Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to perform and report a systematic review of published research on patient safety attitudes of health staff employed in hospital emergency departments (EDs).

Design/methodology/approach

An electronic search was conducted of PsychINFO, ProQuest, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed and CINAHL databases. The review included all studies that focussed on the safety attitudes of professional hospital staff employed in EDs.

Findings

Overall, the review revealed that the safety attitudes of ED health staff are generally low, especially on teamwork and management support and among nurses when compared to doctors. Conversely, two intervention studies showed the effectiveness of team building interventions on improving the safety attitudes of health staff employed in EDs.

Research limitations/implications

Six studies met the inclusion criteria, however, most of the studies demonstrated low to moderate methodological quality.

Originality/value

Teamwork, communication and management support are central to positive safety attitudes. Teamwork training can improve safety attitudes. Given that EDs are the “front-line” of hospital care and patients within EDs are especially vulnerable to medical errors, future research should focus on the safety attitudes of medical staff employed in EDs and its relationship to medical errors.

Keywords: Patient safety, Quality improvement, Teamwork, Safety climate, Safety attitude

Introduction

The effective delivery of hospital services and patient care is significantly tied to the safety attitudes and practices of hospital staff and management (Reason, 1993). Indeed, issues related to patient health and safety in hospitals throughout the world have resulted in-patient deaths, prolonged hospitalisations, irreversible disabilities and significant financial costs (Reason, 1993; Abdou and Saber, 2011; Alayed et al., 2014; Allen, 2009; Almutairi et al., 2013; Chaboyer et al., 2013; Duthie, 2006; Profit et al., 2012; Rodriguez-Paz and Dorman, 2008). To address these issues, recent research has focussed on the importance of a hospital safety climate to optimise the effective delivery of patient care. According to The Health Foundation (2011), safety climate focuses on staff perceptions about how safety is managed within their organisation in terms of measurable components. These measurable components include management behaviours, safety systems and employee’s safety attitudes (The Health Foundation, 2011).

Measuring safety attitudes among hospital staff has been widely researched and reported in the literature to provide a lens through which to view and improve the patient safety culture in hospitals (Blegen et al., 2005; Bondevik et al., 2014; Carvalho et al., 2015; Sexton et al., 2011; Steyrer et al., 2013; Yaprak and Intepeler, 2015). Indeed, Sexton et al. (2006) maintain that attitudes gauged through surveys of the perceptions of frontline workers within hospitals provide a snapshot of hospital safety culture (Sexton et al., 2006). Safety attitudes have been investigated in a range of countries and different hospital departments. For example, Allen (Allen, 2009) employed the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ; Sexton et al., 2006) to establish the safety culture in the maternity services of two Australian hospitals. He found the optimal safety culture was lacking across six safety domains, especially in the domain of management support and working conditions. Moreover, the safety culture was influenced by poor communication when the need for care escalated, lack of supervision of junior staff, issues with staffing, skill mix and low morale.

Along with the significant research focus on safety attitudes within hospital settings, there have been several systematic reviews of findings relating to patient safety attitudes. These have included systematic reviews relating to the safety attitudes of hospital staff in Arab countries (Elmontsri et al., 2017) and hospital in-patient settings (Weaver, 2013). Other systematic reviews have investigated research connecting patient safety attitudes and patient outcomes to determine nurse-sensitive patient outcomes in hospital settings (DiCuccio, 2015), studies on patient safety issues and practices in emergency medical services (Bigham et al., 2012) and studies on patient safety culture strategies to improve the hospital patient safety climate (Morello et al., 2013). Yet, there has been no systematic review of the state of research literature on safety attitudes of health staff employed in hospital emergency departments (Eds). This would appear to be an important issue to clarify, given that EDs are the “front-line” of hospital care (Rigobello et al., 2017) and patients within EDs are especially vulnerable to medical errors (Shaw et al., 2009). The primary objective of this study was to perform a systematic review of published research on the patient safety attitudes of health care professional staff employed in hospital EDs.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

To meet the objective of this study, an electronic literature search was conducted in July 2018 using six different science, health and medicine focussed research databases: PsychINFO, ProQuest, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). No limitations were set on the date of publications; however, search filters were used to limit search hits to publications published in English. The database search strategy entailed initial uses of a broad search term to capture a wide body of studies relevant to the review. Thus, the search process included combinations of the terms “Hospital Emergency department staff”, “Patient Safety attitudes”, “Safety Culture”, “Safety Climate”, “Medical Errors” and “Adverse Events” as well as combinations of MeSh terms “Safety Management”, “Patient Care Team” and “Attitude of Health Personnel” (Appendix 1).

Inclusion criteria and study selection

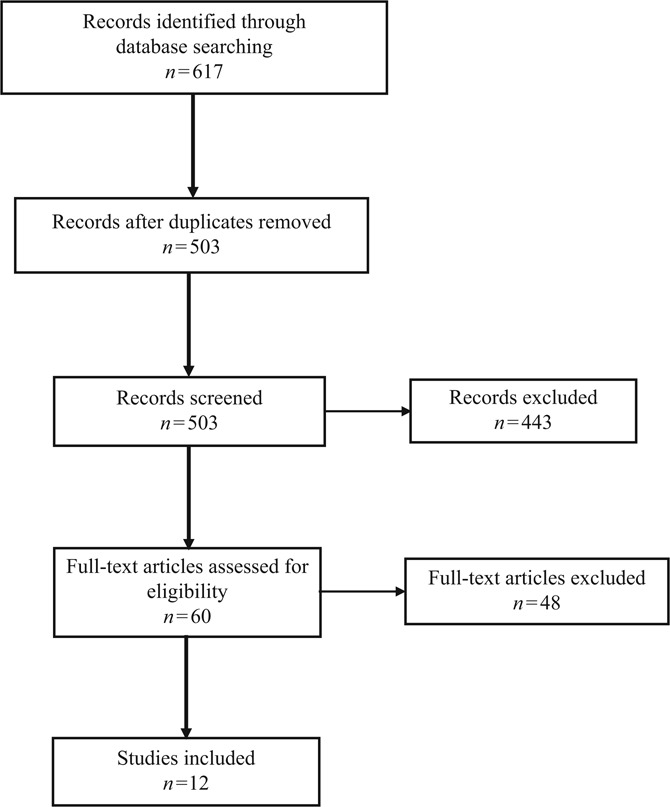

Two reviewers performed an assessment of the eligibility of potential studies for inclusion in the review of research on safety attitudes in EDs. All identified records from the aforementioned database searches (total of n = 617) were imported into EndNote citation software where duplicates were first identified and then removed. The 503 remaining titles and abstracts were screened against the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria such that studies where attitudes of hospital staff towards patient safety had been assessed and/or measured were included at this point of the review. Based on this set of criteria, an additional 443 studies were further excluded from the review, leaving a total of 60 eligible research articles. A final inclusion/exclusion criterion was then applied by removing articles where the study setting did not include a hospital ED. From this investigation, a total of 48 papers were excluded from the final review leaving 12 full-text research papers for in-depth analysis and review. Full-text articles were retrieved from an electronic library and examined in detail for the study design, sample, measures and findings. The study selection process is summarised in Figure 1 using the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Data were extracted included study sample and setting, type and number of participants, study design, variables and measurement tools and study findings. The quality of the reviewed articles was assessed through the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (NIH, 2017) which gives a score out of 14 to indicate the quality of research studies.

Results

In total, 12 studies met the inclusion criteria. The methodological characteristics, measures and findings from these articles are summarised in Table I. The studies covered a wide variety of settings including three studies in the USA, two studies in Sweden, and one study each in Australia, Brazil, Cyprus, Denmark, Iran, China and the Netherlands. Four studies were conducted in a single ED site, two studies were conducted in two sites, and six studies included participants from multiple ED sites (from 5 to 62). Whereas ten of the studies were quantitative cross-sectional designs with survey methods, two studies entailed the use of a qualitative phenomenological methodology with semi-structured interviews. Of the ten cross-sectional studies, two used a repeated measures design whereby participants completed a survey prior to and after a safety quality improvement intervention.

Table I.

Methodological characteristics of reviewed studies

| Study | Sample and setting | Design | Variables and measurement tool | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burstrom et al. (2014) | Participants were physicians and nurses recruited into the study to complete a questionnaire pre- and post-intervention. They were sampled from the emergency department of two hospitals in two different cities in central Sweden: a county hospital and a university hospital. There was relatively equal gender distribution of 92 physicians and 83 nurses among participants at the country hospital and similarly with 35 physicians and 99 nurses (post-intervention participant numbers) | A repeated cross-sectional survey study where participants completed the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture questionnaire before and after a quality improvement project | The 51-item Hospital survey on Patient Safety Culture was administered pre- and post-intervention. The Swedish version of the survey is a reliable and valid measure (Magid et al., 2009) and includes 15 dimensions with one to four items answered on a 5-point Likert scale | The overall rating of safety culture on most dimensions by doctors and nurses at both hospitals and at both measurement points was low (below the midpoint). However, a higher score was measured post-intervention on two dimensions with participants from the country hospital: teamwork within hospital and communication openness. At the university hospital, a higher score was measured at follow-up for the two dimensions: teamwork across hospital units and teamwork within hospital |

| Camargo et al. (2012) | The survey study was conducted in 62 urban EDs across 20 US states. There were 3,562 participants consisting of nurses (52.5%), physicians (22.2%) and other health personnel (25.3%) | A quantitative, descriptive cross-sectional study with survey methods | A 50-item Safety Climate questionnaire with 9-subscales was administered. The scale was reported to be a reliable and valid measure of Safety Climate (Patterson et al., 2010) with each item answered on 5-point Likert scale. Data were also collected on the number of adverse events and near misses in each ED | The overall rating of Safety Climate was 3.5/5 and was especially low on the subscale of Inpatient Coordination (2.4). No data were provided to compare safety climate as a function of profession. A higher safety climate score was not associated with the number of adverse events but was significantly associated with a higher incidence of intercepted near misses |

| Grover et al. (2017) | The study was set in a single major metropolitan emergency department in Melbourne, Australia. Participants were 12 registered nurses (9 female and 3 male) | A qualitative phenomenological study to address the question what are emergency nurses’ perceptions and attitudes towards teamwork? | Five semi-structured interview questions to ascertain and measure attitudes towards the teamwork aspect of patient safety climate | Participants perceived teamwork as an effective construct in resuscitation, simulation training, patient outcomes and staff satisfaction. Team support through back-up behaviour and leadership were perceived as critical elements of team effectiveness. Times were also reported when teamwork failed due including inadequate resources and skill mix |

| Källberg et al. (2017) | The study was conducted in 2 hospital EDs in Sweden at one large urban hospital and one medium-size country hospital. Participants were 10 physicians and 10 registered nurses | A qualitative phenomenological study using semi-structured interviews to investigate patient safety risks | Individual semi-structured interviews with a series of questions to describe events and situations in the ED where patient safety was compromised | Four main categories of patient safety risk were derived from inductive content analysis of the interview data: high workload, lack of control, communication failure and organisational failures |

| Lambrou et al. (2015) | EDs in 5 public general hospitals in Cyprus. Participants 174 nurses and 50 physicians | A descriptive correlational study to measure the association between perceptions of professional practice environment and patient safety | The 39-item Revised Professional Practice Environment (RPPE) Scale measures eight professional practice environment characteristics [Erickson]. A 60-item SAQ adapted for ED environments to measure perceptions of safety culture (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016) | Physicians assessed the professional practice environment more positively than nurses. The mean SAQ score was 3.18/5 and safety culture was significantly predicted by three RPPE subscales: Leadership and autonomy, Control over practice, and cultural sensitivity |

| Lisbon et al. (2016) | The study setting was an emergency department of an academic hospital in the USA. Participants were 113 emergency department staff including physicians, nurses and ancillary personnel at time 1 of the study; however, only 59 participants completed the full study | A repeated cross-sectional survey study where participants completed questionnaires on day 1, 45 and 90 of TeamSTEPPS training to develop a high-functioning team to improve patient safety | TeamSTEPPS Knowledge Test (Sarac et al., 2010) is a 21-question multiple-choice format exam to measure patient safety knowledge. The AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety (Sarac et al., 2010) assesses staff attitudes on patient safety culture in the hospital setting | χ2 tests showed knowledge and attitudes significantly improved 45 days from baseline and were sustained by day 90 |

| Rasmussen et al. (2014) | The study setting was an emergency department (ED) at a Danish regional hospital. A total of 98 nurses and 26 doctors were participants in the study | A quantitative, descriptive cross-sectional study with survey methods to measure the relationship between work environment and adverse events (AEs) | The SAQ was used to measure safety climate and teamwork. A Danish scale to measure reporting behaviour and learning environment. Involvement in an adverse event during the preceding month was reported using 43 items covering the classification of AEs from the Danish Patient Safety Database | There were significant positive relationships between the number of reported AEs and poor safety climate, poor team climate, poor inter-departmental working relationships and increased cognitive demands |

| Rigobello et al. (2017) | The study setting was an emergency department of a university teaching hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. There were 125 participants recruited into the study which was made up of mostly nurses, physicians and other health professionals | A quantitative, descriptive cross-sectional study with survey methods | The main variable was safety attitudes which were measured with the Portuguese version of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (Sexton et al., 2006). The SAQ measures six dimension of safety attitudes: stress recognition, perceptions of management, safety climate, teamwork climate, job satisfaction and working conditions | Of the six dimensions, participants only rated job satisfaction positively. The other dimensions were rated negatively, especially perceptions of management, safety climate and working conditions |

| Shaw et al. (2009) | The setting was 21 emergency departments in paediatric hospitals in the USA. A total of 1,747 staff members (49%) responded to a survey on the climate of safety including nurses, physicians and medical technicians | Quantitative cross-sectional design with survey methods | A validated survey to assess characteristics of emergency department physical structure, staffing patterns, overcrowding, medication administration, teamwork and methods for promoting patient safety (checked as either absent or present). A validated survey on the climate of safety. The survey has 19 questions regarding staff perceptions of the climate of safety each using a 5-point Likert-type scale | There was a wide range (28–82%) in the proportion reporting a positive safety climate across the 21 sites. Physicians’ ratings of the climate of safety were higher than nurses’ ratings. Characteristics associated with an improved climate of safety were a lack of ED overcrowding, a sick call back-up plan for physicians and the presence of an ED safety committee |

| Tourani et al. (2015) | The study setting was 11 EDs in hospitals affiliated with the Tehran Medical Science University in Iran. There were 270 participants comprised of doctors and nurses | Quantitative cross-sectional design with survey methods | The standard questionnaire of Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) was the main measurement tool which includes 42 statements that focus on 12 different aspects of patient safety | Half of the participants believed there was a problem in the error prevention procedures and systems, 30% reported their supervisor does not pay attention to their recommendations to improve the patients, and 40% reported hospital management show interest in the patients’ safety only when something goes wrong. More than half of the participants believed the nature of tasks in emergency wards, high workload, poor staffing and more than 40 h work a week has caused the staff in the emergency wards to work intensively with 57% of participants reporting there is lack of coordination among the wards |

| Verbeek-Van Nord et al. (2014), Verbeek-Van Nord et al. (2014) | The setting was 33 emergency departments in the Netherlands. Participants were 480 nurses, 159 physicians and 91 other health professionals | Quantitative cross-sectional design with survey methods | A Dutch version of the 40-item Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (Alzahrani, 2015) to measure safety culture covering 11 patient safety culture dimensions | Six dimensions of safety culture were positively associated with the reported level of patient safety: teamwork across units, frequency of event reporting, communication openness, feedback about and learning from errors, hospital management support for patient safety. Physicians rated overall perceptions of patient safety higher than nurses |

| Wang et al. (2014) | The study setting was 8 hospitals in Guangzhou, China to include one medical unit, one surgical unit, one intensive care unit and one emergency department from each hospital. A total of 463 registered nurse were participants in the study | Quantitative cross-sectional design with survey methods | The 42-item Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) measures 12 patient safety culture dimensions. A 7-item adverse events questionnaire was employed to measure the frequency of different adverse patient events from 0 = never to 6 = every day | Data were pooled across the four units and eight hospitals and showed an average patient safety culture score of 3.46/5 with most dimensions being rated below strong, especially hospital management support for patient safety and overall perceptions of safety. A higher mean score on two dimensions of the HSOPSC, “Organizational Learning-Continuous Improvement” and “Frequency of Event Reporting”, was significantly related to lower occurrence of adverse events |

Participants and measures

Across the 12 studies there were a total of 7,645 participants. Most participants were either nurses or physicians working in an ED. In the ten cross-sectional studies, participants completed a validated measure of patient safety culture attitudes, whereas participants in the qualitative studies answered open-ended questions about patient safety attitudes. Three cross-sectional studies also measured the number of adverse patient events to compare against safety attitudes.

Findings

The two studies that used a quantitative repeated measures design (Burstrom et al., 2014; Lisbon et al., 2016) entailed the use of a team building intervention to test the effects of the intervention on the safety attitudes of participants. Together, the interventions had some success because, post-intervention, the safety culture attitudes demonstrated improved teamwork and communication. Nevertheless, the safety attitudes of physicians and nurses from EDs were generally less than positive in both study settings even after the intervention.

A further eight studies were survey-based using cross-sectional designs where ED staff completed different measures of safety attitudes on one occasion (Rigobello et al., 2017; Shaw et al., 2009; Camargo et al., 2012; Lambrou et al., 2015; Rasmussen et al., 2014; Tourani et al., 2015; Verbeek-Van Nord et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). In two of these studies, physicians’ safety attitudes were reported as more positive than nurses (Shaw et al., 2009; Verbeek-Van Nord et al., 2014) although overall safety attitudes reported in six of the eight cross-sectional studies were generally low, especially on teamwork, in-patient coordination and management support. In contrast, job satisfaction was comparatively high in one study (Rigobello et al., 2017). Moreover, the findings from three studies showed more positive safety attitudes were associated with teamwork, communication and management support (Verbeek-Van Nord et al., 2014), improved management of EDs and the presence of an ED safety committee (Shaw et al., 2009), and leadership and autonomy, control over practice, and cultural sensitivity (Lambrou et al., 2015). Importantly, three studies compared safety attitudes to patient adverse event data (Camargo et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014) with only one study showing the number of adverse events was related to a poor safety and team climate, poor inter-departmental working relationships, and increased cognitive demands (Tourani et al., 2015). Of the reviewed studies, only two employed a qualitative research design (Grover et al., 2017; Källberg et al., 2017). These studies reported similar findings in that teamwork and team support, workload, and communication and organisational failures were found to be critical to enhanced patient safety.

Quality rating

The quality rating of each study was assessed through the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (NIH, 2017). According to the rating system, the quantitative intervention studies by Burstrom et al. (2014) and Lisbon et al. (2016) were the highest quality research with a score of 8/14 and 6/14, respectively (Burstrom et al., 2014; Lisbon et al., 2016). The fact that both studies employed an intervention to test the direct effect of an independent variable (IV) on a dependant variable (DV) distinguished the quality of these studies from the other studies in the review. Nevertheless, the study by Lisbon et al. (2016) had lower quality because the study population was not clearly defined and over 20 per cent of the participants were lost to follow-up.

The quality rating of the eight other quantitative studies in the review (Rigobello et al., 2017; Shaw et al., 2009) was quite low (between 3/14 and 6/14) and reflected the fact that each study employed a cross-sectional survey design with little control over extraneous or intervening variables where only the relationship between the IV and DV could be established. Similarly, the qualitative studies by Grover et al. (2017) and Källberg et al. (2017) were rated low (2/14) because each study did not employ a systematic sampling procedure or use valid and reliable measures (Grover et al., 2017; Källberg et al., 2017). Overall, each of the 12 studies failed to justify the sample size through appropriate use of power analysis and estimates of effect size. Furthermore, only one study (Wang et al., 2014) made an adjustment in analysis to take into account key potential confounding variables such as the gender, profession and years of practice of participants.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to perform a systematic review of published research on the patient safety attitudes of health care professional staff employed in hospital EDs. This systematic review of the current literature identified 12 studies, including 10 quantitative studies and 2 qualitative studies that met the inclusion criteria of studies where the safety attitudes of health care professionals from hospital EDs was ascertained. Given the number of studies to have investigated the safety attitudes of the front-line emergency staff of hospitals is comparatively few and patients within hospital EDs are especially vulnerable to medical errors (Shaw et al., 2009), there is justification for addressing the lack of research on the safety attitudes of emergency hospital staff in future studies.

Furthermore, additional research into the safety attitudes of hospital staff is justified because the current systematic review revealed the overall methodological quality of the reviewed studies was comparatively low. Despite some of the reviewed studies having large participant numbers which contribute to the validity of the findings, all the quantitative studies employed cross-sectional research designs which undermines the internal validity of the findings such that it is not possible to observe the direct effects of an IV on a DV. Nevertheless, two higher quality studies employed team building interventions that showed safety culture attitudes improved teamwork and communication post-intervention (Burstrom et al., 2014; Lisbon et al., 2016).

The importance of teamwork and communication to safety attitudes in hospital EDs was also evident in three of the other reviewed quantitative studies. In two of these studies (Shaw et al., 2009; Camargo et al., 2012), more positive safety attitudes were associated with teamwork, communication and management support as well as improved management of EDs and the presence of an ED safety committee. Similarly, one reviewed qualitative research design reported teamwork and team support as critical to enhanced patient safety (Grover et al., 2017). Nevertheless, teamwork and management support are often rated comparatively low on multidimensional safety attitude scales (Chaboyer et al., 2013; Profit et al., 2012; Alzahrani, 2015) such as the studies reviewed here show (Shaw et al., 2009; Verbeek-Van Nord et al., 2014). It would appear from the literature and the review of research reported here that human resource issues like teamwork and management support are related to lower safety attitudes of hospital staff and that interventions to improve these factors in the EDs of hospitals are likely to impact positively on safety attitudes.

The findings from this review that ED physicians’ safety attitudes were reported as more positive than nurses (Shaw et al., 2009; Verbeek-Van Nord et al., 2014) is consistent with previous research in other hospital departments. For example, Thomas et al. (2003) reported nurses rated the quality of collaboration and communication with physicians to be lower than the ratings of doctors. As surmised by Thomas, the findings are likely to be associated with differences in status/authority between nurses and physicians, differential responsibilities and training, gender issues, and nursing and physician cultures. Nevertheless, the findings of this review suggest the safety issues associated with the human resource components of a hospital ED are a particular focus for nurses.

Altogether, the findings contribute to the literature by being one of the first studies to systematically review the safety attitudes of health professionals in hospital EDs. Although the numbers of studies on this topic are limited, they do show that teamwork, communication and management support are central to positive safety attitudes, and that teamwork training can improve safety attitudes. Nevertheless, a strength of three of the reviewed studies was an investigation of the relationship between safety attitudes and adverse patient events (Camargo et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014) with one study showing the number of adverse events was related to a poor safety and team climate, poor inter-departmental working relationships, and increased cognitive demands (Rasmussen et al., 2014). Yet, the assumed relationship between safety attitudes and hospital error rates has not been clearly and unequivocally shown in the research literature on hospital safety (Steyrer et al., 2013; Ausserhofer et al., 2012). Given that EDs are the “front-line” of hospital care (Rigobello et al., 2017) and ED patients are especially vulnerable to medical errors (Shaw et al., 2009), future research on the safety attitudes of medical staff employed in hospital EDs and how they relate to medical errors is warranted.

Appendix. PubMed search strategy

“patient safety culture” OR “safety culture survey” OR “safety attitude questionnaire” OR “safety attitudes questionnaire” OR “safety attitude” OR “patient safety practice” OR (“Hospital Survey” AND “patient safety culture”) OR (“Patient Safety Culture” AND “survey”) OR “patient safety climate” OR “attitude of health personnel” OR (“safety culture” OR “safety practice” OR “safety climate”)

AND

(emergency OR “emergency department” OR hospital OR hospitals OR “emergency room” OR attitude OR attitudes OR “adverse events” OR “medical errors” OR “adverse events” OR “hospital staff” OR “safety management” OR patients OR patient OR “primary care”) OR “hospital patient climate safety scale”.

References

- Abdou A. and Saber K.M. (2011), “A baseline assessment of patient safety culture at student university hospital”, World Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 17-26. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2016), “TeamSTEPPS: strategies and tools to enhance performance and patient safety”, available at: www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html (accessed 27 September 2017). [PubMed]

- Alayed A.S., Loof H. and Johansson U.-B. (2014), “Saudi Arabian ICU safety culture and nurses’ attitudes”, International Journal of Health Care: Quality Assurance, Vol. 27 No. 7, pp. 581-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S. (2009), “Developing a safety culture: the unintended consequence of a ‘one size fits all’ policy”, PhD thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi A.F., Gardner G. and McCarthy A. (2013), “Perceptions of clinical safety climate of the multicultural nursing workforce in Saudi Arabia”, Collegian, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 187-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani A.S. (2015), “Clinicians’ attitudes toward patient safety: a sequential explanatory mixed methods study in Saudi armed forces hospitals (Eastern Region)”, PhD dissertation, Curtin University, Perth. [Google Scholar]

- Ausserhofer D., Schubert M., Desmedt M., Blegen M.A., De Geest S. and Schwendimann R. (2012), “The association of patient safety climate and nurse-related organizational factors with selected patient outcomes: a cross-sectional study”, International Journal of Nursing Studies, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 240-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigham B.L., Buick J.E., Brooks S.C., Morrison M., Shojania K.G. and Morrison L.J. (2012), “Patient safety in emergency medical services: a systematic review of the literature”, Prehospital Emergency Care, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 20-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blegen M.A., Pepper G.A. and Rosse J. (2005), “Safety climate on hospital units: a new measure”, Advances in Patient Safety, Vol. 4, pp. 428-443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondevik G.T., Hofoss D., Hansem E.H. and Deilkas E.C.T. (2014), “Patient safety culture in Norwegian primary care: a study in out-of-hours casualty clinics and GP practices”, Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, Vol. 32 No. 3, pp. 132-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstrom L., Letterstal A., Engstrom M.L., Berglund A. and Enlund M. (2014), “The patient safety culture as perceived by staff at two different emergency departments before and after introducing a flow-oriented working model with team triage and lean principles: a repeated cross-sectional study”, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 14, p. 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo C.A. Jr, Tsai C.L., Sullivan A.F., Cleary P.D., Gordon J.A., Guadagnoli E., Kaushal R., Magid D.J., Rao S.R. and Blumenthal D. (2012), “Safety climate and medical errors in 62 US emergency departments”, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 60 No. 5, pp. 555-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P.A., Gottems L.B.D., Maia Pires M.R.G. and de Oliveira M.L.C. (2015), “Safety culture in the operating room of a public hospital in the perception of healthcare professionals”, Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagen, Vol. 23 No. 6, pp. 1041-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaboyer W., Chamberlain D., Hewson-Conroy K., Grealy B., Elderkin T., Brittin M., McCutcheon C., Longbottom P. and Thalib L. (2013), “Safety culture in Australian intensive care units: establishing a baseline for quality improvement”, American Journal of Critical Care, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCuccio M.H. (2015), “The relationship between patient safety culture and patient outcomes: a systematic review”, Journal of Patient Safety, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 135-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie E.A. (2006), “The relation between nurses’ attitudes towards safety and reported medication error rates”, PhD thesis, New York University, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Elmontsri M., Almashrafi A., Banarsee R. and Majeed A. (2017), “Status of patient safety culture in Arab countries: a systematic review”, BMJ Open, Vol. 7, pp. 1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover E., Porter J.E. and Morphet J. (2017), “An exploration of emergency nurses’ perceptions, attitudes and experience of teamwork in the emergency department”, Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 92-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Källberg A.-S., Ehrenberg A., Florin J., Östergren J. and Göransson K.E. (2017), “Physicians’ and nurses’ perceptions of patient safety risks in the emergency department”, International Emergency Nursing, Vol. 33, pp. 14-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrou P., Papastavrou E., Merkouris A. and Middleton N. (2015), “Professional environment and patient safety in emergency departments”, International Emergency Nursing, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 150-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisbon D., Allin D., Cleek C., Roop L., Brimacombe M., Downes C. and Pingleton S.K. (2016), “Improved knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors after implementation of TeamSTEPPS training in an academic emergency department: a pilot report”, American Journal of Medical Quality, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid D.J., Sullivan A.F., Cleary P.D., Rao S.R., Gordon J.A., Kaushal R., Guadagnoli E., Camargo C.A. Jr and Blumenthal D. (2009), “The safety of emergency care systems: results of a survey of clinicians in 65 US emergency departments”, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 53 No. 6, pp. 715-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. and the PRISMA Group (2009), “Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement”, PLoS Medicine, Vol. 6 No. 7, pp. 1-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello R.T., Lowthian J.A., Barker A.L., McGinnes R., Dunt D. and Brand C. (2013), “Strategies for improving patient safety culture in hospitals: a systematic review”, BMJ Quality and Safety, Vol. 22, pp. 11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (2017), “Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies”, available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (accessed 22 December 2017).

- Patterson P.D., Huang D.T., Fairbanks R.J. and Wang H.E. (2010), “The emergency medical services safety attitudes questionnaire”, American Journal of Medical Quality, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Profit J., Etchegaray J., Petersen L.A., Sexton J.B., Hysong S.J., Mei M. and Thomas E.J. (2012), “Neonatal intensive care unit safety culture varies widely”, Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition, Vol. 97 No. 2, pp. F120-F126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K., Pedersen A.H., Pape L., Mikkelsen K.L., Madsen M.D. and Nielsen K.J. (2014), “Work environment influences adverse events in an emergency department”, Danish Medical Journal, Vol. 61 No. 5, pp. 1-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reason J.T. (1993), “The human factor in medical accidents”, in Vincent C. (Ed.), Medical Accidents, Oxford medical publications, Oxford, pp. 1-16. [Google Scholar]

- Rigobello M.C.G., Carvalho R.E.F.L., Guerreiro J.M., Motta A.P.G., Atila E. and Gimenes F.R.E. (2017), “The perception of the patient safety climate by professionals of the emergency department”, International Emergency Nursing, Vol. 33, pp. 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Paz J.M. and Dorman T. (2008), “Patient safety in the intensive care unit”, Clinical Pulmonary Medicine, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 24-34. [Google Scholar]

- Sarac C., Flin R., Mearns K. and Jackson J. (2010), “Measuring hospital safety culture: testing the HSOPSC scale”, Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton J.B., Helmreich R.L., Neilands T.B., Rowan K., Vella K., Boyden J., Roberts P.R. and Thomas E.J. (2006), “The safety attitudes questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research”, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 6, pp. 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton J.B., Berenholtz S.M., Goeschel C.A., Watson S.R., Holzmueller C.G., Thompson D.A., Hyzy R.C., Marsteller J.A., Schumacher K. and Pronovost P.J. (2011), “Assessing and improving safety climate in a large cohort of intensive care units”, Critical Care in Medicine, Vol. 39 No. 5, pp. 934-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K.N., Ruddy R.M., Olsen C.S., Lillis K.A., Mahajan P.V., Dean J.M., Chamberlain J.M. and Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (2009), “Pediatric patient safety in emergency departments: unit characteristics and staff perceptions”, Pediatrics, Vol. 124, pp. 485-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyrer J., Schiffinger M., Huber C., Valentin A. and Strunk G. (2013), “Attitude is everything?: the impact of workload, safety climate, and safety tools on medical errors: a study of intensive care units”, Health Care Management Review, Vol. 38 No. 4, pp. 306-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Health Foundation (2011), “Evidence scan: measuring safety culture”, available at: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/MeasuringSafetyCulture.pdf (accessed 25 February 2018).

- Thomas E.J., Sexton J.B. and Helmreich R.L. (2003), “Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurse and physicians”, Critical Care and Medicine, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 956-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourani S., Hassani M., Ayoubian A., Habibi M. and Zaboli R. (2015), “Analyzing and prioritizing the dimensions of patient safety culture in emergency wards using the TOPSIS technique”, Global Journal of Health Science, Vol. 7 No. 4, pp. 143-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek-Van Nord I., Wagner C., Van Dyck C., Twisk J.W. and De Bruijne M.C. (2014), “Is culture associated with patient safety in the emergency department? A study of staff perspectives”, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 64-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Liu K., You L.M., Xiang J.G., Hu H.G., Zhang L.F., Zheng J. and Zhu X.W. (2014), “The relationship between patient safety culture and adverse events: a questionnaire survey”, International Journal of Nursing Studies, Vol. 51 No. 8, pp. 1114-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver S.J. (2013), “Promoting a culture of safety as a patient strategy”, Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 369-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaprak E. and Intepeler S.S. (2015), “Factors affecting the attitudes of health care professionals toward medical errors in a public hospital in Turkey”, International Journal of Caring Sciences, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 647-655. [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- Hedsköld M., Pukk-Härenstam K., Berg1 E., Lindh M., Soop M., Øvretveit J. and Sachs M.A. (2013), “Psychometric properties of the hospital survey on patient safety culture, HSOPSC, applied on a large Swedish health care sample”, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 13, p. 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]