Abstract

Background:

Various systemic disorders such as cardiovascular, diabetes, and osteoporosis are linked to periodontitis. Obesity is one such epidemic, and although many studies have addressed its relationship with periodontitis, the mechanism still remains unclear.

Aim:

This study aims to assess the association between obesity and its determinants with clinical periodontal parameters in adult patients visiting a dental college in Haryana.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study was performed in 317 patients visiting a dental college in Gurugram. Obesity parameters such as body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage (BF%), waist circumference (WC), and waist–hip ratio (WHR) were assessed using body fat analyzer (Omron HBF 701). Depending on their BMI, individuals were stratified as overweight (OW), Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 obese. Periodontal status was assessed by plaque index, gingival index, probing pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment level. These periodontal parameters were correlated with BMI, BF%, WC, and WHR. Statistical analysis was done, and P ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results:

The prevalence of periodontitis in OW, Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 obese was 16.4%, 79.2%, 2.8%, and 1.6%, respectively. PPD was significantly associated with obesity determinants, especially among Class 2 and Class 3 obese individuals. Similarly, BF% was associated with all the periodontal parameters.

Conclusion:

Within the restrictions of the study, it can be concluded that obesity and chronic periodontitis are interlinked.

Key words: Body mass index, obesity, overweight, periodontitis, waist circumference, waist–hip ratio

INTRODUCTION

Cbesity is a multifactorial condition, which arises due to an undue storage of fat and further relies on the social, cultural, behavioral, psychological, genetic, and metabolic factors. Chronic periodontal disease is one of the most common diseases affecting the oral cavity of humans, which is an infectious condition distinguished by shift in the microbial ecology of subgingival plaque biofilms and progressive host-mediated destruction of tooth-supporting structures.[1,2] With advancing age, severity of periodontal disease increases, and therefore, in younger population, it is very important to control the risk factors so as to prevent the incidence of the same.[3] Conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and low birth weight are interrelated with periodontitis, as they have been known to influence the onset as well as progression of periodontitis.[2]

According to WHO 2000, obesity/overweight (OW) is defined as a disease in which body fat is excessively accumulated and may adversely affect general health.[4] A person is said to be obese when his body mass index (BMI) is at least 30.0 kg/m2, and for OW, his BMI should be in the range of 25–29.9 kg/m2. Similarly, a person whose BMI is in the range of 19–24.9 (kg/m2) is considered to be of normal weight. BMI is calculated as the ratio of body weight in kilogram divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2). Referring this context, BMI is a chief parameter to foretell obesity-related disease risks in a population.[5,6]

Apart from BMI, the manner in which the fat is stored and distributed also matters. For an instance, central obesity or storage of fat in visceral tissues is strongly related with cardiovascular disease.[4] This kind of storage is termed as “apple-shaped” obesity whereas subcutaneous fat is referred to as “pear-shaped” obesity.

Body fat distribution can be calculated by waist circumference (WC); for men, it is 102 cm, and for women, it is 88 cm.[7]

At present, obesity has become one of the considerable reasons for mortality. Likewise, many diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cancers, dental caries, and periodontal diseases can also be attributed to obesity.[8] Various studies[9,10,11,12] have reported a correlation between OW/obesity and periodontitis. Although few studies describe a positive and moderate association,[12,13,14] some have found no relationship between the two conditions.[13,14]

Not many studies exist in the literature regarding evaluating the association between obesity and periodontitis, especially in the Haryana province of India. Therefore, this study was carried out with the aim of evaluating the association between obesity and its determinants with clinical periodontal parameters in adult patients visiting a dental college in Haryana.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Before initiating this cross-sectional study, ethical clearance was obtained from the university. This study was performed in the department of periodontology in Haryana. The study sample consisted of 317 individuals. The objective of the study was explained to all the participants, and a written informed consent was obtained.

Participants aged between 25 and 70 years with at least 20 teeth in the mouth were recruited. Those who were suffering from any systemic diseases or who were under any antibiotic medication, any periodontal treatment within a duration of 6 months, physically and mentally disabled, and pregnant or nursing women were excluded from the study. Sociodemographic data such as age and gender were considered. BMI, body fat percentage (BF%), WC, hip circumference (HC), and waist–hip ratio (WHR) were utilized to assess obesity. Similarly, pocket probing depth (PPD), clinical attachment level (CAL), plaque index (PI), and gingival index (GI) were utilized to assess the periodontal status of an individual.

All the obesity parameters were taken with individuals wearing light clothes and bare foot. Body fat analyzer (Omron HBF 701 Karada Scan Body Composition Monitor, Kyoto Japan) which works on the principle of bioelectrical impedance was utilized to calculate BF% and BMI. Height, WC, and HC were calculated with the help of measuring tape. WC was quantified at the narrowest point between the umbilicus and the rib cage, and HC was measured at the widest part of the body below the waist with the help of measuring tape. WHR was calculated as the ratio of WC to HC. BMI was calculated as the ratio of weight (kg) to the square of the height in meters [Figure 1]. Obese individuals were classified as Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 obese groups when their BMI was 30–34.9, 35–39.9, and >40, respectively.[5] Obesity, based on WC, was considered when WC was >102 cm (40 inches) in men and >88 cm (35 inches) in women. Obesity, based on WHR, was considered when WHR was >0.90 for men and >0.85 for women.[5,9] Similarly, BF% was considered high when the BF% was ≥25 for men and ≥32 for women.[5,10]

Figure 1.

(a) Body mass index calculated by body mass index analyzer. (b) Measurement of waist circumference with measuring tape. (c) Body mass index analysis of the patient. (d) Measurement of hip circumference with measuring tape. (e) Calculated body fat percentage by the body mass index analyzer

In the same way, periodontitis was considered to be present in a patient when four or more teeth with one site or more with PPD ≥4 mm and CAL ≥3 mm were present.[9,15] Furthermore, the full-mouth periodontal condition was evaluated with PI,[16] GI,[17] PPD,[15] and CAL.[9,15] Third molars were not incorporated.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was performed by evaluating mean and standard deviation for the continuous variables. Nominal categorical data among study groups were compared utilizing Chi-square goodness-to-fit test. The software used for the statistical analysis was Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 21.0 and Epi-info version 3.0. IBM Inc.(Chicago, USA).

The statistical tests applied were one-way ANOVA, post hoc tests, unpaired or independent t-test, and Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) test.

P value was taken significant when <0.05 (P < 0.05), and confidence interval of 95% was taken.[18,19]

RESULTS

The relevant characteristics of the study population are represented in Table 1. The mean age of the study participants was 41.05 ± 10.8. Male patients predominated over female patients (comprising 203 of 317). Obesity determinants and periodontal parameters were assessed in all the individuals. One-way ANOVA test was utilized to analyze the data.

Table 1.

Relevant characteristics of the study population

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sample size | 317 (100) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 203 (64) |

| Female | 114 (36) |

| Age (years) | |

| 25-45 | 230 (72.6) |

| 46-70 | 85 (27.4) |

| Mean age | 41.05 |

| BMI | |

| OW | 52 (16.4) |

| Obesity | |

| Class I | 251 (79.2) |

| Class II | 9 (2.8) |

| Class III | 5 (1.6) |

| NWC | 74 (23.3) |

| HWC | 243 (76.7) |

| WHR | |

| Mean | |

| Male | 0.97 |

| Female | 0.87 |

NWC – Normal waist circumference; HWC – High waist circumference; WHR – Waist-hip ratio; n – Sample size; BMI – Body mass index; OW – Overweight

Table 2 Score of various Periodontal Parameters among different categories of BMI. On comparing mean values of periodontal parameters, significant difference was obtained for all the periodontal parameters (P ≤ 0.012, P ≤ 0.019, P ≤ 0.010, and P ≤ 0.048 for PI, GI, PPD, and CAL, respectively).

Table 2.

Mean plaque index, gingival index, pocket probing depth, and clinical attachment level scores among different categories of body mass index

| BMI categories | PI |

GI |

PPD |

CAL |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | P | Mean±SD | P | Mean±SD | P | Mean±SD | P | |

| OW | 1.58±0.53 | 0.012* | 1.43±0.61 | 0.019* | 3.6±0.56 | 0.010* | 4.18±0.74 | 0.048* |

| Class 1 | 1.81±0.55 | 1.48±0.55 | 3.86±0.88 | 4.24±1.03 | ||||

| Class 2 | 2.11±0.25 | 1.59±0.35 | 4.5±0.55 | 4.71±0.59 | ||||

| Class 3 | 2.04±0.28 | 1.7±0.32 | 4.7±0.37 | 4.87±0.41 | ||||

*Significant (P<0.05). OW – Overweight; SD – Standard deviation; PI – Plaque Index; GI – Gingival Index; PPD – Pocket probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; BMI – Body mass index; P – Probability value

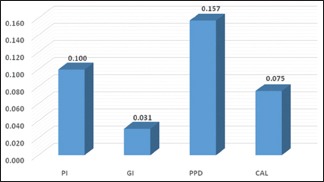

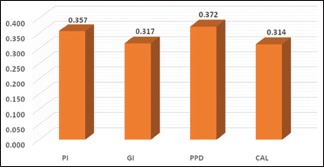

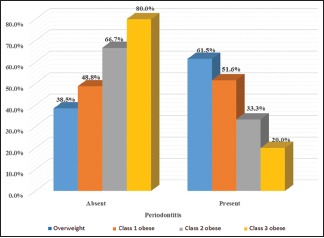

Table 3 represents mean periodontal parameters among normal and high WC and WHR (normal waist circumference [NWC], high waist circumference [HWC] and normal waist–hip ratio [NWHR], high waist–hip ratio [HWHR]). Unpaired t-test was utilized for comparison among these individuals. There was no statistical difference when PI and GI were compared among NWC and HWC (P ≤ 0.0169 and P ≤ 0.577 for PI and GI, respectively). Similarly, on comparison between NWHR and HWHR (P ≤ 0.06 and P ≤ 0.68 for PI and GI, respectively), no significant difference was obtained. However, on comparing the mean values of PPD and CAL scores, a significant difference was obtained. Graphs 1 and 2 indicate correlation of BMI and BF% with different periodontal parameters. Pearson's correlation test was used, and a highly significant result was found between BMI and PPD (P ≤ 0.005), whereas others were nonsignificant. However, highly significant results were found for all the periodontal parameters when correlated with BF% (P ≤ 0.001). Table 4 represents the univariate analysis. All known anthropometric measures were significantly related with increased odds of having periodontitis. In the multivariate analysis, Class 2, Class 3 obesity, HWC, and high BF% individuals remained significantly associated with increased odds of periodontitis. Graph 3 indicates the prevalence of periodontitis in various BMI categories. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the prevalence among different BMI categories. The highest prevalence was seen in Class 1 obese individuals (79.2%) whereas least prevalence was found in Class 3 obese individuals (1.6%).

Table 3.

Mean plaque index, gingival index, pocket probing depth, and clinical attachment level scores among normal waist circumference, high waist circumference, normal waist-hip ratio, and high waist-hip ratio

| Mean±SD |

P | Mean±SD |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NWC | HWC | NWHR | HWHR | |||

| PI | 1.71±0.53 | 1.81±0.55 | 0.169 | 1.61±0.56 | 1.82±0.54 | 0.06 |

| GI | 1.51±0.62 | 1.47±0.53 | 0.577 | 1.38±0.67 | 1.5±0.53 | 0.068 |

| PPD | 3.35±0.77 | 3.84±0.86 | 0.046* | 3.63±1 | 3.89±0.81 | 0.032* |

| CAL | 3.64±0.8 | 4.22±1.02 | 0.027* | 4±1.12 | 4.3±0.94 | 0.039* |

*Significant (P<0.05). NWC – Normal waist circumference; HWC – High waist circumference; NWHR – Normal waist-hip ratio; HWHR – High waist-hip ratio; SD – Standard deviation; PI – Plaque Index; GI – Gingival Index; PPD – Pocket probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; P – Probability value

Graph 1.

Correlation of body mass index with different periodontal parameters. PI – Plaque Index; GI – Gingival Index; PPD – Pocket probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level

Graph 2.

Correlation of body fat percentage with different periodontal parameters. PI – Plaque Index; GI – Gingival Index; PPD – Pocket probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level

Table 4.

Represents univariate and multivariate analysis of body mass index, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and body fat percentage

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| BMI | ||||

| OW | 1 | 1 | ||

| Type 1 obese | 1.45 (1.02-2.92) | 0.040* | 1.22 (0.89-1.19) | 0.114 |

| Type 2 obese | 2.45 (1.21-4.28) | 0.009* | 2.03 (1.11-3.59) | 0.016* |

| Type 3 obese | 5.77 (2.89-9.10) | <0.001* | 4.19 (2.47-7.38) | 0.001* |

| WC | ||||

| Normal | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 2.99 (1.92-5.11) | 0.005* | 2.54 (1.42-3.70) | 0.012* |

| WHR | ||||

| Normal | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 1.88 (1.14-3.51) | 0.011* | 1.38 (1.04-2.09) | 0.081 |

| BF % | ||||

| <30 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >30 | 2.08 (1.23-4.34) | 0.009* | 1.82 (1.10-4.02) | 0.044* |

*Significant (P<0.05). OW – Overweight; WC – Waist circumference; WHR – Waist-hip ratio; BF % – Body fat percentage; OR – Odds ratio; CI – Confidence interval; BMI – Body mass index; P – Probability value

Graph 3.

Prevalence of periodontitis among different body mass index categories

DISCUSSION

Periodontitis is proposed to be associated with obesity and OW, as they affect the host susceptibility by increasing inflammatory mediators leading to periodontitis.[13,20,21]

The unfavored consequence of obesity on the periodontium could be moderated by pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6, and tumor-necrosis-factor [TNF]-α), and an inverse relationship has been reported with antioxidants.[13,21] Genco et al.[22] reported that obesity is linked with high-plasma concentrations of TNF-α, which can lead to a hyperinflammatory state which results in tissue destruction.[21,23]

In the current study, 317 participants were enrolled. The sample size was calculated as depicted by Daniel[24] which is more than the enrolled participants in the studies conducted by Mathur et al.,[10] Ekuni et al.,[2] and Khan et al.[25] However, studies conducted by Bhola et al.[26] and Rivera et al.[27] had more number of participants than the current study.

In the present study, 203 (64%) were males and 114 (36%) were females. Saito et al.[11] conducted a study in 2001 and reported that male persons were affected with obesity more than the females. Whereas, Ana et al.[28] in 2016 found women to be more affected by obesity.

The mean age of study participants was 41.05 ± 10.8. This finding is in accordance to Al-Zahrani et al.[21] and Mathur et al.[10]

In the present study, BMI was used to measure and stratify obese individuals. There are many methods to evaluate obesity but BMI remains the most popular.[3,9,11,29,30] The WHO has also documented that BMI provides the most useful population-level measure of OW and obesity as it is the same for both sexes and all ages of adults.[29] In the present study, depending on the BMI value, participants were stratified into normal weight (<24.9 kg/m2), OW or preobese (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (>30 kg/m2).[5] Obese individuals were further divided into Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 according to the WHO criteria.[5] Among the obese, 16.4% were OW, 2.8% were Class 2 obese, 1.6% were Class 3 obese, and the maximum number of participants were Class 1 category comprising of 79.2%. Not many studies are there in the literature in which they have categorized the obese individuals.[9,3,10] Nevertheless, Pataro et al.[30] have used similar categorization for a study in obese women.

The BMI was correlated with different periodontal parameters, and it was found to be significantly associated with increasing PPD. This finding is in accordance to a study done by Nishida et al.[31] Vecchia et al.[32] proved a positive correlation among periodontitis and obese individuals. Al-Zahrani et al.[21] also confirmed this association of BMI and increased risk of periodontitis.

In the present study, on stratifying the study participants, we found that only 5 individuals could be classified as Class 3 obese. However, univariate (5.77) and multivariate (4.19) analysis revealed highest odds of having PD, as was exhibited by the Class 3 individuals. This suggests definitive relationship between obesity and periodontal disease.

The possible mechanism behind the association among BMI and periodontitis can be attributed to the fact that adipose tissue commonly comprised of 5%–10% macrophages whereas in obese patients, the same tissues reveal approximately 60% macrophage infiltration.[4] Adipocytes produce molecules named adipokines, which are bioactive and have the ability to either modify or activate inflammation and fat metabolism locally or systemically as signaling molecules to liver, muscle, and endothelium. Hence, the adipose tissue is considered to be a highly active endocrine organ.[4,20] Further, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF α and IL-6 are secreted by adipose tissue. This in surge of TNF-α and its receptors results in hyperinflammatory state leading to periodontal attachment loss.[28]

On the contrary, Goodson et al.[33] stated that oral bacterial may have a role in obesity via 3 possible mechanisms. First, the oral bacteria may lead to an increased metabolic efficiency as suggested by the “infectobesity” proponents.[33] As per this phenomenon, a small discrepancy in calorie consumption can cause weight gain. Second hypothesis proposes oral bacteriastimulate the appetite (to gain more nutrients) resulting in increased consumption of food and thus weight gain. A third hypothesis suggests that oral bacteria enhance the levels of TNF-α or decrease adiponectin levels, which facilitates insulin resistance and redirection of the energy metabolism.[33]

The current study also defined obesity by BF%. WHO has provided reference standards as in cutoff values for obesity by BF% among men and women. Men are defined to be obese if BF% >25%, and for women, cutoff values is >35%. Saxlin et al.[34] and Khader et al.[9] also used BF% to define obesity. In our study, BF% is significantly associated with increased PPD and CAL as well with PI and GI. Wood et al.[35] stated that PPD and CAL are the indicators of periodontal disease and further confirmed their correlation with increased BMI.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were utilized to assess the odds ratio (OR), and we found higher OR with high BF% (2.08 [P = 0.009] and 1.82 [P = 0.044]) in univariate and multivariate analysis, respectively. In a study conducted by Khader et al.,[9] OR was 1.84 for persons who had BF% >30. This finding is consistent with our study. Similar results were obtained by Saito et al.[11] and Wood et al.[35]

The stimulation of osteoclast formation and the host response to periodontal pathogens produced by TNF-α induce alveolar bone destruction and participate in connective tissue destruction. The association between IL-6 and periodontitis is not clear, due to the pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of this interleukin.[22]

Considering these facts, WC and WHR were utilized to define obesity. In the present study, 23.3% individuals were having NWC whereas 76.7% had HWC. Diverse results are available in the literature regarding WC. Khader et al.[9] reported 42.5%, Gorman et al. 9%,[36] and Han et al.[12] reported 30% of study participants having HWC. In many studies, measures of abdominal obesity such as WC and WHR were more closely related to periodontal disease than BMI.[21,37]

In the present study, the mean value of WHR in males was 0.97 and females was 0.87. Results are in accordance to Wood et al.,[35] Saito et al.,[11] and Han et al.[12] Various authors have elucidated that visceral fat accumulation (abdominal obesity)[12] that is observed in upper body obesity is associated with more health problems than lower body obesity and subcutaneous fat regardless of BMI.[38,39,40] On examining the variables such as WC and WHR, the present study indicates that increased WC and greater WHR were significantly associated with increased PPD and CAL. Univariate and multivariate analysis were utilized to assess the OR, and we found higher OR with HWC (2.99 [P = 0.005] and 2.54 [P = 0.012]). Similarly, for WHR, higher OR was found to be in HWHR individuals (1.88 [P = 0.011] and 1.38 [P = 0.081]).

These findings are in accordance to Al-Zahrani et al.,[21] in which authors found that WC and prevalence of periodontitis were significantly associated (adjusted OR 2.27) with periodontitis which is less than that of our study. Reeves et al. stated that each 1 cm increase in WC is associated with 5% increase in the risk of periodontitis.[20] Our results for WHR are similar to Saito et al.[11] and Wood et al.[35]

Although the study has shown significant association between obesity and periodontitis, there are few limitations. The cross-sectional design of this study precluded determining the temporal sequence whether the study participants who were diagnosed with periodontitis had accumulated excess fat in their childhood or not. Apart from this, the sample size of the study could have been increased. However, an extension of the study is underway.

Second, the role of genetics and other confounding factors taken such as oral health behaviors, for example, brushing and flossing, psychosocial factors, and eating habits were not considered in the study.

CONCLUSION

Within the constraints of the study, it can be concluded that obesity and periodontitis are associated. Although CAL was not associated with obesity, PPD was significantly correlated with obesity determinants. However, our understanding of how obesity modifies periodontal disease pathogenesis at the molecular level is unknown. Recently, some of these miRNA species have also been identified as possible modifiers of inflammatory pathways.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scannapieco FA. Position paper of the American Academy of Periodontology: Periodontal disease as a potential risk factor for systemic diseases. J Periodontol. 1998;69:841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekuni D, Yamamoto T, Koyama R, Tsuneishi M, Naito K, Tobe K. Relationship between body mass index and periodontitis in young Japanese adults. J Periodontal Res. 2008;43:417–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaffee BW, Weston SJ. Association between chronic periodontal disease and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1708–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nascimento GG, Seerig LM, Vargas-Ferreira F, Correa FO, Leite FR, Demarco FF. Are obesity and overweight associated with gingivitis occurrence in Brazilian schoolchildren? J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:1072–8. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. World Health Organ Technical Report Series 894. World Health Organization. 2000:1–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber FA, Sahrmann P, Schmidlin OA, Heumann C, Beer JH, Schmidlin PR. Influence of obesity on the outcome of non-surgical periodontal therapy – A systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:90. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0272-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amrutiya MR, Deshpande N. Role of obesity in chronic periodontal disease – A literature review. J Dent Oral Disord. 2016;2:1012–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaio EJ, Haas AN, Rösing CK, Oppermann RV, Albandar JM, Susin C. Effect of obesity on periodontal attachment loss progression: A 5-year population-based prospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43:557–65. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khader YS, Bawadi HA, Haroun TF, Alomari M, Tayyem RF. The association between periodontal disease and obesity among adults in Jordan. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathur LK, Manohar B, Shankarapillai R, Pandya D. Obesity and periodontitis: A clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:240–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.85667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Koga T, Tsuzuki M, Ohshima A. Relationship between upper body obesity and periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1631–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800070701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han DH, Lim SY, Sun BC, Paek DM, Kim HD. Visceral fat area-defined obesity and periodontitis among Koreans. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:172–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culebras-Atienza E, Silvestre FJ, Silvestre-Rangil J. Possible association between obesity and periodontitis in patients with Down syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018;23:e335–43. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linden G, Patterson C, Evans A, Kee F. Obesity and periodontitis in 60-70-year-old men. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:461–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peter S. Essentials of Public Health Dentistry. 5th ed. Delhi: Arya Publishers; 2013. Biostatistics and dental health; pp. 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winters R, Winters A, Amedee RG. Statistics: A brief overview. Ochsner J. 2010;10:213–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves AF, Rees JM, Schiff M, Hujoel P. Total body weight and waist circumference associated with chronic periodontitis among adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:894–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Borawskit EA. Obesity and periodontal disease in young, middle-aged, and older adults. J Periodontol. 2003;74:610–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Ho A, Nishimura F, Murayama Y. A proposed model linking inflammation to obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2075–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khosravi R, Ka K, Huang T, Khalili S, Nguyen BH, Nicolau B. Tumor necrosis factor- α and interleukin-6: Potential interorgan inflammatory mediators contributing to destructive periodontal disease in obesity or metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:728987. doi: 10.1155/2013/728987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniel WW. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences. Vol. 37. New York: Wiley; 1999. p. 744. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan S, Barrington G, Bettiol S, Barnett T, Crocombe L. Is overweight/obesity a risk factor for periodontitis in young adults and adolescents? A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2018;19:852–83. doi: 10.1111/obr.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhola S, Varma S, Shirlal S, Jenifer HD, Gangavati R, Warad S. Assessment of association of periodontal disease status with obesity and various other factors among a population of South India. J Obest Metab Res. 2014;14:218–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivera R, Andriankaja OM, Perez CM, Joshipura K. Relationship between periodontal disease and asthma among overweight/obese adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43:566–71. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ana P, Dimitrije M, Ivan M, Mariola S. The association between periodontal disease and obesity among middle-aged adults periodontitis and obesity. J Metab Syndr. 2016;5:2167–3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francis D, Raja B, Chandran C. Relationship of obesity with periodontitis among patients attending a dental college in Chennai: A cross-sectional survey. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2017;15:323–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pataro AL, Costa FO, Cortelli SC, Cortelli JR, Abreu MH, Costa JE. Association between severity of body mass index and periodontal condition in women. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:727–34. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishida N, Tanaka M, Hayashi N, Nagata H, Takeshita T, Nakayama K, et al. Determination of smoking and obesity as periodontitis risks using the classification and regression tree method. J Periodontol. 2005;76:923–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalla Vecchia CF, Susin C, Rösing CK, Oppermann RV, Albandar JM. Overweight and obesity as risk indicators for periodontitis in adults. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1721–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodson JM, Groppo D, Halem S, Carpino E. Is obesity an oral bacterial disease? J Dent Res. 2009;88:519–23. doi: 10.1177/0022034509338353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saxlin T, Ylöstalo P, Suominen-Taipale L, Männistö S, Knuuttila M. Association between periodontal infection and obesity: Results of the health 2000 survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:236–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood N, Johnson RB, Streckfus CF. Comparison of body composition and periodontal disease using nutritional assessment techniques: Third national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES III) J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:321–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorman A, Kaye EK, Apovian C, Fung TT, Nunn M, Garcia RI. Overweight and obesity predict time to periodontal disease progression in men. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:107–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim EJ, Jin BH, Bae KH. Periodontitis and obesity: A study of the fourth Korean national health and nutrition examination survey. J Periodontol. 2011;82:533–42. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura T, Tokunaga K, Shimomura I, Nishida M, Yoshida S, Kotani K, et al. Contribution of visceral fat accumulation to the development of coronary artery disease in non-obese men. Atherosclerosis. 1994;107:239–46. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerji MA, Chaiken RL, Gordon D, Kral JG, Lebovitz HE. Does intra-abdominal adipose tissue in black men determine whether NIDDM is insulin-resistant or insulin-sensitive? Diabetes. 1995;44:141–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rexrode KM, Carey VJ, Hennekens CH, Walters EE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA. 1998;280:1843–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]