Abstract

l-isoleucine dioxygenase (IDO) is an Fe (II)/α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent dioxygenase that specifically converts l-isoleucine (l-Ile) to (2S, 3R, 4S)-4-hydroxyisoleucine (4-HIL). 4-HIL is an important drug for the treatment and prevention of type 1 and type 2 diabetes but the yields using current methods are low. In this study, the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system was used to knockout sucAB and aceAK gene in the TCA cycle pathway of Escherichia coli (E. coli). For single-gene knockout, the whole process took approximately 7 days. However, the manipulation time was reduced by 2 days for each round of gene modification for multigene editing. Using the genome-edited recombinant strain E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucABΔaceAK/pET-28a(+)-ido (2Δ-ido), the bioconversion ratio of L-Ile to 4-HIL was enhanced by about 15% compared to E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET-28a(+)-ido [BL21(DE3)-ido] strain. The CRISPR-Cas9 editing strategy has the potential in modifying multiple genes more rapidly and in optimizing strains for industrial production.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-2160-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: TCA cycle, l-Isoleucine dioxygenase, 4-Hydroxyisoleucine, CRISPR-Cas9, Genome editing

Introduction

4-Hydroxyisoleucine (4-HIL) is a natural non-proteogenic amino acid that was originally extracted from the Trigonella foenum-graecum seeds (Fowden et al. 1973). It is considered an effective drug for the treatment and prevention of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. 4-HIL has the unique functions of stimulating insulin secretion, and improving insulin resistance, without causing side effects such as hypoglycaemia in a type 2 diabetes model (Narender et al. 2006; Eidi et al. 2007; Singh et al. 2010). Additionally, 4-HIL has been reported to control weight gain and decrease the plasma triglyceride levels in type 2 diabetes animal models (Lucie et al. 2009). Furthermore, 4-HIL showed an effective antidiabetic activity in a type 1 diabetes model (Haeri et al. 2012).

(2S, 3R, 4S)-4-HIL is the major 4-HIL stereoisomer in fenugreek seeds, and shows the strong biological activity (Alcock et al. 1989). At present, the main method of 4-HIL production is fenugreek seed extraction, which has low yield (Haeri et al. 2012). Among the 4-HIL production methods, seed extraction and chemical synthesis methods are considered to have low efficiency, high cost, and heavy pollution (Jun et al. 2007; Smirnov et al. 2010b; Aouadi et al. 2012). In the past decade, with the discovery of l-isoleucine dioxygenase (IDO) from Bacillus thuringiensis 2e2, the synthesis process of 4-HIL by microorganisms has been developed (Tomohiro et al. 2009). IDO is an Fe (II)/α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent dioxygenase that specifically converts l-isoleucine (l-Ile) into 4-HIL. Subsequently, the IDO gene (ido) was cloned from B. thuringiensis and expressed in the engineered strain E. coli 2Δ (ΔsucAB, ΔaceAK), which transformed l-Ile into 4-HIL (Smirnov et al. 2010a). The 2Δ strain was constructed by deleting the sucAB (encoding α-KG dehydrogenase, EC 1.2.4.2) and aceAK genes (encoding isocitrate lyase, EC 4.1.3.1, and isocitrate dehydrogenase kinase/phosphatase, EC 2.7.11.5). This 2Δ strain did not grow due to the disruption of the path from α-KG to succinate in the TCA cycle; however, cell growth was restored by reconstituting the TCA cycle by the catalytic coupling of IDO with the TCA cycle (Smirnov et al. 2010a). This is mainly because IDO is able to catalyze α-KG and l-Ile to form succinate in the TCA cycle, thereby rebuilding the TCA cycle and achieving biotransformation of l-Ile into 4-HIL (Zhang et al. 2017). The design was to use the organism's own α-KG as a substrate to reduce α-KG substrate addition (Lin et al. 2015). Recently, another study utilized the l-Ile production characteristic of Corynebacterium glutamicum to realize the one-step synthesis of 4-HIL by the TCA cycle by the catalytic coupling of IDO with the TCA cycle. The production of 4-HIL has been further increased in microorganisms by overexpression of the PEPC gene (ppc) and the ASK gene (lysC) (Shi et al. 2015, 2016).

The above-mentioned biosynthesis of 4-HIL was based on modification of the microbial metabolic network. Metabolic engineering has been widely applied to modify microorganisms to produce industrially relevant biofuels or biochemicals. However, this industrially optimized strain requires modification of more than one gene, and simultaneous modification of various genes requires efficient tools to save time.

Currently, the most widely used gene editing methods in E. coli are homologous recombination and group II intron retrohoming (Karberg et al. 2001; Enyeart et al. 2013; Esvelt and Wang 2013). Methods using recombinant enzymes and group II intron retrotranscription leave scars in the genome that limit their application in allelic exchange (Karberg et al. 2001). Multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) based on single-stranded-DNA (ssDNA)-based gene modification by λ-Red can achieve genome-wide allelic exchange. This method is mediated by short ssDNA oligonucleotides, but there are some challenges in targeting multigene insertions of a defined length (Wang et al. 2009; Wang and Church 2011).

In E. coli, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/nuclease Cas protein 9 (Cas9) system has been used for gene editing including gene insertion, deletion, and replacement (Jiang et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013; Li et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2017; Cobb et al. 2015). CRISPR/Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes is a type II system that can use trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) and CRISPR RNA (crRNA) to guide Cas9 to the target DNA sequence (Elitza et al. 2011). In 2015, Yu et al. developed a CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing strategy that performs gene insertions and knockouts of both single and multiple DNA targets, with high efficiency (Yu et al. 2015).

In our previous study, a Bacillus sp. strain with IDO activity was isolated from the soil, and ido was cloned and expressed in E. coli to obtain a recombinant strain capable of 4-HIL synthesis (Fu et al. 2014). For time-saving gene editing and to further improve 4-HIL production, we reconstituted the TCA cycle with IDO to hydroxylate l-Ile in recombinant E. coli by the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system. We found that the bioconversion ratio of l-Ile to 4-HIL in the Δ-ido (69.12%) and 2Δ-ido (75.71%) strains was higher than that in the BL21 (DE)-ido (61.57%) strain.

Materials and methods

Materials

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5α was used as a cloning host. E. coli BL21(DE3) was used for genome deletion to obtain the E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucAB (Δ) and E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucABΔaceAK (2Δ) strains. These knockout strains were used for ido gene expression and 4-HIL production.

Table 1.

Strain and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmids | Descriptions | Sources or references |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | F−endA1 glnV44 thi-1 recA1 relA1 gyrA96 deoR nupG Φ80dlacZΔM15, Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169, hsdR17(rK− mK+), λ– | TaKaRa |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−)gal dcm (DE3) | Novagen/millipore |

| Δ | E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucAB | This study |

| 2Δ | E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucABΔaceAK | This study |

| Δ-ido | E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucAB/pET-28a(+)-ido | This sudy |

| 2Δ-ido | E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucABΔaceAK/pET-28a(+)-ido | This study |

| pCas | repA101(Ts) kan Pcas-cas9 ParaB-Red lacIq Ptrc-sgRNA-pMB1 | Genscript |

| pTargetF | pMB1 aadA sgRNA | Genscript |

| pTargetF-sucAB | pMB1 aadA sgRNA-sucAB | This study |

| pTargetF-aceAK | pMB1 aadA sgRNA-aceAK | This sudy |

| pTargetT-ΔsucAB | pMB1 aadA sgRNA-sucAB ΔsucAB (500 bp + 556 bp) | This study |

| pTargetT-ΔaceAK | pMB1 aadA sgRNA-sucAB ΔaceAK (500 bp + 501 bp) | This study |

| pET-28a( +)-ido | kan ido | Our previous study |

kan kanamycin resistance gene, aadA spectinomycin resistance gene, cat chloramphenicol resistance gene, Pcas-cas9 the cas9 gene with its native promoter, ParaB-Red the Red recombination genes with an arabinose-inducible promoter, Ptrc-sgRNA-pMB1 sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the pMB1 region with a trc promoter, sgRNA-sucAB sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the sucAB locus, sgRNA-aceAK sgRNA with an N20 sequence for targeting the aceAK locus, ΔsucAB (500 bp + 556 bp) editing template with 500 bp and 556 bp homologous DNA fragment in front and behind of sucAB, respectively, ΔaceAK (500 bp + 501 bp) editing template with 500 bp and 501 bp homologous DNA fragment in front and behind of aceAK, respectively,*** ido was amplified from Bacillus sp strain in previous study

The two-plasmid system consisted of the pCas and pTargetT plasmids (Table 1), which were used for genome editing. Plasmid pET-28a(+)-ido (Table 1) was constructed by amplifying the ido gene from the Bacillus sp. strain in our previous study (Fu et al. 2014), expressed in the Δ and 2Δ strains, and transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucAB/pET-28a(+)-ido (Δ-ido) and E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucABΔaceAK/pET-28a(+)-ido (2Δ-ido) strains, respectively.

Culture conditions

For gene editing, E. coli strains were grown in Luria Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, pH 7.0) with kanamycin (50 mg/L) or spectinomycin (50 mg/L) at 37 °C or 30 °C. The Δ and 2Δ strains were grown in A medium (Na2HPO4 8.5 g/L, KH2PO4 3.0 g/L, NaCl 0.5 g/L, NH4Cl 1.0 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O 1 g/L, glucose 15 g/L, tryptone 5 g/L, yeast extract 10 g/L). The Δ-ido and 2Δ-ido strains were grown in B medium (Na2HPO4 8.5 g/L, KH2PO4 3.0 g/L, NaCl 0.5 g/L, NH4Cl 1.0 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O 1 g/L, glucose 15 g/L, tryptone 5 g/L, yeast extract 10 g/L, α-KG 14 g/L, l-Ile 14 g/L, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) 0.1 mM).

Plasmid construction

pTargetT-ΔsucAB and pTargetT-ΔaceAK were constructed based on the pTargetF plasmid, according to a previously described method (Yu et al. 2015). pTargetF contains a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence, an N20 sequence, and multiple restriction sites (Table 1). However, pTargetT consists of an sgRNA sequence, an N20 sequence, multiple restriction sites, and the donor DNA used as the genome editing template. First, the sgRNA fragment was amplified from pTargetF using primers P1/P2 and P1/P3 (Table 2) with the modified N20 sequence at the 5′ ends of each primer (Table 3). This fragment was then inserted into the SpeI/SalI-digested pTargetF to obtain pTargetF-sucAB and pTargetF-aceAK, respectively (Table 1). Next, pTargetT-ΔsucAB and pTargetT-ΔaceAK were constructed by inserting the de novo synthesized donor DNA template (~ 500 bp sequence homologous to the upstream or downstream of the targeted region) (Table 4) into the BglII/XhoI-digested pTargetF-sucAB and pTargetF-aceAK respectively (Table 1).

Table 2.

The primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | TTCAAAAAAAGCACCGACTCGG | |

| P2 | GTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTGACCGGGCAGGGTGTGGTTCGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | sgRNA-sucAB fragment was amplified by P1/P2 |

| P3 | GTCCTAGGTATAATACTAGTCTACAACCGTTGCCGAACGTGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC | sgRNA-aceAK fragment was amplified by P1/P3 |

| P4 | CAGGCTTGTTAGCGGCATATCGT | sucAB gene knockout colonies were identified by colony PCR by P4/P5 |

| P5 | TTTACAACTTTCACACCGCCCGCTT | |

| P6 | GTATTCAACGACATTCTCGGCTC | AceAK gene knockout colonies were identified by colony PCR by P6/P7 |

| P7 | TGGCAATTGGTCAGAATCAC |

Table 3.

N20 sequences used in this study

| Targeted region | N20 + PAM |

|---|---|

| sucAB | GACCGGGCAGGGTGTGGTTCAGG |

| aceAK | AGCAGCAGCTGTCGGATATGGG |

Table 4.

Donor DNA sequence

| Homologous DNA fragment (5′–3′) in front (black) and behind (red) | |

|---|---|

| sucAB | CAGGCTTGTTAGCGGCATATCGTTTCCTGATCGATAGCCGTGATACCGAGACTGGCAGCCGCCTCGACGGTTTGAGCGATGCATTCAGTGTATTCCGCTGTCACAGCATCATGAACTGCGTCAGTGTATGTCCGAAGGGGCTGAACCCGACGCGCGCCATCGGCCATATCAAGTCGATGTTGTTGCAGCGTAATGCGTAAACCGTAGGCCTGATAAGACGCGCAAGCGTCGCATCAGGCAACCAGTGCCGGATGCGGCGTGAACGCCTTATCCGGCCTACAAGCCATTACCCGTAGGCCTGATAAGCGCAGCGCATCAGGCGTAACAAAGAAATGCAGGAAATCTTTAAAAACTGCCCCTGACACTAAGACAGTTTTTAAAGGTTCCTTCGCGAGCCACTACGTAGACAAGAGCTCGCAAGTGAACCCCGGCACGCACATCACTGTGCGTGGTAGTATCCACGGCGAAGTAAGCATAAAAAAGATGCTTAAGGGATCACGTAGTTTAAGTTTCACCTGCACTGTAGACCGGATAAGGCATTATCGCCTTCTCCGGCAATTGAAGCCTGATGCGACGCTGACGCGTCTTATCAGGCCTACGGGACCACCAATGTAGGTCGGATAAGGCGCTAGCGCCGCATCCGACAAGCGATGCCTGATGTGACGGTTAACGTGTCTTATCAGGTCTACGGGGACCACCAATGTAGGTCGGATAAGGCGCAAGCGCCGCATCCGACAAGCGATGCCTGATGTGACGTTTAACGTGTCTTATCAGGCCTACGGGTGACCGACAATGCCCGGAAGCGATACGAAATATTCGGTCTACGGTTTAAAAGATAACGATTACTGAAGGATGGACAGAACACATGAACTTACATGAATATCAGGCAAAACAACTTTTTGCCCGCTATGGCTTACCAGCACCGGTGGGTTATGCCTGTACTACTCCGCGCGAAGCAGAAGAAGCCGCTTCAAAAATCGGTGCCGGTCCGTGGGTAGTGAAATGTCAGGTTCACGCTGGTGGCCGCGGTAAAGCGGGCGGTGTGAAAGTTGTAAA |

| aceAK | GTATTCAACGACATTCTCGGCTCCCGTAAAAATCAGCTTGAAGTGATGCGCGAACAAGACGCGCCGATTACTGCCGATCAGCTGCTGGCACCTTGTGATGGTGAACGCACCGAAGAAGGTATGCGCGCCAACATTCGCGTGGCTGTGCAGTACATCGAAGCGTGGATCTCTGGCAACGGCTGTGTGCCGATTTATGGCCTGATGGAAGATGCGGCGACGGCTGAAATTTCCCGTACCTCGATCTGGCAGTGGATCCATCATCAAAAAACGTTGAGCAATGGCAAACCGGTGACCAAAGCCTTGTTCCGCCAGATGCTGGGCGAAGAGATGAAAGTCATTGCCAGCGAACTGGGCGAAGAACGTTTCTCCCAGGGGCGTTTTGACGATGCCGCACGCTTGATGGAACAGATCACCACTTCCGATGAGTTAATTGATTTCCTGACCCTGCCAGGCTACCGCCTGTTAGCGTAAACCACCACATAACTATGGAGCATCTGCACGTAAAGCTTCCATATAATTTTTCTCCGCAATGTATCGAGGGTTATCCGTAAAGCCAAAGCTTTCAGCCATCTTATTTAATGTATTAAGGATTAATTCAGCAATAACCCGGTGACCCAATTCAAAAGCCAACTCAAAGGCAGAGTATTTTTGTGGGGCTTTGTGTTGCCAAAAATCCATAATATCTTCAGCGGTAAATCCAAACAGGCGTGCATGGTTAGATAAAGCAAGATAAACCGTCTCTACAACATTTTGTTGTTTATGCTGTATCGCTGAAAACAAACCGGGATATTCATTAGAATTATTTGCCAGGAGGAGGGGCTTCATATTTTTTTTATCGAATTTAAACGTATTAAACAGAGTGGGTAATGCGTTAAAAATAGTATTAATAACGTTCATATGTCCACTATTATAGGTAGTCAACATTTCTGTTCTATGTAGTTCTGGCATTTTCTGGAGCTGAATCATCAGTTGCGTAAGTTGGTGATTCTGACCAATTGCCA |

Genome editing

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) competent cells were transformed with pCas and pTargetT-ΔsucAB by electroporation at 2.5 kV in a 2 mm Gene Pulser cuvette (Bio-Rad). l-arabinose (10 mM final concentration) was added to the culture for λ-Red induction. For isolation, the culture was then spread onto the surface of LB agar plates containing spectinomycin (50 mg/L) and kanamycin (50 mg/L) and incubated overnight at 30 °C. The Δ mutant strains with pCas and pTargetT-ΔsucAB were detected by colony PCR and DNA sequencing. For continual genome editing, the cells transformed with pTargetT-ΔsucAB were cured for 13 h in LB medium containing kanamycin (50 mg/L) and IPTG (0.5 mM). These cells were isolated by spreading onto the surface of an LB agar plate containing kanamycin (50 mg/L). The cured pTargetT-ΔsucAB cells were confirmed by their sensitivity to spectinomycin (50 mg/L). The colonies cured with pTargetT-ΔsucAB were used in the next round for aceAK gene editing. The method of aceAK gene editing was the same as the sucAB deletion method. Finally, the 2Δ strains were obtained by curing pTargetT-ΔaceAK with IPTG and pCas while growing overnight at 37 °C. The mutant strains were screened using resistance genes and detected by PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Bioconversion conditions

For biotransformation of l-Ile into 4-HIL, the different mutant strains were immersed in a bioconversion medium ((NH4)2SO4 5 g/L, KH2PO4 1.5 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O 1 g/L, FeSO4·7H2O 1 g/L, VC 5 mM, CaCl2 1 mM, glucose 54 g/L, α-KG 26.2 g/L, l-Ile 26.2 g/L, and IPTG 0.1 mM, pH 7.0) for 24 h at 37 °C, and shaken at 200 rpm by a reciprocating shaker. Subsequently, the 4-HIL concentrations were measured by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Analytical methods

Cell growth was estimated by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm at different times.

To determine the concentrations of l-Ile and 4-HIL, the cell culture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was derivatized by 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chloride (Fmoc-Cl) acetonitrile solution. Finally, the amino adamantane (ADAM) acetonitrile/water solution (1:1 v/v) was added to derivatize supernatant to prevent excessive Fmoc-Cl hydrolysis. The solution was filtered through a 0.22-micron organic membrane and detected by HPLC (Agilent 1200 series, Hewlett–Packard), equipped with a Diomansil C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm; Agilent) and UV-detector (263 nm). Analysis was performed at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with a mobile phase of 50 mM NaAc-HAc buffer (pH 4.2) and acetonitrile (Fu et al. 2014).

Results

pTargetT-ΔsucAB and pTargetT-ΔaceAK were constructed to provide sgRNA and DNA template

Continual genome editing in E. coli using two plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 systems has been reported (Yu et al. 2015). The systems were mainly composed of the pCas and pTarget plasmids. pCas was composed of cas9, λ-Red with the ParaB promoter (induced by l-arabinose), a temperature-sensitive replicon repA101 (Ts), and an sgRNA targeting the pTarget pMB1 replicon (sgRNApMB1) with the Ptrc promoter (induced by IPTG) (Fig. 1a). l-Arabinose-induced λ-Red significantly improved the CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutation rate of the target genes. The temperature-sensitive replicon was able to cure pCas plasmids at 37 °C. sgRNApMB1 was able to guide Cas9 to cut the pMB1 replicon in pTarget plasmids, and thus, cure the plasmid (Fig. 1a). There are two versions of pTarget series, pTargetT and pTargetF. pTargetF contains the N20 sequence, the sgRNA sequence, the pMB1 replicon, and multiple restriction sites. Additional donor DNA must be provided as the template. The pTargetT contains the N20 sequence, the sgRNA sequence, genome editing template donor DNA, the pMB1 replicon, and multiple restriction sites (Fig. 1a). The pTargetT donor DNA has a 250–550 bp homologous sequence on each side (upstream or downstream) of the targeted region in the genome (Table 4). To knock out the sucAB and aceAK genes in E. coli, pTargetT-ΔsucAB and pTargetT-ΔaceAK were constructed based on the pTargetF plasmid (Table 1). This process took approximately 3 days. The pCas plasmid was provided by Genscript (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system and reconstitution of the TCA cycle. a Diagram of continual genome editing with the pCas and pTargetT two-plasmid system. pCas was composed of cas9, λ-Red with the ParaB promoter (induced by l-arabinose), a temperature-sensitive replicon repA101 (Ts), and an sgRNA targeting the pTarget pMB1 replicon (sgRNApMB1) with the Ptrc promoter (induced by IPTG). pTargetT contained the sgRNA sequence, N20, multiple restriction sites, and the donor DNA used as the genome editing template. The competent cells were transformed with pCas and pTargetT. Next, the target gene was knocked out with IPTG induction. Another gene could be further knocked out by adding pTargetT containing the new sgRNA. b IDO shunts the α-KG from the TCA cycles when succinate synthesis is blocked in the mutant strain, and reconstitution of the TCA cycle results in the conversion of l-Ile to 4-HIL

Application of the two-plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 systems in E. coli BL21(DE3) for continuous gene deletion

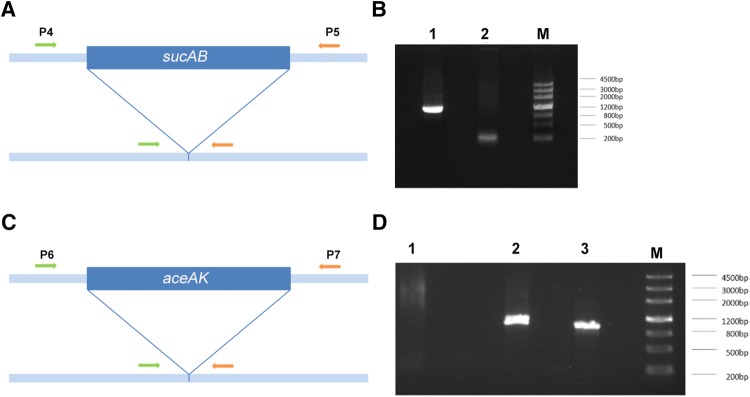

The sucAB gene deletion in BL21(DE3) was an untraceable knockout generated by the two-plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 system. E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells were transformed with pCas and pTargetT-ΔsucAB, and the cas9 gene was expressed under L-arabinose-mediated induction (Fig. 1a). sgRNA-sucAB then guided Cas9 to the target gene region, which was knocked out with the donor DNA and the λ-Red recombinant enzyme (Fig. 1a). The PCR amplification fragment, which was obtained from screening the mutant strains, was 1056 bp, indicating that the sucAB gene was knocked out (Table 2) (Fig. 2a, b line 1). No amplification fragment (the PCR amplification fragment was 5090 bp, which was too long to be amplified) indicated that sucAB was not knocked out (Fig. 2b line 2). The sequencing results confirmed that sucAB had been knocked out (Supplement 1). Finally, under the induction of IPTG, sgRNApMB1 guided Cas9 to cut the pMB1 replicators of the pTargetT-ΔsucAB plasmid to remove pTargetT-ΔsucAB resulting in the Δ strain (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

PCR analysis of mutant strains. a Primers (P4/P5) were designed to target both ends of the sucAB gene for PCR detection of positive strains. The PCR amplification fragment of 1056 bp indicated that the sucAB gene was knocked out, while no amplification fragment indicated that this gene was not knocked out. b Line 1, E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucAB; line 2, E. coli BL21(DE3); M, DNA marker. c Primers (P6/P7) were designed to target both ends of the aceAK gene for PCR detection of positive strains. The PCR amplification fragment of 1001 bp indicated that the aceAK gene was knocked out, while no amplification fragment indicated that this gene was not knocked out. d Line 1, E. coli BL21(DE3); line 2, E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucAB; line 3, E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔaceAK. Line 2 and line 3 are from the same colony, indicating that this strain is E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔsucABΔaceAK

To knock out aceAK simultaneously, the Δ strain was transformed with pTargetT-ΔaceAK, and then the aceAK gene was deleted under l-arabinose-mediated induction. The PCR amplification fragment was 1001 bp (Fig. 2c, d line 3), indicating that the aceAK gene was knocked out. No amplification fragment (the PCR amplification fragment was 4323 bp, which was too long to be amplified) indicated that aceAK was not knocked out (Fig. 2d line 1). The sucAB gene PCR amplification fragment from the same colony was 1056 bp (Fig. 2d line 2), indicating that the sucAB gene was also knocked out. The sequencing results confirmed that aceAK had been knocked out (Supplement 2). Under the induction of IPTG, sgRNApMB1 guided Cas9 to cut the pMB1 replicators of the pTargetT-ΔaceAK plasmid to remove pTargetT-ΔaceAK resulting in the 2Δ strain (Table 1).

For single-gene knockout, the whole process (from plasmid construction to obtaining the mutant strain) took approximately 7 days. However, the manipulation time was reduced by 2 days for each round of gene modification for multigene editing.

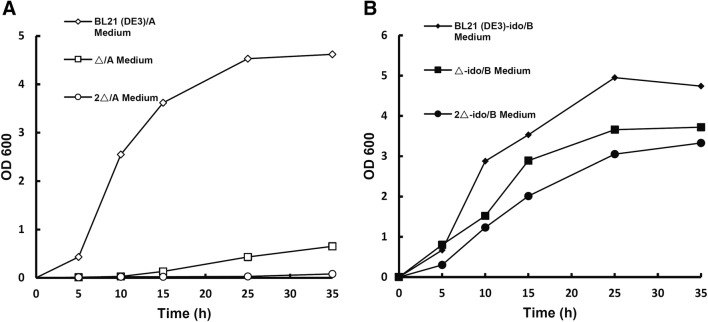

Mutant strains grown in medium

The Δ mutant strain was able to block the synthesis of succinyl-CoA from α-KG due to the deletion of sucAB. The 2Δ mutant strain not only blocked succinyl-CoA synthesis due to the deletion of sucAB, but also blocked the synthesis of succinate from isocitrate due to deletions of aceAK (Fig. 1b). The data showed that the Δ and 2Δ mutant strains could not grow in A medium (Fig. 3a) because the TCA cycle was blocked in E. coli.

Fig. 3.

Mutant strains grown in medium. a The growth of different mutant strains in A medium at different times. BL21(DE3) (open diamonds) was able to grow well, while the Δ (open squares)and 2Δ (open circles) mutant strains could not grow in A medium. b The cell growth of the Δ-ido (solid squares) and 2Δ-ido (solid circles) strains was restored compared to that of the mutant strains without the ido gene. The BL21(DE3)-ido (solid diamonds) strain was able to grow well

Succinate synthesis was blocked in these mutant strains, and the accumulation of α-KG increased. However, the α-KG-dependent hydroxylase reaction can couple the oxidation (decarboxylation) of α-KG to succinate with substrate hydroxylation. Thus, IDO may shunt α-KG from the TCA cycle when succinate synthesis is blocked, and then restore cell growth (Fig. 1b). The data showed that the Δ-ido and 2Δ-ido reconstituted strains partially restored cell growth compared to the mutant strains in B medium, although the Δ-ido strain grew better than the 2Δ-ido strain (Fig. 3b). This may indicate that IDO shunts the blocked TCA cycle and restores cell growth.

Biotransformation of l-Ile into 4-HIL in mutant strains

To detect the biotransformation of l-Ile into 4-HIL in the different mutant strains by IDO coupling the TCA cycle, 4-HIL production was measured in a bioconversion medium at 24 h. The data showed that 200 mM l-Ile could produce 143 mM of 4-HIL in the BL21(DE3)-ido strain; thus, the bioconversion ratio of l-Ile to 4-HIL was 61.57%. However, the l-Ile/4-HIL bioconversion ratio was 69.12% and 75.71% in the Δ-ido and 2Δ-ido reconstituted strains, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Biotransformation of l-isoleucine into 4-HIL in different strains at 24 h

| Strain | l-Ile (mM) | 4-HIL (mM) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BL21 (DE3)-ido | 200 | 123.14 | 61.57 |

| △-ido | 200 | 138.24 | 69.12 |

| 2△-ido | 200 | 151.42 | 75.71 |

Discussion

4-HIL is considered an effective drug for the treatment and prevention of diabetes (Narender et al. 2006; Eidi et al. 2007; Lucie et al. 2009; Haeri et al. 2012). Presently, fenugreek seed extraction, which has low yield, is the main 4-HIL production method. Recently, with the discovery of IDO, efforts have been aimed at the mass production of 4-HIL by modification of microbial metabolic pathways using genetic engineering (Smirnov et al. 2010a; Kivero and Smirnov 2012; Shi et al. 2015, 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). These studies, however, were based largely on traditional genetic engineering methods, which can be time-consuming when more than one gene needs to be modified to optimize microbial strains of industrial significance. To edit multiple genes, efficient tools are required to save time.

In this study, according to the characteristics of IDO to oxidize α-KG into succinate, the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system was used to modify the TCA cycle in BL21(DE3) to achieve a high yield of 4-HIL. pTargetT-ΔsucAB and pTargetT-ΔaceAK were constructed within 3 days by inserting the N20-sgRNA sequence and the donor DNA template into pTargetF. The sucAB and aceAK gene deletions each took 2 days. An additional 2 days were required for curing the pTargetT and pCas plasmids (Fig. 1a). For single-gene knockout, the whole process took approximately 7 days. However, the manipulation time was reduced by 2 days for each round of gene modification for multigene editing (Fig. 1a). We found that the biotransformation of l-Ile into 4-HIL in the Δ-ido (69.12%) and 2Δ-ido (75.71%) strains was higher than that in the BL21 (DE3)-ido (61.57%) strain (Table 5).

Although the CRISPR-Cas9 system is a highly efficient genome editing tool, the high rate of off-target effects is a major problem. However, some methods have been used to reduce off-target effects, including the cas9 nickase mutant and cooperative use of offset nicking.

Conclusion

For metabolic engineering based on cell network systems, this CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system can rapidly knock out different genes to optimize microbial strains to meet industrial production levels.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (21336009, 21676120, 31872891), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20151124), the 111 Project (111-2-06), the High-end Foreign Experts Recruitment Program (GDT20183200136), the Program for Advanced Talents within Six Industries of Jiangsu Province (2015-NY-007), the National Program for Support of Top-notch Young Professionals, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JUSRP51504), the Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, the Jiangsu province "Collaborative Innovation Center for Advanced Industrial Fermentation" industry development program, Top-notch Academic Programs Project of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and the National First-Class Discipline Program of Light Industry Technology and Engineering (LITE2018-09).

Author contributions

JA constructed plasmids and generated mutant strains and wrote manuscript. WZ was responsible for bioconversion of l-ile to 4-HIL. XJ worked on mutant strains growth experiments. YN and YX designed the experiments and revise the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All of authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Yao Nie, Email: ynie@jiangnan.edu.cn.

Yan Xu, Email: yxu@jiangnan.edu.cn.

References

- Alcock NW, Crout DHG, Gregorio MVM, Lee E, Pike G, Samuel CJ. Stereochemistry of the 4-hydroxyisoleucine from Trigonella foenum-graecum. Phytochemistry. 1989;28(7):1835–1841. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97870-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aouadi K, Jeanneau E, Msaddek M, Pralyabcd JP. 1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition of a chiral nitrone to ()-1,4-dichloro-2-butene: a new efficient synthesis of (2,3,4)-4-hydroxyisoleucine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53(23):2817–2821. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.03.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb RE, Wang Y, Zhao H. High-efficiency multiplex genome editing of Streptomyces species using an engineered CRISPR/Cas system. Acs Synth Biol. 2015;4(6):723–728. doi: 10.1021/sb500351f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidi A, Eidi M, Sokhteh M. Effect of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) seeds on serum parameters in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Nutr Res. 2007;27(11):728–733. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2007.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elitza D, Krzysztof C, Sharma CM, Karine G, Yanjie C, Pirzada ZA, Eckert MR, Jörg V, Emmanuelle C. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature. 2011;471(7340):602–607. doi: 10.1038/nature09886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyeart PJ, Chirieleison SM, Mai ND, Perutka J, Quandt EM, Yao J, Whitt JT, Keatinge-Clay AT, Lambowitz AM, Ellington AD. Generalized bacterial genome editing using mobile group II introns and Cre-lox. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9(1):685–685. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esvelt KM, Wang HH. Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9(1):641. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden L, Pratt HM, Smith A. 4-Hydroxyisoleucine from seed of Trigonella foenum-graecum. Phytochemistry. 1973;12(7):1707–1711. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(73)80391-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M, Nie Y, Mu X, Xu Y, Xiao R. A novel isoleucine dioxygenase and its expression in recombinant Escherichia coli for synthesis of 4-hydroxyisoleucine. Chem Ind Eng Prog. 2014;33(11):3037–3044. [Google Scholar]

- Haeri MR, Limaki HK, White CJ, White KN. Non-insulin dependent anti-diabetic activity of (2S, 3R, 4S) 4-hydroxyisoleucine of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum) in streptozotocin-induced type I diabetic rats. Phytomedicine. 2012;19(7):571–574. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):233–239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun O, Hiroyuki Y, Junichi M, Yuko D, Nobuyuki H, Tomohiro K, Noriki N, Smirnov SV, Samsonova NN, Kozlov YI. Synthesis of 4-hydroxyisoleucine by the aldolase-transaminase coupling reaction and basic characterization of the aldolase from Arthrobacter simplex AKU 626. J Agric Chem Soc Jpn. 2007;71(7):1607–1615. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karberg M, Guo H, Zhong J, Coon R, Perutka J, Lambowitz AM. Group II introns as controllable gene targeting vectors for genetic manipulation of bacteria. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19(12):1162–1167. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivero AD, Smirnov SV. Modification of E. coli central metabolism to optimize the biotransformation of l-isoleucine into 4-hydroxyisoleucine by enzymatic hydroxylation. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2012;48(7):639–644. doi: 10.1134/S0003683812070034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Lin Z, Huang C, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Tang YJ, Chen T, Zhao X. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using CRISPR–Cas9 meditated genome editing. Metab Eng. 2015;31:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Fan K, Zhao J, Ji J, Wu L, Yang K, Tao Y. Reconstitution of TCA cycle with DAOCS to engineer Escherichia coli into an efficient whole cell catalyst of penicillin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(32):9855–9859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502866112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucie J, Laurent H, Karen E, Nigel L. 4-Hydroxyisoleucine: a plant-derived treatment for metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10(4):353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narender T, Puri A, Shweta KT, Saxena R, Bhatia G, Chandra R. 4-hydroxyisoleucine an unusual amino acid as antidyslipidemic and antihyperglycemic agent. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16(2):293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F, Niu T, Fang H. 4-Hydroxyisoleucine production of recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum ssp. lactofermentum under optimal corn steep liquor limitation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(9):3851–3863. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6481-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F, Fang H, Niu T, Lu Z. Overexpression of ppc and lysC to improve the production of 4-hydroxyisoleucine and its precursor l-isoleucine in recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum ssp. lactofermentum. Enzym Microb Technol. 2016;87–88:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AB, Tamarkar AK, Narender T, Arvind Kumar S. Antihyperglycaemic effect of an unusual amino acid (4-hydroxyisoleucine) in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Nat Prod Res. 2010;24(3):258–265. doi: 10.1080/14786410902836693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov SV, Kodera T, Samsonova NN, Kotlyarova VA, Rushkevich NY, Kivero AD, Sokolov PM, Hibi M, Ogawa J, Shimizu S. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli to produce (2S, 3R, 4S)-4-hydroxyisoleucine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;88(3):719–726. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov SV, Samsonova NN, Novikova AE, Matrosov NG, Rushkevich NY, Kodera T, Ogawa J, Yamanaka H, Shimizu S. A novel strategy for enzymatic synthesis of 4-hydroxyisoleucine: identification of an enzyme possessing HMKP (4-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-keto-pentanoate) aldolase activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;273(1):70–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomohiro K, Smirnov SV, Samsonova NN, Kozlov YI, Ryokichi K, Makoto H, Jun O, Kenzo Y, Sakayu S. A novel l-isoleucine hydroxylating enzyme, l-isoleucine dioxygenase from Bacillus thuringiensis, produces (2S,3R,4S)-4-hydroxyisoleucine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390(3):506–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HH, Church GM. Chapter eighteen—multiplexed genome engineering and genotyping methods: applications for synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. Methods Enzymol. 2011;498:409–426. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385120-8.00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HH, Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Sun ZZ, George X, Forest CR, Church GM. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. Nature. 2009;460(7257):894–898. doi: 10.1038/nature08187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Biao C, Chunlan D, Bingbing S, Junjie Y, Sheng Y. Multigene editing in the Escherichia coli genome via the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(7):2506. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03992-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Rho M, Tang H, Doak TG, Ye Y. CRISPR-Cas systems target a diverse collection of invasive mobile genetic elements in human microbiomes. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R40. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Ma J, Li Z, Liang Y, Xu Q, Xie X, Chen N. A strategy for l-isoleucine dioxygenase screening and 4-hydroxyisoleucine production by resting cells. Bioengineered. 2017;9(4):00–00. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2017.1304872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Zhao D, Qiu H, Fan F, Man S, Bi C, Zhang X. The CRISPR/Cas9-facilitated multiplex pathway optimization (CFPO) technique and its application to improve the Escherichia coli xylose utilization pathway. Metab Eng. 2017;43(Pt A):37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.