Abstract

Natural killer cell enteropathy (NKCE) is a lymphoproliferative disorder, initially described by Mansoor et al (2011), that presents in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and is often mistaken for extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma on first assessment. This population of cells in this process have an NK-cell phenotype (CD3, CD56, CD2, CD7), lacks evidence of EBV infection, has germline rearrangement of the T-cell receptor, and a very indolent clinical course. Indeed, many of such patients had been originally diagnosed as having a NK/T-cell lymphoma, and subsequently received chemotherapy. We report a unique case where an indolent lymphoproliferative disorder with features that resemble NK-cell enteropathy is encountered for the first time outside the gastrointestinal tract, specifically in the female genitourinary tract. We provide morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular documentation of such, in association with a completely indolent clinical behavior of this type of process.

Keywords: NK cell enteropathy, natural killer cell, lymphoproliferative disorder

Introduction:

Natural killer cell enteropathy (NKCE) is a lymphoproliferative disorder, initially described by Mansoor et al (2011), that presents in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and is often mistaken for extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma on first assessment1.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomas are most commonly seen in the nasal cavity and upper aerodigestive tract; these can present in the GI tract, are closely associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and have a very poor prognosis2-4. In contrast, reported cases of NKCE are considered benign with no known instances of disease-related mortality1, 5, 6. They usually resolve with expectant management. Despite this, these proliferations are often misdiagnosed as malignancies with patients often undergoing systemic chemotherapy.

We report a unique case where an indolent lymphoproliferative disorder with features that resemble NK-cell enteropathy is encountered for the first time outside the gastrointestinal tract, specifically in the female genitourinary tract.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 34-year-old female with no significant past medical history. She presented to the gynecology clinic with a new, firm vaginal mass that she had first noticed one week prior. She denied pain, pruritis or abnormal discharge at the site of the tumor. On exam, a fleshy, 2 × 3cm bluish-hue lesion was noted at the right aspect of the vaginal introitus (Figure 1). The remainder of the pelvic exam was normal without any other lesions palpated or visualized. Cervix and uterus were normal with no adnexal masses palpable. Pregnancy test in the office returned positive (patient was found to be 8 weeks pregnant). The patient was otherwise healthy. She had undergone a loop electrosurgical excision procedure 12 years prior for cervical dysplasia; recent pap smears showed no evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) or cervical dysplasia.

Figure 1.

A nodular vaginal mass is present in the introitus.

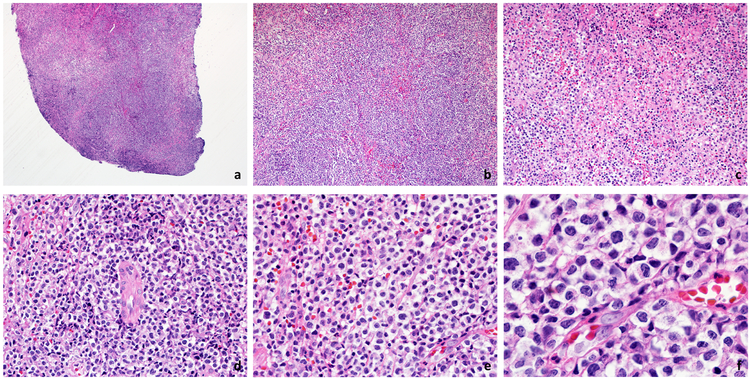

A vaginal biopsy was performed in the office: the specimen revealed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate within the mucosa, submucosa, and with extensive surface ulceration (Figure 2). The infiltrate was composed of medium to large-sized lymphoid cells with slightly irregular nuclear contours, open chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and moderate amounts of clear and somewhat granular cytoplasm. Focal areas of necrosis were present, although these areas were relatively small. The infiltrate showed areas with a prominent angiocentric pattern, but lacked destruction of the blood vessel walls or fibrinoid changes (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

A punch biopsy from the lesion shows a completely ulcerated mucosa with central areas of necrosis. A very dense infiltrate in the submucosa is noted (H&E, 20x).

Figure 3.

(a) The infiltrate extends to the deeper portions of the biopsy (H&E, 40x). (b,c) Focal areas of necrosis are seen in the infiltrate (H&E, 100x and 200x). (d) The atypical lymphocytic infiltrate exhibits angiotropism in the absence of angionecrosis (H&E, 400x). (e,f) The cytologic features of this infiltrate are characterized by the presence of medium and large cells, with ample cytoplasm, fine granularity, and some nuclear contour irregularities. Mitotic figures are present (H&E, 600x and 1000x).

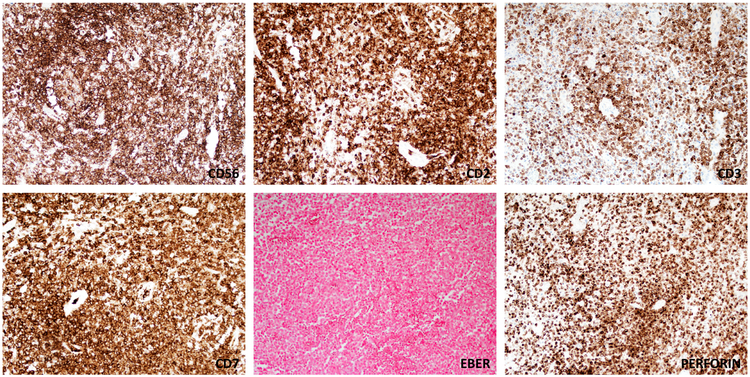

Immunohistochemical stains of the formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections were obtained (Figure 4). The atypical cells were immunoreactive with antibodies to CD3, CD56, CD2, perforin and CD7. The atypical cells lacked expression of CD4, CD8, CD5, CD30, suggestive of an NK-cell phenotype. TIA-1 and Granzyme B were also negative. TCRγ and TCRβ were also negative by immunohistochemistry. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA was also negative and HSV-1 and HSV-2 studies were negative. HPV RNA Scope in-situ hybridization was negative for low-risk and high-risk subtypes. The neoplasm showed a high proliferation index as measure by Ki67 immunohistochemsitry (~50-75%).

Figure 4.

Immunophenotypic features of the infiltrate. The atypical lymphoid cells are positive for CD56, CD2, CD3 (partial and with a cytoplasmic character), and CD7. EBER is negative in the lesional cells. Most of the cells show expression of the cytotoxic marker perforin.

Molecular, Cytogenetic, and FISH Analysis

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) did not detect rearrangement of the T-cell receptor-γ chain gene (TCR). Comprehensive next generation sequencing and RNA sequencing (FoundationOne Heme) testing showed the tissue to be microsatellite. There were no detectable mutations (n=400 genes), and no fusions (n=250 genes). Thermo Fisher Scientific OncoScan single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray analysis showed no clinically significant copy number or single nucleotide variants.

Wide local resection of the mass with 1cm margins revealed a well circumscribed nodular infiltrate of atypical lymphoid cells, confined to the nodule without infiltration into adjacent tissue. The infiltrate did not extend to the surgical margins.

Initially, the histopathologic analysis raised concern that the mass represented an NK/T-cell lymphoma or peripheral T-cell lymphoma with an NK-cell phenotype. An extensive workup which included magnetic resonance imaging and whole-body positron emission tomography scan was performed. Initial MRI imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was notable only for fullness of the vaginal soft tissues at the introitus without any gastrointestinal involvement or suspicious lymphadenopathy. A comprehensive review of the slides, in addition to the cumulative data obtained from the immunophenotype, and molecular findings, were diagnostic of an NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with features that resemble the so-called NK-cell enteropathy of the gastrointestinal tract. Following the excision, the patient has been completely disease free, without any local recurrence, or dissemination of the process outside the gynecologic tract (follow-up = 24 months).

Discussion

We report for the first time an indolent NK cell lymphoproliferative disorder with features of NK-cell enteropathy outside the gastrointestinal tract, specifically in the vagina (female genital tract). As it is common for this type of proliferation, there was an initial concern for extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma given the histopathologic features, and expression of CD56 with absence of CD2, CD4 and CD8. Further characterization of the morphology, immunophenotype and molecular studies showed the lesion to be consistent with previously described cases of NK cell enteropathy (NKCE). The cells were positive for perforin but lacked TIA-1 and Granzyme B, differing slightly from NKCE of the gastrointestinal tract.

In 2011 Mansoor et al1 reported a series of 8 patients with NK-cell enteropathy. Such patients complained of vague abdominal distress and had biopsy findings confirming the presence of an abnormal population of lymphocytes filling the lamina propia of the mucosa and in some stages destruction of the glands. In general, there was absence of significant epitheliotropism, a feature that was useful to separate apart this process from the enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma, a process in intimate association with celiac sprue. This population of cells had an NK-cell phenotype (CD3, CD56, CD2, CD7), lacked evidence of EBV infection, had germline rearrangement of the T-cell receptor, and a very indolent clinical course. Indeed, many of such patients were originally diagnosed as having a NK/T-cell lymphoma, and subsequently received chemotherapy. The study reported no instances of mortality or disease progression in 5 patients over a median follow up of 30 months. Takeuchi et al5 reported a similar cohort of patients with a so-called ‘lymphomatoid gastropathy’ in 2010. In their series the infiltrates were limited to the mucosa of the stomach, and in some cases had areas of necrosis. T-cell clonality also showed no rearrangement of the TCR.

The molecular nature of NKE is poorly understood: however, a recent study by Xiao et al6 revealed the presence of JAK3 K563_C565del mutations in 3/10 patients with NKCE (30%). The authors speculated that such mutations can lead to activations downstream of STAT3 and STAT5 signaling pathways. These results suggest a clonal and ‘neoplastic’ origin of this process, at least in a subset of cases. Interestingly, JAK3 mutations are not specific for this process and have been reported in a variety of T and NK-cell lymphomas7-12.

In our patient, evaluation with physical exam and MRI imaging showed resolution of the soft tissue mass four months following her wide local resection procedure. As in previous cases of NK cell enteropathy, resolution is seen with conservative management. Early recognition of this process as a benign entity is crucial to prevent unnecessary diagnostic and therapeutic interventions13. Outside case series have reported instances of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, surgery and bone marrow transplant for this otherwise benign lymphoproliferative disorder, a feature that can expose a patient to unnecessary complications from those forms of treament1, 14, 15.

The presence of this lesion in the genital tract falls outside the previously described sites of occurrence in the literature for NK-cell enteropathy1, 6, 16 and lymphomatoid gastropathy5. This form of reactive lymphoid proliferation likely represents an immune response to some unidentified stimulus. Testing for various infectious agents including HSV 1 and 2, HTLV 1/2 , HIV 1 and HIV2, hepatitis B and C, EBV was negative. Interestingly, to this effect Taddesse-Heath17 reported the occurrence of a tumoral lesion in the nasopharynx, associated with a brisk proliferation of CD4+CD56+ cells, simulating ENKL, in association with HSV infection. Vega et al18 speculated that one of the earliest cases of NKCE was secondary to gluten intolerance , as lesions disappeared following the introduction of a glute-free diet. Similarly H.pylori has been considered as a possible causative factor in some cases of lymphomatoid gastropathy. The inciting factor for this phenomenon outside the GI tract and its manifestation in the genital tract is unexplained and suggests a new, uncharacterized etiology14, 19. The patient had an early first trimester pregnancy at the time of diagnosis, in addition to prior history of infection by low-risk HPV, raising the question if these had a role in the manifestation of this process.

The differential diagnosis of NKCE is mostly limited to malignant lymphomas of NK or T-cell origin. Those include ENKL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified with CD56 expression, cutaneous lymphomas with CD56 expression, and blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN).

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomas (ENKL) are aggressive malignancies invariably associated with EBV infection2, 20-22. ENKL typically presents in the upper aerodigestive tract with ulceration, and destruction of the mid line septum, a feature that gave its original term of ‘midline lethal granuloma’. Some cases can also present in the skin, and on rare occasions in the female genital tract23-25. ENKL shows a malignant infiltrate of lymphoid cells with a characteristic angiocentricity and angionecrosis. The immunophenotype of this tumor shows an NK-cell phenotype (CD2, CD7, CD3ε, CD56) with the infection of EBV, a finding that can be further demonstrated by in-situ hybridization studies (EBER). Some cases of ENKL can show a T-cell phenotype, and a diagnosis can still be rendered if strong and diffuse expression of EBV is seen. Several findings were present in this NK cell proliferation that were helpful to distinguish it from ENKL, but the most significant is the absence of EBV by EBER in situ hybridization2. Furthermore, the absence of clonal T cell receptor gene rearrangements additionally ruled out a diagnosis of peripheral T cell lymphoma. At a molecular level, most cases of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomas are associated with a high degree of molecular instability and a large number of mutations and copy number changes, features that were absent on molecular analysis of this specimen.

Cutaneous lymphomas with CD56 expression include mycosis fungoides26 and primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma. Mycosis fungoides only rarely localizes to the genital tract27, 28, and in most cases is associated with prominent epidermotropism. Gamma Delta T-cell lymphomas can present in skin and mucosal associated sites, and generally are positive for CD5629. The current case lacked TCR-gamma expression and was negative for clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement, eliminating this diagnostic consideration.

In summary, we report the occurrence of NKCE-like lymphoproliferative process outside the gastrointestinal tract. We provide morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular documentation of such, in association with a completely indolent clinical behavior of this type of process.

References:

- 1.Mansoor A, Pittaluga S, Beck PL, Wilson WH, Ferry JA, Jaffe ES. NK-cell enteropathy: a benign NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease mimicking intestinal lymphoma: clinicopathologic features and follow-up in a unique case series. Blood. 2011;117(5):1447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe ES, Chan JK, Su IJ et al. Report of the Workshop on Nasal and Related Extranodal Angiocentric T/Natural Killer Cell Lymphomas. Definitions, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(1):103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gru AA, Jaffe ES. Cutaneous EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(1):60–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haverkos BM, Coleman C, Gru AA et al. Emerging insights on the pathogenesis and treatment of extranodal NK/T cell lymphomas (ENKTL). Discov Med. 2017;23(126):189–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi K, Yokoyama M, Ishizawa S et al. Lymphomatoid gastropathy: a distinct clinicopathologic entity of self-limited pseudomalignant NK-cell proliferation. Blood. 2010;116(25):5631–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao W, Gupta GK, Yao J et al. Recurrent somatic JAK3 mutations in NK-cell enteropathy. Blood. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouchekioua A, Scourzic L, de Wever O et al. JAK3 deregulation by activating mutations confers invasive growth advantage in extranodal nasal-type natural killer cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):338–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Y, Arakawa F, Miyoshi H, Niino D, Kawano R, Ohshima K. Activated janus kinase 3 expression not by activating mutations identified in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Pathol Int. 2014;64(6):263–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Park HY, Kang SY et al. Genetic alterations of JAK/STAT cascade and histone modification in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma nasal type. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):17764–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sim SH, Kim S, Kim TM et al. Novel JAK3-Activating Mutations in Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type. Am J Pathol. 2017;187(5):980–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez-Arteaga A, Margolskee E, Wei MT, van Besien K, Inghirami G, Horwitz S. Combined use of tofacitinib (pan-JAK inhibitor) and ruxolitinib (a JAK1/2 inhibitor) for refractory T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) with a JAK3 mutation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(7):1626–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivera-Munoz P, Laurent AP, Siret A et al. Partial trisomy 21 contributes to T-cell malignancies induced by JAK3-activating mutations in murine models. Blood Adv. 2018;2(13):1616–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porcu P, Caligiuri M. A sheep in wolf’s clothing. Blood. 2011;117(5):1438–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang R, Kariappa S, Toon CW, Varikatt W. NK-cell enteropathy, a potential diagnostic pitfall of intestinal lymphoproliferative disease. Pathology. 2019;51(3):338–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia D, Morgan EA, Berger D, Pinkus GS, Ferry JA, Zukerberg LR. NK-Cell Enteropathy and Similar Indolent Lymphoproliferative Disorders: A Case Series With Literature Review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2019;151(1):75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh J, Go H, Lee WA, Jeon YK. Benign Indolent CD56-Positive NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Lesion Involving Gastrointestinal Tract in an Adolescent. Korean J Pathol. 2014;48(1):73–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taddesse-Heath L, Feldman JI, Fahle GA et al. Florid CD4+, CD56+ T-cell infiltrate associated with Herpes simplex infection simulating nasal NK-/T-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2003;16(2):166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vega F, Chang CC, Schwartz MR et al. Atypical NK-cell proliferation of the gastrointestinal tract in a patient with antigliadin antibodies but not celiac disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(4):539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganapathi KA, Pittaluga S, Odejide OO, Freedman AS, Jaffe ES. Early lymphoid lesions: conceptual, diagnostic and clinical challenges. Haematologica. 2014;99(9):1421–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated T and NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Au WY, Weisenburger DD, Intragumtornchai T et al. Clinical differences between nasal and extranasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: a study of 136 cases from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2009;113(17):3931–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezk SA, Zhao X, Weiss LM. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoid proliferations, a 2018 update. Hum Pathol. 2018;79:18–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briese J, Noack F, Harland A, Horny HP. Primary extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (“nasal type”) of the endometrium: report of an unusual case diagnosed at autopsy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61(3):164–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang JC, Zhou J, Li Z, Xia ZX. Primary extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal-type of uterus with adenomyosis: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omori M, Oishi N, Nakazawa T et al. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type of the uterine cervix: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44(5):430–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang RC, Sakata S, Chen BJ et al. Mycosis fungoides in Taiwan shows a relatively high frequency of large cell transformation and CD56 expression. Pathology. 2018;50(7):718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiam LY, Chan YC. Solitary plaque mycosis fungoides on the penis responding to topical imiquimod therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(3):560–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geller S, Pitter K, Moskowitz A, Horwitz SM, Yahalom J, Myskowski PL. Treatment of Vulvar Mycosis Fungoides Tumors With Localized Radiotherapy. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(7):e279–e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guitart J, Weisenburger DD, Subtil A et al. Cutaneous gammadelta T-cell lymphomas: a spectrum of presentations with overlap with other cytotoxic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(11):1656–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]