Abstract

Background

Early infant diagnosis of HIV and antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been rapidly scaled-up. We aimed to examine the effect of expanded access to early ART on the characteristics and outcomes of infants initiating ART.

Methods

From 9 cohorts within the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS-Southern Africa collaboration, we included infants with HIV initiating ART ≤3 months of age between 2006 and 2017. We described ART initiation characteristics and the probability of mortality, loss to follow-up (LTFU) and transfer out after 6 months on ART and assessed factors associated with mortality and LTFU.

Results

A total of 1847 infants started ART at a median age of 60 days [interquartile range: 29–77] and CD4 percentage (%) of 27% (18%–38%). Across ART initiation calendar periods 2006–2009 to 2013–2017, ART initiation age decreased from 68 (53–81) to 45 days (7–71) (P < 0.001), median CD4% improved from 22% (15%–34%) to 32% (22–43) (P < 0.001) and the proportion with World Health Organization clinical disease stage 3 or 4 declined from 81.6% to 32.7% (P < 0.001). Overall, the 6-month mortality probability was 5.0% and LTFU was 20.4%. Mortality was 10.6% (95% confidence interval: 7.8%–14.4%) in 2006–2009 and 4.6% (3.1%–6.7%) in 2013–2017 (P < 0.001), with similar LTFU across calendar periods (P = 0.274). Pretreatment weight-for-age Z score <−2 was associated with higher mortality.

Conclusions

Infants with HIV are starting ART younger and healthier with associated declines in mortality. However, the risk of mortality remained undesirably high in recent years. Focused interventions are needed to optimize the benefits of earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: infants, early infant antiretroviral therapy, mortality, pediatric HIV, South Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 140,000 new HIV infections and 73,000 AIDS-related deaths occurred in 2018 among children 0–9 years of age.1 Compared with older children, infants with HIV (HIV+) are prone to high early mortality and without antiretroviral therapy (ART), 50% will die before their second birthday.2 Complexities related to testing, age and weight-related drug changes, rifampicin cotreatment of tuberculosis and limited drug formulations make infants a highly vulnerable population.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines for pediatric ART initiation have shifted from clinical and CD4-based criteria to immediate ART for all (Universal ART). In 2008, universal ART was recommended for all HIV+ infants <12 months of age based on findings from the Children with HIV Early antiRetroviral (CHER) trial.3,4 In 2010, South Africa adopted universal ART for children <2 years of age. Furthermore, guidelines for lifelong universal ART for all pregnant and breast-feeding women living with HIV (so-called “Option B+”)5 and universal testing for HIV-exposed infants at birth were implemented in 2013 and 2015, respectively.6 Consequently, by 2017, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) service uptake was >95%, the national coverage of early infant diagnosis (EID) and birth HIV testing uptake were both >90% and pediatric ART coverage was >75%.1,7

With expanded ART access, the demographic and clinical characteristics of recently infected infants may differ from those infected before the introduction of Option B+ and early testing. For example, prematurity, low birth weight, immunosuppression and comorbidities may be more prevalent in those becoming HIV-infected despite widespread coverage of Option B+. Of note, infants with these “high risk” characteristics were excluded from the CHER trial; therefore, the survival benefit may not be generalizable to current programmatic settings, especially in resource-limited settings where infants still present for treatment with advanced HIV disease.8–10 While the outcomes of infants infected before the availability of EID and early ART have been described,10–13 there are limited data on infants initiating early ART before 3 months of age outside research-controlled settings, in the context of improved EID practices and widespread access to ART. Using observational data, we examined temporal trends in the characteristics and outcomes of HIV+ infants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Setting and Participants

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from 9 International epidemiology Databases to Evaulate AIDS-Southern Africa (IeDEA-SA) cohorts in South Africa. IeDEA is a global research consortium which collects routine anonymized data on patients receiving HIV care and treatment.14 Eight of the 9 sites included are mostly in urban areas representing primary, secondary and tertiary levels, while 1 site represents a private health sector facility. All sites contributing data to this study have relevant institutional and ethical approval.

We included ART-naïve infants (except for exposure to PMTCT drugs), initiating ART ≤3 months of age from January 2006 (first WHO treatment guidelines for children) to November 2017. To better understand the effect of changing WHO eligibility criteria for ART initiation and expansion of PMTCT programs between 2006 and 2017, infants were grouped according to the calendar year of ART initiation: 2006–2009, 2010–2012 and 2013– 2017 representing the implementation of WHO ART eligibility for all HIV-infected children <2 years in 2010 and Option B+ in 2013, respectively. The entry point for this study was the earliest date of ART initiation at the IeDEA-SA clinical site. We defined ART as a combination of ≥3 antiretroviral drugs from ≥2 different drug classes. The recommended first-line regimen for children <3 years of age before 2010 was stavudine, lamivudine and lopinavir/ ritonavir. From 2010, national treatment guidelines recommended that abacavir replace stavudine in the first-line regimen. Guidelines also recommend that newborns receive zidovudine, lamivudine and nevirapine for the first month or until >3 kg.

Outcomes and Key Variable Definitions

Our primary analysis described ART initiation characteristics and outcomes of mortality, loss to follow-up (LTFU) and transfer out (TFO) to other facilities by 6 months on ART, compared across calendar periods. We also described weight-for-age Z score (WAZ) improvement in those retained for 6 months after ART initiation. Mortality included all-cause mortality and LTFU was defined as not having any documented clinic visit or laboratory result within a window period of 4–9 months after ART initiation, irrespective of whether the child returned to care >9 months after ART initiation. We further distinguished infants with no visits after the date of ART initiation for up to 9 months as having “no follow-up” while those with ≥1 subsequent visit within the first 3 months on ART but with no visit between 4 and 9 months after ART initiation were classified as “LTFU but with subsequent follow-up on ART.”15 WAZ improvement by 6 months on ART was assessed using the measure closest to 6 months (window 4–9 months). Analysis of outcomes was limited to infants starting ART ≥6 months before database closure. Follow-up was right-censored at the earliest of death, last clinic visit (for patients LTFU), date of TFO or 6 months after ART start.

WAZ was calculated using the WHO Child Growth Reference Standards.16 We defined underweight as WAZ ≤−2 and severely underweight as WAZ ≤−3. Immunosuppression was classified using CD4% as severe (<15), moderate (15%–24%) or absent (>25%).17 When describing weight measurements and laboratory values at ART initiation, we selected the measurement closest to ART start date within a window of −3 weeks to +1 month for WAZ and −6 months to +2 weeks after ART start for viral load, CD4 counts and percentages.

Statistical Analysis

We compared ART initiation characteristics across calendar periods using the χ2 or Fisher exact test (in the case of sparse data) and Kruskal-Wallis test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. We used Kaplan-Meier methods to estimate the probability of mortality, LTFU and TFO and compared survival using the log-rank test. Due to the interdependence of mortality, LTFU and TFO, we also conducted competing risks analysis to calculate the cumulative incidence functions for these outcomes.

We used Cox regression to determine ART initiation characteristics associated with mortality and LTFU. Patient-level covariates included in the models were selected a priori as potential confounders based on their clinical relevance and data availability and included age, sex, clinical stage, WAZ <−2, log10 viral load, CD4 percentage or immunosuppression level, WHO disease stage, PMTCT exposure, year of ART initiation (2006–2009, 2010–2012 and >2013). Adjusted Cox regression models were stratified by clinical site to account for heterogeneity.

We addressed missing baseline data for WAZ, viral load, WHO disease stage and CD4 cell counts and percentages using multiple imputation methods. The imputation model relied on the assumption of data missing at random and included all ART initiation characteristics, cohort, year of ART initiation and outcome variables. We generated 10 imputed dataset and combined estimates using Rubin Rules.18 We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess predictors of mortality including only patients with complete case data. All statistical analyses were completed using STATA 15.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

ART Initiation Characteristics

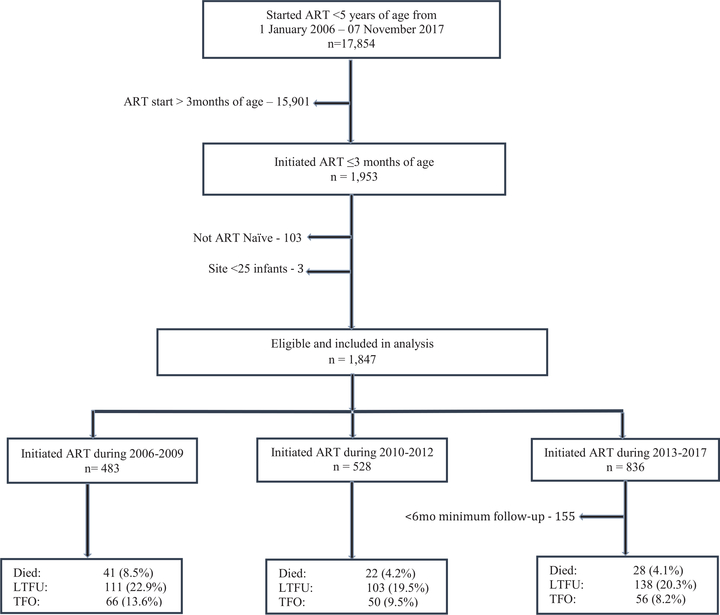

Between 2006 and 2017, 17,854 HIV+ children <5 years old initiated ART in the IeDEA-SA sites in South Africa (Fig. 1). Among these, the proportion starting ART ≤3 months of age increased from 6.3% to 20.5% in 2006–2009 and 2013–2017, respectively (P < 0.001). The median age was 60 days [interquartile range (IQR): 29–77] and differed substantially by calendar period, ranging from 68 days in 2006–2009 to 45 days in 2013–2017 (P < 0.001). There was a marked increase in the proportion of infants starting treatment within 1 month of age; 7% in 2006–2009, 14% in 2010–2012 and 44% in 2013–2017. The median CD4% was 27%, improving from 22% in 2006–2009 to 32% in 2013–2017 (P < 0.001). There was a pattern toward an increase in the proportion of females and median log viral load over time. Half of all infants were classified with WHO disease stage 3 or 4, however, this proportion decreased substantially over time; 81.6% in 2006–2009 vs. 32.7% in 2013–2017, P < 0.001 (Table 1). Compared with infants starting ART in the first month of age (0–30 days), those starting between 31 and 60 days and 61 and 90 days of age were more likely to be underweight (WAZ <−2) (38.5% vs. 60.6% and 60.1%; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart describing participant selection and outcomes of infants with HIV initiating ART ≤3 months of age from 2006 to 2017 in South Africa.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Infants Who Initiated Antiretroviral Therapy at ≤3 mo of Age Across South Africa

| Characteristics | Overall N = 1847 | 2006–2009 N = 483 | 2010–2012 N = 528 | 2013–2017 N = 836 | *P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at ART start (d) | 60 (29–77) | 68 (53–81) | 67 (46–80) | 45 (7–71) | <0.001 |

| Age category (d) | |||||

| 0–30 | 479 (25.9) | 34 (7.0) | 77 (14.5) | 368 (44.0) | <0.001 |

| 31–60 | 464 (25.1) | 155 (32.1) | 141 (26.7) | 168 (20.1) | |

| 60–90 | 905 (48.9) | 294 (60.8) | 310 (58.7) | 300 (35.8) | |

| Female | 1028 (55.6) | 250 (51.8) | 317 (60.0) | 461 (55.1) | <0.031 |

| CD4 count (cells/pL) | 1073 (407–1955) | 899(396–1718) | 1274 (487–2028) | 1149 (350–2070) | <0.035 |

| CD4 percentage | 27 (18–38) | 22 (15–33) | 26.2 (18–36) | 32 (22–43) | <0.001 |

| CD4% for age <30 days | 42 (27–51) | 21 (16–28) | 38.6 (24–51) | 44.3 (31–52) | 0.005 |

| CD4% for 31–60 days | 27 (19–39) | 26 (18–38) | 26 (16–40) | 32 (23–40) | 0.053 |

| CD4% for 61–90 days | 24 (16–33) | 21 (14–31) | 24 (18–33) | 26 (16–33) | <0.001 |

| Missing, N (%) | 817 (44) | 156 (32) | 188 (35) | 473 (56) | |

| Immunosuppression | |||||

| >25% (none) | 556 (54) | 143 (43) | 177 (51.9) | 246 (67.6) | <0.001 |

| >15 to ≤25% (moderate) | 284 (27) | 104 (31) | 110 (32.3) | 70 (19.2) | |

| ≤15% (severe) | 182 (17) | 80 (24) | 54 (15.8) | 48 (13.2) | |

| Missing, N (%) | 817 (44) | 156 (32) | 188 (35.6) | 473 (56.5) | |

| Log10 viral load | 5.8 (4–6) | 5.0 (5–6) | 6.0 (5.0–6.6) | 5.3 (3.8–6.3) | <0.001 |

| Viral load (copies/mL) | |||||

| <100,000 | 253 (27.4) | 47 (15.4) | 63 (22.8) | 143 (41.7) | <0.001 |

| >100,000–1 million | 282 (30.5) | 125 (40.9) | 72 (26.1) | 85 (24.7) | |

| >1 million | 389 (42.1) | 133 (43.6) | 141 (51.1) | 115 (33.5) | |

| Missing, N (%) | 923 (44.9) | 178 (36.8) | 252 (47.7) | 493 (58.9) | |

| WHO clinical stage | |||||

| I/II | 592 (47.6) | 65 (18.4) | 152 (45.7) | 375 (67.3) | <0.001 |

| III/IV | 652 (52.5) | 289 (81.6) | 181 (54.6) | 182 (32.7) | |

| Missing, N (%) | 604 (32.7) | 129 (26.7) | 196 (37.1) | 279 (33.3) | |

| WAZ | −2.4 (−3.7 to −1.1) | −2.9 (−4.2 to −1.7) | −2.3 (−3.6 to −1.0) | −1.7 (−3.2 to −0.5) | <0.001 |

| WAZ category | |||||

| <−3 | 316 (34.8) | 146 (43.7) | 94 (32.6) | 76 (26.6) | <0.001 |

| −3 to −2 | 175 (19.3) | 70 (21.1) | 62 (21.5) | 43 (15.0) | |

| >−2 | 418 (45.9) | 118 (35.3) | 132 (45.8) | 167 (58.3) | |

| Missing, N (%) | 940 (50.9) | 149 (30.8) | 241 (45.6) | 550 (65.7) | |

| †PMTCT exposure | |||||

| No | 952 (51.5) | 197 (40.8) | 250 (47.3) | 505 (60.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 233 (12.6) | 43 (8.9) | 38 (7.2) | 152 (18.2) | |

| Unknown | 662 (35.8) | 243 (50.3) | 240 (45.5) | 179 (21.4) | |

P values were derived from χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests, where appropriate. Values are given as number (%) or median (interquartile range).

Maternal or infant PMTCT exposure.

Programmatic Outcomes

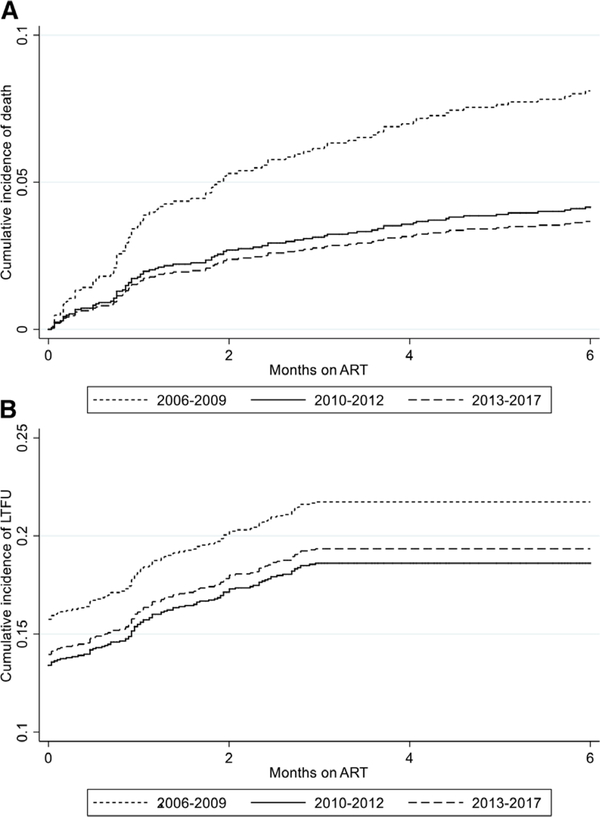

Among 1692 infants, 86 (5.0%) died, 353 (20.8%) became LTFU and 144 (10.2%) were TFO. The 6-month cumulative probabilities of mortality [95% confidence interval (CI)], LTFU and TFO were 6.4% (5.2–7.9), 21.5% (19.4–23.3) and 10.6% (9.0–12.3), respectively. Mortality probability was highest among infants initiating ART in 2006–2009 [10.6% (7.8–14.3)] compared with 2013–2017 [4.6% (3.1–6.7)] (log-rank test P < 0.001). LTFU remained similar across calendar period, ranging from 23.8% (20.2–28.0) in 2006–2009 to 21.0% (18.1–24.3) in 2013–2017 (log-rank test P = 0.2746). Competing risk analysis yielded similar estimates as shown in Figure 2 and Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/INF/D695.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative incidence functions stratified by calendar period of ART initiation for: (A) mortality accounting for LTFU and TFO as competing events, (B) LTFU accounting for death and TFO as competing events. Plot shows time to LTFU defined as no visit from 4 to 9 months on treatment.

The median follow-up time for infants who died was 33 (21–88), for LTFU was 0 (0–18) days and for TFO was 45 days (12–94) days. For the 2006–2009 period, death occurred at a median of 27 days (15–57) versus 45 days (21–85) in the latest period. The median age at death was 94 days (IQR: 79–134), with no significant difference across ART initiation time periods (P = 0.4655). In addition, 61.5% of infants who died initiated treatment between 61 and 91 days of age. Among those LTFU, 74% did not return for a clinic visit after the date of ART initiation for up to 9 months, while 26% returned for a subsequent visit after initiating ART (within 3 months on ART) and thereafter were LTFU from 3 to 9 months after ART initiation.

Risk Factors for Mortality and LTFU

Relative to ART start between 2006 and 2009, the unadjusted mortality hazard ratio (uHR) was lower for infants starting ART in 2010–2012 and 2013–2017 (Table 2); however, this effect was attenuated after adjusting for disease severity at ART start. Compared with having WAZ >−2, infants with WAZ ≤−2 had a 1.7-fold [adjusted HR (aHR), 1.74; 95% CI: 1.07–2.81] increased risk of death (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model of Imputed Dataset Stratified by Cohort: Infant Characteristics Associated With Mortality and Loss to Follow-up in the First 6 months on ART (n = 1692)

| Mortality | Loss to Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |

| Age in weeks | 1.47 (0.89–2.45) | 0.95 (0.53–1.71) | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | 0.89 (0.68–1.15) |

| Female ART initiation year |

0.68 (0.44–1.02) | 0.70 (0.46–1.07) | 0.89 (0.72–1.09) | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) |

| 2006–2009 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2010–2012 | 0.47 (0.27–0.79) | 0.76 (0.42–1.36) | 0.77 (0.59–1.01) | 0.54 (0.40–0.73) |

| 2013–2017 | 0.46 (0.28–0.75) | 0.98 (0.54–1.75) | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) | 0.46 (0.33–0.62) |

| WHO disease stage | ||||

| I/II | Ref | Ref | ||

| III/IV | 1.85 (1.14–2.99) | 1.08 (0.61–1.91) | 0.87 (0.65–1.14) | 0.91 (0.65–1.28) |

| CD4 percentage WAZ |

0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

| >−2 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≤−2 | 2.43 (1.53–3.84) | 1.74 (1.07–2.81) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 0.95 (0.71–1.26) |

| Log viral load *PMTCT exposure |

1.38 (1.07–1.58) | 1.14 (0.89–1.46) | 0.97 (0.88–1.08) | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.17 (0.74–1.85) | 0.87 (0.50–1.49) | 0.59 (0.46–0.77) | 1.05 (0.61–1.69) |

| Unknown | 1.10 (0.62–1.97) | 1.20 (0.50–2.86) | 0.83 (0.62–1.11) | 1.08 (0.65–1.78) |

Status of infant exposure to maternal or infant PMTCT.

We observed a decreasing risk of LTFU (ie, no follow-up and LTFU but with subsequent follow-up on ART) over time. Initiating ART between 2010–2012 and after 2013 were associated with a decreased unadjusted hazard of LTFU (aHR 0.54, 95% CI: 0.40–0.73 and aHR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.33–0.62, respectively), compared with 2006–2009. Infants with unknown maternal or infant PMTCT status at ART initiation had a 2.4-fold increased risk of being LTFU immediately after the date of ART initiation (no follow-up) (aHR: 2.43, 95% CI: 1.32–4.59). None of the infant ART initiation characteristics included was associated with LTFU after at least 1 subsequent visit after ART initiation (Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/INF/D695). Overall, we obtained similar estimates when complete case analysis was conducted, except for no decrease in risk of LTFU in the most recent calendar period (Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/INF/D695).

Weight Improvement

At ART initiation, the median WAZ (IQR) at initiation was –2.4 (–3.7 to –1.1), varying significantly across calendar periods (P < 0.001), 56% of all infants had WAZ ≤–2 (underweight = 19.3% plus severely underweight = 34.8%). After 6 months on ART, the median WAZ was –1.19 (–2.3 to –0.3) which did not differ by calendar period of ART initiation (P = 0.949); 30% of infants had WAZ ≤−2.

DISCUSSION

In this study of infants with HIV starting ART ≤3 months of age, we found that an increasing proportion of infants started ART at younger ages and with less advanced HIV disease. Overall, mortality was 5.0% with marked differences between the calendar periods. Although mortality was halved from 2010 onward, mortality remained at 4.1% after 2013. An unchanging proportion of 1 in 5 infants were LTFU after 6 months of ART, with nearly 3 quarters of those having no follow-up after their ART initiation visit. Declining mortality is possibly mediated by earlier ART initiation reflecting the real-world benefit of the shift to universal ART for infants and simultaneous expansion of EID access, particularly birth testing in South Africa.

Characteristics of infants starting ART improved across calendar periods. A marked increase in the proportion of infants ≤1 month of age at initiation was a major driver of decreasing age at ART start. We attribute this finding to improved EID services and the resulting high coverage of >90% in South Africa after the introduction of universal birth testing in 2015. However, considering the recent context of expanded EID and treatment programs, infants infected after 2013 still started ART relatively late at a median age of 45 days. Similar to previous findings, we found that infant immune status at ART start improved over time.10,12

Infants acquiring HIV despite the availability of PMTCT are more likely to be those missed by PMTCT programs, who present for testing when they become sick rather than through routine infant follow-up.19 For example, infants initiating ART between 61 and 90 days old were more likely to be underweight than those initiating before 30 days old (57% vs. 38%) and underweight infants were more likely to die.10,20 This suggests that older infants are those who missed earlier testing or were infected during the early postpartum period and only present to care with advanced disease and hence higher risk of mortality. This partially explains the ongoing burden of advanced disease despite high birth testing coverage among those known to the PMTCT program. The national expansion of PMTCT (>95%) was reflected in our study as the proportion of infected infants with PMTCT exposure doubled in the latest cohort. Compared with the era of limited access to PMTCT, recent periand postnatal transmissions may be occurring among an emerging vulnerable population of mothers. These women may have either not engaged with the health system or were not virally suppressed despite accessing care due to complex social and medical challenges that influence health-seeking behavior and ART adherence.

Previous ART implementation studies in infants before the expansion of early diagnosis and ART for prevention and treatment suggests a trend toward decreasing longer-term mortality over time.10,21,22 Our findings extend existing evidence to include trends in short-term mortality in early-treated HIV+ infants. The effect of lower mortality over time was not retained after adjusting for disease severity, suggesting that mortality reduction was mediated by earlier ART initiation and improved infant characteristics. The probability of survival for period 2013–2017 was 93%, lower than the estimated 6-month survival probability of 97% for the general population of South African infants.23 The true mortality difference between children with and without HIV is likely even greater due to the inherent survival bias due to infant follow-up from ART start in our cohort. An estimated 12-month mortality of 14% has been reported in a recent cohort of birth-identified HIV+ infants, suggesting significant mortality despite ART in this cohort.24

The CHER trial enrolled infants starting ART <12 weeks of age (excluding infants with a birth weight <2 kg, advanced HIV and CD4 depletion) and followed up for a median of 40 weeks comparing early and deferred ART.4 Mortality in our population during the 2013–2017 period was 4.6%, compared with 4.0% reported in the CHER trial arm for immediate ART. Although higher mortality rates would be expected in our population, a shorter follow-up period and high LTFU may have masked true mortality. While it is concerning that mortality did not decline further during the latest period (compared with 2010–2012) when both Option B+ and birth EID were implemented, characteristics such as prematurity and associated complications, and infectious comorbidities may have contributed to poorer outcomes. Furthermore, because we only measured mortality after ART start, it is possible that infants who previously would have died before being diagnosed and/or starting ART are now initiating ART earlier, and that pre-ART mortality has shifted to mortality after early ART initiation. These explanations are supported by another study which reported that 15% more HIV+ infants were lost from the ART program by 1 year among those who started after 2012 relative to those starting before 2010.25

More than half of deaths occurred in the first 3 months of ART initiation and mostly in the 2006–2009 cohort, similar to earlier studies.26 While high rates of bacteremia and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome have been associated with high early mortality, earlier ART start with higher CD4 percentages has likely resulted in immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome becoming less common.27

The high proportion of infants with no follow-up is particularly concerning. Increased mobility and poor HIV service retention soon after delivery among women living with HIV are well documented and contribute to low retention of infants soon after initiating treatment.28 While poor documentation of transfer between health care facilities may underestimate retention, high early LTFU may contribute to mortality under-ascertainment. In this respect, although overall LTFU did not decrease over time, the risk of LTFU after adjustment for disease severity reduced in recent years suggesting that true LTFU may be reduced. Improved focus on retention and shift toward individualized care may be more feasible in the context of a decreased overall burden of pediatric HIV. As with mortality, it is possible that that pre-ART LTFU has been shifted to LTFU on ART after the implementation of birth diagnosis and universal ART.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of early infant ART outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. This study includes data from routine care cohorts representing different levels of health care in South Africa. In addition, the study period covers several guideline periods, allowing assessment of the influence of guideline changes while reflecting the realities of routine, resource-limited settings.

The routine nature of the settings from which data were collected is evident from the amount of missing data. Lack of data on PMTCT, maternal socioeconomic factors and comorbidities such as tuberculosis may have led to residual confounding. We found an increased risk of death among underweight infants but could not assess the extent to which prematurity and low birthweight are responsible because of limited data on gestational age and weight at birth. There is a chance of survival bias in our selected cohort may have led to an under-estimation of mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

There have been improvements in the characteristics of infants starting ART and an associated decline in mortality over time. Nevertheless, early death and LTFU remain unacceptably high. Considering the risk of mortality did not decrease further after 2010, there is a need to better understand the specific healthcare needs of this population of infants who continue to acquire HIV despite widespread PMTCT and ART access and uptake.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the children who contributed data to this study, the hospital teams of the sites, site investigators from all participating sites in the IeDEA Southern Africa pediatric cohorts in South Africa. We also thank Drs. Leigh Johnson and Morna Cornell for their contribution to this manuscript.

IeDEA Southern Africa site investigators and cohorts (only sites denoted with an asterisk contributed data to this analysis): *Gary Maartens: Aid for AIDS, South Africa; Carolyn Bolton, Michael Vinikoor: Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ), Zambia; *Robin Wood: Gugulethu ART Programme, South Africa; *Nosisa Sipambo: Harriet Shezi Clinic, South Africa; *Frank Tanser: Africa Health Research Institute (Hlabisa), South Africa; *Andrew Boulle: Khayelitsha ART Programme, South Africa; *Geoffrey Fatti: Kheth’Impilo, South Africa; Sam Phiri: Lighthouse Clinic, Malawi; Cleophas Chimbetete: Newlands Clinic, Zimbabwe; *Karl Technau: Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital, South Africa; *Brian Eley: Red Cross Children’s Hospital, South Africa; Josephine Muhairwe: SolidarMed Lesotho; Juan Burgos-Soto: SolidarMed Mozambique; Cordelia Kunzekwenyika: SolidarMed Zimbabwe; Matthew P. Fox: Themba Lethu Clinic, South Africa; *Hans Prozesky: Tygerberg Academic Hospital, South Africa.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01AI069924. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.pidj.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global AIDS Monitoring and UNAIDS 2019 estimates. 2019.

- 2.Newell ML, Coovadia H, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:1236–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Report of the WHO Technical Reference Group, Paediatric HIV/ART Care Guideline Group Meeting. WHO Headquarters; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. ; CHER Study Team. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2233–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. The South African Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. National Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the Management of HIV in Children, Adolescents and Adults. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyo F, Haeri Mazanderani A, Barron P, et al. Introduction of routine HIV birth testing in the South African national consolidated guidelines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37:559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Innes S, Lazarus E, Otwombe K, et al. Early severe HIV disease precedes early antiretroviral therapy in infants: are we too late? J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melaku Z, Lulseged S, Wang C, et al. Outcomes among HIV-infected children initiating HIV care and antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:474–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter M, Davies MA, Mapani MK, et al. Outcomes of infants starting antiretroviral therapy in Southern Africa, 2004–2012. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adedimeji A, Edmonds A, Hoover D, et al. Characteristics of HIV-infected children at enrollment into care and at antiretroviral therapy initiation in Central Africa. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies MA, Phiri S, Wood R, et al. ; IeDEA Southern Africa Steering Group. Temporal trends in the characteristics of children at antiretroviral therapy initiation in southern Africa: the IeDEA-SA collaboration. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenner L, Brinkhof MW, Keiser O, et al. ; International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS in Southern Africa. Early mortality and loss to follow-up in HIV-infected children starting antiretroviral therapy in Southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:524–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egger M, Ekouevi DK, Williams C, et al. Cohort profile: the international epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1256–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tenthani L, Haas AD, Tweya H, et al. Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (‘Option B+’) in Malawi. AIDS. 2014;28:589–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organizations. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height for Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age, Methods and Development. WHO Press, World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO Case Definitions of HIV for Surveillance and Revised Clinical Staging and Immunological Classification of HIVRelated Disease in Adults and Children. WHO Press, World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donald R Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons C, ed. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, Chichester; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penazzato M, Revill P, Prendergast AJ, et al. Early infant diagnosis of HIV infection in low-income and middle-income countries: does one size fit all? Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrams EJ, Woldesenbet S, Soares Silva J, et al. Despite access to antiretrovirals for prevention and treatment, high rates of mortality persist among HIV-infected infants and young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36: 595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben-Farhat J, Schramm B, Nicolay N, et al. Mortality and clinical outcomes in children treated with antiretroviral therapy in four African vertical programmes during the first decade of paediatric HIV care, 2001–2010. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies MA, Egger M, Keiser O, et al. Paediatric antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of published clinical studies. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009;8:329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistics South Africa. Statistical release. 2015.

- 24.Technau KG, Strehlau R, Patel F, et al. 12-month outcomes of HIV-infected infants identified at birth at one maternity site in Johannesburg, South Africa: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e706–e714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lilian RR, Mutasa B, Railton J, et al. A 10-year cohort analysis of routine paediatric ART data in a rural South African setting. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourne DE, Thompson M, Brody LL, et al. Emergence of a peak in early infant mortality due to HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabie H, Violari A, Duong T, et al. ; CHER Team. Early antiretroviral treatment reduces risk of bacille Calmette-Guérin immune reconstitution adenitis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1194–200, i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips TK, Clouse K, Zerbe A, et al. Linkage to care, mobility and retention of HIV-positive postpartum women in antiretroviral therapy services in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(Suppl 4):e25114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.