Abstract

Objective The aim of this study was to investigate the healing effect of advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF) clot membranes in palatal wounds, resulting from free gingival graft (FGG) harvesting, on the reepithelization rate and on the pain experience after surgery.

Materials and Methods Twenty-five patients requiring FGG have participated in this prospective cohort study. After FGG harvesting, the test group ( n = 14) received A-PRF clot membranes at the palatal wound and the control group ( n = 11) received a gelatin sponge. Epithelialization rate of the palatal wound, wound healing area, correspondent percentage of reduction, and postsurgical pain experience were assessed at 2, 7, 14, 30, and 90 days.

Results A-PRF group had higher palatal wound reduction than the control group, at 7, 14, and 30 days of follow-up. The highest difference between the groups was attained at 30 days (91.5% for A-PRF vs. 59.0% control group). At 14 days, a significant difference in the proportion of patients showing total epithelization was found: 64.3% for A-PRF versus 9.1% for the control group. At 90 days, both groups showed total recovery. The control group experienced higher pain level and discomfort until the 14th day, being notably higher on the second day.

Conclusion The results suggest that A-PRF membranes haste the healing process, and promote greater reduction along the recovery period and less painful postoperative period.

Keywords: advanced platelet-rich fibrin, biomaterials, free gingival graft, pain, wound healing

Introduction

The hard palate is a common source of soft-tissue grafts (STG) for periodontal and peri-implant plastic surgery procedures. 1 2 Despite the advantages against more conservative methods, 3 free STG involves a secondary intervention and demands an appropriate donor site, which, after the harvest, cures through secondary intention, and is more uncomfortable and painful, requiring a more extended healing period. 4

Leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) has a similar appearance to an autologous cicatricial matrix. 5 6 L-PRF is a very dense fibrinogenic biomaterial with winning biomechanical and biological properties 7 and broad application in several areas of medicine. 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 In this way, it serves as a biological healing matrix and acts as an immune regulation node with inflammation control abilities, supporting the cell migration and cytokines. 5 Recently, advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF) emerged with the decrease of rotations per minute (rpm) and increase of centrifugation time, which results in the enhanced presence of neutrophilic granulocytes in the distal part of the clot. 16 Also, A-PRF is not merely a scaffold per se but a growth factors reservoir with a continuous release action. 17 18 19

Thereupon, two randomized clinical trials (RCT) have investigated the therapeutic potential of L-PRF on palatal wounds after FGG harvesting. 20 21 Whereas in 20 quadruple PRF membrane layers were placed over the wound and held with multiple sutures, in 21 the wound was spatially filled with the required and undefined amount of L-PRF and stabilized with cyanoacrylate adhesive on all borders and surfaces. Both trials have concluded that L-PRF stimulates palatal wound healing and improves patients’ postoperative morbidity. Recently, two intervention studies tested A-PRF on ridge preservation 22 and endodontic surgery; 23 however, influence of A-PRF on the wound area reduction and reepithelization is still lacking.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the healing effect of A-PRF clot membranes in reducing palatal wounds after FGG harvesting and to compare the postsurgical pain experience and complications with a conventional procedure where a gelatin sponge was placed in the palatal wound.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a prospective cohort study with control, assessor-blinded, and flipping coin randomization.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were patients at least 18 years old, without systemic and periodontal diseases, no medical contraindications for periodontal surgery, and adequate level of plaque control (plaque index < 15%).

Exclusion criteria were patients with: smoking habits, diabetes mellitus, removable upper denture, regular medication that could interpose the healing process, undergoing bisphosphonate therapy, history of radiation therapy of the jaws, and dropped follow-up consults.

Patients who met these criteria were invited to participate in the study after being thoroughly informed about the purpose of the clinical research. All patients that agreed to participate in the study were invited to sign the informed consent form. The study was approved by an Ethics Committee of Egas Moniz (Approval 601) and a written consent was obtained from all participants. This study was conducted following the obligations of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and revised in 2013.

Participants and Randomization

The study took place between March and June 2018, involving patients referred to the Periodontology Department of Egas Moniz Dental Clinic (Almada, Portugal).

At the beginning of the study, and according to the sample size calculation, 30 patients in need of soft tissue augmentation (gingival recession coverage or augmentation of keratinized gingiva), who met the inclusion criteria, were enrolled to participate. They were, a priori , randomly 1:1 allocated to control ( n = 15) or A-PRF ( n = 15) groups, via coin toss, and performed by an assistant not involved in the study. Five of the patients refused to participate, resulting in a final sample of 25 individuals ( n = 11 control, n = 14 A-PRF). During the 90 days’ follow-up period, there were no subjects withdrawing the study.

Interventions

Prior to surgery, to ensure levels of plaque index below 15%, all participants received oral hygiene instructions and scaling, root planing and polishing. Alginate impressions were made for a palate protective splint production to be used within 2 days after the surgery.

All interventions were performed under strict sterile conditions and local anesthesia (articaine 72 mg + epinephrine 0.009 mg/1.8 mL). A FGG with approximately 1.5 mm thickness was removed from the palatal area from first premolar to first molar, as described in. 24 All surgeries were supervised by the same periodontist (RA). The treatment at the test site was performed as follows:

Preparation of A-PRF: It was performed as a standard venipuncture (median basilica vein, median cubital vein, and median cephalic vein). Ten mL of blood was drawn into a tube without anticoagulant (VACUETTE; PRF Process, Nice, France). A-PRF was prepared following. 18 The tubes were immediately centrifuged according to the manufacturer instructions at 1,500 rpm for 8 minutes (DUO Quattro; A-PRF Process, Nice, France). After centrifugation, A-PRF clot was removed from the tube and separated from the red element phase at the base with pliers. Then, A-PRF was delicately squeezed between a sterile metal plate and a metal box (gravity, no loading).

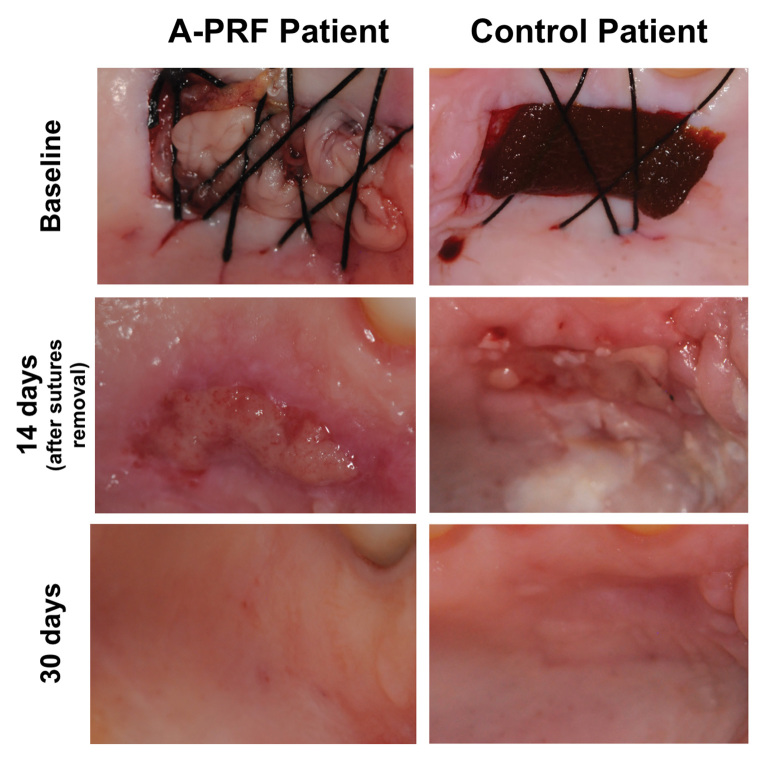

Palatal wound, as a result of FGG harvesting, was occupied by two A-PRF clot membranes after careful positioning, and crisscross sutures were done to hold it in position ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Surgical technique for application of A-PRF, and evaluation of postoperative epithelialization in the PRF and test groups at baseline, 14 days and 30 days after surgery. A-PRF, advanced platelet-rich fibrin.

For the control group, the surgical wound as a result of the graft collecting was filled with lyophilized hydrolyzed collagen sponge (Technew, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) ( Fig. 1 ).

All patients were advised to take paracetamol (1 g) three times a day, use the protective splint for 2 days, avoid heat sources, and opt for cold and soft foods diet. To prevent results’ bias, mouth disinfectants were disregarded due to difficulty in monitoring. Patients were scheduled for control visits at 2, 7, 14, 30, and 90 days.

Two days after surgery, all patients returned the protective splint to prevent continued usage. Palatal sutures were removed at 7 days after surgery, and receiving zone sutures at 14 days. The control protocol consisted of the assessment of the palatal wound healing area and evaluation of postoperative pain and discomfort sensation.

Primary Outcomes: Epithelialization of the Palatal Wound, Wound Healing Area and Percentage of Reduction

Follow-up control protocol included palatal wound measuring, using a CP-12 probe, and photography of the wound healing area (in mm 2 ). For the epithelialization clinical appraisal, one calibrated examiner (F.P.) used the wound closure visual criteria of (as a percentage). 2 After FGG and using a CP-12 probe, palatal depth was recorded as the average of all four margins (in mm), with each margin contributing with the deepest value measured.

Secondary Outcomes: Postoperative Pain and Discomfort Sensation

Patient’s pain and discomfort perceptions were rated using the visual analogue scale (VAS) score (0–10) and registered during the follow-up period.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

The sample size was calculated to provide a power 1-β = 90%, with α = 5%, to detect the difference in the proportion of patients who exhibited epithelialization after 3 weeks among patients whose palatal wounds were treated with L-PRF (test group) and with an absorbable gelatin sponge (control group), as reported in. 20 Therefore, a minimum of seven patients per group (14 in total) were necessary. To prevent the loss of statistical power, due to patient drop-out, a total of 30 patients, who met the inclusion criteria, were enrolled to participate.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 for Windows (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for the clinical scale and ordinal variables, respectively. Population means were estimated by calculating 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). In the inferential analysis, since the assumptions for valid parametric inference were not met, Mann—Whitney test was used to compare the primary clinical outcome (percentage decrease of palatal wound area) and the postoperative pain and discomfort sensation (VAS) between groups. Correlation between percentage decrease of wound area and postoperative pain and discomfort sensation, with depth of the palate, was assessed by Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare total epithelization proportion between groups. The level of statistical significance was set at 5% in all inferential analyses.

Results

Demographic Data

Twenty-five patients participated in this prospective cohort study. The mean age was 36.4 ± 14.9 years (range 19–65 years) and the female/male ratio was 16/9.

Palatal Surgical Wound Area Decrease, Percentage of Reduction and Epithelialization

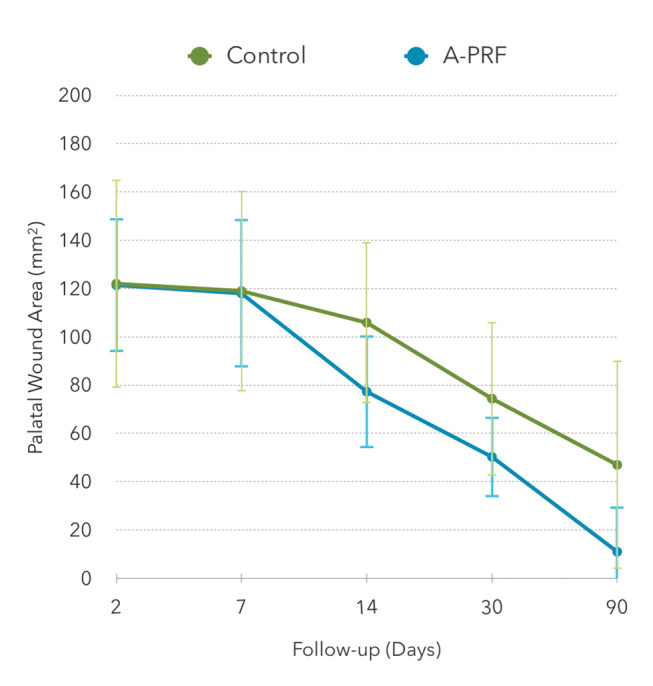

Results for the palatal wound area, as a function of the follow-up period, are displayed in Table 1 and represented in Fig. 2 . On the second day, sutures were intact, and in the test group, all A-PRF membranes where adherent to the palate.

Table 1. Palatal wound area (mm 2 ) presented as mean (standard deviation–SD) and estimated mean (95% CI), evaluated at surgery and along with the follow-up visits, for the control ( n = 11) and A-PRF ( n = 14) groups .

| Follow-up (d) | Palatal wound area (mm 2 ) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | A-PRF group | |||

| Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | |

| 0 (surgery) | 122.0 (43.1) | 93.0–151.0 | 121.4 (27.8) | 105.4–137.5 |

| 2 | 119.0 (41.6) | 91.0–146.9 | 118.0 (30.8) | 100.2–135–8 |

| 7 | 105.1 (33.4) | 82.7–127.5 | 77.3 (23.3) | 63.8–90.7 |

| 14 | 74.5 (31.9) | 53.0–95.9 | 50.3 (16.6) | 40.7–59.9 |

| 30 | 47.0 (17.2) | 35.4–58.6 | 11.0 (18.8) | 0.16–21.8 |

| 90 | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | – |

Fig. 2.

Palatal wound area (mm 2 ), evaluated along the follow-up visits, for the control ( n = 11) and A-PRF ( n = 14) groups.

Table 2 presents the mean percentage reduction area of the palatal wound during the follow-up visits. A-PRF group showed a significant larger decrease percentage than the control group at 7, 14, and 30 days, conversely to the first two days after surgery, where no statistically significant difference was found. The maximum difference between the groups was attained at 30 days (91.5% for A-PRF versus 59.0% for the control group). At 90 days, both groups showed total recovery.

Table 2. Percentage decrease of the palatal wound area, presented as mean (standard deviation - SD), along with the follow-up visits, for the control ( n = 11) and A-PRF ( n = 14) groups .

| Follow-up (days) | Palatal wound reduction area (%) | p -Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group mean (SD) | A-PRF group mean (SD) | ||

| a Mann–Whitney U test. | |||

| 2 | 2.0 (5.1) | 2.9 (10.7) | 0.687 |

| 7 | 12.9 (12.2) | 36.4 (12.2) | < 0.001 |

| 14 | 36.6 (20.4) | 58.0 (14.2) | 0.009 |

| 30 | 59.0 (14.3) | 91.5 (14.6) | < 0.001 |

| 90 | 100.0 (0.0) | 100 (0.0) | – |

The baseline palatal depth ranged from 3 to 5 mm (control group) and 2 to 6 mm (A-PRF group), with an average of 3.8 (0.6) and 3.6 (1.1) mm, respectively. Moreover, when assessing the healing rate, via the percentage reduction of wound area, as a function of the depth of the palate, a significant negative correlation occurred for the A-PRF group at 30 days’ follow-up (Spearman’s correlation coefficient= − 0.61, p = 0.021), indicating that in palates with greater baseline thickness, A-PRF accelerated the recovery. In addition, correlation of palatal depth with the postoperative pain sensation was not found to be significant in either of the groups.

Table 3 displays the epithelization rate for both groups along with the follow-up period ( Fig. 1 ). At 14 days, A-PRF group showed significant higher total epithelization than the control group ( p = 0.012). At 30 days, total epithelization was observed in more than 90% of all patients without difference between the groups ( p = 1.000).

Table 3. Total epithelization, presented as n (%), along with the follow-up visits, for the control ( n = 11) and A-PRF ( n = 14) groups .

| Follow-up (days) | Total epithelization, n (%) | p -Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | A-PRF group | ||

| a Fisher’s exact test. | |||

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| 7 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| 14 | 1 (9.1) | 9 (64.3) | 0.012 |

| 30 | 10 (90.9) | 13 (92.9) | 1.000 |

| 90 | 11 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | – |

Postoperative Complications

Postoperative complications were identified on the second day (hemorrhage: one patient in the control group and two patients in the A-PRF group); on the seventh day, in the control group, one patient exhibited necrosis of donor site margins.

Postoperative Pain Experience

Overall, the control group experienced a higher level of pain and discomfort until the 14th day, being significantly higher at the second day. Subjects in the A-PRF group felt pain only until the second day after surgery. At 30 and 90 days, no pain was detected in either of the groups ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Postoperative pain experience, recorded through a VAS and presented as median (interquartile range–IQR), along with the follow-up visits, for the control ( n = 11) and A-PRF ( n = 14) groups .

| Follow-up (days) | Postoperative pain experience (VAS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | A-PRF group | ||||

| Median (IQR) | Min.-Max. | Median (IQR) | Min.-Max. | p -Value a | |

| Abbreviation: VAS, visual analogue scale; IQR, interquartile range. a Mann–Whitney U test. | |||||

| 2 | 2.0 (2) | 0–9 | 0.0 (1) | 0–7 | 0.013 |

| 7 | 1.0 (2) | 0–9 | 0.0 (0) | 0–0 | – |

| 14 | 0.0 (0) | 0–5 | 0.0 (0) | 0–0 | – |

| 30 | 0.0 (0) | 0–0 | 0.0 (0) | 0–0 | – |

| 90 | 0.0 (0) | 0–0 | 0.0 (0) | 0–0 | – |

Discussion

In this study, we tested A-PRF as palatal wound healing co-adjuvant after FGG. Overall, A-PRF benefits palatal tissue recovery up to 30 days postsurgery, and from there up to 90 days this difference vanishes. Thus, A-PRF as a palatal dressing seems to enhance patient's surgery experience by improving healing of the donor site. These outcomes comply with previous studies that investigated other PRF types for the same purpose. 20 21 25 26

Nevertheless, although from the short-term view, A-PRF significantly promotes the reepithelialization of the wound (on day 14), from a long-term perspective, it was not shown to be significant, as observed at 30 days after surgery. In fact, being the first time A-PRF is used in this palatal bandage procedure, there are no forms of comparison other than other types of PRF. Plausibly, this difference may be due to the smaller thickness/quantity of the PRF membranes used in our study, since similar results have been found using single membranes of PRF and T-PRF, 25 26 and are different described in Femminella et al, 20 which used quadruple layer clots. Thus, thicker PRF have apparent lower degradation and faster re-epithelialization process.

Considering the patient’s pain experience perspective, A-PRF group participants apparently had a minimal but significant less sense of pain. However, there is insufficient data to associate this less experience with the placement of A-PRF membranes, since we cannot dissociate the possible effect of the wound extent and surgery time. Furthermore, it is difficult to isolate the pain originating from donor and recipient site, particularly if they are on the same quadrant. Therefore, this matter must be broadly and deeply investigated.

Noteworthy, deeper palates showed better healing results using A-PRF, which can be explained by the wealth of growth factors within. Yet, according to Wyrębek et al, 27 pain had no association with the FGG length and width, although they did not consider the initial thickness of the palate. In our investigation, the thickness of the graft was not measured, which may explain the powerlessness with postsurgery pain.

Since its introduction, A-PRF has been extensively studied in its composition, biocompatibility, and performance in vitro. 16 17 18 28 Regarding the limitations of this study, A-PRF maintains some major PRF technique disadvantages. PRFs require blood collection and careful handling, there is vague knowledge on the leukocytes, platelets, and growth factors concentration on the clots, and the established protocols are highly variable. In addition, while these results are encouraging, we cannot forget the fact that this study design lacks RCT methodology, such as random sequence generation and allocation concealment, since the remaining aspects were covered. Also, patient-centered outcome measures, like oral health-related quality of life, and thorough medication dosage should be pondered in future investigations, since these surgical adjunct healing procedures aim at improving patient experience in periodontal surgeries.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, this study’s results suggest that A-PRF membranes accelerate the healing process by promoting a higher reduction along the recovery period and an apparent less painful postoperative period.

Acknowledgment

The materials were kindly provided on a temporary basis by PRF Process, France.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement/Confirmation of Patients’ PermissionClinical RelevanceAuthors’ ContributionsConflict of Interest This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Egas Moniz. All participants provided their signed informed consent.

The use of A-PRF dressings may be a simple and effective method of accelerating the healing process and reducing postoperative discomfort associated with FGG harvesting.

All investigators independently performed all phases of the study, including protocol development, experimental procedures, data analysis, result interpretation, and reporting.

None declared.

References

- 1.Dragan I F, Hotlzman L P, Karimbux N Y, Morin R A, Bassir S H. Clinical outcomes of comparing soft tissue alternatives to free gingival graft: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2017;17(04):370–380000. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva C O, Ribeiro E delP, Sallum A W, Tatakis D N. Free gingival grafts: graft shrinkage and donor-site healing in smokers and non-smokers. J Periodontol. 2010;81(05):692–701. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennani V, Ibrahim H, Al-Harthi L, Lyons K M. The periodontal restorative interface: esthetic considerations. Periodontol 2000. 2017;74(01):74–101. doi: 10.1111/prd.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahammam MA. Effect of platelet-rich fibrin palatal bandage on pain scores and wound healing after free gingival graft: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(09):3179–3188. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2397-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohan D M, Choukroun J, Diss A et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part III: leucocyte activation: a new feature for platelet concentrates? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(03):e51–e55. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caruana A, Savina D, Macedo J P, Soares S C. From platelet-rich plasma to advanced platelet-rich fibrin: biological achievements and clinical advances in modern surgery. Eur J Dent. 2019;13(02):280–286. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1696585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohan Ehrenfest D M, Del Corso M, Diss A, Mouhyi J, Charrier J-B. Three-dimensional architecture and cell composition of a Choukroun’s platelet-rich fibrin clot and membrane. J Periodontol. 2010;81(04):546–555. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theys T, Van Hoylandt A, Broeckx C E et al. Plasma-rich fibrin in neurosurgery: a feasibility study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2018;160(08):1497–1503. doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castro A B, Meschi N, Temmerman A et al. Regenerative potential of leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin. Part A: intra-bony defects, furcation defects and periodontal plastic surgery. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(01):67–82. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro A B, Meschi N, Temmerman A et al. Regenerative potential of leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin. Part B: sinus floor elevation, alveolar ridge preservation and implant therapy. A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(02):225–234. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredes F, Pinto J, Pinto N et al. Potential effect of leukocyte-platelet-rich fibrin in bone healing of skull base: a pilot study. Int J Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1.23187E6. doi: 10.1155/2017/1231870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding H, Yuan J Q, Zhou J H et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of application of fibrin sealant after liver resection. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(04):387–394. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.768216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal S K, Jhingran R, Bains V K, Srivastava R, Madan R, Rizvi I. Patient-centered evaluation of microsurgical management of gingival recession using coronally advanced flap with platelet-rich fibrin or amnion membrane: A comparative analysis. Eur J Dent. 2016;10(01):121–133. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.175686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma A, Aggarwal N, Rastogi S, Choudhury R, Tripathi S. Effectiveness of platelet-rich fibrin in the management of pain and delayed wound healing associated with established alveolar osteitis (dry socket). Eur J Dent. 2017;11(04):508–513. doi: 10.4103/ejd.ejd_346_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abirami T, Subramanian S, Prakash P SG, Victor D J, Devapriya A M. Comparison of connective tissue graft and platelet rich fibrin as matrices in a novel papillary augmentation access: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Dent. 2019;13(04):607–612. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3399453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghanaati S, Booms P, Orlowska A et al. Advanced platelet-rich fibrin: a new concept for cell-based tissue engineering by means of inflammatory cells. J Oral Implantol. 2014;40(06):679–689. doi: 10.1563/aaid-joi-D-14-00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuki H, Okudera T, Watanebe T et al. Growth factor and pro-inflammatory cytokine contents in platelet-rich plasma (PRP), plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF), advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF), and concentrated growth factors (CGF). Int J Implant Dent. 2016;2(01):19. doi: 10.1186/s40729-016-0052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Miron R J, Hernandez M, Kandalam U, Zhang Y, Choukroun J. Optimized platelet-rich fibrin with the low-speed concept: growth factor release, biocompatibility, and cellular response. J Periodontol. 2017;88(01):112–121. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miron R J, Chai J, Zheng S, Feng M, Sculean A, Zhang Y. A novel method for evaluating and quantifying cell types in platelet rich fibrin and an introduction to horizontal centrifugation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2019;107(10):2257–2271. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Femminella B, Iaconi M C, Di Tullio M et al. Clinical comparison of platelet-rich fibrin and a gelatin sponge in the management of palatal wounds after epithelialized free gingival graft harvest: a randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2016;87(02):103–113. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozcan M, Ucak O, Alkaya B, Keceli S, Seydaoglu G, Haytac M C. Effects of platelet-rich fibrin on palatal wound healing after free gingival graft harvesting: a comparative randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2017;37(05):e270–e278. doi: 10.11607/prd.3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark D, Rajendran Y, Paydar S et al. Advanced platelet-rich fibrin and freeze-dried bone allograft for ridge preservation: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2018;89(04):379–387. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soto-Peñaloza D, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Cervera-Ballester J, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Tarazona-Alvarez B, Peñarrocha-Oltra D. Pain and quality of life after endodontic surgery with or without advanced platelet-rich fibrin membrane application: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00784-019-03033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuhr O, Bäumer D, Hürzeler M. The addition of soft tissue replacement grafts in plastic periodontal and implant surgery: critical elements in design and execution. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41 15:S123–S142. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulkarni M R, Thomas B S, Varghese J M, Bhat G S. Platelet-rich fibrin as an adjunct to palatal wound healing after harvesting a free gingival graft: a case series. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18(03):399–402. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.134591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ustaoğlu G, Ercan E, Tunali M. The role of titanium-prepared platelet-rich fibrin in palatal mucosal wound healing and histoconduction. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74(07):558–564. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2016.1219045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyrębek B, Górski B, Górska R. Patient morbidity at the palatal donor site depending on gingival graft dimension. Dent Med Probl. 2018;55(02):153–159. doi: 10.17219/dmp/91406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe T, Isobe K, Suzuki T et al. An evaluation of the accuracy of the subtraction method used for determining platelet counts in advanced platelet-rich fibrin and concentrated growth factor preparations. Dent J (Basel) 2017;5(01):7. doi: 10.3390/dj5010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]