Abstract

Purpose

Serous adenocarcinoma (uterine serous carcinoma – USC) is a rare and aggressive histologic subtype of endometrial cancer, with a high-rate of recurrence and poor prognosis. The adjuvant treatment for stage I patients is unclear. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of stage I USC treated exclusively with chemotherapy plus vaginal brachytherapy (VBT).

Material and methods

A systematic research using PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane library was conducted to identify full articles evaluating the efficacy of VBT in patients with stage I USC. A search in ClinicalTrials.gov was performed in order to detect ongoing or recently completed trials, and in PROSPERO for searching ongoing or recently completed systematic reviews.

Results

All studies were retrospective and 364 of evaluated patients were found. The average local control was 97.5% (range, 91-100%), the disease free-survival was 88% (range, 82-94%), the overall survival was 93% (range, 72-100%), the specific cancer survival was 89.4% (range, 84.8-94%), and the G3-G4 toxicity was 0-8%.

Conclusions

These data support the concept that in adequately selected patients, VBT alone may be a suitable radiotherapy technique in women with stage I USC who underwent surgical staging and received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Keywords: serous adenocarcinoma, endometrial cancer, brachytherapy, outcomes

Purpose

Uterine serous carcinoma (USC) is an aggressive histologic subtype of endometrial cancer, similar to serous ovarian carcinoma. Although USC represents less than 10% of all endometrial cancers, it accounts for more than 50% of relapses and deaths attributed to endometrial carcinoma [1,2,3], with an estimated 5-year overall survival of 18-27% of patients with disease outside the uterus [4,5]. Also, in cases of disease confined to the corpus, the rate of relapse is high (31-80%), particularly in patients who are not surgically staged [6,7]. Some studies reported a 5-year survival rates of 15-30% of patients with clinical stage I USC [8,9] who underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO). Since the understanding of the importance of surgical staging in high-risk histologies has evolved, survival has improved. In the 25th Annual Report of FIGO, the 5-year survival rates for surgical stage I USC was 77% of patients who had not received any adjuvant therapy. The addition of adjuvant radiation therapy improved 5-year absolute survival for USC by approximately 8% [10]. However, the lack of prospective randomized studies does not allow to support optimal adjuvant treatment after surgery. Most of the available data are based on small, retrospective single- and multi-institutional studies [11,12]. Indeed, following the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, systemic therapy plus vaginal brachytherapy (VBT) or VBT in selected cases of non-invasive disease, represent valid options for stage IA serous carcinoma. While, for stage IB, systemic therapy plus or minus external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), and plus or minus VBT is recommended [13].

Despite these limitations, because of its aggressive behavior and pattern of recurrence, the treatment of USC is multimodal and it includes surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (RT). Adjuvant systemic platinum-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy after surgery showed an improved disease-free survival and overall survival with a reduction of recurrence rates [14,15,16,17,18]. In particular, VBT, in combination with chemotherapy, may play a very important role in patients with early USC because of its potential to provide an excellent dose distribution, shorter treatment duration, and preservation of the organ at risk.

The aim of this review was to examine efficacy of VBT after surgery and chemotherapy in stage I USC, in terms of disease-free survival (DFS), local control (LC), cancer specific survival (CSS), overall survival (OS), and safety.

Material and methods

A systematic research using PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane library was performed in order to identify full articles evaluating the efficacy of VBT in patients with stage I uterine serous carcinoma. A search in ClinicalTrials.gov was conducted in order to detect ongoing or recently completed trials, and in PROSPERO for searching ongoing or recently completed systematic reviews. The studies were identified using the following medical subject headings (MeSH) and keywords including: “endometrial neoplasms”, “brachytherapy”, and “endovaginal radiotherapy”. The search was restricted to English language. The Medline search strategy was: (“Brachytherapy” [Mesh] OR “Brachytherapy” [All fields]) AND (“Endometrial Neoplasms” [Mesh] OR “Endometrial Cancer” [All fields]). To avoid missing relevant studies, we chose this strategy with high sensitivity, but low specificity.

We analyzed clinical studies only as full text of patients with stage I uterine serous carcinoma treated with VBT alone after surgical staging and adjuvant chemotherapy. Conference papers, surveys, letters, editorials, book chapters, and reviews were excluded. Patients who underwent previous treatments were excluded. Time frame from 1990 till 2018 as years of publication was considered.

Four independent authors expert in endometrial cancer regarding interventional radiotherapy and gynecological endometrial cancer screened citations in titles and abstracts in order to identify appropriate papers. Eligible citations were retrieved for full-text review. Uncertainties about their inclusion in the review were considered by a multicenter expert team.

The primary outcome was the DFS after VBT during follow-up. Secondary outcome included: LC, OS, CSS, and adverse event rates.

A summary table was created including sample size, median age, DFS, LC, toxicity, OS, and CSS.

Results

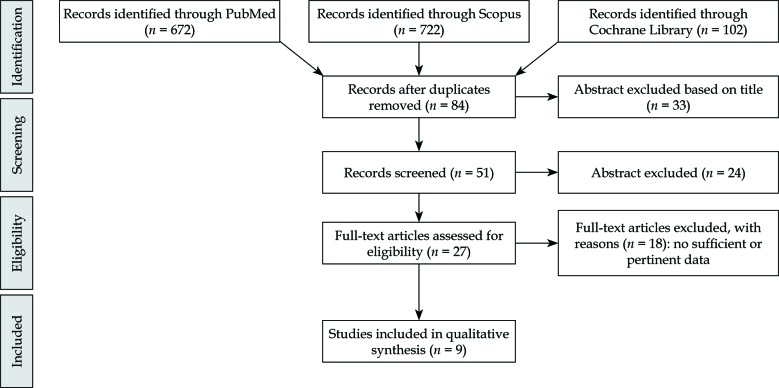

The literature search resulted in 672 articles. After exclusion by title and abstract, and after elimination of conference papers, surveys, letters, editorials, book chapters, reviews, and of non-English language, 27 papers were assessed via full text for eligibility. Of these, 17 articles were excluded due to insufficient data, leaving 9 studies assessing the clinical efficacy of VBT in DFS (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow-chart

All studies were retrospective [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. In accordance with the selection criteria, only data from the VBT treatment arms were extracted and considered for the analysis.

Our review identified 364 patients (with an average age of 67 years) with endometrial serous cancer, 331 with FIGO stage IA disease and 33 with FIGO stage IB.

All patients had undergone TAH/BSO. Pelvic lymph nodes dissection ranged from 80% to 100%, while para-aortic lymphadenectomy ranged from 35% to 100%. Peritoneal cytology ranged from 53% to 100% and omental sampling ranged from 57% to 100%. The presence of positive lymphovascular invasion (LVI) was reported in 46 patients out of 364 patients analyzed.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered with intervals of at least one week between chemotherapy and VBT. Chemotherapy consisted of platinum/taxane doublets.

Adjuvant VBT was delivered to the proximal two-thirds of the vagina and prescribed at an average dose of 21 Gy (range, 12-37.5 Gy) in 3 fractions at a depth of 0.5-0.7 cm [21,22] or at vaginal surface of the upper half of vagina [19,24,27].

The studies reported vaginal cuff, pelvic, and distant relapse in 1.6%, 7.2%, and 13.5% of patients, respectively.

The average LC was 97.5% (range, 91-100%), DFS was 88% (range, 82-94%), OS was 93% (range, 72-100%), CSS was 89.4% (range, 84.8-94%), and G3-G4 toxicity was 0%. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Period | Study | Size, n | Median age (years) | IRT (Gy) | CT | FU | DFS | LC | TOX G3-G4 | OS | CSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tétreault-Laflamme et al. [19] | 2006-12 | Obser | IRT, 32 IRT + EBRT, 25 |

62 (47-83) 65 (52-79) |

31.05/3 fr 21/3 fr |

Yes | 35 months | 3-y I, 88% 3-y I, 84% |

3-y I, 97% 3-y I, 100% |

0% | 3-y I, 100% 3-y I, 94% |

|

| DuBeshter et al. [20] | 1995-01 | Obser | Stage IA, 10 Stage IB, 9 |

67 (27-96) | 21/3 fr | Yes | 5-y IA, 100% 5-y IB, 100% |

n.a. | ||||

| Desai et al. [21] | 1996-10 | Obser | Stage IA, 56 Stage IB, 10 |

67 (27-88) | 21/3 fr | Yes | 62 months | 5-y IA, 91% 5-y IB-II, 78.5% |

5-y IA, 96.2% 5-y IB-II, 87.7% |

n.a. | 5-y IA, 94.3% 5-y IB-II, 80% |

|

| Kiess et al. [22] | 2000-09 | Obser | Stage IA, 30 Stage IB, 4 |

67 (51-80) | 21/3 fr | Yes | 58 months | 5-y I, 88% 5-y II, 71% |

100% | 8% | 5-y I, 93% 5-y II, 71% |

|

| Mahdi et al. [23] | 2000-12 | Obser | Stage IA, 27 | 66 (49-90) | 21/3 fr | Yes | 47.7 months | 5-y IA, 88% | 5-y IA, 97.4% | n.a. | 5-y IA, 93.3% | |

| Qu et al. [24] | 2004-15 | Obser | Stage IA, 58 | 67.4 ±8.6 | 21/3 fr | Yes | 32 months | 5-y, 60.93% |

5-y, 82.99% |

n.a | 5-y, 61.96% |

5-y, 79.99% |

| Robbins et al. [25] | 1998-09 | Obser | IRT, 33 IRT + EBRT, 23 |

64 (59-83) 69 (59-81) |

37.5 | Yes | 54 months | 5-y I, 85.6% 5-y I-II, 67.3% |

5-y I, 90.6% 5-y I-II, 71.8% |

n.a. | 5-y IA, 71.9% |

5-y I, 84.8% 5-y I-II, 78.9% |

| Barney et al. [26] | 1998-11 | Obser | Stage IA, 74 | 66 (44-86) | 21/3 fr | Yes | 36 months | 5-y I, 92% | 5-y I, 100% | n.a. | 5-y I, 85% | |

| Donovan et al. [27] | 2000-14 | Obser | Stage IA, 21 | 68 (45-90) | 31.5/3 fr | Yes | 38 months | 5-y, 86% | 5-y, 96% | n.a | 5-y, 95% |

IRT – interventional radiotherapy, EBRT – external beam radiotherapy, Obser – observational study, DFS – disease-free survival, LC – local control, OS – overall survival, CSS – cancer specific survival, TOX – toxicity, fr – fractions, y – years, G – grading

Discussion

The present review showed that IRT alone may be an adequate RT technique in women with stage I USC, who underwent appropriate surgical staging and received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Uterine serous carcinoma patients have a high-risk to develop local and distant relapse [28], therefore it is essential to ensure an adequate treatment even if patients with an early stage disease. While prospective studies have demonstrated that the delivery of chemotherapy in combination with external beam radiation in an advanced stage disease may increase survival benefit and decreases local recurrences [29,30,31,32,33], the role of radiation in early stage USC has been more difficult to demonstrate.

Owing to high-rate of distant recurrences, many studies recommended a more systemic approach to therapy for USC [34]. Treatment of women with uterine-confined USC with adjuvant chemotherapy is controversial due to lack of prospective randomized trials. However, in patients with stage I/II disease who were treated with observation only, a systemic adjuvant therapy is considered necessary on the basis of several retrospective studies. Only women who have undergone appropriate surgical staging and have no residual disease in the uterus at the time of surgery may not need further therapy [35,36,37]. The decision whether and how to treat women with stage I USC should be undertaken with careful consideration of the risks of relapse as well as of the treatment for each patient.

Given the rarity of this disease, all studies are retrospective and involve small numbers of patients, different histologies and stages, variable treatment regimens, and few events. This generates difficulties in interpreting the effectiveness of treatment regimens. The challenge in determining appropriate adjuvant treatment in stage I USC is, also, balancing a reduction in recurrence with treatment-related toxicity and complications. Indeed, following the NCCN guidelines, observations, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or combination treatment are all valid therapies for patients with stage I USC [13]. Many studies have reported significant toxicity rates in stage IA patients treated with chemotherapy and pelvic EBRT, with a DFS remaining at around 85% [38,39,40]. While some centers have adopted VBT as the local therapy in this setting [23,41,42], many centers continue to use pelvic EBRT as a standard treatment [43,44]. In well selected stage I USC, VBT may be particularly useful in reducing local recurrences and toxicity. An adequate surgical staging is fundamental in guiding adjuvant therapy and defining patients who may undergo VBT. Many studies showed that the adequate staging is a factor associated with an improvement of DFS and OS [23,35,44]. There is general agreement that complete surgical staging in this high-risk population should consist of peritoneal cytology, omentectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection; however, the specific nodal counts required (selective sampling vs. complete dissection), and the extent of omental and peritoneal evaluation remain controversial and institution-dependent. Three retrospective studies compared efficacy between EBRT and VBT in patients with stage I USC [19,25,45,46]. While Modh et al., in patients treated with VBT, reported longer 5-year survival rates than those treated with EBRT (VBT: 84% vs. EBRT: 75%; p < 0.001) [45], the other two studies showed no benefit from adding pelvic EBRT to VBT in terms of OS and LC [19,25]. These last results were confirmed by the Gynecologic Oncology Group 249 trial that showed no difference in OS or DFS between patients who received pelvic EBRT or VBT with three cycles of chemotherapy [46]. In the PORTEC-3 trial, women with serous or clear-cell cancers had at least as much improvement in failure-free survival with the addition of chemotherapy as women with endometrioid endometrial cancer. When comparing serous cancers with other histological types, worse OS and DFS were found for USC; patients with USC had a DFS benefit with chemoradiotherapy, but this benefit was not significant given the small number of USC and events [47]. Our results of DFS and OS are comparable with those reported in the GOG 249 and PORTEC-3 trial. Indeed, the present review suggests that the use of VBT in selected patients is associated with good outcomes in terms of LC (average 98.7%; range, 92.9-100%), DFS (average 88%; range, 85-95%), OS (average 93%; range, 90-94%), CSS 96.5% (range, 90-93%), and toxicity (range, 0-8%). The classic prognostic risk factors that guide treatment for endometrioid endometrial cancer, including depth of invasion, LVI, tumor size, and age, have not consistently been associated with prognosis for USC [43,44]. Stage IB [21], cervical stromal involvement [22], and lymphadenectomy [23] were an independent predictor of DFS and OS. The potential role of CA-125 as a tumor marker for USC remains unclear [43,44], but CA-125 may be valuable for monitoring disease [22]. Stage IA patients with residual uterine disease should receive concomitant VBT and platinum-based chemotherapy.

There are various fractionation schemes used clinically with no general consensus about the superiority of one regimen over the other. Traditionally, the doses for brachytherapy have been formulated to deliver approximately 60-65 Gy low-dose-rate (LDR) equivalent to the vaginal surface. Several institutions used different dose fractionation regimens, which have achieved acceptable outcomes based on their own published experience. There have not been single randomized trial comparing all these regimens. The most recent survey of vaginal brachytherapy practice [48] found that the most commonly used fractionation scheme is 7 Gy × 3 prescribed to 0.5 cm depth, followed by 6 Gy in 5 fractions prescribed to vaginal surface, and the last most common were 5.5 Gy × 4 and 5 Gy × 5 to 0.5 cm depth, and finally 7.5 Gy × 5 prescribed to vaginal surface. All these regimens appear effective based on institutional reports. Also, our review showed that the most common fractionation scheme was 7 Gy × 3 prescribed to 0.5 cm depth. Only 3 studies [19,25,27] used different schedules.

Regarding late toxicity, our review showed that the treatment is very well tolerated. The main side effects consisted of grade G1-G2, while G3-G4 late vaginal toxicities have been reported only in few cases (range, 0-8%) in line with the current data in literature [49,50].

Despite these positive results, VBT is not always considered as a treatment option in patients with stage I USC. Different Italian survey confirmed that despite this procedure is available, only few centers considered it for the treatment of USC [42,51]. Probably, the lack of experience, expertise, and treatment complexity do not allow the use of VBT in the clinical routine. VBT allows to deliver high doses of radiation to tumors, with minimal exposure of adjacent organs at risk. 3-dimensional computed tomography-based treatment planning offers all the advantages of a personalized treatment to achieve the optimum therapeutic index. Nevertheless, it is important that in no experienced centers, VBT can result in crucial side effects [52]. Considering the rarity of this disease, every case of stage I USC should be discussed with individual approach by an expert multidisciplinary team to provide more homogeneous treatment methods and improvement of clinical outcomes [53,54,55].

The possibility to identify a subgroup of patients with better survival prognosis could be used to offer VBT as a treatment, resulting in better quality of life. Several studies proposed a prognostic model, nomogram, or large-database to help identify the best strategy in individual patients [56,57,58,59].

Conclusions

Based on our review, we suggest that chemotherapy remains a critical component of treatment given the high rates of distant recurrence, while VBT appears sufficient to reduce local relapse without pelvic EBRT.

Larger, multicenter, randomized studies are required to determine the appropriate adjuvant therapy for patients with stage I USC, and to further characterize risk factors for recurrence and progression.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hendrickson M, Ross J, Eifel P et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a highly malignant form of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1982; 6: 93-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slomovitz BM, Burke TW, Eifel PJ et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC): a single institution review of 129 cases. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 91: 463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicklin JL, Copeland LJ. Endometrial papillary serous carcinoma: patterns of spread and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1996; 39: 686-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tropé C, Kristensen GB, Abeler VM. Clear-cell and papillary serous cancer: treatment options. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 15: 433-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews RP, Hutchinson-Colas J, Maiman M et al. Papillary serous and clear cell type lead to poor prognosis of endometrial carcinoma in black women. Gynecol Oncol 1997; 65: 206-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naumann RW. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: state of the state. Curr Oncol Rep 2008; 10: 505-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristow RE, Asrari F, Trimble EL et al. Extended surgical staging for uterine papillary serous carcinoma: survival outcome of locoregional (stage I-III) disease. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 81: 279-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffrey JF, Krepart GV, Lotocki RJ. Papillary serous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 1986; 67: 670-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauchlan SC. Tubal (serous) carcinoma of the endometrium. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1981; 105: 615-618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creasman WT, Kohler MF, Odicino F et al. Prognosis of papillary serous, clear cell, and grade 3 stage I carcinoma of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 95: 593-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boruta DM, Gehrig PA, Fader AN et al. Management of women with uterine papillary serous cancer: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) review. Gynecol Oncol 2009; 115: 142-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon JS, Abrams J, Sugimoto A et al. Is adjuvant therapy necessary for stage IA and IB uterine papillary serous carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma after surgical staging? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008; 18: 820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Uterine Neoplasms (Version 3.2019) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf (accessed: 31 Aug 2019).

- 14.Fader AN, Drake RD, O’Malley DM et al. Platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy favorably impacts survival outcomes in stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Cancer 2009; 115: 2119-2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MR, Peters WA 3rd, Drescher CW. Cisplatin, doxorubicin hydrochloride, and cyclophosphamide followed by radiotherapy in high-risk endometrial carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 170: 1677-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy KT, Rotmensch J, Yamada SD et al. Outcome and patterns of failure in patients with stages I-IV clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium: implications for adjuvant radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 55: 1272-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas M, Mariani A, Wright JD et al. Surgical management and adjuvant therapy for patients with uterine clear cell carcinoma: a multi-institutional review. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 108: 293-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunil RA, Bhavsar D, Shruthi MN et al. Combined external beam radiotherapy and vaginal brachytherapy versus vaginal brachytherapy in stage I, intermediate-and high-risk cases of endometrium carcinoma. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2018; 10: 105-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tétreault-Laflamme A, Nguyen-Huynh TV, Carrier JF et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and vaginal vault brachytherapy with or without pelvic radiotherapy for stage I papillary serous or clear cell endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016; 26: 301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DuBeshter B, Estler K, Altobelli K et al. High-dose rate brachytherapy for Stage I/II papillary serous or clear cell endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 94: 383-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai NB, Kiess AP, Kollmeier MA et al. Patterns of relapse in stage I-II uterine papillary serous carcinoma treated with adjuvant intravaginal radiation (IVRT) with or without chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 2013; 131: 604-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiess AP, Damast S, Makker V et al. Five-year outcomes of adjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy and intravaginal radiation for stage I-II papillary serous endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 127: 321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahdi H, Rose PG, Elshaikh MA et al. Adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy decreases the risk of vaginal recurrence in patients with stage I non-invasive uterine papillary serous carcinoma. A multi-institutional study. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 136: 529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu XM, Velker VM, Leung E et al. The role of adjuvant therapy in stage IA serous and clear cell uterine cancer: A multi-institutional pooled analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2018; 149: 283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robbins JR, Siddiqui MS, Al-Wahab Z et al. Clinical outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy and vaginal brachytherapy with or without pelvic radiation for surgical stage I-II uterine serous carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2012; 33: 449-454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barney BM, Petersen IA, Mariani A et al. The role of vaginal brachytherapy in the treatment of surgical stage I papillary serous or clear cell endometrial cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013; 85: 109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan E, Reade CJ, Eiriksson LR et al. Outcomes of adjuvant therapy for stage ia serous endometrial cancer. Cureus 2018; 10: e3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman AD, Ferguson SE, Atenafu EG et al. Canadian high risk endometrial cancer (CHREC) consortium: analyzing the clinical behavior of high risk endometrial cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 139: 268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleming GF, Brunetto VL, Cella D et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin plus cisplatin with or without paclitaxel plus filgrastim in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2004; 15: 2159-2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming GF, Filiaci VL, Bentley RC et al. Phase III randomized trial of doxorubicin + cisplatin versus doxorubicin + 24 h paclitaxel + filgrastim in endometrial carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. Ann Oncol 2004; 15: 1173-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallion HH, Brunetto VL, Cibull M et al. Randomized phase III trial of standard timed doxorubicin plus cisplatin versus circadian timed doxorubicin plus cisplatin in stage III and IV or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3808-3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thigpen JT, Brady MF, Homesley HD et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin with or without cisplatin in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3902-3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homesley HD, Filiaci V, Gibbons SK et al. A randomized phase III trial in advanced endometrial carcinoma of surgery and volume directed radiation followed by cisplatin and doxorubicin with or without paclitaxel: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol 2009; 112: 543-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutton G, Axelrod JH, Bundy BN et al. Adjuvant whole abdominal irradiation in clinical stages I and II papillary serous or clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 100: 349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner BC, Knisely JP, Kacinski BM et al. Effective treatment of stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma with high dose-rate vaginal apex radiation (192Ir) and chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998; 40: 77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.del Carmen MG, Birrer M, Schorge JO et al. Uterine papillary serous cancer: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 127: 651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huh WK, Powell M, Leah CA III et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: comparison of outcomes in surgical Stage I with and without adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 91: 470-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutton G, Axelrod JH, Bundy BN et al. Adjuvant whole abdominal irradiation in clinical stages I and II papillary serous or clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 100: 349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Putten LJ, Hoskins P, Tinker A et al. Population-based treatment and outcomes of Stage I uterine serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 132: 61-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foerster R, Kluck R, Rief H et al. Survival of women with clear cell and papillary serous endometrial cancer after adjuvant radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol 2014; 9: 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eldredge-Hindy HB, Eastwick G, Anne PR et al. Adjuvant vaginal cuff brachytherapy for high-risk, early stage endometrial cancer. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2014; 6: 262-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Autorino R, Vicenzi L, Tagliaferri L et al. A national survey of AIRO (Italian Association of Radiation Oncology) brachytherapy (Interventional Radiotherapy) study group. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2018; 10: 254-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fader AN, Starks D, Gehrig PA et al. An updated clinicopathologic study of early-stage uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC). Gynecol Oncol 2009; 115: 244-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamilton CA, Cheung MK, Osann K et al. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 642-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Modh A, Burmeister C, Munkarah AR et al. External pelvic and vaginal irradiation vs. vaginal irradiation alone as postoperative therapy in women with early stage uterine serous carcinoma: Results of a National Cancer Database analysis. Brachytherapy 2017; 16: 841-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Randall ME, Filiaci V, McMeekin DS et al. Phase III trial: adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy versus vaginal brachytherapy plus paclitaxel/carboplatin in high-intermediate and high-risk early stage endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1810-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Boer SM, Powell ME, Mileshkin L et al. Adiuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): final results of an international, open-label, multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: 295-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harkenrider MM, Block AM, Alektiar KM et al. American Brachytherapy Task Group Report: Adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy for early-stage endometrial cancer: A comprehensive review. Brachytherapy 2017; 16: 95-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delishaj D, Barcellini A, D’Amico R et al. Vaginal toxicity after high-dose-rate endovaginal brachytherapy: 20 years of results. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2018; 10: 559-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Autorino R, Tagliaferri L, Campitelli M et al. EROS study: evaluation between high-dose-rate and low-dose-rate vaginal interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) in terms of overall survival and rate of stenosis. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2018; 10: 315-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tagliaferri L, Kovács G, Aristei C et al. Current state of interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) education in Italy: results of the INTERACTS survey. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2019; 11: 48-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lettmaier S, Strnad V. Intraluminal brachytherapy in oesophageal cancer: defining its role and introducing the technique. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2014; 6: 236-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kovács G, Tagliaferri L, Valentini V. Is an Interventional Oncology Center an advantage in the service of cancer patients or in the education? The Gemelli Hospital and INTERACTS experience. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2017; 9: 497-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morganti AG, Pasquarelli L, Deodato F et al. Videoconferencing to enhance the integration between clinical medicine and teaching: a feasibility study. Tumori 2008; 94: 822-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kovács G, Tagliaferri L, Lancellotta V et al. Interventional oncology: should interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) be integrated into modern treatment procedures? Turk J Oncol 2019; 34: 16-22. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tagliaferri L, Budrukkar A, Lenkowicz J et al. ENT COBRA ONTOLOGY: the covariates classification system proposed by the Head & Neck and Skin GEC-ESTRO Working Group for interdisciplinary standardized data collection in head and neck patient cohorts treated with interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy). J Contemp Brachytherapy 2018; 10: 260-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tagliaferri L, Gobitti C, Colloca GF et al. A new standardized data collection system for interdisciplinary thyroid cancer management: Thyroid COBRA. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 53: 73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tagliaferri L, Pagliara MM, Masciocchi C et al. Nomogram for predicting radiation maculopathy in patients treated with Ruthenium-106 plaque brachytherapy for uveal melanoma. J Contemp Brachytherapy 2017; 9: 540-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tagliaferri L, Kovács G, Autorino R et al. ENT COBRA (Consortium for Brachytherapy Data Analysis): interdisciplinary standardized data collection system for head and neck patients treated with interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy). J Contemp Brachytherapy 2016; 10: 260-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]