Abstract

Helicobacter pylori, the most common etiologic agent of gastric diseases including gastric cancer, is auxotrophic for cholesterol and has to hijack it from gastric epithelia. Upon uptake, the bacteria convert cholesterol to cholesteryl 6′-O-acyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (CAG) to promote lipid raft clustering in the host cell membranes. However, how CAG appears in the host to exert the pathogenesis still remains ambiguous. Herein we identified hp0499 to be the gene of cholesteryl α-D-glucopyranoside acyltransferase (CGAT). Together with cholesteryl glucosyltransferase (catalyzing the prior step), CGAT is secreted via outer membrane vesicles to the host cells for direct synthesis of CAG. This significantly enhances lipid rafts clustering, gathers adhesion molecules (including Lewis antigens and integrins α5, β1), and promotes more bacterial adhesion. Furthermore, the clinically used drug amiodarone was shown as a potent inhibitor of CGAT to effectively reduce the bacterial adhesion, indicating that CGAT is a potential target of therapeutic intervention.

Subject terms: Cellular microbiology, Integrins, Pathogens

Jan et al. identify cholesteryl α-D- glucopyranoside acyltransferase as a key enzyme in Helicobacter pylori’s synthesis of cholesteryl 6’-O-acyl-α-D-glucopyranoside, which promotes bacterial adhesion. This study provides insights into the H. pylori-induced pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies against it.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infects more than half of the world’s population1. The bacterial infection not only results in various gastrointestinal diseases that include gastric carcinoma and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, but also represents a leading cause of cancer-related deaths2. The pathogenicity of H. pylori is closely associated with the genes of cag-pathogenicity island, the 40-kb-long sequence of 31 coding regions including the type IV secretion system (T4SS)3,4. Following the attachment of H. pylori to gastric epithelial cells, the T4SS apparatus injects the cag-pathogenicity island-encoded protein CagA into the attached host cells. Once delivered inside the cells, CagA undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation by c-Src family kinases. The phosphorylated CagA then activates several cellular signaling processes, including those leading to cancer development5.

The attachment of H. pylori to gastric epithelia is a necessary process for colonization, as well as an initial step in the pathogenesis6. The increasing level of H. pylori adhesion was found relevant to several deteriorating developments, such as epithelial cell degeneration and mucin depletion. Among several important factors contributing to the bacterial adhesion, BabA is the best characterized adhesin that recognizes Lewisb/ABO blood group antigens7,8. Another adhesin SabA binds specifically to sialyl Lewisx and sialyl Lewisa antigens9. The T4SS pili of H. pylori, probably assembled upon an initial contact with host cells10, are known to interact with the integrins α5 and β1 to enhance the adherence11,12. Furthermore, the bacterium produces cholesteryl α-glucoside derivatives to affect the bacterial adhesion13.

H. pylori is auxotrophic for cholesterol. It assimilates cholesterol into its membrane by taking up cholesterol from epithelial cells of the stomach. Upon uptake, the bacterial cells modify the cholesterol by α-glucosylation. Specifically, the glucosyltransferase encoded by hp0421 catalyzes the transfer of glucose to the 3-hydroxyl group of cholesterol, yielding cholesteryl α-d-glucopyranoside (CG). There is a subsequent modification occurring at O6′ of glucose in CG, i.e., cholesteryl 6′-O-acyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (CAG) or cholesteryl 6′-O-phosphatidyl-α-d-glucopyranoside are made by attaching an acyl or phosphatidyl group, respectively. We previously developed a metabolite-tagging method for characterizing these derivatives with a femto-molar detection limit14. The subsequent analysis led to the findings that these bacteria acquire phospholipids from the membrane of epithelial cells for CAG biosynthesis. The increase in longer CAG acyl chains helped to promote lipid raft clustering in the host cell membranes and thus the delivery of virulence factor CagA into the host cell14.

Herein we report the identification of hp0499 as the gene of cholesteryl α-d-glucopyranoside 6′-acyltransferase (CGAT), as well as characterization of the corresponding recombinant protein. The enzyme is located in the outer membrane of H. pylori, secreted extracellularly in the form of outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), and thus delivered to the host cells to directly produce CAGs there for the lipid raft-mediated enhancement of H. pylori adhesion. Additionally, a potent CGAT inhibitor was discovered to effectively blockade the H. pylori adhesion, demonstrating CGAT to be a potential target of therapeutic intervention.

Results

Acyl chain length of CAG affects bacterial adhesion

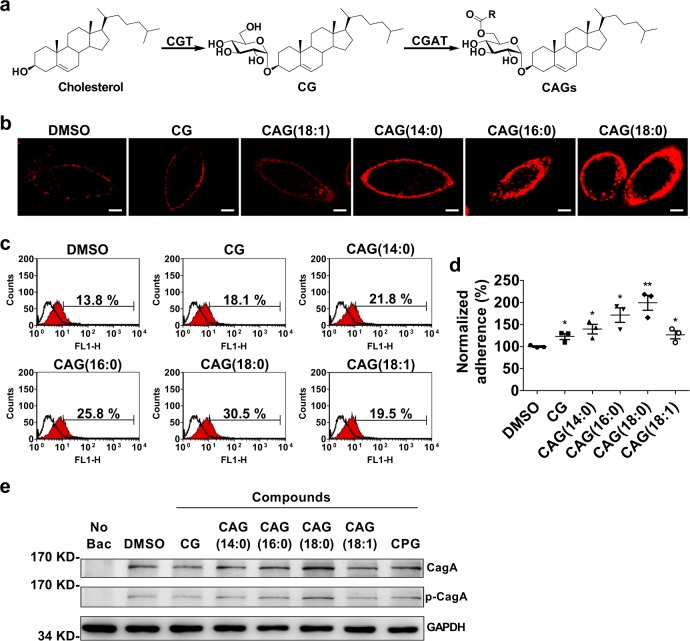

Figure 1a shows the biosynthetic pathway of cholesterol-α-glucosides. Upon uptake of cholesterol, H. pylori employs cholesterol glucosyltransferase (CGT) to convert cholesterol to CG, followed by the reaction of CGAT to catalyze the acyltransfer to produce CAG. We previously demonstrated that CAG, rather than CG or cholesteryl 6′-O-phosphatidyl-α-d-glucopyranoside, was able to promote lipid rafts clustering in the host cell membranes, as well as CagA translocation and phosphorylation14. Wang et al.13 reported that the loss of cholesteryl-α-glucoside derivatives abolished the adhesion of H. pylori to AGS cells13. Both studies provide the impetus to understand if CAG is the key to regulate the bacterial adhesion. Among CG and CAGs of different chain length (such as CAG(14:0), CAG(16:0), CAG(18:0), and CAG(18:1)) added to the culture of AGS cells, CAG(18:0) enhanced the lipid rafts clustering to the highest degree when ganglioside GM1 was utilized to label the formation of lipid rafts (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, AGS cells were treated with each of these CG and CAGs, infected with H. pylori 26695 and then examined for the extent of adhesion by flow cytometry. The result was consistent with that obtained from the lipid rafts study, i.e., the longer the acyl chain was, the higher levels there were in the bacterial adhesion (Fig. 1c, d), CagA translocation, and the corresponding tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, these studies were not favored by unsaturation in the acyl chain, suggesting that the membrane fluidity or packing in the lipid chains appears to be critical.

Fig. 1. CAGs of varied chain length were able to enhance H. pylori adhesion and the corresponding CagA translocation.

a Biosynthetic pathway of CAG in all H. pylori strains where cholesterol α-glucosyltransferase (CGT) and cholesteryl α-d-glucoside acyltransferase (CGAT) consecutively catalyze the reactions to yield cholesteryl α-d-glucopyranoside (CG) and CAG, respectively. The R group of CAG represents O6′-esters of different fatty acids, e.g., myristic acid (14:0), palmitic acid (16:0), stearic acid (18:0), and oleic acid (18:1). b Representative confocal images of lipid rafts clustering in the presence of CG or CAGs with different acyl chain. After AGS cells were treated with CG or CAG (as indicated) for 1 h, the lipid rafts (GM1) were then labeled with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated cholera toxin subunit b (red fluorescence). Confocal images were collected under a Leica SP5 X inverted confocal microscope. Scale bar: 5 μm. c, d Degree of H. pylori adherence to AGS cells is dependent on the acyl chain of CAG. AGS cells were first treated with CG or CAGs (as indicated) for 1 h, infected with H. pylori strain 26695 for another 1 h, and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Adherence was measured as the proportion of adhered AGS cells with H. pylori (%; shown in each plot). The resulting quantitation of cell adherence was normalized in comparison with the control and shown in d. Data are shown as mean ± SD (standard deviation). All statistically significant differences are indicated with asterisks; **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. the control (n = 3). e Effects of CAGs with different acyl chains on CagA translocation and CagA tyrosine phosphorylation that was detected by immunoblotting after the co-culture of AGS cells with H. pylori 26695 as described in (c). Data sources for d are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Uncropped immunoblot images for e are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Identification and characterization of H. pylori CGAT

Previously phospholipids were shown to serve as the precursors for the biosynthesis of CAG and cholesteryl 6′-O-phosphatidyl-α-d-glucopyranoside14. In an attempt of identifying the enzyme to catalyze the formation of CAGs, we performed several gene-knockout strains related to phospholipase, esterase, or acyltransferase (see Methods section for the list of candidates) by inserting a kanamycin-resistance cassette into desirable genes of H. pylori 26695. Among these gene-knockout strains, only Δhp0499 did not produce a detectable level of CAGs, suggesting that the Δhp0499 strain is a CGAT-deficient strain (ΔCGAT) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We additionally prepared the CGAT-knock-in strain by inserting the intact hp0499 gene with a chloramphenicol-resistance cassette to the genome upstream of the aforementioned hp0499-modified sequence. The CGAT-knock-in strain indeed restored the capability of synthesizing CAG (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Both data confirmed that hp0499 is the gene responsible for CAG production.

Two recombinant forms of CGAT were overexpressed in Escherichia coli, including one containing an N-terminal 6x His tag and the other having an N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP-CGAT). Despite several problems initially encountered, such as low expression level, formation of inclusion bodies and protein instability, we finally overcame these difficulties after numerous trials and errors. MBP-CGAT displayed fourfold higher activity than the other His-tagged CGAT (Supplementary Fig. 1b) by using LC-MS analysis to measure CAG(14:0) that resulted from the enzymatic reaction of CG and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine (PE(14:0,14:0)). As a consequence, only MBP-CGAT (hereafter called CGAT) was characterized in the following studies. The enzyme has two substrates, namely phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) as the acyl donor and CG as the acceptor. Since PE contains two acyl chains, we thus utilized PE(d16:0/18:1) (i.e., deuterium-labeled palmitic acid (16: 0) and unlabeled oleic acid (18:1) at a1- and a2-positions of the glycerol moiety, respectively) to identify which acyl chain in the PE was hydrolyzed and transferred to CG. The resulting analysis indicated that CGAT belongs to the family of phospholipase A1 to catalyze the formation of CAG(d16:0) and 1-hydroxy-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (lyso-PE(18:1)), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1c, d, respectively. Furthermore, CGAT was active in the range of pH 3.5–9.0 with an optimum activity at pH 4.5 (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Lineweaver–Burk plot analysis of CGAT steady-state kinetics indicated that the catalysis operates through a sequential rapid-equilibrium random bi-bi mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 1f, g). The values of KCG and KPE were 26.0 and 290 μM, respectively, and the turnover number was close to one per sec (kcat = 58.5 min−1).

Meanwhile, we also examined the metal ion dependence and substrate specificity on phospholipids. Among seven divalent metal ions, the enzyme became the most active in the presence of calcium ion (Supplementary Fig. 1h). CGAT displayed broad specificity for several lipids (Supplementary Fig. 1i, j); in particular, a phosphatidyl moiety is required for the recognition. Acceptable substrates need to have two acyl chains (see the rate difference between PE vs. 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (2-lyso-PE) although they both can be saturated (Supplementary Fig. 1i) or the one at a2-position is unsaturated (Supplementary Fig. 1j). Obviously, CGAT mainly preferred PE (100% relative activity), phosphatidylserine (PS, ~25–50% activity depending on the lipid compositions) and phosphatidylcholine (PC, ~4–17% activity). In consistence with the previous result that CAGs of varied chain length existed in the co-culturing of AGS cells with H. pylori, CGAT accepted all the five phosphatidylcholines of different chain lengths (Supplementary Fig. 1k). We did not examined PEs simply because most PEs are rarely soluble in the assay buffer (100 mM sodium formate, 25 mM CaCl2, pH 4.5).

Cellular locations of CGAT

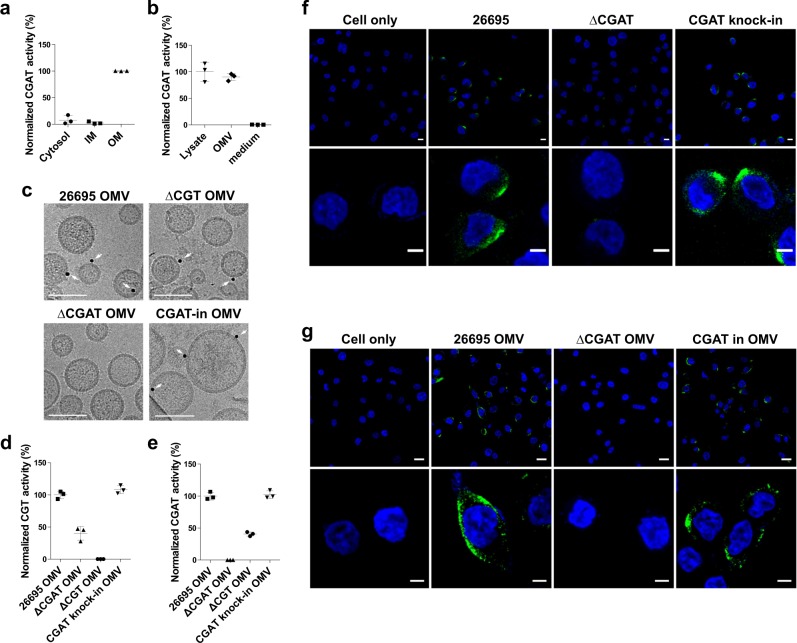

To study the cellular location of CGAT, the cells of H. pylori 26695 were cultured, lysed, and then extracted by N-lauroylsarcosine and n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside to obtain the fractions of cytosol, inner and outer membranes15. Enzyme activity assay was conducted to determine where CGAT is localized. The enzyme was found to exist mainly in the outer membrane, but not in the other locations (Fig. 2a), which is coherent to the proposed idea by Scott et al.16 that most H. pylori surface proteins have high values of isoelectric point to likely resist the acidic environment. The isoelectric point of CGAT is 9.26. Moreover, the CGAT activity was observed in the OMVs, rather than in the culture medium (Fig. 2b), suggesting that CGAT resided in the outer membrane can be enclosed in the OMVs and secreted to the extracellular space. Figure 2c showed the direct evidence from cryo-transmission electron microscopy that CGAT was present in the OMVs isolated from the strains of H. pylori 26695, ΔCGT-knock-out, and CGAT-knock-in, instead of ΔCGAT-knock-out. When these OMVs were isolated from hp0499-containing strains and then surveyed for proteomic analysis, CGAT was shown among a range of 310–420 proteins identified (Supplementary Table 1). Further activity analysis of these OMVs (Fig. 2d, e) concluded that H. pylori OMVs contained the two enzymes CGT and CGAT. As shown by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2f, g, Supplementary Movie 1), CGAT was translocated to AGS cells after the cells had been pretreated with H. pylori 26695 OMVs or infected by H. pylori 26695.

Fig. 2. Cellular location of CGAT.

a, b Cellular location of CGAT was determined by the enzyme activity. a IM and OM stand for the abbreviations of inner and outer membranes, respectively. See Methods section for the procedure to obtain the fractions of cytosol, IM, and OM of H. pylori 26695. b The three fractions were obtained from the same cell number of H. pylori 26695. These fractions were individually incubated for 2 h with the mixture of CG and PE at pH 4.5. The resulting CAG products were analyzed by LC-MS analysis. Data were obtained from three replicates. Data are shown as mean ± SD. c CGAT existing in OMVs was identified by cryo-transmission electron microscopy. OMVs were purified from different H. pylori strains and examined if they contained CGAT that is labeled by immune-gold (shown in black dots and indicated by white arrows). Scale bar: 50 nm. d, e Levels of CGT (d) and CGAT (e) activities in the OMVs that were purified from different H. pylori strains and determined by LC-MS analysis. Data are shown as mean ± SD. f CGAT was shown in the co-culture of AGS cells with different H. pylori strains. After co-culture with H. pylori for 8 h, the cells were fixed and stained with CGAT-specific antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Lower panels showed the magnified images from a part of upper panels. Scale bars denoted 20 (upper) and 5 (lower) μm. g CGAT was shown in the AGS cells with a prior treatment with or without H. pylori 26695 OMV, ΔCGAT OMV, or CGAT-knock-in OMV for 8 h. The cells were then stained as described in (f). Scale bars denote 20 (upper) and 5 (lower) μm. Data sources for a, b, d, and e are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

CGAT is delivered to host cell to enhance H. pylori adhesion

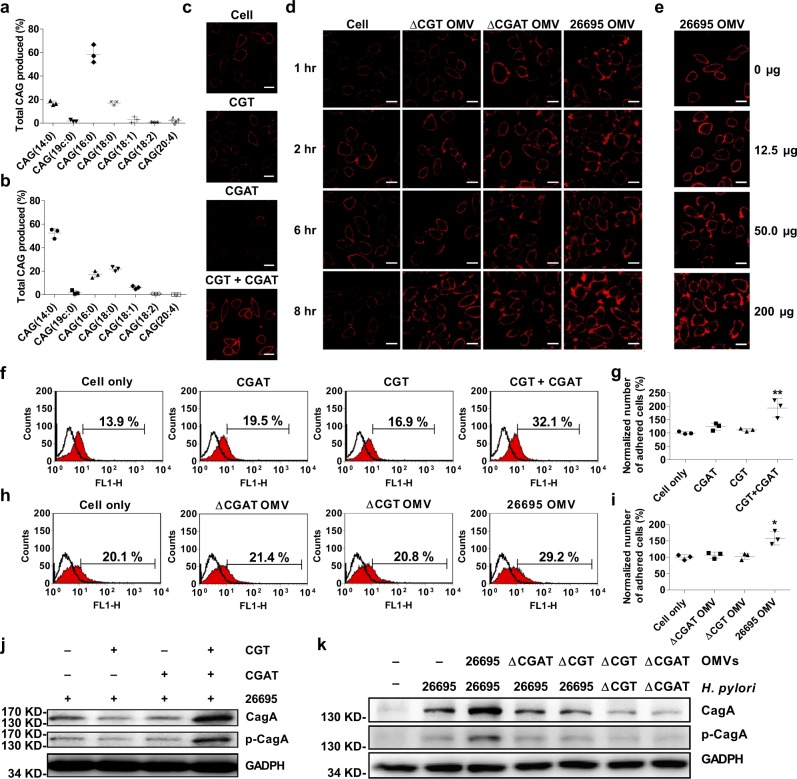

It is known that CAG(14:0) and CAG(19c:0) mainly exist in H. pylori, as the reaction products of CGAT. To understand how the translocated CGAT possibly functions in the host cell, the primary concern is to analyze the CGAT products once the enzyme becomes available in the host cells. We treated AGS cells with recombinant proteins CGT and CGAT both to mimic the circumstances of bacterial infection. There was a significant change in the CAG compositions (Fig. 3a), i.e., most CAGs contain longer fatty acid chains, including (16:0), (18:0), and (18:1), after the treatment of AGS cells with both CGT and CGAT. Apparently the translocated CGAT accepted available PEs or phosphatidylserines in AGS cells. Likewise, the treatment with H. pylori 26696 OMVs also resulted in a similar profile (Fig. 3b). In agreement with the aforementioned observation that CGT and CGAT were delivered to the host cells by the OMVs (Fig. 2f, g), Fig. 3b indicated that the two enzymes, once delivered to the host cells, became functional to synthesize CAGs of longer acyl chains. The result is coherent to the previous report14 that the co-culture of H. pylori with AGS cells generated a significant amount of CAGs containing longer or/and unsaturated acyl chains.

Fig. 3. Enhanced levels in lipid rafts clustering, adhesion, and CagA translocation by the concerted actions of CGAT and CGT.

a, b The compositions of CAGs in AGS cells after the cells were treated with both recombinant CGT and CGAT (a), or with the OMVs of H. pylori 26695 (b). c Enhanced level of lipid raft clustering was observed after AGS cells were treated with both recombinant CGT and CGAT for 8 h. Red fluorescence denotes the lipid rafts. Scale bar: 20 μm. d, e Time- and does-dependent confocal images of lipid raft clustering in AGS cells. d The images were obtained after the cells were treated with the purified OMVs (200 μg) from different H. pylori strains at 1, 2, 6, and 8 h. e The images were generated after the cells were treated with H. pylori 26695 OMVs for 8 h. Red fluorescence denotes the lipid rafts. Scale bar: 20 μm. f, h Enhanced H. pylori adherence to AGS cells after the cells were incubated with recombinant CGT or/and CGAT (f) or with the purified OMVs from different H. pylori strains (h). AGS cells were treated with the enzymes or OMVs for 8 h and then infected with H. pylori 26695 for another 1 h. Adherence was examined by flow cytometry analysis and shown as the proportion of adhered cells with H. pylori (%; shown in each plot). g, i Quantitation of the adhered cells of f and h was normalized in comparison with the negative control, respectively. All statistically significant differences are indicated with asterisks; **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. control group (n = 3). j, k Immunobloting analysis on CagA translocation and the related tyrosine phosphorylation to examine the effect of recombinant enzymes (j) or purified OMVs (k). The procedure was similar to that of f and h. The uncropped images are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4. In a, b, g and i, data are shown as mean ± SD and the data sources are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

The aforementioned enzyme or OMV treatment also enhanced the degree of lipid rafts clustering in a time- (Fig. 3c, d) and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, we had two observations to corroborate the indispensable production of CAGs. There was no enhancement of lipid rafts clustering if only CGT or CGAT was present in the study. Lipid rafts clustering only became evident in the regions to which H. pylori 26695 OMVs were attached, as shown by the real-time imaging (Supplementary Movie 1), in contrast to those without the OMV attachment. Additional examinations on the effect of H. pylori adhesion also showed the consistent trend, such as flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 3f–i), cagA translocation, and the corresponding tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 3j, k). Taken together, these results indicated that the presence of both CGT and CAGT in the host cells is the prerequisite for the enhancement of lipid raft clustering, bacterial adhesion, and the subsequent virulence.

CAGs help to gather adhesion molecules

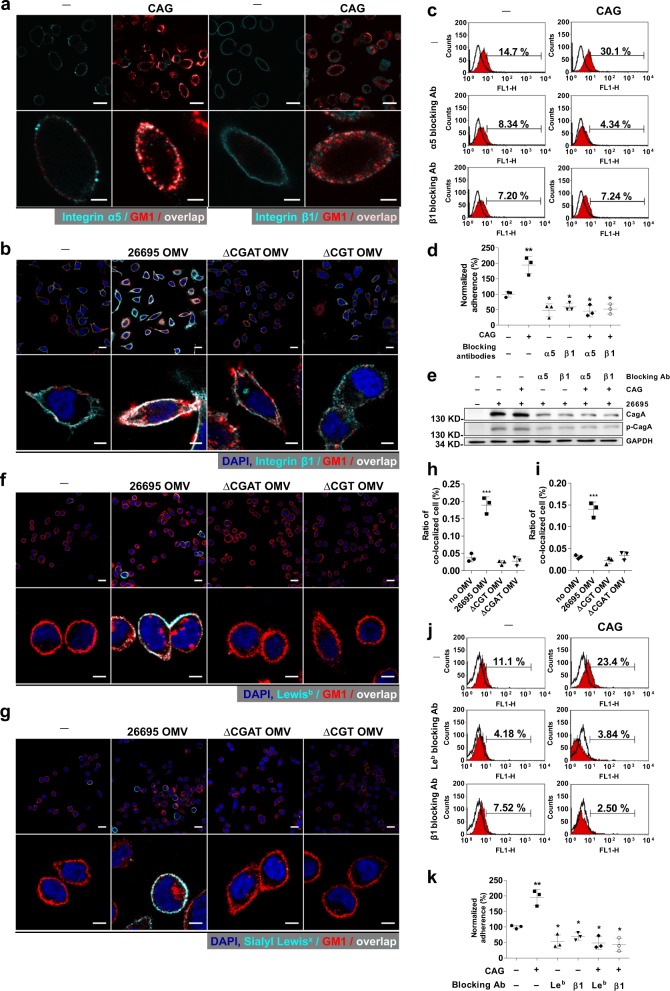

Although lipid rafts clustering and the chemoattraction of cholesterol17 is a driving force for H. pylori to move toward the rafts region, leading to the enhancement of bacterial adhesion, the detailed mechanism still remains unclear. It was reported that integrins α5 and β1 were recruited to the raft region when lipid rafts were clustered in T cells18,19. Both integrins were shown in gastric epithelial cells to interact with T4SS of H. pylori to enhance the bacterial adhesion11. To examine a possible correlation of the integrins with the CAG-induced clustering of lipid rafts, we first found that integrins α5 and β1 were both co-localized with CAG-induced lipid rafts in AGS cells (Fig. 4a). H. pylori 26695 OMVs, rather than those containing CGT or CGAT only, were able to recruit integrin β1 to the raft regions in AGS and KATO III cells (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 2, respectively). Despite enhanced H. pylori adhesion to AGS cells in the presence of CAG(18:0), the adherence and the subsequent CagA translocation were inhibited by integrin α5- or β1-blocking antibodies (Fig. 4c–e).

Fig. 4. Gathering of integrins α5/β1, Lewisb, and sialyl Lewisx by CAG or CAG-containing OMV in the rafts region.

a Integrins α5 and β1 and b Integrin β1 gathered at the rafts region by treatment of AGS cells with CAG (a) or with H. pylori 26695 OMVs (b). AGS cells were treated with CAG(18:0) for 1 h (a) or with OMVs for 8 h (b), and then fixed. Immunofluorescent staining was then applied to indicate lipid rafts (red), integrin α5 or β1 (cyan), and nuclei (blue). The co-localization of the first two is shown in color of fair pink. Scale bars: 20 (upper) and 5 (lower) μm. c–e Effects of integrin-blocking antibodies on H. pylori adhesion, CagA translocation, and the related tyrosine phosphorylation. AGS cells were treated with or without the integrin α5- or β1-blocking antibodies for 1 h, and incubated in the presence or absence of CAG(18:0) for additional 1 h, and then infected with H. pylori 26695. Adherence was measured by flow cytometry analysis (c) as the proportion of adhered cells with H. pylori (%; shown in each plot). The quantitation made in c was summarized in (d). Levels of CagA translocation and CagA tyrosine phosphorylation were detected by immunoblotting and shown in e. f, g Gathering of Lewisb (f) and sialyl Lewisx (g) in the rafts region by treatment of KATO III cells with H. pylori 26695 OMVs. The procedure and staining were similar to those of (b). Scale bars: 20 (upper) and 5 (lower) μm. h and i stand for quantitation of the confocal images made in f and g, respectively. j, k Effect of Lewisb-blocking antibodies on H. pylori adhesion. The procedure was similar to that of c and d. In d, h, i, and k, data are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and shown as mean ± SD and all statistically significant differences are indicated with asterisks; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. the control group (n = 3). Uncropped immunoblot images for e are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Like the integrins, Lewisb and sialyl Lewisx antigens were able to congregate in the rafts region induced by the treatment of H. pylori 26695 OMVs in KATO III cells (that were used instead of AGS cells because the latter cells have extremely low expression of Lewis antigens, including Lewisb and sialyl Lewisx). Figure 4f, h displayed the co-localization of the lipid rafts and Lewisb. Overlapped staining of the lipid rafts and sialyl Lewisx was shown in Fig. 4g, i. Again in these figures, H. pylori 26695 OMVs produced higher co-localization signals than the OMVs isolated from the knockout strains. Likewise, the use of Lewisb- or integrin β1-blocking antibodies also significantly blockaded H. pylori adhesion to KATO III cells in the presence of CAG(18:0), as shown in Fig. 4j, k. These results suggested that CAG-induced clustering of lipid rafts gathered bacterial adhesion-related molecules in the raft regions, such as the integrins, Lewisb, and sialyl Lewisx, resulting in the enhancement of bacterial adhesion.

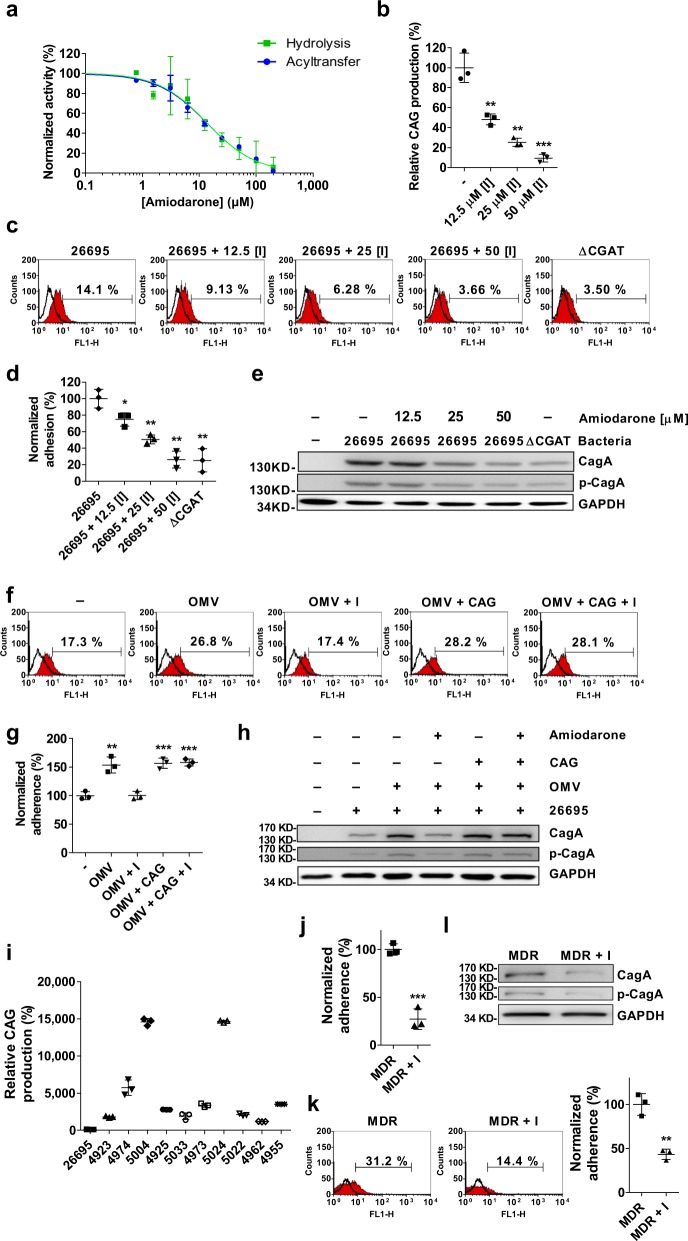

Amiodarone is a CGAT inhibitor to prevent H. pylori adhesion

To study if the enzyme is a target of therapeutic intervention, we screened a number of molecules with the activity assay of CGAT and then identified amiodarone to be a potent inhibitor (IC50 = 13.8 μM, Fig. 5a). The compound was then added to H. pylori-infected AGS cells for further evaluation. As compared to the negative control, 50 μM amiodarone significantly reduced the production of CAG in AGS cells, bacterial adhesion, CagA translocation, and the related tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 5b–e, respectively). Apparently, inhibiting CGAT activity is the key to decrease the virulence of H. pylori. In the presence of OMVs, amiodarone still effectively abolished the adherence of H. pylori to AGS cells (Fig. 5f, g), as well as the related CagA translocation (Fig. 5h). Moreover, we also examined if amiodarone caused any effect other than CGAT inhibition. Before AGS cells were infected with H. pylori, the AGS cells were incubated with (or without) amiodarone and the OMVs that had been treated with CAG(18:0). The result showed no difference in the degree of bacterial infection, and the related CagA translocation (Fig. 5f–h) no matter if amiodarone was present. Meanwhile, we also obtained a similar result in the following study, i.e. no difference in the presence or absence of amiodarone. H. pylori was treated with (or without) amiodarone in the presence of CAG(18:0) before the bacteria infected AGS cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results suggested that amiodarone takes effect only on the CAG-induced changes via inhibition of CGAT activity.

Fig. 5. Amiodarone effectively prevented H. pylori from adhesion.

a Concentration–response plots of the inhibition against the CGAT-catalyzed hydrolysis of PE (14:0,14:0) (green) and the corresponding acyltransfer (blue). b Effect of amiodarone on the CAG formation in H. pylori. H. pylori 26695 cells were treated with amiodarone for 2 days, followed by LC-MS analysis. c–e Effects of amiodarone on H. pylori adhesion (c, d), CagA translocation, and CagA tyrosine phosphorylation (e). After treatment with amiodadrone, H. pylori 26695 or the mutant strain ΔCGAT was cultured with AGS cells for 1 h. Degree of adhesion was measured by flow cytometry analysis (c) and quantitated as the proportion of adhered cells with H. pylori (%, shown in each plot). The quantitation was summarized in (d). f–h Effects of amiodarone and OMVs on H. pylori adhesion (f, g), CagA translocation, and CagA tyrosine phosphorylation (h). AGS cells were treated with or without amiodarone in the presence of H. pylori 26695 OMVs (or the OMVs that had been pretreated with CAG(18:0)) for 8 h and then infected with H. pylori 26695 for another 1 h. f, g Degree of adhesion was shown in the same manner as c and d, respectively. i CAG levels in H. pylori 26695 and ten MDR strains clinically isolated. The bacterial strains were cultured for 2 days, followed by LC-MS analysis. j Effect of amiodarone on the CAG formation (shown by LC-MS analysis) in MDR 5024 strain. k, l Effects of amiodarone on the adhesion of MDR 5024 (k), CagA translocation, and the tyrosine phosphorylation (I). After treatment with amiodarone, MDR 5024 infected AGS cells for 1 h. In j–l, MDR+I denoted the incubation of MDR 5024 with amiodarone. In b, d, g, j and k, all statistically significant differences are indicated with asterisks; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. the control group (n = 3). In a–d, g, i–k, data are shown as mean ± SD, and provided in Supplementary Data 1. Uncropped immunoblot images for e, h, and l are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Furthermore, we examined the CAG levels in ten multiple drug-resistant (MDR) strains of H. pylori that displayed resistance to the treatment of levofloxacin, metronidazole, and clarithromycin. Interestingly, their CAG levels were 10–150 times higher than that of H. pylori 26695 (Fig. 5i). To verify if amiodarone also inhibits the CGAT activity and the related pathogenesis in these resistant strains, one strain (5024) producing the highest CAG level had been incubated with amiodarone before it infected AGS cells. To our delight, at the concentration of 50 μM, aminodarone significantly reduced not only the CAG level (Fig. 5j) but also the bacterial adhesion (Fig. 5k), CagA translocation, and the related tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 5l). These results pave the way for further development of CGAT inhibitors for the purpose of therapeutic intervention.

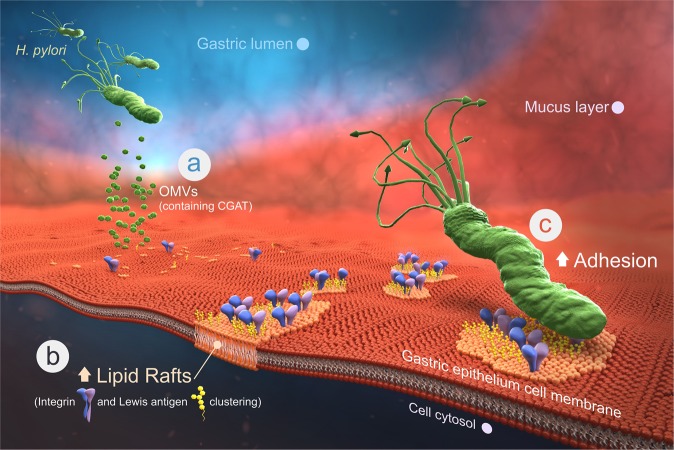

The amiodarone-based anti-adhesion seems to offer an alternative for antimicrobial therapy. CGAT, the product of hp0499, was originally proposed to be an outer membrane phospholipase A that shares 19.7% sequence identity and 35.4% similarity with E. coli outer membrane phospholipase A. Our result indicated that CGAT is indeed a phospholipase A1, but the enzyme additionally catalyzes the acyltransfer to the 6′-OH of CG, resulting in the formation of CAG. In contrast to most bacterial infections where bacterial molecules are propagated to the host cell via passive diffusion or direct cell contact, our result represents a very distinctive scenario. The two enzymes CGT and CGAT are packaged in the OMVs and shipped to the host cell (Fig. 6a). Upon fusion of OMVs with the host cell membranes, the two enzymes are released to directly utilize the necessary substrates to form CAGs in the host cell. Moreover, CAG can be considered as a modified version of cholesterol to modulate the features of the host membranes, including lipid rafts formation and clustering. This helps to gather several adhesion molecules around the rafts region, such as Lewis antigens and integrins α5 and β1 (Fig. 6b). The resulting enhanced interactions thus help H. pylori to adhere much better (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Movie 2). As a consequence, our previous14 and current studies thus demonstrate the intriguing interplay between H. pylori and gastric epithelial cell. The bacteria not only hijack cholesterol and PE from the host to make CAG but also leverage the OMVs to deliver the biosynthetic machinery for the direct and efficient synthesis in the host cell. This leads to a dramatic change on the host cell surface; the enhanced lipid rafts clustering further promotes a higher level of bacterial adhesion.

Fig. 6. Schematic presentation demonstrates how CGAT is involved in H. pylori pathogenesis.

a H. pylori secretes OMVs to deliver the enzymes CGAT and CGT to the host epithelial cells. b Upon translocation, the two enzymes produce human lipid-containing CAGs to enhance lipid raft clustering. c The integrins and Lewis antigens then gather at the raft region, leading to great enhancement in the bacterial adhesion. Therefore, CGAT inhibitor is able to blockade the adhesion, which sheds light on the discovery of a potentially new target to eradicate H. pylori infection.

Discussion

In this study, we identified CGAT as a steryl glycoside acyltransferase. Although this enzyme has been reported to exist in a number of organisms, there is no gene information available20,21. The cloning, expression and characterization of CGAT, to the best of our knowledge not only stands for the first in-depth study of a steryl glycoside acyltransferase but also provides useful information to identify enzymes of the same category and understand their functional roles in other organisms.

In the H. pylori pathogenesis, the proteins of cag-pathogenicity island are associated with integrins α5 and β1 of epithelial cells11,22, which induces T4SS assembly and the subsequent injection of CagA. Given that integrins are generally resided in the basolateral side of epithelial cells, it is intriguing to know the reason why the integrins can interact with the T4SS of H. pylori. Hecht and co-workers23 found that during the infection of E. coli, integrin β1 translocated to the apical side of intestinal epithelial cells after the destruction of tight junction proteins. H. pylori was shown to impair the tight junction24. The bacteria secreted the serine protease HtrA to open cell-to-cell junctions through cleavage of junctional proteins, such as occludin, claudin-8, and E-cadherin in polarized epithelial cells. The opening allowed H. pylori to move into the intercellular space between adjacent cells and eventually reach to basolateral locations25. As a consequence, it is intriguing to examine if and how the presence of CAG correlates with the impairment of tight junction and junctional proteins.

High cholesterol level is known in association with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as atherosclerosis26–30. Therefore, it is intriguing to understand if the cholesterol uptake by H. pylori correlates with CVDs; especially the link of H. pylori seropositivity to CVD has been described in several reports31–35. How the infection of H. pylori influences CVD, however, remains unclear. CAG, considered to be a modified version of cholesterol, was shown to promote lipid rafts clustering in gastric epithelia in this and previous studies14. Caveolae, representing cholesterol- and sphingolipid-enriched invaginations of the plasma membranes, were identified as a potential regulator of vascular dysfunction and heart disease36–39. Moreover, our observation indicated that CAG is rather stable under cell culture conditions, implicating that CAG may not be only available in the infected gastric epithelia, and that their dissemination could promote caveolin-related lipid rafts clustering and thus lead to vascular dysfunction and coronary heart disease. Nevertheless, the levels of CAGs are dynamic depending on the surrounding nutrient condition, not mentioning that different H. pylori strains were found to produce various levels of CAGs. This might explain why there are contradictory observations reporting little or no relevance between H. pylori infection and CVD40–42.

Adherence of H. pylori to the gastric epithelium rendered H. pylori 100–1000 times more resistant to antibiotics than non-adherent bacteria43. The enhanced adhesion of H. pylori was observed in epithelial degeneration and in the presence of mucin depletion symptoms when the patients suffered from gastritis44. Several reports demonstrated that the prevention of bacterial adhesion was able to reduce bacterial survival and virulence45,46; especially the number of bacteria and the related symptoms were significantly diminished47–49. Moreover, a recent study showed that cholesterol-derived glucosides were related to antibiotic resistance50, which was further supported by the extremely high levels of CAGs in the MDR strains that were clinically isolated (Fig. 5i). Since anti-adhesion impedes the binding of bacteria without affecting microbial viability, little or no pressure is applied to select between the wild-type bacteria and mutants. An anti-adhesion therapy thus possibly minimizes the occurrence of drug resistance. It is extremely difficult, however, to develop multiple inhibitors to prevent the bindings of all adhesion molecules given that bacteria usually have several ways to adhere to the host cells. In this study, the CAG-induced clustering of lipid rafts appears to be the driving force to intensify the bacteria–host cell interactions. The development of CGAT inhibitors turns out to be superior to those directly blocking any of the aforementioned interactions. Intriguingly our result indicated that the bacterial adhesion became very limited (Fig. 5d, k) once the CGAT activity was inhibited. Taken together, there are several advantages associated with CGAT inhibitors, such as inhibition of bacterial adhesion, reduction of the OMV fusion to the host cell, and less likely to develop drug resistance. Our discovery of amiodarone thus becomes valuable because this molecule or other CGAT inhibitors can be utilized in conjunction with antibiotics, especially when facing the emerging threat of antibiotic resistance.

Methods

H. pylori strains and bacterial cultures

H. pylori was grown on CDC Anaerobic Blood Agar plates (Becton Dickinson) under microaerobic (Anaeropack Campylo System, Mitsubishi Gas Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) conditions at 37 °C for 2 days. For liquid cultures, H. pylori was grown in Brucella broth (Difco) containing 0.2% β-cyclodextrin (Sigma), 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% IsoVitaleX (Becton Dickinson) for 60 h. For kanamycin-resistant strain selection, 20 μg ml−1 kanamycin was used. For chloramphenicol-resistant strain selection, 5 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol was used. The knockout strains were generated from H. pylori 26695 by inserting antibiotic-resistance cassettes into the target genes via homologous recombination. For knock out of hp0421 (ΔCGT), chloramphenicol-resistance cassette was used. For knock out of hp0499 (ΔCGAT), hp0420 and hp0935, the kanamycin-resistance cassette was used. Three genes (hp0420, hp0935, and hp0499) were selected as the proposed candidates to encode CGAT. hp0420 was related to acyl carrier protein (ACP)-dehydratase/CoA or thioesterase, while hp0935 was considered to be an N-acetyltransferase in H. pylori. hp0499 was previously reported as outer membrane phospholipase A1 in H. pylori. Our data shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 indicated hp0499 to be CGAT. To complement the CGAT mutation, a CGAT-knock-in strain was generated from the strain of ΔCGAT by inserting one intact hp0499 gene with a chloramphenicol-resistance cassette to the upstream of the mutant hp0499 gene locus described above. The correct transformants were obtained by selection with chloramphenicol and kanamycin and then verified by PCR. Clinical isolated multiple drug-resistant (MDR) strains, including 4923, 4974, 5004, 4925, 5033, 4973, 5024, 5022, 4962, and 4955 were obtained from National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan. All these MDR strains are resistant to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin. The resistance breakpoints for clarithromycin, metronidazole and levofloxacin were defined as >0.5, >8, and >1 μg ml−1, respectively51.

Cell lines and cell culture

Mammalian cells were maintained within a humidified environment and under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. AGS (human gastric epithelial, female) and KATO III (human neoplastic epithelial, male) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modification of Eagle’s medium (Gibco, Invitrogen) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%; HyClone) and penicillin/streptomycin (1%; Biological Industries). Both AGS and KATO III cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and were certified by ATCC. ATCC uses morphology-, karyotyping-, and PCR-based approaches to confirm the identity of both cell lines. Cell lines were tested negative for mycoplasma using PCR-based approach. They are not listed in the database of commonly misidentified cell lines.

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this paper are shown as follows. Anti-H. pylori antibody (Abcam, ab20459) was validated and published by Rossez et al.52. Rat anti-integrin β1 clone AIIB2 (Merck, MABT409) was validated its functionally blocking antibody by abrogating AGS cell attachment to fibronectin53. This antibody was validated its immunocytochemistry activity in AGS cells53. Rat anti-integrin α5 clone BIIG2 (DSHB, AB 528155) was validated its blocking function by Damsky and co-workers54. This antibody was validated its immunocytochemistry activity by Fisher and co-workers55. Mouse anti-blood group Lewisb antibody (IgM) T218 (Santa cruz, Sc-59470) was validated and published by Taniguchi et al.56. Mouse anti-CD15s (sialyl Lewisx) that is a monoclonal antibody unconjugated clone CSLEX1 (BD Biosciences, 551344) was validated and published by Walz et al.57. Anti-H. pylori Cag antigen IgG fraction (monoclonal) (Austral Biologicals, HPM-5001-5) and anti-H. pylori Cag antigen IgG fraction (polyclonal) (Austral Biologicals, HPP-5003-9) were validated and published by Tegtmeyer et al.25. Mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody, clone 4G10 (Sigma Millipore, 05-321) was validated and published by Shuai et al.58. Polyclonal rabbit anti-H. pylori CGAT-specific antibody was created in this study and validated by comparing with the positive and negative controls.

In addition, the secondary antibodies are shown as follows: Goat anti-rabbit IgG (pre-adsorbed to 10 nm gold) (Abcam, ab27234), goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (Abcam Ab6721), anti-GAPDH antibody for mAbcam 9484 loading control (HRP) (Abcam Ab9482), goat anti-mouse IgG H&L cross-adsorbed secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488) (Thermo Fisher, A-11001), goat anti-mouse IgG (HRP) (Santa Cruz, sc-2005), goat anti-rabbit (Alexa Fluor 488) (Invitrogen A11034), goat anti-rat IgG H&L cross-adsorbed secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488) (Thermo Fisher, A-11006), and goat anti-mouse IgM CFL488 (Santa cruz, sc-395784).

Sample preparation of H. pylori cholesteryl glucosides

First, 50 μM azido-cholesterol was added to the culture of H. pylori. Then, Folch partitioning was performed using a chloroform/methanol (1/2) extraction for 1 h and another round of chloroform/methanol (2/1) extraction for 1 h, followed by an extraction with 0.9% KCl. The organic layer was evaporated to give a dried residue that was then subjected to a click reaction with 0.25 mM alkyne-dye (4-N-methylamino-1,8-napthalimidopropyne, abbreviated as MAN) in the presence of 1.25 mM tris(benzyltriazolylmethyl)amine (TBTA), 12.5 mM sodium ascorbate, and 0.25 mM CuSO4 at room temperature for 1 h. After the samples were dried, they were stored at −20 °C until HPLC or MS analysis.

Analysis of cholesteryl glucosides

These experiments were performed as previously described14. For ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC, Waters)-MS (Orbitrap Elite, Thermo), a CSM C-18 column was used with a gradient from 30% acetonitrile (ACN) with 20 mM ammonium acetate to a mixture of 90% isopropyl alcohol and 10% ACN with 20 mM ammonium acetate. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive electrospray ion mode set to one full FT-MS scan (m/z 200–1600; 15,000 resolution) and switched to different FT-MS product ion scans (15,000 resolution) for the different precursors of cholesteryl glucoside derivatives. Both collision-induced dissociation and higher energy collisional dissociation were utilized to perform the fragmentation. For sensitive quantitation, multiple reaction monitoring was performed, which detected the fragment of MAN at 366.16 m/z.

Protein overexpression and purification

Plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21 (for CGT and CGAT) for protein overexpression. Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside at a concentration of 0.4 mM was used to induce overexpression at 16 °C for 16–24 h. E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 r.p.m. with a JLA-8.1000 rotor (Beckman). For lysis, pellets were suspended in 20 mM Tris buffer with 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. The cells were then lysed by a cell disruptor (Constant Systems) for 5–10 times. The lysates were centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min to remove cell debris. Ultracentrifugation was then applied at 40,000 r.p.m. with a Type 45 Ti Rotor (Beckman) for 1 h to obtain the membrane fraction. The pellets were stirred overnight in 20 mM Tris buffer with 200 mM NaCl and 1% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside at pH 8.0 and 4 °C. The resulting mixture was applied for ultracentrifugation again to obtain the soluble membrane proteins in the supernatant. Since all the constructs contained His-tags, a Ni-NTA column was used to purify the target proteins. Buffers containing 0.04% DDM and 900 mM imidazole were used to elute the target proteins. Fractions from purification were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were further concentrated by 10 kD Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (Millipore) and quantitated by a DC™ protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). All the proteins were stored at −80 °C in the presence of 20% glycerol.

Cell fractionation of H. pylori

These experiments were performed as previously described15,59–61 with some modifications. Briefly, H. pylori was growth for 2 days and was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for three times and re-suspended in 50 mM HEPES and 0.2 M NaCl buffer. To lyse bacteria, sonication was performed for 30 min alternatively repeated with sonication (10 s) and rest (10 s). The lysed cells were centrifuged at 2000 g for 20 min to remove unlysed cells and other large cell debris. The resulting supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation for 90 min at 82,000 g to obtain the cytoplasmic fraction (supernatant). Pellet containing membrane fractions was further separated to give inner and outer membrane fractions by differential solubilization with N-lauroylsarcosine (Sigma). Resuspension of this pellet by 500 µl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) with 0.6% (w/v) N-lauroylsarcosine was performed. After 20 min of N-lauroylsarcosine incubation and 82,000 g ultracentrifugation for 90 min at 4 °C, the inner membrane fraction was obtained in the supernatant. The pellet containing outer membranes was re-suspended in 500 µl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer and stored for further experiment.

OMV purification

These experiments were performed as previously described62. H. pylori liquid cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 g for 30 min. The medium was filtered by 0.45 μm filters and then subjected to ultracentrifugation at 36,000 r.p.m. in a Type 45 Ti Rotor for 1 h. Pellets were washed with PBS and combined. After another step of ultracentrifugation, the pellets were re-suspended in F12 medium, and protein was quantitated by a DC™ protein assay kit. Samples were stored at −20 °C until used. For imaging of OMVs, OMVs were stained with Vancomycin BODIPY™ FL Conjugate (Thermo Fisher, v34850).

Activity assays of CGAT

CGAT activity was measured by MS-based determination of CAG and lysophosphatidylethanolamine. First, 10 μl of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (PE) (5 mM in ethanol) and 2 μl of CG-MAN (2 mM in ethanol) were evaporated. Second, buffer at a final volume of 100 μl containing 100 mM formic acid and 10 mM EDTA was mixed with dried PE and CG. Third, recombinant CGAT was added to the reaction buffer to a final concentration of 100 nM, followed by sonication of the resulting mixture for 5 s. The reaction was incubated for 16 h before the addition of CaCl2. The resulting mixture was further incubated for 2 h. The reaction was terminated and simply extracted by adding 10 μl of EDTA (0.5 M) and 90 μl of KCl (0.9%) with chloroform/methanol (1/2). The aqueous layer was then extracted again with chloroform/methanol (2/1), and the organic layers were combined and evaporated to give dried residues that were stored at −20 °C until MS analysis.

Protein identification

Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. After normal staining and destaining procedures, the desirable bands were cut into small slices and completely destained with 50% ACN in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) buffer. Reduction was performed by using 50 mM dithiothreitol in 25 mM ABC buffer at 37 °C for 1 h. The alkylation was performed by using 100 mM iodoacetamide in 25 mM ABC buffer at room temperature for 1 h in dark. Gel slices were then washed four times with 50% ACN in 25 mM ABC buffer for 15 min each and dried after the addition of 100% ACN. Lys-C and Trypsin in 25 mM ABC buffer were added sequentially to digest the proteins for 16 h at 37 °C. Peptides were extracted by sonication of the gel slices in 50% ACN and 5% trifluoroacetic acid for 2 min (repeatedly sonicated 10 s and relaxed 10 s) twice. After centrifugation, the supernatants were transferred into new tubes and evaporated. A Zip-Tip desalting procedure was then performed. After the samples had been washed with 0.1% formic acid, they were eluted with 50% ACN and 0.1% formic acid. The samples were then dried and subjected to proteomic analysis. Mascot database searching was used for protein identification. The data were selected with a false discovery rate (FDR) <1%. The searching was performed on the concatenated MGF files with an ion score cutoff of 50 and a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Only peptides with ion scores over 50 were considered (bold peptide), and only proteins with at least one unique peptide (red bold in Mascot) were considered. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE63 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD017518 and 10.6019/PXD017518.

Cryo-TEM imaging

Holey carbon film-covered 300 mesh copper grids (HC300-Cu, PELCO) were glow-discharged in an (Ar, O2)-atmosphere for 10 s on the carbon side. Samples (1–10 mg ml−1) of 4 μl volumes were pipetted onto grids. Grids were blotted in 100% humidity at 4 °C for 3 s and plunge-frozen into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen using a Vitrobot (FEI, Hillsboro, OR). Liquid nitrogen was used to store grids. Grids were then transferred to the electron microscope using a cryostage. Images of OMVs within the holes in the carbon film were obtained by using a Tecnai F20 electron microscope (FEI) at 200 keV with a 70 μm objective aperture. For each exposure, the low dose condition was ~20e− Å−2. Images were taken at 5k or 50k magnification and 2–3 μm defocus and recorded on a 4k × 4k CCD camera (Gatan, USA).

Cell preparation procedure

AGS cells (5 × 105) or KATO III cells (106) were seeded onto 35 mm dishes in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 16 h. Cells were first washed with PBS three times before being treated with 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin in serum-free Ham’s F-12 nutrient medium (F12 meidum) for 1 h. After washes with PBS, cells were collected for further experiments.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

For lipid raft staining, AGS cells were subjected to the cell preparation procedure and incubated with compounds for 1 h; enzymes for 8 h; OMVs from different H. pylori strains for 1, 2, 6, or 8 h; or different amounts of OMVs for 6 h. Lipid rafts (GM1) in AGS cells were then labeled with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated cholera toxin subunit β. Fluorescence microscopy was performed to visualize the clustering of GM1. For CGAT staining, AGS cells were subjected to the cell preparation procedure and treated with OMVs or co-cultured with H. pylori at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 for 8 h. Cells were then fixed (2% formaldehyde) and stained with a specific antibody for CGAT (1:500). Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed to visualize CGAT (Alexa Fluor 488, green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). For integrin or Lewis antigen staining, AGS or KATO III cells were subjected to the cell preparation procedure and treated with CAG(18:0) for 1 h or OMVs for 8 h. Lipid rafts (GM1) in cells were then labeled with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated cholera toxin subunit β for 10 min. Cells were then fixed (2% formaldehyde) and stained with a specific antibody for integrin α5 (BIIG2; 1:125) or β1 (AIIB2; 1:400) or Lewisb antibody (T218; 1:100) or sialyl Lewisx antibody (CSLEX1; 1:1000) at 4 °C for 16 h. Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed to visualize integrins and Lewis antigens (Alexa Fluor 488, green).

Live-cell imaging of AGS cells

AGS cells were subjected to the cell preparation procedure and incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated cholera toxin subunit β (Molecular Probes, USA) for 10 min, washed with PBS three times, and then treated with 200 μg of OMVs that had been labeled by Bodipy FL-vancomycin (1 μM; Green fluorescence) at 37 °C for 8 h. The images of serial optical sections (1024 × 1024 pixels) were obtained under a ×100 Plan-NEOFLUAR lens (laser 543 nm) at 5 min intervals using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. The shown live-cell images were representative of three independent experiments.

Immunoprecipitation and blotting

These experiments were performed as previously described14. AGS cells (6 × 105) were seeded in a six-well tissue culture dish in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Invitrogen) and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. These cells were then treated with 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin in serum-free medium for 1 h and subsequently treated with compounds for 1 h, enzymes for 8 h, or OMVs from different H. pylori strains for 8 h. These cells were infected with H. pylori 26695 at an MOI of 50 at 37 °C for 1 h. CagA translocation and CagA tyrosine phosphorylation were detected by immunoblotting. After infection of AGS cells with H. pylori, cells were washed three times with PBS and collected with a cell scraper. To detect the CagA internalized into AGS cells, saponin was used to lyse AGS cells while keeping the bacteria intact. The AGS cells were gently lysed with PBS containing 0.1% saponin, protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, USA), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, USA) for 10 min at room temperature. The cell debris and intact bacteria were separated from the soluble fraction by centrifugation (6000 g for 5 min), and the solute was filtered with a 0.22-μm-pore filter to yield human cell proteins and the internalized CagA. The saponin lysis procedure was also performed on H. pylori 26695 alone to make sure that this procedure did not release cytoplasmic proteins from H. pylori. Filtrate (100 μg) was immunoprecipitated by using 10 μg of rabbit anti-CagA polyclonal antibody (Austral Biologicals, USA) and 30 μl of Protein A Plus Agarose (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 4 °C overnight. The obtained precipitates were washed three times with immunoprecipitation buffer (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% TX-100, pH 7.4) and once with TBS buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris, 2% SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.05% brilliant blue R, pH 6.8) at 95 °C for 10 min. The resulting samples were resolved by 6% SDS-PAGE, and the bands were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) BSA in TBS buffer containing 0.01% Tw-20 at room temperature for 1 h and incubated overnight with mouse monoclonal anti-CagA (Austral Biologicals; 1:2000), mouse monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10, Millipore; 1:2000) or mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (ab9482, Abcam, UK; 1:5000) at 4 °C. The blots were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) at a 1:5000 dilution, and the proteins of interest were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence assay (WBKLS0500, Millipore).

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells treated with compounds, enzymes, OMVs, blocking antibodies, or inhibitors were infected with H. pylori 26695 (MOI = 50) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the cells were washed to remove non-adherent bacteria, they were detached with 2 mM EDTA and fixed with 2% formaldehyde. Cells with plasma membrane-associated H. pylori bacteria were stained with rabbit anti-H. pylori antibody (Abcam, 1:1,000) at 4 °C for 16 h and then washed with PBS. The secondary antibody was fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen, 1:1000), which was applied at 4 °C for 1 h, and the samples were then washed with PBS. Cells were analyzed by a flow cytometry system (BD FACSCalibur Calibur Flow Cytometer 4 Color). BD FACStation Software (Version 3.3) was used for the data acquisition. Adherence was quantitated in terms of the proportion of cells with adherent H. pylori. At least over 10,000 cells were collected. For gating strategy, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, cell debris was first removed by gating the main cell population using the FSC/SSC gating. Mock-treated cells (cells only without bacterial infection) that had been treated with the same staining procedure as aforementioned were used to distinguish the boundary between the positive or negative staining populations. An identical threshold was applied for all samples within the same cell line.

Statistics and reproducibility

The results are expressed as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). For the graphs, data were combined from at least three biological independent experiments. Statistical significance between two samples was tested by an unpaired t-test using Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All statistically significant differences are indicated with asterisks; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (not significant, p > 0.05).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank the following facilities in Academia Sinica to support the related experiments, including Imaging & Cell Biology Core Facility at the Institute of Biological Chemistry (for assistance with confocal microscopy), Metabolomics Facility of the Scientific Instrument Center (MS analyses), Cryo-EM Center (Cryo-EM studies). Academia Sinica (AS-SUMMIT-108) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (108-2113-M-001-001) financially supported this work.

Author contributions

C.-H.L. conceived and guided the study. H.-M.J. designed and performed all experiments. Y.-C.C. designed and constructed bacterial knockout strains and recombinant proteins. T.-C.Y. performed all cellular experiments. L.-L.O. prepared OMVs. S.M. designed and performed some cellular experiments. A.B.A. performed subcellular fractionation. M.-S.W. provided the clinical H. pylori strains. K.-K.T.M. and J.G.-H. provided CG and several CAGs for the cellular studies. C.-H.L., Y.-C.C., and H.-M.J. wrote the paper.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request. All source data in the main figures are available in Supplementary Data 1 and 2. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE63 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD017518 and 10.6019/PXD017518. Full blots are shown in Supplementary Information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Kwok-Kong Tony Mong, Chun-Hung Lin.

Contributor Information

Kwok-Kong Tony Mong, Email: tmong@mail.nctu.edu.tw.

Chun-Hung Lin, Email: chunhung@gate.sinica.edu.tw.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s42003-020-0855-y.

References

- 1.Suerbaum S, Josenhans C. Helicobacter pylori evolution and phenotypic diversification in a changing host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:441–452. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stolte M, Meining A. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Oncologist. 1998;3:124–128. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.3-2-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser MJ, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mobley HLT. Defining Helicobacter pylori as a pathogen: strain heterogeneity and virulence. Am. J. Med. 1996;100:2S–11S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)80223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yong X, et al. Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA promotes tumorigenesis of gastric cancer via multiple signaling pathways. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015;13:30. doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0111-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnqvist, A. In Helicobacter Pylori Research: From Bench to Bedside (eds Backert, S. & Yamaoka, Y.) (Springer, Japan, 2016).

- 7.Lindén S, et al. Strain- and blood group-dependent binding of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric MUC5AC glycoforms. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1923–1930. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aspholm-Hurtig M, et al. Functional adaptation of BabA, the H. pylori ABO blood group antigen binding adhesin. Science. 2004;305:519–522. doi: 10.1126/science.1098801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheu BS, et al. Interaction between host gastric Sialyl-Lewis X and H. pylori SabA enhances H. pylori density in patients lacking gastric Lewis B antigen. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pachathundikandi SK, Tegtmeyer N, Backert S. Signal transduction of Helicobacter pylori during interaction with host cell protein receptors of epithelial and immune cells. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:454–474. doi: 10.4161/gmic.27001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwok T, et al. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature. 2007;449:862–866. doi: 10.1038/nature06187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backert S, Clyne M, Tegtmeyer N. Molecular mechanisms of gastric epithelial cell adhesion and injection of CagA by Helicobacter pylori. Cell Commun. Signal. 2011;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang HJ, Cheng WC, Cheng HH, Lai CH, Wang WC. Helicobacter pylori cholesteryl glucosides interfere with host membrane phase and affect type IV secretion system function during infection in AGS cells. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;83:67–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jan HM, et al. Metabolic labelling of cholesteryl glucosides in Helicobacter pylori reveals how the uptake of human lipids enhances bacterial virulence. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:6208–6216. doi: 10.1039/C6SC00889E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filip C, Fletcher G, Wulff JL, Earhart CF. Solubilization of the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli by the ionic detergent sodium-lauryl sarcosinate. J. Bacteriol. 1973;115:717–722. doi: 10.1128/JB.115.3.717-722.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott D, Weeks D, Melchers K, Sachs G. The life and death of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1998;43:S56–S60. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.2008.S56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wunder C, et al. Cholesterol glucosylation promotes immune evasion by Helicobacter pylori. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1030–1038. doi: 10.1038/nm1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell JS, Kanca O, McIntyre BW. Lipid microdomain clustering induces a redistribution of antigen recognition and adhesion molecules on human T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2737–2744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell JS, Brown WS, Woodside DG, Vanderslice P, McIntyre BW. Clustering T-cell GM1 lipid rafts increases cellular resistance to shear on fibronectin through changes in integrin affinity and cytoskeletal dynamics. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2009;87:324–336. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grille S, Zaslawski A, Thiele S, Plat J, Warnecke D. The functions of steryl glycosides come to those who wait: recent advances in plants, fungi, bacteria and animals. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010;49:262–288. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrer A, Altabella T, Arró M, Boronat A. Emerging roles for conjugated sterols in plants. Prog. Lipid Res. 2017;67:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimenez-Soto LF, et al. Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion apparatus exploits beta1 integrin in a novel RGD-independent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000684. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muza-Moons MM, Koutsouris A, Hecht G. Disruption of cell polarity by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli enables basolateral membrane proteins to migrate apically and to potentiate physiological consequences. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:7069–7078. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7069-7078.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wroblewski LE, et al. Helicobacter pylori dysregulation of gastric epithelial tight junctions by urease-mediated myosin II activation. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:236–246. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tegtmeyer N, et al. Helicobacter pylori employs a unique basolateral type IV secretion mechanism for CagA delivery. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:552–560.e555. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilen O, Kamal A, Virani SS. Lipoprotein abnormalities in South Asians and its association with cardiovascular disease: current state and future directions. World J. Cardiol. 2016;8:247–257. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jose PO, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;64:2486–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misra A, Shrivastava U. Obesity and dyslipidemia in South Asians. Nutrients. 2013;5:2708–2733. doi: 10.3390/nu5072708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misra A, Luthra K, Vikram NK. Dyslipidemia in Asian Indians: determinants and significance. J. Assoc. Physicians India. 2004;52:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand SS, et al. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE) Lancet. 2000;356:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabata N, et al. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in patients with interleukin-1 polymorphisms is significantly associated with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0166240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schottker B, Adamu MA, Weck MN, Muller H, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori infection, chronic atrophic gastritis and major cardiovascular events: a population-based cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park MJ, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and the coronary artery calcium score in a screening population. Gut Liver. 2011;5:321–327. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chmiela M, et al. A link between Helicobacter pylori and/or Chlamydia spp. infections and atherosclerosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003;36:187–192. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kowalski M, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in coronary artery disease and effect of its eradication on coronary lumen reduction after percutaneous coronary angioplasty. Dig. Liver Dis. 2001;33:222–229. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(01)80711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forrester SJ, et al. Caveolin-1 deletion prevents hypertensive vascular remodeling induced by angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2017;69:79–86. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sellers SL, Trane AE, Bernatchez PN. Caveolin as a potential drug target for cardiovascular protection. Front. Physiol. 2012;3:280. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gratton JP, Bernatchez P, Sessa WC. Caveolae and caveolins in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2004;94:1408–1417. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129178.56294.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:31–39. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda A, Iso H, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Tsugane S. The combination of Helicobacter pylori- and cytotoxin-associated gene-A seropositivity in relation to the risk of myocardial infarction in middle-aged Japanese: The Japan Public Health Center-based study. Atherosclerosis. 2013;230:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogha M, et al. Is Helicobacter pylori infection a risk factor for coronary heart disease? ARYA Atheroscler. 2012;8:5–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adiloglu AK, Can R, Kinay O, Aridogan BC. Infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae but not Helicobacter pylori is related to elevated apolipoprotein B levels. Acta Cardiol. 2005;60:599–604. doi: 10.2143/AC.60.6.2004930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Megraud F, Trimoulet p, Lamouliatte H, Boyanova L. Bactericidal effect of amoxicillin on Helicobacter pylori in an in vitro model using epithelial cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:869–872. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.5.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hessey SJ, et al. Bacterial adhesion and disease activity in Helicobacter associated chronic gastritis. Gut. 1990;31:134–138. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ofek I, Hasty DL, Sharon N. Anti-adhesion therapy of bacterial diseases: prospects and problems. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003;38:181–191. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klemm P, Vejborg RM, Hancock V. Prevention of bacterial adhesion. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;88:451–459. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2805-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langermann S, et al. Prevention of mucosal Escherichia coli infection by FimH-adhesin-based systemic vaccination. Science. 1997;276:607–611. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mysore JV, et al. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in rhesus monkeys using a novel antiadhesion compound. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1316–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Cervantes LE, Ramos P, Chavez-Munguia B, Newburg DS. Campylobacter jejuni binds intestinal H(O) antigen (Fuc alpha 1, 2Gal beta 1, 4GlcNAc), and fucosyloligosaccharides of human milk inhibit its binding and infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14112–14120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207744200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qaria MA, et al. Roles of cholesteryl-alpha-glucoside transferase and cholesteryl glucosides in maintenance of Helicobacter pylori morphology, cell wall integrity, and resistance to antibiotics. MBio. 2018;9:e01523–01518. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01523-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang YX, et al. Primary antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from patients with dyspeptic symptoms in Beijing: a prospective serial study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2786–2792. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossez Y, et al. Almost all human gastric mucin O-glycans harbor blood group A, B or H antigens and are potential binding sites for Helicobacter pylori. Glycobiology. 2012;22:1193–1206. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hutton ML, et al. Helicobacter pylori exploits cholesterol-rich microdomains for induction of NF-kappaB-dependent responses and peptidoglycan delivery in epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:4523–4531. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00439-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hall DE, et al. The alpha 1/beta 1 and alpha 6/beta 1 integrin heterodimers mediate cell attachment to distinct sites on laminin. J. Cell Biol. 1990;110:2175–2184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Damsky CH, Fitzgerald ML, Fisher SJ. Distribution patterns of extracellular matrix components and adhesion receptors are intricately modulated during first trimester cytotrophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway, in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:210–222. doi: 10.1172/JCI115565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taniguchi A, Suga R, Matsumoto K. Expression and transcriptional regulation of the human alpha1, 3-fucosyltransferase 4 (FUT4) gene in myeloid and colon adenocarcinoma cell lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;273:370–376. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walz G, Aruffo A, Kolanus W, Bevilacqua M, Seed B. Recognition by ELAM-1 of the sialyl-Lex determinant on myeloid and tumor cells. Science. 1990;250:1132–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.1701275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shuai K, Stark GR, Kerr IM, Darnell JE., Jr. A single phosphotyrosine residue of Stat91 required for gene activation by interferon-gamma. Science. 1993;261:1744–1746. doi: 10.1126/science.7690989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hobb RI, Fields JA, Burns CM, Thompson SA. Evaluation of procedures for outer membrane isolation from Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiology. 2009;155:979–988. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.024539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lester J, et al. Characterization of Helicobacter pylori HP0231 (DsbK): role in disulfide bond formation, redox homeostasis and production of Helicobacter cystein-rich protein HcpE. Mol. Microbiol. 2015;96:110–133. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ge Z, Doig P, Fox JG. Characterization of proteins in the outer membrane preparation of a murine pathogen, Helicobacter bilis. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:3502–3506. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3502-3506.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parker H, Chitcholtan K, Hampton MB, Keenan JI. Uptake of Helicobacter pylori outer membrane vesicles by gastric epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:5054–5061. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00299-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perez-Riverol Y, et al. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D442–D450. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request. All source data in the main figures are available in Supplementary Data 1 and 2. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE63 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD017518 and 10.6019/PXD017518. Full blots are shown in Supplementary Information.