Abstract

Diets rich in sugar and saturated fat are associated with cognitive impairments in both humans and rodents with several potential mechanisms proposed. To test the involvement of diet-induced pro-inflammatory signaling, we exposed rats to a high-fat, high-sugar cafeteria diet, and administered the anti-inflammatory antibiotic minocycline. In the first experiment minocycline was coadministered across the diet, then in a second, independent cohort it was introduced following 4 weeks of cafeteria diet. Cafeteria diet impaired novel place recognition memory throughout the study. Minocycline not only prevented impairment in spatial recognition memory but also reversed impairment established in rats following 4 weeks cafeteria diet. Further, minocycline normalized diet-induced increases in hippocampal pro-inflammatory gene expression. No effects of minocycline were seen on adiposity or dietary intake across the experiments. Cafeteria diet and minocycline treatment significantly altered microbiome composition. The relative abundance of Desulfovibrio_OTU31, uniquely enriched in vehicle-treated cafeteria-fed rats, negatively and significantly correlated with spatial recognition memory. We developed a statistical model that accurately predicts spatial recognition memory based on Desulfovibrio_OTU31 relative abundance and fat mass. Thus, our results show that minocycline prevents and reverses a dietary-induced diet impairment in spatial recognition memory, and that spatial recognition performance is best predicted by changes in body composition and Desulfovibrio_OTU31, rather than changes in pro-inflammatory gene expression.

Subject terms: Hippocampus, Physiology, Diseases

Introduction

While it is known that excessive consumption of diets high in saturated fat and sugar is associated with cognitive impairment1–3 and increased risk of neurodegenerative disease4,5, the underlying causative mechanisms remain controversial. Substantial evidence indicates that such diets are associated with low-grade systemic6,7 and central8 inflammation, and diet-induced hippocampal pro-inflammatory changes are associated with impaired performance on hippocampal-dependent cognitive tasks in rats9–13 and mice14–16. However, other mechanisms, such as increased oxidative stress13, reduced sirtuin expression12 and neurotrophic factors15,17,18, and altered synaptic plasticity19 have also been implicated in diet-induced cognitive impairment. Therefore, further examination of the role of pro-inflammatory signaling in diet-induced cognitive impairment is warranted.

Minocycline, a bacteriostatic antibiotic and immunomodulator, readily crosses the blood brain barrier and inhibits microglial activation and proliferation20. Its administration effectively restores cognition in rodent models of chronic stress21, cranial irradiation22, aging23, and systemic bacterial infection24. Here, we sought to determine whether minocycline was also an effective treatment for spatial recognition memory impairments in rats fed a cafeteria diet. Two studies have previously examined the effect of minocycline on cognition in obese mice, using a passive avoidance25 and spatial recognition and navigation tasks26. The first task confounds hippocampal contextual learning with locomotor and anxiety-like behavior, the latter of which was shown to be reduced in an elevated plus maze task in these same mice25, and both studies administered minocycline for no more than 2 weeks25,26. It is unknown whether minocycline can prevent diet-induced cognitive impairment in rodents prior to induction of obesity or reverse defects once these arise, and whether these drug-induced improvements are long-lasting.

In addition, minocycline has antibiotic activity and has been recently reported to reduce some effects of high-fat diet in rats through altering food intake and the gut microbiome composition27. Given the role of the gut microbiome in diet-induced cognitive impairment11,28,29, it is important to examine the effects of minocycline on microbiome composition and to investigate potential behavioral associations as these have not been previously studied.

First, we aimed to determine whether chronic oral minocycline treatment would protect rats from developing diet-induced cognitive impairment (experiment 1), as well as reverse already established cafeteria diet-induced cognitive impairment (experiment 2). Secondly, we investigated potential mechanisms by which minocycline may be modulating cognition. Specifically, we examined associations between spatial recognition memory and metabolic impairments, white adipose (WAT) and hippocampal pro-inflammatory signaling gene expression, and changes to fecal microbiome composition. Finally, we used predictive modeling to identify key predictors of spatial recognition memory.

Methods

Ethics statement

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of the University of New South Wales in accordance with the guidelines for the use and care of animals for scientific purposes (Australian National Health and Medical Research Council).

Subjects and experimental manipulations

One hundred and eight male Sprague–Dawley rats aged 8 weeks (190–220 g; Animal Resource Centre, Australia) were housed at 18–22 °C (12 h light/dark cycle) and maintained ad libitum on water and standard chow (11 kJ/g; 65% carbohydrate, 22% protein and 13% fat; Premium Rat Maintenance diet, Gordon’s Stockfeeds, Australia).

Following acclimatization, weight-matched groups were randomly allocated to treatments. Diets comprised standard chow or cafeteria diet (full protocol in ref. 30,) consisting of chow and water, 10% sucrose solution and a selection of cakes, biscuits and protein sources (e.g., meat pie, dim sims, and dog food) that varied daily.

Body weight and food intake were measured twice weekly. Body composition was assessed by EchoMRI-900 (EchoMRI LLC, USA). For intake measures, foods were weighed before presentation, and reweighed 24 h later. Energy intake was calculated from manufacturers’ information assuming equal intake per cage.

Minocycline hydrochloride (Chemlin, China; 40 mg/kg/day) was delivered via daily syringe feeding31,32. Minocycline was suspended in vehicle (golden syrup; CSR Sugar, Australia; diluted to 20–35% sucrose solution with water) immediately before administration.

Experiment 1 (Fig. 1a) examined the effects of minocycline administration during cafeteria diet exposure on spatial recognition impairment. Following a 2 × 2 design (n = 12 rats/group), rats were exposed to vehicle (Veh) or minocycline (Mino) for 3 days (to monitor for antibiotic-induced gastrointestinal symptoms) while consuming standard chow (C) before placing half the rats onto cafeteria diet (Caf) for 6 weeks while maintaining drug treatment.

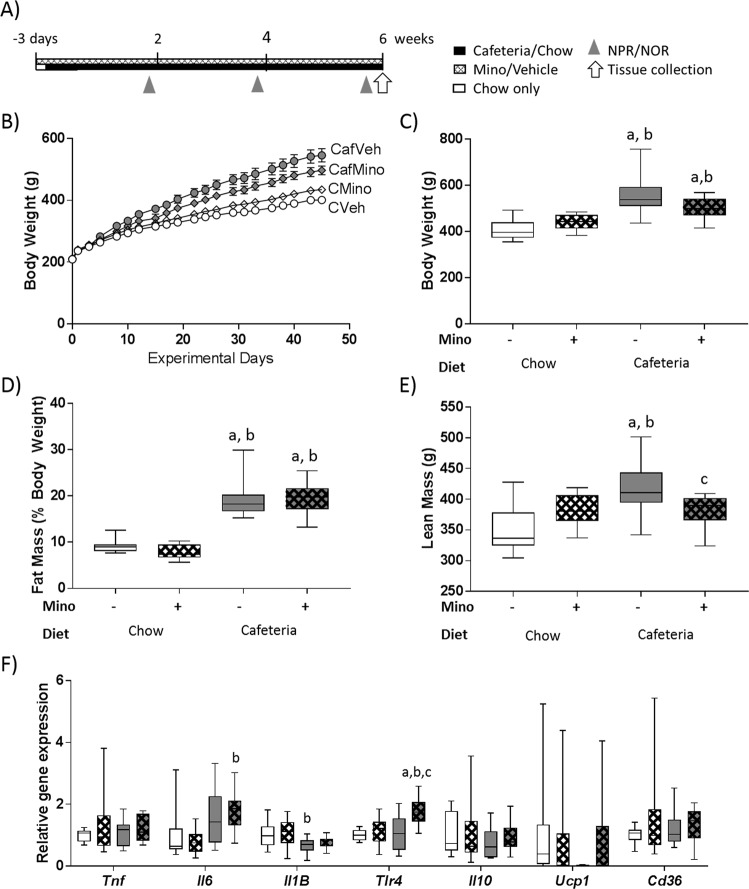

Fig. 1. Minocycline treatment does not affect adiposity or white adipose pro-inflammatory gene expression in cafeteria-fed rats.

a Timeline for study. b Body weight over the experiment, and c body weight, d fat mass (as a percentage of body weight), and e absolute lean mass following 6 weeks of diet exposure. f Pro- and anti-inflammatory and uncoupling protein 1 gene expression in retroperitoneal white adipose tissue. Cd36 cluster of differentiation 36, Il6 interleukin-6, Il1B interleukin-Iβ, Il10 interleukin-10, Tlr4 toll-like receptor 4, Ucp1 uncoupling protein 1. Data expressed as box-and-whisker plots (min, IQR, max); n = 11–12; data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-adjusted post hoc testing. ap < 0.05 relative to CVeh, bp < 0.05 relative to CMino, cp < 0.05 relative to CafVeh.

Experiment 2 followed a 2 × 2 design (n = 12 rats/group) and investigated the effect of minocycline administration on rats with an established diet-induced spatial recognition impairment. Rats were assigned to C or Caf for 4 weeks, before half were placed on either Veh or Mino for an additional 4 weeks while maintaining their diet. A fifth group (n = 12, CafMino*) was placed onto both cafeteria diet and minocycline for the final 4 weeks, to replicate the same conditions of Experiment 1.

Behavior—novel object and novel place tasks

Hippocampal-dependent spatial and perirhinal-dependent object recognition memory were assessed in a square arena (60 cm × 60 cm × 60 cm; 40 lux) using novel place (NPR) and novel object (NOR) tasks, respectively33,34. Previously, we showed that cafeteria-fed rats exhibit impaired NPR but intact NOR12,13. For the NOR, objects were matched on volume and color, and differed in shape and material. Object type and locations were counterbalanced across treatment groups and across time, and videos were relabeled to blind the experimenter prior to scoring. For 2 days prior to the first task rats were exposed to the empty arena for 10 min each day.

Both NOR and NPR tasks consisted of familiarization, retention and test phases. In the familiarization phase, rats were placed into the arena with two identical novel objects and allowed to explore for 5 min. They returned to their home cage for a 5-min retention period, then the 3-min test began. For the NOR, objects were placed in the same locations as familiarization but one object was novel while the other was identical to that used during familiarization. In the NPR, the objects were identical to those shown during familiarization but one object was placed in a novel location, the other remained in its original position. Exploration ratio was calculated for each rat as (novel exploration time)/(novel + familiar exploration time). Following testing, fecal samples were collected either from the arena or the rectum.

Sample collection

Rats were deeply anaesthetized (ketamine/xylazine 15/100 mg/kg intraperitoneally) and body weight, naso-anal length, girth, and blood glucose measured. Cardiac puncture was performed and rats were decapitated. The dorsal hippocampus was dissected (within a coronal block defined by rostro-caudal limits of the Circle of Willis). Liver, retroperitoneal and gonadal WAT were dissected and weighed. Feces were collected from the distal descending colon. Samples and plasma were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Plasma hormone, triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein measurements

Plasma leptin, insulin, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations were determined according to manufacturer’s instructions (CrystalChem Inc., USA). Plasma triglyceride concentration was determined using triglyceride reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Australia) against glycerol standard (Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd., Australia).

RNA extraction and gene-expression assays

RNA was extracted from dorsal hippocampus and retroperitoneal WAT using TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd., Australia). Following DNAse I treatment (Merck, Australia) 1.5 or 2 µg of RNA (WAT and hippocampus, respectively) were reverse transcribed to cDNA (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). Gene expression was assessed using TaqMan inventoried gene expression assays (Life Technologies Australia Pty Ltd, Australia). Genes of interest (full list in Supplementary Table 1) were normalized using the geometric mean of the most stable housekeeping genes (Ywhaz and Hprt1 for hippocampus, Gapdh and Hprt1 for WAT) identified by Normfinder35. Analysis of relative gene expression was performed using the ∆∆CT method normalized to an independent calibrator 36.

Statistical analyses

Results were analyzed using Welch-corrected t tests or two-way between-subjects ANOVA, while measures over time were analyzed using three-way mixed ANOVA. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using a Tukey adjustment where appropriate (THSD). Where data violated homoscedasticity of variance, log transformations were employed. Pearson correlations assessed the relationship between place task performance and measures of interest in the study. All analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (Australia).

Fecal DNA extraction, microbiome community sequencing, and statistical analyses

DNA extraction was performed using the PowerFecal DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and composition of the microbial communities was assessed by Illumina amplicon sequencing (2 × 250 bp MiSeq chemistry, V4 region, 515F-806R primer pair) using a standard protocol37. The sequence data were then analyzed using MOTHUR38 based on modified commands from MiSeq SOP39. Sequence data were subsamples to n = 10,038 total clean reads/sample.

Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) correlations and LEfSe analyses were completed using Calypso40, where multiple testing was corrected using the Benjamini Hochberg false-discovery rate procedure (FDR)41. Alpha diversity metrics were obtained from Calypso and analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics, while nonmetric multidimensional scaling and DESeq2 were performed using R. The R package Phyloseq42 was used for the negative binomial Walk test in DESeq243 with an FDR correction applied.

Distanced-based linear modeling, nonmetric multidimensional scaling and PERMANOVA were completed using Primer (version 6; Primer-E Ltd., UK44; all using a Bray–Curtis similarity matrix at the OTU level). Marginal and sequential distance-based linear modeling interrogate the unique and conditional contributions of each predictor variable to the variance in the Bray–Curtis similarity matrix.

OTU abundances were analyzed using SPSS with Kruskal–Wallis tests when necessary, followed by nonparametric Bonferroni–Dunn post hoc testing. OTUs of interest were identified using SINA Aligner 45.

Predictive modeling

NPR performance was predicted from models based on data from Experiment 1 along with CafMino* yielding 112 observations from N = 60 rats which were combined into a training dataset comprising NPR, NOR, body composition, OTUs associated with NPR performance, and bacterial species richness and evenness. Multiple regression models, random forest algorithms46 and gradient boosting algorithms47 were trialed in R, and the best model (multiple regression: Place task performance ~ Fat mass + Desulfovibrio_OTU31) was selected. This model was then assessed on the test dataset, comprising all observations from Experiment 2 except the CafMino* group (89 observations from N = 48 rats).

Results

Minocycline reduced lean mass without changing energy intake, adiposity or white adipose gene expression in cafeteria-fed rats (Experiment 1)

Terminal body weight (Fig. 1c) was significantly elevated in CafVeh rats compared to chow-fed groups (both p’s < 0.001) as well as CafMino rats compared to CVeh (p < 0.001) and CMino (p = 0.036: THSD; DietXDrug: F1,43 = 7.116, p = 0.011). Cafeteria diet exposure significantly elevated total energy, carbohydrate and fat intake irrespective of minocycline treatment with no group differences in absolute protein intake (Table 1). All rats gained weight over the 6-week study (Fig. 1b).

Table 1.

Energy intake, anthropometric measures at tissue collection and plasma measures.

| Measure | Chow diet | Cafeteria diet | p Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Minocycline | Vehicle | Minocycline | Diet | Mino | Interaction | |

| Total energy and macronutrient intake (average kJ/rat) | |||||||

| Total energy intake | 14432 ± 282 | 15292 ± 989 | 45584 ± 2628a,b | 41886 ± 719a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Total protein intake | 3140 ± 67 | 3269 ± 211 | 3768 ± 150a | 3355 ± 64 | 0.023 | – | – |

| Total carbohydrate intake | 9419 ± 200 | 9806 ± 632 | 25292 ± 1407a,b | 23574 ± 334a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Total fat intake | 1952 ± 41 | 2032 ± 131 | 13400 ± 719a,b | 11998 ± 373a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Anthropometric measures (cm) | |||||||

| Naso-anal length | 23.8 ± 0.3 | 24.6 ± 0.3 | 25.2 ± 0.2a | 24.9 ± 0.2a | 0.002 | – | 0.034 |

| Girth | 17.7 ± 0.2 | 18.1 ± 0.1 | 20.5 ± 0.3a | 19.9 ± 0.4a | <0.001 | – | – |

| Tibia length | 4.10 ± 0.03 | 4.10 ± 0.06 | 4.17 ± 0.04 | 4.12 ± 0.04 | – | – | – |

| Organ weights (g) | |||||||

| Liver weight | 14.3 ± 0.4 | 15.4 ± 0.6 | 22.3 ± 1.4a,b | 23.0 ± 1.4a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Heart weight | 1.04 ± 0.04 | 1.12 ± 0.03 | 1.38 ± 0.04a,b | 1.29 ± 0.11a,b | <0.001 | – | 0.035 |

| Fat pad weights (g) | |||||||

| Retroperitoneal | 4.03 ± 0.26 | 3.48 ± 0.23 | 14.67 ± 1.53a,b | 12.66 ± 1.15a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Gonadal | 4.23 ± 0.35 | 3.94 ± 0.27 | 14.62 ± 1.47a,b | 12.04 ± 1.31a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Total | 8.27 ± 0.55 | 7.43 ± 0.47 | 29.28 ± 2.86a,b | 24.70 ± 2.26a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Unfasted blood and plasma measures | |||||||

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 9.5 ± 0.4 | 9.8 ± 0.4 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 10.6 ± 0.4 | – | – | – |

| Plasma insulin (ng/mL) | 1.55 ± 0.15 | 1.16 ± 0.05 | 2.62 ± 0.43a,b | 1.85 ± 0.21 | 0.002 | 0.034 | – |

| Plasma leptin (ng/mL) | 3.65 ± 0.30 | 3.35 ± 0.28 | 10.65 ± 1.75a,b | 12.39 ± 1.44a,b | <0.001 | – | – |

| Plasma triglyceride (mmol/L) | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 0.75 ± 0.07 | 2.84 ± 0.28a,b | 2.14 ± 0.22a,b | 0.034 | <0.001 | – |

| Plasma high-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | – | – | 0.026 |

Data expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 4 cages for energy intake measures; n = 10–12 for other measures. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc multiple comparisons with a Tukey HSD correction.

ap < 0.05 relative to CVeh.

bp < 0.05 relative to CMino.

cp < 0.05 relative to CafVeh.

Relative fat mass (Fig. 1d) was significantly elevated in cafeteria-fed groups versus chow-fed groups (all THSD p’s < 0.001; diet: F1,43 = 184.969, p < 0.001) and cafeteria diet significantly increased girth, liver weight, and all fat depot weights examined irrespective of drug treatment (Table 1). In contrast, cafeteria diet-induced increases in plasma insulin and triglyceride concentrations were reduced by minocycline (Table 1). Absolute lean mass was significantly increased in CafVeh rats relative to all other groups (diet × drug: F1,43 = 9.141, p = 0.004; Fig. 1e), implying that minocycline treatment restricted growth in cafeteria-fed rats.

Retroperitoneal WAT inflammatory signaling and browning genes were assessed to determine whether minocycline regulates pro-inflammatory signaling in WAT (Fig. 1f), as these changes are known to contribute to diet-induced cognitive impairment48. WAT Tlr4 expression was uniquely upregulated in CafMino rats relative to all other groups (CVeh: p < 0.001, CMino: p = 0.004, CafVeh: p = 0.002 (THSD); DietXDrug: F1,42 = 5.025, p = 0.030). In contrast, expression of both Il6 and Il1B were significantly changed by cafeteria diet overall independently of minocycline treatment: Il6 was significantly increased by cafeteria diet (F1,42 = 12.118, p = 0.001) while Il1B expression was reduced by that diet (F1,42 = 7.877, p = 0.008). No significant differences were observed in Tnf, Il10, Ucp1, and Cd36 expression.

Minocycline prevented cafeteria diet-induced spatial recognition impairments and altered hippocampal pro-inflammatory gene expression

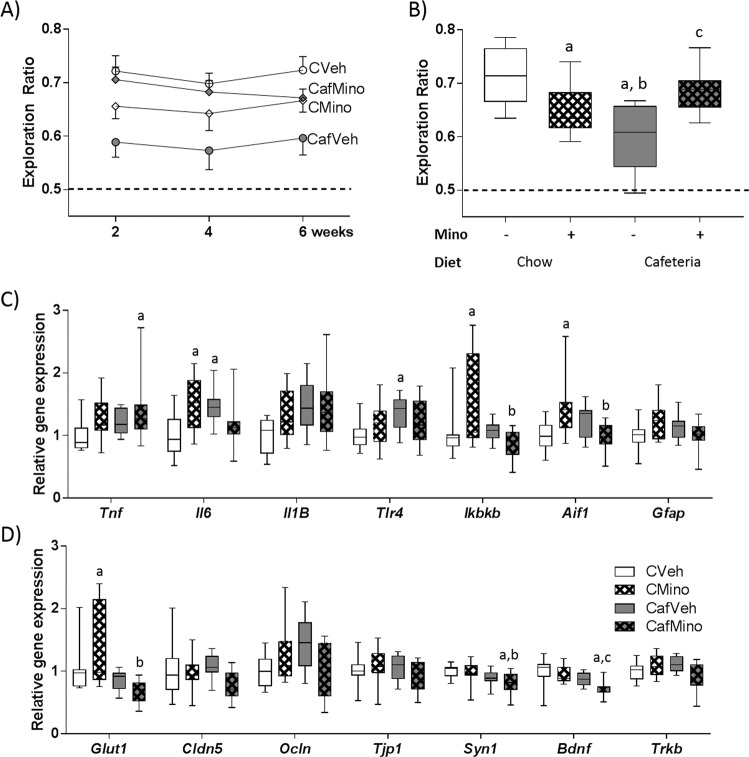

NPR and NOR were assessed at 2, 4, and 6 weeks of cafeteria diet exposure (Fig. 1a). Minocycline treatment reduced NPR performance in chow-fed rats while improving performance in cafeteria-fed rats (diet × drug: F1,80 = 17.703, p < 0.001) with no significant effect of time (F2,80 < 1; Fig. 2a). When NOR was examined, there were no significant effects of diet, minocycline treatment, or time (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Since there were no effects of time on either NPR or NOR measures, tests were averaged to reduce variability for further analyses (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1A). No significant group effects were observed for total test exploration times on either tasks (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D).

Fig. 2. Minocycline treatment improves spatial recognition memory and hippocampal pro-inflammatory gene expression in cafeteria-fed rats.

a Novel place task performance over the study and b average place task performance expressed as exploration ratios. Relative gene expression of c pro-inflammatory signals and d markers for blood brain barrier integrity, synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis in the dorsal hippocampus. Aif1 allograft inflammatory factor 1, Bdnf brain derived neurotrophic factor, Cldn5 claudin 5, Gfap glial fibrillary acidic protein, Glut1 glucose transporter 1, Ikbkb inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase subunit beta, Il6 interleukin-6, Il1B interleukin-Iβ, Ocln occludin, Syn1 synapsin 1, Tlr4 toll-like receptor 4, Tjp1 tight junction protein 1, Tnf tumor necrosis factor a, Trkb tropomyosin receptor kinase. Data expressed as box-and-whisker plots (min, IQR, max); n = 11–12; data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-adjusted post hoc testing. ap < 0.05 relative to CVeh, bp < 0.05 relative to CMino, cp < 0.05 relative to CafVeh.

Pro-inflammatory gene expression was assessed in the hippocampus (Fig. 2c): Il6, Ikbkb, Aif1 (marker of microglial proliferation49) and Gfap (marker of astrocyte proliferation and central nervous system injury50) followed a similar pattern where minocycline reduced gene expression in cafeteria-fed rats, but increased that expression in chow-fed rats (DietXDrug: F1,42 = 14.56, p < 0.001; F1,41 = 7.204, p = 0.01; F1,41 = 13.592, p = 0.001 and F1,41 = 6.395, p = 0.015, respectively). In contrast, Il1B and Tlr4 gene expression were significantly upregulated by cafeteria diet (diet: F1,42 = 6.397, p = 0.015 and F1,42 = 4.557, p = 0.039, respectively) with no minocycline-induced differences. Relative Tnf expression was significantly elevated by minocycline overall (F1,42 = 4.585, p = 0.038), and CafMino rats exhibited significantly higher Tnf expression relative to CVeh rats (p = 0.043; THSD).

Expression of markers of blood brain barrier integrity and glucose transport were assessed (Fig. 2d), as emerging evidence implicates these processes in diet-induced cognitive impairment51,52. This was not supported by our data, which showed minocycline-induced, but not cafeteria diet-induced, changes in gene expression. Ocln expression exhibited an interaction between minocycline and cafeteria diet (DietXDrug: F1,42 = 8.094, p = 0.007), while Cldn5 expression was reduced by minocycline treatment overall (F1,42 = 4.248, p = 0.046). Glut1 expression was upregulated by minocycline in chow-fed rats relative to CafVeh (p = 0.017) and CafMino (p < 0.001, THSD; DietXDrug: F1,41 = 6.135, p = 0.017). No significant group differences were observed for Tjp1 expression. Syn1 expression was significantly reduced by cafeteria diet overall (F1,42 = 9.988, p = 0.003) with no effects of minocycline, while Bdnf expression was significantly reduced by both cafeteria diet exposure (F1,40 = 12.349, p = 0.001) and minocycline treatment (F1,40 = 5.226, p = 0.028) independently. No significant differences were observed in Trkb expression.

When correlations between average NPR performance and other study variables were assessed, several relationships were observed (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, measures of increased adiposity were negatively correlated with NPR performance, while WAT Ucp1 gene expression was positively associated with NPR performance. When all vehicle-treated rats were considered, negative associations between NPR performance and measures of adiposity, and hippocampal Il6 and Il1B expression were observed.

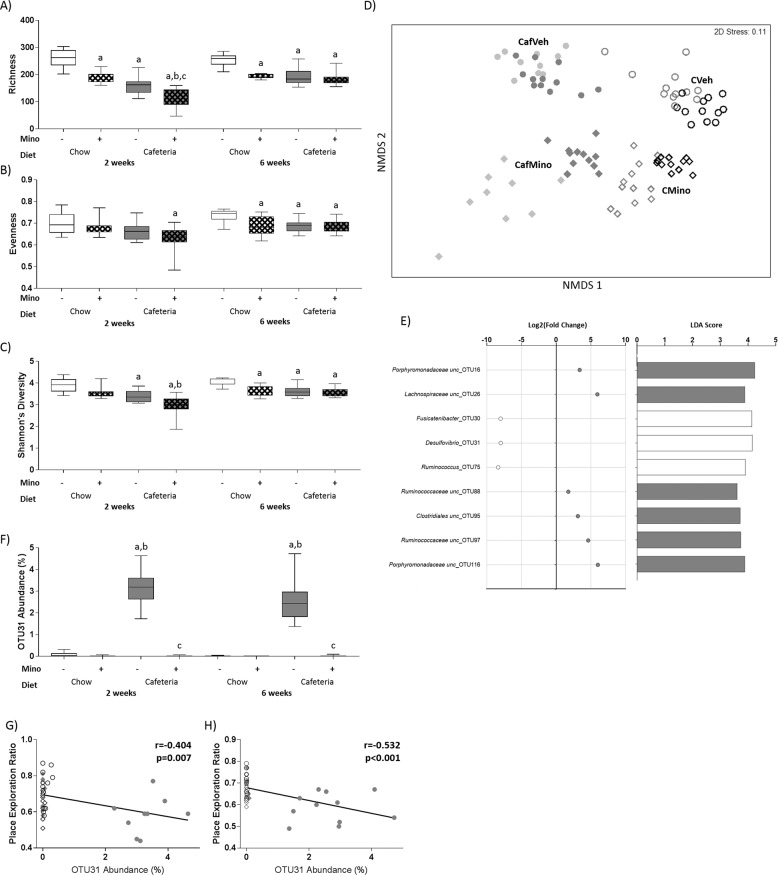

Cafeteria diet and minocycline treatment both impacted microbial species diversity and microbiome composition

Fecal microbiome analysis was conducted at 2 and 6 weeks of diet exposure. Measures of microbial α-diversity across time were assessed using a three-way ANOVA, including richness, evenness and Shannon’s Diversity (Fig. 3). Microbial species richness (Fig. 3a) exhibited significant interactions between cafeteria diet exposure and minocycline treatment (F1,39 = 8.665, p = 0.005), time and diet (F1,39 = 22.647, p < 0.001), and time and drug treatment (F1,39 = 5.261, p = 0.027) where both minocycline and cafeteria diet reduced richness, but these effects were less severe over time. Evenness (Fig. 3b) significantly increased over time (F1,39 = 11.613, p = 0.002), and was significantly reduced by cafeteria diet (F1,39 = 12.218, p = 0.001) and minocycline treatment (F1,39 = 8.918, p = 0.005) overall. Shannon’s diversity (Fig. 3c) was significantly reduced by diet (F1,39 = 40.101, p < 0.001) and minocycline treatment (F1,39 = 24.979, p < 0.001) overall, and a significant interaction between time and diet was observed (F1,39 = 6.957, p = 0.012).

Fig. 3. Impact of cafeteria diet and minocycline on fecal microbiota at 6 weeks.

a Microbial species richness, b evenness, and c Shannon’s diversity at 2 and 6 weeks. Data expressed as box-and-whisker plots (min, IQR, max); n = 11–12 for individual measures; data were analyzed by three-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-adjusted post hoc testing. d Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (Bray–Curtis, 1000 permutations) showing similarity between fecal microbiota samples at 2 (light gray) and 6 (dark gray/black) weeks. e Selected OTUs identified by both DESeq2 (adjusted p < 0.05) and LEfSe (LDA score > 2, p < 0.05) as differentially abundant with minocycline in cafeteria-fed rats that are significantly correlated with place task performance. The color of the circle/bar denotes the group the OTU is enriched in (open: vehicle; gray: minocycline). Complete list in Supplementary Table 2. f Relative abundance of OTU31 at 2 and 6 weeks. Data expressed as box-and-whisker plots (min, IQR, max); n = 11–12 for individual measures; data were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by nonparametric Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc testing. Scatterplots for place task performance and relative abundance of OTU31 at (g) 2 and (h) 6 weeks, showing overall lines of best fit; n = 46. Post hoc symbols: ap < 0.05 relative to CVeh, bp < 0.05 relative to CMino, cp < 0.05 relative to CafVeh.

Microbiome composition at the OTU level was significantly affected by cage (within diet; Pseudo-F3,59 = 1.479, p = 0.001) and time (Pseudo-F1,59 = 7.109, p = 0.001) effects as well as a significant interaction between cafeteria diet and minocycline treatment (Pseudo-F1,59 = 9.093, p = 0.001) when assessed using 4-way PERMANOVA (999 permutations). Nonmetric multidimensional scaling and pairwise comparisons confirmed that the microbiome compositions of all groups significantly differed from each other (all p’s<0.001; Fig. 3d).

When variables were assessed for their unique contribution to the variance in overall microbiome composition, several adiposity measures, as well as retroperitoneal Il6 and Tlr4 gene expression, hippocampal Il1B expression, and NPR performance were identified as significant predictors of global microbiome composition (Supplementary Table 3A). When the conditional contribution of variables of interest to overall microbiome composition was assessed while controlling for diet and minocycline exposure, in addition to several significant adiposity measures, both hippocampal Il6 expression (R2 = 0.029, p = 0.032) and NPR performance (R2 = 0.026, p = 0.007) were significant predictors of microbiome composition at the OTU level (Supplementary Table 3B, complete model predicts 47.6% of the variance in microbiome composition).

DESeq2 and LEfSe analyses were used to identify differentially enriched OTUs with diet exposure amongst the top 200 OTUs at week 6. In cafeteria-fed rats, minocycline treatment depleted several OTUs from Lactobacillus as well as Blautia genera, and enriched several OTUs from Lachnospiraceae and Porphyromonadaceae families (Supplementary Table 4). The significantly enriched and depleted OTUs that are also significantly associated with NPR performance are shown in Fig. 3e.

Desulfovibrio_OTU31 was selected for further investigation as this OTU was strongly associated with NPR performance at 2 (r = −0.404, p = 0.007, Fig. 3g) and 6 (r = −0.532, p < 0.001, Fig. 3h) weeks of cafeteria diet. Desulfovibrio_OTU31 was uniquely enriched in CafVeh rats across the study (Fig. 3f). SINA aligner analysis showed that Desulfovibrio_OTU31 shared 99.8% sequence identity with Desulfovibrio piger strain ATCC 29098.

Minocycline effects on established cafeteria diet-induced cognitive impairment (Experiment 2)

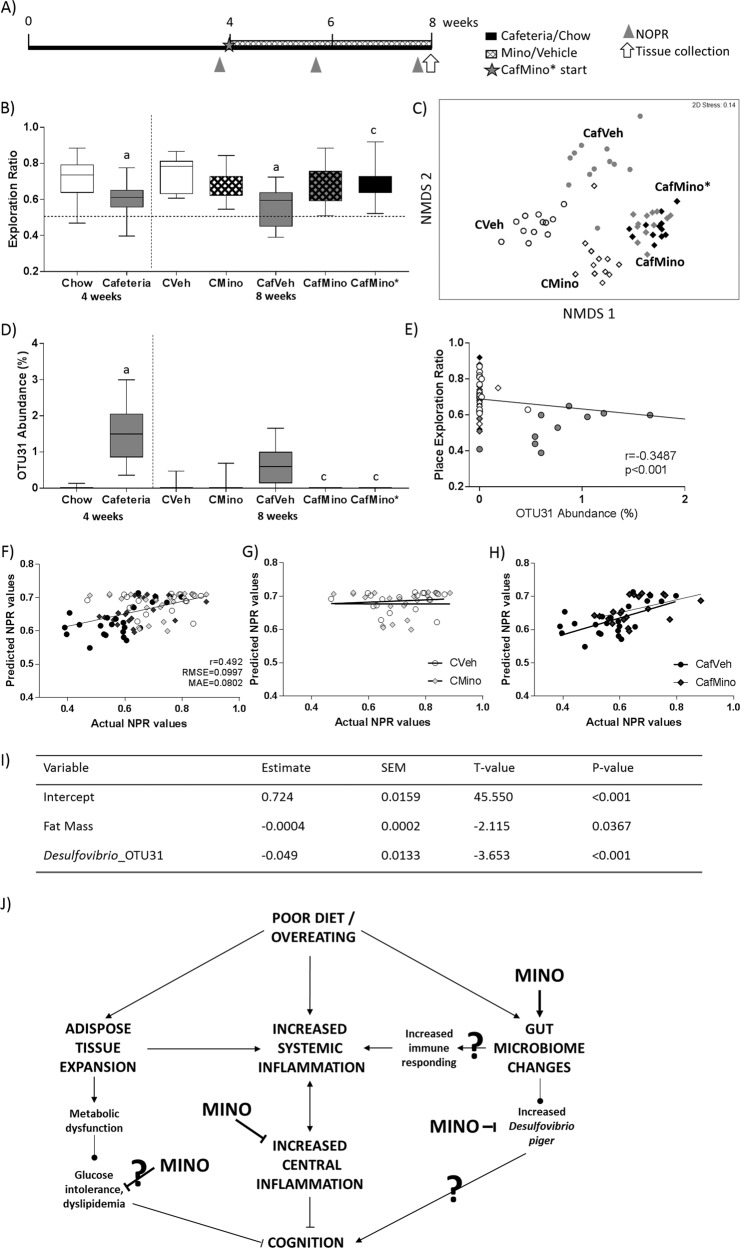

Experiment 2 examined whether minocycline could reverse already established diet-induced impairment in the NPR task (Fig. 4a). Rats were fed chow or cafeteria diet for 4 weeks, resulting in a doubling of relative fat mass compared to chow (chow: 8.22 ± 0.36%, cafeteria: 18.01 ± 1.06%; t28.39 = 7.75, p < 0.001). While maintaining their diet, rats were treated daily with either vehicle or minocycline for a further 4 weeks.

Fig. 4. Impact of minocycline treatment following 4 weeks of cafeteria diet on place task performance, fat mass and microbiota.

a Study timeline. b Average novel place task performance post-minocycline treatment expressed as exploration ratios. Data expressed as box-and-whisker plots (min, IQR, max); n = 11–12; data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-adjusted post hoc testing. ap < 0.05 relative to CVeh, bp < 0.05 relative to CMino, cp < 0.05 relative to CafVeh. c Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (Bray–Curtis, 1000 permutations) showing similarity between fecal microbiota samples at 8 weeks. d Relative abundance of OTU31 at 4 and 8 weeks. Data expressed as box-and-whisker plots (min, IQR, max); analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by nonparametric Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc testing. ap < 0.05 relative to Chow at 4 weeks, cp < 0.05 relative to CafVeh at 8 weeks. e Scatterplot of Pearson correlation between place exploration ratio and relative OTU31 abundance, showing overall line of best fit; n = 10–12. o Vehicle-treated animals (open: chow, gray: cafeteria); ◊: minocycline treated animals (open: chow, gray: cafeteria, black: CafMino*). f Prediction of place task performance using final multiple regression model overall and for g chow-fed and h cafeteria-fed rats. i Final multiple regression model based on body composition and OTUs of interest. Training dataset: 112 observations from N = 60 rats. Test dataset: n = 89 observations from N = 48 rats. r correlation coefficient, RMSE root mean square error, MAE mean absolute error. CafMino* represents a replication group for the previous study, where rats were placed on both cafeteria diet and minocycline when all other rats were allocated to vehicle or minocycline. j Poor diet and overeating lead to increased adiposity and systemic low-grade inflammation, as well as altered gut microbiota. Systemic inflammation is highly interrelated with central inflammatory tone, which was inhibited by minocycline treatment. Changes to the gut microbiome include altered composition, which may contribute to the diet-induced state of systemic inflammation. Cafeteria diet enriched Desulfovibrio piger which was depleted by minocycline and negatively associated with place task performance in both experiments. Minocycline treatment improved short-term spatial recognition memory, measured by the novel place recognition task. Pointed arrow: promotion of the downstream process; blunted arrow: inhibition of the downstream process.?: hypothesized mechanism.

Four weeks of cafeteria diet significantly impaired NPR performance relative to chow-fed controls (t55.26 = 4.435, p < 0.001; Fig. 4b) while minocycline significantly improved average NPR in cafeteria-fed (diet × drug: F1,40 = 12.799, p = 0.001) but did not affect chow-fed rats. The energy intake, metabolic and adiposity measures are shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Microbiome composition at the end of Experiment 2 was significantly altered by cafeteria diet (Pseudo-F1,44 = 7.718, p = 0.026), minocycline (Pseudo-F1,44 = 7.558, p = 0.031), and cage (within diet; Pseudo-F3,44 = 1.472, p = 0.002) when 3-way PERMANOVA and non-metric multidimensional scaling (999 permutations; Fig. 4c). FDR-corrected pairwise comparisons showed that all treatment groups were significantly different (all p’s = 0.001) except for CafMino and CafMino* groups, which did not differ significantly in microbiome composition (p = 0.222).

Associations between OTU abundances, NPR performance and adiposity measures were investigated to determine whether specific OTUs consistently predicted group differences in these variables over the experiment. Two OTUs were significantly correlated with NPR overall, Phascolarctobacterium_OTU7 and Desulfovibrio_OTU31 (the latter also seen in Experiment 1, Fig. 3g, h). Follow-up comparisons showed that Desulfovibrio_OTU31 was enriched in cafeteria-fed rats prior to minocycline exposure (Cafeteria in Fig. 4d), and in CafVeh rats following 4 weeks’ minocycline treatment (Fig. 4d). Further, its relative abundance was negatively associated with NPR performance overall (r = −0.324, p < 0.001; Fig. 4e), as observed in Experiment 1.

Fat mass and Desulfovibrio_OTU31 predict place task performance across experiments

Given the associational relationships between specific OTU abundances, adiposity and NPR, we then used multiple regression and machine learning algorithms to predict NPR performance in Experiment 2, using the results from rats treated with minocycline alongside diet exposure (Experiment 1 and CafMino*). Using NPR performance to calculate baseline error in prediction (estimate = 0.675, root mean square error (RMSE) = 0.1146, mean absolute error (MAE) = 0.0935), we found that a reduced multiple regression model (Fig. 4i; R2 = 0.185) predicted NPR performance for the training dataset (Experiment 1 and CafMino*) above chance. This model also performed best when predicting NPR performance in the test dataset (Experiment 2; R2 = 0.242; RMSE = 0.100, MAE = 0.080; Fig. 4f), although the model best predicted NPR performance in the cafeteria-fed rats (Fig. 4h; CafVeh: r = 0.596, p = 0.003; CafMino: r = 0.473, p = 0.026) with limited predictive value in chow-fed groups (Fig. 4g; CVeh: r = 0.136, p = 0.567; CMino: r = −0.002, p = 0.991). The reduced multiple regression model identified absolute fat mass and Desulfovibrio_OTU31 as significant predictors of spatial recognition memory. Figure 4j features a schematic of the mechanisms underlying diet-induced cognitive dysfunction and the observed actions of minocycline.

Discussion

In Experiment 1, minocycline protected NPR performance in cafeteria-fed rats when administered prophylactically over 6 weeks, without affecting energy intake, relative adiposity or NOR performance. Several pro-inflammatory genes were downregulated in the hippocampus by minocycline in cafeteria-fed rats and NPR performance was negatively associated with Il1b and Il6 gene expression. Both minocycline and cafeteria diet altered bacterial species diversity and microbiome composition, and the relative abundance of Desulfovibrio_OTU31 was negatively associated with NPR performance. In Experiment 2, established cafeteria diet-induced spatial recognition memory impairments were reversed with minocycline, and minocycline exerted similar effects on the microbiome in cafeteria-fed rats irrespective of whether drug treatment was started prior to (CafMino*) or following cafeteria diet exposure (CafMino).

Predictive modeling identified Desulfovibrio_OTU31 and fat mass as key factors predicting NPR performance in cafeteria-fed rats in both experiments. The inclusion of fat mass in this model is of interest as this was not changed by minocycline treatment, and fat mass measurements in CafVeh and CafMino rats overlap substantially. However, one reason for the strength of fat mass as a predictor of NPR performance may be its links with metabolic measures (plasma insulin and triglyceride concentrations) and hippocampal pro-inflammatory gene expression, which are known to be associated with diet-induced cognitive impairment and were impacted by minocycline treatment (Fig. 4j). It is noteworthy that Desulfovibrio_OTU31 had better predictive value for NPR than fat mass.

Desulfovibrio_OTU31 was consistently associated with NPR performance across independent cohorts of rats, and was putatively identified as a strain of Desulfovibrio piger, a Gram-negative, nonmotile bacillus. Desulfovibrio typically produce hydrogen sulfide and metabolize the sulfate moiety of sulfates, and their abundance positively correlates with increased adiposity and metabolic disease53. Another sulfate-reducing bacterium, Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough NCBI 8303, increased working memory errors in a radial arm maze and time spent finding the platform in a Morris water maze when administered to mice by gavage54. Contrastingly, intraperitoneal administration of sodium hydrosulfide has been shown to protect cognition in mice following surgery55 or in rats systemically injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)56, suggesting that some processes other than sulfate-reduction by Desulfovibrio species may negatively contribute to cognition.

Hippocampal gene expression of pro-inflammatory markers was elevated in vehicle-treated, cafeteria-fed (CafVeh) rats, in whom hippocampal Il6 and Il1B expression were negatively associated with NPR performance. A recent study in humans found negative associations between serum IL-6 concentration and working memory57, and several preclinical rodent studies have shown that peripheral and central cytokine administration impair hippocampal-dependent forms of cognition58,59. Of particular note, we found that several pro-inflammatory genes were also elevated in minocycline-treated, chow-fed (CMino) rats, which may in part explain their poor performance on the NPR task; a result which warrants further investigation.

The small but consistent reduction in NPR performance observed in chow-fed rats exposed to minocycline is in agreement with previous work showing that large doses of broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktails impair cognition60,61, suggesting that the antibiotic activity of minocycline may underly this observation through changes in gut microbiome composition and function. Impaired cognition with minocycline treatment alone has not been reported previously in rats. To our knowledge, no studies have investigated cognition during chronic minocycline administration alone, but an acute intraperitoneal dose of minocycline exacerbated injury-associated cognitive impairment in a model of repetitive traumatic brain injury in neonatal rats 62.

Inflammatory gene expression in retroperitoneal WAT was not affected by minocycline treatment, consistent with the failure of minocycline to prevent the induction of WAT inflammation in a rodent model of acute pancreatitis63. However, Tlr4 gene expression was significantly enriched in cafeteria-fed rats treated with minocycline only. TLR4 is an innate receptor for LPS64 and its expression is increased by both LPS and free fatty acid exposure65. The unique increase in this receptor’s expression in the WAT of cafeteria-fed rats treated with minocycline is most likely due to increases in circulating damage-associated molecular patterns following increased bacterial death, as minocycline targets both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. CafMino rats exhibited reduced bacterial species richness relative to all other groups at 2 weeks, providing evidence for a summative effect of cafeteria diet and minocycline treatment on bacterial species death.

Daily low minocycline treatment consistently reduced plasma triglyceride and insulin concentrations overall. Minocycline administration to rats with alloxan-induced diabetes reduced plasma triglyceride and blood glucose levels66 and lowering plasma triglyceride concentration in obese mice with gemfibrozil improved performance in the Morris water maze67. While these data suggest that reducing plasma triglyceride levels may improve cognition independent of other factors, it should be noted that plasma triglycerides in cafeteria-fed rats treated with minocycline remained statistically higher than both chow-fed groups. Further studies are required to determine whether such subtle reductions in plasma triglyceride concentrations as observed in the present study can improve cognition.

In terms of the translatability of these finding, minocycline is currently under investigation as adjunctive therapy for Alzheimer’s disease68, schizophrenia69 and multiple sclerosis70 with mixed results. While some studies report superiority over placebo, for instance in a metanalysis of adjunctive minocycline for schizophrenia71, others report little or no therapeutic benefit as well as issues of tolerability of a higher 400 mg dose68. Future work determining whether minocycline provides the same cognitive benefits to people with obesity as observed in these rodent studies, as well as investigations into long-term cognitive rescue, are warranted.

In summary, we show that oral minocycline treatment both prevents and improves spatial recognition memory impairments in cafeteria-fed rats while reducing hippocampal pro-inflammatory gene expression and disrupting fecal microbiome composition. Predictive modeling identified Desulfovibrio_OTU31 and fat mass as key factors for predicting short-term recognition memory in the context of cafeteria diet and minocycline exposure in rats.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Robyn Lawler at the Biological Resources Centre, UNSW Sydney, for assistance with animal husbandry, and Dr. Michael Kendig, Francis Lee, and Josephine Yu for assistance with dissection. This research includes computations using the computational cluster Katana supported by Research Technology Services at UNSW Sydney. The work was supported by an NHMRC project grant (#1126929) to M.J.M. and R.F.W. S.J.L. was supported by a Research Training Program scholarship.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: S.J.L., R.F.W., and M.J.M. Performed the experiments, behavioral data, brain data, and predictive modeling: S.J.L. Microbiome the data: S.J.L. and N.O.K. Interpretation of the data and writing: S.J.L., N.O.K., R.F.W., and M.J.M. All authors approved the paper.

Data availability

The sequence data are available in the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB34488. The study is currently set on private and will be released upon acceptance. All other data will be made available upon from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-0774-1).

References

- 1.O’Brien PD, Hinder LM, Callaghan BC, Feldman EL. Neurological consequences of obesity. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:465–477. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attuquayefio T, Stevenson RJ. A systematic review of longer-term dietary interventions on human cognitive function: emerging patterns and future directions. Appetite. 2015;95:554–570. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzpatrick S, Gilbert S, Serpell L. Systematic review: are overweight and obese individuals impaired on behavioural tasks of executive functioning? Neuropsychol. Rev. 2013;23:138–156. doi: 10.1007/s11065-013-9224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen J. C. D., Killcross A. S. & Jenkins T. A. Obesity and cognitive decline: role of inflammation and vascular changes. Front. Neurosci.10.3389/fnins.2014.00375 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Dye L, Boyle NB, Champ C, Lawton C. The relationship between obesity and cognitive health and decline. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017;76:443–454. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117002014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iyer A, Fairlie DP, Prins JB, Hammock BD, Brown L. Inflammatory lipid mediators in adipocyte function and obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2010;6:71. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YPS. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:738. doi: 10.1038/nri3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillemot-Legris O, Muccioli GG. Obesity-induced neuroinflammation: beyond the hypothalamus. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:237–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutheil S, Ota KT, Wohleb ES, Rasmussen K, Duman RS. High-fat diet induced anxiety and anhedonia: impact on brain homeostasis and inflammation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;41:1874. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang E.-B. et al. Neuroprotective effects of endurance exercise against high-fat diet-induced hippocampal neuroinflammation. J. Neuroendocrinol.10.1111/jne.12385 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Beilharz JE, Kaakoush NO, Maniam J, Morris MJ. The effect of short-term exposure to energy-matched diets enriched in fat or sugar on memory, gut microbiota and markers of brain inflammation and plasticity. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016;57:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beilharz JE, Maniam J, Morris MJ. Short-term exposure to a diet high in fat and sugar, or liquid sugar, selectively impairs hippocampal-dependent memory, with differential impacts on inflammation. Behav. Brain Res. 2016;306:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beilharz JE, Maniam J, Morris MJ. Short exposure to a diet rich in both fat and sugar or sugar alone impairs place, but not object recognition memory in rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014;37:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J, et al. Ursolic acid improves high fat diet-induced cognitive impairments by blocking endoplasmic reticulum stress and IκB kinase β/nuclear factor-κB-mediated inflammatory pathways in mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011;25:1658–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pistell PJ, et al. Cognitive impairment following high fat diet consumption is associated with brain inflammation. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010;219:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeon BT, et al. Resveratrol attenuates obesity-associated peripheral and central inflammation and improves memory deficit in mice fed a high-fat diet. Diabetes. 2012;61:1444–1454. doi: 10.2337/db11-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molteni R, Barnard RJ, Ying Z, Roberts CK, Gomez-Pinilla F. A high-fat, refined sugar diet reduces hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neuronal plasticity, and learning. Neuroscience. 2002;112:803–814. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molteni R, et al. Exercise reverses the harmful effects of consumption of a high-fat diet on synaptic and behavioral plasticity associated to the action of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2004;123:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calvo-Ochoa E, Hernandez-Ortega K, Ferrera P, Morimoto S, Arias C. Short-term high-fat-and-fructose feeding produces insulin signaling alterations accompanied by neurite and synaptic reduction and astroglial activation in the rat hippocampus. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2014;34:1001–1008. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrido-Mesa N, Zarzuelo A, Galvez J. Minocycline: far beyond an antibiotic. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013;169:337–352. doi: 10.1111/bph.12139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong ML, et al. Inflammasome signaling affects anxiety- and depressive-like behavior and gut microbiome composition. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:797–805. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, et al. Minocycline ameliorates cognitive impairment induced by whole-brain irradiation: an animal study. Radiat. Oncol. 2014;9:281. doi: 10.1186/s13014-014-0281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohman RA, Bhattacharya TK, Kilby C, Bucko P, Rhodes JS. Effects of minocycline on spatial learning, hippocampal neurogenesis and microglia in aged and adult mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2013;242:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou Y, et al. Minocycline protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:905–916. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukherjee A, Mehta BK, Sen KK, Banerjee S. Metabolic syndrome-associated cognitive decline in mice: Role of minocycline. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2018;50:61–68. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_110_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cope EC, et al. Microglia play an active role in obesity-associated cognitive decline. J. Neurosci. 2018;38:8889–8904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0789-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaughn AC, et al. Energy-dense diet triggers changes in gut microbiota, reorganization of gut‑brain vagal communication and increases body fat accumulation. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2017;77:18–30. doi: 10.21307/ane-2017-033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce-Keller AJ, et al. Obese-type gut microbiota induce neurobehavioral changes in the absence of obesity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;77:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beilharz JE, Kaakoush NO, Maniam J, Morris MJ. Cafeteria diet and probiotic therapy: cross talk among memory, neuroplasticity, serotonin receptors and gut microbiota in the rat. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018;23:351–361. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leigh SJ, Kendig MD, Morris MJ. Palatable western-style cafeteria diet as a reliable method for modeling diet-induced obesity in rodents. JoVE. 2019;153:e60262. doi: 10.3791/60262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atcha Z, et al. Alternative method of oral dosing for rats. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2010;49:335–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tillmann S, Wegener G. Syringe-feeding as a novel delivery method for accurate individual dosing of probiotics in rats. Benef. Microbes. 2018;9:311–315. doi: 10.3920/BM2017.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barker GR, Bird F, Alexander V, Warburton EC. Recognition memory for objects, place, and temporal order: a disconnection analysis of the role of the medial prefrontal cortex and perirhinal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2948–2957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barker GR, Warburton EC. When is the hippocampus involved in recognition memory? J. Neurosci. 2011;31:10721–10731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6413-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Orntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5245–5250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caporaso JG, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2011;108:4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schloss PD, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zakrzewski M, et al. Calypso: a user-friendly web-server for mining and visualizing microbiome-environment interactions. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:782–783. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R Package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993;18:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pruesse E, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. SINA: accurate high-throughput multiple sequence alignment of ribosomal RNA genes. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1823–1829. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; San Francisco, California, USA. 2939785. 785–794 (ACM, 2016).

- 48.Erion JR, et al. Obesity elicits interleukin 1-mediated deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:2618–2631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4200-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imai Y, Ibata I, Ito D, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatibility complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;224:855–862. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brenner M. Structure and transcriptional regulation of the GFAP gene. Brain Pathol. 1994;4:245–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1994.tb00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hargrave SL, Davidson TL, Zheng W, Kinzig KP. Western diets induce blood-brain barrier leakage and alter spatial strategies in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 2016;130:123–135. doi: 10.1037/bne0000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanoski SE, Zhang Y, Zheng W, Davidson TL. The effects of a high-energy diet on hippocampal function and blood-brain barrier integrity in the rat. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010;21:207–219. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petersen C, et al. T cell–mediated regulation of the microbiota protects against obesity. Science. 2019;365:eaat9351. doi: 10.1126/science.aat9351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ritz NL, et al. Sulfate-reducing bacteria impairs working memory in mice. Physiol. Behav. 2016;157:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chu Q-J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates surgical trauma-induced inflammatory response and cognitive deficits in mice. J. Surg. Res. 2013;183:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gong Q-H, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive impairment: a pro-inflammatory pathway in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2010;96:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trevizol AP, et al. Peripheral interleukin-6 levels and working memory in non-obese adults: a post-hoc analysis from the CALERIE study. Nutrition. 2019;58:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gibertini M, Newton C, Friedman H, Klein TW. Spatial learning impairment in mice infected with Legionella pneumophila or administered exogenous interleukin-1-beta. Brain Behav. Immun. 1995;9:113–128. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larson SJ, Dunn AJ. Behavioral effects of cytokines. Brain Behav. Immun. 2001;15:371–387. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frohlich EE, et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016;56:140–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohle L, et al. Ly6C(hi) monocytes provide a link between antibiotic-induced changes in gut microbiota and adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1945–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanlon LA, Huh JW, Raghupathi R. Minocycline transiently reduces microglia/macrophage activation but exacerbates cognitive deficits following repetitive traumatic brain injury in the neonatal rat. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2016;75:214–226. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlv021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bonjoch L, Gea-Sorlí S, Jordan J, Closa D. Minocycline inhibits peritoneal macrophages but activates alveolar macrophages in acute pancreatitis. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2015;71:839–846. doi: 10.1007/s13105-015-0448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Means TK, Golenbock DT, Fenton MJ. The biology of Toll-like receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:219–232. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shi H, et al. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2006;116:3015–3025. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Viana GSB, et al. Minocycline decreases blood glucose and triglyceride levels and reverses histological and immunohisto-chemical alterations in pancreas, liver and kidney of alloxan-induced diabetic rats. J. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;5:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farr SA, et al. Obesity and hypertriglyceridemia produce cognitive impairment. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2628–2636. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Howard R, et al. Minocycline at 2 different dosages vs placebo for patients with mild Alzheimer disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:164–174. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deakin B, et al. The benefits of minocycline on negative symptoms of schizophrenia in patients with recent-onset psychosis (BeneMin): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:885–894. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30345-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Metz LM, et al. Trial of minocycline in a clinically isolated syndrome of multiple sclerosis. New England J. Med. 2017;376:2122–2133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiang YQ, et al. Adjunctive minocycline for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequence data are available in the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB34488. The study is currently set on private and will be released upon acceptance. All other data will be made available upon from the corresponding author on reasonable request.