Abstract

Ulcerative dermatitis in laboratory mice remains an ongoing clinical problem and animal welfare issue. Many products have been used to treat dermatitis in mice, with varying success. Recently, the topical administration of healing clays, such as bentonite and green clays, has been explored as a viable, natural treatment. We found high concentrations of arsenic and lead in experimental samples of therapeutic clay. Given the known toxic effects of these environmental heavy metals, we sought to determine whether the topical administration of a clay product containing bioavailable arsenic and lead exerted a biologic effect in mice that potentially could introduce unwanted research variability. Two cohorts of 20 singly housed, shaved, dermatitis free, adult male CD1 mice were dosed daily for 2 wk by topical application of saline or green clay paste. Samples of liver, kidney and whole blood were collected and analyzed for total arsenic and lead concentrations. Hepatic and renal concentrations of arsenic were not different between treated and control mice in either cohort; however, hepatic and renal concentrations of lead were elevated in clay treated mice compared to controls in both cohorts. In addition, in both cohorts, the activity of δ-aminolevulinate acid dehydratase, an enzyme involved with heme biosynthesis and a marker of lead toxicity, did not differ significantly between the clay-treated mice and controls. We have demonstrated that these clay products contain high concentrations of arsenic and lead and that topical application can result in the accumulation of lead in the liver and kidneys; however, these concentrations did not result in measurable biologic effects. These products should be used with caution, especially in studies of lead toxicity, heme biosynthesis, and renal α2 microglobulin function.

Abbreviations: AAS, atomic absorption spectrophotometry; ALA, δ-aminolevulinic acid; ALAD, δ-aminolevulinate acid dehydratase; GFAAS, graphite furnace-atomic absorption spectrometry; ICP, inductively coupled plasma; IVBA, in vitro bioaccessibility; LOD, limit of detection; UD, ulcerative dermatitis

Ulcerative dermatitis (UD) in laboratory mice is a skin condition consisting of varying levels of dermal lesions. These lesions often occur near the head and neck and can be exacerbated by excessive scratching, leading to open sores and bleeding. Secondary opportunistic bacterial infections can establish in the open wounds, causing the condition to worsen to the point where the animal must be euthanized. UD can be initiated by fighting between cagemates but is usually a spontaneous condition for which there is no single cause. Contributing factors include the animal's age, sex, and strain and environmental and dietary factors, such as high-fat diet.6,37

Over the years, many treatment options for UD have been reported,36 such as nail trimming,2,5,52 chlorhexidine antiseptic,42 maropitant citrate,76 Caladryl ointment,19 ibuprofen,22 and vitamin E.38 More recently, the topical administration of natural therapeutic clays, such as calcium bentonite13 and French green clays,43,77,78 has been reported as a viable treatment for UD. Historically, natural clays have been used to treat problems ranging from gastrointestinal, dermatologic, toxicologic, dental, and optical conditions to issues of hygiene, mineral deficiency, and overall wellbeing in many fields, such as the pharmaceutical, medical, veterinary, cosmetic, and pelotherapeutic indus tries.3,15,16,21,27,38,41,56,73,74 Bentonite generally refers to clays that originate from volcanic ash and are largely composed of montmorillonite, a clay mineral in the smectite group that has a tendency to swell when in contact with water, yielding their description as ‘swelling clay.’ 1,8,34 French green clays range in color from shades of gray to green and are named according to the area of southern France where they were mined originally. These clays are composed mainly of minerals from the illite group but often contain various amounts of montmorillonite.78 The terms therapeutic, bentonite, montmorillonite, and green healing clay are often confused, because they frequently are used interchangeably, in part due to differences in the clay source, composition, color, and the reference material. For example, mineral and geologic descriptions are often more technical than those used by many herbalists and for various folk and holistic medicines. The healing effects of these clays have been attributed to their mineral and chemical compositions78 and ion exchange,54 antibacterial,31,51,54,77,79 and adsorptive properties.49,50

The low cost and worldwide commercial availability of these natural therapeutic clays make them a promising alternative to treat UD and bacterial skin infections.20,31,77,79 Given the positive reports regarding bentonite clay used for the treatment of UD, we tested several commercially available brands of healing clay for consideration as treatment options. Our lab routinely screens products containing natural components to which animals may be exposed. Experimental samples of therapeutic clay were analyzed for contaminants and found to contain high concentrations of arsenic and lead. Arsenic and lead are heavy metal elements present in the environment and are known to be toxic in mammalian species.33 The objectives of the current study were to evaluate a variety of clay types for total arsenic and lead contents, to determine whether topical application of a clay product resulted in elevated lead or arsenic concentrations in tissues, and to assess any biologic effects from clay exposure.

Materials and Methods

Clay.

Three different types of healing clays reported to be used in the lab animal field were purchased from commercial retail sources. Brand 1 was a French green healing clay (100% Natural French Green Clay Facial Treatment Mask, Rainbow Research, Bohemia, NY), Brand 2 was a calcium bentonite clay (Indian Healing Clay 100% Natural Calcium Bentonite Clay, Aztec Secret Health and Beauty, Pahrump, NV), and Brand 3 was an “ultra-pure pharmaceutical grade” sodium bentonite clay (Ultra Pure Clay Harmony, Perfect Body Harmony, Green Footprint Solutions, Austin, TX).

Mice.

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) is fully AAALAC-accredited and is committed to the humane care and use of animals in research. All animal care was provided in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.35 All procedures using animals were approved by the NIEHS Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 40 mice were used in the study. Two cohorts each comprised of 20 adult male CD1 (Crl:CD1) mice (age, 7 to 8 wk) were obtained from an inhouse-maintained colony. Both of these independent cohorts were comprised of 10 saline- and 10 clay-paste–treated animals. The 2 cohorts were evaluated approximately 12 mo apart. All mice were dermatitis free and tested negative for the following murine pathogens: enzootic diarrhea of infant mice, cilia-associated respiratory bacillus, ectromelia virus, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, hantavirus, lactate dehydrogenase elevating virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, minute virus of mice, mouse adenovirus types 1 and 2, mouse cytomegalovirus, mouse hepatitis virus, mouse norovirus, mouse parvovirus types 1 through 5, mouse pneumotropic (K) virus, mouse polyoma virus, mouse thymic virus, murine ectoparasites (M. musculinis, M. musculi, R. affinis), murine Helicobacter spp., murine pinworms (S. muris, S. obvelata, A. tetraptera), Mycoplasma pulmonis, Pasteurella pneumotropica, pneumonia virus of mice, reovirus type 3, Sendai virus, and Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus.

Mice were randomized to treatment or control groups by using a random number generator30 and singly housed in individually ventilated microisolation cages (Tecniplast USA, West Chester, PA) at an intracage air change rate of 72 volumes hourly and containing autoclaved hardwood bedding (Sani-Chips, PJ Murphy Forest Products, Mount Jewett, PA) and nesting material (Enviro-dri, Shepherd Specialty Papers, Watertown, TN) under room conditions of controlled temperature (22.2 ± 2.0 °C), relative humidity (40% to 60%), air changes (10 to 15 changes hourly), and light cycle (12:12 h light:dark). Mice were given reverse-osmosis–purified deionized water and fed an autoclaved open-formula maintenance diet (NIH31, Envigo, Madison, WI) without restriction. Cages were changed every 14 d, and mice were checked daily.

Clay application.

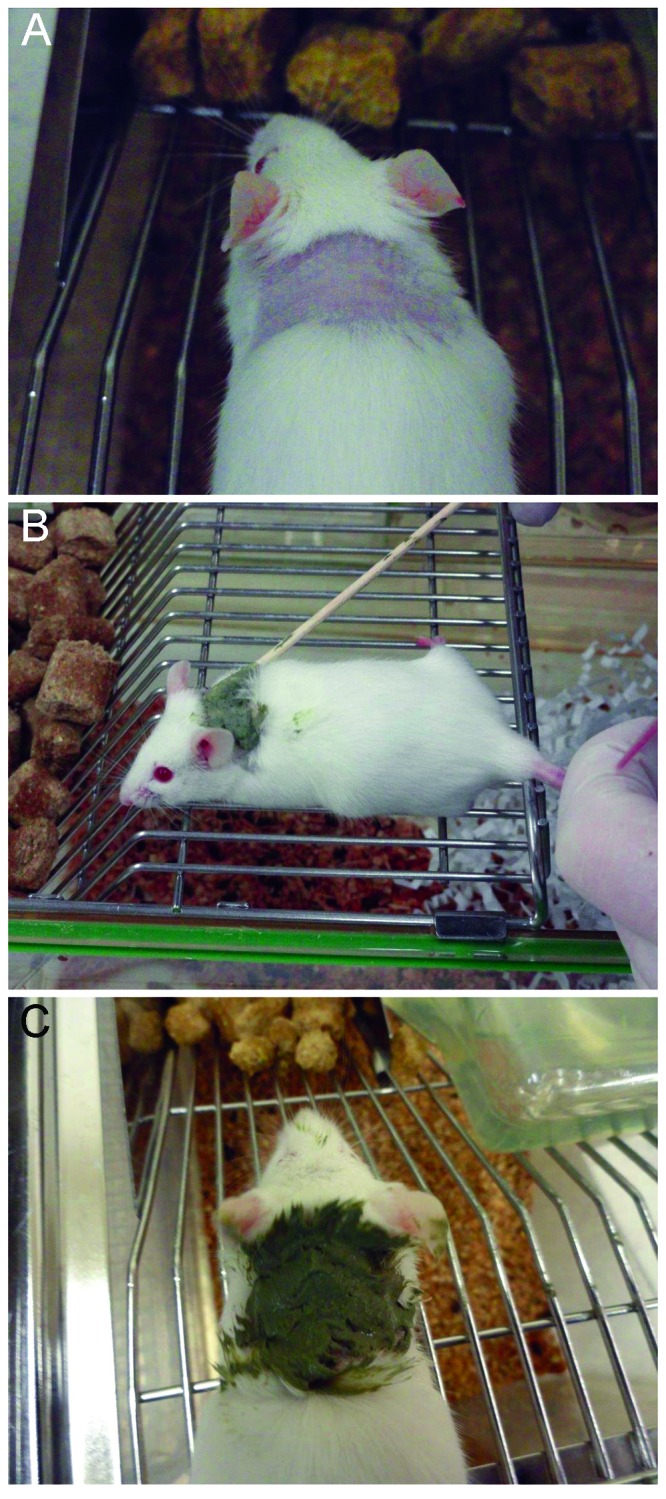

A clay paste mixture was prepared by combining 0.9% saline with the clay powder (100% Natural French Green Clay Facial Treatment Mask, Rainbow Research) in a 1:1 (v:v) ratio. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, body weights were recorded, and a 1.5 × 1.5-cm area of fur was clipped from the back of the neck (Figure 1). Clay paste (0.1 to 0.4 g daily) or saline was applied topically daily for 14 consecutive days to the clipped area by using sterile cotton-tipped swabs (Figure 1) to simulate the once-daily treatment of UD by using clay as done at other institutions.13 At the end of the 2-wk treatment periods, all mice were euthanized by using CO2. Final body weights were measured, and samples of whole blood, liver, kidney, and the skin directly under application site were collected. Heparinized tubes were used to collect whole blood, which was held on ice and processed within 30 min after collection. Liver and kidneys were weighed prior to apportioning for total arsenic and lead analysis (90 to 250 mg), flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C until additional analysis.

Figure 1.

(A) Application area after clipping the fur. (B) Clay paste application by using a sterile cotton-tipped swab. (C) Clay paste after application.

Analysis of total arsenic and lead concentrations.

Total arsenic and lead levels in animal feed, bedding, water, enrichment, clay, saline and rodent tissues were analyzed by using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GFAAS; AAnalyst 600 with AS 800 autosampler and end-capped transversely heated graphite atomizer tubes; PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT). On arrival in the lab, samples (approximately 100 to 300 mg tissue, 300 µL blood) were digested in 50% of 2:1 ultrapure perchloric acid (70%; Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO):nitric acid (70%; Sigma–Aldrich) mixture and 50% water.72 To prevent premature volatilization before vaporization and therefore loss of signal, the manufacturer's instructions called for a matrix modifier containing a mixture of palladium and magnesium for arsenic and a mixture of NH4H2PO4 and magnesium for lead.33 All samples were run in duplicate, and the limit of detection (LOD) for both arsenic and lead via the GFAAS method was 5.0 ppb.

In vitro bioaccessibility assay (IVBA).

IVBA was performed as previously described9-12 to estimate the relative bioavailability (or fraction that is absorbed across the gastrointestinal tract) of both total arsenic and lead in the study clay and animal feed. Prior to IVBA, we used EPA method 3051 (microwave digestion)63 with analysis by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) mass spectrometry in accordance with EPA method 6020 to reanalyze the total arsenic and lead levels in the French green clay, animal feed, bedding, and enrichment used in both cohorts.65 IVBA was performed on clay and feed samples only from both cohorts by using EPA method 134066 for lead and EPA method 9200.2-86 for arsenic.64 Briefly, 1 g of clay was added to 100 mL of simulated gastric fluid (0.4 M glycine, pH 1.5) in a 125-mL high-density polyethylene bottle rotating end over end at 37 °C for 1 h. Extraction solutions were stored at 4 °C for subsequent analysis by ICP–optical emission spectroscopy. IVBA was calculated and expressed on a percentage basis according to the following equation:

Bioaccessibility of As or Pb (%) = (in vitro As or Pb/total As or Pb) × 100%.9-12

All samples were run in triplicate, and the method reporting limit for total arsenic or lead analysis and IVBA was 1 µg As or Pb per gram of clay or feed (that is, 1 ppm or 1000 ppb).

ALAD activity.

The activity of δ−aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) in liver and kidney (1:3 w/v in Tris-acetate buffer) was measured to assess lead toxicity, as previously described.25,28,29 Lead reversibly replaces zinc at the active site of ALAD, resulting in enzymatic inhibition.23 The enzymatic inhibition can be restored in vitro with the addition of dithiothreitol (DTT), allowing for the assessment of the extent of inhibition by comparing activity with and without DTT.25 Results are expressed as enzyme activity (U/mg total protein) without DTT (nonreactivated activity) compared with enzyme activity with DTT (reactivated total activity). TEST

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed and figures created by using Prism 7.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). In cohort 2, several measurements of tissue total arsenic (blood, liver, and kidney) and lead (blood) were below the LOD; these samples were assigned a value of LOD/√2 (or 5/√2 = 3.54) prior to analysis. Total arsenic and lead concentrations in the tissues were analyzed by using a D'Agostino and Pearson test for normality on each cohort. For data meeting normal distribution with equal standard deviations, unpaired parametric t tests were performed. Otherwise, for data meeting normal distribution with unequal standard deviation, a t test with Welch correction was used. A Mann–Whitney test was conducted on unpaired nonparametric data. ALAD activity was analyzed by using one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey multiple-comparison test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Total concentrations of arsenic and lead in clay and study components.

GFAAS revealed high concentrations of both total arsenic and lead in all clay products tested (Table 1). In the 3 brands of clay tested, the average arsenic concentrations ranged from 8,483 to 31,607 ppb, and average lead concentrations ranged from 21,457 to 54,754 ppb. Brand 1, French green study clay, contained the highest level of total arsenic concentration with a lot-to-lot average of 31,607 ppb and the second-highest concentration of lead, with a lot-to-lot average of 44,633 ppb. Brand 1 clay applied to the mice had similar concentrations of total arsenic (38,000 ppb) and lead (41,000 ppb) when measured by using ICP–MS as part of IVBA (Table 2). Brand 2 had a lot-to-lot average of 21,440 ppb for arsenic and 21,457 ppb for lead. Brand 3, the “ultra-pure pharmaceutical grade” sodium bentonite clay, contained the lowest concentration of total arsenic, with a lot-to-lot average of 8,483 ppb and the highest concentration of total lead, with a lot-to-lot average of 54,754 ppb.

Table 1.

Total arsenic and lead concentrations (ppb) in clay and study components

| Total arsenic | Total lead | |||

| Clay (n = 2) | Brand 1 | Study clay | 31,607 ± 1,597 | 44,633 ± 2,232 |

| Brand 2 | 21,440 ± 4,007 | 21,457 ± 3,857 | ||

| Brand 3 | 8,483 ± 565 | 54,754 ± 3,347 | ||

| Study components (n = 1) | ||||

| Feed | Cohort 1 | 272 | 774 | |

| Cohort 2 | 1,332 | 693 | ||

| Bedding | Cohort 1 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Cohort 2 | 224 | 1,781 | ||

| Enrichment | Cohort 1 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Cohort 2 | 260 | 169 | ||

| Animal water | Cohort 1 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Cohort 2 | 74 | 71 | ||

| Saline | Cohort 1 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Cohort 2 | 81 | 84 | ||

Total arsenic (As) and lead (Pb) concentrations determined by acid digestion with analysis by graphite furnace-atomic absorption spectrometry. All samples were measured in duplicate. Values for clay are presented as mean ± 1 SD; those for study components are presented as single-run means. The limit of detection (LOD) for both totals was 5.0 ppb.

Table 2.

Total arsenic and lead levels (ppb) and percentages in vitro bioaccessibility (IVBA)

| Sample ID | Total arsenica | % arsenic IVBA | Total leadb | % lead IVBA |

| Brand 1 = Study Clay | 38,000 ± 1,000 | 22 ± 0 | 41,000 ± 0 | 43 ± 1 |

| Feed- Cohort 1 | <LLOQ | <LLOQ | <LLOQ | <LLOQ |

| Feed- Cohort 2 | <LLOQ | <LLOQ | <LLOQ | <LLOQ |

| Bedding | <LLOQ | NT | <LLOQ | NT |

| Enrichment | <LLOQ | NT | <LLOQ | NT |

NT, not tested

Total arsenic and lead values were determined by using microwave digestion (EPA method 3051) with analysis by ICP–MS (EPA method 6020).

IVBA was performed in triplicate in accordance with EPA methods 9200.2-86 for aarsenic and 1340 for blead. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) for both totals and IVBA determination was 1 mg/kg; n = 1 for each component.

Study feed (NIH31) had low levels of total arsenic and lead in both cohorts (Table 1). The findings were comparable to what we have measured in previous feed lots (data not shown) and noted in the specifications of comparable commercially available rodent feeds. GFAAS documented undetectable (less than 5.0 ppb) concentrations of arsenic and lead in the rodent water, bedding, enrichment, and saline used to mix the clay paste in cohort 1 (Table 1). Despite appropriate equipment calibration, which occurred prior to running the samples for each cohort, GFAAS revealed low but detectable concentrations of arsenic and lead in these study components in cohort 2 (Table 1). The GFAA spectrophotometer required service between cohorts 1 and 2, and the lamp was changed, which could have affected measurements. However, the concentrations of arsenic and lead in these study components are so much lower than the concentrations measured in the clay that any absorption or potential biologic effects are likely negligible.

IVBA.

IVBA, which closely mimics the digestion process in mammalian systems, was performed on the study clay and animal feed to estimate the amounts of arsenic and lead that could potentially be absorbed and thus biologically available to organs and tissues. This assay is important because the body does not take up all forms of arsenic and lead. The concentrations of total arsenic and lead in the study clay and animal feed used for both cohorts as measured by ICP–MS for the IVBA are presented in Table 2. The measured concentrations of total arsenic (38,000 ppb) and lead (41,000 ppb) in the clay were comparable to those measured by GFAAS; whereas, the concentrations of total arsenic and lead in the feed, bedding, and enrichment were below the 1000-ppb method reporting limit. The study clay used in both cohorts had an arsenic bioaccessibility of 22% and a lead bioaccessibility of 43% (Table 2); that is, for every 1 μg of total arsenic or lead ingested, approximately 0.22 μg of arsenic or 0.43 μg lead would likely be absorbed.

Mice.

Mild to moderate dermatitis developed in some clay-treated (5/10 cohort 1; 3/10 cohort 2) and saline-treated (5/10 cohort 1; 2/10 cohort 2) mice from both cohorts. These small lesions were attributed to mild abrasions that occurred during fur clipping. All 20 mice from both cohorts tolerated daily application of the clay paste or saline throughout the 14-d treatment period. All clay-treated mice were observed grooming the application area almost immediately, with most or all the clay ingested within 20 to 30 min after application. During daily health checks, no detrimental effects were noted from the applications or dermatitis, and no differences in body weight were observed between the 2 treatment groups at the beginning and end of the study for both cohorts (data not shown). No changes in the feces of either group were noted. At necropsy, no gross lesions were apparent in the gastrointestinal tract of either group.

Total arsenic and lead concentrations in mouse tissue.

Total arsenic and lead concentrations in samples of blood, liver, and kidney from both cohorts were measured by using GFAA spectrophotometry. Given that we observed the mice removing the clay through grooming within 10 to 20 min of application, we felt that oral ingestion was the predominant route of exposure and that absorption through the skin was negligible. To confirm that skin absorption was not a significant route of absorption, we analyzed skin samples from a subset of cohort 1 mice (2 saline treated and 3 clay treated) and saw no differences in the total concentrations of arsenic and lead between the saline- and clay-treated groups (data not shown). The concentrations (ppb) of total arsenic and lead from whole blood, liver, and kidney of mice from both cohorts are shown in Figure 2. Since some mice in both cohorts developed dermatitis, we compared the total arsenic and lead concentrations in the blood, liver, and kidneys of clay treated mice with and without dermatitis and saw no differences (data not shown).

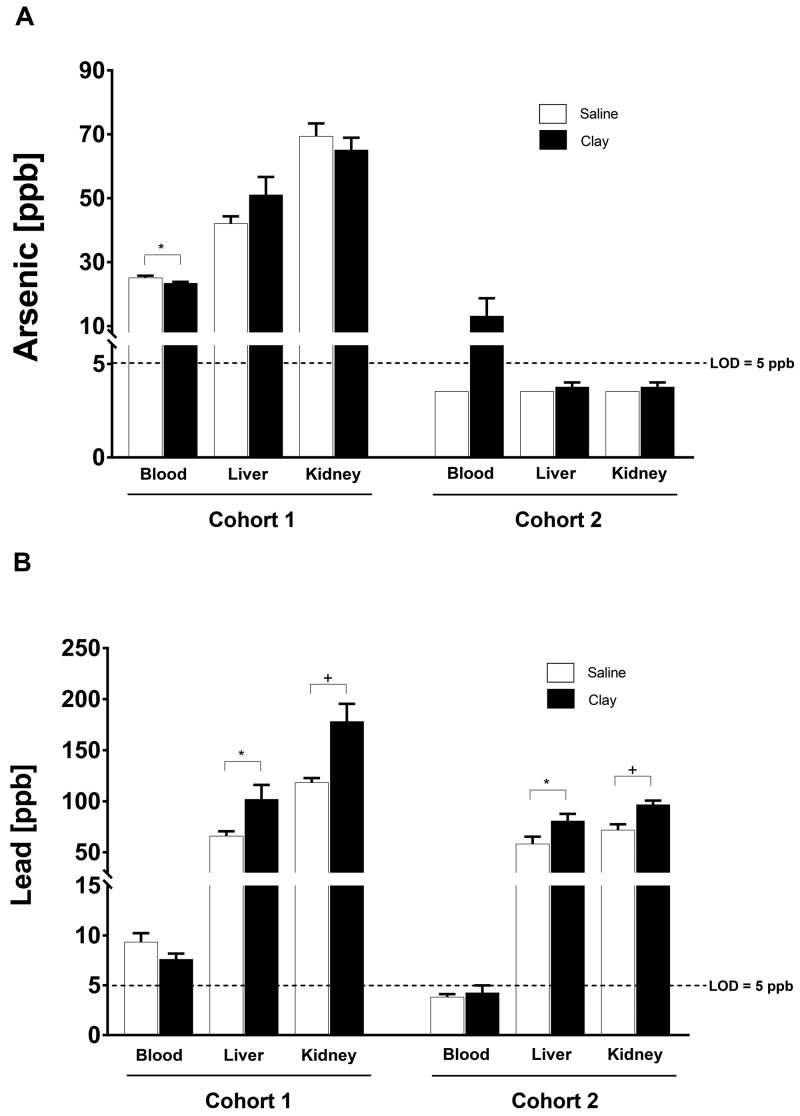

Figure 2.

(A) Tissue arsenic and (B) lead concentrations (ppb) as measured by graphite furnace-atomic absorption spectrometry at 14 d after topical application of saline (n = 10 per tissue, open bars) or clay (n = 10 per tissue, black bars). All samples were run in duplicate. In cohort 2, many samples were below the level of detection (LOD; 5 ppb) and were assigned a value of LOD/√2. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05; +, P < 0.005.

The GFAA spectrophotometer required service between cohorts 1 and 2, with the result that the total arsenic and lead concentration scales differed slightly between cohorts. However, measured values for the standards (0.0, 6.25, 12.5, and 25.0 μg/L) and the standard curves for both metals in both cohorts were comparable, with good correlation (R2 > 0.98 for all curves). Nonetheless, the total arsenic concentrations in cohort 2 from most of the whole blood, liver, and kidney samples and the total lead concentrations from most blood samples were below the LOD (5.0 ppb; Figure 2 A). Therefore, we chose to present the data from the 2 cohorts separately (Figure 2).

No significant intercohort differences were detected for arsenic in liver or kidneys; however the blood arsenic concentration was significantly (P < 0.05) higher in the saline group compared to the clay treated group in cohort 1. In cohort 2, a trend toward higher blood arsenic concentrations emerged in the clay-treated group, but most readings were below the LOD (Figure 2 A). There were no significant differences in blood lead concentrations in clay-treated and untreated mice in cohort 1, and blood lead levels in cohort 2 were below the LOD. The liver and kidney samples of the clay-treated mice from both cohorts had significantly (P < 0.05 for liver and P < 0.005 for kidney) higher concentrations of lead when compared with the saline-treated groups (Figure 2 B).

ALAD activity.

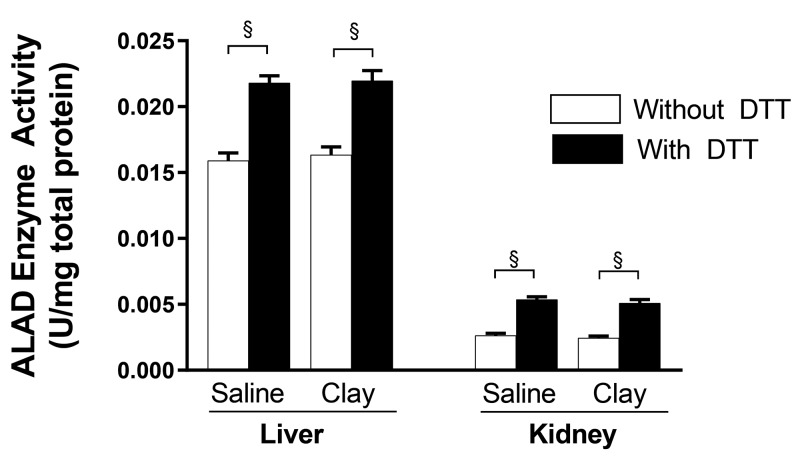

ALAD activity was measured with and without the addition of DTT to samples, to assess the extent of potential ALAD inhibition by lead. Liver and kidney samples from both cohorts were analyzed together. Although the addition of DTT resulted in the expected significant (P < 0.0001) increase in ALAD activity in samples of liver and kidney of both the saline- (n = 20 per tissue) and clay- (n = 20 per tissue) treated mice, activity did not differ between saline- and clay-treated groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) activity in liver (n = 20) and kidney (n = 20) before and after treatment with dithioth- reitol (DTT) to assess lead inhibition. Lead reversibly binds ALAD and inhibits activity. DTT releases bound ALAD and allows for measurement of total ALAD activity. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. §, P < 0.0001.

Discussion

UD in laboratory mice continues to be a perplexing issue for most animal research facilities. The multifactorial cause of this clinical disease makes viable treatment elusive. As responsible laboratory animal caregivers, we strive to provide quick and effective medical care. We also must aim to produce high-quality research through reliable study methods. Care must be taken to avoid the introduction of study variability through a procedure, biologic, or chemical used for clinical treatment. Therefore, prior to administration, any product or compound to which research animals may be exposed should be tested for natural or contaminating elements or chemicals that potentially can pose a health risk, alter physiologic responses, result in clinical toxicity, or confound results. Our study found high concentrations of both arsenic and lead in all brands of therapeutic clay tested, and although these high concentrations have been reported in some fields, (for example, mineralogy),44 we found the magnitude and variability of those concentrations to be surprising.34

The application of bentonite (green) clay for the treatment of UD is often used in laboratory mice, and although there is a wide variety in clay types, sources, mineral content, and distribution of potentially hazardous elements, we and others believed that the use of this natural product would have minimal physiologic effects.3,75 The current study shows that mice exposed to green clay applied topically once daily for 14 d remained healthy. Although treatment is topical, the clay-treated mice in this study ingested (through grooming) most of the applied clay soon after application. The rapid removal by grooming does raise a question regarding the utility of a topical treatment with a short contact time. Although many researchers report efficacies in the treatment of UD in mice, the aim of our current study was to address the biologic activity of arsenic and lead. Institutions should weigh the benefits and risks when considering using these products.

Although the route of exposure to the contaminating arsenic and lead is not necessarily a relevant factor in our study, we did measure total arsenic and lead concentrations in the treated skin of a subset of mice in cohort 1 and saw no differences. Given our observations, oral ingestion and gut absorption were the primary route of exposure in the current study. A previous review59 stated that the ingestion of potentially hazardous elements increased proportionately to the amount of healing clay ingested. As such, it is logical to expect that as the amount applied or application frequency increases, the clay ingested by mice will increase due to grooming, thereby elevating the potential risk of hazardous element exposure. The authors summarized that as the trace element concentrations from the clays increase, the element content in the organs also increases in the following order: kidney > liver > heart > brain.45,59 The ingestion of healing clays has also been linked to electrolyte-associated issues, such as fatigue and muscle impairment and gastrointestinal problems such as obstruction, constipation, diarrhea, and bloating in humans7,60,73 and cats.32,48 In the current study, we performed IVBA to estimate the proportions of the total amounts of arsenic and lead present in the clay that would likely be absorbed through the intestinal tract and become biologically available. Our results suggest that only 22% of the total arsenic and 43% of the total lead in the study clay was bioavailable.

ICP-MS has revealed that arsenic and lead are present in natural healing clays used for both medicinal4,36,44,53,55 and cosmetic purposes44,46,55 This information further supports our results demonstrating that healing clay products are naturally contaminated with high concentrations of toxic elements and that these products potentially could have harmful effects on treated animals. The US Pharmacopoeia limits for bentonite clay products are 40 ppm for lead and 5 ppm for arsenic.34,67-71 As expected, our current study demonstrated that diverse healing clay products are naturally contaminated with high concentrations of total arsenic and lead (Table 1). Interestingly however, despite the “ultra-pure pharmaceutical grade” label of one bentonite clay tested (brand 3), apparently none of the bentonite clays included in this study meet the standards for a pharmaceutical grade product. Arsenic is classified as a human carcinogen and occurs naturally as inorganic salts (AsO3, As2O3, As III or AsO43–, As2O5, As V) or as organic compounds (C5H11AsO2, C5H11AsO2).26,57,72 The inorganic forms of arsenic are considered much more toxic than the organic forms.57 Recent animal studies have shown that the ingestion of arsenic at levels as low as 50 ppb72 or even 10 ppb58 can result in detrimental biologic effects. In our study, we measured total arsenic in clay products (Table 1) and in the mice after multiple clay applications (Figure 2). Although the clay products tested contained elevated levels of arsenic, results from both cohorts showed no significant differences in liver or kidney arsenic levels between the clay paste and saline study groups; however, we did noted elevated arsenic concentrations in the blood of the saline-treated controls in cohort 1.

Although we cannot fully explain the differences observed in blood arsenic levels between the saline- and clay-exposure groups in cohort 1, we believe that the difference may be due to arsenic excretion rates. The half-life of inorganic arsenic in the blood is 4 to 6 h.47 Arsenic is not taken up by tissues (consequently leading to the similar liver and kidney levels) but is filtered from the blood and rapidly excreted through urine. The ingestion of high levels of arsenic in the green clay–treated group could result in the activation of excretory pathways and arsenic transporters, such as multidrug-resistant P-glycoproteins, leading to more rapid efflux of arsenic and therefore lower measured blood arsenic levels.40 The collection and testing of urine and feces at earlier time points for determining arsenic excretion in future studies could prove to be informative.

Whereas arsenic is rapidly excreted, lead accumulates within tissues, especially liver, kidney, brain, and bone.14,17,23 Recently, the US FDA has warned consumers of the potential risk of lead poisoning due to elevated levels of lead in 2 types of widely available bentonite clay products often used for medicinal purposes.61,62 Our study demonstrated that daily application of a French green healing clay resulted in significant increases in total liver and kidney lead levels, when compared with control mice (Figure 2).

One acute effect of lead toxicity is the inhibition of ALAD and ferrochelatase, both involved in heme biosynthesis, which can result in anemia.47 Heme is a porphyrin-based protein that coordinates with iron and primarily functions in mammalian cells to carry oxygen. Heme synthesis is dependent on the enzyme ALAD and its ability to use ALA and convert it into porphobilinogen. ALAD activity in erythrocytes is inhibited by lead exposure, and measurement of enzymatic activity in blood and tissues such as the kidney, liver, and spleen is one of the most highly sensitive ways to determine either chronic or acute subclinical lead poisoning in mammals.18,25 As such, ALAD activity is clinically used to diagnose lead toxicity.18 In this study, we observed a significant (P < 0.05) increase in ALAD activity within the saline- and clay-treated groups after DTT treatment. This expected increase has also been reported in humans with the fold change rarely exceeding 2-fold whereas, the restoration of in vitro ALAD activity on DTT treatment in cases of lead toxicity generally is associated with greater than 8-fold increases in activity.28 We found no significant difference in hepatic or renal ALAD activity or reactivation after the addition of DTT (zinc) between the 2 groups (Figure 3), thereby indicating no biologic effect on heme biosynthesis from the clay treatment. In addition to binding to and inhibiting ALAD in multiple tissues, lead is known to bind to several proteins in both kidney and brain. In kidney, lead binds to a cleaved form of α2 microglobulin, thus leading to cellular injury in various nephrons and specific regions of the proximal tubules.24 Additional studies could be expanded through earlier, more frequent collection and testing of samples of whole blood, spleen, and urine for increased levels of ALA excretion due to lead exposure.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that 3 brands of commercially available healing clay products are naturally contaminated with high levels of arsenic and lead. Despite being unable to demonstrate any significant biologic effects, one brand that has the potential to cause harmful effects when entering the body showed a significant increase in the concentration of lead accumulation in the liver and kidneys of clay-treated mice compared with controls. For this reason, we discourage the use of natural healing clays in studies of lead toxicity, heme biosynthesis, or α2 microglobulin function. In other studies, the use of therapeutic clay products such as bentonite green clay should be considered carefully to minimize the potential for introducing unwanted variability.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Alpha/Omega and FEFA animal care staff for their exemplary care of the mice during this study. We acknowledge Drs Sheeba Churchill and Kristen Ryan of the Cellular and Molecular Pathology Branch and the Toxicology Branch at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) for manuscript review; Dr Caleb Sutherland and the Immunity, Inflammation, and Disease Lab at the NIEHS for providing technical assistance; and Mr Steve McCaw (Image Associates, Durham, NC) for photography. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIEHS.

References

- 1.Adamis Z, Williams RB. International Program on Chemical Safety. 2005. Bentonite, kaolin, and selected clay minerals. Environmental health criteria, 231. Geneva: World Health Organization; https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43102 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams SC, Garner JP, Felt SA, Geronimo JT, Chu DK. 2016. A “Pedi” cures all: toenail trimming and the treatment of ulcerative dermatitis in mice. PLoS One 11:1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afriyie-Gyawu E, Mackie J, Dash B, Wiles M, Taylor J, Huebner H, Tang L, Guan H, Wang JS, Phillips T. 2005. Chronic toxicological evaluation of dietary NovaSil clay in Sprague-Dawley rats. Food Addit Contam 22:259–269. 10.1080/02652030500110758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Rmalli SW, Jenkins RO, Watts MJ, Haris PI. 2010. Risk of human exposure to arsenic and other toxic elements from geophagy: trace element analysis of baked clay using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Environ Health 9:1–8. 10.1186/1476-069X-9-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarado CG, Franklin CL, Dixon LW. 2016. Retrospective evaluation of nail trimming as a conservative treatment for ulcerative dermatitis in laboratory mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 55:462–466. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnard D, Starost M, Teter B, Yoshizumi E, Sampugna J, Morse B, Foltz C. 2006. Dietary effects on the development of ulcerative dermatitis in C57BL/6J mice. Abstracts presented at the 2006 AALAS National Meeting, Salt Lake City, Utah, 15–19 October 2006. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 45:115–116. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett A, Stryjewski G. 2006. Severe hypokalemia caused by oral and rectal administration of bentonite in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Emerg Care 22:500–502. 10.1097/01.pec.0000227873.05119.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergaya F, Lagaly G. 2013. Chapter 1 General introduction: Clays, clay minerals, and clay science. In: Bergaya F, Theng BKG, Lagaly G. Handbook of Clay Science, vol 11–18. 10.1016/S1572-4352(05)01001-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradham KD, Diamond GL, Scheckel KG, Hughes MF, Casteel SW, Miller BW, Klotzbach JM, Thayer WC, Thomas DJ. 2013. Mouse assay for determination of arsenic bioavailability in contaminated soils. J Toxicol Environ Health A 76:815–826. 10.1080/15287394.2013.821395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradham KD, Green W, Hayes H, Nelson C, Alava P, Misenheimer J, Diamond GL, Thayer WC, Thomas DJ. 2016. Estimating relative bioavailability of soil lead in the mouse. J Toxicol Environ Health A 79:1179–1182. 10.1080/15287394.2016.1221789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradham KD, Nelson C, Juhasz AL, Smith E, Scheckel K, Obenour DR, Miller BW, Thomas DJ. 2015. Independent data validation of an in vitro method for the prediction of the relative bioavailability of arsenic in contaminated soils. Environ Sci Technol 49:6312–6318. 10.1021/acs.est.5b00905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradham KD, Scheckel KG, Nelson CM, Seales PE, Lee GE, Hughes MF, Miller BW, Yeow A, Gilmore T, Serda SM, Harper S, Thomas DJ. 2011. Relative bioavailability and bioaccessibility and speciation of arsenic in contaminated soils. Environ Health Perspect 119:1629–1634. 10.1289/ehp.1003352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callan T, Matherly C, Ogbin J, Kusznir T. 2012. Comparison of the Healing Effects of Manuka Honey and Bentonite Clay on Skin Ulcerations in Laboratory Mice (Mus musculus). Abstracts presented at the 2012 AALAS National Meeting, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 4–8 November 2012. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 51:665. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canfield RL, Henderson CR, Jr, Cory-Slechta DA, Cox C, Jusko TA, Lanphear BP. 2003. Intellectual impairment in children with blood lead concentrations below 10 microg per deciliter. N Engl J Med 348:1517–1526. 10.1056/NEJMoa022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carretero MI. 2002. Clay minerals and their beneficial effects upon human health. A review. Appl Clay Sci 21:155–163. 10.1016/S0169-1317(01)00085-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carretero MI, Pozo M. 2010. Clay and non-clay minerals in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries Part II. Active ingredients. Appl Clay Sci 47:171–181. 10.1016/j.clay.2009.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Internet]. 2012. Low level lead exposure harms children: a renewed call for primary prevention. [ Cited 07 May 2015]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/acclpp/final_document_030712.pdf

- 18.Chisolm JJ, Jr, Thomas DJ, Hamill TG. 1985. Erythrocyte porphobilinogen synthase activity as an indicator of lead exposure in children. Clin Chem 31:601–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crowley M, Delano M, Kirchain S. 2008. Successful treatment of C57BL/6 ulcerative dermatitis with caladryl lotion. Abstracts presented at the 2008 AALAS National Meeting, Indianapolis, Indiana, 9–13 November 2008. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 47:109–110. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dário GM, da Silva GG, Goncalves DL, Silveira P, Junior AT, Angioletto E, Bernardin AM. 2014. Evaluation of the healing activity of therapeutic clay in rat skin wounds. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 43:109–116. 10.1016/j.msec.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emami-Razavi SH, Esmaeili N, Forouzannia SK, Amanpour S, Rabbani S, Alizadeh AM, Mohagheghi MA. 2006. Effect of bentonite on skin wound healing: experimental study in the rat model. Acta Med Iran 44:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ezell PC, Papa L, Lawson GW. 2012. Palatability and treatment efficacy of various ibuprofen formulations in C57BL/6 mice with ulcerative dermatitis. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 51:609–615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flora G, Gupta D, Tiwari A. 2012. Toxicity of lead: a review with recent updates. Interdiscip Toxicol 5:47–58. 10.2478/v10102-012-0009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fowler BA, DuVal G. 1991. Effects of lead on the kidney: roles of high-affinity lead-binding proteins. Environ Health Perspect 91:77–80. 10.1289/ehp.919177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujita H. 2001. Measurement of δ-aminolevulinate dehydratase activity. Curr Protoc Toxicol Chapter 8:8.6.1–8.6.11. 10.1002/0471140856.tx0806s01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.García-Montalvo EA, Valenzuela OL, Sánchez-Peña LC, Albores A, Del Razo LM. 2011. Dose-dependent urinary phenotype of inorganic arsenic methylation in mice with a focus on trivalent methylated metabolites. Toxicol Mech Methods 21:649–655. 10.3109/15376516.2011.603765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaskell EE, Hamilton AR. 2014. Antimicrobial clay-based materials for wound care. Future Med Chem 6:641–655. 10.4155/fmc.14.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granick JL, Sassa S, Granick S, Levere RD, Kappas A. 1973. Studies in lead poisoning. II. Correlation between the ratio of activated to inactivated δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase of whole blood and the blood lead level. Biochem Med 8:149–159. 10.1016/0006-2944(73)90018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granick S, Sassa S, Granick JL, Levere RD, Kappas A. 1972. Assays for porphyrins, delta-aminolevulinic-acid dehydratase, and porphyrinogen synthetase in microliter samples of whole blood: applications to metabolic defects involving the heme pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 69:2381–2385. 10.1073/pnas.69.9.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haahr M. [Internet]. 2014. RANDOM.ORG. [Cited 17 September 2014]. Available at: https://www.random.org/sequences/.

- 31.Haydel SE, Remenih CM, Williams LB. 2007. Broad-spectrum in vitro antibacterial activities of clay minerals against antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:353–361. 10.1093/jac/dkm468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hornfeldt CS, Westfall ML. 1996. Suspected bentonite toxicosis in a cat from ingestion of clay cat litter. Vet Hum Toxicol 38:365–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. [Internet]. 2004. Some drinking-water disinfectants and contaminants, including arsenic, vol 84. p 1–477. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; [Cited 12 February 2016]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK402251/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iborra CV, Cultrone G, Cerezo P, Aguzzi C, Baschini MT, Vallés J, López-Galindo A. 2006. Characterisation of northern Patagonian bentonites for pharmaceutical uses. Appl Clay Sci 31:272–281. 10.1016/j.clay.2005.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalguem EDK. 2019. Geophagic clayey materials of Sabga Locality (North West Cameroon): genesis and medical interest. Earth Sciences 8:45–59. 10.11648/j.earth.20190801.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kastenmayer RJ, Fain MA, Perdue KA. 2006. A retrospective study of idiopathic ulcerative dermatitis in mice with a C57BL/6 background. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 45:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khurana IS, Kaur S, Kaur H, Khurana RK. 2015. Multifaceted role of clay minerals in pharmaceuticals. Future Sci OA 1:FSO6 10.4155/fso.15.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawson GW, Sato A, Fairbanks LA, Lawson PT. 2005. Vitamin E as a treatment for ulcerative dermatitis in C57BL/6 mice and strains with a C57BL/6 background. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 44:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J, Liu Y, Powell DA, Waalkes MP, Klaassen CD. 2002. Multidrug-resistance mdr1a/1b double knockout mice are more sensitive than wild type mice to acute arsenic toxicity, with higher arsenic accumulation in tissues. Toxicology 170:55–62. 10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.López-Galindo A, Viseras C, Cerezo P. 2007. Compositional, technical and safety specifications of clays to be used as pharmaceutical and cosmetic products. Appl Clay Sci 36:51–63. 10.1016/j.clay.2006.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lumpkins K, Swing S, Emerson C, Ali F, Van Andel R. 2006. Efficacy of topical chlorhexidine for treatment of ulcerative dermatitis in C57BL/6 mice. Abstracts presented at the 2006 AALAS National Meeting, Salt Lake City, Utah, 15–19 October 2006. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 45:94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martel N, Careau C. 2011. Green clay therapy for mice topical dermatitis. Tech Talk 16:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mascolo N, Summa V, Tateo F. 1999. Characterization of toxic elements in clays for human healing use. Appl Clay Sci 15:491–500. 10.1016/S0169-1317(99)00037-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mascolo N, Summa V, Tateo F. 2004. In vivo experimental data on the mobility of hazardous chemical elements from clays. Appl Clay Sci 25:23–28. 10.1016/j.clay.2003.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mattioli M, Giardini L, Roselli C, Desideri D. 2016. Mineralogical characterization of commercial clays used in cosmetics and possible risk for health. Appl Clay Sci 119:449–454. 10.1016/j.clay.2015.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayo Clinic Medical Laboratories. [Internet]. 2019. Heavy metals screen with demographics, blood - clinical information [Cited 31 May 2015]. Available at: https://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Clinical+and+Interpretive/34506

- 48.McDonough S. 1997. Bentonite toxicosis in a cat from cat litter? Vet Hum Toxicol 39:181–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mockovc˘iaková A, Orolínová Z. 2009. Adsorption properties of modified bentonite clay. Cheminé Technologija 1:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moghadamzadeh HR, Naimi M, Rahimzadeh H, Ardjmand M, Nansa VM, Ghanadi AM. 2013. Experimental study of adsorption properties of acid and thermal treated bentonite from Tehran (Iran). Int J Eng Technol Sci Innov 7:425–429. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morrison KD, Misra R, Williams LB. 2016. Unearthing the antibacterial mechanism of medicinal clay: a geochemical approach to combating antibiotic resistance. Sci Rep 6:1–13. 10.1038/srep19043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mufford T, Richardson L. 2009. Nail trims versus the previous standard of care for treatment of mice with ulcerative dermatitis. Abstracts presented at the 2009 AALAS National Meeting, Denver, Colorado, 8–12 November 2009. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 48:546. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nkansah MA, Korankye M, Darko G, Dodd M. 2016. Heavy metal content and potential health risk of geophagic white clay from the Kumasi Metropolis in Ghana. Toxicol Rep 3:644–651. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Otto CC, Haydel SE. 2013. Exchangeable ions are responsible for the in vitro antibacterial properties of natural clay mixtures. PLoS One 8:1–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papadopoulos A, Giouri K, Tzamos E, Filippidis A, Stoulos S. 2014. Natural radioactivity and trace element composition of natural clays used as cosmetic products in the Greek market. Clay Miner 49:53–62. 10.1180/claymin.2014.049.1.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips TD, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Williams J, Huebner H, Ankrah NA, Ofori-Adjei D, Jolly P, Johnson N, Taylor J, Marroquin-Cardona A, Xu L, Tang L, Wang JS. 2008. Reducing human exposure to aflatoxin through the use of clay: a review. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 25:134–145. 10.1080/02652030701567467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ratnaike RN. 2003. Acute and chronic arsenic toxicity. Postgrad Med J 79:391–396. 10.1136/pmj.79.933.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodriguez KF, Ungewitter EK, Crespo-Mejias Y, Liu C, Nicol B, Kissling GE, Yao HH. 2016. Effects of in utero exposure to arsenic during the second half of gestation on reproductive end points and metabolic parameters in female CD1 mice. Environ Health Perspect 124:336–343. 10.1289/ehp.1509703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tateo F, Summa V. 2007. Element mobility in clays for healing use. Appl Clay Sci 36:64–76. 10.1016/j.clay.2006.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ukaonu C, Hill DA, Christensen F. 2003. Hypokalemic myopathy in pregnancy caused by clay ingestion. Obstet Gynecol 102:1169–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.United States Food and Drug Administration. [Internet]. 2016. FDA warns consumers about health risks with alikay naturals-bentonite me baby-bentonite clay. [Cited 12 October 2017]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-consumers-about-health-risks-alikay-naturals-bentonite-me-baby-bentonite-clay.

- 62.United States Food and Drug Administration. [Internet]. 2016. FDA warns consumers not to use “Best Bentonite Clay”. [Cited 12 October 2017]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-consumers-not-use-best-bentonite-clay.

- 63.US Environmental Protection Agency. [Internet]. 2007. SW-846 Test Method 3051A: Microwave assisted acid digestion of sediments, sludges, soils, and oils. [Cited 26 September 2018]. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-test-method-3051a-microwave-assisted-acid-digestion-sediments-sludges-soils-and-oils.

- 64.US Environmental Protection Agency. 2012. Standard operating procedure for an in vitro bioaccessibility assay for lead in soil. [Cited 26 September 2018]. Available at: https://nepis.epa.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 65.US Environmental Protection Agency. [Internet]. 2014. SW-846 Test Method 6020B: Inductively coupled plasma - mass spectrometry. [Cited 26 September 2018]. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-test-method-6020b-inductively-coupled-plasma-mass-spectrometry

- 66.US Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. SW-846 Test Method 1340: In vitro bioaccessibility assay for lead in soil. [Cited 26 September 2018]. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-test-method-1340-vitro-bioaccessibility-assay-lead-soil. [Google Scholar]

- 67.US Pharmacopeia. 2004. Bentonite, p 2826. US Pharmacopeia 27. US Pharmacopeial Convention. Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 68.US Pharmacopeia. 2004. Purified Bentonite, p 2827–2828. US Pharmacopeia 27. US Pharmacopeial Convention; Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 69.US Pharmacopeia. 2006. Bentonite, p 3278–3279. US Pharmacopeia 29-NF 24. US Pharmacopeial Convention; Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 70.US Pharmacopeia. 2006. Bentonite magma, p 3280–3281. US Pharmacopeia 29-NF 24. US Pharmacopeial Convention; Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 71.US Pharmacopeia. 2006. Purified Bentonite, p 3279–3280. US Pharmacopeia 29-NF 24. Rockville (MD): US Pharmacopeial Convention. Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waalkes MP, Qu W, Tokar EJ, Kissling GE, Dixon D. 2014. Lung tumors in mice induced by “whole-life” inorganic arsenic exposure at human-relevant doses. Arch Toxicol 88:1619–1629. 10.1007/s00204-014-1305-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang JS, Luo H, Billam M, Wang Z, Guan H, Tang L, Goldston T, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Lovett C, Griswold J, Brattin B, Taylor RJ, Huebner HJ, Phillips TD. 2005. Short-term safety evaluation of processed calcium montmorillonite clay (NovaSil) in humans. Food Addit Contam 22:270–279. 10.1080/02652030500111129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang P, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Tang Y, Johnson NM, Xu L, Tang L, Huebner HJ, Ankrah NA, Ofori-Adjei D, Ellis W, Jolly PE, Williams JH, Wang JS, Phillips TD. 2008. NovaSil clay intervention in Ghanaians at high risk for aflatoxicosis: II. Reduction in biomarkers of aflatoxin exposure in blood and urine. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 25:622–634. 10.1080/02652030701598694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wiles M, Huebner H, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Taylor R, Bratton G, Phillips T. 2004. Toxicological evaluation and metal bioavailability in pregnant rats following exposure to clay minerals in the diet. J Toxicol Environ Health A 67:863–874. 10.1080/15287390490425777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams-Fritze MJ, Carlson Scholz JA, Zeiss C, Deng Y, Wilson SR, Franklin R, Smith PC. 2011. Maropitant citrate for treatment of ulcerative dermatitis in mice with a C57BL/6 background. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 50:221–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams LB, Haydel SE. 2010. Evaluation of the medicinal use of clay minerals as antibacterial agents. Int Geol Rev 52:745–770. 10.1080/00206811003679737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams LB, Haydel SE, Giese RF, Jr, Eberl DD. 2008. Chemical and mineralogical characteristics of french green clays used for healing. Clays Clay Miner 56:437–452. 10.1346/CCMN.2008.0560405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams LB, Metge DW, Eberl DD, Harvey RW, Turner AG, Prapaipong P, Poret-Peterson AT. 2011. What makes a natural clay antibacterial? Environ Sci Technol 45:3768–3773. 10.1021/es1040688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]