Abstract

This is an extensive review on epiphytic plants that have been used traditionally as medicines. It provides information on 185 epiphytes and their traditional medicinal uses, regions where Indigenous people use the plants, parts of the plants used as medicines and their preparation, and their reported phytochemical properties and pharmacological properties aligned with their traditional uses. These epiphytic medicinal plants are able to produce a range of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, and a total of 842 phytochemicals have been identified to date. As many as 71 epiphytic medicinal plants were studied for their biological activities, showing promising pharmacological activities, including as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer agents. There are several species that were not investigated for their activities and are worthy of exploration. These epipythes have the potential to furnish drug lead compounds, especially for treating cancers, and thus warrant indepth investigations.

Keywords: epiphytes, medicinal plants, phytochemistry, pharmacology, drug leads

1. Introduction

Epiphytes are plants that grow on other plants and are often known as air plants. They are mostly found in moist tropical areas on canopy tree-tops, where they exploit the nutrients available from leaf and other organic debris. These plants exist within the plantae and fungi kingdom. The term epiphyte itself was first introduced in 1815 by Charles-François Brisseau de Mirbel in “Eléments de physiologie végétale et de botanique” [1]. Epiphytes can be categorized into vascular and non-vascular epiphytic plants; the latter includes the marchantiophyta (liverworts), anthocerotophyta (hornworts), and bryophyta (mosses). The common epiphytes are mosses, ferns, liverworts, lichens, and the orchids. Epiphytes fall under two major categories: As holo- and hemi-epiphytes. While orchids are a good example of holo-epiphytes, the strangler fig is a hemi-epiphyte. Although geological studies have proposed the existence of epiphytes since the pleistone epoch, an epiphyte was first depicted in “the Badianus Manuscript” by Martinus de la Cruz in 1552, which showed the Vanilla fragrans, a hemi-epiphytic orchid, being used by the tribal communities in latin America for fragrance and aroma, usually hung around their neck [1].

Epiphytes have been a source of food and medicine for thousands of years. Since they grow in a unique ecological environment, they produce interesting secondary metabolites that often show exciting biological activities. There are notable reviews on non-vascular epiphytes, bryophyta, regarding their phytochemical and pharmacological activities [2,3,4,5]. There are also extensive reviews on epiphytic lichens covering secondary metabolites and their pharmacological activities [6,7,8,9]. The only available review on vascular epiphytes related to medicinal uses was focused on Orchidaceae [10]. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, there is no extensive database of vascular epiphytes regarding their medicinal contribution.

There are 27,614 recorded species of vascular epiphytes belonging to 73 families and 913 genera [11]. Vascular epiphyte species are commonly found in pteridophyta, gymnosperms, and angiosperms plant groups, which are mostly found in the moist tropical areas on canopy tree tops, where they exploits the nutrients available from leaf and other organic debris [12,13]. In this study, information on vascular epiphytic medicinal plant species was collected using search engines (Web of Science, Scifinder Scholar, prosea, prota, Google scholar), medicinal plant books (Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Medicinal and Poisonous Plants [14,15,16], Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Cryptogams: Ferns and Fern Allies [17], Mangrove Guide for South-East Asia [18], Medicinal Plants of the Asia-Pacific [19], Medicinal Plants of the Guiana [20], Indian Medicinal Plants [21,22], Medicinal Plants of Bhutan [23], Medicinal and aromatic plants of Indian Ocean islands: Madagascar, Comoros, Seychelles and Mascarenes [24]), and the Indonesian Medicinal Plants Database [25]. Scientific names of the epiphytic medicinal plant species were compared against the Plantlist database for accepted names to avoid redundancy [26]. The time-frame threshold for data coverage was from the earliest available data until early 2020. Nevertheless, empirical knowledge regarding traditional medicinal plants was passed through generations using verbal or written communication, with verbal communication highly practiced by remote tribes [27,28]. It is possible that some oral traditional medical knowledge may not be reported and therefore not captured in this review. In this current study, we collected and reviewed 185 epiphytic medicinal plants reported in the literature, covering ethnomedicinal uses of epiphytes, their phytochemical studies and the pharmacological activities. The data collection approach used is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic data collection approach.

2. Ethnopharmacological Information of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants

2.1. Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species Distribution within Plant Families

In this component of the study, we collated and analysed 185 of the medicinally used epiphytic plants species using ethnopharmacological information. This data (Table 1) includes the name of species, plant family, areas where the epiphytes are used in traditional medicines, part(s) of the plant being used in medication, how the medicine was prepared, and indications. Of the 185 medicinally used epiphytes, 53 species were ferns (mostly polipodiaceae), with 132 species belonging to the non-fern category. The Orchidaceae family contains the Dendrobium genus that contains the highest number of medicinal epiphytes, including 64 orchid species and 20 Dendrobium species. The Orchidaceae epiphytes were the majority of non-fern epiphytes. Cassytha filiformis L, Bulbophyllum odoratissimum (Sm.) Lindl. ex Wall., Cymbidium goeringii Rchb.f.) Rchb.f., Acrostichum aureum Limme, and Ficus natalensis Hochst. were the five most popular vascular epiphytic medicinal pants used (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Ethnopharmacological database of epiphytic medicinal plants.

| No | Epiphyte Species | Location | Part of Plants | Preparation and Route of Administration | Indication (traditional) | Pharmacological Testing (modern) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fern species | ||||||

| Adiantaceae | ||||||

| 1 | Adiantum caudatum L. | India, Indonesia, Malaysia | LF | Decoction | Cough, heal wound, cold, tumors of spleen, liver and other viscera, skin diseases, bronchitis, and inflammatory diseases [40,49,50] | Antimicrobial (MeOH extract, gram +, -, fungi) [40] |

| Aspleanceae | ||||||

| 2 | Asplenium nidus L. | Tahiti, Malaysia, Philippines, Vanuatu, Indonesia | LF, WP | Ointment, decoction, eaten | Headache, hair loss (pounded leaves mixed with coconut oil), ease labor, fever (decoction), contraceptive, depurative, sedative agents. edible food (young leaves), ornament, anti-inflammation, promote blood circulation [51,52,53] | Antioxidative (MeOH extract, DPPH), tyrosinase inhibiting (MeOH extract, microtitre), antibacterial (MeOH extract) [44] |

| 3 | Asplenium macrophyllum Sw. | India | LF | Decoction | As laxative, emetic, diuretic, anthelmintic agent, to treat ophthalmia, jaundice, spleen diseases [52,54] | |

| 4 | Asplenium polydon G. Foster var bipinnatum (Sledge) | India | LF | Decoction, paste | Promote labor, tumor [55] | |

| 5 | Asplenium serratum L. | Columbia, Peru | na | Not mentioned | Liver problem, stomachache, ovary inflammation [52,56] | |

| Blechnaceae | ||||||

| 6 | Stenochlaena palustris (Burm. F.) Bedd. | Indonesia, India | LF, RZ | Eaten, decoction, poultice | Young reddish leaves are used as food, leaves are used to treat fever, skin diseases, throat, and gastric ulcer, as antibacterial, rhizome and leaves are used to treat burns and ulcers, as cooling agent [18,57] | |

| Davalliaceae | ||||||

| 7 | Davallia denticulata (Burm. f.) Mett. ex Kuhn | Malaysia, Indonesia | RT | Decoction | Gout, pain, as tonic [49,58] | |

| 8 | Araiostegia divaricata (Blume) M. Kato | China, Taiwan | WP | Not mentioned | Joint pain [59] | Anti-psoriasis [60], antioxidant (water extract, DPPH) [61] |

| 9 | Davallia parvula Wall. Ex Hook. & Grev. | na | Not mentioned | Not mentioned [18,62] | ||

| 10 | Davallia solida (G. Forst.) Sw. | Tahiti, Fiji, other Polynesian | WP | Decoction (external and internal) | Dysmennorrhea, luochorea, uterine hemorrhage, sore throat, asthma, constipation, fracture, fish sting, promote health pregnancy, as a bath for newborn, anti-microbial [53,63,64,65] | Antioxidant (extract, ABTS) [61], antioxidant (DPPH, all isolates) [66], anti-neurotoxicity (extract, (Neuro-2a cells, ATCC CCL-131) [67], C-terminal cytosolic domain of P-pg [68], anti-skin aging [69] |

| 11 | Leucostegia immersa Wall. ex C. Presl | Nepal | RZ | Decoction, paste | Boils (paste), constipation (decoction), as antibacterial (paste) [70] | |

| Gesneriaceae | ||||||

| 12 | Aeschynanthus radicans Jack | Malaysia | LF | Decoction | Headache [19] | |

| 13 | Cyrtandra sp | Indonesia | LF | Poultice | Skin ailments [71] | |

| Hymenophyllaceae | ||||||

| 14 | Hymenophyllum polyanthos Sw. | Suriname | WP | Burnt (smoke inhaling), decoction | Dizziness (insanity), pain, cramps [72] | |

| 15 | Hymenophyllum javanicum Spreng. | India | WP | Smoke together with garlic and onions | Headache [55] | |

| Lycopodiaceae | ||||||

| 16 | Huperzia carinata (Desv. ex Poir.) Trevis | South-East Asia | WP | Ointment | Stimulate hair growth [73] | Anti-acetylcholinesterase (74, 75, 76, colorimetric Ellman method) [74] |

| 17 | Huperzia phlegmaria (L.) Rothm | South-East Asia, India | WP | Ointment | Stimulate hair growth, skin diseases [75,76] | Cytotoxic activities against HuCCA-1, A-549, HepG2, and MOLT-3 cancer cell lines (81, 79, 77) [77] |

| 18 | Huperzia megastachya (Baker) Tardieu | Madagascar | LF | Decoction (infusion) | Tonic [78] | |

| 19 | Huperzia obtusifolia (Sw.) Rothm. | Madagascar | LF | Decoction (infusion) | Tonic [78] | |

| Nephrolepidaceae | ||||||

| 20 | Nephrolepis acutifolia (Desv.) Christ | Malaysia | WP | Boiled, eaten | Food [79] | |

| 21 | Nephrolepis biserrata (Sw.) Schott | Malaysia, Indonesia, Ivory Coast, New Guinea | LF, RZ, WP | Decoction, cooked | Leaves are used to treat boils, blister, abscesses, sores, and cough. Rhizomes are used as edible food [80,81] | Antibacterial (extract) [82] |

| Oleandraceae | ||||||

| 22 | Nephrolepis cordifolia (L.) C. Presl | India | RZ | Decoction (fresh leaves) | Cough, rheumatism, chest congestion, nose blockage, loss appetites, infection (antibacterial), pinnae is used to treat cough, wounds, jaundice, anti-fungal, styptic, anti-tussive [57] | Antibacterial, anti-fungal (extract fractions aerial part) [83] |

| 23 | Oleandra musifolia (Blume) C. Presl | Philippines, India | ST | Decoction | Anthelmintic, emmenagogue, antidote (snake bite) [70,84] | |

| Opioglossaceae | ||||||

| 24 | Botrychum lanuginosum Wall.ex Hook & Grev. | India | WP | Decoction, paste | Antibacterial, anti-dysentery agents [57] | |

| 25 | Ophioglossum pendulum L. | Indonesia, Philippines | LF | Ointment, decoction. | Hair treatment (crushed leaves), cough (decocotion), rid the first feces (spores), ornament [85] | Cell activator, skin whitening agent and antioxidant (patent, mixed with other Ophioglossum species) [86], anti-diarrhea (stipe MeOH extract, rabit jejenum) [86] |

| Polypodiaceae | ||||||

| 26 | Pyrrosia piloselloides (L.) M.G. Price | Indonesia, Malaysia, China, Philippines, Pacific islands | LF | Decoction (internal), chewed, poultice (external) | Smallpox, rashes, gonorrhea, dysentery, tuberculosis, urinary tract infection, headache, cough, gum inflammation, tooth sockets, eczema, coagulate blood [87,88,89,90] | Antibacterial, anti-fungal (extracts) [91] |

| 27 | Drynaria rigidula (Sw.) Bedd. | Indonesia, Philippines, Treasury Island | LF, RZ | Decoction, chewing | Gonorrhea, dysentery (rhizome, decoction), and seasickness (chewed) [21] | n-Hexane, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate fractions from both rhizome and leaves of Drynaria rigidula were screened for activity against Plasmodium falciparum, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, vero cells and herpes simplex virus which all extracts showed insignificant activities [92] |

| 28 | Drynaria sparsisora (Desv.) T. Moore | Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand | LF, RZ | External, decoction | Rhizome: headache, fever, diarrhea, gonorrhea, swollen limbs, fever. Leaves: anti-vomiting, snake bite, eye infection [21,71,93] | |

| 29 | Drynaria roosii Nakaike | China | WP | Decoction | Deficient kidney, invigorate blood, heal wound, stop bleeding [21] | Compound 230 was isolated and the biotesting showed the highest stimulation toward UMR 106 cells (osteoblast) by 42.6% at a concentration of 1 µM [94] |

| 30 | Drynaria propinqua (Wall. ex Mett.) Bedd | Bhutan, India and Nepal | ST | Pills | Antidote and detoxifier especially when suffering from meat poisoning and other human-made poisons (sbyar-dug) [95] | |

| 31 | Drynaria quercifolia (L.) J.Sm. | Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, India | LF, RZ | Decoction, poultice | Swelling, fever (poultice leaves), haemoptysis, typhoid fever, ulcers, dyspepsia, artharlgia, diarrhea (decocted rhizome), inflammation, anthelmitic, cough, fever, phthisis, poultice of rhizome mixed with Lannea coromandelica (Houtt.) Merr.) to treat headache, hepatoprotective agent [21,22,96] | Compound 200 from the ethyl acetate fraction to be responsible for good antimicrobial activity [97] |

| 32 | Lepisorus contortus (Christ) Ching | Bhutan, India, China | LF | Powder | Heals bone fracture, burns, wounds and kidney disorders [98] | |

| 33 | Loxogramme involuta (D. Don) C. Presl | Indonesia | LF, WP | Smoked | Smoked with tobacco [18] | |

| 34 | Loxogramme scolopendria (Bory) Presley | Indonesia | LF | Smoked | Cigarette paper [99] | |

| 35 | Microsorum fortunei (T. Moore) Ching | Indonesia | WP | Decoction | Diuretic, promote blood circulation [49,51] | |

| 36 | Microsorum punctatum (L.) Copel. | India | LF | Juice | Diuretic, purgative, wounds [70] | |

| 37 | Phlebodium aureum (L.) J.Sm | Mexico | RZ | Decoction | Cough, fever, sudorific agents [57] | |

| 38 | Phymatosorus scolopendria (Burm. f.) Pic. Serm. | South-East Asia, Madagascar | RZ | Fragrance (external), poultice, decoction | Fragrance, gecko bites, accelerate childbirthRespiratory disorder [18,47] | Bronchodilator (341, in-vivo) [47] |

| 39 | Platycerium coronarium (Mull.) Desv. | Indonesia | LF | Poultice (salt added) | Thyroid edema, scabies [18,100] | |

| 40 | Platycerium bifurcatum (Cav.) C. Chr. | Indonesia | LF | Poultice (salt added) | Thyroid edema, scabies, fever, swelling [100,101] | |

| 41 | Pleopeltis macrocarpa (Bory ex Willd.) Kaulf. | South-Africa, Mexico, Guatemala | LF, RZ | Decoction | Sore throat, itches, cough, febrifuge [70,102] | |

| 42 | Pyrrosia heterophylla (L.) M.G. Price | India | WP | Poultice | Swelling, sprain, pain (cooling agent) [103] | |

| 43 | Pyrrosia lanceolata (L.) Farw. | Malaysia, South-Africa, Mexico | LF, WP | Juice, poultice, decoction | Dysentery, headache, colds, sore throats, itch guard [55,87] | |

| 44 | Pyrrosia lingua (Thunb.) Farw. | Japan, China, Indonesia, Pacific Islands | LF, WP | Decoction | Diuretic, anti-inflammation, analgesic, cough, stomachache, urinary disorder (diuretic agent) [87,104,105,106] | Antioxidant [107], inhibition effects on virus-induced CPE when SARS-CoV strain BJ001 [108] |

| 45 | Pyrrosia longifolia (Burm. f.) C.V. Morton | Indonesia, Pacific Islands | LF | Poultice (cold water) | Ease pains in labor [18,87] | |

| 46 | Pyrrosia petiolosa (Christ) Ching | China | WP | Decoction | Urinary tract infections, as diuretic [109] | |

| 47 | Pyrrosia sheareri (Baker) Ching | China | LF | Decoction | Bacillary dysentery, rheumatism [87,110] | Antioxidant [110] |

| Psilotaceae | ||||||

| 48 | Psilotum nudum (L.) P. Beauv. | India | LF, SP | Fresh, decoction | Diarrhea (infants), antibacterial, purgative [55] | |

| Pteridaceae | ||||||

| 49 | Acrostichum aureum L. | South-East Asia, Bangladesh, Fiji, China, Panama | LF, RZ | Eaten, decoction | Wounds, peptic ulcers and boils, worm infections, asthma, constipation, elephantiasis, febrifuge, chest pain, emollients [18,35] | Anti-implantation (EtOH extract, albino rats) [111], Anti-tumour (hella cells, MTT assay) [112], Antioxidant (DPPH), tyrosine inhibition (96-well microtitre), antibacterial activity [44,113], anti-cancer ((gastric: AGS; colon: HT-29 and breast: MDA-MB-435S) using the MTT assay) [114] |

| 50 | Acrostichum speciosum Willd. | South-East Asia | Thatch [18] | |||

| 51 | Taenitis blechnoides (Willd.) Sw. | Malaysia | LF | Decoction | Postnatal protection [115] | |

| Selaginellaceae | ||||||

| 52 | Selaginella tamariscina (P.Beauv.) Spring | Nepal | WP, SP | Fresh (spore), decoction | Vermilion powder, prolapsed rectum, cough, bleeding piles, amenorrhea, antibacterial [57,116] | Anti-acne [117], thymus growth-stimulatory activity in adult mice (reversal of involution of thymus) and remarkable anti-lipid peroxidation activity [118] |

| Vittariaceae | ||||||

| 53 | Vittaria elongata Sw. | South-East Asia, Andaman | LF | Decoction | Rheumatism [57] | Cytotoxicity against two human cancer cell lines, lung carcinoma (NCI-H460) and central nervous system carcinoma (SF-268), antioxidant (DPPH) [119] |

| Non-Fern | ||||||

| Araceae | ||||||

| 54 | Philodendron fragrantissimum (Hook.) G.Don | Guyana, Suriname, Brazil | LF, RT | Decoction, external (leaves) | Inflammation, aphrodisiac, demulcent, diuretic [72] | |

| Aralliaceae | ||||||

| 56 | Schefflera caudata (Vidal) Merr. & Rolfe | Philippines | WP | Decoction | Tonic for women after birth [120] | |

| 57 | Schefflera elliptica (Blume) Harms. | South-East Asia, China, India | BK, LF, RT | Decoction, chewed, external | Bechic, vulnerary, toothache, aromatic bath, dropsy [120]. | Antibacterial [121] |

| 58 | Schefflera elliptifoliola Merr. | Philippines | LF | Decoction | Tonic for woman after birth [120] | |

| 59 | Schefflera oxyphylla (Miq.) R.Vig. | Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia | RT | Decoction | Sedative for frightened child, externally to treat fevers [120] | |

| 60 | Schefflera simulans Craib | Thailand, Malaysia | LF, RT | Decoction | Stomach problem, protective medicine after birth [120] | |

| Asclepiadaceae | ||||||

| 61 | Asclopidae sp. | Indonesia | LF, RT | Decoction | Promote blood circulation [71] | |

| 62 | Dischidia acuminata Costantin | Vietnam | WP | Decoction | Blenorrhoea, promote urination [19] | |

| 63 | Dischidia bengalensis Colebr. | Thailand | LT, RT | Latex (external), decoction (tonic) | Anthemintic (ringworm), tonic [122] | |

| 64 | Dischidia imbricata (Blume) Steud. | Indonesia | LF | Poultice | Gonorrhea, burns and wounds [25,123] | |

| 65 | Dischidia major (Vahl) Merr. | India, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei | LF, RT, WP | Decoction, chrused (external), chewed with areca catechu | Peptic ulcer, liver dysfunction (decocted leaves mixed with Hoya kerii Craib leaves and Vanilla aphylla Blume stem), fever (root), goiter (crushed leaves mixed with salt), cough (root mixed betel quid), wound and injuries, stomache [19,124,125] | |

| 66 | Dischidia nummularia R.Br. | Thailand, Indonesia | LF, LT, WP | Decoction, latex (external) | Wound, gonorrhea, sprue in children, cirrhosis [126] | |

| 67 | Dischidia platyphylla Schltr | Philippines | LF | Decoction | Putrefaction [19] | |

| 68 | Dischidia purpurea Merr. | Philippines | LF | Crushed leaves mixed with coconut oil applied as external poultice | Eczema, herpes [19,127] | |

| 69 | Toxocarpus sp. | Indonesia | LF | Decoction | Headache, fever, nervous system problem [71] | |

| Balsaminaceae | ||||||

| 70 | Impatiens niamniamensis Gilg (semi epiphytic) | Congo | LF | Poultice | Wounds, sores, pain [128] | Anti-hyperglicemic (Rat) [129] |

| 71 | Convolvulaceace (parasite) | |||||

| 72 | Cassytha filiformis L | India, Taiwan, China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Fiji, Africa, Central America. | WP, NT | Decoction | Cough, dysentery, diarrhea, intestinal problems, headache, malaria fever, nephritis, edema, hepatitis, sinusitis, gonorrhea, syphilis, skin ulcer, eczema, prevent haemoptysis. Parasite skin and scalp. Induce lactation (after still birth), promote hair growth, diuretic, vermifuge, laxative agent, saliva blood removal (childbirth) [19,130,131,132] | An α1-adrenoceptor antagonist (Rat thoracic aorta) [133], antiplatelet and vasorelaxing actions (Rabit platelet, aortic contraction) [134], anti-trypanosomal, citotoxicity [135], antioxidant [136] |

| 73 | Cuscuta australis R.Br. | Indonesia, Vietnam, China | WP, SD | Decoction, poultice | Whole plant: emollient, sedative, sudorific and tonic agents, urinary complaint. The seeds: sedative agent, diabetes, cornea opacity, acne, dandruff [137]. | Cytotoxicity, antioxidant activity, and inhibitory effects on tyrosinase activity and melanin biosynthesis were estd. by using melanoma Clone M-3 [138] |

| 74 | Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. | India | WP | Decoction, poultice | Mixed with the twigs of Vitex negundo L. applied as fomentation on the abdomen of kwarsiokor children, fever, itchy [139,140] | Anti-viral [141,142], anti-HIV [143], analgesic, relaxant (ether extract) [144], antisteroidogenic activity (MeOH extract) [141], antibacterial activity [145], hair growth activity in androgen-induced alopecia [146], anti-inflammatory (murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7), anti-cancer (Hep3B cells by MTT assay) [147], antioxidant (etOAc extract, DPPH), anti-obesity (EtOAc extract) [148] |

| Clusiaceae | ||||||

| 75 | Clusia grandiflora Splitg. (hemi epiphyte) | Guyana, Suriname | RT | Decoction | Aphrodisiac [72] | Antibacterial [149] |

| 76 | Clusia fockeana Miq. (hemi epiphyte) | Guyana, Suriname | ST(Exudate) | Poultice | Snake bites, ulcers [72] | |

| Gesneriaceae | ||||||

| 77 | Columnea nicaraguensis Oerst. | Panama | ST, LF, WP | Decoction, maceration | Fever [150] | |

| 78 | Columnea sanguinolenta (Klotzsch ex Oerst.) Hanst. | Panama | ST, LF | Decoction | Dysmenorrhea [150] | |

| 79 | Columnea tulae Urb. var. tomentulosa (C.V. Morton) B.D. Morley | Panama | ST | Decoction | Fever [150] | |

| 80 | Drymonia serrulata (Jacq.) Mart. | Amazon | na | Not mentioned | Eczema [151] | Analgesic, anti-inflammatory [152] |

| 81 | Drymonia coriacea (Oerst. ex Hanst.) Wiehler | Amazon | na | Not mentioned | Toothache [151] | |

| Loganiaceae | ||||||

| 82 | Fagraea auriculata Jack. (semi epiphyte) | Indonesia | ST | Stem for stick [25] | Anti-inflammatory [153] | |

| Loranthaceae (parasite) | ||||||

| 83 | Amyema bifurcata (Benth.) Tiegh. | Australia | ST, LF | Decoction | Colds, fever, sores [154] | |

| 84 | Amyema quandang (Lindl.) Tiegh. | Australia | LF | Decoction | Fever [155] | |

| 85 | Amyema maidenii (Blakely) Barlow | Australia | FT | Decoction | Inflammation in the genital regions [156] | |

| 86 | Dendrophthoe falcata (L.f.) Ettingsh | India | WP | Decoction | Pulmonary tuberculosis, asthma, menstrual disorders, swellings, wounds, ulcers, strangury, renal and vesical calculi, aphrodisiac, astringent, narcotic, diuretic [157]. | Wound healing activity was studied, antimicrobial activity and antioxidant activity [158] |

| 87 | Dendrophthoe frutescens L. | Indonesia | LF, WP | Drink (decoction) | Anti-inflammation, antibacterial [51] | |

| 88 | Dendrophthoe incarnata (Jack) Miq. | Malaysia | LF | Poultice | Mixed with Curcuma longa L and rice to make poultice to treat ringworm [159] | |

| 89 | Dendrophthoe pentandra (L.) Miq. | Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam | LF, WP | Poultice, decoction | Sores, ulcers, other skins infections, protective medicine after childbirth, cough, hypertension, cancer, diabetes, tonsil problem [18,25,159,160] | Antioxidant (MeOH extract, DPPH), Tyrosinase activity [160] |

| 90 | Taxillus umbellifer (Schult. f.) Danser | Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam | RT, LF | Decoction drink, poultice | Fever, headache, wounds [159] | |

| 91 | Erianthemum dregei (Eckl. & Zeyh.) Tiegh. | Southern & Eastern Africa | BK | Mixed with milk | Powdered mixed with milk to treat stomach problems in children [161] | |

| 92 | Loranthus globosus Roxb | Malaysia, Indo-China | LF, ST, FT | Poultice (leaves), juice | Headache, expel afterbirth, cough [162] | Antimicrobial, cytotoxicity (brine shrimp) [163], toxicity (Evan’s rat) [164] |

| 93 | Loranthus spec div. | Indonesia | WP | Poultice, decoction | Ariola, varicella, diarrhea, ankylostomiasis, morbilli (gabag), cancer [25] | |

| 94 | Macrosolen robinsonii (Gamble) Danser | Vietnam | LF | Decoction | Enlarged abdomen (diuretic tea) [165] | |

| 95 | Macrosolen cochinchinensis (Lour.) Tiegh. | Malaysia, Indo-China | ST, LF | Decoction, juice, poultice | Expel after birth, headache, cough [165] | |

| 96 | Scurrula atropurpurea (Blume) Danser | Indonesia, Philippines | LF, ST, WP | Decoction | Mouthwash (gargled), cancer (breast, throat cancer), cowpox, chickenpox, diarrhea, hookworm, measles, hepatitis, and cancer [166,167,168] | Cancer cell invasion inhibitory effects [169,170] |

| 97 | Scurrula ferruginea (Jack) Danser | Malaysia | LF, WP | Decoction, poultice | Decocted whole plant (mixed with Millettia sericea (Vent.) Wight & Arnott) is used as bathing to relieve malaria, decocted leaves as protective medicine after childbirth, pounded leaves to treat wounds, snake bites [166] | Antiviral (HSV-1 and poliovirus) and cytotoxic activities on murine and human cancer lines (3LL, L1210, K562, U251, DU145, MCF-7) [171] |

| 98 | Scurrula parasitica L. | China, Vietnam | WP | Decoction | Swelling, back pains, numbness, soreness of limbs, hypertension, galactagogue, quieting uterus (no contraction), reducing lumbago, bone strengthening. [166] | Anti-cancer (flavonoids extract, Leukimia cell line HL-60) [172], NF-κB inhibition [173], recovery of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity [174], Antioxidant (extracts, DPPH) [175] anti-cancer (Polysacharide fraction, S180, K562 and HL-60 cell lines, MTT assay) [176], anti-obesity activity using porcine pancreatic lipase assay (EtOH extract, PPL; triacylglycerol lipase, EC 3.1.1.3)[177], neuroprotective activity (168, H2O2-induced oxidative damage in NG108-15 cells)[178], antibacterial (EtOH extract, MRSA) [179] |

| 99 | Viscum aethiopicum [sic] | Southern & Eastern Africa | LF | Decoction (tea) | Diarrhea [161] | |

| 100 | Viscum capense L.f. | Southern & Eastern Africa | ST, FT | Decoction, external | Wart, asthma, irregular menstruation, hemorrhage [161] | Antimicrobial activity (stems extract), Anticonvulsant activity (MeOH extract, albino mice) [180] |

| 101 | Viscum pauciflorum L.f. | Southern & Eastern Africa | WP | Decoction | Astringent [161] | |

| 102 | Viscum rotundifolium L.f. | Southern & Eastern Africa | WP | External | Wart [161] | Immunoassay (stem, aqueous extracts, T cell activity in ruminants) [181] |

| Melastomataceae | ||||||

| 103 | Medinilla radicans Blume | LF, RT | Leaves eaten to treat dysentery, adventitious roots applied as poultice to wound, young leaves to skin disorders | Dysentery, wound and skin disorders [123] | ||

| 104 | Pachycentria constricta (Bl) Blume | Indonesia | TB | Tubers are boiled and eaten | Hemorrhoids [18,71] | |

| Moraceae | ||||||

| 105 | Ficus annulata Blume | Indonesia | LF, RT | Leaves decoction to treat fever, the root to treat Hansen diseases | Fever and Hansen diseases [168] | |

| 106 | Ficus deltoidea Jack | Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand | LF, RT, FT | Drink (decoction), oitment | Leucorrhea, headache, fever, diabetes, high blood pressure, skin infection, aphrodisiac agent, ornament [71,182,183,184] | Toxicity (aqueous extract, rats) [185], anti-nociceptive [186], antioxidant (leaves aqueous extracs, redn. power of iron (III), superoxide anion (O2-) scavenging, xanthine oxidase (XOD), nitric oxide (NO·) and lipid peroxidn) [187], anti-melanogenic effect (extract, B16F1 melanoma cells, MTT assay) [188], anti-cancer [189], hypoglycemic activity (extract, rodents) [45,188] antimicrobial activity (extract) [190], Anti-inflammatory [191] |

| 107 | Ficus lacor Buch.-Ham. | India | BK, LT, BD, SD | Decoction, poultice | Decocted stem bark to treat gastric and ulcer, latex to treat boils (external), typhoid and fever (internal), decocted bud to treat ulcer, leucorrhoea, Seed as tonic for stomach disorder [157,192,193,194] | The medicated liquor has effects of relaxing muscles and tendons, activating collateral flow, promoting blood circulation, dispelling blood stasis, expelling wind, removing dampness, and relieving pain [195] |

| 108 | Ficus natalensis Hochst. (semi epiphytic, secondary terrestrial) | Uganda, Tanzania, Senegal, West Africa, South Africa, | LF, LT, RT, BK | Decoction, poultice | Root was used to treat lumbago, headache, arthritis, cataract and cough, Leaves were used to treat snakes bite, malaria, dysentery, ulcers, wounds and used as septic ears [196] | Antibacterial, antimalarial, and/or antileishmania activities were obsd. in some crude extracts., and five of these exts. showed a significant cytotoxicity against human tumor cells [41] |

| 109 | Ficus parietalis Blume | Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia | RT | Decoction | Stomach-ache [184] | |

| 110 | Ficus pumila L. | Vietnam | FT, LF, LT | Drink (decoction) | Diarrahea, hemaroid, rheumatic, anemia, haematura, dysentery, dropsy, galactoge, tonic for impotence, lumbago, anthelmintic agent, externally used to treat carbuncles [184] | Against T-cell leukemia [197], antimicrobial [198] |

| 111 | Poikilospermum suaveolens (Blume) Merr. | Indonesia, Thailand | BK | Decoction | Water from the stem for drink, aide the secretion of waste products from the vagina, pain, numbness, stomach ulcer [25,199,200] | Anti-viral (MeOH extract) [201] |

| Orchidaceae | ||||||

| 112 | Acampe carinata (Griff.) Panigrahi | Himalaya, Nepal | WP | Decoction | Rheumatism, sciatica, neuralgia, beneficial in secondary syphilis and uterine diseases [202] | |

| 113 | Acriopsis liliifolia (J.Koenig) Seidenf. | Malaysia | LF, RT | Decoction of the roots and leaves | Fever [203] | |

| 114 | Anoectochilus formosanus Hayata | Taiwan | WP | Decoction | Fever, anti-inflammatory agent, diabetes, liver disorder, chest and abdominal pain [204] | Anti-inflammatory (water extract, rat paw), hepatoprotective (water extract, rat, SGOT-OPT) [205], anti-hyperliposis (414, rat induced) [206], ameliorative effect (water extract, ovariectomised rat) [207], antioxidant (water extract, DPPH) [208], anti-hyperglycemic (water extract, diabetic rats induced by streptozotocin) [209], anti-cancer (extracts, breast cancer MCF-7 cell) [210], liver regeneration (extract, rat) [211,212], Hepatoprotective (414, CCl4 induced rat) anti-inflammatory (414, lps stimulate mice) [213,214], anti-cancer (polysaccharide water extract, protate cancer cell lin PC3) [215] |

| 115 | Anoectochilus roxburghii (Wall.) Lindl. | Taiwan, China, Japan | WP | Decoction | Fever, snake bite, lung and liver diseases, hypertension, child malnutrition [216] | Hypoglycemic effect (414, streptozotocin (STZ) diabetic rats) [217], hypoglycemic and antioxidant effects (water extract, alloxan-induced diabetic mice, DPPH) [218] |

| 116 | Ansellia africana Lindl. | Southern & Eastern Africa | PD, ST, ST, RT | Decoction | Pedi is used to treat cough, the stem is used as aphrodisiac, used as emetic agent [161] | |

| 117 | Bulbophyllum kwangtungense Schltr. | China, Japan | TB | Tonic | To treat pulmonary tuberculosis, promote body liquid production, reduce fever, hemostatic agent [219] | Anti-tumor activities (456, 457, 458, against HeLa and K562 human tumor cell line) [220] |

| 118 | Bulbophyllum odoratissimum (Sm.) Lindl. ex Wall. | China, Burma, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Nepal, Bhutan, India | WP | Decoction | To treat pulmonary tuberculosis, chronic inflammation and fracture [221] | Anti-tumor (bibenzyl, inhibiting NO microphage) [221,222], anti-cancer (225, 470, 471, 475, 476, 478, 479, 482, 484, human leukaemia cell lines K562 and HL-60, human lung adenocarcinoma A549, human hepatoma BEL-7402 and human stomach cancer SGC-790) [223], anti-cancer (human leukemia cell lines K562 and HL-60, human lung adenocarcinoma A549, human hepatoma BEL-7402 and human stomach cancer cell lines SGC-7901) Anti-cancer (473 and 474, human leukemia cell lines K562 and HL-60, human lung adenocarcinoma A549, human hepatoma BEL-7402 and human stomach cancer SGC-7901) [224] |

| 119 | Bulbophyllum vaginatum (Lindl.) Rchb.f. | Malaysia | WP | Juice | Juice of the plant is instilled in the ear to cure earache [130] | |

| 120 | Catasetum barbatum (Lindl.) Lindl. | Japan, Guiana, Paraguayan | WP | Decoction | Febrifuge, anti-inflammatory [46] | Anti-inflammatory (505, rat) [225] |

| 121 | Coelogyne sp | Indonesia | RT | Decoction | Headache, fever [71] | |

| 122 | Cymbidium aloifolium (L.) Sw. | Thailand, Vietnam | LF | Decoction (internal), juice from heated or crushed leaves. | Otitis media, colds, irregular periods, arthritis, sores, burns, tonic [226] | Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory (EtOH extract, mice) [227] |

| 123 | Cymbidium canaliculatum R.Br | Australia | PdB | Chewed, poultice | Dysentery, boils, sores, wounds, itschy skin, fractured arms over the break [154,228] | |

| 124 | Cymbidium ensifolium (L.) Sw | Taiwan, Vietnam | LF, RT, FL, WP, RT | Decoction | Diuretic agent (leaves), pectoral agent (root), eye problem (flower), cough, lung, gastrointestinal problems and sedative [226] | |

| 125 | Cymbidium goeringii (Rchb.f.) Rchb.f. | Japan, China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, India | WP | Decoction | Hypertension, diuretic agent [229] | Anti-inflammatory (478, RAW 264.7 cells) [230], anti-hypertensive (515, rat), diuretic activity (515, rats) [229] |

| 126 | Cymbidium madidum Lindl. | Australia | PdB | Chewed | Dysentery [154] | |

| 127 | Dendrobium affine (Decne.) Steud. | Australia | PdB | Poultice, external | Chrushed pseudobulbs (sticky) is applied to itchy skins, boils, infected skin lesion, minor burns [154] | |

| 128 | Dendrobium aloifolium (Blume) Rchb.f. | South East Asia | LF | Poultice | Headache [18] | |

| 129 | Dendrobium amoenum Wall. ex Lindl. | China | LF | Dried and ground | Skin diseases [231] | Antioxidant (519, NBT), antibacterial (519, diffusion) [231] |

| 130 | Dendrobium chryseum Rolfe | Australia | LF | Decoction | Diabetes [232] | Antioxidant (526, 530, 532, DPPH) [233] |

| 131 | Dendrobium candidum Wall. ex Lindl. | China | LF | Decoction | Diabetes [234] | Inhibitory effect of atropine on salivary secretion (extracts, rabbit) [235], anti-hyperglicemic (extract, streptozotocin-induced diabetic (STZ-DM) rats) [234], antioxidant (polysaccharide, 10-phenanthroline-Fe2+-H2O2 systems and ammonium peroxydisulfate/N,N,N’,N’-tetra-methylethanediamine systems) [236] antioxidant (555, 556, DPPH) [237], antioxidant (558, 559, 560, DPPH) [238], anti-tumor (soluble polysacharride, human neuroblastoma (SH2SY5Y) induced by SPD was observed and analyzed by Hoechst stain method) [239] |

| 132 | Dendrobium canaliculatum var. foelschei (F.Muell.) Rupp & T.E.Hunt | Australia | PdB | Poultice, external | Chrushed pseudobulbs (sticky) is applied to infected skin and cuts [154] | |

| 133 | Dendrobium crumenatum Sw. | Malaysia, Indonesia | LF, PdTB | Leaves pounded, bulbs heated to produce juice and applied as external uses | Acne (leaves), infected ears (pseudo-tubers) [240,241] | Antimicrobial [242] |

| 134 | Dendrobium chrysanthum Wall. ex Lindl. | China | LF | Dried and ground | Skin diseases, immune regulator, anti-pyretic, improve eyesight [243,244] | Anti-inflammation (590, macrophages were harvested from 2-month-old male C57BL/6J mice) [244] |

| 135 | Dendrobium densiflorum Lindl. | China | LF | Tonic | Promote body fluid production [245] | |

| 136 | Dendrobium faciferum J.J.Sm | Indonesia | ST | Dried | For twist work (craft) [246] | |

| 137 | Dendrobium fimbriatum Hook. | Japan, China | LF | Decoction, paste | Promote body fluid production, set fractured bone (paste) [247] | Antioxidant (water-soluble crude polysaccharide (DFHP), DPPH) [248] |

| 138 | Dendrobium loddigesii Rolfe | China | LF | Decoction | Promote body fluid production, reduce fever, nourish the stomach., anti-cancer agent [249] | Inhibitors of Na+, K+-ATPase of rat kidney (607, 608) [250], antiplatelet aggregation activity (479, 523, 606, rabit platelet) [251], antioxidant (DPPH), anti NO production (activated macrophages-like cell line, RAW264.7) [252] |

| 139 | Dendrobium moniliforme (L.) Sw. | China, Taiwan | ST | Decocted dried stem | Anti-pyretic, analgesic, aphrodisiac, stomachic, tonic agents [253] | Anti-inflammatory (552, RAW 264.7 cells) [254], hypoglicemic (polisaccharide, mice) [255], antioxidant (polisacharide) [256] |

| 140 | Dendrobium moschatum (Buch.-Ham) S.w | Nepal | LF | Juice | Cure earache [257] | |

| 141 | Dendrobium nobile Lindl. | China, Indonesia | WP | Tonic | Fever, reduce mouth dryness, aphrodisiac, promote body fluid production, nourish stomach, anorexia, lumbago, impotence [240,258,259,260,261] | Immunomodulatory activity (656, 660, 661, 662, 663, lymphocyte proliferation test MTT test) [262,263], antioxidant (478, 523, 524, 528, 584, 641, 672, 673, 674, DPPH) anti-NO (478, 523, 524, 528, 584, 641, 672, 673, 674, murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7) [264], antioxidant (water-soluble polysaccharide (DNP), DPPH) [265], antimicrobial (Extracts), antitumour (extracts, Dalton’s lymphoma ascites (DLA) cells w), induction of in vitro lipid peroxidation (extracts, TBARS) [266], NO inhibition (475, 523, 542, 632, 633, 634, 665–671, murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells) [267], anti-tumor (polisachacaride extracts, sarcoma 180 in vivo and HL-60)[268] |

| 142 | Dendrobium pachyphyllum (Kuntze) Bakh.f. | Indonesia | WP | Decoction | Hydropsy [246] | |

| 143 | Dendrobium purpureum Roxb. | Indonesia, Malaysia | LF | Crushed and heated to make poultice | Nail fungal infection [240] | |

| 144 | Dendrobium salaccense (Blume) Lindl. | Indonesia | LF | Fragrance | Fragrance [246] | |

| 145 | Dendrobium teretifolium R.Br. | South-Pacific Island | LF | Decoction | Severe headache, other pains [269,270] | |

| 146 | Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. | China | LF | Decoction | Anxiety and panic [271] | |

| 147 | Dendrobium utile J.J.Sm. | Indonesia | ST | Dried | Twist work [246] | |

| 148 | Dichaea muricata (Sw.) Lindl. | Central, South American | LF | Decoction (wash) | Eye infection [260] | |

| 149 | Eulophia speciosa (R.Br.) Bolus | Indonesia | RT | Decoction | Analgesic [246] | |

| 150 | Epidendrum strobiliferum Rchb.f. | China, Korea | ST | Infusion, decoction | Analgesic [272] | Analgesic (676, 677 exhibited notable analgesic action at 3 mg/kg, causing 86 and 83% inhibition of abdominal constriction, respectively [272], antinociceptive effect (MeOH extract, methanolic ext. (ME) [273] |

| 151 | Epidendrum rigidum Jacq. | Mexico, North Sudamerica, Antilles | ST | Infusion, decoction | Replenish body fluid [274] | Phytotoxin (chloroform-methanol extract) [274] |

| 152 | Mycaranthes pannea (Lindl.) S.C.Chen & J.J.Wood | Vietnam, Malaysia | WP | External, medicinal bath | Medicinal bath to treat ague and malaria fever, fractures, bruises, skin complaints, dislocated joint to relieve severe pain, swelling, dislocation and fracture [123,275,276] | |

| 153 | Eriopsis biloba Lindl. | America | ST | Poultice | Sore gums and mouth membranes [260] | |

| 154 | Grammatophyllum scriptum (L.) Blume | Indonesia, Thailand | BL, SD, ST | Poultice | Pseudo bulb mixed with curcuma and salt applied to sores and abdomen to expel worms, to treat dropsy and aphthae, seeds mixed with food to treat dysentery, aphthae, crushed plant mixed with rice liquor to treat snake bite, scorpions’ and centipedes’ stings [246,277] | |

| 155 | Jumellea fragrans (Thouars) Schltr. | Madagascar | LF, ST | Decoction | Anti-spasmodic, anti-asthmatic agents, mixed leaves of Ziziphus mauritana, Mussaenda arcuate to treat eczema (deecotion), mixed with Eugenia uniflora to treat diarrhea [24] | |

| 156 | Liparis condylobulbon Rchb.f. | Indonesia | PdB, LF | Chewing, external | Intestinal complaints and constipation. (eastern Sulawesi, ambon), tormina, abscess [246,278] | |

| 157 | Liparis nervosa (Thunb.) Lindl. | China, Thailand, Malaysia | WP | Decoction, external | Stop internal/external bleeding, treat snake bites [278] | |

| 158 | Neottia ovata (L.) Bluff & Fingerh. | Spain | TB | Tincture | Stomach diseases [279] | Anti-viral (extract, SARS-CoV Frankfurt 1 strain [280] |

| 159 | Masdevallia uniflora Ruiz & Pav. | Mexico, south America | WP | Decoction | Facilitate urination (pregnant women), reduce bladder inflammation [260] | |

| 160 | Camaridium densum (Lindl.) M.A.Blanco | Mexico | WP | Decoction | Analgesic, relaxant agents [281] | Spasmolytic activity (667, 690, 693, 694, 695, Wistar rat) [37], antinociceptive activity (extract, mice) [281] |

| 161 | Nidema boothii (Lindl.) Schltr. | Malaysia | WP | Decoction | Relaxant agent [282] | Spasmolytic effects (471, 478, 488, 508, 671, 696, 697, 699, 700, 702, guinea ileum pig model) [282] |

| 162 | Oberonia lycopodioides (J.Koenig) Ormerod | Malaysia | LF | Poultice | Boils [123,283] | |

| 163 | Oberonia mucronata (D.Don) Ormerod & Seidenf. | China, Vietnam | WP | Decoction | Rheumatism, promote blood circulation, inflammation of the bladder/ureter, bruises and fractures, detoxicant, diuretic agent [284] | |

| 164 | Erycina pusilla (L.) N.H.Williams & M.W.Chase | Mali | WP | Decoction | Lacerations [260] | |

| 165 | Otochilus lancilabius Seidenf. | Bhutan, Nepal, India, China (Tibet), Laos and Vietnam | WP | Pills | Antiemetic, febrifuge for stomach inflammation (bad-tshad), and allays hyperdipsia and dehydration [23] | |

| 166 | Phragmipedium pearcei (Rchb.f.) Rauh & Senghas | South America | WP | Decoction | Stomachache [260] | |

| 167 | Pholidota articulata Lindl. | Himalaya, Nepal | WP | Whole plant: bone fractures [202] | ||

| 168 | Pholidota chinensis Lindl. | China, India | PdB | Tincture | Scrofula, toothache, stomachache, chronic bronchitis, duodenal ulcer [285] | Antioxidant (475, 539, 667, 670, 671, 711, 712, 717, 722, 723, 726, (DPPH), anti-inflammatory (475, 539, 667, 670, 671, 711, 712, 717, 722, 723, 726, inhibitory activity on NO production from activatedmacrophage-like cell line, RAW 264.7)[286], antioxidant (715, 741, 742, 746, 747, 749, 750, DPPH), anti-inflammatory (as above, inhibitory activity on NO production from activated macrophages-like cell line, RAW 264.7) [285] |

| 169 | Renanthera moluccana Blume | Indonesia | WP | Ornament | Ornament [246] | |

| 170 | Rhynchostylis retusa (L.) Blume | Himalaya, Nepal, India | LF | Rheumatic, hepaoprotective agent [96,202] | ||

| 171 | Scaphyglottis livida (Lindl.) Schltr. | Mexico | WP | Decoction | Analgesic, anti-inflammatory agents [281,287] | Spasmolytic (471, 475, 714, 754, 755, rat ileum rings) [288], antinociceptive (extracts, male mice ICR) [281], acute toxicity (extract, male mice ICR) [287] |

| 172 | Vanda tessellata (Roxb.) Hook. ex G.Don | India, Sri Lanka, Burma | LF, RT, FL | Leaves pounded to make juice, paste, extract (alcoholic) of the root and flower | Fever (as paste), otitis (dropped juice), the root to treat bronchitis, rheumatic, dyspepsia, sciatica, inflammation, otitis, nervous problem, fever and as aphrodisiac, laxative, tonic (for liver) agent [140,289,290,291] | Cholinergic activity (glycoside fraction), anti-arthritic (extract, albino rat) [292], anti-inflammatory (extract), antidiabetic (extract, rat) [291,293] |

| 173 | Papilionanthe teres (Roxb.) Schltr. | Indonesia | WP | Ornament | Ornamental [294] | Anti-aging (758, 759, HaCaT cytochrome C oxidase) [295] |

| 174 | Vanilla griffithii Rchb.f. | Indonesia | WP | Eaten | Edible [294] | |

| 175 | Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews | Indonesia, Mexico | FT, STh | Decoction | Fever, rheumatism, hysteria, increase energy and muscular system [25,259,294] | Antimicrobial activity (extract) [296] |

| Piperaceae | ||||||

| 176 | Peperomia galioides Kunth | Peru | WP | Poultice (external), drink (internal) | Chrused plant is used to treat wounds, cuts, plant juice is used to treat gastric ulcers [297] | Antibacterial (oil) [298,299] |

| 177 | Piper retrofractum Vahl | Indonesia | FT, RT | Drink (decoction) | Anticonvulsion, antivomiting, diarrhea, dysentery, constipation, headache [300] | Anti-convulsan (776, mice) [301], cytotoxicity (extract, 779) [302], anti-platelet aggregation (extract) [303], anti-vector (extract, mosquito larvae) [304,305], antioxidant (228, 283, 334, 574, 771, 772, 782, 783, DPPH) [306], antileishmanial activity (extracts, leishmania donovani) [307], anti-obesity (776, 777, C57BL/6J mice) [308] |

| Rubiaceae | ||||||

| 178 | Hydnophytum formicarum Jack | Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand | TB | Poultice, decoction, powder | Poultice to treat swelling, headache, decoction to treat liver, intestinal complaints, powder as anthelmintic, heart tonic, antidiabetic agent and to treat skin, bone, knee, ankle, lung diseases [278] | Anti-tumor (extracts, against human tumor cell lines, HeLa and A549) [309], xanthine oxidase inhibitory (MeOH extract, assayed spectrophotometrically under aerobic conditions [310], antimicrobial, cytotoxicity (226, 786, 787, against HuCCA-1 and KB cell lines) [311], trigger cytochrome C release in treated MCF-7 cell (786, ELISA) [312], anti-cancer (786, the human breast carcinoma cell line MCF-7) [313] |

| 179 | Myrmecodia tuberosa Jack | Indonesia | PT | Drink (decocted) | Swelling, headache [18,71,314] | Immunomodulatory effect (EtOH fractions) [315] |

| 180 | Myrmecodia pendens Merr. & L.M.Perry | Papua | PT | Decoction | Rheumatism, headache, renal problems, tumor [316] | |

| Sterculiaceae | ||||||

| 181 | Scaphium macropodum (Miq.) Beumée ex K.Heyne (hemi-epiphyte) | Indonesia | RT | Drink (decoction) | Nervous system problem [71] | |

| Verbenaceae | ||||||

| 182 | Premna parasitica Blume | Indonesia | LF | Drink (decoction) | Fever [25] | |

| Viscaceae | ||||||

| 183 | Viscum articulatum Burm.f. | Cambodia, India, Taiwan, China | WP | Poultice, decoction | Decoction to treat bronchitis, skin tumour, neuralgia, arthritis and as tonic, sedative, febrifuge, crushed plant to treat cut [317] | Toxicity (extract, mice) [318], anti-tumor (820, MTT assay) [319], anti-inflammatory (1234718, superoxide inhibition) [320], cytotoxicity and anti-HIV-1 activity (shown by isolated compounds including 801, 804, 803, 813, 814, 815, 824, 828); MDAMB-435 and Hela cells, HIV-1ШB-infected C8166 cells) [321], anti-nephrotoxic (127, gentamicin-induced renal damage in Wistar rats) [322], antioxidant, anti-inflammatory (810, 811, 812, 822, 825, 829, 830, 831, 832, 833, 834, DPPH, NO production and cell viability assay. The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7) [323], diuretic activity (MeOH extract, male rats) [324], antiepileptic activity (MeOH exctract, rat) [325], anti-hypertension (glucocorticoid-induced hypertension, Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl in rats) [326,327], antioxidant (polisacharide fraction, DPPH) [328] |

| 184 | Viscum ovalifolium DC. | Cambodia, Malaysia | LF, WP | Poultice, external | Leaves (poultice) to treat neuralgia, as herbal bath to treat fever in children, ash mixed with sulphur, coconut oil to treat pustular itches [329] | |

| Zingiberaceae | ||||||

| 185 | Hedychium ongi cornotum Griff. | Indonesia | RZ, RT | Drink (decoction) | Rhizome is used to treat syphilis; root is used to treat worm [25] | |

Note: na: not mentioned; ST: stem, PT: pith; TB: tuber; SP: spore; BK: bark; LT: latex; NT: nutmeg; SD: seed; FT: fruit; BD: buds; PD: pedi; PdB: pseudobulbs; FL: flower; PdTB: pseudotuber; BL: bulbs: STh: sheath; WP: whole; LF: leaf; RT: root; RZ: rhizome.

Figure 2.

Five most popular medicinal epiphytes. (A) C. filiformis L. (B) B. odoratissimum (Sm.) Lindl. ex Wall. (C) C. goeringii (Rchb.f.) Rchb.f. (D) A. aureum Limme. (E) F. natalensis Hochst.

2.2. Distribution of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species by Country

Based on the available records, the data curation and analysis revealed that the Indigenous Indonesians have used 58 diverse epiphytic medicinal plant species throughout the archipelago and have the highest record compared to other tropical countries (Figure 3). China is second and is well known for its traditional medicine, including the use of epiphytes in medicament preparation. This is followed by the Indigenous Indians, with the well-established Ayurveda as a formal record of Indian medicinal plants. The traditional medicinal plant knowledge of Indonesa has been heavily influenced by Indian culture and enriched by Chinese and Arabian traders since the kingdom era [27].

Figure 3.

Density map showing a number of epiphytic medicinal plant species used by different countries. The number of species used is proportional to colour intensity.

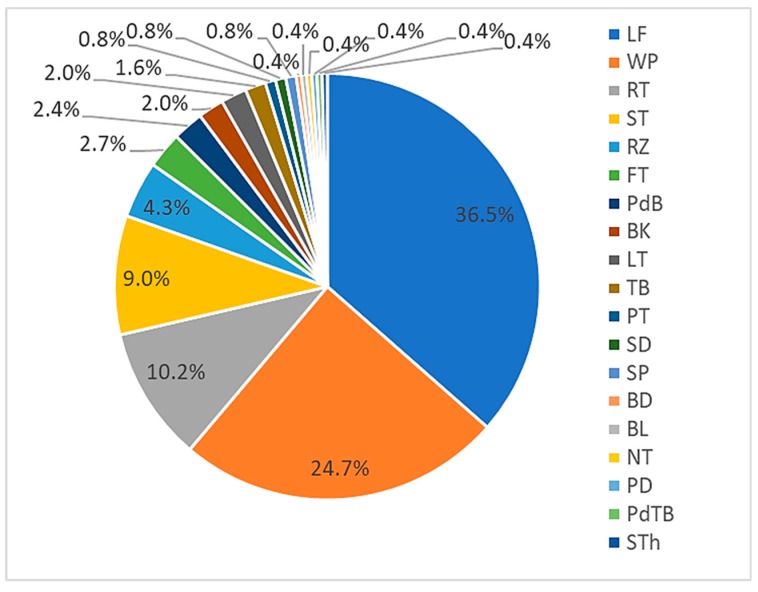

2.3. Parts of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species Used in Traditional Medicines

This review determined that leaves were the main plant components used in the traditional medicines (Figure 4). This was expected given they are more easily harvested (without excessive tools) and processed compared to other plant parts, e.g., the root and stem. As some epiphytes have a small biomass compared to higher trees, the whole plant is commonly harvested in medicament preparation. Interestingly, almost half of epiphytic medicinal plants were ferns, in which the stem-like stipe is prepared for medicine. Without haustoria (a specialised absorbing structure of a parasitic plant), the root and rhizome of epiphytic medicinal plants are easily harvested and prepared.

Figure 4.

Components of epiphytic plants used in medicinal preparations (represented in percentages). LF: leaf; WP: whole; RT: root; ST: stem, RZ: rhizome; FT: fruit; PdB: pseudobulbs; BK: bark; LT: latex; TB: tuber; PT: pith; SD: seed; SP: spore; BD: buds; BL: bulbs: NT: nutmeg; PD: pedi; PdTB: pseudotuber; STh: sheath.

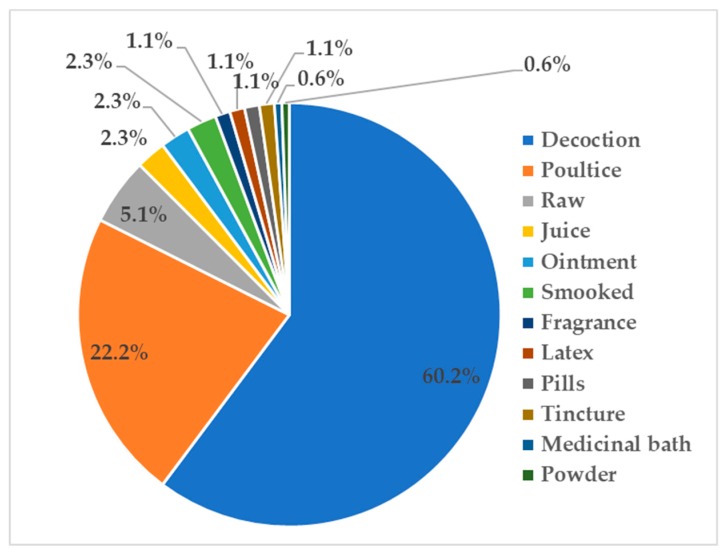

2.4. Modes of Preparation and Dosage of Administration of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species in Traditional Medicines

Generally, medicinally active secondary metabolites have a water solubility problem likely related to the lipophilic moieties in their structures [29]. Using boiling water, decoctions are able to increase the yield of secondary metabolites extracted from medicinal plants. Therefore, it is not surprising that decoctions are commonly used in traditional medicine preparations from plants (Figure 5). External applications are also commonly practiced in traditional medicinal therapies, including poultice (moist mass of material), raw, or less processed medicine. Poultices were commonly prepared for skin diseases while a decoction was ingested for internal infectious diseases (i.e., fever).

Figure 5.

Modes of preparation and administration of epiphytic medicinal plants (represented in percentages).

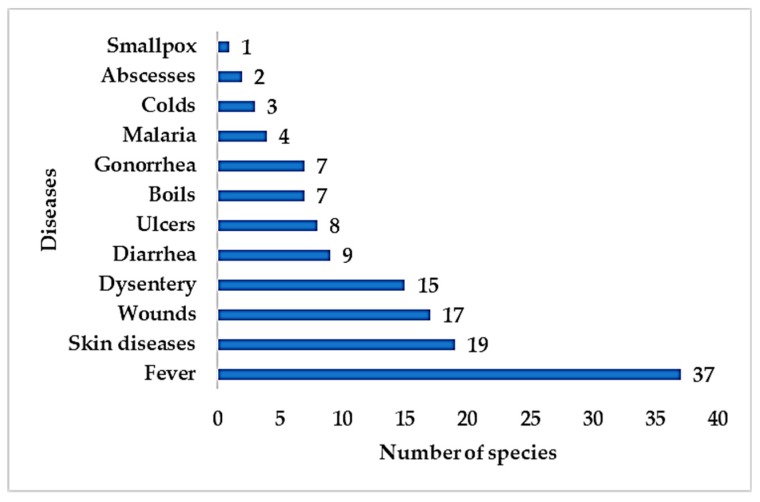

2.5. Category of Diseases Treated by Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species

Interestingly, epiphytes have been used for treating various ailments, including both infectious and non-infectious diseases. Traditional communities described infectious diseases related to skin diseases (wounds, boils, ulcers, abscesses, smallpox) and non-skin diseases (fever, diarrhoea, ulcers, colds, worm infections, and malaria). A total of 54 epiphytic medicinal plant species were prescribed to treat skin diseases while 81 species to treat non-skin infectious diseases (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Number of epiphytic medicinal plant species used traditionally to treat infectious diseases.

Hygiene has been a serious issue in traditional communities as it gives rise to infectious diseases. Fever is a common symptom of pathogenic infection and has been treated using medicinal plants, including epiphytes. Hygiene issues are also a common cause of skin disease, wounds, dysentery, and diarrhoea in traditional communities.

3. Phytochemical Composition of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants

Epiphytes belong to a distinctive plant class as they do not survive in soil and this influences the secondary metabolites present. Epiphytes are physically removed from the terrestrial soil nutrient pool and grow upon other plants in canopy habitats, shaping epiphyte morphologies by the method in which they acquire nutrients [30]. Nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, are obtained from different sources, including canopy debris (through fall) and host tree foliar leaching [30], the latter influencing canopy soil nutrient cycling [31,32]. In the conversion of sunlight into chemical energy, the epiphyte often uses a specific carbon fixation pathway (CAM: Crassulacean acid metabolism) as a result of harsh environmental conditions [33], making them unique and thus worthwhile for scientific studies.

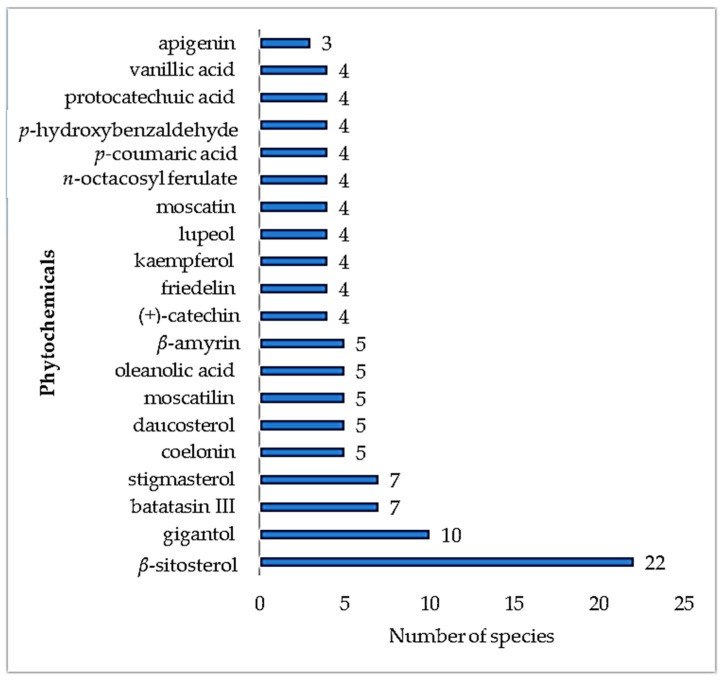

In the early 20th century, laboratory-based research on epiphytes studied the plant’s production of alkaloids, cyanogenetic, and organic sulfur compounds, with the plants producing limited quantities of these compounds [34]. Common plant steroids, e.g., β-sitosterol, have been shown to be present in 22 different epiphytic medicinal plants (Figure 7). This is possibly due to the function of the steroids as structural cell wall components, giving rise to a wide distribution across plant families and species. A further example of a common plant steroid present is stigmasterol.

Figure 7.

Number of epiphytic medicinal plant species producing the same secondary metabolites.

Table 2 lists the secondary metabolites identified in epiphytic medicinal plants and details the species, isolated compounds, and provides references. Currently, only 69 species have been phytochemically studied (23 fern and 46 non-fern epiphytes) and 842 molecules have been isolated from these epiphytic plants. Analysis of the literature showed epiphytes were able to produce a range of secondary metabolites, including terpenes and flavonoids, with no alkaloids being isolated from epiphytic fern medicinal plants thus far. β-Sitosterol, a common phytosterol in higher plants, was reported across fern genera. Interestingly, there is one unique terpene produced, hopane, which is commonly called fern sterol. Common flavonoids, such as kaempferol, quercetin, and flavan-3-ol derivatives (catechin), were also reported across the epiphytic ferns. Epiphytic pteridaceae, Acrostichum aureum Limme, is rich in quercetin [35]. Further analysis showed there were more secondary metabolites reported from non-fern epiphytic medicinal plants than from fern epiphytic medicinal plants, including terpene derivatives, flavonoids, and alkaloids. Included were flavanone, flavone, and flavonol derivatives but no flavan-3-ols were reported in these epiphytes so far. In the non-fern epiphytes, there were more phytochemical studies on orchid genera with additional classes of compounds reported, including penantrene derivatives (flavanthrinin, nudol, fimbriol B) [36,37] from the Bulbophyllum genus and the alkaloid dendrobine from the Dendrobium genus [38].

Table 2.

Phyctochemical constituents of epiphytic medicinal plants.

| No | Epiphyte Species | Constituents |

|---|---|---|

| Fern species | ||

| Adiantaceae | ||

| 1 | Adiantum caudatum L., Mant | 16-hentriacontanone 1, 19α-hydroxyferna-7,9(11)-diene 2, 29-norhopan-22-ol 3, 3α-hydroxy-4α-methoxyfilicane 4, 8α-hydroxyfernan-25,7β-olide 5, adiantone 6, filic-3-ene 7, hentriacontane 8, isoadiantone 9, quercetin-3-O-glucoside 10, β-sitosterol 11, β-sitosterol 11, β-sitosterol glucoside 12 [330,331,332] |

| Aspleanceae | ||

| 2 | Asplenium nidus L. | (-)-epiafzelechin 3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 13, homoserine 14 [333] |

| Blechnaceae | ||

| 3 | Stenochlaena palustris (Burm. F.) Bedd. | 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(2S*,3R*,4E,8Z)-2-N-[(2R)-hydroxytetracosanoyl]octadecasphinga 4,8-dienine 15, 3-formylindole 16, 3-oxo-4,5-dihydro-α-ionyl-β-d-lucopyranoside 17, kaempferol 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 18, kaempferol 3-O-(3′,6′-di-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-d-glucopyranoside 19, kaempferol 3-O-(3′-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-(6′-O-E-feruloyl)-β-d-glucopyranoside 20, kaempferol 3-O-(3′-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-d-glucopyranoside 21, kaempferol 3-O-(6′-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-d-glucopyranoside 22, lutein 23, stenopaluside 24, stenopalustrosides A–E 25–29, β-sitosterol-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 30 [334,335] |

| Davalliaceae | ||

| 4 | Araiostegia divaricata (Blume) M. Kato | (-)-epicatechin 3-O-β-d-(2”-O-vanillyl)allopyranoside 31, (-)-epicatechin 3-O-β-D-(2′-trans-cinnamoyl)allopyranoside 32, (-)-epicatechin 3-O-β-D-(3”-O-vanillvl)allopyranoside 33, (-)-epicatechin 3-O-β-d-(3′-trans-cinnamoyl)allopyranoside 34, (-)-epicatechin 3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 35, (-)-epicatechin 3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 35, (+)-catechin 3-O-β-allopyranoside 36, 24-norferna-4 (23) 37, 4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epicatechin 38, 4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epicatechin methyl ester 39, 4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epicatechin potasium 40, 9(11)-diene 41, cyanin 42, davallic acid 43, epiafzelechin-(4β→8)-epicatechin 3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 44, epicatechin-(4β→6)-epicatechin-(4β→8)-epicatechin-(4β→6)-epicatechin-D-glucooctono-δ-lactone enediol 45, epicatechin-(4β→8)-4β-carboxymethylpicatechin 46, hop-21-ene 47, monardein 48, pelargonin 49, procyanidin B-2 3”-O-β-d-allopyranoside 50, sodium salts 51 [59,60,336,337,338,339,340] |

| 5 | Davallia solida (G. Forst.) Sw. | 18-diene 52, 18-diene 52, 19α-hydroxyfernenes 53, 19α-hydroxyfilic-3-ene 54, 2-C-β-d-glucopyranosyl-1,3,6,7-tetrahydroxyxanthone 55, 2-C-β-d-xylopyranosyl-1,3,6,7-tetrahydroxyxanthone 56, 2-C-β-d-xylopyranosyl-1,3,6,7-tetrahydroxyxanthone 56, 30-O-p-hydroxybenzoylmangiferin 57, 3-O-p-hydroxybenzoylmangiferin 58, 40-O-phydroxybenzoylmangiferin 59, 4-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-2,6,4′-trihydroxybenzophenone 60, 4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epicatechin 38, 4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epicatechin methyl ester 39, 60-O-p-hydroxybenzoylmangiferin 61, eriodictyol 62, eriodictyol-8-C-β-d-glucopyranoside 63, fena-9(11) 64, fern-7-en-19α-ol 65, fern-9(11)-en-19α-ol 66, ferna-7 67, filic-3-en-19α-ol 68, filica-3,18,20-triene 69, filica-3,18-diene 70, icariside E3 71, icariside E5 72, mangiferin 73 [66,68,338,341,342] |

| Lycopodiaceae | ||

| 6 | Huperzia carinata (Desv. ex Poir.) Trevis | carinatumins A, B, and C 74, 75, 76 [74] |

| 7 | Huperzia phlegmaria (L.) Rothm | 14β,21α,29-trihydroxyserratan-3β-yl dihydrocaffeate (lycophlegmariol D) 77, 21α,24-dihydroxyserrat-14-en-3β-yl 4-hydroxycinnamate (lycophlegmariol C) 78, 21β,24,29-trihydroxyserrat-14-en-3β-yl dihydrocaffeate (lycophlegmariol B) 79, 21β,29-dihydroxyserrat-14-en-3α-yl dihydrocaffeate (lycophlegmariol A) 80, 21β-hydroxy-serrat-14-en-3α-ol 81, 21β-hydroxy-serrat-14-en-3α-yl acetate 82, 8,11,13-abietatriene-3β,12-dihydroxy-7-one (margocilin) 83, 8-deoxy-13-dehydroserratinine 84, 8-deoxyserratinidine 85, acrifoline 86, annotine 87, annotinine 88, dihydrolycopodine 89, epidihydrofawcettidine 90, fawcettidine 91, huperzine A 92, lycododine 93, lycoflexine 94, lycophlegmarin 95, lycophlegmarin 95, lycophlegmarine 96, lycophlegmine 97, lycopodine 98, malycorin A 99, malycorins B, C 100, 101, N,N′-dimethylphlegmarine 102, phlegmanol A–E 103–107, phlegmaric acid 108, α-obscurine 109, β-obscurine 110 [77,343,344,345,346,347,348] |

| 8 | Huperzia megastachya (Baker) Tardieu | 21-epi-serratenediol 111, 21-epi-serratenediol-3-acetate 112, lycoclavanol 113, megastachine 114, phlegmanol-D 115, serratenediol 116, serratenediol-3-acetate 117, serratenonediol diacetate 118, tohogenol diacetate 119 [349,350] |

| 9 | Nephrolepis biserrata (Sw.) Schott | 1β,11α-diacetoxy-11,12-epoxydrim-7-ene 120, 1β,3β,11α-triacetoxy-11,12-epoxydrim-7-ene 121, 1β,6α,11α-triacetoxy-11,12-epoxydrim-7-ene 122, sequoyitol 123 [339,351] |

| Oleandraceae | ||

| 10 | Nephrolepis cordifolia (L.) C. Presl | fern-9(11)-ene 124, hentriacontanoic acid 125, myristic acid octadecylester 126, oleanolic acid 127, sequoyitol (patent) 123, triacontanol 128, β-sitosterol 11 [352,353] |

| Opioglossaceae | ||

| 11 | Botrychum lanuginosum Wall.ex Hook & Grev. | (6′-O-palmitoyl)-sitosterol-3-O-β-d-glucoside 129, 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(2S,3R,4E,8Z)-2-[(2R-hydroxy hexadecanoyl) amino]-4,8-octadecadiene-1, 3-diol 130, 30-nor-21β-hopan-22-one 131, apigenin 132, β-sitosterol 133, daucosterol 134, luteolin 135, luteolin-7-O-glucoside 136, thunberginol A 137 [354] |

| Polypodiaceae | ||

| 12 | Drynaria roosii Nakaike | kaempferol 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside-7-O-α-l-arabinoside 138, (2R)-naringin 139, (2S)-narigenin-7-O-β-d-glucoside 140, kaemperol 3-O-α-l-rhamnosyl-7-O-β-d-glucoside 141, luteolin-7-O-β-d-neohesperidoside 142, maltol glucoside 143, (-)-epicatechin 144, 12-O-caffeoyl-12-hydroxyldodecanoic acid 145, xanthogalenol 146, naringenin 147, kushennol F 148, sporaflavone G 149, kuraninone 150, leachianone A 151, 8-phenylkaempferol 152, kaempferol 153, chiratone 154, fern-9(11)-ene 155, hop-22(29)-ene 156, isoglaucanone 157, dryocrassol 158, dryocrassol acetate 159, (+)-afzelechin-3-O-β-allopyranoside 160, (+)-afzelechin-6-C-β-glucopyranoside 161, 4α-carboxymethyl-(+)-catechin methyl ester 162, (-)-epiafzelechin-(4β→8)-(-)-epiafzelechin-(4β→8)-4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epiafzelechin methyl ester 163, (-)-epiafzelechin-(4β→8)-4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epicatechin methyl ester 164, (-)-epiafzelechin-(4β→8)-4α-carboxymethy-(-)-epiafzelechin ethyl ester 165, (-)-epiafzelechin-3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 166, (-)-epicatechin-3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 167, (+)-catechin 168, 4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epiafzelechin methyl ester 169, 4β-carboxymethyl-(-)-epiafzelechin 170, (-)-epiafzelechin-(4β→82→O→7)-epiafzelechin-(4β→8)-epiafzelechin 171, (-)-epiafzelechin 172, (-)-epiafzelechin-(4β→8)-4β-carboxymethyl-epiafzelechin methyl ester 173, epicatechin-(4β→8)-epicatechin 174, (+)-afzelechin 175, (+)-epicatechin-3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 176, (-)-epicatechin-8-C-β-d-gluclopyranoside 177, (-)-epiafzelechin-5-O-β-d-allopyranoside 178, drynachromoside A 179, drynachromoside B 180, fortunamide 181, curcumine 182, demethoxycurcumine 183, bisdemethoxycurcumine 184, bavachinine 185, isobavachalcone 186, (-)-epicatechin 144, liquiritine 187, bakuchiol 188, protocatechuic acid 189, (R)-5,7,3′,5′-tetrahydroxy-flavonone 7-O-neohesperidoside 190, (2S)-5,7,3′,5′-tetrahydroxyflavonone 7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 191, 5,7,3′,5′-tetrahydroxflavanone 192, 3′-lavandulyl-4-methoxy-2,2′,4′,6′-tetrahydroxyylcalcone 193, 5,7-dihydroxychromone-7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 194, 5,7-dyhidroxychromone-7-O-neohesperidosyl 195 [43,94,355,356,357,358] |

| 13 | Drynaria propinqua (Wall. ex Mett.) Bedd | (-)-epiafzelechin 3-O-β-d-allopyranoside 13 [359] |

| 14 | Drynaria quercifolia (L.) J.Sm. | friedelin 196, epifriedelinol 197, β-amyrin 198, β-sitosterol 11, 3-β-d-glucopyranoside 199, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid 200, acetyllupeol 201 [97,360] |

| 15 | Drynaria rigidula (Sw.) Bedd. | fern-9(11)ene 202, hop-22(29)-ene 156, γ-sitosterol 203, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid 200, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid 204, 4-hydroxyphenyl-1-(2-arabinopyranosyl)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triol 205, 4-hydroxyphenyl-1-tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triol 206, kaempferitrin 207, 3,5-dihydroxy-flavone-7-O-β-rhamnopyranosyl-4′-O-β-glucopyranoside 208 [92,361] |

| 16 | Phymatosorus scolopendria (Burm. f.) Pic. Serm. | 1,2-benzopyrone (coumarin) 209 [47] |

| 17 | Pyrrosia lingua (Thunb.) Farw. | diploptene 210, β-sitosterol 11, octanordammarane 211, dammara-18(28),21-diene 212, (18S)-18-hydroxydammar-21-en 213, (18R)-18-hydroxydammar-21-ene 214, (18S)-pyrrosialactone 215, (18R)-pyrrosialactone 216, (18S)-pyrrosialactol 217, 3-deoxyocotillol 218, dammara-18(28),21-diene 212, cyclohopenol 219, cyclohopanediol 220, hop-22(29)-en-28-al 221 [362,363,364] |

| 18 | Pyrrosia petiolosa (Christ) Ching | α-tocopherol 222, diploptene 210, 24-methylene-9,19-cyclolanost-3β-yl acetate 223, cycloeucalenol 224, β-sitosterol 11, daucosterol 134, vanillic acid 225, protocatechualdehyde 226, hydrocaffeic acid 227, caffeic acid 228, 7-O-[6-O-(α-l-arabinofuranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]gossypetin 229, kaempferol-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside-7-O-α-l-arabinofuranoside 230 [365,366,367,368] |

| 19 | Pyrrosia sheareri (Baker) Ching | diploptene 210, β-sitosterol 11, vanillic acid 225, protocatechuic acid 189, mangiferin 73, fumaric acid 231, sucrose 232 [42] |

| Psilotaceae | ||

| 20 | Psilotum nudum (L.) P. Beauv | apigenin di-C-glycoside 233, 7,4′,4′-tri-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 234, 4′,4′-di-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 235, 7,4′-di-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 236, 3′-hydroxypsilotin (6-[4′-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-3′-hydroxyphenyl]-5,6-dihydro-2-oxo-2H-pyran) 237, 24-methylene-5α-lanost-8-en-3β-ol 238, 24β-methyl-25-dehydrolophenol 239, codisterol 240, isofucosterol 241, 24-methylene-25-hydroxyphenol 242, avenasterol 243, psilotin 244 [368,369,370,371] |

| Pteridaceae | ||

| 21 | Acrostichum aureum L. | quercetin 3-O-β-d-glucoside 245, ponasterone A 246, lupeol 247, friedelin 196, β-sitosterol 11, stigmasterol 248, campesterol 249, tetracosanoic acid 250, ursolic acid 251, gallic acid 252, (2R,3S)-sulfated pterosin C 253, (2S,3S)-sulfated pterosin C 254, (2S,3S)-pterosin C 255, (2R)-pterosin P 256, patriscabratine 257, tetracosane 258, quercetin-3-O-β-d-glucoside 259, quercetin-3-O-β-d-glucosyl-(6→1)-α-l-rhamnoside 260, quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnoside 261, quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnosyl-7-O-β-d-glucoside 262, kaempferol 153 [35,372,373,374] |

| 22 | Selaginella involvens (P.Beauv.) Spring | hexadecanoic acid 263, stearic acid 264, β-sitosterol 11, stigmasterol 248, amentoflavone 265, β-d-glucopyranoside 266, (3β)-cholest-5-en-3yl 267, β-amyrin 198 [375] |

| Vittariaceae | ||

| 23 | Vittaria elongate Sw. | vittarin-A-F 268–273, 3-O-acetylniduloic acid 274, ethyl 3-O-acetylniduloate 275, methyl 4-O-coumaroylquinate 276, vittarilide-A, B 277, 278, vittariflavone 279, methyl 4-O-caffeoylquinate 280, ethyl 4-O-caffeoylquinate 281, methyl 5-O-caffeoylquinate 282, apigenin 132, vitexin 283, 5,7-dihydroxy-3′,4′,5′-trimethoxyflavone 284, amentoflavone 265, trans-p-coumaric acid 285, methyl trans-p-coumarate 286, methyl caffeate 287, ferulic acid 288, p-cresol 289, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde 290, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid 204, methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate 291, protocatechualdehyde 226, protocatechuic acid 189, methyl protocatechuate 292, vanillin 293, vanillic acid 225 [119] |

| Non-Fern | ||

| Balsaminaceae | ||

| 24 | Impatiens niamniamensis Gilg (semi epiphytic) | α-N,N,N-trimethyltryptophan betaine 294 [129] |

| 25 | Convolvulaceace (parasite) | |

| 26 | Cassytha filiformis L. | N-(3,4-dimethoxyphenethyl)-4,5-methylenedioxy-2-nitrophenylacetamide 295, actinodaphnine 296, cassythine 297, isoboldine 298, cassameridine 299, cassamedine 300, lysicamine 301, cathafiline 302, cathaformine 303, actinodaphnine 304, N-methylactinodaphnine 305, cathafiline 306, cathaformine 307, predicentrine 308, ocoteine 309, filiformine 310, (+)-diasyringaresinol 311, cathafiline 312, cathaformine 313, actinodaphnine 314, N-methylactinodaphnine 315, predicentrine 308, ocoteine 316, neolitsine 317, dicentrine 318, cassythine (cassyfiline) 319, actinodaphnine 320, 4-O-methylbalanophonin 321, cassyformin 322, isofiliformine 323, cassythic acid 324, cassythic acid 324, cassythine 325, neolitsine 326, dicentrine 318, 1,2-methylenedioxy-3,10,11-trimethoxyaporphine 327, (-)-O-methylflavinatine 328, (-)-salutaridine 329, isohamnetin-3-O-β-glucoside 330, isohamnetin-3-O-rutinoside 331 [134,354,376,377,378,379,380] |

| 27 | Cuscuta australis R.Br. | 4-oic acid-7-oxo-kaurene-6α-O-β-d-glucoside 332, thymidine 333, caffeic acid 228, p-coumaric acid 334, caffeic-β-d-glucoside 335, kaempferol 153, quercetin 336, astragalin 337, hyperoside 338, astragalin 339, kaempferol 153, quercetin 336, β-sitosterol 11, β-sitosterol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside 340 [381,382,383] |

| 28 | Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. | coumarin 341, α-amyrin 342, β-amyrin 198, α-amyrin acetate 343, β-amyrin acetate 344, oleanolic acetate 345, oleanolic acid 127, stigmasterol 248, lupeol 247, stigmast-5-en-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside tetraacetate 346, stigmast-5-en-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 347, stigmast-5-en-3-yl-acetate 348, β-sitosterol 11, 3,5,7,3′-pentahydroxyflavanone (taxifolin) 349, 3,5,7,4′-tetrahydroxyflavanone (aromadendrin) 350 [143,384,385] |

| Clusiaceae | ||

| 29 | Clusia grandiflora Splitg. (hemi epiphyte) | friedelin 196, β-amyrin 198, β-sitosterol 11, lupeol 247, chamone I 351, chamone II 352 [149,386] |

| Loganiaceae | ||

| 30 | Fagraea auriculata Jack. (semi epiphyte) | di-O-methylcrenatin 353, potalioside B 354, adoxosidic acid 355, adoxoside 356, (þ)-pinoresinol 357, salicifoliol 358 [153] |

| Loranthaceae (parasite) | ||

| 31 | Dendrophthoe falcata (L.f.)Ettingsh | 3β-acetoxy-1β-(2-hydroxy-2-propoxy)-11α-hydroxy-olean-12-ene 359, 3β-acetoxy-11α-ethoxy-1β-hydroxy-olean-12-ene 360, 3β-acetoxy-1β-hydroxy-11α-methoxy-olean-12-ene 361, 3β-acetoxy-1β,11α-dihydroxy-olean-12-ene 362, 3β-acetoxy-1β,11α-dihydroxy-urs-12-ene 363, 3β-acetoxy-urs-12-ene-11-one 364, 3β-acetoxy-lup-20(29)-ene 365, 30-nor-lup-3β-acetoxy-20-one 366, (20S)-3β-acetoxy-lupan-29-oic acid 367, kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside 368, quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside 369, gallic acid 252 [387] |

| 32 | Loranthus globosus Roxb | (+)-catechin 168, 3,4-dimethoxycinnamyl alcohol 370, 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamylalcohol 371 [163] |

| 33 | Macrosolen cochinchinensis (Lour.) Tiegh. | quercetin 336, gallic acid 252, orientin 372, rutin 373, quercetin-3-O-apiosyl(1→2)-[rhamnosyl(1→6)]-glucoside 374, vicenin 375 [388] |

| 34 | Scurrula atropurpurea (Blume) Danser | octadeca-8,10,12-triynoic acid 376, hexadec-8-ynoic acid 377, hexadec-10-ynoic acid 378, hexadeca-8,10-diynoic acid 379, hexadeca-6,8,10-triynoic acid 380, hexadeca-8,10,12-triynoic acid 381, (Z)-9-octadecenoic acid 382, (Z,Z)-octadeca-9,12-dienoic acid 383, (Z,Z,Z)-octadeca-9,12,15-trienoicacid 384, octadeca-8,10-diynoic acid 385, (Z)-octadec-12-ene-8,10-diynoic acid 386, octadeca-8,10,12-triynoic acid 376, theobromine 387, caffeine 388, quercitrin 389, rutin 373, icariside B2 390, aviculin 391, (+)-catechin 168, (-)-epicatechin 144, (-)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate 392, (-)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate 393 [169,170] |

| 35 | Scurrula ferruginea (Jack) Danser | glycoside 4′-O-acetyl-quercitrin 394 [389] |

| 36 | Scurrula parasitica L. | (+)-catechin 168 [178] |

| Moraceae | ||

| 37 | Ficus pumila L. | (1S,4S,5R,6R,7S,10S)-1,4,6-trihydroxyeudesmane 6-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 39, (1S,4S,5S,6R,7R,10S)-1,4-dihydroxymaaliane 1-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 396, (23Z)-3β-acetoxycycloart-23-en-25-ol 39, (23Z)-3β-acetoxyeupha-7,23-dien-25-ol 39, (24RS)-3β-acetoxycycloart-25-en-24-ol 39, (24S)-24-hydroxystigmast-4-en-3-one 400, (24S)-stigmast-5-ene-3β,24-diol 401, 10α,11-dihydroxycadin-4-ene 11-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 402, 3β-acetoxy-(20R,22E,24RS)-20,24-dimethoxydammaran-22-en-25-ol 403, 3β-acetoxy-(20S,22E,24RS)-20,24-dimethoxydammaran-22-en-25-ol 404, 3β-acetoxy-20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27-octanordammaran-17β-ol 405, 3β-acetoxy-22,23,24,25,26,27-hexanordammaran-20-one 406, cycloartane-type triterpenoids 407, triterpenoid 408 [390,391,392] |

| Orchidaceae | ||

| 38 | Anoectochilus formosanus Hayata | (6R,9S)-9-hydroxy-megastigma-4,7-dien-3-one-9-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 409, (R)-(+)-3,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid γ-lactone 410, 1-O-isopropyl-β-d-glucopyranoside 411, 2-(β-d-glucopyranosyloxymethyl)-5-hydroxymethylfuran 412, 3-(R)-3-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy-4-hydroxybutanoic acid 413, 3-(R)-3-β-d-glucopyranosyloxybutanolide (kinsenoside) 414, 4-(β-d-glucopyranosyloxy)benzyl alcohol 415, corchoionoside C 416 [393] |

| 39 | Anoectochilus roxburghii (Blume) | 24ξ-isopropenylcholesterol 417, 5-hydroxy-3′,4′,7-trimethoxyflavonol-3-O-β-D-rutinoside 418, 7-O-β-D-diglucoside 419, 8-C-β-hydroxybenzylquercetin 420, 8-p-hydroxybenzyl quercetin, 421, anoectosterol 422, campesterol 249, cirsilineol 423, daucosterol 134, ferulic acid 288, isorhamnetin 424, isorhamnetin-3 425, isorhamnetin-3, 4′-O-β-d-diglucoside 426, isorhamnetin-3-O-β-D-rutinoside 427, isorhamnetin-7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 428, isorhamnetin-7-O-β-d-diglucoside 429, kaempferol-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 430, kaempferol-7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 431, p-coumaric acid 334, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde 432, quercetin 336, quercetin 3′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 433, quercetin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 434, quercetin 3-O-β-d-rutinoside 435, quercetin 7-O-β-glucoside 436, quercetin-7-O-β-D-[6′-O-(trans-feruloyl)]-glucopyranoside 437, sitosterol 438, stigmasterol 248, succinic acid 439, 3′,4′,7-trimethoxy-3,5-dihydroxyflavone 440, 3-methoxyl-p-hydroxybenzaldehyde 441, daucosterol 134, daucosterol 134, ferulic acid 288, isorhamnetin-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 442, isorhamnetin-3-O-β-D-rutinoside 443, lanosterol 444, methy1 4-β-d-glucopyranosyl-butanoate 445, o-hydroxy phenol 446, oleanolic acid 127, palmitic acid 447, p-hydroxy benzaldehyde 448, p-hydroxy cinnamic acid 449, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde 432, rutin 373, sorghumol 3-O-E-p-coumarate 450, sorghumol 3-O-Z-p-coumarate 451, stearic acid 264, succinic acid 452, β-D-glucopyranosyl-(3R)-hydroxybutanolide 453, β-sitosterol 11 [394,395,396,397,398,399,400,401,402] |

| 40 | Bulbophyllum kwangtungense Schltr. | 10,11-dihydro-2,7-dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxydibenzo[b,f]oxepine 454, 5-(2,3-dimethoxyphenethyl)-6-methylbenzo[d][1,3]dioxole 455, 7,8-dihydro-3-hydroxy-12,13-methylenedioxy-11-methoxyldibenz[b,f]oxepin 456, 7,8-dihydro-4-hydroxy-12,13-methylenedioxy-11-methoxyldibenz[b,f]oxepin 457, 7,8-dihydro-5-hydroxy-12,13-methylenedioxy-11-methoxyldibenz [b,f]oxepin, 458, cumulatin 459, densiflorol A 460, plicatol B 461 [219,403] |

| 41 | Bulbophyllum odoratissimum (Sm.) Lindl. ex Wall. | (+)-lyoniresinol-3a-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 462, 3,5-dimethoxyphenethyl alcohol 463, 3,7-dihydroxy-2,4,6-trimethoxyphenanthren 464, 3-hydroxyphenethyl 4-O-(6′- O-β-apiofuranosyl)-β-d-glucopyranoside 465, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic aldehyde 466, 3-methoxyphenethyl alc. 4-O-β-D-glucopynanoside 467, 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde 468, 4-O-β-d-glucopynanoside 469, 7-hydroxy-2,3,4-trimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene 470, batatasin III 471, Bulbophyllanthrone 472, bulbophythrins A, B 473, 474, Coelonin 475, densiflorol B 476, ethyl orsellinat 477, gigantol 478, moscatin 479, p-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid 480, p-hydroxyphenylpropionic methyl ester 481, syringaldehyde 482, syringin 483, tristin 484, vanillic acid 225 [223,224,404,405,406,407] |

| 42 | Bulbophyllum vaginatum (Lindl.) Rchb.f. | (±)-syringaresinol 485, (2R*,3S*)-3-hydroxymethyl-9-methoxy-2-(4′-hydroxy-3′,5′-dimethoxyphenyl)-2,3,6,7-tetrahydrophenanthro [4,3-b]furan-5,11-diol 486, 2,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene-3,7-diol 487, 3,4,6-trimethenanthrene-2,7-diol 488, 3,4,6-trimethoxy-9,10- dihydrophenanthrene-2,7-diol 489, 3,4′,5-trihydroxy-3′-methoxybibenzyl (tristin) 490, 3,4′-dihydroxy-5,5′-dimethoxybibenzyl 491, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid 200, 3,4-dimethoxy-9,10- dihydrophenanthrene-2,7-diol (erianthridin) 492, 3,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol (nudol) 493, 3,5-di- methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,7-diol (6- methoxycoelonin) 494, 3,5-dimeth- oxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol 495, 3′-dihydroxy-5-methoxybibenzyl 496, 4,4′,6,6′-tetramethoxy-[1,1′-biphenanthrene]-2,2′,3,3′,7,7′-hexol 497, 4,6-dimethoxy-9,10-di- hydrophenanthrene-2,3,7-triol 498, 4,6-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,3,7-triol 499, 4-methoxy-9,10- dihydrophenanthrene-2,7-diol (coelonin) 500, 4-methoxyphenan- threne-2,7-diol (flavanthrinin) 501, 4-methoxyphenanthrene- 2,3,5-triol (fimbriol B) 502, 9,10- dihydrophenanthrenes 503, dihydroferulic acid 504, Friedelin 196, p-coumaric acid, 334 [36,408,409] |

| 43 | Catasetum barbatum (Lindl.) Lindl. | 2,7-dihydroxy-3,4,8-trimethoxyphenanthrene 505 [225] |

| 44 | Cymbidium aloifolium (L.) Sw. | aloifol I 506, aloifol II 507, 6-O-methylcoelonin 508, batatasin III 471, coelonin 475, gigantol, 478, 1-(4′-hydroxy-3′,5′-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(3″-hydroxyphenyl)ethane 509, 1-(4′-hydroxy-3′,5′-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(4″-hydroxy-3″-methoxyphenyl)ethane 510, 2,7-dihydroxy-4,6-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene 511, cymbinodin-A 512, cymbinodin B 513 [410,411,412] |

| 45 | Cymbidium goeringii (Rchb.f.) Rchb.f. | β-sitosterol 11, daucosterol 134, ergosterol 514, gigantol 478, cymbidine A 515 [229,230,413] |

| 46 | Dendrobium amoenum Wall. ex Lindl. | amotin 516, amoenin 517, amoenumin 518, amoenylin, isoamoenylin 519, 3,4′-dihydroxy-5-methoxybibenzyl, 520, 4,4′-dihydroxy-3,3′,5-trimethoxybibenzyl (moscatilin) 521 [414,415,416] |

| 47 | Dendrobium chryseum Rolfe | araxerol 522, coumarin 341, moscatilin 523, chrysotobibenzyl 524, chrysotoxin 525, gigantol 478, kaempferol 153, cis-melilotoside 526, defuscin 527, dendroflorin 528, dengibsin 529, dihydromelilotoside 530, naringenin 147, n-octacosyl ferulate 531, trans-melilotoside 532 [233,417] |