Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Keywords: adverse events, Delphi study, multiple sclerosis, nursing, opinion, therapeutic use

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events (AEs) are commonly encountered with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF), an approved treatment for relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS). METHODS: Two hundred thirty-nine MS nurses from 7 countries were asked to complete a 2-round Delphi survey developed by a 7-member steering committee. Questions pertained to approaches for mitigating DMF-associated GI AEs. RESULTS: Ninety-six percent of nurses followed the label recommendation for DMF dose titration in round 1, but 77% titrated the DMF dose more slowly than recommended in round 2. Although 86% of nurses advised persons with relapsing forms of MS (PWMS) to take DMF with food, patients were not routinely informed of appropriate types of food to take with DMF. Most nurses recommended both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic symptomatic therapies for PWMS who experienced GI AEs on DMF. Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic symptomatic therapies were regarded as equally effective at keeping PWMS on DMF. In round 2, 58% of nurses stated that less than 10% of PWMS who temporarily discontinued DMF went on to permanently discontinue treatment. Sixty-six percent of nurses stated that less than 10% of PWMS permanently discontinued DMF because of GI AEs in the first 6 months of treatment in round 1. Most nurses agreed that patient education on potential DMF-associated GI AEs contributes to adherence. CONCLUSION: This first real-world nurse-focused assessment of approaches to caring for PWMS with DMF-associated GI AEs suggests that, with implementation of slow dose titration, symptomatic therapies, and educational consultations, most PWMS can remain on DMF and, when necessary after temporary discontinuation, successfully restart DMF.

Adherence and persistence to disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) for multiple sclerosis (MS) promote optimal outcomes.1–6 Intolerable adverse events (AEs) are a common reason for discontinuing DMDs in the first 2 years of treatment regardless of route of delivery.2,4,7

Delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF) is indicated for the treatment of persons with relapsing forms of MS (PWMS) at a maintenance dosage of 240 mg twice daily by mouth.8,9 As of January 31, 2019, more than 385 000 patients have been treated with DMF, representing more than 710 000 patient-years of exposure. Of these, 6335 patients (12 985 patient-years) were from clinical trials.10 Dimethyl fumarate has shown a favorable benefit-risk profile for PWMS recruited in both clinical trial and real-world settings.11–15 The continuously low level of clinical and neuroradiologic disease activity is reflected in quality-of-life benefits.11,12,14–16

Analysis of AEs from 1529 PWMS with 2244 person-years of exposure to DMF in clinical trials revealed that gastrointestinal (GI) events predominated.10 They present most frequently in the first month of treatment and are usually mild or moderate in severity.17,18 The most common DMF-associated GI AEs are nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.17,19,20

Discontinuation of DMF treatment due to GI AEs has been relatively low in clinical trials (4% DMF, <1% placebo),17 but GI AEs may have a greater impact in clinical practice.18,21–24 In the postmarketing MANAGE and TOLERATE studies conducted in the United States and Germany, respectively, 10% of PWMS starting DMF for the first time discontinued treatment before 12 weeks because of AEs, primarily because of GI AEs.18,23 Preliminary subgroup analysis of data from the real-world PROTEC study of persons with early MS indicates that, during 12 months of DMF use, 11% discontinued DMF because of AEs.21 The most common GI AEs leading to DMF discontinuation in PROTEC were abdominal pain (2%), vomiting (2%), and diarrhea (1%).21

Given that GI AEs represent a leading cause of DMF discontinuation, mitigation strategies that maximize treatment adherence and persistence are warranted.17,18,25 Addressing DMF-associated GI AEs requires collaborative efforts by healthcare professionals. In late 2015, consensus was reached among physicians prescribing DMF on strategies for management of DMF-related GI AEs, including (1) coadministration with food, (2) dose titration for up to 4 weeks when initiating DMF therapy, (3) temporary dose reduction to 120 mg twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks, and (4) use of specific symptom-directed therapies.26 Strategies 1 and 4 are supported by retrospective analysis of the real-world EFFECT study.25 As part of ongoing efforts to improve the treatment experience for PWMS, we surveyed MS nurses to gain insights into their GI AE tolerability practices for PWMS receiving DMF. A modified Delphi methodology was used that investigated DMF uptake and administration, DMF-associated GI AEs, clinical interventions, and education.

Methods

The Delphi technique is a widely accepted structured communication method that builds group consensus on an issue based on responses to iterative rounds of data-gathering and hypothesis-testing questionnaires.27 Our modified Delphi process used 2 rounds of anonymous surveys designed to gather robust, real-world, cross-sectional data on nurse support for PWMS with DMF-associated GI AEs. Caregiving strategies used by nurses to mitigate DMF-associated GI AEs were identified by first gathering feedback regarding best practices and then probing respondents' expertise in patient care, education, and therapeutic support. Our Delphi process started in 2017, when an international steering committee of 7 certified MS nurses with 3 to 11 years of experience caring for PWMS taking DMF was established. Two sequential 30-minute questionnaires focused on identifying GI tolerability practices associated with DMF use were developed (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A205). The first round of the Delphi process featured open-ended questions on the following: (1) the incidence, characteristics, and impact of GI AEs associated with DMF; (2) interventions to ameliorate GI AEs associated with DMF; and (3) GI AE expectation setting for PWMS through education on DMF treatment.

Multiple sclerosis nurses from 7 North American or European countries in whose practices more than 20% of patients had been diagnosed with MS were invited to participate. All MS nurses had to be currently caring for PWMS treated with DMF. The MS nurses provided relevant demographic information, and round 1 and 2 questionnaire responses, through a web-based survey tool (provided by Ashfield Insight and Performance). Questionnaires were issued until the required numbers of responses were obtained in each country. Results from the first round were used to develop a 30-item second questionnaire (round 2), which was sent to round 1 respondents 5 months after the first questionnaire. Respondents were encouraged to provide detailed information and use their clinical judgment when answering questions. They were not referred to any AE definitions other than those provided as part of the questions. Respondents were offered compensation for their time.

Results from closed-ended questions were presented descriptively as incidences, percentages, and means. The number of respondents to whom each question applied was used as the denominator. Open-ended responses were treated as qualitative data and, when possible, coded into ranges and categories.

Results

Respondents

Rounds 1 and 2 were completed 5 months apart by 239 and 190 MS nurses, respectively (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A206). The distribution of respondents by country was fairly even, although representation from Canada was relatively modest at 8% in round 1 and 9% in round 2. Most respondents in round 1 were providing care for 100 or more PWMS receiving a DMD (70%), had more than 5 years of experience treating PWMS (82%), and were actively involved in patient education and support for MS DMDs (93%) (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A207).

DMF Uptake and Administration

Nurse-estimated experience with DMF in their clinics during rounds 1 and 2 was qualitatively similar, indicating internal consistency and hence a lack of bias in the Delphi process (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A208). However, whereas 96% of nurses in round 1 reported that the product label regarding the dose titration schedule (DMF 120 mg twice a day for 7 days followed by the maintenance dose of DMF 240 mg twice a day) was standard protocol at their clinic, 77% of nurses in round 2 reported that PWMS take 2 weeks or more to titrate up to the maintenance dose. This difference in reported titration time may have been due to the use of a closed question in round 1 versus a multiple-choice question in round 2. A second, less likely explanation is that clinical practices changed between rounds 1 and 2.

GI AEs Associated With DMF

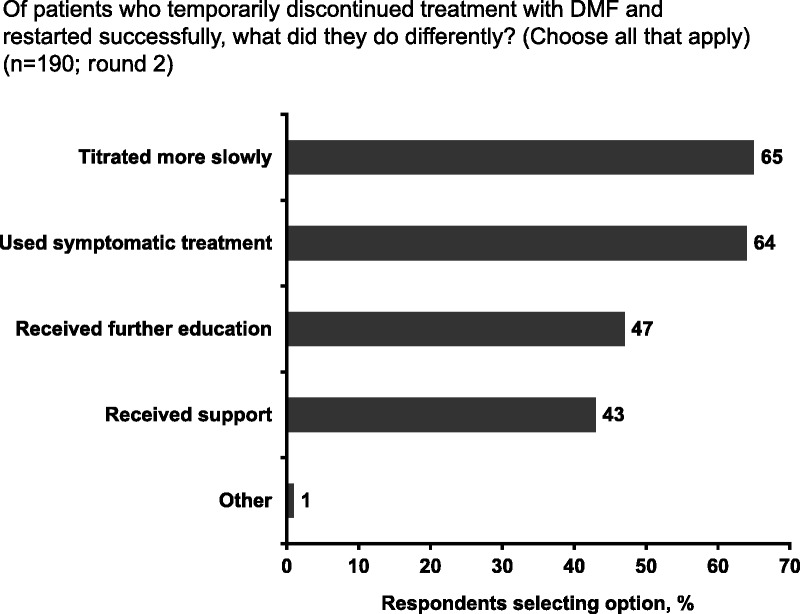

Most nurses (77%) in round 1 reported that no more than 30% of PWMS treated with DMF experienced GI AEs. Similar findings were observed in round 2, when the questions distinguished between PWMS who had started DMF as a first-line therapy and those who had switched to DMF in the last 6 months, with a slight trend toward switching PWMS reporting fewer GI AEs (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A209). Compared with treatment-naive PWMS, those who switched may have been more tolerant of (and therefore less likely to report) DMF-associated GI AEs after the inconvenience and discomfort of injectable therapies. In round 1, 60% of respondents reported PWMS temporarily discontinuing DMF. In round 2, 48% of respondents reported PWMS temporarily discontinuing DMF in the first 6 months post treatment initiation, citing diarrhea (75%) as the most common reason for treatment interruption (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A209). Most PWMS who discontinued successfully restarted treatment, most often by titrating the DMF dosage more slowly than before and using symptomatic therapies (Fig 1). Nausea (mean rank, 2.50) and abdominal pain (mean rank, 2.54) were the most common reasons for permanent discontinuation in the first 6 months, whereas abdominal pain (mean rank, 2.44) was the main reason in subsequent months (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A209). Constipation was the least common reason for permanent discontinuation.

FIGURE 1.

Patient strategies for successfully restarting delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF) treatment after discontinuation (round 2)

Country-specific analysis indicated that the percentage range of PWMS treated with DMF who experienced GI AEs varied widely (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 6, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A210). Most respondents in France (36/37 nurses, 97%) reported that no more than 30% of PWMS treated with DMF experienced GI AEs, whereas only 42% of respondents in Canada (8/19 nurses) reported a similar GI AE rate, with the remaining 58% reporting GI AE rates higher than 30%. Nurses in the United States reported a higher rate of PWMS experiencing DMF-associated GI AEs and permanently discontinuing DMF because of such AEs than nurses in other countries (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 6, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A210).

Interventions

In round 1, respondents estimated that concern about possible GI AEs always or almost always impacts treatment choice for 42% of PWMS and 38% of healthcare providers. For 86% of round 1 respondents, recommending that PWMS take DMF with food is always or almost always standard protocol, although 60% did not specify particular types of food. Only 24% and 23% of respondents recommended that DMF be taken with a high-protein and high-fat meal, respectively. Coadministration of DMF with a meal as opposed to administration of DMF 30 minutes before or after a meal or not coordinated with meals was recommended by 58% of round 1 respondents. Country-specific analysis revealed notable differences among individual countries, with 47% of respondents from Canada (9/19 nurses) and the United Kingdom (17/36 nurses) recommending that DMF be taken with a high-fat meal versus 6% to 22% of respondents from other countries.

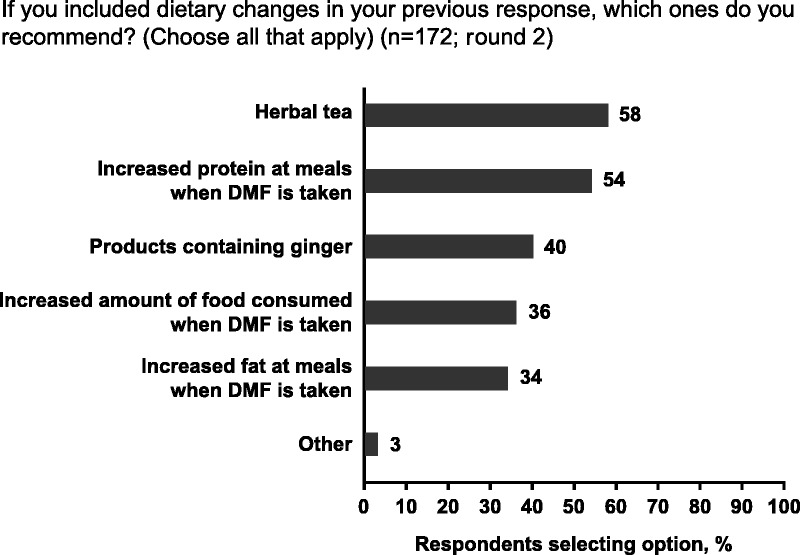

Three-quarters of respondents recommend pharmacologic interventions to help mitigate GI AEs, and two-thirds recommend nonpharmacologic interventions (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 7, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A211). Respondents considered both approaches equally effective, and 68% had recommended both types of intervention in the same patient in the past 6 months. Dietary changes were the most frequently recommended nonpharmacologic intervention, suggested by 91% of nurses (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 7, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A211). The most common dietary changes in response to GI AEs in round 2 were herbal tea and increased protein content (Fig 2). Most respondents (61%) also recommended temporary dose reduction as a nonpharmacologic intervention (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 7, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A211). Round 1 data indicated that the duration of the DMF dose reduction ranges from 1 week to 3 months for upper and lower abdominal pain, from 1 to 2 weeks for nausea and vomiting, from 2 to 3 weeks for diarrhea, and from 1 to 3 weeks for constipation.

FIGURE 2.

Most common dietary changes in response to gastrointestinal adverse events (GI AEs) associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF) in round 2

Education

Most round 1 respondents agreed that education about GI AEs before DMF initiation (96%) and during the first 3 months of treatment (95%) contributes to adherence. In round 1, 90% of nurses provided education to PWMS when initiating DMF, usually as verbal communication in consultations supplemented by written information (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 8, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A212). Most PWMS are counseled on the likelihood of GI AEs before DMF initiation, usually not only by nurses but also by doctors.

Similarly, in round 2, 91% of nurses provided education to PWMS about the prospect of GI AEs (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A207) to empower self-management. Nearly three-quarters of nurses reported spending 11 minutes or more educating PWMS on the possibility of DMF-associated GI AEs before their first dose and on subsequent visits. Educational materials created by clinics were considered the most effective patient-support resource (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, available at http://links.lww.com/JNN/A207).

Discussion

These real-world cross-sectional data provide information on DMF use in clinical practice and on current MS nurse strategies to support PWMS with DMF-associated GI AEs. Most MS nurses reported in round 1 that the label recommendation for DMF dose titration was followed in clinical practice; however, the more recent round 2 analysis suggests that most nurses favor a longer titration period before reaching the maintenance dose. In a previous Delphi study, 200 clinicians highly experienced in prescribing DMF for MS in the United States and Canada characterized this as a useful strategy to reduce the incidence and/or severity of GI AEs.26

The vast majority of nurses (86%) advise PWMS to take DMF with food, the same advice that 98% of clinicians provided in the previous Delphi survey,26 which was consistent with findings from the real-world EFFECT study.25 The product label in Europe and Canada states that DMF should be taken with food, whereas the US product label has no such stipulation; in the latter case, the “take DMF with or without [food]” direction is based on food having no clinically significant effect on the pharmacokinetic profile of DMF.8,9,28 Our survey data show that PWMS are not routinely informed of specific types of food to take with DMF. In the previous Delphi study, consensus was reached that a high-protein, low-starch, and (in particular) high-fat meal had the capacity to reduce the impact of GI AEs with DMF therapy. More research and education are required on the impact of food on DMF administration in PWMS, taking into account cultural variation among the countries surveyed.

An interesting finding was the comparable frequency of use of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions to address specific GI symptoms, which appeared equally effective at keeping PWMS on DMF. The popularity of herbal tea as a dietary intervention was unexpected, highlighting the need to better understand how food and beverages may assuage DMF-associated GI AEs. When comparing the effectiveness of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, consideration must also be given to the therapeutic benefit PWMS derive from talking to a healthcare practitioner about GI AEs as well as the likelihood that PWMS who stay on the medication longer adjust to GI AEs during that time. Most nurses agreed that patient education on potential DMF-associated GI AEs contributes to adherence. The results support the value of care that nurses provide for DMF-treated PWMS, particularly in practices where DMF accounts for a large proportion of all disease-modifying therapies.

Temporary dose reduction as a nonpharmacologic intervention was supported by most round 2 respondents as a strategy to lessen the impact of treatment-emergent GI AEs and is consistent with best practice.23,26 The duration of the dose reduction in round 1 ranged from 1 week to 3 months, depending on GI AE type, which compares with a DMF dose reduction duration of 1 to 2 weeks in previous studies.23,26 Instituting a temporary dose reduction is a shared care decision involving the entire healthcare team and consideration of each patient's preferences.

Given interstudy methodological differences, data from this Delphi study should not be compared with clinical trial data (DEFINE and CONFIRM)17 or real-world data from the United States (MANAGE)18 or Germany (TOLERATE).23 Data from these latter studies were collected directly from patients in a prospective format, and information on discontinuation rates in treatment-naive patients was provided. We would note, however, that most nurses (77%) indicated that 30% or less of PWMS reported GI AEs, slightly lower than the incidence reported in DEFINE and CONFIRM (40%)17 and far lower than that reported in MANAGE and TOLERATE (88% in both).18,23 An important finding not previously published was that nurses report that many PWMS can restart DMF after temporary discontinuation with appropriate strategies in place.

The inclusion of a large number of nurses across several jurisdictions with lengthy experience using DMF is a strength of this analysis. Recall bias was evident in some answers in round 1; this was minimized in round 2 by asking the same questions with a 6-month recall. Outstanding incongruences may relate to changes in clinical practice between rounds 1 and 2 as more knowledge about optimal use of DMF became available. Practice gradients detected across countries require confirmation by another study. Of note, no attempt was made to ascertain whether GI AEs were attributable solely to DMF.

This first real-world assessment of strategies to mitigate DMF-associated GI AEs among nurses in MS clinics suggests that most PWMS are able to remain on DMF treatment. After temporary discontinuation of DMF due to GI AEs, treatment can be restarted successfully with implementation of slow dose titration, symptomatic therapies, and educational consultations. Prospective testing of these strategies is needed in the development of clinical practice recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for responding to the surveys.

Footnotes

All authors on the steering committee received honoraria for developing the Delphi questionnaire. Separately, T.L.C. has received honoraria from Biogen, EMD Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva. B.J.L. has nothing to disclose. L.L.M. has received consulting fees from Biogen, EMD Serono, Genentech, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva. M.N. has received honoraria from Biogen, EMD Serono, Genentech, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva. G.R. has received honoraria from Biogen, Novartis, and Sanofi Genzyme. M.A.R.-S. has received speaking or consulting honoraria or participated in scientific activities organized by Biogen, Celgene, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Teva and was awarded an ECTRIMS MS Nurse Training Fellowship. S.W. has received honoraria from Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Roche. M.E. and C.M. are employed by and may hold stock and/or stock options in Biogen. Biogen provided funding for editorial support in the development of this article.

Malcolm Darkes, PhD, MPS, of Ashfield Healthcare Communications wrote the drafts based on input from authors, in accordance with GPP3 guidelines. Joshua Safran of Ashfield Healthcare Communications copyedited and styled the article per journal requirements. Biogen reviewed and provided comments on the article to the authors. The authors had full editorial control of the article and provided their final approval of all content.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jnnonline.com).

References

- 1.Cerghet M, Dobie E, Lafata JE, et al. Adherence to disease-modifying agents and association with quality of life among patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2010;12:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(1):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerber B, Cowling T, Chen G, Yeung M, Duquette P, Haddad P. The impact of treatment adherence on clinical and economic outcomes in multiple sclerosis: real world evidence from Alberta, Canada. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;18:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannoni G, Southam E, Waubant E. Systematic review of disease-modifying therapies to assess unmet needs in multiple sclerosis: tolerability and adherence. Mult Scler. 2012;18(7):932–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, Stephenson JJ, Kamat S. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther. 2011;28(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uitdehaag B, Constantinescu C, Cornelisse P, et al. Impact of exposure to interferon beta-1a on outcomes in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: exploratory analyses from the PRISMS long-term follow-up study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucchetta RC, Tonin FS, Borba HHL, et al. Disease-modifying therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(9):813–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Medicines Agency Tecfidera 120 mg gastro-resistant hard capsules [summary of product characteristics]. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002601/WC500162069.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

- 9.Biogen Inc Tecfidera® (dimethyl fumarate) delayed-release capsules [highlights of prescribing information]. Available at https://www.tecfidera.com/content/dam/commercial/multiple-sclerosis/tecfidera/pat/en_us/pdf/full-prescribing-info.pdf. Updated December 2017. Accessed September 11, 2018.

- 10.Chan A, Fox RJ, Bar-Or A, et al. Delayed-release dimethyl fumarate–associated lymphopenia: on-treatment and post-treatment implications. Poster presented at: 34th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment & Research in Multiple Sclerosis; October 10–12, 2018; Berlin, Germany.

- 11.Gold R, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, et al. Long-term effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: interim analysis of ENDORSE, a randomized extension study. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2):253–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallucci G, Annovazzi P, Miante S, et al. Two-year real-life efficacy, tolerability and safety of dimethyl fumarate in an Italian multicentre study. J Neurol. 2018;265(8):1850–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miclea A, Leussink VI, Hartung HP, Gold R, Hoepner R. Safety and efficacy of dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: a multi-center observational study. J Neurol. 2016;263(8):1626–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smoot K, Spinelli KJ, Stuchiner T, et al. Three-year clinical outcomes of relapsing multiple sclerosis patients treated with dimethyl fumarate in a United States community health center. Mult Scler. 2018;24(7):942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viglietta V, Miller D, Bar-Or A, et al. Efficacy of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: integrated analysis of the phase 3 trials. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2(2):103–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kita M, Fox RJ, Gold R, et al. Effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF) on health-related quality of life in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis of the phase 3 DEFINE and CONFIRM studies. Clin Ther. 2014;36(12):1958–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips JT, Selmaj K, Gold R, et al. Clinical significance of gastrointestinal and flushing events in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(5):236–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox EJ, Vasquez A, Grainger W, et al. Gastrointestinal tolerability of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in a multicenter, open-label study of patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MANAGE). Int J MS Care. 2016;18(1):9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1087–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1098–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger T, Brochet B, Confalonieri P, et al. Effectiveness of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate on clinical measures and patient-reported outcomes in newly diagnosed and other early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: subgroup analysis of PROTEC. Poster presented at: 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; April 22–28, 2017; Boston, MA.

- 22.Eriksson I, Cars T, Piehl F, Malmstrom RE, Wettermark B, von Euler M. Persistence with dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(2):219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold R, Schlegel E, Elias-Hamp B, et al. Incidence and mitigation of gastrointestinal events in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis receiving delayed-release dimethyl fumarate: a German phase IV study (TOLERATE). Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:1756286418768775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sejbaek T, Nybo M, Petersen T, Illes Z. Real-life persistence and tolerability with dimethyl fumarate. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;24:24–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Min J, Cohan S, Alvarez E, et al. Real-world characterization of dimethyl fumarate-related gastrointestinal events in multiple sclerosis: management strategies to improve persistence on treatment and patient outcomes. Neurol Ther. 2019;8(1):109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theodore Phillips J, Erwin AA, Agrella S, et al. Consensus management of gastrointestinal events associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate: a Delphi study. Neurol Ther. 2015;4(2):137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biogen Canada Inc Tecfidera PM [dimethyl fumarate delayed-release capsules 120 mg and 240 mg]. Available at https://www.biogen.ca/content/dam/corporate/en_CA/pdfs/products/TECFIDERA/TECFIDERA_PM_EN_05_FEB_2019.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.