Abstract

Purpose:

Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade is a promising treatment for resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), yet immunological mechanisms contributing to tumor regression and biomarkers of response are unknown. Using paired tumor/blood samples from a phase 2 clinical trial ( NCT02259621), we explored whether the peripheral T cell clonotypic dynamics can serve as a biomarker for response to neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade.

Experimental Design:

T cell receptor (TCR) sequencing was performed on serial peripheral blood, tumor and normal lung samples from resectable NSCLC patients treated with neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade. We explored the temporal dynamics of the T cell repertoire in the peripheral and tumoral compartments in response to neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade by using the TCR as a molecular barcode.

Results:

Higher intratumoral TCR clonality was associated with reduced percent residual tumor at the time of surgery, and the TCR repertoire of tumors with major pathologic response (MPR; <10% residual tumor after neoadjuvant therapy) had a higher clonality and greater sharing of tumor infiltrating clonotypes with the peripheral blood relative to tumors without MPR. Additionally, the post-treatment tumor bed of patients with MPR was enriched with T cell clones that had peripherally expanded between weeks 2–4 after anti-PD-1 initiation and the intratumoral space occupied by these clonotypes was inversely correlated with percent residual tumor.

Conclusions:

Our study suggests that exchange of T cell clones between tumor and blood represents a key correlate of pathologic response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy, and shows that the periphery may be a previously underappreciated originating compartment for effective anti-tumor immunity.

Keywords: Neoadjuvant, PD-1 Blockade, T cell dynamics, TCR repertoire

Introduction

PD-1/PD-L1 axis blockade enhances antitumor immunity, induces sustained tumor regression, and extends overall survival in many advanced cancers (1). More recently, neoadjuvant PD-1/PD-L1 pathway blockade in earlier stage lung cancer has shown clinical efficacy (2,3) while inducing peripheral expansion of mutation-associated neoantigen-specific T-cell clones (3). Neoadjuvant phase 3 clinical trials incorporating PD-1 blockade are now active across multiple solid tumors (3–6).

T cells are key determinants of immune response to checkpoint blockade. Blockade of PD-1 signaling with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies reinvigorates pre-existing tumor-specific T cell clones (7). In addition to PD-L1 expression (8), other immune correlates of clinical response to PD-1 blockade include CD8+ T cell infiltration (9), the presence of PD-1+CD8+ T cells at the invasive tumor margin (9,10), high densities of CD45RO+granzyme+ T cells (11), IFN-γ associated gene expression (12), the proximity of PD1+ to PDL1+ cells (13), and CD8/Ki-67 co-expression (9). Peripheral expansion of intratumoral clonotypes (14) and proliferation of peripheral Ki-67+ PD-1+ CD8+ T cells (15) have been linked with clinical benefit from PD-1 blockade in advanced NSCLC using pre-treatment tumor specimens, but connecting these changes with the intratumoral immune response after treatment has not be done. Herein we report the coordinated dynamics of the peripheral and tumor-infiltrating T cell repertoire following neoadjuvant anti-PD1 treatment in resectable NSCLC. We analyzed specimens collected during a clinical trial evaluating the safety and feasibility of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable NSCLC ( NCT02259621). The neoadjuvant setting, whereby PD-1 blockade is given before surgical resections, was introduced based on the hypothesis that the “in-place” tumor at the time of immunotherapeutic intervention could serve as a large antigen source to drive enhanced systemic anti-tumor immunity (3). The neoadjuvant format also provides a unique opportunity to monitor the TCR repertoire across time (in serial peripheral blood draws) and space (across different biological compartments) according to pathologic response.

Because the T cell receptor (TCR) confers unique antigen specificity, we use TCR Vβ CDR3 sequencing (TCRseq) to track intra-tumoral clonotypes (ITCs) over time and across biological compartments to show that treatment-induced peripheral TCR repertoire remodeling correlates with increased tumor infiltration of T cells and major pathologic response (MPR). Specifically, peripheral T cell clonotypic expansion between weeks 2–4 after neoadjuvant anti-PD1 treatment initiation correlated with greater intratumoral clonotype accumulation for patients with MPR. These results indicate that the peripheral blood TCR repertoire is an important compartment for rejuvenating anti-tumor immunity.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The biospecimens evaluated in this study were obtained from patients enrolled to a phase 2 study evaluating the safety and feasibility of preoperative administration of nivolumab in patients with high-risk resectable NSCLC, along with a comprehensive exploratory characterization of the tumor immune milieu and circulating immune cells and soluble factors in these patients ( NCT02259621). Specifically, 21 adults with untreated, surgically resectable (stage I, II, or IIIA) NSCLC were enrolled. Two preoperative doses of Nivolumab (at a dose of 3 mg per kilogram of body weight) was administered intravenously every 2 weeks, with surgery planned approximately 4 weeks after the first dose (3). Longitudinal peripheral blood samples (pre-, post-treatment and follow-ups), pre- and post-treatment tumor samples, post-treatment lymph nodes and normal lung tissues were collected (Fig. 1A and Table S2). Normal lung tissues were sampled 10–15 cm from tumor margin of surgically-resected specimens. Pathologic response and tumor mutational burden for each patient are shown in Supplementary Table 2. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Johns Hopkins University and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Figure 1. Clonality of the TCR repertoire and association with the anti-tumor response.

A. Flow chart of the phase 2 clinical trial and biospecimen collection, along with correlative studies performed at each timepoint. B. Correlation between productive clonality in the tumor bed at the time of resection (after anti-PD-1) with the number of non-synonymous sequence alterations (Spearman’s rho, 0.70; P=0.025). Each patient is represented by a black dot (n=10). The blue line indicates the linear regression line, and the gray area indicates the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% confidence interval. C. Correlation between productive clonality in the post-treatment tumor bed and the percent residual tumor (n=10, Spearman’s rho, −0.65; P=0.041). The blue line indicates the linear regression line, and the gray area indicate the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% confidence interval. Productive clonality: Clonality as determined by using the productive amino acid (AA) sequence of the CDR3. D. Productive clonality of the TCR repertoire in the post-treatment tumor bed and normal lung for patients with major pathologic response (MPRs; blue) and without MPR (non-MPR; red). E, Occupied clonal space (the total frequency among all intratumoral T cells) of ITCs according to their percent rank (top 1% ranked ITCs vs top 1–2% ranked ITCs vs top 2–5% ranked ITCs vs >5% ranked ITCs) in the post-treatment tumor bed of each patient. F. Comparison of the clonal space occupied by ITCs segregated by frequency-ranks between MPRs (n=9) and non-MPRs (n=5).

T cell receptor (TCR) sequencing and assessment of the TCR repertoire

DNA was extracted from post-treatment tumor tissue, normal lung tissue, lymph nodes, and longitudinal pre- and post-treatment peripheral blood using a Qiagen DNA blood mini kit, DNA FFPE kit, or DNA blood kit, respectively (Qiagen). TCR V β CDR3 sequencing was performed using the survey (tissues) or deep (PBMC) resolution ImmunoSEQ platforms (16) (Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA). TCR repertoire diversity was assessed by productive clonality, which is a measure of species diversity (17). To normalize between samples that contain different numbers of total CDR3 TCRβ sequencing reads, entropy was divided by log2 of the number of unique productive sequences. Nonproductive TCR CDR3 sequences (premature stop or frame-shift), sequences with amino acid length less than 5, and sequences not starting with “C” or ending with “F/W” were excluded from the final analyses.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for PD-1 positive T cells in PBMC

Treatment-induced dynamics of exhausted T cells were assessed by tracking clones with upregulation of PD-1. PBMC obtained at baseline, immediately prior to the first anti-PD-1 infusion, were washed and incubated with BV786-conjugated anti-CD8 (RPA-T8), BV605-conjugated anti-CD3 (SK7), BV510-conjugated anti-CD4 (SK3), and PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-PD-1 (EH12.1) for 30 minutes at 4C. Cells were washed, resuspended in FACS Buffer, and live CD3+ T cells were sorted into four populations: CD4+/PD-1−, CD4+/PD-1+, CD8+/PD-1−, and CD8+/PD-1+ using the FACSAria Fusion SORP cell sorter (BD, San Jose, CA). gDNA extractions were performed on sorted cells and samples were subsequently sent for TCR sequencing as described above.

Identification of differentially expanded/contracted clones in PBMC

Bioinformatic and biostatistical analysis of differentially expanded/contracted clones in PBMC after each dosing of anti-PD-1 monotherapy was performed using Fisher’s exact test with multiple testing correction by Benjamini-Hochberg procedure which controls false discovery rate (FDR <0.05) (18). Differential clonotypes were further analyzed for tissue and longitudinal PBMC representation in MPRs and non-MPRs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software. The Mann Whitney U test was used for comparison of 2-group data. For analysis of >2 group data, Kruskal–Wallis H test was used. Spearman’s rho was used to measure the correlation between two continuous variables. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated and P < 0.05 was considered significant. ns: p > 0.05, *: p <= 0.05, **: p <= 0.01, ***: p <= 0.001, ****: p <= 0.0001.

Results

Intratumoral TCR repertoire is associated with pathologic response to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1

We previously reported the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in treatment naïve, surgically resectable (stage I, II, or IIIA) NSCLC (3). Briefly, 21 patients were treated with two preoperative doses of anti-PD-1 with minimal toxicity and no delays to surgery. Among the 20 patients who underwent surgical resection, 9 had ≤10% residual viable tumor upon histopathological examination of the surgically resected tumor (Table S1). An overview of the trial design and biospecimen collection is shown in Fig. 1A and Table S2.

Because T cell clonality in the tumor has been associated with clinical outcome in metastatic cancers (9), we first assessed whether clonality of the intra-tumoral TCR repertoire following neoadjuvant anti-PD1 may reflect an anti-tumor immune response. TCRseq on post-treatment (resection) tumor bed was performed to determine the clonality of the intratumoral repertoire. A clonality value of 0 represents the most diverse repertoire (every T-cell in a sample contains a unique TCR) whereas a value of 1 represents a monoclonal T-cell population. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was also evaluated as a potential correlate of immunological response. The methods and results of whole exome sequencing and tumor mutational burden have been reported previously (3). TMB positively correlated with intratumoral clonality (Spearman’s rank correlation, R=0.7, P=0.025; Fig. 1B), suggesting expansion of a small subset of clonotypes in high TMB tumors. An inverse association was observed between intratumoral TCR repertoire clonality and percent residual tumor at the time of surgery (Spearman’s rank correlation, R=−0.65, P=0.041, Fig. 1C). No correlation was observed between the total number of reads (ie. total number of sequenced cells) used for TCRseq and percent residual tumor or intratumoral clonality (Fig. S1–S2), indicating that differences in sample yield or T cell number did not bias our analysis. These observations support the hypothesis that high TMB increases the likelihood that one or several mutations can drive a clonally skewed intratumoral T cell repertoire leading to tumor pathologic regression. Post-treatment tumor, but not normal lung tissue, from patients with MPR had a significantly higher T cell clonality relative to patients with non-MPR (Mann–Whitney U test, P=0.0085, Fig. 1D). Conversely, patients with MPR had a trend toward lower clonality in the peripheral blood compared to non-MPRs at each longitudinal timepoint, although this was not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U test, all p>0.05, Fig. S3). These findings of increased clonality only inside the tumor suggest that these changes may be directly related to tumor recognition, with the caveat that antigen-specific recognition is not assessable by TCRseq alone.

We then tested if the most abundant intratumoral clonotypes (ITCs), rather than all ITCs, were specifically contributing to the difference in T cell repertoire between MPRs and non-MPRs. ITCs were ranked according to their frequency as the top 1%, top 1–2%, 2–5% and >5% most frequent clonotypes in the resected tumor bed. T cell clonal space was defined and calculated as the summed frequency of clones in each of the four respective groups relative to the total T cell repertoire. There was no difference for clonotype richness, defined as total number of unique clonotypes, among the different ranges between MPRs and non-MPRs. However, consistent with the clonality calculations described above, the top 1% most abundant ITCs occupied a significantly greater clonal space in MPRs compared to non-MPRs (Mann–Whitney U test, median: 31.6% vs 18.8%, P=0.011, Fig. 1E–F), suggesting the top frequency-ranked ITCs may drive the anti-tumor response. Of note, MPR patient MD-01–010 with relatively low clonal space for top 1% ITCs had 100% PD-L1 positivity on pre-treatment tumor immunohistochemistry staining. Of the 788 top 1% ITCs from 16 patients with available tumor TCR data, only 1 clonotype was detected to be shared across patients (CDR3: CASSLGQAYEQYF, shared between patient NY016–007 and patient NY016–009, both were non-MPR), suggesting that the anti-tumor TCR repertoire was unique to each patient in our cohort.

Top 1% most abundant ITCs have the highest compartmental dynamics during PD-1 blockade

Using the TCR Vβ CDR3 as a biological barcode, we next assessed the cross-compartment (normal lung and pre-treatment blood) and temporal (before-treatment, on-treatment, and post-treatment blood) dynamics of ITCs, identified as T cell clonotypes that were detected in the resected tumor bed, and its association with pathologic response. The top 1% most frequent ITCs had a significantly higher proportion shared between the pre-treatment peripheral blood and resected normal lung as compared with less highly represented ITCs– ie. non-top 1% frequency-ranked clonotypes (Mann–Whitney U test, median: 61.6% vs 28.8%, P=1.1e-5; 81.4% vs 24.5%, P=1.4e-5, respectively, Fig. 2A). Notably, MPRs had a higher proportion of top 1% most frequent ITCs detected in pre-treatment blood (Mann–Whitney U test, median: 85.7% vs 55.6%, P=0.045, Fig. 2B) and normal lung (Mann–Whitney U test, median, 94.3% vs 70.6%, P=0.023, Fig. 2B) as compared to non-MPRs. No significant differences were found between MPRs and non MPRs for non-top 1% frequency-ranked ITCs (all p>0.1, Fig. S3). The high proportion of ITCs mobilizing across blood and normal lung, and in particular for top 1% frequency-ranked ITCs among MPR patients, suggests an active trafficking of anti-tumor T cells between the tumor and other biological compartments.

Figure 2. Dynamics of ITCs across tissue compartments and in longitudinal peripheral blood.

A. Proportion of ITCs shared between pre-treatment blood and normal lung, comparing non-top 1% ITCs (blue) and top 1% ITCs (red) (n=14). B. Top 1% ITCs shared between pre-treatment blood and resected normal lung, comparing MPRs (blue) and non-MPRs (red) (n=14). C. Proportion of top 1% ITCs by their shared compartment (pre-treatment blood+resected normal lung, pretreatment blood, resected normal lung, and tumor resident only). D. Clonal space of top 1% ITCs by shared compartment between MPRs and non-MPRs (n=14). The proportion of top 1% ITCs that are shared with the pre-treatment peripheral blood and resected normal lung is higher in MPRs vs. non-MPRs. However, an inverse correlation was observed for top 1% frequency-ranked ITCs that were only found in the tumor bed. E. Temporal dynamics of the ITCs in the longitudinal blood (n=14). The percent change of top 1% ITCs shared with the peripheral repertoire over time was calculated as compared to pre-treatment blood. Data show the mean +/− standard error for all patients (left panel) and by MPRs vs. non-MPRs (right panel) for top 1% ITCs (red) and non-top 1% ITCs (blue). F. The pattern and degree of peripheral remodeling at week 2 and week 4 following treatment initiation for all patients. The fold change of each clonotype was calculated, and the means of the fold change were plotted on a logarithmic scale (log10), stratified by the abundance ranks in the post-treatment tumor bed (n=14). The left and right panels show the dynamic magnitude in clones that underwent peripheral expansion and contraction, respectively. *: p <= 0.05, **: p <= 0.01, ***: p <= 0.001, ****: p <= 0.0001. G. The dynamic peripheral reshaping of individual TCR Vβ clonotypes for a representative patient (MD043–003, 5% residual tumor) during treatment and in long term follow up is shown. Each point on the scatter plots represents a single clonotype with normalized log10 clone frequency graphed at pairwise timepoints. The size of the dot represents the frequency in the tumor bed and clones are designated as top 1% ITCs(red), non-top 1% ITCs (blue), or PBMC only (gray). Clones that underwent contraction are found below the x=y diagonal, whereas those expanded are found above the diagonal. To account for clones that were only present in one sample, the frequency was recalculated by adding a pseudo count of 20 to all clonotype counts.

Top 1% ITCs were then categorized into 4 mutually-exclusive subsets: ITCs shared in the pre-treatment blood and the resected normal lung; ITCs found only in the pre-treatment blood; ITCs found only in the resected normal lung; and tumor-resident ITCs (not found in the resected normal lung or the pre-treatment blood). Although the total number of top 1% ITCs was comparable in MPRs and non-MPRs (Fig. 5S), MPRs had a greater proportion of top 1% ITCs shared with both pre-treatment blood and the resected normal lung compartment (Mann–Whitney U test, median, 81.0% vs 50.7%, P=0.053, Fig. 2C, Fig. S6). In contrast, a greater proportion of the top 1% tumor-resident ITCs was observed in non-MPRs as compared to MPRs (Mann–Whitney U test, median, 21.4% vs 3.6%, P=0.013, Fig. 2C, Fig. S7), suggesting that more migratory T cell clones correlated with the anti-tumor response. Supporting this notion, total ITCs shared with both the pre-treatment blood and the resected normal lung occupied a higher clonal space in MPRs as compared to non-MPRs (P=0.011); whereas non-MPRs had a greater clonal space occupied by tumor-resident ITCs (P=0.048, Fig. 2D). It is conceivable that the normal lung TCR repertoire could be a reflection of the increased vascularization in healthy lung rather than true tissue-resident T cells, however the normal lung had significantly fewer shared clones with the peripheral blood compared to the level of sharing between blood samples obtained from different timepoints (median 18 % vs 53%, Wilcoxon: p=1.5e-07), thereby demonstrating the presence of a T cell repertoire specific to the normal lung. No difference was found in the clonal space of ITCs shared with only the pre-treatment blood or the resected normal lung between MPRs and non-MPRs (all P>0.1). These observations suggest that the difference of the top clonal space occupied by the top 1% ITCs between MPRs and non-MPRs could be driven by ITCs trafficking through the blood and normal lung, which could mark a consort of T cells associated with pathologic response.

Peripheral “TCR repertoire remodeling” (i.e. fluctuations in the frequency and composition of T cell clonotypes within the repertoire) has been demonstrated in metastatic melanoma patients treated with anti-CTLA4 (19). In our study here, we characterized the repertoire remodeling in response to PD-1 blockade by evaluating the temporal dynamics of TCR repertoire in blood before, during, and after neoadjuvant treatment and linking these alterations with their tumor-infiltrating status. Between treatment initiation and surgery, the proportion of top 1% ITCs shared with the peripheral TCR repertoire significantly increased at week 2 and week 4 relative to baseline and declined after tumor resection (one sample t test, both P<0.0005, Fig. 2E). Both MPRs and non-MPRs had an increased percent of top 1% ITCs in the peripheral blood during anti-PD-1 treatment. However, non-MPRs showed an earlier decline of top 1% ITCs compared to MPRs (Fig. 2E). No significant increase in shared TCRs between non-top 1% ITCs and peripheral blood were observed in MPRs or non-MPRs at each timepoint (all p>0.05). These findings indicate that top-ranked ITCs are readily detected in peripheral blood before treatment, increase in the periphery subsequent to PD-1 blockade regardless of MPR status, and decrease in the peripheral blood after tumor resection/removal of tumor antigen, consistent with T cell repertoire turnover in response to treatment. Yet this pattern was not present among non-top 1% ITCs, bolstering the notion that top 1% ITCs were key migratory T cells.

We further systematically evaluated peripheral dynamics of ITCs in all patients at pairwise timepoints during PD-1 blockade. Clonotypes with a significant increase in abundance compared to the previous timepoint were defined as expanded clones, whereas those with a significant decrease in abundance were defined as contracted clones. We quantified the degree of TCR repertoire remodeling by clonotypic fold change between pairwise timepoints. Peripheral clones were grouped based on their representation in the tumor bed as PBMC-only clonotypes, non-top 1% frequency-ranked ITCs, and top 1% frequency-ranked ITCs. Both non-top 1% ITCs and the top 1% ITCs showed greater fold changes of expansion and contraction as compared to PBMC-only clonotypes during anti-PD-1 treatment (Fig. 2G). Particularly, the top 1% ITCs consistently showed the highest degree of reshaping, regardless of MPR status. To consolidate our hypothesis that perturbations of the peripheral T cell repertoire were specific to anti-PD-1 treatment and not the result of random fluctuations in the TCR repertoire, we evaluated changes in frequency between two long-term follow-up timepoints taken 6 months apart, during which a significant amount of peripheral repertoire turnover would be expected relative to timepoints taken 2 weeks apart, in a patient who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy and had serial blood samples for >1 year after surgery. Top 1% ITCs detected in the peripheral blood underwent appreciable peripheral expansions and contractions during the 4 weeks of anti-PD-1 treatment (Fig. 2F, time window: pre-treatment to week 2; week 2 to week 4). Strikingly, limited remodeling of the peripheral TCR repertoire was observed during the 6-month follow-up interval relative to on-treatment timepoints (Fig. 2F, right panel), suggesting the systematic remodeling in the peripheral repertoire is a direct, early effect of PD-1 pathway blockade.

Clonal expansion of ITCs in peripheral blood correlates with pathologic response

We next sought to identify the kinetic pattern and time window of TCR remodeling that correlates with tumor regression upon PD-1 blockade. We recently detected peripheral expansion of neoantigen-specific peripheral T cell clonotypes that were also observed in high abundance in the post-treatment tumor in a single patient with MPR (3). We therefore hypothesized that peripherally-expanded clones may home to the tumor (primary and potentially undetected micrometastatic deposits) to produce the anti-tumor response. Clonotypes undergoing contraction or expansion were identified in pairwise timepoints (pre-treatment vs week 2; week 2 vs week 4) during neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade using methods previously described and controlling for an FDR of 0.05 (18). A total of 689 dynamic clonotypes were found among 17 patients with available serial blood samples (Fig. S7). Compared with non-dynamic clones, dynamic clones are more likely to be intratumoral clones, regardless of MPR status (Fig. 3A) and clones that contracted in the periphery between pre-treatment and week 2 were more likely to be in the tumor bed as compared to those contracted at between weeks 2 to 4; in contrast, clones expanded between weeks 2 to 4 were more likely to infiltrate the tumor bed (Fig. 3B). No difference was observed for the proportion of non-dynamic clones in the tumor bed. Furthermore, the intratumoral clonal space of clones expanded between weeks 2 to 4 was inversely correlated with residual tumor (Spearman’s rank correlation, R=−0.62, P=0.041, Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Differentially dynamic clones and their association with tumor infiltration and tumor accumulation.

A. The proportion of dynamic clones vs non-dynamic clones that infiltrated tumor bed upon PD-1 blockade in MPR and non-MPR (n=12). B. The total proportion of clones in the tumor is shown for significantly contracted clones, significantly expanded clones, and non-dynamic clones at week 2 (dark grey) and week 4 (light grey) after treatment initiation (n=12). C. Association of intratumoral clonal space of peripherally expanded clones and percent residual tumor by time window (pre-treatment~W2, Spearman’s rho=−0.35, W2~W4 Spearman’s rho=−0.62). Each patient is represented by a black dot. The blue line indicates the robust linear regression line (fitted using R function ‘rlm’ from ‘MASS’ package based on M estimator), and the gray area indicates the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% confidence interval (n=12). D. The clonal space occupied by ITCs with different peripheral dynamic patterns (expanded, contracted, non-dynamic or tumor resident-only) at 2–4 weeks after immunotherapy initiation is shown for MPRs and non-MPRs (n=12). E. The clonal space occupied by normal lung T cells with differential patterns in the periphery is shown for MPRs and non-MPRs at 2–4 weeks after treatment initiation (n=12). F. The proportion of top 1% ITCs and their peripheral dynamic pattern at 2–4 weeks after treatment initiation for MPRs and non-MPRs (n=12). G. Proposed schema of peripheral activation of the anti-tumor repertoire homing back to the tumor bed. ns, not significant. *: p <= 0.05, **: p <= 0.01, ***: p <= 0.001.

Because peripherally-dynamic clones are thought to be trafficking to the tumor, we tested if intratumoral clonal occupancy of clones with differential peripheral patterns differentiates MPRs from non-MPRs. ITCs were stratified as peripherally contracted, expanded, non-dynamic, or tumor-resident only based on their different dynamic patterns during treatment. There were no differences in the intratumoral clonal space of peripherally contracted, expanded, or non-dynamic clones between pre-treatment to week 2 (Mann–Whitney U test, all p >0.05, Fig. S8). However, ITCs that specifically expanded between 2 to 4 weeks from anti-PD-1 treatment initiation demonstrated a significantly greater clonal space in MPRs compared to non-MPRs (P = 0.018, Mann–Whitney U test, Fig. 3D), suggesting an enhanced anti-tumor response with the influx or efflux of peripherally expanded clones. Moreover, no difference was observed in the intratumoral clonal space of tumor-resident only clones between MPRs and non-MPRs (Fig. 3D), consistent with a previous study suggesting low and variable tumor reactivity of the intrinsic tumor-resident TCR repertoire (20).

To further interrogate the tumor-specific localization of expanded clones, we repeated the analysis on clonotypes found in normal lung and observed no statistically significant difference in representation of differential clonotypes between MPR and non-MPR (Fig. 3E), suggesting an enrichment of peripherally-expanded clones that are specifically concentrated within the tumor. In addition, we found the top 1% ITCs of MPRs were preferentially constituted of peripheral clones expanded at week 2–4 (Fig. 3F) as compared to non-MPRs (median, 17.7% vs 0.3%, Mann–Whitney U test, P=0.012). No differences in clonotype composition among top 1% ITCs were observed for contracted, non-dynamic, or tumor-resident only clones between MPRs vs non-MPRs (all P>0.1). Based on the above observations, we proposed the model that T cell clones trafficking between the tumor and peripheral blood, particularly those differentially expanded at 2–4 weeks after PD-1 blockade may be responsible for tumor regression (Fig. 3G).

A complete pathologic responder is characterized by significant expansion of PD-1+ ITCs in the periphery

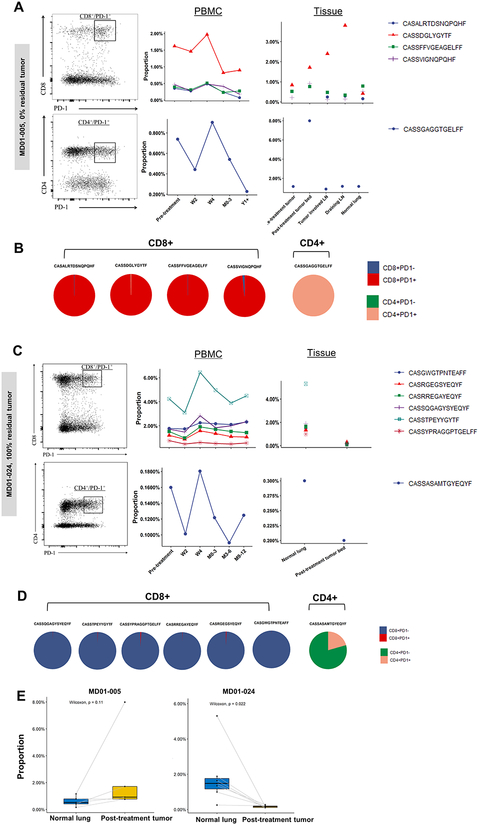

Our data suggest that PD-1 blockade rejuvenates pre-existing peripheral T cells that expand upon treatment and accumulate in tumor tissues. As prior studies have demonstrated PD-1 expression to be reflective of a subset of PD-1-blockade responsive, tumor-specific T cells, we examined the PD-1 expression status of these expanded ITCs using TCRseq of sorted PD-1+ and PD-1− peripheral blood T cells. This analysis focused on two patients with extreme but opposite responses to neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade: a complete pathologic responder, patient MD01–005, with 0% residual primary tumor with minimal tumor involvement of an adjacent lymph node, and non-responding patient MD01–024, with 100% residual tumor. In the pathologic responder (MD01–005), among the 5 top 1% ITCs that differentially expanded between 2–4 weeks after treatment initiation, all were found to be PD-1+ in the pre-treatment peripheral blood (4 PD-1+CD8+ clones; 1 PD-1+CD4+ clone, Fig. 4A). These clonotypes were additionally found to be top 1% clonotypes in a tumor-involved lymph node and a tumor draining lymph node obtained at the time of surgical resection (Fig. 4A). PD-1 intraclonal positivity, defined as the percent of a unique clonotype that was found within the PD-1+ population, was markedly high for all 5 clonotypes in MD01–005 (Fig. 4b, median: 99%, range: 98%−100%). By contrast, for the non-responder (MD01–024), the 7 top 1% ITCs that expanded at 2–4 weeks demonstrated low PD-1 intraclonal positivity (median: 0.6%, range: 0.2%−20.6%, Fig.4C–D). Moreover, these expanded clones in the tumor bed of the non-responder had a significantly lower proportion in the tumor relative to normal lung (Paired Wilcoxon test, P=0.022, Fig. 4E). These results suggest that peripheral expansion is indicative of activation and migration of PD1+ T cells into the tumor microenvironment, which could subsequently facilitate pathologic response in the tumor bed.

Figure 4. PD1 sorting revealed differential patterns of intra-clonal PD1+ positivity between complete pathologic responder and non-responder.

A. TCRseq was performed on sorted PD-1 positive and negative CD4+ and CD8+ peripheral blood T cells obtained from patient MD01–005 (0% residual tumor) prior to treatment (left panel). The frequency of clonotypes detected in the PD-1+ population is shown in serial peripheral blood (center) and biopsied and resected tissues (right) is shown. All 5 differentially expanded ITCs identified in this patient were detected in the PD1+ sorted population. B. Pie charts showing the intra-clonal PD-1 positivity (the proportion of total reads of each clone that was detected in the PD-1+ vs. PD-1− sorted population) for the 5 peripherally expanded, top 1% ITCs is shown. C. TCRseq was performed on sorted PD-1 positive and negative CD4+ and CD8+ peripheral blood T cells obtained from patient MD01–024 (100% residual tumor) prior to treatment (left panel). The frequency of clonotypes detected in the PD-1+ population is shown in serial peripheral blood (center) and resected tissues (right). D. Pie charts showing the intraclonal PD-1 positivity for peripherally expanded, top 1 % ITCs. E. The read proportion of top 1% ITCs in the normal lung and tumor bed is shown for patient MD01–005 and patient MD01–024. Comparisons between normal lung and tumor bed were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Discussion

We recently identified neoantigen-specific T-cell clones in blood obtained prior to anti-PD-1, at the pre-operative visit, and after surgery in a patient with MPR, with a transient expansion of these clones in peripheral blood after treatment initiation (3,18). Based on this observation, we hypothesized that trafficking of relevant T cell clones between the periphery, normal tissues, and tumor would be important for effecting pathologic response. We therefore performed a comprehensive assessment of T cell repertoire and dynamics in the neoadjuvant setting and further sought to determine if specific variables of clonal dynamics may be an early biologic correlate of anti-tumor immunity. As such, we used pathologic response to PD-1 blockade as an outcome. While longer follow-up will be necessary to determine how pathologic response correlates with clinical outcome in lung cancer, reports in melanoma indicate that early pathologic responses to anti-PD-1 indeed correlate with improved survival (21,22).

In this study, we use the TCR as a barcode to track clonal sharing and dynamics and observed a positive association between intra-tumoral T cell repertoire clonality and pathologic tumor regression at surgery. Although we did not observe significant global changes in clonality of the peripheral TCR repertoire throughout the 4 weeks of treatment, we determined that the most significant parameter that differentiates MPRs from non-MPRs is the clonal space occupied by the most frequent, i.e. top 1% frequency-ranked, ITCs, which demonstrated systematic perturbations in frequency in the periphery upon PD-1 blockade. More interestingly, our results showed that the top 1% ITCs were observed to be highly shared in both peripheral blood and normal lung tissue from the same patient. Furthermore, the level of clonal sharing of ITCs with blood and normal lung was significantly higher in MPR patients relative to non-MPR patients, whereas non-MPRs had more tumor-resident only ITCs, consistent with the notion that intrinsic tumor-resident T cell repertoire may likely to be exhausted with low tumor reactivity and that the T cell response to checkpoint blockade may derive from re-invigorated T cells that recently entered the tumor (23). Whereas the observation that non-MPRs have more clones that are restricted in the tumor bed implicates potential deficiency in replenishment by the peripheral T cell repertoire.

We additionally systematically characterized the dynamic pattern of ITCs in longitudinal blood. We found that significant dynamic changes in frequency of shared peripheral clones, regardless of their dynamic nature (contraction or expansion), associated with increased tumor infiltration, suggesting an active compartmental exchange of ITCs induced by neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade. Notably, peripherally expanded ITCs at week 2–4 from initiation of anti-PD-1 preferentially occupy a greater clonal space in the tumor bed of MPRs relative to non-MPRs. This observation highlights the importance of effective peripheral activation in promoting pathologic response. On the contrary, we observed that non-MPR tumors do not successfully traffic top 1% ITCs to the tumor bed, possibly due to an intrinsically more exhausted, less migratory T cell repertoire. These clones, when trapped in the tumor, could experience inhibited reinvigoration upon PD-1 blockade owing to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Therefore, detection of tumor infiltrating clones’ expansion in the peripheral blood may be an early biological correlate of anti-tumor T cell recognition and the peripheral blood may be a valuable compartment for monitoring early T cell responses to PD-1 blockade.

Supporting the notion that dynamics of shared clones are relevant to outcomes of PD-1 blockade, we demonstrated that expanded clonotypes in a patient with a complete pathologic response exhibited extremely high intraclonal PD-1 positivity, in contrast to a patient with no pathologic response, whose expanded clonotypes exhibited very low frequencies of PD-1 positivity. While anti-PD-1 has been reported to reinvigorate peripheral T cell clones that are also present in the tumor (24), our study further suggests that anti-PD-1 may induce an exchange of reinvigorated effector PD1+ T cells between the periphery and tumor, where they contribute to tumor regression. We recently showed that in Stage 4 NSCLC treated with anti-PD-1, general expansion in the blood of all clones found in pre-treatment tumors correlated with radiographic response and clearance of circulating tumor DNA (14). Here we show in the neoadjuvant setting that peripheral expansion of the most frequent ITCs (top 1% frequency) correlates much more closely with the pathologic response at the time of resection.

Although a limited number of patients has been included in our analysis, we performed an in-depth integration of the intra-tumoral anti-tumor repertoire and peripheral T cell repertoire. Larger cohorts are warranted to evaluate these features as predictive markers for response to neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade and relapse-free survival. However, we acknowledge that the median duration of recurrence-free survival has not been reached in this cohort and we are therefore unable to assess the association of TCR dynamics with survival. Additionally, while our approach utilizing TCR β chain sequencing is a common approach owing to 1) greater diversity of the β chain relative to the α chain, 2) stricter allelic exclusion of the β locus, and 3) technical ease of performing TCRseq on the β chain, we recognize that single cell paired αβ sequencing approaches should be employed in future studies aimed at determining the antigen specificity or function of these T cells. Similarly, a limitation of our study is that we did not differentiate between CD4+ and CD8+ T cell clones. While traditionally, CD8+ T cell infiltration has been associated with improved prognosis in untreated/pre-treatment tumor specimens, it is important to note that our specimens were obtained after neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade and the association of CD4+ vs. CD8+ T cell infiltration with pathologic response or clinical outcome has not been systematically evaluated in this setting. To that end, ascertaining the CD4 vs. CD8 identity of these T cells would also be useful in determining function in future studies. Correlation with ‘Immune-Related Pathologic Response Criteria’ (irPRC) (25), a newly proposed pathologic assessment of residual tumor in immunotherapy, should also be explored if validated as a surrogate for recurrence-free and overall survival. Efforts to extrapolate the current findings to patients with metastatic disease should be met with caution, as we are specifically evaluating tumor-infiltrating T cells after PD-1 blockade in patients with resectable disease. However, our results have important implications for establishment of predictive biomarkers through liquid biopsy approaches. In conclusion, our study shows that TCR profiling holds promise for monitoring anti-tumor responses in the periphery and will spur future development of biomarkers to predict response to immunotherapy and to guide what additional therapies may be warranted after surgical resection.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade has emerged as a promising treatment for resectable NSCLC and is being tested in at least 10 cancer types. It will be critical to investigate mechanisms of action and identify novel biomarkers for robust antitumor immune responses. Here, we used matched tumor, normal lung tissue, and longitudinal peripheral blood samples to examine the quantitative and qualitative changes in the T cell repertoire in NSCLC patients receiving neoadjuvant anti-PD-1. Our results add to the growing body of evidence that PD-1 blockade can boost antitumor immune responses by re-invigorating peripheral T cells to enter the tumor. Our results indicate that the periphery may be a previously underappreciated compartment for anti-tumor T cells that could be exploited in biomarker approaches for monitoring the response to immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the patients and their families for participation in this study, as well as Chanice Barkley, Iiasha Beadles, and members of our respective research and administrative teams who contributed to this study.

Financial Support

K.N. S. and H.Y.C. were funded by The Lung Cancer Foundation of America and the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Foundation. H.J. was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01 HG009518. F.H. was funded by NIH R01 CA203891-01A1. K.N. S., H. G., P. F., and J.R.B. were funded by SU2C/AACR (SU2C-AACR-DT1012). K.N.S, J.W. S., J. Z., and D.M. P. were funded by the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research. V. A. was funded by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group- American College of Radiology Imaging Network, MacMillan Foundation, and LUNGevity Foundation. V.E.V. was funded by US National Institutes of Health grants CA121113, CA180950, the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and the Commonwealth Foundation. J.M. T. was funded by National Cancer Institute R01 CA142779; T.R.C. was funded by NIH T32 CA193145. This research was funded in part through the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, Bloomberg Philanthropies, NIH Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008747, NIH Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748, NIH/NCI R01 CA056821, the Swim Across America, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and Virginia B. Squiers Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

J.M.T. receives research funding from BMS, and is a consultant/advisory board member for Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Merck, and MedImmune/AstraZeneca. J. C. is a consultant for AstraZeneca, BMS, and Genentech and received research funding from AstraZeneca, BMS, Genentech, and Merck. T. M. is a consultant for Leap Therapeutics, Immunos Therapeutics and Pfizer, and co-founder of Imvaq therapeutics; has equity in Imvaq therapeutics; reports grants from BMS, Surface Oncology, Kyn Therapeutics, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Peregrine Pharmeceuticals, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Leap Therapeutics and Aprea; is inventor on patent applications related to work on oncolytic viral therapy, alphavirus-based vaccines, neo-antigen modeling, CD40, GITR, OX40, PD-1 and CTLA-4. J.N. receives research funding from Merck and AstraZeneca, is a consultant/advisory board member for BMS, Roche/Genentech, and AstraZeneca, and has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and BMS. V.A. receives research funding from BMS. M.D.H. has received research funding from BMS; is a paid consultant to Merck, BMS, AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Janssen, Nektar, Syndax, Mirati, and Shattuck Lab; has received travel support/honoraria from AstraZeneca and BMS; and a patent has been filed by MSK related to the use of tumor mutation burden to predict response to immunotherapy (PCT/US2015/062208), which has received licensing fees from PGDx. P.M.F receives research funding from AZ, BMS, Corvus, Kyowa, and Novartis and is a consultant/advisory board member for Abbvie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer, EMD Serono, Iniviata, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, and Novartis. J.R.B receives research funding (to institution) from BMS, Merck, AstraZeneca, and is on consulting/advisory boards of BMS (uncompensated), Merck and Genentech. D.M.P. reports grant and patent royalties through institution from BMS, grant from Compugen, stock from Trieza Therapeutics and Dracen Pharmaceuticals, and founder equity from Potenza; being consultant for Aduro Biotech, Amgen, Astra Zeneca (Medimmune/Amplimmune), Bayer, DNAtrix, Dynavax Technologies Corporation, Ervaxx, FLX Bio, Rock Springs Capital, Janssen, Merck, Tizona, and Immunomic- Therapeutics; being on the scientific advisory board of Five Prime Therapeutics, Camden Nexus II, WindMil; being on the board of director for Dracen Pharmaceuticals. V.E.V. is a founder of Personal Genome Diagnostics, a member of its Scientific Advisory Board and Board of Directors, and owns Personal Genome Diagnostics stock, which are subject to certain restrictions under university policy. V.E.V. is an advisor to Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Within the last five years, V.E.V. has been an advisor to Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Diagnostics, and Ignyta. K.N.S. has received travel support/honoraria from Neon Therapeutics and Illumina. The terms of these arrangements are managed by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Gong J, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Reddi S, Salgia R. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provencio-Pulla M, Nadal-Alforja E, Cobo M, Insa A, Costa Rivas M, Majem M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemo/immunotherapy for the treatment of stages IIIA resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A phase II multicenter exploratory study—NADIM study-SLCG. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018;36:8521- [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, Anagnostou V, Cottrell TR, Hellmann MD, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in Resectable Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2018;378:1976–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittendorf E, Barrios C, Harbeck N, Miles D, Saji S, Zhang H, et al. Abstract OT2-07-03: IMpassion031: A phase III study comparing neoadjuvant atezolizumab vs placebo in combination with nab-paclitaxel–based chemotherapy in early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Cancer Research 2018;78:OT2–07 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Felip E, Broderick S, Girard N, Awad MM, et al. Checkmate 816: A phase 3, randomized, open-label trial of nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs platinum-doublet chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for early-stage NSCLC. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2017;35:TPS8577–TPS [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid P, Cortes J, Bergh JCS, Pusztai L, Denkert C, Verma S, et al. KEYNOTE-522: Phase III study of pembrolizumab (pembro) + chemotherapy (chemo) vs placebo + chemo as neoadjuvant therapy followed by pembro vs placebo as adjuvant therapy for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018;36:TPS602–TPS [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nature reviews Cancer 2016;16:275–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taube JM, Klein A, Brahmer JR, Xu H, Pan X, Kim JH, et al. Association of PD-1, PD-1 Ligands, and Other Features of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment with Response to Anti–PD-1 Therapy. Clinical Cancer Research 2014;20:5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014;515:568–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen P-L, Roh W, Reuben A, Cooper ZA, Spencer CN, Prieto PA, et al. Analysis of Immune Signatures in Longitudinal Tumor Samples Yields Insight into Biomarkers of Response and Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Discovery 2016;6:827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pagès C, et al. Type, Density, and Location of Immune Cells Within Human Colorectal Tumors Predict Clinical Outcome. Science 2006;313:1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribas A, Robert C, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Joshua AM, Hwu W-J, et al. Association of response to programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) blockade with pembrolizumab (MK-3475) with an interferon-inflammatory immune gene signature. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015;33:3001- [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giraldo NA, Nguyen P, Engle EL, Kaunitz GJ, Cottrell TR, Berry S, et al. Multidimensional, quantitative assessment of PD-1/PD-L1 expression in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma and association with response to pembrolizumab. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2018;6:99- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anagnostou V, Forde PM, White JR, Niknafs N, Hruban C, Naidoo J, et al. Dynamics of tumor and immune responses during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 2018:canres.1127.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamphorst AO, Pillai RN, Yang S, Nasti TH, Akondy RS, Wieland A, et al. Proliferation of PD-1+ CD8 T cells in peripheral blood after PD-1-targeted therapy in lung cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:4993–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robins HS, Campregher PV, Srivastava SK, Wacher A, Turtle CJ, Kahsai O, et al. Comprehensive assessment of T-cell receptor beta-chain diversity in alphabeta T cells. Blood 2009;114:4099–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi Q, Liu Y, Cheng Y, Glanville J, Zhang D, Lee JY, et al. Diversity and clonal selection in the human T-cell repertoire. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014;111:13139–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danilova L, Anagnostou V, Caushi JX, Sidhom J-W, Guo H, Chan HY, et al. The Mutation-Associated Neoantigen Functional Expansion of Specific T cells (MANAFEST) assay: a sensitive platform for monitoring antitumor immunity. Cancer immunology research 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cha E, Klinger M, Hou Y, Cummings C, Ribas A, Faham M, et al. Improved Survival with T Cell Clonotype Stability After Anti–CTLA-4 Treatment in Cancer Patients. Science Translational Medicine 2014;6:238ra70–ra70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheper W, Kelderman S, Fanchi LF, Linnemann C, Bendle G, de Rooij MAJ, et al. Low and variable tumor reactivity of the intratumoral TCR repertoire in human cancers. Nat Med 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein JE, Soni A, Danilova L, Cottrell TR, Gajewski TF, Hodi FS, et al. Major pathologic response on biopsy (MPRbx) in patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti-PD-1: evidence for an early, on-therapy biomarker of response. Annals of Oncology 2019;30:589–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang AC, Orlowski RJ, Xu X, Mick R, George SM, Yan PK, et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat Med 2019;25:454–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yost KE, Satpathy AT, Wells DK, Qi Y, Wang C, Kageyama R, et al. Clonal replacement of tumor-specific T cells following PD-1 blockade. Nature Medicine 2019;25:1251–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang AC, Postow MA, Orlowski RJ, Mick R, Bengsch B, Manne S, et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 2017;545:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cottrell TR, Thompson ED, Forde PM, Stein JE, Duffield AS, Anagnostou V, et al. Pathologic features of response to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 in resected non-small-cell lung carcinoma: a proposal for quantitative immune-related pathologic response criteria (irPRC). Annals of Oncology 2018;29:1853–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.