Abstract

Objectives

To describe the protocol of a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and mechanisms of three behavioral interventions.

Methods

Participants will include up to 343 Veterans with chronic pain due to a broad range of etiologies, randomly assigned to one of three 8-week manualized in-person group treatments: (1) Hypnosis (HYP), (2) Mindfulness Meditation (MM), or (3) Education Control (EDU).

Projected Outcomes

The primary aim of the study is to compare the effectiveness of HYP and MM to EDU on average pain intensity measured pre- and post-treatment. Additional study aims will explore the effectiveness of HYP and MM compared to EDU on secondary outcomes (i.e., pain interference, sleep quality, depression and anxiety), and the maintenance of effects at 3- and 6-months post-treatment. Participants will have electroencephalogram (EEG) assessments at pre- and post-treatment to determine if the power of specific brain oscillations moderate the effectiveness of HYP and MM (Study Aim 2) and examine brain oscillations as possible mediators of treatment effects (exploratory aim). Additional planned exploratory analyses will be performed to identify possible treatment mediators (i.e., pain acceptance, catastrophizing, mindfulness) and moderators (e.g., hypnotizability, treatment expectations, pain type, cognitive function).

Setting

The study treatments will be administered at a large Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the northwest United States. The treatments will be integrated within clinical infrastructure and delivered by licensed and credentialed health care professionals.

Keywords: Chronic Pain, Hypnosis, Mindfulness Meditation, Complementary and Integrative Medicine

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine recognizes pain as a major public health problem that costs our nation $560–635 billion annually, including health care costs and lost productivity.[1] Recent research estimates that 19% of adults in the US have chronic pain, although rates vary by age, gender, ethnicity, and education level.[2] Veterans of the US Armed Forces are a sub-population of particular importance, as Veterans report greater pain prevalence and severity than civilians.[3] As many as 50% of male and 75% of female Veterans seen in primary care[4, 5] and 82% of Veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan report chronic pain.[6] Some types of pain, such as headaches, can become more prevalent in the years following deployment.[7] In both civilians and Veterans, chronic pain is associated with co-morbidities such as mood and sleep disorders.[8–10] Robust associations between pain intensity, psychological distress, and functional disability are well-documented. Conditions tend to be more severe, enduring, and treatment-resistant when they co-occur.[6]

The Federal Pain Research Strategy (FPRS) recommends a biopsychosocial approach to managing chronic pain and calls for research to determine optimal approaches for use of self-management strategies.[11] The FPRS notes that self-management for pain involves interventions that can be learned and adopted by an individual or initiated in the context of therapy and subsequently maintained by the individual, and specifies that while a number of self-management strategies are promoted for pain, crucial questions remain regarding efficacy and effectiveness, use with prescribed treatments, proper dosing, patient adherence, and the identification of biological mechanisms.[11]

Two self-management approaches, hypnosis (HYP)[12–14] and mindfulness meditation(MM)[15–17], show promise across a range of chronic pain conditions and have been identified as priorities for further study and dissemination.[18] Both teach skills that can be used independently, thus minimizing the need for ongoing appointments, travel, and provider time. In addition to efficacy for reducing pain intensity across a wide range of chronic pain conditions,[19–21] there is preliminary evidence suggesting that HYP is an efficacious way to treat depression,[22] insomnia[23, 24], and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD),[23, 25, 26]. HYP has also been shown to increase a sense of control over pain and overall well-being.[27, 28] Similarly, in addition to research demonstrating that MM can lead to reductions in pain intensity,[16] pain interference,[15, 29] and pain-related affect,[30, 31] MM has also been shown to be effective for treating conditions frequently co-occurring with pain in Veterans, including sleep problems[32, 33], anxiety,[31, 34] and depression.[35, 36]

Research on biological mechanisms that may underlie HYP and MM has focused on brain oscillations.[37, 38] In one pilot study, for example, we found that the individuals with chronic pain who had the most pain reduction with hypnosis evidenced:(1) more overall baseline theta power and (2) less gamma assessed over the left anterior brain region. On the other hand, participants who reported the most pain reduction in response to an audio recording of a meditation exercise evidenced more alpha power at baseline. These preliminary findings are consistent with hypotheses regarding the role that theta oscillations and inhibition of left anterior brain activity may play in facilitating response to hypnosis.[37, 39] Moreover, the finding that a lack of alpha predicts response to a meditation exercise is consistent with other the findings that meditation practice may operate, at least in part, via its effects on slow oscillation activity, including alpha power.[38]

Although preliminary work is promising, treatment effects for behavioral therapies tend to be modest, and understanding how and for whom pain treatments work is needed to maximize their efficacy and ensure optimal implementation.[40–45] This trial will fill important gaps in the literature by comparing the effectiveness of HYP and MM for chronic pain to a rigorous education control condition (EDU),[46] [47] examining the effects of HYP, MM, and EDU on a range of co-morbid conditions, and identifying the biological and psychological mechanisms of action.[42]

Methods

Design Overview

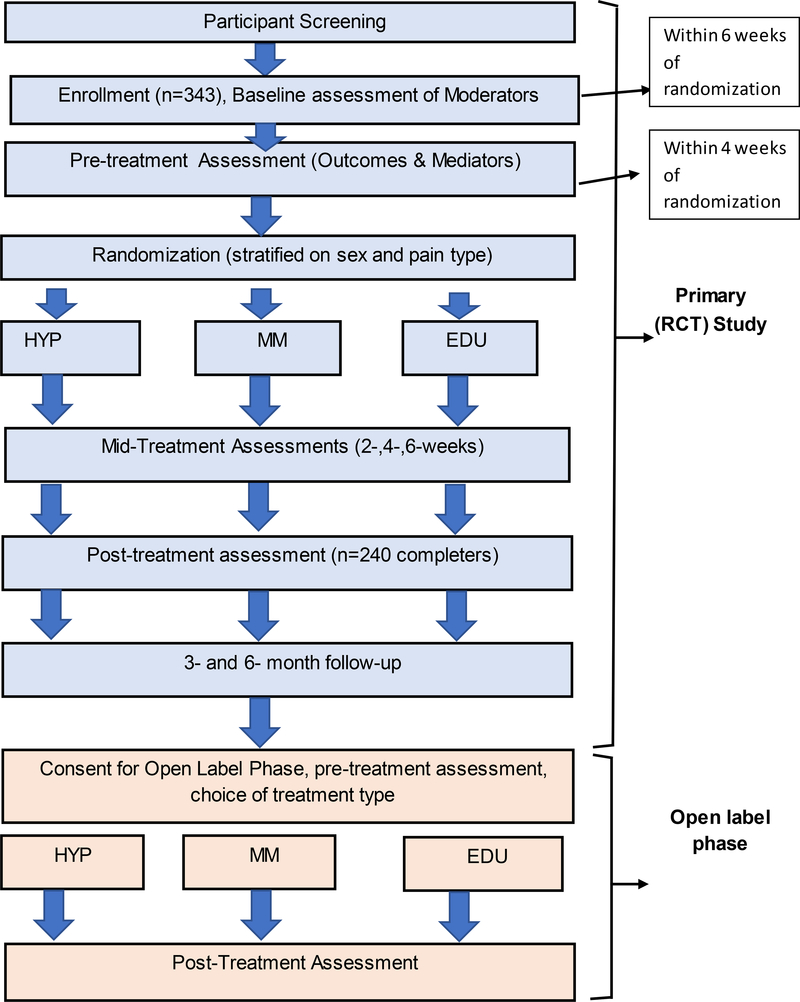

We propose a randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness and mechanisms of HYP and MM on chronic pain in Veterans. Participants will be randomly assigned to 8 standardized and manualized, in-person, group sessions of (1) HYP, (2) MM, or (3) EDU. Primary (average pain intensity) and secondary outcomes (pain interference, sleep quality, depressive symptoms, PTSD) will be assessed at pre-treatment, every 2 weeks during treatment, post-treatment, and at 3- and 6-month follow-up. Electroencephalogram (EEG; assessed at pre- and post-treatment only) will be used to assess brain oscillation power at different frequencies. All study methods and procedures have been approved by the Human Participants Review boards at the University of Washington and the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS), and the study sponsor. All study participants will provide informed consent. The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier NCT02653664. The overall flow of study procedures is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of Study Procedures

Specific Aims and Hypotheses

Aim 1 is to determine the effectiveness of 8 sessions of HYP and MM training for reducing characteristic pain intensity in Veterans, relative to 8 sessions of EDU. The Primary Study Hypothesis is that Veterans receiving 8 sessions of HYP or MM training will report significantly greater pre- to post-treatment decreases in average pain intensity than Veterans receiving 8 sessions of EDU.

Aim 2 is to evaluate the moderation effects of brain states (as measured by EEG) on response to HYP and MM. The associated Aim 2 hypothesis is that participants who report the most pain intensity reduction with HYP will evidence higher levels of global theta activity and lower levels of left frontal gamma activity at baseline, and participants who report the most pain reduction with MM will evidence lower levels of alpha activity at baseline.[37, 42] There are no a priori hypotheses regarding the ability of baseline brain activity to predict pain reduction following EDU, although exploratory analyses are planned to examine these associations.

In addition to testing the above specific hypotheses, the data obtained in this study will be used to further explore (1) the effects of HYP and MM on secondary outcome measures (including pain interference, sleep disturbance, and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD); (2) the effects of HYP and MM relative to each other and to the EDU condition on all outcomes; (3) the longer-term (up to 6 months) effects of HYP and MM, relative to EDU; and (3) additional potential moderators (e.g., hypnotizability, treatment outcome expectancies, treatment motivation, demographic variables, pain type [neuropathic vs. nociceptive], cognitive functioning) and mediators (changes in EEG activity, pain acceptance, catastrophizing, mindfulness, therapeutic alliance, amount of skill practice between sessions) of treatment outcome.

Study Setting

This study is a joint effort between the University of Washington School of Medicine and VA Puget Sound Health Care System. All participants will be Veterans residing in Washington State receiving care at either of the two hospital facilities that comprise VAPSHCS: American Lake or Seattle. Though these two large VA Medical Centers are approximately 45 miles apart, VAPSHCS is conceptualized as a single entity, with a single IRB. All treatment intervention activities will occur in person at VAPSHCS. Participants will be consented at VAPSHCS and complete baseline assessments in person at VAPSHCS. Subsequent assessments will be completed via telephone. The EEG assessments will be conducted at the nearby University of Washington Integrated Brain Imaging Center (IBIC).

Participants

The target population will be Veterans with chronic pain due to a range of etiologies who seek care at VAPSHCS between 2015 and 2019. Projected enrollment will be n=343, to ensure complete data from n=240 participants and to ensure adequate capacity to enroll equivalent cohorts throughout the study (25–30 participants will be enrolled in each of the study’s anticipated 12 cohorts). Inclusion criteria were designed to maximize ecological validity and will include: (1) Veteran status (defined as prior service in the US Armed Forces and eligible to receive health care services through Veterans Health Administration); (2) 18 years of age or older; (3) self-reported presence of moderate or greater severity chronic pain; and operationalized as average self-reported pain intensity rating of ≥ 3 on a 0–10 Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) in the last week, worst pain intensity of ≥ 5 on a 0–10 NRS in the last week, duration of chronic pain 3 months or more, and experience of pain at least 75% of the time in the last 3 months; (4) able to read, speak, and understand English well enough to participate in telephone assessments; (5) willing to be randomized to condition and provide informed consent; (6) willing to consent to participate in audio-recording of sessions (for treatment fidelity purposes).

Exclusion criteria were selected to ensure that participants who would be unable to participate effectively or appropriately in telephone-based assessments and group-based interventions will be ruled out, and include: (1) severe cognitive impairment defined as two or more errors on the Six-Item Screener;[48] (2) psychiatric or behavioral conditions in which symptoms are unstable or severe within the past 6 months; (3) current or history of diagnosis of any psychotic or thought disorder within the past 5 years; (4) hospitalization for psychiatric reasons other than suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, and/or PTSD within the past 5 years; (5) behavioral conditions that would preclude safe or effective group participation; (6) presenting symptoms at time of screening that would interfere with participation, specifically active suicidal ideation with intent to harm oneself; (7) difficulties or limitations communicating over the telephone; (8) reported average daily use of >120 mg morphine equivalent dose (MED).

Recruitment, Screening, and Enrollment

The study will be integrated within a VAPSHCS clinical program called the “Chronic Pain Skills Program,” described below and created for purposes of providing clinical infrastructure for this study. Participants will be recruited into the study via several mechanisms. A clinical order mechanism will be created so that providers can write orders to directly refer Veterans to the study via the Chronic Pain Skills Program. Once referred by a provider, study staff will contact the Veteran to provide study information and screen for eligibility. To foster clinician referrals, the VA-based study investigators will regularly send electronic reminders about the program and referral instructions to providers and offer educational in-services to clinical teams. The second recruitment method will be medical record review. Medical records from select clinics will be reviewed using standardized screening forms to identify appropriate candidates. Staff will be trained to ensure consistent identification of eligible Veterans. Potential participants will then be contacted via an approved series of approach letters and telephone calls. Finally, Veterans may self-refer to the study based on seeing flyers and other informational documents that will be available on site. Veterans who self-refer will go through the same screening process as Veterans referred by clinicians.

Prospective participants will be screened by research staff members to determine eligibility. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be assessed via a combination of medical record review and self-report, and reasons for ineligibility will be collected for purposes of adhering to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) standards.[49] A study investigator who is a VA-based Clinical Psychologist (RW) will conduct psychological screens of all prospective participants by reviewing medical records using a standard case report form (CRF). The reviewing psychologist will evaluate the psychologically-relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure absence of suicide risk, behavioral concerns, and psychotic disorders or symptoms. In instances where this information cannot be determined by prospective participant self-report and chart review alone, the psychologist will contact prospective participants by telephone and conduct a brief standardized interview to assess these potential risk factors and use clinical discretion as indicated to determine eligibility and safety.

Individuals who are eligible and express an interest in study participation will be invited to participate in an informed consent process, conducted in person. Individuals who decline to participate will be asked to provide a reason as well as basic demographic information to facilitate comparison between study participants and those who are eligible but decline to participate. Eligible individuals who consent to participate will complete an in-person baseline evaluation that includes several measures that are necessary to inform randomization.

Randomization and Scheduling

Once participants complete all baseline assessments, they will be randomized to one of the study treatment conditions, coded as 1, 2 or 3. Participants will be randomized to stratified blocks based on sex/gender and pain type (neuropathic, non-neuropathic, mixed or undetermined), assessed via the Pain DETECT[50] measure and the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS)[51] to ensure uniform distribution of these factors across the three conditions. Assignment to one of the three groups will be accomplished with a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet with random numbers created by the research manager with the guidance of the biostatistician. The study coordinator will complete the randomization and populate a roster/schedule for each group in each cohort. This roster, which will be stored on a secure database in a password protected file, will then be provided to a study investigator (RW), who will write scheduling orders for the participants’ interventions appointments in the Chronic Pain Skills Program clinic.

Blinding

Participants will be blind to the study hypotheses. During informed consent, and to maximize the chances that the prospective participants will have similar outcome expectancies regarding the three treatment conditions, prospective participants will be told that each of the three conditions is a type of “pain self-management” intervention that previous patients have found to be helpful, and that the purpose of the study is to determine which of these interventions is most helpful for which outcomes.

All research staff conducting recruitment and assessments will be blind to the randomization assignment database, maintaining concealment of allocation. All research staff conducting the outcome assessments will remain blind to treatment condition throughout the follow-up period. The staff member who will randomize participants will be blind to all identifying information and will also be blind to the code identifying specific treatment assignments. A separate database without any information about treatment assignment will be used to track and enter assessments. This will be done to ensure that research staff members who will perform outcome assessments remain blind to group assignment and that assessment schedules are synchronized with intervention progress. The clinicians who administer the study interventions will not be blind to condition but will be blind to the status of participants in their groups (who may or may not be enrolled in the research study) and to the specific study hypotheses. The investigator responsible for psychological screening, clinical scheduling of group appointments (RW), and management of adverse events will not participate in allocation/randomization or assessments. Study investigators will not be blind to allocation but will also have minimal direct interaction with subjects. To ensure integrity of analysis, an independent biostatistician (MC) and data manager (KG), both of whom blind to the intervention codes/allocation, will conduct study analyses. A summary table clarifying the “blind” status of key study personnel is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Blindedness Status of Key Study Personnel

| Person | Study Roles Relevant to Blind Status | If/When Blinded |

|---|---|---|

| MJ, Co-PI | Oversees training of study clinicians and data analysis, provides supervision to interventionists leading HYP. | Blind to all data. |

| RMW, Co-PI | Psychological screens, clinical implementation of study interventions, participant scheduling, and address clinical issues and adverse events. Not a study interventionist. | Unblind entire study. |

| MC | Biostatistician | Blind entire study and through all analyses. |

| All Co-Investigators based outside VAPSHCS. | Provide training and supervision to study therapists. Blinded to all data, no opportunity for unblinding. | Entire study. |

| AT, Co-I | Clinical back-up for RMW for scheduling and addressing clinical issues/AEs | Unblind entire study |

| SH, Co-I | Study Neurologist, oversees EEG. Blinded (no opportunity for unblinding) | Entire study. |

| KG, Manager | Set up data bases and oversees data management. | Blind during data collection phase of study. |

| MP | Unblinded (May collect information about use of skills learned as part of study treatment while undergoing EEG assessment.) | N/A |

| Study Assistant Not an author | Based at UW, randomizes subjects (by ID) to Condition (code number), conveys randomization assignments to CK | Blind entire study |

| CK, Study Coordinator | Unblinded. Receives randomization assignments and builds group rosters. Assists with coordination of collection and entry of treatment data (e.g., attendance) session audio recordings/treatment fidelity. | N/A a |

| Study Staff (AM Plus 3 additional Staff) | Informed consent and all assessments | Blind to allocation entire study |

| Study Intervention Leaders/Clinicians | Blind to research status of participants in the room and study hypotheses. | Entire study |

| Study Participants | Blind to study hypotheses but not allocation. | Entire study. |

| External study staff | Unblinded. Treatment fidelity ratings | Entire study |

Trial Design

The majority of potential moderator variables (several of which are relevant for randomization stratification) will be assessed at baseline, which will be conducted typically immediately after consent, and per protocol within 6 weeks of starting treatment. The majority of outcome (both primary and secondary) and mediator data will be collected during a separate “pre-treatment” assessment, which will be conducted prior to randomization, within 4 weeks of treatment starting. Participants will also be complete brief assessments at 2-, 4-, 6- weeks during-treatment, and full assessments of outcomes at post-treatment, and 3- and 6- months after treatment completion.

After baseline and pre-treatment assessments, study participants will be randomly assigned to eight group sessions of one of three manualized, group-based, in-person treatments: HYP, MM, or EDU. All three study interventions will be offered three times per year, in synchronized cohorts to ensure equivalent availability across conditions and the two VA study sites. A total of six groups will be offered per cohort (one of each intervention type at each of the two VA hospital sites).

The study will involve 12 cohorts (3 per year). In order to optimize ethical research and ensure all participants have access to a treatment of their choice, those participants enrolled in cohorts 1 through 9 who complete the study without any evidence of difficulty will be invited to continue in an open label study upon completion of the final assessment for the primary trial. In the open label phase, participants will be invited to choose any of the three interventions that they were not randomized to as part of the main trial. Participants may participate in the open label phase a second time (i.e., complete the third study intervention) if space is available in those cohorts/groups. A separate consent form will be required prior to the open label phase. Baseline and post-treatment measures will be assessed for the primary and secondary outcomes only. Participants in cohorts 10–12 will not be offered the open-label phase as they will not finish the outcome assessments in time to participate in the open label phase within the study period; rather, participants in these cohorts will be offered the treatment materials (participant manual and audio recordings for home practice) for an alternative treatment. For participants who complete a third study intervention after the formal open label phase, no additional consent form will be required, and no data will be gathered in the third round.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions in conditions that are as ecologically valid as possible, we will develop a clinical program called the “Chronic Pain Skills Program” within the Rehabilitation Service Line at VAPSHCS. Additionally, the three treatment interventions will be simultaneously and equally available for Veterans who do not participate in the research study (“non-research participants”); see Table 2 for clarification of the differences between research and non-research participants. It is expected that, as the study progresses and participants in the main study complete the follow-up assessments, there will be a mix of participants in each intervention group, including research participants in the main study phase, research participants in the open label phase, and non-research participants. As space permits, non-research participants will also have an opportunity to participate in additional intervention types.

Table 2.

Differences between research study participants and Veterans who participate in the intervention classes part of their usual clinical care (“non-research participants”).

| Research Participants | Non-Research Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Required to Complete Informed Consent and Enroll in Study | Yes | No |

| Eligibility Criteria, Inclusion Exclusion | Required to meet all inclusion/exclusion criteria, willing to be randomized | Required to meet all inclusion and exclusion criteria except chronic pain duration could be < 3 months and < 75% of the time. MED > 120 mg not an exclusion for non-research |

| Intervention: leaders, content, times, dates, locations | Same | Same |

| Clinic Logistics, TravelPay, Co-Pays | Same | Same |

| TreatmentOrder/Choice | Randomized to first treatment, choice for open label phase | Veteran chooses first, and potentially second intervention type, analogous to open label phase |

| Assessments | Phone assessments at pre-treatment, 2,4,6 weeks mid-treatment, post-treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up | None |

| Compensation | Up to $450 for all study assessments. No compensation for actual intervention classes. | None |

Offering the study interventions within this clinical infrastructure is permissible at VAPSHCS because: (1) all three interventions currently have sufficient evidence to support their clinical use[18]; (2) the interventions will be equally available to Veterans who do not participate in the research study (“non-research participants”); and (3) the study interventions to be offered will address a gap in currently available clinical services. While this study is being conducted, there will be no other clinical trials that have overlapping content. Offering the study intervention within clinical infrastructure and including non-research participants will afford some key scientific benefits, described in the discussion section.

Study Interventions

The study interventions will be equivalent in terms of time and structure. All interventions will be comprised of eight 60–90-minute group-based sessions scheduled over 8–10 weeks. The interventions will be entirely integrated within routine clinical practice. Groups will be offered in synchronized cohorts (each of the three treatment conditions will start within the same week) to ensure equivalent availability, convenience, timing, and access at the point of randomization. All intervention appointments will be regular clinic appointments, with associated progress notes, workload credit, and administrative encounter requirements. From a participant perspective, the intervention appointments will appear on appointment lists and in medical records. Participants will receive automated appointment reminders. Veterans who normally have co-pays for their care will have co-pays for these appointments, and Veterans who are normally reimbursed for travel expenses will be reimbursed for these appointments. Participants will be instructed to participate in other care as usual during the study. Participants will be asked to refrain from making changes to the amount or type of medications they typically take for pain during the study treatment unless it is determined by them and their health care provider that changes in medication are needed. We will assess medication use throughout the course of the study to ensure we can control for changes in pain medication use.

Intervention Facilitators: Training and Ongoing Supervision

All study interventions are designed so they can be delivered by a variety of health professionals. Study interventions will be delivered by licensed and credentialed allied health professionals already on staff at VAPSHCS (e.g., nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists) and/or their advanced trainees as part of their routine clinical duties. Intervention facilitators will lead each of the three 8-week interventions once during a year, in randomized counter-balanced order.

Intervention facilitators will be trained and supervised by the study investigators, each of whom has recognized expertise in at least one of the study interventions. Study investigators will train cohorts of intervention facilitators annually. Training will involve self-study of required readings[52–54] plus a 16-hour in-person training that includes didactic instruction, role plays and individualized feedback and coaching. Intervention facilitators will also be required to complete institutional mandatory trainings in privacy, information security and good clinical practices for researchers.

Intervention facilitators will participate in bi-weekly telephone-based supervision and consultation calls specific to the current intervention they are leading. Group supervision will focus on delivery of specific study treatments and management of any clinical or administrative study issues that arise during the study intervention classes. Intervention facilitators will be assigned in pairs to co-lead the study groups and at least one co-facilitator from each group will be required to attend the supervision calls.

Intervention Content

Rationale for Selection of Intervention Conditions. Jensen [55] proposed a framework to organize the key factors affected by psychological pain treatments, which are thought to include: (1) the environment/social context (to include therapeutic alliance and expectations); (2) brain states; (3) cognitive content (e.g., catastrophizing); (4) cognitive coping; and (5) behavior. HYP and MM are thought to have a direct effect on some of these factors. For example, both HYP and MM focus on induction of brain states that are hypothesized to influence cognitive processes (openness to suggestion, acceptance, mindfulness) primarily, but could also have indirect effects on cognitive content (catastrophizing). Whereas pain-related cognitive content refers to the beliefs that patients have about pain, pain-related cognitive coping refers to what patients do with thoughts and their relationship to them. Such processes are primary targets of both HYP and MM and include awareness of one’s experience without judgment (“acceptance”), as well as general mindfulness. Behavior in the context of HYP and MM interventions refers to how often patients actually use these skills as coping strategies.

Study intervention materials were written by the study investigators based on those used in other trials. [19, 53, 56–59] These materials were adapted for the Veteran population by the clinical psychologists involved in the study who have expertise in chronic pain treatment, Veteran/military culture, and the co-occurring conditions that are common in the target population. All interventions will utilize a corresponding clinician manual and participant treatment workbook. The participant workbooks will contain session-specific content to be discussed during the sessions as well as relevant supplementary material to be reviewed between sessions. Participants in all treatments will also receive professionally produced audio recordings to listen to between sessions to augment material covered in the interventions. Study investigators will write the scripts for the audio-recordings to directly parallel the material included in the treatment manuals. All three interventions are grounded in theories of adult learning and principles of pain self-management. Note that in contrast to many studies that involve a common Session 1 that covers basic pain education,[60] in this study only the Education condition will include this information.

HYP condition

The HYP intervention content will be based on published manuals[53], which were refined in prior trials.[19, 56] Hypnosis has two critical components: (1) a state of consciousness that facilitates openness to change and (2) suggestions for change. These components are reflected in the two phases of hypnosis: (1) an “induction” phase during which the clinician invites the participant to focus his or her attention on a specific experience (e.g., the clinician’s voice, a spot on the wall, the participant’s breathing), deepen focus and suspend critical thinking, followed by (2) specific suggestions for therapeutic change, such as changes in sensations, thoughts, or behaviors thought to influence the experience of pain. Evidence shows that the beneficial effects of hypnosis are specific to the suggestion.[27, 61] Each session will include the same general format: (1) a preliminary discussion of the material to be covered in that session; (2) an in-person group hypnotic induction followed by hypnotic suggestions; and (3) post-hypnosis discussion that includes recommendations and encouragement for between-session self-hypnosis practice by listening to hypnosis recordings and by practicing without the recordings on a daily basis.

Session 1 will include basic information about hypnosis for pain and an overview of expectations for group participants, in addition to a hypnotic induction. Sessions 2–8 will start with a review of home practice, problem-solving any challenges with engaging in practice, sharing observations, and then the practice of a new induction. Each session will include a post-hypnosis discussion, a review of any concerns or questions as appropriate, and reinforcement, via reflective listening, for any positive experiences or statements indicative of hope and positive outcome expectancies. Home practice plans will be discussed and affirmed.

For all hypnotic inductions performed in the group setting, the participants will be invited to relax in a comfortable position with their eyes closed and will simply listen to the clinician read a standardized hypnotic script. Each script will include induction, specific hypnotic and post-hypnotic suggestions (content will vary by session, see Table 3), and then a post-hypnosis alerting process. In-session hypnotic inductions and home practice recordings will range from 15–30 minutes in length. All the suggestions embedded in the hypnotic sessions will relate to some combination of increased comfort, increases in adaptive thoughts about or the meaning of pain, or improvement in co-morbid symptoms (e.g., improved mood and optimism, relaxation, sleep quality).

Table 3.

Session content for the Hypnosis (HYP) and Mindfulness (MM) interventions.

| Session # | Targets of the hypnotic suggestions | Mindfulness |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Decrease uncomfortable sensations. | Body scan meditation; 3-minute breathing space. |

| 2 | Increase comfort and decrease pain unpleasantness. | Body scan meditation; 3-minute breathing space. |

| 3 | “The true purpose of pain”, differentiating between useful and not useful signals, dimming pain signals that are not useful. | Breath and body focused seated meditation; 3-minute breathing space. |

| 4 | Reassuring thoughts, image of a caring thought monitor that automatically transforms thoughts into reassuring and helpful thoughts. | Mindfulness of sounds and thoughts; 3-minute breathing space. |

| 5 | Age progression for comfort and confidence—visualize a more comfortable and confident future version of yourself. | Mindfulness of breath, body, sounds and thoughts plus introducing working with a difficulty within the practice. |

| 6 | Well-being and self-confidence, ego strengthening. | Mindfulness of breath, body, sounds and thoughts plus introducing working with a difficulty within the practice. |

| 7 | Increased comfort and improved sleep quality. | Sitting in silence meditation practice; 3-minute breathing space. |

| 8 | Consolidation; your mind as a powerful resource. | Returning full circle back to the body scan; concluding meditation with an object (e.g., stone, bead, marble). |

MM condition

Mindfulness Meditation (MM) is the core skill taught across integrated mindfulness interventions. MM aims to systematically train the mind to observe thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations intentionally, on a moment-to-moment basis, with a non-judgmental attitude, such that these are increasingly perceived as transient, variable experiences. This combination of regulation of attention decoupled from emotion is hypothesized to be the central mechanism across forms of MM.[62] It has been purported that this, in conjunction with the cultivation of mindfulness and pain acceptance, underlies reductions in pain.

The MM intervention will be based on manuals developed by the investigator team [57] and will teach participants Vipassana, which is the specific form of MM typically implemented in mindfulness research. Each of the MM sessions will follow the general format of: (1) orientation and presentation of the theme of the session; (2) discussion of at-home practice (except for session 1); and (3) in-session MM practice and guided inquiry that includes exploration of participant’s experiences with the practice, including processing any “difficulties” with the practice as well as encouraging patient, gentle persistence in daily practice. The in-session guided meditations will be delivered by the interventionists using standard scripts. In session 1, basic information about confidentiality, group members’ roles, and MM will be presented prior to delivering the first meditation practice followed by a guided inquiry. Sessions 2–8 will entail a guided inquiry of the participant’s home practice, again, with an emphasis on cultivating routine, daily practice as well as in-session delivery of the meditation practice for that week. As with HYP, the interventionist will engage in reflective listening to reinforce daily practice.

Across all the in-session MM practices, participants will be invited to sit in a comfortable, yet alert position; alternatively, if sitting is not comfortable, participants may also choose to stand if preferred. Participants are invited to close their eyes, or if this is not comfortable for them or if sleepiness is an issue, they are encouraged to practice with their eyes open, with their gaze fixed on a point on the floor a few feet in front of them. The emphasis is placed upon developing focused attention on an object of awareness, which initially starts with awareness of the body. This object of attention is then expanded to include a more open, non-judgmental monitoring of increasingly less tangible aspects of experience (see Table 3). Each session includes an extended MM practice, as well as training in a brief, highly portable practice (i.e., 3-minute breathing space). For the MM condition, the audio recordings include both a 20-minute and 45-minute version of each extended meditation taught in session.

Education Control Condition

The EDU condition is designed to be a credible intervention comparable to the HYP and MM interventions in terms of time, attention, delivery modality, therapeutic alliance and group cohesion and social support. Education is a familiar behavioral treatment for chronic pain that is shown to be interesting and beneficial,[47] but is not expected to have a neuromodulator effect, nor a direct effect on pain intensity.[46]

The EDU materials will be primarily based on a pain education program that was developed for and used in other trials, including one in a study of telehealth pain management for Veterans.[58, 59] The EDU materials will include 8 informational group sessions that participants in prior trials have indicated are compelling, informative, and credible.[59, 63] Topics included in the EDU intervention are shown in Table 4. In session 1, basic information about confidentiality, group members’ roles, and the value of pain education will be presented. Sessions 2–8 will entail a review of participant’s home practice assignments, introduce new topics each week, and plan for upcoming home practice activities. The EDU intervention is designed to increase participants’ knowledge about chronic pain in the context of a biopsychosocial model and increase perceived self-efficacy for pain self-management. Intervention facilitators will be instructed to provide the information to participants and facilitate discussion, but not to integrate strategies that would target specific behavior changes (i.e., staff will not monitor target behaviors, set specific behavioral goals, or use cognitive-behavioral or other empirically-supported techniques to facilitate specific behaviors or progress). The EDU audio recordings will include a summary of the topics covered in each session, and many positive affirmations of participation and effort.

Table 4.

Session Content for the Education Condition (EDU).

| Session/Topic | Specific Topics |

|---|---|

| 1: Introductions and Managing Pain | Introduction to the Biopsychosocial Model and Selfmanagement. |

| 2: Pain as an Invisible Problem | Common misconceptions about chronic pain, stigma; social context of chronic pain. |

| 3: Mood and Pain | Interaction between pain and mood. Distinction between normal mood and mood problems that are highly comorbid with pain. Fostering resilience. When and how to get mental health treatment. |

| 4: Sleep and Pain | Overview of healthy sleep cycle. Interaction between pain and sleep. Review of common sleep problems. Sleep hygiene and resources. |

| 5: Stress, pain, and being a smart consumer | Relationship between stress and pain. Physical and psychological impact of stress. General principles for evaluating new activities and information about possible new research and treatments. |

| 6: Pain and Activity | Importance of being active- physically, mentally, and in social roles. Secondary problems associated with becoming deactivated. Role of behavioral activation in pain management. Review of Pleasant/Valued activities. Activity/rest pacing. |

| 7: Pain and Communication | Military vs. civilian communication contexts. Improving communication with healthcare providers. Assertive communication in challenging situations. |

| 8: Social Support and Maintaining Gains | Impact of social support on pain experience. Review of national resources for pain, disability, mental health. Review of course content. Plans for maintenance of skills. |

Adherence and Fidelity Monitoring

All study intervention sessions will be audio recorded, and 25% of these will be randomly selected for formal review using a standardized fidelity checklist. The fidelity rating system will assess delivery of components unique and not unique (group rules, introductions, homework assigned) to each intervention and proscribed intervention elements (e.g., use of MM in an EDU session). Fidelity will be assessed following each cohort. Based on fidelity ratings, feedback will be provided to intervention facilitators as needed during study implementation.

Procedures to Maximize Participant Retention

Participants will receive up to $250 for completing the 8 main study assessments, and up to $200 remuneration for participation in the planned EEG assessments ($100 per assessment). Remuneration for the open label phase will be $20 ($10 for each assessment). There is no specific remuneration for participation in the intervention appointments; only the activities that are unique to the research are compensated.

Assessments and Measures

All assessments will be administered by research staff members who are blind to group assignment. The hypnotizability and cognitive assessments that are part of the baseline assessment will be administered once, in person. EEG assessment will occur at pre-treatment and post-treatment. All other measures will be assessed via telephone interview, using structured case report forms (CRFs) at pre-treatment, 2-, 4-, and 6-weeks mid-treatment, post-treatment, and 3- and 6-months following treatment. Specific measures to be included at each assessment point are shown in Table 4.

Primary outcome variable

Average pain intensity will be assessed using a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) of average pain in the past 24 hours. This measure will be administered up to 4 times within one week at each assessment, in telephone calls separated by at least 24 hours. Average daily pain intensity will be calculated as the mean of up to four separate pain intensity ratings collected within a 7-day window. Psychometric theory and research support composite pain measures as being more reliable, valid, and sensitive to treatment effects than single ratings.[64, 65] The 0–10 NRS has demonstrated its validity as a measure of pain intensity through its strong association with other pain measures as well as its ability to detect changes in pain with pain treatment.[66] A consensus panel has also recommended the NRS as a core outcome measure of pain intensity in clinical trials of pain treatments to facilitate comparison across multiple trials.[67]

Brain activity

Brain activity (Aim 2) will be assessed using standard practices for ensuring valid and reliable EEG measures (e.g., careful training and supervision of research assistants in EEG assessment procedures, checking impedance of all sites, not assessing women during menses, instructing participants to avoid muscle activity during the assessment).

EEG assessments will be an optional study component. EEG data will be acquired at 250 Hz sampling rate with a Phillips-EGI (Eugene, OR) Geodesic EEG System 400 using 128-channel Hydro-Cell Nets. Pre-intervention assessments will include two recordings. The first will be a 12-minute recording in which participants will be instructed to relax and hold still. The recording period will include the administration of a pain rating questionnaire about 5 minutes into the recording. The second recording will be 2 minutes in duration, during which participants will be asked to “think about their pain problem” (in order to determine what the effects of thinking about their pain might be on brain oscillation power in exploratory analyses). The EEG measured at post-intervention will include the same two recordings, plus an additional 12-minute recording during which participants will be instructed to “use whatever skill or skills” they had learned during intervention to manage pain.

Raw recordings will be band-pass filtered between 0.3–50 Hz using EGI’s proprietary software and exported to Matlab®. The recordings that included the administration of a pain intensity measure will be clipped down to exclude the pain questionnaire interval. The five recordings will then be further subdivided into 2-second long epochs for artifact screening and spectral analysis. Any epoch containing an absolute voltage deflection (max-min) exceeding 180 microvolts will be designated bad; the signal from any channel containing more than 33% bad epochs will be replaced by the mean of its nearest (“non-bad”) neighbors. Bad epochs will be determined from average reference data, but bad channels will be replaced using vertex reference recording montage (so that signals from bad sensors do not leak in through the average reference). After bad channel replacement, if any channel still includes more than 68% bad epochs, the recording will be excluded from further analysis.

Spectra from non-rejected 2-second epochs will be used to compute an average spectrum for the recording session. The sum of power (microvolts2) will be computed for delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), and gamma (30–40) bands. These values will then be converted to relative power (i.e. the proportion of summed power in the band divided by the total power of the entire spectrum (from 1 to 40Hz). The lower cutoff of the delta band was chosen to avoid any low frequency artifact resulting from body or head movement. The upper cutoff of the gamma band was chosen to avoid EMG artifact. The primary study hypotheses will use slow wave (theta and alpha) and gamma relative bandwidth power measures, although all bandwidths will be examined in planned exploratory analyses.

Secondary Outcomes, Mediators, Moderators, and Co-variates

All study participants will be asked to provide basic demographic (age, sex/gender, marital status, family income, education level, employment status) and military history (i.e., highest rank, branch of service, deployments) for descriptive purposes at baseline. All remaining variables will be assessed using standardized self-report measures, shown in Table 5, which also shows the timing of assessments. In all instances, measures will be administered in their validated forms unless otherwise noted.

Table 5.

Study Measures.

| Variable Type | Measure | When Measured |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | Average of up to 4 0–10 recall numerical scale ratings of pain intensity | All assessment points |

| Secondary outcomes | PROMIS Depression SF[68] PROMIS Anxiety SF[68] PROMIS Sleep Disturbance SF[68] PROMIS Pain Interference SF[68] PTSD Checklist-Civilian version[69] Patient’s Global Impression of Change[70] |

Assessed at all time points except Global Improvement, assessed at post-treatment only. |

| Mediators: Biological | Change in bandwidth oscillation power: theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bandwidth | EEG measured at pre- and post-treatment only. |

| Mediators: Psychological | Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire. [71] Pain Catastrophizing Scale [72] Self-Compassion Scale Mindfulness subscale[73] Working Alliance-Short Form [74] Pain Catastrophizing Scale [72] Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire- Short Form[75] Working Alliance-Short Form [74] Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation Systems BIS/BAS[76] Self-report of between-session skill practice |

Mediators assessed at all times except working alliance (measured only during treatment and post treatment) and skill practice (not collected at pre-treatment). |

| Moderators: | Baseline EEG: Theta, alpha, beta, and gamma power Stanford Clinical Hypnotizability Scale [77–79] Outcome Expectancy and Treatment Motivation: Treatment Efficacy Scale [80–82] Pain Type : LANSS[51] and Pain DETECT[83] Cognitive Function: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test©, Symbol Digit Modalities Test©, Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale – 4th Edition (Digit Span subtest)©, Trail Making Test©, Wide Range Achievement Test – 4th Edition© Functional Comorbidity Index (FCI)[84] |

Baseline and/or Pre-treatment |

Notes: PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

Several process, adherence and engagement measures will also be included to facilitate interpretation of results. Engagement with the interventions will be measured using session attendance, self-reported practice logs completed at the start of every session, and group leader ratings of engagement in each session. Treatment expectancies and credibility and treatment motivation will be assessed at baseline and mid-treatment. Qualitative feedback regarding treatment satisfaction, perceived benefits, possible negative effects of treatment or study participation, the treatment materials, intervention format, and aspects of content will be gathered by an unblinded staff member at follow-up to inform future study design. Standardized measures will be used when available (see Table 5), and others will be developed for the study as indicated.

Safety monitoring

After the EEG sessions, staff will ask about any negative effects associated with the EEG study procedures. During each assessment contact, staff will listen carefully for potential adverse effects, and at each treatment intervention session, facilitators will ask participants about any potential adverse events and note these in the progress notes. Unblinded research staff will review progress notes for possible mention of adverse events and (1) alert VA clinician investigator staff for triage/management as indicated, and (2) follow reporting guidelines for adverse events. The research team will submit quarterly reports to the study’s data safety monitor committee (DSMC) chair outlining recruitment and enrollment progress, withdrawals, protocol violations/deviations, unanticipated problems and serious adverse events that may have taken place during the review period. The entire DSMC will receive and review a report annually and make recommendations to the investigators should any concerns arise. In addition, the study sponsor will assign an independent study auditor who will review source study documents and reports annually.

Data Management

All data will be collected on paper CRFs by research staff members who will then transpose those data into the study databases. A second research staff member will complete double-entry of source data. Any discrepancies in data entry that arise will be resolved in real time by research staff. All paper source data will be kept in secure locked cabinets within a secure locked office accessible only by the research team and all electronic data will be stored in password-protected secure databases on the VA secure network drive.

Data Analyses

Missing Data

Analyses to identify potential patterns in missing outcome data will be conducted to determine if they are missing at random. Variables in groups with and without missing outcomes data will be examined; no association between observed variables and the group (missing vs. none missing) will be considered an indication that the data are missing at random. If fewer than 5% of data are missing and these data are random, then the analysis will be conducted as described as below. If greater than 5% of data are missing and/or if it is determined that there are non-random missing outcomes data, specific imputation methods will be used to account for this by modeling the joint distribution of the outcome and the missing mechanism.

General Approach to Analyses

As a preliminary step, we will check the randomization effectiveness by comparing the observed baseline characteristic and potential confounders between the three study arms, using Fisher’s Exact or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests as indicated. Attendance and attrition by intervention will be examined. Distributional descriptive and summary statistics will be presented for all primary and secondary outcomes by condition and time. An intention-to-treat approach will be used for all analyses; data from all participants who were randomized to their respective assigned treatment, regardless of how much they actually receive of that treatment, will be analyzed.

Hypothesis 1 states that Veterans randomly assigned to receive eight group sessions of HYP or MM will report significantly greater pre- to post-treatment decreases in average pain than Veterans receiving eight sessions of EDU. The response variable will be change in average pain intensity score from pre- to post-treatment. This response variable will be analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with treatment condition (HYP, MM, EDU) as the explanatory variable and the baseline pain as a covariate.

Support for Hypothesis 1 would emerge if a significant treatment main effect is present after adjusting for the baseline covariates, and subsequent post-hoc analyses indicate larger baseline to post-treatment decreases in pain intensity in the HYP and MM conditions, relative to the EDU condition. The overall significance level for the test of the null hypothesis that all three treatments have equal effect will be set to 0.05. Pairwise comparisons of the treatment groups will be performed using the Tukey method to compare the relative effects of HYP and MM with each other. [85] In addition to comparing treatment main effects, we will report descriptively the proportion of subjects in each condition who report meaningful clinical improvement. Clinical improvement will be operationalized as described by the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMACT) consensus group,[86] and considered as both 30% and 50% reductions in pain intensity. Additionally, in a review of pain trials, a 2-point difference on the NRS translates to approximately a 30% change in most studies, depending on average baseline levels of pain intensity, and to patient perceptions of “much improvement” on global impression of change measures.[87] We will also look at the proportion of participants in each condition reporting a ≥2 point reduction in pain intensity.

Hypothesis 2 states that baseline EEG activity will predict differential response to HYP and MM, such that those participants who have higher baseline levels of global theta, and lower baseline levels of left frontal gamma will respond to more to HYP, while participants with lower baseline levels of global alpha will respond to more to MM. These moderator hypotheses will be tested using linear regression analysis, with pre- to post-treatment change in pain intensity as the response (criterion) variable. Treatment condition, absolute power of baseline theta, alpha, and (left frontal) gamma, and terms representing the interaction between treatment condition and each EEG bandwidth will be the explanatory variables. Significant Treatment Condition X Theta, Alpha, and Gamma interactions, with higher coefficients for baseline theta and lower coefficients for baseline gamma in the HYP group, and lower coefficient for baseline alpha in the MM group would support Hypothesis 2.

In addition to testing the two study hypotheses, a series of exploratory analyses will be conducted to better understand the effects and potential mechanisms of HYP and MM. To examine the potential effects of HYP and MM relative to EDU on secondary outcomes, ANCOVA analyses will be repeated for each of the secondary outcome variables (i.e., depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, pain interference, PTSD symptoms), controlling for the respective baseline measures of these secondary outcomes. The response variable will be change in each outcome measure score from pre- to post-treatment and will be analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with treatment condition (HYP, MM, ED) as the explanatory variable and the corresponding baseline value for each secondary outcome measure as a covariate. Perceived global improvement is the final secondary outcome measure but unlike the other secondary outcome measures it was not measured at baseline, hence ANOVA will be used to compare perceived global improvement with treatment condition as the independent variable.

Maintenance of benefit at 3- and 6- months post-treatment will be assessed using a Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) approach, which accounts for the correlated nature of the data due to multiple observations of the same person over time. Response variables over time will be the change in average pain intensity (and in the secondary outcomes, each of which will be examined in an independent model) from pre-treatment to post-treatment, and pre-treatment to 3- and 6- months follow-ups, with intervention group and follow-up time as the main factors of interest (including a Group X Time interaction), and the pre-treatment value as the covariate. For the correlation matrix, an unstructured format will be assumed given the absence of a priori reason to use a more structured matrix format.

Mediation Analyses

The goal of mediation analyses is to examine whether group assignment (determined by randomization at baseline) impacts change in pain intensity (primary outcome) from baseline to post-treatment through indirect effects on the hypothesized mediators (measured midway between baseline and post-treatment). Potential mediators have been identified a priori and are shown in the table of measures (Table 4). To evaluate the association between intervention type, potential mediating factors, and change in pain intensity, models with individual mediators will be computed to obtain unadjusted estimates and to estimate the degree of confounding in subsequent multivariate models. Per Hayes & Rockwood’s recommendations,[88] multiple mediators will then be tested in the same model to more accurately reflect the theoretical understanding of parallel biological and psychological mediating processes, and to facilitate comparison of the size of indirect effects through different mediators. Mediators to be included in the model include change in EEG composite scores for theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bandwidths, pain acceptance, catastrophizing, mindfulness, therapeutic alliance, and skill practice. Also per the recommendations of Hayes and Rockwood,[88] bootstrap confidence intervals will be computed for the indirect effects.[88] All mediation analyses will be done using PROCESS®, an add-on to statistical packages.

Moderation Analyses

In this trial, multiple moderators are identified a priori (Table 4). Given the large number of potential moderators and their interactions with treatment, it would not be adequately statistically powerful nor easily interpretable to include all of them in a single model at once. On the other hand, computing separate single-moderator models would not give a realistic picture of how the moderation effects were acting in the population of interest. To address these concerns, several steps will be taken to integrate empirical support (i.e., correlations) with theoretical knowledge to winnow the pool of candidate moderators down to those that are most important. Once the potential moderators have been winnowed to a smaller number, models will be constructed sequentially, by including potential moderators and their interaction with treatment in a forward fashion in the order of statistical significance. Statistically significant Treatment Condition X Moderator interactions would suggest that the impact of the moderator variable on outcome differs as a function of treatment condition. In the absence of interaction, statistically significant main effects for the potential moderators would suggest that they might be associated with the outcome. Given the large number of exploratory moderator analyses proposed, caution will be used in interpreting results, with the goal being of identifying potential moderators to examine more closely in future research.

Power Calculations

The primary study outcome variable is change in average pain intensity, as represented by the difference between the baseline and post-treatment average pain intensity measures. Anticipated effects for HYP are based on the changes observed in our previous HYP trials using the 0–10 NRS measure.[56, 89] Anticipated effect sizes for MM are based on published studies of the effects of treatments that involve mindfulness that used 0–10 NRS measures.[30] Based on these prior findings, assuming a decrease in pain intensity (NRS) score of 0.3 points for the education group, 0.8, 1 and 1.4 for the HYP, and 0.6, 0.8 and 1 for MM, we calculated the sample size to find differences between pre-post treatment difference scores, with an alpha of 0.05, power of 0.80, and varying the standard deviation (SD) from 0.15 to 1 (to cover values observed) when using an ANOVA. Sample sizes of 80 completers per condition (total = 240) were determined to have at least 80% power, even at the largest standard deviation.

Discussion

Chronic pain is a biopsychosocial condition, and mounting evidence supports the efficacy of interventions that target pain from this more holistic perspective.[41, 90] The proposed study will fill an important gap in current literature that is a necessary precursor for more widespread implementation of meditation and hypnosis,[18, 91] particularly in the VA healthcare system. The interventions being tested are needed because: (1) they do not require devices or drugs, and can be used in combination with other treatments; (2) the interventions are non-pharmacological and free of known adverse side-effects; (3) they are appropriate for individuals with complex comorbid conditions, with few contraindications; (4) they can be done independently in a very brief amount of time, once learned. Unlike treatments that require repeated intervention appointments (e.g., acupuncture, massage), once the skills in these interventions are acquired, they can be practiced anytime, anywhere, without the support of a clinician. As such, there is no expiration on the benefits acquired or need for ongoing intensive/burdensome travel of provider requirements. Our preliminary work also suggests that individuals experience continued improvement in skill when practiced over time.

At the broadest level, this study will contribute to the growing evidence base for specific non-opioid treatments. If the primary study hypotheses are supported, the findings will provide the evidence needed to allow for greater access to treatments that would to reduce the pain and suffering among individuals living with chronic pain. The treatments in this study are known to be safe and well-tolerated, hence there are few, if any, risks associated with the proposed study. Additionally, the study findings will provide critical information regarding the mechanisms of HYP and MM, including potential moderators and mediators of each. This study will add a particularly novel approach by integrating EEG data to illuminate brain mechanisms.[37]

This study represents an increase in methodological rigor over several prior studies, by including an active control condition (EDU) matched for time and attention, a more generalized sample (i.e., adults with chronic pain of various types, durations, and etiologies), and a larger sample. This study is thus positioned to provide critical information about whether these treatments work in Veterans as delivered in a VA setting, and which are most effective, which will inform resource allocation and policy-level implementation efforts. Additionally, by examining treatment effect moderators, the study will also examine for whom they are most effective, which will help patients and providers choose treatments that are most likely to be beneficial, thereby optimizing patient-treatment matching and improving efficiency of health services delivery. Importantly, the study will also examine how these interventions work, filling a considerable void in the understanding of mechanisms underlying HYP, MM, and EDU for pain. Such knowledge may advance the theories underlying these psychosocial treatments and lead to the development of more effective interventions. [92]

Though the proposed study has features of an efficacy trial (e.g., standardized administration of intervention), it is more accurately conceptualized as an effectiveness trial, based on its integration within real-world clinical infrastructure, utilization of licensed/credentialed existing providers who have varying levels of expertise in conducting these interventions, and inclusion of non-research participants in the intervention classes. Including non-research participants in the study intervention appointments is a necessary precursor for utilizing clinical infrastructure and will offer several specific benefits: (1) high ecological validity and improved access and logistics; (2) increased enrollment in the intervention classes, thus assisting with achieving “critical mass” and bolstering workload credit for the group facilitators; (3) the opportunity to assess preferences for specific interventions, (4) ethically ensuring participants do not experience coercion. The delivery features of this study will also afford insight into the degree that providers of various professional disciplines can successfully deliver behavioral pain interventions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (Grant # 1R01AT008336-01, awarded to Co-Principal Investigators Mark Jensen, PhD, and Rhonda Williams, PhD). The sponsor did not participate in study design, implementation of any part of the study, or any dissemination decisions or activities. This work was also supported in part with resources and facilities at VA Puget Sound Health Care System and the University of Washington. The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. This trial is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02653664). The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions to the study of our research staff: Ellen Cambron, BA, Nicole Hodgkinson, BA, Katherine Hand, MA, Emma Herbeck, BS, and Genevra Vanhoozer, BA, Ben Korman, MS, Emily Koelmel, BA, Natalie Koh, BS, Makena Kaylor, BA, Emily Stensland, BS.

Abbreviations

- VA

Veterans Affairs

- VAPSHCS

Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System

- HYP

Hypnosis

- MM

Mindfulness Meditation

- EDU

Education Control

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

- CRF

Case Report Form

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy for Traumatic Brain Injury: Evaluating the Evidence. 2013, The National Academies Press: Washingto, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy J, et al. , Prevalence of persistent pain in the U.S. adult population: new data from the 2010 national health interview survey. J Pain, 2014. 15(10): p. 979–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahin RL, Severe Pain in Veterans: The Effect of Age and Sex, and Comparisons With the General Population. J Pain, 2017. 18(3): p. 247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haskell SG, et al. , The prevalence and age-related characteristics of pain in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2006. 15(7): p. 862–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerns RD, et al. , Veterans’ reports of pain and associations with ratings of health, health-risk behaviors, affective distress, and use of the healthcare system. J Rehabil Res Dev, 2003. 40(5): p. 371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lew HL, et al. , Prevalence of chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and persistent postconcussive symptoms in OIF/OEF veterans: Polytrauma clinical triad. J Rehabil Res Dev, 2009. 46 (6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couch JR and Stewart KE, Headache Prevalence at 4–11 Years After Deployment-Related Traumatic Brain Injury in Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan Wars and Comparison to Controls: A Matched Case-Controlled Study. Headache, 2016. 56(6): p. 1004–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaramillo CA, et al. , Subgroups of US IRAQ and Afghanistan veterans: associations with traumatic brain injury and mental health conditions. Brain Imaging Behav, 2015. 9(3): p. 445–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lippa SM, et al. , Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress, 2015. 28(1): p. 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seal KH, et al. , Association of Traumatic Brain Injury With Chronic Pain in Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans: Effect of Comorbid Mental Health Conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2017. 98(8): p. 1636–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federal Pain Research Strategy,. Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee and National Institutes of Health, Editor. 2017: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adachi T, et al. , A meta-analysis of hypnosis for chronic pain problems: a comparison between hypnosis, standard care, and other psychological interventions. Int J Clin Exp Hypn, 2014. 62(1): p. 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkins G, Jensen M, and Patterson DR, Hypnosis for the treatment of chronic pain. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 2007. 55: p. 275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen MP, Hypnosis for chronic pain management: a new hope. Pain, 2009. 146(3): p. 235–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherkin DC, et al. , Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care on Back Pain and Functional Limitations in Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 2016. 315(12): p. 1240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilton L, et al. , Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med, 2017. 51(2): p. 199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeidan F and Vago DR, Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2016. 1373(1): p. 114–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker WC, et al. , A Research Agenda for Advancing Non-pharmacological Management of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: Findings from a VHA State-of-the-art Conference. J Gen Intern Med, 2018. 33(Suppl 1): p. 11–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen MP, et al. , Effects of self-hypnosis training and EMG biofeedback relaxation training on chronic pain in persons with spinal-cord injury. Int J Clin Exp Hypn, 2009. 57(3): p. 239–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brugnoli MP, et al. , The role of clinical hypnosis and self-hypnosis to relief pain and anxiety in severe chronic diseases in palliative care: a 2-year long-term follow-up of treatment in a nonrandomized clinical trial. Ann Palliat Med, 2018. 7(1): p. 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson T, et al. , The effectiveness of hypnosis for pain relief: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 85 controlled experimental trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2019. 99: p. 298–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yapko M, Hypnosis in treating symptoms and risk factors of major depression. Am J Clin Hypn, 2001. 44(2): p. 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker PM, Hypnosis in the Management of Sleep Disorders. Sleep Med Clin, 2015. 10(1): p. 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chamine I, Atchley R, and Oken BS, Hypnosis Intervention Effects on Sleep Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Clin Sleep Med, 2018. 14(2): p. 271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Toole SK, Solomon SL, and Bergdahl SA, A Meta-Analysis of Hypnotherapeutic Techniques in the Treatment of PTSD Symptoms. J Trauma Stress, 2016. 29(1): p. 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotaru TS and Rusu A, A Meta-Analysis for the Efficacy of Hypnotherapy in Alleviating PTSD Symptoms. Int J Clin Exp Hypn, 2016. 64(1): p. 116–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen MP, et al. , Satisfaction with, and the beneficial side effects of, hypnotic analgesia. Int J of Clin and Exp Hyp, 2006. 54(4): p. 432–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen MP, et al. , Long-term outcome of hypnotic-analgesia treatment for chronic pain in persons with disabilities. Int J of Clin and Exp Hyp, 2008. 56(2): p. 156–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day MA and Thorn BE, Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for headache pain: An evaluation of the long-term maintenance of effects. Complement Ther Med, 2017. 33: p. 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bawa FL, et al. , Does mindfulness improve outcomes in patients with chronic pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract, 2015. 65(635): p. e387–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helmes E and Ward BG, Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for anxiety symptoms in older adults in residential care. Aging Ment Health, 2017. 21(3): p. 272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen SR, et al. , Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on sleep quality: results of a randomized trial among Danish breast cancer patients. Acta Oncol, 2013. 52(2): p. 336–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schramm PJ, et al. , Sleep quality changes in chronically depressed patients treated with Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy or the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy: a pilot study. Sleep Med, 2016. 17: p. 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wurtzen H, et al. , Mindfulness significantly reduces self-reported levels of anxiety and depression: results of a randomised controlled trial among 336 Danish women treated for stage I-III breast cancer. Eur J Cancer, 2013. 49(6): p. 1365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Jong M, et al. , Effects of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy on Body Awareness in Patients with Chronic Pain and Comorbid Depression. Front Psychol, 2016. 7: p. 967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisendrath SJ, et al. , A Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Psychother Psychosom, 2016. 85(2): p. 99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen MP, Adachi T, and Hakimian S, Brain Oscillations, Hypnosis, and Hypnotizability. Am J Clin Hypn, 2015. 57(3): p. 230–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lomas T, Ivtzan I, and Fu CH, A systematic review of the neurophysiology of mindfulness on EEG oscillations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2015. 57: p. 401–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dienes Z and Hutton S, Understanding hypnosis metacognitively: rTMS applied to left DLPFC increases hypnotic suggestibility. Cortex, 2013. 49(2): p. 386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Day MA, et al. , Toward a theoretical model for mindfulness-based pain management. J Pain, 2014. 15(7): p. 691–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen MP, et al. , Mechanisms of hypnosis: toward the development of a biopsychosocial model. Int J Clin Exp Hypn, 2015. 63(1): p. 34–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen MP, Day MA, and Miro J, Neuromodulatory treatments for chronic pain: efficacy and mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol, 2014. 10(3): p. 167–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen MP, Ehde DM, and Day MA, The Behavioral Activation and Inhibition Systems: Implications for Understanding and Treating Chronic Pain. J Pain, 2016. 17(5): p. 529 e1–529 e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen MP, et al. , New directions in hypnosis research: strategies for advancing the cognitive and clinical neuroscience of hypnosis. Neurosci Conscious, 2017. 3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazdin AE, Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychother Res, 2009. 19(4–5): p. 418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]