Abstract

Background

HIV viral suppression is associated with health benefits for people living with HIV and a decreased risk of HIV transmission to others. The objective was to identify demographic, psychosocial, provider and neighborhood factors associated with sustained viral suppression among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Methods

Data from adult men who have sex with men (MSM) enrolled in the Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program (RWP) before 2017 were used. Sustained viral suppression was defined as having an HIV viral load < 200 copies/ml in all viral load tests in 2017. Three-level (individual, medical case management site, and neighborhood) cross-classified mixed-effect models were used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for sustained viral suppression.

Results

Of 3386 MSM, 90.8% were racial/ethnic minorities, and 84.4% achieved sustained viral suppression. The odds of achieving sustained viral suppression was lower for 18–24 and 25–34 year-old MSM compared with 35–49 year-old MSM, and for non-Latino Black MSM compared with White MSM. Those not enrolled in the Affordable Care Act, and those with current AIDS symptoms and a history of AIDS had lower odds of achieving sustained viral suppression. Psychosocial factors significantly associated with lower odds of sustained viral suppression included drug/alcohol use, mental health symptoms, homelessness, and transportation to appointment needs. Individuals with an HIV physician who serves a larger volume of RWP clients had greater odds of sustained viral suppression. Neighborhood factors were not associated with sustained viral suppression.

Conclusion

Despite access to treatment, age and racial disparities in sustained viral suppression exist among MSM living with HIV. Addressing substance use, mental health, and social services’ needs may improve the ability of MSM to sustain viral suppression long-term. Furthermore, physician characteristics may be associated with HIV outcomes and should be explored further.

Keywords: Human immunodeficiency virus, Viral suppression, Sustained viral suppression, Durable viral suppression, Men who have sex with men

Background

Suppression of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (< 200 copies/mL) among people living with HIV (PLHIV) is associated with immune reconstruction [1] and a decreased risk of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining conditions [2] and death [3]. In addition, viral suppression prevents the transmission of HIV to others [4]. A recent analysis of National HIV Surveillance System and National HIV Behavioral Surveillance data showed a rate of 0 per 100 person-years of HIV transmission for individuals on antiretroviral therapy (ART) with suppressed viral loads, but a rate of 6.1 per 100 person-years for individuals in care who were not virally suppressed [4].

Despite these benefits, only 61.2% of men who have sex with men (MSM) with HIV in the United States showed evidence of viral suppression in 2014 [5]. Black MSM showed particularly low rates of viral suppression (52.2%) compared with non-Latino White MSM (61.2%) [5]. Young MSM also show concerning rates of viral suppression. Further, the intersection of race/ethnicity and young age put minority MSM at risk, with Black MSM aged 20–24 years showing viral suppression rates as low as 45.3% compared with 60.7% of 20–24 year old White MSM [5].

A significant limitation of previous research on viral suppression has been the use of a single viral load test, typically the last of a given year, to determine an individual’s suppression status. A study of adult PLHIV in care found that a single test measure overestimates sustained viral suppression (all tests in a year < 200 copies/mL) by approximately 16% [6]. Moreover, sustained viral suppression was lower among MSM compared with heterosexual individuals, with 22% of MSM having both suppressed and non-suppressed laboratory tests in the 12-month study period [6]. Non-Latino Blacks and young individuals were also more likely to have fluctuating viral suppression results compared with non-Latino Whites and older PLHIV, respectively [6]. Similarly, a 2018 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study found that MSM with HIV who were in care but who did not achieve sustained viral suppression spent approximately 46.8% of days in the year with viral loads > 1500 copies/mL [7]. Black MSM spent 53.4% days of the year with viral loads > 1500 copies/mL compared with 37.8% of the year for Whites [7].

These findings from previous studies have strong implications for transmission risk. However, little is known about the factors that affect PLHIV’s ability to sustain viral suppression long-term, including MSM. Thus, the objective of this study was to identify demographic, psychosocial, provider and neighborhood factors associated with sustained viral suppression among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Methods

Study population and study design

Data from adult (18 years or older) gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men enrolled in the Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program (RWP) Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative (MAI) [8] any time before January 2017 were used to conduct a cross-sectional study. Enrollment in the RWP was defined as having at least one medical case management encounter or peer education support network service during 2017. RWP clients are required to have a comprehensive health assessment every 6 months. Thus, individuals without a client health assessment in 2016 or 2017 were considered not enrolled and excluded. Additionally, those referred for ancillary services to the RWP by a non-RWP HIV provider, and those whose client file was closed because of movement to another county/state, financial ineligibility, or incarceration were excluded (11.9%). Male RWP clients were classified as gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (herein after referred to as “MSM”) if they reported any MSM behavior.

Outcome

HIV viral load data were obtained from viral load laboratory test results. Sustained viral suppression was defined as having a HIV viral load < 200 copies/ml in all viral load tests in 2017. A viral load of < 200 copies/ml was chosen to stay consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition for an undetectable viral load and to be able to compare to national studies [9]. If any test in 2017 was ≥200 copies/ml (not suppressed), they were considered not to have achieved sustained viral suppression in 2017. If an individual had only 1 viral load test in 2017 (or more than 1 test but the tests were less than 3 months apart) and the test showed viral suppression, we looked to the last viral load test in 2016 in an effort to assess consistent viral suppression on at least 2 tests [7]. Individuals with only 1 suppressed viral load test in 2017 and no viral load tests in 2016, or with no viral load tests in 2017 were excluded (n = 216; 6.0%).

Predictors

Demographic data were obtained from the client intake assessment conducted at time of entry into the RWP. Demographic variables considered included age, race/ethnicity, birth region, and preferred language. Race was categorized into non-Latino Black, Latino, and non-Latino White. Due to small numbers of Haitians (n = 46), those reported as Haitian were categorized based on data about their race and Latino ethnicity (non-Latino Black = 43, Latino = 2, White = 1). Also because of small numbers, those with race other than Black or White (Asian = 21, Native American/Alaskan Native = 5, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander = 2), and those with unknown Latino ethnicity (n = 3) were excluded.

Psychosocial data were obtained from the first comprehensive health assessment conducted in 2017 and pertain to the clients’ responses at that time [8]. We chose the psychosocial variables based on the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations [10] and what was available from the comprehensive health assessment, and grouped the variables into need and vulnerable/enabling characteristics. Need characteristics included AIDS diagnosis, and current HIV-related symptoms. Vulnerable/enabling characteristics included 30 variables related to mental health, substance and alcohol use, HIV status disclosure, employment/disability status, income, household structure, access to transportation, social services need, and social support (see Additional File 1 for details). Individuals with missing data on psychosocial indicators were categorized into the lower risk groups (e.g. no alcohol use). We developed indices of vulnerable/enabling factors to reduce collinearity by conducting reliability analysis and exploratory factors analysis, followed by confirmatory factor analysis. In reliability analysis, we removed 13 vulnerable/enabling variables which increased the Cronbach’s alpha from 0.33 to 0.62. Factor analysis using Varimax rotation yielded 5 indices: substance use, mental health, housing and transportation needs, unemployment, and food insecurity and low social support. Factor loadings are provided in Additional File 1; one variable was deleted due to a factor loading < 0.4 (experience of domestic violence). See Table 1 for variables included in each index.

Table 1.

Characteristics of men who have sex with men by sustained viral load suppression, 2017 (n = 3386)

| Total | Sustained viral load suppression | P-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | |||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age group (years) | < 0.0001 | |||

| 18–24 | 191 | 51 (26.7) | 140 (73.3) | |

| 25–34 | 817 | 163 (20.0) | 654 (80.0) | |

| 35–49 | 1292 | 183 (14.2) | 1109 (85.8) | |

| 50+ | 1086 | 132 (12.2) | 954 (87.8) | |

| Race | < 0.0001 | |||

| Black | 446 | 141 (31.6) | 305 (68.4) | |

| Hispanic | 2630 | 348 (13.2) | 2282 (86.8) | |

| White | 310 | 40 (12.9) | 270 (87.1) | |

| Birth region | < 0.0001 | |||

| United States | 847 | 194 (22.9) | 653 (77.1) | |

| Mexico/Central America | 342 | 58 (17.0) | 284 (83.0) | |

| Caribbean | 1348 | 186 (13.8) | 1162 (86.2) | |

| South America | 765 | 80 (10.5) | 685 (89.5) | |

| Other | 84 | 11 (13.1) | 73 (86.9) | |

| Mainland US Born | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes (excludes Puerto Rico, US Virgin Island and other US territories) | 847 | 194 (22.9) | 653 (77.1) | |

| No | 2539 | 335 (13.2) | 2204 (86.8) | |

| Preferred language | < 0.0001 | |||

| English | 1239 | 255 (20.6) | 984 (79.4) | |

| Spanish | 2081 | 261 (12.5) | 1820 (87.5) | |

| Other | 66 | 13 (19.7) | 53 (80.3) | |

| Health care environment characteristics | ||||

| Number of Ryan White clients that client’s physician cares for | < 0.0001 | |||

| 1–9 | 72 | 6 (8.3) | 66 (91.7) | |

| 10–29 | 97 | 16 (16.5) | 81 (83.5) | |

| 30–99 | 537 | 113 (21.0) | 424 (79.0) | |

| 100–199 | 910 | 138 (15.2) | 772 (84.8) | |

| 200+ | 1585 | 212 (13.4) | 1373 (86.6) | |

| Unknown | 185 | 44 (26.8) | 141 (76.2) | |

| Enrolled in the Affordable Care Act health insurance exchange | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 643 | 53 (8.2) | 590 (91.8) | |

| No | 2743 | 476 (17.4) | 2267 (82.6) | |

| HIV/AIDS-related health status | ||||

| AIDS symptoms (current) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 36 | 19 (52.8) | 17 (47.2) | |

| No | 3350 | 510 (15.2) | 2840 (84.8) | |

| Diagnosis of AIDS (history) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 1021 | 208 (20.4) | 813 (79.6) | |

| No | 2365 | 321 (13.6) | 2044 (86.4) | |

| Factors in substance use index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.02 (0.96) | 0.34 (1.44) | −0.09 (0.82) | |

| Median (IQR) | −0.33 (0) | −0.33 (0.74) | − 0.33 (0) | < 0.0001 |

| Alcohol use | < 0.0001 | |||

| Used alcohol in the last 12 months | 418 | 110 (26.3) | 308 (73.7) | |

| Did not use alcohol in last 12 months | 2968 | 419 (14.1) | 2549 (85.9) | |

| Drug use | < 0.0001 | |||

| Used drugs in the last 12 months | 235 | 85 (36.2) | 150 (63.8) | |

| Did not use drugs in the last 12 months | 3151 | 444 (14.1) | 2707 (85.9) | |

| Drug use resulted in problems with daily activities/legal issue/hazardous situation | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 56 | 29 (51.8) | 27 (48.2) | |

| No | 3330 | 500 (15.0) | 2830 (85.0) | |

| Drug use affected adherence | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 172 | 57 (33.1) | 115 (66.9) | |

| No | 3214 | 472 (14.7) | 2742 (85.3) | |

| Factors in mental health index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.01 (0.99) | 0.33 (1.26) | −0.08 (0.91) | |

| Median (IQR) | −0.49 (0) | − 0.49 (1.24) | − 0.49 (0) | < 0.0001 |

| Feeling depressed or anxious | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 488 | 130 (26.6) | 358 (73.4) | |

| No | 2898 | 399 (13.8) | 2499 (86.2) | |

| Having difficulty sleeping | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 359 | 99 (27.6) | 260 (72.4) | |

| No | 3027 | 430 (14.2) | 2597 (85.8) | |

| Receives or needs mental health services | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 486 | 132 (27.2) | 354 (72.8) | |

| No | 2900 | 397 (13.7) | 2503 (86.3) | |

| Factors in housing and transportation index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.01 (0.99) | 0.38 (1.49) | −0.08 (0.84) | |

| Median (IQR) | −0.32 (0) | − 0.32 (0) | −0.32 (0) | < 0.0001 |

| Homeless | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 133 | 51 (38.4) | 82 (61.7) | |

| No | 3253 | 478 (14.7) | 2775 (85.3) | |

| Client needs help with transportation to appointments | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 230 | 77 (33.5) | 153 (66.5) | |

| No | 3156 | 452 (14.3) | 2704 (85.7) | |

| Factors in household structure index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.01 (1.03) | −0.06 (0.68) | 0.02 (1.08) | |

| Median (IQR) | −0.21 (0) | − 0.21 (0) | −0.21 (0) | 0.0805 |

| Household size | 0.2042b | |||

| One | 3071 | 492 (16.1) | 2579 (84.0) | |

| Two | 264 | 30 (11.4) | 234 (88.6) | |

| Three | 38 | 6 (15.8) | 32 (84.2) | |

| Four or more | 13 | 1 (7.7) | 12 (92.3) | |

| Number of minors in household | 0.3747b | |||

| None | 3315 | 519 (15.7) | 2796 (84.3) | |

| One | 54 | 9 (16.7) | 45 (83.3) | |

| Two | 13 | 0 (0.0) | 13 (100.0) | |

| Three or more | 4 | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Lives with minor only | 0.5987b | |||

| Yes | 6 | 0 (0.0) | 6 (100.0) | |

| No | 3380 | 529 (15.7) | 2851 (84.4) | |

| Factors in unemployment index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.02 (0.99) | 0.19 (1.01) | −0.06 (0.98) | |

| Median (IQR) | −0.56 (1.28) | − 0.56 (1.28) | −0.56 (1.28) | < 0.0001 |

| Disability that prevents working | 0.5154 | |||

| Yes | 246 | 42 (17.1) | 204 (82.9) | |

| No | 3140 | 487 (15.5) | 2653 (84.5) | |

| Unemployed | <.0001 | |||

| Yes | 994 | 237 (23.8) | 757 (76.2) | |

| No | 2392 | 292 (12.2) | 2100 (87.8) | |

| Factors in food insecurity and low social support index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.008 (0.99) | 0.12 (1.24) | −0.03 (0.93) | |

| Median (IQR) | −0.41 (0) | −0.41 (0) | − 0.41 (0) | 0.0578 |

| Client does not have social support system | 0.1721 | |||

| Yes | 626 | 109 (17.4) | 517 (82.6) | |

| No | 2760 | 420 (15.2) | 2340 (84.8) | |

| Client not getting food he needs | 0.0009 | |||

| Yes | 53 | 17 (32.1) | 36 (67.9) | |

| No | 3333 | 512 (15.4) | 2821 (84.6) | |

| Neighborhood deprivation index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.34 (0.86) | 0.51 (0.90) | 0.31 (0.85) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.15 (1.25) | 0.34 (1.56) | 0.15 (1.12) | < 0.0001 |

| Neighborhood residential instability and crime index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.52 (1.07) | 0.60 (1.01) | 0.50 (1.08) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.41 (1.71) | 0.65 (1.61) | 0.41 (1.74) | 0.0315 |

AIDS acquired immune deficiency syndrome, US United States, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

a Chi-square test p-value; b Fisher’s test p-value

To assess provider factors, we calculated the number of RWP clients by HIV physician and assigned this number to all clients who are primarily served by that physician. Additionally, we considered whether the client was enrolled in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health insurance exchange. Neighborhood data were obtained from the 2013–2017 American Community Survey (ACS) by zip code tabulation area (ZCTA) and merged using client’s residential ZIP code [11]. The number of homicides for each ZIP code in Miami-Dade County was obtained from SimplyAnalytics [12]. A total of 25 neighborhood variables were considered (see Additional file 2). Variables were related to 5 categories: socioeconomic status, racial/ethnic composition, language and US nativity, residential instability, and violent crime. We developed indices as described above which yielded 2 indices: neighborhood deprivation, and residential instability and crime.

Analytical plan

All analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.4. Chi-squared (or Fisher’s exact test when applicable) for categorical variables and Wilcoxon signed-ranked test for continuous variables were used to compare sustained viral suppression by demographic, psychosocial, provider, and neighborhood characteristics in bivariate analyses. Three-level (individual, medical case management site, and neighborhood) cross-classified mixed-effects models were used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for sustained viral suppression in multivariate logistic regression analyses using a residual pseudo-likelihood estimation technique in the PROC GLIMMIX procedure. Individuals were allowed to cluster by medical case management site and neighborhood, but these were mutually exclusive groups; the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for each possible combination. We first fitted a cross-classified model that included demographic, provider and need factors, and indices of psychosocial and neighborhood factors (each index was tested as the combined standardized score of the variables in the index). Variable selection was guided by the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations [10] and the literature. Variables in Table 2 were entered all at once into the model. Model fit was assessed by ensuring the ratio of the generalized chi-square statistic and the degrees of freedom was close to 1. For each psychosocial or neighborhood index that was significant in the first model, we fitted separate cross-classified models that included demographic, need and provider factors, and all other indices with each variable in the index of interest one by one. We examined the influence of outliers by inspecting plots and estimates of the Pearson residuals, the deviance residuals, and the DFBETAS. We assessed multicollinearity by examining the Pearson correlation coefficients between all variables in the model and Type II Tolerance values. We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the influence of missing data by comparing results to models excluding individuals with missing data, and by setting the missing values at all possible levels of a given variable.

Table 2.

Factors associated with sustained viral suppression among men who have sex with men

| Variable | AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, years | |||

| 18–24 | 0.511 | 0.341 | 0.766 |

| 25–34 | 0.676 | 0.523 | 0.874 |

| 35–49 | ref | ||

| 50+ | 1.260 | 0.973 | 1.630 |

| Race | |||

| Black | 0.444 | 0.288 | 0.685 |

| Hispanic | 0.784 | 0.502 | 1.226 |

| White | ref | ||

| Not born in mainland US | 0.987 | 0.700 | 1.392 |

| Preferred language | |||

| Spanish | 1.016 | 0.740 | 1.396 |

| Other | 0.800 | 0.391 | 1.635 |

| English | ref | ||

| Number of Ryan White clients that client’s physician cares for | |||

| 1–9 | 2.304 | 0.947 | 5.605 |

| 10–29 | 1.459 | 0.782 | 2.722 |

| 30–99 | ref | ||

| 100–199 | 1.453 | 1.062 | 1.989 |

| 200+ | 1.459 | 1.101 | 1.935 |

| Unknown | 0.850 | 0.546 | 1.325 |

| Client not enrolled in the ACA | 0.657 | 0.478 | 0.903 |

| AIDS symptoms (current) | 0.258 | 0.123 | 0.540 |

| Diagnosis of AIDS | 0.580 | 0.467 | 0.721 |

| Substance use index | 0.816 | 0.747 | 0.891 |

| Mental health index | 0.814 | 0.743 | 0.891 |

| Housing and transportation index | 0.817 | 0.750 | 0.890 |

| Household structure index | 1.169 | 1.009 | 1.353 |

| Unemployment index | 0.918 | 0.830 | 1.015 |

| Food insecurity and social support index | 0.950 | 0.868 | 1.039 |

| Neighborhood deprivation index | 0.952 | 0.843 | 1.075 |

| Neighborhood residential instability and crime index | 0.977 | 0.886 | 1.078 |

AOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence intervals, ACA Affordable Care Act

Bolded values show significant values

Results

Of 3386 MSM enrolled in the Miami-Dade County RWP before 2017, 90.8% were racial/ethnic minorities, with 77.7% being Latino and 75.0% being foreign-born. In 2017, 84.4% of MSM achieved sustained viral suppression. The results of the bivariate analyses are presented in Table 1.

In the multivariate analyses the odds of sustained viral suppression were lower for younger MSM (18–24 [aOR 0.51, 95% CI 0.34–0.77] and 25–34 [aOR 0.68, 95% CI 0.52–0.87] compared with 35–49 year-olds) and for Black MSM compared with White MSM (aOR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29–0.69) (Table 2). Individuals not enrolled in the ACA (aOR 0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.90), currently reporting AIDS symptoms (aOR 0.26, 95% CI 0.12–0.54), and with a history of AIDS diagnosis (aOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.47–0.72) had lower odds of sustained viral suppression. After controlling for demographic, need, provider, and neighborhood factors, four psychosocial indices were associated with lower odds of sustained viral suppression: substance use (aOR 0.82, 95% CI 0.75–0.89), mental health (aOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.74–0.89), housing and transportation (aOR 0.82, 95% CI 0.75–0.89), and household structure (aOR 1.17, 95% CI 1.01–1.35). Individuals with an HIV physician who served a larger volume of RWP clients had greater odds of sustained viral suppression (100–199 [aOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.06–1.99] and 200+ [aOR 1.46, 95% CI 1.10–1.94] compared with 30–99 clients). Neighborhood indices were also not associated with sustained viral suppression.

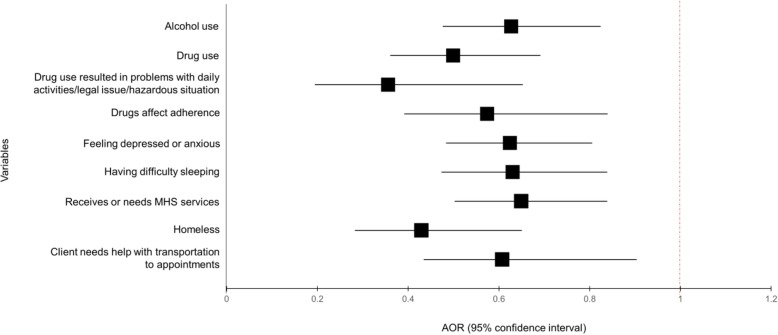

When disaggregating the indices that were significant in the first model, we found most individual variables were strongly associated with lower odds of sustained viral suppression (Fig. 1). This included alcohol use (0.63, 0.48–0.82), drug use (0.50, 0.36–0.69), drug use resulted in problems (0.36, 0.20–0.65), drug use prevented ART adherence (0.57, 0.39–0.84), anxiety or depression (0.62, 0.48–0.81), difficulty sleeping (0.63, 0.47–0.84), needing or receiving mental health services (0.65, 0.50–0.84), homelessness (0.43, 0.28–0.65), and needing transportation help to appointments (0.61, 0.44–0.85).

Fig. 1.

Factors associated with sustained viral suppression among men who have sex with men. Footnote: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; MHS, mental health services; AOR, adjusted odds ratio. AORs adjusted for age, race, US born status, preferred language, number of Ryan White clients HIV physician cares for, client enrolled in Affordable Care Act, psychosocial indices (except index of interest), and neighborhood indices

Regarding the psychometrics of the indices, we assessed convergent validity by calculating the correlation coefficient (CC) between each psychosocial and neighborhood index and sustained viral suppression and all indices were negatively and significantly associated with sustained viral suppression (p-value < 0.001) as expected, except for the household structure index and residential instability indices which did not reach significance. Regarding fitting the cross-classified model, the ratio of the generalized chi-square statistic and degrees of freedom was 1.01 indicating the variability of the data was properly modeled and that there was no residual overdispersion. The ICCs were as follows: same ZIP code and same medical case management site 0.067; same ZIP code and different medical case management site 0.031; different ZIP code and same medical case management site 0.036. The analysis of outliers identified one outlier in the housing structure index; removing the outlier did not change the results. Multicollinearity was not observed; correlations between variables were < 0.8 and Type II Tolerance values were > 0.1. There were no missing data on demographic factors and only 1–4 (0.1%) missing values for mental health variables. Sensitivity analysis categorizing the missing data as missing, “no” (main analysis), and “yes” did not change the findings or statistical significance of the results.

Discussion

Among a sexual minority and predominantly racial/ethnic minority population of MSM living with HIV, nearly 85% had evidence of sustained viral suppression. Our analyses resulted in four important findings. First, young MSM were significantly less likely to achieve sustained viral suppression. Second, racial disparities existed in sustained viral suppression, with Black MSM significantly less likely to achieve sustained viral suppression when compared with White MSM. Third, MSM experiencing drug/alcohol use, mental health symptoms including difficulty sleeping, homelessness and reporting a need for transportation help to appointments were less likely to achieve sustained viral suppression. Finally, clients with providers serving a larger volume of RWP clients were more likely to achieve sustained viral suppression. Notably, neighborhood factors were not associated with sustained viral suppression.

Our rate of sustained viral suppression among MSM (84.4%) was higher than that reported in previous national studies [7, 13–16]. This may be due to a significant upward trend in sustained viral suppression overtime nationwide [13, 17] and among PLHIV enrolled in the Ryan White Program [18] since previous studies used data from 2009 to 2016 and our study used 2017 data. Furthermore, previous studies have focused on the general population of PLHIV. Studies have reported that sustained viral suppression is higher among men compared with women [19] and among MSM compared with all other HIV risk groups [7].

Our finding that young MSM had lower odds of sustained viral suppression is consistent with national studies of the general population of PLHIV [7, 9, 13–15]. A study of 33 United States jurisdictions with complete reporting of viral load tests found that in 2014, 13–24 year old PLHIV were more likely to have unsuppressed viral loads at both their first and last test of the year and were more likely to have worsening viral load status (first test suppressed and last test unsuppressed) compared with all other age groups [15]. Further, a study of New York City HIV surveillance data found that younger PLHIV were more likely to have at least 2 consecutive viral loads ≥100,000 copies/mL [20]. It is worth noting that a study by Mandgasar et al. [18] suggested that age gaps in viral suppression among Ryan White Program clients decreased 2010–2016, thus disparities may be declining. However, this finding was not specific to MSM.

We identified racial disparities in sustained viral suppression with Black MSM having lower odds of sustained viral suppression when compared with White MSM. Our finding in Florida is consistent with findings at the national level for the general population of PLHIV [7, 13–15]. Although sustained viral suppression among Blacks has increased significantly in recent years [13], our findings suggest that Blacks continue to be disproportionately affected by challenges in sustaining viral suppression. Nevertheless, a study of Ryan White Program clients found significant declines in the difference between Blacks and Whites who were virally suppressed from 2010 (13.0 percentage point difference) to 2016 (8.1 percentage point difference) [18]. Worth noting, the percentage of undiagnosed infections is disproportionately higher among some groups including young MSM compared with older MSM and Black MSM compared with White MSM [21]. Given rates of undiagnosed infection, our study may underestimate disparities in sustained viral suppression among MSM. In a post hoc analysis, we tested the interaction between age and race/ethnicity but found it to be nonsignificant (p-value 0.3084).

After disaggregating the indices of psychosocial factors, we found that alcohol and drug use, reporting that drugs resulted in problems, and reporting that drugs prevented ART adherence were associated with decreased odds of sustained viral suppression. We were unable to identify other studies that examined the effect of these drug and alcohol-use related variables on sustained viral suppression with the exception of a study that found that reporting injection drug use (IDU) as an HIV risk factor was associated with decreased odds of sustained viral suppression compared with MSM behavior [17]. Of note, our study included 47 MSM that also reported IDU as an HIV risk exposure. Our findings are particularly important among MSM, as the prevalence of drug and alcohol use among this population is high [22], and drug use has been associated with poor ART adherence [23]. A recent study suggested that anticipated substance use stigma is associated with ART adherence among drug users, even after controlling for severity of drug and alcohol use [24]. MSM with HIV may experience multiple stigmas related to their sexual orientation, their HIV status and substance using behavior. Thus, addressing the compounded stigmas in this population may be one mechanism to target to increase sustained viral suppression.

Additionally, we found that feelings of anxiety or depression, difficulty sleeping, receiving or needing mental health services, as well as reporting homelessness were associated with decreased odds of sustained viral suppression. While studies have examined mental health [25] and homelessness [23, 26] as it relates to viral suppression at one given time, none have looked at these factors in relation to consistent viral suppression which requires long-term ART adherence. A study of homeless PLHIV receiving ART found that 31% of study participants discontinued ART. Among those who discontinued ART, only 51% were adherent to ART and 9% had viral loads < 400 copies/mL [23]. Further, among clients of a Ryan White Part-A funded Care Coordination Program (CCP), viral suppression was higher among those who were homeless at baseline but who obtained stable housing post-baseline compared with those who remained homeless [26]. It is important to discuss the interaction of these psychosocial factors (substance use, mental health, and homelessness) because MSM who report drug use or binge drinking are more likely to report having unstable living environments and having a severe mental health disorder [27]. These factors appear to be harder to address as a previous study showed smaller decreases in viral suppression among Ryan White Program clients who experience unstable or temporary housing compared with those with stable housing over a 6-year period [18]. Our study also suggests other social service’s needs, such as reporting a need for transportation help to appointments, may also affect sustained viral suppression consistent with barriers to linkage to HIV care identified in a qualitative study of US clinics [28].

Clients with providers serving a larger volume of RWP clients were more likely to achieve sustained viral suppression in our study. Our study was only able to measure the volume of RWP clients a physician sees, not the volume of all HIV patients. Our findings are consistent with several other studies that found HIV physician volume associated with HIV care and treatment outcomes [29–31]. Our findings may reflect provider experience with caring for PLHIV, or characteristics of the clinics in which they practice. Clinics with providers that serve a large volume of RWP clients likely also have medical case managers that are well versed in RWP requirements and who also have substantial expertise in serving a racial/ethnic diverse and low socioeconomic status population with significant social services needs and psychosocial barriers. Thus, more research is needed to better understand the role of physician characteristics in HIV outcomes. Additionally, other provider factors, which we were unable to measure, may also be important. A longitudinal cohort study in Baltimore among PLHIV with a history of injection drug use found that only having the same HIV provider > 90% of the time was associated with decreased odds of virologic failure [32].

Being enrolled in the ACA was associated with sustained viral suppression in our study. The effect of the ACA may be due to differences in income as clients must have an income of at least 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL) to be eligible for ACA. In post hoc analyses, we found that sustained viral suppression among those below 100% of FPL was 74.4% compared with 88.7% for those with incomes ≥100% of FPL (p-value < 0.0001). Of note, similar to our study, the two national studies by Crepaz et al. [15] and Bradley et al. [13] that found disparities in sustained viral suppression across age and race/ethnicity included only people receiving care. Bradley et al. [13] further controlled for ART prescription but disparities remained, suggesting factors other than access to care and treatment are important in sustained viral suppression such as the psychosocial factors identified in this study.

Finally, neighborhood factors were not associated with sustained viral suppression in our study. Our finding is inconsistent with one study of New York City surveillance data which suggested that while neighborhood poverty was not associated with achieving viral suppression, it was associated with lower likelihood of maintaining viral suppression after diagnosis [33]. However, the literature on the effect of neighborhoods on viral suppression is mixed with some studies showing an association between residing in areas of high deprivation and poor viral suppression [34, 35], and others showing no association [36, 37]. It is possible that neighborhood units smaller than the ZIP code or other neighborhood characteristics not measured in this study, particularly perceptions of one’s neighborhood, may be important. For example, a study found an association between perceived neighborhood disorder and ART non-adherence [38].

Our study has several limitations. The RWP serves PLHIV who are uninsured; thus, they are not representative of all MSM living with HIV. A second limitation relates to our definition of sustained viral suppression. While we are able to confidently say that those with only 1 viral load test that was ≥200 copies/ml did not achieve sustained viral suppression, we had to exclude those with only 1 viral load of < 200 copies/ml. We decided to exclude these clients because with only 1 viral load test result, we were unable to determine whether they were consistently suppressed. We compared demographic variables for those with missing vs. no missing sustained viral suppression data and found that those with missing data were more likely to be 34 years old or younger (p-value <.0001), black (p-value 0.0027), US born (p-value <.0001), English speaking (p-value <.0001), and less likely to be enrolled in the Affordable Care Act, all factors associated with not achieving sustained viral suppression. Finally, data were collected by numerous medical case managers for the purposes of service delivery. Thus, psychosocial information, particularly data about substance/alcohol use and mental health, were not collected using validated questionnaires, clinical evaluation tools, or procedures, and included only dichotomous yes/no response options.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, our study is the first to examine characteristics at various levels (i.e. individual, provider, and neighborhood), together with psychosocial factors, that may be playing a role in the ability of MSM with HIV to sustain their viral loads suppressed over time. Our analyses showed that, despite access to treatment, age and racial disparities in sustained viral suppression exist among MSM living with HIV. Addressing substance use, mental health, and social services’ needs may improve the ability of MSM to sustain viral suppression long-term. Further, physician characteristics may be associated with HIV outcomes and should be explored further.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Variables considered for health need and psychosocial indices

Additional file 2. Variables considered for neighborhood indices

Acknowledgements

Meetings at which part of the findings were presented: National Hispanic Science Network, New Orleans, LA, October 9, 2019.

Abbreviations

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- ACS

American Community Survey

- AIDS

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- aOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- ART

Antiretroviral Therapy

- CC

Correlation Coefficient

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

Confidence Intervals

- FPL

Federal Poverty Level

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- MAI

Minority AIDS Initiative

- MSM

Men Who Have Sex with Men

- PLHIV

People living with HIV

- RWP

Ryan White Program

- ZCTA

Zip Code Tabulation Area

Authors’ contributions

DMS designed the study, conducted analyses, and drafted the manuscript. RD, SOG, KPF, TL, MG, PB, RL, MJT were involved in the design of the study, interpretation of findings, provided feedback on all versions of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health & Health Disparities (NIMHD) under Award Numbers R01MD012421, R01MD013563, 5S21MD010683, K01MD013770, and U54MD012393. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Miami-Dade County but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, and so the data are not publicly available. Permission can be requested by contacting the Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study reported in this manuscript was approved by the Florida International University Institutional Review Board. Permission was required from Miami-Dade County to access the Ryan White Program data used in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Diana M. Sheehan, Email: dsheehan@fiu.edu

Rahel Dawit, Email: rdawit@fiu.edu.

Semiu O. Gbadamosi, Email: sgbadamo@fiu.edu

Kristopher P. Fennie, Email: kfennie@ncf.edu

Tan Li, Email: tanli@fiu.edu.

Merhawi Gebrezgi, Email: mgebrezg@fiu.edu.

Petra Brock, Email: pbrock-getz@behavioralscience.com.

Robert A. Ladner, Email: rladner@behavioralscience.com

Mary Jo Trepka, Email: trepkam@fiu.edu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12889-020-8442-1.

References

- 1.Smith CJ, Sabin CA, Youle MS, Kinloch-de Loes S, Lampe FC, Madge S, et al. Factors influencing increases in CD4 cell counts of HIV-positive persons receiving long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1860–1868. doi: 10.1086/425075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park LS, Tate JP, Sigel K, Brown ST, Crothers K, Gibert C, et al. Association of viral suppression with lower AIDS-defining and non-AIDS-defining cancer incidence in HIV-infected veterans: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:87–96. doi: 10.7326/M16-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodger AJ, Lodwick R, Schechter M, Deeks S, Amin J, Gilson R, et al. Mortality in well controlled HIV in the continuous antiretroviral therapy arms of the SMART and ESPRIT trials compared with the general population. AIDS. 2013;27:973–979. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cae9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Z, Purcell DW, Sansom SL, Hayes D, Hall HI. Vital signs: HIV transmission along the continuum of care - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:267–272. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6811e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Mitsch A, Wu B. HIV care outcomes among men who have sex with men with diagnosed HIV infection — United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:969–974. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6637a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks G, Patel U, Stirratt MJ, Mugavero MJ, Mathews WC, Giordano TP, et al. Single viral load measurements overestimate stable viral suppression among HIV patients in care: clinical and public health implications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73:205–212. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crepaz N, Dong X, Wang X, Hernandez AL, Hall HI. Racial and ethnic disparities in sustained viral suppression and transmission risk potential among persons receiving HIV care - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:113–118. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6704a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Resources and Services Administration. Ryan white HIV/AIDS program annual client-level data report 2017. 2018. http://hab.hrsa.gov/data/data-reports. Accessed 26 Jan 2020.

- 9.Crepaz Nicole, Dong Xueyuan, Hess Kristen L., Bosh Karin. Brief Report. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2020;83(4):334–339. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Community Survey. 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. 2018. https://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed 26 Jan 2020.

- 12.SimplyAnalytics Inc. SimplyAnalytics data. 2019. http://simplyanalytics.com/features/. Accessed 25 Jan 2020.

- 13.Bradley Heather, Mattson Christine L., Beer Linda, Huang Ping, Shouse R. Luke. Increased antiretroviral therapy prescription and HIV viral suppression among persons receiving clinical care for HIV infection. AIDS. 2016;30(13):2117–2124. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crepaz N, Tang T, Marks G, Mugavero MJ, Espinoza L, Hall HI. Durable viral suppression and transmission risk potential among persons with diagnosed HIV infection: United States, 2012-2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:976–983. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crepaz N, Tang T, Marks G, Hall HI. Changes in viral suppression status among US HIV-infected patients receiving care. AIDS. 2017;31:2421–2425. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall HI, Gray KM, Tang T, Li J, Shouse L, Mermin J. Retention in care of adults and adolescents living with HIV in 13 US areas. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:77–82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318249fe90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Metlay JP, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Sustained viral suppression in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2012;308:339–342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandsager P, Marier A, Cohen S, Fanning M, Hauck H, Cheever LW. Reducing HIV-related health disparities in the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Ryan white HIV/AIDS program. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:S246–S250. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luna-Gierke RE, Shouse RL, Luo Q, Frazier E, Chen G, Beer L. Differences in characteristics and clinical outcomes among Hispanic/Latino men and women receiving HIV medical care - United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1109–1114. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6740a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terzian AS, Bodach SD, Wiewel EW, Sepkowitz K, Bernard M-A, Braunstein SL, et al. Novel use of surveillance data to detect HIV-infected persons with sustained high viral load and durable virologic suppression in New York City. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh S, Song R, Johnson AS, McCray E, Hall HI. HIV incidence, prevalence, and undiagnosed infections in U.S. men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:685–694. doi: 10.7326/M17-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos G-M, Rowe C, Hern J, Walker JE, Ali A, Ornelaz M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hazardous alcohol consumption and binge drinking among men who have sex with men (MSM) in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss AR, Hahn JA, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Guzman D, Clark RA, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the homeless population in San Francisco: a prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1190–1198. doi: 10.1086/424008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stringer KL, Marotta P, Baker E, Turan B, Kempf M-C, Drentea P, et al. Substance use stigma and antiretroviral therapy adherence among a drug-using population living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2019;33:282–293. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castel AD, Kalmin MM, Hart RLD, Young HA, Hays H, Benator D, et al. Disparities in achieving and sustaining viral suppression among a large cohort of HIV-infected persons in care – Washington, DC. AIDS Care. 2016;28:1355–1364. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1189496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irvine MK, Chamberlin SA, Robbins RS, Kulkarni SG, Robertson MM, Nash D. Come as you are: improving care engagement and viral load suppression among HIV care coordination clients with lower mental health functioning, unstable housing, and hard drug use. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1572–1579. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaller N, Yang C, Operario D, Latkin C, McKirnan D, O’Donnell L, et al. Alcohol and cocaine use among Latino and African American MSM in 6 US cities. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;80:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD. Linking HIV-positive adolescents to care in 15 different clinics across the United States: creating solutions to address structural barriers for linkage to care. AIDS Care. 2014;26:12–19. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landovitz RJ, Desmond KA, Gildner JL, Leibowitz AA. Quality of care for HIV/AIDS and for primary prevention by HIV specialists and nonspecialists. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30:395–408. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rackal JM, Tynan A-M, Handford CD, Rzeznikiewiz D, Agha A, Glazier R. Provider training and experience for people living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003938. 10.1002/14651858.CD003938.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Sangsari S, Milloy MJ, Ibrahim A, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner J, et al. Physician experience and rates of plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among illicit drug users: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Westergaard RP, Hess T, Astemborski J, Mehta SH, Kirk GD. Longitudinal changes in engagement in care and viral suppression for HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS. 2013;27:2559–2566. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328363bff2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiewel EW, Borrell LN, Jones HE, Maroko AR, Torian LV. Neighborhood characteristics associated with achievement and maintenance of HIV viral suppression among persons newly diagnosed with HIV in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:3557–3566. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, Voytek CD, Fiore DJ, Blank M, et al. Individual and community factors associated with geographic clusters of poor HIV care retention and poor viral suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:S37–S43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia Q, Robbins RS, Lazar R, Torian LV, Braunstein SL. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in viral suppression among persons living with HIV in New York City. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burke-Miller JK, Weber K, Cohn SE, Hershow RC, Sha BE, French AL, et al. Neighborhood community characteristics associated with HIV disease outcomes in a cohort of urban women living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2016;28:1274–1279. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1173642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheehan DM, Fennie KP, Mauck DE, Maddox LM, Lieb S, Trepka MJ. Retention in HIV care and viral suppression: individual- and neighborhood-level predictors of racial/ethnic differences, Florida, 2015. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31:167–175. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Levi-Minzi MA, Chen M. Environmental influences on HIV medication adherence: the role of neighborhood disorder. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1660–1666. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Variables considered for health need and psychosocial indices

Additional file 2. Variables considered for neighborhood indices

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Miami-Dade County but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, and so the data are not publicly available. Permission can be requested by contacting the Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program.