS and ΔH for PFDA–HSA complex indicate that van der Waals force and hydrogen bonding are dominant in binding. The negative ΔG for both PFOA and PFDA indicates a spontaneous binding process.

3.3. The Conformational Changes of HSA Induced by PFCAs

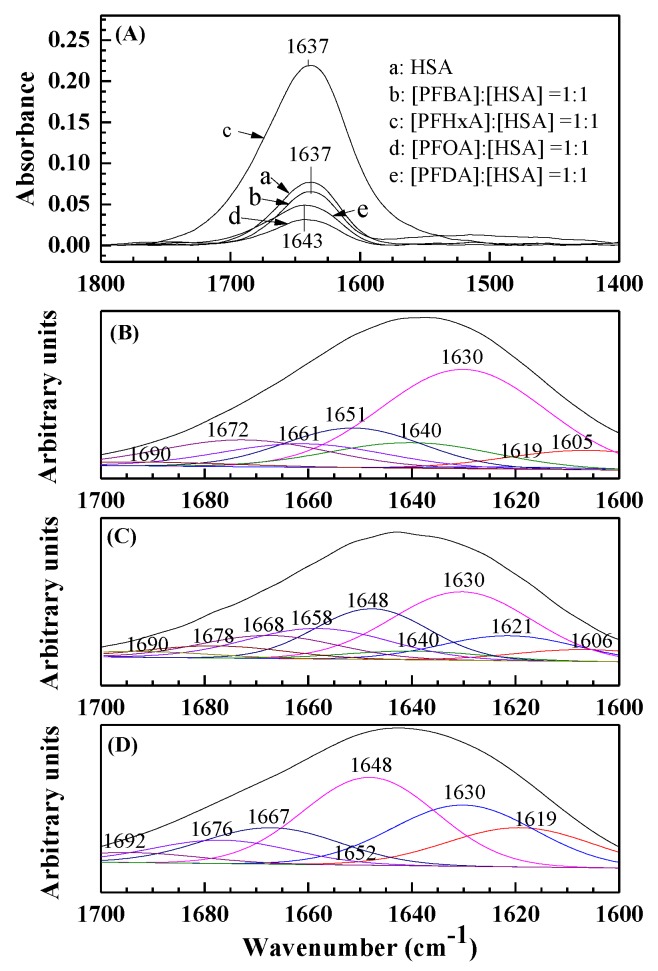

The infrared spectrum of proteins shows many amide bands, which are different vibrations of peptides. Among them, amide I bands (1700–1600 cm−1, primarily C=O stretching) and amide II bands (1600–1500 cm−1, C-N stretching coupled with N-H bending) are related to the secondary structure of a protein, whereas amide I bands are more susceptible to changes in the secondary structure of a protein than amide II bands [37]. The infrared spectra of free HSA and the difference spectra of the PFCA–HSA complex are exhibited in Figure 4A. The peak position of amide I in HSA shifted from 1637 to 1643 cm-1, pointing out that the secondary structure of HSA changed due to the binding of PFOA/PFDA to HSA [38]. Nevertheless, the peak positions of amide I in PFBA–HSA and PFHxA–HSA systems do not change, suggesting that PFBA and PFHxA have little influence on the HSA structure.

Figure 4.

(1) The FT-IR spectra (A) of free HSA (a), difference spectra [(PFBA–HSA) – PFBA solution] ([PFBA]:[HSA] = 1:1) (b), difference spectra [(PFHxA–HSA) – PFHxA solution] ([PFHxA]:[HSA] = 1:1) (c), difference spectra [(PFOA–HSA) – PFOA solution] ([PFOA]:[HSA] = 1:1) (d), and difference spectra [(PFDA–HSA) – PFDA solution] ([PFDA]:[HSA] = 1:1) (e) in a pH 7.4 buffer solution in the region of 1800–1400 cm−1; (2) The curve-fit amide I (1700–1600 cm−1) region with the secondary structure determination of the free HSA (B), PFOA–HSA complex (C), and the PFDA–HSA complex (D) in a pH 7.4 buffer solution. [HSA] = 2 × 10–6 mol/L.

According to Barth [37], spectral ranges 1660-1700 cm−1, 1650-1659 cm−1, 1640-1650 cm−1, and 1610-1640 cm−1 are allocated to β-turn, α-helix, random coil, and β-sheet, respectively. Figure 4B–D shows the curve-fitted infrared spectra of HSA and its components, assignments and compositions in order to compare the structure of HSA in the absence and presence of PFCAs more meaningfully. The percentage of each secondary structure of HSA can be obtained using the integrated area of each component band in amide I (Table 3). The sharp decrease in the β-sheet and α-helix conformations of the PFOA–HSA system and the PFDA–HSA system associated with the free HSA structure is in agreement with the assumption that the interaction of PFOA/PFDA with HSA altered the secondary structure of HSA and resulted in a partial protein destabilization [39]. However, Wu et al. [40] reported that PFOA binding decreased the β-sheet content of HSA, but increased the α-helix content by 15%. This inconsistence may be due to the different buffers used [41].

Table 3.

Secondary structure analysis (infrared spectra) for free HSA and its drug complexes at pH 7.4.

| Complex | β-Sheet | Random Coil | α-Helix | β-Turn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free HSA | 51.38 | 10.99 | 14.19 | 23.44 |

| PFOA–HSA | 46.28 | 21.96 | 9.82 | 21.94 |

| PFDA–HSA | 39.37 | 32.65 | 1.02 | 26.95 |

3.4. Molecular Modeling Results

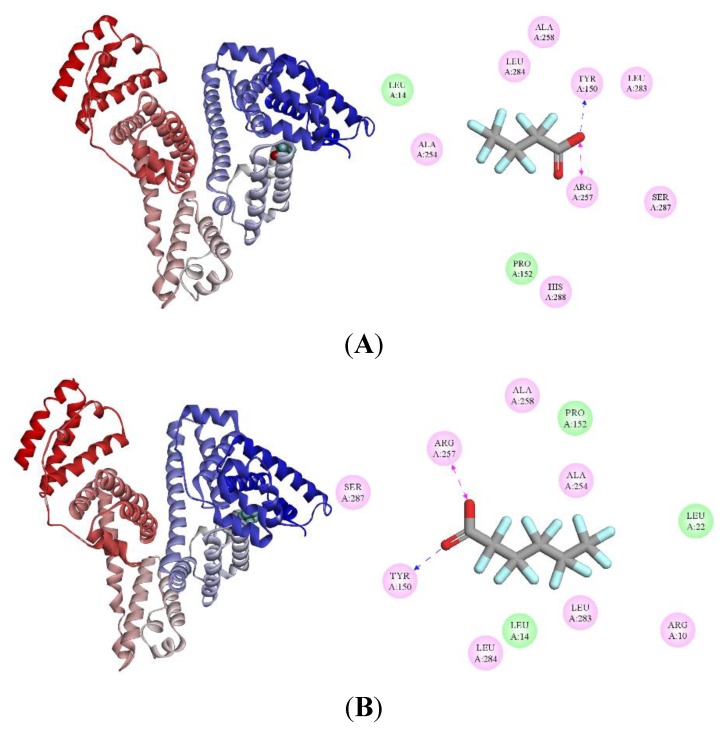

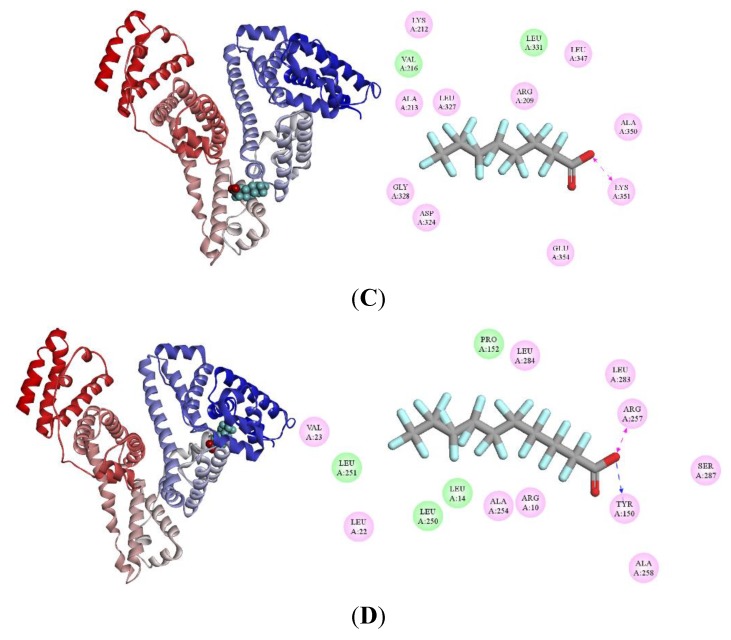

To study the binding affinities of PFCAs to HSA systemically, molecular modeling was applied by setting a simulation box to site I. The best energy-ranked result as shown in Figure 5 (left) demonstrated that PFCAs bind within the pocket of sub-domain IIA of HSA (site I), which is in accordance with the results obtained by Salvalaglio et al. [42]. The calculated lowest binding free energies (ΔG) are −24.28, −30.55, −34.74, and −40.18 kJ/mol for PFBA–HSA, PFHxA–HSA, PFOA–HSA, and PFDA–HSA, respectively, which indicates that PFCAs with a longer carbon chain have a lower ΔG suggesting a stronger binding affinity to HSA. This is in line with the fluorescence research. As described above, the van der Waals interaction energy and entropy change during binding related to carbon chain length could explain this phenomenon [34].

Figure 5.

Left: Binding site of PFCAs on HSA (PDB ID: 1H9Z). HSA is shown in cartoon. PFCAs are represented using spheres. Right: 2D ligand interaction diagram of PFCAs with HSA using Discovery Studio with the essential amino acid residues at the binding site tagged in circles. Pink circles show the amino acids that participate in electrostatic interactions, and green circles show the amino acids that participate in van der Waals interactions. Hydrogen-bond interactions with amino acid side-chains (blue dashed arrow) and charge interactions (pink dashed arrow) are indicated. (A) PFBA–HSA; (B) PFHxA–HSA; (C) PFOA–HSA; and (D) PFDA–HSA.

Figure 5 (right) shows 2D models of binding of PFCAs to HSA. The amino acid residues (AARs) around site I which take part in the interaction between PFCAs and HSA are composed of Arg 10, Leu 14, Leu 22, Val 23, Try 150, Pro 152, Arg 209, Lys 212, Ala 213, Val 216, Leu 250, Leu 251, Ala 254, Arg 257, Ala 258, Leu 283, Leu 284, Ser 287, His 288, Asp 324, Leu 327, Gly 328, Leu 331, Leu 347, Ala 350, Lys 351, and Glu 354. More than 10 AARs are lying around site I, and the essential driving forces of PFOA binding to this site are electrostatic interaction and van der Waals force, while van der Waals interaction, hydrogen bond (PFDA with Tyr 150), and electrostatic interaction are major driving forces in the combination of PFDA and HSA. The results are in line with the experimental study.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the interaction mechanism of PFCAs with different carbon chain length with HSA was studied at the molecular level by spectroscopy. PFCAs with longer carbon chains caused stronger fluorescence quenching. According to the fluorescence spectra and FT-IR data, it was found that PFBA and PFHxA had little effect on HSA. PFOA and PFDA interacted with HSA by means of a static quenching mechanism to spontaneously form a medium-intensity complex. Thermodynamic parameters indicated that the interaction force of the PFOA–HSA complex is electrostatic interaction, while van der Waals interaction and hydrogen bond play an important role in the combination of PFDA and HSA. Additionally, PFDA was found to have a stronger binding capacity than PFOA, which was supported by molecular docking. Moreover, infrared spectroscopy confirmed that the microenvironment and conformation of HSA were changed by PFOA/PFDA, and the α-helix and β-sheet conformation decreased sharply. Our results indicate that the carbon chain length of PFCAs has a great influence on their binding affinity. These data can provide certain quantitative information for future studies of molecular toxicology of PFCAs with different carbon chain length.

Author Contributions

The idea was provided by H.C.; design of the experimental method, workflow control, and paper writing were accomplished by H.C., Q.W., and Y.C.; R.Y. and F.W. conducted pretreatment of samples; B.Z. carried out instrumental analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (8202035); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41473074, 41430106, 41822706); and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (FRF-TP-19-001C1).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kwak J.I., Lee T.-Y., Seo H., Kim D., Kim D., Cui R., An Y.-J. Ecological risk assessment for perfluorooctanoic acid in soil using a species sensitivity approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020;382:121150. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sznajder-Katarzynska K., Surma M., Cieslik I. A review of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in terms of sources, applications, human exposure, dietary intake, toxicity, legal regulation, and methods of determination. J. Chem. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/2717528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng C.A., Hungerbuehler K. Bioaccumulation of perfluorinated alkyl acids: Observations and models. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:4637–4648. doi: 10.1021/es404008g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giesy J.P., Kannan K. Global distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate in wildlife. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:1339–1342. doi: 10.1021/es001834k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zareitalabad P., Siemens J., Hamer M., Amelung W. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) in surface waters, sediments, soils and wastewater–A review on concentrations and distribution coefficients. Chemosphere. 2013;91:725–732. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamid H., Li L.Y., Grace J.R. Review of the fate and transformation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in landfills. Environ. Pollut. 2018;235:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunderland E.M., Hu X.C., Dassuncao C., Tokranov A.K., Wagner C.C., Allen J.G. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J. Expo. Sci. Env. Epid. 2019;29:131–147. doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li K., Gao P., Xiang P., Zhang X., Cui X., Ma L.Q. Molecular mechanisms of PFOA-induced toxicity in animals and humans: Implications for health risks. Environ. Int. 2017;99:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corsini E., Luebke R.W., Germolec D.R., DeWitt J.C. Perfluorinated compounds: Emerging POPs with potential immunotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2014;230:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X., Fang M., Xu F., Chen D. Characterization of the binding of per- and poly-fluorinated substances to proteins: A methodological review. Trac-trend. Anal. Chem. 2019;116:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han X., Snow T.A., Kemper R.A., Jepson G.W. Binding of perfluorooctanoic acid to rat and human plasma proteins. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003;16:775–781. doi: 10.1021/tx034005w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rappazzo K.M., Coffman E., Hines E.P. Exposure to perfluorinated alkyl substances and health outcomes in children: A systematic review of the epidemiologic literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14:691. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanifer J.W., Stapleton H.M., Souma T., Wittmer A., Zhao X., Boulware L.E. Perfluorinated chemicals as emerging environmental threats to kidney health A scoping review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephro. 2018;13:1479–1492. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04670418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng Z., Song B., Xiao R., Zeng G., Gong J., Chen M., Xu P., Zhang P., Shen M., Yi H. Assessing the human health risks of perfluorooctane sulfonate by in vivo and in vitro studies. Environ. Int. 2019;126:598–610. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellenbogen E., Maurer P.H. Heat denaturation of serum albumin in presence of perfluorooctanoic acid. Science. 1956;124:266–267. doi: 10.1126/science.124.3215.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guy W.S., Taves D.R., Brey W.S. Biochemistry Involving Carbon-Fluorine Bonds. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC, USA: 1976. Organic Fluorocompounds in Human Plasma: Prevalence and Characterization; pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y., Zhang H., Kang Y., Fei Z., Cao J. The interaction of perfluorooctane sulfonate with hemoglobin: Influence on protein stability. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016;254:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu H., Zhang H., Gao J., Li Z., Bao S., Chen X., Wang Y., Ge R., Ye L. Effects of perfluorooctanoic acid on stem Leydig cell functions in the rat. Environ. Pollut. 2019;250:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu M., Cui Z., Zhao L., Hu S., Zong W., Liu R. Characterizing the binding interactions of PFOA and PFOS with catalase at the molecular level. Chemosphere. 2018;203:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bischel H.N., MacManus-Spencer L.A., Luthy R.G. Noncovalent interactions of long-chain perfluoroalkyl acids with serum albumin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:5263–5269. doi: 10.1021/es101334s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong W., Zhang L., Cui Y., Chen M., Zhu L. Probing mechanisms for bioaccumulation of perfluoroalkyl acids in carp (Cyprinus carpio): Impacts of protein binding affinities and elimination pathways. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019;647:992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen M., Qiang L., Pan X., Fang S., Han Y., Zhu L. In vivo and in vitro isomer-specific biotransformation of perfluorooctane sulfonamide in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:13817–13824. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y.-M., Guo L.-H. Fluorescence study on site-specific binding of perfluoroalkyl acids to human serum albumin. Arch. Toxicol. 2009;83:255–261. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones P.D., Hu W.Y., De Coen W., Newsted J.L., Giesy J.P. Binding of perfluorinated fatty acids to serum proteins. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003;22:2639–2649. doi: 10.1897/02-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacManus-Spencer L.A., Tse M.L., Hebert P.C., Bischel H.N., Luthy R.G. Binding of perfluorocarboxylates to serum albumin: A comparison of analytical methods. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:974–981. doi: 10.1021/ac902238u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin P., Liu R., Pan X., Fang X., Mou Y. Impact of carbon chain length on binding of perfluoroalkyl acids to bovine serum albumin determined by spectroscopic methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:5561–5567. doi: 10.1021/jf100412q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H., He P., Rao H., Wang F., Liu H., Yao J. Systematic investigation of the toxic mechanism of PFOA and PFOS on bovine serum albumin by spectroscopic and molecular modeling. Chemosphere. 2015;129:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdi K., Nafisi S., Manouchehri F., Bonsaii M., Khalaj A. Interaction of 5-Fluorouracil and its derivatives with bovine serum albumin. J. Phys. Chem. B Biol. 2012;107:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irwin J.J., Sterling T., Mysinger M.M., Bolstad E.S., Coleman R.G. ZINC: A free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012;52:1757–1768. doi: 10.1021/ci3001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trott O., Olson A. Software news and update AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakowicz J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3rd ed. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehrer S. Solute perturbation of protein fluorescence. Quenching of the tryptophyl fluorescence of model compounds and of lysozyme by iodide ion. Biochem. US. 1971;10:3254–3263. doi: 10.1021/bi00793a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibrahim N., Ibrahim H., Kim S., Nallet J.-P., Nepveu F. Interactions between antimalarial indolone-N-oxide derivatives and human serum albumin. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:3341–3351. doi: 10.1021/bm100814n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng W., Ng C.A. Predicting relative protein affinity of novel per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) by an efficient molecular dynamics approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:7972–7980. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b01268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dufour C., Dangles O. Flavonoid–serum albumin complexation: determination of binding constants and binding sites by fluorescence spectroscopy. BBA-Gen. Subjects. 2005;1721:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross P.D., Subramanian S. Thermodynamics of protein association reactions: forces contributing to stability. Biochem.-US. 1981;20:3096–3102. doi: 10.1021/bi00514a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barth A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. BBA-Bioenergetics. 2007;1767:1073–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed-Ouameur A., Diamantoglou S., Sedaghat-Herati M.R., Nafisi S., Carpentier R., Tajmir-Riahi H.A. The effects of drug complexation on the stability and conformation of human serum albumin. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2006;45:203–213. doi: 10.1385/CBB:45:2:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chanphai P., Tajmir-Riahi H.A. Conjugation of citric acid and gallic acid with serum albumins: Acid binding sites and protein conformation. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;299:112178. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu L.-L., Gao H.-W., Gao N.-Y., Chen F.-F., Chen L. Interaction of perfluorooctanoic acid with human serum albumin. BMC Struct. Biol. 2009;9:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zbacnik T.J., Holcomb R.E., Katayama D.S., Murphy B.M., Payne R.W., Coccaro R.C., Evans G.J., Matsuura J.E., Henry C.S., Manning M.C. Role of buffers in protein formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;106:713–733. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salvalaglio M., Muscionico I., Cavallotti C. Determination of Energies and Sites of Binding of PFOA and PFOS to Human Serum Albumin. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:14860–14874. doi: 10.1021/jp106584b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]