CCL22-releasing microparticles recruit suppressive immune cells to transplanted rat limbs to promote long-term graft survival.

Abstract

Vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) encompasses face and limb transplantation, but as with organ transplantation, it requires lifelong regimens of immunosuppressive drugs to prevent rejection. To achieve donor-specific immune tolerance and reduce the need for systemic immunosuppression, we developed a synthetic drug delivery system that mimics a strategy our bodies naturally use to recruit regulatory T cells (Treg) to suppress inflammation. Specifically, a microparticle-based system engineered to release the Treg-recruiting chemokine CCL22 was used in a rodent hindlimb VCA model. These “Recruitment-MP” prolonged hindlimb allograft survival indefinitely (>200 days) and promoted donor-specific tolerance. Recruitment-MP treatment enriched Treg populations in allograft skin and draining lymph nodes and enhanced Treg function without affecting the proliferative capacity of conventional T cells. With implications for clinical translation, synthetic human CCL22 induced preferential migration of human Treg in vitro. Collectively, these results suggest that Recruitment-MP promote donor-specific immune tolerance via local enrichment of suppressive Treg.

INTRODUCTION

Each year, millions of individuals sustain unsalvageable composite tissue loss secondary to various etiologies. Vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) is an option in select patients, where current reconstructive strategies are suboptimal or fail in terms of cosmetic or functional outcomes. Over the past decade, various types of VCA transplants have been performed, including hand and face transplants, for which systemic therapy with two or more immunosuppressive drugs is the standard of care (1–3). Despite their efficacy in preventing early graft loss, the overriding concern with conventional immunosuppression is the associated toxic sequela. While early graft survival, functional, and immunological outcomes following VCA are promising, graft rejection and the effects of lifelong immunosuppression continue to hamper wider clinical application (2, 3).

An alternative approach to achieving allograft acceptance without systemic immunosuppressive drugs would be to harness the body’s inherent mechanisms of immune regulation. Cells of the immune system use a variety of mechanisms to maintain immunological homeostasis and promote tolerance. As a hallmark example, our bodies contain a subset of lymphocytes termed regulatory T cells (Treg) that play a critical role in establishing and maintaining immunological homeostasis (4–7). The absence of these cells results in destructive autoimmune responses that underlie a number of diseases (4–11). On the other hand, certain tumors harness endogenous immunological regulatory mechanisms, including Treg recruitment, to avoid immune-mediated destruction (12). More specifically, these tumors recruit circulating Treg to the tumor milieu via the release of the chemokine CCL22, which signals through the corresponding chemokine receptor (CCR4) preferentially expressed by Treg (12–15).

To safely mimic this immune evasion strategy, we developed a synthetic, degradable, controlled release microparticle system capable of generating and sustaining a gradient of CCL22 from the site of microparticle placement in vivo. We previously demonstrated in vivo Treg recruitment toward these CCL22-releasing microparticles (referred to as recruitment-microparticles or Recruitment-MP) via in vivo bioluminescence imaging (16), immunohistochemistry (17), and solid tissue flow cytometry (18). Furthermore, Recruitment-MP resolve destructive inflammation in models of both periodontal and dry eye disease (17, 18). Here, we hypothesized that local administration of Recruitment-MP could promote recruitment of endogenous Treg to the graft and thus prevent immune-mediated VCA rejection (in a stringent hindlimb VCA model) as a first step toward developing a strategy to reduce or even eliminate the need for lifelong immunosuppression.

We demonstrate that local (intragraft) administration of Recruitment-MP prolongs graft survival indefinitely (>200 days). This strategy led to a significant decrease in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in graft skin and draining lymph nodes. Furthermore, our data suggest that Recruitment-MP can even promote antigen-specific tolerance, as evidenced by ex vivo T cell proliferation assays and secondary skin graft challenge. Together, our results demonstrate the unique ability of Recruitment-MP to selectively reduce inflammation within the graft and promote immune homeostasis in a robust model of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–mismatched VCA (19).

RESULTS

Characterization of Recruitment-MP

Recruitment-MP were formulated to produce CCL22 release kinetics such that a physiological gradient of CCL22 could be established for effective Treg recruitment in vivo. These microparticles were made out of a biocompatible, biodegradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) polymer using a well-established double emulsion solvent evaporation technique (16). Scanning electron micrographs of MP indicate that they are spherical and slightly porous (fig. S1A, inset). The surface of Recruitment-MP was formulated to be porous to allow continuous release (without periods of lag) of chemokine. Further, particles were designed to be large enough to avoid uptake by phagocytic cells (i.e., >10 μm) and to prohibit their movement across the vascular endothelium, with consequent immobilization at the site of placement (fig. S1B). Last, Recruitment-MP released CCL22 in a linear manner over a period of 40 days (fig. S1A).

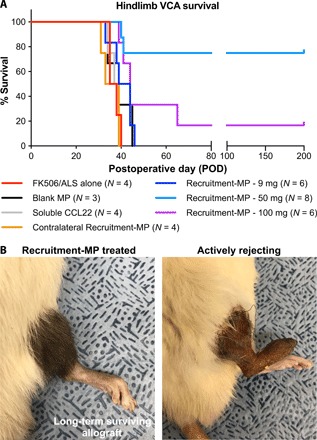

Recruitment-MP prevents rejection and promotes long-term survival of hindlimb allografts

To test the ability of Recruitment-MP to prevent graft rejection in a clinically relevant model of VCA, vascularized hindlimbs were transplanted from Brown Norway (BN) rat donors to Lewis (LEW) recipients (complete MHC mismatch). Animals receiving only the baseline immunosuppression protocol of FK506/ALS (anti-rat lymphocyte serum) (timing presented in fig. S1C) served as controls. These animals consistently rejected grafts 2 to 3 weeks after FK506 was discontinued at postoperative day (POD) 21 (Fig. 1A). Three doses of Recruitment-MP (9, 50, and 100 mg) were tested to determine an effective gradient necessary for recruiting Treg and prolonging graft survival. Minutes after hindlimb transplants were completed, particles were administered by a single subcutaneous injection on the lateral aspect of the hindlimb (to avoid the vascular anastomosis medially) after blunt dissection of the subcutaneous plane with an 18-gauge needle (to allow for better distribution of the particles). MP were administered similarly 21 days after transplant. Animals receiving 9 and 100 mg of Recruitment-MP had a graft mean survival time (MST) of 41.5 and 44.0 days, respectively (Fig. 1A). Treatment with 50 mg of Recruitment-MP significantly prolonged graft survival indefinitely, with long-term survival >200 days in six of eight animals (75%). Furthermore, animals treated with 50 mg of blank MP (MST, 39 days), soluble CCL22 (injected subcutaneously in the allograft) (MST, 37.5 days), and 50 mg of Recruitment-MP injected in the contralateral (nontransplanted) limb (MST, 36.0 days) did not exhibit prolonged graft survival compared to animals receiving only the baseline immunosuppression protocol.

Fig. 1. Treatment with Recruitment-MP (50 mg) prolongs allograft survival indefinitely.

(A) Hindlimb allograft survival curve showing indefinite survival (>200 days) in six of eight rats treated with Recruitment-MP (50 mg). These results are statistically significant (P < 0.05) when compared to all other groups using a log-rank test. (B) Macroscopically, treatment with 50 mg of Recruitment-MP results in acceptance of the graft with normal hair grown and gross skin appearance, as opposed to controls that exhibit hair loss and skin necrosis. Photo credit: James D. Fisher, University of Pittsburgh.

Recruitment-MP treatment leads to long-term surviving allografts with normal tissue architecture and enhances Treg proportions in allografts shortly after transplantation

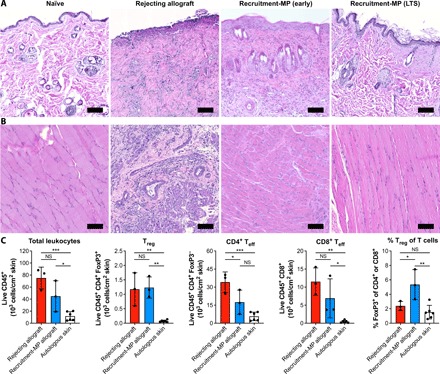

With Recruitment-MP promoting allograft survival, as observed macroscopically, we next examined allograft tissues histologically. Rejecting grafts exhibited sloughing of the epidermis and substantial mononuclear cell infiltration in the dermis and perivascular regions (Fig. 2A). Rejecting grafts also exhibited substantial myositis as evidenced by mononuclear cell infiltration in muscle tissue and disruption of tissue architecture (Fig. 2B). Conversely, biopsies from Recruitment-MP–treated (50 mg) animals with long-term surviving allografts (>200 days) showed minimal cellular infiltration and intact tissue architecture, similar to muscle and skin biopsies from normal animals (Fig. 2, A and B). At earlier time points when allografts rejected in control animals, Recruitment-MP–treated hindlimbs exhibited noticeable mononuclear cell infiltrates in the dermis (albeit less than in rejecting limbs) and low to moderate epidermal hyperplasia (Fig. 2A); however, the epidermis remained intact, and there was substantially less evidence of cellular infiltrates in muscle tissue (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Recruitment-MP preserves the architectural integrity of intragraft tissues and enhances cutaneous Treg frequency.

Representative histology from (A) skin and (B) muscle samples from naïve rats, rejecting allografts, and Recruitment-MP–treated allografts at early (POD 33) or late time points [POD > 200; long-term survivor (LTS)]. Tissue was stained with H&E. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Immune cell populations in skin of rejecting allografts, Recruitment-MP–treated allografts, and autologous skin from contralateral hindlimbs (POD 29 to 43), as determined by flow cytometry on dissociated skin tissue. The flow cytometry gating strategy is presented in fig. S2. Each dot represents the mean of two 1-cm2 skin biopsies from a single animal (N = 3 for allografts and N = 6 for autologous skin). Teff, effector T cells; NS, not significant. Groups were compared by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests, and significant differences are indicated by *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To characterize cellular infiltrates, skin from Recruitment-MP–treated and rejecting control allografts, as well as autologous skin from contralateral hindlimbs, was dissociated into single-cell suspensions and analyzed by flow cytometry. Rejecting allograft skin contained slightly more total leukocytes (live CD45+ cells) and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells than skin from Recruitment-MP–treated allografts, although the differences were not significant. CD4+ FoxP3− effector T cells were significantly reduced in Recruitment-MP–treated grafts, while CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg were found at comparable levels. Autologous skin had significantly fewer total leukocytes and T cells compared to rejecting and Recruitment-MP–treated allografts. The proportion of Treg (% FoxP3+ of total CD4+ or CD8+ T cells) in skin from Recruitment-MP–treated allografts was significantly increased compared to that in both rejecting allografts and autologous skin (Fig. 2C).

Recruitment-MP reduces expression of proinflammatory mediators in skin and draining lymph nodes of hindlimb transplant recipients

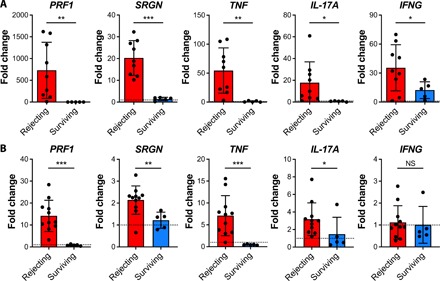

To determine whether treatment with Recruitment-MP could suppress inflammation locally in the context of VCA, intragraft full-thickness skin samples and draining lymph nodes were harvested from actively rejecting animals (grade III to IV rejection) and Recruitment-MP–treated VCA recipients (experimental end point; POD >200). We then measured expression of proinflammatory genes: TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17A, Perforin-1, and Serglycin. Expression of all five genes (normalized to expression in normal tissue) was decreased significantly in skin biopsies from Recruitment-MP–treated VCA recipients when compared to corresponding tissue samples from actively rejecting grafts (Fig. 3A). In draining lymph nodes of Recruitment-MP–treated VCA recipients, expression of TNF-α, IL-17A, Perforin-1, and Serglycin was also significantly decreased compared to actively rejecting animals (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Expression of proinflammatory mediators in skin and draining lymph nodes is reduced in Recruitment-MP–treated long-term surviving allografts.

Relative mRNA expression in (A) skin samples and (B) draining lymph nodes from rejecting hindlimb allografts (N = 9 for skin and N = 11 for draining lymph nodes) or Recruitment-MP–treated long-term surviving allografts (N = 5 for skin and draining lymph nodes). Expression levels are presented as fold changes (2−ΔΔCt) relative to naïve skin (N ≥ 6) or nondraining lymph nodes (N = 7 to 9). Bars represent means ± SD, and dots represent values from individual rats. Groups were compared by Welch’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate, and significant differences are indicated by *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001.

Recruitment-MP increase the incidence of CD4+CD25hiFoxP3+ Treg in draining lymph nodes of long-term surviving allografts and tip the local immune balance

To assess potential mechanisms underlying the enhanced allograft survival associated with Recruitment-MP, local phenotypic changes in the draining lymph nodes of animals with long-term surviving grafts were examined. At the experimental end point (grade III rejection or POD > 200 for long-term survivors), draining and nondraining inguinal lymph nodes were harvested, and the local CD4+ T helper cell phenotype was analyzed. Allograft draining and nondraining lymph nodes from Recruitment-MP–treated animals exhibited a decreased incidence of inflammatory CD4+IFN-γ+ cells (normalized to percentages from naïve animals) when compared to draining lymph nodes from actively rejecting animals. Further, draining lymph nodes from actively rejecting animals demonstrated a higher percentage of CD4+IFN-γ+ cells than from nondraining lymph nodes of actively rejecting animals (Fig. 4B). Allograft draining lymph nodes from Recruitment-MP–treated animals exhibited an increased incidence of CD4+CD25hiFoxP3+ cells (normalized to percentages from naïve animals) when compared to both nondraining lymph nodes from Recruitment-MP–treated animals and draining lymph nodes from actively rejecting animals (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Functional and phenotypic analysis of CD4+ T cells from animals with long-term surviving hindlimb allografts.

Flow cytometric analysis of (A) CD4+ FoxP3+ cells (Treg) and (B) CD4+ IFN-γ+ cells (TH1) isolated from allograft draining lymph nodes (DLN) and contralateral nondraining lymph nodes (NDLN) of long-term surviving (LTS) rats treated with 50 mg of Recruitment-MP, and allograft draining lymph nodes from actively rejecting controls (N = 5). Percent Treg and TH1 were normalized to naïve controls. (C) Proliferative capacity of CD4+CD25− Tconv from long-term surviving Recruitment-MP–treated LEW rats with BN allografts, relative to Tconv from naïve LEW rats (N = 3). Tconv were stimulated with BN splenocytes, and percent proliferation normalized to that of naïve LEW Tconv with BN stimulation. (D) CD4+CD25hi Treg isolated from Recruitment-MP–treated animals (N = 4) were more effective on a per-cell basis at suppressing BN-induced proliferation of naïve Tconv than CD4+ CD25hi Treg isolated from naïve LEW rats (N = 3). Groups were compared by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests (A and B), one-sample t test (C), or Student’s t test (D), and significant differences are indicated by *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001.

Treg from recruitment-MP–treated animals exhibit superior suppressive ability compared to Treg from naïve animals

The suppressive and proliferative capacity of Treg and conventional T cells (Tconv) isolated from Recruitment-MP–treated VCA recipients and naïve LEW rats were measured in mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR). Specifically, splenocytes from both Recruitment-MP–treated VCA recipients and naïve animals were flow-sorted into two groups: CD4+CD25hi (Treg) or CD4+CD25− (Tconv). Tconv from both sets of animals were then cultured with irradiated BN (donor) stimulator splenocytes. There was no observed immune hyporesponsiveness with Tconv isolated from Recruitment-MP–treated animals when compared to normal controls (Fig. 4C). To assess the suppressive function of Treg from Recruitment-MP–treated animals, Treg from naïve or Recruitment-MP–treated animals were cocultured with Tconv from naïve LEW (syngeneic) rats and irradiated BN (donor) splenocytes. Treg isolated from Recruitment-MP–treated animals were more effective than naïve Treg at inhibiting proliferation of naïve Tconv stimulated with BN splenocytes (Fig. 4D).

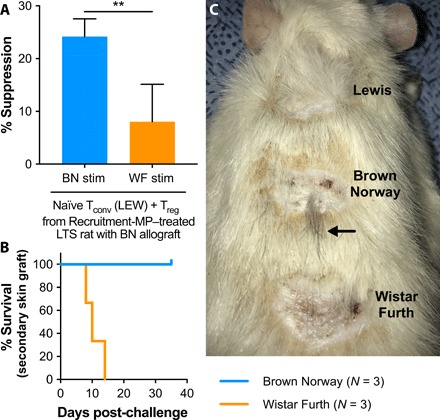

Treg from Recruitment-MP–treated animals exhibit donor-specific suppression of Tconv proliferation

To test the donor antigen specificity of CD4+CD25hi Treg isolated from Recruitment-MP–treated VCA recipients, additional MLRs were performed. Naïve LEW CD4+CD25− Tconv were cocultured with CD4+CD25hi Treg from Recruitment-MP–treated VCA recipients and stimulated with irradiated BN (donor) or Wistar Furth (WF; third party, complete MHC mismatch) splenocytes. Treg from long-term surviving grafts showed enhanced suppressive function (P < 0.05) against BN stimulation compared to WF stimulation on a per-cell basis (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Recruitment-MP confers donor antigen–specific tolerance to animals with long-term surviving grafts.

(A) CD4+ CD25hi Treg from Recruitment-MP–treated animals (N = 4) were cocultured with CD4+ CD25− Tconv from naïve LEW rats and subject to stimulation with either BN or WF (third-party) splenocytes. Treg isolated from Recruitment-MP–treated animals were more effective at suppressing BN-mediated proliferation than WF-mediated proliferation. Groups were compared by Student’s t test, and a significant difference is indicated by **P < 0.01. (B and C) To test for donor antigen–specific tolerance in vivo, Recruitment-MP–treated animals with long-term surviving BN allografts were challenged with full-thickness nonvascularized skin grafts from LEW (syngeneic control), BN (allogeneic), and WF (allogeneic, third-party) donors. Recruitment-MP–treated animals accepted BN grafts, as evidenced by wound healing and hair growth (C, arrow), but failed to accept third-party WF grafts, as evidenced by contracture and graft necrosis. Additional skin graft images are presented in fig. S3. Photo credit: James D. Fisher, University of Pittsburgh.

Recruitment-MP treatment confers systemic donor-specific tolerance to hindlimb recipients

To test whether Recruitment-MP could impart donor antigen–specific dominant tolerance, animals with long-term surviving allografts (>200 days) were challenged with nonvascularized skin allografts from LEW (syngeneic), BN (donor), and WF (third party). These animals received no further immunosuppression or microparticle treatment beyond POD 21. All three animals acutely rejected skin grafts from WF animals, as evidenced by a lack of graft take, characterized by necrosis, wound contraction, and scarring. However, animals accepted both LEW and BN grafts, with minimal wound contracture and eventual hair regrowth (Fig. 6, B and C).

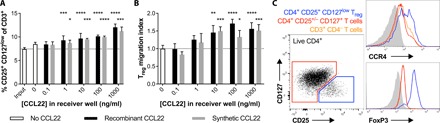

Fig. 6. Recombinant or synthetic CCL22 induces preferential migration of human Treg to enrich Treg frequency.

Total CD3+ T cells were isolated from human PBMCs and allowed to migrate through transwell membranes toward different concentrations of recombinant or synthetic CCL22. After 2 hours, migrating cells were collected in the receiver wells and analyzed by flow cytometry (N = 4 wells per group; means ± SD). (A) Frequency of CD4+ CD25+ CD127low Treg among total migrating T cells. Dotted line represents the average Treg frequency among the total CD3+ T cell population before migration (“input”). Groups were compared by two-way independent ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s test of dose effect. Significant differences compared to the starting population (input) are indicated by *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, or ****P < 0.0001. (B) Treg migration index represents the number of CD4+ CD25+ CD127low Treg that migrated toward CCL22, normalized to the average number of Treg that spontaneously migrated in the absence of chemokine. Groups were compared by two-way independent ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s test of dose effect. Significant differences compared to the no CCL22 control group are indicated by *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, or ****P < 0.0001. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots confirming specific FoxP3 expression by CD4+ CD25+ CD127low Treg (blue) and showing greater CCR4 expression by Treg (blue) than conventional CD4+ T cells (red) and CD3+ CD4− T cells (orange).

Synthetic and recombinant CCL22 induce selective migration of human Treg

Given promising results with CCL22 delivery in the rat hindlimb VCA model, we sought to determine whether chemically synthesized CCL22 (with potential advantages for clinical translation) could serve as an alternative to recombinant CCL22 to selectively enrich human Treg. Migration of human CD3+ T cells from peripheral blood toward human CCL22 was evaluated using in vitro transwell migration assays. Both recombinant and synthetic CCL22 promoted specific migration of human CD4+ CD25+ CD127low T cells from a diverse pool of total CD3+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6), and selective FoxP3 expression by these cells confirmed their identity as Treg (Fig. 6C). Compared to CD4+ CD25+/− CD127+ helper T cells and CD3+ CD4− T cells, which include CD8+ T cells and a smaller population of γδ T cells, Treg expressed higher levels of CCR4 (Fig. 6C). This differential expression of CCR4 resulted in enrichment of Treg in the migrating fraction (Fig. 6A), with Treg frequencies among migrating T cells enhanced by as much as 1.6-fold compared to starting populations of total CD3+ T cells. While the greatest Treg enrichment corresponded to the greatest CCL22 concentration (1000 ng/ml) (Fig. 6A), Treg migration indices, which represent CCL22-induced Treg migration, appear to peak at a lower concentration of 100 ng/ml (Fig. 6B). Human Treg migrated comparably toward both recombinant and synthetic CCL22.

DISCUSSION

The largest issue facing the field of transplant immunology is graft loss due to immune-mediated rejection that necessitates the need for lifelong anti-rejection drug treatment. These problems are exacerbated in the emerging field of VCA, as grafts are not viewed as life-saving interventions, raising ethical issues concerning the risk/reward ratio of such procedures. As such, to allow for the routine and widespread use of VCA, it is of paramount importance to develop alternative strategies to limit or even eliminate the need for chronic, systemic immunosuppression.

Over the past decade, mounting evidence has accumulated, implicating a pivotal role for Treg in the prevention of allograft rejection and the induction of tolerance (5, 6, 20, 21). Given the substantial challenges with ex vivo–expanded Treg therapies (22), it is desirable to develop an alternative strategy that is capable of harnessing the highly sophisticated immunoregulatory potential of a patient’s endogenous Treg. Some malignant cells reportedly secrete the Treg-recruiting chemokine CCL22 to create a proregulatory environment in the tumor milieu (12). Previous attempts to mimic this phenomenon have involved transduction of pancreatic islet cells with adenovirus expressing CCL22, as an experimental treatment tested in murine models of autoimmune diabetes and islet allotransplantation (23, 24). In the present study, we used synthetic, biodegradable Recruitment-MP to recruit endogenous Treg to VCA tissues to promote allograft tolerance. While recruitment of CCR4-expressing Treg is a key mechanism through which CCL22 suppresses inflammation, other complementary functions of CCL22 have been elucidated more recently and may also contribute to allograft tolerance. In particular, CCL22 can also recruit invariant natural killer T cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs), as well as enhance expression of Treg factors, such as CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen–4), which, in turn, induce production of suppressive indoleamine dioxygenase by DCs (25, 26).

Here, a rat hindlimb model of VCA was used, using BN rats as donors and LEW rats as recipients. All animals received the same short-course baseline immunosuppression protocol consisting of two doses of ALS induction therapy and 21 days of FK506 maintenance therapy (fig. S1C). Our rationale for including a short course of immunosuppression was twofold: (i) to ensure that Recruitment-MP were given sufficient time to establish an adequate gradient of CCL22 and (ii) to evaluate whether the Recruitment-MP could be used together with an immunosuppression protocol resembling that used clinically (2). While FK506 suppresses IL-2 production, resulting in suppression of conventional T cell activity, there is a paucity of information regarding the effect of FK506 on regulatory populations (27). Some studies even report favorable effects of FK506 on Treg induction and function (28, 29). Last, while effective at depleting host lymphocytes, ALS reportedly spares regulatory cells (30) and could serve to compliment the effect of Recruitment-MP.

Because the effectiveness of Recruitment-MP hinges upon the generation of a gradient of CCL22 chemokine to recruit Treg, three doses of Recruitment-MP (9, 50, and 100 mg) were tested to determine an effective formulation for sufficient directional migration of Treg to the transplanted limb. If the concentration of CCL22 is too high, chemokine receptor saturation and/or internalization can inhibit Treg chemotaxis (31, 32). Conversely, if the concentration of CCL22 is too low, then it may not be possible to generate a gradient capable of affecting and sustaining the migration of Treg distant from the site of Recruitment-MP placement (33). Our data show that treatment with only two doses of 50 mg of Recruitment-MP (at POD 0 and 21) can prolong hindlimb allograft survival when compared to the 9- and 100-mg doses (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, a formulation capable of sustaining release of CCL22 was required, as a subcutaneous bolus injection of CCL22 did not prolong graft survival (Fig. 1A). Given the lack of long-term survival with the high and low doses of Recruitment-MP or with a bolus of CCL22, we did not quantify in vivo Treg recruitment to the allograft for those treatments; however, such studies could provide insight into how Recruitment-MP dose affects in vivo Treg recruitment, as well as what degree of local Treg enrichment is necessary for allograft survival. Last, it should be noted that the tolerogenic effects seen with Recruitment-MP were due to local release of CCL22 on the order of nanogram per kilogram per day, as opposed to conventional immunosuppression that requires up to milligrams of drug per day, administered systemically.

Flow cytometric analysis of lymph nodes from long-term surviving Recruitment-MP VCA recipients demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg in allograft draining lymph nodes than in nondraining lymph nodes and draining lymph nodes of rejecting animals (Fig. 4A). Recruitment-MP also increased the proportion of Treg among total T cells in allograft skin around the time that allografts rejected in control animals (Fig. 2C). These findings further support our hypothesis that Recruitment-MP can promote VCA tolerance via local enrichment of Treg via chemotactic recruitment. Furthermore, increased percentages of functional Treg were correlated with a concomitant decrease in the incidence of CD4+IFN-γ+ T helper 1 (TH1) effector T cells in draining lymph nodes of long-term surviving allografts (Fig. 4B). Not unsurprisingly, there was an increase in the incidence of TH1 cells in draining lymph nodes of rejecting animals (Fig. 4B). In addition to reducing inflammation at the cellular level, Recruitment-MP substantially reduced inflammation at the RNA level in both intragraft tissue and in draining lymph nodes. Expression of TNF-α, Perforin-1, Serglycin, and IL-17 was decreased in draining lymph nodes and intragraft skin tissue of long-term survivors when compared to actively rejecting animals (Fig. 3). This result is not surprising, as Treg are known to inhibit TH1/TH17 T cells and their production of proinflammatory cytokines (6, 9, 34, 35). Collectively, results at the macroscopic, microscopic, and cellular level indicate that Recruitment-MP can achieve anti-donor hyporesponsiveness via enrichment of suppressive Treg.

Treg were further implicated as an essential component of VCA tolerance by examining the function of Tconv and Treg ex vivo. Recruitment-MP did not alter the intrinsic proliferative capacity and alloreactivity of Tconv, as CD4+CD25− Tconv from long-term survivors showed no immune hyporesponsiveness toward donor stimulation when compared to CD4+CD25− Tconv from naïve rats (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, not only were Treg populations enriched in skin and draining lymph nodes from Recruitment-MP–treated allografts, but also Treg isolated from long-term survivors were also more effective at suppressing donor antigen–induced Tconv proliferation than Treg from naïve animals (Fig. 4D). This suggests that Recruitment-MP impart donor-specific suppressive function to VCA recipients with long-term surviving grafts. We also show that Treg from long-term survivors are more effective at suppressing BN (donor)–induced proliferation than WF (third party)–induced proliferation, suggesting an antigen-specific inhibitory function of the Treg isolated from Recruitment-MP–treated recipients (Fig. 5A). Collectively, these results suggest that allograft tolerance induced by Recruitment-MP is mediated by Treg.

As a final step to ascertain donor specificity, full-thickness skin grafts were grafted from both BN (donor) and WF (third party) to Recruitment-MP–treated rats with long-surviving grafts. These rats accepted skin grafts from BN donors, as evidenced by growth of brown fur from previously shaved skin grafts, which would not occur in nonviable grafts (Fig. 5C and fig. S3A). Furthermore, third-party (WF) grafts failed to take status 14 days after skin grafting, as evidenced by graft necrosis (fig. S3B). The WF grafts eventually sloughed off as eschars, leaving a healing wound bed (Fig. 5C). This in vivo test of antigen specificity mirrored the in vitro results, with all animals accepting donor (BN) skin grafts but failing to accept third-party (WF) grafts (Fig. 5, B and C).

While the data presented here suggest that Recruitment-MP can establish donor-specific tolerance in rodents receiving hindlimb transplants by enriching Treg locally, there are a few limitations worth noting. Rats were used instead of mice because of their comparatively larger vasculature, which reduces the technical challenges associated with microsurgical anastomoses of blood vessels; however, biochemical and genetic tools (e.g., knockout or reporter strains) for more extensive mechanistic investigation are less readily available for rats. For example, without specific transgenic animal models (e.g., FoxP3cre × CCR4flox mice, in which CCR4 would be selectively deleted only in Treg, or CCR4−/− mice with targeted CCR4 transgene expression in FoxP3+ cells), we cannot rule out the possibility that some other CCR4+ cells might also be recruited to the allograft and contribute to allograft tolerance. Tracking Treg in allografts throughout the course of transplantation, Recruitment-MP treatment, and long-term survival (or allograft rejection) also remains a challenge in the rat hindlimb VCA model and would require either costly serial sacrifice and tissue harvesting or serial in vivo imaging of animals with fluorescent or luminescent reporter Treg (available for mice but not rats).

As the next step toward translation, we are beginning to test Recruitment-MP in a well-established large-animal VCA flap model in outbred swine. These preclinical studies will provide critical information with respect to dose scaling of Recruitment-MP for human trials. Swine are also a suitable species for translational studies as they share anatomic, physiologic, and immunologic similarities with humans. We previously demonstrated that microparticles releasing recombinant human CCL22 locally recruit Treg in vivo in a large animal (canine) model, providing a basis for scaling and efficacy in larger animal models (17). The probability of favorable safety data in humans is also dramatically increased by the extremely low doses to be released locally (nanogram per kilogram per day).

Although preferential chemotaxis of human Treg toward recombinant CCL22 has been reported previously (13), we have now confirmed that synthetic human CCL22 exhibits comparable Treg-specific chemotactic potency (Fig. 6), suggesting that either could be used for human Recruitment-MP. From a translational perspective, synthetic chemokines produced by solid-phase peptide synthesis (36) offer several advantages over recombinant chemokines produced by engineered microbial, mammalian, or plant cells. Cell-free solid-phase synthesis using automated peptide synthesizer equipment can substantially accelerate the production of cGMP (current good manufacturing practice)–grade chemokines with lower costs than recombinant chemokines. Furthermore, for regulatory purposes, recombinant CCL22 would be treated as a biologic or new molecular entity, while synthetic CCL22 would more likely be treated as a drug or new chemical entity. As such, synthetic CCL22 would be subject to regulatory provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act but not additional regulations of the Public Health Service (PHS) Act, which also applies to biologics. The more complex manufacturing and regulatory pathway for recombinant CCL22, however, could be at least partially offset by an extended 12-year market exclusivity for biologics following U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval [PHS Act, Section 351(a)] compared to 5-year exclusivity (21 CFR 314.108) for a new chemical entity (e.g., synthetic CCL22). Thus, considerations for clinical translation and commercialization of protein therapeutics, like Recruitment-MP, should weigh the benefits of faster and more cost-effective development of a synthetic protein against the seven additional years of market exclusivity for a recombinant protein.

In summary, the current approach to inducing allograft tolerance by Treg recruitment via local sustained release of a chemokine (CCL22) represents a marked departure from conventional immunosuppression regimens for VCA, as well as many recent experimental approaches involving sustained and/or local delivery of the same immunosuppressive agents currently administered systemically in the clinic (37, 38). By inducing dominant alloantigen-specific tolerance without suppressing systemic immune responses (as evidenced by functional conventional T cells in long-term surviving allograft recipients treated with two doses of Recruitment-MP), our novel therapeutic approach has the potential to prevent allograft rejection and avoid patient compliance and toxicity issues associated with current long-term immunosuppression regimens, which also leave patients immunocompromised and unable to fight infections and malignancies. Last, the translational implications of an immunosuppression-free tolerance inducing regimen extend beyond VCA. Recruitment-MP may also prevent rejection of allogeneic skin grafts used to treat third-degree burns or cover exposed bone, hardware, or tendons, without native morbidity, or in cases of insufficient autologous donor sites. Ultimately, Recruitment-MP may have even broader relevance in acute or chronic inflammatory and autoimmune pathologies, such as rheumatoid arthritis, where available treatments are also limited by their global immunosuppressive or off-target toxic side effects.

METHODS

Animals

Six- to 8-week-old male LEW, BN, and WF rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used. Animals were maintained under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocol in a specific pathogen–free environment at the University of Pittsburgh.

Hindlimb transplantation

Using techniques developed in the University of Pittsburgh’s Department of Plastic Surgery (39), hindlimbs from donor BN rats were transplanted orthotopically to recipient LEW rats. Briefly, donor femoral vessels were anastomosed end-to-end to recipient femoral vessels using 10-0 nylon sutures, and femoral osteosynthesis was performed with an 18-gauge intramedullary rod. Attachment of muscles and skin closure were achieved with simple interrupted sutures. Surgical time was approximately 2 to 3 hours. Anesthesia was achieved perioperatively with inhaled isoflurane, and buprenorphine was used for analgesia.

Recruitment-MP fabrication and characterization

PLGA MPs containing recombinant mouse CCL22 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were prepared using a standard water-oil-water double emulsion procedure, as described (16). Briefly, PLGA (RG502H; Boehringer Ingelheim, Petersburgh, VA) MP were prepared by mixing 200 μl of an aqueous solution containing 25 μg of rmCCL22 and 2 mg of bovine serum albumin and 15 mmol NaCl with 200 mg of polymer dissolved in 4 ml of dichloromethane. The first water-in-oil emulsion was prepared by sonicating this solution for 10 s. The second oil-in-water emulsion was prepared by homogenizing (Silverson L4RT-A) this solution with 60 ml of an aqueous solution of 2% polyvinyl alcohol (molecular weight, ~25,000 Da; 98% hydrolyzed; PolySciences, Warrington, PA) for 60 s at 3000 rpm. This solution was then mixed with 1% polyvinyl alcohol and placed on a stir plate agitator for 3 hours to allow the dichloromethane to evaporate. The microparticles were then collected and washed four times in deionized (DI) water, to remove residual polyvinyl alcohol, before being resuspended in 5 ml of DI water, frozen, and lyophilized for 72 hours (VirTis BenchTop K freeze dryer, Gardiner, NY; operating at 100 mtorr).

Surface characterization of microparticles was conducted using scanning electron microscopy (JEOL JSM-6510LV/LGS), and microparticle size distribution was determined by volume impedance measurements on a Beckman Coulter counter (Multisizer 3, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). CCL22 release from microparticles was determined by suspending 7 to 10 mg of microparticles in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline placed on an end-to-end rotator at 37°C. CCL22 release sampling was conducted by centrifuging microparticles and removing the supernatant for CCL22 quantification using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (16).

Study design and groups

All hindlimb recipients in all groups received the same baseline immunosuppression protocol consisting of 21 days of tacrolimus (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg per day, injected intraperitoneally from the time of transplant. Rats also received two doses of rabbit ALS (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY) injected intraperitoneally on day −4 and POD 1 (fig. S1C). MP were injected via an 18-gauge needle after subcutaneously undermining dermal tissue to allow for even spreading of the particles. Further, MP were injected in the lateral aspect of the transplanted limb (unless otherwise noted) immediately following hindlimb transplantation and again on POD 21. Animals given transplants were allocated into groups consisting of the following treatments: (i) FK506/ALS baseline immunosuppression only (N = 4); (ii) 9 mg of Recruitment-MP (10 mg/ml; N = 6); (iii) 50 mg of Recruitment-MP (50 mg/ml; N = 8); (iv) 100 mg of Recruitment-MP (50 mg/ml; N = 6); (v) 50 mg of blank MP (N = 3); (vi) soluble CCL22 assuming 100% encapsulation efficiency of group 3 (N = 4); (vii) 50 mg of Recruitment-MP injected in the contralateral, native naïve (nontransplanted) limb (N = 4).

Hindlimb allograft monitoring

To assess rejection, hindlimbs were monitored daily and scored for rejection (appearance grading) based on physical examination (39). Limbs were given a daily score using the following scale: grade 0 (no rejection), grade I (edema), grade II (erythema and edema), grade III (epidermolysis), and grade IV (necrosis and “mummification”). Grafts were considered rejected when displaying signs of progressive grade III rejection.

Graft histology

Skin and muscle samples were obtained from the transplanted limbs at their experimental end point: progressive grade III rejection, early nonrejecting (POD 29 to 33), or long-term survival (>200 days). Samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for microscopic examination of tissue architecture and mononuclear cell infiltration.

Flow cytometric analysis

Draining and nondraining (contralateral) inguinal lymph nodes were harvested at the experimental end point (progressive grade III rejection or long-term survival >200 days). Lymph nodes were then processed to form single-cell suspensions. Cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies for CD4 (clone OX-35), CD25 (OX-39), FoxP3 (FJK-16s), and IFN-γ (DB-1) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA; eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) was used for intracellular staining. Before IFN-γ cytokine staining, cells were cultured overnight with Cell Stimulation Cocktail (plus protein transport inhibitor; eBioscience). Skin samples (1 cm × 1 cm) were cut into thin strips for enzymatic digestion in culture medium supplemented with collagenase D (1 mg/ml) and deoxyribonuclease (DNase) (1 mg/ml). Tissue was incubated for 2 hours at 37°C and 100 rpm shaking and then mechanically dissociated through 70-μm nylon filters. Cells were stained with antibodies for CD4 (OX-35), CD8a (OX-8), CD45 (OX-1), and FoxP3 (FJK-16s), as well as Fc block (anti-CD32, D34-485) and a fixable viability dye (eBioscience). Stained lymph node and skin cells were analyzed on a BD LSR Fortessa cytometer, and CountBright Absolute Counting Beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were added to skin cell suspensions to determine total cell counts. Results were analyzed using FlowJo (Ashland, OR).

Gene expression and PCR

Gene expression profiles of inflammatory markers were evaluated in the skin and lymph nodes of long-term graft survivors, actively rejecting animals, and naïve rats. Total RNA was extracted from samples using TRI Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. For each reverse transcriptase assay, 4 μg of RNA was converted to complementary DNA using a QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was then performed using VeriQuest Probe qPCR Mastermix, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with 5′ nuclease PrimeTime qPCR assays specific for IFN-γ (Rn00594078_m1 Dye: VIC-MGB_PL), TNF-α (Rn99999017_m1 Dye: VIC-MGB_PL), Perforin-1 (Rn00569095_m1 Dye: VIC-MGB_PL), Serglycin (Rn00571605_m1 Dye: VIC-MGB_PL), IL-17 (Rn01757168_m1 Dye: VIC-MGB_PL), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; endogenous control, Rn99999916_s1). Duplex reactions (target gene + GAPDH) were run and analyzed on the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System. Relative fold changes of IFN-γ, TNF-α, Perforin-1, Serglycin, and IL-17 expression were calculated and normalized based on the 2−ΔΔCT method, and then further normalized to normal control. Skin biopsies from naïve animals or contralateral limbs served as untreated controls.

Cell proliferation and suppression assays

Spleens from rats with long-surviving hindlimb grafts and naïve LEW rats were processed into single-cell suspensions. Red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). CD4+ T cells were isolated using CD4 T cell enrichment columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). CD4+ enriched cells were then stained with anti-CD4 (OX-35) and anti-CD25 (OX-39). CD4+CD25− (Tconv) and CD4+CD25hi (Treg) populations were sorted using a BD FACSAria cell sorter. To assess proliferative function, CD4+CD25− (Tconv) from long-term surviving and naïve rats were stained with violet proliferation dye (VPD450; BD Biosciences) and each was cocultured/stimulated with irradiated splenocytes harvested from donor strain rats at 2:1 Tconv:stimulators. At the end of the 7-day MLR period, proliferation was measured via VPD450 dilution by flow cytometry. The proliferative capacity of Tconv from long-term surviving rats was normalized to that of naïve rats.

To quantify the suppressive cell function of CD4+CD25hi (Treg) isolated from long-term surviving and normal control rats, we tested their ability to suppress Tconv proliferation in MLR. CD4+CD25− Tconv from naïve rats were stained with VPD450 and cocultured/stimulated with irradiated splenocytes from BN rats and CD4+CD25hi Treg from either long-term surviving or naïve rats at 2:1 Tconv:Treg. At the end of the 7-day culture period, proliferation was measured via VPD450 dilution by flow cytometry. Percent suppression was calculated using the following formula: {1 – [(% Proliferation of naïve Tconv cultured with BN splenocytes and Treg)/(% Proliferation of naïve Tconv cultured with BN splenocytes)]} × 100%.

MLRs were also set up to test for antigen specificity of the CD4+CD25hi Treg isolated from long-term surviving rats. CD4+CD25− Tconv from naïve rats were stained with VPD450 and stimulated with either BN or WF (third party) irradiated splenocytes in the presence of CD4+CD25hi Treg isolated from long-term surviving rats. At the end of the 7-day culture period, proliferation was measured via VPD450 dilution using FlowJo (Ashland, OR). Percent suppression was calculated using the following formula: {1 – [(% Proliferation of naïve Tconv cultured with BN or WF splenocytes and Treg)/(% Proliferation of naïve Tconv cultured with BN or WF splenocytes)]} × 100%.

Full-thickness secondary skin grafting

Donor antigen–specific tolerance was assessed in vivo in long-surviving graft recipients (>200 days) from the 50-mg Recruitment-MP group via skin graft challenge. Skin allografts were harvested from normal donor strain (BN) or third-party strain rats (WF) and transplanted to the dorsal thoracic area of long-term survivors >200 days after VCA. Grafts were supported in place with xeroform and surgical gauze for 5 days and subsequently evaluated daily for signs of rejection. Rejection was defined as 80% necrosis of the skin graft.

Human CCL22 T cell migration and Treg enrichment assay

Healthy donor human peripheral blood was obtained from the Central Blood Bank (Pittsburgh, PA), and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque Plus (1.077 g/ml; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) gradient centrifugation. Total CD3+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs by immunomagnetic negative selection with an EasySep Human T Cell Isolation kit (StemCell Technologies, Cambridge, MA). Chemotaxis assays were conducted in 24-well plates with 5-μm pore polycarbonate transwell filters (Corning Costar, Corning, NY), as previously reported (13). Serum-free AIM V medium (600 μl; Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing recombinant human CCL22 (0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, or 1000 ng/ml) (R&D Systems), or synthetic human CCL22 (Almac, Souderton, PA), was added to the lower receiver wells. T cells suspended in serum-free AIM V medium were added to the top chambers of the transwells (100 μl, 5 × 105 cells per well). For total cell “input” controls, cells were placed directly in receiver wells. After incubating at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 hours, migrating cells in the lower wells were recovered and transferred to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) tubes for staining. Cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies for CD4 (RPA-T4; BD Biosciences), CD25 (2A3; BD Biosciences), CD127 (hIL-7R-M21; BD Biosciences), and a fixable viability dye (eBioscience). Some cells were also stained for CCR4 (1G1; BD Biosciences) and FoxP3 (236A/E7; eBioscience), or mouse IgG1,κ isotype controls, using the eBioscience FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set. Immediately before analysis on a BD LSR II flow cytometer, CountBright Absolute Counting Beads were added to each tube. Frequencies of Treg (CD4+ CD25+ CD127low) in the migrating populations were calculated. To determine total numbers of migrating T cells, cell counts were normalized to total counting beads. Treg chemotaxis migration indices were calculated by normalizing numbers of Treg migrating in the presence of CCL22 to the average number of spontaneously migrating Treg in the absence of CCL22.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism v8. All data are expressed as means ± SD, and significant differences between experimental groups were determined by two-tailed Student’s t test, Welch’s t test, or Mann-Whitney U test for two independent samples, or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests for comparison of multiple groups. For human Treg migration assays with two types of CCL22 and multiple doses, results were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s pairwise comparisons for dose effect. A one-sample t test was used to compare fold changes in an experimental group to a value of one, and the effects of various treatments on VCA survival were analyzed using a log-rank test. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Flow cytometry analyses and FACS sorting were conducted at the University of Pittsburgh’s Unified Flow Core and benefitted from a Special BD LSR Fortessa funded by the NIH (1-S10-OD011925-01). We thank A. MacIntyre and D. Falkner for assistance with FACS sorting. Histological services were provided by the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine Histology Core. Funding: This research was funded by the NIH NIAID (R01-AI118777 and U19-AI131453 to A.W.T. and R01-HL122489 to H.R.T.), NIH NIDCR (R01-DE021058 to S.R.L.), DoD CDMRP (W81XWH-15-2-0027 to A.W.T. and W81XWH-15-1-0244 to S.R.L. and V.S.G.), and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation (to S.R.L.). J.D.F. was supported by a fellowship from the NIH NIAID (T32-AI074490), and SCB was supported by a fellowship from the NIH NCI (T32-CA175294). Author contributions: J.D.F. and S.R.L. conceptualized and designed the study. J.D.F., S.C.B., A.M.A., W.Z., A.P.A., Y.K., and J.L. conducted experiments. J.D.F., J.L., and W.Z. performed T cell phenotype and function experiments and analyzed the resulting data. S.C.B. performed qRT-PCR, skin flow cytometry, and human Treg migration experiments; interpreted the resulting data; and contributed to histological analyses. A.M.A. and J.D.F. performed hindlimb transplants, administered microparticles and immunosuppression, monitored the status of allografts, and harvested tissues for analyses. J.D.F., S.C.B., V.S.G., and S.R.L. wrote the manuscript, with additional discussion and contributions from H.R.T., A.W.T., and M.G.S. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/11/eaax8429/DC1

Fig. S1. Characterization of Recruitment-MP and experimental timeline for hindlimb transplantation.

Fig. S2. Skin flow cytometry gating strategy used for Fig. 2C.

Fig. S3. Representative images of a hindlimb VCA recipient challenged with LEW, BN, and WF nonvascularized skin grafts.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Cavadas P. C., Ibáñez J., Thione A., Alfaro L., Bilateral trans-humeral arm transplantation: Result at 2 years. Am. J. Transplant. 11, 1085–1090 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petruzzo P., Lanzetta M., Dubernard J.-M., Landin L., Cavadas P., Margreiter R., Schneeberger S., Breidenbach W., Kaufman C., Jablecki J., Schuind F., Dumontier C., The international registry on hand and composite tissue transplantation. Transplantation 90, 1590–1594 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morelon E., Kanitakis J., Petruzzo P., Immunological issues in clinical composite tissue allotransplantation: Where do we stand today? Transplantation 93, 855–859 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley J. L., June C. H., Blazar B. R., Human T regulatory cell therapy: Take a billion or so and call me in the morning. Immunity 30, 656–665 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Shimizu J., Yamazaki S., Sakihama T., Itoh M., Kuniyasu Y., Nomura T., Toda M., Takahashi T., Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: Their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 182, 18–32 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakaguchi S., Yamaguchi T., Nomura T., Ono M., Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 133, 775–787 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilate A. M., Lafaille J. J., Induced CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in immune tolerance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 733–758 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safinia N., Sagoo P., Lechler R., Lombardi G., Adoptive regulatory T cell therapy: Challenges in clinical transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 15, 427–434 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sather B. D., Treuting P., Perdue N., Miazgowicz M., Fontenot J. D., Rudensky A. Y., Campbell D. J., Altering the distribution of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells results in tissue-specific inflammatory disease. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1335–1347 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang Q., Bluestone J. A., The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: A jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat. Immunol. 9, 239–244 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wing K., Sakaguchi S., Regulatory T cells exert checks and balances on self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nat. Immunol. 11, 7–13 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curiel T. J., Coukos G., Zou L., Alvarez X., Cheng P., Mottram P., Evdemon-Hogan M., Conejo-Garcia J. R., Zhang L., Burow M., Zhu Y., Wei S., Kryczek I., Daniel B., Gordon A., Myers L., Lackner A., Disis M. L., Knutson K. L., Chen L., Zou W., Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 10, 942–949 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iellem A., Mariani M., Lang R., Recalde H., Panina-Bordignon P., Sinigaglia F., D’Ambrosio D., Unique chemotactic response profile and specific expression of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 194, 847–853 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishida T., Ishii T., Inagaki A., Yano H., Komatsu H., Iida S., Inagaki H., Ueda R., Specific recruitment of CC chemokine receptor 4–positive regulatory T cells in Hodgkin lymphoma fosters immune privilege. Cancer Res. 66, 5716–5722 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mailloux A. W., Young M. R., NK-dependent increases in CCL22 secretion selectively recruits regulatory T cells to the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunol. 182, 2753–2765 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jhunjhunwala S., Raimondi G., Glowacki A. J., Hall S. J., Maskarinec D., Thorne S. H., Thomson A. W., Little S. R., Bioinspired controlled release of CCL22 recruits regulatory T cells in vivo. Adv. Mater. 24, 4735–4738 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glowacki A. J., Yoshizawa S., Jhunjhunwala S., Vieira A. E., Garlet G. P., Sfeir C., Little S. R., Prevention of inflammation-mediated bone loss in murine and canine periodontal disease via recruitment of regulatory lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18525–18530 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratay M. L., Glowacki A. J., Balmert S. C., Acharya A. P., Polat J., Andrews L. P., Fedorchak M. V., Schuman J. S., Vignali D. A. A., Little S. R., Treg-recruiting microspheres prevent inflammation in a murine model of dry eye disease. J. Control. Release 258, 208–217 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chadha R., Leonard D. A., Kurtz J. M., Cetrulo C. L. Jr., The unique immunobiology of the skin: Implications for tolerance of vascularized composite allografts. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 19, 566–572 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozulic L. D., Wen Y., Xu H., Ildstad S. T., Evidence that FoxP3+ regulatory T cells may play a role in promoting long-term acceptance of composite tissue allotransplants. Transplantation 91, 908–915 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood K. J., Bushell A., Hester J., Regulatory immune cells in transplantation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 417–430 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trzonkowski P., Bacchetta R., Battaglia M., Berglund D., Bohnenkamp H. R., ten Brinke A., Bushell A., Cools N., Geissler E. K., Gregori S., van Ham S. M., Hilkens C., Hutchinson J. A., Lombardi G., Madrigal J. A., Marek-Trzonkowska N., Martinez-Caceres E. M., Roncarolo M. G., Sanchez-Ramon S., Saudemont A., Sawitzki B., Hurdles in therapy with regulatory T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 304ps318 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montane J., Bischoff L., Soukhatcheva G., Dai D. L., Hardenberg G., Levings M. K., Orban P. C., Kieffer T. J., Tan R., Verchere C. B., Prevention of murine autoimmune diabetes by CCL22-mediated Treg recruitment to the pancreatic islets. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3024–3028 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montane J., Obach M., Alvarez S., Bischoff L., Dai D. L., Soukhatcheva G., Priatel J. J., Hardenberg G., Levings M. K., Tan R., Orban P. C., Verchere C. B., CCL22 prevents rejection of mouse islet allografts and induces donor-specific tolerance. Cell Transplant. 24, 2143–2154 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bischoff L., Alvarez S., Dai D. L., Soukhatcheva G., Orban P. C., Verchere C. B., Cellular mechanisms of CCL22-mediated attenuation of autoimmune diabetes. J. Immunol. 194, 3054–3064 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapp M., Wintergerst M. W. M., Kunz W. G., Vetter V. K., Knott M. M. L., Lisowski D., Haubner S., Moder S., Thaler R., Eiber S., Meyer B., Röhrle N., Piseddu I., Grassmann S., Layritz P., Kühnemuth B., Stutte S., Bourquin C., von Andrian U. H., Endres S., Anz D., CCL22 controls immunity by promoting regulatory T cell communication with dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1170–1181 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burrell B. E., Nakayama Y., Xu J., Brinkman C. C., Bromberg J. S., Regulatory T cell induction, migration, and function in transplantation. J. Immunol. 189, 4705–4711 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z., Shi B., Jin H., Xiao L., Chen Y., Qian Y., Low-dose of tacrolimus favors the induction of functional CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in solid-organ transplantation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 9, 564–569 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sewgobind V. D., van der Laan L. J. W., Kho M. M. L., Kraaijeveld R., Korevaar S. S., Mol W., Weimar W., Baan C. C., The calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus allows the induction of functional CD4CD25 regulatory T cells by rabbit anti-thymocyte globulins. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 161, 364–377 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minamimura K., Gao W., Maki T., CD4+ regulatory T cells are spared from deletion by antilymphocyte serum, a polyclonal anti-T cell antibody. J. Immunol. 176, 4125–4132 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moghe P. V., Nelson R. D., Tranquillo R. T., Cytokine-stimulated chemotaxis of human neutrophils in a 3-D conjoined fibrin gel assay. J. Immunol. Methods 180, 193–211 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mariani M., Lang R., Binda E., Panina-Bordignon P., D’Ambrosio D., Dominance of CCL22 over CCL17 in induction of chemokine receptor CCR4 desensitization and internalization on human Th2 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 231–240 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stone M. J., Hayward J. A., Huang C., Huma Z. E., Sanchez J., Mechanisms of regulation of the chemokine-receptor network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 342 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidt S., Segundo D. S., Chadha R., Wood K. J., The impact of Th17 cells on transplant rejection and the induction of tolerance. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 15, 456–461 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng H.-L., Shi B.-Y., Du G.-S., Wang Z., Changes in Th17 and IL-17 levels during acute rejection after mouse skin transplantation. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 18, 2720–2726 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsson B. L., Soellner M. B., Raines R. T., Chemical synthesis of proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34, 91–118 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gajanayake T., Olariu R., Leclère F. M., Dhayani A., Yang Z., Bongoni A. K., Banz Y., Constantinescu M. A., Karp J. M., Vemula P. K., Rieben R., Vögelin E., A single localized dose of enzyme-responsive hydrogel improves long-term survival of a vascularized composite allograft. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 249ra110 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unadkat J. V., Schnider J. T., Feturi F. G., Tsuji W., Bliley J. M., Venkataramanan R., Solari M. G., Marra K. G., Gorantla V. S., Spiess A. M., Single implantable FK506 disk prevents rejection in vascularized composite allotransplantation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 139, 403e–414e (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solari M. G., Washington K. M., Sacks J. M., Hautz T., Unadkat J. V., Horibe E. K., Venkataramanan R., Larregina A. T., Thomson A. W., Lee W. P. A., Daily topical tacrolimus therapy prevents skin rejection in a rodent hind limb allograft model. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 123, 17S–25S (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/11/eaax8429/DC1

Fig. S1. Characterization of Recruitment-MP and experimental timeline for hindlimb transplantation.

Fig. S2. Skin flow cytometry gating strategy used for Fig. 2C.

Fig. S3. Representative images of a hindlimb VCA recipient challenged with LEW, BN, and WF nonvascularized skin grafts.