Abstract

Background: Mobile phone-based text messages have been used to address alcohol use disorder in younger populations by promoting abstinence, decreased alcohol intake, and moderation.

Methods: A meta-analysis was conducted to summarize the effectiveness of mobile phone text messaging to address problem drinking by youth and younger adults.

Results: Authors systematically searched PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, APA PsycNET, and the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials for literature published in the past 8 years (2010–2018). Randomized control trials and pre–post studies of younger people that used the problem drinking criteria of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) were included in the meta-analysis.

Conclusions: The meta-analysis suggests that text message-based interventions might not be effective in decreasing alcohol intake in the younger populations.

Keywords: youth, younger adults, alcohol, problem drinking, text message, short message service, telemedicine

Introduction

Alcohol misuse among younger adults (age 20–39 years) is a public health problem. Approximately 25% of younger adult deaths are attributable to alcohol.1 In a national survey, ∼29% of 12th graders and ∼40% of college students reported binge drinking.2 During adolescence, many young people begin to experiment with alcohol. Globally, in 2010, alcohol misuse was the fifth leading risk factor for death and disability in the young.1 A study found that ∼78% of adolescents in the United States consumed alcohol by age 18 and about 47% of them drank on a regular basis.3 In a different study, about two out of five college students engaged in binge drinking, which was associated with wide range of adverse outcomes including death, traffic accidents, and lower grades.4 Another study showed an association between adolescent problem drinking behavior and persistent changes in neurobiology and adult behaviors.5 In 2015, an estimated 623,000 American adolescents aged 12–17 years had alcohol use disorders.6

Preventive methods are preferred to help youth and younger adults control or abstain from alcohol consumption. Health care givers have taken several approaches, such as individual counseling, group counseling, school-based interventions, family interventions, and community-based interventions, to reduce high levels of weekly alcohol consumption as well as the frequency of binge drinking, and generally have had positive results.7 Because of the widespread use of smartphones and extensive use of texting by adolescents and younger adults, a potentially more intense, frequent, and directly tailored intervention can be delivered by mobile phone text messaging systems. College students and younger adults (<39 years) are more likely to be binge drinkers,2 and their high cell phone use may play a large preventive role.

Mobile phones have been used as a tool to communicate with patients with problem drinking through websites, phone calls, and phone-based text messaging or short message services (SMSs).8 Mobile phones have also been used for surveillance.9 Mobile text messages have been used in various ways in younger populations to address alcohol-related problems. One notable study used mobile text as a tool to measure readiness to change alcohol behavior, and another was a feasibility study of texting as an intervention vehicle for university students.10,11 Other similar studies on mobile text-based interventions have included patients with comorbid disorders, such as depression, and patients on naltrexone, with either no effect, or some positive effect on outcomes.12,13 A number of pilot randomized controlled and pre–post studies of alcohol abuse interventions have been conducted to assess the appropriateness and effectiveness of text messaging to decrease binge drinking, average weekly drinking, and number of drinks for a period of months.14,15 Mobile texts to avoid problem drinking may evoke negative reactions in adolescents.16 Therefore, the main goal of this study was to analyze the effectiveness of mobile phone-based text messages as a preventive intervention for youth and younger adult populations' problem drinking.

Methods

A systematic search for relevant recent articles was conducted from 2010 to 2018 in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, APA PsycNET, and Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials. The search included literature that investigated text message reminders for alcohol-related behavioral interventions. The following search terms were used: alcohol, adolescents, college students, youth, younger adults, problem drinking, drinking habit, drinking pattern, risky single occasion drinking, alcohol use, binge drinking, drinking, reminder, text, short message service, and mobile phones. Any unpublished or ongoing studies were also considered, and all the relevant studies initially were included.

Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and pre–post studies were meta-analyzed. In pre–post studies, participants served as both control and experimental, subjects being observed and measured for a period before the intervention and after the intervention. Included studies also had to be of college students and younger adults (<39 years). All included studies had frequent and tailored text messages and reported objective outcomes related to one or more of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) drinking parameters described in Table 1. Message size and frequency varied widely, with reported frequencies ranging from twice weekly to four to six times daily. Some studies did not report frequency, only that the number of messages sent was tailored to their degree of risk group. For all of the RCTs and pre–post studies, risk analysis for confounding factors was also made using the Cochrane “Risk of Bias” tool.17 Articles with selective reporting of outcomes, with inadequate reporting, and unavailability of data were excluded. Moreover, only studies of groups without any comorbid disorders were included. Authors of studies included in the meta-analysis were contacted for data verification, and studies for which data could not be verified were excluded. In studies with more than one experimental group, data for the optimally tailored group were chosen.

Table 1.

NIAAA Definition of Standard Drink and Binge Drinking21

| STANDARD DRINK | BINGE DRINKING |

|---|---|

| • Any drink that contains about 14 g of pure alcohol (about 0.6 oz. or 1.2 tablespoons), or • 12 oz. of beer or cooler (∼5% alcohol), or • 8–9 oz. of malt liquor (∼7% alcohol), or • 5 oz. of table wine (∼12% alcohol), or • 1.5 oz. of 80-proof distilled spirits (40% alcohol) |

• For males: Five or more alcoholic drinks on the same occasion at least 1 day a month, or • For females: Four or more alcoholic drinks on the same occasion at least 1 day a month, or |

| Average daily consumption of more than two standard drinks in men and one standard drink in women and/or there is one or more RSOD within the last month. | Any consumption of alcohol in a single timeframe that raises BAC of 0.08 at least 1 day in a month. |

BAC, blood alcohol concentration; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; RSOD, risky single occasion drinking.

Because random effects model represents a more natural method, and the heterogeneity of the studies could not be readily explained, random effects were chosen for all meta-analysis forest plots.18 The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). The primary outcome measured in the study was a decrease in the number of drinking events or a reduction in the amount of alcohol intake in the experimental group versus the control group. Because the duration of intervention could affect outcomes, the analyses of studies were stratified as short-term interventions (6–12 weeks) and long-term interventions (6–9 months). Reduction of events was calculated from the baseline for both experimental and control groups. If there was an actual increase in the events, a nullifying adjustment was made for the negative outcome. All included studies had preventive interventions and studies that included text messages augmented by web-based interventions were not included.19 PRISMA guidelines were reviewed and followed to meet its requirements.20

For short-term interventions, a systematic search yielded dichotomous data sets. Therefore, meta-analytic estimates of intervention effects were generated using random-effects models and the Mantel Haenszel test to calculate the weighted average of the odds ratios. Effect sizes were calculated as odds ratios for events (e.g., number of reductions in binge drinking) or standard deviation of the mean standard drinks (defined by the NIAAA criteria). Heterogeneity for each intervention also was measured across the studies. When information was not adequate, and more justification was required, study authors were contacted for clarification and missing information.

Results

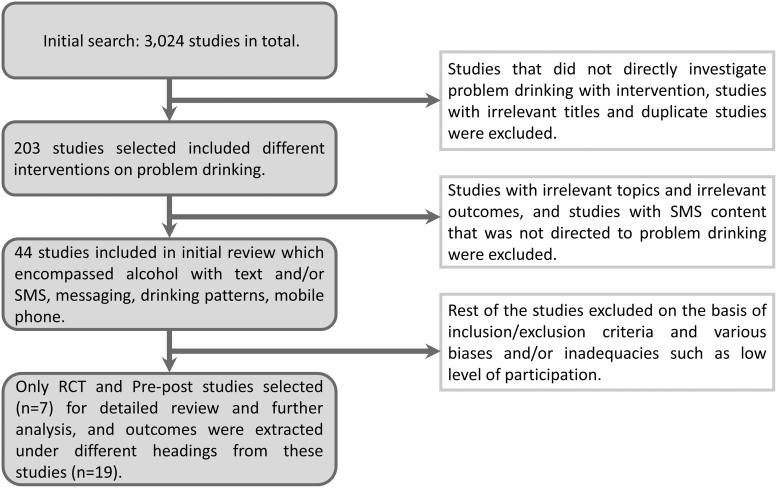

The systematic search initially identified 3,024 articles, but 2,821 articles were excluded because the studies did not include interventions on problem drinking. Out of the 203 articles selected in the first screening, only 44 of the studies included alcohol misuse and interventions with mobile phone-based text messaging/SMS. Only seven of these studies were RCTs and pre–post studies. From the final seven selected studies, 18 relevant outcomes were extracted. Figure 1 summarizes the search strategy, and Table 2 lists the seven selected studies and their outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Study selection process. RCT, randomized control trial, SMS, short message service.

Table 2.

Data Extracted for Meta-analysis

| AUTHOR | YEAR | STUDY TYPE | LOCATION | STUDY POPULATION | STUDY DURATION | INTERVENTION | INTERVENTION PARTICIPANTS | CONTROL PARTICIPANTS | MESSAGE CONTENT AND FREQUENCY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge drinking episodes—short-term intervention | |||||||||

| Crombie et al.22 | 2017 | RCT | United Kingdom | Obese young adults and adults | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 31 | 30 | A series of tailored text messages, multiple in a week |

| Gajecki et al.7,a | 2014 | RCT | Sweden | University students | 7 Weeks | Mobile app-based, semitailored | 153 | 489 | Mobile app-based information texts on risky eBAC levels and strategies to avoid risky drinking behavior |

| Gajecki et al.7,a | 2014 | RCT | Sweden | University students | 7 Weeks | Mobile app-based, semitailored | 153 | 489 | Same as above |

| Haug et al.15,a | 2013 | Pre–post | Switzerland | Vocational and upper secondary students | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 278 | 278 | Three risk categories identified, non (encourage abstinence), low high, tailored messages |

| Haug et al.15,a | 2013 | Pre–post | Switzerland | Vocational and upper secondary students | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 280 | 280 | Same as above |

| Masonet al.9 | 2014 | RCT | United States | College Students | 6 Weeks | Text message tailored | 8 | 10 | Personalized computer-generated text messages, four to six messages daily |

| Suffoletto et al.23 | 2015 | RCT | United States | Adolescent and young adult population | 12 Weeks | Text message, tailored | 290 | 148 | Tailored text messages, twice per week. Content varied according to patient reply to queries on drink plans and amount was taken |

| Mean drinks per occasion—short-term intervention | |||||||||

| Crombie et al.22 | 2017 | RCT | United Kingdom | Obese young adult and adult | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 31 | 30 | A series of tailored text messages, multiple in a week |

| Mason et al.9 | 2014 | RCT | United States | College students | 6 Weeks | Text message tailored | 8 | 10 | Personalized computer-generated text messages, four to six messages daily |

| Suffolettoet al.24 | 2012 | RCT | United States | Young adults | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 14 | 13 | Two-way messages tailored for number of drinks and goal setting |

| Suffoletto et al.23 | 2015 | RCT | United States | Adolescent and young adult population | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 234 | 126 | Tailored text messages, twice per week. Content varied according to patient reply to queries on drink plans and amount was taken |

| Standard glasses per week—short-term intervention | |||||||||

| Crombie et al.22 | 2017 | RCT | United Kingdom | Obese adult population | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 31 | 30 | A series of tailored text messages, multiple in a week |

| Gajecki et al.7,a | 2014 | RCT | Sweden | University students | 7 Weeks | Mobile app-based, semi tailored | 153 | 489 | Mobile app-based information texts on risky eBAC levels and strategies to avoid risky drinking behavior |

| Gajecki et al.7,a | 2014 | RCT | Sweden | University students | 7 Weeks | Mobile app-based, semitailored | 341 | 489 | Same as above |

| Haug et al.15 | 2013 | Pre–post | Switzerland | Vocational and upper secondary students | 12 Weeks | Text message tailored | 247 | 79 | Three risk categories identified, non (encourage abstinence), low high, tailored messages |

| Binge drinking episodes—long-term intervention (6 months) | |||||||||

| Haug et al. 25,a | 2017 | RCT | Switzerland | Vocational and upper secondary students | 6 Months outcome | Text message tailored | 547 | 494 | Content and frequency 1/week, 2/week, 2+ optional service, tailored on three risk groups with encouraging messages for not drinking, or soft drinks or talking friend offer |

| Haug et al.25,a | 2017 | RCT | Switzerland | Vocational and upper secondary students | 6 Months outcome | Text message tailored | 547 | 494 | Same as above |

| Suffoletto et al.23 | 2015 | RCT | United States | Adolescent and young adult population | 6 Months outcome | Text message tailored | 234 | 126 | Tailored text messages, twice per week. Content varied according to patient reply to queries on drink plans and amount was taken |

| Binge drinking episodes—long-term intervention (9 months) | |||||||||

| Suffoletto et al.23 | 2015 | RCT | United States | Adolescent and young adult population | 9 Months outcome | Text message tailored | 199 | 112 | Tailored text messages, twice per week. Content varied according to patient reply to queries on drink plans and amount was taken |

Two qualifying datasets used for the same forest plot.

eBAC, estimated Blood Alcohol Concentration; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

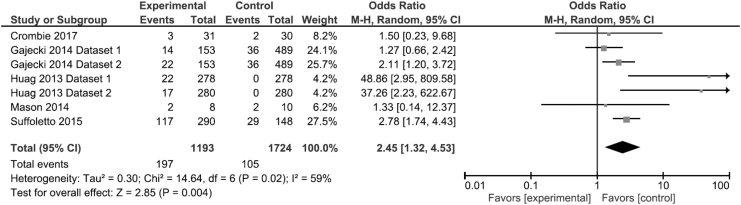

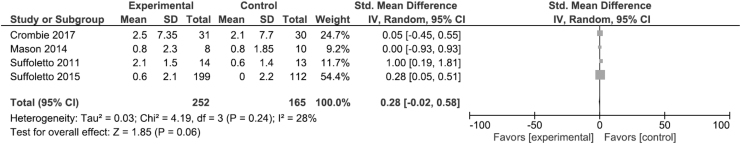

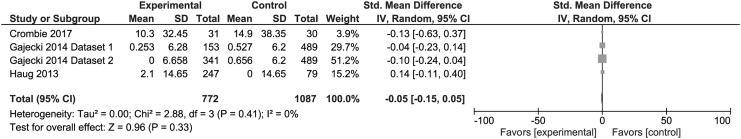

The analysis of short-term interventions was divided into three categories: (1) binge drinking episodes, (2) mean drinks per occasion, and (3) standard glasses per week. Forest plot analysis showed reduction in binge drinking episodes in the control group without the intervention (OR = 2.45 [1.32–4.53], I2 = 59%, χ2 = 14.64) (Fig. 2), suggesting that mobile phone-based text messaging was not effective to lower binge drinking, with possibilities of opposite effect. Forest plot analysis on the effect of short-term interventions using mobile phone-based text messaging on the mean drinks per occasion favored neither group (standard mean difference = 0.28 [−0.02 to 0.58], I2 = 28%, χ2 = 4.19) (Fig. 3), also suggesting that the text message had negligible impact on the experimental group. Similarly, forest plot analysis on the effect of short-term interventions using mobile phone-based text messaging on the reduction in average standard glasses per week favored neither group (standard mean difference = −0.05 (−0.15 to 0.05), I2 = 0%, χ2 = 2.88) (Fig. 4), further suggesting that the text messages had a negligible impact.

Fig. 2.

Effectiveness of mobile phone-based text messaging on binge drinking for short-term interventions.

Fig. 3.

Effectiveness of mobile phone-based text messaging and mean reductions in drink per occasion from baseline for short-term interventions.

Fig. 4.

Effectiveness of mobile phone-based text messaging and average standard glasses per week reductions from baseline for short-term interventions.

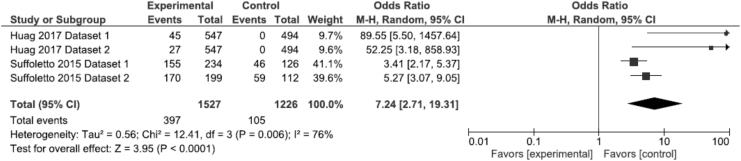

Only three studies on 6 months' intervention and only one study on 9 months intervention meet inclusion criteria (Table 2), which were used together for the effects of long-term analysis. Forest plot analysis on the effect of long-term interventions using mobile phone-based text messaging to reduce binge drinking had results that were similar to the short-term interventions. The analysis favored the control groups over the experimental groups (OR = 7.24 [2.71–19.31], I2 = 76%, χ2 = 12.41) (Fig. 5), suggesting text-based messages had either none or possible opposite effect on problem drinking.

Fig. 5.

Effectiveness of mobile phone-based text messaging on alcohol consumption on binge drinking events reduction from baseline for long-term interventions.

Discussion

Remarkably, the findings suggested that the texting interventions designed to reduce problem drinking may have no or opposite effects, making problem drinking worse. Although most studies favored controls, overall there were no statistically significant differences to definitively support messaging's negative impacts, except, perhaps, in the case of binge drinking. Substantial benefits of mobile phone-based text message interventions on alcohol behavior were not found. Although not necessarily a study limitation, one issue with the meta-analysis is the small number of rigorous studies that have been published about mobile phone-based text message interventions in alcohol-related disorders, on which it is based. Also, the text message content, frequency, and tailored messages varied widely among the included studies. As reported in one study, the use of text messages in conjunction with web-based intervention with alcohol problems could have been more effective than messaging alone.19 Excessive use of smartphones or problematic smartphone use in young adults is increasingly recognized as a mental health problem. Ironically, using the very same mobile device as a tool to intervene problem drinking with text messages may contribute to this excessive use.16

Limitations

Although all of the studies included were done using adolescents and younger adults, two of the studies also included young outpatient populations discharged from the emergency department, which might have represented some variation in the study population regarding the level of morbidity of the alcohol problem. The results generated by this analysis were intuitively contrary to some of the published conclusions on the positive effects of messaging systems on younger adult and adolescent populations. The high heterogeneity noted in Figure 5 could be related to either diversity in the population included in the studies or the use of random effects rather than fixed effects in doing the statistical analysis.

Conclusions

Findings of the meta-analysis showed that mobile phone-based text messaging was not effective in reducing binge drinking with both short-term and long-term interventions, or in reducing average drinks per occasion and standard drinks per occasion in short-term interventions. More rigorous studies need to be conducted to provide stronger evidence for mobile text messaging effects on the alcohol habits of younger people and to determine whether the messages have possible negative effects.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Library of Medicine (NLM), and Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications (LHNCBC).

Disclaimer

The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. NIAAA. Alcol Facts and Statistics | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). 2018. Available at https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-facts-and-statistics (last accessed January28, 2019).

- 2. Windle M. Alcohol use among adolescents and young. 2003. Available at https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh27-1/79-86.htm (accessed January28, 2019) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Swendsen J, Burstein M, Case B, Conway KP, Dierker L, He J, Merikangas KR. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:390–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. White A, Hingson R. The burden of alcohol use: Excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res 2013;35:201–218 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crews FT, Vetreno RP, Broadwater MA, Robinson DL. Adolescent alcohol exposure persistently impacts adult neurobiology and behavior. Pharmacol Rev 2016;68:1074–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NIAAA. Alcohol Use Disorder | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). 2018. Available at https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-use-disorders (last accessed January28, 2019).

- 7. Gajecki M, Berman AH, Sinadinovic K, Rosendahl I, Andersson C. Mobile phone brief intervention applications for risky alcohol use among university students: A randomized controlled study. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2014;9:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moore SC, Crompton K, van Goozen S, van den Bree M, Bunney J, Lydall E. A feasibility study of short message service text messaging as a surveillance tool for alcohol consumption and vehicle for interventions in university students. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mason M, Benotsch EG, Way T, Kim H, Snipes D. Text messaging to increase readiness to change alcohol use in college students. J Prim Prev 2014;35:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lucht MJ, Hoffman L, Haug S, Meyer C, Pussehl D, Quellmalz A, Klauer T, Grabe HJ, Freyberger HJ, John U, Schomerus G. A surveillance tool using mobile phone short message service to reduce alcohol consumption among alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014;38:1728–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agyapong VIO, McLoughlin DM, Farren CK. Six-months outcomes of a randomised trial of supportive text messaging for depression and comorbid alcohol use disorder. J Affect Disord 2013;151:100–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stoner SA, Arenella PB, Hendershot CS. Randomized controlled trial of a mobile phone intervention for improving adherence to naltrexone for alcohol use disorders. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Witkiewitz K, Desai SA, Bowen S, Leigh BC, Kirouac M, Larimer ME. Development and evaluation of a mobile intervention for heavy drinking and smoking among college students. Psychol Addict Behav 2014;28:639–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haug S, Lucht MJ, John U, Meyer C, Schaub MP. A pilot study on the feasibility and acceptability of a text message-based aftercare treatment programme among alcohol outpatients. Alcohol Alcohol 2015;50:188–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haug S, Schaub MP, Venzin V, Meyer C, John U, Gmel G. A pre-post study on the appropriateness and effectiveness of a Web- and text messaging-based intervention to reduce problem drinking in emerging adults. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wolniewicz CA, Tiamiyu MF, Weeks JW, Elhai JD. Problematic smartphone use and relations with negative affect, fear of missing out, and fear of negative and positive evaluation. Psychiatry Res 2018;262:618–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cochrane. Chapter 8: Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. Available at https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/8_assessing_risk_of_bias_in_included_studies.htm (last accessed January28, 2019)

- 18. Cochrane. 9.5.4 Incorporating heterogeneity into random-effects models. Available at https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_9/9_5_4_incorporating_heterogeneity_into_random_effects_models.htm (last accessed January28, 2019)

- 19. Tahaney KD, Palfai TP. Text messaging as an adjunct to a web-based intervention for college student alcohol use: A preliminary study. Addict Behav 2017;73:63–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. PRISMA PRISMA. 2009. Checklist. Available at http://prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA%202009%20checklist.pdf (last accessed January28, 2019)

- 21. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Appendix 9.Alcohol. Available at https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/appendix-9/ (last accessed January28, 2019)

- 22. Crombie IK, Cunningham KB, Irvine L, Williams B, Sniehotta FF, Norrie J, Melson A, Jones C, Briggs A, Rice PM, Achison M, McKenzie A, Dimova E, Slane PW. Modifying Alcohol Consumption to Reduce Obesity (MACRO): Development and feasibility trial of a complex community-based intervention for men. Health Technol Assess 2017;21:1–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suffoletto B, Kristan J, Chung T, Jeong K, Fabio A, Monti P, Clark DB. An interactive text message intervention to reduce binge drinking in young adults: A randomized controlled trial with 9-month outcomes. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suffoletto B, Callaway C, Kristan J, Kraemer K, Clark DB. Text-message-based drinking assessments and brief interventions for young adults discharged from the emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2012;36:552–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haug S, Paz Castro R, Kowatsch T, Filler A, Dey M, Schaub MP. Efficacy of a web- and text messaging-based intervention to reduce problem drinking in adolescents: Results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]