Abstract

Behavior analysts are increasingly called to serve culturally and linguistically diverse populations. The culture of a population can provide context in which to identify behaviors likely to be reinforced by the client’s social environment, stimuli established as reinforcers for client behavior, and behavioral repertoires shaped by the client’s social environment. One of the largest and fastest growing minority groups in the United States is the Latinx population. This article offers preliminary evidence of incorporating cultural adaptations into the context of behavioral consultation for the Latinx population. Cultural adaptation of behavioral consultation can lead to improved outcomes for educators. In this study, 5 educators received behavioral consultation consisting of behavioral skills training to implement culturally responsive class-wide behavior management procedures. All 5 educators improved their treatment fidelity of the culturally responsive behavior management practices. Implications for practitioners and future research are discussed.

Keywords: Cultural, language, Behavior consultation, Behavior analysis

Behavior analysts consulting within school systems are often tasked with designing treatment strategies for student academic, social, and behavioral concerns (Putnam & Kincaid, 2015). Treatment success depends on the extent to which the behavior analyst can ensure accurate plan implementation by the natural change agent (e.g., the educator within the school). To prepare educators in intervention procedures, behavior analysts should rely on behavioral skills training (BST) procedures consisting of verbal and written instruction, modeling, role-play, and performance feedback (Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012). Behavior analysts’ use of BST has proven effective to improve educator implementation (termed “treatment fidelity”) of behavioral assessments and interventions (Gianoumis, Seiverling, & Sturmey, 2012; Rispoli, Neely, Healy, & Gregori, 2016).

Within the context of behavioral consultation, behavior analysts are increasingly called to serve culturally and linguistically diverse populations. The culture of a population can provide context in which to identify client values (or behaviors likely to be reinforced by the client’s community), preferences (stimuli established as reinforcers through a learned history), and character (behavioral repertoires shaped by the client’s social environment; Skinner, 1953). Although the basic science of behavior may not change based on culture, the value of identifying a client’s culture is in classifying the social environment variables likely to reinforce learned behaviors and those likely to punish learned behaviors (Skinner, 1953). Identification of these variables before assessment and intervention can improve the social validity of the treatment by allowing the behavior analyst to modify the intervention and responses to ensure a match with the client’s social environment. In addition, identification of the client’s culture may help the behavior analyst predict how that individual might respond in specific situations based on observed patterns of behavior for that individual’s particular culture (e.g., distinguishable stimulus and response classes unique to the individual; Fong, Catagnus, Brodhead, Quigley, & Field, 2016). However, behavior analysts should be careful not to generalize their predictions based on distinguishable stimuli of an individual, as individuals may operate within multiple cultures (which may not all be known to the behavior analyst).

By recognizing culture, behavior analysts can address disparities in access to services for culturally and linguistically diverse populations. For example, within the South Texas home of the authors, there is a need to consider the unique needs of the Latino/Latina (henceforth referred to using the gender-neutral term “Latinx”) community. Latinx students are members of the largest and fastest growing minority group in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). The Latinx population reports a lack of cultural sensitivity as a major barrier to participation in evidence-based treatments (Morales, Lutzker, Shanley, & Guastaferro, 2015; Wolfe & Durán, 2013). Culturally sensitive interventions can improve recruitment, retention, participant satisfaction, treatment adherence, and treatment effects (Parra Cardona et al., 2012). The Latinx population is, unfortunately, underrepresented in intervention research, and innovative treatments continue to be primarily developed and validated for the White, monolingual, non-Hispanic population (DuBay, Watson, & Zhang, 2018). Therefore, there is a need to adapt behavioral consultation practices to meet the unique needs of the Latinx population.

Cultural Adaptation of Behavioral Consultation

Behavior analysts may identify salient cultural variables using a cultural sensitivity (CS) framework. When creating a culturally tailored program, the CS framework allows for modifications based on surface and deep structural adaptations (Resnicow, Baranowski, Ahluwalia, & Braithwaite, 1999). Surface adaptations are those that may be applicable to multiple cultures, including matched language, matched materials, and matched cultural interventionists (or cultural brokers). For example, research has shown that matching the language of intervention to individual clients can lead to improved outcomes (Durán, Roseth, & Hoffman, 2010; Restrepo et al., 2010; Restrepo, Morgan, & Thompson, 2013). Deep structural adaptations are those unique to a culture. For example, major identified cultural variables for the Latinx population include respecto and familismo (Barker, Cook, & Borrego, 2010; Calzada, 2010). The variable of respecto emphasizes the role of respect and empathy within interpersonal relationships. The second value of familismo focuses on family attachments and commitments that extend beyond the nuclear family. Ideally, culturally adapted programs would include both surface and deep structural adaptations.

When considering adaptations within the behavioral consultation framework, one might first start with identification of surface adaptations (e.g., matched language and matched materials). For example, a behavior analyst might suggest delivery of instruction in students’ primary language or bilingual instruction (Fallon, O’Keeffe, & Sugai, 2012; Sugai, O’Keeffe, & Fallon, 2012). They might also suggest developing curricula, lesson plans, and activities that embed students’ native language and messages that are representative of relevant cultural groups (Canfield-Davis, Tenuto, Jain, & McMurtry, 2011; Sugai et al., 2012). Furthermore, they might suggest materials, books, posters, and pictures be used in the classroom that represent diverse children and families (Allen & Steed, 2016). Likewise, behavior analysts might recommend that assignments consistently include diverse characters, languages, heritages, examples, topics, and themes (Cramer & Bennett, 2015).

Incorporation of surface adaptations may improve the effectiveness and social validity of the intervention. For example, McKenney, Mann, Brown, and Jewell (2017) evaluated whether culturally responsive classroom-level management (e.g., materials with diverse characters, spelling words in students’ native language) provided additive benefit to typical classroom management for disruptive behaviors. The authors used a multiple-baseline design to evaluate the effect of typical classroom management consultation on students and the effect of consultation focused on classroom management plus culturally responsive practices. The typical classroom management consultation resulted in decreased disruptive behavior for all three classrooms. However, the addition of the culturally responsive intervention resulted in additional reduction in disruptive behavior for one of the three classrooms and increased educator practices (including delivery of praise and opportunities to respond). The educators also reported higher social validity scores following culturally responsive consultation compared to consultation without the cultural element (McKenney et al., 2017).

The purpose of this study was to provide preliminary evidence for implementing surface adaptations to class-wide behavior supports within the context of behavioral consultation. We aimed to provide a discrete example for aiding practicing professionals in the use of BST for improved the fidelity of implementation of class-wide culturally responsive classroom management practices in two schools with high Latinx populations.

Method

Participants and Setting

As part of a laboratory school project implemented in collaboration with a university in the southwest region of the United States, researchers invited educators involved in this project to attend small group professional development sessions addressing a variety of topics, including culturally responsive classroom management and behavior support. The researchers then invited all educators who attended this small group training to engage in research regarding culturally responsive classroom management practices and to receive follow-up consultation support from university faculty as a part of this study. Six educators from the two university-supported laboratory schools volunteered to participate in this study. Five of the educators completed the entire study. The sixth educator (Educator F) did not complete the study due to personal medical complications. To be included in the study, the educators had to be employed full time at one of the university-supported laboratory schools and consent to participate in the study. Two educators participated from Campus 1 and four educators from Campus 2. See Table 1 for participant information.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information

| Teacher | Grade Level | Ethnicity | Highest Degree Earned | Number Years Teaching |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5th, Bilingual | Mexican American | Bachelors, BE | 1 |

| B | 2nd | Canadian | Bachelors, ILT | 10 |

| C | 4th, Bilingual | Mexican American | Masters, BE | 10 |

| D | Kindergarten | Mexican American | Masters, ILT | 1 |

| E | 2nd | Mexican American | Bachelors, ILT | 5 |

| F | Kindergarten | Caucasian | Bachelors, ILT | 5 |

Note. BE = Bilingual Education; ILT = Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching.

Both the participating schools were located within an urban inner-city public-school district in the southwest region of the United States. The total district enrollment was approximately 50,000 students, of which 91% identified as Hispanic, 6% as African American, and 2% as Caucasian. Ninety-one percent of students qualified as economically disadvantaged. The district had been implementing a class-wide behavior management model since the 2010–2011 school year. However, both schools requested support in adapting the model to match the diverse needs of their students, reporting Spanish and English as dominant languages for the students they served. Researchers conducted all session observations (baseline and coaching) in participating educators’ respective classrooms.

Campus 1 had 354 students at the time of this study. Of the students, 93% were Hispanic/Latinx, 3% were Caucasian, 3% were of other ethnicities, and 98% of the student population categorized as economically disadvantaged. Two educators from this campus elected to participate in this study (Educators A and B) and composed Dyad 1. Campus 2 had 665 students at the time of this study. Of the students, 95% were Hispanic/Latinx, 4% were African American, and 1% were Asian and Caucasian. Ninety-four percent of students were considered economically disadvantaged. Four educators from this campus elected to participate, composing Dyad 2 (Educators C and D) and Dyad 3 (Educators E and F).

Dependent Variable and Data Collection

The dependent variable in this study was the fidelity in which educators implemented the culturally responsive class-wide behavior supports (CR-CBS). We evaluated the presence of CR-CBS practices within the classroom using a researcher-developed rubric (Appendix Table 2; see description of CR-CBS rubric in the Measure section). For each 20-min observation period, researchers collected educator fidelity in implementing the CR-CBS as the percentage of practices observed during the observation period. For the purpose of this study, acceptable treatment fidelity was set at 70% of rubric items, with coaching sessions focused on improving practices to reach this level of acceptability.

Table 2.

CR-CBS scoring rubric

| Classroom Management Practices | Yes | No | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom Structure | |||

| Is there a daily schedule posted such that all students can see and understand what is expected, when it will occur, and how long it will last? | |||

| Is this daily schedule available in Spanish? | |||

| Are there pictures or images to accompany the daily schedule? | |||

| Is cultural diversity valued in the classroom as evidenced by materials and signage in the classroom (i.e., signs reflect student diversity, posted projects reflect diversity, classroom decorations reflect diversity), with at least three ethnicities represented; both genders represented, special populations represented? | |||

| Classroom Rules/Expectations | |||

| Are there three to five positively stated classroom rules displayed in a manner that all students can see? | |||

| Are the classroom rules translated into Spanish? | |||

| Are the classroom rules available in pictures or images? | |||

| Can three out of three students state the classroom rules in English? | |||

| Can three out of three students state the classroom rules in Spanish? | |||

| Reinforcement | |||

| Does the teacher provide a 4:1 ratio of positive acknowledgments for every negative or error correction (as measured by the attached data sheet)? | |||

| Does the teacher offer positive acknowledgments in English and Spanish (as measured by the attached frequency data sheet)? | |||

| Do students receive descriptive praise for correct and appropriate behavior (as measured by the attached frequency data sheet)? | |||

| Is descriptive praise also offered in Spanish (as measured by attached frequency data sheet)? | |||

| Is student diversity evident in the diversity of reinforcement options (i.e., are reinforcements student selected or teacher selected)? | |||

| Instructional Practices | |||

| Does the teacher directly teach classroom rules and expectations during the observation period? | |||

| Does the teacher directly teach classroom procedures and routines during the observation period? | |||

| Is there use of quiet cues, or noise control procedures during the observation period (Focus Pocus; Give me 5; 1,2,3 Eyes on Me; nonverbal hand motions)? | |||

| Does the teacher utilize warm-up techniques during the observation period (i.e., a word problem on the white board, a vocabulary word on the white board, a daily journaling assignment, stretching, music, a countdown to the next assignment)? | |||

| Are students offered various types of opportunities to respond (e.g., cooperative learning or productive group work, agree and disagree, individual white boards, thumbs-up and thumbs-down) throughout the observation period? | |||

| Are students offered multiple opportunities to respond throughout the observation period? What is the frequency of student responses during the observation period (as measured by the attached data sheet)? | |||

| Are students allowed to respond to questions in Spanish? If observed, please list the frequency of responses in Spanish on the attached data sheet. | |||

| Does the teacher use multiple (at least two different) teaching or instructional modalities or technologies during the observation period (i.e., PowerPoint, smart board, projector, role-play, modeling, manipulatives, Q&A)? | |||

| Are the literacy materials representative of authors from cultural and linguistically diverse backgrounds? | |||

| Does the content or topic of the literacy materials selected reflect cultural and linguistic diversity? | |||

| Is student diversity reflected in literacy materials (characters represented and discussed in materials)? | |||

| Does the teacher value diversity in the classroom as measured by the teacher using examples that reflect diversity during the observation period (e.g., diverse points of view, pros/cons, both sides of an issue, obtaining multiple perspectives from students) or providing positive feedback for any response attempt? | |||

| Does the teacher incorporate at least one activity that explores diverse cultural backgrounds during the observation period? | |||

Measure

The researcher-developed rubric (CR-CBS rubric) used in this study (Appendix Table 2) consisted of 27 evidence-based behavior management practices scored using a dichotomous scoring procedure (i.e., a score of 1 indicated implementation of the practice and 0 indicted absence of the practice). If raters scored a 1, they indicated the frequency or description of the item content. The research team designed the rubric to evaluate the implementation of evidence-based class-wide behavior management practices (Doll, Zucker, & Brehm, 2004; Pianta, 1999; Simonsen, Fairbanks, Briesch, Myers, & Sugai, 2008; Sutherland, Alder, & Gunter, 2003). The researchers also adapted the practices to include surface modifications (e.g., providing feedback in English and Spanish). Of the 27 practices, 9 focused on classroom structure (e.g., classroom expectations posted in multiple languages; Doll et al., 2004), 15 focused on educator behavior (e.g., the educator providing descriptive feedback in both English and Spanish, the use of quiet cues, opportunities to respond; Pianta, 1999; Simonsen et al., 2008; Sutherland et al., 2003), and 3 focused on the diversity of learning materials (e.g., diversity in literacy materials, room signage, and language; Fallon et al., 2012; Vincent, Randall, Cartledge, Tobin, & Swain-Bradway, 2011). All selected practices were adapted based on surface adaptations recommended within the extant literature on best practice for classroom management (Bradshaw, Waasdorp, & Leaf, 2012; Cramer & Bennett, 2015; Fallon et al., 2012; Horner, Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, & Todd, 2001; Solomon, Klein, Hintze, Cressey, & Peller, 2012; Vincent & Tobin, 2011).

Interobserver Agreement

The research team developed the CR-CBS tool, and all members trained in its use via practice and feedback during weekly research meetings. Trained master’s-level students served as the secondary data collectors for the purpose of interrater agreement. The research team collected interrater agreement data for a minimum of 20% of sessions for each educator participant for each phase of the study (e.g., a minimum of 20% for pretraining and 20% for posttraining). The lead author calculated interrater agreement using percentage agreement by dividing the total number of items for which there was agreement by the total number of items and multiplying by 100. Overall, interrater agreement averaged 95% (range 88%–100%) across educators. Resulting interrater agreement was 93% for Educator A (93% at each session), 95% for Educator B (range 90%–100%), 95% for Educator C (range 88%–100%), 92% for Educator D (range 88%–100%), 98% for Educator E (range 93%–100%), and 97% for Educator F (range 93%–100%).

Experimental Design

The research team selected a concurrent multiple-probe design across dyads to evaluate the effectiveness of a BST-based training package on educator implementation of the CR-CBS intervention (Kazdin, 2011). A multiple-probe design uses intermittent data collection sessions, or probes, during baseline. Using this design allowed researchers to minimize the disruption to participating educators’ normal classroom routines prior to implementation of intervention coaching. The researchers randomly assigned the dyads in Campus 2 within the multiple-probe design and predetermined the dates to initiate intervention for dyads prior to the start of the study.

Procedures

Baseline

During baseline, researchers instructed the educators to conduct instruction as usual. Researchers did not provide feedback or direction. The researchers conducted the behavioral observations using the researcher-developed CR-CBS rubric and collected data on frequency of praise, error correction, descriptive praise, individual opportunities to respond, and group opportunities to respond in either English or Spanish to help inform the ratings on the rubric (Appendix Table 2). Baseline continued until the predetermined intervention date.

Initial Training

Following the completion of the baseline phase, dyads attended a small group training held in a conference room on their campus. The training consisted of a didactic PowerPoint presentation with the opportunity for questions at the end of the presentation (e.g., verbal and written instruction). The 1.5-hr presentation consisted of an overview of evidence-based classroom behavior management practices, discussion of the influence of culture on student behavior, individual student cultural and linguistic differences, and examples of culturally responsive instructional and classroom management practices (e.g., opportunities to respond in multiple languages, descriptive praise, culturally responsive signage, cultural adaptations to instructional practices). The training and examples provided were individualized for the target campus demographics, specifically the Latinx population.

In Situ Feedback

After the small group training, researchers (termed “coach”) observed the educators in their classrooms using the CR-CBS rubric. The coach then conducted a coaching session immediately following the observation during the educator’s conference period. During the coaching sessions, the educator and coach reviewed the CR-CBS rubric together. The coach provided descriptive praise for items where they observed the expected behavior, neutral performance feedback with modeling and role-play for when expected behavior was not observed, and opportunities for the educator to ask questions. The coach ended each consultation session by providing an overall positive statement regarding the educator’s implementation of the CR-CBS practices and scheduled the next observation and coaching session. This process continued for at least three sessions to meet single-case design standards with reservations (Kratochwill et al., 2010).

Procedural Fidelity

We collected coaching fidelity data for adherence to the BST-based coaching feedback procedures according to a coaching fidelity checklist (Appendix Table 3). Trained graduate research assistants collected the coaching fidelity data for a minimum of 14% of feedback sessions. Fidelity was calculated by dividing the number of observed coaching behaviors, dividing by the total number of expected coaching behaviors, and multiplying by 100 to obtain a percentage. Resulting fidelity was 96% (range 89%–100%).

Table 3.

Coaching fidelity checklist

| Expected Behavior | “+” = behavior occurred “–” = behavior did not occur |

|---|---|

| 1. The researcher asks the teacher if the teacher is ready for feedback. | |

| 2. The researcher reviews the fidelity sheet with the teacher. | |

| 3. Upon instances where the expected behavior was observed, the researcher provides descriptive praise. | |

| 4. Upon instances where the expected behavior was not observed, the researcher states in a neutral voice that the behavior was not observed. | |

| 5. Upon instances where the expected behavior was not observed, the researcher provides descriptive suggestions for the next implementation session. | |

| 6. The researcher asks if the teacher has any questions. | |

|

9. The researcher answers all questions the teacher Asks. |

|

| 10. The researcher reviews each element that was not met in the fidelity sheet. | |

| 11. The researcher concludes the session with a positive statement regarding teacher implementation and, if applicable, schedules the next session. | |

| Percentage Correct |

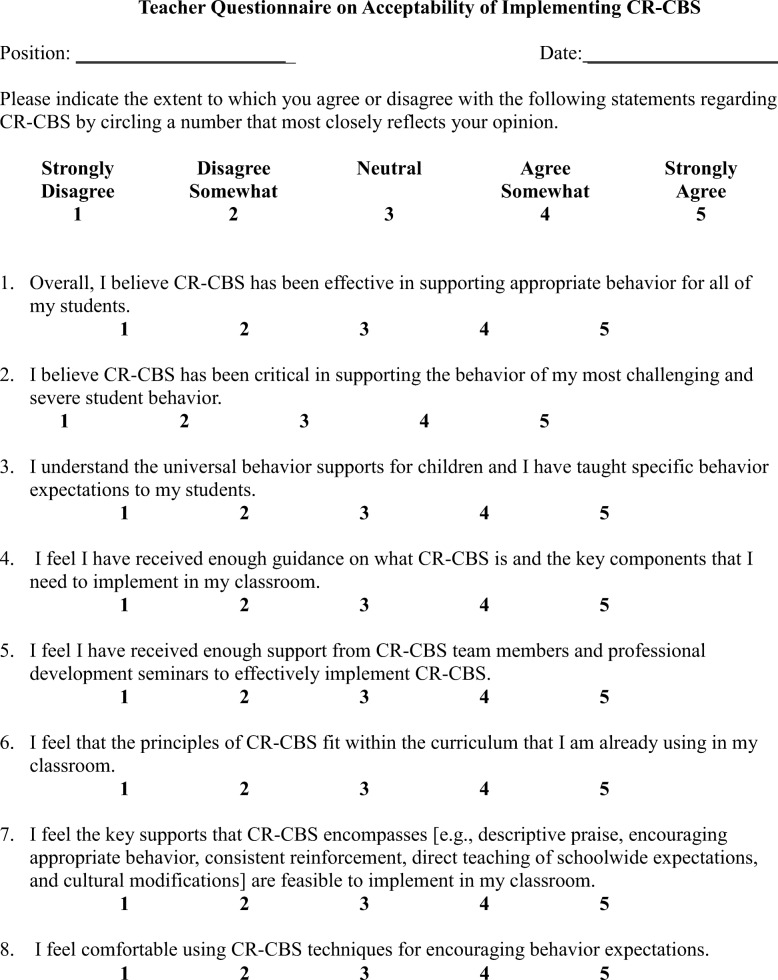

Social Validity

We collected social validity data via a questionnaire (Appendix C) aimed to evaluate the acceptability of CR-CBS practices, the acceptability of coaching support from coaches, the ease of integration of CR-CBS practices into the classroom, and the perceived effect on student behavior. This questionnaire consisted of 10 positively phrased questions requiring participants to respond on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 5 indicating strongly agree. Although only two of the five educators responded to the questionnaire, each educator reported an average score of 4.1, indicating high acceptability of CR-CBS.

Results

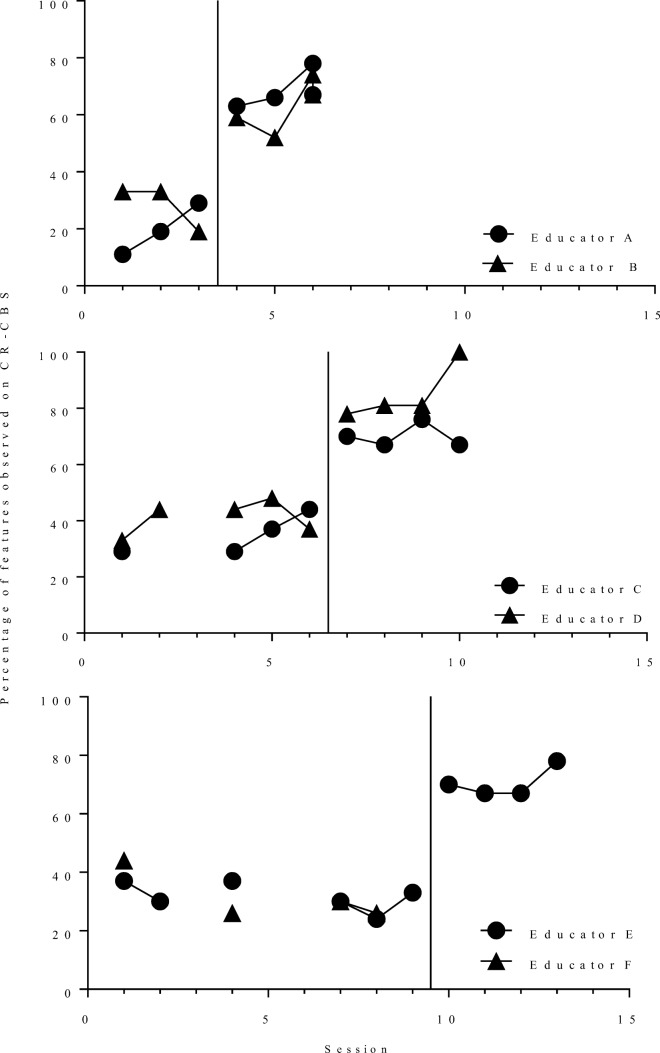

Educators’ fidelity of implementing the CR-CBS classroom management practices is displayed in Figure 1. During the baseline condition, educators’ implementation of the target intervention was low and stable. Educator A averaged 20% (range 11%–29%) of features observed, Educator B averaged 28% (range 19%–33%) of features observed, Educator C averaged 41% (range 33%–48%), Educator D averaged 35% (range 29%–44%), Educator E averaged 32% (range 24%–37%), and Educator F averaged 30% (range 24%–44%). All the educators improved their implementation of the target intervention during the training phase. Educator A demonstrated an immediate increase to 60% of the expected features and improved to an average of 69% of features observed (range 63%–78%) during the training phase. Educator B also demonstrated an immediate increase with an average of 63% of the features observed (range 52%–74%). Educator C demonstrated an immediate increase but then maintained at an average of 70% of features observed (range 67%–76%). Educator D demonstrated a large immediate increase, eventually reaching 100% of the features observed (average 85%; range 78%–100%). Educator E demonstrated an immediate jump to 70% of the features observed with an average 69% of the features observed (range 63%–78%) throughout the remainder of the study.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of features observed on CR-CBS for each educator dyad

Breaking out the subsection of the rubric that evaluated student knowledge of classroom rules, all the classrooms noted large improvements. During baseline, students could vocally state the classroom rules in English for less than one out of six requests (15% of requests) and during zero of the requests for the Spanish language. During intervention, students could vocally state the classroom rules in English in almost five out of six requests (82% of requests) and in Spanish in almost four out of six requests (63% of requests).

The subsections evaluating the educators’ frequency of praise and error correction statements demonstrated improvements across the classrooms. During baseline, educators delivered praise in English for an average of 5.48 statements per session (range 0–17 statements) and 0.09 Spanish praise statements per session (range 0–1 statements). This increased to an average of 6.74 English praise statements per session (range 0–19 statements per session) and 0.84 Spanish praise statements per session (range 0–7 statements) following intervention. The number of error corrections decreased from an average 8.61 English error correction statements per session (range 2–23 statements) to 0.19 English error correction statements per session (range 0–2 statements). The number of error corrections also decreased in the Spanish language from 6.21 statements per session (range 1–14 statements) to 0.11 statements per session (range 0–1 statements). These results indicate that educators were allocating their responding to praise statements rather than error correction.

Further evaluation of the type of praise statements indicate the educators increased their use of descriptive praise in both English and Spanish. During the baseline condition, the educators delivered descriptive praise in English an average of 2 statements per session (range 0–10 statements) and in Spanish an average of 0.19 statements per session (range 0–4 statements). After intervention, the educators delivered descriptive praise in English an average of 10.79 statements per session (range 1–23 statements) and in Spanish an average of 1.16 statements per session (range 0–6 statements).

Discussion

The results of the study indicate BST was effective in preparing educators to implement the CR-CBS in high-risk urban settings. Results demonstrated a functional relationship between the BST coaching and increased implementation of CR-CBS practices across five educators in two elementary school settings. Further, according to the social validity rating scores collected at the end of the study, two educator participants reported they agreed with statements (average of 4 points) indicating CR-CBS practices were effective in supporting appropriate behavior for their students, especially those students identified as engaging in challenging behavior in the classroom.

There has been growing interest in the behavior-analytic field to conceptualize culture (Brodhead, Durán, & Bloom, 2014; Fong et al., 2016; Fong & Tanaka, 2013) or apply behavior-analytic techniques with linguistically diverse populations (Aguilar, Chan, White, & Fragale, 2017; Padilla-Dalamau et al., 2011; Rispoli et al., 2011). However, this is the first study to apply modifications within a behavioral consultation framework. This study provides practicing behavior analysts with a structured checklist and example of surface adaptations in behavioral practice. Surface adaptations include matching the language of materials and the language of instruction, embedding stimuli from the cultural class into instructional materials, and striving to match cultures for the change agent and client. Application of these surface modifications into the checklist not only facilitated educator behavioral change but also served as an instrument to guide the performance feedback portion of the BST.

Behavior analysts should consider the cultural contingencies of their learners’ environment. In particular, the social environments of individual clients (or their culture) can provide important data regarding whether behaviors are likely to be reinforced or punished by their natural environment, thus helping the behavior analyst program for generalization. It also can give the behavior analyst data regarding potential reinforcers (or punishers) for the individual client. Within the context of behavioral consultation, culturally matched behavioral interventions can pair the natural change agent with previously established reinforcers, encourage rule-governed behavior by the matching language of instruction to the group’s reinforcement history, and facilitate skill acquisition by building upon already-established behavioral repertoires. It is highly recommended and increasingly important for behavior analysts to consider these modifications in their practice in not only the school environment but also the home and clinical environments (Fong et al., 2016).

Although this article provides an important first step when considering culture in behavioral consultation, there are some notable considerations for practicing behavior analysts. First, behavior analysts must be fluent in tacting their own culture to identify elements of their behavioral repertoire that have been shaped by their social environment (Fong et al., 2016). Tacting of these elements can serve as an important step in identifying responses that may need modification when serving diverse populations. That is, identification of one’s own culture can aid a behavior analyst in identification of biases that might inhibit practice. For example, behavior analysts might identify a response that is punished in their social environment as one that is reinforced in their clients’ social environment. This awareness can facilitate identification of responses targeted for intervention that may not have been considered if the behavior analyst were only considering his or her own reinforcement history.

Second, and very importantly, behavior analysts should take care to not generalize their responses based on clients’ distinguishable stimuli, as their clients may operate within multiple cultures (some perhaps unknown to the analyst). For example, within the South Texas community of the authors, there is a large Latinx population. However, there are varying levels of acculturation (or the extent to which an individual resides in multiple social environments), which can inform practice. A client might have extended family members from regions within Latin America (and therefore reside in that social environment) but operate predominantly within the social environment of their current community. It is best to engage clients and natural change agents in interventions so they may select targets best suited to clients’ reinforcement history. This is an important recommendation in line with the seventh dimension of applied behavior analysis (generality; Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968) and a tenet of social validity (Wolf, 1978) outlining that intervention targets should be socially relevant to the consumers we serve.

Some notable limitations of the current study include the small number of participants, the lack of quantitative student behavioral data, the short duration of the study, the use of a researcher-developed questionnaire that has not been psychometrically evaluated, and the low number of social validity responses. In addition, the researchers conducted this study in a predominately Latinx population with Mexican American educators. Although it may be surprising that the CR-CBS elements were not already present in the classrooms, the low baseline highlights the need for explicit educator training, even when educators may have a matched culture to their student populations. In addition, the results of this study are preliminary. There is a need to replicate this study with student populations that are diverse (but perhaps not as homogenous), with educators not matched to the culture to their students, and with other cultures and languages (beyond Latinx and Spanish). Future studies should include additional educator participants for greater evaluation of CR-CBS coaching outcomes, with treatment acceptability evaluated across all participants using a valid and reliable tool.

Future research should also experimentally evaluate the effects of CR-CBS on student behavior, comparing the effects of traditional class-wide behavior management to CR-CBS in schools with diverse cultural populations. Finally, future studies should include maintenance probes for both educator (treatment fidelity) and student behavior. Overall, this study provides preliminary evidence of cultural modifications within a behavior consultation framework. By aligning behavior management practices to the needs of diverse populations, educators can employ classroom practices that may potentially bolster the outcomes for culturally and linguistically diverse learners. It is in doing this that educators and behavior analysts alike can ensure equitable access to reinforcement within social environments.

Appendix A

Frequency

Instructions: Please use the below data sheet to take frequency data to inform your ratings for questions 10–13, 20, and 21 during the first 15 min of your observation. For every instance of praise or error correction, document a tally in the correct box to indicate whether the praise was in English or Spanish. In instances of praise, also document a tally under the column “Descriptive Praise” to indicate whether the praise included elements of the observed behavior. For example, “Nice job picking up the pencil” would count for descriptively praising a student who picked up a pencil, compared to “nice job,” which would only receive a tally under the “Praise” column and not receive a tally in the “Descriptive Praise” column.

| Praise | Error Correction | Descriptive Praise | |

| English | |||

| Spanish |

| Individual Opportunity to Respond | Group Opportunity to Respond | |

| English | ||

| Spanish |

Appendix B

Appendix C Teacher Questionnaire on Acceptability of Implementing CR-CBS

Funding

No funding to report.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Research Highlights

• This article operationally defines elements of culture surface adaptation within a behavior consultation framework.

• We present a rubric for evaluation of culturally responsive class-wide behavior supports.

• We provide data to evaluate the feasibility of implementing supports within a school environment.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aguilar JM, Chan JM, White PJ, Fragale C. Assessment of the language preferences of five children with autism from Spanish-speaking homes. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2017;26:334–347. doi: 10.1007/s10864-017-9280-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R, Steed EA. Culturally responsive pyramid model practices: Program-wide positive behavior support for young children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2016;36:165–175. doi: 10.1177/0271121416651164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer D, Wolf M, Risley T. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker CH, Cook KL, Borrego J. Addressing cultural variables in parent training programs with Latino families. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw CP, Waasdorp TE, Leaf PJ. Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1136–e1145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT, Durán L, Bloom SE. Cultural and linguistic diversity in recent verbal behavior research on individuals with disabilities: A review and implications for research and practice. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:75–86. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ. Bringing culture into parent training with Latinos. Cognitive Behavior Practice. 2010;17:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield-Davis K, Tenuto P, Jain S, McMurtry J. Professional ethical obligations for multicultural education and implications for educators. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal. 2011;15(1):95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer ED, Bennett KD. Implementing culturally responsive positive behavior interventions and supports in middle school classrooms. Middle School Journal. 2015;46:18–24. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2015.11461911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doll B, Zucker S, Brehm K. Resilient classrooms: Creating healthy environments for learning. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DuBay M, Watson LR, Zhang W. In search of culturally appropriate autism interventions: Perspectives of Latino caregivers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2018;48:1623–1639. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3394-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán LK, Roseth CJ, Hoffman P. An experimental study comparing English-only and transitional bilingual education on Spanish-speaking preschoolers’ early literacy development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2010;25:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon LM, O’Keeffe BV, Sugai G. Consideration of culture and context in school-wide positive behavior support: A review of current literature. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;14:209–219. doi: 10.1177/1098300712442242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Brodhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis Practice. 2016;9:84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Tanaka S. Multicultural alliance of behavior analysis standards for cultural competence in behavior analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 2013;8(2):17–19. doi: 10.1037/h0100970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoumis S, Seiverling L, Sturmey P. The effects of behavior skills training on correct teacher implementation of natural language paradigm teaching skills and child behavior. Behavioral Interventions. 2012;27:57–74. doi: 10.1002/bin.1334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Sugai G, Lewis-Palmer T, Todd AW. Teaching school-wide behavioral expectations. Report on Emotional & Behavioral Disorders in Youth. 2001;1(4):77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf

- McKenney EL, Mann KA, Brown DL, Jewell JD. Addressing cultural responsiveness in consultation: An empirical demonstration. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2017;27:289–316. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2017.1287575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales Y, Lutzker JR, Shanley JR, Guastaferro KM. Parent-infant interaction training with a Latino mother. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development. 2015;8:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Dalamau YC, Wacker DP, Harding JW, Berg WK, Schieltz KM, Lee JF, Kramer AR. A preliminary evaluation of functional communication training effectiveness and language preference when Spanish and English are manipulated. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2011;20:233–251. doi: 10.1007/s10864-011-9131-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra Cardona JR, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K, Bernal G. Culturally adapting an evidence-based parenting intervention for Latino immigrants: The need to integrate fidelity and cultural relevance. Family Process. 2012;51:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R. Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RF, Kincaid D. School-wide PBIS: Extending the impact of applied behavior analysis. Why is this important to behavior analysts? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;88:88–91. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity & Disease. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo MA, Castilla AP, Schwanenflugel PJ, Neuharth-Pritchett S, Hamilton CE, Arboleda A. Effects of a supplemental Spanish oral language program on sentence length, complexity, and grammaticality in Spanish-speaking children attending English-only preschools. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2010;41:3–13. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2009/06-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo MA, Morgan GP, Thompson MS. The efficacy of a vocabulary intervention for dual-language learners with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2013;56:748–765. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispoli M, Neely L, Healy O, Gregori E. Training public school special educators to implement two functional analysis models. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2016;25:249–274. doi: 10.1007/s10864-016-9247-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rispoli M, O’Reilly M, Lang R, Sigafoos J, Mulloy A, Aguilar J, Singer G. Effects of language implementation on functional analysis outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2011;20:224–232. doi: 10.1007/s10864-011-9128-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen B, Fairbanks S, Briesch A, Myers D, Sugai G. Evidence-based practices in classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Education and Treatment of Children. 2008;31(3):351–380. doi: 10.1353/etc.0.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Science and human behavior. New York, NY: Collier-Macmillan; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon BG, Klein SA, Hintze JM, Cressey JM, Peller SL. A meta-analysis of school-wide positive behavior support: An exploratory study using single-case synthesis. Psychology in the Schools. 2012;49:105–121. doi: 10.1002/pits.20625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugai G, O’Keeffe BV, Fallon LM. A contextual consideration of culture and school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;14:197–208. doi: 10.1177/1098300711426334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland KS, Alder N, Gunter PL. The effect of varying rates of opportunities to respond to academic requests on the classroom behavior of students with EBD. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11(4):239–248. doi: 10.1177/10634266030110040501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). USA quick facts. Retrieved September 29, 2018, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045217

- Vincent CG, Randall C, Cartledge G, Tobin TJ, Swain-Bradway J. Toward a conceptual integration of cultural responsiveness and schoolwide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2011;13(4):219–229. doi: 10.1177/1098300711399765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent CG, Tobin TJ. The relationship between implementation of school-wide positive behavior support (PBIS) and disciplinary exclusion of students from various ethnic backgrounds with and without disabilities. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2011;19:217–232. doi: 10.1177/1063426610377329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Horner J, Sturmey P. Component analysis of behavioral skills training in functional analysis. Behavioral Interventions. 2012;27:75–92. doi: 10.1002/bin.1339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11(2):203–214. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe K, Durán LK. Culturally and linguistically diverse parents’ perceptions of the IEP process: A review of current research. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners. 2013;13(2):4–18. [Google Scholar]