Abstract

Background

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a common cause of physical, psychological and social problems in women of reproductive age. The key characteristic of PMS is the timing of symptoms, which occur only during the two weeks leading up to menstruation (the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are increasingly used as first line therapy for PMS. SSRIs can be taken either in the luteal phase or else continuously (every day). SSRIs are generally considered to be effective for reducing premenstrual symptoms but they can cause adverse effects.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of SSRIs for treating premenstrual syndrome.

Search methods

Electronic searches for relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were undertaken in the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL (February 2013). Where insufficient data were presented in a report, attempts were made to contact the original authors for further details.

Selection criteria

Studies were considered in which women with a prospective diagnosis of PMS, PMDD or late luteal phase dysphoric disorder (LPDD) were randomised to receive SSRIs or placebo for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected the studies, assessed eligible studies for risk of bias, and extracted data on premenstrual symptoms and adverse effects. Studies were pooled using random‐effects models. Standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for premenstrual symptom scores, using separate analyses for different types of continuous data (that is end scores and change scores). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. Analyses were stratified by type of drug administration (luteal or continuous) and by drug dose (low, medium, or high). We calculated the number of women who would need to be taking a moderate dose of SSRI in order to cause one additional adverse event (number needed to harm: NNH). The overall quality of the evidence for the main findings was assessed using the GRADE working group methods.

Main results

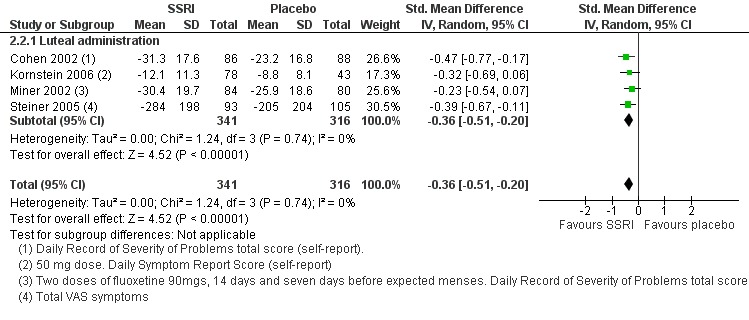

Thirty‐one RCTs were included in the review. They compared fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram and citalopram versus placebo. SSRIs reduced overall self‐rated symptoms significantly more effectively than placebo. The effect size was moderate when studies reporting end scores were pooled (for moderate dose SSRIs: SMD ‐0.65, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.84, nine studies, 1276 women; moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 58%), low quality evidence). The effect size was small when studies reporting change scores were pooled (for moderate dose SSRIs: SMD ‐0.36, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.51, four studies, 657 women; low heterogeneity (I2=29%), moderate quality evidence).

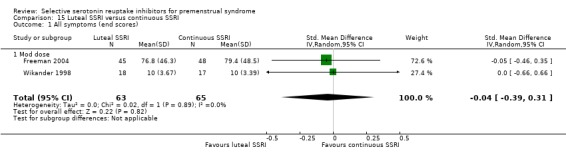

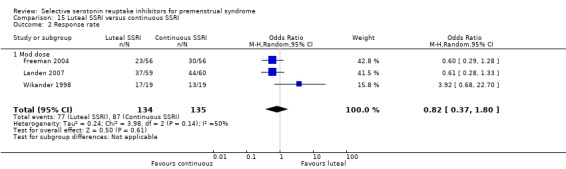

SSRIs were effective for symptom relief whether taken only in the luteal phase or continuously, with no clear evidence of a difference in effectiveness between these modes of administration. However, few studies directly compared luteal and continuous regimens and more evidence is needed on this question.

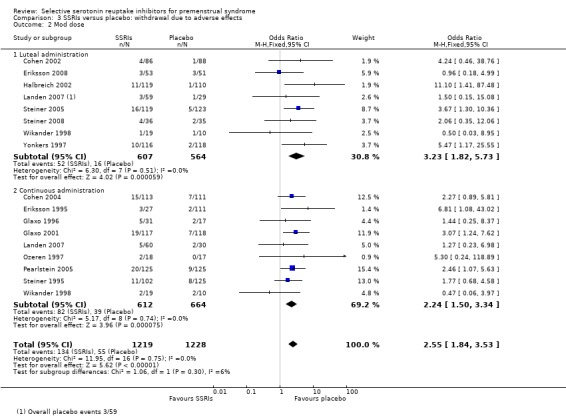

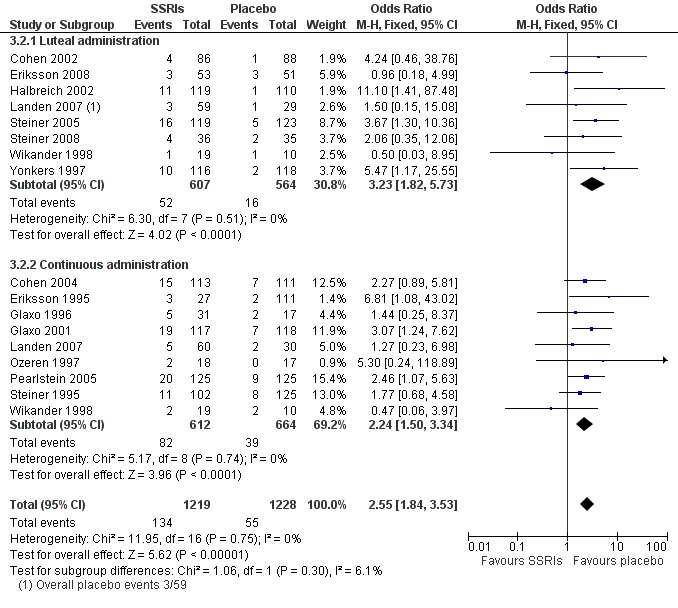

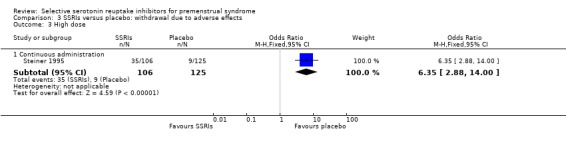

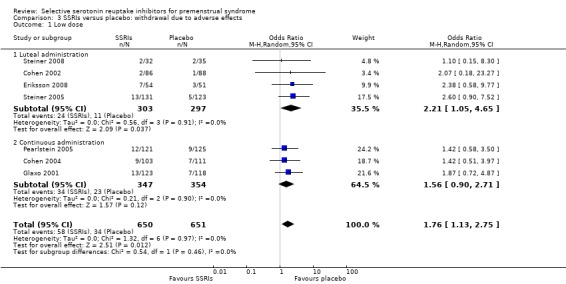

Withdrawals due to adverse effects were significantly more likely to occur in the SSRI group (moderate dose: OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.84 to 3.53, 15 studies, 2447 women; no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), moderate quality evidence). The most common side effects associated with a moderate dose of SSRIs were nausea (NNH = 7), asthenia or decreased energy (NNH = 9), somnolence (NNH = 13), fatigue (NNH = 14), decreased libido (NNH = 14) and sweating (NNH = 14). In secondary analyses, SSRIs were effective for treating specific types of symptoms (that is psychological, physical and functional symptoms, and irritability). Adverse effects were dose‐related.

The overall quality of the evidence was low to moderate, the main weakness in the included studies being poor reporting of methods. Heterogeneity was low or absent for most outcomes, though (as noted above) there was moderate heterogeneity for one of the primary analyses.

Authors' conclusions

SSRIs are effective in reducing the symptoms of PMS, whether taken in the luteal phase only or continuously. Adverse effects are relatively frequent, the most common being nausea and asthenia. Adverse effects are dose‐dependent.

Plain language summary

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for premenstrual syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a common cause of physical, psychological and social problems in women of reproductive age. PMS is distinguished from 'normal' premenstrual symptoms by the degree of distress and disruption it causes. Symptoms occur during the period leading up to the menstrual period and are relieved by the onset of menstruation. Common symptoms include irritability, depression, anxiety and lethargy. A clinical diagnosis of PMS requires that the symptoms are confirmed by prospective recording (that is recorded as they occur) for at least two menstrual cycles and that they cause substantial distress or impairment to daily life. It is estimated that approximately one in five women of reproductive age are affected. PMS can severely disrupt a woman's daily life and some women seek medical treatment. Researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration reviewed the evidence about the effectiveness and safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for treating PMS. They examined the research up to February 2013.

The review included 31 randomised controlled trials which compared SSRIs with placebo in a total of 4372 women who were clinically diagnosed with PMS. SSRIs were found to be effective for reducing the overall symptoms of PMS and also for reducing specific types of symptoms (psychological, physical and functional symptoms, and irritability). SSRIs were usually taken for about two weeks before the start of the menstrual period (the luteal phase) or every day (continuously). Both regimens appeared to be equally effective, although more research is needed to confirm this.

Adverse effects were more common in the women taking SSRIs than in those taking placebo. The most commonly occurring side effects were nausea and decreased energy. The review authors calculated that nausea is likely to occur as a drug side effect in approximately one out of seven women with PMS taking a moderate dose of SSRIs, and lack of energy is likely to occur as a drug side effect in approximately one out of every nine women.

The overall quality of the evidence was rated as low to moderate, the main weakness being poor reporting of methods in the included studies. At least 21 of the studies received funding from pharmaceutical companies.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Most women of reproductive age experience premenstrual symptoms that are associated with the rise and fall of ovarian sex steroids precipitated by ovulation (Rapkin 2008). Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is distinguished from 'normal' premenstrual symptoms by the degree of distress it causes or its detrimental effect on daily functioning, or both (O'Brien 2011). The physiology of PMS is complex and the disorder is poorly understood (Freeman 2012). It may be associated with the actions of serotonin and gamma‐aminobutyric acid, which are neurotransmitters influenced by the menstrual cycle. Abnormal function or deficiency of these neurotransmitters may cause increased sensitivity to progesterone, precipitating PMS symptoms (Baker 2012).

Definitions of PMS vary, and a wide range of psychological and physical symptoms has been reported. The key characteristic of PMS is the timing of symptoms, which occur only during all or part of the two weeks leading up to menstruation (the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle). Symptoms disappear by the end of menstruation and do not recur before ovulation, giving a symptom‐free interval of at least one week. PMS is cyclical, and occurs in most menstrual cycles (O'Brien 2011). Psychological symptoms can include irritability, depression, anxiety, mood swings, a flat mood (anhedonia) and lethargy. Physical symptoms may include breast tenderness, weight gain, bloating, muscle or joint pain, headache and swelling of the extremities (hands and feet). A clinical diagnosis requires that symptoms are confirmed by prospective recording for at least two menstrual cycles and that they cause substantial distress or impairment to daily life (for example activities at home, work or school, social activities, hobbies, interpersonal relationships) (ACOG 2000; Baker 2012; Epperson 2012; O'Brien 2011). As collecting multiple, daily data points is a laborious process, most diagnoses of PMS are made based on a woman's own perception of her problem. Hence it is suggested that up to 50% of women with reported PMS do not meet the clinical criteria for the disorder (Plouffe 1993). PMS in this review is defined as symptoms meeting the clinical criteria described above.

A severe form of PMS is known as premenstrual dysphoria or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), and was previously also known as late luteal phase dysphoric disorder (LLPDD) (O'Brien 2011). PMDD is characterised by severe symptoms occurring for a week before each menstrual period and remitting in the week after menstruation, over a period of at least a year. According to American Psychiatric Association (APA) criteria, in their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version 4 (DSM IV), at least five of the following symptoms must occur for most of the week prior to menstruation: depression, anxiety, mood swings, irritability (at least one of these four), decreased interest in usual activities, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, appetite changes, sleep disturbance, feeling overwhelmed, and physical symptoms (APA 2000). Symptoms should remit within a few days of menstruation. This definition has been questioned because it focuses on severe psychological symptoms while placing relatively little importance on physical symptoms, and may exclude some women with debilitating symptoms that do not meet these specific criteria (O'Brien 2011).

DSM criteria are currently being updated to include PMDD as a new diagnostic category rather than (as previously) a mood disorder needing further research. Although the proposed DSM V criteria for PMDD are similar to those of DSM IV, they differ in the following respects (Epperson 2012):

symptoms must occur during the final week before menstruation, but do not need to be present most of the time;

symptoms are not required to remit within a few days of menstruation, but should improve and should be minimal (if not absent) in the week following menstruation;

mood lability and irritability are the leading two symptoms;

symptoms cause clinically significant distress or interference with activities at work or school or at home, or both (previously there was no mention of clinically significant distress or of activities at home);

PMDD symptoms are not due to an ongoing medical disorder or substance‐induced condition.

There is a wide variation in estimates of the prevalence of PMS, but it is estimated that 15% to 20% of women of reproductive age have PMS with significantly impaired functioning, and a further 3% to 8% have PMDD. Thus approximately one in five women of reproductive age are affected (Pearlstein 2007).

There is currently no haematological or biochemical test for PMS, and studies have not shown consistent differences in cyclical hormone levels. In the absence of any objective parameter to measure or diagnose PMD, clinicians and researchers rely largely on validated scales in which a woman self‐rates her symptoms. The most widely used self‐rating tool is the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP), which is a prospective scale that focuses largely on psychological rather than physical symptoms (O'Brien 2011).

Description of the intervention

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of drugs that are believed to inhibit the absorption of serotonin, a naturally occurring chemical which acts as a messenger between brain cells (a neurotransmitter). Changing the balance of serotonin appears to improve neurotransmission and enhance mood.

SSRIs are most commonly used to treat depression and anxiety disorders, and appear to take four to eight weeks to reach clinical efficacy in these disorders (Freeman 1999). However, it has been shown that SSRIs may become effective for PMS in a matter of days, and usually within four weeks from the start of treatment (Steiner 1995). This may be due to the cyclical nature of PMS and may reflect SSRI action at a different receptor site to that involved in affective disorders (Sundblad 1997).

The rapid efficacy of SSRI treatment in PMS permits the use of intermittent dosing regimens. For treatment of PMS a relatively small dose of SSRI is generally used. Administration can be:

continuous, SSRI is taken every day throughout the menstrual cycle;

luteal or intermittent, SSRI is taken only during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (i.e. from estimated ovulation to menstruation). The SSRI is started about 14 days prior to expected menstruation, based on a woman's usual cycle length;

semi‐intermittent, taken every day, with a low SSRI dose during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and a higher dose in the luteal phase;

as required, SSRI is started at the onset of PMS symptoms and continued until the onset of menstruation.

It is suggested that avoidance of continuous use may reduce the risk of side effects of SSRIs, which can include anxiety, dizziness, insomnia, sedation, gastrointestinal disturbance, headache, loss of libido and anorgasmia (inability to achieve orgasm) (Baker 2012; Pearlstein 2002).

SSRIs are licensed for treating PMMD in the United States, but not in Europe (Ismail 2006).

Other interventions used for premenstrual symptoms include lifestyle modification (for example exercise, smoking cessation, weight management), herbal remedies (for example vitex agnus castus), calcium, vitamin C, hormones, gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, danazol and (rarely and as a last resort) hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy (Baker 2012). Uncertainty about the pathogenesis of PMS has led to many other treatments being suggested as possible therapies. It has been suggested that, as there is a substantial placebo response, a large number of uncontrolled trials have resulted in a proliferation of claims for ineffective therapies (Magos 1986).

Different PMS symptoms may have separate causes and therefore require different treatment strategies (O'Brien 2011). It is suggested that most women with severe PMS require either hormonal medication (estrogen with or without progestin) or a psychotropic medication (such as an SSRI) for symptom relief (Baker 2012). As the disorder is usually chronic, and may require treatment for 20 years or more, the long‐term effects of an intervention are important (Rapkin 2008).

Some of the interventions are the subject of other Cochrane reviews, either published or in preparation (as of April 2013), as follows.

Oral contraceptives containing drosperinone

This review found that drospirenone 3 mg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg may be beneficial for PMDD. It was unclear whether oral contraceptives containing drospirenone were effective for women with less severe symptoms, or were better than other oral contraceptives. A strong placebo effect was noted (Lopez 2012).

Chinese herbal medicines

This review found that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of Chinese herbal medicines for PMS (Jing 2009).

Progesterone

This review found that it was unclear whether or not progesterone is an effective treatment for PMS (Ford 2012).

Acupuncture

This review is in preparation. The protocol has been published (Yu 2005).

Vitex agnus castus

This review is in preparation. The protocol has been published (Shaw 2003).

Non‐contraceptive estrogen‐containing preparations for controlling symptoms of PMS

This review is in preparation. The protocol has been published (Naheed 2013).

How the intervention might work

Serotonin levels appear to vary during the menstrual cycle under the influence of estrogen and progesterone (Baker 2012). SSRIs may increase the amount of serotonin available for neurotransmission.

It has been noted that treatments that enhance the action of serotonin improve premenstrual irritability and low mood with a rapid onset of action, which suggests a different mechanism of action than in the treatment of depression. Neurosteroids such as progesterone metabolites may be responsible for the rapid action of SSRIs in this context (Pearlstein 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

In view of the debilitating symptoms and economic cost of PMS, and the likelihood that it will persist long‐term, it is important to confirm and quantify the effectiveness and safety of SSRIs for treating this disorder. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2002.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of SSRIs for treating premenstrual syndrome.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion. We excluded non‐randomised studies (for example studies with evidence of inadequate sequence generation such as alternate days, patient numbers) as they are associated with a high risk of bias. Crossover trials were eligible but it was planned that only data from the first phase would be included in meta‐analyses.

Types of participants

Studies of women of any age who met the medically defined diagnostic criteria for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) were eligible for inclusion. Diagnosis must have been made prior to inclusion in the trial by a general practitioner (GP), hospital clinician, or other healthcare professional. Diagnosis of PMS requires that symptoms are confirmed by prospective recording for at least two menstrual cycles and must cause substantial distress or impairment to daily life. Diagnosis of PMDD must meet established psychiatric diagnostic criteria.

Studies of women with only a self‐diagnosis of PMS were excluded.

Types of interventions

Studies of SSRIs, at any dose and in any dosing regimen for any duration longer than one menstrual cycle, versus placebo were eligible.

Trials of tricyclic antidepressants were excluded. Even when described as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, these drugs are not selective and act in a different manner to SSRIs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary

1. Self‐rated overall premenstrual symptoms, measured using a validated prospective screening tool (e.g. Moos' MDQ, Abraham's classification) or by pre‐defined medical diagnostic criteria

2. Adverse events (all adverse events, specific adverse effects, withdrawals for adverse effects)

Secondary

3. Specific symptoms of PMS: psychological, physical and functional symptoms, irritability

4. Response rate (according to how response defined in individual studies)

5. Overall withdrawals from study

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all published and unpublished RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria. The search was conducted without language restriction and in consultation with the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

Electronic searches

For the latest search (February 2013), we searched the following electronic databases, trials registers and websites: Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Specialised Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO.

Other electronic sources of trials included: a. trials registers for ongoing and registered trials, http://www.controlled‐trials.com, http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home, http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx; b. Web of Knowledge (including the citation database Web of Science).

For versions of the review prior to 2013, we also searched http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org/ for the results of clinical trials of marketed pharmaceuticals. However, this database has not been accessible since June 2012.

See Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3 for database search strategies.

Searching other resources

a) We handsearched the reference lists of articles retrieved by the search.

b) For the 2002 version of this review:

drug and pharmaceutical companies manufacturing SSRIs (fluoxetine: Eli Lilly; paroxetine: Smith Kline Beecham; sertraline: Invicta; fluvoxamine: Solvay; Citalopram: Du Pont) were contacted to request other published or unpublished trials;

the personal databases on PMS therapies maintained by the authors were searched for relevant articles;

the UK‐based National Association for Premenstrual Syndrome (NAPS) was also contacted for relevant articles.

c) For the 2013 version of this review:

attempts were made to contact the following drug and pharmaceutical companies manufacturing SSRIs (Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Forest Labs) to request other published or unpublished trials. However, only one company (GlaxoSmithKline) replied.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The 2013 update

For the 2013 update of this review, JM conducted an initial screen of titles and abstracts retrieved by the search and retrieved the full texts of all potentially eligible studies. Two review authors (JM and KMW) independently examined these full text articles for compliance with the inclusion criteria and selected studies eligible for inclusion. We corresponded with study investigators, as required, to clarify study eligibility. Disagreements as to study eligibility were resolved by discussion or by a third review author.

Previous versions of the review

For the original version of this review (2002), all publications identified in the search strategy were assessed by two authors (PWD and KMW) working in parallel. Selection of the trials for inclusion was performed by PWD and KW. Any disagreements were assessed by a third review author and other uncertainties regarding inclusion were resolved by contacting the primary study authors. For the 2008 update of the review, an additional 22 studies were identified by JB and JM, who independently checked the potentially eligible studies.

Data extraction and management

For the 2013 update of this review, two review authors (JM and JB) independently extracted data from the eligible studies. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third review author. Data extracted included study characteristics and effect estimates.

Where there were multiple arms in a study with a common placebo, the placebo numbers were divided as equally as possible between the arms (see footnotes in forest plots).

Where studies had multiple publications, the main trial report was used as the reference and additional details were derived from secondary papers. We corresponded with study investigators for further data on methods and results, as required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the 2008 and 2013 updates, two review authors independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011). This assesses: allocation (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors; and completeness of outcome data.

For the 2013 update, new studies were also assessed for risk of selective reporting bias, which refers to the selective reporting of some outcomes (for example positive outcomes) and the failure to report others (for example adverse events), and for other potential sources of bias.

Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third review author. We described all judgements fully and presented the conclusions in the 'Risk of bias' table. Differences in study quality were incorporated into the interpretation of review findings by means of sensitivity analyses.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous data (for example symptom scores), as similar outcomes were reported on different scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) between the end scores or change scores for the control and intervention groups of each study. End scores were extracted in preference to change scores, where available, as they may be preferable for outcomes which are unstable or difficult to measure precisely (Higgins 2011). For dichotomous data (for example withdrawal rates), we used the numbers of events in the two groups to calculate Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (ORs). We presented 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all outcomes. We compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies with how they were presented in the review, taking account of legitimate differences.

Where there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in the rate of adverse events, we calculated numbers needed to harm (NNH) for the moderate dose (that is an estimate of the number of women who would need to receive treatment using a moderate dose in order for one additional harm to occur).

Standard mean differences were interpreted using the following rule of thumb: 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect (Cohen 1988a; Higgins 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to include only first‐phase data from crossover trials.

Dealing with missing data

The data were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible and attempts were made to obtain missing data from the original trialists. Where these were unobtainable, only the available data were analysed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis in order to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We assessed statistical heterogeneity by the I2 statistic.

A rough guide to interpretation of I2 values is as follows (Higgins 2011):

0% to 40%, might not be important;

30% to 60%, may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%, may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%, considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data.

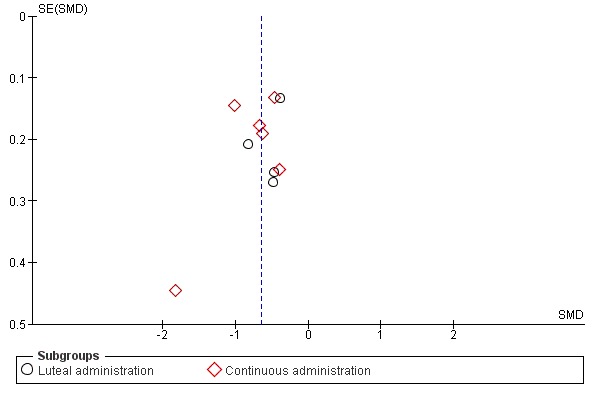

If there were 10 or more studies in the analysis of a primary outcome, we used a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

If the studies were sufficiently similar, we combined the data using random‐effects models to compare SSRIs versus placebo. The primary outcome was stratified by SSRI dose (low, moderate or high, see Table 20) and by type of administration (luteal or continuous). The SMDs of end scores and change scores were analysed separately and were not pooled since the differences in the standard deviations reflect differences in the reliability of the measurements and not differences in measurement scales (Higgins 2011).

1. Classification of SSRI doses used by included studies.

| SSRI | Low dose | Moderate dose | High dose |

| Fluoxetine* | 10 mg daily | 20 mg daily | 60 mg daily |

| Sertraline* | 25‐50 mg daily | 100 ‐105 mg daily | |

| Paroxetine* | 10‐12.5 daily | 20‐30 daily | |

| Citalopram** | 20‐50 daily | ||

| Escitalopram** | 10 mg daily | 20 mg daily |

* Based on suggested doses for PMDD (Micromedex 2013)

**Based on suggested doses for depression (Micromedex 2013) as PMDD data not available

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where data were available, we conducted subgroup analyses to determine the separate evidence for the primary outcomes within the following subgroups:

administration mode (continuous versus intermittent or as required);

placebo run‐in versus non‐placebo run‐in.

If we detected substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we planned to explore possible explanations by checking the data, conducting sensitivity analyses (see below), and by examining clinical and methodological differences between the studies, to check whether there was a plausible explanation. Where there were three or more studies using the same SSRI and dose we examined whether the findings differed in subgroups using the same SSRI. We planned to take statistical heterogeneity into account when interpreting the results, especially if there was any variation in the direction of effect.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes to determine whether the conclusions were robust to arbitrary decisions made regarding the eligibility of the studies and analysis. These analyses included consideration of whether the review conclusions would have differed if: 1. eligibility was restricted to studies without high risk of bias, defined as studies at low risk of selection bias; 2. a fixed‐effect model had been adopted.

Summary of findings table

A 'Summary of findings' table was generated using GRADEPRO software to evaluate the overall quality of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes, using GRADE working group criteria (that is study limitations (risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Judgements about the quality of the evidence (high, moderate or low) were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Searches up to 2009

Ninety‐six potentially relevant articles were retrieved in searches up to 2008. Twenty‐eight studies were identified as RCTs that used SSRIs in the management of PMS and were included.

Search update in 2013

Nineteen potentially eligible articles were retrieved in the 2013 search. Six were included as new studies (Eriksson 2008; Freeman 2010; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 1996a; Glaxo 2001; Steiner 2008) and three (Glaxo 2002; Miller 2008; Wu 2008) were excluded. Two articles were additional publications for included studies (Freeman 2004; Landen 2007), six were the abstracts of studies already included, and two were ongoing studies (Yonkers 2007; Yonkers 2010).

In the 2009 version of the review, the 28 included studies were divided into 40 comparisons each with a separate study reference. For the 2013 update, data relating to the same study were combined under a common study reference. Three previously included studies were excluded in the update after discussion between the review authors: one (Veeninga 1990) because the participants were self‐diagnosed and did not clearly meet medically defined diagnostic criteria for PMS, and two (Sundblad 1992a; Sundblad 1993a) because the intervention was clomipramine, which is not an SSRI.

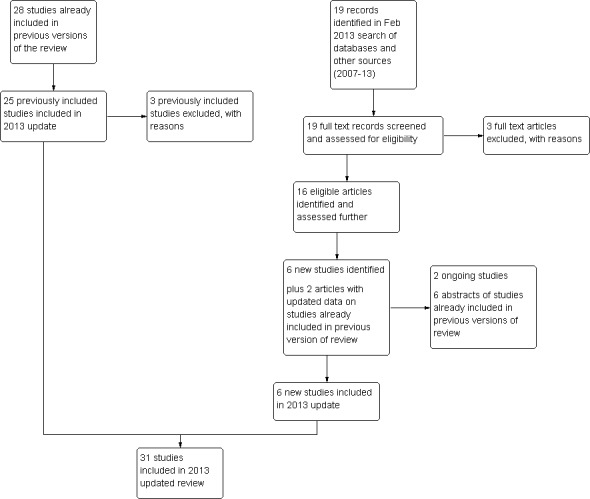

Thus, a total of 31 studies are now included (n = 4372 ), comprising 25 studies from the previous version of the review and six new studies. See the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Study design and funding source

All studies were RCTs. Fifteen reported that they were multi‐centred (Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 1996a; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 2002; Kornstein 2006; Landen 2007; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008; Yonkers 1997).

Most studies were of parallel‐group design but six used a crossover design (Halbreich 1997; Jermain 1999; Menkes 1992; Su 1997; Wood 1992; Young 1998). The first‐arm data (before crossover) for overall symptom reduction could be extracted for only one of these trials (Jermain 1999); the remaining crossover trials were not used in the data pooling. Where data were incomplete, all authors were contacted. However, no additional data were received.

Twenty‐one studies were solely or partially funded by pharmaceutical companies (Cohen 2002; Eriksson 1995; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 2010; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 1996a; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 1997; Halbreich 2002; Jermain 1999; Kornstein 2006; Landen 2007; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005, Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008; Stone 1991; Yonkers 1997) or had pharmaceutical company employees among their authors (Cohen 2004). Seven studies were funded independently (Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Menkes 1992; Su 1997; Wikander 1998; Wood 1992; Young 1998). The source of funding was unclear in three studies (Arrendondo 1997; Crnobaric 1998; Ozeren 1997).

Participants

Women in most of the included studies were aged from 18 to 45 years (range 18 to 49 years) where reported, though one study enrolled teenagers aged 15 to 19 years (Freeman 2010).

Most of the studies diagnosed women with PMS or PMDD by means of validated self‐rating symptom scales completed over multiple menstrual cycles, or by means of psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Measures used were:

Penn Daily Symptoms Rating Scale (Arrendondo 1997; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Kornstein 2006);

Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) (Cohen 2002);

DSM III or IV diagnostic criteria for PMDD or LPDD (Cohen 2004; Crnobaric 1998; Eriksson 1995; Eriksson 2008; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 1996a; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 1997; Halbreich 2002; Jermain 1999; Landen 2007; Menkes 1992; Miner 2002; Ozeren 1997; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008; Stone 1991; Wikander 1998; Wood 1992; Yonkers 1997; Young 1998);

Visual analogue scale (VAS) (Su 1997).

In most studies women were recruited from clinical settings (for example psychiatric, gynaecological or PMS outpatient clinics) or via media, television, or local newspaper advertising. Five studies provided no details of recruitment methods.

Exclusion criteria varied, but most of the studies excluded women with the following characteristics:

current or recent major or Axis 1 psychiatric diagnosis (other than PMDD);

other clinically significant disease;

recent hormonal contraceptive use;

current or planned pregnancy;

use of concurrent medication (including psychotropic drugs).

Interventions

Description of the interventions

SSRIs used were:

sertraline 50 to 150 mg (Arrendondo 1997; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Halbreich 1997; Halbreich 2002; Jermain 1999; Kornstein 2006; Yonkers 1997; Young 1998);

fluoxetine 10 to 20 mg (Cohen 2002; Crnobaric 1998; Menkes 1992; Miner 2002; Ozeren 1997; Pearlstein 1997; Steiner 1995; Stone 1991; Su 1997; Wood 1992);

paroxetine 5 to 25 mg (Cohen 2004; Eriksson 1995; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 1996a; Glaxo 2001; Landen 2007; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008);

escitalopram 10 to 20 mg (Eriksson 2008; Freeman 2010);c

italopram 10 to 30 mg (Wikander 1998).

The timing regimen of the intervention varied as follows (some studies included more than one):

luteal or intermittent (Cohen 2002; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 2004; Freeman 2010; Halbreich 1997; Halbreich 2002; Jermain 1999; Kornstein 2006; Landen 2007; Miner 2002; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008; Wikander 1998; Young 1998);

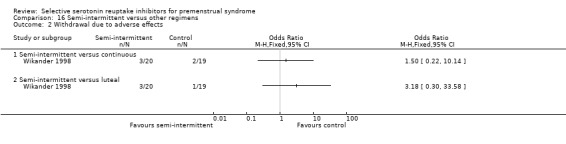

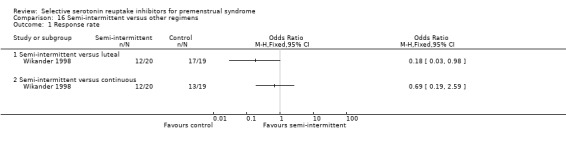

semi‐intermittent (low dose in follicular phase, higher dose in luteal phase) (Wikander 1998);

continuous (Arrendondo 1997; Cohen 2004; Crnobaric 1998; Eriksson 1995; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 1996a; Kornstein 2006; Landen 2007; Menkes 1992; Ozeren 1997; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 1995; Stone 1991; Su 1997; Wikander 1998; Wood 1992; Yonkers 1997).

The number of treatment cycles for these interventions varied from two to six.

Three studies compared luteal versus continuous (Freeman 2004; Landen 2007; Wikander 1998) or semi‐intermittent (Wikander 1998) SSRI dosing strategies. A fourth study (Kornstein 2006) included an 'as required' regimen, whereby women took an SSRI from symptom onset to menstruation. These data were not included in the review because the 'as required' regimen was administered after two cycles of luteal administration and had a duration of only one cycle, and thus did not meet our inclusion criteria.

Some of the studies had more than one active treatment arm. They included different drug doses (Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Eriksson 2008; Kornstein 2006; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2008; Wikander 1998) or different drug timing regimens (Freeman 2004; Landen 2007; Miner 2002; Wikander 1998) as well as a placebo group.

The following studies included a placebo run‐in period: Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Freeman 2004; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 1996a; Halbreich 1997; Halbreich 2002; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Stone 1991; Yonkers 1997.

Review outcomes reported in the included studies

Primary review outcomes

1. Overall premenstrual symptoms

The following 15 studies reported total self‐rated symptom scores in a form that allowed pooling of the data: Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Halbreich 2002; Jermain 1999; Kornstein 2006; Miner 2002; Ozeren 1997; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Yonkers 1997. These studies utilised a range of self‐rated tools, which are identified by footnotes in the forest plots.

Three other studies reported self‐reported total symptom scores in a form that did not allow pooling of the data (Eriksson 2008; Freeman 2010; Glaxo 1996)

2. Adverse effects

Sixteen studies reported withdrawals due to adverse events in a form that allowed pooling of the data (Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Eriksson 1995; Eriksson 2008; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 2002; Landen 2007; Ozeren 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008; Yonkers 1997).

The following 17 studies reported individual adverse effects in a form that allowed pooling of the data: Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Eriksson 1995; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Glaxo 1996a; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 2002; Kornstein 2006; Landen 2007; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008; Stone 1991.

Secondary review outcomes

3. Specific symptoms of PMS

A wide variety of symptom measurement tools were used by the included studies, please see Table 21.

2. Outcome measures utilised by included studies.

| Outcome Measure | Studies | Description |

| Daily Symptom Report | Kornstein 2006 | 17 common PMS symptoms self rated daily on a 5‐point scale (from 0=none to 4=severe/overwhelming/unable to function). Mood (anxiety, irritability, depression, nervous tension, mood swing, feeling out of control); Behavioural ( poor coordination, insomnia, confusion/poor concentration, headache, crying, fatigue); Pain (aches, cramps, breast tenderness); Physical symptoms (food cravings, swelling); Distress. |

| Clinical Global Impression Severity of Illness (CGI‐S) | Freeman 1999, Kornstein 2006, Pearlstein 2005, Miner 2002, Steiner 2005, Yonkers 1997; Cohen 2004, Freeman, 1999, Freeman, 1999, Halbreich 2002, Pearlstein 1997, Yonkers 2006 | Clinician rated. 7‐point scale (1= not ill to 7 = extremely ill) |

| Clinical Global Improvement (CGI‐I) | Kornstein 2006, Landen 2007, Crnobaric 1998, Miner 2002, Steiner 2005, Menkes 1993, Yonkers 1997, Cohen 2004, Halbreich 1997, Freeman, 1999, Halbreich 2002, Yonkers 2006, Steiner 2008 | Clinician rated. 7‐point scale (1= very much better to 7 = very much worse) |

| Patient Global Evaluation (PGE) | Kornstein 2006, Landen 2007, Steiner 2005 a,b; Yonkers 1997, Halbreich 2002 | Self rated 7‐point ordinal scale (from 1 = very much improved to 7 = very much worse) that rates the degree of overall improvement in PMS symptoms compared with pre‐treatment baseline. Assessments were based on the past week. |

| Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Scale | Kornstein 2006, Halbreich 2002 | Self rated 5 point ordinal scale 1 = very poor to 5 = very good. A total score computed by adding the first 14 items, dividing by 70 (maximum total score) and multiplying by 100. |

| Social Adjustment Scale Self Report (SAS‐SR) | Kornstein 2006, Yonkers 1997, Halbreich 2002 | Self rated 55‐item scale assessing work and or housework, interpersonal relationships, and social and leisure activities during the previous week. |

| Calender of Premenstrual Experience (COPE) | Young 1998, Crnobaric 1998, Ozeren 1997, Jermain 1999, Wood 1992 | Self rated 22 symptoms grouped into behavioural (14 symptoms,) and physical (8 symptoms) categories. Symptoms rated daily from 0 (none) to 3 (severe). |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Menkes 1993 | 0‐100mm for irritability, depressed mood, increased appetite/carbohydrate cravings, breast tenderness and bloating. 0 = no complaints to 100 = maximum complaints. |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Menkes 1992 | 0‐100mm for irritability, depressed mood, increased appetite/carbohydrate cravings, breast tenderness and bloating. 0 = no complaints to 100 = maximum complaints. |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Landen 2007 | 0‐100mm, no details as to symptoms included in scale. |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Steiner 1995 | 0‐100mm for tension, irritability and dysphoria with 0 being no symptoms and 100 being severe or extreme symptoms. The mean of the three scales was used determine the total psychological ‐ symptom score. |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Pearlstein 2005, Steiner 2005, Cohen 2004; | 0‐100mm with 0 being 'not at all' and 100 being 'extreme'. Eleven symptoms were recorded irritability, tension, affective lability, depressed mood, decreased interest, difficulty concentrating, lack of energy, change in appetite, change in sleep pattern, feeling out of control and physical symptoms. VAS Mood is a composite score of irritability, tension, depressed mood and affective lability. |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Su 1997 | A 16‐item extended version of the VAS scale. |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Wikander 1998, Eriksson 1995 | 0‐100mm scale with 0 = no complaints and 100 = maximal complaints. Symptoms include irritability, depressed mood, tension, anxiety, increased appetite, bloating, breast tenderness. |

| Premenstrual tension scale (PMTS) ‐ observer and self rated | Landen 2007, Steiner 1995, Miner 2002, Steiner 2005, Cohen 2002, Su 1997, Yonkers 2006 | 36‐item scale completed by patient and 10‐item scale completed by therapist/clinician. Both scales rate premenstrual symptoms on a given day and the score can range from 0 to 36 indicating all symptoms present and severe. |

| Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) | Landen 2007, Pearlstein 2005, Miner 2002, Steiner 2005, Cohen 2004 | Assesses the extent to which their symptoms affect work, social life/leisure activities and family life/home responsibilities (scale 0 = not at all impaired to 10 = cannot function). |

| Penn Daily Symptom Rating Form (DSR) | Arrendondo 1997, Freeman 2004, Freeman 1999 | Depression, feeling hopeless or guilty, anxiety/tension, mood swings, irritability/anger, decreased interest, concentration difficulties, fatigue, food cravings/increased appetite, insomnia or hypersomnia, feeling out of control/overwhelmed, poor coordination, headache, aches, swelling/bloating/weight gain, cramps and breast tenderness. Rated on a five point scale from 0‐4 (no disruption to severe disruption). Scores were calculated by adding the ratings of cycle days 5 through 10 for post menstrual scores and by adding the scores for the 6 days before menses for the premenstrual scores. |

| Subject Global Ratings of Functioning | Freeman 2004 | Depression, feeling hopeless or guilty, anxiety/tension, mood swings, irritability/anger, decreased interest, concentration difficulties, fatigue, food cravings/increased appetite, insomnia or hypersomnia, feeling out of control/overwhelmed, poor coordination, headache, aches, swelling/bloating/weight gain, cramps and breast tenderness. Rated on a five point scale from 0‐4 (no disruption to severe disruption). Scores were calculated by adding the ratings of cycle days 5 through 10 for post menstrual scores and by adding the scores for the 6 days before menses for the premenstrual scores. |

| Prospective Record of the Impact and Severity of Menstrual Symptomatology Calendar | Steiner 1995 | No details in paper. |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM‐D) (HRSD) | Crnobaric 1998, Yonkers 1997, Halbreich 1997, Freeman, 1999, Halbreich 2002, Pearlstein 1997, Yonkers 2006 | No details in paper. |

| Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) | Miner 2002, Cohen 2002, Yonkers 1997, Halbreich 2002, Yonkers 2006 | Scale consisting 21 numbered items grouped into 11 categories (depressed/hopeless/worthless; tension; mood swings/ feelings hurt; irritability; less interest in activities; difficulty concentrating; lethargy; increased appetite/cravings; sleeping more/insomnia; overwhelmed/out of control; breast tenderness/bloating/headache/joint or muscle pain.). It has three additional questions measuring impairment of social functioning (at work/school/home; hobbies or social activities; relationships). Severity of each symptom is rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extreme). Mean score was calculated as average scores for the five most symptomatic days from six days before through to the first days of menses. Yonkers used an updated version using 24 items. |

| Daily Assessment Form (DAF) | Stone 1991 | 33‐item checklist used to assess each of the 10 symptom categories found in the DSM‐III‐R criteria. Symptoms are rated with a 6‐point rating scale ranging from 1 (none) to 6 (extreme). |

| Global Assessment Scale (GAS) | Stone 1991, Pearlstein 1997 | Self‐assessed scale with 18 summary scale scores reflecting composite ratings from 4‐14 items scored from 1(no premenstrual change) to 6 (extreme change). |

| Premenstrual Assessment Form (PAF) | Menkes 1993 | Includes irritability, low energy, mood swings, mastalgia, depression, bloating, impulsivity, abdominal pain, anxiety, food cravings. Scale of no change or worse to remitted. |

| Daily Ratings Form (DRF) | Menkes 1993 | Includes irritability, low energy, mood swings, mastalgia, depression, bloating, impulsivity, abdominal pain, anxiety, food cravings. Scale of no change or worse to remitted. |

| Daily Ratings Form (DRF) | Su 1997 | 21‐item 6‐point scale; including sadness, anxiety, irritability, mood swings, breast pain, bloating, fatigue, food cravings, impaired social and work functioning, impulsivity and global impairment, sleep and sexual interest. |

| Modified Daily Ratings Form (DRF) | Halbeich 1997 | No details in paper. |

| Beck Depression Inventory | Su 1997, Jermain 1999, Wood 1992 | 22‐item patient rated scale assessing depression. Rated on a 4‐point severity scale. |

| Stait Trait Anxiety Inventory State Form | Su 1997, Wood 1992 | No details in papers. |

| Physical symptom checklist | Su 1997 | Designed to detect the side effects of fluoxetine. |

| Profile of Mood State | Wood 1992 | No details in paper. |

| Global Ratings of Functioning and Improvement | Freeman 1999 | 5‐point rating scale using descriptors for each point ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (complete). Functioning rated for work, family life, and social activity with 0 (no disruption) to 4 (severe disruption). |

| Prospective Record of the Impact and Severity of Menstrual Symptomology calendar | Steiner 1995 | No details in paper but completed daily. |

| Quality of Life Scale (QOLS) | Freeman 1999 | Self‐reported measure of various aspects of daily living plus a global assessment of QOL over the past week. The 14 QOLS items are the summary scales of the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire. |

| Premenstrual Tension Scale (PMTS‐O) | Steiner 2008 | Observer‐assessed |

3.1 Psychological symptoms

Ten studies reported psychological symptoms of PMS in a form that allowed pooling of the data (Arrendondo 1997; Cohen 2002; Freeman 1999; Glaxo 2001; Kornstein 2006; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 2005; Yonkers 1997).

3.2 Physical symptoms

Eleven studies reported physical symptoms of PMS in a form that allowed pooling of the data (Cohen 2002; Freeman 1999; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 2002; Kornstein 2006; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 1997; Steiner 1995; Yonkers 1997).

3.3 Functional symptoms

Five studies reported functional symptoms of PMS in a form that allowed pooling of the data (Cohen 2002; Eriksson 2008; Kornstein 2006; Miner 2002; Yonkers 1997).

3.4 Irritability

Eight studies reported irritability in a form that allowed pooling of the data (Cohen 2002; Freeman 1999; Halbreich 2002; Pearlstein 1997; Steiner 2008; Yonkers 1997).

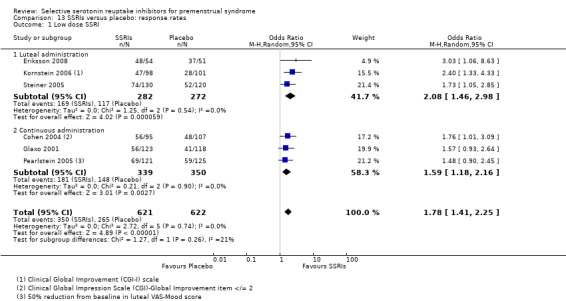

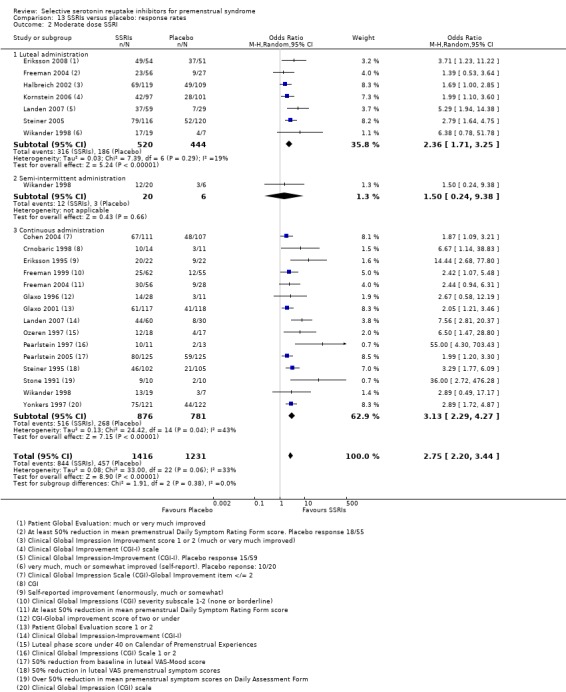

4. Response

Twenty‐one studies reported response rates in a form that allowed pooling of the data (Cohen 2004; Crnobaric 1998; Eriksson 1995; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 2002; Kornstein 2006; Landen 2007; Ozeren 1997; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 1995; Steiner 2005; Stone 1991; Wikander 1998; Yonkers 1997). The definition of response varied across studies and is defined in footnotes in the forest plots.

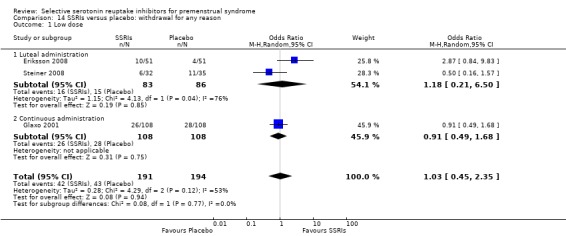

5. Withdrawal for any reason

Fourteen studies reported overall withdrawal rates in a form that allowed pooling of the data (Crnobaric 1998; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Glaxo 1996; Glaxo 2001; Halbreich 2002; Jermain 1999; Ozeren 1997; Steiner 2008; Stone 1991; Yonkers 1997).

For details please see Table 21 and Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐six studies were excluded (see Characteristics of excluded studies), in most cases because they were not properly randomised, were unblinded, were not placebo controlled or did not report the comparison of interest.

Risk of bias in included studies

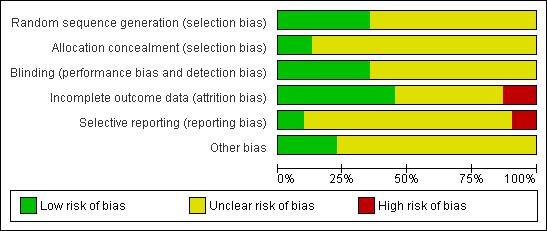

Summaries of the risk of bias assessment are given in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

Eleven studies described adequate methods of randomisation and were rated as at low risk of bias related to sequence generation (Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Halbreich 2002; Landen 2007; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 2008; Yonkers 1997). The other 20 studies did not clearly describe their methods and were rated as at unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

Four studies described adequate methods of allocation concealment and were rated as at low risk of bias in this domain (Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Yonkers 1997). The other 27 studies did not clearly describe their methods and were rated as at unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Eleven studies reported details of double blinding and were rated as at low risk of bias in this domain (Cohen 2002; Cohen 2004; Eriksson 1995; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Freeman 2010; Menkes 1992; Pearlstein 1997; Su 1997; Young 1998). The other 20 studies were described as double blinded but provided no further details and were rated as at unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen studies analysed all or most women by intention to treat, and were rated as at low risk of attrition bias (Cohen 2002; Crnobaric 1998; Eriksson 2008; Glaxo 2001; Landen 2007; Miner 2002; Pearlstein 1997; Pearlstein 2005; Steiner 2005; Steiner 2008; Stone 1991; Su 1997; Wood 1992; Yonkers 1997). Four studies had data missing for over 20% of participants and were rated as at high risk of attrition bias (Halbreich 1997; Jermain 1999; Kornstein 2006; Young 1998). The other 13 studies were at unclear risk of attrition bias due to unclear reporting of numbers randomised or numbers analysed, or failure to include 10% to 20% of participants in the analysis. A number of these studies also imputed a high proportion of data.

Selective reporting

Three studies were rated as at low risk of this bias (Eriksson 1995; Landen 2007; Wikander 1998). These studies prospectively collected data on adverse effects and no potential source of selective reporting bias was identified. Three studies were rated as at high risk of this bias. These studies collected data for efficacy and adverse effects that were not fully reported or not published (Freeman 2010; Glaxo 1996a; Steiner 2008). The other 25 studies were rated as at unclear risk of selective reporting bias. Most of these studies collected data on adverse events retrospectively (often by spontaneous participant report) or did not report adverse events data in an extractable form for either comparison group.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential source of bias was identified in seven studies, and these studies were rated as at low risk for this domain (Eriksson 1995; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Glaxo 2001; Ozeren 1997; Su 1997; Young 1998). The other 24 studies were rated as at unclear risk of other potential bias, in most cases because they excluded placebo responders from the study, were crossover studies (for which only first‐phase data were included in this review), or very few details were reported about the study design.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. SSRIs for premenstrual syndrome: all symptoms (end scores).

| SSRIs compared to placebo ‐ all symptoms (end scores) for premenstrual syndrome | ||||

| Patient or population: women with premenstrual syndrome Settings: community or outpatient Intervention: SSRIs Comparison: placebo ‐ all symptoms (end scores) | ||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Moderate dose SSRI versus placebo Luteal or continuous administration |

The mean score for all symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.67 standard deviations lower (0.46 to 0.84 lower) | 1276 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | SMD ‐0.65 (95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.84) Symptoms were significantly less severe in the SSRI group. The size of the effect was moderate. |

|

Moderate dose SSRI versus placebo Luteal administration |

The mean score for all symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.51 standard deviations lower (0.71 to 0.31 lower) | 457 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | SMD 0.51 (95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.31) Symptoms were significantly less severe in the SSRI group. The size of the effect was moderate. |

| Moderate dose SSRI versus placebo Continuous administration | The mean score for all symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.72 standard deviations lower (0.97 to 0.47 lower) | 843 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | SMD ‐0.72 (95% CI ‐0.97 to ‐0.47) Symptoms were significantly less severe in the SSRI group. The size of the effect was moderate. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD standardised mean difference | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1 Only 4/9 studies overall (2/4 of luteal and 3/7 of continuous administration) described adequate methods of randomisation and allocation concealment; 8/9 studies were at uncertain or high risk of attrition bias. 2 Substantial overall heterogeneity (I squared= 58%), attributable to heterogeneity in continuous administration group (I squared=68%), which included two studies with larger intervention effects. No obvious explanation (though studies used wide variety of assessment tools).

Summary of findings 2. SSRIs for premenstrual syndrome: all symptoms (change scores).

| SSRIs for premenstrual syndrome (change scores) | ||||

|

Patient or population: women with premenstrual syndrome

Settings: community or outpatient

Intervention: SSRIs Comparison: placebo | ||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Moderate dose SSRI versus placebo Luteal administration2 |

The mean moderate dose ssri in the intervention groups was 0.36 standard deviations lower (0.51 to 0.2 lower) | 657 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | SMD ‐0.36 (‐0.51 to ‐0.2) Symptoms were significantly less severe in the SSRI group. The size of the effect was small. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the ccomparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD standardised mean difference | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1 No studies described adequate methods of both randomisation and allocation concealment; one was high risk of attrition bias.

2 Change score data were not extracted for any studies of continuous administration, as all reported end scores.

Summary of findings 3. SSRIs for premenstrual syndrome: withdrawal due to adverse effects.

| SSRIs versus placebo: withdrawal due to adverse effects | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with premenstrual syndrome

Settings: community or outpatient

Intervention: SSRIs Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Placebo | SSRIs | |||||

|

Low dose SSRI versus placebo Luteal or continuous administration |

53 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (60 to 135) | OR 1.76 (1.13 to 2.75) | 1301 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Withdrawal due to adverse effects was significantly more common in the SSRI groups |

|

Mod dose SSRI versus placebo Luteal or continuous administration |

45 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (79 to 142) | OR 2.55 (1.84 to 3.53) | 2447 (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

|

High dose SSRIs versus placebo Continuous administration |

72 per 1000 | 457 per 1000 (207 to 1000) | RR 6.35 (2.88 to 14) | 231 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Only 1/4 studies reported adequate methods of randomisation and allocation concealment.

2 Only 3/15 studies described adequate methods of randomisation and allocation concealment and 7/15 were at unclear or high risk of attrition bias. 3 Single study (n=235), which did not describe adequate method of allocation concealment.

Primary outcomes

1. Total symptoms

Fifteen studies reported total self‐rated symptom scores. Nine studies reported end scores for this outcome (Cohen 2004; Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Halbreich 2002; Jermain 1999; Ozeren 1997; Steiner 1995; Yonkers 1997), four only reported change scores (Cohen 2002; Kornstein 2006; Miner 2002; Steiner 2005) and one reported only descriptive data (Glaxo 1996).

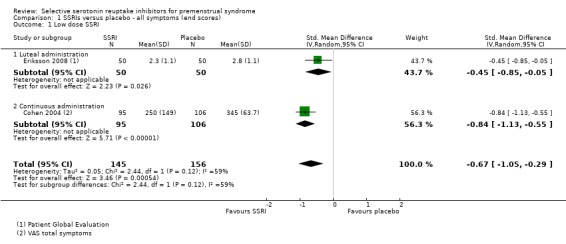

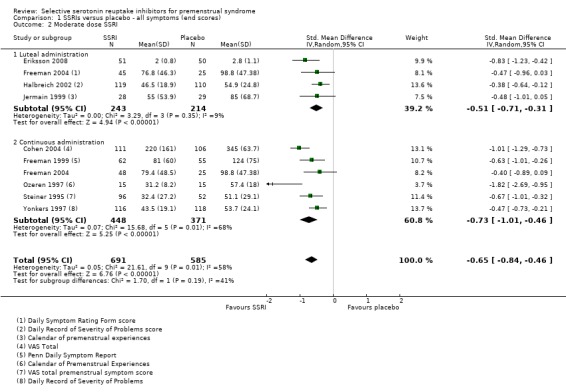

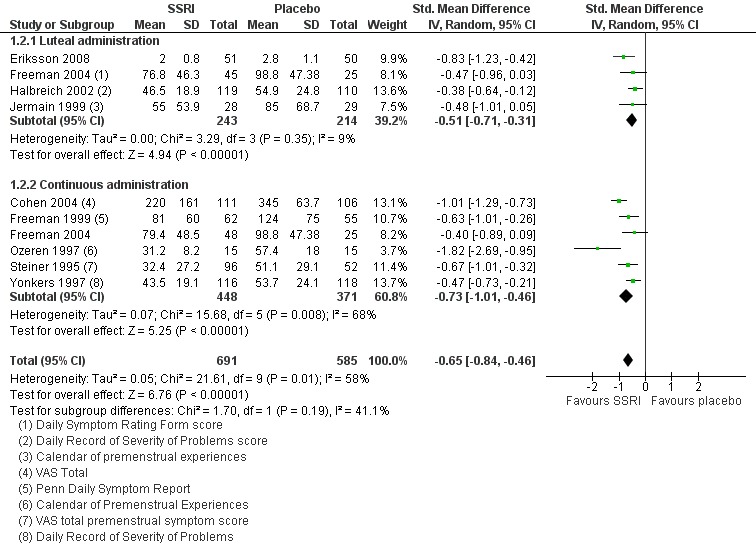

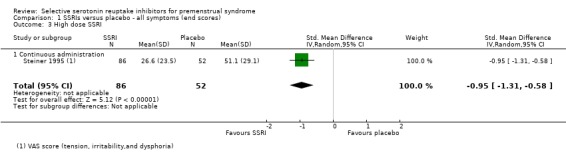

1.1. Total symptoms: end scores

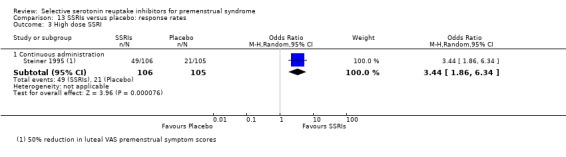

When effects were assessed with end scores, SSRIs reduced overall symptoms significantly more effectively than placebo, with a moderate effect size. This applied to low dose SSRIs (SMD ‐ 0.67, 95% CI ‐0.29 to ‐1.05, two studies, 301 women; I2 = 59%; Analysis 1.1), moderate dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.65, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.84, nine studies, 1276 women; I2 = 58%; Analysis 1.2, Figure 4) and high dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.95, 95% CI ‐ 0.58 to ‐1.31, one study, 134 women; Analysis 1.3). There was substantial heterogeneity for both pooled analyses.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ all symptoms (end scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ all symptoms (end scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ all symptoms (end scores), outcome: 1.2 Moderate dose SSRI.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ all symptoms (end scores), Outcome 3 High dose SSRI.

The analyses were stratified by type of intervention (luteal or continuous). The effects of the intervention were non‐significantly higher in the studies of continuous SSRIs, but there may have been too few studies in each group to show a significant difference.

Five of the studies in this analysis used sertraline. When analysis was restricted to these studies, there was a significant benefit for the SSRI group with a smaller effect size and no heterogeneity (SMD 0.46, 95% CI ‐0.32 to ‐0.60, five studies, 780 women; I2 = 0%). The other studies in this analysis used three different types of SSRI and there were too few using the same type to permit subgrouping.

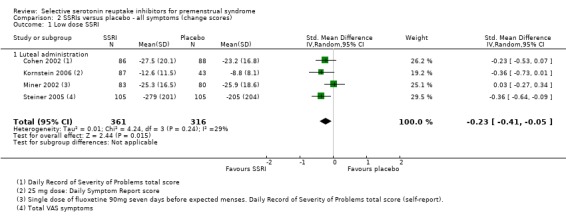

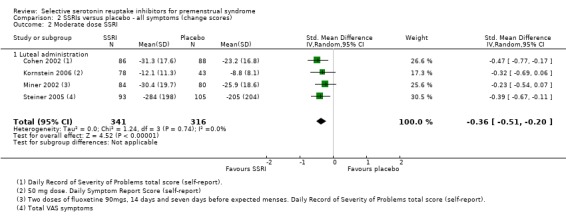

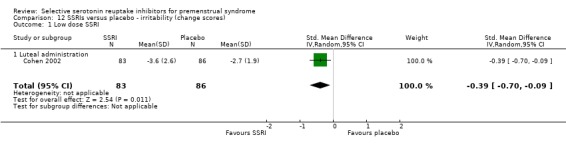

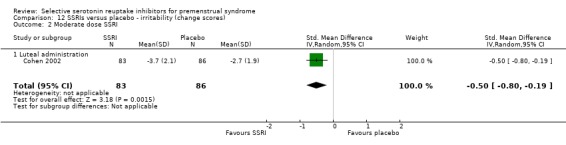

1.2 Total symptoms: change scores

Similarly, when effects were assessed with change scores, SSRIs reduced overall symptoms significantly more effectively than placebo. However, the effect sizes were small. This applied to both low dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.23, 95% CI ‐0.05 to ‐0.41, four studies, 677 women; I2 = 29%; Analysis 2.1) and moderate dose SSRIs (SMD ‐ 0.36, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.51, four studies, 657 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.2, Figure 5). Heterogeneity was low or absent.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ all symptoms (change scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ all symptoms (change scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ all symptoms (change scores), outcome: 2.2 Moderate dose SSRI.

1.3 Total symptoms: descriptive data

Among studies reporting total self‐assessed symptoms scores in a form that was not suitable for meta‐analysis:

Eriksson 2008 reported that women taking escitalopram 10 mg or 20 mg had a significantly greater improvement in four key VAS symptoms than the placebo group;

Glaxo 1996, an unpublished study, reported no significant difference in luteal phase COPE score between paroxetine 20 mg and placebo;

Freeman 2010, an unpublished pilot study (n = 11), reported that women in both arms significantly improved from baseline, with no significant difference between the groups (which was attributed to lack of statistical power in this very small study). Penn Daily Symptom Report (DSR) scores decreased 41% in the drug arm and 28% in the placebo arm.

1.4 Sensitivity analyses

Quality: restricting analysis to the few studies that were at low risk of selection bias (Eriksson 2008; Freeman 1999; Freeman 2004; Yonkers 1997) did not materially change the main findings with regard to total symptom control.

Statistical model: use of a fixed‐effect model did not materially alter the main findings for the primary outcomes.

2. Adverse events

2.1 Withdrawals due to adverse events

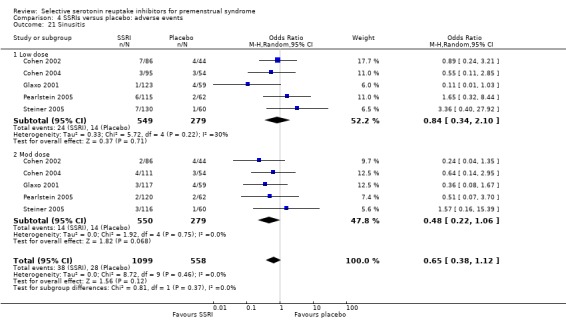

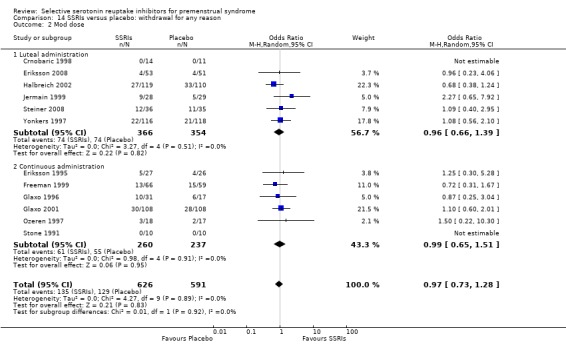

Seventeen studies reported withdrawal from the study due to adverse events and reported results in a form that allowed pooling of the data. Women taking SSRIs were significantly more likely to withdraw from the study than women taking placebo. This applied to women taking low dose SSRIs (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.13, to 2.75, seven studies, 1301 women; I2 = 0%), moderate dose SSRIs (OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.84 to 3.53, 15 studies, 2447 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 3.2, Figure 6) and high dose SSRIs (OR 6.35, 95% CI 2.88 to 14.00, one study; Analysis 3.3). Heterogeneity was absent for these analyses (I2 = 0%).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 SSRIs versus placebo: withdrawal due to adverse effects, Outcome 2 Mod dose.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 SSRIs versus placebo: withdrawal due to adverse events, outcome: 4.2 Mod dose.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 SSRIs versus placebo: withdrawal due to adverse effects, Outcome 3 High dose.

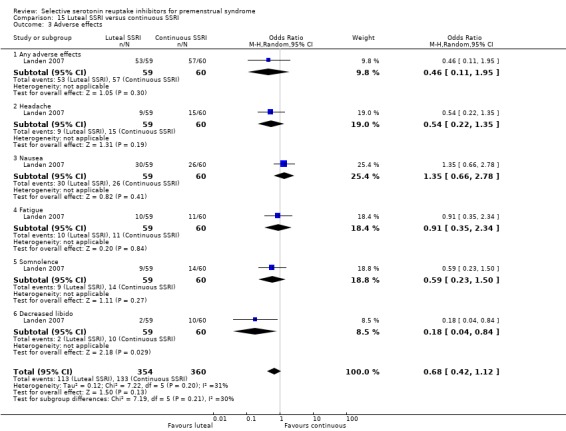

2.2 Individual adverse events

Sixteen studies reported one or more individual adverse events in a form that allowed pooling of the data.

Compared to the placebo group, the SSRI group had higher rates of the following events.

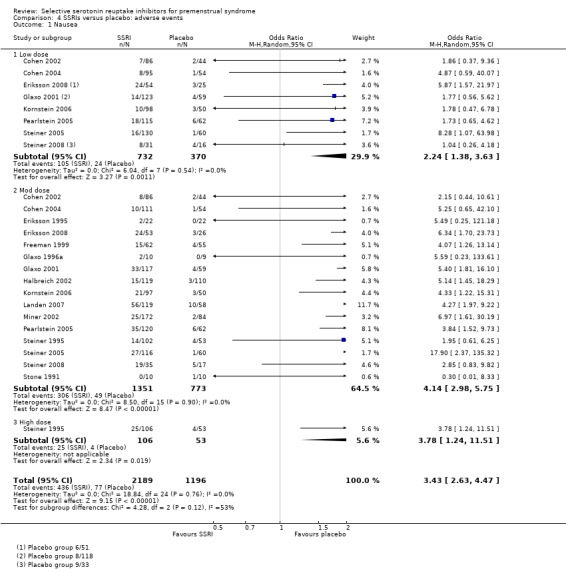

Nausea (OR 3.43, 95% 2.63 to 4.47, 16 studies, 3385 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.1); NNH for moderate dose of 7.

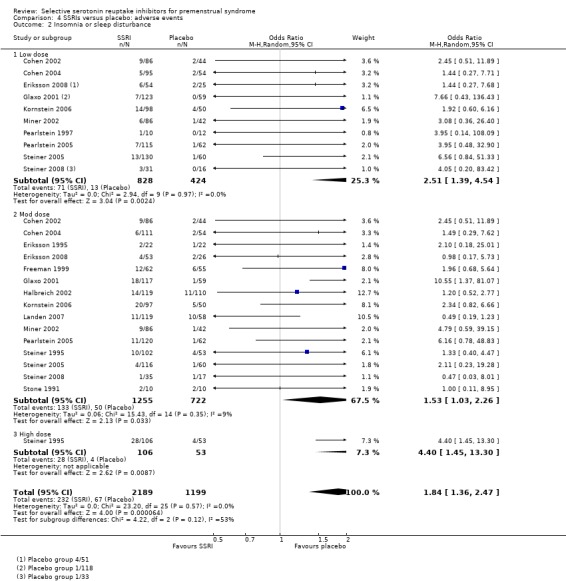

Insomnia or sleep disturbance (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.36 to 2.47, 16 studies, 3388 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.2); NNH for moderate dose of 25.

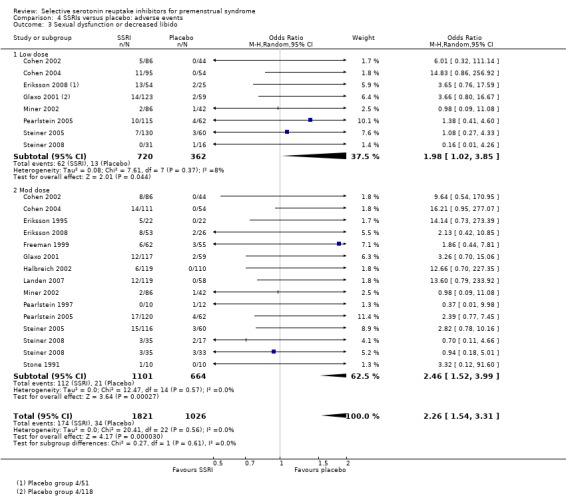

Sexual dysfunction or decreased libido (OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.54 to 3.31, 14 studies, 2847 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.3); NNH for moderate dose of 14.

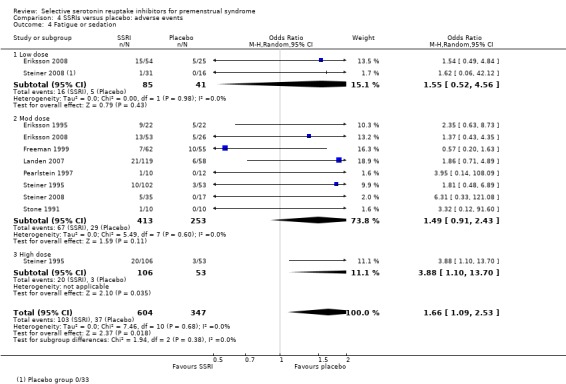

Fatigue or sedation (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.53, eight studies, 951 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.4); NNH for moderate dose of 14.

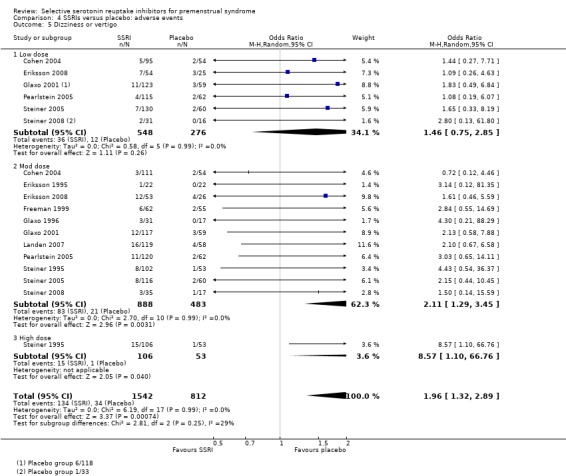

Dizziness or vertigo (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.89, 11 studies, 2354 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.5); NNH for moderate dose of 25.

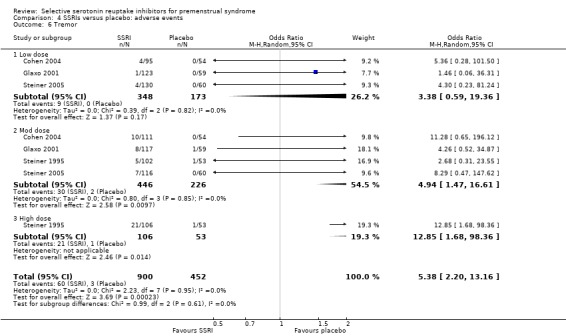

Tremor (OR 5.38, 95% CI 2.20 to 13.16, four studies, 1352 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.6); NNH for moderate dose of 20.

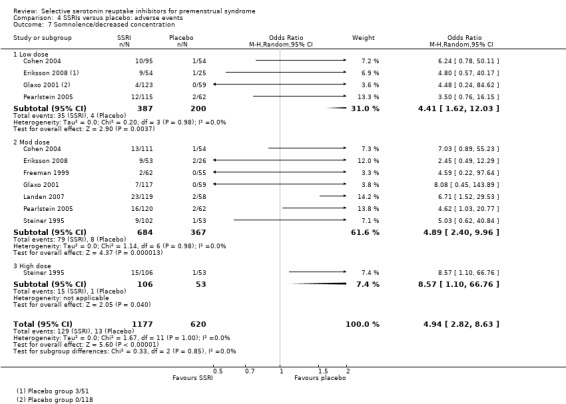

Somnolence and decreased concentration (OR 4.94, 95% CI 2.82 to 8.63, seven studies, 1797 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.7); NNH for moderate dose of 13.

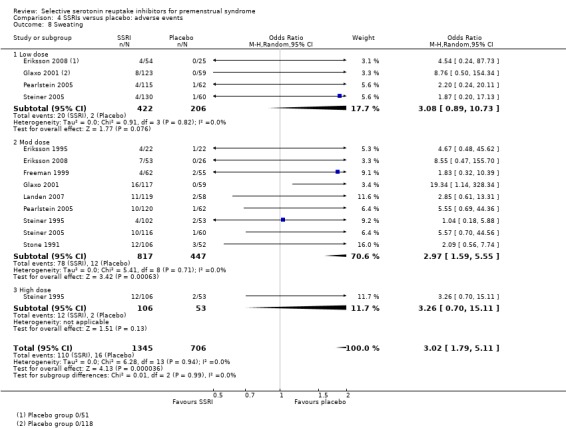

Sweating (OR 3.02, 95% CI 1.79 to 5.11, nine studies, 2051 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.8); NNH for moderate dose of 14.

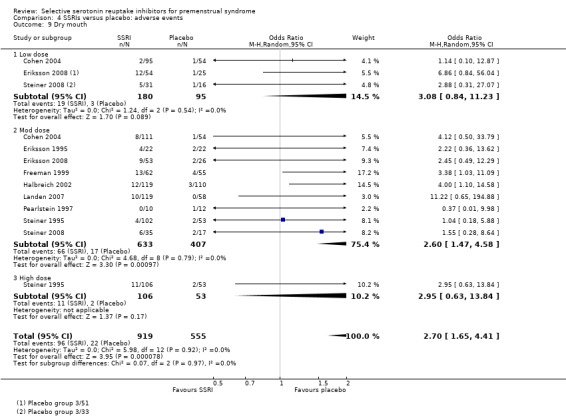

Dry mouth (OR 2.70, 95% CI 1.656 to 4.41, nine studies, 1474 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.9); NNH for moderate dose of 17.

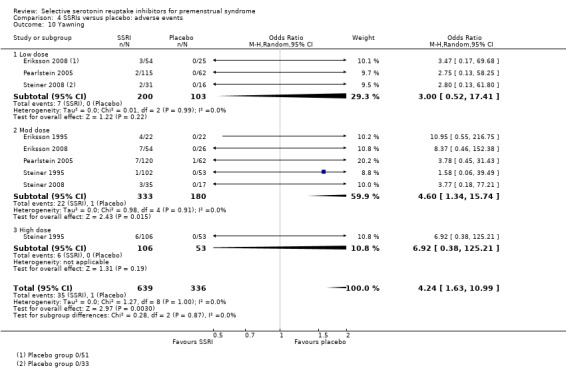

Yawning (OR 4.24, 95% CI 1.63 to 10.99, five studies, 975 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.10); NNH for moderate dose of 14.

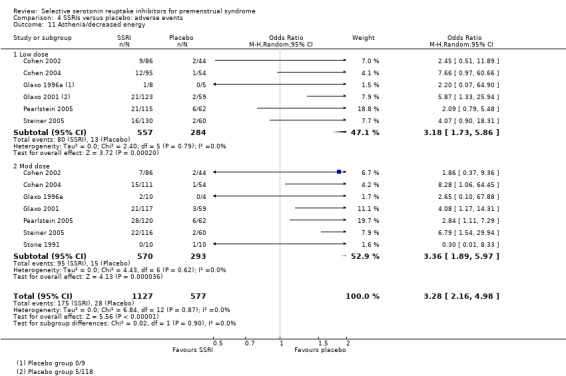

Asthenia or decreased energy (OR 3.28, 95% CI 2.16 to 4.98, seven studies, 1704 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.11); NNH for moderate dose of 9.

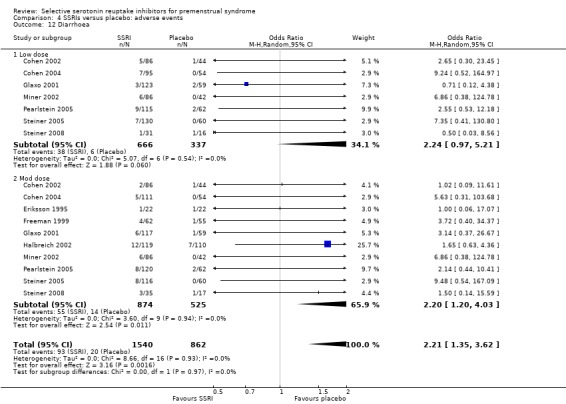

Diarrhoea (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.35 to 3.62, 10 studies, 2402 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.12); NNH for moderate dose of 25.

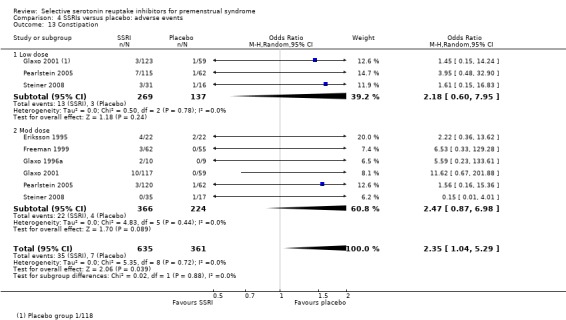

Constipation (OR 2.35, 95% CI 1.04 to 5.29, six studies, 996 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.13); NNH for moderate dose of 33.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 1 Nausea.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 2 Insomnia or sleep disturbance.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 3 Sexual dysfunction or decreased libido.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 4 Fatigue or sedation.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 5 Dizziness or vertigo.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 6 Tremor.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 7 Somnolence/decreased concentration.

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 8 Sweating.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 9 Dry mouth.

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 10 Yawning.

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 11 Asthenia/decreased energy.

4.12. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 12 Diarrhoea.

4.13. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 13 Constipation.

For most of these outcomes, inspection of the forest plots showed a clear dose‐response trend, with an increased risk of adverse events in women receiving a higher dose of SSRI.

Rates of the following events did not differ between the two groups.

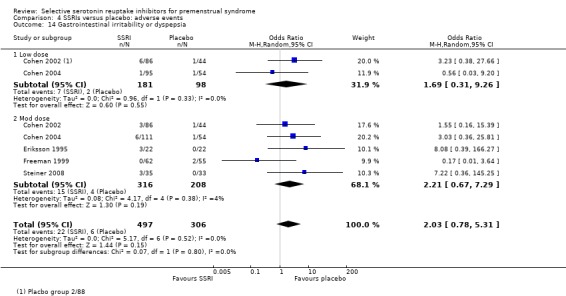

Gastrointestinal irritability or dyspepsia (OR 2.03, 95% CI 0.78 to 5.31, five studies, 803 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.14).

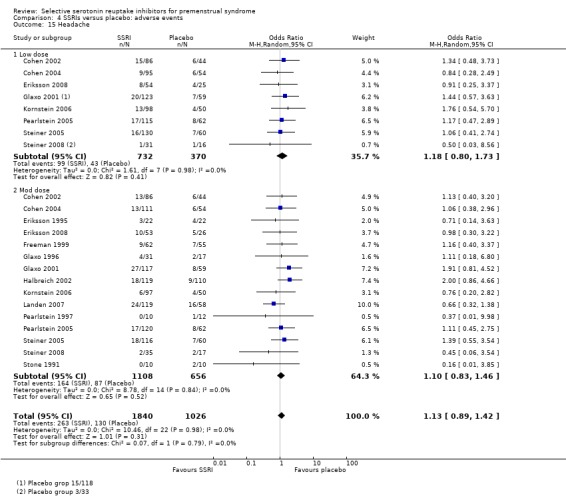

Headache (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.42, 15 studies, 2866 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.15).

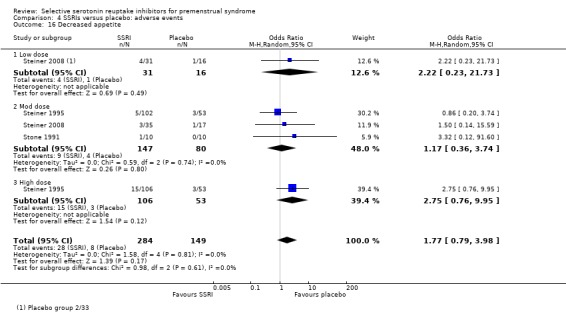

Decreased appetite (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.79 to 3.98, three studies, 433 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.16).

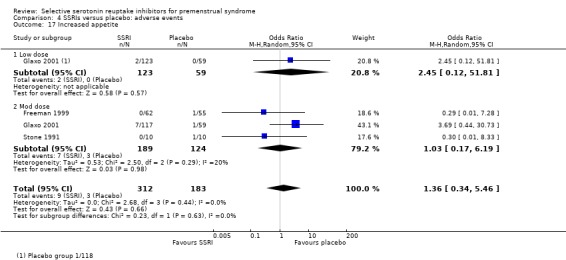

Increased appetite (OR 1.36, 95% CI 0.34 to 5.46, three studies, 495 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.17).

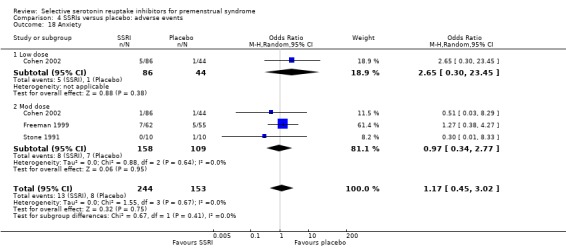

Anxiety (OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.45 to 302, three studies, 397 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.18).

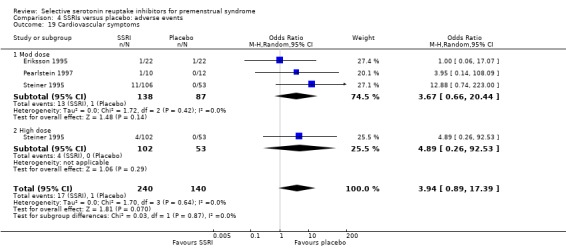

Cardiovascular symptoms (OR 3.94, 95% CI 0.89 to 17.39, three studies, 380 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.19).

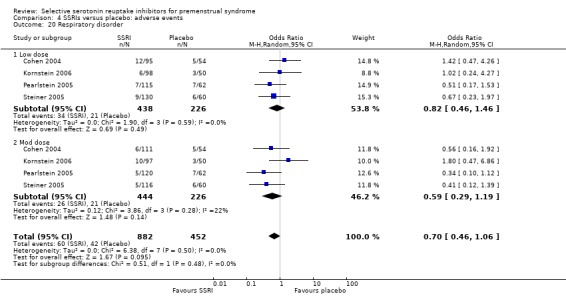

Respiratory disorder (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.06, four studies, 1334 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.20).

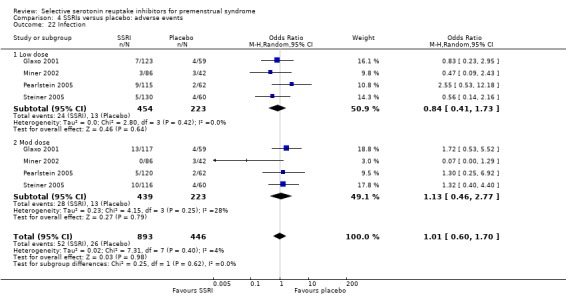

Sinusitis (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.12, five studies, 1657 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 4.21).

Infection (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.70, four studies, 1339 women; I2 = 4%; Analysis 4.22).

4.14. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 14 Gastrointestinal irritability or dyspepsia.

4.15. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 15 Headache.

4.16. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 16 Decreased appetite.

4.17. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 17 Increased appetite.

4.18. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 18 Anxiety.

4.19. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 19 Cardiovascular symptoms.

4.20. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 20 Respiratory disorder.

4.21. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 21 Sinusitis.

4.22. Analysis.

Comparison 4 SSRIs versus placebo: adverse events, Outcome 22 Infection.

Overall, heterogeneity was absent or minimal for analyses of adverse events (I2 = 0% to 4%).

Other side effects mentioned in one or more studies were breast tenderness (Stone 1991), numbness (Eriksson 1995), rash (Pearlstein 1997), trauma (Cohen 2004), vomiting (Pearlstein 2005), genital disorders (Pearlstein 2005), flu syndrome (Cohen 2004; Steiner 2008), back pain (Cohen 2002; Steiner 2008), pharyngitis and rhinitis (Cohen 2002), visual disturbance (Eriksson 1995; Steiner 1995), pain (Cohen 2002; Miner 2002), accidental injury (Cohen 2002) and abdominal pain (Glaxo 1996a). There was no significant difference between the groups for any of these outcomes, and the reported event rates were very low.

Secondary outcomes

3. Specific symptoms of PMS

3.1 Psychological symptoms

Eleven studies reported psychological symptom scores, either as end scores (five studies) or as change scores (four studies).

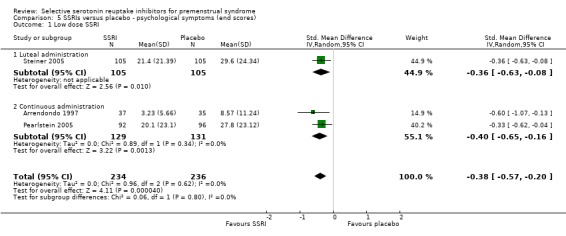

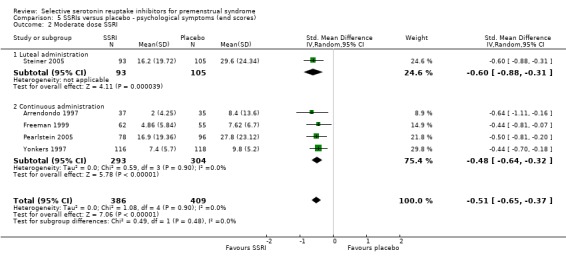

When psychological symptoms were assessed with end scores, SSRIs reduced symptoms significantly more effectively than placebo. Low dose SSRIs were associated with a small effect size (SMD ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐20.0 to ‐0.57, three studies, 470 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 5.1) and moderate dose SSRIs with a moderate effect size (SMD ‐0.51, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.65, five studies, 795 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 5.2 ). This applied to both luteal and continuous administration. Heterogeneity was absent.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ psychological symptoms (end scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ psychological symptoms (end scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.

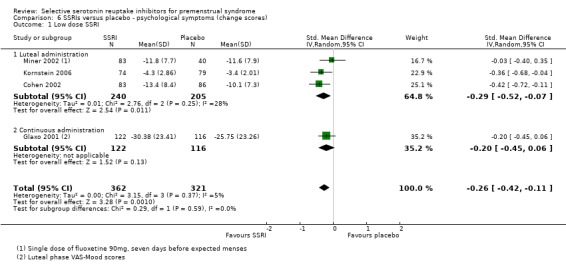

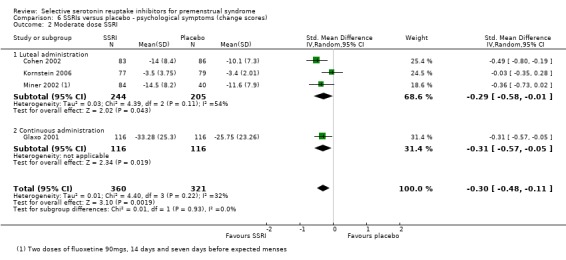

When psychological symptoms were assessed with change scores, SSRIs reduced symptoms significantly more effectively than placebo, with a small effect size. This applied to both low dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.11 to ‐0.42, four studies, 683 women; I2 = 5%; Analysis 6.1) and moderate dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.11 to ‐0.48, four studies, 681 women; I2 = 32%; Analysis 6.2). There were few studies in this analysis, and findings were not significant when studies of luteal administration were considered separately. Overall, statistical heterogeneity was low to moderate.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ psychological symptoms (change scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ psychological symptoms (change scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.

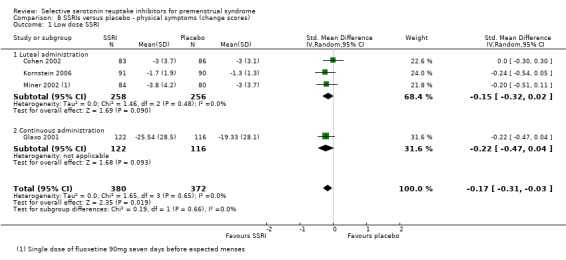

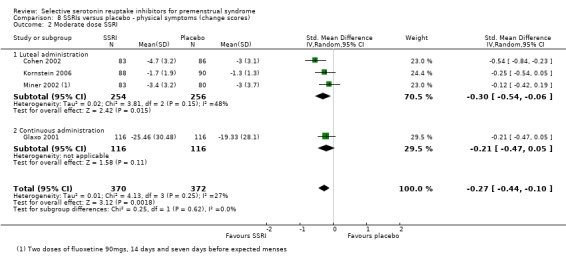

3.2 Physical symptoms

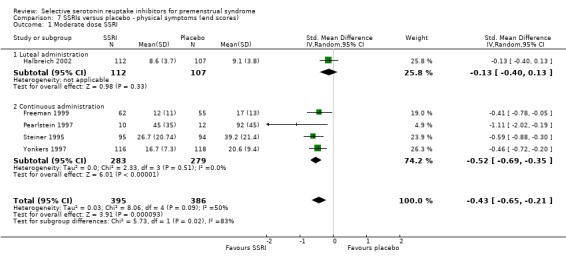

Nine studies reported physical symptom scores, either as end scores (five studies) or as change scores (four studies).

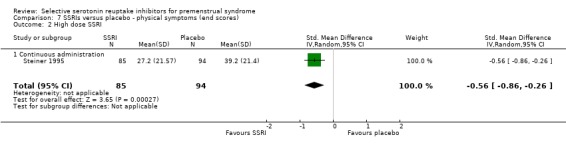

When physical symptoms were assessed with end scores, there were no data for low dose SSRIs. Moderate dose SSRIs reduced physical symptoms significantly more than placebo, with a small effect size and moderate heterogeneity (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.21 to ‐0.65, five studies, 781 women; I2 = 50%; Analysis 7.1). The heterogeneity was attributable to differences in type of administration. In the single study of luteal administration there was no significant difference between moderate dose SSRIs and placebo for this outcome (OR ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.13, one study, 219 women), while in the studies of continuous administration there was a significant benefit for the SSRI group, of moderate effect size (OR ‐0.52, 95% CI ‐0.69 to ‐0.3, four studies, 562 women; I2 = 0%). High dose SSRIs were associated with a moderate effect size (SMD ‐0.56, 95% CI ‐0.26 to ‐0.86, one study, 179 women; Analysis 7.2).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ physical symptoms (end scores), Outcome 1 Moderate dose SSRI.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ physical symptoms (end scores), Outcome 2 High dose SSRI.

When physical symptoms were assessed with change scores, SSRIs reduced symptoms significantly more effectively than placebo, with a small effect size. This applied to both low dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.03 to ‐0.31, four studies, 752 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 8.1) and moderate dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.27, 95% CI ‐0.10 to ‐0.44, four studies, 742 women; I2 = 27%; Analysis 8.2). When the results were reported by type of administration, findings were no longer statistically significant except for moderate dose luteal administration. Overall, heterogeneity was absent or low.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ physical symptoms (change scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ physical symptoms (change scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.

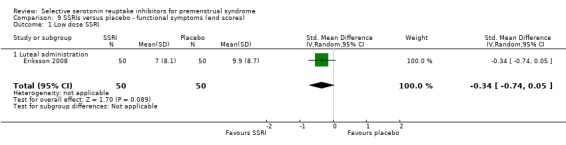

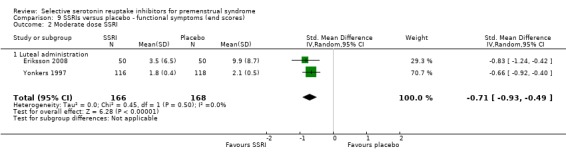

3.3 Functional symptoms

Five studies reported functional symptom scores, reported either as end scores (two studies) or as change scores (three studies).

When functional symptoms were assessed with end scores, no significant difference was found between SSRIs and placebo for low dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI 0.05 to ‐0.74, one study, 100 women; Analysis 9.1). Moderate dose SSRIs were associated with significantly reduced functional symptoms, with a moderate effect size (SMD ‐0.71, 95% CI ‐0.49 to ‐0.93, two studies, 334 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 9.2).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ functional symptoms (end scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ functional symptoms (end scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.

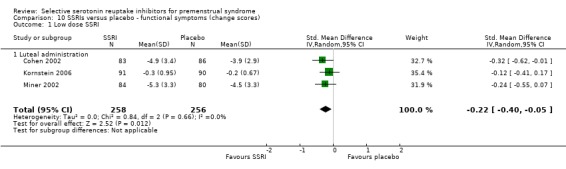

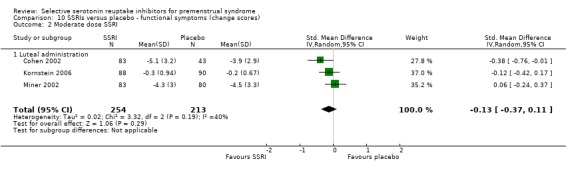

When functional symptoms were assessed with change scores, low dose SSRIs were of significant benefit compared to placebo, with a small effect size (SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.05 to ‐0.40, three studies, 514 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 10.1). There was no significant difference between moderate dose SSRIs and placebo for this outcome (SMD ‐0.13, 95% CI 0.11 to ‐0.37, three studies, 467 women; I2 = 40%; Analysis 10.2). Heterogeneity was absent for the analysis of low dose SSRIs, and moderate for the analysis of moderate dose SSRIs.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ functional symptoms (change scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ functional symptoms (change scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.

3.4 Irritability

Eight studies reported irritability scores, reported either as end scores (seven studies) or as change scores (one study).

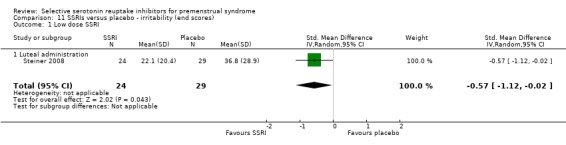

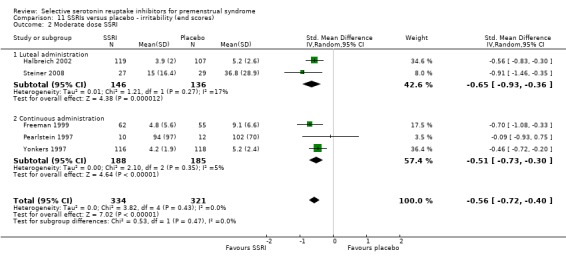

When irritability was assessed with end scores, SSRIs reduced symptoms significantly more than placebo, with a moderate effect size. This applied to both low dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.57, 95% CI ‐0.02 to ‐0.57, one study, 53 women; Analysis 11.1) and moderate dose SSRIs (SMD ‐0.56, 95% CI ‐0.40 to ‐0.72, five studies, 655 women; I2 = 0%; Analysis 11.2). Heterogeneity was absent.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ irritability (end scores), Outcome 1 Low dose SSRI.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 SSRIs versus placebo ‐ irritability (end scores), Outcome 2 Moderate dose SSRI.