Abstract

Purpose:

Adavosertib (AZD1775), an inhibitor of WEE1 kinase, potentiates replicative stress induced by oncogenes or chemotherapy. Anti-tumor activity of adavosertib has been demonstrated in preclinical models of pediatric cancer. This phase I trial was performed to define dose-limiting toxicities (DLT), recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) and pharmacokinetics of adavosertib in combination with irinotecan in children and adolescents with relapsed or refractory solid tumors or primary central nervous system tumors.

Methods:

Using a 3+3 escalation design, 5 dose cohorts of the combination of adavosertib and irinotecan (50/70; 65/70; 65/90; 85/90; 110/90 mg/m2/day), delivered on days 1-5 of a 21-day cycle were studied. Pharmacokinetics and analysis of peripheral blood γH2AX was performed.

Results:

Thirty-seven patients were enrolled; twenty-seven were evaluable. The median (range) age was 14 (2-20) years. Twenty-five (93%) received prior chemotherapy (median, 3 regimens) and 21 (78%) received prior radiation therapy. Eleven patients had a primary CNS malignancy. Common toxicities were hematologic and gastrointestinal. Two patients receiving adavosertib (110 mg/m2) in combination with irinotecan (90 mg/m2) experienced dose limiting grade 3 dehydration. A patient with Ewing Sarcoma had a confirmed partial response and 2 patients (ependymoma and neuroblastoma) had prolonged stable disease (≥ 6 cycles). Pharmacokinetics of adavosertib were variable but generally dose proportional and clearance was lower in younger patients.

Conclusion:

Adavosertib (85 mg/m2) in combination with irinotecan (90 mg/m2) administered orally for 5 days was the maximum tolerated dose in children and adolescents with solid and CNS tumors.

Keywords: Wee1, Adavosertib, AZD1775, irinotecan, Pediatric Cancer

Introduction

Wee1 is a tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates and inhibits CDK1, affecting proper coordination of DNA replication as well as entry into mitosis. In the presence of a DNA damage repair deficiency (such as TP53 or BRCA mutation) or replication stress (by chemotherapy, radiation, oncogenes) CDK1 activity is restrained by the checkpoint kinases CHK1 and WEE1 (1,2). These checkpoints allow for repair of DNA prior to mitosis and tolerance of replication stress, thereby maintaining tumor cell viability. Inhibition of CHK1 or WEE1 leads to replication fork collapse or mitotic catastrophe, generation of single, then double-strand DNA breaks and ultimately cellular death. In the presence of single stranded DNA or DNA damage, there is induction of phosphorylated H2A (γH2AX), a histone family member. Adavosertib (AZD1775) is a highly selective, ATP competitive, small-molecule inhibitor of WEE1 kinase and sensitizes tumor cells to cytotoxic agents and replication stress, including tumors with high levels of the MYCN oncogene (3,4). Preclinical studies have shown anti-tumor activity of adavosertib as a single agent and in combination therapy in several carcinomas and the pediatric solid tumors including neuroblastoma (4), rhabdomyosarcoma (5), diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (6) and medulloblastoma (7).

Adavosertib has been evaluated in adult solid tumor Phase 1 studies as monotherapy and in combination with gemcitabine, cisplatin or carboplatin (8,9). No maximum tolerated dose was reached with monotherapy adavosertib. In the combination regimens the most common adverse events included fatigue, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea and hematologic toxicity. Ten percent of 176 evaluable patients had a PR (4% confirmed) and 53% had stable disease of at least 6 weeks (8). The greatest activity within these studies was shown in BRCA mutated cancers (9) and those with mutant TP53 (8,10). A Phase 2 study of adavosertib in combination with carboplatin confirmed that Wee1 inhibition enhanced efficacy in patients with TP53 mutant ovarian cancers refractory to prior platinum therapy (11). A glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) phase 0 study demonstrated the central nervous system tumor penetration of adavosertib (12). Therefore, adavosertib is being developed for the treatment of patients with advanced solid tumors and CNS malignancies with genetic deficiencies in DNA repair mechanisms.

The rationale for combining adavosertib with irinotecan for children with solid tumors was multi-factorial. Irinotecan induces replication stress and adavosertib’s mechanism of action involves replication arrest over-ride providing mechanistic support for this combination (2). Adavosertib in combination with irinotecan demonstrates synergistic growth inhibition in preclinical models (4,5). The five-day dosing regimen of irinotecan delivered every 21 days used in childhood cancer allows for serial dosing and exposure of adavosertib. In addition, irinotecan induces down regulation of another major cell cycle checkpoint kinase, CHK1 (13) whose dual inhibition with WEE1 is synergistic in preclinical models (4,14).

We report the phase 1 results of ADVL1312, a Children’s Oncology Group multi-institutional dose escalation study of adavosertib in combination with irinotecan for children with relapsed or refractory solid and CNS tumors. The primary objectives were to estimate the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) or recommended Phase 2 dose (RP2D) of adavosertib administered on days 1 through 5 every 21 days in combination with oral irinotecan, to define and describe the toxicities of adavosertib in combination with oral irinotecan administered on this schedule and to characterize the pharmacokinetics of adavosertib. Secondary objectives included assessment of objective anti-tumor activity within the confines of a phase 1 trial, utilization of phosphorylation of histone family protein H2AX as a biomarker of induction of DNA damage and checkpoint over-ride in peripheral blood cells and assessment of MYCN by immunohistochemistry in archival tumor samples from enrolled patients. This is the first report of adavosertib in children and in combination with a topoisomerase inhibitor in cancer.

Patients and Methods:

Patient eligibility

Patients age 1 to 21 years with measurable or evaluable solid tumors, including central nervous system (CNS) tumors, refractory to standard treatment and for whom no known curative therapy existed, were eligible. Histologic verification of malignancy, at diagnosis or recurrence, was required with the exception of diffuse intrinsic brainstem tumors (DIPG). Other eligibility criteria included a Lansky or Karnofsky performance score of ≥ 50; recovery from the acute toxic effects of prior therapy including resolution of therapy related neurologic effects resolved to grade ≤ 2; adequate bone marrow function [absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 1,000/mm3 and platelet count ≥ 100,000/mm3], renal function (normal serum creatinine for age and gender, or creatinine clearance ≥ 70 mL/min/1.73 m2), liver function [bilirubin 1.5 times upper limit of normal for age, ALT < 110 U/L, serum albumin ≥ 2 g/dL], QTc ≤ 480 msec, and ability to swallow capsules. Patients receiving drugs known to be moderate or strong inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4 or CYP3A4 substrates with a narrow therapeutic range, were not eligible.

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Cancer Therapeutics Evaluation Program (CTEP) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and institutional review boards of all participating institutions. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent and child assent, when appropriate, were obtained from all participants and/or parents or legal guardians.

Protocol therapy administration and study design

Adavosertib (10, 25 or 100 mg capsules) was supplied by Astra Zeneca and distributed by CTEP, NCI. Adavosertib was administered orally one hour after oral irinotecan for 5 days every 21 days. Cefixime prophylaxis for irinotecan related diarrhea was required. Protocol therapy could continue until participants experienced disease progression, met discontinuation of protocol therapy criteria or a maximum of 18 cycles. Dose escalation proceeded step-wise for both adavosertib and irinotecan using a 3 + 3 design. Dose levels (DL) were adavosertib 50 mg/m2/day (DL1), 65 mg/m2/day (DL 2 and 3), 85 mg/m2/day (DL4) and 110 mg/m2/day (DL5) in combination with irinotecan 70 mg/m2/day (DL 1 and 2), or 90 mg/m2/day (DL3, 4, and 5). Intra-patient dose escalation was not permitted. Once the MTD or RP2D was defined, up to 6 additional patients with relapsed/refractory solid tumors were enrolled to acquire toxicity and PK data in at least 6 patients less than or equal to 12 years old.

Toxicities were graded according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4. The DLT observation period for dose-escalation and determination of MTD/RP2D was the first cycle of protocol therapy and included toxicity that was possibly, probably or definitely attributable adavosertib in combination with irinotecan. Hematologic dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was defined as grade 4 neutropenia that persisted for greater than 7 days, platelet counts less than 20,000/mm3 on two separate measurements at least 48 hours apart or requiring two or more platelet transfusions within 7 days. Non-hematological DLTs were defined as any grade 3 or 4 non-hematological toxicity possibly, probably or definitely attributable to protocol therapy, with the specific exclusion of grade 3 nausea and vomiting of < 3 days in duration; grade 3 liver enzyme elevation < 7 days duration; grade 3 fever; grade 3 infection; grade 3 hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, or hypomagnesemia responsive to oral supplementation; grade 3 diarrhea ≤ 3 days duration despite maximal supportive care; grade 3 mucositis or stomatitis ≤ 3 days duration; allergic reactions; any toxicity that required treatment interruption for > 14 days was considered dose limiting. Subjects who experienced a DLT during cycle 1 as well as subjects without DLT who received 100% of the prescribed protocol therapy and completed toxicity monitoring, were evaluable for determination of the maximum tolerated dose. The MTD was defined as the dose level in which fewer than 1/3 of patients experienced a DLT.

Pretreatment evaluations included a history and a physical exam; routine laboratory evaluations, (complete blood count, urinalysis, electrolytes, renal and liver function) and electrocardiogram (EKG). A history, physical examination and laboratory evaluations were obtained weekly during the first cycle, then before each subsequent cycle. Disease evaluations were obtained at baseline, the end of the first cycle, every other cycle x 2 and then every 3 cycles. Disease response for solid tumors was assessed according to the revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v1.1) and neuroblastoma was assessed using bone marrow biopsies, anatomic imaging for measureable disease, and MIBG scintigraphy for evaluable MIBG-avid tumors. Curie scoring was used to assess response in patients with neuroblastoma who had evaluable disease by MIBG scintigraphy without measureable disease. In patients with primary CNS disease tumor response was evaluated by MRI; complete response (CR) was complete resolution of all lesions, partial response (PR) for CNS tumor was ≥50% decrease in the sum of the products of the two perpendicular diameters of all target lesions. Stable Disease (SD) was neither sufficient decrease in the sum of the products of the two perpendicular diameters of all target lesions to qualify for PR, nor sufficient increase in a single target lesion to qualify for PD. Progressive Disease (PD) was defined as 25% or more increase in the sum of the products of the perpendicular diameters of the target lesions. For patients with objective response confirmatory imaging was performed at least 3 weeks after initial response was recorded. Central imaging review was completed for all participants who had institutional assigned objective response or had stable disease for six or more cycles. Best overall response is reported for each patient who had at least one radiographic assessment after initiation of protocol therapy or clinically progressive disease.

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples (2-3 mL) were collected in dipotassium EDTA tubes during Cycle 1: Day 1 (pre-dose, 1 hr, 2 hr, 4 hr, 6 hr, 8 hr and 24 hours after dose), Day 4 (pre- dose), Day 5 (pre-dose, 1 hr, 2 hr, 4 hr, 6 hr, and 8 hr after dose) of Cycle 1. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation (10 min x 1500g) in a refrigerated centrifuge and immediately frozen. Adavosertib plasma concentrations were measured by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry, as previously described (8,15). Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using non-compartmental analysis (Phoenix WinNonlin 6.4; Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA) (16).

Pharmacodynamics and correlative biology

For γH2AX analysis, blood (1 mL) was processed using Smart Tubes™ (Thermo Fisher) at baseline, on day 1 immediately prior to adavosertib (one hour after irinotecan) and four hours after adavosertib, as well as 24 hours after chemotherapy, prior to irinotecan on day 2. Percent positive γH2AX peripheral blood cells was determined by flow cytometry and described as fold-change over baseline for each patient (17). In brief, processed cells were fixed in 90% methanol, washed, then resuspended in staining buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS) with TruStain FcX™ and FITC-conjugated anti-γH2AX Ser-139 antibody (1:100; clone JBW301, EMD Millipore). After one hour, cells were washed with PBS, and resuspended in staining buffer with 2.5 ug/mL propidium iodide (PI) and data were acquired on CytoflexS. FlowJo software was used to analyze data and identify dual PI/FITC positive cells.

MYCN immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on archival tumor and control formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue slides using the N-Myc antibody (Santa Cruz, SC-53993) according to protocol at a 1:100 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed with E1 retrieval solution for 20 min and staining was performed on a Bond RXm automated staining system using Bond Refine polymer staining kit (Leica Biosystems). Corresponding H&E and MYCN IHC slides were scored by a pediatric solid tumor pathologist for intensity and % positivity.

Results

Dose Escalation and Determination of MTD

Between March 2014 and October 2016, thirty-seven subjects enrolled, all of whom were eligible. Ten subjects were not evaluable for determination of the MTD for the following reasons: 2 subjects developed rapid clinical progression of disease, 6 did not receive 100% of protocol therapy (due to vomiting any amount of the prescribed chemotherapy, maximum 2 doses) and 2 subjects refused completion of all prescribed adavosertib and irinotecan during cycle 1 for reasons other than tolerability. Since no patient in this group experienced dose limiting toxicity, these patients were replaced per protocol. The characteristics of the 27 patients evaluable for determination of the MTD/RP2D are presented in Table 1 and of all 37 enrolled, in Table S1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects evaluable for toxicity (n=27)

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 14 |

| Range | 2-20 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 14 (52) |

| Female | 13 (48) |

| Race | |

| White | 19 (70.3) |

| Asian | 2 (7.4) |

| Black or African American | 3 (11.1) |

| Unknown | 3 (11.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 24 (89) |

| Hispanic | 3 (11) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Carcinoma | 4 (14.8) |

| Ependymoma | 4 (14.8) |

| Ewing sarcoma | 4 (14.8) |

| Malignant glioma | 7 (25.9) |

| Neuroblastoma | 2 (7.4) |

| Osteosarcoma | 3 (11.1) |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 2 (7.4) |

| Wilms tumor | 1 (3.7) |

| Prior Therapy | |

| Chemotherapy Regimens | (n=25) |

| Median | 3 |

| Range | 1-11 |

| Radiation Therapy | (n=21) |

| Median | 1 |

| Range | 1-3 |

Dose escalation and DLTs are presented in Table 2. At DL5, a patient with a disseminated epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma had dose limiting grade 3 dehydration. Dose level 5 expanded to 3 additional patients, and a patient with a synovial cell sarcoma experienced DLT (grade 3 dehydration, hypotension and diarrhea). At DL4 there were no DLTs in twelve evaluable patients (6 in dose escalation and 6 in PK expansion), establishing irinotecan 90 mg/m2 and adavosertib 85 mg/m2, administered orally daily for 5 days as the pediatric MTD and recommended phase 2 dose.

Table 2.

Dose Escalation and DLT summary

| Dose level |

Irinotecan Adavosertib mg/m2 |

Number of patients enrolled |

Number of patients evaluable for DLT |

Number of patients with DLT |

Type of DLT (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | 50 | 4 | 3 | 0 | |

| 2 | 70 | 65 | 5 | 3 | 0 | |

| 3 | 90 | 65 | 4 | 3 | 0 | |

| 4 | 90 | 85 | 10 | 6 | 0 | |

| 4 (PK) | 90 | 85 | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| 5 | 90 | 110 | 8 | 6 | 2 | Dehydration (2), Diarrhea (1), Hypotension (1) |

Cycle 1 hematologic (all) and non-hematologic toxicities (in ≥ 10% of all evaluable patients) are shown in Table 3, if there was at least one grade 3 event (Supplemental Table 2 for all grades). Of note, while dehydration was the dose limiting toxicity, this AE was not included in Table 3 because it occurred in 2/27 participants, and did not meet the threshold criteria of ≥ 10%. The most common toxicity was diarrhea in 89% of subjects (11% grade ≥ 3), despite Cefixime prophylaxis for irinotecan related diarrhea.

Table 3.

Most Common (≧ 10% in Non-Hematologic) Toxicities Summary (maximum grade shown), in Cycle 1.

| Dose Level and Toxicity Grade, No. (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Dose Levels (n=27) | Dose level 1 (n=3) | Dose level 2 (n=3) | Dose level 3 (n=3) | Dose level 4 (n=12) | Dose level 5 (n=6) | |||||||

| Toxicity Type | All grades | ≧Grade 3 | All grades | ≧Grade 3 | All grades | ≧Grade 3 | All grades | ≧Grade 3 | All grades | ≧Grade 3 | All grades | ≧Grade 3 |

| GI TOXICITY | ||||||||||||

| Diarrhea | 24 (89) | 3 (11) | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 9 (75) | 6 (100) | 2 (33) | |||

| Vomiting | 13 (48) | 1 (4) | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 4 (33) | 4 (67) | 1 (17) | ||||

| Nausea | 12 (44) | 1 (4) | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 4 (33) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | ||||

| BONE MARROW TOXICITY | ||||||||||||

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 18 (67) | 6 (22) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 9 (75) | 5 (42) | 3 (50) | |||

| Anemia | 15 (56) | 1 (4) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 8 (67) | 1 (8) | 3 (50) | ||||

| White blood cell decreased | 12 (44) | 3 (11) | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 5 (42) | 2 (17) | 3 (50) | ||||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 9 (33) | 6 (22) | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 5 (42) | 2 (17) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | ||||

| OTHER | ||||||||||||

| Hypotension | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | ||||||||

| INVESTIGATIONS | ||||||||||||

| Hypophosphatemia | 7 (26) | 1 (4) | 2 (67) | 4 (33) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | ||||||

| Hypokalemia | 6 (22) | 2 (7) | 3 (25) | 1 (8) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | ||||||

Pharmacokinetics

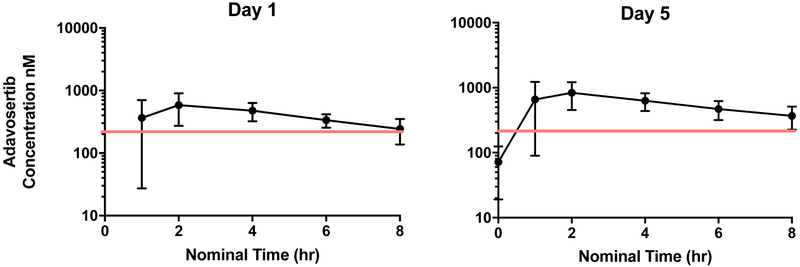

Adavosertib pharmacokinetics, presented in Table 4, demonstrated substantial interpatient variability. Maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the concentration x time curve (AUC) appeared to increase with dose. Plasma concentration-time curves for patients treated at the RP2D are shown in Figure 1. The overall median oral clearance (Cl/F) was 32.5 (range 14.2 - 1130 L/hr/m2) and was similar in females and males (33.0 L/h/m2 versus 27.8 L/h/m2; P=0.22). However, children younger than age 12 had lower median Cl/F compared to children age 12 or older (21.4 L/h/m2 versus 35.6 L/h/m2; P=0.03). Following 5 days of daily administration, modest accumulation of adavosertib was observed based on comparison of the day 1 versus day 5 AUC0-8h. The median (range) accumulation ratio was 1.40 (0.62 – 5.79).

Table 4.

Adavosertib pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters, median (range)

| Pharmacokinetic Parameter |

Dose Level 1 50mg/m2 | Dose Level 2 65mg/m2 | Dose Level 3 65mg/m2 | Dose Level 4 85mg/m2 | Dose Level 5 110mg/m2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 (N=4) | Day 5 (N=4) | Day 1 (N=4) | Day 5 (N=5 ) | Day 1 (N=4 ) | Day 5 (N=3 ) | Day 1 (N=12 ) | Day 5 (N=12 ) | Day 1 (N=5) | Day 5 (N=2 ) | |

| Tmax (h) | 2.0 (2.0 – 8.0) |

2.0 (2.0 – 2.1) |

1.5 (1.0 – 3.8) |

3.9 (2.0 – 4.0) |

3.0 (2.0 – 4.0) |

2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) |

2.1 (2.0 – 8.0) |

2.0 (1.0 – 6.0) |

2.0 (2.0 – 4.0) |

4.0 (2.0 – 5.9) |

| Cmax (nM) | 500 (208–567) |

485 (280–809) |

584 (61–815) |

687 (360–747) |

471 (312–905) |

1288 (779–1430) |

524 (328–1151) |

822 (451–1712) |

901 (54–1069) |

354 (89 – 619) |

| Half-life (h) | 4.6 (3.6 – 6.0) |

5.8 (3.9 – 6.5) |

5.4 (4.5 – 7.5) |

4.7 (4.0 – 7.1) |

4.4 (1.3 – 6.9) |

|||||

| AUC0-8h (h*nM) | 2100 (776 – 2181) |

2185 (1312 –3112) |

2338 (329 – 3511) |

3004 (1905 –4064) |

2382 (1281 –4605) |

5321 (3798 –6301) |

2745 (1381– 5050) |

3843 (2706 –8322) |

3743 (266 – 5236) |

1658 (355– 2960) |

| Accumulation (AUC Day5/Day1) | 1.4 (0.6 – 1.7) |

1.4a (1.0 – 5.8) |

1.8 (1.4 – 2.0) |

1.4 (1.2 – 2.0) |

1.1 (0.9 – 1.3) |

|||||

| Cl/F (L/h) | 38 (31 – 170) |

49 (27 – 247) |

39 (26– 76) |

45 (23 – 114) |

62 (38 -1198) |

|||||

| Cl/m2 (L/h/m2) | 32 (17 – 80) |

42 (21 – 129) |

29 (17 – 59) |

33 (14 – 63) |

36 (21 -1130) |

|||||

| V/F (L) | 271 (174–1145) |

348 (211-2205) |

298 (171 –822) |

320 (153 – 673) |

386 (130–4770) |

|||||

| V/m2 (L/m2) | 185 (150 – 540) |

269 (181 – 1148) |

222 (112 – 642) |

209 (95 – 645) |

251 (70 – 4500) |

|||||

AUC ratio at Dose Level 2, N=4

Figure 1:

Median plasma concentration curves of adavosertib on day 1 and 5 (N = 12) at the recommended phase 2 dose of Irinotecan 90 mg/m2 and adavosertib 85 mg/m2. Blood samples were collected pre-dose and during cycle 1 at 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8 hrs after the first dose on day 1 and last dose on day 5. The adavosertib concentrations met the goal Wee1 target engagement concentration of 240 nM (red line).

Antitumor Activity

Any patient who received at least one dose of irinotecan and adavosertib and was observed for at least one cycle of therapy, or had progressive disease, was evaluable for response. Thirty-six subjects were evaluable for response, completing an average of 3 (range 1-18) cycles of protocol therapy. One subject with Ewing Sarcoma had a confirmed partial response for 5 cycles. A patient with relapsed ependymoma completed the maximum allowable therapy (18 cycles) with a best response of stable disease; a patient with high risk neuroblastoma with measurable, MIBG avid and marrow disease at baseline completed 11 cycles with a best response of stable disease.

Pharmacodynamics and Correlative Biology

Fold change of PBC γH2AX protein expression relative to baseline was determined in 14 patients and descriptively presented in Table 5, with γH2AX induction defined as a fold change greater than 1 (bold). It was hypothesized that γH2AX induction after irinotecan and adavosertib would increase with dose level. There was induction of γH2AX after treatment with irinotecan alone in 9/14 (64%) and adavosertib in combination with irinotecan in 10/14 (71%) of patients. At DL5, the mean fold change in induction of γH2AX after the combination of irinotecan and adavosertib compared to baseline was 4.7 (95% CI: 1.1, 19.1; p=0.03).

Table 5: Peripheral blood cell γH2AX fold induction.

on day 1, one hour after Irinotecan (column 4), and 4 hours after Irinotecan and adavosertib (column 5) and day 2, approximately 24 hours after chemotherapy (column 6). Bolded numbers indicate fold induction > 1 over baseline.

| DL Patient ID |

adavosertib Day 1 Cmax (nM) |

Day 1 Pre-chemo baseline |

Day 1 fold change IRN alone |

Day 1 fold change IRN & adavosertib |

Day 2 fold change IRN & adavosertib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL1-1 | 439 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

| DL1-2 | 567 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| DL1-3 | 208 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 9.3 | ND |

| DL2-1 | 435 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| DL2-2 | 733 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| DL2-3 * | ND | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| DL3-1 | 380 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| DL3-2 | ND | 1.0 | 32.0 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| DL4-1 | 1050 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 2.7 |

| DL4-2 | 681 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| DL4-3 | 433 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| DL5-1 ** | 54 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| DL5-2 | 737 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 5.8 | 7.6 |

| DL5-3 | 1069 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 23.4 | 4.7 |

patient vomited adavosertib.

adavosertib maximum plasma concentration is below goal target concentration of 240 nM.

Archival tissue sections were available for 23 patients. Protein expression of MYCN by immunohistochemistry was present in an anaplastic astrocytoma and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma tumor sample. Neither patient had a response or prolonged stable disease.

Discussion

This is the first clinical trial of adavosertib in pediatric patients, and the first report of adavosertib in combination with a topoisomerase inhibitor in cancer. The MTD and RP2D of this oral regimen was adavosertib (85 mg/m2/day) in combination with the irinotecan (90 mg/m2/day) daily for five days every 21 days. The dose limiting toxicities, which occurred at DL5 (adavosertib 110 mg/m2/day in combination with irinotecan 90 mg/m2/day) included grade 3 dehydration (n=2), diarrhea (n =1) and hypotension (n=1). Adavosertib (85 mg/m2/day) is equivalent to an adult fixed dose of 147 mg/day (735 mg/cycle). In adults receiving adavosertib twice daily x 2.5 days (5 doses/cycle) in combination with cisplatin or carboplatin, the MTD of adavosertib was 200 mg/dose (1000 mg/cycle) and 225 mg/dose (1125 mg/cycle), respectively. Differences in chemotherapy regimens including known nausea and vomiting associated with using the intravenous formulation of irinotecan orally in children, schedule and population may account for the lower MTD observed in children and adolescents compared to adult studies.

In our study, the plasma maximum concentration and exposure of adavosertib had moderate to high inter-patient variability and generally increased in proportion to dose (Table 4) which also occurred in the adult studies (8,9). As noted above, the lower pediatric MTD is likely multi-factorial, however, comparison of the Cmax and AUC0-8h at the adult dose level of 225 mg, equivalent to 132 mg/m2 in an individual with BSA of 1.7 m2, suggest adavosertib might have lower oral clearance (Cl/F) in children. The high median Cmax and AUC0-8h values of 900 nM and 3743 nM●hr at the 110 mg/m2 dose level in our study compared to median Cmax and AUC0-8h values of 667 nM and 3980 nM●hr at the 225 mg dose level in adults are consistent with a lower apparent clearance in children or co-administration of irinotecan with adavosertib. However, since oral clearance was not determined in the published adult Phase 1 study (8), and adavosertib was administered with irinotecan in this study, it is difficult to directly compare this pharmacokinetic parameter. The maximum (Table 4) and median plasma concentrations of adavosertib at DL4 (figure 1) met the preclinical target of 240 nM also achieved in the adult clinical trials (8).

Prior pharmacodynamics studies to evaluate on-target inhibition of Wee1 by adavosertib and chemotherapy involved pre- and post-treatment tumor core or skin punch biopsies for inhibition of CDK1 phosphorylation or induction of γH2AX signifying enhanced DNA damage (8-10). For this study in children and adolescents, we examined peripheral blood mononuclear cell γH2AX induction by flow cytometry prior to irinotecan, prior to adavosertib (after irinotecan) and at 2 time points after the combination. There was induction of γH2AX after irinotecan alone or in combination with adavosertib in 10 of the 14 of patients (71%), and of those with induction, 80% had greater induction with the combination of irinotecan and adavosertib than with irinotecan alone (Table 5). A limitation of this analysis is that we do not have a time course of irinotecan PBC γH2AX induction alone to determine if the increased induction of γH2AX is due to the addition of adavosertib. Of interest, DL2 patient 3 (DL2-3) received irinotecan on day 1 but had emesis of the adavosertib, and no induction of γH2AX in PBCs was observed at either time point. For patient 1 of DL5 (DL5-1) γH2AX induction in PBCs was observed after irinotecan only, but not after the combination. This patient had an adavosertib Cmax of 54 nM, which is below the goal 240 nM for Wee1 target engagement concentration.

A secondary objective of this study was to assess objective anti-tumor activity within the confines of a phase 1 trial. There was one confirmed partial response observed in a patient with Ewing Sarcoma. In addition, 2 patients received ≥ 6 cycles of therapy, including one patient with ependymoma and another with neuroblastoma who completed 18 cycles and 11 cycles, respectively. None of these patient’s archival tumor samples had high levels of MYCN, and genomic analysis was not available to determine whether they have a defective DNA damage and repair pathway, which may be of interest in future studies given the prevalence of these conditions in pediatric cancer (18). The previously published Children’s Oncology Group solid tumor phase 2 trial of single agent irinotecan treated 161 patients with a 5% overall objective response rate (19).

In conclusion, the recommended phase 2 dose in children and adolescents with relapsed and/or refractory solid and CNS tumors is adavosertib 85 mg/m2/day in combination with irinotecan (90 mg/m2/day) daily for five days every 21 days. The regimen was tolerable with the proportion of grade 3 and grade 4 hematological and non-hematological adverse events and dose limiting toxicity consistent with those that could be expected from an irinotecan-containing regimen (19,20). There was suggestion of clinical activity in this heavily pre-treated relapsed and recurrent population of patients. The phase 2 expansion cohorts of adavosertib in combination with irinotecan in patients with relapsed and refractory neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma and CNS embryonal tumors or rhabdomyosarcoma are actively accruing further evaluating the potential of this combination in the treatment of children and adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Wee1 tyrosine kinase phosphorylates and inactivates cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) in response to DNA damage or replication stress. Adavosertib (AZD1775) is a first in class inhibitor of Wee1 with promising anti-tumor activity as monotherapy and in combination with chemotherapy in several adult solid tumors. This study describes the first clinical experience of adavosertib in children and is the first clinical trial to evaluate adavosertib in combination with a topoisomerase inhibitor. Determination of the recommended phase 2 dose supports the ongoing phase 2 clinical trial in children with neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, medulloblastoma and other CNS embryonal tumors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Astra Zeneca for supply of adavosertib and support of pharmacokinetic analysis; the Children’s Oncology Group Phase I Consortium Operations Team; the institutional PIs and clinical coordinators; and the patients and their families who participated on the ADVL1312 trial.

Financial support.

The research reported above is supported by the Children’s Oncology Group, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number UM1CA228823, R01 CA214912, as well as Solving Kids Cancer and the Cookies for Kids’ Cancer Foundations

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Geenen JJ, Schellens JHM. Molecular Pathways: Targeting the Protein Kinase Wee1 in Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23(16):4540–4 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobbelstein M, Sorensen CS. Exploiting replicative stress to treat cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015;14(6):405–23 doi 10.1038/nrd4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirai H, Iwasawa Y, Okada M, Arai T, Nishibata T, Kobayashi M, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of Wee1 kinase by MK-1775 selectively sensitizes p53-deficient tumor cells to DNA-damaging agents. Mol Cancer Ther 2009;8(11):2992–3000 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell MR, Levin K, Rader J, Belcastro L, Li Y, Martinez D, et al. Combination therapy targeting the Chk1 and Wee1 kinases shows therapeutic efficacy in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 2013;73(2):776–84 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart E, McEvoy J, Wang H, Chen X, Honnell V, Ocarz M, et al. Identification of Therapeutic Targets in Rhabdomyosarcoma through Integrated Genomic, Epigenomic, and Proteomic Analyses. Cancer Cell 2018;34(3):411–26 e19 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller S, Hashizume R, Yang X, Kolkowitz I, Olow AK, Phillips J, et al. Targeting Wee1 for the treatment of pediatric high-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol 2014;16(3):352–60 doi 10.1093/neuonc/not220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PS, Venkataraman S, Alimova I, Birks DK, Balakrishnan I, Cristiano B, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies the mitotic checkpoint kinase WEE1 as a novel therapeutic target in medulloblastoma. Mol Cancer 2014;13:72 doi 10.1186/1476-4598-13-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leijen S, van Geel RM, Pavlick AC, Tibes R, Rosen L, Razak AR, et al. Phase I Study Evaluating WEE1 Inhibitor AZD1775 As Monotherapy and in Combination With Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, or Carboplatin in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(36):4371–80 doi 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do K, Wilsker D, Ji J, Zlott J, Freshwater T, Kinders RJ, et al. Phase I Study of Single-Agent AZD1775 (MK-1775), a Wee1 Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients With Refractory Solid Tumors. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(30):3409–15 doi 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendez E, Rodriguez CP, Kao MC, Raju S, Diab A, Harbison RA, et al. A Phase I Clinical Trial of AZD1775 in Combination with Neoadjuvant Weekly Docetaxel and Cisplatin before Definitive Therapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24(12):2740–8 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leijen S, van Geel RM, Sonke GS, de Jong D, Rosenberg EH, Marchetti S, et al. Phase II Study of WEE1 Inhibitor AZD1775 Plus Carboplatin in Patients With TP53-Mutated Ovarian Cancer Refractory or Resistant to First-Line Therapy Within 3 Months. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(36):4354–61 doi 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanai N, Li J, Boerner J, Stark K, Wu J, Kim S, et al. Phase 0 Trial of AZD1775 in First-Recurrence Glioblastoma Patients. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24(16):3820–8 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang YW, Otterness DM, Chiang GG, Xie W, Liu YC, Mercurio F, et al. Genotoxic stress targets human Chk1 for degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mol Cell 2005;19(5):607–18 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies KD, Cable PL, Garrus JE, Sullivan FX, von Carlowitz I, Huerou YL, et al. Chk1 inhibition and Wee1 inhibition combine synergistically to impede cellular proliferation. Cancer Biol Ther 2011;12(9):788–96 doi 10.4161/cbt.12.9.17673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Fang W, Zeng W, Leijen S, Woolf EJ. Evaluation of dried blood spot (DBS) technology versus plasma analysis for the determination of MK-1775 by HILIC-MS/MS in support of clinical studies. Anal Bioanal Chem 2012;404(10):3037–48 doi 10.1007/s00216-012-6440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.M G, D P. Pharmacokinetics (ed2). Series on Drugs and the Pharmaceutical Sciences. NY: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pal S, Kozono D, Yang X, Fendler W, Fitts W, Ni J, et al. Dual HDAC and PI3K Inhibition Abrogates NFkappaB- and FOXM1-Mediated DNA Damage Response to Radiosensitize Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas. Cancer Res 2018;78(14):4007–21 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Walsh MF, Wu G, Edmonson MN, Gruber TA, Easton J, et al. Germline Mutations in Predisposition Genes in Pediatric Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373(24):2336–46 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1508054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bomgaars LR, Bernstein M, Krailo M, Kadota R, Das S, Chen Z, et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan in children with refractory solid tumors: a Children’s Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(29):4622–7 doi 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blaney S, Berg SL, Pratt C, Weitman S, Sullivan J, Luchtman-Jones L, et al. A phase I study of irinotecan in pediatric patients: a pediatric oncology group study. Clin Cancer Res 2001;7(1):32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.