Abstract

Introduction

The objective of this study was to compare the risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation (AF) with adherent use of oral anticoagulation (OAC), non-adherent use, and non-use of OAC.

Methods

Using 2013-2016 Medicare claims data, we identified patients newly diagnosed with AF in 2014-2015 and collected prescriptions filled for OAC in the 12 months after AF diagnosis (n=39,272). We categorized participants each day into 3 time-dependent exposures: adherent use (≥80% of the previous 30 days covered with OAC), non-adherent use (0%-80% covered with OAC), and non-use (0%). We constructed Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the association between time-dependent exposures and time to stroke, adjusting for demographics and clinical characteristics.

Results

The sample included 39,272 patients. Study participants spent 35.0% of the follow-up period in the adherent use exposure category, 10.9% in the non-adherent category, and 54.0% in the non-use category. OAC adherent use (HR 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52-0.74) and non-adherent use (HR 0.74; 95% CI 0.57-0.95) were associated with lower hazards of stroke than non-use. Adherent use to DOAC (HR 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42-0.69) and warfarin (0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.86) was associated with lower risk of stroke than non-use, but the risk of stroke did not statistically differ between DOAC and warfarin adherent use (HR 0.77; 95% CI, 0.56-1.04).

Discussion

Although adherence to OAC reduces stroke risk by nearly 40%, newly diagnosed AF patients in Medicare adhere to OAC on average only one third of the first year after AF diagnosis.

1. INTRODUCTION

The most common cardiac arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with a 5-fold increase in the risk of stroke.1 Although oral anticoagulation (OAC) is recommended for stroke prevention in patients with AF with CHA2DS2-VASc score≥2,2 only 50%-60% of US patients in this group are actually treated with oral anticoagulants, and less than half of them adhere to this therapy over time.3-6 Before 2010, the numerous limitations associated with warfarin therapy were regarded as the main reason behind OAC underuse;3,7,8 however, the approval of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) has only resulted in modest imporvements in OAC use and adherence.9-13

The underuse and suboptimal adherence to OAC in AF is concerning because continuous, adherent use of oral anticoagulants is crucial for stroke prevention: the risk of stroke increases by 7% per 10% decline in the proportion of days covered (PDC) with OAC, and gaps in OAC therapy of 1-3 months have been shown to double the risk of stroke in high-risk patients.14,15 However, these previous studies evaluating the association between OAC adherence and risk of stroke focused on OAC users, excluding patients with AF who never initiated OAC therapy. 14,15 As a result, it remains unknown how the risk of stroke compares for patients with continuously adherent to OAC, versus non-adherent OAC users, versus non-users. Additionally, it is unclear whether the reduction in the risk of stroke associated with continuous adherence to OAC is similar for warfarin and DOACs.

We used Medicare claims data for patients newly diagnosed with AF to estimate the reduction in the risk of stroke associated with adherent and non-adherent use of OAC, as opposed to non-use. We further estimated the reduction in stroke risk associated with adherence to DOACs and to warfarin. We focused on Medicare because the prevalence of AF increases with age,16 and because a DOAC adherence measure is likely to become part of star ratings calculations.17

2. METHODS

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

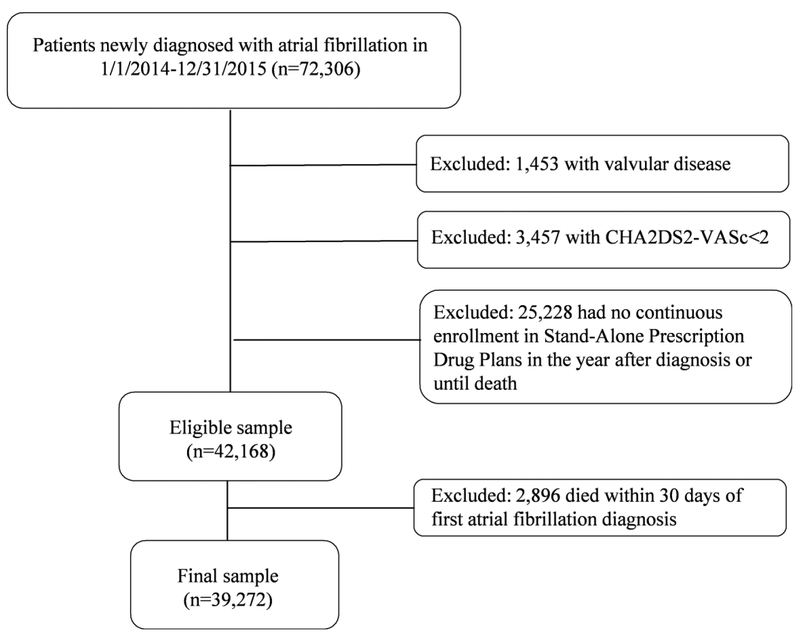

We obtained 2014-2016 medical and pharmacy claims from a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and identified patients who were diagnosed with AF for the first time between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2015 (Figure 1). AF was defined using the CMS Chronic Condition Warehouse indicator, which defines AF as having one inpatient claim or two outpatient claims with ICD-9 diagnosis code 427.31,18 and traces the first AF diagnosis back to January 1999. We defined index date as 30 days after first AF diagnosis. We excluded patients with a diagnosis of valvular disease (list of diagnosis codes in Supplemental Table), those with CHA2DS2-VASc score<2, those who had no continuous enrollment in Stand-Alone Prescription Drug Plans, or who died within 30 days of diagnosis. The final sample included 39,272 patients, who were followed starting 30 days after first AF diagnosis (index date) for 330 days or until death. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh as exempt because de-identified data were used in analysis.

Figure 1. Overview of the Cohort Selection.

Using claims data from a 5% random sample of Medicare part D beneficiaries, we selected patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation in 2014-2015. After excluding those with a history of valvular disease, with CHA2DS2-VASc<2, who had no continuous enrollment in Stand-Alone Prescription Drug plans, or who died within 30 days of first atrial fibrillation diagnosis, the final sample included 39,272 patients.

2.2. Outcomes

The primary outcome was incidence of ischemic stroke, defined as having an inpatient claim with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes 434.xx, 436.xx, 444.xx or ICD-10 I63, I66, I74. 19 This definition has a positive predictive value of 91% and a specificity of 99.8%.19

2.3. Exposure

To define exposure categories, we extracted all prescriptions for oral anticoagulants, including warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban after the first AF diagnosis and arrayed them chronologically. Using the date of fill and the days of supply, we created a supply diary for each patient,20 which indicated possession of any oral anticoagulant, of warfarin and of DOAC every day of the study period. We assumed that patients took their medications as prescribed, starting on the day of prescription filling, and that each prescription provided coverage with oral anticoagulation for as many days as indicated in the days of supply field.. Then, we categorized patients into 3 time-dependent exposure categories every day of follow-up adherent use, defined as ≥80% of the previous 30 days covered with OAC;21 non-adherent use, >0% but <80% of the previous 30 days covered with OAC; and non-use, 0% of the previous 30 days covered with OAC. In sensitivity analyses, we categorized patients in a similar manner, but using 90% of days covered with OAC as cut-off for categorization.21 We defined the exposure on the basis of 30-day periods analyses because in our data, we are not able to ascertain when patients stopped taking medications, but only when they ran out of fills. By measuring oral anticoagulation use on the basis of 30-day intervals, it was more likely that we correctly ascertained patients who discontinued oral anticoagulation as non-adherent users or non-users than if we had used shorter time intervals.22,23

In secondary analyses, we further subdivided the adherent use category into DOAC adherent use, defined as ≥80% of the previous 30 days covered with DOAC, warfarin adherent use, defined as ≥80% of the previous 30 days covered with warfarin, and combined dual DOAC and warfarin use, defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with OAC, but less than 80% of them covered with DOACs and less than 80% covered with warfarin. We also performed sensitivity analyses using 90% as cut-off.21

2.4. Covariates

Covariates included demographics, social determinants, and clinical characteristics, and were defined on the day of first AF diagnosis. Demographics included age, gender, and race. Social determinants included eligibility for Medicaid coverage, for low income subsidy, and residence in a rural area. Rural residence was defined employing the CMS zip code list for rural areas. Clinical characteristics included CHA2DS2-VASc score, HAS-BLED score, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), recent bleeding, recent use of antiplatelet agents, recent use of Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), liver disease, alcohol disorder, and vascular disorder. CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED are validated scores for the risk of ischemic stroke and the risk of bleeding, respectively.24,25 Since claims data do not contain international normalized ratio (INR) levels, we calculated HAS-BLED score as the sum of all factors included in this score except labile INR, as previously done in the literature.10,26-29 To define factors included in these scores and other clinical characteristics, we used CMS Chronic Condition Warehouse definitions, when available.18 When not available, we used 12 months of claims data prior to AF diagnosis and published definitions of covariates (list in Supplemental Table 1).10,11,28,30-33

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We compared demographic, social determinants, and clinical characteristics across OAC adherence groups defined on the first day of follow-up (that is, on the basis of OAC use in the first 30 days after AF diagnosis) using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. We reported the frequency of ischemic strokes in each time-dependent exposure groups, as well as the unadjusted incidence rate per 100 person-years.

To control for differences in patient characteristics across exposure groups, we constructed Cox proportional hazard models, which regressed time to ischemic stroke against indicator variables for time-dependent exposure categories, including adherent use and not-adherent use (non-use was set as reference), and controlled for all covariates listed above except for CHA2DS2-VASc or HAS-BLED scores. This is because all of the factors included in the calculation of these scores were included in Cox models as individual covariates, so the inclusion of CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores could lead to collinearity issues. Time 0 was the index date (30-days after AF diagnosis) and the time at risk was censored at death, or end of follow-up period (330 days after index date). Sensitivity analyses were performed in a similar manner but defining exposure categories using 90% of days covered with OAC as the cut-off. Secondary analyses were performed following the same methodology including indicator variables for time-dependent DOAC adherent use, warfarin adherent use, and not-adherent use (non-use was again set as the reference). Finally, we also estimated the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke for the comparison between DOAC adherent and warfarin adherent use by changing the reference group. We did not perform a comparison between combined DOAC and warfarin adherent use and no use because combined DOAC and warfarin adherent use represented only 0.06% of the follow-up time, as shown in Table 2. All analyses were conducted with statistical software SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Table 2.

Number of Stroke Events and Unadjusted Incidence Rates of Ischemic Stroke Over 11 Months of Follow-up, by Adherence to Oral Anticoagulation Measured during Follow-up.

| Adherent Use | Non-Adherent Use | Non-Use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-years (% of Total Follow-up) | 11,192 (35.0%) | 3,497 (10.9%) | 17,268 (54.0%) |

| No. Ischemic Stroke Events | 163 | 67 | 471 |

| Incidence Ischemic Stroke per 100 p-y (CI) | 1.46 (1.25-1.70) | 1.92 (1.51-2.43) | 2.73 (2.49-2.99) |

Abbreviation: P-y=person-years.

Every day of the study, adherent use was defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation. Non-adherent use was defined as having more than 0% but less than 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation. Non-use was defined as having 0% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation.

The proportion of follow-up indicates the proportion of the total follow-up for all study participants that was spent on each time-dependent treatment group.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline Patient Characteristics

Patients who used OAC on the first 30 days after AF diagnosis were younger, more likely to be male, white, and ineligible for Medicaid or for low-income subsidy than non-users (Table 1). The proportion of rural residents was higher among OAC adherent users than among non-adherent and non-users (p-value<0.001). CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores and the prevalence of chronic conditions such as AMI, as Alzheimer Disease or other dementia or chronic kidney disease were higher for non-users than for adherent and non-adherent patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries Newly Diagnosed with Atrial Fibrillation, by Adherence to Oral Anticoagulation Measured during the First 30 Days after Diagnosis.

| Variable-n(%) | Adherent Users (n=12,073) |

Non-Adherent Users (n=5,234) |

Non-Users (n=21,965) |

P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | <0.001 | |||

| <65 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 6.7 | |

| 65-74 | 38.8 | 37.5 | 33.5 | |

| >=75 | 54.7 | 55.6 | 59.8 | |

| Female sex | 55.1 | 57.0 | 60.6 | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| White | 88.2 | 88.1 | 85.9 | |

| Black | 6.5 | 7.4 | 8.3 | |

| Hispanic | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

| Other | 3.8 | 3.3 | 4.2 | |

| Social Determinants | <0.001 | |||

| Eligibility for Medicaid | 23.6 | 23.5 | 29.9 | <0.001 |

| Eligibility for Low-income | 32.0 | 34.6 | 44.1 | |

| Subsidy | ||||

| Rural Residence | 25.0 | 22.8 | 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | <0.001 | |||

| 2-3 | 29.5 | 27.4 | 25.0 | |

| 4-5 | 42.6 | 40.8 | 39.9 | |

| ≥6 | 28.0 | 31.8 | 35.1 | <0.001 |

| HAS-BLED score a | ||||

| 0-1 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 5.9 | |

| 2-3 | 68.3 | 65.7 | 61.2 | |

| ≥4 | 24.5 | 27.5 | 32.9 | |

| AMI b | 7.3 | 7.5 | 9.5 | <0.001 |

| Alzheimer's Disease or Dementia b | 13.3 | 14.0 | 23.9 | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease b | 34.6 | 38.4 | 42.7 | <0.001 |

| Heart Failure b | 45.0 | 48.9 | 50.1 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes b | 45.8 | 47.0 | 46.5 | 0.317 |

| Hypertension b | 91.2 | 91.8 | 92.3 | 0.002 |

| Stroke or TIA b | 20.8 | 22.7 | 23.8 | <0.001 |

| Recent Bleeding c | 16.2 | 17.9 | 22.0 | <0.001 |

| Recent Antiplatelet use d | 12.5 | 12.5 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| Recent NSAID use e | 13.1 | 12.4 | 13.4 | 0.137 |

| Liver Disease | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Disorder | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 0.002 |

| Vascular Disease | 29.7 | 31.6 | 35.2 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AMI=Acute Myocardial Infarction; TIA= Transient Ischemic Attack; NSAIDs=Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug.

The HAS-BLED score is calculated as the sum of the following factors: age of 65 years or greater, labile INR, renal disease, liver disease, use of antiplatelet agents or NSAIDs, hypertension, a history of stroke, of major bleeding and of alcohol or drug use.25 Because Medicare claims data does not contain information on INR levels, we calculated the HAS-BLED score as the sum of all factors except labile INR.

AMI, Alzheimer’s Disease or related dementia, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, and a history of stroke or TIA were defined using the respective CMS Chronic Condition Warehouse definitions of each of these conditions.

Recent bleeding was defined as having a claim with ICD-9 codes for bleeding events in the year before index date.10,11,28,30-33

3.2. Average Follow-up in Time-Dependent Exposure Categories

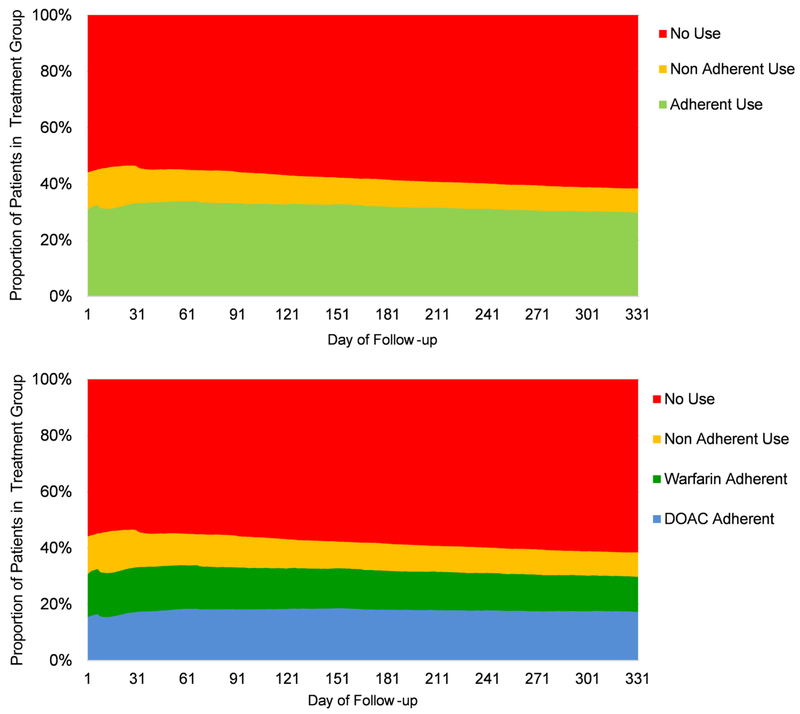

Study participants spent 35.0% of the follow-up period in the adherent use exposure category, 10.9% in the non-adherent category, and 54.0% in the non-use category (Figure 2). The proportion of patients accounted by each exposure category remained relatively stable across the study period. Specifically, the proportion of patients in the adherent use category averaged 31% during the first days of follow-up, increased to 34% in the second month of follow-up to later decrease to 30%. The proportion of patients in the non-adherent use category decreased from 13-15% in the first two months of follow-up to 8-9% at the end of the study period. In parallel, the proportion of patients on the non-use category increased over time from 54-56% to 62%. Over half of patients who belonged to the adherent use exposure category at the beginning of the study period also belonged to this exposure category at the end of the study period (Supplemental Table 2). Over 80% of patients who belonged to the non-use exposure category on the first day of the study period also belonged to this exposure category at the end of the study period. Supplemental Figure 1 shows the distribution of the number of days covered with OAC, by exposure category.

Figure 2. Proportion of Patients in Each Time-Dependent Treatment Group, Over 11 Months of Follow-up Period.

Abbreviations: DOAC=Direct Oral Anticoagulant.

The upper plot shows the proportion of patients in each time dependent group, measured every day of the study period with respect to adherence to oral anticoagulation in the previous 30 days. Specifically, adherent use was defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation; non-adherent use as having more than 0% but less than 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation; and non-use was defined as having 0% of the previous 30 days atrial covered with oral anticoagulation.

The lower plot shows the proportion of patients in each time dependent group, measured every day of the study with respect to adherence to DOACs and warfarin in the previous 30 days. Specifically, DOAC adherent use was defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with DOACs, and warfarin adherent use was defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with warfarin. Non-adherent use and non-use were defined as previously explained. Combined dual DOAC and warfarin use was not included in the plot because it represented only 0.06% of the follow-up period (Table 3).

DOAC adherent use represented 19.6% of the total follow-up period (or 56% of the follow-up period spent on the adherent use exposure category), warfarin adherent use 15.4% (or 44% of the time on the adherent use exposure category), and combined dual DOAC and warfarin adherent use less than 0.06% (Figure 2). The proportion of patients accounted by the DOAC adherent use category increased across the study period, from 15-16% in the first two months of follow-up to 18% at the end of the study period. In parallel, the proportion of warfarin adherent users decreased to represent at the end of the study period only 12% of the study population, or 42% of adherent users.

3.3. Unadjusted Rates of Ischemic Stroke

The unadjusted incidence rates of ischemic stroke were higher in the non-use exposure category [2.73 per 100 person-years (p-y); 95% CI, 2.49-2.99] than in the adherent use (1.46; 95% CI, 1.25-1.70) and non-adherent use (1.92; 95% CI, 1.51-2.43) exposure categories (Table 2). The unadjusted incidence rates of ischemic stroke per 100 p-y averaged 1.20; 95% CI, 0.96-1.50 in the DOAC adherent exposure category and 1.78; 95% CI, 1.44-2.19 in the warfarin adherent exposure category (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of Stroke Events and Unadjusted Incidence Rates of Ischemic Stroke Over 11 Months of Follow-up, by Adherence to Direct Oral Anticoagulants and Warfarin Measured during Follow-up.

| DOAC Adherent Use |

Warfarin Adherent Use |

Combined Dual DOAC and Warfarin Adherent Use |

Non-Adherent Use |

Non-Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-years (% of Total Follow-up) | 6,254 (19.6%) | 4,944 (15.4%) | 19 (0.06%) | 3,497 (10.9%) | 17,268 (54.0%) |

| No. Ischemic Stroke Events | 75 | 88 | 0 | 67 | 471 |

| Incidence Ischemic Stroke per 100 p-y (CI) | 1.20 (0.96-1.50) | 1.78 (1.44-2.19) | -- | 1.92 (1.51-2.43) | 2.73 (2.49-2.99) |

Abbreviations: DOAC=Direct Oral Anticoagulants; p-y=person-years.

Every day of the study, DOAC adherent use was defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with DOACs. Warfarin adherent use was defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with warfarin. Combined dual DOAC and warfarin use was defined as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation, but less than 80% of them covered with DOACs and less than 80% covered with warfarin. Non-adherent use was defined as having more than 0% but less than 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation. Non-use was defined as having 0% of the previous 30 days atrial covered with oral anticoagulation.

The proportion of follow-up indicates the proportion of the total follow-up for all study participants that was spent on each time-dependent treatment group.

The incidence of ischemic stroke was not estimated for the combined dual DOAC and warfarin adherent use because there were no events on this exposure category.

3.4. Adjusted Hazard Ratios of Ischemic Stroke

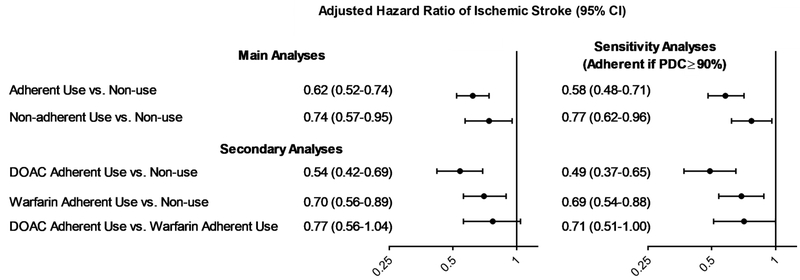

After adjustment for potential confounders, OAC adherent use (HR 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52-0.74) and non-adherent use (HR 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95) were associated with lower risk of ischemic stroke, compared to non-use (Figure 3). Estimates were robust to the definition of adherent use; using the ≥90% threshold, adherent use of OAC (HR 0.58; 95% CI, 0.48-0.71) and non-adherent use of OAC (0.77; 95% CI, 0.62-0.96) were associated with lower risk of stroke both compared to non-use.

Figure 3. Adjusted Hazard Ratios of Ischemic Stroke.

Abbreviations: PDC=Proportion of Days Covered; DOAC=Direct Oral Anticoagulant.

In the main analyses, adherent use was defined every day of the study as having at least 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation; non-adherent use was defined as having more than 0% but less than 80% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation; and non-use was defined as having 0% of the previous 30 days atrial covered with oral anticoagulation. In sensitivity analyses, adherent use was defined every day of the study as having at least 90% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation; non-adherent user was defined as having more than 0% but less than 90% of the previous 30 days covered with oral anticoagulation; and non-use was defined as having 0% of the previous 30 days atrial covered with oral anticoagulation.

Results from Cox Proportional Hazard models that adjusted for all covariates listed in Table 1, except for CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores. We did not perform a comparison between combined DOAC and warfarin adherent use and no use because combined DOAC and warfarin adherent use represented only 0.06% of the follow-up time, as shown in Table 3.

In secondary analyses, adherent use of DOACs (HR 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42-0.69) and of warfarin (HR 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.89) were associated with lower risk of stroke than non-use. The risk of stroke did not statistically differ between DOAC and warfarin adherent users (HR 0.77; 95% CI, 0.56-1.04).

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to estimate the reduction in the risk of stroke associated with adherent use of OAC in a sample of Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with AF, including those who never initiated OAC therapy. We found that, compared to no OAC use, adherent use of OAC reduced the risk of stroke by around 40%, while non-adherent use reduced it by 25%. Additionally, adherent use of DOAC was associated with a 31%-58% reduction in the risk of stroke, and adherent warfarin use with a 30% reduction. Newly diagnosed AF patients in Medicare adhere to OAC on average only around one third of the first year after first AF diagnosis.

Our findings for the prevalence of OAC underuse are consistent with extensive prior research reporting that only about 50-60% of patients with AF in the US receive OAC therapy.10-13 Given the lack of success of prior interventions and the recent evidence demonstrating large practice-level variation in OAC use,13 experts proposed the implementation of provider payment models that align health system financial incentives as one of the strategies most likely to mitigate OAC underuse.34,35 Along this line, the Pharmacy Quality Alliance recently endorsed the implementation of adherence to DOACs as a quality measure in the calculation of Medicare star ratings. While the implementation of adherence measures in the calculation of payments could improve medication adherence, this measure would not incentivize the mitigation of OAC underuse or the improvement of adherence to warfarin.17 The consideration of more comprehensive measures that incentivize not only adherence to DOACs but also the extended use of OAC among patients with AF recommended for this therapy and adherence to warfarin is warranted, given the strong benefit of stroke prevention associated with OAC adherent use. These interventions could have a large impact on clinical and economic outcomes - it has been estimated that reducing OAC underuse by half would avert 20,000 strokes annually and save Medicare $1.5 billion.36,37

Our study is subject to limitations. First, claims data only contain information on the filling of prescriptions but not on whether patients take medications. As a result, our analyses assumed that patients took OAC therapy as they filled prescriptions, although this may not necessarily be the case. For patients who discontinued OAC through the study period, we observed the day when they ran out of fills, but not the day when they specifically stopped taking OAC. For this reason, it is likely that we overestimated OAC use for discontinuers. Still, we minimized the impact of this measurement error by measuring OAC exposure on the basis of 30-day intervals, as opposed to shorter time windows. Additionally, we were not able to explore whether OAC underuse and lack of adherence are due to clinicians not prescribing OAC or discontinuing OAC or to patients not filling their prescriptions. Second, measuring adherence to warfarin based on PDC may contain inaccuracies, given the adjustments to warfarin dosing based on INR testing. Third, like all studies using claims data, we did not have detailed clinical information such as creatinine clearance or body weight, which are needed to calculate dose adjustments for DOACs. It is possible that patients recommended for high-dose treatment with DOACs received low-dose therapy because of concerns on bleeding risk,31 which could have biased our results towards the null. Fourth, while we controlled our analyses for a comprehensive list of patient characteristics, our results could be affected by unobserved differences in patient groups and could be subject to residual confounding. While propensity score analyses are often implemented to reduce confounding in observational studies, it was not possible to apply this methodology in our study due to the time-dependent definition of the main exposures of interest. Fifth, we were not able to evaluate outcomes of patients who switched between warfarin and DOACs because they represented a small proportion of the follow-up period (0.06%). Finally, our results may be affected by healthy adherer bias, because patients who adhere to OAC may also be more likely to adhere to lifestyle behaviors or other medications and medical services that are also associated with lower stroke risk.38,39

In this retrospective study of 2013-2016 Medicare claims data, we found that, although adherence to OAC reduces the risk of stroke by nearly 40%, Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with AF adhere to OAC on average only one third of the first year after first AF diagnosis. Underuse and lack of adherence to OAC remains a significant clinical challenge whose mitigation would have a major impact on stroke prevention.

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Continuous adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with a 40% reduction in the risk of stroke in patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation

However, patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation adhered to oral anticoagulation on average less than 35% of the first year after diagnosis

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (grant number K01HL142847).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Saba has received research support from Boston Scientific. Hernandez has received advisory board fees from Pfizer. He, Brooks and Gellad declare that that they have no potential conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

This work represents the opinions of the authors alone and does not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Contributor Information

Inmaculada Hernandez, Department of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, PA USA.

Meiqi He, Department of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, PA USA.

Maria M. Brooks, Department of Epidemiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, PA USA.

Samir Saba, Heart and Vascular Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Centre PA, USA.

Walid F. Gellad, Division of General Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, PA USA; VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, PA USA.

References

- 1.Hart RG, Halperin JL. Atrial fibrillation and stroke : concepts and controversies. Stroke. 2001;32(3):803–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogilvie IM, Newton N, Welner SA, Cowell W, Lip GY. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):638–645.e634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang K, Bozkaya D, Patel AA, et al. Anticoagulant use for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from a multi-payer analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakkar AK, Mueller I, Bassand J-P, et al. International longitudinal registry of patients with atrial fibrillation at risk of stroke: Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD (GARFIELD). Am Heart J. 2012;163(1):13–19.e11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel AA, Lennert B, Macomson B, et al. Anticoagulant Use for Prevention of Stroke in a Commercial Population with Atrial Fibrillation. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2012;5(5):291–298 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds MR, Shah J, Essebag V, et al. Patterns and Predictors of Warfarin Use in Patients With New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation from the FRACTAL Registry. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(4):538–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogilvie IM, Welner SA, Cowell W, Lip GY. Characterization of the proportion of untreated and antiplatelet therapy treated patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(1):151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alamneh EA, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR. Suboptimal Use of Oral Anticoagulants in Atrial Fibrillation: Has the Introduction of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Improved Prescribing Practices? Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2016;16(3):183–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez I, Zhang Y, Saba S. Comparison of the Effectiveness and Safety of Apixaban, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban and Warfarin in Newly Diagnosed Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2017; 120(10): 1813–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez I, Saba S, Zhang Y. Geographic Variation in the Use of Oral Anticoagulation in Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation. Stroke 48:2289–2291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marzec LN, Wang J, Shah ND, et al. Influence of Direct Oral Anticoagulants on Rates of Oral Anticoagulation for Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(20):2475–2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu JC, Maddox TM, Kennedy KF, et al. Oral Anticoagulant Therapy Prescription in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Across the Spectrum of Stroke Risk: Insights From the NCDR PINNACLE Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(1):55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao X, Abraham NS, Alexander GC, et al. Effect of Adherence to Oral Anticoagulants on Risk of Stroke and Major Bleeding Among Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borne RT, O’Donnell C, Turakhia MP, et al. Adherence and outcomes to direct oral anticoagulants among patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the veterans health administration. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2017;17(1):236 10.1186/s12872-017-0671-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naccarelli GV, Varker H, Lin J, Schulman KL. Increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(11):1534–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crivera C, Nelson WW, Bookhart B, et al. Pharmacy quality alliance measure: adherence to non-warfarin oral anticoagulant medications. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(10):1889–1895. 10.1185/03007995.2015.1077213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. 27 Chronic Condition Algorithm. https://www.ccwdata.org/cs/groups/public/documents/document/ccw_condition_categories.pdf Accessed April 26, 2017.

- 19.Kumamaru H, Judd SE, Curtis JR, et al. Validity of claims-based stroke algorithms in contemporary Medicare data: reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study linked with medicare claims. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(4):611–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo-Ciganic WH, Donohue JM, Jones BL, et al. Trajectories of Diabetes Medication Adherence and Hospitalization Risk: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Large State Medicaid Program. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1052–1060. 10.1007/s11606-016-3747-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo-Ciganic WH, Donohue JM, Thorpe JM, et al. Using machine learning to examine medication adherence thresholds and risk of hospitalization. Med Care. 2015;53(8):720–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao X, Abraham NS, Sangaralingham LR, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, and Apixaban Versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(6):e003725. doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.003725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zalesak M, Siu K, Francis K, et al. Higher persistence in newly diagnosed nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients treated with dabigatran versus warfarin. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(5):567–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137(2):263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138(5):1093–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman CI, Peacock WF, Bunz TJ, Alberts MJ. Effectiveness and Safety of Apixaban, Dabigatran, and Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation and Previous Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke. 2017;48(8):2142–2149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desai NR, Krumme AA, Schneeweiss S, et al. Patterns of initiation of oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation- quality and cost implications. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1075–1082.e1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez I, Zhang Y, Brooks MM, Chin PK, Saba S. Anticoagulation Use and Clinical Outcomes After Major Bleeding on Dabigatran or Warfarin in Atrial Fibrillation. Stroke. 2017;48(1):159–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham NS, Singh S, Alexander GC, et al. Comparative risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez I, Baik SH, Pinera A, Zhang Y. Risk of bleeding with dabigatran in atrial fibrillation. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):18–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez I, Zhang Y. Comparing Stroke and Bleeding with Rivaroxaban and Dabigatran in Atrial Fibrillation: Analysis of the US Medicare Part D Data. Am J Cardiovasc Drug. 2017;17(1):37–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray M, Saba S, Zhang Y, Hernandez I. Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation Patients Newly Recommended for Oral Anticoagulation under the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline J Am Heart Assn.7(1):e007881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez I, Zhang Y, Saba S. Effectiveness and Safety of Direct Oral Anticoagulants and Warfarin, Stratified by Stroke Risk in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(1):69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson ED, Pokorney SD. New Treatment Options Fail to Close the Anticoagulation Gap in Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(20):2485–2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hess PL, Mirro MJ, Diener HC, et al. Addressing barriers to optimal oral anticoagulation use and persistence among patients with atrial fibrillation: Proceedings, Washington, DC, December 3-4, 2012. Am Heart J. 2014;168(3):239–247.e231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caro JJ. An economic model of stroke in atrial fibrillation: the cost of suboptimal oral anticoagulation. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(14 Suppl):S451–458 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel AA, Ogden K, Veerman M, Mody SH, Nelson WW, Neil N. The economic burden to medicare of stroke events in atrial fibrillation populations with and without thromboprophylaxis. Popul Health Manag. 2014;17(3):159–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shrank WH, Patrick AR, Brookhart MA. Healthy user and related biases in observational studies of preventive interventions: a primer for physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(5):546–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersohn F, Willich SN. The Healthy Adherer Effect. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1633–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.