Abstract

Background

Children treated for brain tumour (hereafter termed paediatric brain tumour survivors (PBTS)) often need extra support in school because of late-appearing side effects after their treatment. We explored how this group of children perform in the five practical and aesthetic (PRAEST) subjects: home and consumer studies, physical education and health, art, crafts and music.

Methods

In this nationwide population-based study of data from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry and Statistics Sweden, we included 475 children born between 1988 and 1996, diagnosed with a brain tumour before their 15th birthday. We compared their grades in PRAEST subjects with those of 2197 matched controls. We also investigated if there were any differences between girls and boys, children diagnosed at different ages, and children with high-grade or low-grade tumours.

Results

The odds for failing a subject were two to three times higher for girls treated for a brain tumour compared with their controls in all five PRAEST subjects, whereas there were no significant differences between the boys and their controls in any subject. PBTS had lower average grades from year 9 in all PRAEST subjects, and girls differed from their controls in all five subjects, while boys differed in physical education and health and music. PBTS treated for high-grade tumours neither did have significantly different average grades nor did they fail a subject to a significantly higher extent than PBTS treated for low-grade tumours.

Conclusions

Children treated for a brain tumour, especially girls, are at risk of lower average grades or failing PRAEST subjects. All children treated for brain tumour may need extra support as these subjects are important for their well-being and future skills.

Keywords: oncology, school health, epidemiology

Key messages.

What is known about the subject?

Children treated for brain tumour are at high risk of cognitive and other late effects that may affect their school performance.

Compared with controls, they often perform worse in theoretical school subjects, such as first or second language and mathematics.

Very little is known about their performance in practical and aesthetic (PRAEST) subjects.

What this study adds?

The odds to fail a PRAEST subject were two to three times higher for girls treated for brain tumour compared with controls.

Survivors, both girls and boys, had lower average grades from year 9 in all PRAEST subjects, compared with controls.

Children treated for brain tumour may need extra support in school, not only in theoretical subjects but also in PRAEST subjects.

Introduction

The survival rates of children treated for brain tumour (hereafter termed paediatric brain tumour survivors (PBTS)) have improved during the past decades to about 80%,1 and as a consequence, the numbers of PBTS attending school have increased. However, PBTS may face different kinds of difficulties in school, as they typically suffer from cognitive late effects, such as difficulties with verbal memory, language and attention,2 IQ decline over time,3 psychosocial difficulties, as well as depression or anxiety disorders.4 Particularly, children treated at a younger age and female PBTS appear to be at risk of academic difficulties.5–7 PBTS may also have limitations in physical performance affecting everyday life.8

In this study, we focused on PBTS performance in the practical and aesthetic (PRAEST) subjects, home and consumer studies (equivalent to the subject home economics), physical education and health, art, crafts and music (table 1). Previous studies of PBTS’s school performance have mainly focused on theoretical subjects, such as mother tongue, mathematics and foreign language.5–7 9 These studies have shown a greater risk of lower school grades for PBTS compared with controls. Only a few studies have included the subjects physical education7 9 10 and art/music,11 despite the fact that activities included in PRAEST subjects likely are valuable for essential skills and general well-being. For example, physical activity in the form of adventure-based training reduced fatigue and enhanced self-efficacy and quality of life among children treated for different types of cancer.12 Other studies have shown that active video gaming improved PBTS motor coordination and activities of daily living13 14 and that group training promoted white matter and hippocampal recovery and improved reaction time.15 The school subject home and consumer studies teaches basic daily life skills16 and thus prepares for independent living, which is of particular importance as many PBTS struggle with late effects affecting their daily life.17 18 A review of studies from Australia and the UK has shown that teaching in, and through, aesthetic subjects may have positive effects, such as promoting social interaction, better study results and increased self-confidence.19 20 Yet, the quality of the art programme is important. Aesthetic activities are also often used during hospital episodes to make it possible for patients to express feelings and fears and to offer coping strategies.21–23 In summary, PRAEST subjects are important for physical activity and practical skills, and may contribute to positive results in school and general well-being. However, we have found no studies that highlight PBTS’s performance in PRAEST subjects, despite the presumed importance and benefits.

Table 1.

Aims of practical and aesthetic subjects cited from the Swedish compulsory school syllabuses30

| Subject | Aim |

| Home and consumer studies | The subject provides experiences of social community, food and meals, housing and consumer economics, as well as opportunities to experience connections and pleasure in domestic work. The aim is to provide experiences and an understanding of the consequences of daily activities and habits in terms of economics, the environment, health and well-being (p15). |

| Physical education and health | The subject aims at developing pupils' physical, psychological and social abilities, as well as providing knowledge of the importance of lifestyle for health (p19). |

| Art | The subject aims at developing not only a knowledge of art, but also a knowledge of creating, analysing and communicating visually. It should develop desire, creativity and creative abilities, provide a general education in the area of the arts and lead to pupils acquiring their own standpoint in a reality characterised by huge flows of visual information (p7). |

| Crafts | The subject aims at creating an awareness of aesthetic values and developing an understanding of how choices over material, processing and construction influence a product's function and durability. The subject also aims at providing a knowledge of environmental and safety issues, and creating an awareness of the importance of resource management (p77). |

| Music | The subject /…/ aims at giving each pupil a desire and the opportunity of developing their musical skills and to experience that a knowledge of music is grounded in, liberates and strengthens their own identity, both socially, cognitively and emotionally (p35). |

Aim and research questions

Our aim was to explore the grades from spring term during the last year of compulsory school in Sweden (year 9) in the mandatory PRAEST school subjects for 475 PBTS and 2197 matched controls. Our research questions were

How many of the children treated for brain tumour fail the different PRAEST subjects home and consumer studies, physical education and health, art, crafts and music compared with controls?

Are there any differences between girls and boys, age at diagnosis or tumour grade (high or low grade) for the risk of failing a grade?

How do children treated for brain tumour perform in school, as judged by their average grades in the PRAEST subjects from the final year of compulsory school, compared with controls?

Are the PRAEST grades different between girls and boys, and do they vary depending on age at diagnosis or tumour grade (high or low grade)?

Methods

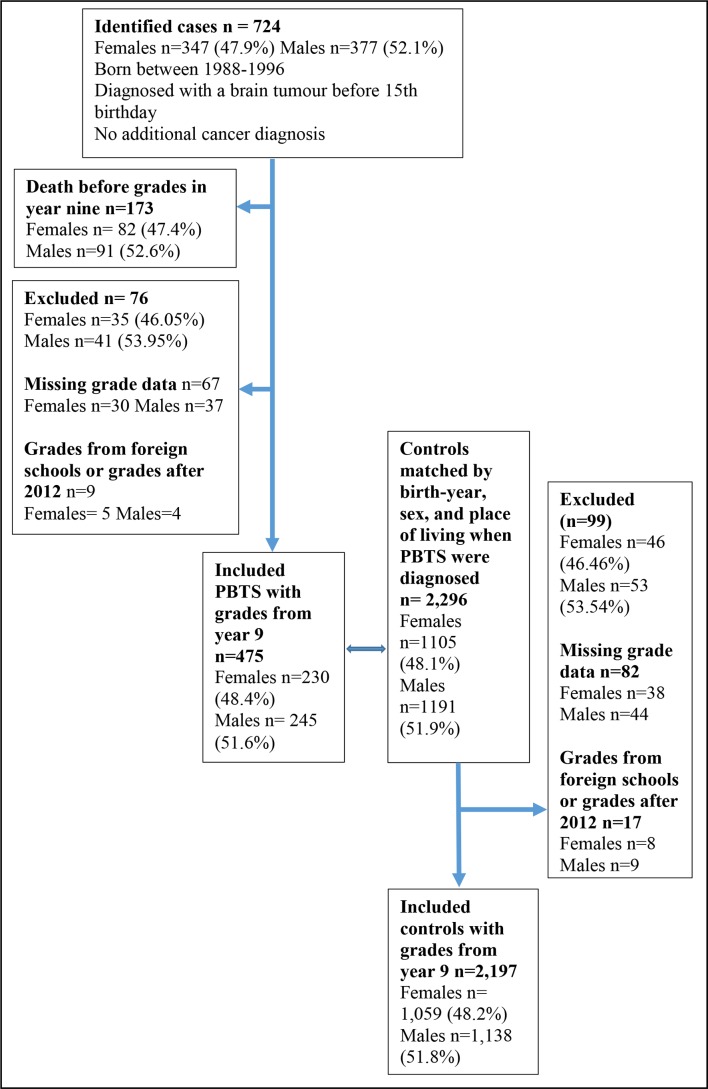

Children born in 1988–1996 and treated for brain tumour were identified from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry, and their personal identification numbers were sent from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry to Statistics Sweden and matched by Statistics Sweden24 to about five controls each (figure 1). PBTS were not eligible as controls and each control only appears for one PBTS. No PBTS or controls could be identified by the investigators. We have only handled coded key numbers and only Statistics Sweden has the key code. The Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry includes 94% of all children diagnosed with cancer in Sweden during the years 1984–2013.25 All parents or the children themselves have consented to being included in the registry, from which we also deducted information about the numbers of PBTS with high-grade (WHO III-IV) or low-grade (WHO I-II) tumours. Children with relapses were included, but not children with any other cancer forms. Of the PBTS, 97% were at least 1 year postdiagnosis when their school grades were abstracted. From Statistics Sweden we obtained information about grades, number of students with Swedish as their first or second language, and parents’ education (table 2).6

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria PBTS and controls. PBTS, paediatric brain tumour survivor.

Table 2.

Characteristics of PBTS (n=475) and controls (n=2197)6

| PBTS n=475 |

Controls n=2197 |

|

| Female | 230 (48.4%) | 1059 (48.2%) |

| Male | 245 (51.6%) | 1138 (51.8%) |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Female | ||

| 0–5 years | 82 (35.6%) | |

| 6–9 years | 51 (22.2%) | |

| 10–14 years | 97 (42.2%) | |

| Male | ||

| 0–5 years | 87 (35.5%) | |

| 6–9 years | 66 (26.9%) | |

| 10–14 years | 92 (37.6%) | |

| Tumour grade | ||

| Low | 383 (80.6%) | |

| High | 92 (19.4%) | |

| Mothers’ education | ||

| Low (school year 1–9 or less) | 36 (7.6%) | 219 (9.9%) |

| Medium (school year 10–12)* | 236 (49.7%) | 1091 (49.7%) |

| High (higher education) | 201 (42.3%) | 881 (40.1%) |

| No information about education | 2 (0.4%) | 6 (0.3%) |

| Fathers’ education | ||

| Low (school year 1–9 or less) | 82 (17.3%) | 353 (16.1%) |

| Medium (school year 10–12)* | 229 (48.2%) | 1156 (52.6%) |

| High (higher education) | 154 (32.4%) | 660 (30.0%) |

| No information about education | 10 (2.1%) | 28 (1.3%) |

| Swedish | ||

| As first language | 450 (94.7%) | 2101 (95.6%) |

| As second language | 25 (5.3%) | 96 (4.4%) |

*Until 1994, school year 10–12 could be 2 or 3 years.

PBTS, paediatric brain tumour survivor.

Children included in this study typically started a preschool class at age 6, school at age 7, and attended the full 9 years of compulsory school. In most schools, grades were given for the first time in the spring term at year 8. Until 2011, when a new grading system was introduced, the national Swedish grade system was based on a three-step scale, G=pass, worth 10 points, VG=pass with distinction, worth 15 points, and MVG=pass with special distinction, worth 20 points. This is the official way to enable calculation of average grades in Sweden.26 If the student failed a subject because of many absences or because they did not obtain the defined goals in the subject, 0 point was given. The five PRAEST subjects are mandatory and make up around one-third of all the subjects in the Swedish curriculum for the compulsory school years 1–9.16 As in Lönnerblad et al6, the age groups at diagnosis that we refer to follow the Swedish school system. Ages 0–5 comprise the years before compulsory school; ages 6–9 comprise 1 year in the so-called preschool class plus the early years of compulsory school (school years 1–3); and ages 10–14 comprise the middle and later years (school years 4–8) in compulsory school. The children graduate and get their final grades in their ninth year of compulsory school, typically at age 15 or 16, and these are the grades we analysed in the current study.

Statistical methods

We used IBM SPSS V.25 and V.26 and R V.3.6.0 for statistical analyses. P values below 5% were considered statistically significant. Non-significant results are marked n.s. For comparison between the background variables of cases and controls, we used Pearson’s χ2 test. ORs with 95% CIs for failing in the different subjects comparing PBTS and their controls were calculated using logistic regressions. To investigate whether the sex difference in the proportion failing differed between PBTS and their controls, we added an interaction term between sex and diagnosis to a logistic regression model with the failing in the different subjects as a dependent variable and sex and diagnosis as independent variables. To analyse the differences within the PBTS group for age at diagnosis (0–5 years, 6–9 years or 10–14 years) or tumour type (high or low grade), we used logistic regressions. We also adjusted the models for mothers’ and fathers’ education, respectively. Regarding average grade and differences between PBTS and their controls, we used an independent sample t-test. To investigate whether the sex difference in average grade differed between the PBTS and their controls, an interaction term between gender and diagnosis was added to a linear regression model, including average grade as a dependent variable and sex and diagnosis as independent variables. To analyse the differences within the PBTS group between, age at diagnosis (0–5 years, 6–9 years or 10–14 years) and tumour type (high or low grade), we used a linear regression. Average grade (including fail, pass, pass with distinction and pass with special distinction) in the different subjects was used as the dependent variable, and age groups and tumour type were used as the independent variables. This model was also adjusted for mothers’ and fathers’ education, respectively.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans for this research.

Results

Failing a subject

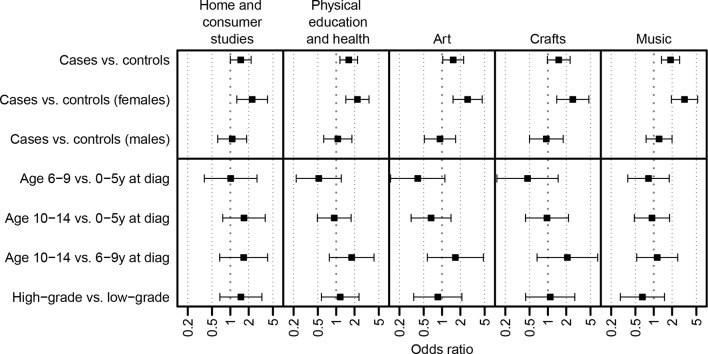

PBTS failed to a significantly higher extent the subjects music, art, and physical education and health compared with controls (table 3). In crafts and home and consumer studies, there were no statistically significant differences compared with controls. However, female PBTS had 2.23–3.20 times higher odds for failing a subject compared with girls in the control group in all PRAEST subjects, whereas the male PBTS did not significantly differ from their controls in any of the subjects Table 3. There were statistically significant interaction effects between sex and PBTS or controls on physical education and health, art, crafts and music. In these subjects, female PBTS failed to a significantly higher extent than male PBTS compared with the control group. We found no statistically significant interaction effect on home and consumer studies. Neither age at diagnosis nor tumour grade (high or low) had a significant effect on failing a grade for any of the PRAEST subjects for the PBTS (figure 2) and was still not significant when we adjusted for mothers’ and fathers’ education.

Table 3.

Number, percentage and ORs with 95% CIs and p values for failing the subjects for PBTS (n=475) versus controls (n=2197) and p values for interaction effect between sex and PBTS or control

| PBTS n (%) |

Controls n (%) |

OR (95% CI) | P value PBTS versus controls |

|

| Home and consumer studies | ||||

| All | 35 (7.4) | 112 (5.1) | 1.48 (1.0 to 2.19) | 0.051 n.s. |

| Female | 18 (7.8) | 38 (3.6) | 2.28 (1.28 to 4.07) | 0.005 |

| Male | 17 (6.9) | 74 (6.5) | 1.07 (0.62 to 1.85) | 0.803 n.s. |

| P value for interaction: 0.063 n.s. | ||||

| Physical education and health | ||||

| All | 51 (10.7) | 153 (7.0) | 1.61 (1.15 to 2.24) | 0.005 |

| Female | 33 (14.3) | 74 (7.0) | 2.23 (1.44 to 3.45) | 0.001 |

| Male | 18 (7.3) | 79 (6.9) | 1.06 (0.62 to 1.81) | 0.822 n.s. |

| P value for interaction: 0.035 | ||||

| Art | ||||

| All | 35 (7.4) | 109 (5.0) | 1.52 (1.03 to 2.26) | 0.036 |

| Female | 21 (9.1) | 39 (3.7) | 2.63 (1.52 to 4.56) | 0.001 |

| Male | 14 (5.7) | 70 (6.2) | 0.92 (0.51 to 1.67) | 0.795 n.s. |

| P value for interaction: 0.011 | ||||

| Crafts | ||||

| All | 29 (6.1) | 91 (4.1) | 1.51 (0.98 to 2.31) | 0.063 n.s. |

| Female | 17 (7.4) | 32 (3.0) | 2.56 (1.40 to 4.70) | 0.002 |

| Male | 12 (4.9) | 59 (5.2) | 0.94 (0.50 to 1.78) | 0.854 n.s. |

| P value for interaction: 0.026 | ||||

| Music | ||||

| All | 50 (10.5) | 129 (5.9) | 1.89 (1.34 to 2.66) | 0.001 |

| Female | 28 (12.2) | 44 (4.2) | 3.20 (1.94 to 5.26) | <0.001 |

| Male | 22 (9.0) | 85 (7.5) | 1.12 (0.75 to 2.0) | 0.423 n.s |

| P value for interaction: 0.007 | ||||

n.s., non-significant; PBTS, paediatric brain tumour survivor.

Figure 2.

ORs and 95% CIs for failing a subject. The lower part of the figure includes only PBTS. PBTS, paediatric brain tumour survivor.

Average grade

The average grades were significantly different between PBTS and controls in all five PRAEST subjects (table 4). Female PBTS had significantly lower average grades compared with their controls in all subjects, while male PBTS only had significantly lower average grades in physical education and health and music. The largest differences between PBTS and controls, including both girls and boys, was in physical education and health, and the smallest one was in art. There was a statistically significant interaction between sex and PBTS or control only in art. In art, girls had a statistically significant higher average grade than boys, and this difference was significantly larger in the control group. Neither age at diagnosis nor high-grade or low-grade tumour was a statistically significant factor for mean grade. Only in the model when we adjusted for fathers’ education, age at diagnosis was statistically significant (p=0.040) in the subject crafts, with children diagnosed at age 0–5 performing significantly worse than children treated at age 10–14.

Table 4.

Average grade and estimated difference with 95% CI for PBTS (n=475) versus controls (n=2197) and interaction effect between sex and PBTS or control

| Average grade (95% CI) |

Average grade (95% CI) |

Estimated difference (95% CI) |

P value | |

| PBTS | Controls | PBTS–Controls | PBTS–Controls | |

| Home and consumer studies | ||||

| All | 12.86 (12.40 to 13.32) | 13.78 (13.57 to 13.98) | −0.91 (−1.40 to −0.43) | <0.001 |

| Female | 13.91 (13.21 to 14.62) | 15.22 (14.94 to 15.50) | −1.31 (−1.99 to −0.63) | 0.001 |

| Male | 11.88 (11.31 to 12.45) | 12.43 (12.16 to 12.70) | −0.55 (−1.20 to −0.09) | 0.093 n.s |

| P value for interaction: 0.113 n.s. | ||||

| Physical education and health | ||||

| All | 11.74 (11.26 to 12.21) | 13.79 (13.57 to 14.01) | −2.05 (−2.58 to −1.53) | <0.001 |

| Female | 11.13 (10.40 to 11.86) | 13.45 (13.14 to 13.76) | −2.32 (−3.07 to −1.57) | <0.001 |

| Male | 12.31 (11.70 to 12.92) | 14.10 (13.79 to 14.42) | −1.80 (−2.53 to −1.06) | <0.001 |

| P value for interaction: 0.328 n.s. | ||||

| Art | ||||

| All | 12.53 (12.08 to 12.98) | 13.37 (13.17 to 13.57) | −0.85 (−1.32 to −0.37) | <0.001 |

| Female | 13.50 (12.77 to 14.23) | 14.84 (14.57 to 15.12) | −1.34 (−2.02 to −0.66) | 0.001 |

| Male | 11.61 (11.09 to 12.13) | 12.00 (11.74 to 12.26) | −0.39 (−1.00 to −0.22) | 0.209 n.s. |

| P value for interaction: 0.040 | ||||

| Crafts | ||||

| All | 12.80 (12.36 to 13.24) | 13.67 (13.48 to 13.86) | −0.87 (−1.32 to −0.41) | <0.001 |

| Female | 13.20 (12.52 to 13.88) | 14.44 (14.18 to 14.70) | −1.24 (−1.89 to −0.60) | 0.001 |

| Male | 12.43 (11.86 to 13.00) | 12.95 (12.68 to 13.21) | −0.52 (−1.15 to −0.11) | 0.106 n.s. |

| P value for interaction: 0.116 n.s. | ||||

| Music | ||||

| All | 11.88 (11.41 to 12.36) | 13.17 (12.97 to 13.38) | −1.29 (−1.78 to −0.80) | <0.001 |

| Female | 12.35 (11.61 to 13.09) | 14.12 (13.84 to 14.40) | −1.77 (−2.46 to −1.08) | <0.001 |

| Male | 11.45 (10.85 to 12.05) | 12.29 (12.00 to 12.58) | −0.84 (−1.53 to −0.16) | 0.015 |

| P value for interaction: 0.060 n.s. | ||||

n.s., non-significant; PBTS, paediatric brain tumour survivor.

Discussion

Statement of the principal findings

This nationwide, population-based study revealed that the odds for failing a PRAEST subject were two to three times higher for female PBTS compared with their controls for all five subjects, whereas there were no significant differences between male PBTS and their controls in any subject. PBTS also had significantly lower average grades in all five PRAEST subjects compared with their controls. When we compared the average grades of female and male PBTS with their controls, girls differed from their controls in all subjects, while boys only differed in physical education and health and music. Age at diagnosis was not a significant factor in any subject for failing. For average grade, age at diagnosis was significant only in one subject, crafts, when we adjusted for the fathers’ education, but not in the unadjusted models or when we adjusted for the mothers’ education. High-grade tumours are usually treated with cranial radiotherapy, a modality known to cause cognitive and other deficits, but we did not find any significant impact of tumour grade on average grades or failing any of the subjects.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The major strength of this study is that it is a nationwide, population-based study with grades from almost all children in Sweden born 1988–1996 and diagnosed with a brain tumour before the age of 15. We have analysed how this group of PBTS performed in the five different PRAEST subjects compared with their controls, and this is the only study of its kind. To address the issue of patients still undergoing treatment, we performed a sensitivity analysis, excluding all patients less than 2 years after diagnosis, and this did not have any appreciable impact on the results. We selected 2 years after diagnosis since very few patients, only those on second-line or third-line treatments, would still be on active treatment. We consider that the main limitations are that we have no information about why the included children failed a subject, or if any adaptations in the course work were made for the PBTS to facilitate their participation. In addition, as passing the PRAEST subjects is not required to qualify for postsecondary school in Sweden, we do not know if PBTS may have dropped any of these subjects voluntarily in favour of the theoretical subjects Swedish, mathematics or English, which are required for qualification. However, as all PRAEST subjects are mandatory, it is not possible for pupils to drop any subject unless the school has given permission to do so. Another limitation is the unknown reasons for missing data, as there are slightly more missing registry data from the PBTS than from the controls. This is discussed in more detail in Lönnerblad et al.

Discussing important differences in results

Our results regarding physical activity and health grades show that PBTS had a lower average grade and failed to a higher extent than controls in this subject, which is in line with previous studies by Lähteenmäki et al,7 Ahomäki et al9 and Park et al.10 In our study, both girls and boys differed more from their controls in physical activity and health than in the other PRAEST subjects. Female PBTS failed this subject more frequently (14.3% vs 7.0% in the control group). The study by Yilmaz et al11 of children treated for different kinds of cancers showed that controls performed better in the two subjects denoted Sports and art/music. In our study, music revealed the second largest difference between PBTS and controls for both girls and boys, and was the second most common subject where female PBTS failed. Both the subjects music and physical activity and health can be very noisy, which, at least partly, may explain why these two subjects are most affected, as auditory deficits and difficulties such as tinnitus are not unusual.27 Another explanation could be that motor skills as well as muscle strength may be affected.8 28 29 This could possibly affect the results in all the PRAEST subjects. As reported in our previous study (Lönnerblad et al), age at diagnosis was a significant factor for a lower average grade in all three theoretical subjects, mathematics, Swedish and English. However, in the PRAEST subjects, age at diagnosis does not seem to be important for average grade or failing. We can only speculate about the reasons of this. One explanation could be that it is easier to find strategies to compensate for cognitive and other late effects in the PRAEST subjects compared with the theoretical subjects; another explanation could be that it is easier to catch up in the PRAEST subjects. A third explanation is that there are no standardised tests in these subjects that the teacher have to consider when grading the children. Similarly, treatment for a high-grade or a low-grade tumour did not have a statistically significant effect on grades in the risk of failing a PRAEST subject. The same was true also for mathematics, Swedish and English (Lönnerblad et al), contrary to our expectations.

Possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policy makers

The present study provides novel, important information, demonstrating that PBTS perform worse also in PRAEST subjects compared with controls, not only in theoretical subjects, which is known from previous studies. Given the benefits of the PRAEST subjects, acquiring skills for activities of daily living as well as promoting health and general well-being, the PBTS’ higher rate of failing and lower average grades compared with controls is problematic. Adaptations and modifications should be considered to encourage higher participation and better performance, particularly for girls. Clinicians, school staff and relatives to PBTS, along with policy makers, should all be included in the discussion about what can be done to ameliorate the negative effects of poor performance in school for PBTS, not only in theoretical but also in the PRAEST subjects.

Unanswered questions and future research

Girls were two or three times more likely to fail the PRAEST subjects compared with their controls, while this was not seen in boys. However, future larger studies would be interesting as they could possibly detect a difference also between boys, as the difference between male PBTS and controls is much smaller. PRAEST subjects may have a lower status than the more theoretical subjects,22 and it is conceivable that girls more often, for strategic reasons, drop the PRAEST subjects in favour of the theoretical subjects Swedish, mathematics and English, since failing the latter ones precludes qualification for school years 10–12 (upper secondary school/high school). The reasons why PRAEST subjects are dropped or why female PBTS fail these subjects to a much higher extent than male PBTS should be further investigated. Nevertheless, it is important that both girls and boys are offered appropriate support and special educational efforts to fully benefit from the PRAEST subjects. Future research should look closer into how the different subjects could be adapted to enable the PBTS to participate in these subjects to a higher extent and further develop their PRAEST skills.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ida Hed Myrberg for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since it was published online. The article title has been updated.

Contributors: ML and EB conceived the study. ML collected and analysed the data and wrote the first draft. ML, IvH, KB and EB interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, Stockholm County Council (ALF projects), Swedish Childhood Cancer Fund, Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation of Stockholm, Märta and Gunnar V. Philipson Foundation, Swedish Cancer Foundation, Department of Special Education Stockholm University, Filéenska Foundation, Rhodin Foundation, Swedish Brain Foundation and Kinander Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: The data that support the findings of this study are available from Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry and Statistics Sweden. Ethical approval for this study was given by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (number 2017/995-31/5). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry and Statistics Sweden. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

References

- 1.Gustafsson G, Kogner P, Heyman M. Childhood Cancer Incidence and Survival in Sweden 1984-2010, 2013. Available: http://www.forskasverige.se/wp-content/uploads/ChildhoodCancerIncidenceandSurvivalinSweden1984_2010.pdf

- 2.Robinson KE, Kuttesch JF, Champion JE, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of pediatric brain tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010;55:525–31. 10.1002/pbc.22568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulhern RK, Merchant TE, Gajjar A, et al. Late neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of brain tumours in childhood. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:399–408. 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01507-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitsko MJ, Cohen D, Dillon R, et al. Psychosocial late effects in pediatric cancer survivors: a report from the children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:337–43. 10.1002/pbc.25773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen KK, Duun-Henriksen AK, Frederiksen MH, et al. Ninth grade school performance in Danish childhood cancer survivors. Br J Cancer 2017;116:398–404. 10.1038/bjc.2016.438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lönnerblad M, Van't Hooft I, Blomgren K, et al. A nationwide, population-based study of school grades, delayed graduation, and qualification for school years 10-12, in children with brain tumors in Sweden. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2020;67:e28014 10.1002/pbc.28014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lähteenmäki PM, Harila-Saari A, Pukkala EI, et al. Scholastic achievements of children with brain tumors at the end of comprehensive education: a nationwide, register-based study. Neurology 2007;69:296–305. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265816.44697.b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ness KK, Morris EB, Nolan VG, et al. Physical performance limitations among adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Cancer 2010;116:3034–44. 10.1002/cncr.25051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahomäki R, Harila-Saari A, Matomäki J, et al. Non-graduation after comprehensive school, and early retirement but not unemployment are prominent in childhood cancer survivors-a Finnish registry-based study. J Cancer Surviv 2017;11:284–94. 10.1007/s11764-016-0574-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park M, Park HJ, Lee JM, et al. School performance of childhood cancer survivors in Korea: a multi-institutional study on behalf of the Korean Society of pediatric hematology and oncology. Psychooncology 2018;27:2257–64. 10.1002/pon.4819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yilmaz MC, Sari HY, Cetingul N, et al. Determination of school-related problems in children treated for cancer. J Sch Nurs 2014;30:376–84. 10.1177/1059840513506942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li WHC, Ho KY, Lam KKW, et al. Adventure-based training to promote physical activity and reduce fatigue among childhood cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;83:65–74. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabel M, Sjölund A, Broeren J, et al. Active video gaming improves body coordination in survivors of childhood brain tumours. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:2073–84. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1116619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabel M, Sjölund A, Broeren J, et al. Effects of physically active video gaming on cognition and activities of daily living in childhood brain tumor survivors: a randomized pilot study. Neurooncol Pract 2017;4:npw020 10.1093/nop/npw020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riggs L, Piscione J, Laughlin S, et al. Exercise training for neural recovery in a restricted sample of pediatric brain tumor survivors: a controlled clinical trial with crossover of training versus no training. Neuro Oncol 2016;4:now177 10.1093/neuonc/now177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swedish National Agency for Education Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the leisure-time centre, 2011. Available: https://www.mah.se/upload/Nationella%20%c3%a4mnesprovet/Lgr11%20English.pdf [Accessed 11 Nov 2019].

- 17.Kunin-Batson A, Kadan-Lottick N, Zhu L, et al. Predictors of independent living status in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer Survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57:1197–203. 10.1002/pbc.22982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunn ME, Mört S, Arola M, et al. Quality of life and late-effects among childhood brain tumor survivors: a mixed method analysis. Psychooncology 2016;25:677–83. 10.1002/pon.3995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts Health and Wellbeing Creative health: the arts for health and wellbeing, 2017. Available: https://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017_-_Second_Edition.pdf [Accessed November 12, 2019].

- 20.Swedish National Agency for Education Undervisning och lärande genom sinne, tanke och känsla, 2017. Available: https://larportalen.skolverket.se/LarportalenAPI/api-v2/document/path/larportalen/material/inriktningar/4-specialpedagogik/Grundskola/101_Inkludering_och_skolans_praktik/del_08/Material/Flik/Del_08_MomentA/Artiklar/SP2_1-9_08_01_Sinne.docx [Accessed November 11, 2019].

- 21.Uggla L, Bonde L-O, Hammar U, et al. Music therapy supported the health-related quality of life for children undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplants. Acta Paediatr 2018;107:1986–94. 10.1111/apa.14515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucquet B, Leung M. Music therapy services in pediatric oncology: a national clinical practice review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2014;31:327–38. 10.1177/1043454214533424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane MR. Arts in health care: a new paradigm for holistic nursing practice. J Holist Nurs 2006;24:70–5. 10.1177/0898010105282465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Sweden About statistics Sweden. Statistiska Centralbyrån, 2018. Available: http://www.scb.se/en/About-us/ [Accessed December 12, 2018].

- 25.National Board of Health and Welfare Täckningsgrader 2015 -Jämförelser mellan nationella kvalitetsregister och hälsodataregistren. Socialstyrelsen, 2015. Available: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/sok/?q=barncancerregistret [Accessed 15 Nov 2019].

- 26.Swedish National Agency for Education Swedish grades. Available: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.47fb451e167211613ef398/1542791697007/swedishgrades_bilaga.pdf [Accessed 8 Jan 2020].

- 27.Weiss A, Sommer G, Kasteler R, et al. Long-Term auditory complications after childhood cancer: a report from the Swiss childhood cancer Survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:364–73. 10.1002/pbc.26212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer Survivor study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 2008;17:435–46. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rueegg CS, Michel G, Wengenroth L, et al. Physical performance limitations in adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer and their siblings. PLoS One 2012;7:e47944 10.1371/journal.pone.0047944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swedish National Agency for Education Syllabuses 2000: Compulsory School. Stockholm: FRITZES, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.