Abstract

PURPOSE:

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) that assess how patients feel and function have potential for evaluating quality of care. Stakeholder recommendations for PRO-based performance measures (PMs) were elicited, and feasibility testing was conducted at six cancer centers.

METHODS:

Interviews were conducted with 124 stakeholders to determine priority symptoms and risk adjustment variables for PRO-PMs and perceived acceptability. Stakeholders included patients and advocates, caregivers, clinicians, administrators, and thought leaders. Feasibility testing was conducted in six cancer centers. Patients completed PROMs at home 5-15 days into a chemotherapy cycle. Feasibility was operationalized as ≥ 75% completed PROMs and ≥ 75% patient acceptability.

RESULTS:

Stakeholder priority PRO-PMs for systemic therapy were GI symptoms (diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting), depression/anxiety, pain, insomnia, fatigue, dyspnea, physical function, and neuropathy. Recommended risk adjusters included demographics, insurance type, cancer type, comorbidities, emetic risk, and difficulty paying bills. In feasibility testing, 653 patients enrolled (approximately 110 per site), and 607 (93%) completed PROMs, which indicated high feasibility for home collection. The majority of patients (470 of 607; 77%) completed PROMs without a reminder call, and 137 (23%) of 607 completed them after a reminder call. Most patients (72%) completed PROMs through web, 17% paper, or 2% interactive voice response (automated call that verbally asked patient questions). For acceptability, > 95% of patients found PROM items to be easy to understand and complete.

CONCLUSION:

Clinicians, patients, and other stakeholders agree that PMs that are based on how patients feel and function would be an important addition to quality measurement. This study also shows that PRO-PMs can be feasibly captured at home during systemic therapy and are acceptable to patients. PRO-PMs may add value to the portfolio of PMs as oncology transitions from fee-for-service payment models to performance-based care that emphasizes outcome measures.

INTRODUCTION

Performance measures (PMs) are standardized measures of clinical performance in health care settings.1,2 They are widely used in oncology care settings for benchmarking, quality improvement, and payment.2-5 Conventional PMs assess outcomes such as emergency department visits and patient experiences of care (eg, satisfaction with care).2-5 A notable gap is the patient perspective of symptom burden, quality of life, and physical function, which are measured with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).6 PRO-based PMs7-9 are in use in some medical specialties in the United States (eg, orthopedics),10,11 but PRO-PMs for oncology are in a more nascent stage.

Organizations that prioritize or endorse quality measures, such as ASCO,8 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS),12 the National Quality Forum,2,13 and the National Committee for Quality Assurance,14 have signaled their interest in using PRO-PMs in oncology. Systemic therapy, such as chemotherapy, is a natural starting point for developing PRO-PMs, given the high symptom burden15,16 and national guidelines.17,18 State and federal initiatives are under way to develop PRO-PMs for systemic therapy. For example, a state-based initiative (and collaborator on this study) called MN Community Measurement is testing PRO-PMs for nausea, pain, and constipation during chemotherapy and risk adjusters as part of its larger portfolio of PRO-PMs in multiple health conditions.19,20 Similarly, CMS is funding cooperative agreements to develop PRO-PMs for chemotherapy and palliative care in the areas of pain, fatigue, and quality of life.21 These contracts are currently field testing items and adjustment variables.

As the United States moves toward alternative payment models that emphasize health outcomes, such as the proposed Oncology Care First Model,22 PRO-PMs will become increasingly important for cancer centers to collect. It is unclear, however, what the most important symptoms and quality-of-life domains are to collect and which risk adjustment variables are most appropriate for PRO-PMs. In the current study, national stakeholder recommendations were elicited to prioritize PRO-PM domains for systemic therapy and risk adjustment variables. Feasibility and acceptability testing was then conducted at six cancer centers.

METHODS

Recruitment Sites (for Both Interviews and Feasibility Testing)

Six cancer centers in California, Connecticut, Florida, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Texas participated. Recruitment sites were chosen to represent different US regions, given variation in quality across the country,2,5 and diverse demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with cancer. Three cancer centers were academic, and three were community. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained at each cancer center. To protect the anonymity of cancer centers, they are identified by numbers.

Identification of Relevant Outcomes: Stakeholder Interviews and Literature Search

Stakeholder interviews were conducted to determine priority symptoms and risk adjustment variables for PRO-PMs. Stakeholders were ages ≥ 21 years and English speakers. Several recruitment methods were used for professional stakeholder groups. Site principal investigators sent e-mails to medical oncologists, nurses, administrators, and thought leaders at their cancer center. National thought leaders with expertise in PMs, PROMs, and/or cancer care delivery were also invited to participate.

Patients were purposively sampled from cancer centers, which is a qualitative research technique that involves strategic choices about which individuals to include in a study.23 In qualitative research, the purpose is to maximize the variety of responses rather than establish generalizable samples like in quantitative research.23 Our goal was to recruit at least 20% of the total patients who were ≥ 65 years of age, had an ethnic minority heritage, and/or had a high school education or less. Prior research has shown that at-risk groups may respond in different ways or may have more difficulty understanding health-related questionnaires24,25 and are at greater risk for poor outcomes.26 Caregiver inclusion criteria were adults with self-reported primary caregiving responsibilities for a chemotherapy patient receiving care at a recruitment site. Caregivers did not have to be linked to a patient participating in an interview. Patients and caregivers completed standardized items on age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and cancer type.27,28

Interview guides were informed by a literature review7-9,29-32 and tailored to each stakeholder group. Semistructured interview guides elicited recommendations for priority symptoms to test as PRO-PMs, risk adjustment variables, and optimal timing to administer PROMs at home during systemic therapy. We also asked stakeholders to describe what high-quality care meant to them and potential barriers and benefits to PRO-PMs. Interviews were conducted by phone and audio recorded. Consistent with gold standard methodology,23,33 we continued interviewing until conceptual saturation was reached within each group (ie, no new ideas emerged). Interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Transcripts were independently coded in Atlas.ti (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) by three coding teams using a common codebook.23,33 The codebook was developed on the basis of recommendations by the scientific advisory board (authors), literature search,7-9,29-32 initial readings of transcripts by the coders and research team, and codes for emerging/new themes. Coders pilot tested the initial codebook by independently coding two transcripts from patient and professional interviews and comparing them to coding done by research team members (A.M.S. and J.J.). A few concept definitions were revised, and the enhanced version was applied to remaining transcripts. Coding discrepancies were reconciled by consensus. Research team members and the scientific advisory board (authors) reviewed summary reports to discuss and confirm themes, and this process led to a final set of symptom domains.

Feasibility Testing

Questionnaire items for PROMs were selected on the basis of psychometric properties, validity and reliability of evidence, applicability to systemic cancer care, and public availability without licensing fees. Through this process, questionnaire items were selected from the PRO version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE),34,35 PROMIS,36,37 and a version of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PRO that assess physical function.38 Patients completed standardized items on demographics, insurance type, difficulty paying bills, and computer use as potential risk adjustment variables, as tested in prior studies.27,28 Patients also completed acceptability items that assessed comprehensibility and ease of use.27,28 The total number of items ranged from 32 to 36, depending on skip patterns. Items were loaded into an electronic system securely housed at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, which enabled PROMs to be completed by patients through web response or interactive voice response (IVR; automated call that verbally asked patient questions). A protocol was approved by the IRB of record at UNC and at each site.

Adults ages ≥ 21 years who were receiving systemic chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy (nonhormonal) for any type of cancer at the six recruitment sites were approached to participate and underwent informed consent. Participants needed to be able to write/speak English, Spanish, or Mandarin Chinese. Exclusions were inability to provide consent or ongoing participation in a clinical trial of an investigational drug. At enrollment, patients chose their preferred response mode (web response or IVR), and a brief tutorial was provided. Patients also selected their preferred language (English, Spanish, or Mandarin Chinese). The PROM was administered once, and participants were given a $20 gift card.

At enrollment, patients were educated that the PROM needed to be completed at home on days 5-15 of the treatment cycle. The 5-15-day time frame was chosen on the basis of interview recommendations and reviews that showed that symptoms are commonly experienced during this time frame.16,39 For each participant, a treatment cycle was identified after which they would self-report on PROM questions. Patients were commonly recruited in infusion centers, and thus their current cycle was typically used. This cycle could be at the initiation of a new treatment regimen or during the course of an existing regimen and could be during any line of treatment.

Starting on day 5 after initiation of the cycle, participants received an automated electronic prompt (either e-mail or IVR) to complete the PROM questions. The e-mail prompt provided a web link to the questionnaire, while IVR was an automated call to the patient. For patients who preferred not to complete questions electronically, paper questionnaires were offered. Participants received a daily electronic prompt until day 9 of the cycle or until the questionnaire was completed. If patients did not complete the questionnaire by day 10 after treatment, they received a human reminder by telephone or in person at a clinic encounter to encourage them to check their email for the link or to offer to administer the questionnaires verbally by interview. The questionnaire was considered to be missed if not completed by day 15. Feasibility was operationalized as > 75% completed PROMs and > 75% patient acceptability.32

Chart abstraction was used to collect the following clinical risk adjustment variables: cancer type, comorbid conditions, insurance type, oral or intravenous chemotherapy, drug regimen and emetic risk, and whether chemotherapy was curative or palliative. Sites raised concerns that stage would be difficult to obtain, and thus, a variable for curative or palliative chemotherapy was collected from the electronic health record as a proxy.

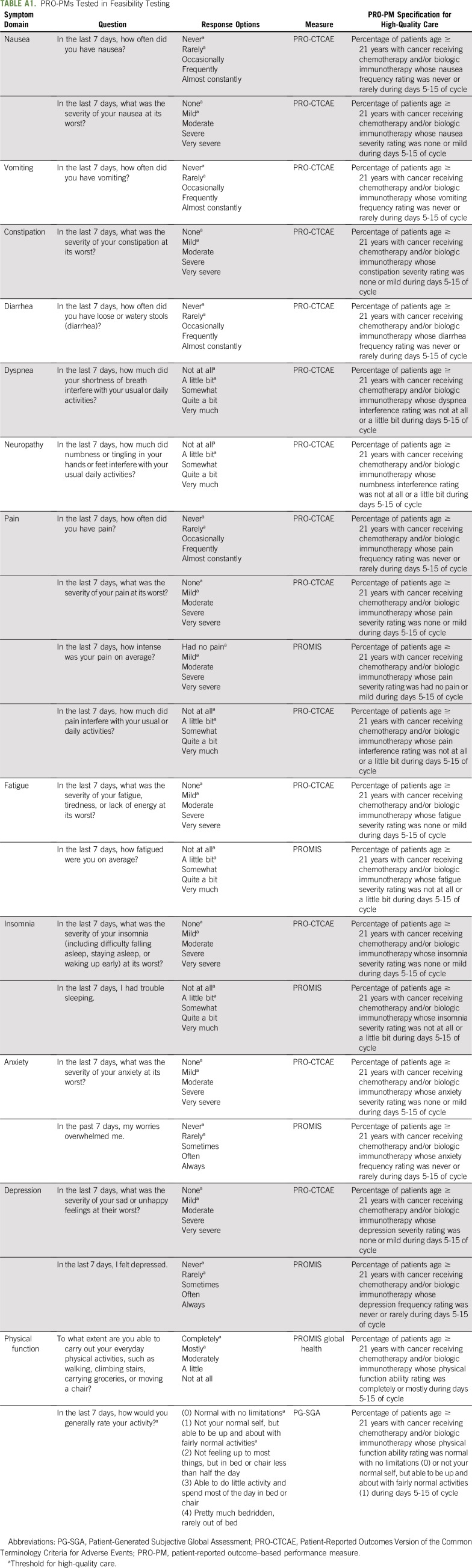

PM specifications were generated for each symptom (Appendix Table A1, online only). For example, a pain item from PRO-CTCAE34,35 is, “In the last 7 days, what was the severity of your pain at its worst (none, mild, moderate, severe, very severe)?” The corresponding PRO-PM specification for high-quality care was the proportion of adult patients in a participating cancer center receiving systemic cancer therapy whose pain severity rating was none or mild during days 5-15 of the cycle. Quantitative testing of these PRO-PMs will be reported elsewhere.

RESULTS

Interview Results

Members of each stakeholder group were included from participating cancer centers, advocate organizations, and national organizations. Clinicians (n = 11) were medical oncologists at recruitment sites. Administrators (n = 16) were medical directors, nursing leaders, and quality officers. Their educational backgrounds included seven MDs, five RNs (three also had PhDs), and four bachelor’s- or master’s-trained executives. Thought leaders (n = 15) included nine with PhDs, three MDs, two RNs, and one master’s-trained scientist.

Our purposive sampling targets for patients met or exceeded 20% representation for older age, minority, and low education. Of the 56 patients interviewed, 48% were women, 34% were age ≥ 65 years, 23% were ethnic minority, and 20% had a high school education or less. Cancer types included genitourinary (32%), GI (27%), breast (21%), and lung (20%). Primary caregivers (n = 21) were 71% female, 24% age ≥ 65 years, 76% non-Hispanic white, and 14% with a high school education or less. Caregiver relationships were typically spouse/partner or an adult child.

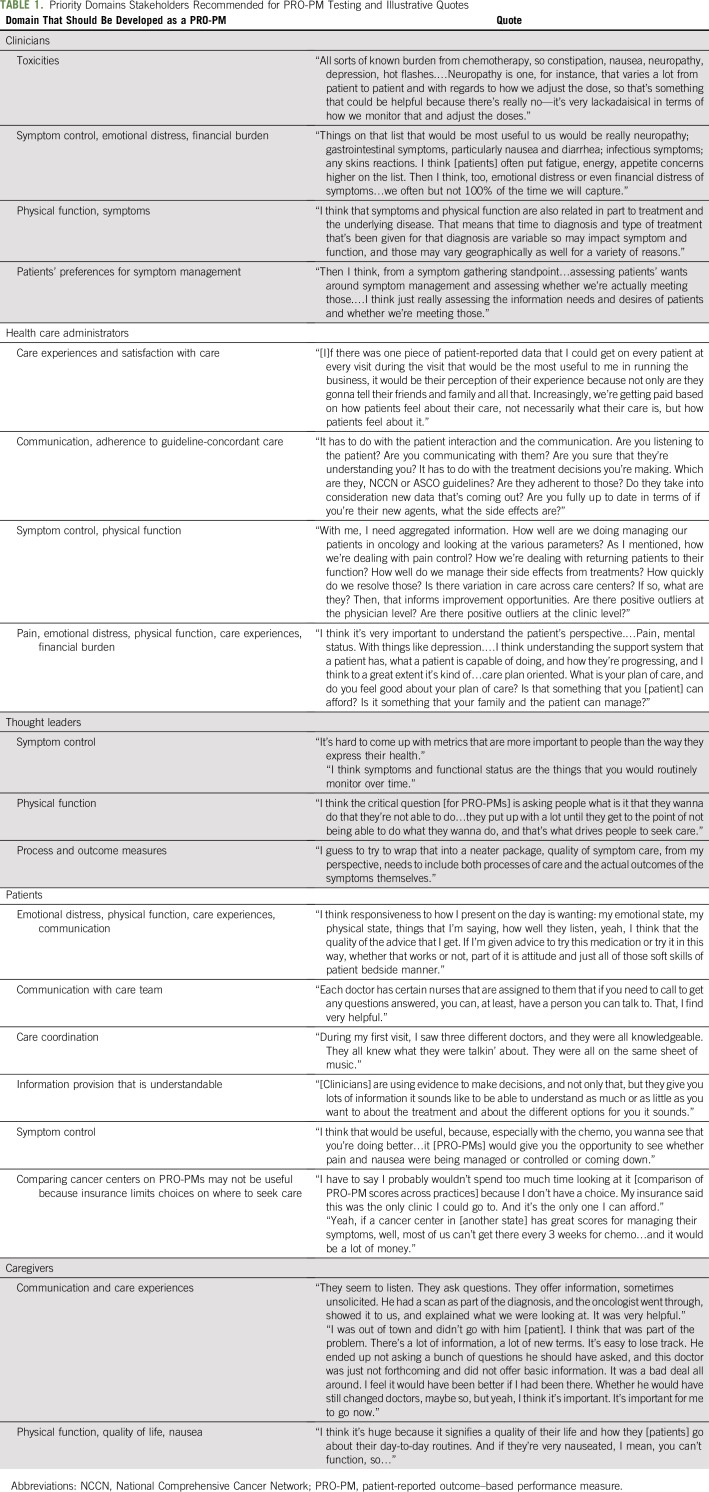

Table 1 lists stakeholders’ recommended key symptoms, including GI symptoms (nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea), fatigue and sleep issues, depression/anxiety, pain, neuropathy, dyspnea, and physical function decrements. Stakeholders recommended the collection of PROMs 5-15 days after the start of a treatment cycle when some symptoms related to therapy, such as nausea, might peak. Twelve potential risk adjustment variables were also identified through interviews and a literature search.2-4,7-9 Five were variables commonly used as risk adjusters: age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance type, and cancer type. Seven additional risk adjustment variables were education, working, married/partnered, difficulty paying bills, palliative versus curative care, regimen and emetic risk, and comorbid conditions.

TABLE 1.

Priority Domains Stakeholders Recommended for PRO-PM Testing and Illustrative Quotes

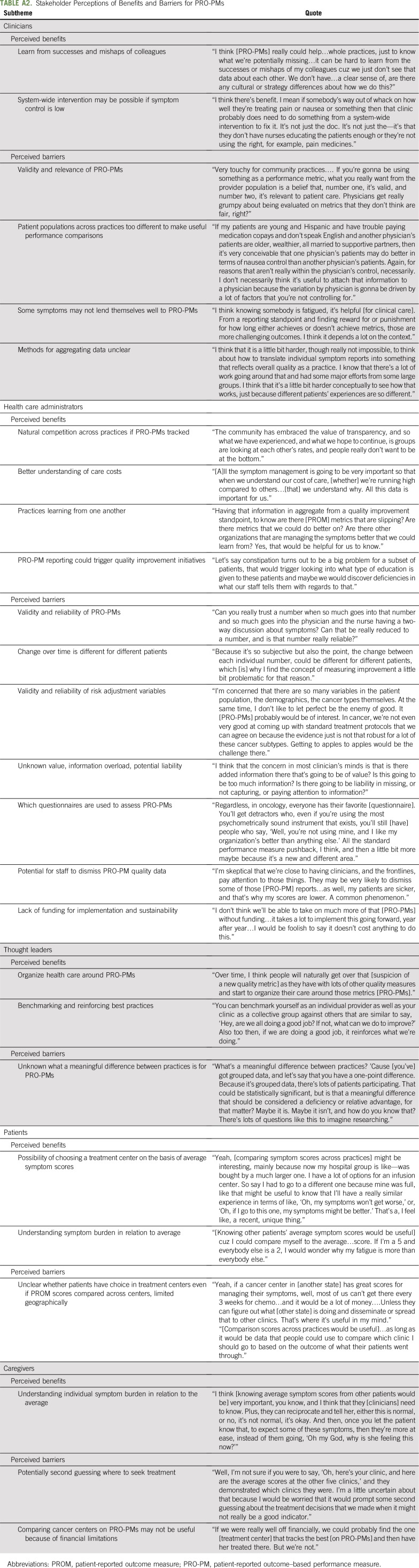

Interview themes indicated that PRO-PMs were perceived to be acceptable by stakeholder groups, with benefits and barriers noted (Appendix Table A2, online only). Clinicians, administrators, and thought leaders suggested a dual-purpose approach, where individual-level PROMs are used at the point of care to improve communication among clinicians and patients during visits and then used as PRO-PMs at the clinic level. Clinicians noted that PRO-PMs could help practices to learn from the successes of colleagues and reveal when system-wide improvements are needed. For barriers, clinician themes were validity and relevance of PRO-PMs.

Administrators perceived that PRO-PMs may encourage natural competition to increase symptom control rates. They also believed that PRO-PMs could enhance their understanding of care costs and help to improve care. Perceived barriers included validity and reliability of PRO-PMs and risk adjustment variables, information overload, liability, potential for staff to dismiss PRO-PM data, and lack of funding for implementation and sustainability. Thought leaders discussed similar topics, with the addition of concerns about what a meaningful difference between practices would be for PRO-PMs.

Patients and caregivers discussed how understanding their symptom burden in relation to other patients would be very helpful to them. Patients and caregivers speculated about the possibility of choosing a treatment center on the basis of average symptom scores at cancer centers but also noted that their choices are limited because of insurance, geographic, and financial constraints.

Feasibility Results

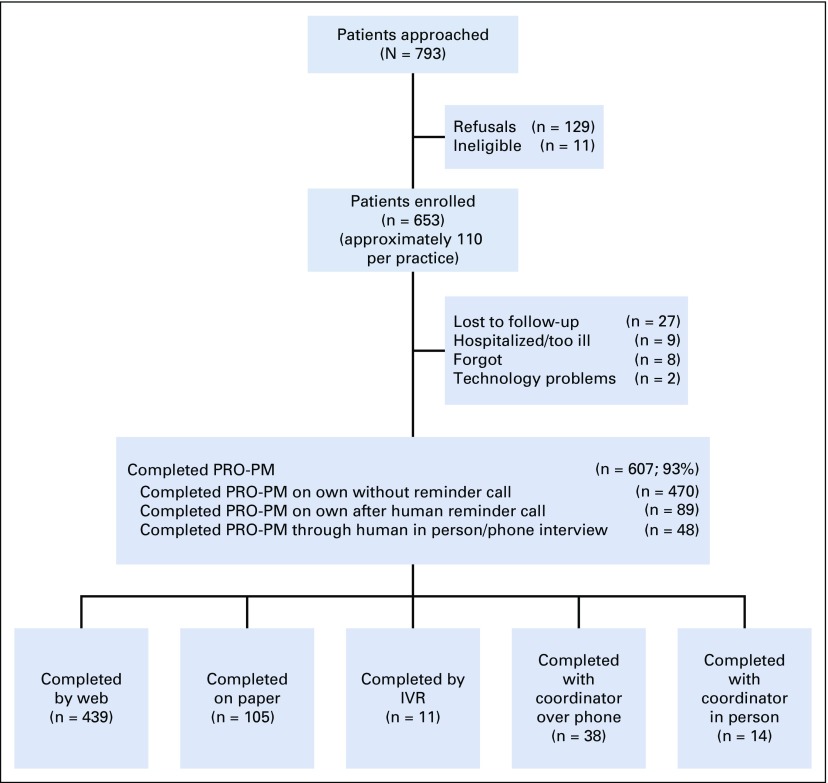

Table 2 lists the demographic characteristics of the feasibility testing patient sample. The sample’s demographic characteristics reflect typical systemic therapy patients. Figure 1 shows that 793 patients were approached, 11 were ineligible, 129 refused, and 653 enrolled. Patients who chose not to participate had similar characteristics to participants on the basis of sex, race/ethnicity, and age (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Demographic Characteristics for Feasibility Testing

Fig 1.

Flow diagram for feasibility testing. IVR, interactive voice response; PRO-PM, patient-reported outcome–based performance measure.

Nearly all enrolled patients (n = 607 of 653; 93%) completed the PRO-PM, which indicates high feasibility for collecting PROMs at home. Figure 1 shows that 470 (77%) of the 607 patients completed the PROM without a reminder call. An additional 137 (23%) completed the questionnaire after a human reminder call (15% web, and 8% completed questions during the reminder call). The majority of participants (439; 72%) completed PROMs through the web; the remainder responded on paper (105; 17%) or through in-person or phone interview (48; 8%) or IVR (11; 2%). Few patients selected Spanish (n = 27; 5%) or Mandarin Chinese (n = 3). Patient acceptability was very high, with 586 (96%) reporting that PROM items were easy/very easy to complete and 590 (97%) reporting that it was easy/very easy to understand.

DISCUSSION

This study adds to the literature by using stakeholder engagement to prioritize domains for PRO-PMs in systemic therapy. The study also shows that PROMs can be feasibly collected at home during a treatment cycle for the development of PRO-PMs.

Stakeholder priority symptoms were pain, mental health, sleep, GI symptoms, numbness, dyspnea, and physical function, which mostly overlap with the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) recommended symptoms to assess in clinical trials40 and a growing literature on recommended symptom sets.41,42 Physical function is not on NCI’s list but was mentioned by stakeholder groups, albeit with some reservations. Stakeholders raised concerns that physical function may not be a fair performance metric because it may be influenced by factors beyond treatment.43,44 Stakeholders also recommended continuing to collect patient experiences of the visit (eg, CAHPS Cancer Care45), which are already common in quality programs.2-5

Clinicians, administrators, and thought leaders believed strongly that PRO-PMs should be part of an overall approach where PROMs are used at the point of care to improve communication among clinicians and patients and then used as aggregated PRO-PMs at the clinic level. Clinicians wanted to be informed of PROMs at visits so that they can intervene, which may increase acceptability of PRO-PMs. Stakeholders noted benefits of PRO-PMs that were mostly consistent with their health care role. Clinicians and administrators described how PRO-PMs could help practices to learn what they are doing well and improvements needed for symptom control. Administrators believed that PRO-PMs may encourage natural competition and could enhance their understanding of care costs. Patients and caregivers believed that understanding symptom burden in relation to other patients would be very helpful. However, patients and caregivers speculated that they may not be able to choose a treatment center on the basis of PRO-PM rates because of insurance, geographic, and financial constraints.

Similar barriers were noted by clinicians, administrators, and thought leaders: validity and relevance of PRO-PMs. Clinicians at all sites mentioned that their patients are more at risk than at other institutions, and thus, training on how risk adjustment variables were empirically chosen and their function may increase transparency. Barriers unique to administrators were liability and lack of funding for implementing PROMs and PRO-PMs. Thought leaders stated that there may be few benchmarks for meaningful differences between practices.

We recommend engaging clinicians, administrators, thought leaders, patients, and caregivers to develop PRO-PMs to increase transparency of the process for professional groups and to include the patient voice. Future research should consider adding payers as a stakeholder group. It is unknown whether recommended PRO-PMs for systemic therapy will generalize to other cancer treatment types (eg, radiation therapy), disease stages, or other health conditions. Additional PRO-PMs may need to be developed for systemic therapy, such as patients’ preferences for symptom management and whether the care team met those expectations.

Compliance rates with PROM questions were high. Patients self-reported on their own 77% of the time, and an additional 23% completed the questions after a human reminder call. Future research is needed to determine whether these percentages generalize to routine care settings and the overall US cancer population. Although stakeholder interviews suggested that both web and IVR be available to patients for reporting PROMs, only a small proportion of patients ultimately used IVR, which suggests that web response with paper and human backup may be sufficient in this context. Potential benefits of IVR are that patients do not need Internet access or computer experience. Broadband access in the United States is highly variable,46 and at-risk groups (eg, older, rural) are less likely to have Internet access.47,48 In a large, pragmatic PROM intervention trial in community oncology practices, more than one third of chemotherapy patients chose IVR to complete their weekly PROM, and these patients represented at-risk groups.28 Dependent on available resources and priorities, cancer centers may want to include an option to contact patients to recover otherwise missing data.

A small number of patients reported not receiving the e-mail prompt to self-report, typically because of the e-mail going to junk folders. There were mixed views about offering a paper option. Some participating sites requested a paper option, and one site opted not to offer paper because of the resources necessary to track and enter patient responses. For sites that offered a paper option, it was difficult to track whether and when PROMs were completed. There were also added expenses of self-addressed stamped envelopes, extra calls to patients, and data entry that may not be feasible for routine care. However, paper or IVR may be necessary to capture PROMs for at-risk groups, especially when considering low response rates for CAHPS questionnaires when used in routine care settings.49

Our next analysis steps are to empirically determine an optimal set of symptoms and physical function domains and risk adjustment variables for PRO-PMs in systemic therapy. Single-item PRO-PMs and composites of items will be evaluated. A second wave of data collection is under way to determine the stability of aggregated scores for cancer centers and to increase sample size. Quantitative analyses of PRO-PMs and risk adjustment variables will be reported elsewhere.

In conclusion, clinicians, patients, and other stakeholders agree that PMs that are based on how patients feel and function would be an important addition to quality measurement. This study also shows that PRO-PMs can be feasibly captured at home during systemic therapy and are acceptable to patients. PRO-PMs may add value to the portfolio of PMs as oncology transitions from fee-for-service payment models to performance-based care that emphasizes outcome measures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This project made use of systems and services provided by the PRO Core at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC). PRO Core is funded in part by an NCI Cancer Center Core Support grant (5-P30-CA016086) and the University Cancer Research Fund of North Carolina. The LCCC Bioinformatics Core provided the computational infrastructure for the project. We acknowledge Lucy Burgess Austin of Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, and Kendall Johnson of Graham, North Carolina, who served as patient investigators for this work.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

PRO-PMs Tested in Feasibility Testing

TABLE A2.

Stakeholder Perceptions of Benefits and Barriers for PRO-PMs

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented at the 24th Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research, Philadelphia, PA, October 18-21, 2017, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2019 Quality Care Symposium, San Diego, CA, September 6-7, 2019.

SUPPORT

Supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award ME-1507-32079 and 1UL1TR00111, KL2TR001109, DK056350, P30-DK56350, P30-CA16086, and P30-CA008748. Research reported in this article was partially funded through PCORI award ME-1507-32079. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors, or its Methodology Committee. This study made use of resources funded through the Gillings School of Global Public Health, Nutrition Obesity Research Center (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant P30-DK56350), and the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (National Cancer Institute grant P30-CA16086): the Communication for Health Applications and Interventions Core.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Angela M. Stover, Benjamin Y. Urick, Allison M. Deal, Randall Teal, Jennifer Jansen, Anne Chiang, Charles Cleeland, Yehuda Deutsch, Edmund Tai, Dylan Zylla, Collette Pitzen, Claire Snyder, Bryce Reeve, Michael N. Neuss, Thomas M. Atkinson, Mary Lou Smith, Cindy Geoghegan, Ethan M. Basch

Financial support: Ethan M. Basch

Administrative support: Collette Pitzen, Ethan M. Basch

Provision of study material or patients: Anne Chiang, Dylan Zylla, Loretta A. Williams, Ethan M. Basch

Collection and assembly of data: Angela M. Stover, Allison M. Deal, Randall Teal, Maihan B. Vu, Jessica Carda-Auten, Jennifer Jansen, Anne Chiang, Charles Cleeland, Yehuda Deutsch, Edmund Tai, Dylan Zylla, Loretta A. Williams, Ethan M. Basch

Data analysis and interpretation: Angela M. Stover, Benjamin Y. Urick, Allison M. Deal, Randall Teal, Maihan B. Vu, Jessica Carda-Auten, Jennifer Jansen, Arlene E. Chung, Antonia V. Bennett, Charles Cleeland, Anne Chiang, Edmund Tai, Dylan Zylla, Collette Pitzen, Claire Snyder, Tenbroeck Smith, Kristen McNiff, David Cella, Robert Miller, Michael N. Neuss, Thomas M. Atkinson, Patricia A. Spears, Mary Lou Smith, Ethan M. Basch

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Performance Measures Based on How Adults With Cancer Feel and Function: Stakeholder Recommendations and Feasibility Testing in Six Cancer Centers

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Angela M. Stover

Honoraria: Genentech

Benjamin Y. Urick

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pharmacy Quality Solutions

Research Funding: Cardinal Health

Arlene E. Chung

Honoraria: United Health Group R&D

Anne Chiang

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Roche, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Research Funding: OncoMed, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Onyx, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Stem CentRx, AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech, Roche, AstraZeneca, AbbVie

Dylan Zylla

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Exact Sciences (Inst), Roche (Inst), Amgen (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Innate (Inst)

Loretta A. Williams

Consulting or Advisory Role: PledPharma

Research Funding: Bayer AG (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Merck (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Colette Pitzen

Employment: MN Community Measurement

Honoraria: American Journal of Managed Care (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: American Journal Managed Care

Claire Snyder

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties as a section author for UptoDate

Kristen McNiff

Employment: UnitedHealthcare

David Cella

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: FACIT.org

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Novartis, PledPharma, Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Corcept Therapeutics, IDDI, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Asahi Kasei Pharma Corp, Ipsen

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Bayer AG (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), PledPharma (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Ipsen, PledPharma

Patricia A. Spears

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer

Mary Lou Smith

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Genomic Health (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Foundation Medicine (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech, Roche

Cindy Geoghegan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene

Ethan M. Basch

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sivan, Carevive Systems, Navigating Cancer

Other Relationship: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Cancer Institute, ASCO, Journal of the American Medical Association, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/427875/summary

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Health Care Progress. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Quality Forum: White Paper, The Current State of Cancer Quality Measurement, 2008. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2008/09/White_Paper,_The_Current_State_of_Cancer_Quality_Measurement.aspx.

- 3.Desch CE, McNiff KK, Schneider EC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/National Comprehensive Cancer Network Quality Measures. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3631–3637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert E, Sherry V, McGettigan S, et al. Health-Care metrics in oncology. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2015;6:57–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuss MN, Malin JL, Chan S, et al. Measuring the improving quality of outpatient care in medical oncology practices in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1471–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. US Food and Drug Administration: Patient-Focused Drug Development: Methods to Identify What Is Important to Patients: Draft Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders. Washington, DC, US Food and Drug Administration, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cella D, Hahn E, Jensen SE, et al: Patient-Reported Outcomes in Performance Measurement. Research Triangle Park, NC, RTI International Press 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basch E, Snyder C, McNiff K, et al. Patient-reported outcome performance measures in oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:209–211. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Troeschel A, Smith T, Castro K, et al. The development and acceptability of symptom management quality improvement reports based on patient-reported data: An overview of methods used in PROSSES. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2833–2843. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin PD. Research priorities for optimal use of patient-reported outcomes in quality and outcome improvement for total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:S51–S54. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung M, Bounsanga J, Voss MW, et al. Establishing minimum clinically important difference values for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System physical function, hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint reconstruction, and knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score for joint reconstruction in orthopaedics. World J Orthop. 2018;9:41–49. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i3.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Blueprint for the CMS Measurement System (version 12.0), 2016. https://www.cms.gov/

- 13. National Quality Forum: Measuring What Matters to Patients: Innovations in Integrating the Patient Experience into Development of Meaningful Performance Measures, 2017. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/08/Measuring_What_Matters_to_Patients__Innovations_in_Integrating_the_Patient_Experience_into_Development_of_Meaningful_Performance_Measures.aspx.

- 14. National Committee for Quality Assurance: Improving the Health Care Experience: Measuring What Matters to People Measuring Quality for Adults with Complex Needs, 2018. http://ncqa.gov.

- 15.Reilly CM, Bruner DW, Mitchell SA, et al. A literature synthesis of symptom prevalence and severity in persons receiving active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1525–1550. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1688-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrstedt J, Roila F, Warr D, et al. 2016 updated MASCC/ESMO consensus recommendations: Prevention of nausea and vomiting following high emetic risk chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:277–288. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Society of Clinical Oncology: ASCO clinical practice guidelines. https://ascopubs.org/jco/site/misc/specialarticles.xhtml.

- 19.Pitzen C, Larson J. Patient-reported outcome measures and integration into electronic health records. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:867–872. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.014118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. MN Community Measurement: Health Care Quality Report. https://mncm.org/reports-and-websites/reports-and-data/health-care-quality-report.

- 21. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: MACRA funding opportunity: Measure development awardees for quality payment program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/9-21-18-QPP-Measures-Cooperative-Agreement-Awardees.pdf.

- 22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation: Oncology Care First Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/ocf-informalrfi.pdf.

- 23. Patton MQ: Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. London, UK, Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3816–3824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hahn EA, Cella D. Health outcomes assessment in vulnerable populations: Measurement challenges and recommendations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:S35–S42. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris AM, Rhoads KF, Stain SC, et al. Understanding racial disparities in cancer treatment and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stover AM, Irwin D, Chen RC, et al: Integrating patient-reported outcome measures into routine cancer care: Cancer patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of acceptability and value. EGEMs (Wash DC) 3:1169, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Stover AM, Tompkins Stricker C, Hammelef K, et al. Using stakeholder engagement to overcome barriers to implementing patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in cancer care delivery: Approaches from three prospective studies. “PRO-Cision” Medicine Toolkit. Med Care. 2019;57:S92–S99. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess LM, Pohl G. Perspectives of quality care in cancer treatment: A review of the literature. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6:321–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colosia AD, Peltz G, Pohl G, et al. A review and characterization of the various perceptions of quality cancer care. Cancer. 2011;117:884–896. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel MI, Periyakoil VS, Blayney DW, et al. Redesigning cancer care delivery: Views from patients and caregivers. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e291–e302. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basch E, Spertus J, Dudley RA, et al. Methods for developing patient-reported outcome-based performance measures (PRO-PMs) Value Health. 2015;18:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. ed 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, et al: Development of the National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju244, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA, et al. Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1051–1059. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): Depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ottery FD. Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition. 1996;12:S15–S19. doi: 10.1016/0899-9007(96)90011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristensen A, Solheim TS, Amundsen T, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life during chemotherapy - the importance of timing. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:737–745. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1279748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Dueck AC, et al: Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in adult cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju129, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Chera BS, Eisbruch A, Murphy BA, et al. Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in head and neck cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju127. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen RC, Chang P, Vetter RJ, et al. Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in prostate cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ness KK, Wall MM, Oakes JM, et al. Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: A population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salakari MRJ, Surakka T, Nurminen R, et al. Effects of rehabilitation among patients with advances cancer: A systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:618–628. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.996661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Evensen C, Yost KJ, Keller S, et al: CAHPS Cancer Care Survey: Development, testing, and final content of a survey of patient experience with cancer care. J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 (suppl; abstr 227) [Google Scholar]

- 46. Federal Communications Commission: 2018 Broadband Deployment Report. https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/broadband-progress-reports/2018-broadband-deployment-report.

- 47.Perzynski AT, Roach MJ, Shick S, et al. Patient portals and broadband internet inequality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24:927–932. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, et al. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129:611–620. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fowler FJ, Jr, Cosenza C, Cripps LA, et al. The effect of administration mode on CAHPS survey response rates and results: A comparison of mail and web-based approaches. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:714–721. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]