Abstract

Gallbladder carcinoma has several atypical presentations, but one of the rarest is intraluminal haemorrhage, which occurs in 1% of patients. We report a case of gallbladder cancer diagnosed by an emergency cholecystectomy, performed for acute cholecystitis caused by a hemocholecyst.

Keywords: biliary intervention, cancer intervention

Background

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a rare malignancy and most diagnoses are made at advanced stages, with the majority (60%–70%)1 being found incidentally during surgery for presumed symptomatic cholelithiasis.2 3 Many authors have reported different presentations of GBC, including empyema, cholecystitis, biliary stricture, liver abscess, gastric outlet obstruction and tumour of the head of the pancreas.4 We describe an unusual presentation of GBC as a hemocholecyst. This entity is unique and not necessarily associated with hemobilia.4

Case presentation

An 87-year-old male patient with dementia, cholelithiasis, antiaggregated with aspirin after having a stroke, presented with right upper quadrant pain and fever with 48 hours of evolution. Further investigations favoured the diagnosis of haemorrhagic cholecystitis, hence a surgical approach was deemed necessary. Postsurgical recovery was unremarkable; the patient was discharged on the seventh day. Histological examination of a haemorrhagic nodule adherent to the mucosa of the gallbladder wall was consistent with a poorly differentiated carcinoma of the gallbladder.

Investigations

Physical examination revealed a confused and anicteric patient. He was normotensive and normocardic, with good peripherical oxygen saturation.

Laboratory findings showed anaemia, leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein, transaminases and alkaline phosphatase (no increase in bilirubin). Abdominal ultrasound and contrast-enhanced CT (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis displayed a gallbladder distension, thickened wall, almost all of it filled by an image with areas of spontaneous hyperdensity compatible with blood and without unequivocal lithiasis (figure 1). The diagnosis of haemorrhagic cholecystitis was admitted and surgery decided (figure 2). This revealed an enlarged gallbladder, gangrenous, completely filled with a blood clot but no evidence of perforation. A cholecystectomy was performed. The nodule detected on pathological examination consisted of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and marked nuclear pleomorphism, with abnormal nuclear features and numerous mitosis figures, some atypical. Histological analysis also revealed concurrent aspects of cholecystitis. Immunohistochemically, the tumorous cells appeared to be strongly positive for CD31, VIII factor and Fli-1 and less positive for AE1AE3, which led to a conditional first histological diagnosis of epithelioid angiosarcoma. The case was then submitted to a second histological revision by an international expert who observed positivity for AE1AE3 and negativity for ERG, CD31, TTF1, NKX3.1, CK7, CK20 and PAX8. Hence, the final diagnosis of a poorly differentiated carcinoma infiltrating the lamina was made and the lymph node near the cystic did not have metastasis—pT1N0 (figure 3).

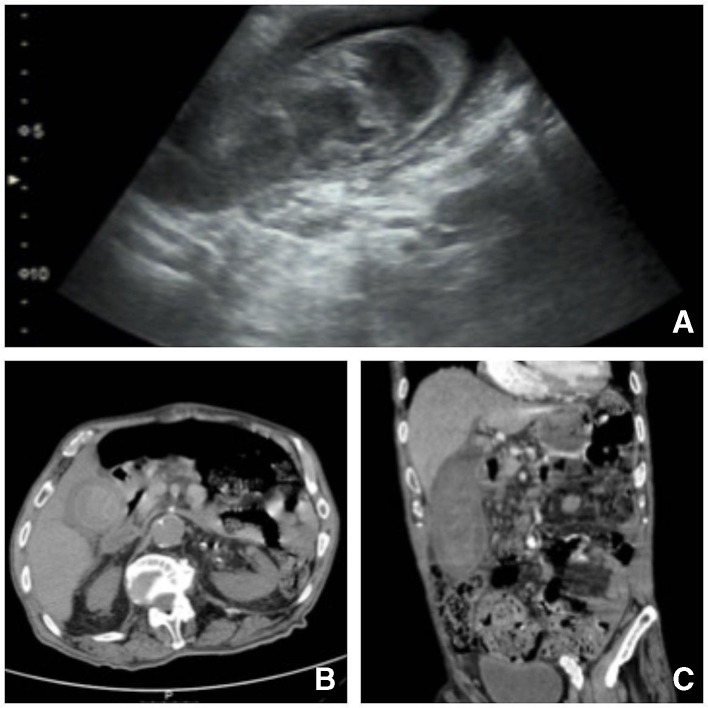

Figure 1.

Ultrasound (A) and CT (B, C) images demonstrating distended gallbladder, thickened/laminated wall, containing bulky image with areas of spontaneous hyperdensity suggesting the presence of a clot in the gallbladder lumen, coexisting perivesicular fat densification, imaging aspects of acute haemorrhagic cholecystitis; there were no signs of active haemorrhage in the lumen of the gallbladder at the time of acquisition of the images; in the infundibulum, an image of spontaneous hyperdensity, which may correspond to the presence of clot versus lithic focus and discrete prominence of the intrahepatic biliary tract.

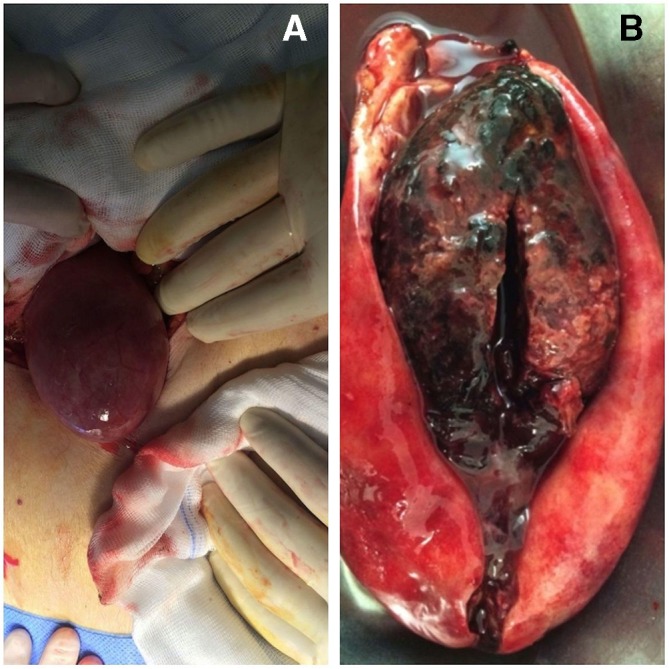

Figure 2.

Intraoperative images of gallbladder’s excision (A). Opening the gallbladder showed what seemed like a spongy clot that filled all its lumen (B).

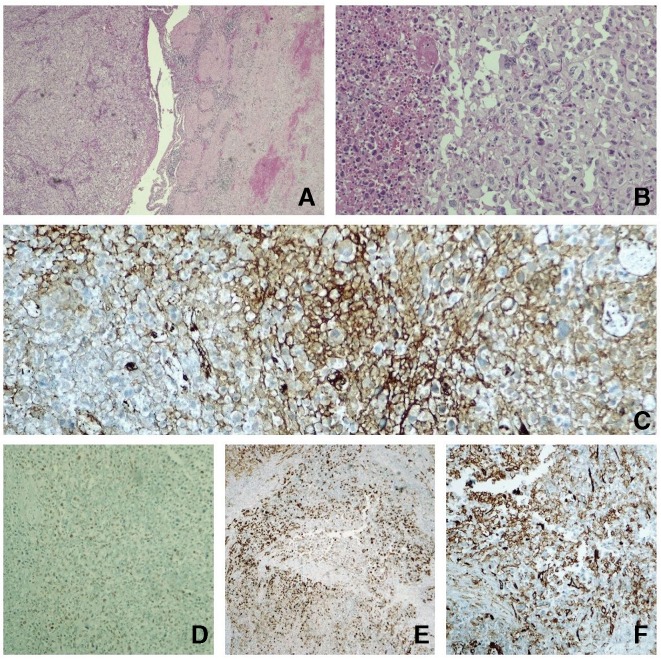

Figure 3.

(A) H&E 40× gallbladder with acute cholecystitis lesions with haemorrhage (right) and where solid pattern neoplasm is identified (left). (B) H&E 200× at higher magnification; the neoplasia consists of epithelioid cells, with marked nuclear pleomorphism and abundant mitosis figures, some atypical, in a dense vascularised stroma with extravasation of erythrocytes. (C) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Factor VIII. (D) IHC FLI1. (E) IHC AE1AE3. (F) IHC CD31. In our study, focal positivity was observed for Factor VIII, FLI1 and CD31 (vascular markers, which led us to consider it to be an angiossarcoma) and also to cytokeratins AE1AE3 (which is not infrequent in angiosarcoma).

Differential diagnosis

The presentation of gallbladder carcinoma may be very difficult to distinguish from benign cholecystitis or may be caused by co-existence of the latter.2

Like in this case, gallbladder carcinoma was easily mistaken for a simple complicated acute cholecystitis. It usually manifests itself through vague and non-specific symptoms such as pain in the right upper quadrant and fever.2 5 6 Our patient also did not present weight loss, anorexia, nausea or vomiting, jaundice and pruritus. Besides that, the features seen on imaging were suggestive of an inflammatory process of the gallbladder as well as a blood material, which led to the presumed diagnosis of haemorrhagic cholecystitis. A hemocholecyst (defined as haemorrhage into the gallbladder, which does not result in rupture of the gallbladder wall) is a very unusual presentation of GBC,4 with six cases being reported in the last 30 years on PubMed. This entity can present due to trauma, malignancy, anticoagulation and bleeding diathesis, such as renal failure or cirrhosis.7–9 In this case, it appears to be secondary to an obstruction of the cystic duct by the tumour itself or to an obstruction of the cystic duct by blood clots.10

In the first report from pathological anatomy, the hypothesis of angiosarcoma was admitted. Areas of inflammation along with areas of haemorrhage were identified, with apparent immunohistochemistry positive for endothelial cells, which led to consider this diagnosis. Indeed, this is a tumour that develops in adult patients, with an age range between 54 and 87 years, and affects predominantly males.11 Though carcinoma also appears in advancing ages, it has female preponderance2 12 13 and the immunohistochemistry, as turned out to be latter when evaluated by an expert, is different.

Treatment

Since the tumour of our patient was limited to the lamina propria (pT1a), simple cholecystectomy was enough.1 12 Attention should be paid to the margin of the cystic duct, since it is the most important prognostic factor in these early cancers.12 In this case, negative surgical margins were obtained, so the surgery was considered curative.

Outcome and follow-up

After definitive pathological result, the patient was immediately referred to the multidisciplinary team. Further staging revealed no distant metastasis. After 10 months of follow-up, the patient has no recurrent disease.

Discussion

GBC is uncommon, is highly fatal and presents geographic variability that correlates with the prevalence of cholelithiasis3; other risk factors include advanced age, female gender, porcelain gallbladder, gallbladder polyps, congenital biliary cysts, chronic biliary infection and smoking.12 The majority of the cases are diagnosed incidentally.2 14

The gallbladder, unlike other structures of the gastrointestinal tract, has no submucosa and, where it attaches to the liver, no serosa is present, which facilitates direct local spread.12

Usually patients do not have any specific symptoms, and if present may mimetize or be secondary to a chronic cholecystitis.2 15 Indeed, most of the cases of GBC are diagnosed following cholecystectomy.1

Initial assessment of patients with biliary-tract symptoms should include an examination by abdominal ultrasound, although it is challenging to differentiate between cholecystitis and early carcinoma.2 12 15 The same is true for CT scanning. Both imaging exams are able to show any of the following appearances: a mass replacing or invading the gallbladder, an intraluminal gallbladder growth/polyp, a calcified and mucosal mass,2 an asymmetric gallbladder wall thickening12 or a loss of interface between the gallbladder and liver.15

There are not reliable tumour markers for the diagnosis of GBC. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19–9 are frequently elevated in advanced stages.5

Incidental gallbladder carcinoma is found in 0.2%–2.9% of all cholecystectomies performed for gallstone disease.16 Adenocarcinoma accounts for almost 90% of GBC.12 14

The aim of the gallbladder carcinoma therapy is to obtain a R0 surgical resection. The management of this patient is made according to the moment of the diagnosis of the carcinoma.15 Those that are T1a or in situ and with negative cystic duct margin do not require more than a simple cholecystectomy. For tumours that are non-metastatic and do not invade beyond the serosa (T1b, T2 and T3), guidelines recommend surgical resection with en bloc liver resection (extended cholecystectomy or Glenn resection) as well as adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy with or without radiation). This should include portal lymphadenectomy and, depending on the extent of the disease, possible common bile duct resection.1 12 17 For those with metastatic or locally unresectable disease, chemotherapy, radiation or both are appropriate and demonstrate improved survival and palliation of symptoms.17

There is no consensus for follow-up.17 In our centre, we have been following this patient every 6 months with clinical examination, laboratory studies that include liver function tests and tumour markers (CA 19–9 and CEA) and surveillance imaging (CT of the abdomen, pelvis and chest). With the exception of T1a or carcinoma in situ, GBC survival is poor.17

Learning points.

Given its clinical presentation and imaging features, the distinction between a cholecystitis and early gallbladder carcinoma is quite challenging before surgery.

The most important underlying risk factors for gallbladder are cholelithiasis and female gender.

Regardless of advances in ultrasound and CT imaging, detecting gallbladder carcinoma in early stages is difficult.

It is important to suspect/make the intraoperative diagnosis (based on macroscopic aspects—whenever possible) in order to perform a curative surgery.

Diagnosis is mainly anatomopathological. And most of the time, when it is done in early stages, the surgery is curative.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Ana Freire Gomes

Contributors: All authors have contributed to and agreed on the content of this manuscript. AFG treated and followed the patient. AFG and SF prepared the manuscript and performed the literature search. JM and JC corrected and revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cavallaro A, Piccolo G, Di Vita M, et al. Managing the incidentally detected gallbladder cancer: algorithms and controversies. Int J Surg 2014;12:S108–19. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A. C. SK, S. B, S. R, et al. Early gallbladder carcinoma with cholelithiasis: a rare case report. Int Surg J 2017;4:2363 10.18203/2349-2902.isj20172799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders G, Kingsnorth AN. Gallstones. BMJ 2007;335:295–9. 10.1136/bmj.39267.452257.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ku J, DeLaRosa J, Kang J, et al. Acute cholecystitis with a hemocholecyst as an unusual presentation of gallbladder cancer: report of a case. Surg Today 2004;34:973–6. 10.1007/s00595-004-2840-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, et al. Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and molecular genetics: recent update. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:3978–98. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.3978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SH, Jung D, Ahn J-H, et al. Differentiation between gallbladder cancer with acute cholecystitis: considerations for surgeons during emergency cholecystectomy, a cohort study. Int J Surg 2017;45:1–7. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon J-N. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis: report of a case. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2012;16:120 10.14701/kjhbps.2012.16.3.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parekh J, Corvera CU. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Arch Surg 2010;145:202–4. 10.1001/archsurg.2009.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seok DK, Ki SS, Wang JH, et al. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis presenting as obstructive jaundice. Korean J Intern Med 2013;28:384–5. 10.3904/kjim.2013.28.3.384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Tovar J, Mingol F, Oller I, et al. Acute cholecystitis caused by hemocholecyst: unusual clinical manifestation of gallbladder cancer. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2013;76:57–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez Acedo P, Herrera Cabezón J, Tarifa Castilla A, et al. Presentación de un caso Y revisión bibliográfica. An Sist Sanit Navar 2015;38:333–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanthan R, Senger J-L, Ahmed S, et al. Gallbladder cancer in the 21st century. J Oncol 2015;2015:1–26. 10.1155/2015/967472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang J-L, Chen M-C, Huang H-Y, et al. Gallbladder carcinoma manifesting as acute cholecystitis: clinical and computed tomographic features. Surgery 2009;146:861–8. 10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duffy A, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, et al. Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering cancer centre (MSKCC). J Surg Oncol 2008;98:485–9. 10.1002/jso.21141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC, et al. Review carcinoma of the gallbladder aetiology and pathogenesis. Lancet Onco 2003;4:167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benkhadoura M, Elshaikhy A, Eldruki S, et al. Routine histopathological examination of gallbladder specimens after cholecystectomy: is it time to change the current practice? Turk J Surg 2019;35:86–90. 10.5578/turkjsurg.4126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu AX, Pawalik TM, Kooby DA, et al. Gallbladder. AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th Amin AB, 2017: 303. [Google Scholar]