Abstract

Purpose:

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is a common, deadly cancer that is challenging both to diagnose and to manage. Its hallmark is an expansive, desmoplastic stroma characterized by high mechanical stiffness. In this study, we sought to leverage this feature of PDA for two purposes: differential diagnosis and monitoring of response to treatment.

Experimental Design:

Harmonic Motion Imaging is a functional ultrasound technique that yields a quantitative relative measurement of stiffness suitable for comparisons between individuals and over time. We used HMI to quantify pancreatic stiffness in mouse models of pancreatitis and PDA as well as in a series of freshly resected human pancreatic cancer specimens.

Results:

In mice, we learned that stiffness increased during progression from pre-neoplasia to adenocarcinoma, and also effectively distinguished PDA from several forms of pancreatitis. In human specimens, the distinction of tumors versus adjacent pancreatitis or normal pancreas tissue was even more stark. Moreover, in both mice and humans, stiffness increased in proportion to tumor size, indicating that tuning of mechanical stiffness is an ongoing process during tumor progression. Finally, using a brca2–mutant mouse model of PDA that is sensitive to cisplatin, we found that tissue stiffness decreases when tumors respond successfully to chemotherapy. Consistent with this observation, we found that tumor tissues from patients who had undergone neoadjuvant therapy were less stiff than those of untreated patients.

Conclusions:

These findings support further development of HMI for clinical applications in disease staging and treatment response assessment in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Statement of translational relevance

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is a deadly cancer that is challenging to diagnose, manage, and treat. Incipient pancreatic tumors can be difficult to distinguish from mass-forming pancreatitis, and once a patient is diagnosed and treatment begins, monitoring typically requires waiting months for changes in tumor size to become apparent by cross sectional imaging. Harmonic Motion Imaging (HMI) provides a non-invasive, quantitative measure of relative tissue stiffness suitable for comparisons between individuals and over time. We effectively used HMI in both mouse models and human specimens to functionally distinguish pancreatic tumors from pancreatitis and delineate the margins of tumors otherwise not apparent with traditional ultrasound. Moreover, we learned that the mechanical properties of PDA mature during tumor growth, and that tumors responding to chemotherapy become softer in association to regression. These findings provide a translational rationale for the clinical implementation of HMI for pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is an aggressive malignancy with a median survival time of 6 months and a 5-year survival rate of just 8%(1). A pathognomonic feature of the disease is the deposition of an expansive, desmoplastic stroma that can comprise up to 90% of the tumor tissue. Stromal cells deposit and remodel profuse quantities of extracellular materials, forming a structured matrix that elevates interstitial fluid pressure, collapses tumor blood vessels, and obstructs tissue perfusion (2,3). As a consequence, these tumors are pale and hard to the touch. This poor perfusion also contributes to the striking primary chemoresistance of pancreatic tumors, particularly to labile chemotherapeutic agents with a small therapeutic index (4). Multiple clinical trials are ongoing that target various elements of the PDA stroma as a means to improve drug delivery and, by extension, the efficacy of existing chemotherapies.

The diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma often follows a protracted period of diagnostic uncertainty. The earliest signs of pancreatic cancer are nonspecific, such as abdominal pain, gastrointestinal distress, and unexplained weight loss (5) and there is no sensitive and specific blood test yet available. The first definitive diagnostic evidence is typically either cross-sectional imaging, such as contrast CT or MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), which offers a close view of the pancreas via an endoscope passed through the esophagus and into the stomach. However, even with state-of-the-art imaging, uncertainty often persists, particularly in discerning pancreatic cancer from mass-forming pancreatitis (6). Inflammation of the pancreas due to non-malignant etiologies is a far more prevalent pathology than cancer and can share many features on imaging. Attempts to sample the tumor by EUS–guided biopsy hold the potential for a definitive diagnosis, but these have a high false negative rate due to the intricate association of PDA with adjacent inflammation (6). The differential diagnosis of PDA versus pancreatitis is clinically consequential: an unneeded intervention for cancer can exacerbate pancreatitis and diminish quality of life whereas the failure to resect a tumor can forestall the best opportunity to extend survival.

Given the distinct mechanical properties of PDA and the prominent role of ultrasound in the management of this disease, we sought to translate an ultrasound-based technique for the quantification of tissue stiffness for applications in differential diagnosis and disease monitoring in pancreatic cancer. Many existing techniques enable the measurement of tissue stiffness (or elastography) by assessing the perturbation of a tissue in response to an external, internal, or intrinsic mechanical stimulus. External perturbation techniques include quasi-static (7), transient (8), and dynamic elastography (9), as well as magnetic resonance elastography (MRE). These techniques are inherently compromised by signal attenuation and the complex interactions of the mechanical waves with different tissues, which lead to inaccurate measurements (10). Among the internal perturbation techniques, including vibroacoustography (11), Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) (12), and Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) imaging (13), most rely on a single ultrasound transducer to both produce a deformation and image the resulting displacement. Tissue non-linearity, attenuation of the ultrasound propagation through tissue layers, and the power limits of imaging transducers place constraints on the acoustic radiation force that can be applied through an imaging transducer, and by extension its sensitivity and depth of application (10). In addition, variations in the speed of sound and respiratory motion can overshadow the perturbation if the latter is too weak.

Harmonic Motion Imaging (HMI) overcomes these limitations by separating the perturbation and imaging functions between two transducers. The first is dedicated to imparting a focused oscillation at depths over several centimeters within a tissue, thereby overcoming attenuation limitations; the high power output of the AM signal in HMI makes it possible to reach deep organs such as the pancreas and assess the wide range of stiffness associated with different pathological states (14). The second transducer is used to image and measure the resulting oscillatory tissue displacement at the focus, thereby separating the speed of sound and respiratory artifacts that typically lead to static (as opposed to oscillatory) motion (fig. S1A,B). Because the force generated by the focused transducer can be controlled and localized to within a few millimeters and the corresponding amount of deformation is relatively small (<1%), the amplitude of the displacement can be directly related to the underlying tissue stiffness. In addition, the specific AM frequency of the displacement signal enables a highly efficient filter for noise, variations in the speed of sound, and physiologic motion – crucial capabilities when imaging an abdominal organ. Prior studies in tissue–mimicking phantoms and in ex vivo canine liver specimens demonstrated that displacement measured by HMI is highly correlated with Young’s modulus, a standard unit of measure for mechanical stiffness (R2= 0.95) (15). We previously demonstrated that HMI can generate two-dimensional elasticity maps of mouse abdominal organs and found they accurately depict the relative stiffness of tissues (16). Most recently, we performed HMI on postsurgical breast specimens and found the technique is capable of mapping and differentiating stiffness in normal versus diseased samples (17). Most importantly, two groups have recently succeeded in engineering focused ultrasound transducers into an endoscope, enabling even greater access to internal organs such as the pancreas (18). Given the prominent role of endoscopic ultrasound in the clinical diagnosis and management of pancreatic disease, these features suggest that HMI may be particularly well suited for applications in this setting.

Here we examine the potential clinical utility of HMI using both genetically engineered mouse models of PDA as well as freshly–resected human pancreatic cancer specimens. In mice, we test the hypothesis that stiffness can be used to distinguish PDA from genetically– or chemically–induced pancreatitis. In addition, we examine the association of tissue stiffness with murine pancreatic tumor growth and response to chemotherapy. These preclinical studies are then complemented with evidence from human patients by using HMI to measure tissue stiffness in a series of freshly resected PDA specimens. We assess the ability of HMI to distinguish areas of frank adenocarcinoma versus nearby normal and inflamed pancreas parenchyma and we evaluate the association of HMI-inferred stiffness with tumor size. Finally, we compare postsurgical specimens from patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or chemoradiation therapy to those from untreated patients.

Materials and Methods

See Supplementary Information for additional details.

B-mode ultrasound imaging

Mice bearing nascent pancreatic tumors were initially identified using a Fuji Vevo 2100 high resolution ultrasound with a 35MHz transducer for mice housed within the animal barrier facility (fig. S1C). Subsequent anatomical imaging outside the barrier facility was performed using a Verasonics 18.5-MHz diagnostic probe (L22-14v).

Harmonic Motion Imaging

The acoustic radiation force was generated by a 93-element phased array transducer (H-178, Sonic Concept Inc. Bothell WA, USA). An amplitude-modulated (AM) signal (frequencies: fcarrier = 4.5 MHz and fAM = 25 Hz) was sent by a dual-channel arbitrary waveform generator (AT33522A, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) to drive all 93 channels simultaneously after amplification by a 50-dB power gain RF amplifier (325LA, E&I, Rochester, NY, USA). The resulting beam induced a 50-Hz harmonic tissue oscillatory motion at the transducer focus. A calibration performed in water showed that the acoustic power produced by this system was 5.04 W. Further details on the HMI system are provided in Hou et al.(19).

A Vantage 256 system (Verasonics, Bothell, WA, USA) was used to operate the imaging probe in a plane-wave beam sequence with a framerate of 1 kHz. Two different phased arrays from ATL/Philips (Bothell, WA, USA) were used. For mouse experiments, the RF acquisition was performed using a P12-5 probe (104 elements, aperture = 12 mm, center frequency fc = 7.5 MHz) for higher resolution. In the case of human specimens, higher penetration and field-of-view were obtained with a P4-2 phased array (64 elements, aperture = 20 mm, fc = 2.5 MHz). Raster scans were performed by mechanically moving the transducer using a 3D positioning system (Velmex Inc., Bloomfield, NY, USA) in a raster scan format. At each position, the tissue was mechanically oscillated for 0.2 s, during which 200 channel data frames (10 oscillation cycles) were acquired using a plane wave imaging sequence. Delay-and-sum beamforming using GPU-based sparse-matrix operation (20) was then performed to reconstruct the RF frames. The FUS fundamental frequency and its harmonics were then filtered out of the RF frames to remove any noise interference between the two ultrasound beams.

HMI displacement estimation

The incremental displacement along the axis of ultrasound transmission was estimated using a 1D cross-correlation algorithm (21) along each beam line. A bandpass filter around the displacement frequency (50 Hz) was applied to further reduce noise. The median peak-to-peak displacement amplitude was calculated for each pixel.

To reconstruct the entire imaging plane, attenuation was compensated by Dz = Dz0e2fα(z0−z) where Dz and Dz0 are the displacements measured at depth z and at the focal depth z0, f is the imaging frequency, and α is the attenuation coefficient fixed at 0.5 dB·cm−1·MHz−1.

For each 2D imaging plane, a ROI was manually segmented on the B-mode acquired with the imaging probe (fig. S1C). The HMI values presented in this work are mean values±standard deviation. Two-tailed t-tests with a threshold p-value of 0.05 were used to determine the significance of the difference.

Mouse models

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All the animals were anesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane in oxygen throughout the imaging procedures. Mice were placed in supine position on a heating pad with their abdomen depilated. A container filled with degassed water was placed with an acoustically-transparent window above their abdomen and coupled with degassed ultrasound gel.

Five different types of mice were used in this study. Wild-type BalbC mice (WT mice, N = 32) were used as normal controls. K-rasLSL.G12D/+; PdxCretg/+ mice (KC mice, N = 24) which spontaneously develop pancreatitis and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) lesions, a microscopic precursor of PDA (22). K-rasLSL.G12D/+; p53R172H/+; PdxCretg/+ (KPC mice, N= 30), develop autochthonous pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas with pathophysiological and molecular features resembling human PDA (4). Tumor development in the KPC model is readily visualized using very high resolution (35 MHz) B-mode ultrasound (fig. S1C), with normal pancreatic tissue appearing homogenously hyperechoic (bright) and inflamed/premalignant pancreas becoming progressively more mottled and heterogeneous (23). Nascent pancreatic tumors are apparent as a solid, hypoechoic mass as small as 2mm diameter (23). However, 35MHz ultrasound imaging cannot be applied clinically because this high frequency of ultrasound required can only penetrate up to ~1cm into tissues. K-rasLSL.G12D/+; p53R172H/+; PdxCretg/+; Brca2Flox/Flox (KPCB2F/F mice, N= 8) rapidly develop Brca2 deficient pancreatic tumors (24). Elastase-IL-1β transgenic mice (Ela-IL1β mice, N = 8) express the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β from the acinar cell specific elastase gene, resulting in chronic pancreatitis with inflammatory influx and local edema, but minimal ECM deposition (25).

Additional details are presented in supplementary methods.

Pancreatitis induction

The secretory peptide cerulein was administered in some experiments to induce or exacerbate pancreatitis. Short-term treatment of wild type mice with cerulein induces a mild, acute pancreatitis that lacks ECM deposition. By contrast, treatment of KC mice with cerulein intensifies their basal pancreatitis phenotype, producing an exuberant inflammatory reaction with substantial desmoplasia (26). We treated 10 WT mice and 14 tumor-free KC mice with intraperitoneal injections of cerulein (250 mg kg−1) daily for 5 days (27). Mice were imaged one week after induction.

Human tissue specimens

All work with clinical specimens was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Belmont report and following human subjects protocol approval by the CUIMC Institutional Review Board (IRB#AAAP0401). Informed consent was obtained from all enrolled subjects. A total of 13 tissue specimens were obtained after distal pancreatectomy (N = 6) or a Whipple procedure (N = 7). Patient characteristics are provided in Table 1. Following resection and margin evaluation by surgical pathology, the specimens were transported to the laboratory in sterile saline for 90 minutes of ultrasound scanning, and then returned to pathology for standard evaluation. All tumors were Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDA). The age range of the patients was 58 - 95 years (average age 71.2±9.7 years). The pancreatic specimens used for the experiments had an average size of 13 x 5 x 3 cm3. Specimens were immersed in degassed PBS in a water tank with a layer of sound-absorbing material at the bottom to limit undesired echoes from the tank. Plastic wrap was placed on top of the specimen and pinned to the bottom to keep it from floating to the surface.

Table 1 -.

Patient Characteristics

| Median Age | 71.2 years |

| Range (years) | 58-95 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 54% (7/13) |

| Male | 46% (6/13) |

| Neoadjuvant Therapy | |

| None | 54% (7/13) |

| Some | 46% (6/13) |

| Duration of NAT | 234 days (189-369) |

| Type of surgery | |

| Whipple | 54% (7/13) |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 46% (6/13) |

The specimens were oriented so that the imaging probe was perpendicular to the pancreatic duct to correlate with histology slicing. For each tissue, two HMI scans were performed. Scan #1 probed the maximal 2D cross section of the tumor as detected using palpation and B-mode images acquired with the 2.5-MHz probe. Scan #2 was performed in 3D as a succession of imaging planes along the pancreatic duct from the surgical margin to the opposite end of the pancreas.

The sampling of the human specimens was performed by a dedicated pathology assistant with expertise in pancreatic resection specimens. The histological features of the human pancreatectomy specimens were reviewed by a gastrointestinal pathologist. A pre-planned safety stop was implemented after the first three patients to confirm the procedures did not impact diagnostic utility of the specimens; no evidence of any pathological changes were noted in HMI insonicated samples. Representative tumor sections as well as adjacent non-neoplastic pancreas with or without pancreatitis were selected for Sirius red and trichrome staining.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v8.1.2 software. Pairwise comparisons were assessed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. Multiple comparisons were made using an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test for specific comparisons, as indicated in the figure legends. Summary values are presented as mean±standard deviation. Correlation shown in Figure 1D utilized a one-phase exponential decay; other correlations used linear regression, with R2 values indicating goodness of fit.

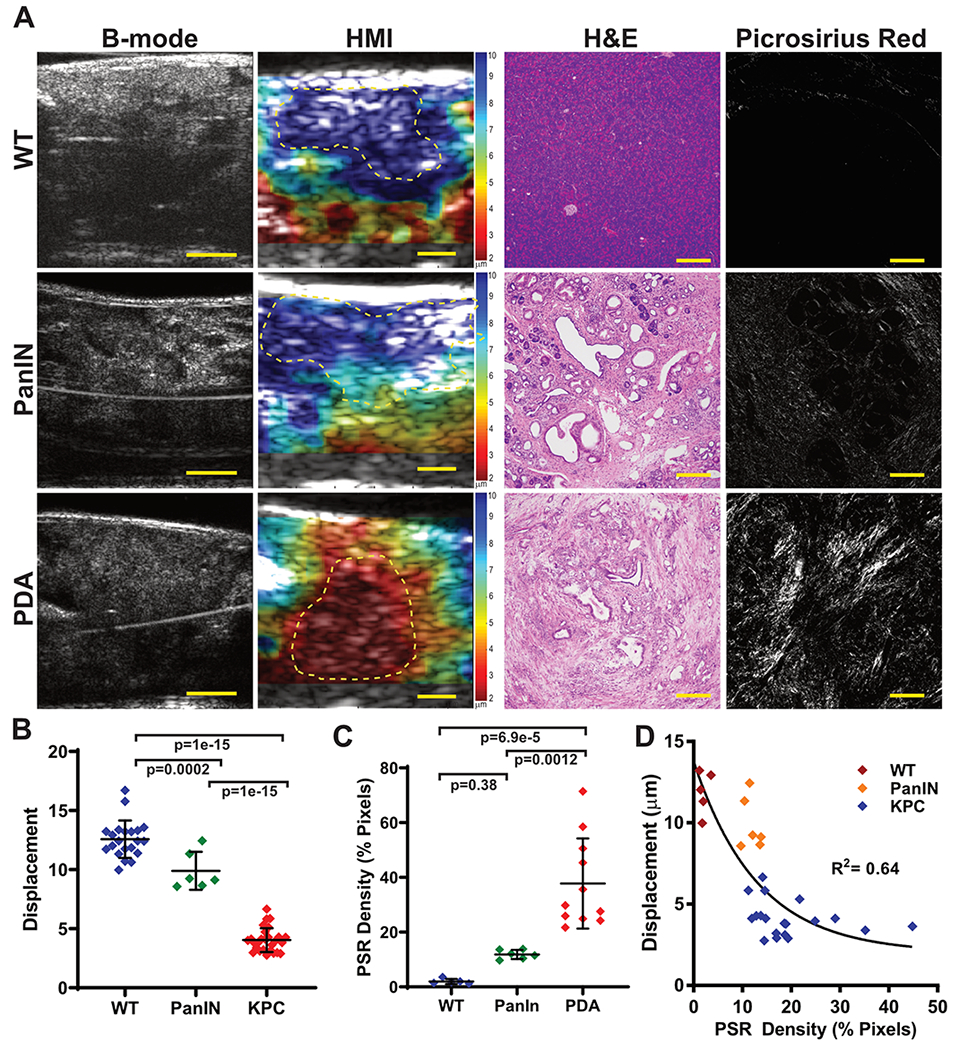

Figure 1. Pancreatic tumors exhibit increased stiffness.

(A) Representative matched images from 35MHz B-mode ultrasound, HMI displacement, H&E stained tissues, and picrosirius red birefringence from a wild type mouse with normal pancreatic tissue (WT), a KPC mouse with preinvasive pancreatic disease (PanIN), and a KPC mouse with adenocarcinoma (PDA). HMI color scales are shown at right of image, indicating peak-to-peak displacement (μm), with blue/green indicating softer tissues and orange/red indicating more stiff tissues. Scalebars for b-mode and HMI images are 2mm; for H&E and picrosirius images are 200μm. (B) Quantification of HMI measurement for wild type mice versus KPC mice with PanINs or PDA. P-values are indicated using a 1-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Quantification of picrosirius red birefringence in pancreatic tissue sections. (D) Displacement as a function of PSR Density for the three groups displaying one-phase exponential decay (black line). Only animals that did not receive additional treatments prior to necropsy are shown.

Results

Stiffness increases during pancreatic tumor development and progression

In order to assess the stiffness of normal, pre-invasive, and malignant pancreatic tissues, we made use of the KPC genetically engineered mouse, a well-validated and clinically-predictive genetically engineered model of PDA (4,22). Using HMI, we measured the displacement of normal pancreas tissue in wild type (WT) mice as well as pancreatic tissues from KPC mice with pre-invasive (PanIN) lesions and frank adenocarcinoma (PDA) (Fig. 1). As in the clinical setting, it can sometimes be challenging to distinguish pancreatic tumors in KPC mice based on B-mode image features alone, particularly at lower frequencies/resolution. However, pancreatic tumors were starkly apparent on HMI displacement maps based on their increased stiffness (lower displacement) relative to surrounding tissues (Fig. 1A). Quantification of mean displacement clearly demonstrated significantly increased stiffness between WT, PanIN, and PDA tissues, with displacements of 12.57±1.58μm, 9.90±1.60μm, and 4.04±1.01μm, respectively (Fig. 1B, p<0.0001 Tukey’s for WT vs. PDA). The severe desmoplastic changes associated with tumor progression were clearly apparent both by routine H&E staining as well as by picrosirius red birefringence, a stain that enables the quantitative measurement of ordered collagen content. Indeed, PDA tissues also exhibited significantly higher collagen content than PanIN tissues (37.78±16.46% vs. 11.86±1.67%, Fig. 1C, p= 0.0012, Tukey’s), and collagen content broadly correlated with tissue stiffness across all samples (Fig. 1D, R2= 0.64, one-phase exponential decay).

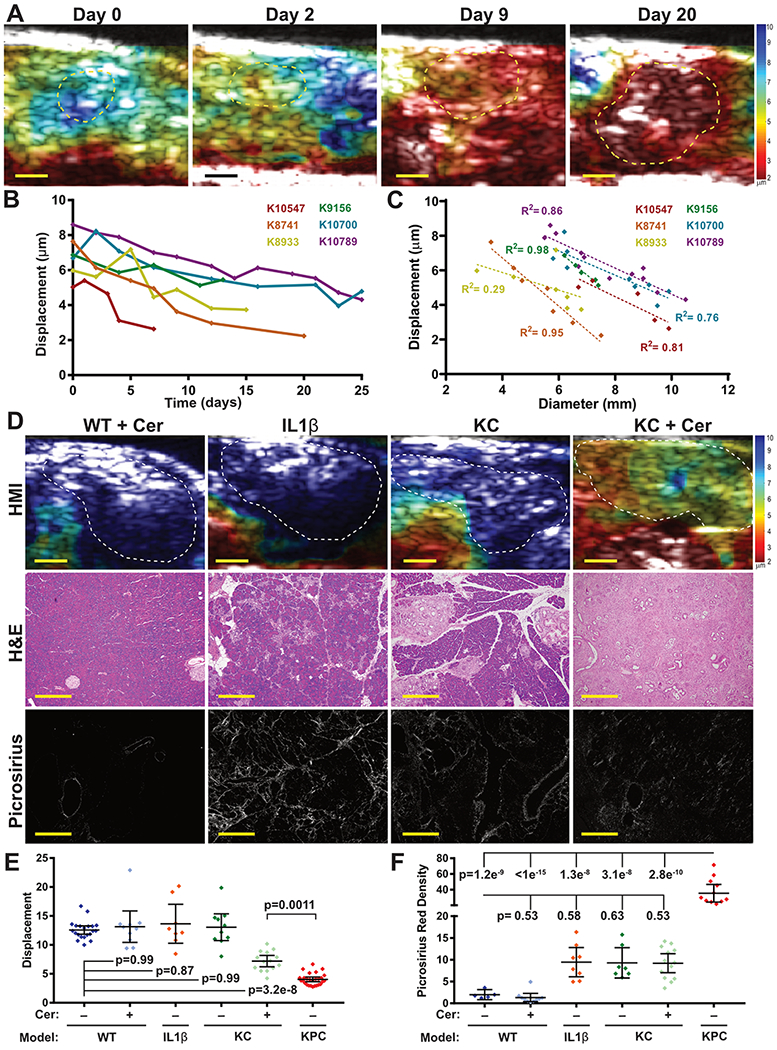

We next sought to understand how tissue stiffness is altered during the transition from premalignancy to adenocarcinoma. We used high resolution (35 MHz) b-mode imaging to identify KPC mice with nascent tumors and then analyzed tissue stiffness of the tumors over time using HMI (Fig. 2A,B). We found that stiffness increased during PDA growth, beginning at an average displacement of 6.8±1.25μm, slightly lower than PanIN samples (p=0.004, unpaired t-test), and decreasing to 3.86±1.24μm at endpoint (p=0.0056 versus initial values, paired t-test). Within each animal, displacement was inversely correlated with tumor size, with an average slope of −0.91μm/mm (Fig. 2C, p= 0.0004 vs 0 slope by one-sample t-test, mean R2= 0.77). We considered the possibility that this observation reflected a general relationship between object size and displacement as measured by HMI, and assessed this by performing HMI on a calibrated phantom with a stiff stepped-cylinder inclusion embedded within a soft matrix (fig. S2). HMI scans performed on the 6.5-mm and 10-mm diameter sections exhibited mean HMI displacements of 3.45±1.25 μm and 3.75±2.41 μm, respectively, disproving a geometry dependence of the HMI technique in measuring stiffness of different sized objects beyond a certain size. Together, these findings indicate that pancreatic tumor stiffness increases during tumor progression.

Figure 2. Pancreatic stiffness increases with disease progression.

(A) Longitudinal HMI displacement maps of a KPC mouse (K8741) showing increased stiffness over the course of 20 days of tumor growth. Bars = 2mm. (B) Quantification of tissue stiffness from six KPC mice demonstrates a consistent decrease in stiffness over time following tumor initiation. (C) The stiffness of each tumor from (B) is strongly inversely correlated with tumor size (mean R2= 0.78). (D) Representative HMI displacement maps, H&E and picrosirius images of pancreatic tissues from four models of pancreatitis: wild-type mice treated with cerulein (WT+cer), Elastase-interlukin 1β transgenic mice (IL1β), KrasLSL.G12D/+; Pdx1-Cretg/+ (KC) mice, and KC mice treated with cerulein (KC+Cer). Bars = 2mm for HMI maps, 200μm for H&E, and 40μm for picrosirius images. (E) Stiffness was significantly increased in the pancreata of KC mice treated with cerulean, but all pancreatitis models were significantly less stiff than KPC pancreatic tumors. Selected statistical comparisons shown using a 1-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test between all groups. (F) Quantification of picrosirius red staining found increased collagen deposition in KPC tumors versus all other groups (1-way ANOVA + Tukey’s between all groups). IL1β, KC, and KC+cer mice had modestly elevated collagen deposition, but this was not statistically significant after multiple hypothesis correction.

HMI stiffness distinguishes pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer

To evaluate the utility of HMI for distinguishing pancreatitis from PDA, we assessed several pancreatic stiffness in four mouse models of pancreatitis: WT mice treated with cerulean (mild acute pancreatitis), Ela-IL1b transgenic mice (mild chronic pancreatitis), KC mice (moderate chronic pancreatitis), and KC mice treated with cerulean (severe chronic pancreatitis) (Fig. 2D,E, see Methods for additional details). Pancreatic tissue displacements measured in most of these disease models were not significantly different than that of normal pancreas tissue (12.57±1.58μm for WT versus 13.14±3.80 for WT+cer, 13.64±4.03 for Ela-IL-1β, and 13.05±3.23 for KC, all comparisons not significant). However, cerulein–treated KC mice with severe chronic pancreatitis had significantly increased pancreatic stiffness (7.20±1.69μm) compared to WT pancreas tissue (p=3.2x10−8, Tukey’s). Of note, this change was not accompanied by an increase in picrosirius red staining, perhaps indicating a difference in the structure of collagen in the ECM of pancreatitis in this model compared to PDA (Fig. 2F). Consistent with this, the mean HMI displacement of KPC pancreatic tumors (4.04±1.01μm) was significantly lower than chronic pancreatitis in the cerulein–treated KC mice (p= 0.0011, Tukey’s). These results further support the potential for HMI to distinguish PDA from non-malignant pathologies.

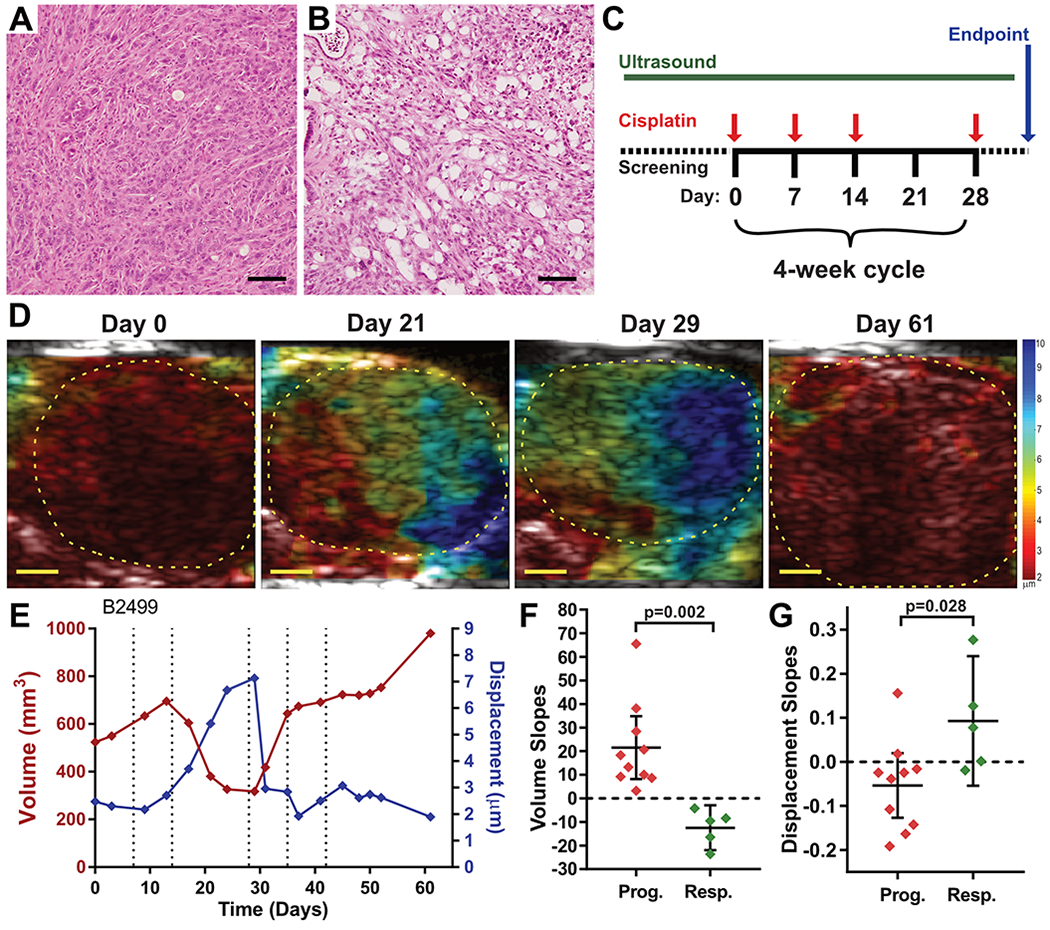

HMI detects changes in stiffness in response to therapeutic intervention

To assess the ability of HMI to detect therapy-induced changes in tissue stiffness, we made use of a BRCA2–deficient model of PDA. Our group has found that most KrasLSL.G12D/+; p53LSL.R270H/+; PdxCretg/+; brca2F/F (KPCB2F/F) tumors are sensitive to treatment with the DNA cross-linking agent cisplatin, inducing residual acellular lacunae following the apoptotic loss of tumor cells (Fig. 3A,B, manuscript in preparation). This model provides the opportunity to study successful chemotherapeutic responses in a disease that is otherwise highly chemoresistant. Using high resolution conventional ultrasound, we identified KPCB2F/F mice with nascent tumors and monitored both tumor size and stiffness longitudinally by HMI during treatment with cisplatin (Fig. 3C). A tumor from a KPCB2F/F mouse treated with vehicle exhibited increased tumor stiffness over time, similar to our observations in the KPC model (fig. S3A). By contrast, seven KPCB2F/F mice treated with cisplatin all survived at least twice as long as the vehicle-treated animal. Analysis of tumor volumes showed evidence of disease stabilizations or frank regressions in cisplatin-treated tumors and these were generally accompanied by increased displacement as measured by HMI (Fig. 3D,E; fig. S3B–H). To quantitatively assess this relationship, we segmented the growth curves of each cisplatin–treated KPCB2F/F tumors into groups characterized as “progressing” or “responding” (fig. S3). Notably, the change in HMI displacement of responding segments (0.093±0.119) was significantly higher than progressing segments (−0.054±0.103) (Fig. 3F,G; p=0.028, unpaired t-test), potentially indicating that successful response to chemotherapy is associated with reduced tumor stiffness. These data suggest that HMI may prove useful as an early indicator of response to treatment in pancreatic cancer patients, particularly in the metastatic setting where liver or other distal metastases may be accessible by non-invasive, extracorporeal ultrasound.

Figure 3. Pancreatic tumor stiffness is altered by therapeutic intervention.

(A,B) H&E histopathology images from two KPCB2F/F pancreatic tumors treated either with saline (A) or with cisplatin. Bars = 200μm. (C) Experimental design for therapeutic study of KPCB2F/F mice. Tumor bearing mice were identified by high resolution ultrasound and then treated with 3mg/kg cisplatin, i.v., once weekly for three weeks, followed by a one-week rest cycle. This four-week cycle was repeated with longitudinal HMI until mice met endpoint criteria. (D) HMI displacement maps for a KPCB2F/F mouse treated with cisplatin (B2499) over time. Bars = 2mm. (E) Longitudinal tumor volume and HMI displacement measurements of Mouse B2499. Red curve indicates tumor volume, blue curve indicates tumor HMI displacement. Dotted lines indicate dates of cisplatin treatment. (F,G) Quantification of tumor growth slopes and displacement slopes, respectively, for progressing and responding curve segments as delineated in fig. S3, compared using Student’s T-test.

Clinical evaluation of HMI in freshly resected pancreatic cancer specimens

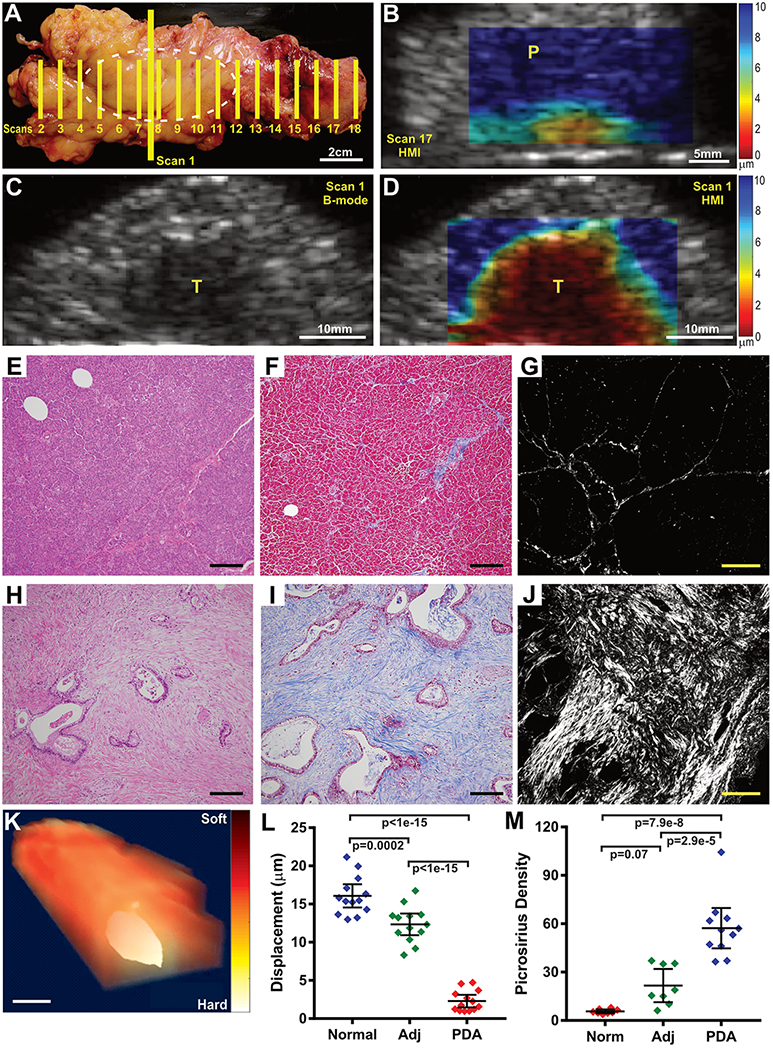

In light of the promising preclinical results using HMI on mouse models of PDA, we established a clinical protocol to perform HMI on intact, freshly resected pancreatic specimens from PDA patients (see Table 1 for patient characteristics). For each case, multiple B-mode and HMI images were acquired at successive steps through the specimen in an orientation consistent with standard pathology procedures such that a rough co-registration of imaging and histopathology could be performed (Fig. 4A,B). Notably, in 7 of 13 cases, the anatomical border of tumor within the overall pancreas specimen was difficult or impossible to delineate by 2.5 MHz B-mode ultrasound, even under these ideal ex vivo conditions (Fig. 4C). By comparison, we found that tumor tissues were starkly apparent by HMI (Fig. 4D). To quantify this distinction, we selected HMI scans either from within the malignant mass, proximal to the tumor, or at a distance from the tumor, roughly aligning with regions of PDA, adjacent inflamed tissues, or mostly normal tissues, as determined by histopathological assessment of associated tissue blocks. Notably, HMI displacement in regions of adenocarcinoma was nearly 7-fold lower than in normal pancreas (Fig. 4B, 2.30±1.36μm vs. 16.07±2.51μm, respectively, p<1x10−15, Tukey’s), substantially larger than the ~3-fold difference observed in mice (Fig. 1). In addition, we also observed lower displacement within the tumor compared to adjacent pancreatitis (12.34±2.34μm, p<1x10−15, Tukey’s). Interestingly, clear delineation of tumor margins was apparent by HMI despite histopathological evidence of extensive pancreatitis in the regions directly adjacent to tumors (Fig. 4E–K). The ability of HMI to distinguish tumors from adjacent, inflamed pancreatic tissues supports its potential utilization for the differential diagnosis of pancreatitis versus PDA.

Figure 4. Elevated tissue stiffness in human PDA.

(A) Photograph of a distal pancreatectomy specimen. Hashed white oval indicates position of a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Yellow lines indicate imaging planes. (B) HMI displacement map from Scan 17 in (A) showing that the mostly normal pancreas tissue (labelled P) distal to the tumor is soft (blue color). (C,D) B-mode (C) and HMI displacement images (D) from Scan 1 in (A), depicting the main mass of the pancreatic tumor (labelled T). Notably, the borders of the tumor in the B-mode image are indistinct. By comparison, the HMI maps clearly distinguishes the extent of disease. (E-J) Microscopic images of the sample from (A) showing normal pancreas uninvolved with tumor (E-G) compared to the center of the adenocarcinoma mass (H-J). Tissue sections are stained with H&E (E,H, bars = 200μm), Mason’s Trichrome (F,I, bars = 200μm), or picrosirius red (G,J, bars = 40μm). PDA images show evidence of the extensive extracellular matrix deposition that is characteristic of pathology of pancreatic cancer and contribute to increased stiffness. (K) A 3D rendering of the resection specimen from (A) using HMI results from Scans 2-17, clearly indicates the location of the tumor. Bar = 25mm (L) Quantification of tissue displacement for 13 human PDA specimens (PDA) compared to adjacent inflamed pancreas (Adj) or largely normal pancreas tissue (Norm), when present. Pancreatic tumor tissue was significantly more stiff than inflamed or normal pancreatic tissue (1-way ANOVA + Tukey’s). (M) Quantification of picrosirius red staining on samples from 12 PDA specimens showing increased collagen deposition in PDA versus adjacent inflamed or normal pancreatic tissue (1-way ANOVA + Tukey’s).

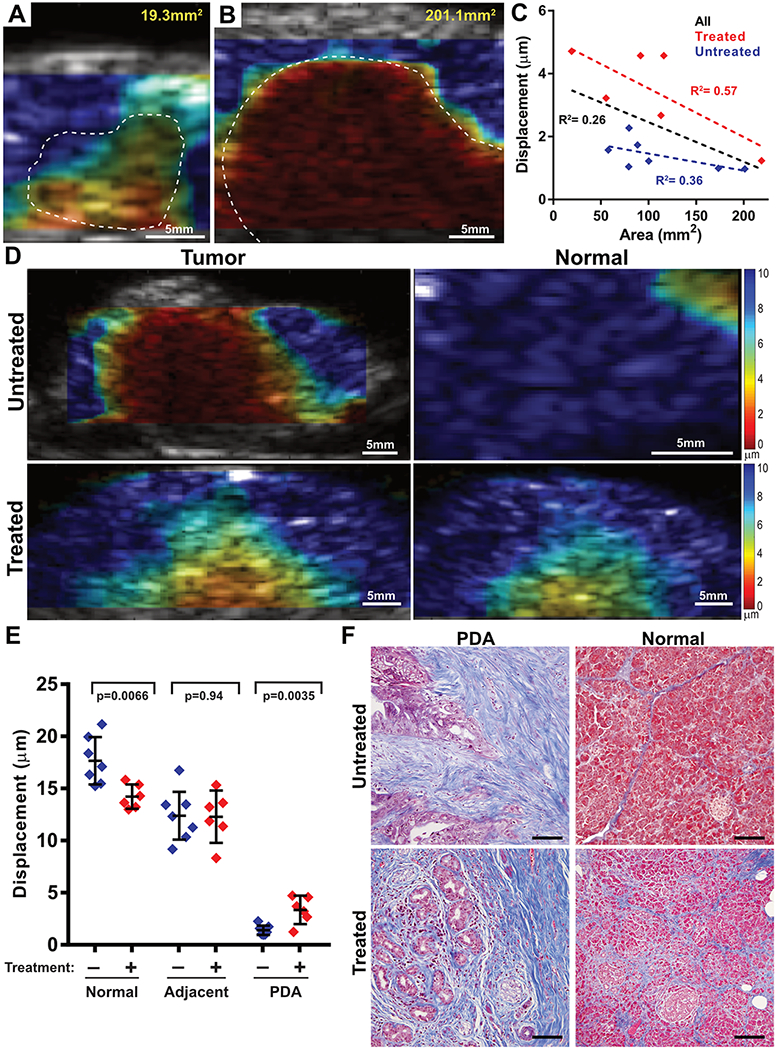

We next examined the relationship between tumor size and stiffness. We found that, consistent with our preclinical data, larger pancreatic tumors generally had a lower displacement than smaller tumors (Fig. 5A–C), (slope= −0.013μm/mm2, R² = 0.26, p=0.08) indicating a borderline association between tumor stiffness and progression. Furthermore, in the course of examining the tumor size/stiffness data, we noted a potential impact of neoadjuvant treatment status on tissue stiffness (Fig. 5C). A formal assessment of the impact of chemotherapy on tissue stiffness would require longitudinal imaging of patients as they were treated with chemotherapy. While this was not possible under the current ex vivo protocol (performed at endpoint on resection specimens), we made use of the fact that a subset of the patients in this study received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy (Table S1), including gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (GA), gemcitabine/docetaxel/capecitabine (GTX), or 5-fluorouracil/irinotecan/leukovorin/oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX), alone or in combination with stereotactic or intensity modulated radiotherapy (SBRT or IMRT). Neoadjuvant therapy is used to induce acute regression in order to downstage tumors to a sufficient degree to enable resection, with treatment generally continuing until several weeks before surgery. Among the 13 patients in our cohort, 6 underwent some form of neoadjuvant therapy prior to resection and therefore may be considered to have responded sufficiently to enable surgery. We therefore assessed the relationship between tissue stiffness and treatment status. Consistent with our preclinical results, neo-adjuvant treated human pancreatic tumors exhibited a significantly lower stiffness than untreated tumors (displacement = 3.35±1.30μm versus 1.40±0.48μm, respectively, Fig. 5D,E, p= 0.0035, unpaired t-test). Although these differences may reflect pre-existing distinctions between the population of patients who are candidates for immediate resection vs. those who required neoadjuvant therapy in order to achieve resection, the two groups had similar tumor grades and there was no statistical difference in the number of positive evaluated lymph nodes between the groups (p= 0.75, Fisher’s exact). These data may therefore reflect the ability of HMI to detect reduced tissue stiffness in response to neoadjuvant therapy–induced tumor responses. On the other hand, we noted that normal pancreatic parenchyma from neoadjuvant-treated patients exhibited increased stiffness compared to untreated patients (displacement = 17.66±2.26μm versus 14.22± 1.16μm, respectively (Fig. 5E, p=0.0066, Student’s t), perhaps due to chemotherapy/radiation–induced fibrosis in the normal pancreas (Fig. 5F). Together, our findings support the potential use of HMI as a candidate modality to both clarify differential diagnoses and monitor early responses to therapy.

Figure 5. Stiffness of human PDA varies with tumor size and treatment.

(A,B) HMI displacement maps from a small (B) and a large (C) pancreatic tumor showing increased stiffness in the larger tumor. (C) Quantification of 13 PDA resection cases found that tumor size (based on 2D area) was inversely correlated with HMI displacement (by linear regression). Red dots indicate tumors with no prior therapy (R2= 0.36); blue dots indicate tumors that received neoadjuvant therapy (R2= 0.57). Black line indicates regression of all samples (R2= 0.26). (D) HMI displacement maps in tumor (left) and normal pancreatic parenchyma (right) from a human specimen with no prior therapy (top) and a tumor that received 3 months of gemcitabine + Abraxane and intensity modulated radiation therapy. (E) Comparison of HMI displacement between untreated and treated specimens, examining PDA, adjacent inflamed pancreas, and distal normal pancreas. The stiffness of PDA decreased after treatment while the stiffness of normal tissue increased (Student’s T-test for each pairwise comparison). (F) Microscopy images of the specimens from (D) showing both tumor and normal pancreatic tissues stained with H&E or Mason’s trichrome. Bars = 200μm.

Discussion

Pancreatic surgeons often describe PDA as feeling hard or even “rock-like”. Such anecdotal accounts inspired our effort to derive a clinically useful means to measure and quantify tissue stiffness in pancreatic cancer. In PDA, this gross mechanical property arises from the combined effects of several biological features of the epithelial and stromal compartments. K-ras and other oncogenic driver proteins induce cytoskeletal changes in malignant epithelial cells via downstream effectors such as PI3K and Rac (28). K-ras also induces a host of paracrine signals that control the cellular composition of the tumor stroma, promoting the activation stromal cells that deposit and remodel the ECM (29). Stromal cells secrete polymeric proteins such as collagen; carbohydrate polymers such as glycosaminoglycans and heparin sulfate; proteoglycans; and matrix remodeling enzymes that confer high mechanical stiffness as well as high interstitial fluid pressure, via trapping of water into a hydrogel (30). The net effect is an environment with such high pressure and stiffness that many smaller blood vessels are collapsed, leading to poor perfusion and compromised drug delivery (4). Using HMI, we were able to detect increased stiffness in pancreatic tumor samples in both mice and humans; indeed, in human resection samples, the demarcation between tumor and adjacent tissue by HMI was particularly apparent, far exceeding the contrast from standard anatomical ultrasound, even when B-mode imaging was unable to delineate the tumor. The strong performance of HMI in this side-by-side comparison both supports the utilization of HMI to aid in differential diagnoses, and also raises the possibility that HMI could help guide the placement of biopsy needles during routine EUS-guided biopsy procedures.

A key finding was that HMI was capable of distinguishing PDA from pancreatitis across a range of murine models, as well as in human pancreatic resection samples (relative to adjacent inflamed tissues). Pancreatitis denotes a diverse range of inflammatory pathologies of the pancreas, including both acute and chronic manifestations, arising from a variety of genetic, autoimmune, chemical, and environmental insults. Pancreatic inflammation from both malignant and non-malignant etiologies can produce similar features on standard imaging, we establish here that the former results in a higher range of stiffness values by HMI than pancreatitis samples in both mice and humans, serving as a potential basis for quantitative distinction of these states. This concept has also been explored using magnetic resonance elastography (31) and other technologies (32,33), though subject to the technical limitations and ease of quantification noted earlier. The mechanistic basis for this distinction is not completely clear, but may be related to the organization of ECM components such as collagen that can develop during the process of malignancy (34) and is negatively associated with pancreatic cancer patient outcome (35). This concept is supported by our observation that stiffness continues increase over time in murine pancreatic tumors, implying an ongoing process of stromal maturation that is reflected in the mechanical properties of tumors.

One of the major clinical challenges of treating metastatic pancreatic cancer patients is that there is typically only time to attempt one or two therapeutic interventions before the patient’s condition deteriorates. This can be further exacerbated by the extended time between when a patient is first treated and when a clinical response, or progression, may be detected by anatomical imaging. A non-invasive means of detecting the response of tumors early in a treatment course could provide an invaluable opportunity to assess additional regimens. The biomechanical properties of cancerous tissues can be altered in response to chemotherapy, by directly altering the viscoelastic properties of tumor cells (36), through indirect effects on the tumor microenvironment (37), or through tissue decompression following the apoptotic loss of cells. For example, ultrasound elastography was previously utilized to detect decreased stiffness in response to gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel treatment in human PDA patients, an effect that was associated with disorganization of collagen structure and loss of stromal fibroblasts (38). A similar effect was noted using shear wave elastography in rectal cancer patients treated with high dose chemoradiotherapy (39) and in breast cancer patients following neoadjuvant therapy (40,41). Consistent with these findings, we found that HMI can detect changes in tissue stiffness over the course of just a few days in a chemosensitive genetically engineered mouse model, following treatment with cisplatin. These changes were associated with an apoptotic response that led to a loss of cellular content that we infer decompressed the tissue, though effects on cell stiffness and ECM content could also play a role. Critically, our findings were supported by clinical observations that pancreatic tumors from PDA patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy had a lower mean stiffness than treatment–naïve tumors (Fig. 5E).

To be clear, this clinical comparison is confounded by the fact that these two groups draw from different patient populations. However, patients who require neoadjuvant therapy, by definition, have progressed further than those who can proceed directly to resection, and therefore their tumors would be expected to larger and stiffer. That their tumors were in fact less stiff is consistent with the interpretation that neoadjuvant therapy caused softening of the tumor. Nonetheless, a definitive determination on HMI potential for neoadjuvant response evaluation will require longitudinal studies in patients, either through extracorporeal assessment of metastatic lesions or using an HMI–equipped endoscope. Such longitudinal studies will also be critical to establish whether quantifiable changes in tissues stiffness actually precede changes in tumor size or growth rate, establishing the basis for an early biomarker of therapeutic response.

To our knowledge, an association between neoadjuvant therapy and tissue stiffness in normal pancreatic tissues has not been previously reported. Though preliminary, this finding highlights a key advantage of HMI over other clinically-available forms of elastography that rely on contrast to surrounding pancreas tissues to facilitate tumor monitoring. The opposing effects of neoadjuvant therapy on tumor versus normal pancreas tissue serves to diminish the inherent contrast of PDA versus surrounding tissues, potentially masking the presence of residual disease in treated patients. The ability of HMI to provide a quantitative displacement measurement for tumor tissues without relying on adjacent control tissues provides a more direct path for clinical implementation.

In summary, we envision several clinical applications for HMI in the setting of pancreatic cancer. With the incorporation of HMI into a GI endoscope, HMI may be deployed as a key component of routine diagnostic scans of the pancreas, providing critical, complementary information to B-mode ultrasound for challenging cases. With the same instrument, HMI may also prove useful for guiding biopsy needle placement and longitudinal monitoring of disease progression. Finally, for patients with metastatic cancer, many liver and other lesions will be accessible by transabdominal HMI, enabling routine imaging and quantification of early response to therapeutic intervention. Thus, this work provides an essential translational foundation for diverse applications of HMI in PDA patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

KPO received support for this work from the Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research. The National Institutes of Health provided support in part to EEK (R01 CA228275) and PEO (KL2 TR000081). The authors wish to thank Timothy Wang for donating the Elastase-IL-1β transgenic mice. This work was supported by the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center CCSG grant (NIH/NCI P30 CA13696), in particular the Molecular Pathology Shared Resource, the Oncology Precision Therapeutics and Imaging Shared Resource, and the Database Shared Resource. Finally, we thank Hanina Hibshoosh for advice and guidance.

Financial support:

KPO received support for this project from the Lustgarten Foundation for Cancer Research.

EEK received support from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA228275).

PEO received support from the National Institutes of Health (KL2 TR000081).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69(1):7–34 doi 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012;21(3):418–29 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauhan VP, Boucher Y, Ferrone CR, Roberge S, Martin JD, Stylianopoulos T, et al. Compression of pancreatic tumor blood vessels by hyaluronan is caused by solid stress and not interstitial fluid pressure. Cancer Cell 2014;26(1):14–5 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 2009;324(5933):1457–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberstein PE, Olive KP. Pancreatic cancer: why is it so hard to treat? Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology 2013;6(4):321–37 doi 10.1177/1756283X13478680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen J, Schlorer E, Greiner L. EUS elastography of the pancreas: feasibility and pattern description of the normal pancreas, chronic pancreatitis, and focal pancreatic lesions. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 2007;65(7):971–8 doi 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ophir J, Alam SK, Garra BS, Kallel F, Konofagou EE, Krouskop T, et al. Elastography: Imaging the elastic properties of soft tissues with ultrasound. J Med Ultrason (2001) 2002;29(4):155 doi 10.1007/BF02480847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, et al. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol 2003;29(12):1705–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi X, Martin RW, Rouseff D, Vaezy S, Crum LA. Detection of high-intensity focused ultrasound liver lesions using dynamic elastometry. Ultrason Imaging 1999;21(2):107–26 doi 10.1177/016173469902100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y, Glaser KJ, Venkatesh SK, Ben-Abraham EI, Ehman RL. Feasibility of using 3D MR elastography to determine pancreatic stiffness in healthy volunteers. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41(2):369–75 doi 10.1002/jmri.24572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fatemi M, Greenleaf JF. Ultrasound-stimulated vibro-acoustic spectrography. Science 1998;280(5360):82–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bercoff J, Tanter M, Fink M. Supersonic shear imaging: a new technique for soft tissue elasticity mapping. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control 2004;51(4):396–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nightingale KR, Palmeri ML, Nightingale RW, Trahey GE. On the feasibility of remote palpation using acoustic radiation force. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2001;110(1):625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maleke C, Konofagou EE. Harmonic motion imaging for focused ultrasound (HMIFU): a fully integrated technique for sonication and monitoring of thermal ablation in tissues. Physics in medicine and biology 2008;53(6):1773–93 doi 10.1088/0031-9155/53/6/018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vappou J, Hou GY, Marquet F, Shahmirzadi D, Grondin J, Konofagou EE. Non-contact, ultrasound-based indentation method for measuring elastic properties of biological tissues using harmonic motion imaging (HMI). Physics in medicine and biology 2015;60(7):2853–68 doi 10.1088/0031-9155/60/7/2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payen T, Palermo CF, Sastra SA, Chen H, Han Y, Olive KP, et al. Elasticity mapping of murine abdominal organs in vivo using harmonic motion imaging (HMI). Physics in medicine and biology 2016;61(15):5741–54 doi 10.1088/0031-9155/61/15/5741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han Y, Wang S, Hibshoosh H, Taback B, Konofagou E. Tumor characterization and treatment monitoring of postsurgical human breast specimens using harmonic motion imaging (HMI). Breast Cancer Res 2016;18(1):46 doi 10.1186/s13058-016-0707-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prat F, Lafon C, De Lima DM, Theilliere Y, Fritsch J, Pelletier G, et al. Endoscopic treatment of cholangiocarcinoma and carcinoma of the duodenal papilla by intraductal high-intensity US: Results of a pilot study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 2002;56(6):909–15 doi 10.1067/mge.2002.129872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou GY, Marquet F, Wang S, Konofagou EE. Multi-parametric monitoring and assessment of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) boiling by harmonic motion imaging for focused ultrasound (HMIFU): an ex vivo feasibility study. Physics in medicine and biology 2014;59(5):1121–45 doi 10.1088/0031-9155/59/5/1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou GY, Provost J, Grondin J, Wang S, Marquet F, Bunting E, et al. Sparse matrix beamforming and image reconstruction for 2-D HIFU monitoring using harmonic motion imaging for focused ultrasound (HMIFU) with in vitro validation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2014;33(11):2107–17 doi 10.1109/TMI.2014.2332184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo J, Konofagou EE. Key parameters for precise lateral displacement estimation in ultrasound elastography. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2009;2009:4407–10 doi 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 2003;4(6):437–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sastra SA, Olive KP. Quantification of murine pancreatic tumors by high-resolution ultrasound. Methods Mol Biol 2013;980:249–66 doi 10.1007/978-1-62703-287-2_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skoulidis F, Cassidy LD, Pisupati V, Jonasson JG, Bjarnason H, Eyfjord JE, et al. Germline Brca2 heterozygosity promotes Kras(G12D) -driven carcinogenesis in a murine model of familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2010;18(5):499–509 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrache F, Tu SP, Bhagat G, Pendyala S, Osterreicher CH, Gordon S, et al. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta in the murine pancreas results in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2008;135(4):1277–87 doi 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carriere C, Young AL, Gunn JR, Longnecker DS, Korc M. Acute pancreatitis markedly accelerates pancreatic cancer progression in mice expressing oncogenic Kras. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;382(3):561–5 doi 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ardito CM, Gruner BM, Takeuchi KK, Lubeseder-Martellato C, Teichmann N, Mazur PK, et al. EGF Receptor Is Required for KRAS-Induced Pancreatic Tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2012;22(3):304–17 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez-Viciana P, Warne PH, Khwaja A, Marte BM, Pappin D, Das P, et al. Role of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase in cell transformation and control of the actin cytoskeleton by Ras. Cell 1997;89(3):457–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ying H, Kimmelman AC, Lyssiotis CA, Hua S, Chu GC, Fletcher-Sananikone E, et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell 2012;149(3):656–70 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuFort CC, DelGiorno KE, Carlson MA, Osgood RJ, Zhao C, Huang Z, et al. Interstitial Pressure in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Is Dominated by a Gel-Fluid Phase. Biophys J 2016;110(9):2106–19 doi 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi Y, Cang L, Zhang X, Cai X, Wang X, Ji R, et al. The use of magnetic resonance elastography in differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A preliminary study. Eur J Radiol 2018;108:13–20 doi 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iglesias-Garcia J, Lindkvist B, Larino-Noia J, Abdulkader-Nallib I, Dominguez-Munoz JE. Differential diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses: contrast-enhanced harmonic (CEH-EUS), quantitative-elastography (QE-EUS), or both? United European Gastroenterol J 2017;5(2):236–46 doi 10.1177/2050640616640635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goertz RS, Schuderer J, Strobel D, Pfeifer L, Neurath MF, Wildner D. Acoustic radiation force impulse shear wave elastography (ARFI) of acute and chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic tumor. Eur J Radiol 2016;85(12):2211–6 doi 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 2009;139(5):891–906 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drifka CR, Loeffler AG, Mathewson K, Keikhosravi A, Eickhoff JC, Liu Y, et al. Highly aligned stromal collagen is a negative prognostic factor following pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma resection. Oncotarget 2016;7(46):76197–213 doi 10.18632/oncotarget.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M, Liu L, Xiao X, Xi N, Wang Y. Effects of methotrexate on the viscoelastic properties of single cells probed by atomic force microscopy. J Biol Phys 2016;42(4):551–69 doi 10.1007/s10867-016-9423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahbari NN, Kedrin D, Incio J, Liu H, Ho WW, Nia HT, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy induces ECM remodeling and mechanical barriers to therapy in colorectal cancer liver metastases. Sci Transl Med 2016;8(360):360ra135 doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alvarez R, Musteanu M, Garcia-Garcia E, Lopez-Casas PP, Megias D, Guerra C, et al. Stromal disrupting effects of nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2013;109(4):926–33 doi 10.1038/bjc.2013.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rafaelsen SR, Vagn-Hansen C, Sorensen T, Lindebjerg J, Ploen J, Jakobsen A. Ultrasound elastography in patients with rectal cancer treated with chemoradiation. Eur J Radiol 2013;82(6):913–7 doi 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falou O, Sadeghi-Naini A, Prematilake S, Sofroni E, Papanicolau N, Iradji S, et al. Evaluation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in women with locally advanced breast cancer using ultrasound elastography. Transl Oncol 2013;6(1):17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jing H, Cheng W, Li ZY, Ying L, Wang QC, Wu T, et al. Early Evaluation of Relative Changes in Tumor Stiffness by Shear Wave Elastography Predicts the Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients With Breast Cancer. J Ultrasound Med 2016;35(8):1619–27 doi 10.7863/ultra.15.08052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.