Abstract

Background

Very high blood pressure during pregnancy poses a serious threat to women and their babies. The aim of antihypertensive therapy is to lower blood pressure quickly but safety, to avoid complications. Antihypertensive drugs lower blood pressure but their comparative effectiveness and safety, and impact on other substantive outcomes is uncertain.

Objectives

To compare different antihypertensive drugs for very high blood pressure during pregnancy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Trials Register (9 January 2013).

Selection criteria

Studies were randomised trials. Participants were women with severe hypertension during pregnancy. Interventions were comparisons of one antihypertensive drug with another.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and assessed trial quality. Two review authors extracted data and checked them for accuracy.

Main results

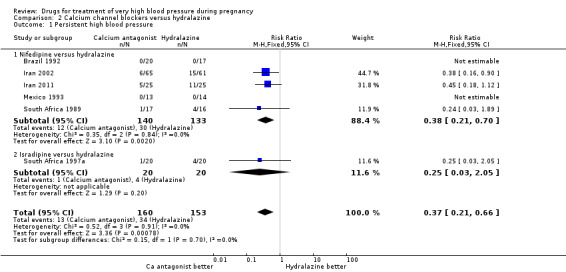

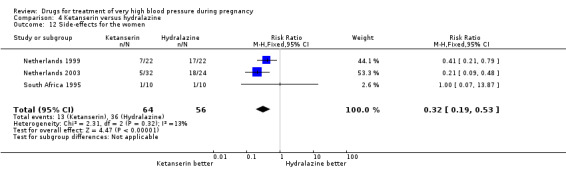

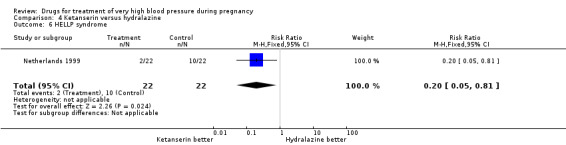

Thirty‐five trials (3573 women) with 15 comparisons were included. Women allocated calcium channel blockers were less likely to have persistent high blood pressure compared to those allocated hydralazine (six trials, 313 women; 8% versus 22%; risk ratio (RR) 0.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.21 to 0.66). Ketanserin was associated with more persistent high blood pressure than hydralazine (three trials, 180 women; 27% versus 6%; RR 4.79, 95% CI 1.95 to 11.73), but fewer side‐effects (three trials, 120 women; RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.53) and a lower risk of HELLP (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and lowered platelets) syndrome (one trial, 44 women; RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.81).

Labetalol was associated with a lower risk of hypotension compared to diazoxide (one trial 90 women; RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.99) and a lower risk of caesarean section (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.02), although both were borderline for statistical significance.

Both nimodipine and magnesium sulphate were associated with a high incidence of persistent high blood pressure, but this risk was lower for nimodipine compared to magnesium sulphate (one trial, 1650 women; 47% versus 65%; RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.93). Nimodipine was associated with a lower risk of respiratory difficulties (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.99), fewer side‐effects (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.85) and less postpartum haemorrhage (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.92) than magnesium sulphate. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths were not reported.

There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of any other drugs.

Authors' conclusions

Until better evidence is available the choice of antihypertensive should depend on the clinician's experience and familiarity with a particular drug; on what is known about adverse effects; and on women's preferences. Exceptions are nimodipine, magnesium sulphate (although this is indicated for women who require an anticonvulsant for prevention or treatment of eclampsia), diazoxide and ketanserin, which are probably best avoided.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Antihypertensive Agents; Antihypertensive Agents/adverse effects; Antihypertensive Agents/therapeutic use; Calcium Channel Blockers; Calcium Channel Blockers/adverse effects; Calcium Channel Blockers/therapeutic use; Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced; Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced/drug therapy; Pre‐Eclampsia; Pre‐Eclampsia/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Drugs for treatment of very high blood pressure during pregnancy

Pregnant women with very high blood pressure (hypertension) can reduce their blood pressure with antihypertensive drugs, but the most effective antihypertensive drug during pregnancy is unknown. The aim of antihypertensive therapy is to lower blood pressure quickly but safely for both the mother and her baby, avoiding sudden drops in blood pressure that can cause dizziness or fetal distress.

During pregnancy, a woman's blood pressure falls in the first few weeks then rises again slowly from around the middle of pregnancy, reaching pre‐pregnancy levels at term. Pregnant women with very high blood pressure (systolic over 160 mmHg, diastolic 110 mmHg or more) are at risk of developing pre‐eclampsia with associated kidney failure and premature delivery, or of having a stroke. The review of 35 randomised controlled trials including 3573 women (in the mid to late stages of pregnancy, where stated) found that while antihypertensive drugs are effective in lowering blood pressure, there is not enough evidence to show which drug is the most effective. Fifteen different comparisons of antihypertensive treatments were included in these 35 trials, which meant that some comparisons were made by single trials. Only one trial had a large number of participants. This trial compared nimodipine with magnesium sulphate and showed that high blood pressure persisted in 47% and 65% of women, respectively. Calcium channel blockers were associated with less persistent hypertension than with hydralazine and possibly less side‐effects compared to labetalol. There is some evidence that diazoxide may result in a woman's blood pressure falling too quickly, and that ketanserin may not be as effective as hydralazine. Further research into the effects of antihypertensive drugs during pregnancy is needed.

Background

Description of the condition

During normal pregnancy there are considerable changes in blood pressure. Within the first weeks the woman's blood pressure falls, largely due to a general relaxation of muscles within the blood vessels (de Swiet 2002). Cardiac output also increases. From around the middle of pregnancy blood pressure slowly rises again until, at term, blood pressure is close to the level it was before pregnancy. Blood pressure during pregnancy can be influenced by many other factors including, time of day, physical activity, position and anxiety. Modest rises in blood pressure alone may have little effect on the outcome of pregnancy, but high blood pressure is often associated with other complications. Of these, the most common is pre‐eclampsia. This is a multisystem disorder of pregnancy which commonly presents with raised blood pressure and proteinuria (Roberts 2009), and occurs in between two to eight per cent of pregnancies (WHO 1988). Although the outcome for most of these pregnancies is good, women with pre‐eclampsia have an increased risk of developing serious problems, such as kidney failure, liver failure, abnormalities of the clotting system, stroke, premature delivery (birth before 37 completed weeks), stillbirth or death of the baby in the first few weeks of life (Tuffnell 2006).

In view of the many factors that can influence blood pressure, it is not surprising that there is often uncertainty about whether a specific abnormal measurement is potentially harmful for that woman. Once blood pressure rises above a certain level, however, there is a risk of direct damage to the blood vessel wall, regardless of what caused the rise. This risk is not specific to pregnancy, as it is similar for non‐pregnant people with very high blood pressure. The level at which this risk merits mandatory antihypertensive therapy is usually considered to be 170 mmHg systolic blood pressure or 110 mmHg diastolic (Tuffnell 2006). If the woman has signs and symptoms associated with severe pre‐eclampsia (such as hyperreflexia, severe headache, sudden onset of epigastric pain, or lowered platelets) a lower threshold for treatment may be recommended (CEMD‐UK 2011). The possible consequences of such high blood pressure for the mother include kidney failure, liver failure and cerebrovascular haemorrhage (stroke). In the UK, for example, stoke resulting from severe hypertension was the single most common cause of maternal death associated with pre‐eclampsia (CEMD‐UK 2011). For the baby, risks include fetal distress due to impaired blood supply across the placenta, and placental abruption (separation of the placenta from the wall of the womb before birth).

Description of the intervention

Once blood pressure reaches 170 mmHg systolic or 110 mmHg diastolic, the woman is at increased risk of harmful effects. There is therefore a general consensus that she should receive antihypertensive drugs, to lower her blood pressure, and that she should be in a hospital. The aim of treatment is to quickly bring about a smooth reduction in blood pressure to levels that are safe for both mother and baby, but avoiding any sudden drops that may in themselves cause problems such as dizziness or fetal distress.

A wide range of antihypertensive drugs have been compared for management of severe hypertension during pregnancy. The most commonly recommended drugs include hydralazine, labetalol and nifedipine (Lindheimer 2008; Lowe 2009; Magee 2008; NICE 2010; WHO 2011) and there is most experience with these.

In general, maternal side‐effects are not different from those in the non‐pregnant state, and are listed in pharmacological texts. All drugs used to treat hypertension in pregnancy cross the placenta, and so may affect the fetus directly by means of their action within the fetal circulation, or indirectly by their effect on uteroplacental perfusion.

The care of women with very high blood pressure during pregnancy is often complex.For women who have pre‐eclampsia, there is also the question of whether there is additional benefit from prophylactic anticonvulsant drugs, and this question is covered in the review 'Anticonvulsants for women with pre‐eclampsia' (Duley 2010). In addition, other Cochrane reviews relevant to the care of women with severe hypertension include plasma volume expansion (Duley 1999), and steroids for HELLP (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and lowered platelets) syndrome (Woudstra 2010). Once blood pressure is controlled, in many cases a decision will be made to deliver the baby fairly soon, particularly if the pregnancy is at or near to term. If the baby is very premature, the blood pressure responds well to initial treatment, and there are no other complicating factors, the pregnancy may be continued with the hope that this will improve outcome for the baby. This issue of timing of delivery for severe pre‐eclampsia before 34 weeks' gestation is covered by a separate review (Churchill 2002). Treatment of mild to moderate hypertension in pregnancy has been reviewed by Abalos 2007.

Why it is important to do this review

Very high blood pressure needs to be lowered to protect the woman. This needs to be done in a controlled manner, to avoid complications for the mother and baby, While all antihypertensive drugs lower blood pressure, their comparative benefits and adverse effects when used for very high blood pressure during pregnancy remain uncertain.

The aim of this review is to compare the different types of antihypertensive drugs used for women with severe hypertension during pregnancy to determine which agent has the greatest comparative benefit with the least risk.

Objectives

To compare the effects of different antihypertensive drugs when used to lower very high blood pressure during pregnancy on:

substantive maternal morbidity;

morbidity and mortality for the baby;

side‐effects for the woman.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials were included. Studies with clearly inadequate concealment of allocation were excluded, as were those with a quasi‐random or cross‐over design.

Cluster‐randomised studies designs are unlikely to be relevant to most interventions for treatment of women with high blood pressure, and are therefore unlikely to be identified. If such studies have been conducted, they will not be automatically excluded, rather, the relevant review authors will consider and justify whether or not it is appropriate to include them.

Studies presented only as abstract were considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

Women with severe hypertension (defined whenever possible as diastolic 105 mmHg or more and/or systolic 160 mmHg or more) during pregnancy, requiring immediate treatment. Women postpartum at trial entry were excluded, as the outcomes of interest for these women are substantially different.

Types of interventions

Any comparison of one antihypertensive drug with another regardless of dose, route of administration or duration of therapy. Comparisons of alternative regimens for the same drug and of alternatives within the same class of drug are not included, but may be considered for future updates.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

For the woman

Death: death during pregnancy or up to 42 days after end of pregnancy, or death more than 42 days after the end of pregnancy

Eclampsia (seizures superimposed on pre‐eclampsia), or recurrence of seizures

Stroke

Persistent high blood pressure: defined, if possible, as either the need for an antihypertensive drug other than the allocated treatment, or failure to control blood pressure on the allocated treatment

For the child

Death: stillbirths (death in utero at or after 20 weeks' gestation), perinatal deaths (stillbirths plus deaths in the first week of life), death before discharge from hospital, neonatal deaths (death in the first 28 days after birth), deaths after the first 28 days

Secondary outcomes

For the woman

Any serious morbidity: defined as at least one of stroke, kidney failure, liver failure, HELLP syndrome (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets syndrome), disseminated intravascular coagulation, pulmonary oedema (fluid in the lungs)

Kidney failure

Liver failure

HELLP syndrome

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Pulmonary oedema (fluid in the lungs)

Hypotension (low blood pressure): defined if possible as low blood pressure causing clinical problems

Side‐effects of the drug

Abruption of the placenta or antepartum haemorrhage

Need for magnesium sulphate (added in the 2013 update)

Elective delivery: induction of labour or caesarean section

Caesarean section: emergency and elective

Postpartum haemorrhage: defined as blood loss of 500 mL or more

Use of hospital resources: visit to day care unit, antenatal hospital admission, intensive care (admission to intensive care unit, length of stay) ventilation, dialysis

Postnatal depression

Breastfeeding, at discharge and up to one year after the birth

Women's experiences and views of the interventions: childbirth experience, physical and psychological trauma, mother‐infant interaction and attachment

For the child

Preterm birth: defined as birth before 37 completed weeks' gestation, very preterm birth (before 32 to 34 completed weeks) and extremely preterm birth (before 26 to 28 completed weeks)

Death before discharge from hospital or in a special care nursery for more than seven days

Respiratory distress syndrome

Infection

Necrotising enterocolitis

Retinopathy of prematurity

Intraventricular haemorrhage

Apgar score at five minutes: low (less than seven) and very low (less than four) or lowest reported

Side‐effects associated with the drug

In a special care nursery for more than seven days

Use of hospital resources: admission to special care nursery, length of stay, endotracheal intubation, use of mechanical ventilation

Long‐term growth and development: blindness, deafness, seizures, poor growth, neurodevelopmental delay and cerebral palsy

Economic outcomes

Costs to health service resources: short term and long term for both mother and baby

Costs to the woman, her family, and society

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (9 January 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of Embase;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

For details of searching carried out in earlier versions of this review, please seeAppendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 2.

For this update we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we will consulted a third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

Studies with high risk of bias for allocation concealment were excluded.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We will assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups; ≦ 20% participants missing);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; > 20% participants missing);

unclear risk of bias.

If it was not possible to enter data based on intention‐to‐treat or 20% or more participants were excluded from the analysis of that outcome, then the trial was excluded.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we planned to use the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials and the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Although cluster‐randomised trials of interventions for treatment of very high blood pressure are unlikely, if identified in future updates and they meet all other eligibility criteria, they will be included along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were excluded.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we planned to discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials.

If we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future updates, if we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

Data are presented by class of drug. In addition, the following subgroup analyses will be conducted when sufficient data become available:

treatment regimen within each class of drug;

whether severe hypertension alone, or severe hypertension plus proteinuria at trial entry.

The subgroup analysis will be restricted to the review’s primary outcomes.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2011). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the χ2 statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

When appropriate, in future updates, we will carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality based on concealment of allocation, by excluding studies with unclear allocation concealment.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Thirty nine trial reports were identified from the updated search (2013). The review now includes: a total of 35 trials (Argentina 1990; Australia 1986; Australia 2007; Brazil 1992; Brazil 1994; Brazil 2011; England 1982; France 2010; Germany 1998; Germany 2006; India 2006; India 2011; Iran 2002; Iran 2011; Malaysia 2012; Mexico 1989; Mexico 1993; Mexico 1998; Netherlands 1999; Netherlands 2003; Nimodipine SG 2003; N Ireland 1991; Panama 2006; South Africa 1987; South Africa 1989; South Africa 1992; South Africa 1995; South Africa 1997; South Africa 1997a; South Africa 1997b; South Africa 2000; Switzerland 2012; Tunisia 2002; Turkey 1996; USA 1987); 65 trials are excluded (Adair 2009; Adair 2010; Anonymous 2006; Argentina 1986; Aslam 2007; Australia 2002; Bangladesh 2002; Belfort 2006; Brazil 1984; Brazil 1988; Brazil 1988a; China 2000; Devi 2012; Egerman 2008; Egypt 1988; Egypt 1989; Egypt 1992; Esmaoglu 2009; France 1986; Ghana 1995; Graves 2012; Gris 2011; Hladunewich 2006; Hopate 2008; India 1963; India 2001; Iran 1994; Israel 1991; Israel 1999; Italy 2004; Jamaica 1999; Japan 1999; Japan 2000; Japan 2002; Japan 2003; Johnston 2006; Lam 2008; Malaysia 1996; Manzur‐Verastegui 2008; Mexico 1967; Mexico 2000; Mexico 2004; Netherlands 2002; New Zealand 1986; New Zealand 1992; Philipines 2000; Pogue 2006; Roes 2006; Samangaya 2009; Schackis 2004; Scotland 1983; Singapore 1971; Smith 2005; South Africa 1982; South Africa 1984; South Africa 1993; South Africa 2002; Spain 1988; Steyn 2003; Sweden 1993; Unemori 2009; USA 1999; Venezuela 2001; Waheed 2005; Warren 2004); one trial is ongoing (Diemunsch 2008); and one trial (Mesquita 1995) is awaiting assessment.

Included studies

The review includes 35 trials into which 3573 women were recruited. All the trials were small, apart from one large study (1750 women) comparing nimodipine with magnesium sulphate (Nimodipine SG 2003) The women had very high blood pressure; almost all had diastolic blood pressure 110 mmHg or above at trial entry. Nine studies (2292 women) also stated that the women had either 'proteinuria' or 'pre‐eclampsia' as an inclusion criterion. Several trials specified a minimum gestational age for recruitment, and this ranged from 20 weeks to 36 weeks. Others stated that delivery was planned for soon after treatment. One small trial (30 women) (N Ireland 1991) had minimum entry criteria of a blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg but was included as most women were stated to have had labile blood pressure, proteinuria and symptoms. Another study included 150 women for whom first line therapy with methyldopa had not been successful (South Africa 2000).

The antihypertensive drugs evaluated in these trials were hydralazine, calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, nimodipine, nicardipine and isradipine), labetalol, atenolol, methyldopa, diazoxide, prostacyclin, ketanserin, urapidil, magnesium sulphate, prazosin and isosorbide. There are 15 comparisons in the review. Hydralazine was the most common comparator, being compared with another drug (labetalol, calcium channel blockers, prostacyclin, diazoxide, ketanserin or rapidil) in six comparisons. Most drugs were given either intravenously (IV) or intramuscularly (IM) except nifedipine, nimodipine, isosorbide and prazosin which were given orally. Dosage varied considerably between studies, in both amount and duration of therapy.

The primary hypothesis for the one large study (Nimodipine SG 2003) was to compare the effects on prevention of eclampsia, and this study is also included in the review of magnesium sulphate and other anticonvulsants for prevention of eclampsia (Duley 2010). It is also included here as it met the inclusion criteria for the review, and a secondary hypothesis in the trial was to compare the antihypertensive effects of these two drugs.

All but two studies were single comparisons comparing one type of antihypertensive drug with a different hypertensive drug. One study included three comparison groups (atenolol versus ketanserin versus methyldopa) (Argentina 1990). We undertook analysis for each single pair comparison, see Analyses 14, 15 and 16. One trial included four comparison groups (IV labetalol versus IV hydralazine versus oral nifedipine versus sublingual nifedipine) (Switzerland 2012). However, there were no outcome data that could be included in any analysis.

For further details seeCharacteristics of included studies table.

Excluded studies

Sixty‐five studies were excluded from the review. The reasons for exclusion are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. In summary, 15 studies were not a randomised trial, eight did not report clinical data, in 11 the women did not have very high blood pressure, in another 28 the intervention was not a comparison of two different antihypertensive drugs, two did not report outcome separately for women randomised before and after delivery, and in one more than 20% of women were excluded from the analysis.

Risk of bias in included studies

Most of the included trials were small. Only five studies recruited more than 100 women; Australia 2007 which recruited 124 women, Iran 2002 126 women, Nimodipine SG 2003 1750 women, South Africa 2000 150 and Panama 2006 200 women. As discussed above, a wide variety of agents were compared. Several trials were conducted in countries where English is not widely used, and it is possible that the search strategy may have missed other studies published in languages other than English.

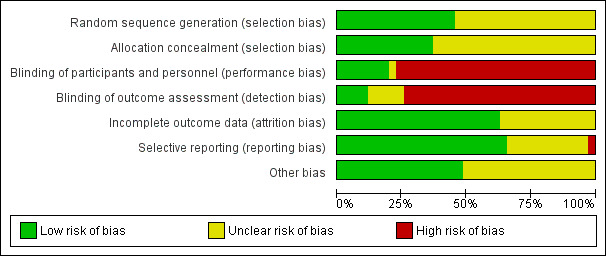

SeeFigure 1; Figure 2 for summaries of 'Risk of bias' assessments in included trials.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sixteen trials had adequate methods for random sequence generation and 13 trials had adequate concealment of allocation. Most of the others did not give adequate information about how or whether the allocation to treatment group was concealed.

Blinding

For most trials the identity of the allocated drug could only be blinded after trial entry with use of a double placebo. This was stated to have been done in only two studies (100 women) (Brazil 1994; Malaysia 2012). In another four, the comparison was stated to have been blinded (Brazil 1992; South Africa 1995; South Africa 1997b; Turkey 1996). It was clearly stated in some trials that they were either "open" or not blinded (Germany 1998; Netherlands 1999; Netherlands 2003; South Africa 2000; Iran 2011; Panama 2006; Germany 2006).

In three trials, blinding of some outcome assessment was performed (Brazil 1992; Iran 2002; Malaysia 2012). In one trial, it was reported that it was not blinded, but that the primary outcome of eclampsia is a binary, objective outcome and therefore not subject to observer or measurement bias (Nimodipine SG 2003).

In the remaining trials, there was no mention of blinding of participants, personnel or outcome assessors and because of the nature of the different treatment regimens, performance and detection bias cannot be ruled out.

Incomplete outcome data

Only short‐term outcomes were reported in these trials, but losses to follow‐up for reported outcomes was low in the majority of studies (Australia 1986; Australia 2007; Brazil 1992; England 1982; France 2010; Germany 1998; Germany 2006; Iran 2002; Iran 2011; Malaysia 2012; Nimodipine SG 2003; N Ireland 1991; Panama 2006; South Africa 1987; South Africa 1992; South Africa 1995; South Africa 1997; South Africa 1997a; South Africa 2000; Switzerland 2012; Tunisia 2002; USA 1987) or information was lacking and so it was not possible to assess attrition bias (Argentina 1990; Brazil 1994; Brazil 2011; India 2006; India 2011; Mexico 1989; Mexico 1993; Mexico 1998; Netherlands 1999; Netherlands 2003; South Africa 1989; South Africa 1997b; Turkey 1996). There is no information about outcome after discharge from hospital for either mother or baby.

Selective reporting

In the majority of trial reports assessed, all expected outcomes appeared to have been reported fully within the results (Argentina 1990; Australia 1986; Australia 2007; Brazil 1992; England 1982; Germany 2006; Iran 2002; Iran 2011; Malaysia 2012; Netherlands 1999; Nimodipine SG 2003; N Ireland 1991; Panama 2006; South Africa 1987; South Africa 1989; South Africa 1992; South Africa 1995; South Africa 1997; South Africa 1997a; South Africa 1997b; South Africa 2000; Tunisia 2002; USA 1987). In other trial reports it was difficult to assess selective reporting, mainly due to trial reports being reported in abstract form with limited information (Brazil 1994; Brazil 2011; France 2010; India 2006; India 2011; Mexico 1989; Mexico 1993; Mexico 1998; Netherlands 2003; Switzerland 2012; Turkey 1996). In one trial, the results for fetal heart rate monitoring and ultrasound assessment of fetal growth appear to have been reported incompletely (Germany 1998).

Other potential sources of bias

Most trials appeared to be free of other problems that could put them at risk of bias, e.g. baseline characteristics were balanced (Argentina 1990; Australia 1986; Australia 2007; Brazil 1992; Germany 1998; Iran 2002; Iran 2011; Malaysia 2012; Netherlands 1999; N Ireland 1991; Panama 2006; South Africa 1987; South Africa 1992; South Africa 1997; South Africa 1997a; Tunisia 2002; USA 1987). In other trial reports, it was difficult to assess other potential sources of bias, again mainly due to trial reports being reported in abstract form with limited information (Brazil 1994; Brazil 2011; England 1982; France 2010; Germany 2006; India 2006; India 2011; Mexico 1989; Mexico 1993; Mexico 1998; Netherlands 2003; Nimodipine SG 2003; South Africa 1989; South Africa 1995; South Africa 1997b; South Africa 2000; Switzerland 2012; Turkey 1996).

Effects of interventions

This review includes 35 trials, into which 3573 women were recruited.

(1) Labetalol versus hydralazine

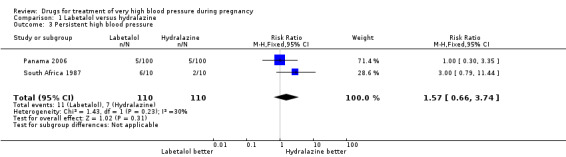

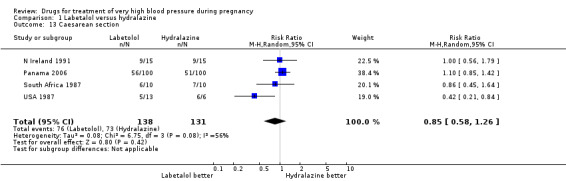

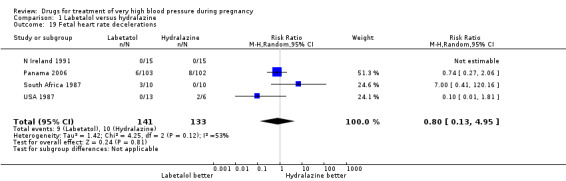

Four trials (269 women with outcome data) compared labetalol, with hydralazine. Two trials did not provide outcome data that could be included in an analysis (Brazil 2011; Switzerland 2012). Only two trials (220 women) reported data for persistent high blood pressure (risk ratio (RR) 1.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 3.74), Analysis 1.3. Data were reported for all four trials only for fetal or neonatal death (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.21), Analysis 1.4, caesarean section (average RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.26; Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.08; Chi² = 6.75, df = 3 (P = 0.08); I² = 56%), Analysis 1.13, and fetal heart rate decelerations (average RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.13 to 4.95: Heterogeneity: Tau² = 1.42; Chi² = 4.25, df = 2 (P = 0.12); I² = 53%), Analysis 1.19. There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of these two agents.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 3 Persistent high blood pressure.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 4 Fetal or neonatal deaths.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 13 Caesarean section.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 19 Fetal heart rate decelerations.

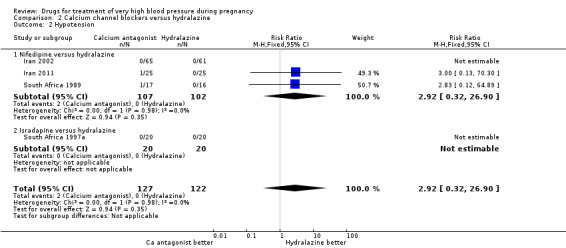

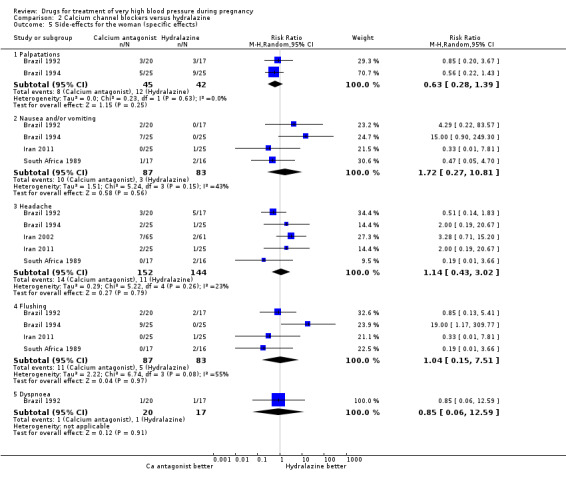

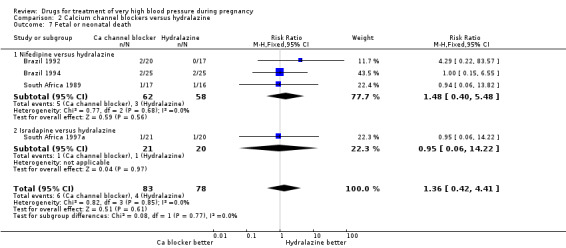

(2) Calcium channel blockers versus hydralazine

Eight trials (404 women) compared calcium channel blockers (nifedipine and isradipine) with hydralazine. One trial (41 women) did not provide outcome data that could be included in an analysis (Switzerland 2012). Persistent high blood pressure was reported by six trials (313 women). Fewer women allocated calcium channel blockers rather than hydralazine had persistent high blood pressure (8%% versus 22%; RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.66), Analysis 2.1. For all other outcomes reported, CIs were wide and crossed the line of no difference in effect.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Calcium channel blockers versus hydralazine, Outcome 1 Persistent high blood pressure.

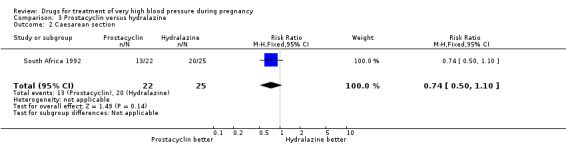

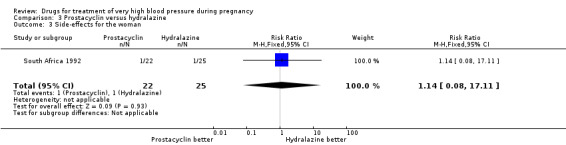

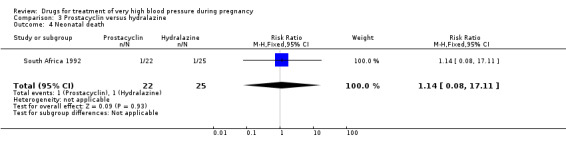

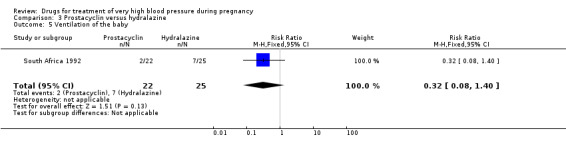

(3) Prostacyclin versus hydralazine

One trial (47 women) compared prostacyclin with hydralazine. For all outcomes reported, CIs were wide and crossed the line of no difference in effect.

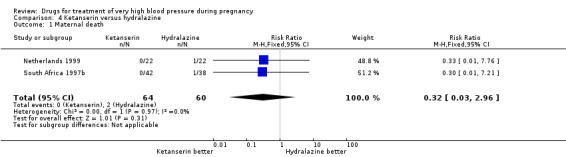

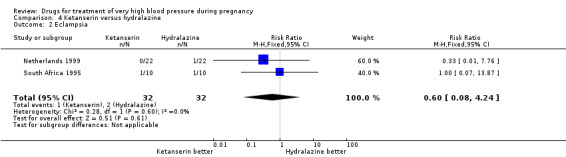

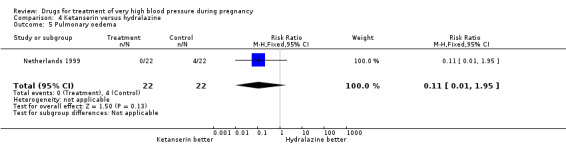

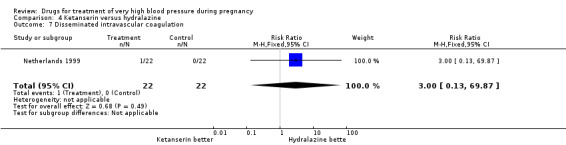

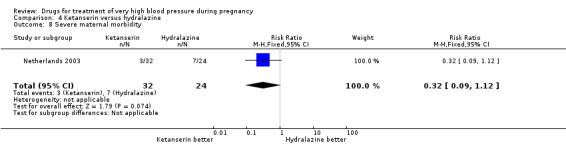

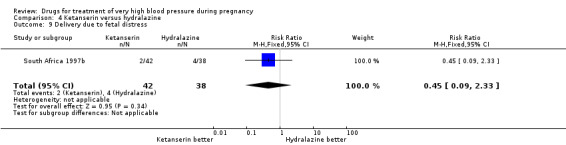

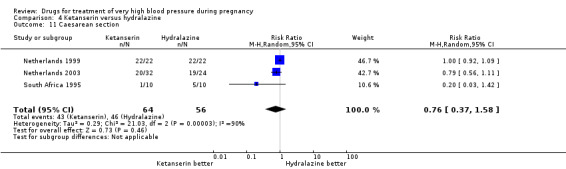

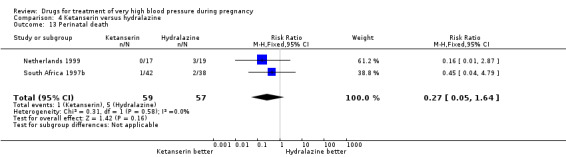

(4) Ketanserin versus hydralazine

Four trials (200 women) compared ketanserin with hydralazine. Ketanserin was associated with a substantially higher risk of persistent high blood pressure than hydralazine (27% versus 6%; three trials 180 women; RR 4.79, 95% CI 1.95 to 11.73), Analysis 4.3. However, side‐effects were less common with ketanserin than hydralazine (three trials 120 women; RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.53), Analysis 4.12. There was no clear evidence of a difference in the risk of hypotension (two trials 76 women; RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.03), Analysis 4.4. In the one small trial reporting HELLP syndrome, the risk of developing this complication of pre‐eclampsia was lower with ketanserin compared with hydralazine (44 women, RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.81), Analysis 4.6.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ketanserin versus hydralazine, Outcome 3 Persistent high blood pressure.

4.12. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ketanserin versus hydralazine, Outcome 12 Side‐effects for the women.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ketanserin versus hydralazine, Outcome 4 Hypotension.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ketanserin versus hydralazine, Outcome 6 HELLP syndrome.

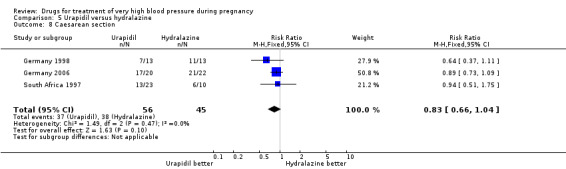

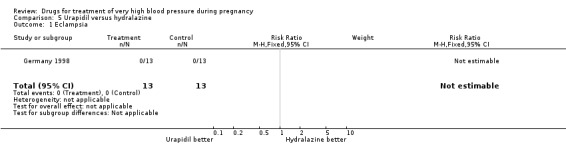

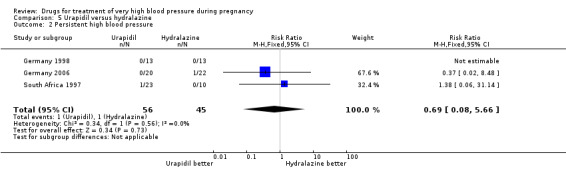

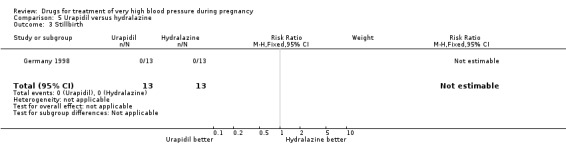

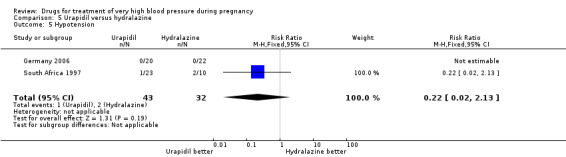

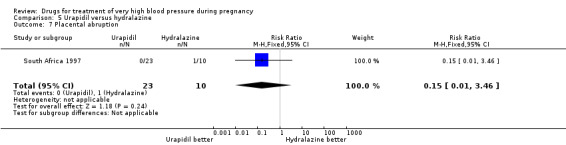

(5) Urapidil versus hydralazine

Three trials (101 women) compared urapidil with hydralazine. There were insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects on side‐effects for woman allocated these two drugs (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.19), Analysis 5.6. There was no clear evidence of a difference in the need for caesarean section between the groups (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.04), Analysis 5.8. There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of these two agents on any other outcome reported.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Urapidil versus hydralazine, Outcome 6 Side‐effects for the woman.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Urapidil versus hydralazine, Outcome 8 Caesarean section.

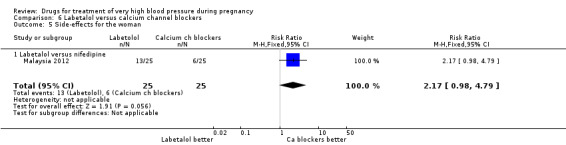

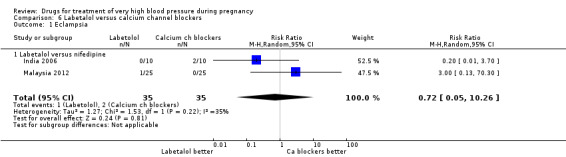

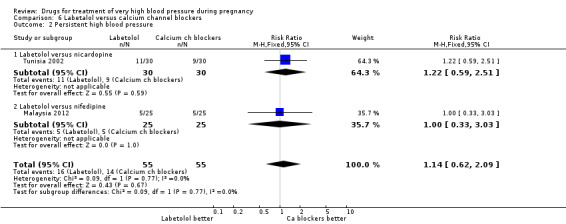

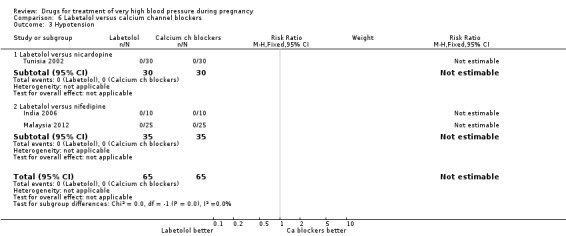

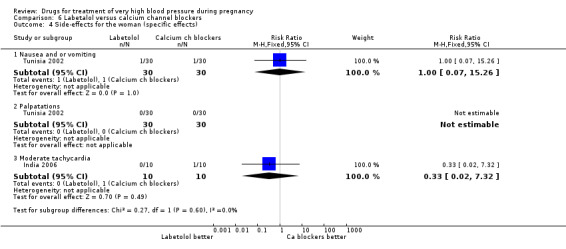

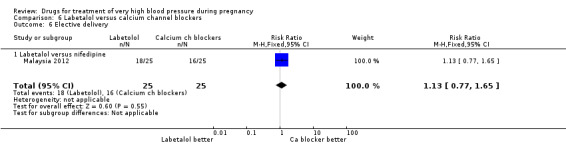

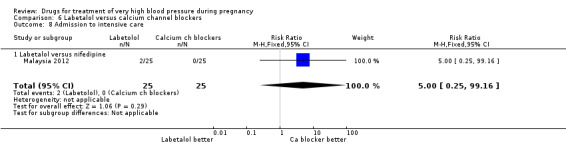

(6) Labetalol versus calcium channel blockers

Five trials (171 women) compared labetalol with calcium channel blockers (nicardipine and nifedipine). Two trials did not provide outcome data that could be included in an analysis (India 2011; Switzerland 2012). Data provided from one trial (50 women) suggested that nifedipine was associated with fewer side‐effects for women than labetalol (RR 2.17, 95% CI 0.98 to 4.79), Analysis 6.5, which was borderline for statistical significance. There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of these two agents for other outcomes.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Labetalol versus calcium channel blockers, Outcome 5 Side‐effects for the woman.

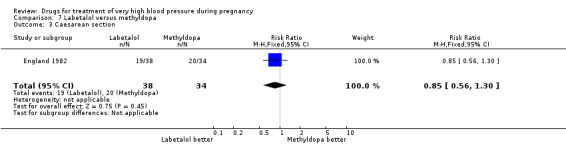

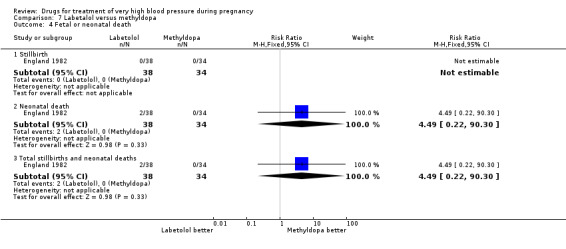

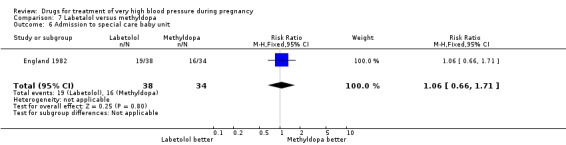

(7) Labetalol versus methyldopa

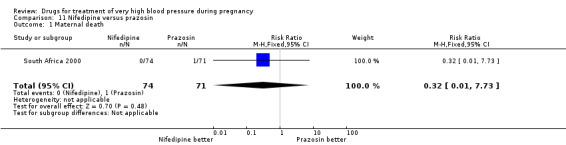

One trial (74 women) compared labetalol with methyl dopa. There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of these two agents.

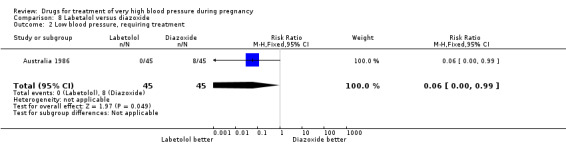

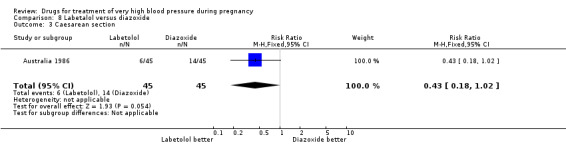

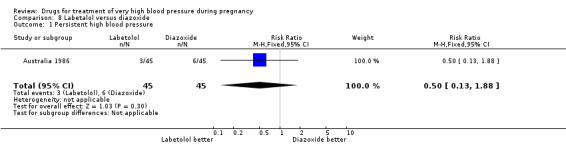

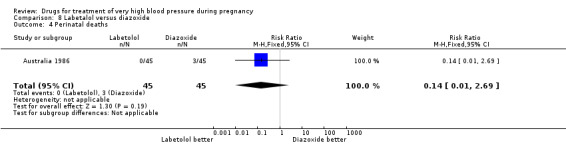

(8) Labetalol versus diazoxide

One trial (90 women) compared labetalol with diazoxide. Labetalol was associated with less hypotension than diazoxide, although the CIs are wide and borderline for statistical significance (RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.99), Analysis 8.2. This was reflected in a similar comparative increase in the need for caesarean section in the diazoxide group, which was again borderline for statistical significance (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.02), Analysis 8.3. Data were insufficient for any reliable conclusions about other outcomes reported.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Labetalol versus diazoxide, Outcome 2 Low blood pressure, requiring treatment.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Labetalol versus diazoxide, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

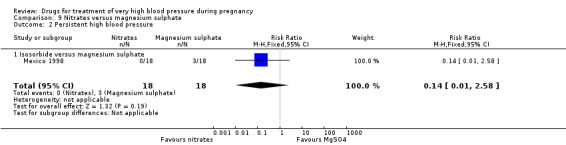

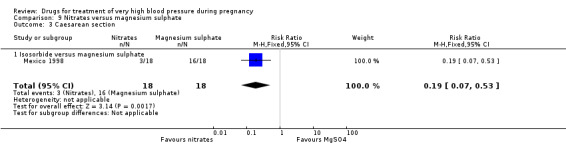

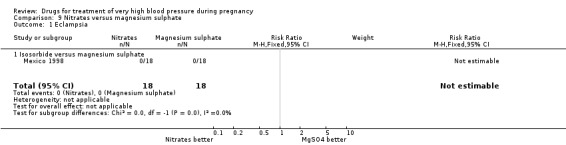

(9) Nitrates versus magnesium sulphate

One trial (36 women) compared isosorbide with magnesium sulphate. Although there was no clear difference in persistent hypertension (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.58), Analysis 9.2, isosorbide was associated with a lower risk of caesarean section than magnesium sulphate (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.53), Analysis 9.3.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Nitrates versus magnesium sulphate, Outcome 2 Persistent high blood pressure.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Nitrates versus magnesium sulphate, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

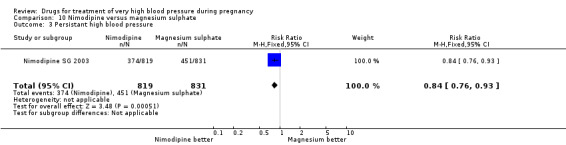

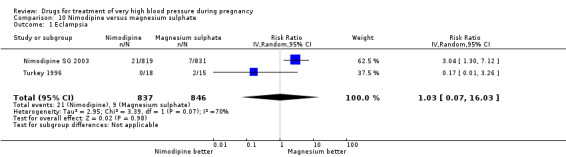

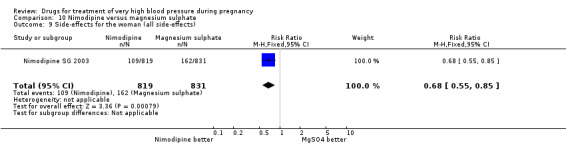

(10) Nimodipine versus magnesium sulphate

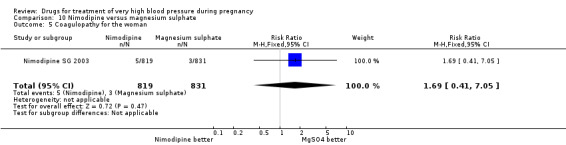

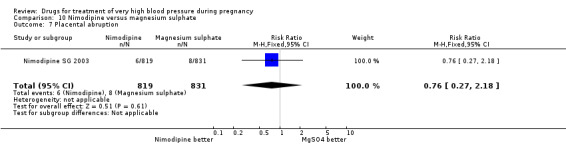

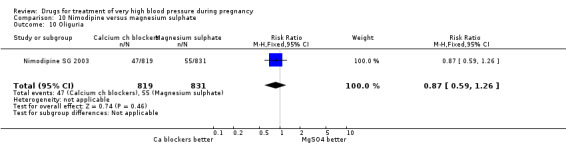

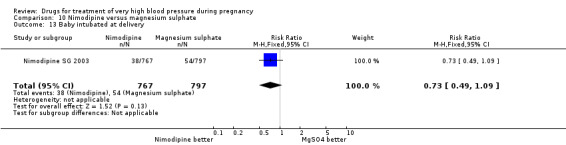

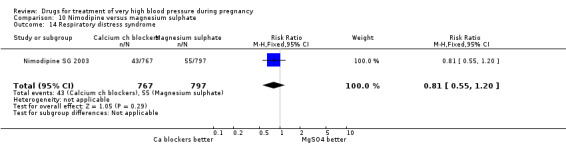

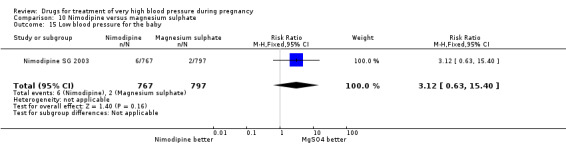

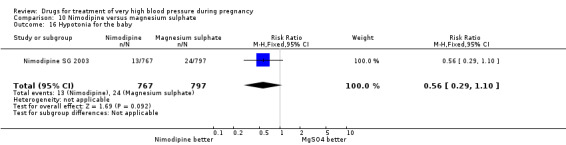

Two trials (1683 women) compared nimodipine with magnesium sulphate. Both drugs were associated with high levels of persistent high blood pressure (47% versus 65%), although the risk associated with nimodipine was lower than magnesium sulphate (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.93), Analysis 10.3. The risk of eclampsia was higher with nimodipine compared with magnesium sulphate in one large well conducted study (Nimodipine SG 2003), but the pooled result, including results from a smaller trial (Turkey 1996), showed no clear difference and substantial heterogeneity (average RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.07 to 16.03; Heterogeneity: Tau² = 2.95; Chi² = 3.39, df = 1 (P = 0.07); I² = 70%), Analysis 10.1. Nimodipine was associated with a lower risk of respiratory difficulties for the woman (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.99) although this was borderline for statistical significance, Analysis 10.6, fewer side‐effects (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.85), Analysis 10.9, and a lower risk of postpartum haemorrhage (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.92), Analysis 10.12. There were no clear differences in any other outcomes. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths were not reported.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Nimodipine versus magnesium sulphate, Outcome 3 Persistant high blood pressure.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Nimodipine versus magnesium sulphate, Outcome 1 Eclampsia.

10.6. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Nimodipine versus magnesium sulphate, Outcome 6 Respiratory difficulty for the woman.

10.9. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Nimodipine versus magnesium sulphate, Outcome 9 Side‐effects for the woman (all side‐effects).

10.12. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Nimodipine versus magnesium sulphate, Outcome 12 Postpartum haemorrhage.

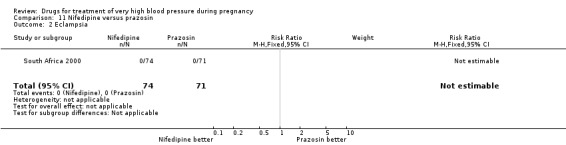

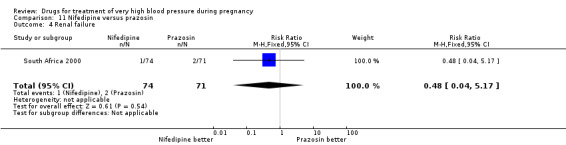

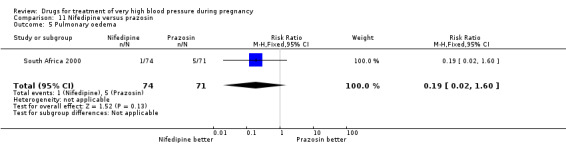

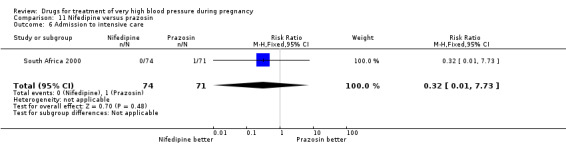

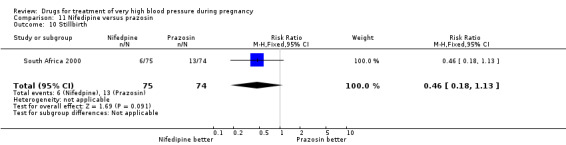

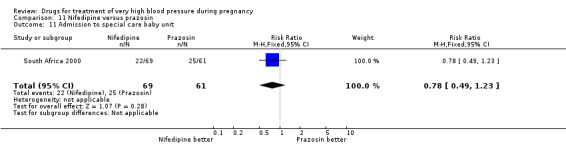

(11) Nifedipine versus prazosin

One trial (130 women) compared nifedipine with prazosin. There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of these two agents.

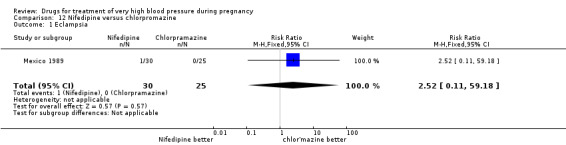

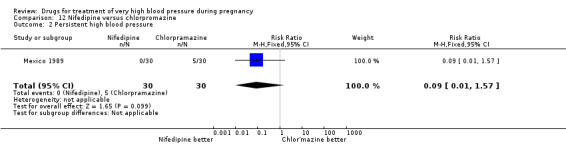

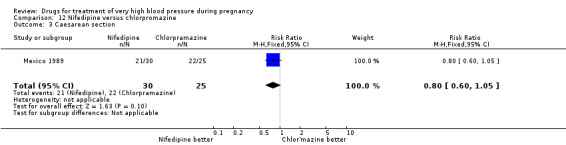

(12) Nifedipine versus chlorpromazine

One small trial (60 women) compared nifedipine with chlorpromazine. There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of these two agents.

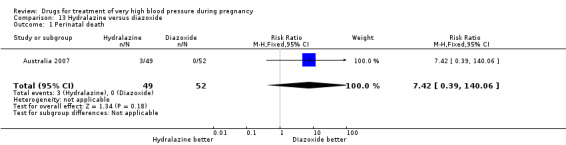

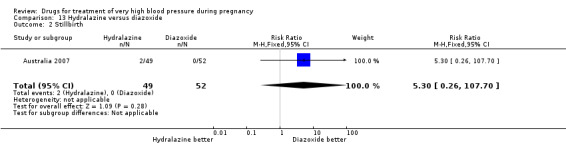

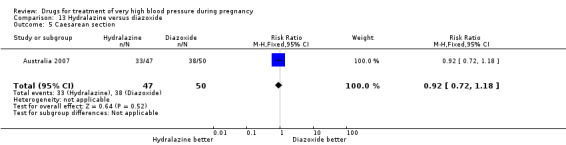

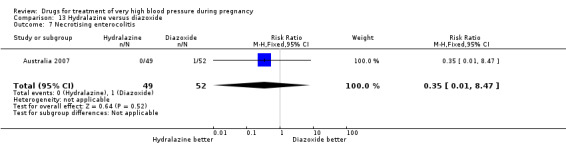

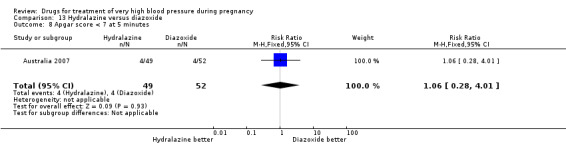

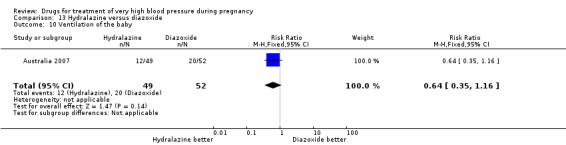

(13) Hydralazine versus diazoxide

One trial (97 women) compared hydralazine with diazoxide. There are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the comparative effects of these two agents.

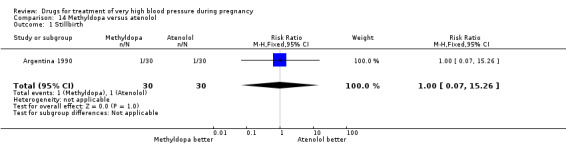

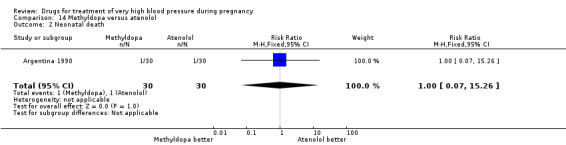

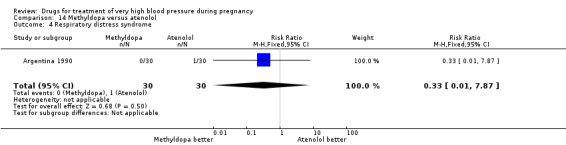

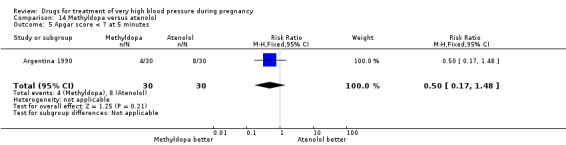

(14) Methyldopa versus atenolol

One three‐arm trial (90 women) compared ketanserin versus alpha methyldopa versus atenolol. We undertook analysis for the pair‐wise comparison methyldopa versus atenolol. For the comparison of methyldopa with atenolol, atenolol was associated with fewer side‐effects for women (somnolence), although the CI was very wide (RR 21.00, 95% CI 1.29 to 342.93), Analysis 14.3. There were no clear differences in any other outcomes.

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Methyldopa versus atenolol, Outcome 3 Side‐effects for the woman (specific effects).

(15) Urapidil versus calcium channel blockers

One trial (18 women) compared urapidil versus calcium channel blockers (nicardipine). There was no difference between the two agents for side‐effects for the baby or women. No other outcomes were reported.

Side‐effects

Few trials provided data on the specific side‐effects related to the different agents. Reported side‐effects included:

for hydralazine: headache, flushing, light head, nausea and palpitations;

for labetalol: flushing, light head, palpitations and scalp tingling;

for nifedipine: flushing, nausea, vomiting;

for urapidil: nausea and tinnitus;

for magnesium sulphate: flushing;

for methyldopa: somnolence.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Most of the drugs included in this review reduce high blood pressure. This is not surprising, as there is no reason why drugs that are known to reduce blood pressure in people who are not pregnant should not also reduce blood pressure for women who are pregnant. Currently, for women with very high blood pressure during pregnancy there is insufficient evidence to conclude that any one antihypertensive drug is clearly better than another.

Probably the three most commonly recommended drugs for very high blood pressure during pregnancy are hydralazine, labetalol and the calcium channel blocker nifedipine. Data in this review do not suggest any significant differential effects, with the exception of for calcium channel blockers, which were associated with less persistent hypertension than hydralazine and possibly less side‐effects compared to labetalol.

Hydralazine was associated with a significant increase in the risk of HELLP syndrome when compared with ketanserin (46% versus 9%) however, such a high level of HELLP syndrome is difficult to explain with hydralazine use, and is in contrast to the low risk of HELLP syndrome in another study comparing hydralazine with labetalol where incidence of HELLP is 2% in both arms. There was insufficient evidence for any difference among these three drugs for other more substantive outcomes for the mother or baby.

From the data presented here it is clear that nimodipine, ketanserin, and high‐dose diazoxide have serious disadvantages, and so should not be used for women with very high blood pressure during pregnancy as better options are readily available. Nimodipine is generally no longer used to control high blood pressure in the non‐pregnant population, but instead, is used for improvement of neurological outcome after subarachnoid haemorrhage (Tomassoni 2008). Diazoxide given as repeated 75 mg bolus injections, seems to be associated with a greater risk of dropping the blood pressure so low that treatment is required to bring it back up again, with an associated increased risk of caesarean section, when compared with labetalol. Smaller doses may not have this disadvantage, as observed in a recent study in which 15 mg bolus injections were compared, with no ill effect on hypotension (Hennessy 2007). Ketanserin was far more likely to be associated with persistent hypertension than hydralazine.

In the one large trial that compared nimodipine with magnesium sulphate, 54% of women allocated magnesium sulphate had persistent hypertension. So, although it is clearly of value for seizure prophylaxis in women with pre‐eclampsia (Duley 2010), magnesium sulphate should not be used for control of very high blood pressure. Nearly half the women in the nimodipine arm also had persistently high blood pressure, as well as increased risk of eclampsia compared with magnesium sulphate

It would also seem sensible to avoid chlorpromazine. Although only one small trial has compared chlorpromazine with nifedipine, this antipsychotic drug has a complex mode of action and impacts on several organ systems. One well known side‐effect is convulsions, which is a serious disadvantage for women with hypertension during pregnancy. That this concern is real, rather than theoretical, is demonstrated by the review of magnesium sulphate versus lytic cocktail (which includes chlorpromazine) for women with eclampsia (Duley 2010a). This review shows a clear increase in the risk of further seizures associated with lytic cocktail compared to magnesium sulphate.

One trial did compare an antihypertensive, the nitrate isosorbide, with placebo for women with very high blood pressure (Mexico 2000). This study was excluded from the review, as our objective was to compare one antihypertensive drug with another. In this study, 60 women with diastolic blood pressure 110 mmHg or above after 20 minutes rest were randomised to either sublingual isosorbide or placebo. Both groups had an intravenous infusion of Hartmann solution. Outcome was assessed over one hour, during which time one woman allocated isosorbide had hypotension. At the end of the one‐hour study, mean blood pressure was substantially lower for women allocated isosorbide compared to placebo, there were no episodes of fetal distress or imminent eclampsia, and similar numbers of women in both groups complained of headache. Outcome after one hour is not reported. This study does show that isosorbide lowers blood pressure, but the clinically important question is not whether it is better than placebo, but whether it has any substantive advantages over other drugs in widespread clinical use.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Any effect on a comparative improvement in control of blood pressure would be of far greater clinical importance if it was reflected in comparative improvements in other more substantive outcomes, such as stroke, serious maternal morbidity and perinatal death. With the exception of the large trial comparing nimodipine with magnesium sulphate, all the trials to date have been small, with few outcomes other than control of blood pressure reported.

During pregnancy, there are additional issues other than control of blood pressure, however, such as avoiding a precipitous drop in blood pressure that might cause problems for the unborn baby, side‐effects that are similar to symptoms of worsening pre‐eclampsia and so may delay recognition of the need to intervene, not lowering the blood pressure too far as this might also compromise blood supply across the placenta to the baby, and if the drug itself crosses the placenta not causing harm to the baby. There are relatively few data on the comparative effects of the alternative drugs on these other outcomes.

Surprisingly few studies have reported maternal side‐effects. Common side‐effects included severe headache and nausea, symptoms which are similar to those of imminent eclampsia and so may make clinical management more difficult. There has been concern that rapid‐release nifedipine capsules may increase the risk of hypotension, and in some countries these have been withdrawn from use. One small trial (64 women) compared nifedipine capsules with slower and longer‐acting nifedipine tablets (Australia 2002). Outcome was assessed after 90 minutes; similar proportions of women had persistent high blood pressure (11% allocated capsules versus 9% allocated tablets), and there was less hypotension amongst those allocated tablets although this did not achieve statistical significance (3/31 versus 1/33; risk ratio 3.19, 95% confidence interval 0.35 to 29.10).

There were insufficient data for the planned subgroup analysis by whether the severe hypertension was associated with proteinuria.

Quality of the evidence

The overall methodological quality of the trials contributing data to the review was low to moderate and has been summarised in Figure 1 and Figure 2. While none of the studies were assessed as being at high risk of bias for all domains, several trials did not provide clear information on methods. Fifteen of the 35 included trials failed to describe adequately the methods used for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were assessed as unclear risk of bias. Lack of blinding was a problem in all of the included studies; blinding women and clinical staff to a randomised group is not feasible with this type of intervention. The impact of lack of blinding is difficult to judge. Knowledge of allocation could have affected other aspects of care and the assessment of many outcomes, particularly blood pressure. Loss to follow‐up was not always described, but did not appear to be a major source of bias in the majority of studies.

Potential biases in the review process

Problems with interpreting the data in this review include differences in the way persistent hypertension was defined for each study, and differences in the clinical characteristics of the women. For example, definitions for persistent hypertension included time taken to achieve target blood pressure, ability to achieve target blood pressure within a certain time period, and need for additional medication. These differences are reflected in the wide range of frequency of persistent high blood pressure across studies. For example, in the five categories with hydralazine as a comparator the frequency of persistent high blood pressure amongst women allocated hydralazine ranged from 0% to 20%, while amongst women allocated an alternative drug, it ranged from 0% to 60%. As few studies had blinding either of the intervention or the assessment of outcomes, there is considerable potential for bias in the assessment of blood pressure.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

An alternative analysis of this topic concluded that the data do not support hydralazine as first line treatment for very high blood pressure in pregnancy (Magee 2003), and recommended future trials compare labetalol with nifedipine. However, that analysis included quasi‐randomised studies and women with very high blood pressure after delivery. Once the analysis is restricted to include only studies with less potential for bias and women with very high blood pressure during pregnancy or labour, as in our review, the data are insufficient to support the conclusion that labetalol is better than hydralazine.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no clear evidence that one antihypertensive is preferable to the others for improving outcome for women with very high blood pressure during pregnancy, and their babies. Until better evidence is available, the best choice of drug for an individual woman probably depends on the experience and familiarity of her clinician with a particular drug, and on what is known about adverse maternal and fetal side‐effects. Probably best avoided are magnesium sulphate (although this is indicated for women who require an anticonvulsant for prevention or treatment of eclampsia), high‐dose diazoxide, ketanserin, nimodipine and chlorpromazine.

Implications for research.

Well designed large trials are needed to make reliable comparisons of the maternal, fetal and neonatal effects of antihypertensives in common clinical practice. Ideally, clinicians should compare an agent they are familiar with in their routine clinical practice with a promising alternative that is available locally, or would be likely to become available if shown to be preferable. Many hospitals around the world continue to use hydralazine, labetalol, or nifedipine as the first choice for women with very high blood pressure. The priority is therefore to compare these drugs with each other, or other more promising alternatives.

Future trials should measure outcomes that are important to women and their babies, rather than attempting to document relatively subtle differences in the effects on blood pressure. These outcomes should include persistent high blood pressure, need for additional antihypertensive drugs, further episodes of severe hypertension, low blood pressure, side‐effects, severe maternal morbidity (such as stroke, eclampsia, renal failure, and coagulopathy), need for magnesium sulphate, mode of delivery, length of stay in hospital, mortality for the baby, and admission and length of stay in a special/intensive care nursery. In order to reliably estimate differential effects on these substantive outcomes, high quality large studies will be required. There should also be long‐term follow‐up to assess possible effects on the woman's risk of cardiovascular problems after discharge from hospital, and on growth and development of the child. This is relevant not only because these drugs may cross the placenta, but also because too rapid lowering of blood pressure with a placenta that has marginal functional reserve could lead to ischaemic brain injury and long‐term neurodevelopment problems. Alongside data from randomised trials, mechanisms need to be developed to monitor possible rare adverse events related to in utero exposure to antihypertensive agents.

Interpretation of the results of future studies would be made easier and more clinically meaningful by the use of similar definitions for key outcomes, such as persistent high blood pressure, and hypotension. Studies that recruit women both before and after delivery should report outcome data separately for these two groups of women. Outcomes should also be reported separately for women with and without proteinuria at trial entry.

Once better information is available about the relative merits and hazards of agents already in widespread use, it will become possible to compare new drugs with the best of the traditional agents in well designed randomised trials.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 February 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Eleven new trials were included in this update. The review now includes a total of 35 trials into which 3573 women were recruited. |

| 9 January 2013 | New search has been performed | Search updated and 39 trial reports identified. Methods updated based on the PCG guidelines and the generic protocol. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1999 Review first published: Issue 2, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 February 2012 | Amended | Search updated. Thirty‐seven trial reports added to Studies awaiting classification. |

| 2 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 31 March 2006 | New search has been performed | Search updated in February 2006. New included studies: Brazil 1992; Mexico 1998; Netherlands 2003; Tunisia 2002; South Africa 1997a. New excluded studies: Australia 2002; Bangladesh 2002; Brazil 1984; Brazil 1988; Brazil 1988a; China 2000; Egypt 1989; Egypt 1992; India 1963; India 2001; Italy 2004; Jamaica 1999; Japan 1999; Japan 2000; Japan 2003; Mexico 1967; Mexico 2004; Netherlands 2002; New Zealand 1986; Philipines 2000; South Africa 1984; Venezuela 2001. Study ID changed: South Africa 1994 changed to South Africa 1997b. New ongoing study: Warren 2004a, comparing labetolol with magnesium sulphate. Methods text expanded in line with the guidelines for the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. All text revised and expanded to reflect inclusion, and exclusion, of new studies. |

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Antoinette Bolte for her generosity in supplying unpublished data from Netherlands 2003. Thanks also to Rory Collins who contributed to earlier versions of this review published within the Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials, later the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database.

Many thanks to Therese Dowswell for her contribution in assessing studies and extracting data for the 2013 update.

The authors would like to acknowledge the enthusiastic contribution of David Henderson‐Smart to previous versions of this review. David Henderson‐Smart died in February 2013, and we would like to dedicate the review to him.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

In an earlier version of the review, we also searched MEDLINE (1966 to April 2002) using the MeSH terms 'pregnancy' and 'hypertension', limited to randomised controlled trials and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 2) using the following strategy:

HYPERTENSION, PREGNANCY‐INDUCED:ME

PREECLAMP*

PRE‐ECLAMP*

(PRE next ECLAMP*)

ECLAMP*

(HYPERTENS* and PREGNAN*)

(((((#1 or #2) or #3) or #4) or #5) or #6)

((NIFEDIPINE or NIMODIPINE) or ISRADIPINE)

(HYDRALAZINE or DIHYDRALAZINE)

((LABETALOL or ATENOLOL) or PROPRANOLOL)

(GTN or (GLYCEROL and TRINITR*))

(URAPIDIL or PRAZOSIN)

((((#8 or #9) or #10) or #11) or #12)

(#7 and #13)

Appendix 2. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

The following methods were used to assess Australia 1986; Brazil 1992; Brazil 1994; England 1982; Germany 1998; Iran 2002; Mexico 1989; Mexico 1993; Mexico 1998; Netherlands 1999; Netherlands 2003; Nimodipine SG 2003; N Ireland 1991; South Africa 1987; South Africa 1989; South Africa 1992; South Africa 1995; South Africa 1997; South Africa 1997a; South Africa 1997b; South Africa 2000; Tunisia 2002; Turkey 1996; USA 1987; Argentina 1986; Australia 2002; Bangladesh 2002; Brazil 1984; Brazil 1988; Brazil 1988a; China 2000; Egypt 1988; Egypt 1989; Egypt 1992; France 1986; Ghana 1995; India 1963; India 2001; Iran 1994; Israel 1991; Israel 1999; Italy 2004; Jamaica 1999; Japan 1999; Japan 2000; Japan 2002; Japan 2003; Malaysia 1996; Mexico 1967; Mexico 2000; Mexico 2004; Netherlands 2002; New Zealand 1986; New Zealand 1992; Philipines 2000; Scotland 1983; Singapore 1971; South Africa 1982; South Africa 1984; South Africa 1993; South Africa 2002; Spain 1988; Sweden 1993; USA 1999; Venezuela 2001.

Selection of studies

Two authors independently evaluated studies to assess eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. If there was no agreement, the third author was asked to independently assess the study for inclusion. If agreement was still not reached, the study was excluded until clarification could be obtained from the authors.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

Two authors independently extracted data on trial characteristics. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Quality of each included study was assessed using the criteria in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2002).

(i) Selection bias (randomisation and allocation concealment)

Method for generating the randomisation sequence was described for each trial. Studies with a quasi‐random design were excluded. Concealment of allocation was assessed for each trial, with adequate concealment graded A, unclear B and clearly inadequate concealment C. Studies with clearly inadequate concealment of allocation were excluded. Where the method of allocation concealment was unclear, authors were contacted to provide further details.

(ii) Performance bias (blinding of participants, researchers and outcome assessment)

Quality scores for blinding of the assessment of outcome were assigned to each reported outcome using the following criteria (these scores are displayed in the methods column of the 'Characteristics of included studies' table):

(A) double blind, neither investigator nor participant knew or were likely to guess the allocated treatment; (B) single blind, either the investigator or the participant knew the allocation. Or the trial may be described as double blind, but side‐effects of one or other treatment mean that it is likely that for a significant proportion (more that 20 per cent) of participants the allocation could be correctly identified, or the method for blinding is not described; (C) no blinding, both investigator and participant knew (or were likely to guess) the allocated treatment, or blinding not mentioned.

(iii) Attrition bias (loss of participants, eg withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

For completeness of follow‐up, scores were assigned using the following criteria:

(A) less than three per cent of participants excluded from the analysis; (B) three per cent to 9.9 per cent of participants excluded from the analysis; (C) 10 per cent to 19.9 per cent of participants excluded from the analysis.

Excluded: If not possible to enter data based on intention to treat or 20% or more participants were excluded from the analysis of that outcome.

Data extraction and data entry

Two review authors extracted data on outcomes, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. If agreement was not reached, that item was excluded until further clarification was available from the authors. Data were entered onto the Review Manager software (RevMan 2000) and checked for accuracy. There was no blinding of authorship or results.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using Review Manager (RevMan 2000). Results were presented as summary relative risk with 95% confidence intervals and, if relevant, as risk difference and number needed to treat to benefit. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between trials. In the absence of significant heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model. If substantial heterogeneity was detected (I2 more than 50%), possible causes were explored and subgroup analyses for the main outcomes performed. Heterogeneity that was not explained by subgroup analyses was modelled using random‐effects analysis, where appropriate. Possible explanations for the variation, such as study quality and women's characteristics at trial entry, were explored.

Sensitivity analyses

When appropriate, in future updates, we will carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality based on concealment of allocation, by excluding studies with unclear allocation concealment (rated B).

Subgroup analyses

Data are presented by class of drug. In addition, the following subgroup analyses will be conducted when sufficient data become available:

treatment regimen within each class of drug;

whether severe hypertension alone, or severe hypertension plus proteinuria at trial entry.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Labetalol versus hydralazine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal deaths | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Eclampsia | 2 | 220 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Persistent high blood pressure | 2 | 220 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [0.66, 3.74] |

| 4 Fetal or neonatal deaths | 4 | 274 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.17, 3.21] |

| 5 HELLP syndrome | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.14, 6.96] |

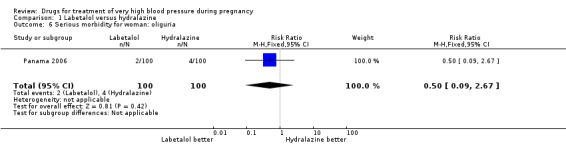

| 6 Serious morbidity for woman: oliguria | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.09, 2.67] |

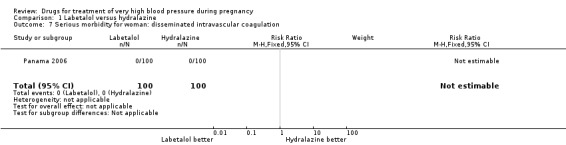

| 7 Serious morbidity for woman: disseminated intravascular coagulation | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Serious morbidity for woman: acute renal insufficiency | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Serious morbidity for woman: pulmonary oedema | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.12, 72.77] |

| 10 Hypotension | 3 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.01, 4.11] |

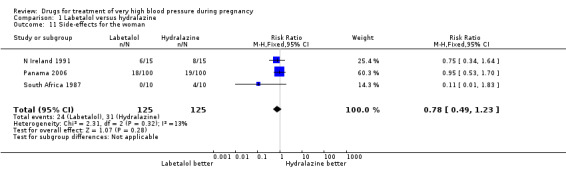

| 11 Side‐effects for the woman | 3 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.49, 1.23] |

| 12 Placental abruption | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.05, 5.43] |

| 13 Caesarean section | 4 | 269 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.58, 1.26] |

| 14 Respiratory distress syndrome | 2 | 224 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.67, 1.71] |

| 15 Necrotizinc enterocolitis | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.98 [0.18, 21.50] |

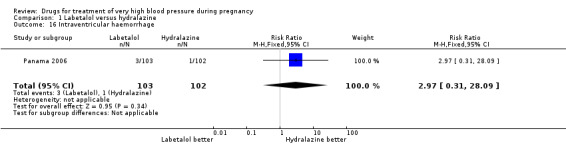

| 16 Intraventricular haemorrhage | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.97 [0.31, 28.09] |

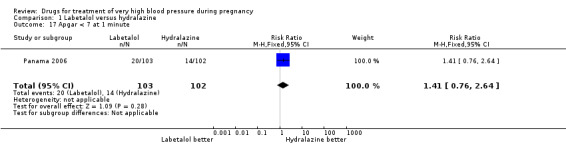

| 17 Apgar < 7 at 1 minute | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.76, 2.64] |

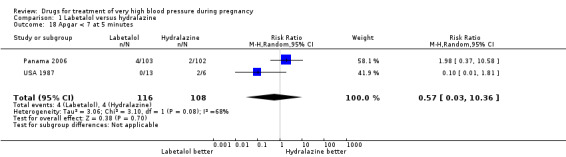

| 18 Apgar < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 224 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.03, 10.36] |

| 19 Fetal heart rate decelerations | 4 | 274 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.13, 4.95] |

| 20 Neonatal hypoglycaemia | 2 | 39 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.19, 6.94] |

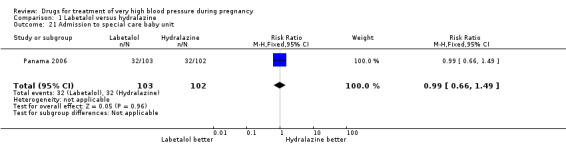

| 21 Admission to special care baby unit | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.66, 1.49] |

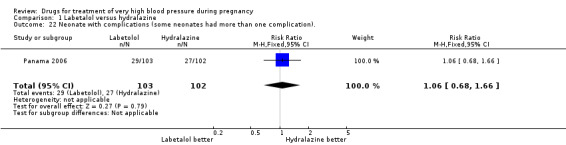

| 22 Neonate with complications (some neonates had more than one complication). | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.68, 1.66] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 1 Maternal deaths.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 2 Eclampsia.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 5 HELLP syndrome.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 6 Serious morbidity for woman: oliguria.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 7 Serious morbidity for woman: disseminated intravascular coagulation.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 8 Serious morbidity for woman: acute renal insufficiency.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 9 Serious morbidity for woman: pulmonary oedema.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 10 Hypotension.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 11 Side‐effects for the woman.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 12 Placental abruption.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 14 Respiratory distress syndrome.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 15 Necrotizinc enterocolitis.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 16 Intraventricular haemorrhage.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 17 Apgar < 7 at 1 minute.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 18 Apgar < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 20 Neonatal hypoglycaemia.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 21 Admission to special care baby unit.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Labetalol versus hydralazine, Outcome 22 Neonate with complications (some neonates had more than one complication)..

Comparison 2. Calcium channel blockers versus hydralazine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Persistent high blood pressure | 6 | 313 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.21, 0.66] |

| 1.1 Nifedipine versus hydralazine | 5 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.21, 0.70] |

| 1.2 Isradipine versus hydralazine | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.05] |

| 2 Hypotension | 4 | 249 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.92 [0.32, 26.90] |

| 2.1 Nifedipine versus hydralazine | 3 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.92 [0.32, 26.90] |

| 2.2 Isradapine versus hydralazine | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Further episode/s of very high blood pressure | 2 | 163 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.65, 1.11] |

| 3.1 Nifedipine versus hydralazine | 2 | 163 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.65, 1.11] |

| 3.2 Isradipine versus hydralazine | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Side‐effects for the woman | 5 | 286 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.52, 1.25] |

| 4.1 Nifedipine versus hydralazine | 4 | 246 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.52, 1.25] |

| 4.2 Isradipine versus hydralazine | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Side‐effects for the woman (specific effects) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Palpatations | 2 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.28, 1.39] |

| 5.2 Nausea and/or vomiting | 4 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.72 [0.27, 10.81] |

| 5.3 Headache | 5 | 296 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.43, 3.02] |

| 5.4 Flushing | 4 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.15, 7.51] |

| 5.5 Dyspnoea | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.06, 12.59] |

| 6 Caesarean section | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.56, 1.29] |

| 6.1 Nifedipine versus hydralazine | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.56, 1.29] |

| 7 Fetal or neonatal death | 4 | 161 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.42, 4.41] |

| 7.1 Nifedipine versus hydralazine | 3 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [0.40, 5.48] |

| 7.2 Isradapine versus hydralazine | 1 | 41 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.06, 14.22] |

| 8 Apgar < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Fetal heart rate decelerations | 4 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.11, 1.31] |

| 9.1 Nifedipine versus hydralazine | 3 | 213 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.04, 2.99] |

| 9.2 Isradipine versus hydralazine | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.09, 1.83] |

2.2. Analysis.