Abstract

Objective

To determine the association between total gestational weight gain and perinatal outcomes.

Study Design

Data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-To-Be (NuMoM2b) study were used. Total gestational weight gain was categorized as inadequate, adequate, or excessive based on the 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines. Outcomes examined included hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, mode of delivery, shoulder dystocia, large for gestational age or small for-gestational age birth weight, and neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Results

Among 8,628 women, 1,666 (19.3%) had inadequate, 2,945 (34.1%) had adequate, and 4,017 (46.6%) had excessive gestational weight gain. Excessive gestational weight gain was associated with higher odds of hypertensive disorders (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.78–2.36) Cesarean delivery (aOR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.09–1.41), and large for gestational age birth weight (aOR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.23–1.80), but lower odds of small for gestational age birth weight (aOR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.50–0.71). Conversely, inadequate gestational weight gain was associated with lower odds of hypertensive disorders (aOR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.62–0.92), Cesarean delivery (aOR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.65–0.92), and a large for gestational age birth weight (aOR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.55–0.94), but higher odds of having a small for gestational age birth weight (aOR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.37–1.96).

Conclusion

Both excessive and inadequate gestational weight gain are associated with adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Keywords: gestational weight gain, cesarean delivery, small for gestational age birth weight, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, large for gestational age birth weight

Excessive gestational weight gain during pregnancy is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, including Cesarean delivery,1 gestational diabetes,2 and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.3 Inadequate weight gain is also associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, including an increased risk of a small for gestational age (SGA) birth weight4 and preterm delivery.5 Excessive gestational weight gain during pregnancy has also been associated with long-term consequences for both maternal and child health, such as increased risks of maternal6 and childhood obesity.7

While there are considerable data available regarding gestational weight gain and obstetric outcomes, most previous studies are limited to a single site, have small sample sizes, or lack diversity among their patient population.1,4,8,9 Some studies focused only on women who were already obese, prior to pregnancy.10,11 Furthermore, among multiparous women, personal obstetric history is highly predictive of subsequent pregnancy outcomes, such as cesarean delivery and hypertensive disorders,12,13 and represents a significant confounder when studying the associations between gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes among women of mixed parity. Finally, larger studies that have been performed are mainly derived from retrospectively collected data,5,14 and mostly use administrative15 data, which is more likely to lead to inaccurately ascertained exposures and outcomes.16

The goal of this study was to use prospectively collected data from a geographically, racially, and ethnically diverse large population of nulliparous women to examine the association of gestational weight gain with maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This was a secondary analysis of the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-To-Be (NuMoM2b) study. NuMoM2b is a prospective cohort study in which nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies were enrolled from U.S. hospitals located in eight geographically diverse regions. Women were eligible for enrollment if they had a viable singleton pregnancy at the time of enrollment (between 60/7 and 136/7 weeks’ gestation) and no previous pregnancy that progressed beyond 20 weeks’ gestation. Exclusion criteria included maternal age younger than 13 years, history of three of more spontaneous abortions, current pregnancy complicated by suspected major fetal malformation or known fetal aneuploidy, assisted reproduction with a donor oocyte, multifetal reduction, or plan to terminate the pregnancy. Women were further excluded if they were already participating in an intervention study anticipated to influence pertinent maternal or fetal outcomes were previously enrolled in this study, or patients were unable to provide informed consent. Each site’s local governing institutional review board approved the study and all women provided written informed consent prior to participation. Specifically, at Northwestern University, the affiliation of the primary author of this paper, protocol number STU00030933 was approved on October 1,2010. Full details of the study protocol are published elsewhere.17

Women were eligible for this secondary analysis if they had a height and weight recorded at the first study visit, had a live-born singleton infant between 24 and 43 weeks’ gestation, and a “final” weight measured within 4 weeks of delivery. Women with extreme weight gain (>100 pounds) or loss (>50 pounds) were excluded a priori from this analysis as these values were significantly more likely to be biologically implausible (an approach taken by Beyerlein et al18).

The main exposure variable of gestational weight gain was calculated (in the primary analysis) as the total weight change in pounds, derived using the final weight measured minus, the weight measured at the first study visit (between 6 0/7 and 13 6/7 weeks’ gestation). We chose to use the initial study visit weight, as opposed to prepregnancy reported weight, to calculate our primary measure of gestational weight gain, as the use of only measured weights provides a more objective assessment. We further categorized gestational weight gain according to the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) 2009 guidelines.19 Weight change was categorized as inadequate (below), adequate (within), or excessive (above) based on body mass index (BMI; (calculated from height and weight measurements) at the first-trimester visit (28–40 pounds for BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, 25–35 pounds for BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, 15–25 pounds for BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and 11–20 pounds for BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

We examined several outcome variables selected a priori for this analysis. Women were considered to have a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy if they had new-onset antepartum gestational hypertension, or antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum preeclampsia, eclampsia, superimposed preeclampsia or hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low-platelets (HELLP) syndrome diagnosed from 20 weeks’ gestation onwards. To define the occurrence of these conditions, we used the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG’s) Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy definitions of hypertensive disease.20 We chose to analyze all hypertensive disorders as a single outcome, rather than separate them into constituent parts, as clinically, they are managed similarly, and analyzing each separately would introduce the possibility of multiple comparisons.

We also determined whether gestational weight gain was associated with Cesarean delivery among women who had labored. We did not assess gestational diabetes mellitus as an outcome given that it typically is diagnosed in midpregnancy and much gestational weight gain accrues after its diagnosis. Using a similar rationale, we elected not to study preterm delivery, in part because gestational weight gain accrues throughout pregnancy and in part because some of the other outcomes (such as hypertensive disorders) may be on the causal pathway. Neonatal outcomes assessed included SGA or large for gestational age (LGA) birth weight,21 or a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission. Also, we determined whether gestational weight gain was associated with shoulder dystocia for infants who delivered vaginally.

In multivariable analyses, we adjusted for several potential confounders, including maternal age (years), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, and other), maternal education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, associate or technical degree, completed college, or more than college), insurance (private, government or military, uninsured, or other), marital status (married or unmarried), gestational age at delivery (weeks), smoked within 3 months of pregnancy or during pregnancy, pregestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, any mental health condition, and—when appropriate—initial BMI category (underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese).

We performed three sensitivity analyses using different approaches to classification of gestational weight gain. First, when prepregnancy weight was available, we used this measure, instead of measured first-trimester weight, to calculate gestational weight gain. In a second sensitivity analysis, we categorized gestational weight gain according to the weight change per week in the second and third trimesters based on the IOM standard for the appropriate rate of change (1–1.3 pounds per week for BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, 0.8–1.0 pounds per week for BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, 0.5–0.7 pounds per week for BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and 0.4–0.6 pounds per week for BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). This analysis incorporated an assumption of a weight gain of 4.4 pounds in the first trimester for all women. Finally, we limited our sample to women who had a delivery at 37 weeks’ gestational age or greater.

For bivariable analyses, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; when the continuous variable approximated a normal distribution) and Kruskal–Wallis tests (when the continuous variable was not normally distributed) for comparison of continuous variables and Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests (when any cell included ≤5 respondents) for comparison of categorical variables. We used logistic regression for multivariable analyses for all outcomes which were stratified by BMI category at the first study visit. We adjusted for hospital of delivery as a fixed effect in all models. All analyses were performed in STATA release 15.0 (StataSoft Corp., College Station, TX). All statistical tests were two-tailed and considered significant at the p < 0.05 level.

Results

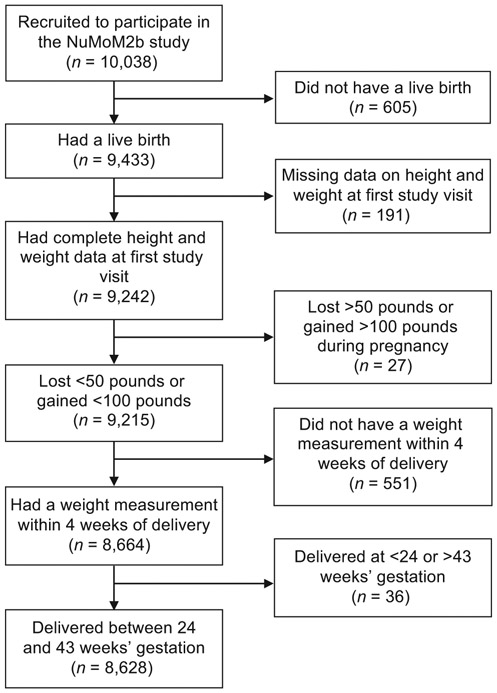

Among 10,038 women in the NuMom2b study, 605 did not have a live birth and were excluded from the analytic sample, as were 191 women missing BMI data on initial study visit. An additional 27 women who had implausible gestational weight gain values, 551 women who did not have a weight within 4 weeks of delivery, and 36 women who delivered prior to 24 weeks’ or after 43 weeks’ gestational age, also were excluded from the study population, leaving 8,628 women for our analysis (►Fig. 1). Of these 8,628 women, 191 (2.2%) were underweight at their first study visit, 4,400 (51.0%) were normal weight, 2,135 (24.8%) were overweight, and 1,902 (22.0%) were obese. Also, 1,666 (19.3%) had inadequate weight gain, 2,945 (34.1%) had adequate weight gain, and 4,017 (46.6%) had excessive weight gain. The amount of weight gain was significantly associated with maternal age, race, ethnicity, education, insurance source, marital status, smoking within 3 months of pregnancy, BMI at first-study visit category, and gestational age at delivery (►Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Study sample. NuMoM2b, Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-To-Be study.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Variable | Overall cohort (n = 8,628)a |

Inadequate weight gain (n = 1,666) |

Adequate weight gain (n = 2,945) |

Excessive weight gain (n = 4,017) |

p-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.1 ± 5.6 | 27.1 ± 6.0 | 27.5 ± 5.6 | 26.7 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| < 18 | 208 (2.4) | 53 (3.2) | 58 (2.0) | 97 (2.4) | |

| 18–34 | 7,614 (88.3) | 1,432 (86.0) | 2,584 (87.7) | 3,598 (89.6) | |

| 35–39 | 686 (8.0) | 151 (9.1) | 253 (8.6) | 282 (7.0) | |

| ≥ 40 | 120 (1.4) | 30 (1.8) | 50 (1.7) | 40 (1.0) | |

| Race and ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 5,328 (61.8) | 933 (56.0) | 1,874 (63.6) | 2,521 (62.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1,157 (13.4) | 269 (16.2) | 327 (11.1) | 561 (14.0) | |

| Hispanic | 1,361 (15.8) | 286 (17.2) | 454 (15.4) | 621 (15.5) | |

| Asian | 342 (4.0) | 106 (6.4) | 143 (4.9) | 93 (2.3) | |

| Other | 440 (5.1) | 72 (4.3) | 147 (5.0) | 221 (5.5) | |

| Maternal education | <0.001 | ||||

| Less than high school | 683 (7.9) | 176 (10.6) | 170 (5.8) | 337 (8.4) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 972 (11.3) | 174 (10.4) | 292 (9.9) | 506 (12.6) | |

| Some college | 1,614 (18.7) | 293 (17.6) | 533 (18.1) | 788 (19.6) | |

| Associate or technical degree | 857 (9.9) | 156 (9.4) | 273 (9.3) | 428 (10.7) | |

| Completed college | 2,441 (28.3) | 429 (25.8) | 898 (30.5) | 1,114 (27.7) | |

| More than college | 2,061 (23.9) | 438 (26.3) | 779 (26.5) | 844 (21.0) | |

| Insurance | <0.001 | ||||

| Private | 5,866 (68.4) | 1,097 (66.3) | 2,099 (71.6) | 2,670 (67.0) | |

| Government or military | 2,392 (27.9) | 499 (30.2) | 715 (24.4) | 1,178 (29.6) | |

| Uninsured | 229 (2.7) | 39 (2.4) | 81 (2.8) | 109 (2.7) | |

| Other | 85 (1.0) | 20 (1.2) | 36 (1.2) | 29 (0.7) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||

| Unmarried | 3,358 (38.9) | 662 (39.8) | 1,021 (34.7) | 1,675 (41.7) | |

| Married | 5,266 (61.1) | 1,003 (60.2) | 1,923 (65.3) | 2,340 (58.3) | |

| Smoked within 3 months of pregnancy | 1,525 (17.7) | 270 (16.2) | 429 (14.6) | 826 (20.6) | <0.001 |

| Pregestational diabetes | 138 (1.6) | 29 (1.7) | 44 (1.5) | 65 (1.6) | 0.81 |

| Chronic hypertension | 274 (3.3) | 52 (3.2) | 97 (3.4) | 125 (3.2) | 0.91 |

| Any mental health condition | 1,261 (14.7) | 240 (14.5) | 405 (13.8) | 616 (15.4) | 0.17 |

| Prepregnancy weight (category) | <0.001 | ||||

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) | 191 (2.2) | 90 (5.4) | 77 (2.6) | 24 (0.6) | |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 4,400 (51.0) | 1,145 (68.7) | 1,934 (65.7) | 1,321 (32.9) | |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 2,135 (24.8) | 157 (9.4) | 539 (18.3) | 1,439 (35.8) | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 1,902 (22.0) | 274 (16.5) | 395 (13.4) | 1,233 (30.7) | |

| Weight change (pounds) | 29.8 ± 12.6 | 14.8 ± 10.1 | 26.5 ± 6.2 | 38.4 ± 9.7 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age at first visit (wk) | 12 (11–13) | 12 (11–13) | 12 (11–13) | 12 (11–13) | 0.11 |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 39 (38–40) | 39 (38–40) | 39 (38–40) | 39 (38–40) | <0.001 |

| Fetal sex | 0.22 | ||||

| Male | 4,422 (51.3) | 823 (49.4) | 1,502 (51.0) | 2,097 (52.2) | |

| Female | 4,202 (48.7) | 842 (50.6) | 1,441 (49.0) | 1,919 (47.8) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GED, graduate education degree.

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range), or n (%). Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

p-Value is for Chi-square tests for categorical variables, t-tests for all continuous variables except for gestational age at first visit and delivery, and Kruskal–Wallis tests for gestational age at first visit and delivery.

►Table 2 shows bivariable associations between gestational weight gain and outcomes, for the overall cohort and after stratification by BMI category at the first study visit, while ►Table 3 shows results of the multivariable regression models for the primary measure of gestational weight gain (i.e., using measured weight at the first-study visit), as well as for the sensitivity analyses. Excessive gestational weight gain was associated with an increased frequency of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy for women in all BMI categories (p < 0.001 for the overall cohort, as well as for each BMI category). This association held for all women in multivariable models (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.78–2.36). Excessive gestational weight gain also was associated with increased odds of undergoing a Cesarean following labor (aOR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.09–1.41).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for maternal and neonatal outcomes by baseline body mass index category

| Variable | Overall cohort (n = 8,628)a |

Inadequate weight gain (n = 1,666) |

Adequate weight gain (n = 2,945) |

Excessive weight gain (n = 4,017) |

p-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | |||||

| Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | |||||

| Overall cohort | 1,657 (19.2) | 200 (12.0) | 402 (13.7) | 1,055 (26.3) | < 0.001 |

| Underweight | 20 (10.5) | 4 (4.4) | 7 (9.2) | 9 (37.5) | < 0.001 |

| Normal weight | 590 (13.4) | 112 (9.8) | 207 (10.7) | 271 (20.5) | < 0.001 |

| Overweight | 459 (21.5) | 26 (16.6) | 89 (16.5) | 344 (23.9) | < 0.001 |

| Obese | 588 (31.0) | 58 (21.2) | 99 (25.1) | 431 (35.0) | < 0.001 |

| Cesarean deliveryc | |||||

| Overall cohort | 1,827 (22.7) | 248 (16.0) | 542 (19.6) | 1,037 (27.6) | < 0.001 |

| Underweight | 20 (10.9) | 11 (12.9) | 8 (10.7) | 1 (4.2) | 0.58 |

| Normal weight | 672 (16.1) | 141 (13.1) | 291 (15.9) | 240 (19.1) | < 0.001 |

| Overweight | 509 (25.8) | 25 (17.9) | 115 (23.1) | 369 (27.6) | 0.01 |

| Obese | 626 (36.0) | 71 (29.2) | 128 (36.0) | 427 (37.5) | 0.05 |

| Neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Shoulder dystociad | |||||

| Overall cohort | 161 (2.6) | 19 (1.5) | 39 (1.8) | 103 (3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Underweight | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Normal weight | 53 (1.5) | 8 (0.9) | 21 (1.4) | 24 (2.4) | 0.02 |

| Overweight | 48 (3.3) | 2 (1.7) | 8 (2.1) | 38 (3.9) | 0.17 |

| Obese | 59 (5.3) | 8 (4.7) | 10 (4.4) | 41 (5.8) | 0.71 |

| Small for gestational age birth weight | |||||

| Overall cohort | 914 (10.6) | 302 (18.2) | 325 (11.1) | 287 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Underweight | 36 (18.9) | 22 (24.4) | 12 (15.6) | 2 (8.3) | 0.14 |

| Normal weight | 483 (11.0) | 203 (17.8) | 197 (10.2) | 83 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Overweight | 218 (10.2) | 40 (25.5) | 70 (13.0) | 108 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Obese | 177 (9.3) | 37 (13.7) | 46 (11.7) | 94 (7.6) | 0.002 |

| Large for gestational age birth weight | |||||

| Overall cohort | 761 (8.8) | 91 (5.5) | 221 (7.5) | 449 (11.2) | < 0.001 |

| Underweight | 9 (4.7) | 5 (5.6) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (12.5) | 0.06 |

| Normal weight | 337 (7.7) | 58 (5.1) | 143 (7.4) | 136 (10.3) | < 0.001 |

| Overweight | 187 (8.8) | 5 (3.2) | 39 (7.2) | 143 (9.9) | 0.004 |

| Obese | 228 (12.0) | 23 (8.4) | 38 (9.6) | 167 (13.5) | 0.02 |

| NICU admission | |||||

| Overall cohort | 1,239 (14.4) | 264 (15.9) | 401 (13.6) | 574 (14.3) | 0.11 |

| Underweight | 20 (10.5) | 11 (12.2) | 6 (7.8) | 3 (12.5) | 0.61 |

| Normal weight | 533 (12.1) | 163 (14.3) | 226 (11.7) | 144 (10.9) | 0.03 |

| Overweight | 321 (15.0) | 27 (17.2) | 95 (17.6) | 199 (13.8) | 0.08 |

| Obese | 365 (19.2) | 63 (23.0) | 74 (18.8) | 228 (18.5) | 0.23 |

Abbreviation: NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Data presented as n (%). Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

p-Value is for chi square tests or Fisher’s exact tests (for analyses where any cell has ≤5 women).

Among women who underwent labor (n = 8,076).

Among women who underwent vaginal delivery (n = 6,277).

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses for maternal and neonatal outcomes

| Outcome | Inadequate weight gain (n = 1,666) |

Adequate weight gain (n = 2,945) |

Excessive weight gain (n = 4,017) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | |||

| Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | |||

| Unadjusted OR | 0.86 (0.72–1.03) | (Ref) | 2.25 (1.99–2.56) |

| Adjusted ORa | 0.75 (0.62–0.92) | (Ref) | 2.05 (1.78–2.36) |

| Using prepregnancy weight (adjusted) | 0.75 (0.60–0.93) | (Ref) | 1.72 (1.48–2.00) |

| Using weekly mean weight gain (adjusted) | 0.87 (0.67–1.13) | (Ref) | 1.91 (1.51–2.41) |

| Term deliveries only (adjusted)b | 0.76 (0.61–0.94) | (Ref) | 1.99 (1.71–2.31) |

| Cesarean delivery following laborc | |||

| Unadjusted OR | 0.78 (0.66–0.92) | (Ref) | 1.56 (1.39–1.76) |

| Adjusted ORa | 0.77 (0.65–0.92) | (Ref) | 1.24 (1.09–1.41) |

| Using prepregnancy weight (adjusted) | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) | (Ref) | 1.33 (1.16–1.54) |

| Using weekly mean weight gain (adjusted) | 0.72 (0.58–0.90) | (Ref) | 1.07 (0.88–1.31) |

| Term deliveries only (adjusted) | 0.75 (0.62–0.90) | (Ref) | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) |

| Neonatal outcomes | |||

| Shoulder dystociad | |||

| Unadjusted OR | 0.83 (0.48–1.45) | (Ref) | 2.20 (1.52–3.20) |

| Adjusted ORa | 0.80 (0.45–1.41) | (Ref) | 1.68 (1.12–2.52) |

| Using prepregnancy weight (adjusted) | 1.09 (0.56–2.11) | (Ref) | 2.01 (1.24–3.26) |

| Using weekly mean weight gain (adjusted) | 0.96 (0.43–2.13) | (Ref) | 1.62 (0.78–3.40) |

| Term deliveries only (adjusted) | 0.77 (0.43–1.38) | (Ref) | 1.63 (1.09–2.44) |

| Small for gestational age birth weight | |||

| Unadjusted OR | 1.79 (1.51–2.12) | (Ref) | 0.62 (0.52–0.73) |

| Adjusted ORa | 1.64 (1.37–1.96) | (Ref) | 0.59 (0.50–0.71) |

| Using prepregnancy weight (adjusted) | 1.53 (1.26–1.87) | (Ref) | 0.56 (0.47–0.67) |

| Using weekly mean weight gain (adjusted) | 1.37 (1.08–1.73) | (Ref) | 0.62 (0.49–0.78) |

| Term deliveries only (adjusted) | 1.64 (1.35–1.99) | (Ref) | 0.57 (0.47–0.69) |

| Large for gestational age birth weight | |||

| Unadjusted OR | 0.71 (0.55–0.92) | (Ref) | 1.55 (1.31–1.84) |

| Adjusted ORa | 0.72 (0.55–0.94) | (Ref) | 1.49 (1.23–1.80) |

| Using prepregnancy weight (adjusted) | 0.78 (0.57–1.05) | (Ref) | 1.48 (1.20–1.81) |

| Using weekly mean weight gain (adjusted) | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | (Ref) | 1.34 (1.01–1.79) |

| Term deliveries only (adjusted) | 0.73 (0.56–0.96) | (Ref) | 1.43 (1.18–1.73) |

| NICU admission | |||

| Unadjusted OR | 1.20 (1.01–1.41) | (Ref) | 1.06 (0.92–1.21) |

| Adjusted ORa | 1.16 (0.98–1.39) | (Ref) | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) |

| Using prepregnancy weight (adjusted) | 1.15 (0.94–1.42) | (Ref) | 1.12 (0.96–1.32) |

| Using weekly mean weight gain (adjusted) | 1.04 (0.81–1.33) | (Ref) | 1.23 (0.98–1.55) |

| Term deliveries only (adjusted) | 0.83 (0.66–1.05) | (Ref) | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; NICU neonatal intensive care unit.

All adjusted regressions adjusted for maternal age, race, ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, insurance, smoking within 3 months of pregnancy, gestational age at delivery, pregestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, any mental health diagnosis, body mass index category at first study visit, and hospital of delivery.

Among women who had a term delivery (n = 7,923).

Among women who underwent labor (n = 8,076 for all women, n = 7,484 for women who had a term delivery). The reference category for the odds ratios is any vaginal delivery (spontaneous or operative).

Among women who underwent vaginal delivery (n = 6,277 for all women, n = 5,812 for women who had a term delivery).

Excessive gestational weight gain was associated with higher odds of shoulder dystocia (aOR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.12–2.52) and LGA birth weight (aOR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.23–1.80), while inadequate gestational weight gain was associated with higher odds of SGA birth weight (aOR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.37–1.96). Conversely, excessive gestational weight gain was associated with lower odds of SGA birth weight (aOR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.50–0.71) and inadequate gestational weight gain was associated with lower odds of an LGA birth weight (aOR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.55–0.94). There was no association between gestational weight gain and NICU admission in the multivariable models.

►Table 3 also shows that in the sensitivity analysis, when alternate approaches to categorizing the adequacy of gestational weight gain were used, the point estimates for the association between gestational weight gain and the outcomes did not substantively change in direction or magnitude, although in some cases, associations that previously were statistically significant, no longer were statistically significant due to confidence intervals that overlapped unity. Results also did not change substantively when limiting our sample to the 7,923 women who had term deliveries.

Discussion

Both excessive and inadequate gestational weight gain based on the IOM’s 2009 guidelines are associated with increased odds of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes among nulliparous women, and the risks are different for excessive versus inadequate gestational weight gain. Excessive gestational weight gain was associated with increased odds of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, LGA birth weight, shoulder dystocia, and Cesarean delivery. Conversely, inadequate gestational weight gain was associated with lower odds of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, Cesarean delivery, and LGA birth weight but was associated with higher odds for SGA birth weight. Importantly, the increased odds of these outcomes associated with gestational weight gain is above and beyond the increased odds associated with prepregnancy BMI alone, which also has a positive association with hypertensive disorders,22 Cesarean delivery,23 and LGA birth weight.24

These results are largely comparable to those from other studies.5,25-27 There has been little previous research regarding the role of gestational weight gain and hypertensive disorders, in part due to difficulty discerning whether gestational weight gain precedes or occurs concurrently with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.20 We show increased odds of a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy with excessive gestational weight gain regardless of the BMI category of the first-study visit which also was observed in one other study.28 It remains unclear whether the increased gestational weight gain is the result of, rather than a preceding risk for a hypertensive disorder, although recent studies examining the temporality of the gestational weight gain to the onset of hypertensive disorders suggest that the weight gain precedes the onset of overt hypertension.29

We demonstrate that excessive gestational weight gain is common, as nearly half of women had gestational weight gain that exceeded IOM recommendations. This finding is consistent with prior studies, in which between 40 and 73% of women gained excessive weight.4,5,25,26 Our results are also consistent with estimates of inadequate gestational weight gain, which occurs in 10 to 30% of women.25

Gestational weight gain represents a potentially modifiable risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Many reports elucidated risk factors for inappropriate (excessive or inadequate) gestational weight gain, including prepregnancy BMI,30 race or ethnicity,31 and socioeconomic status.32 Several studies have also considered interventions in an effort to optimize gestational weight gain, including dietary counseling,33 exercise,34 or both of these,35 although there has not been clear demonstration that such interventions are easy to implement in typical settings or can lead to better pregnancy outcomes. Provider advice regarding gestational weight gain may have a positive effect on helping women to achieve appropriate gestational weight gain, but this advice is often not forthcoming, inconsistently provided, or inaccurate.36 Other studies show that some seemingly beneficial interventions for pregnancy, such as group prenatal care, are associated with excessive gestational weight gain.37 The determination of the best approaches to optimize weight gain, and an understanding of whether these approaches can also improve pregnancy outcomes, represents an important area for future research.

This analysis has several strengths. It utilizes a geographically, racially, and ethnically diverse cohort, contains detailed information on gestational weight gain and potential confounding variables that were prospectively collected, and has outcome data that were abstracted by trained research personnel according to a priori definitions. This analysis also has limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there is a chance that NuMom2b study participants may not represent the overall obstetric population of nulliparous women, and therefore the results are not fully generalizable. Second, although we adjusted for multiple potential covariates there may be other unknown confounding variables for which we did not account for in these models, including effects of gestational age that are not entirely a linear function.38 Finally, as this is an observational study, causality cannot be inferred.

Conclusion

In conclusion, among this diverse population of nulliparous women, gestational weight gain—regardless of BMI at the first study visit—is associated with several adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Further study is warranted regarding determining which interventions can assist nulliparous pregnant women in meeting their gestational weight gain goals during pregnancy, and to understand whether these interventions will improve maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Support for the NuMoM2b study was provided by grant funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: U10 HD063036, RTI International; U10 HD063072, Case Western Reserve University; U10 HD063047, Columbia University; U10 HD063037, Indiana University; U10HD063041, University of Pittsburgh; U10 HD063020, Northwestern University; U10 HD063046, University of California Irvine; U10 HD063048, University of Pennsylvania; and U10 HD063053, University of Utah. In addition, support was provided by respective Clinical and Translational Science Institutes to Indiana University (UL1TR001108) and University of California Irvine (UL1TR000153).

Footnotes

A version of this paper was presented at the 66th Annual Meeting of the Society for Reproductive Investigation, Paris, France, March 12 to 16, 2019.

Conflict of Interest

B.M.M. reports grants from NICHD, during the conduct of the study. R.W. received consulting fees from Natera, Bioreference, and Illumina, Inc, in addition to grants (that go directly to Columbia University) from Sequenom and Illumina, Inc., outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Harvey MW, Braun B, Ertel KA, Pekow PS, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L. prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and odds of cesarean delivery in hispanic women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(01):185–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedderson MM, Gunderson EP, Ferrara A. Gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115 (03):597–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masho SW, Urban P, Cha S, Ramus R. Body mass index, weight gain, and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Am J Hypertens 2016;29(06):763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simas TA, Waring ME, Liao X, et al. Prepregnancy weight, gestational weight gain, and risk of growth affected neonates. JWomens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(04):410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein RF, Abell SK, Ranasinha S, et al. Gestational weight gain across continents and ethnicity: systematic review and meta-analysis of maternal and infant outcomes in more than one million women. BMC Med 2018;16(01):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rooney BL, Schauberger CW. Excess pregnancy weight gain and long-term obesity: one decade later. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100 (02):245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oken E, Taveras EM, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Gestational weight gain and child adiposity at age 3 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196(04):322.e1–322.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chasan-Taber L, Silveira M, Waring ME, et al. Gestational weight gain, body mass index, and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in a predominantly puerto rican population. Matern Child Health J 2016;20(09):1804–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortner RT, Pekow P, Solomon CG, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L. Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and risk of hypertensive pregnancy among Latina women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200(02):167.e1–167.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vesco KK, Dietz PM, Rizzo J, et al. Excessive gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention among obese women. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(05):1069–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodnar LM, Siega-Riz AM, Simhan HN, Himes KP, Abrams B. Severe obesity, gestational weight gain, and adverse birth outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91(06):1642–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng YW, Eden KB, Marshall N, Pereira L, Caughey AB, Guise JM. Delivery after prior cesarean: maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Perinatol 2011;38(02):297–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Oostwaard MF, Langenveld J, Schuit E, et al. Recurrence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: an individual patient data metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(05):624.e1–624.e17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kominiarek MA, Seligman NS, Dolin C, et al. Gestational weight gain and obesity: is 20 pounds too much? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209(03):214.e1–214.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S, Sappenfield WM, Bish C, Salihu H, Goodman D, Bensyl DM. Assessment of the Institute of Medicine recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy: Florida, 2004-2007. Matern Child Health J 2011;15(03):289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimes DA. Epidemiologic research using administrative databases: garbage in, garbage out. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116(05): 1018–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas DM, Parker CB, Wing DA, et al. ; NuMoM2b study. A description of the methods of the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: monitoring mothers-to-be (nuMoM2b). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(04):539.e1–539.e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beyerlein A, Schiessl B, Lack N, von Kries R. Optimal gestational weight gain ranges for the avoidance of adverse birth weight outcomes: a novel approach. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90(06): 1552–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines; Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. report of the american college of obstetricians and gynecologists’ task force on hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122 (05):1122–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr 2003;3:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui A, Azria E, Howell EA, Deneux-Tharaux C; EPIMOMS Study Group. Associations between maternal obesity and severe maternal morbidity: Findings from the French EPIMOMS population-based study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2019;33(01):7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu SY, Kim SY, Schmid CH, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2007;8(05): 385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SY, Sharma AJ, Sappenfield W, Wilson HG, Salihu HM. Association of maternal body mass index, excessive weight gain, and gestational diabetes mellitus with large-for-gestational-age births. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(04):737–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson J, Clifton RG, Roberts JM, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health; Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Pregnancy outcomes with weight gain above or below the 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121(05):969–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kominiarek MA, Saade G, Mele L, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Association between gestational weight gain and perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132(04):875–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein RF, Abell SK, Ranasinha S, et al. Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2017;317(21):2207–2225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crane JM, White J, Murphy P, Burrage L, Hutchens D. The effect of gestational weight gain by body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009;31(01):28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel AM, Tita AT, Machemehl H, Biggio JR, Harper LM. Evaluation of institute of medicine guidelines for gestational weight gain in women with chronic hypertension. AJP Rep 2017;7(03): e145–e150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, Hinkle SN. Prevalence and characteristics associated with gestational weight gain adequacy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(04):773–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krukowski RA, Bursac Z, McGehee MA, West D. Exploring potential health disparities in excessive gestational weight gain. JWomens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(06):494–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheney K, Berkemeier S, Sim KA, Gordon A, Black K. Prevalence and predictors of early gestational weight gain associated with obesity risk in a diverse Australian antenatal population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17(01): 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Carlo C, Iannotti G, Sparice S, et al. The role of a personalized dietary intervention in managing gestational weight gain: a prospective, controlled study in a low-risk antenatal population. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289(04):765–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barakat R, Pelaez M, Montejo R, Luaces M, Zakynthinaki M. Exercise during pregnancy improves maternal health perception: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204(05): 402.e1–402.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muktabhant B, Lawrie TA, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; ((06):CD007145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, Olson CK. Achieving appropriate gestational weight gain: the role of healthcare provider advice. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27(05):552–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kominiarek MA, Crockett A, Covington-Kolb S, Simon M, Grobman WA. Association of group prenatal care with gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129(04):663–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ananth CV, Schisterman EF. Confounding, causality, and confusion: the role of intermediate variables in interpreting observational studies in obstetrics. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217(02):167–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]