Abstract

Purpose:

GOG-0218, a double-blind placebo-controlled phase III trial, compared carboplatin and paclitaxel with placebo, bevacizumab followed by placebo, or bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC). Results demonstrated significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS), but no overall survival (OS) benefit with bevacizumab. Blood samples were collected for biomarker analyses.

Experimental Design:

Plasma samples were analyzed via multiplex ELISA technology for seven pre-specified biomarkers (IL6, Ang-2, osteopontin (OPN), stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), VEGF-D, IL6 receptor (IL6R), and GP130). The predictive value of each biomarker with respect to PFS and OS was assessed using a protein marker by treatment interaction term within the framework of a Cox proportional hazards model. Prognostic markers were identified using Cox models adjusted for baseline covariates.

Results:

Baseline samples were available from 751 patients. According to our pre-specified analysis plan, IL6 was predictive of a therapeutic advantage with bevacizumab for PFS (p=0.007) and OS (p=0.003). IL6 and OPN were found to be negative prognostic markers for both PFS and OS (p<0.001). Patients with high median IL6 levels (dichotomized at the median) treated with bevacizumab had longer PFS (14.2 vs. 8.7 months) and OS (39.6 vs. 33.1 months) compared to placebo.

Conclusions:

The inflammatory cytokine IL6 may be predictive of therapeutic benefit from bevacizumab when combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Aligning with results observed in renal cancer patients treated with anti-angiogenic therapies, it appears plasma IL6 may also define those EOC patients more or less likely to benefit from the addition of bevacizumab to standard chemotherapy.

Keywords: Biomarkers, plasma, multiplex ELISA, epithelial ovarian cancer, bevacizumab

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the leading cause of gynecologic cancer-related death in the United States(1). Several anti-angiogenic agents (bevacizumab, nintedanib, cediranib, pazopanib) have demonstrated clinical efficacy and improved progression-free survival (PFS) (2–7). In specific subset analyses, these agents have demonstrated increases in overall survival (OS) within selected ovarian cancer patients as well (8–10). On June 13, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bevacizumab for use in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel, followed by bevacizumab maintenance therapy, as a front-line treatment for women with advanced ovarian cancer (11). However, bevacizumab and the other anti-angiogenic agents have significant side effects and expense, not all patients respond to the treatment, and ultimately resistance to the treatment develops. Given the projected increase in the global burden of cancer and limited healthcare resources, it is imperative to conduct research to define EOC patients that will benefit from anti-angiogenic specific therapy. Rationally directed anti-angiogenic therapy in women with EOC can maximize benefit, while minimizing toxicity and cost of unnecessary treatment(12).

GOG-0218 is the pivotal phase III 3-arm placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy of front-line chemotherapy with and without the anti-angiogenic agent, bevacizumab(3). In this study, subjects were randomized to one of three treatment arms. All arms included standard intravenous (IV) chemotherapy with carboplatin at an area under the curve of 6 and paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, for cycles 1 through 6, and a study maintenance treatment for cycles 2 through 22. The cycles were delivered every three weeks. Arm A represented the control treatment that included chemotherapy combined with placebo in cycles 2 through 22. Arm B comprised of concurrent chemotherapy and bevacizumab (15 mg per kilogram of body weight IV) for cycles 2 through 6 followed by placebo cycles 7 through 22. In arm C, bevacizumab was administered with chemotherapy for cycles 2-6 and continued through cycle 22. The randomized trial design with a placebo control arm allowed for the identification of factors that specifically predict which patients will and will not benefit from bevacizumab treatment. The GOG-0218 trial included the acquisition of pre-treatment plasma specimens that were available for analysis. The GOG-0218 dataset has previously been evaluated for blood and tissue-based markers(13). No prognostic or predictive association was seen for any of the markers evaluated, including VEGF-A, VEGFR-2, NRP-1 or MET. However, when comparing immunohistochemistry-based tumor CD31 microvascular density (MVD) along with tumor VEGF-A levels (>quartile (Q)3 vs ≤Q3), these markers demonstrated prognostic and potential predictive value for PFS and OS in the concurrent and maintenance bevacizumab arm (CPBB) compared to the placebo control arm (CPP).

While the immunohistochemical biomarker analysis appears promising, interest in blood-based markers exists due to ease of sample collection and longitudinal analyses, reproducible and quantifiable results, and circumvention of tumor tissue heterogeneity concerns (14–16). Multiplex ELISA technology allows for efficient evaluation of multiple soluble markers simultaneously. We have developed and optimized a protein multiplex array for the evaluation key angiogenic and inflammatory markers, termed the Angiome. The Angiome multiplex array has been approved by the NCI Biomarker Review Committee as an integrated biomarker for use in NCTN and ETCTN studies. While the full Angiome array evaluates 26 unique protein markers, we prioritized seven markers (IL6, Ang-2, osteopontin (OPN), stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), VEGF-D, IL6R, and GP130) that had been previously shown to be predictive of benefit from anti-angiogenic therapies in other solid tumors and/or associated with prognostic outcomes with EOC or implicated with ovarian carcinogenesis (17–24) for the primary inferential analysis. The main objectives of this study were to evaluate if the plasma Angiome components (IL6, Ang-2, OPN, SDF-1, VEGF-D, IL6R, and GP130) were associated with a therapeutic bevacizumab advantage for PFS and/or OS in women with advanced EOC treated on GOG-0218.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study design and outcomes of GOG-0218 have been previously reported (3). The clinical study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all participating centers and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. All patients provided written-informed consent. Eligible patients had histologically confirmed stage III or stage IV EOC and had undergone primary debulking surgery. Institutional review board approved, written informed consent was obtained from patients who opted to participate in the translational components of GOG-0218. This exploratory retrospective analysis was approved by the NRG Oncology Translational Science Committee, had a pre-specified analysis plan, and conforms to the reporting guidelines established by the REMARK criteria (25).

Specimens

Available plasma specimens previously collected from women registered to GOG-0218, treated on either the CPP or CPBB arms, who were eligible and provided consent to the use of their specimens and clinical information for future cancer research were evaluated. Baseline peripheral blood samples were collected into EDTA anticoagulant vacutainers and centrifuged within 2 hours of collection at 3,500 x g at 4°C for 10 minutes. Plasma was aliquoted into cryovials, snap frozen, and shipped on dry ice for storage at −80°C at the centralized GOG Tissue Bank. Samples were subsequently shipped to the Duke Molecular Reference Laboratory, thawed on ice, re-aliquoted based on specific assay requirements, and stored at −80°C. All sample and data handling procedures were fully compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and the study was conducted under the Duke Institutional Review Board approval.

Laboratory Testing

Plasma samples from GOG-0218 were assessed using multiplex array technology (CiraScan™ platform from Aushon BioSystems Inc., Billerica, MA). Samples were analyzed for seven biomarkers (IL6, Ang-2, OPN, SDF-1, VEGF-D, IL6R, and GP130) following manufacturer’s protocols. Plasma samples were thawed on ice, centrifuged at 20,000 x g for 5 minutes to remove precipitate, and subsequently loaded onto multiplex plates with standard protein controls as previously reported (26). Samples and standards were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour shaking at 450 rpm (Lab-Line Titer Plate Shaker, Model 4625, Barnstead, Dubuque, IW). Plates were washed, biotinylated secondary antibody was added, and plates were incubated for 30 minutes. After washes, streptavidin-HRP was added, plates were incubated for 30 minutes, washed, and SuperSignal substrate was added. Images were taken within 10 minutes, followed by image analysis using the array analyst software. All marker data represent the average of duplicate measures multiplied by dilution and all analyses were conducted while blinded to clinical outcome.

Statistical Considerations

The primary objective was to determine whether components of the plasma Angiome panel (IL6, Ang-2, OPN, SDF-1, VEGF-D, IL6R, and GP130) were predictive of a therapeutic advantage in PFS of bevacizumab treatment in women with advanced EOC treated on GOG-0218. The secondary objective was to determine if these biomarkers were predictive of OS. The predictive analyses for both PFS and OS were conducted using a protein marker by treatment interaction term within the framework of a Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for baseline covariates of age, stage/debulking status, and performance status as additive effects. Results presented included hazard ratios and associated confidence intervals, along with p-values for Wald’s test for interaction. An exploratory analysis was performed to identify markers prognostic of survival outcomes for women with advanced EOC. The prognostic analyses for PFS and OS were performed using the Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for baseline covariates. PFS analyses were stratified by treatment, due to the differences in outcome which were previously observed.

Prior to performing the analyses, biomarkers were inspected for outliers, defined as any values either less than Q1-1.5xIQR or greater than Q3+1.5xIQR, where Q1 and Q3 are the first and third quartiles, respectively, and IQR is the inter-quartile range. The similarity among biomarkers at baseline was analyzed using hierarchical clustering. Biomarkers were natural log transformed for the predictive and prognostic analyses, and analyzed as continuous measures.

Additional exploratory and sensitivity analyses were conducted. The predictive and prognostic analyses for both PFS and OS were repeated using the Cox rank score test, which is robust against outliers, as well as with the outliers removed for sensitivity analysis. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to illustrate differences in PFS and OS for IL6 dichotomized at the median as “Low” versus “High”. Cut-point optimization using conditional inference trees was performed for selected markers for PFS and OS exploratory purposes. Kaplan-Meier plots were presented for the marker levels dichotomized at the resulting PFS and OS cut-point values. It is noted that the primary inferential analyses are based on continuous biomarkers. All analyses based on using cut-points were considered to be exploratory and were exclusively used for the purpose of illustration and generation of hypotheses. The cut-points were optimized based on data in the control arm, which may exaggerate the predictive effect (27).

The primary analyses, the interaction of seven markers with bevacizumab with respect to PFS, were adjusted for multiple testing so as to control the family-wise error rate at the two-sided 0.05 level. More specifically, the seven analyses were conducted at the Bonferroni adjusted two-sided alpha level of 0.007=0.05/7. The secondary and exploratory analyses were not adjusted for multiple testing. For these two-sided unadjusted p-values and two-sided 95% confidence intervals are presented.

The R statistical environment [R] version 3.4.4 (28), along with extension packages survival (v 2.41-3) (29), partykit (v 1.2-0)(30, 31), and tidyverse (v 1.2.1) (32), were used to conduct the statistical analyses. The Knitr extension package was used for generation of dynamic reports (33).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the 1248 patients who enrolled to either the control or bevacizumab-throughout arm on the parent protocol, baseline EDTA plasma samples were available for analysis on 751 patients: 384 patients in the control arm and 367 in the bevacizumab-throughout arm (Supplemental Fig. S1). The demographics and clinical characteristics of these patients in the biomarker evaluable population appeared to be similar to those in the intent-to-treat population of the parent study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the biomarker cohort and overall patient population

| Biomarker Evaluable Population | Intent-to-Treat Population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Bevacizumab | Control | Bevacizumab | ||

| 384 | 367 | 625 | 623 | ||

| Age | Median (range) | 60 (26-84) | 60 (28-89) | 60 (25-86) | 60 (22-89) |

| Stage/Debulking Status | III (macroscopic, ≤1cm) | 146 (38.0%) | 137 (37.3%) | 218 (34.9%) | 216 (34.7%) |

| III (>1cm) | 144 (37.5%) | 128 (34.9%) | 254 (40.6%) | 242 (38.8%) | |

| IV | 94 (24.5%) | 102 (27.8%) | 153 (24.5%) | 165 (26.5%) | |

| GOG Performance Status | 0 | 181 (47.1%) | 180 (49.0%) | 311 (49.8%) | 305 (49.0%) |

| 1 | 178 (46.4%) | 161 (43.9%) | 272 (43.5%) | 267 (42.9%) | |

| 2 | 25 (6.5%) | 26 (7.1%) | 42 (6.7%) | 51 (8.2%) | |

| PFS | Median | 10.3 | 15.3 | 10.3 | 14.1 |

| OS | Median | 39.9 | 43.3 | 39.3 | 39.7 |

The relationships between outcome, PFS and OS, and each of the baseline covariates (age, stage/debulking status, and performance status) are summarized in Supplemental Table S2. Stage/debulking status and performance status were associated with PFS and OS, while age was only associated with OS.

Baseline Biomarker Measurement

Multiplex analyses demonstrated good sensitivity and coefficients of variation (CVs) ranged from 1-6% for all markers, with the exception of SDF-1, which was 11.9%. The medians for all biomarkers at baseline were: 264.2 pg/ml for Ang-2, 369.1 ng/ml for GP130, 22.1 pg/ml for IL6, 34.8 ng/ml for IL6R, 986.2 ng/ml for OPN, 3.0 ng/ml for SDF-1, 1.0 ng/ml for VEGF-D (Supplemental Table S3).

Predictive Marker Identification

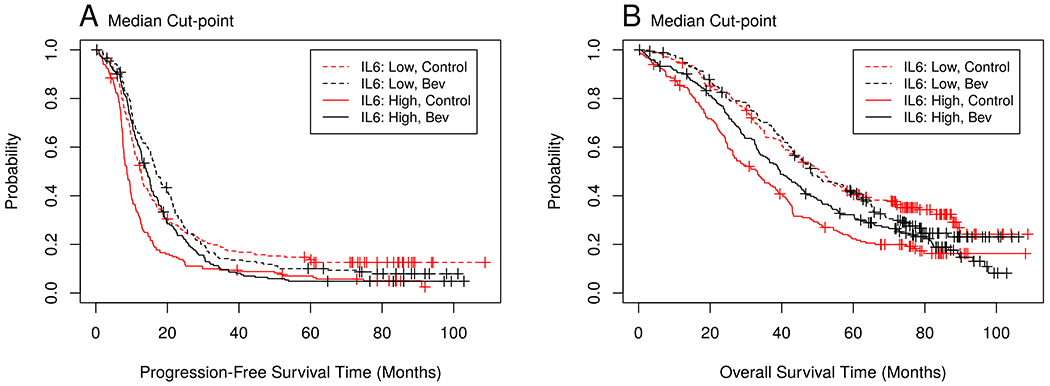

The primary objective was to determine whether any marker (IL6, Ang-2, OPN, SDF-1, VEGF-D, IL6R, and GP130) was predictive of PFS for women treated with bevacizumab on GOG-0218. The secondary objective was to determine if any of these biomarkers were predictive of OS for women treated with bevacizumab on GOG-0218. The analysis of the interaction with bevacizumab treatment (predictive efficacy) and each biomarker marker was assessed on the basis of a continuous quantification of the latter and accounted for the following baseline covariates: age, stage, debulking, and performance status. IL6 was found to be predictive of a therapeutic advantage with bevacizumab for PFS (p=0.007) (Table 2). For illustrative purposes, we present Kaplan-Meier plots with IL6 dichotomized at the median. Patients with high IL6 levels (>median value of 22.1 pg/ml) treated with bevacizumab throughout had longer PFS (14.2 vs. 8.7 months; hazard ratio (HR), 0.63; confidence interval (CI), (0.51-0.79) compared to those treated with placebo (Table 3, Figure 1A). In contrast, there was no improvement in PFS for those with low IL6 levels treated with bevacizumab compared to placebo (16.9 vs. 12.6 months; HR, 0.93; CI, (0.74-1.15)) (Table 3, Figure 1A).

Table 2.

Predictive associations between biomarkers and survival outcomes

| Predictive Associations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS | OS | |||||

| Marker | Control HR (CI) | Bev HR (CI) | p-value1 | Control HR (CI) | Bev HR (CI) | p-value1 |

| IL6 | 1.22 (1.08,1.37) | 1.06 (0.94,1.2) | 0.007 | 1.29 (1.17,1.43) | 1.07 (0.97,1.18) | 0.003 |

| OPN | 1.6 (1.2,2.13) | 1.4 (1.07,1.83) | 0.086 | 1.73 (1.39,2.16) | 1.47 (1.19,1.8) | 0.152 |

| VEGF-D | 0.93 (0.7,1.25) | 1.01 (0.69,1.48) | 0.598 | 1.04 (0.83,1.3) | 1.12 (0.84,1.49) | 0.702 |

| Ang-2 | 1.14 (0.92,1.4) | 1.1 (0.83,1.45) | 0.655 | 1.24 (1.04,1.49) | 1.09 (0.89,1.35) | 0.248 |

| IL6R | 0.82 (0.5,1.35) | 0.94 (0.61,1.45) | 0.664 | 0.77 (0.52,1.14) | 0.87 (0.62,1.2) | 0.786 |

| GP130 | 0.96 (0.49,1.89) | 0.87 (0.6,1.28) | 0.717 | 1 (0.59,1.69) | 0.85 (0.64,1.13) | 0.524 |

| SDF-1 | 1.06 (0.92,1.21) | 1.08 (0.92,1.26) | 0.841 | 1.02 (0.91,1.14) | 1.08 (0.95,1.23) | 0.533 |

Unadjusted p-values for interaction with bevacizumab treatment (predictive efficacy): explored based on continuous values; the model accounted for the following covariates – age, stage, debulking, and performance status. Confidence intervals for PFS were 99.3% CI’s while 95% CI’s are presented for OS.

HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval; BEV=bevacizumab; 95% CI’s are presented; Medians are presented in months.

Table 3.

Predictive associations IL6 survival outcomes dichotomized by cut-points

| IL6 Cut-point | N | PFS months (Control) | PFS months (BEV) | HR (CI) | OS months (Control) | OS months (BEV) | HR (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | |||||||

| Low (≤22.1 pg/ml) | 376 | 12.6 | 16.9 | 0.93 (0.74,1.15) | 50.8 | 48.5 | 1.09 (0.85,1.39) |

| High (>22.1 pg/ml) | 375 | 8.7 | 14.2 | 0.63 (0.51,0.79) | 33.1 | 39.6 | 0.78 (0.62,0.98) |

| PFS Optimized Cut-point | |||||||

| Low (≤21.4 pg/ml) | 361 | 12.7 | 16.9 | 0.92 (0.73,1.14) | 52.0 | 48.5 | 1.07 (0.83,1.38) |

| High (>21.4 pg/ml) | 390 | 8.7 | 14.2 | 0.66 (0.53,0.81) | 32.7 | 39.6 | 0.81 (0.64,1.01) |

| OS Optimized Cut-point | |||||||

| Low (≤90.2 pg/ml) | 653 | 11.5 | 15.8 | 0.86 (0.73,1.01) | 43.2 | 45.6 | 1.06 (0.89,1.27) |

| High (>90.2 pg/ml) | 98 | 6.8 | 13.0 | 0.4 (0.26,0.62) | 17.5 | 36.0 | 0.44 (0.28,0.7) |

HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval; BEV=bevacizumab; 95% CI’s are presented; Medians are presented in months.

Figure 1. Association between IL6 and survival outcomes.

Figure 1A. The progression-free survival (PFS) Kaplan-Meier curve shows the prognostic and predictive value of IL6 for PFS. IL6 levels were dichotomized at the median cut-point of 22.1 pg/ml. The median PFS in the control/low IL6 cohort was 12.6 months versus 16.9 months in the bevacizumab treated patients with low IL6. The difference in median PFS was more pronounced in the high IL6 cohort (8.7 months in the control arm vs. 14.2 months in the bevacizumab arm). Figure 1B. The overall survival (OS) curve demonstrates the prognostic and predictive value of IL6 for OS. IL6 levels were dichotomized at the median value of 22.1 pg/ml. The median OS in the control/low IL6 vs bevacizumab/low IL6 cohorts was similar (50.8 vs. 48.5 months). However, there was a larger difference in median OS between the control and bevacizumab high IL6 cohort (33.1 months in the control arm vs. 39.6 months in the bevacizumab arm).

The secondary analysis was to determine whether any of the seven markers tested as continuous variables were predictive of OS for women treated with bevacizumab on GOG-0218. As observed for PFS, IL6 was again found to be predictive of a therapeutic advantage with bevacizumab for OS (p=0.003) (Table 2). Patients with high IL6 levels (>median value of 22.1 pg/ml) treated with bevacizumab throughout had longer OS [39.6 vs. 33.1 months; HR, 0.78; CI, (0.62-0.98)] compared to those treated with placebo (Table 3, Figure 1B). Patients with low IL6 levels treated with bevacizumab had shorter OS [48.5 vs. 50.8 months; HR, 1.09; CI, (0.85-1.39)] compared to those treated with placebo (Table 3, Figure 1B). In addition to presenting the continuous, log-adjusted marker level results, we also conducted a quartile analysis of IL6 for both PFS and OS, shown in Supplemental Table S4. None of the other markers (Ang-2, OPN, SDF-1, VEGF-D, IL6R, or GP130) were predictive of a therapeutic advantage or disadvantage with bevacizumab.

Optimization IL6 cut-points

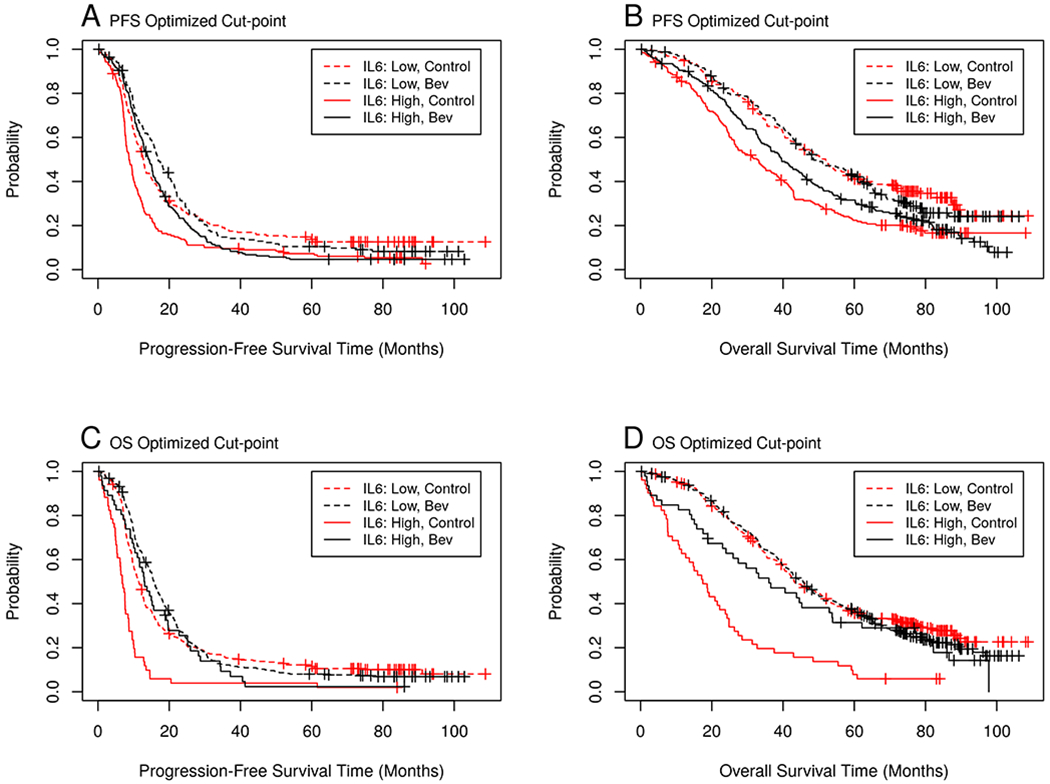

To further explore and illustrate the interaction between IL6 and bevacizumab with respect to PFS and OS, we used conditional inference trees to determine the optimal cut-point. In optimizing the cut-point, we used the control arm data in order to avoid confounding due to differences in outcome between arms. The optimal cut-point of IL6 based on PFS was 21.4 pg/ml while the optimal cut-point of IL6 based on OS was 90.2 pg/ml. The PFS-derived IL6 cut-point was found to be very similar to the median IL6 value (21.4 pg/ml vs. 22.1 pg/ml, respectively) (Table 3), however, the OS-derived IL6 cut-point was much higher, at the 87th percentile. For the small subset of patients (98 out of 751) with high IL6 based on the OS-derived cut-point, there was a seemingly large benefit for those treated with bevacizumab compared to the control group for both the PFS endpoint [13.0 vs. 6.8 months; HR, 0.4; CI, (0.26-0.62)] (Table 3, Figure 2C) and the OS endpoint [36.0 vs. 17.5 months; HR, 0.44; CI, (0.28-0.70)] (Table 3, Figure 2D). In contrast, dichotomizing IL6 by the median or PFS-derived cut-point resulted in only a 6-7 month difference in median OS when treated with bevacizumab compared to placebo (Table 3, Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Cut-point optimization for IL6.

The survival curve demonstrates the prognostic and predictive value of IL6 at various cut-point values for the Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS. Figure 2A and 2C. Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS outcome with IL6 dichotomized by PFS-optimized cut-point (21.4 pg/ml) (2A) or by OS-optimized cut-point (90.2 pg/ml) (2C). Figure 2B and 2D. Kaplan-Meier curves for OS outcome with IL6 dichotomized by PFS-optimized cut-point (21.4 pg/ml) (2B) or by OS-optimized cut-point (90.2 pg/ml) (2D).

Multivariate Analyses

Since it has been well established that both soluble IL6R and GP130 can bind IL6 in vivo (33, 34), we performed an ad hoc analysis to assess the synergistic effects among the treatment, IL6, and either IL6R or GP130 with respect to outcome (PFS and OS). To this end, we employed 3-way multiplicative Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for age, stage/debulking status, and performance status as additive effects (Supplemental Table S5). There was no statistical evidence to support any 3-way interaction between treatment, IL6, and either IL6 binder, IL6R, or GP130 (Supplemental Tables S6-S9).

Prognostic Marker Identification

Exploratory analyses were also performed to identify whether IL6, Ang-2, OPN, SDF-1, VEGF-D, IL6R, and/or GP130 were prognostic of outcome for women enrolled on GOG-0218. Both IL6 and OPN were found to be negative prognostic markers for PFS (HR, 1.14; CI, (1.07-1.21); p<0.001) and (HR, 1.48; CI, (1.28-1.7); p<0.001), respectively. IL6 and OPN were also found to be negative prognostic markers for OS (HR, 1.17; CI, (1.1-1.26); p < 0.001) and (HR, 1.59; CI, (1.37-1.84); p<0.001), respectively. No prognostic associations were observed for any of the other biomarkers tested for either PFS or OS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prognostic associations between biomarkers and survival outcomes.

| Prognostic Associations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS | OS | |||

| Marker | HR (CI) | p-value1 | HR (CI) | p-value1 |

| OPN | 1.48 (1.28,1.7) | 4.836e-8 | 1.59 (1.37,1.84) | 1.284e-9 |

| IL6 | 1.14 (1.07,1.21) | 4.148e-5 | 1.17 (1.1,1.26) | 4.176e-6 |

| Ang-2 | 1.13 (1,1.27) | 0.055 | 1.19 (1.04,1.36) | 0.012 |

| SDF-1 | 1.07 (0.99,1.15) | 0.078 | 1.05 (0.97,1.14) | 0.224 |

| IL6R | 0.89 (0.71,1.12) | 0.322 | 0.82 (0.65,1.05) | 0.115 |

| GP130 | 0.89 (0.7,1.14) | 0.373 | 0.88 (0.68,1.15) | 0.350 |

| VEGF-D | 0.97 (0.82,1.14) | 0.675 | 1.07 (0.9,1.28) | 0.425 |

Unadjusted p-values for the Wald test: explored based on continuous values; the model accounted for the following covariates – age, stage, debulking, and performance status. PFS was stratified by treatment. 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented.

HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval; BEV=bevacizumab; 95% CI’s are presented; Medians are presented in months.

Discussion

IL6 signaling plays an important role in carcinogenesis across a variety of solid tumors, including ovarian cancer, regulating proliferation, adhesion, invasion as well as angiogenesis and immunologic functions (22). Furthermore, IL6 has been shown to be elevated in ovarian cancer patients exhibiting paraneoplastic thrombocytosis and has been suggested to be a key mediator driving this biology (35). Our findings indicate that IL6 may identify patients most likely to benefit from the addition of bevacizumab to standard of care chemotherapy in women with newly diagnosed advanced EOC. Furthermore, IL6 plasma levels were negative prognostic markers for both PFS and OS in women treated on GOG-0218. These paradoxical findings suggest that the patients destined to do worse (high IL6 levels) may be the most likely to benefit from treatment with bevacizumab.

These data confirm previous findings where IL6 levels were both prognostic for survival in EOC (17) as well as predictive of survival benefit in patients with metastatic renal cancer in two independent anti-angiogenic therapeutic trials; one evaluating bevacizumab combined with interferon alfa and the other evaluating pazopanib (36, 37). Moreover, risk score analyses based on IL6 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) suggest that IL6 is a predictive marker of bevacizumab efficacy in patients with pancreatic cancer (26). The range of median IL6 levels in the renal, pancreatic, and our current ovarian study is 13.1-22.1 pg/ml and represents minimal variation. In addition, these median IL6 levels are strikingly similar to IL6 level measured in our phase II clinical trial of nintedanib in women with recurrent ovarian cancer (23.8 pg/ml) (38). In contrast, no association between IL6 levels and treatment response was observed in women with recurrent ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer treated with or without pazopanib in a randomized phase II study (39). The median IL6 levels identified may be specific to disease type and patient population and could also vary due to differences between processing, assays, prior therapy, and patient characteristics.

In order to identify the optimal cut-point that would have clinical relevance to direct front-line concurrent and maintenance bevacizumab therapy in women with advanced epithelial ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancers, we tested various IL6 cut-points. These exploratory cut-points included the median value, as well as performing cut-point optimization analyses based on both PFS and OS. The PFS-derived cut-point was very similar results to that of the median value (21.4 pg/ml vs 22.1 pg/ml) and indicated that high IL6 using either the median or PFS-derived cut-point was associated with bevacizumab efficacy. Based on either the median or PFS cut-points, women with high IL6 levels treated with bevacizumab appear to have a reduction in the hazard of disease progression and death, respectively. Interestingly, when applying the OS optimized cut-point (90.2 pg/ml, equivalent to the 87% quantile), we observed that women with high IL6 treated with bevacizumab throughout had the greatest reduction in the hazard of disease progression and death. Using the OS-derived cut-point, we were able to identify a highly sensitive subset of the population with extremely high levels of IL6 that appear to benefit the most with the addition of front-line bevacizumab therapy. These findings suggest that IL6 may assist in directing front-line bevacizumab therapy to maximize benefit and minimize toxicity. However, these exploratory observations must be viewed with caution as cut-point optimization may lead to exaggerated estimates of the predictive effects (27). Our findings in the IL6 low group also need to be considered carefully. The confidence interval for treatment effect in the IL6 low subgroup is too wide to confidently rule out clinically important benefit. We also point out that even if these cut-points are valid for our study, they may not be generalizable to other studies.

Since the biomarkers were chosen a priori and tested for interaction with treatment with respect to clinical outcome, we opted not to internally validate these findings using training-testing splits of the available data or cross-validation. Further testing is needed to validate the role of IL6 as a predictive biomarker before it can be used to direct clinical care. We note that the results presented here, especially the estimated effect sizes, may be sensitive to departures from the proportional hazards assumption. As with any biomarker analysis, one has to be concerned with potential confounding due to baseline covariates. While we have attempted to address this issue by adjusting for baseline covariates as additive effects in our multivariable models, we cannot rule out confounding. The relationships between outcome, PFS and OS, and each of the baseline covariates are summarized in Supplemental Table S2. The relationships between IL6 and each of the baseline covariates are illustrated in Supplemental Table S5. The upcoming NRG Oncology GY004 and GY005 studies comparing olaparib and cediranib to standard of care therapies includes evaluation of IL6 as a predictive biomarker, further extending the potential role for IL6 to guide the use of multiple anti-angiogenic therapeutic approaches. Continued evaluation of IL6 in these studies will further refine and optimize a cut-point for IL6 to be used in prospective testing. Identifying biomarkers to direct therapy is critically important to reduce cost as well as prioritize treatment sequencing in an era where alternative treatment options exist for EOC [such as Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) and immunotherapies] (12).

Previously, two separate investigators independently explored molecularly defined tumor subgroups in women who participated on the ICON7 trial (40, 41), an open-label, two-arm study in patients who had stage I to III debulked or any stage IV ovarian cancer. Gourley et al. identified two molecularly-defined groups, defined as pro-angiogenic and immune, and reported that the immune signature was prognostic for improved survival outcomes. However, the immune signature subgroup had worse PFS (HR=1.73; CI=1.12-2.68) and OS (HR=2.00; CI=1.11-3.61) when treated with bevacizumab compared to chemotherapy alone (40). Winterhoff et al. stratified patients who participated in ICON7 into four TCGA serous subgroups (proliferative, mesenchymal, immunoreactive, and differentiated subgroups) and reported that median PFS and OS improvements with bevacizumab were not greater in the differentiated and immunoreactive subtypes. In this report, patients with high-grade serous carcinomas of mesenchymal and proliferative subtypes obtained the greatest overall survival benefit from bevacizumab while those with high-grade serous proliferative subtype demonstrated a modest improvement in PFS only (41). Recently, the group updated their data and reported that only patients with the proliferative subtype had a statistically significant benefit from the addition of concurrent and maintenance bevacizumab to standard chemotherapy (median PFS 22.2 vs 12 months; HR 0.48 [95%CI 0.3-0.76], p=0.002; median OS 52.4 vs 35.3 months (HR 0.54 [95%CI 0.3-0.9], p=0.021). In this updated analysis, there was no significant improvement of PFS or OS with the addition of bevacizumab in the mesenchymal subtype (42). Collinson et al. developed a signature using VEGFR-3, α1-acid glycoprotein, mesothelin, and CA-125 that was predictive of bevacizumab response. The signature-positive group demonstrated improved median PFS in the bevacizumab arm (17.9 vs 12.4 months; P = 0.04), while the signature-negative group had improved PFS in the chemotherapy alone arm (36.3 vs 20 months, P = 0.006) (43). While none of these studies has been validated, the finding that several of the biomarker groups did not benefit from bevacizumab is worthy of further investigation.

Birrer and colleagues evaluated blood-based and tumor biomarkers from women participating in GOG-0218 and identified immunohistochemistry-based tumor CD31 microvascular density (MVD) along with tumor VEGF-A levels [>quartile Q3 vs ≤Q3] as both prognostic and predictive for concurrent and maintenance bevacizumab efficacy (13). Other markers VEGFR-2, neuropilin-1, and MET had no prognostic or predictive association with survival outcomes or bevacizumab efficacy. Buechel and colleagues conducted a GOG-0218 ancillary study evaluating the association between markers of adiposity, subcutaneous fat and visceral fat density (SFD/ VFD) measurements, derived from CT imaging and survival outcomes. Increased SFD and VFD correlated with a significantly increased risk for death (HR per 1-SD increase 1.12, 95% CI:1.05-1.19 p=0.0009 and 1.13 and 95% CI: 1.05-1.20 p=0.0006, respectively). High VFD was associated with an increased risk for death in the placebo group (HR per 1-SD increase 1.22, 95% CI: 1.09-1.37), but not in the bevacizumab group. There was no correlation between high VFD and IL6 levels (r=0.02, p=0.57) (44). Evaluation of the IL6 blood-based marker in context with the molecular profile, as well as the degree of tumor angiogenesis based on CD31 tumor staining, VEGF-A levels, and SFD/VFD may elucidate the etiology behind the survival outcome difference and improve identification of candidates most likely to benefit from incorporation of bevacizumab to front-line chemotherapy.

The development of validated predictive markers may be greatly affected by the analytic processes employed; quality and variability of sample processing; long-term storage stability, number of freeze-thaw cycles; statistical analysis, and underlying differences in tumor biology. This study was limited by the lack of monitored site-specific sample processing which may lead to variability, even with a standardized SOP provided to all sites. While the age of plasma samples varied, once samples were received by our laboratory, the samples were all treated similarly and the assays were performed according to highly standardized methods encompassing sample type tested (all EDTA plasma); the number of freeze-thaw cycles; consistent reagents from single batch plate printing and reference standards. Importantly, the assays were performed by research personnel blinded to the clinical data.

The search for biomarkers continues in an effort to provide therapeutic rationale for anti-angiogenic therapy in this era of “Precision Medicine” and as cost minimization strategies. The recent FDA approval of bevacizumab for use in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel, followed by bevacizumab maintenance therapy, for women with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer highlights the importance of identifying a biomarker to direct bevacizumab therapy (11). We have previously reported that rationally biomarker-directed bevacizumab therapy reduced cost of unnecessary treatment in our cost effectiveness analysis (12). Our current study demonstrates that the inflammatory cytokine IL6 may be predictive of therapeutic benefit from bevacizumab when combined with standard paclitaxel and carboplatin chemotherapy and our preliminary results appear promising. Our findings are consistent with previous findings in which IL6 predicted benefit from bevacizumab and pazopanib in patients with renal cell cancer, highlighting the potential intersection between inflammation and angiogenesis. Further research regarding the mechanistic effects of IL6 and its signaling partners are needed to understand the role of IL6 in ovarian carcinogenesis. Moreover, additional validation studies and integral biomarker directed clinical trials are required to determine if the plasma biomarker IL6 can accurately identify EOC patients who may benefit from bevacizumab.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

In GOG-0218, a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial, the incorporation of bevacizumab to standard chemotherapy followed by bevacizumab maintenance in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) patients led to a 3.8-month improvement in median progression-free survival, but no improvement in overall survival. We conducted an exploratory retrospective analysis evaluating several key circulating proteins and identified the inflammatory cytokine, IL6, may be predictive of therapeutic benefit from bevacizumab in these patients. This finding is consistent with results from two randomized studies in renal cancer where IL6 was observed to predict benefit to angiogenic therapy. Further prospective validation of IL6 as a predictive biomarker for angiogenic therapy in EOC patients is warranted.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the GOG Tissue Bank and administrative staff at NRG. We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the patients, their families, and the research staff who participated in this study.

The following NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions participated in this study: CTSU, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Gynecologic Oncology Network/Brody School of Medicine, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California Medical Center at Irvine-Orange Campus, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Mayo Clinic, Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania, Saitama Medical University International Medical Center, Metro-Minnesota CCOP, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Abington Memorial Hospital, Rush University Medical Center, University of Kentucky, Washington University School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Women’s Cancer Center of Nevada, Indiana University Hospital/Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Seoul National University Hospital, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Duke University Medical Center, University of Mississippi Medical Center, University of Chicago, University of Colorado Cancer Center – Anschutz Cancer Pavilion, University of California at Los Angeles Health System, Yale University, The Hospital of Central Connecticut, Northwestern University, Cooper Hospital University Medical Center, Women and Infants Hospital, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, University of New Mexico, University of Hawaii, Case Western Reserve University, Cancer Research for the Ozarks NCORP, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, University of Texas – Galveston, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, University of Virginia, University of Minnesota Medical Center-Fairview, Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Stony Brook University Medical Center, Saint Vincent Hospital, Wayne State University/Karmanos Cancer Institute, University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care, Georgia Center for Oncology Research and Education (CORE), State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Fletcher Allen Health Care, Gynecologic Oncology of West Michigan PLLC, Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Cincinnati, Carle Cancer Center, Michigan Cancer Research Consortium Community Clinical Oncology Program, Tufts-New England Medical Center, Scott and White Memorial Hospital, Cancer Research Consortium of West Michigan NCORP, Central Illinois CCOP, Delaware/Christiana Care CCOP, Northern New Jersey CCOP, Virginia Mason CCOP, Tacoma General Hospital, Wisconsin NCI Community Oncology Research Program, New York University Medical Center, Colorado Cancer Research Program NCORP, Saint Louis-Cape Girardeau CCOP, Aurora Women’s Pavilion of Aurora West Allis Medical Center, University of Illinois, Evanston CCOP-NorthShore University Health System, Kalamazoo CCOP, Missouri Valley Cancer Consortium CCOP, William Beaumont Hospital, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Kansas City CCOP, Upstate Carolina CCOP, Dayton Clinical Oncology Program, Mainline Health CCOP, Meharry Medical College Minority Based CCOP, Heartland Cancer Research CCOP and Wichita CCOP.

Funding: This research was supported by NIH/NCI R21 5R21CA185730; U10 CA027469 (GOG Administrative Office), CA37517 (GOG Statistical Office), CA114793 (GOG Tissue Bank), U10CA180822 (NRG Oncology SDMC), UG1CA189867 (NCORP), U10CA180868 (NRG Oncology Operations), CA196067 (NRG Biospecimen Bank-Columbus), P01CA142538, and U24 CA114793; Foundation for Women’s Cancer, Florence and Marshall Schwid Ovarian Cancer Research Grant; The American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Foundation; Duke Gynecologic Oncology Philanthropic Funding; and the support of the NRG Oncology including the legacy Gynecologic Oncology Group.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: AAS has received research funding from Amgen, Genentech, Sanofi, Eisai Morphotek, GlaxoSmithKline, Astellas Pharma Inc., Astex Pharmaceuticals Inc., BMS, Incyte, Tesaro, Boerhinger Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca and Exelexis; and has received consultant/advisory compensation from F Hoffman-La Roche, Genentech, Janssen, Astra-Zeneca, Precision Therapeutics, Boerhinger Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Clovis, and Tesaro. HIH is a current employee of and has stock in Genentech/Roche. RSM has received consultant/advisory compensation from Clovis and Tesaro. KST has received research funding from Genentech, Morphotek, Abbie; consultant fees from Vermillion, Genentech, Clovis, Tesaro; and Speaker’s Bureau honoraria from Roche, Merck, Clovis, Tesaro, and Astra-Zeneca. DOM has served on advisory boards for Clovis Oncology, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Gynecologic Oncology Group, Myriad, and Tesaro; has served on steering committees for Clovis Oncology, Amgen, and Immunogen; has served as a consultant to AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Tesaro, Health Analytics, and Ambry; and his institution has received research support from AbbVie, Advaxis, Agenus, Ajinomoto, Array BioPharma, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Eisai, ERGOMED Clinical Research, Exelixis, Henry Jackson Foundation, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Gynecologic Oncology Group, ImmunoGen, INC Research, inVentiv Health Clinical, Janssen Research and Development, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pharma Mar, Pfizer, PRA International, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals,Sanofi, Serono, Stemcentrx, Tesaro, and TRACON Pharmaceuticals. JNB has received research funding from Merck. MB was employed by Genentech from 4/2017-7/2018. RAB has received consulting/advisory board compensation from Amgen; Astra Zeneca; Tesaro; Clovis Oncology, Inc.; Genentech-Roche; Invitae; Merck; and VBL Therapeutics; and has also received compensation for service on data monitoring committees for Gradalis, Janssen and Morphotek. ABN has received research funding from Seattle Genetics, MedPatco, Genentech, Tracon Pharma, Acceleron Pharma, Leadiant Biosciences, and Sanofi-Aventis; and has received consultant/advisory compensation from Tracon Pharma and Eli Lilly. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kristensen G, et al. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2484–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, Judson PL, Teneriello MG, Husain A, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2039–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, Reuss A, Poveda A, Kristensen G, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oza AM, Cook AD, Pfisterer J, Embleton A, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7): overall survival results of a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:928–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.du Bois A, Kristensen G, Ray-Coquard I, Reuss A, Pignata S, Colombo N, et al. Standard first-line chemotherapy with or without nintedanib for advanced ovarian cancer (AGO-OVAR 12): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.du Bois A, Floquet A, Kim JW, Rau J, del Campo JM, Friedlander M, et al. Incorporation of pazopanib in maintenance therapy of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman RL, Brady MF, Herzog TJ, Sabbatini P, Armstrong DK, Walker JL, et al. Bevacizumab and paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy and secondary cytoreduction in recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study GOG-0213): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledermann JA, Embleton AC, Raja F, Perren TJ, Jayson GC, Rustin GJS, et al. Cediranib in patients with relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (ICON6): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1066–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FDA Approves Genentech’s Avastin (Bevacizumab) Plus Chemotherapy as a Treatment for Women With Advanced Ovarian Cancer Following Initial Surgery. Media/ Press Releases; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnett JC, Alvarez Secord A, Cohn DE, Leath CA 3rd, Myers ER, Havrilesky LJ. Cost effectiveness of alternative strategies for incorporating bevacizumab into the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:3653–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birrer MJ, Choi Y, Brady MF, Mannel RS, Burger RA, WEI W, et al. Retrospective analysis of candidate predictive tumor biomarkers (BMs) for efficacy in the GOG-0218 trial evaluating front-line carboplatin–paclitaxel (CP) ± bevacizumab (BEV) for epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:5505–. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koens L, van de Ven PM, Hijmering NJ, Kersten MJ, Diepstra A, Chamuleau M, et al. Interobserver variation in CD30 immunohistochemistry interpretation; consequences for patient selection for targeted treatment. Histopathology. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamal-Hanjani M, Quezada SA, Larkin J, Swanton C. Translational implications of tumor heterogeneity. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1258–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dijkgraaf EM, Welters MJ, Nortier JW, van der Burg SH, Kroep JR. Interleukin-6/interleukin-6 receptor pathway as a new therapy target in epithelial ovarian cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3816–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Starr MD, Bulusu A, Pang H, Wong NS, Honeycutt W, et al. Correlation of angiogenic biomarker signatures with clinical outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab. Cancer Med. 2013;2:234–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sallinen H, Heikura T, Laidinen S, Kosma VM, Heinonen S, Yla-Herttuala S, et al. Preoperative angiopoietin-2 serum levels: a marker of malignant potential in ovarian neoplasms and poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:1498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song G, Cai QF, Mao YB, Ming YL, Bao SD, Ouyang GL. Osteopontin promotes ovarian cancer progression and cell survival and increases HIF-1alpha expression through the PI3-K/Akt pathway. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1901–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Bilt AR, van der Zee AG, de Vries EG, de Jong S, Timmer-Bosscha H, ten Hoor KA, et al. Multiple VEGF family members are simultaneously expressed in ovarian cancer: a proposed model for bevacizumab resistance. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3784–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Li L, Guo X, Jin X, Sun W, Zhang X, et al. Interleukin-6 signaling regulates anchorage-independent growth, proliferation, adhesion and invasion in human ovarian cancer cells. Cytokine. 2012;59:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokoyama Y, Charnock-Jones DS, Licence D, Yanaihara A, Hastings JM, Holland CM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-D is an independent prognostic factor in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:237–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang AF, Chen MW, Huang SM, Kao CL, Lai HC, Chan JY. CD164 regulates the tumorigenesis of ovarian surface epithelial cells through the SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 axis. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nixon AB, Pang H, Starr MD, Friedman PN, Bertagnolli MM, Kindler HL, et al. Prognostic and predictive blood-based biomarkers in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: results from CALGB80303 (Alliance). Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6957–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon RM, Freidlin B. Re: Designing a randomized clinical trial to evaluate personalized medicine: a new approach based on risk prediction. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:445; author reply -6, discussion 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2018.

- 29.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torsten H, Zeileis A. Partykit: A Modular Toolkit for Recursive Partytioning in R. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2015;16:3905–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torsten H, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased Recursive Partitioning: A Conditional Inference Framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2006;15:651–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadley W Tidyverse: Easy Install and Load the ‘Tidyverse’. R package version 1.2.1. 2017.

- 33.Xie Y Knitr-package: A general-purpose tool for dynamic report generation in R. R package version 1.20. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garbers C, Aparicio-Siegmund S, Rose-John S. The IL-6/gp130/STAT3 signaling axis: recent advances towards specific inhibition. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;34:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stone RL, Nick AM, McNeish IA, Balkwill F, Han HD, Bottsford-Miller J, et al. Paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:610–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nixon AB, Halabi S, Shterev I, Starr M, Brady JC, Dutcher JP, et al. Identification of predictive biomarkers of overall survival (OS) in patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) treated with interferon alpha (I) with or without bevacizumab (B): Results from CALGB 90206 (Alliance). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:4520–.24220563 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tran HT, Liu Y, Zurita AJ, Lin Y, Baker-Neblett KL, Martin AM, et al. Prognostic or predictive plasma cytokines and angiogenic factors for patients treated with pazopanib for metastatic renal-cell cancer: a retrospective analysis of phase 2 and phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:827–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Secord AA, McCollum M, Davidson BA, Broadwater G, Squatrito R, Havrilesky LJ, et al. Phase II trial of nintedanib in patients with bevacizumab-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:555–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson DL, Sill MW, Coleman RL, Sood AK, Pearl ML, Kehoe SM, et al. Paclitaxel With and Without Pazopanib for Persistent or Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gourley C, McCavigan A, Perren T, Paul J, Michie CO, Churchman M, et al. Molecular subgroup of high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) as a predictor of outcome following bevacizumab. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:5502–. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kommoss S, Winterhoff B, Oberg AL, Konecny GE, Wang C, Riska SM, et al. Bevacizumab May Differentially Improve Ovarian Cancer Outcome in Patients with Proliferative and Mesenchymal Molecular Subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3794–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kommoss S, Heitz F, Winterhoff BJN, Wang C, Sehouli J, Aliferis C, et al. Significant overall survival improvement in proliferative subtype ovarian cancer patients receiving bevacizumab. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36:5520–. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collinson F, Hutchinson M, Craven RA, Cairns DA, Zougman A, Wind TC, et al. Predicting response to bevacizumab in ovarian cancer: a panel of potential biomarkers informing treatment selection. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5227–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buechel M, Enserro D, Burger RA, Brady MF, Wade K, Secord AA, et al. Correlation of imaging and plasma-based biomarkers to predict response to bevacizumab in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC): A GOG 218 ancillary data analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36:5507–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.