Key Points

Question

How do recent ophthalmology residency applicants view the application process, and what changes would they suggest?

Findings

The results of this nonvalidated cross-sectional survey suggest that most applicants had difficulty selecting programs to apply to and desired both centralized scheduling of interviews and longer lead times between interview invitations and interview dates.

Meaning

When determining the number and location of residency applications to complete, applicants may benefit from additional information from programs; the application process poses considerable financial and administrative burdens, and applicants believe that interview invitations and scheduling are areas of possible improvement.

This cross-sectional, nonvalidated survey evaluates the experiences and preferences of ophthalmology residency applicants who applied to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in the 2018-2019 application cycle.

Abstract

Importance

The ophthalmology residency application process is critical for applicants and residency programs, and knowledge about the preferences of applicants would assist both groups in improving the process.

Objective

To evaluate the experiences and preferences of ophthalmology residency applicants.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional, nonvalidated survey was conducted online. All applicants to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute ophthalmology residency program during the 2018-2019 application cycle were invited to complete the survey. Data collection occurred from April 1, 2019, to April 30, 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Applicant demographics, application submissions, interview experiences, financial considerations, match results, and suggestions for improvement of the application process.

Results

Responses were received from 185 applicants (36.4%), including 77 women (41.6%). A successful match into an ophthalmology residency was achieved by 172 respondents (93.0%). There was a mean (SD) US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 score of 245.8 (13.3) points. Respondents applied to a mean (SD) of 76.4 (23.5) ophthalmology residency programs, received 14.0 (9.0) invitations to interview, and attended 10.3 (4.4) interviews. Choices regarding applications and interviews were based mostly on program reputation, location, and advisor recommendation. A usual lead time of at least 3 weeks between the invitation and interview was reported by 126 respondents (69.2%), which was reduced to 14 respondents (15.1%) when a wait-list was involved. The ophthalmology residency application process cost a mean (SD) of $5704 ($2831) per applicant. Respondents reported that they were most able to reduce costs through housing choices (hotel stays or similar arrangements) and least able to reduce costs by limiting the number of programs to which they applied or at which they interviewed.

Conclusions and Relevance

The ophthalmology residency application process is complex and poses substantial challenges to applicants and residency programs. These findings suggest that many current applicants have difficulty selecting programs to apply to, and most respondents desired changes to the current system of interview invitations and scheduling.

Introduction

Hundreds of individuals apply for ophthalmology residency positions each year using the Centralized Application Services (CAS), administered by San Francisco Residency and Fellowship Matching Services (SF Match). Although the match rate remains relatively stable at approximately 75%, the mean number of applications submitted has risen from 48 in 2008 to 75 in 2019.1,2 In 2010, highly qualified applicants were advised to apply to between 10 and 20 residency programs,3 but more recent studies suggested a target of 45 applications for these applicants and more than 80 for applicants with less competitive qualification.2 The application process represents a considerable financial burden for applicants; in 2018-2019, the CAS application alone cost $685 to apply to 45 programs, which increased to $1910 for 80 programs. These high costs are not unique to ophthalmology. In emergency medicine, the cost of securing a residency position was estimated at $8312 in 2016.4

These trends also come with increasing administrative burden for residency programs tasked with reviewing rising numbers of applications. As a result, many programs have increasingly emphasized quantifiable cognitive measures, such as clinical grades and the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) board scores.3 The USMLE Step 1 scores and Alpha Omega Alpha Honors Medical Society membership are factors with statistically significant associations with matching into an ophthalmology residency.5 Although USMLE Step 1 scores have been correlated with in-training examination scores and board-certification pass rates, they are not associated with performance on clinical tasks.6 Changes have been suggested in the field of ophthalmology and other specialties, including imposing limits on the number of applications submitted by an applicant, requiring supplemental essays to better gauge interest, and increasing the transparency of residency program selection criteria.6,7,8

Previous studies examined the selection criteria for members of residency selection committees.3 The preferences of applicants themselves have been described, with resident-faculty relationships, clinical or surgical volume, and diversity of training being most important for ordering rank lists.9 The competitiveness of the ophthalmology residency match continues to rise, and the use of the internet as a source of information is growing exponentially.10 The present study is designed to evaluate the experiences of recent ophthalmology residency applicants and explore possible improvements to the current system.

Methods

A nonvalidated online survey was created via Google Forms (Google LLC) for 2018-2019 ophthalmology residency applicants. Questions assessed respondent demographics, applications submitted, interview experiences, financial considerations, match results, and suggestions for improvement to the application process (eAppendix in the Supplement).

All residency applicants (N = 508) to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (BPEI) during the 2018-2019 application cycle were invited to complete the survey by email. The survey remained open for completion between April 1, 2019, and April 30, 2019. Information regarding residency program interview dates was obtained from the SF Match website (https://www.sfmatch.org). Write-in responses were grouped qualitatively. Participation was voluntary, and no compensation was provided. To limit coercion, the survey was opened after completion of the residency match process, and responses were collected anonymously. The University of Miami institutional review board/ethics committee ruled that approval was not required, because this survey collected information without identifiable factors and completion of the survey conferred minimal risk. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 14 software (SAS Institute Inc), with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Respondent Demographics

Survey responses were obtained from 185 applicants (36.4% completion). The mean (SD) age of respondents was 26.8 (2.7) years, with 77 women (41.6%) and a mean (SD) USMLE Step 1 score of 245.8 (13.3) points. Respondents reported 3.2 (4.7) peer-reviewed works accepted for publication or already in print at the time of application submission, and 2.3 (1.9) works in progress. Most respondents attended medical schools in the South or Southeast (n = 59 [31.9%]), Northeast (n = 49 [26.5%]), or Midwest (n = 47 [25.4%]) regions of the United States. Medical schools offered a class ranking system for 139 respondents (75.1%), and 88 of these (63.3%) were in the first (or top) quartile of their class. Of the 169 respondents (91.4%) eligible for membership in Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society, 27 (16.0%) were inducted as a junior student, while 35 (20.7%) were inducted as a senior student at the time of application submission. At least 1 additional year beyond 4 years for medical school was reported by 46 respondents (24.9%), with 29 of these (63.0%) using this year for a research year or fellowship and 12 (26.1%) obtaining an additional degree.

SF Match Applications

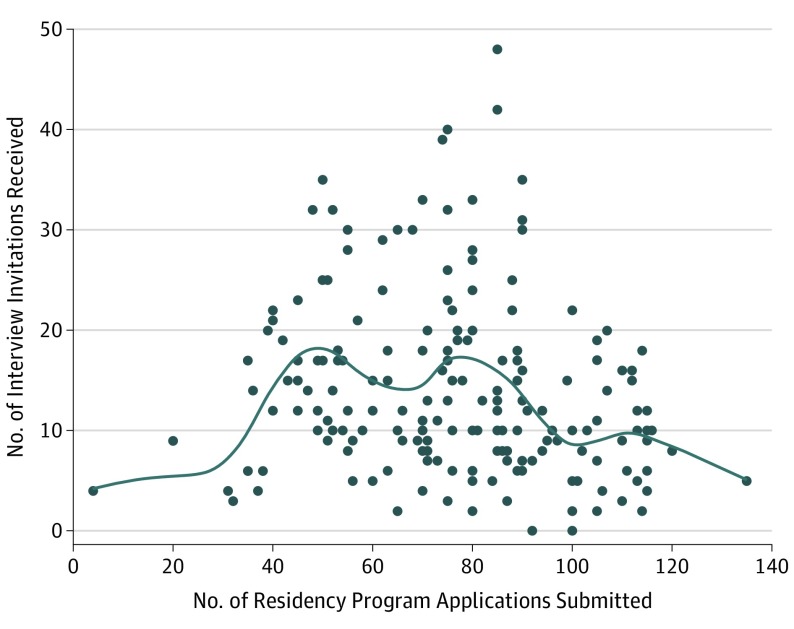

Respondents applied to a mean (SD) of 76.4 (23.5) ophthalmology residency programs, received 14.0 (9.0) invitations to interview (Figure 1), and attended 10.3 (4.4) interviews. The respondents’ choice of the number of applications to send was influenced most strongly by a “fear of not matching” and advice from peers. Write-in responses (n = 43) mentioned a desire to match at the same location as a significant other (n = 10 [23.3%]), strength of USMLE Step 1 scores (n = 6 [14.0%]), attendance at a medical school with a less prestigious reputation (n = 5 [11.6%]), and status as an international medical graduate (IMG; n = 4 [9.3%]). When asked to judge the number of applications submitted, the most common response (n = 80 [43.2%]) was that respondents applied to too many programs but would apply to the same number if repeating the process. The most important factors in deciding to apply to an ophthalmology residency program were program ranking and reputation, program location, and advisor recommendation, and the least important factor was the presence of specific faculty at a program (Table). Common write-in responses (n = 26) pertained to research opportunities (n = 4 [16.0%]) and information gained through away rotations (n = 3 [12.0%]).

Figure 1. Association Between the Number of Residency Interviews Received and Number of Applications Submitted.

A survey was sent to all 2018-2019 ophthalmology residency applicants to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. Respondents were asked to quantify the number of residency programs to which they applied and the number of interview invitations they received.

Table. Influences on Application to and Ranking of Individual Ophthalmology Residency Programs.

| Aspect of Program | Responsea | |

|---|---|---|

| Mode | Median (Range) | |

| Influence on choice to apply to a program | ||

| Program ranking and reputation | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Location of program | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Advisor recommendation | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Family or friends in area | 5 | 3 (1-5) |

| Surgical numbers | 4 | 4 (1-5) |

| Prior fellowship-match results | 4 | 4 (1-5) |

| Program size | 4 | 3 (1-5) |

| Resident recommendation | 3 | 4 (1-5) |

| Specific program resourcesb | 3 | 3 (1-5) |

| Spouse or significant other | 1 | 3 (1-5) |

| Specific faculty at program | 1 | 2 (1-5) |

| Influence on Position of Program in Rank List | ||

| Positive influence | ||

| Program ranking and reputation | 5 | 5 (1-5) |

| Location of program | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Advisor recommendation | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Spouse or significant other | 5 | 3 (1-5) |

| Surgical numbers | 4 | 4 (1-5) |

| Prior fellowship match results | 4 | 4 (1-5) |

| Program size | 4 | 4 (1-5) |

| Specific program resourcesb | 3 | 3 (1-5) |

| Resident recommendation | 3 | 3 (1-5) |

| Specific faculty at program | 3 | 3 (1-5) |

| Family or friends in area | 1 | 3 (1-5) |

| Negative influence | ||

| Poor connection with faculty | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Poor connection with residents | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Poor interview experience | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

| Undesirable geography | 5 | 4 (1-5) |

Responses of importance were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Examples include a Veterans Affairs hospital, a children’s hospital, and international opportunities.

Interview Scheduling and Experience

Among all programs, there was a mean (SD) of 54.8 (16.5) (range, 12-92) days between the date of CAS applications being made available to programs and that of a program’s initial interview invite distribution, and 36.6 (14.7) (range, 11-87) days between the date of a program’s initial interview invitation distribution and that of their first offered interview date. When respondents received an interview invitation without the involvement of a wait-list, they most commonly reported receiving the invitation between 3 and 4 weeks prior to the interview date (n = 87 [47.8%]). When instead receiving their invitation from a wait-list (n = 92 [49.7%]), the most common lead time was 1 to 2 weeks prior to the interview date (n = 43 [46.2%]), with 20 (21.5%) invitations arriving less than 1 week prior (Figure 2). When asked how often the respondent received their desired interview date on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always), the mode (median; range) response was 4 (4; 1-5). The most common factor limiting one’s ability to obtain his or her desired interview date was a scheduling conflict with another residency program or the date being filled at the time of interview invitation acceptance. Write-in responses (n = 26) most commonly pertained to difficulty responding quickly to interview invitations (n = 10 [38.5%]). The most important factor in declining an interview invitation was the presence of a scheduling conflict, and less important factors included low interest in the residency program, cost of travel, and interview surplus or fatigue. Write-in responses (n = 14) focused on difficulties with cross-country travel logistics (n = 5 [35.7%]) and late receipt of interview invitations (n = 2 [14.3%]).

Figure 2. Association Between Interview Invitation Lead Time and Applicant Wait-List Status.

A survey was sent to all 2018-2019 ophthalmology residency applicants to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. Respondents were asked to quantify the mean amount of time between interview invitation receipt and interview day for invitations that were received without the use of a wait-list (black) and those that did involve the use of a wait-list (gray).

In creating a positive interview-day experience, the most important factor for respondents was their connection to faculty during the interview and residents throughout the day, and food was given the lowest importance. Write-in responses (n = 33) focused on the presence of a friendly or welcoming environment (n = 6 [18.2%]), then succinctness and preinterview communication (n = 4 [12.1%] for each).

Creation of a Rank List

Respondents ranked a mean (SD) of 10.1 (4.6) programs on their rank lists (Figure 3). The most important positive influence was a program’s ranking and reputation, while negative influences included poor connections with faculty or residents, poor interview experiences, and undesirable geography (Table). Write-in responses (n = 37) focused on a gut feeling about the culture of a program (n = 11 [29.7%]), experiences during the interview day (n = 6 [16.2%]), and research opportunities (n = 4 [10.8%]). There were 2 respondents who reported accepting a residency position outside of the regular match process, and they were excluded from this portion of the analysis.

Figure 3. Association Between Applicant Rank-List Size and Various Application Demographics.

A survey was sent to all 2018-2019 ophthalmology residency applicants to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. Respondents were asked to quantify the number of residency programs they included on their rank list, as well as the number of applications submitted (A), number of interview invitations received (B), and number of interviews attended (C). The association between these is depicted here. Two respondents accepted a residency position outside of the regular match process and therefore are not included in here because they did not submit a rank list.

Financial Considerations

Respondents estimated spending a mean (SD) of $5704 ($2831) throughout the ophthalmology residency application process, before considering costs incurred for applications and interviews for postgraduate year 1 positions. For each interview, respondents most commonly estimated spending $201 to $301 on transportation expenses, $101 to $201 on housing expenses, and less than $50 on food, dry cleaning, and other miscellaneous expenses. Additional funding was obtained by 125 respondents (67.6%) to offset costs of applying and interviewing, with most sourcing these funds through family support (n = 69 [55.2%]), additional loans (n = 33 [26.4%]), or credit card debt (n = 17 [13.6%]). Respondents believed that application costs were most affected by transportation costs and interviews that were separated geographically but close temporally. When attempting to reduce costs, respondents were most able to change their choices in housing and least able to change the number of programs at which they interviewed or to which they applied.

Match Results

A successful ophthalmology residency match was achieved by 172 respondents (93.0%), at a mean (SD) rank of 2.70 (1.96) on their respective rank lists. Acceptance of a residency position outside of the regular match occurred for 2 respondents (1.1%). Most applicants (n = 86 [51.2%]) matched in the same geographic area as their medical school. A total of 165 applicants were unsuccessful in matching to an ophthalmology residency from 2018 to 2019,1 of which our survey captured 13 responses (7.8%). For those who did not match (n = 13 [7.0%]), the most common reasons reported were deficiencies in USMLE Step 1 scores (n = 7 [53.8%]), research experience (n = 5 [38.5%]), and/or clinical grades (n = 4 [30.8%]); the most common write-in response (n = 7) was IMG status (n = 3 [42.9%]). Of those who did not match, 8 (61.5%) planned to reapply to ophthalmology residencies after spending the 2019-2020 academic year in a postgraduate year 1 internship (n = 4 [50.0%]) or research fellowship (n = 2 [25.0%]).

Suggestions for Improvement

When asked about possible changes to the SF Match system, respondents most commonly desired centralized scheduling of interviews through the SF Match website (n = 136 [73.5%]) and a requirement for at least a 1-month lead time between interview invitation and interview date (n = 119 [64.4%]). Write-in suggestions (n = 42) focused on improved coordination between different ophthalmology residency programs (n = 13 [31.0%]; eg, grouping together interview dates with similar geographies, capping the number of programs holding interviews on the same day, or releasing interview invitations at standardized times), and increased transparency regarding applicant characteristics that programs are looking for (n = 4 [9.5%]).

Discussion

It is unsurprising that many ophthalmology applicants had high USMLE board scores, first-quartile class rankings, Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society membership, and prolific research output. The mean number of applications submitted by each applicant continues to rise despite diminishing returns,2 with many applicants accepting all invitations and ranking all programs at which they interviewed (Figure 3B and C). The probability of matching does rise when adding additional programs to one’s rank list but plateaus at approximately 11 ranked programs.11 As a result, residency programs are tasked with reviewing increasing numbers of applications, and applicants often require additional funding sources.

In selecting application submissions, applicants often practice self-selection. We found a bimodal distribution in interview invitations received, associated with approximately 50 and 80 applications submitted (Figure 1). Similarly, data from SF Match reveal the highest numbers of interview invitations at approximately 50 applications submitted,1 which mirrors recommendations given by Siatkowski and colleagues.2 However, the match process is multifactorial, and it is difficult to estimate applicant competitiveness. Other specialties benefit from detailed reports by the National Resident Matching Program and their periodic Charting Outcomes in the Match publication (http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf), which provides aggregate data on estimated probabilities of matching based on USMLE scores as well as information on research or volunteer endeavors, Alpha Omega Alpha membership, medical school ranking, and advanced degrees, separated by matched or unmatched status. Furthermore, Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR; at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas) works to increase transparency of the National Resident Matching Program residency match by presenting aggregate information from recently matched fourth-year medical students regarding their application components, interview statistics, and ultimate match result. Programs themselves may also provide additional information, such as the mean USMLE Step 1 scores of their residents. These options provide applicants with a sense of their competitiveness at individual programs and improve their ability for self-selection in application-associated decisions. This level of detail is not yet available for the ophthalmology match.2,11

Although most invitations arrived at least 3 weeks ahead of the interview date, invitations involving applicants coming off a wait-list arrived with considerably shorter lead times (Figure 3). For the typical interview, respondents spent the most on transportation-associated expenses, and changes to applicant travel itineraries can be extremely costly. Residency programs have an incentive for early invitations and interviews to speak with applicants while they are fresh, avoid scheduling conflicts with their desired interviewees, and allow ample time for discussions on candidates. Although not addressed in this survey, such delays are likely influenced in part by the medical school dean’s letter, which summarizes an applicant’s performance throughout medical school and is generally unavailable at the time of CAS distribution. For wait-lists in which vacancies open suddenly, a short notice may be inevitable. As such, suggestions to reduce the number of interviews dropped by applicants include limiting the total number of applications able to be submitted by an individual applicant and a centralized scheduling service that either limits the number of interviews an applicant may hold at one time or limits the applicant to holding only 1 interview concurrently for any particular calendar day.

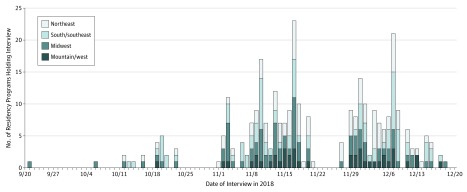

Many applicants struggled with scheduling conflicts with other residency programs, where interview dates overlapped or the desired date was filled at the time of invitation response. Certain dates were especially popular for residency programs, with 23 of 116 programs (19.8%) holding interviews on a single day during the 2018-2019 interview cycle (Figure 4). Clustering interviews based on geographic location could reduce required travel but requires tremendous coordination between more than 100 busy programs and could increase frustration for candidates who have many interviews in a similar location but cannot complete them within the region’s time frame. In special circumstances, when a person is unable to attend the interview day, video interviews could be offered as an alternative and accompanied by an interactive or even virtual-reality tour at the expense of valuable in-person interactions.

Figure 4. Distribution of Residency Program Interviews.

Information was obtained from the SF Match website (https://www.sfmatch.org/) regarding interview dates held by each of the participating ophthalmology residency programs and was plotted to demonstrate the temporal and geographic clustering of residency interviews. Residency interviews were held between September 21 and December 18, 2019. The maximum number of concurrent interviews occurred on November 16, 2019, with 23 different ophthalmology residency programs interviewing applicants.

Write-in responses criticized the requirement to respond to invitations immediately amidst clinical duties as a medical professional and intermittent availability while traveling and interviewing. Many ophthalmology residency programs currently use third-party companies to assist with the organization of interview scheduling. Use of a centralized scheduling system, most feasibly through SF Match, could improve on these issues by allowing for standardized timing of interview invitations with advanced notification. This would allow applicants to plan their ideal acceptances and make necessary changes to currently held interviews prior to invitations becoming available for acceptance and scheduling. For applicants, this would reduce the uncertainty involved with responding to invitations. For residency programs, this would allow for standardization of invitation distribution and relieve some of the burden involved with organization of this process. However, the increased administrative burden, previously undertaken by each program individually, may lead to increased CAS application costs.

Respondents reported a match rate much greater than the national mean.1 Most respondents matched in the same geographic location as their medical school, a trend that has been previously described.12 The most common write-in response explaining failure to match was IMG status. Despite making up approximately 25% of the overall physician workforce in the US13 and 9.4% of all ophthalmology residency applicants in 2018-2019, IMGs accounted for only 3.5% of matched positions, with an overall match rate of 28%.1 To maximize their chances of training in the US, recommendations have been given for IMGs to achieve even higher USMLE board scores, apply to a larger number of residency programs, and develop substantial clinical and research relationships with US ophthalmologists.2,13 This suggests the importance of careful selection of locations for clinical research or duties, which again would benefit from improved ability for self-reflection.

Limitations

It is important to consider the generalizability of the results of this nonvalidated survey. Although the applicants who were invited to participate in the survey represented most participants (78.3%) in the 2019 Ophthalmology Match Program, they only included those who applied to the BPEI, a top reputation-ranked residency program. Results therefore may disproportionally represent higher-achieving applicants who chose to apply to the program. Since the survey was completed anonymously, we are restricted to certain applicant demographics for comparison. For the 2018-2019 application cycle, SF Match reports suggest a mean USMLE Step 1 score of approximately 241 for all matched and unmatched applicants combined.1 The mean (SD) USMLE Step 1 score of all 2018-2019 applicants to the BPEI was 243.8 (13.6) points, which is comparable with that of all applicants (P = .99 by 1-sample t test) and suggests that applicants to BPEI may be representative of the overall population. Not all invited applicants completed the survey, and so our response rate of 36.4% is a possible source of participation bias. However, respondents were representative of the total surveyed population with respect to USMLE Step 1 scores (2-sample t test) and locations of medical schools (Pearson likelihood ratio). Finally, survey respondents reported a match rate well above the mean rate published by SF Match, suggesting that respondents could differ from the overall population. Since the mean (SD) USMLE Step 1 scores reported by SF Match did not differ from the scores for matched respondents (246.5 [12.8]; P = .99; 1-sample t test) or unmatched respondents (236.4 [17.5]; P = .71), the competitiveness of survey respondents may be representative of all applicants. However, our survey only captured responses from 8 of 165 unmatched applicants (4.8%), and so these results are likely less representative of those who do not successfully match. Finally, the survey asked respondents to estimate financial expenses and interview lead time, which are potential sources of recall bias.

Conclusions

The ophthalmology residency match is a complex process that requires tremendous efforts toward finding mutual fits between applicants and programs. Recently, increased reliance on electronic interview scheduling and more information available on residency program websites have improved the applicant experience. However, these findings suggest that the residency application process remains a substantial burden to applicants, residency programs, and administrators. With continued changes to USMLE board examinations and a recent push toward integrating the ophthalmology residency with the postgraduate year 1 year, further dialogue is necessary to optimize the process.

eAppendix. Ophthalmology Match 2018-2019 Cycle Post-Match Applicant Survey

References

- 1.Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology Ophthalmology residency match summary report 2019. https://www.sfmatch.org/PDFFilesDisplay/Ophthalmology_Residency_Stats_2019.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed February 5, 2020.

- 2.Siatkowski RM, Mian SI, Culican SM, et al. ; Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology . Probability of success in the ophthalmology residency match: three-year outcomes analysis of San Francisco Matching Program data. J Acad Ophthalmol. 2018;10(1):e150-e157. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nallasamy S, Uhler T, Nallasamy N, Tapino PJ, Volpe NJ. Ophthalmology resident selection: current trends in selection criteria and improving the process. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(5):1041-1047. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackshaw AM, Watson SC, Bush JS. The cost and burden of the residency match in emergency medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(1):169-173. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.10.31277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loh AR, Joseph D, Keenan JD, Lietman TM, Naseri A. Predictors of matching in an ophthalmology residency program. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(4):865-870. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katsufrakis PJ, Uhler TA, Jones LD. The residency application process: pursuing improved outcomes through better understanding of the issues. Acad Med. 2016;91(11):1483-1487. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CW, Erhardt BF. Rising residency applications: how high will it go? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(5):702-705. doi: 10.1177/0194599815597216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta D, Kumar S. ERAS: can it be revamped? one point of view. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):467. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00015.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yousuf SJ, Kwagyan J, Jones LS. Applicants’ choice of an ophthalmology residency program. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(2):423-427. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoeger SM, Freeman H, Bitter B, Helmer SD, Reyes J, Vincent KB. Evaluation of general surgery residency program websites. Am J Surg. 2019;217(4):794-799. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.12.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yousuf SJ, Jones LS. Ophthalmology residency match outcomes for 2011. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(3):642-646. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1358579. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1358579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driver TH, Loh AR, Joseph D, Keenan JD, Naseri A. Predictors of matching in ophthalmology residency for international medical graduates. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):974-975.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Ophthalmology Match 2018-2019 Cycle Post-Match Applicant Survey