Abstract

Chemical profiling of the Streptomyces sp. strain SUD119, which was isolated from a marine sediment sample collected from a volcanic island in Korea, led to the discovery of three new metabolites: donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3). The structures of 1–3 were found to be rearranged, multicyclic, angucyclinone-class compounds according to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS) analyses. The configurations of their stereogenic centers were successfully assigned using a combination of quantum mechanics–based computational methods for calculating the NMR shielding tensor (DP4 and CP3) as well as electronic circular dichroism (ECD) along with a modified version of Mosher’s method. Donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) displayed cytotoxicity against diverse human cancer cell lines (IC50: 6.7–9.6 μM for 3).

Keywords: molecular modeling, electronic circular dichroism, quantum mechanics-based computation, angucyclinone, Streptomyces, cytotoxicity

1. Introduction

Quantum mechanics–based computation is emerging as a useful tool for elucidating the structure of natural products and complements the analysis of experimental spectroscopic data [1,2,3]. Modern computational techniques, when coupled with a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) shielding tensor, allow us to clarify the assignment of individual nuclei when considering experimental NMR data and establish relative configurations [3,4]. In particular, the recent development of advanced statistical analyses (for example, CP3 and DP4) has enabled us to assign the relative configurations of natural products possessing remote stereogenic centers that are located multiple bonds away from the other chiral centers with assigned configurations. These analyses utilize computed 1H and 13C NMR chemical shift values based solely on computational methods and statistically compare them with experimental NMR chemical shifts using web-based applets provided by the Smith and Goodman groups [3,5,6]. Despite the usefulness of the computational methods that utilize an NMR shielding tensor for the assignment of relative configurations, these techniques are not applicable to absolute configurations because NMR spectroscopy cannot inherently distinguish enantiomers. However, over the past few decades, electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra have been used to determine the absolute configurations of natural products [7,8]. Advanced ECD calculations, when coupled with time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT), have resulted in higher accuracy and lower computational costs and enable the assignment of absolute configurations of molecules through comparisons between experimental and calculated ECD spectra [8,9].

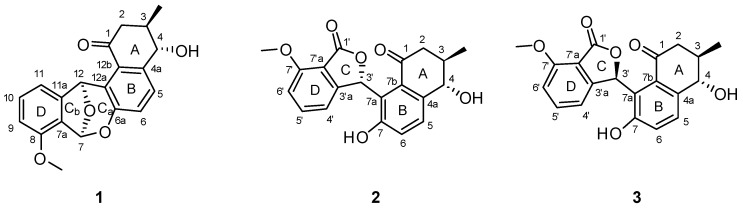

Besides the application of computational methods for elucidating the structures of natural products, chemical investigations into understudied natural resources are also crucial in natural product research that aims to discover structurally and biologically novel compounds [10]. In this regard, we have been examining the chemical profiles of actinobacterial strains that inhabit the marine environments of volcanic islands, which may provide unique microbial habitats with volcanic minerals and salts from the surrounding seawater [11]. This has led to the successful discovery of various classes of new natural products [12,13,14,15,16,17,18] from volcanic island-derived marine actinomycetes. These include new cyclic peptides with anticancer and antituberculosis activities, ohmyungsamycins A and B [12], new anti-inflammatory linear polyketides, succinilenes A–D [17], and donghaesulfins A and B, which are dimeric benz[a]anthracenes linked through a sulfide bond [18]. By changing the culture conditions of the donghaesulfin-producing strain Streptomyces sp. SUD119, which was isolated from a marine sediment sample from a volcanic island (Ulleung Island) located in the middle of Donghae Sea of the Republic of Korea, we produced the new arranged angucyclinone metabolites donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) (Figure 1). Large-scale fermentation of the SUD119 strain and further chromatographic purification resulted in the yield of 1–3 for subsequent spectroscopic analyses of these compounds. Here, we report the isolation, structural elucidation (in particular, the application of computational techniques for the establishment of configuration, including ECD calculations), and biological activities of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3).

Figure 1.

The structures of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure Elucidation

Donghaecyclinone A (1) was obtained as a white powder of molecular formula C20H18O5 on the basis of high resolution-fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry (HR-FABMS) (obsd [M + H]+ at m/z 339.1227, calcd [M + H]+ at m/z 339.1231). The combination of 1H, 13C, and heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR data (Table 1) of 1 in DMSO-d6 revealed that donghaecyclinone A (1) contains a carbonyl carbon (δC 198.9), five double-bond methine signals (δC/δH: 127.6/7.49, 131.5/7.27, 111.7/7.10, 122.2/7.00, and 111.5/6.94), and seven non-protonated double-bond carbons (δC: 153.6, 148.5, 148.3, 140.4, 126.3, 125.9, and 122.9). Through further interpretation of the NMR data, we identified three sp3 oxymethines (δC/δH: 98.7/6.86, 77.3/6.68, and 71.4/4.22), a methoxy group (δC/δH: 55.6/3.85), one aliphatic methylene (δC/δH: 44.3/2.81 and 2.32), one aliphatic methine (δC/δH: 37.0/2.08), and one methyl group (δC/δH: 17.6/1.04). The molecular formula of 1 suggests that donghaecyclinone A (1) should possess 12 degrees of unsaturation. Because one carbonyl group and 12 double-bond carbons constituting six double bonds accounted for seven of the 12 degrees of unsaturation, donghaecyclinone A (1) must be a pentacyclic compound.

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR data for 1–3.

| 1 a | 2 b | 3 b | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C/H | δH c | mult (J in Hz) | δC c | C/H | δH c | mult (J in Hz) | δC c | δH c | mult (J in Hz) | δC c |

| 1 | 198.9, s | 1 | 201.2, s | 200.4, s | ||||||

| 2α | 2.81 | dd (16.0, 4.5), 1H | 44.3, t | 2α | 2.81 | dd (15.0, 4.5), 1H | 46.8, t | 2.99 | dd (15.0, 4.5), 1H | 45.6, t |

| 2β | 2.32 | dd (16.0, 12.0), 1H | 2β | 2.64 | dd (15.0, 10.0), 1H | 2.38 | dd (15.0, 10.0), 1H | |||

| 3 | 2.08 | m, 1H | 37.0, d | 3 | 2.29 | m, 1H | 39.6, d | 2.24 | m, 1H | 38.2, d |

| 3- | 1.04 | d (6.5), 3H | 17.6, q | 3- | 1.20 | d (6.5), 3H | 18.9, q | 1.18 | d (6.5), 3H | 18.0, q |

| Me | Me | |||||||||

| 4 | 4.22 | dd (7.5, 6.0), 1H | 71.4, d | 4 | 4.55 | d (6.5), 1H | 74.4, d | 4.43 | d (6.5), 1H | 73.4, d |

| 4- | 5.61 | d (6.0), 1H | 4- | 4.69 | brs, 1H | 4.74 | brs, 1H | |||

| OH | OH | |||||||||

| 4a | 140.4, s | 4a | 139.9, s | 140.1, s | ||||||

| 5 | 7.49 | d (8.5), 1H | 127.6, d | 5 | 7.59 | d (8.5), 1H | 130.5, d | 7.63 | d (8.5), 1H | 129.4, d |

| 6 | 7.00 | d (8.5), 1H | 122.2, d | 6 | 7.03 | d (8.5), 1H | 122.0, d | 7.05 | d (8.5), 1H | 121.9, d |

| 6a | 148.5, s | 7 | 157.5, s | 157.3, s | ||||||

| 7 | 6.86 | s, 1H | 98.7, d | 7- | 8.83 | brs, 1H | 8.80 | brs, 1H | ||

| 7a | 122.8, s | OH | ||||||||

| 8 | 153.6, s | 7a | 122.9, s | 122.8, s | ||||||

| 7b | 133.9, s | 132.7, s | ||||||||

| 8- | 3.85 | s, 3H | 55.6, q | 1′ | 169.3, s | 169.3, s | ||||

| OMe | 3′ | 7.43 | s, 1H | 76.4, d | 7.41 | s, 1H | 76.5, d | |||

| 9 | 6.94 | t (8.5), 1H | 111.5, d | 3′a | 153.9, s | 153.8, s | ||||

| 10 | 7.27 | t (8.5), 1H | 131.5, d | 4′ | 6.92 | d (8.5), 1H | 115.1, d | 6.93 | d (8.5), 1H | 115.0, d |

| 11 | 7.10 | d (8.5), 1H | 111.7, d | 5′ | 7.54 | t (8.5), 1H | 136.2, d | 7.54 | t (8.5), 1H | 136.1, d |

| 11a | 148.3, s | 6′ | 7.04 | d (8.5), 1H | 111.3, d | 7.04 | d (8.5), 1H | 111.2, d | ||

| 12 | 6.68 | s, 1H | 77.3, d | 7′ | 158.9, s | 158.8, s | ||||

| 12a | 125.9, s | 7′a | 116.0, s | 115.8, s | ||||||

| 12b | 126.3, s | 7′- | 3.93 | s, 3H | 56.1, q | 3.94 | s, 3H | 56.0, q | ||

| OMe | ||||||||||

a DMSO-d6, b acetone-d6, c 1H, and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 600 and 150 MHz, respectively.

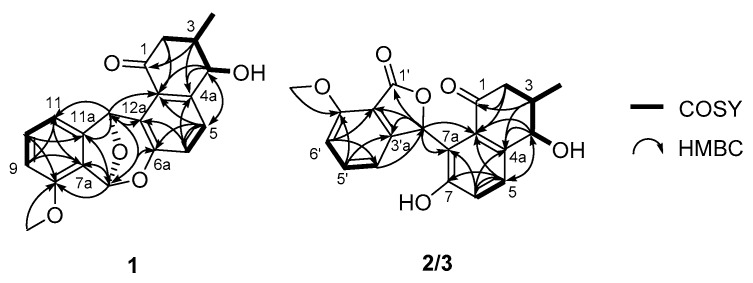

After establishing all of the 1H-13C one-bond correlations that were assigned by the analysis of the HSQC NMR spectrum, structural fragments of 1 were assembled by the interpretation of ¹H-¹H correlated spectroscopy (COSY) and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) NMR spectra. The COSY correlations from H2-2 (δH 2.81 and 2.32) to H-3 established the connection between C-2 (δC 44.3) and C-3 (δC 37.0). H-3 was found to be correlated with H3-3-Me (δH 1.04) and H-4 (δH 4.22), establishing that 3-Me (δC 17.6) and C-4 (δC 71.4) were bound to C-3. An additional COSY analysis verified the connection between H-4 and 4-OH (δH 5.61). The HMBC correlations from H2-2/H-3 to C-1 (δC 198.9), from H-3/H-4 to C-4a (δC 140.4), and from H-4 to C-12b (δC 126.3) established the first partial structure as a 4-hydroxy-3-methylcyclohexenone moiety (A ring). The characteristic vicinal coupling (J = 8.5 Hz) of H-5 and H-6 indicated that they were in a three-bond relationship in a six-membered aromatic ring, thus directly connecting C-5 and C-6. The three-bond 1H–13C couplings from H-5 to C-8a and C-12b, and from H-6 to C-4a and C-6a were assigned as a six-membered aromatic ring (B ring) composed of C-4a, C-5, C-6, C-6a, C-12a, and C-12b, which was then connected to the A ring as revealed by H-4/C-5, H-5/C-4, and H-4/C-12b HMBC correlations.

An array of COSY correlations (H-9 (δH 6.94), H-10 (δH 7.27), and H-11 (δH 7.49)) and their coupling constants (J = 8.5 Hz each) clearly showed that C-9 (δC 111.5), C-10 (δC 131.5), and C-11 (δC 111.7) were connected in another six-membered aromatic spin system. The HMBC correlations from H-9 to C-7a (δC 122.8) and C-11, from H-10 to C-8 (δC 153.6) and C-11a (δC 148.3), and from H-11 to C-7a and C-9 constructed the D ring. The 8-OMe (δH 3.85) was shown to have an HMBC correlation with C-8, suggesting that the A ring is an anisole. Once the A, B, and D rings were constructed with 18 out of the 20 carbons in the molecular formula of donghaecyclinone A (1), these three rings were assembled based on HMBC correlations between the unused oxymethine protons (H-12 and H-7). H-12 exhibited 2,3JCH couplings to C-11, C-11a, C-12a, and C-12b, establishing connectivity between the B and D rings through the C-12 oxymethine, which forms a seven-membered ring. The HMBC correlations from H-7 to C-6a, C-7a, C-8, and C-11a also connected the B and D rings through C-7. Due to the deshielded chemical shift (δC 98.7) of C-7, it was suggested that this carbon was dioxygenated. In addition, donghaecyclinone A, being a pentacyclic compound, requires one more ring. The last ring (Cb ring) was determined to be a tetrahydrofuran based on the H-7/C-12 and H-12/C-7 HMBC correlations, which also meets the requirement of two oxygen atoms for C-7, and constructed the dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octadiene moiety. Therefore, the planar structure of donghaecyclinone A (1) was determined to be that of a 6/6/6/5/6 pentacyclic natural product (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Determination of the planar structures of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) based on the analysis of key COSY and HMBC correlations.

Donghaecyclinone B (2) was isolated as a white powder. Its molecular formula was determined to be C20H18O6 based on the HR-FABMS (obsd [M − H]− at m/z 353.1033, calcd [M − H]− at m/z 353.1031). The 1-D and 2-D NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1) of 2 showed similar features to those of 1, indicating that donghaecyclinone B is also a polyunsaturated aromatic natural product. Analysis of the 1H, 13C, and HSQC NMR data revealed the presence of two carbonyl carbons (δC 201.2 and 169.3), five aromatic methines (δC/δH: 136.2/7.54, 130.5/7.59, 122.0/7.03, 115.1/6.92, and 113.3/7.04), seven non-protonated aromatic carbons (δC 158.9, 157.5, 153.9, 139.9, 133.9, 122.9, and 116.0), two oxymethines (δC/δH: 76.4/ 7.43 and 74.4/4.55), one methoxy group (δC/δH: 56.1/3.93), one aliphatic methylene (δC/δH: 46.8/2.81 and 2.64), one aliphatic methine (δC/δH: 39.6/2.29), one methyl group (δC/δH: 18.9/1.20), and two hydroxy group protons (δH 8.83 and 4.69). Detailed comparison of the NMR data with those of 1 revealed that donghaecyclinone B contains an additional carbonyl carbon (δC 169.3) and hydroxy proton (δH 8.83) while it lacks the C-7 acetal methine carbon (δC/δH: 98.7/6.86) found in 1. Based on its molecular formula, we determined that donghaecyclinone B bears 11 unsaturation equivalents. Two carbonyl functional groups and 12 double-bond signals comprising six double bonds correspond to seven degrees of unsaturation, indicating that donghaecyclinone B (2) is a tetracyclic compound. Further interpretation of the COSY and HMBC NMR spectral data of 2 established a 4-hydroxy-3-methylcyclohexenone moiety (A ring), a hydroxy benezene (B ring), and an anisole (D ring) composed of 18 carbons; the remaining two unassigned carbons were a carbonyl carbon (δC 169.3) and a oxymethine (δC/δH 76.4/7.43). To accommodate these, the HMBC correlations from H-3′ (δH 7.43) to C-1′ (δC 169.3), C-3′a (δC 153.9), C-7′a (δC 116.0), C-7a (δC 122.9), and C-7b (δC 133.9) established γ-lactone as the last ring (C ring) and thus completed the tetracyclic planar structure of 2 (Figure 2).

Donghaecyclinone C (3) was obtained as a white powder along with 1 and 2. The molecular formula was determined to be C20H18O6 on the basis of HR-FABMS (obsd [M − H]− at m/z 353.1033, calcd [M − H]− at m/z 353.1031). The molecular formula and the UV spectrum of 3 were identical to those of 2, indicating that the structure of donghaecyclinone C (3) is similar to that of 2. A comprehensive analysis of the 1D and 2D NMR data (Table 1) revealed that the planar structure of donghaecyclinone C (3) is identical to that of 2 (Figure 2). However, the optical rotations of 2 and 3 were found to have opposite signs with different absolute values (+125.6 and −156.7, respectively). This observation indicated that these two compounds were diastereomers, and not enantiomers, requiring rigorous stereochemical determination.

2.2. Determination of the Configurations of Donghaecyclinones A–C

Even though a number of angucycline/angucyclinone-class natural products were discovered to be representative polyketide type II metabolites from actinobacteria, mainly from the genus Streptomyces [19,20,21,22], they are often reported with undetermined configurations [23]. This is partly because the benzene ring in the middle of their structures makes it impossible to relate their relative configurations across all of the molecules. In addition, the absolute configurations of the rearranged angucyclinones (LS1924A and emycin D), such as donghaecyclinone A, that bear a dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octadiene structure by rearrangement from ordinary angucyclinones have not been determined or have only been assigned by X-ray crystallography [23,24]. Furthermore, the stereochemistry of the rearranged angucyclinones that incorporate isobenzofuran, such as donghaecyclinones B and C, has not been rigorously studied [25]. Application of the DP4 or CP3 method would enable to relate the relative configurations, and utilization of electronic circular dichroism (ECD) calculations facilitates determination of the absolute configurations of angucyclinone-class compounds.

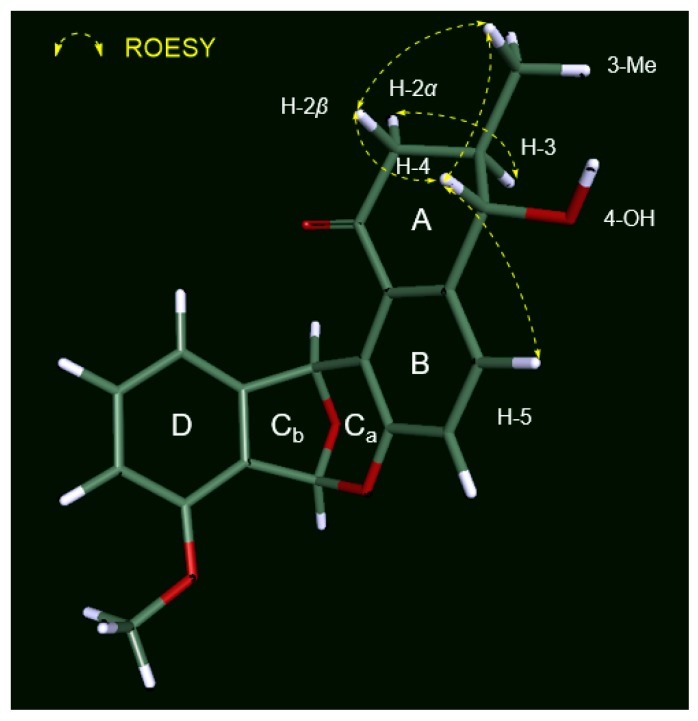

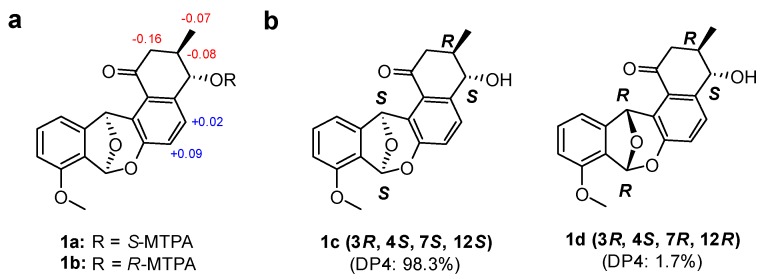

The relative configuration of 1 in ring A was established based on its 3JHH values and rotating-frame Overhauser spectroscopy (ROESY) NMR spectroscopic data (Figure 3). The large 1H-1H coupling constant (7.5 Hz) between H-3 and H-4 strongly implied an anti-relationship between H-3 and H-4 and their axial orientation. The observed H-2β/H3-3-Me and H-2β/H-4 ROESY correlations assigned these protons on the same face in the A ring. The absolute configuration of the stereogenic center at C-4 was determined by a modified version of Mosher’s method by utilizing α-methoxy-α-trifluoromethylphenylacetic acid (MTPA) esterification and 1H NMR analysis (Figure 4a) [26]. Due to steric hindrance, additional R-MTPA-Cl was required to establish the S-MTPA ester (1a) in longer reaction time. Analysis of the 1H and 2D NMR spectroscopic data for the S- and R-MTPA esters (1a and 1b) enabled us to calculate the ΔδS-R values; on this basis, we determined its absolute configuration to be 4S. Based on the relative relationship between C-3 and C-4, the absolute configuration of C-3 was also determined to be R.

Figure 3.

Key ROESY correlations of donghaecyclinone A (1).

Figure 4.

Determination of the absolute configuration of donghaecyclinone A (1). (a) ΔδS-R values of the MTPA esters (1a and 1b) in DMSO-d6. (b) the simulated DP4 models of the two possible diastereomers 1c/1d (3R, 4S, 7S, and 12S/3R, 4S, 7R, and 12R) of 1.

However, the relative configuration of C-7 and C-12 at the junction of rings Ca and Cb could not be established because we did not observe any ROESY correlations between the A and Ca/Cb rings. To overcome this challenge, a quantum mechanics-based computational analysis using a DP4 statistical calculation was applied [6]. The two possible diastereomers 1c (3R, 4S, 7S, and 12S) and 1d (3R, 4S, 7R, and 12R) were proposed, and the 1H and 13C chemical shifts of the 12 conformers of 1c and 1d were calculated with their Boltzmann averaged populations. Based on a comparison of the experimental and calculated chemical shift values, our computational shielding tensor predicted diastereomer 1c (3R, 4S, 7S, and 12S configurations) with 98.3% probability (Figure 4b). Finally, the absolute configuration of donghaecyclinone A (1) was proposed to be 3R, 4S, 7S, and 12S.

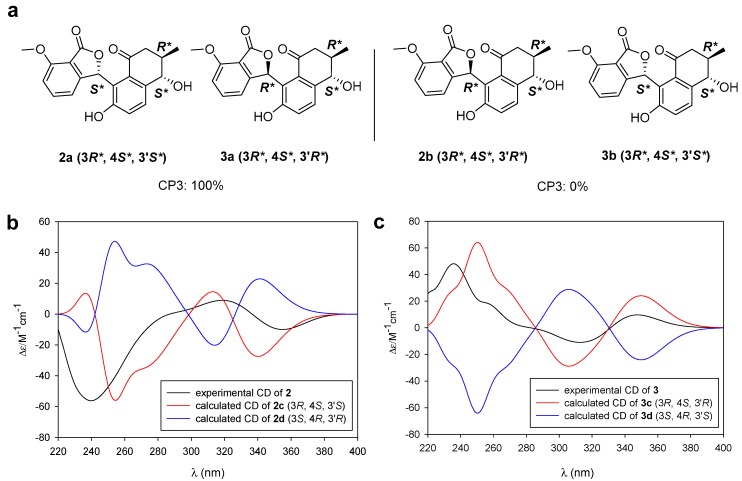

The relative configurations of the C-3 and C-4 positions in 2 and 3 were determined to be 3R* and 4S* based on analyses of the three-bond 1H-1H homonuclear coupling constants and ROESY correlations (Figures S23 and S24). In the analysis of NMR data, donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3) were expected to be diastereomers. Because both donghaecyclinones B and C possess the same 3R* and 4S* configurations and C-3′ in 2 and 3 is the only remaining chiral center with an undetermined relative configuration, these compounds must have opposite configurations at C-3′.

For assignment of the relative configuration at C-3′, the two sets of possible diastereomers 2a/3a and 2b/3b were considered with 3R* and 4S* configurations (Figure 5a). In this case, the CP3 calculation—which was specially devised for the assignment of relative configuration to two plausible diastereomers from two sets of experimental NMR data—was applied instead of DP4 [5]. Our CP3 probability analysis of 2 and 3 along with the experimental and the calculated chemical shift values showed that the relative configurations of 2 and 3 were 3R*, 4S*, and 3′S* and 3R*, 4S*, and 3′R*, respectively, with 100% probability.

Figure 5.

Determination of the relative and absolute configurations of donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3). (a) The simulated CP3 models of two possible diastereomer sets 2a/3a (3R*, 4S*, and 3′S*/3R*, 4S*, and 3′R*) and 2b/3b (3R*, 4S*, and 3′R*/3R*, 4S*, and 3′S*) on 2 and 3. (b) Experimental and calculated ECD spectra of 2, 2c, and 2d. (c) Experimental and calculated ECD spectra of 3, 3c, and 3d.

To determine the absolute configuration of 2 and 3, we initially applied the modified version of Mosher’s method. However, during the MTPA derivatization, donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3) underwent isomerization at C-3′ at the furanone moiety, which prevented us from obtaining pure MTPA ester products. This problem was circumvented by the application of ECD calculation [27]. First, the energy-minimized conformers of 2c (3R, 4S, and 3′S) and its enantiomer 2d (3S, 4R, and 3′R) were calculated (Tables S6–S9). The ECD calculations of the two enantiomers (2c and 2d) of 2 were performed using TD-DFT at the B3LYP/def-SVP//B3LYP/def-SVP level for all atoms. A comparison of the experimental ECD spectrum of 2 and the calculated ECD spectra of 2c and 2d showed that the experimental ECD spectrum of 2 is consistent with the calculated ECD spectrum of 2c. Thus, we assigned 2 as having an absolute configuration of 3R, 4S, and 3′S (Figure 5b). The absolute configuration of 3 was determined to be 3R, 4S, and 3′R through a comparison of its experimental ECD spectrum with the calculated ECD spectra of two enantiomers (3c and 3d) using the same procedure (Figure 5c).

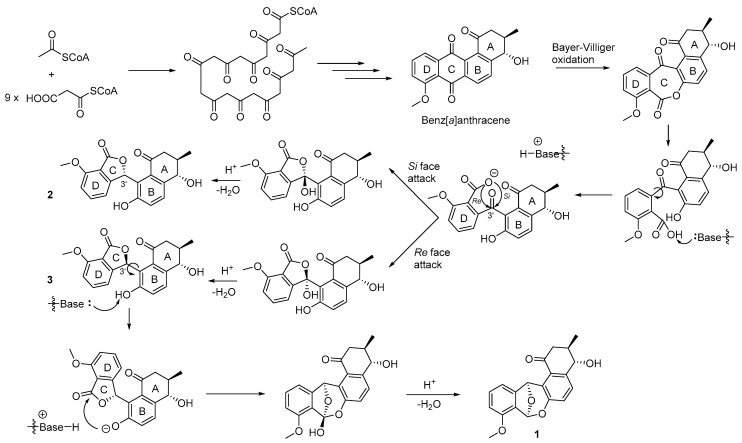

2.3. Proposed Biosynthesis of Donghaecyclinones A–C

The typical benz[a]anthracene structure of the angucycline/angucyclinone class metabolites is biosynthesized from acetyl CoA and nine malonyl CoA extender units through a type II polyketide synthase (PKS II) pathway [19,20,21,22]. From the common benz[a]anthracene precursor, the biosynthesis of the rearranged angucyclinones, donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3), was proposed (Figure 6). The C ring of benz[a]anthracene can be cleaved through Bayer-Villiger oxidation and hydrolysis of the ester linkage. Then the deprotonated carboxylate anion in the D ring attacks the carbonyl carbon at C-3′ position of donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3) followed by dehydration to furnish 2 and 3. During the C ring formation, both Si and Re face attacks may occur, resulting in the production of the 3′-epimeric structures of donghaecyclinones B and C (Figure 6). These compounds were obviously observed as natural products in the bacterial culture of before fractionation (Figure S29). Donghaecyclinone A (1) could be derived from 3 to form the dioxabicylo[3.2.1]octadiene structure by the nucleophilic attack to the ester carbonyl group in the C ring by the phenolic oxygen in the B ring and dehydration (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3).

2.4. Biological Activities of Donghaecyclinones A–C

The biological activities of the angucycline/angucyclinone-class natural products are known to include cytotoxicity against various cancer cell lines and antibacterial activity [15,16,17]. Donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) were evaluated for antibacterial activity against Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 19433, Enterococcus faecium ATCC 19434, Gram-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 10031, Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028, and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 using ampicillin as a positive control. In this assay, none of the donghaecyclinones displayed significant inhibitory activity [MIC > 100 μg/mL]. The antifungal activity of 1–3 against Aspergillus fumigatus HIC 6094, Trichophyton rubrum NBRC 9185, Trichophyton mentagrophytes IFM 40996, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 was measured, and the donghaecyclinones were not found to inhibit the growth of these pathogenic fungi [MIC > 100 μg/mL]. In the cytotoxicity assay against five cancer cell lines—HCT116 (a colon cancer cell line), MDA-MB231 (a breast cancer cell line), SNU638 (a gastric carcinoma cell line), A549 (a lung cancer cell line), and SK-HEP1 (a liver cancer cell line)—donghaecyclinone C displayed significant inhibitory activity (IC50 = 6.0–9.6 μM) while donghaecyclinones A and B exhibited lower cytotoxicity (IC50 = 9.6–28.9 μM) (Table 2, Figure S30). Donghaesulfins A and B, the dimeric-angucyclinones reported by our previous work with the donghaecyclinone-producing bacterial strain (Streptomyces sp. SUD119), did not show remarkable cytotoxicity [14], possibly indicating that dimerization provides negative effects on the angucyclinone class compounds. Based on the difference of the cytotoxicity between donghaecyclinones B and C and their structures, the C-3′ stereogenic center apparently plays a significant role in the cytotoxicity of isobenzofuran-bearing rearranged angucyclinone metabolites. However, the mechanism causing the difference in cytotoxicity is unknown and requires further studies.

Table 2.

The cytotoxicity assay for donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3).

| Cytotoxicity (IC50 μM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT116 | MDA-MB231 | SNU638 | A549 | SK-HEP1 | |

| 1 | 28.9 | 20.0 | 16.1 | 22.9 | 14.2 |

| 2 | 27.3 | 19.3 | 19.6 | 19.0 | 9.6 |

| 3 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 6.0 |

| Etoposide | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

3. Experimental

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were obtained using a JASCO P-200 polarimeter (JASCO, Easton, PA, USA) with a sodium light source and a 1 cm cell. UV spectra were acquired on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 35 UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). IR spectra were acquired using a Thermo Nicolet iS10 detector (Thermo, Madison, CT, USA). ECD spectra were recorded on an Applied Photophysics Chirascan-plus circular dichroism spectrometer. 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR spectra were acquired on Bruker Avance 600 MHz and 850 MHz spectrometers (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) at the National Center for Inter-University Research Facilities (NCIRF) at Seoul National University. High-resolution fast atom bombardment (HR-FAB) mass spectra were recorded using a Jeol JMS-600W high-resolution mass spectrometer (Jeol, München, Germany) at the NCIRF. LC/MS data were obtained on an Agilent Technologies 6130 quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with an Agilent Technologies 1200 series HPLC.

3.2. Cultivation and Extraction

The isolation and phylogenetic analysis of the Streptomyces sp. bacterial strain SUD119 were previously reported [18]. Strain SUD119 was inoculated in 50 mL of YEME medium (4 g of yeast extract, 10 g of malt extract, and 4 g of glucose in 1 L of artificial seawater) in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The bacterial strain was cultivated for 3 days on a rotary shaker at 160 rpm at 30 °C. The liquid culture (10 mL) was inoculated directly into 1 L of A1 liquid medium (4 g of yeast extract, 10 g of starch, and 4 g of peptone in 1 L of artificial seawater) in 2.8 L Fernbach flasks (1 L in each of 12 flasks for a total volume of 12 L). After cultivation for eight days, the 12 L culture of the SUD119 strain was extracted using 18 L of EtOAc. The EtOAc layer was separated from the water layer. To remove residual water, anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to the EtOAc layer. The cultivation and extraction procedures were repeated 12 times (total culture volume: 144 L). The EtOAc extract was dried in vacuo, and 12 g of dry extract material was obtained.

3.3. Isolation of Donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3)

The dried extract of the SUD119 strain was redissolved in MeOH and filtered through a syringe filter (PVDF). The filtered extract was then injected directly onto a semipreparative reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (Kromasil C18 (2): 250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm), and the material was separated with a gradient solvent system (20% MeOH/H2O to 80% MeOH/H2O over 40 min and 80% MeOH/H2O for 40 min, UV detection at 280 nm, flow rate: 2 mL/min). Two major peaks at retention times of 20.4 and 38.6 min were observed. These major fractions were analyzed by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS). The fraction collected at 20.4 min contained donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3), and the other major fraction obtained at 38.6 min was composed of pure donghaecyclinone A (1, 4.2 mg). The mixture of donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3) was further purified using an isocratic HPLC solvent system (48% MeOH/H2O, UV detection at 280 nm, flow rate: 2 mL/min) using a reversed-phase C18 HPLC column (Kromasil C18 (2): 250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm). Donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3) were acquired at retention times of 28.2 min (3.5 mg) and 31.6 min (4.1 mg), respectively.

Donghaecyclinone A (1): White powder; −6.9 (c 0.5, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.32), 260 (3.86), 325 (3.58) nm; IR (neat) νmax 3282, 2971, 1682, 1577, 1517 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, Table 1; HR-FABMS m/z 339.1227 [M + H]+ (calcd for C20H19O5, 339.1231).

Donghaecyclinone B (2): White powder; −125.6 (c 0.5, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.21), 300 (3.62), 320 (3.46) nm; ECD (c 4.2 × 10−4 M, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 238 (−56.4) nm, 286 (+0.7) nm, 318 (+8.6) nm, 354 (−9.9) nm; IR (neat) νmax 3338, 2961, 1752, 1672, 1607, 1487 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, Table 1; HR-FABMS m/z 353.1033 [M − H]− (calcd for C20H17O6, 353.1031).

Donghaecyclinone C (3) White powder; +156.7 (c 0.5, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.27), 300 (3.65), 320 (3.44) nm; ECD (c 4.2 × 10−4 M, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 235 (+48.0) nm, 255 (+18.8) nm, 288 (−1.7) nm, 315 (−11.2) nm, 345 (+9.6) nm; IR (neat) νmax 3363, 2964, 1752, 1673, 1607, 1485 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, Table 1; HRFABMS m/z 353.1033 [M − H]− (calcd for C20H17O6, 353.1031).

3.4. MTPA Esterification of Donghaecylinone A (1)

Donghaecyclinone A (1) was placed into two 40 mL vials (1 mg for each) and dried for 18 h under high vacuum. A catalytic amount of crystalline dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) was then added to each of the vials containing 1. Distilled anhydrous pyridine (1 mL) was added to each vial under Ar. The reaction mixtures were stirred at room temperature for 5 min. Then, 20 µL of S- or R-α-methoxy trifluoromethylphenylacetic acid (MTPA) chloride was added to each vial. The reaction with S-MTPA-Cl was maintained with stirring for 3 h at room temperature and then quenched by the addition of 50 µL of MeOH, furnishing the R-MTPA ester (1b) of 1. To yield the S-MTPA ester (1a), the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h with an additional amount of R-MTPA-Cl (20 µL) to facilitate esterification, and then quenched by the addition of 50 µL of MeOH. The reaction products (1a and 1b) were isolated by HPLC using gradient elution conditions (40% to 100% aqueous CH3CN over 20 min, a reversed-phase C18 column (Kromasil C18 (2): 250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm), flow rate: 2 mL/min, UV detection at 280 nm). The S- and R-MTPA esters (1a and 1b) of 1 eluted at 33.4 and 32.6 min, respectively. The ΔδS-R values of the signals around stereogenic centers of the MTPA esters were assigned based on analysis of the 1H and 1H–1H COSY NMR spectra.

3.4.1. The S-MTPA Ester (1a) of Donghaecyclinone A (1)

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.50–7.44 (m, 5H), 7.31 (t, J = 8.0, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 6.65 (s, 1H), 6.04 (d, J = 5.0, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.45 (s, 3H), 2.76 (dd, J = 16.0, 4.5, 1H), 2.58 (m, 1H), 2.44 (dd, J = 16.0, 6.0, 1H), 0.87 (d, J = 6.5, 3H). The molecular formula of 1a was determined to be C30H25F3O7 ([M + Na]+ at m/z 577).

3.4.2. The R-MTPA Ester (1b) of Donghaecyclinone A (1)

1H NMR (800 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.48–7.43 (m, 5H), 7.29 (t, J = 8.0, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 7.11c (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.63 (s, 1H), 6.04 (d, J = 5.0, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.50 (s, 3H), 2.98 (dd, J = 16.0, 4.5, 1H), 2.66 (m, 1H), 2.52 (dd, J = 16.0, 6.0, 1H), 0.94 (d, J = 6.5, 3H). The molecular formula of 1b was determined to be C30H25F3O7 ([M + Na]+ at m/z 577).

3.5. DP4 and CP3 Analyses

A conformational search was performed using the MacroModel (Version 9.9, Schrödinger LLC, New York, NY, USA) program in Maestro (Version 9.9, Schrödinger LLC) with a mixed torsional/low-mode sampling method. Conformers of diastereomers within 10 kJ/mol, as calculated by the MMFF force field, were selected. The geometries of the conformers were calculated for optimization at the B3LYP/6-31G++ level in gas phase. The shielding tensor values of the optimized conformers were calculated on the basis of the equation below, where is the calculated NMR chemical shift for nucleus , and is the shielding tensor for the proton and carbon nuclei calculated at the B3LYP/6-31++ level. These values were averaged via the Boltzmann population with the associated Gibbs free energy and utilized for the DP4 and CP3 analyses, which were facilitated by an Excel sheet provided by the original authors.

| (1) |

3.6. ECD Calculation

The ground-state geometries were computed with density functional theory (DFT) calculations using Turbomole 6.5, the basis set def-SVP for all atoms, and the B3LYP/DFT functional level. The ground states were further confirmed using a harmonic frequency calculation. The calculated ECD data corresponding to the optimized structures were acquired with TD-DFT at the B3LYP/DFT functional level using the basis set def-SVP for all atoms. The CD spectra were simulated by overlapping for each transition according to the equation below, where σ is the width of the band at the height of 1/e and ΔEi and Ri are the excitation energies and rotatory strengths for transition i, respectively. In the present work, the value of σ was taken to be 0.10 eV.

| (2) |

3.7. Antibacterial Activity Bioassay

The inhibitory activities of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) were evaluated against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 19615, and Kocuria rhizophila NBRC 12708) and Gram-negative bacteria (Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 10031, Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and Proteus hauseri NBRC) using the previously reported method [18].

3.8. Antifungal Activity Bioassay

Trichophyton mentagrophytes IFM 40996, Trichophyton rubrum NBRC 9185, Aspergillus fumigatus HIC 6094, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 strains were used to measure the antifungal activities of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) by following the previously reported procedure [18].

3.9. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) were evaluated using a sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay as previously reported [14]. The five human cancer cell lines A549, MDA-MB231, HCT116, SNU638, and SK-HEP1 were tested with etoposide as a positive control.

4. Conclusions

We discovered donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3) in Streptomyces sp. strain SUD119, which was isolated from a sample of marine sediment collected from the volcanic island (Ulleung Island) in the Republic of Korea. Donghaecyclinone A possesses a pentacyclic skeleton with a dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octadiene structure derived from benz[a]anthracene, the typical structure of angucyclinone-class natural products. Donghaecyclinones B and C possess an isobenzofuran moiety that is also a rearrangement of benz[a]anthracene. The absolute configurations of 1–3 were fully established by computational methods utilizing NMR shielding tensor and ECD along with a modified version of Mosher’s method. To date, the configurations of angucyclinones with a dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octadiene moiety have remained undetermined or have been established occasionally by X-ray crystallography. The stereochemistry of rearranged angucyclinones that bear isobenzofuran has not been rigorously examined. This configurational analysis of these rearranged angucyclinone-class compounds by quantum mechanics-based computational tools constitutes a general method for the structural characterization of rearranged angucyclinones and related natural products.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/18/2/121/s1. Figures S1–S6. 1D and 2D NMR spectra of donghaecyclinone A (1); Figure S7. IR spectrum of donghaecyclinone A (1); Figure S8: 1H NMR spectrum (800 MHz) of S-MTPA ester (1a); Figure S9: COSY spectrum (800 MHz) of S-MTPA ester (1a); Figure S10. 1H NMR spectrum (800 MHz) of R-MTPA ester (1b); Figure S11. COSY spectrum (800 MHz) of R-MTPA ester (1b); Figures S12–S18. 1D and 2D spectra of donghaecyclinone B (2); Figure S19. IR spectrum of donghaecyclinone B (2); Figures S20–S25: 1D and 2D NMR spectra of donghaecyclinone B (3); Figure S26: IR spectrum of donghaecyclinone C (3); Figure S27. Key ROESY correlations of donghaecyclinone B (2); Figure S28: Key ROESY correlations of donghaecyclinone C (3); Figure S29: LC/MS chromatogram of the extract of the bacterial strain Streptomyces sp. SUD119 and purified donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3). Figure S30: Cytotoxicity result of donghaecyclinones A–C (1–3); Tables S1–S3. The major conformers of diastereomers 1c–1d, 2a, 2b, 3a, and 3b identified by conformational searches in MMFF94 force field using MacroModel; Table S4. Experimental (Exp.) and calculated (Cal.) chemical shift values (CS, δ) of diastereomers 1c–1d on donghaecyclinone A (1); Table S5. Experimental (Exp.) and calculated (Cal.) chemical shift values (CS, δ) of diastereomers 2a/3b–2b/3a on donghaecyclinones B and C (2 and 3): Cartesian coordinates of the conformers shown in Tables S4 and S5; Tables S6–S9. ECD calculation of 2c, 2d, 3c, and 3d.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and D.-C.O.; Data curation, S.K.L.; Formal analysis, M.B. and K.-B.O.; Funding acquisition, D.-C.O.; Investigation, M.B., J.S.A., S.-H.H., E.S.B., B.C., K.-B.O., S.K.L. and D.-C.O.; Resources, Y.K.; Supervision, J.S. and D.-C.O.; Validation, M.B.; Visualization, M.B., J.S.A. and S.H.; Writing—original draft, M.B. and D.-C.O.; Writing—review and editing, S.H. and S.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Collaborative Genome Program of the Korean Institute of Marine Science and Technology Promotion (KIMST) (No. 20180430). This work was also supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (the Ministry of Science and ICT/2018R1A4A1021703).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bifulco G., Dambruoso P., Gomez-Paloma L., Riccio R. Determination of relative configuration in organic compounds by NMR spectroscopy and computational methods. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3744–3749. doi: 10.1021/cr030733c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duus J.Ø., Gotfredsen C.H., Bock K. Carbohydrate structural determination by NMR spectroscopy: modern methods and limitations. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:4589–4614. doi: 10.1021/cr990302n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lodewyk M.W., Siebert M.R., Tantillo D.J. Computational prediction of 1H and 13C chemical shifts: A useful tool for natural product, mechanistic, and synthetic organic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:1839–1862. doi: 10.1021/cr200106v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ermanis K., Parkes K.E.B., Agback T., Goodman J.M. The optimal DFT approach in DP4 NMR structure analysis–pushing the limits of relative configuration elucidation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019;17:5886–5890. doi: 10.1039/C9OB00840C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith S.G., Goodman J.M. Assigning the stereochemistry of pairs of diastereoisomers using GIAO NMR shift calculation. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4597–4607. doi: 10.1021/jo900408d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith S.G., Goodman J.M. Assigning stereochemistry to single diastereoisomers by GIAO NMR calculation: The DP4 probability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12946–12959. doi: 10.1021/ja105035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nugroho A.E., Morita H. Circular dichroism calculation for natural products. J. Nat. Med. 2014;68:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11418-013-0768-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X.-C., Ferreira D., Ding Y. Determination of absolute configuration of natural products: Theoretical calculation of electronic circular dichroism as a tool. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010;14:1678–1697. doi: 10.2174/138527210792927717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bringmann G., Bruhn T., Maksimenka K., Hemberger Y. The assignment of absolute stereostructures through quantum chemical circular dichroism calculations. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009;17:2717–2727. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200801121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenical W., Jensen P.R. Developing a new resource for drug discovery: Marine actinomycete bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:666–673. doi: 10.1038/nchembio841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srinivas T.N.R., Anil Kumar P., Tank M., Sunil B., Poorna M., Zareena B., Shivaji S. Aquipuribacter nitratireducens sp. nov., isolated from a soil sample of a mud volcano. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015;65:2391–2396. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Um S., Choi T.J., Kim H., Kim B.Y., Kim S.-H., Lee S.K., Oh K.-B., Shin J., Oh D.-C. Ohmyungsamycins A and B: Cytotoxic and antimicrobial cyclic peptides produced by Streptomyces sp. from a volcanic island. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:12321–12329. doi: 10.1021/jo401974g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hur J., Jang J., Sim J., Son W.S., Ahn H.-C., Kim T.S., Shin Y.-H., Lim C., Lee S., An H., et al. Conformation-enabled total syntheses of ohmyungsamycins A and B and structural revision of ohmyungsamycin B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:3069–3073. doi: 10.1002/anie.201711286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim T.S., Shin Y., Lee H.-M., Kim J.K., Choe J.H., Jang J.-C., Um S., Jin H.S., Komatsu M., Cha G.-H., et al. Ohmyungsamycins promote antimicrobial responses through autophagy activation via AMP-activated protein kinase pathway activation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3431. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03477-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim E., Shin Y.-H., Kim T.H., Byun W.S., Cui J., Du Y.E., Lim H.-J., Song M.C., Kwon A.S., Kang S.H., et al. Characterization of the ohmyungsamycin biosynthetic pathway and generation of derivatives with improved antituberculosis activity. Biomolecules. 2019;9:672. doi: 10.3390/biom9110672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byun W.S., Kim S., Shin Y.-H., Kim W.K., Oh D.-C., Lee S.K. Antitumor activity of ohmyungsamycin A through the regulation of the Skp2-p27 axis and MCM4 in human colorectal cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:118–126. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae M., Park S., Kwon Y., Lee S.K., Shin J., Nam J.-W., Oh D.-C. QM-HiFSA-aided structure determination of succinilenes A–D, new triene polyols from a marine-derived Streptomyces sp. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15:38. doi: 10.3390/md15020038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae M., An J.S., Bae E.S., Oh J., Park S.H., Lim Y., Ban Y.H., Kwon Y., Cho J.-C., Yoon Y.J., et al. Donghaesulfins A and B, dimeric benz[a]anthracene thioethers from volcanic Island derived Streptomyces sp. Org. Lett. 2019;21:3635–3639. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kharel M.K., Pahari P., Shepherd M.D., Tibrewal N., Nybo S.E., Shaaban K.A., Rohr J. Angucyclines: Biosynthesis, mode-of-action, new natural products, and synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29:264–325. doi: 10.1039/C1NP00068C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu C., van der Heul H.U., Melnik A.V., Lübben J., Dorrestein P.C., Minaard A.J., Choi Y.H., van Wezel G.P. Lugdunomycin, an angucycline-derived molecule with unprecedented chemical architecture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:2809–2814. doi: 10.1002/anie.201814581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Z., Qin L., Wang Q., Ding W., Chen Z., Ma Z. Angucycline antibiotics and its derivatives from marine-derived actinomycete Streptomyces sp. A6H. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016;30:2551–2558. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1120730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L., Hou L., Li H., Li W. Antibiotic angucycline derivatives from the deepsea-derived Streptomyces lusitanus. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2019.1577835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma M., Rateb M.E., Teng Q., Yang D., Rudolf J.D., Zhu X., Huang Y., Zhao L.-X., Jiang Y., Li X., et al. Angucyclines and angucyclinones from Streptomyces sp. CB01913 featuring C-ring cleavage and expansion. J. Nat. Prod. 2015;78:2471–2480. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C., Song F., Guo H., Abdel-Mageed W.M., Bai H., Dai H., Liu X., Wang J., Zhang L. Isolation and characterization of LS1924A, a new analog of emycins. J. Antibiot. 2012;65:433–435. doi: 10.1038/ja.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang S., Yang X., Guo L., Xie Z., Yang Q., Gong S. Preparing Method and Application of Furamycins I and II. CN 108084126. China Patent. 2018 May 29;

- 26.Seco J.M., Quiñoá E., Riguera R. A practical guide for the assignment of the absolute configuration of alcohols, amines and carboxylic acids by NMR. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:2915–2925. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(01)00508-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bringmann G., Tasler S., Endress H., Kraus J., Messer K., Wohlfarth M., Lobin W. Murrastifoline-F: First total synthesis, atropo-enantiomer resolution, and stereoanalysis of an axially chiral N,C-coupled biaryl alkaloid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2703–2711. doi: 10.1021/ja003488c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.