Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is the most common clinical presentation of allergy, affecting 400 million people worldwide, and with increasing incidence in westernized countries.1,2 To elucidate the genetic architecture and understand disease mechanisms of allergic rhinitis, we carried out a metaanalysis of allergic rhinitis in 59,762 cases and 152,358 controls of European ancestry and identified a total of 41 risk loci for allergic rhinitis, including 20 loci not previously associated with allergic rhinitis, which were confirmed in a replication phase of 60,720 cases and 618,527 controls. Functional annotation implied genes involved in various immune pathways, and fine mapping of the HLA region suggested amino acid variants of importance for antigen binding. We further performed GWASs of allergic sensitization against inhalant allergens and non-allergic rhinitis suggesting shared genetic mechanisms across rhinitis-related traits. Future studies of the identified loci and genes might identify novel targets for treatment and prevention of allergic rhinitis.

Main text

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is an inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa mediated by allergic hypersensitivity responses to environmental allergens1 with large adverse effects on quality of life and health care expenditures. The underlying causes for AR are still not understood and prevention of the disease is not possible. The heritability of AR is estimated to be more than 65%3,4. Seven loci have been associated with allergic rhinitis in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of AR per se, while other have been suggested from GWAS studies on related traits, such as self-reported allergy, asthma plus hay fever, or allergic sensitization5–9, but only few of these have been replicated.

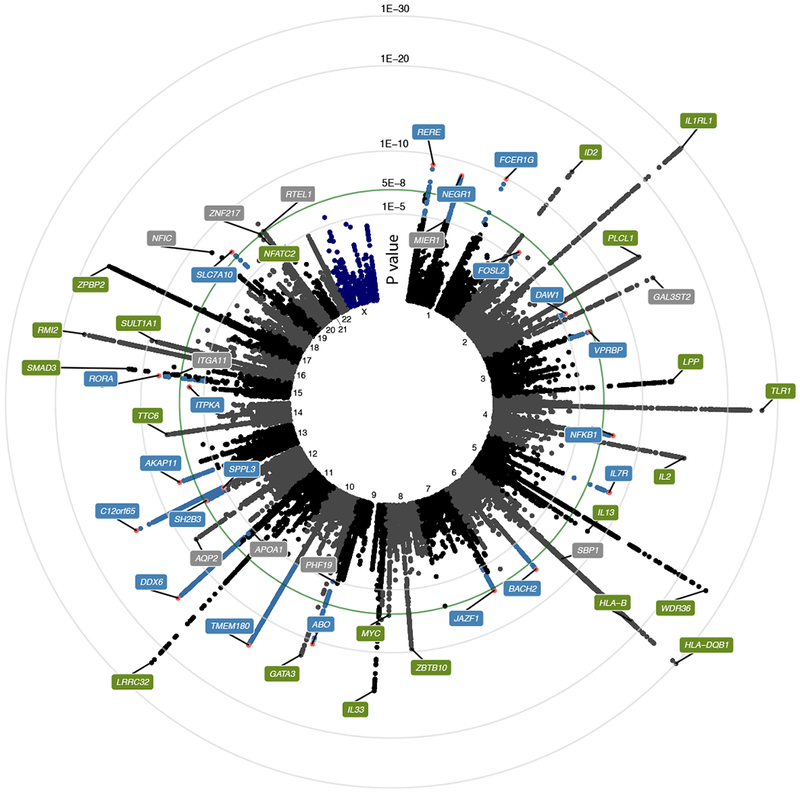

We carried out a large-scale meta-GWAS of AR including a discovery meta-analysis of 16,531,985 genetic markers from 18 studies comprising 59,762 cases and 152,358 controls of primarily European ancestry (Supplementary Table 1, cohort recruitment details in Supplementary Note). We report the genetic heritability on the liability scale of AR as at least 7.8% (assuming 10% disease prevalence), with a genomic inflation of 1.048 (Supplementary Figure 1). We identified 42 genetic loci, with index markers below genomewide significance (p<5e-8), of which 21 have previously been reported in relation to AR or other inhalant allergy6–9 (Fig. 1, Table 1, Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 1: Manhattan plot of the meta-GWAS discovery phase.

Circular plot of p-values from a inverse variance weighted fixed-effect meta-analysis of association of 16,531,985 genetic markers to allergic rhinitis from the discovery phase, including 212,120 individuals. Only markers with p < 1e-3 are shown. Labels indicate nearest gene name for index marker in locus (marker with lowest p-value). Green labels indicate loci previously associated with allergy; blue labels indicate novel AR loci; grey labels indicate novel loci that were not carried forward to the replication phase. Green line indicates level of genome wide significance (p = 5e-8).

Table 1.

Association results of index markers (variant with lowest p-value for each locus) previously reported in relation to AR or other inhalant allergy. Column “Nearest gene” denotes nearest up- and downstream gene (for intergenic variants with two genes listed), or surrounding gene (for intronic variants with one gene listed), with the exception of rs5743618, an exonic missense variant within TLR1. EA/OA=effect allele/other allele. P-value is calculated from the logistic regression model. Het.P=p-value for heterogeneity obtained from Cochrane’s Q test.

| Discovery |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant | Locus | Nearest genes | EA/OA | EAF | n (studies) | OR | 95% conf.int | P | Het. P |

| Known | |||||||||

| rs34004019 | 6p21.32 | HLA-DQB1;HLA-DQA1 | G/A | 0.27 | 196,951 (11) | 0.89 | 0.87-0.90 | 1.00E-30 | 0.41 |

| rs950881 | 2q12.1 | IL1RL1;IL1RL1 | T/G | 0.15 | 212,120 (18) | 0.88 | 0.87-0.90 | 1.74E-30 | 0.91 |

| rs5743618 | 4p14 | TLR1;TLR10 | A/C | 0.27 | 210,652 (17) | 0.90 | 0.89-0.92 | 4.38E-27 | 0.70 |

| rs1438673 | 5q22.1 | CAMK4;WDR36 | C/T | 0.50 | 212,120 (18) | 1.08 | 1.07-1.10 | 3.15E-26 | 0.26 |

| rs7936323 | 11q13.5 | LRRC32;C11orf30 | A/G | 0.48 | 212,120 (18) | 1.08 | 1.06-1.09 | 6.53E-24 | 0.0001 |

| rs2428494 | 6p21.33 | HLA-B;HLA-C | A/T | 0.42 | 195,753 (12) | 1.08 | 1.06-1.09 | 7.01E-19 | 0.25 |

| rs11644510 | 16p13.13 | RMI2;CLEC16A | T/C | 0.37 | 212,120 (18) | 0.93 | 0.92-0.95 | 1.58E-17 | 0.65 |

| rs12939457 | 17q12 | GSDMB;ZPBP2 | C/T | 0.44 | 212,120 (18) | 0.94 | 0.92-0.95 | 2.35E-17 | 0.02 |

| rs148505069 | 4q27 | IL21;IL2 | G/A | 0.33 | 212,120 (18) | 1.07 | 1.05-1.08 | 2.54E-15 | 0.02 |

| rs13395467 | 2p25.1 | ID2;RNF144A | G/A | 0.28 | 212,120 (18) | 0.94 | 0.92-0.95 | 9.93E-15 | 0.61 |

| rs9775039 | 9p24.1 | IL33;RANBP6 | A/G | 0.16 | 212,120 (18) | 1.08 | 1.06-1.10 | 2.22E-14 | 0.40 |

| rs2164068 | 2q33.1 | PLCL1 | A/T | 0.49 | 212,120 (18) | 0.94 | 0.93-0.96 | 4.21E-14 | 0.82 |

| rs2030519 | 3q28 | TPRG1;LPP | G/A | 0.49 | 212,120 (18) | 1.06 | 1.04-1.07 | 1.83E-13 | 0.12 |

| rs11256017 | 10p14 | CELF2;GATA3 | T/C | 0.18 | 212,120 (18) | 1.07 | 1.05-1.09 | 2.72E-12 | 0.60 |

| rs17294280 | 15q22.33 | AAGAB;SMAD3 | G/A | 0.25 | 212,120 (18) | 1.07 | 1.05-1.09 | 5.97E-12 | 0.07 |

| rs7824993 | 8q21.13 | ZBTB10;TPD52 | A/G | 0.37 | 212,120 (18) | 1.05 | 1.04-1.07 | 1.86E-10 | 0.56 |

| rs9282864 | 16p11.2 | SULT1A1;SULT1A2 | C/A | 0.33 | 208,761 (16) | 0.94 | 0.93-0.96 | 4.69E-10 | 0.03 |

| rs9687749 | 5q31.1 | IL13;RAD50 | T/G | 0.44 | 207,604 (16) | 1.06 | 1.04-1.09 | 1.84E-09 | 0.19 |

| rs61977073 | 14q21.1 | TTC6 | G/A | 0.22 | 212,120 (18) | 1.06 | 1.04-1.08 | 5.78E-09 | 0.05 |

| rs6470578 | 8q24.21 | TMEM75;MYC | T/A | 0.28 | 212,120 (18) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.07 | 4.36E-08 | 0.02 |

| rs3787184 | 20q13.2 | NFATC2;KCNG1 | G/A | 0.19 | 207,604 (16) | 0.94 | 0.93-0.96 | 4.76E-08 | 0.69 |

Table 2.

Association results of index markers (variant with lowest p-value for each locus) not previously associated with AR reaching a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of 0.05 in the replication phase. Column “Nearest gene” denotes nearest up- and downstream gene (for intergenic variants with two genes listed), or surrounding gene (for intronic variants with one gene listed), with the exception of rs1504215, an exonic synonymous variant within BACH2. EA/OA=effect allele/other allele. P-value is calculated from the logistic regression model. Het.P=p-value for heterogeneity obtained from Cochrane’s Q test. * Variants also reported associated with a combined asthma/eczema/hay fever phenotype by Ferreira et al.29 (within +/− 1Mb).

| Discovery | Replication | Combined | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant | Locus | Nearest genes | EA/OA | EAF | n (studies) | OR | 95% conf.int | P | Het. P | n (studies) | OR | 95% conf.int | P | FWER | n (studies) | OR | 95% conf.int | P | Het. P |

| rs7717955* | 5p13.2 | CAPSL; IL7R | T/C | 0.27 | 212,120 (18) | 0.95 | 0.93-0.96 | 1.50E-09 | 0.24 | 679,247 (10) | 0.93 | 0.91-0.94 | 4.09E-25 | 1.06E-23 | 891,367 (28) | 0.94 | 0.93-0.95 | 3.78E-32 | 0.09 |

| rs63406760* | 12q24.31 | CDK2AP1; C12orf65 | G/- | 0.26 | 210,652 (17) | 0.93 | 0.91-0.95 | 5.12E-14 | 0.91 | 675,338 (7) | 0.95 | 0.93-0.96 | 3.27E-12 | 8.51E-11 | 885,990 (24) | 0.94 | 0.93-0.95 | 2.54E-24 | 0.89 |

| rs1504215* | 6q15 | BACH2; GJA10 | A/G | 0.34 | 207,604 (16) | 0.95 | 0.94-0.97 | 1.49E-08 | 0.02 | 679,247 (10) | 0.95 | 0.94-0.97 | 1.99E-11 | 5.17E-10 | 886,851 (26) | 0.95 | 0.94-0.96 | 1.54E-18 | 0.05 |

| rs28361986* | 11q23.3 | CXCR5; DDX6 | A/T | 0.20 | 212,120 (18) | 0.93 | 0.91-0.95 | 1.81E-14 | 0.87 | 675,919 (8) | 0.94 | 0.93-0.96 | 7.92E-11 | 2.06E-09 | 888,039 (26) | 0.94 | 0.92-0.95 | 2.32E-23 | 0.91 |

| rs2070902* | 1q23.3 | AL590714.1; FCER1G | T/C | 0.25 | 212,120 (18) | 1.06 | 1.04-1.08 | 1.03E-10 | 0.18 | 679,247 (10) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.06 | 7.27E-10 | 1.89E-08 | 891,367 (28) | 1.05 | 1.04-1.06 | 6.19E-19 | 0.23 |

| rs111371454* | 15q15.1 | ITPKA; RTF1 | G/A | 0.21 | 212,120 (18) | 1.06 | 1.03-1.08 | 1.65E-07 | 0.17 | 675,338 (7) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.06 | 8.47E-09 | 2.20E-07 | 887,458 (25) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.06 | 1.28E-14 | 0.22 |

| rs12509403* | 4q24 | MANBA; NFKB1 | T/C | 0.32 | 212,120 (18) | 0.95 | 0.94-0.97 | 9.97E-09 | 0.27 | 679,247 (10) | 0.96 | 0.95-0.97 | 1.86E-08 | 4.84E-07 | 891,367 (28) | 0.96 | 0.95-0.97 | 1.17E-15 | 0.39 |

| rs9648346* | 7p15.1 | JAZF1; TAX1BP1 | G/C | 0.22 | 207,604 (16) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.07 | 3.62E-08 | 0.74 | 679,247 (10) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.06 | 1.39E-07 | 3.63E-06 | 886,851 (26) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.06 | 3.30E-14 | 0.48 |

| rs35350651* | 12q24.12 | ATXN2; SH2B3 | C/- | 0.49 | 206,136 (15) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.06 | 6.63E-08 | 0.60 | 672,701 (6) | 1.04 | 1.02-1.05 | 1.41E-07 | 3.66E-06 | 878,837 (21) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | 5.82E-14 | 0.43 |

| rs2519093* | 9q34.2 | ABO; OBP2B | T/C | 0.20 | 212,120 (18) | 1.06 | 1.04-1.09 | 4.96E-11 | 0.38 | 675,919 (8) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.06 | 2.96E-07 | 7.68E-06 | 888,039 (26) | 1.05 | 1.04-1.07 | 2.79E-16 | 0.61 |

| rs62257549 | 3p21.2 | VPRBP | A/G | 0.20 | 212,120 (18) | 0.95 | 0.93-0.97 | 7.13E-08 | 0.45 | 677,615 (9) | 0.96 | 0.94-0.97 | 3.37E-07 | 8.76E-06 | 889,735 (27) | 0.95 | 0.94-0.97 | 1.84E-13 | 0.53 |

| rs11677002 | 2p23.2 | FOSL2; RBKS | C/T | 0.45 | 212,120 (18) | 0.96 | 0.95-0.98 | 3.80E-07 | 0.21 | 679,247 (10) | 0.97 | 0.96-0.98 | 3.54E-07 | 9.20E-06 | 891,367 (28) | 0.97 | 0.96-0.97 | 7.08E-13 | 0.36 |

| rs35597970* | 10q24.32 | ACTR1A; TMEM180 | -/A | 0.45 | 210,652 (17) | 1.06 | 1.04-1.07 | 1.34E-13 | 0.96 | 676,970 (8) | 1.03 | 1.02-1.05 | 4.37E-07 | 1.14E-05 | 887,622 (25) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | 5.42E-18 | 0.53 |

| rs2815765 | 1p31.1 | LRRIQ3; NEGR1 | T/C | 0.37 | 212,120 (18) | 0.95 | 0.94-0.97 | 1.18E-09 | 0.59 | 679,247 (10) | 0.97 | 0.95-0.98 | 6.16E-07 | 1.60E-05 | 891,367 (28) | 0.96 | 0.95-0.97 | 9.45E-15 | 0.52 |

| rs11671925* | 19q13.11 | CEBPA; SLC7A10 | A/G | 0.17 | 206,136 (15) | 0.94 | 0.92-0.96 | 1.80E-08 | 0.97 | 677,551 (9) | 0.96 | 0.94-0.98 | 2.80E-06 | 7.29E-05 | 883,687 (24) | 0.95 | 0.94-0.96 | 5.91E-13 | 0.60 |

| rs2461475* | 12q24.31 | SPPL3; ACADS | C/T | 0.47 | 212,120 (18) | 1.04 | 1.02-1.05 | 9.19E-07 | 0.97 | 677,551 (9) | 1.03 | 1.02-1.04 | 6.52E-06 | 0.0002 | 889,671 (27) | 1.03 | 1.02-1.04 | 3.81E-11 | 0.83 |

| rs6738964* | 2q36.3 | SPHKAP; DAW1 | G/T | 0.24 | 212,120 (18) | 0.96 | 0.94-0.97 | 4.51E-07 | 0.72 | 679,247 (10) | 0.97 | 0.96-0.98 | 4.96E-05 | 0.0013 | 891,367 (28) | 0.96 | 0.95-0.97 | 1.86E-10 | 0.87 |

| rs10519067* | 15q22.2 | RORA | A/- | 0.13 | 212,120 (18) | 0.93 | 0.91-0.96 | 1.78E-09 | 0.37 | 442,354 (7) | 0.93 | 0.90-0.96 | 7.53E-05 | 0.0020 | 654,474 (25) | 0.93 | 0.92-0.95 | 5.53E-13 | 0.36 |

| rs138050288* | 1p36.23 | RERE; SLC45A1 | -/CA | 0.29 | 210,652 (17) | 1.05 | 1.04-1.07 | 5.96E-10 | 0.71 | 675,338 (7) | 1.03 | 1.01-1.04 | 0.0002 | 0.0046 | 885,990 (24) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | 6.62E-12 | 0.63 |

| rs7328203 | 13q14.11 | TNFSF11; AKAP11 | G/T | 0.46 | 212,120 (18) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.06 | 5.94E-09 | 0.90 | 677,551 (9) | 1.02 | 1.01-1.04 | 0.0005 | 0.0134 | 889,671 (27) | 1.03 | 1.02-1.04 | 1.28E-10 | 0.78 |

One study (23andMe) had a proportionally large weight (~80%) in the discovery phase. Overall there was good agreement between 23andMe and the other studies with respect to effect size and direction, and regional association patterns (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 4+5), and the genetic correlation was 0.80 (p<2e-17). Heterogeneity between 23andMe and the remaining studies was statistically significant (p<0.05) for 7 of 42 loci, in most cases due to a smaller effect size in 23andMe. This was likely due to many non-23andMe studies using a more robust phenotype definition of doctor diagnosed AR (Supplementary Table 3), which tended to result in larger effect sizes (Supplementary Table 4).

The index markers from a total of 25 loci that had not previously been associated with AR or other inhalant allergy were carried forward to the replication phase. These included 16 loci that showed genome-wide significant association in the discovery phase and evidence of association (p<0.05) in both 23andMe and non-23andMe studies (Supplementary Table 2), and an additional 9 loci that were selected from the p-value stratum between 5e-8 and 1e-6 based on enrichment of gene sets involved in immune-signaling (Supplementary Table 5). Replication was sought in another 10 studies with 60,720 cases and 618,527 controls. Of the 25 loci, 20 loci reached a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of 0.05 (p<0.0019) in a metaanalysis of replication studies (Fig. 1 (blue), Table 2), and all of these reached genome-wide significance in the combined fixed-effect meta-analysis of discovery and replication studies (Table 2). Evidence of heterogeneity was seen for one of these loci (rs1504215), which did not reach statistical significance in the random effects model (0.95 [0.92; 0.97], p=2.83e-07, Supplementary Fig. 3).

A conditional analysis of top loci identified 13 additional independent variants at p<1e-5, with 4 of these being genome-wide significant (near WDR36, HLA-DQB1, IL1RL1 and LPP) (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 5, bottom panel).

To gain insight into functional consequences of known and novel loci, we utilized a number of data sources, including 1) 11 eQTL sets and 1 meQTL set from blood and blood subsets; 2) 2 eQTL sets and 1 meQTL set from lung tissue; and 3) data on enhancer-promoter interactions in 15 different blood subsets. Support of regulatory effects on coding genes was found for 33 out of the 41 loci. Many loci showed evidence of regulatory effects across a wide range of immune cell types (including B- and T-cells), while other seemed cell type-specific (Supplementary Table 7). Calculation of the “credible set” of markers for each locus using a Bayesian approach that selects markers likely to contain the causal disease-associated markers (Supplementary Table 8) and looking up these in the Variant Effect Predictor database generated a list of 17 markers producing amino acid changes, including deleterious changes in NUSAP1, SULT1A1 and PLCL, as predicted by SIFT (Supplementary Table 9).

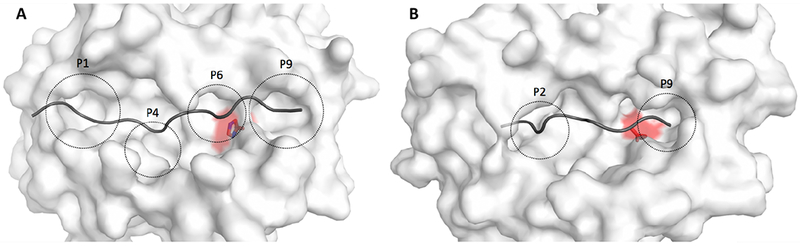

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on chr6p harbored some of the strongest association signals in the GWAS with independent signals located around HLA-DQB and HLA-B, respectively. The top variant at HLA-DQB was an eQTL for several HLA-genes, including HLA-DQB1, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, and HLA-DRB1 in immune and/or lung tissue, and the top variant at HLA-B was an eQTL for MICA (Supplementary Table 7). In addition we found associations with several classical HLA alleles, including HLA-DQB1*02:02, HLA-DQB1 *03:01, HLA-DRB1*04:01, and HLA-C*04:01, which were in weak LD (r2<0.1) with the GWAS top SNPs (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11), and strong associations with well imputed amino acid variants, including HLA-DQB1 His30 (p=2.06e-28, OR=0.91) and HLA-B AspHisLeu116 (p=6.00e-13, OR=1.06) (Supplementary Tables 12 and 13). Within HLA-DQB1, the amino acid variant was in moderate LD (r2=0.71) with the GWAS top SNP and accounted for most of the SNP association (rs34004019, p=2.18e-28, OR=0.88, conditional p-value=1.35e-03). Within HLA-B, the strongest associated amino acid variant was only in weak LD (r2=0.23) with the top SNP and accounted for a small part of the SNP association (rs2428494, p=3.99e-15, OR=1.07, conditional p-value=3.23e-10 ). Importantly, the strongest associated amino acid variants in HLA-DQB1 and HLA-B, respectively were both located in the peptide binding pockets with a high likelihood of affecting MHC-peptide interaction (Figure 2). MHC class II molecules, including HLA-DQ, are known for their role in allergen-binding and Th2 driven immune responses10 and our results therefore suggest that the GWAS signal at this locus involves structural changes related to allergen binding properties. This might be in addition to gene regulatory effects similar to what has been found for autoimmune disease.11,12 The majority of the 20 loci not previously associated with AR per se imply genes with a known role in the immune system, including IL7R13,14, SH2B315, CEBPA/CEBPG16, 17, CXCR518, FCER1G, NFKB119, BACH220, 21, TYRO322, LTK 23, VPRBP24, SPPL325, OASL26, RORA27, and TNFSF1128. Other loci imply genes with no clear function in AR pathogenesis. These include one of the strongest associated loci in this meta-analysis at 12q24.31 with the top-signal located between CDK2AP1 and C12orf65, harboring cis-eQTLs in blood and lung tissue for several genes and evidence for enhancer-promoter interaction with DDX55 in various immune cells. (Supplementary Table 14 and further locus description in the Supplementary Note). Concomitantly with the current study, a GWAS combining asthma, eczema and AR was conducted.29 The majority (15/20) of identified AR loci in our study were also suggested in the previous, more unspecific, GWAS29 (as indicated in Table 2), while many suggested loci from the previous GWAS were not identified in our study. Asthma, eczema and allergic rhinitis are related but distinct disease entities, often with seperate disease mechanisms, e.g. allergic sensitization is present in only 50% of children with asthma30 and 35% of children with eczema.31 Our results therefore complement those from the less specific “atopic phenotype” GWAS29 by pinpointing loci specifically associated, and replicated, in relation to allergic rhinitis.

Figure 2: Structural visualization of amino acid variants associated with allergic rhinitis.

The surface of the MHC molecule is shown in white, while the backbone of the bound peptide is shown in dark gray. The amino acid variant in focus is highlighted in red and the peptide binding pockets of the MHC molecule is indicated with dashed circles and annotated P1-P9. (A) The amino acid variant with strongest association to AR is HLA-DQB1 His30 (MHC class II), located close to P6 with a distance of 6Å to the peptide (excluding the peptide side chain). The protective amino acid variant at this location in relation to AR is hisitidine, whereas the risk variant is serine. Histidine is positively charged and has a large aromatic ring, whereas serine is not charged and not aromatic. Therefore, this mutation results in a significant change of the binding pocket environment. (B) The strongest AR-associated amino acid variation in HLA-B (MHC class I) is HLA-B AspHisLeu116, located close to P9 with a distance of 7Å to the peptide (excluding the peptide side chain). The close proximity to the bound peptide for both variants indicates that they are likely to affect the MHC-peptide interaction and thereby which peptides are presented.

AR loci were significantly enriched (p<1e-5) for variants reported to be associated with autoimmune disorders. Reported autoimmune variants were located within a 1mb distance of 31 (76%) of the 41 AR loci. For 24 of these, an autoimmune top SNP was also associated with AR, and for 12 of these the autoimmune top SNP was in LD (r2>0.5) with the AR top SNP (Supplementary Table 15). For approximately half of these, the direction of effect was the same for the autoimmune and AR top SNP in line with a previous study,32 underlining the complex genetic relationship between AR and autoimmunity, which might involve shared as well as diverging molecular mechanisms.

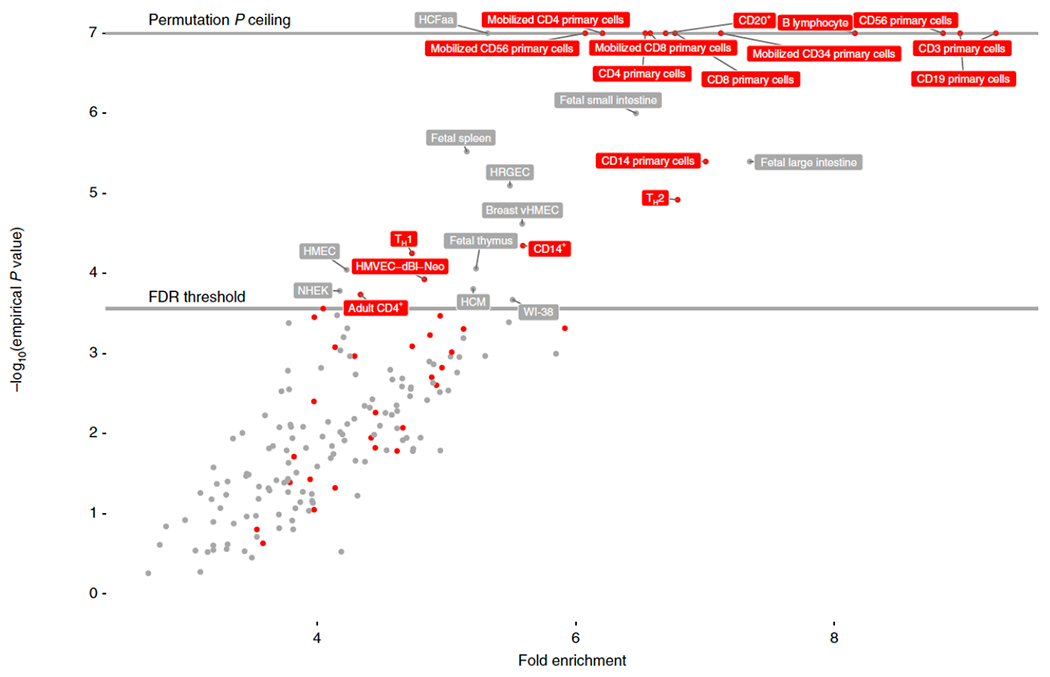

Assessment of enrichment of AR-associated variant burden in open chromatin as defined by DNAse hypersensitive sites showed a clear enrichment in several blood and immune cell subsets, with the largest enrichment in T-cells (CD3 expressing), B-cells (CD19 expressing), and T and NK-cells (CD56-expressing) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 16, Supplementary Fig. 6). We also probed tissue enrichment by means of gene expression data from a wide number of sources, showing enrichment of AR genes in blood and immune cell subsets, as well as in tissues of the respiratory system, including oropharynx, respiratory and nasal mucosa (Supplementary Table 17).

Figure 3: Enrichment of allergic rhinitis-associated variants in tissue-specific open chromatin.

Enrichment of 16,531,985 genetic variants associated with allergic rhinitis in 212,120 individuals (at p < 1e-08 as threshold for marker association) in 189 cell types from ENCODE and Roadmap epigenomics data. Enrichment and p-value was calculated empirically against a permuted genomic background using the GARFIELD tool. Red labels indicate blood and blood-related cell-types, grey labels indicate other cell types. Due to number of permutations = 1e7, empirical p-values reached a minimum ceiling of 1/1e7. FDR threshold = 0.00026. For epstein-Barr virus transformed B-lymphocyte cell types (cell type “GM****”), only most enriched instance is shown (“B-Lymphocyte”). NHEK = normal human epidermal keratinocytes, HMEC/vHMEC = mammary epithelial cells, HCM = human cardiac myocytes , WI-38 = lung fibroblast-derived, HRGEC = human renal glomerular endothelial cell, HCFaa = Human Cardiac Fibroblasts-Adult Atrial cell, HMVEC-dBl-Neo = human microvascular endothelial cells, Th1 = T helper cell, type 1, Th2 = T helper cell, type 2.

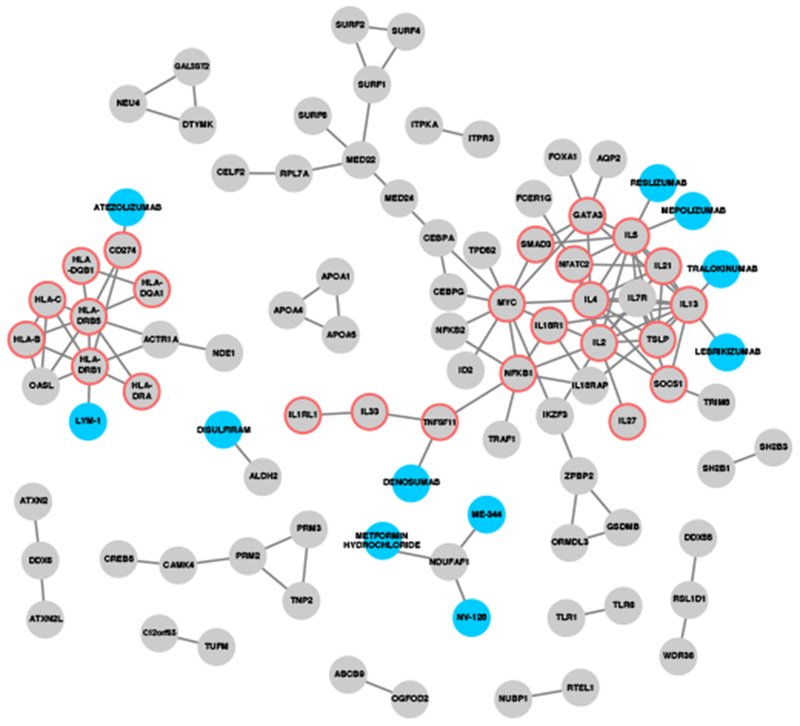

To explore biological connections and identify new pathways associated with AR, we combined all genes suggested from eQTL/meQTL analyses, enhancer-promoter interactions and localization within the top loci. The resultant prioritized gene set consisted of 255 genes, of which 89 (~36%) were present in more than one set (Supplementary Fig. 7). Overall, the full set was enriched for pathways involved in Th1 and Th2 Activation (Fig. 4), antigen presentation, cytokine signaling, and inflammatory responses (Supplementary Table 18).

Figure 4: Interaction network between drugs and proteins from genes associated with allergic rhinitis.

Grey nodes represent locus genes as well as genes prioritized from e/meQTL and PCHiC sources, based on genetics association of 16,531,985 markers with allergic rhinitis in 212,120 individuals. Blue nodes represent drugs from the ChEMBL drug database. Edges represent very-high confidence interactions from the STRING database (for locus-locus interactions) and drug target evidence (for drug-locus interactions). Red borders indicate genes with protein products that were significantly enriched in the “Th1 and Th2 Activation” pathway (-log[p-value] >19.1) from the IPA pathway analysis.

Using the 255 prioritized genes in combination with STRING to identify proteins that interact with the proteins encoded by the high priority genes, we demonstrated a high degree of interaction at the protein level, and several of these proteins are target of approved drugs or drugs in development, including TNFSF11, NDUFAF1, PD-L1, IL-5, and IL-13 (Fig. 4).

AR is strongly correlated to allergic sensitization (presence of allergen-specific IgE), but sensitization is often present without AR suggesting specific mechanisms determining progression from sensitization to disease. We therefore conducted a GWAS on sensitization to inhalant allergens (AS) comprising 8,040 cases and 16,441 controls from 13 studies (Supplementary Table 1), making it the largest GWAS on allergic sensitization to date7. A total of 10 loci reached genome-wide significance, including one novel hit near the FASLG gene (Supplementary Table 19). The genetic heritability on the liability scale was 17.75% (10% prevalence), considerably higher than the heritability of AR in consistency with a more homogeneous phenotype. Look-up of AR top-loci in the AS GWAS demonstrated large agreement with 40 of the 41 AR markers showing same direction of effect and 28 also showing nominal significance for AS (Supplementary Table 20). This suggests that AR and AS share biological mechanisms and that AS loci generally affect systemic allergic sensitization. We compared genetic pathways of AR and AS using the DEPICT tool showing overlap in enriched pathways but also differences among the top gene sets, with AR gene sets characterized by B-cell, Th2, and parasite responses and AS gene sets characterized by a broader activation of cells (Supplementary Fig 8 and Supplementary Tables 21 and 22).

Non-allergic rhinitis, defined as rhinitis symptoms without evidence of allergic sensitization, is a common but poorly understood disease entity.33 We performed the first GWAS on this phenotype hypothesizing that this might reveal specific rhinitis mechanisms. The analysis included 2,028 cases and 9,606 controls from 9 studies but did not identify any risk loci at the genome-wide significance level. Comparison with AR results suggested some overlap in susceptibility loci (Supplementary Note and Supplementary Table 23).

We estimated the proportion of AR in the general population that can be attributed to the 41 identified AR loci and obtained a conservative population-attributable risk fraction estimate of 39% (95% CI 26%−50%), considering the 10% of the population with the lowest genetic risk scores to represent an ‘unexposed’ group. Allergic rhinitis prevalence plotted by genetic risk score (Supplementary Fig. 9) showed approximately 2 times higher prevalence in the 7% of the population with the highest risk score compared to the 7% with the lowest risk score.

Finally, we investigated the genetic correlation of AR with AS, asthma34, and eczema35 by LD score regression. There was a strong correlation between AR and AS (r2=0.73, p<2e-34), moderate with asthma (r2=0.60, p<3e-14) and weaker with eczema (r2=0.40, p<2e-07).

The identified AR loci were tested for association with AR in non-European cohorts, only showing nominal significant association for a loci, but this analysis had limited statistical power due to population sizes (Supplementary Table 24).

In conclusion, we expanded the number of established susceptibility loci for AR and highlighted involvement of AR susceptibility loci in diverse immune cell types and both innate and adaptive IgE-related mechanisms. Future studies of novel AR loci might identify targets for treatment and prevention of disease.

Methods:

Phenotype definition

Allergic rhinitis (AR)

Cases were defined as individuals ever having a diagnosis or symptoms of AR dependent on available phenotype definitions in the included studies (Supplementary Table 3 and cohort recruitment details in Supplementary Note). All relevant ethical regulations were followed as specified in relation to the individual studies in the Supplementary Note. To maximize numbers and optimize statistical power, we did not require doctor-diagnosed AR or verification by allergic sensitization. This approach was confirmed by a sensitivity analysis in 23andMe based on association with known risk loci for allergic rhinitis (data not shown). Controls were defined as individuals who never had a diagnosis or symptoms of AR.

Allergic sensitization (AS)

We considered specific IgE production against inhalant allergens without restriction by assessment method or type of inhalant allergen. Cases were defined as individuals with objectively measured sensitization against at least one of the inhalant allergens tested for in the respective studies, and controls were defined as individuals who were not sensitized against any of the allergens tested for. We included sensitization assessed by skin reaction after puncture of the skin with a droplet of allergen extract (SPT) and/or by detection of the levels of circulating allergen-specific IgE in the blood. The SPT wheal diameter cutoffs were 3 mm larger than the negative control for cases and smaller than 1 mm for controls. To optimize case specificity and the correlation between methods, we chose a high cutoff of specific IgE levels for cases (0.7 IU/ml) and a low cutoff for controls (0.35 IU/ml).

Non-allergic rhinitis (NAR)

Case were defined as individuals with current allergic rhinitis symptoms (within the last 12 months) and no allergic sensitization (negative specific IgE (< 0.35 IU/mL) and/or negative skin prick test (< 1 mm) for all allergens and time points tested)

Controls were defined as individuals never having symptoms of allergic rhinitis and no allergic sensitization (negative specific IgE (< 0.35 IU/mL) and/or negative skin prick test (< 1 mm) for all allergens and time points tested)

For all 3 phenotypes, we combined data from children and adults but chose a lower age limit of 6 years, as allergic rhinitis and sensitization status at younger ages show poorer correlation with status later in life, both owing to transient symptoms/sensitization status and frequent development of symptoms/sensitization during late childhood.

GWAS QC and cohort summary data harmonization

For AR, AS, and NAR, each cohort imputed their data separately using the 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP) phase 1, version 3 release, and conducted the genome-wide association analysis adjusted for sex and if necessary for age and principal components (Supplementary Table 3). All studies included individuals of European descent, except Generation R and RAINE, comprising a mixed, multi-ethnic population. We utilized EasyQC v. 9.236 for quality control and marker harmonization for cohort-level meta-GWAS summary files. Cohort data was harmonized to genome build GRCh37 and checked against 1KGP phase 3 reference allele frequencies for processing problems. GWAS summary “karyograms” were visually inspected to catch cohorts with incomplete data. Distributions of estimate coefficients and errors, as well as “Standard error vs. sample size”- and “p value vs. z-score” plots were inspected for each cohort for systematic errors in statistical models. Ambiguous markers that were non-unique in terms of both genomic position and allele coding were removed. A minimum imputation score of 0.3 (R2) or 0.4 (proper_info) was required for markers. A minimum minor allele count of 7 was required for each marker in each cohort, as suggested by the GIANT consortium and EasyQC.

Meta-Analysis

For AR, AS, and NAR, meta-analysis for the discovery phase was conducted using GWAMA37 with an inverse variance weighted fixed-effect model with genomic control correction of the individual studies. Each locus is represented by the variant showing the strongest evidence within a 1Mb buffer. Loci were inspected visually by plotting genomic neighbourhood and coloring for 1KGP r2 values. From the pool of genomewide significant markers in the discovery, one locus with index marker rs193243426 without a credible LD structure was removed from further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 10). Heterogeneity was assessed with Cochran’s Q test. Meta-analysis of replication candidates from the AR discovery phase was carried out using R version 3.4.0, and the meta package version 4.8-2 with an inverse variance weighted fixed-effect model. For a subset of markers, cohorts reported suitable proxies (r2>0.85), where followed-up markers were not present or had insufficient imputation or genotyping quality (Supplementary Table 25).

Gene set overrepresentation analysis, discovery phase

To facilitate selection of biologically relevant discovery candidates in the sub-genomewide significant stratum (5e-8 < p < 1e-6), we employed a custom gene set overrepresentation analysis algorithm implemented in R, with a scoring and permutation regime modeled after MAGENTA.38 Genes with lengths less than 200bp, with copies on multiple chromosomes, and with multiple copies on the same chromosome more than 1 Mb apart were removed from analysis. Gene models (GENCODE v 19) were downloaded from the UCSC Table Browser,39 and expanded 110 kb upstream, and 40 kb downstream, similar to MAGENTA. The HLA region was excluded from analysis (chromosome 6: 29,691,116-33,054,976). Similar to MAGENTA, gene scores were adjusted for number of markers per gene, gene width, recombination hotspots, genetic distance, and number of independent markers per gene, all with updated data from UCSC Table Browser. For the gene set overrepresentation permutation calculation, gene sets from the MSigDB collections c2, c3, c5, c7, and hallmark, were included.40 A MAGENTA-style enrichment cutoff at 95% was used. Gene sets with FDR<0.05 were considered.

Conditional analyses

To identify additional independent markers at each discovery genomic region, we used Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) v. 1.26.0.41 Within a window of +/− 1Mb of each discovery phase index marker, all markers were conditioned on the index using the --cojo-cond feature of GCTA with default parameters. Plink v. 1.90b3.4242 was used to calculate r2 for GCTA with the UK10K full genotype panel43 as reference. A total of 42 of 52 markers from the full discovery phase were present in UK10K. As a MAF-dependent inflation of conditional p-values was observed (data not shown), only conditional markers with MAF >= 10% were selected.

Locus definition and credible sets for VEP annotation

Discovery loci were defined as index markers extended with markers in LD (r2 >= 0.5), based on the 1KGP phase 3. Protein coding gene transcript models (GENCODE v. 24) were downloaded from the UCSC Table Browser, and nearest upstream, downstream, as well as all genes within the extended loci were annotated.

Credible sets for each locus were calculated using the method of Morris, A.P44.

LD was calculated for each discovery index variant within +/− 500 kb, and markers with r2<0.1 were excluded. For the remaining markers, the Bayesian Factor (ABF) values and the posterior probabilities (PostProb) were calculated, and cumulative posterior probability values were generated based ranking markers on ABF. Finally, variants were included in the 99% credible set until the cumulative posterior probability was greater or equal than 0.99.

Credible sets for each loci was annotated with information on mutation impact in coding regions using the Variant effect Prediction (VeP) REST API45, exporting only the nonsynonymous substitutions.

GWAS catalogue lookup

For annotation of markers with identification in previous GWA studies, the GWAS catalog was downloaded from NHGRI-EBI (v.1.0.1,2016-11-28). For this analysis, AR loci were lifted from genomic build GRCh37 to GRCh38, and extended with +/− 1Mb in each direction before being overlapped with GWAS catalog annotations. Relevant GWAS catalog overlap traits were binned into trait groups “Allergic Rhinitis”, “Asthma”, “Autoimmune”, “Eczema”, “Infectious Diseases”, “Lung-related Traits”, and “Other allergy”. A million random genomic intervals of the same length (2Mb) were obtained to generate a background overlap distribution, and p-values were calculated from this background.

HLA classical allele analysis

Analyses of imputed classical HLA-alleles were performed in the 23andMe study (AR discovery population) comprising 49,180 individuals with allergic rhinitis and 124,102 controls.

HLA imputation was performed with HIBAG v. 1.2.3.46 We imputed allelic dosage for HLA-A, B, C, DPB1, DQA1, QB1, and DRB1 loci at four-digit resolution using the default settings of HIBAG for a total of 292 classical HLA alleles.

Using an approach suggested by P. de Bakker,47 we downloaded the files that map HLA alleles to amino acid sequences from https://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snp2hla/ and mapped our imputed HLA alleles at four-digit resolution to the corresponding amino acid sequences; in this way we translated the imputed HLA allelic dosages directly to amino acid dosages. We encoded all amino acid variants in the 23andMe European samples as 2395 bi-allelic amino acid polymorphisms as previously described.48

Similar to the SNP imputation, we measured imputation quality using r2, which is the ratio of the empirically observed variance of the allele dosage to the expected variance assuming Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

To test associations between imputed HLA alleles, amino acid variants, and phenotypes, we performed logistic regression using the same set of covariates used in the SNPbased GWAS. We applied a forward stepwise strategy, within each type of variant, to establish statistically independent signals in the HLA region. Within each variant type, we first identified the most strongly associated signals (lowest p-value) and performed forward iterative conditional regression to identify other independent signals. All analyses were controlled for sex and five principal components of genetic ancestry. The p-values were calculated using a likelihood ratio test.

Structural visualization of amino acid variants

Structural visualization of amino acid variants was performed for the strongest associated variants in HLA-DQB1 (position 30) and HLA-B (position 116), respectively (Supplementary Table 10) and were made using X-ray structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).49 To find the best structure we used the specialized search function in the Immune Epitope Database,50 selecting only X-ray crystalized structures for the specific MHC classes HLA-DQB1 (class II) and HLA-B (class I). Using this criterion, we found 17 crystallized structures for HLA-DQB1 and 164 structures for HLA-B. From these lists, we selected the structure with the lowest resolution and the amino acids encoded by the reported top SNPs. The PDB accession code for the selected structures was 4MAY51 for HLA-DQB1 and 2A8352 for HLA-B and both structures were visualized using PyMOL v. 1.8.2.1 (http://www.pymol.org). Furthermore, we used PyMOL to measure intra-molecular distances from the side chain of the amino acids associated with allergic rhinitis to the Cα atoms in the peptide. This distance measure was chosen to accommodate the possibility for different amino acids in the peptide. In order for two amino acids to interact the distance should be approximately 4Å or less. We measured distances of 6Å (HLA-DQB1) and 7Å (HLA-B). However these distances do not include the peptide side chains which range from 1.5 Å - 8.8 Å. Therefore, we estimate that physical interaction between the amino acids encoded by the top SNPs and the peptide is likely.

Genetic heritability and genetic correlation

For calculating genetic heritability and genetic correlation between AR and AS, as well as between clinical cohorts and 23andMe within AR, we utilized the LD score regression based method as implemented by LDSC v. 1.0.45,53 Population prevalence was set to 10% for AR and AS. Genetic correlation analysis between AR, AS and published GWAS studies was carried out using the LDHUB platform v. 1.3.154 against all traits, but excluding Metabolites55.

eQTL sources and analysis

From GTEx V6p56, all significant variant-gene cis eQTL pairs for whole blood, lung, and EBV-transformed lymphocytes were downloaded from https://gtexportal.org, and carried forward in analysis. From Westra et al.57, both cis and trans eQTLs in whole blood were downloaded, and variant-gene pairs with FDR < 0.1 were carried forward in analysis. From Fairfax et al.58, cis eQTLs from monocytes and B cells were downloaded, and variant-gene pairs with FDR < 0.1 were carried forward in analyses. From Bonder et al.58, meQTLs from whole blood were downloaded, and variant-probe pairs with FDR < 0.05 were carried forward in analyses. From Nicodemus-Johnson et al.59, cis eQTLs and meQTLs from lung were downloaded, and variant-gene pairs with FDR < 0.1 were carried forward in analyses. From Momozawa et al. [in press, personal correspondence], cis eQTLs from blood cell types CD14, CD15, CD19, CD4, and CD8 were downloaded, and variant-gene pairs with a weighted correlation of >= 0.6 were carried forward to analysis. For supplementary table 14 priority genes, protein coding information was downloaded from the UCSC Table Browser, using the “transcriptClass” field from the “wgEncod eGencod eAttrsV241 ift37” table.

Promoter Capture Hi-C Gene Prioritisation

To assess spatial promoter interactions in the discovery set, we performed a Capture Hi-C Gene Prioritisation (CHIGP) as described in Javierre et al.60 and https://github.com/ollyburren/CHIGP using recommended settings and data sources: 0.1cM recombination blocks, 1KGP EUR reference population, coding markers from the GRCh37 Ensembl assembly and the CHICAGO-generated61 Promoter Capture Hi-C peak matrix data from 17 human primary blood cell types supplied in the original paper. The resulting proteincoding prioritized genes (gene score > 0.5) were used in the downstream network analysis, from cell types “Fetal thymus”, “Total CD4 T cells”, “Activated total CD4 T cells”, “Non-activated total CD4 T cells”, “Naive CD4 T cells”, “Total CD8 T cells”, “Naive CD8 T cells”, “Total B cells”, “Naive B cells”, “Endothelial precursors”, “Macrophages M0”, “Macrophages M1”, “Macrophages M2”, “Monocytes”, and “Neutrophils”.

Gene set overrepresentation analysis of known and replicating novel loci

All high-confidence gene symbols from eQTL and meQTL sources, PCHiC, as well as genes (models extended 110kb upstream, and 40kb downstream) within each r2-based loci definition from known and replicating novel loci were input into the pathway-based set over-representation analysis module of ConsensusPathDB (CPDB) database and tools62 with 229 of 277 gene identifiers translated. In addition, these same symbols were used for Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA; www.ingenuity.com; a curated database of the relationships between genes obtained from published articles, and genetic and expression data repositories) to identify biological pathways common to genes. IPA determines whether the associated genes are significantly enriched in a specific biological function or network by assessing direct interactions. We assigned significance if right-tailed Fisher’s exact test p-value < 0.05.

eQTL/meQTL, PCHiC and locus gene intersections were visualized using the UpSetR package (v1.3.2) 63.

Tissue overrepresentation

To assay the enrichment of variants associated with AR in tissue specific gene expression sets, we utilized the DEPICT enrichment method64, using a p-value threshold of 1e-5, and standard settings.

Enrichment of regulatory regions

To assay the enrichment of variants associated with AR in regions of open chromatin and specific histone marks, we utilized the GWAS Analysis of Regulatory or Functional Information Enrichment with LD correction (GARFIELD v. 1) method65. In essence, GARFIELD performs greedy pruning of GWAS markers (LD r2 > 0.1) and then annotates them based on functional information overlap. Next, it quantifies Fold Enrichment (FE) at various GWAS significance cutoffs and assesses them by permutation testing, while adjusting for minor allele frequency, distance to nearest transcription start site and number of LD proxies (r2 > 0.8). GARFIELD was run with 10,000,000 permutations, and otherwise default settings.

PARF

Population-attributable risk fractions (PARFs) were estimated from B58C, a general-population sample with participant ages 44-45 years also contributing to the discovery stage. The genetic risk score was calculated by applying the pooled per-allele coefficients (ln(OR) values) from the AR discovery set to the number of higher-risk alleles of each of the 41 established (known genome-wide significant and novel replicated loci), one SNP per locus. Because there were no individuals observed with zero higher-risk alleles, the prevalence of sensitization for individuals in the lowest decile of the genetic risk score distribution was used to derive PARF estimates on the assumption that this 10% of the population was unexposed. This method has the advantage that it does not predict beyond the bounds of the data, but its results are conservative. The PARF was then derived (with 95% confidence interval) by expressing the difference between the observed prevalence and the predicted (unexposed) prevalence as a percentage of the observed prevalence. PARFs were estimated using the 41 AR loci in relation to AR, AS and NAR, respectively.

Protein network and drug interactions

In order to analyse protein-protein-drug interaction networks, STRING (V10)66 was used. Protein network data (9606.protein.links.v10.txt.gz) and protein alias data (9606.protein.aliases.v10.txt) files were downloaded from the string db website http://string-db.org/. GWAS hits stratified on ‘all’, ‘blood’ and ‘lung’ were converted to Ensembl protein ids using the protein alias data. The interactors were subsequently identified using the link data at a ‘high confidence cutoff of >0.7’ as described in the STRING FAQ. The interactor Ensembl protein ids were then converted to UniProt gene names and both hits and interactors were then analyzed for interactions with FDA approved drugs using the ChEMBL Database v. 2267 API via Python (v. 2.7.12). Lastly, stratified networks consisting of GWAS hits connected to interactors and drugs connected to both GWAS hits and interactors were visualised using GGraph (v. 1.0.0), iGraph (v. 1.0.1), TidyVerse (v. 1.1.1) under R (v. 3.3.2).

Data availability

Genome-wide results, excluding 23andMe, are available on request through the corresponding author. The full GWAS summary statistics for the 23andMe discovery data set will be made available through 23andMe to qualified researchers under an agreement with 23andMe that protects the privacy of the 23andMe participants. Please contact David Hinds (dhinds@23andme.com) for more information and to apply to access the 23andMe data. A Life Sciences Reporting Summary is available for this paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Detailed acknowledgments and funding details are provided for each contributing study in the Supplementary Note.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

G.S., I.J., and K.S. are affiliated with deCODE genetics/Amgen declare competing financial interests as employees. C.T., D.A.H., J.Y.T., and the 23andMe Research Team are employees of and hold stock and/or stock options in 23andMe, Inc. L.P. has received a fee for participating in a scientific input engagement meeting from Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited, outside of the submitted work.

References

- 1.Greiner AN, Hellings PW, Rotiroti G & Scadding GK Allergic rhinitis. Lancet 378, 2112–2122 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Björkstén B et al. Worldwide time trends for symptoms of rhinitis and conjunctivitis: Phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 19, 110–124 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willemsen G, van Beijsterveldt TCEM, van Baal CGCM, Postma D & Boomsma DI Heritability of self-reported asthma and allergy: a study in adult Dutch twins, siblings and parents. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 11, 132–142 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fagnani C et al. Heritability and shared genetic effects of asthma and hay fever: an Italian study of young twins. Twin Res. Hum. Genet 11, 121–131 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramasamy A et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis of genetic variants associated with allergic rhinitis and grass sensitization and their interaction with birth order. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 128, 996–1005 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinds DA et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis of self-reported allergy identifies shared and allergy-specific susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet 45, 907–911 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bønnelykke K et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies ten loci influencing allergic sensitization. Nat. Genet 45, 902–906 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira MAR et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 11 risk variants associated with the asthma with hay fever phenotype. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 133, 1564–1571 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunyavanich S et al. Integrated genome-wide association, coexpression network, and expression single nucleotide polymorphism analysis identifies novel pathway in allergic rhinitis. BMC Med. Genomics 7, 48 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahn-Schmid B, Pickl WF & Bohle B Interaction of Allergens, Major Histocompatibility Complex Molecules, and T Cell Receptors: A ‘Menage a Trois’ That Opens New Avenues for Therapeutic Intervention in Type I Allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol 156, 27–42 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavalli G et al. MHC class II super-enhancer increases surface expression of HLA-DR and HLA-DQ and affects cytokine production in autoimmune vitiligo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 1363–1368 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi M et al. Autoimmune vitiligo is associated with gain-of-function by a transcriptional regulator that elevates expression of HLA-A*02:01 in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 1357–1362 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puel A, Ziegler SF, Buckley RH & Leonard WJ Defective IL7R expression in T(−)B(+)NK(+) severe combined immunodeficiency. Nat. Genet 20, 394–397 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundmark F et al. Variation in interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) influences risk of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Genet 39, 1108–1113 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori T et al. Lnk/Sh2b3 controls the production and function of dendritic cells and regulates the induction of IFN-γ-producing T cells. J. Immunol 193, 1728–1736 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott LM, Civin CI, Rorth P & Friedman AD A novel temporal expression pattern of three C/EBP family members in differentiating myelomonocytic cells. Blood 80, 1725–1735 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao H, Parkin S, Johnson PF & Schwartz RC C/EBP gamma has a stimulatory role on the IL-6 and IL-8 promoters. J. Biol. Chem 277, 38827–38837 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.León B et al. Regulation of T(H)2 development by CXCR5+ dendritic cells and lymphotoxin-expressing B cells. Nat. Immunol 13, 681–690 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence T The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 1, a001651 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinnakasu R et al. Regulated selection of germinal-center cells into the memory B cell compartment. Nat. Immunol 17, 861–869 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roychoudhuri R et al. BACH2 regulates CD8(+) T cell differentiation by controlling access of AP-1 factors to enhancers. Nat. Immunol 17, 851–860 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothlin CV, Ghosh S, Zuniga EI, Oldstone MBA & Lemke G TAM receptors are pleiotropic inhibitors of the innate immune response. Cell 131, 1124–1136 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan PY et al. The TAM family receptor tyrosine kinase TYRO3 is a negative regulator of type 2 immunity. Science 352, 99–103 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassmeier MD et al. VprBP binds full-length RAG1 and is required for B-cell development and V(D)J recombination fidelity. EMBO J 31, 945–958 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamblet CE, Makowski SL, Tritapoe JM & Pomerantz JL NK Cell Maturation and Cytotoxicity Are Controlled by the Intramembrane Aspartyl Protease SPPL3. J. Immunol 196, 2614–2626 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen JB, Strandbygard DJ, Hartmann R & Justesen J Interaction between the 2’−5’ oligoadenylate synthetase-like protein p59 OASL and the transcriptional repressor methyl CpG-binding protein 1. Eur. J. Biochem 271, 628–636 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halim TYF et al. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity 37, 463–474 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson DM et al. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature 390, 175–179 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira MA et al. Shared genetic origin of asthma, hay fever and eczema elucidates allergic disease biology. Nat. Genet 49, 1752–1757 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearce N, Pekkanen J & Beasley R How much asthma is really attributable to atopy? Thorax 54, 268–272 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohme M, Wickman M, Lennart Nordvall S, Svartengren M & Wahlgren CF Family history and risk of atopic dermatitis in children up to 4 years. Clin. Exp. Allergy 33, 1226–1231 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreiner E et al. Shared genetic variants suggest common pathways in allergy and autoimmune diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bousquet J et al. Important research questions in allergy and related diseases: nonallergic rhinitis: a GA2LEN paper. Allergy 63, 842–853 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moffatt MF et al. Genetic variants regulating ORMDL3 expression contribute to the risk of childhood asthma. Nature 448, 470–473 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paternoster L et al. Multi-ancestry genome-wide association study of 21,000 cases and 95,000 controls identifies new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet 47, 1449–1456 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods section references

- 36.Winkler TW et al. Quality control and conduct of genome-wide association meta-analyses. Nat. Protoc 9, 1192–1212 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mägi R & Morris AP GWAMA: software for genome-wide association meta-analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 288 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segrè AV et al. Common inherited variation in mitochondrial genes is not enriched for associations with type 2 diabetes or related glycemic traits. PLoS Genet 6, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karolchik D et al. The UCSC Table Browser data retrieval tool. Nucleic Acids Res 32, D493–6 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian A et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME & Visscher PM GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet 88, 76–82 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang CC et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, 7 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.UK10K Consortium et al. The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease. Nature 526, 82–90 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium et al. Bayesian refinement of association signals for 14 loci in 3 common diseases. Nat. Genet 44, 1294–1301 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLaren W et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol 17, 122 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng X et al. HIBAG--HLA genotype imputation with attribute bagging. Pharmacogenomics J 14, 192–200 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jia X et al. Imputing amino acid polymorphisms in human leukocyte antigens. PLoS One 8, e64683 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian C et al. Genome-wide association and HLA region fine-mapping studies identify susceptibility loci for multiple common infections. Nat. Commun 8, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berman HM The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 235–242 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vita R et al. The immune epitope database (IEDB) 3.0. Nucleic Acids Res 43, D405–12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sethi DK, Gordo S, Schubert DA & Wucherpfennig KW Crossreactivity of a human autoimmune TCR is dominated by a single TCR loop. Nat. Commun 4, 2623 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rϋckert C et al. Conformational dimorphism of self-peptides and molecular mimicry in a disease-associated HLA-B27 subtype. J. Biol. Chem 281, 2306–2316 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bulik-Sullivan B et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet 47, 1236–1241 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng J et al. LD Hub: a centralized database and web interface to perform LD score regression that maximizes the potential of summary level GWAS data for SNP heritability and genetic correlation analysis. Bioinformatics 33, 272–279 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kettunen J et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple loci influencing human serum metabolite levels. Nat. Genet 44, 269–276 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lucas AO Surveillance of communicable diseases in tropical Africa. Int. J. Epidemiol 5, 39–43 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westra H-J et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat. Genet 45, 1238–1243 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fairfax BP et al. Genetics of gene expression in primary immune cells identifies cell type-specific master regulators and roles of HLA alleles. Nat. Genet 44, 502–510 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicodemus-Johnson J et al. DNA methylation in lung cells is associated with asthma endotypes and genetic risk. JCI Insight 1, e90151 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Javierre BM et al. Lineage-Specific Genome Architecture Links Enhancers and Non-coding Disease Variants to Target Gene Promoters. Cell 167, 1369–1384.e19 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cairns J et al. CHiCAGO: robust detection of DNA looping interactions in Capture Hi-C data. Genome Biol 17, 127 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamburov A et al. ConsensusPathDB: toward a more complete picture of cell biology. Nucleic Acids Res 39, D712–7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Conway JR, Lex A & Gehlenborg N UpSetR: An R Package For The Visualization Of Intersecting Sets And Their Properties (2017). doi: 10.1101/120600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pers TH et al. Biological interpretation of genome-wide association studies using predicted gene functions. Nat. Commun 6, 5890 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.lotchkova V et al. GARFIELD - GWAS Analysis of Regulatory or Functional Information Enrichment with LD correction. bioRxiv 085738 (2016). doi: 10.1101/085738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Szklarczyk D et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res 43, D447–52 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bento AP et al. The ChEMBL bioactivity database: an update. Nucleic Acids Res 42, D1083–90 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Genome-wide results, excluding 23andMe, are available on request through the corresponding author. The full GWAS summary statistics for the 23andMe discovery data set will be made available through 23andMe to qualified researchers under an agreement with 23andMe that protects the privacy of the 23andMe participants. Please contact David Hinds (dhinds@23andme.com) for more information and to apply to access the 23andMe data. A Life Sciences Reporting Summary is available for this paper.