Abstract

Although it is generally accepted that the circadian clock provides a timing signal for the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, mechanistic explanations of this phenomenon remain underexplored. It is known, for example, that circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (clock) mutant mice have severely dampened LH surges, but whether this phenotype derives from a loss of circadian rhythmicity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) or altered circadian function in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons has not been resolved. GnRH neurons can be stimulated to cycle with a circadian period in vitro and disruption of that cycle disturbs secretion of the GnRH decapeptide. We show that both period-2 (PER2) and brain muscle Arnt-like-1 (BMAL1) proteins cycle with a circadian period in the GnRH population in vivo. PER2 and BMAL1 expression both oscillate with a 24-hour period, with PER2 peaking during the night and BMAL1 peaking during the day. The population, however, is not as homogeneous as other oscillatory tissues with only about 50% of the population sharing peak expression levels of BMAL1 at zeitgeber time 4 (ZT4) and PER2 at ZT16. Further, a light pulse that induced a phase delay in the activity rhythm of the GnRH-eGFP mice caused a similar delay in peak expression levels of BMAL1 and PER2. These studies provide direct evidence for a functional circadian clock in native GnRH neurons with a phase that closely follows that of the SCN.

Key Words: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, Circadian rhythms, Suprachiasmatic nucleus, Period (PER) proteins, Period-2 proteins, Brain muscle Arnt-like 1

Introduction

Coordination of the precise molecular rhythms that drive cyclic physiology and behavior to coordinate with the 24-hour period of the solar day is elemental to life on this planet. The complex transcriptional-translational feedback loops that comprise these molecular rhythms, originally discovered primarily in Drosophila, are conserved in mammalian species, including humans [1,2,3]. Very briefly, brain muscle Arnt-like 1 (BMAL1) binds circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK) to form a heterodimeric transcription factor that drives the expression of the negative elements of the feedback loop, the Cryptocrome (CRY) and Period (PER) proteins. CRY and PER proteins then also dimerize and inhibit BMAL1/CLOCK function, thereby limiting their own transcription. One positive element (BMAL1) and both negative elements (PER and CRY proteins) of the molecular clock oscillate with a 24-hour period; positive and negative arms are 12 h out of phase with one another. This underlying feedback loop has a tissue-specific phase and differentially drives the expression of thousands of transcripts throughout the body. Although it is generally accepted that the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the anterior hypothalamus maintains appropriate phase relationships of the molecular clock both within and among the differing tissues, many tissues maintain rhythmicity for weeks after being removed from the animal and maintained in culture [4]. The precise manner in which the SCN exerts its influence on peripheral systems is likely multifarious, is at least partially tissue-specific and is in many cases currently unknown. Studies that focus on regulation of circadian control in individual tissues will be instrumental in unraveling the numerous emergent physiological processes that feature time-dependent components.

The SCN influences female reproduction by regulating timing of the mid-cycle luteinizing hormone (LH) surge [5,6,7,8,9]. A successful LH surge requires that a precisely timed cue of neuronal origin occurs in the presence of a permissive gonadal hormone milieu to elicit a bolus release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) into the hypophysial portal circulation, thereby stimulating the gonadotrophs of the anterior pituitary [10]. SCN-lesioned animals do not produce an LH surge, whereas ovariectomized animals treated with chronic high levels of estrogen produce a daily LH surge [7,8]. Further, direct projections from the SCN lie in close apposition to GnRH neurons [11,12,13]. The body of work in this field cumulatively implies that the SCN influences reproductive cycles by acting directly on the GnRH neurons or indirectly through innervations of the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Disclosure of SCN-dependent mechanisms that impart this timing information to the GnRH neurons is fundamental to the understanding of mammalian reproduction.

The number and anatomical distribution of GnRH neurons complicate the study of GnRH neuronal function in vivo. Only about 800–1,200 neurons express the GnRH decapeptide in the adult mouse [20]. These neurons are spread diffusely in a continuum from the medial septum (MS) ultimately terminating on both sides of the third ventricle with the bulk of the cell bodies lying just rostral to the third ventricle [21,22]. Difficulty in obtaining pure populations of native GnRH neurons has necessitated that mechanistic studies be performed in cell lines. GT1–7 cells, generated by introducing a 2.3-kb fragment of the rat GnRH gene 5′-flanking region linked to the coding region of the SV40 T-antigen oncogene into mouse embryos, express core circadian clock transcripts with a 24-hour period [23]. GnRH pulsatility is disrupted in GT1–7 cells transiently transfected with a dominant negative CLOCK protein, which blocks circadian rhythmicity [24]. Collectively, these data suggest that a functional circadian clock is required for the function of GnRH neurons in vitro.

The current study demonstrates clock-regulated changes in core clock components in GnRH neurons in vivo. Core clock proteins oscillate in native GnRH neurons. Light pulses that alter the phase of the SCN cause a concomitant shift in the phase of the GnRH population. Thus, timing of LH surge may be partially controlled by the circadian cycling of mRNAs and proteins in the GnRH population as a whole, and the phase of this oscillation closely follows that of the SCN.

Methods

Animals and Circadian Time

GnRH-eGFP (from Dr. Suzanne Moenter, University of Virginia) mice were used for all experiments. The GnRH-eGFP transgenic mice use the mouse GnRH promoter to drive expression of 600 base pairs of the B intron of rabbit β-globin as a splice donor/acceptor, linked to the coding sequence for enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the polyadenylation signal from human growth hormone [25]. This transgene labels about 85% of cells that stain positive for GnRH with eGFP. Animals were 2–4 months old. Only female mice were examined. For certain experiments, estrous cycles were determined by analysis of vaginal secretions. Only animals with 2 consecutive 4-day estrous cycles were used for these experiments. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Mice were housed under a strict lighting schedule with 12 h lights on followed by 12 h lights off, except where noted. Under these lighting conditions, denoted as LD, zeitgeber time 0 (ZT0) is designated as the time that the lights come on in the colony. Lights off occurs at ZT12. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Wheel-Running Activity

GnRH-eGFP mice were housed individually in 30 × 19 × 12.5 cm cages (Ancare, Bellmore, N.Y., USA) and provided with 4.5-inch diameter activity wheels. Wheel revolutions were recorded upon the circuit closure of hermetically sealed reed switch (Hermetic Switch, Inc., Chickasha, Okla., USA), by a neodymium magnet (Magnetic Energies, Inc.; San Antonio, Tex., USA) attached to each wheel [26,27]. After entrainment to a 12L:12D schedule for at least 14 days, animals were exposed to a pulse of light (500 lux) for 30 min at ZT16. After the light pulse, animals remained in constant darkness (DD) for the duration of the experiment. For data analysis, wheel-running counts in 1-min bins were recalculated into 10-min bins by ClockLab (Actimetrics, Evanston, Ill., USA). Tau was calculated from activity onset of the last 10 days in DD. Activity onset on the third day in DD was used to calculate the magnitude of the phase delay.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice (n = 4–6 per time point) were anesthetized with 0.3 ml sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/ml) and perfused intracardially with 20 ml ice-cold 0.1 M PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (50 ml). Brains were postfixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde, transferred to 0.1 M PBS with 20% sucrose and maintained at 4°C until sectioning. 20-µm coronal sections were prepared on a cryostat and a 1:3 series was collected starting from the MS and continuing caudally to the retrochiasmatic area. After blocking in normal goat serum, slides were incubated overnight in primary antibody (rabbit anti-mouse ARNTL, 1:200, Oncogene Research Products; rabbit anti-mouse PER2, 1:200, Alpha Diagnostics International), washed and incubated with fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h (goat anti-rabbit IgG, rhodamine conjugated, 1:100, Pierce). Slides were stained with Sudan black to reduce background fluorescence. Control experiments included omission of primary antibody, and primary antibody preabsorbed with the peptide against which it was generated. Slides were imaged by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert 200). Fluorescence intensity was quantitated using Axiovision 4.1 software (Zeiss). For quantitation, 4–5 sections from each region – MS, preoptic area (POA), anterior hypothalamic area (AHA), and the lateral hypothalamus (LHA) – were observed at 40× magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted fluorescence microscope. GnRH neurons were first identified and marked under GFP fluorescence. Rhodamine fluorescence intensity within the marked area (GFP-identified GnRH neurons) was then determined. Background for rhodamine was determined from an area of each section of similar size that did not contain any GFP- or rhodamine-positive neurons. For further analysis, relative intensity of rhodamine staining from each neuron was divided into 3 groups: not detectable, which was defined as equivalent to background, low levels, which was defined as ≥1–2× background (low intensity), and high levels, which was defined as >2–3× background (high intensity).

Statistical Analysis

For immunofluorescence studies, data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA. Tukey's post-hoc analysis was used to determine statistical significance between data points. For wheel running activity, Student's t test was used to assess differences between control and light-pulse groups. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Oscillations of Clock Components in Native GnRH Neurons

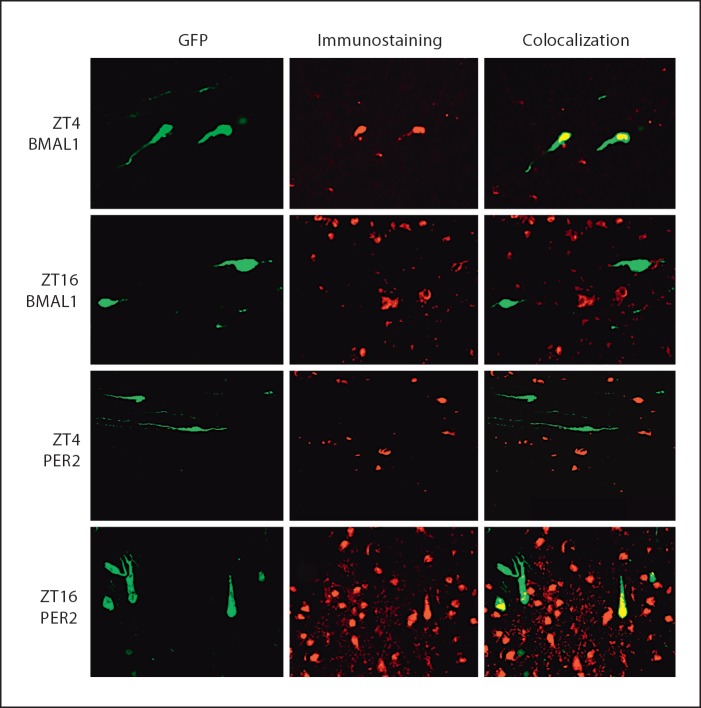

Despite compelling circumstantial evidence for an intact circadian clock in GnRH neurons, oscillations of core components of the molecular clockworks have yet to be identified in GnRH neurons in vivo. Thus, we performed fluorescence immunohistochemistry for PER2 and BMAL1 on coronal sections of GnRH-eGFP transgenic mouse brains from the medial septum to the retrochiasmatic area. No staining was observed in control samples where primary antibody was omitted or when primary antibodies were preincubated with the peptide to which they were generated (data not shown). BMAL1 and PER2 proteins were colocalized with GFP in a time-of-day dependent manner. BMAL1 colocalization was generally high at ZT4 and low at ZT16, whereas PER2 colocalization was high at ZT16 and low at ZT4 (fig. 1). Analysis of immunostaining at 4-hour intervals over a 24-hour period revealed clear diurnal rhythmicity for both BMAL1 and PER2 antiphase to one another (fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Representative immunohistochemical staining for BMAL1 and PER2 in 20-µm sections of POA from GnRH-eGFP mice. Left column is GFP fluorescent identification of GnRH neurons characteristic of the GnRH-eGFP mice. Middle column is rhodamine fluorescence indicative of immunohistochemical staining. Right column is colocalization of rhodamine and GFP in GnRH neurons. Top row is BMAL1 staining at ZT4. BMAL1 is increased at ZT4 and colocalizes with GFP. Second row is BMAL1 staining. BMAL1 staining is observed at ZT16; however, there is little colocalization with GFP at this time. Third row is PER2 staining at ZT4. PER2 levels are low at this time and there is little colocalization with GFP. Bottom row is PER2 staining at ZT16. PER2 immunoreactivity is increased at this time and there is substantial colocalization with GFP. Bar = 30 µm.

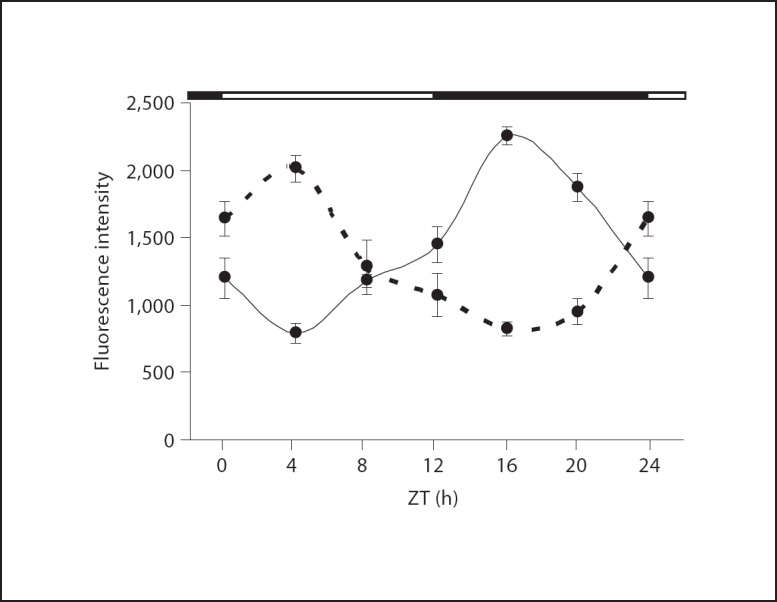

Fig. 2.

Quantitation of rhodamine fluorescence intensity for immunostaining of BMAL1 (– – –) and PER2 (––––) in GFP-labeled GnRH neurons. PER2 fluorescence intensity was significantly increased in GFP-labeled GnRH neurons during the night (ZT16 and ZT20) compared to the day (ZT4 and ZT8). BMAL1 fluorescence intensity was significantly increased during the day (ZT0 and ZT4) compared to night (ZT16 and ZT20). * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to the lowest expression time point (ZT4 for PER2 and ZT16 for BMAL1) as determined by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc analysis. Black bar along top of graph indicates time of lights off. Each data point is the mean ± SEM for 4–6 separate animals. n = 4 for ZT0, 8, 12 and 20; n = 6 for ZT4 and 16.

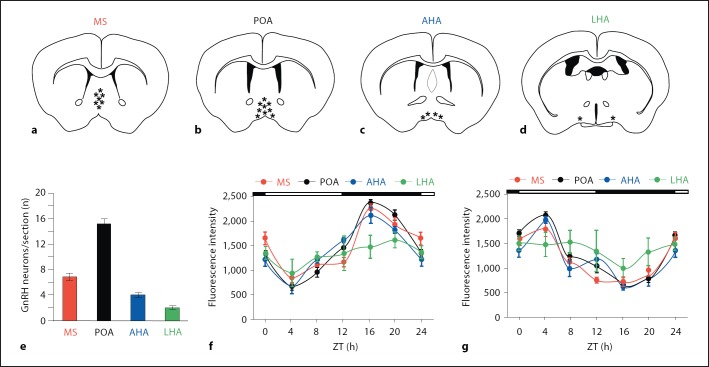

Further analysis of these data was performed after separating the GnRH neurons into 4 subgroups based on anatomical location (fig. 3a–d). Four to five sections per animal were obtained for each anatomical group. The number of neurons per section is shown in figure 3e. Table 1 provides more information on the total number of neurons analyzed. GFP-labeled GnRH neurons were most concentrated in the POA; there were 16 ± 1.2 (n = 28 total animals) per section in the POA. There were fewer neurons in the MS (7 ± 0.7 per section) and AHA (4 ± 0.4 per section). The LHA in the region near the SCN contained 2 ± 0.2 GFP-labeled neurons per section. Rhythmic expression of both PER2 (fig. 3f) and BMAL1 (fig. 3g) was observed in MS, POA and AHA. However, there was no significant diurnal variation in either PER2 or BMAL1 in the LHA (fig. 3f–g).

Fig. 3.

Rhodamine fluorescence intensity for BMAL1 and PER2 in GFP-labeled GnRH neurons according to anatomical location. Data from the same animals as in figure 2 were reanalyzed after separation into subgroups of GFP-positive neurons based upon anatomical location; 4–5 coronal sections (20 µm) per anatomical location were analyzed in each individual animal. a–d Relative distribution of GFP-positive neurons based on anatomical location. e Bar graph depicting the number of GnRH neurons per section in each anatomical location (number of neurons ± SEM). f Quantitation of PER2 immunofluorescence by region; n = 4 animals at ZT0, 8, 12 and 20; n = 6 animals at ZT4 and 16. PER2 staining is significantly elevated at ZT24/0 (p < 0.05), ZT12 (p < 0.01), ZT16 (p < 0.001) and ZT20 (p < 0.01) in MS, POA and LHA compared to ZT4. g Quantitation of BMAL1 immunofluorescence by region; n = 4 animals at ZT 0, 8, 12 and 20; n = 6 animals at ZT4 and 16. BMAL1 staining is significantly elevated at ZT24/0 (p < 0.05) and ZT4 (p < 0.001) compared to ZT16 in MS, POA and AHA. BMAL1 is also significantly elevated at ZT8 (p < 0.05) in POA and ZT12 (p < 0.05) in AHA and MS compared to ZT16.

Table 1.

| Time | MS |

POA |

AHA |

LHA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sections | cells | sections | cells | sections | cells | sections | cells | |

| ZT0 (4) | 17 | 124 | 16 | 112 | 17 | 69 | 18 | 36 |

| ZT4 (6) | 22 | 149 | 25 | 391 | 26 | 106 | 26 | 58 |

| ZT8 (4) | 16 | 102 | 18 | 270 | 16 | 67 | 20 | 49 |

| ZT12 (4) | 18 | 108 | 16 | 251 | 15 | 62 | 18 | 34 |

| ZT16 (6) | 24 | 161 | 26 | 166 | 28 | 107 | 28 | 52 |

| ZT20 (4) | 17 | 115 | 16 | 262 | 19 | 78 | 18 | 36 |

| ZT24 (4) | 15 | 109 | 18 | 281 | 17 | 66 | 18 | 33 |

The number of animals is shown in parentheses. ‘Sections’ refers to the number of total sections; ‘Cells’ refers to the total number of cells.

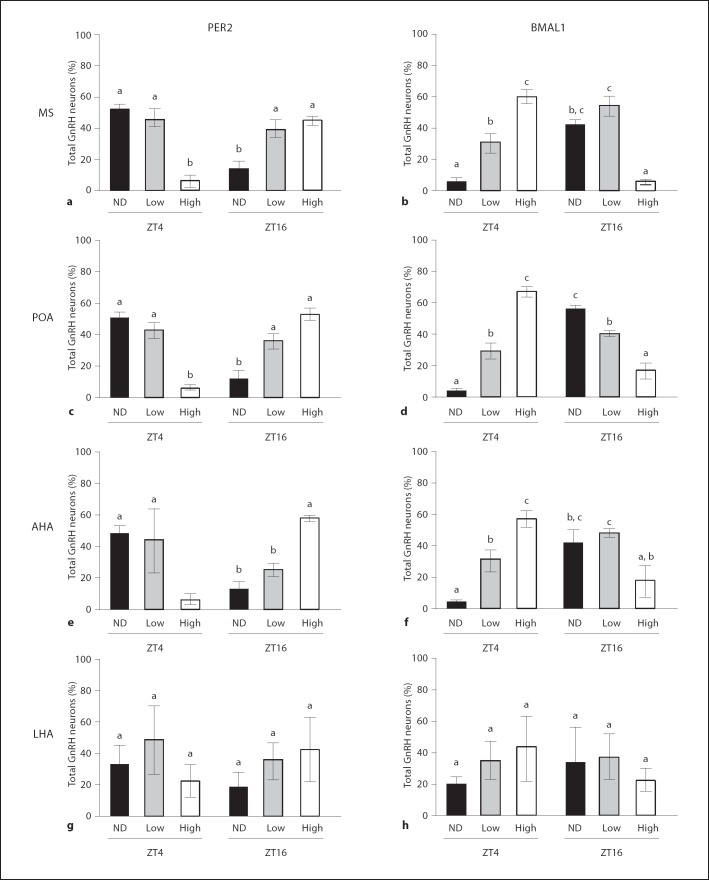

At the time of peak expression (ZT4 for BMAL1 and ZT16 for PER2), both BMAL1 and PER2 were detectable in greater than 90% of all GFP-labeled GnRH neurons. In contrast, BMAL1 was undetectable in 46% of GnRH neurons and PER2 was undetectable in 41% of GnRH neurons at times when overall fluorescence intensity was minimal. BMAL1 and PER2 were present in certain GnRH neurons, however, regardless of time-of-day (fig. 4). High levels of immunofluorescence, defined as ≥2× background, were observed at ZT4 for PER2 and at ZT16 for BMAL1. Both BMAL1 and PER2 were generally increased throughout the hypothalamus at ZT4 and ZT16, respectively. This effect was more pronounced with PER2. When neurons were analyzed by region, we observed that about 35–45% of all GFP-labeled GnRH neurons demonstrated detectable, but low levels of immunofluorescence for BMAL1 and for PER2, defined at >1–2× background, regardless of time of day. In the LHA, there was a fairly equal distribution of the percentage of GnRH neurons with low, high or undetectable staining for BMAL1 and PER2 and there was no change in this distribution between ZT4 and ZT16 (fig. 4g–h). In MS, POA and AHA, the percentage of GnRH neurons with undetectable PER2 immunofluorescence was high at ZT4 and significantly lower at ZT16; the percentage of neurons demonstrating high levels of PER2 immunofluorescence was substantially decreased at ZT4 compared to ZT16, and the percentage of neurons with low-level PER2 staining was not different between ZT4 and ZT16 (fig. 5a, c, e). The results for BMAL1 in the MS, POA and AHA were similar, albeit the times of elevated immunofluorescence were reversed (fig. 5b, d, f). The percentage of GnRH neurons with undetectable levels of BMAL1 was decreased at ZT4 compared to ZT16, whereas the percentage of GFP-labeled neurons with high BMAL1 immunofluorescence was increased at ZT4 compared to ZT16. Unlike our observations for PER2, however, the percentage of neurons with low levels of BMAL1 staining was increased in MS, POA and AHA at ZT16 compared to ZT4. The observed oscillatory behavior of these molecular clock components in the population of native GnRH neurons, particularly the out-of-phase relationship in peak expression levels of these proteins, is consistent with the presence of functional clockworks in a significant number of these cells.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of immunofluorescence for PER2 and BMAL1 in GFP-positive GnRH neurons separated according to region. See table 1 for a description of the total number of neurons analyzed. Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05). ND = Not detectable above background; Low = fluorescence intensity >1–2× background; High = fluorescence intensity >2× background. a, b PER2 and BMAL1 in MS. c, d PER2 and BMAL1 in POA. e, f PER2 and BMAL1 in AHA. g, h PER2 and BMAL1 in LHA.

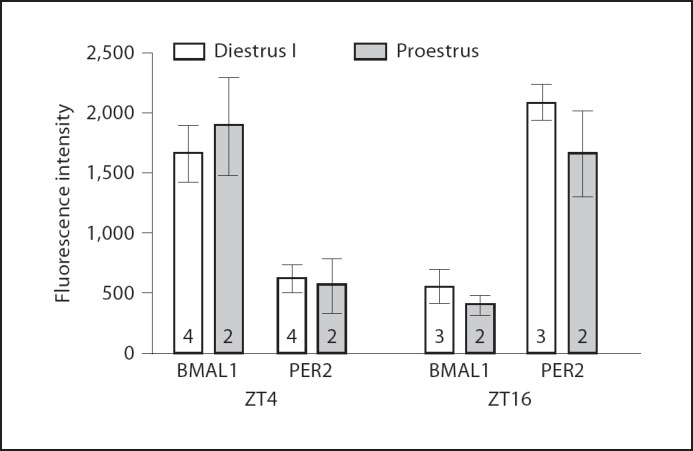

Fig. 5.

Immunofluorescence detection of PER2 and BMAL1 at ZT4 and ZT16 during proestrus and diestrus I. Peak expression of BMAL1 and PER2 is not changed at different times during the estrus cycle. Data are mean ± SEM of fluorescence intensities from GFP positive GnRH neurons in MS, POA, AHA and LH. Number of animals is indicated on the bar. The total number of neurons analyzed is as follows: ZT4 diestrus 1, PER2 = 124; BMAL1 = 118; ZT4 proestrus, PER2 = 64; BMAL1 = 61; ZT16 diestrus I, PER2 = 91; BMAL1 = 96; ZT16 proestrus PER2 = 59; BMAL1 = 55.

Effects of Estrous Cycle Phase on Peak Expression of BMAL1 and PER2 in GnRH Neurons

We examined BMAL1 and PER2 immunofluorescence in GnRH neurons on 2 days of the estrous cycle (fig. 5). Peak expression of PER2 and BMAL1 were not different on the day of proestrus compared to diestrus I. PER2 levels were high at ZT16 and low at ZT4; BMAL1 levels were elevated at ZT4 and low at ZT16.

Light-Induced Phase Resetting of the Circadian Clock Alters BMAL1 and PER2 in Native GnRH Neurons

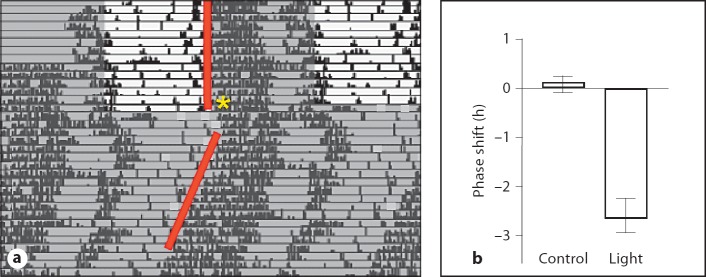

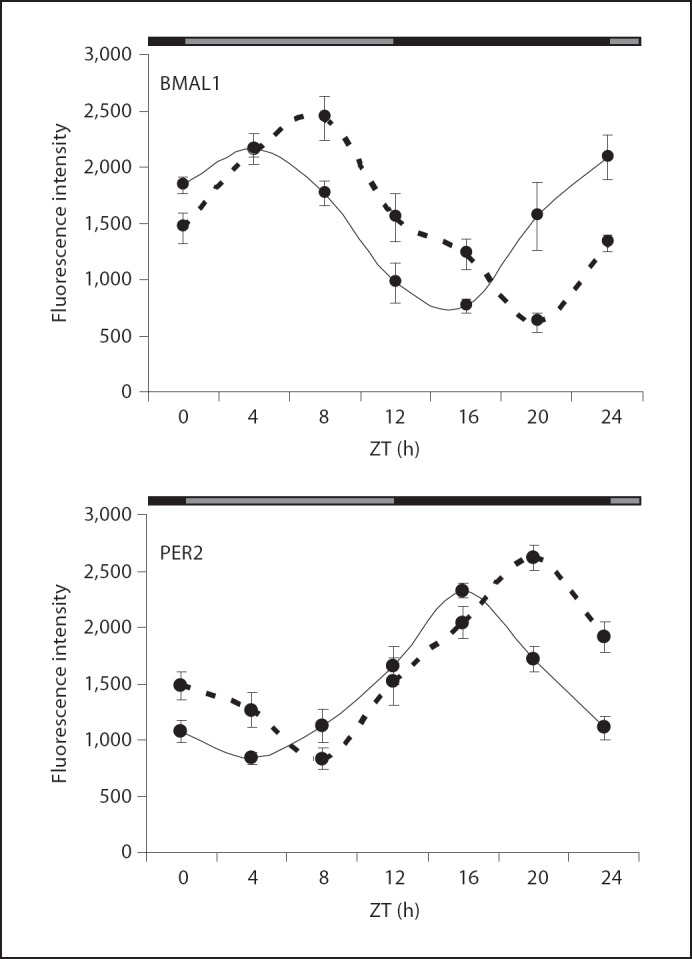

To determine whether the oscillations in the GnRH neuronal population change in response to a stimulus that resets the phase of the SCN rhythm, we examined BMAL1 and PER2 after phase resetting of the clock by a light pulse. Cycling female GnRH-eGFP mice displayed normal circadian rhythms consistent with the c57bl/6 strain and readily entrained to a light/dark cycle (fig. 6). Periodicity of the endogenous rhythm under constant conditions was 23.84 ±0.13 h (n = 10). Estrous-cycle-dependent alterations in the activity pattern were also apparent from the scalloping of the behavioral offsets under constant darkness on the actograms (fig. 6). After entrainment to a 12:12 LD cycle for 2 weeks, cycling females were exposed to a light pulse at ZT16, which induced a 2.64 ± 0.45 h (n = 10) phase delay in the activity rhythm (p <0.01, Student's t test). Animals remained in constant darkness after the light pulse and starting at 48 h after lights off, animals were sacrificed at 4-hour intervals over a 24-hour period to examine PER2 and BMAL1 levels in GnRH neurons. Colocalization of both BMAL1 and PER2 with GFP in GnRH neurons was determined. Both BMAL1 and PER2 expression was altered in phase-shifted mice. In both cases, peak expression values were delayed compared to controls (fig. 7). BMAL1 expression peaked in GFP-positive cells at ZT8 after light treatment; PER2 peaked at ZT20 after light treatment.

Fig. 6.

Light-induced phase shifts in GnRH-eGFP mice. a Representative actogram of wheel-running activity. Mice were entrained in 12L:12D schedule. On the last day in LD, animals were given a 30-min pulse of light (500 lux) at ZT16 (*) and then released into constant darkness. Data are double-plotted for easier visualization of the phase shifts. Phase shifts were calculated from the time of onset of wheel-running activity on the 3rd day in constant darkness. Control animals were placed into constant darkness without a light pulse. b Phase shift after light exposure at ZT16. n = 10, ** p <0.01 by t test.

Fig. 7.

Quantitation of rhodamine fluorescence intensity for immunostaining of BMAL1 and PER2 in GFP-labeled GnRH neurons after 48 h in constant darkness with (– – –) or without (––––) a light pulse at ZT16 on the last day in LD. BMAL1 fluorescence intensity in control animals was significantly increased during the day (ZT0 and ZT4) compared to night (ZT16 and ZT20). PER2 (solid line) fluorescence intensity in control animals was significantly increased in GFP-labeled GnRH neurons during the night (ZT 16 and ZT 20) compared to the day (ZT4 and ZT8). Peak expression was shifted by 4 h after the light pulse. Black/gray bar along top of graph indicates subjective night and subjective day, respectively. Each data point is the mean ± SEM for 4 separate animals. The distribution of GnRH neurons per section was similar to that shown in figure 3e.

Discussion

These studies establish that the core clock proteins PER2 and BMAL1 cycle with a near 24-hour period in the GnRH neurons of intact adult female mice and that the timing of peak expression does not change over the course of the estrous cycle. Previous studies in rodents have shown that activities that alter the timing of wheel running behavior concomitantly alter the timing of the LH surge [6,28]. It is also well established that rhythmic expression of clock transcripts can be induced in GT1–7 cells, and transfection of this cell line with a dominant negative CLOCK disrupts GnRH secretion [24]. Nevertheless, studies on aged, PER2-luciferase transgenic rats determined that it is possible to induce circadian expression of luciferase with in vitro forskolin treatment in tissues that were not cycling when first removed from the animal [4]. Thus, GnRH neurons must be observed to oscillate with a 24-hour clock expression in vivo to confirm the physiological relevance of a functional clock.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the oscillation of clock proteins in native GnRH neurons in detail. Interestingly, about 50% of GFP-positive GnRH neurons in this study showed a 3-fold or greater induction of PER2 and BMAL1 at their peak time of expression (fig. 4). A small percentage of GnRH neurons expressed high levels of PER2 and BMAL1 during the time of minimal expression for the whole population. It is important to note that we did not follow cells in real time. Each of our data points represents only a snapshot of the entire population at each time point. Although caution is essential when evaluating our population data in comparison to studies that track rhythms in individual cells, 90% of neurons in cultured SCN slices express PER2 with a circadian period that is in phase with one another [29]. Based on our data, it is not possible to determine whether there are some GnRH neurons that do not oscillate or whether there are certain individual neurons that oscillate with a phase that is out of synchrony with the population.

Numerous studies have revealed a substantial degree of heterogeneity in this population. Patch clamp recording of GnRH containing slices found four distinct firing patterns among GnRH neurons [30]. Only 50–70% of GnRH neurons send projections to the external zone of the median eminence of the hypothalamus while 10% of all connections on GnRH neurons are from GnRH afferents [31,32,33,34,35]. Further complicating the picture, projections from as many as 90% of GnRH neurons target regions outside of the blood-brain barrier. Receptor expression also varies among the population [33], with only 19% of the neurons of postpubertal female rats expressing NMDA-R1 receptor, for example [36]. To determine whether certain populations of GnRH neurons might be oscillating out of phase with others, we divided the GnRH neurons into anatomical subpopulations and examined immunfluorescence for BMAL1 and PER2. We found that GnRH neurons in the MS, POA and AHA showed similar phase characteristics, with peak expression of BMAL1 at ZT4 and PER2 at ZT16. Only the GnRH neurons located most caudally in the LHA did not show any oscillation. Whether this represents a distinct difference in the LHA compared to other brain regions, or whether this reflects the fact that many fewer neurons were analyzed in the LHA (2 per section compared to 16 per section for POA) remains to be determined. Careful examination of these data reveals that MS, POA and AHA show similar patterns of expression. At each time of day explored, we could find GnRH neurons with high levels of clock protein and undetectable levels of CLOCK proteins. It is also noteworthy that increased immunofluorescence was observed throughout the hypothalamus for BMAL1 at ZT4 and for PER2 at ZT16 although the effect was more pronounced for PER2 (fig. 1). These data clearly indicate that neurons in the MS, POA and AHA show similar circadian characteristics and that all the neurons within an individual region are not likely synchronized with each other. The meaning of this is not clear from our data. It is possible that the anatomical divisions that we imposed on the data were flawed. It may be more likely that neurons that share physiological similarities may also cycle together. The answers to these questions await future studies that might be designed to follow individual neurons of this population in real time.

The overall influence of the SCN on GnRH neurons is highly intricate and not completely understood. Studies on clock mutant mice demonstrated that modest LH surges could be induced by injection of vasopressin into the third ventricle [37], and morphological changes in the astrocytes that lie in direct apposition to GnRH neurons occur with a circadian period [38]. It seems likely that input from the SCN stimulates glia to pull away and expose GnRH neurons prior to the large increase in GnRH peptide release associated with the subsequent LH surge. Hamsters that undergo SCN ‘splitting’ have two smaller LH surges 12 h out of phase with one another [39,40]. In those studies, confocal images showing cFOS activation in GnRH neurons with direct connections from the SCN found only half of the GnRH population was activated at either time point. It therefore seems likely that timing of LH release is coordinated by multiple timing mechanisms originating in the SCN. The SCN could be releasing a direct cue that stimulates GnRH neurons to initiate release of the GnRH decapeptide as well as sending other signals that maintain the appropriate phase among members of the GnRH population while simultaneously regulating surrounding structures that also impinge upon the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Establishing which molecular entities are cycling in a circadian manner in GnRH neurons throughout the day, especially on the day of the LH surge, will be required for appropriate interpretation of the overall impact internal circadian regulation has on GnRH neuronal behavior.

In mammals it is well established that circadian oscillations in peripheral tissues are heavily dependent on SCN input in order to maintain their functional rhythmicity. Overall, however, implementation of molecular rhythmicity is divergent among the tissues. 10% of all mRNA transcripts oscillate in a circadian manner in liver, heart, and lung tissues, but less than 50 of these oscillating mRNA's are common among all tissues [1,41,42]. It is plausible that the SCN at least partially imparts its effect on timing of the preovulatory LH surge by maintaining the appropriate circadian phase of the GnRH neurons. Thus we examined whether treatments that are known to alter the phase of the SCN, onset of locomotor behavior, and LH surge timing also altered the phase of clock protein expression in intact GnRH neurons. Finding that the phase of PER2 and BMAL1 was altered proportionally to shifts in the phase of the SCN (fig. 6, 7) within 48 h of a light pulse demonstrates that the phase of the GnRH neurons follows resetting of the phase of the SCN very closely. Although it has been shown that altering the LD cycle in per1-luc rats causes changes in the phase of the luciferase intensity in skeletal muscle, lung, and liver tissues, the time and amplitude of those changes were tissue specific [43]. Skeletal muscle and lung samples take 6 days to reestablish an appropriate phase relationship to the SCN following a LD cycle. At 24 h after the phase shift, rhythms in skeletal muscle and lung are still in the process of shifting. In those same studies, the liver was still out of synchrony with the SCN 6 days after the phase resetting stimulus [43]. The liver clock resets more quickly in response to alterations in feeding through a process that is independent of the SCN [44]. The studies presented here do not establish that direct input from the SCN is driving these changes, as it is possible that the entrainment of the GnRH neurons is dependent upon an intermediate source, such as the kisspeptin 1 expressing neurons in the AVPV. It is clear, however, that in vivoGnRH neurons maintain a tight circadian phase relationship with the SCN. This is an important observation as GnRH neurons receive vast numbers of inputs and therefore could theoretically demonstrate a rhythm that is independent of the SCN. As the circadian phase of the GnRH neurons is tightly correlated with that of the SCN, it is highly likely that the SCN is the source of this phase and that maintenance of this rhythm is important for proper cellular function as has been demonstrated in vitro[24].

The nature of the signal that imparts circadian control on the GnRH neuronal population remains a mystery. Peptide neurotransmitters, such as vasoactive intestinal peptide and arginine vasopressin, of SCN origin, are thought to be important. Recently, there has been considerable interest in the ability of kisspeptin-expressing neurons in the AVPV to induce release of GnRH [45]. Future studies that examined whether loss of circadian phase in the GnRH neuronal population might alter the potency of these secretagogues would be of considerable interest. Our studies demonstrate that at least a subset of GnRH neurons are indeed cycling in phase with each other, and therefore imply that examination of the circadian phase of many of the neuronal pathways that descend upon the GnRH neurons might reveal another aspect of the elaborate manner by which precise timing of the mid-cycle LH surge is orchestrated.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mia Layne and Elisa Salvo for assistance with the immunofluorescence studies, and Chris Zugates for a critical review of the manuscript. Supported by Illinois Governor's Venture Technology Fund (S.A.T.) and the Billie Field Memorial Predoctoral Fellowship (J.R.H.).

References

- 1.Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Mammalian circadian biology: elucidating genome-wide levels of temporal organization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5:407–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.175925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlap JC. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell. 1999;96:271–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young MW, Kay SA. Time zones: a comparative genetics of circadian clocks. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:702–715. doi: 10.1038/35088576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, Lowrey PL, Shimomura K, Ko CH, Buhr ED, Siepka SM, Hong HK, Oh WJ, Yoo OJ, Menaker M, Takahashi JS. Period2: luciferase real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5339–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everett JW, Sawyer CH. A 24-hour periodicity in the ‘LH-release apparatus’ of female rats, disclosed by barbiturate sedation. Endocrinology. 1950;47:198–218. doi: 10.1210/endo-47-3-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinet L, Mondain-Monval M, Seasonal reproduction and photoperiodism . Reproduction in Mammals and Man. In: Thibault C, Levasseur MC, Hunter RHF, editors. Paris, Ellipses. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrahám IM, Han SK, Todman MG, Korach KS, Herbison AE. Estrogen receptor β mediates rapid estrogen actions on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5771–5777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiegand SJ, Terasawa E. Discrete lesions reveal functional heterogeneity of suprachiasmatic structures in regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the female rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1982;34:395–404. doi: 10.1159/000123335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legan SJ, Karsch FJ. A daily signal for the LH surge in the rat. Endocrinology. 1975;96:57–62. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chappell PE. Clocks and the black box: circadian influences on gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:119–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Beek EM, Horvath TL, Wiegant VM, Van den Hurk R, Buijs RM. Evidence for a direct neuronal pathway from the suprachiasmatic nucleus to the gonadotropin-releasing hormone system: combined tracing and light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical studies. J Comp Neurol. 1997;384:569–579. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970811)384:4<569::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watts AG, Swanson LW, Sanchez-Watts G. Efferent projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus: I. Studies using anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;258:204–229. doi: 10.1002/cne.902580204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de la Iglesia HO, Blaustein JD, Bittman EL. The suprachiasmatic area in the female hamster projects to neurons containing estrogen receptors and GnRH. Neuroreport. 1995;6:1715–1722. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199509000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vries GJ, al-Shamma HA. Sex differences in hormonal responses of vasopressin pathways in the rat brain. J Neurobiol. 1990;21:686–693. doi: 10.1002/neu.480210503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoorneman EM, Buijs RM. Vasopressin fiber pathways in the rat brain following suprachiasmatic nucleus lesioning. Brain Res. 1982;243:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leak RK, Moore RY. Topographic organization of suprachiasmatic nucleus projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2001;433:312–334. doi: 10.1002/cne.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terasawa E, Wiegand SJ, Bridson WE. A role for medial preoptic nucleus on afternoon of proestrus in female rats. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:E533–E539. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1980.238.6.E533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson RE, Jr, Langub MC, Jr, Engle MG, Maley BE. Estrogen-receptive neurons in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus are synaptic targets of the suprachiasmatic nucleus and peri-suprachiasmatic region. Brain Res. 1995;689:254–264. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiegand SJ, Terasawa E, Bridson WE. Persistent estrus and blockade of progesterone-induced LH release follows lesions which do not damage the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Endocrinology. 1978;102:1645–1648. doi: 10.1210/endo-102-5-1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gore AC, Roberts JL. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene expression in vivo and in vitro. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1997;18:209–245. doi: 10.1006/frne.1996.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry J. Immunohistochemistry of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-producing neurons of the vertebrates. Int Rev Cytol. 1979;60:179–221. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King JC, Anthony EL. LHRH neurons and their projections in humans and other mammals: Species comparisons. Peptides. 1984;5((suppl 1)):195–207. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(84)90277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mellon PL, Windle JJ, Goldsmith PC, Padula CA, Roberts JL, Weiner RI. Immortalization of hypothalamic GnRH neurons by genetically targeted tumorigenesis. Neuron. 1990;5:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90028-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chappell PE, White RS, Mellon PL. Circadian gene expression regulates pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretory patterns in the hypothalamic GnRH-secreting GT1–7 cell line. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11202–11213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11202.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suter KJ, Song WJ, Sampson TL, Waurin JP, Saunders JT, Dudek FE, Moenter SM. Genetic targeting of green fluorescent protein to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: Characterization of whole-cell electrophysiological properties and morphology. Endocrinology. 2000;141:412–419. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tischkau SA, Weber ET, Abbott SM, Mitchell JW, Gillette MU. Circadian clock-controlled regulation of cGMP-protein kinase G in the nocturnal domain. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7543–7550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07543.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukai M, Lin TM, Peterson RE, Cooke PS, Tischkau SA. Behavioral rhythmicity of mice lacking AHR and attenuation of light-induced phase shift by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23:200–210. doi: 10.1177/0748730408316022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turek FW. Biological rhythms in reproductive processes. Horm Res. 1992;37((suppl)3):93–98. doi: 10.1159/000182408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes AT, Guilding C, Lennox L, Samuels RE, McMahon DG, Piggins HD. Live imaging of altered period1 expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of Vipr2–/– mice. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1646–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sim JA, Skynner MJ, Herbison AE. Heterogeneity in the basic membrane properties of postnatal gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1067–1075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-01067.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman AJ, Jhamandas J, Renaud LP. Localization of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) neurons that project to the median eminence. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2312–2319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merchenthaler I, Setalo G, Csontos C, Petrusz P, Flerko B, Negro-Vilar A. Combined retrograde tracing and immunocytochemical identification of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone- and somatostatin-containing neurons projecting to the median eminence of the rat. Endocrinology. 1989;125:2812–2821. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-6-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Witkin JW. Access of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons to the vasculature in the rat. Neuroscience. 1990;37:501–506. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thind KK, Boggan JE, Goldsmith PC. Interactions between vasopressin- and gonadotropin-releasing-hormone-containing neuroendocrine neurons in the monkey supraoptic nucleus. Neuroendocrinology. 1991;53:287–297. doi: 10.1159/000125731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldsmith PC, Boggan JE, Thind KK. Estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in neuroendocrine and related neurons of the pubertal female monkey hypothalamus. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;65:325–334. doi: 10.1159/000127191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gore AC, Wu TJ, Rosenberg JJ, Roberts JL. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and NMDA receptor gene expression and colocalization change during puberty in female rats. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5281–5289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05281.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller BH, Olson SL, Levine JE, Turek FW, Horton TH, Takahashi JS. Vasopressin regulation of the proestrous luteinizing hormone surge in wild-type and Clock mutant mice. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:778–784. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.052845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerhold LM, Wise PM. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide regulates dynamic changes in astrocyte morphometry: impact on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2197–2202. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de la Iglesia HO, Meyer J, Carpino A, Schwartz WJ. Antiphase oscillation of the left and right suprachiasmatic nuclei. Science. 2000;290:799–801. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de la Iglesia HO, Meyer J, Schwartz WJ. Lateralization of circadian pacemaker output: Activation of left- and right-sided luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons involves a neural rather than a humoral pathway. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7412–7414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07412.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueda HR, Chen W, Adachi A, Wakamatsu H, Hayashi S, Takasugi T, Nagano M, Nakahama K, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Iino M, Shigeyoshi Y, Hashimoto S. A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night. Nature. 2002;418:534–539. doi: 10.1038/nature00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, Su AI, Schook AB, Straume M, Schultz PG, Kay SA, Takahashi JS, Hogenesch JB. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamazaki S, Numano R, Abe M, Hida A, Takahashi R, Ueda M, Block GD, Sakaki Y, Menaker M, Tei H. Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science. 2000;288:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stokkan KA, Yamazaki S, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M. Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding. Science. 2001;291:490–493. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Popa SM, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. The role of kisspeptins and GPR54 in the neuroendocrine regulation of reproduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]