Abstract

Introduction

Gout is a painful form of inflammatory arthritis associated with several comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular disease. Cherries, which are rich in anti-inflammatory and antioxidative bioactive compounds, are proposed to be efficacious in preventing and treating gout, but recommendations to patients are conflicting. Cherry consumption has been demonstrated to lower serum urate levels and inflammation in several small studies. One observational case cross-over study reported that cherry consumption was associated with reduced risk of recurrent gout attacks. This preliminary evidence requires substantiation. The proposed randomised clinical trial aims to test the effect of consumption of tart cherry juice on risk of gout attacks.

Methods and analysis

This 12-month, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial will recruit 120 individuals (aged 18–80 years) with a clinical diagnosis of gout who have self-reported a gout flare in the previous year. Participants will be randomly assigned to an intervention group, which will receive Montmorency tart cherry juice daily for a 12-month period, or a corresponding placebo group, which will receive a cherry-flavoured placebo drink. The primary study outcome is change in frequency of self-reported gout attacks. Secondary outcome measures include attack intensity, serum urate concentration, fractional excretion of uric acid, biomarkers of inflammation, blood lipids and other markers of cardiovascular risk. Other secondary outcome measures will be changes in physical activity and functional status. Statistical analysis will be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been granted ethical approval by the National Research Ethics Service, Yorkshire and The Humber—Leeds West Research Ethics Committee (ref: 18/SW/0262). Results of the trial will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

Keywords: rheumatology, gout, tart cherry, nutrition & dietetics, musculoskeletal disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of tart cherry juice to reduce risk of recurrent gout flares.

Primary and secondary outcomes are central to treatment of gout and its comorbidities.

This study will investigate mechanisms whereby tart cherry juice may reduce risk of recurrent gout flares and comorbidities.

The study design addresses the temporal risk of gout flares by assessing patients over a 12-month period and retention of participants may be challenging.

Introduction

Gout is a debilitating and common type of inflammatory arthritis exerting a significant health burden.1 2 The proportion of people afflicted with gout in the UK is substantial; around 3% of adults were affected in 2012, representing approximately 1.9 million people.3 Men are typically at greater risk of developing gout than women and risk increases with age for both genders.3 Gout is associated with numerous comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity and hypertension.3–5

Acute recurrent attacks of arthritis, also known as flares, are a defining feature of gout.6 The underlying cause is a build-up of monosodium urate crystalline deposits in the joints, particularly those of the lower limbs causing acute pain, redness and inflammation.7 8 Gout attacks are intermittent and may last from several days to up to several weeks. Usually only one joint is affected. Sustained hyperuricaemia, which most commonly occurs secondary to reduced fractional uric acid clearance, is recognised as the most important risk factor for gout.9 10 Consumption of purine-rich or fructose-rich food and drink, including seafood, red meat, beer and sugar-sweetened beverages have been associated with increased uric acid levels and risk of gout flares.11–16

Early case reports from the 1950s suggested that consumption of cherries had a role to play in alleviating gouty pain and inflammation.17 More recently, cherries and cherry products have been shown to acutely lower serum urate after consumption in healthy people, while a daily supplement of cherry juice was associated with lower serum urate in a placebo-controlled cross-over study of men and women who are overweight or have obesity.18–20 It is unclear which bioactive component in cherries may be responsible for the effect; Bell et al proposed that anthocyanins and/or other phenolic compounds present in cherry may be important.18

There are very few studies in gout patients. In a case cross-over study of 633 gout sufferers, cherry consumption was associated with a 35% lower risk of gout flares.21 This study was predicated on an acute temporal relationship between cherry consumption and likelihood of gout flares and did not evaluate the habitual effect of cherry consumption. Furthermore being observational in design, causality cannot be assumed.21 While there have been two intervention studies that have addressed the potential for cherry to reduce risk of gout, these were both feasibility studies with limited sample size, lack of an appropriate placebo and within-group statistical comparison.22 23

In addition to lowering serum urate, cherry consumption may be of benefit in gout prophylaxis because cherries contain a variety of polyphenolic compounds with anti-inflammatory properties. These compounds may ameliorate the inflammatory response induced by monosodium urate crystals.18 21 Indeed, cherry consumption has been shown to lower a recognised biomarker of inflammation C-reactive protein (CRP) in both healthy people18 24–26 and those with arthritis.27 28

Despite the limited scientific evidence base, leading medical societies and charities (for example, British Society for Rheumatology, European League against Rheumatism, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, Arthritis Research UK, Mayo Clinic, UK Gout Society) endorse cherry consumption as a therapeutic aid for gout.1 29–33 Contrastingly, the Food and Drug Administration in the USA has warned cherry juice growers and processers against making preventive disease claims.34 A content analysis of US and UK newspapers reported that 25% of articles discussing dietary management of gout advised cherry consumption.35 Notably, the UK’s National Health Service health information website dismissed newspaper claims that advocated cherry consumption for gout.36 There is a clear need for definitive evidence from a randomised controlled trial (RCT).

The proposed study is a 12-month RCT designed to provide superior evidence as to whether tart cherries are a useful adjuvant therapy for treatment of gout. The study will also elucidate possible mechanisms of effect through the measurement of serum urate, fractional urinary urate excretion, biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress. As participants are likely to be at increased risk of CVD, secondary study outcomes will be measures of arterial stiffness and blood lipids.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of a daily intervention of tart cherry juice over a 12-month period compared with a placebo drink on risk of gout attacks.

The primary objective of this trial is to assess if a daily supplement of tart cherry juice influences the frequency of gout attacks over 12 months relative to a daily supplement of a placebo drink.

Its secondary objectives are to:

Assess if tart cherry juice supplementation impacts on risk factors for CVD.

Identify the effects of tart cherry juice supplementation on putative biological mediators of risk of gout.

Hypotheses

In patients diagnosed with gout, a dietary intervention of a daily tart cherry concentrate drink for a 12-month period will reduce the frequency of gout flares compared with a placebo drink.

In patients diagnosed with gout, a dietary intervention of a daily tart cherry concentrate drink for a 12-month period will lower markers of cardiovascular risk (arterial stiffness, blood pressure (BP) and blood lipids) compared with a placebo drink.

Methods and analysis

Described according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines.37

Study design and setting

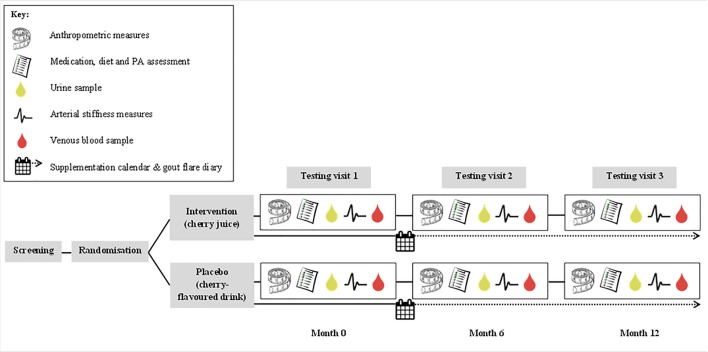

The study is a 12-month, double-blind, two-armed, parallel RCT performed in adults aged 18 to 80 years, with an existing clinical diagnosis of gout and who have reported at least one gout flare in the last 12 months. The intervention group will receive a daily supplement of tart cherry juice and the placebo group will receive a cherry-flavoured drink. The primary outcome measure will be between-group difference in the frequency of gout flares from baseline to 12 months. Secondary outcome measures will be between-group differences in gout flare pain, serum urate concentration, fractional excretion of uric acid, blood lipids and recognised markers of inflammation (CRP, interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha), oxidative stress and vascular function (BP, arterial stiffness). Changes in physical activity, perceived health and pain will also be secondary outcomes. Non-efficacy outcomes will include dietary intake measures, for example total energy, total sugars and consumption of gout trigger foods. Each participant will be enrolled onto the study for 12 months; physical and vascular measurements and fasted blood and 24 hours urine samples will be collected at 0, 6 and 12 months. These measurements will be made at Sheffield Hallam University's Food and Nutrition Research Laboratories in Sheffield, UK. Laboratory visits will be postponed for any participant that is experiencing a gout flare until after the flare has resolved. An overview of the study design and timeline is given in figure 1. The study opened recruitment in June 2019 and is ongoing.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study. PA; physical activity.

Participants and recruitment

Participants will mainly be recruited from primary care practices in the English city of Sheffield and surrounding areas. The Clinical Research Network of Yorkshire and Humber, which provides localised infrastructure to support delivery of research, will select practices to act as participant identification centres (PICs). At each PIC, computerised patient records will be searched to identify eligible individuals that have a clinical diagnosis of gout. Diagnosis is typically based on clinical examination, assessment of reported symptoms and elevated serum urate. A general practitioner will screen the list of patients generated from this search for suitability to participate (e.g. people who are frail or suffer from dementia would not be recruited). People who are eligible will be sent an invitation to participate; interested individuals will be encouraged to contact the research team for further study information. Such participants will be invited to attend an information, screening and enrolment meeting at Sheffield Hallam University. Written informed consent will be obtained from those willing to take part by the study coordinator (KL).

Recruitment from PICs will be augmented by poster advertising at local primary care practices and across the university campus, advertising on the UK Gout Society website and at local large-scale workplaces. Participants' general practitioner will be contacted to verify their eligibility.

Inclusion criteria

Aged between 18 and 80 years.

Clinical diagnosis of gout.

At least one self-reported gout flare with a pain score >3 (on a 0–10 numerical rating scale) in the past 12 months.

Participant is able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Allergy to cherries.

Habitual consumption of cherries and/or cherry products.

Severe renal impairment (glomerular filtration rate <30 mg/L).

Type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Recruiting practitioner deems that the patient is unsuitable to participate (frailty, dementia and terminal medical conditions).

Dietary intervention

Participants will be provided monthly with either Montmorency tart cherry 68 Brix concentrate (King Orchards, Michigan, USA) or a low-phenol, cherry-flavoured placebo concentrate. Both drinks will be diluted with water by participants before consumption (30 mL of concentrate with 220 mL of water, totalling 250 mL/day). Graduated cups with clear markings indicating required volumes of concentrate and water will be provided to participants. Participants will be advised to consume their drink with breakfast and to keep the concentrate refrigerated. Consumption will be recorded daily on a calendar. Advice will be given to maintain usual dietary habits throughout the course of the intervention and to avoid cherry consumption.

Each daily serving of tart cherry has been reported to provide: 80 kcal, 20 g carbohydrate, 870 mg phenolics and 14 mg of anthocyanins.20 Each serving of the placebo drink will provide: 2.9 kcal, 0.3 g carbohydrate, 13 mg phenolics and 0.2 mg anthocyanins. The placebo drink has been constituted to have similar colour, taste and tartness as the cherry concentrate through the addition of blue and red food colourings, red and black cherry flavourings and citric acid to a low-fruit cordial (summer fruits flavour). It was not possible to match the drinks for energy content because the addition of sugars to the placebo drink would have jeopardised its shelf life. Furthermore, the addition of sucrose (comprising 50% fructose) has the potential to raise serum urate.38

Data collection

Laboratory visit data

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measures of height and weight will be used to calculate body mass index (weight (kg)/height2 (m2)). Height without shoes will be measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Seca, Hamburg, Germany). Weight will be measured in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg using calibrated weighing scales (Seca 899, Hamburg, Germany).

Fasting blood sample

Fasted venous blood samples will be collected. These will be analysed for: serum inflammatory markers (CRP, interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha), serum urate and blood lipids (total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triacylglycerol). Oxidative DNA damage and antioxidant status will also be measured in lymphocytes using the Comet assay (single-cell electrophoresis).

Urine samples

Prior to each visit, participants will carry out a 24 hours urine collection. These samples will be used to calculate 24-hour urinary uric acid excretion. A further spot urine sample will be collected alongside the fasting blood sample to calculate fractional excretion of uric acid.

Arterial stiffness

A Vicorder device (SMT Medical, Germany) will be used to measure brachial BP, central BP, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity and augmentation index.

Medication use and functional status

Medication use (contemporary and historical) will be recorded at baseline and monitored closely throughout the study. This record includes both prescribed and over-the-counter medication. Any changes to medication use, for example, dosing changes or new prescriptions, will be recorded in the participant’s medication log. Dietary supplement use will also be recorded at baseline, 6 and 12 months. Assessment of functional status covering pain, interference with daily activities and perceived health will be collected through interview using questions from a validated scale.39

Self-reported data

Gout flares

Information on gout flares experienced by participants in the preceding 12 months will be collected at baseline. This information covers frequency, duration, location, pain severity (0–10 numerical rating scale) and treatment. During the 12-month supplementation period, participants will keep a diary to record all instances of gouty pain, again covering duration, location, pain severity and treatment. A gout flare will be recorded if self-reported pain at rest is >3.40

Assessment of diet and physical activity levels

Participants will complete a 4-day food diary using estimated household measures and record physical activity in a diary over a 4-day period in the week preceding each laboratory visit.

Compliance

A daily calendar will be completed to record adherence to the intervention. Routine monthly telephone contact and face-to-face contact when delivering the drinks will be used to encourage compliance.

Retention

Participants may withdraw from the study at any time without giving any reason. Reasons for discontinuing the study will be recorded. Participants who decide to discontinue the intervention will be invited to return for follow-up visits to assess outcome measures.

Adverse events

All adverse events (AEs) will be recorded and reported, where applicable, following Good Clinical Practice and Health Research Authority guidelines. Participants will be advised to report all serious or non-serious AEs to the research team; these data will be recorded. Additionally, the incidence of adverse events will be logged at laboratory visits and via telephone contact.

Data management

The collection and storage of data will adhere to the standard requirements of the EU General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679. Data will be entered onto electronic spreadsheets, which will be stored on a secure university server. All data will be treated confidentially and anonymised for evaluation. Hard copies of data and documents will be kept in a locked and secure cabinet for the duration of the study. Following completion of the study, data will be transferred to Sheffield Hallam University's Research Data Archive, where it will be kept for 10 years. Hard copies will be disposed of confidentially and electronic data deleted after this period of time.

Randomisation, allocation and blinding

All consenting participants will be block randomised (block size 4) in a 1:1 allocation to either a tart cherry juice group or a placebo cherry-flavoured drink group with stratification by sex and smoking status. Allocation sequence will be generated using a computer random number generator by an investigator not involved in participant enrolment and data collection (AL) and concealed from research personnel until the completion of the trial. The study coordinator (KL) who will be responsible for participant enrolment, distribution of intervention drinks and data collection will be blinded to treatment allocation until results have been analysed. Drinks will be provided to participants in identical bottles and labelled with participant identification number only to ensure that both study coordinator and participants are blinded to drink allocation throughout the study.

Sample size

The power calculation was based on the potential impact of tart cherry supplementation on the primary outcome measure. Using data on gout occurrence in UK patients, the chance of a recurrence of at least one gout flare over a 12-month period is 11%.41 It is predicted that cherry juice treatment will reduce this recurrence to one quarter of the rate of the actual recurrence (from 11% to 2.7%). Based on these data, it is estimated that 94 participants would provide 95% power at a significance level of 0.05. A sample of 120 participants will allow for an attrition rate of approximately 20%.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables will be presented as mean and CIs. Statistical significance will be set at p<0.05. Descriptive analysis of all baseline variables will be conducted to compare the two groups. All analyses will be performed using intention-to-treat analysis; all randomised participants will be included in the final analysis as far as data collected will allow. Independent generalised mixed model analyses of variance will be performed to test for changes in frequency of flares from baseline to 12 months between treatments (cherry vs placebo); baseline, 6 months and 12 months times will be used for secondary outcomes. Analysis will be performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 for Windows.

Patient and public involvement

Gout patients were not directly involved in development of the research question or study design. We consulted with retired people from a local church group (Christ Church Fulwood, Sheffield, England) as to their understanding of written participant information and questionnaires. This group also provided feedback on the acceptability of the schedule of visits, study measures and intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Any protocol modifications will be sent for review by the research ethics committee and will be amended at the trial registry. Participants will be sent a summary of the trial findings when all data have been analysed. Dissemination of the study findings of this study will be through publication in a leading peer-reviewed journal and presentation at national and international conferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the input of Dr Tim Tait, Consultant Rheumatologist, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Lincoln, England for his guidance about clinical aspects of the study protocol. We are grateful to Dr Caroline Mitchell and Dr Helen Twohig from the Academic Unit of Primary Medical Care, University of Sheffield for their helpful advice.

Footnotes

Contributors: AL and MEB designed the study and secured the funding. KL prepared study documents and coordinated the HRA and ethics applications. MEB and AL are joint principal investigators. KL is the study coordinator and coinvestigator. KL drafted the manuscript for publication, with input from AL, JMR and MEB. JMR advised on the study design, power calculation and statistical analysis.

Funding: The sponsor of this research is Sheffield Hallam University, UK. This work is supported by the Cherry Marketing Institute (grant no: AA4736173), Michigan, USA. Patient recruitment to the study is supported by Yorkshire and Humber National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network.

Competing interests: MEB and AL are the joint recipients of a research grant from the CMI, Michigan, USA.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol (V.2.0, January 2019) was reviewed and approved by Yorkshire and The Humber Leeds West REC (Ref: 18/SW/0262).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hui M, Carr A, Cameron S, et al. . The British Society for rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology 2017;56:e1–20. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, et al. . Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:649–62. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, et al. . Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:661–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stack AG, Hanley A, Casserly LF, et al. . Independent and conjoint associations of gout and hyperuricaemia with total and cardiovascular mortality. QJM 2013;106:647–58. 10.1093/qjmed/hct083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, et al. . Comorbidities in patients with gout prior to and following diagnosis: case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:210–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roddy E, Doherty M. Gout. epidemiology of gout. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:1–11. 10.1186/ar3199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet 2016;388:2039–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00346-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roddy E. Revisiting the pathogenesis of podagra: why does gout target the foot? J Foot Ankle Res 2011;4:1–6. 10.1186/1757-1146-4-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terkeltaub R, Bushinsky DA, Becker MA. Recent developments in our understanding of the renal basis of hyperuricemia and the development of novel antihyperuricemic therapeutics. Arthritis Res Ther 2006;8:S4–9. 10.1186/ar1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abhishek A, Doherty M. Education and non-pharmacological approaches for gout. Rheumatology 2018;57:i51–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. . Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet 2004;363:1277–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16000-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi JWJ, Ford ES, Gao X, et al. . Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the third National health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:109–16. 10.1002/art.23245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Major TJ, Topless RK, Dalbeth N, et al. . Evaluation of the diet wide contribution to serum urate levels: meta-analysis of population based cohorts. BMJ 2018;363:1–10. 10.1136/bmj.k3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Jiang X, Wu W, et al. . A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of gout. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:1641–8. 10.1007/s10067-013-2319-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang DD, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, et al. . The effects of fructose intake on serum uric acid vary among controlled dietary trials. J Nutr 2012;142:916–23. 10.3945/jn.111.151951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White SJ, Carran EL, Reynolds AN, et al. . The effects of apples and apple juice on acute plasma uric acid concentration: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2018;107:165–72. 10.1093/ajcn/nqx059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blau LW. Cherry diet control for gout and arthritis. Tex Rep Biol Med 1950;8:309–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell PG, Gaze DC, Davison GW, et al. . Montmorency tart cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) concentrate lowers uric acid, independent of plasma cyanidin-3-O-glucosiderutinoside. J Funct Foods 2014;11:82–90. 10.1016/j.jff.2014.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob RA, Spinozzi GM, Simon VA, et al. . Consumption of cherries lowers plasma urate in healthy women. J Nutr 2003;133:1826–9. 10.1093/jn/133.6.1826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin KR, Coles KM. Consumption of 100% tart cherry juice reduces serum urate in overweight and obese adults. Curr Dev Nutr 2019;3:1–9. 10.1093/cdn/nzz011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Neogi T, Chen C, et al. . Cherry consumption and decreased risk of recurrent gout attacks. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:4004–11. 10.1002/art.34677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlesinger N, Rabinowitz R, Schlesinger M. Pilot studies of cherry juice concentrate for gout flare prophylaxis. J Arthritis 2012;01:1–5. 10.4172/2167-7921.1000101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh JA, Green C, Morgan S, et al. . A randomized Internet-based pilot feasibility and planning study of cherry extract and diet modification in gout. J Clin Rheumatol 2019. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001004. [Epub ahead of print: 23 Jan 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelley DS, Rasooly R, Jacob RA, et al. . Consumption of Bing sweet cherries lowers circulating concentrations of inflammation markers in healthy men and women. J Nutr 2006;136:981–6. 10.1093/jn/136.4.981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley DS, Adkins Y, Reddy A, et al. . Sweet bing cherries lower circulating concentrations of markers for chronic inflammatory diseases in healthy humans. J Nutr 2013;143:340–4. 10.3945/jn.112.171371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chai SC, Davis K, Zhang Z, et al. . Effects of tart cherry juice on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in older adults. Nutrients 2019;11:228 10.3390/nu11020228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuehl KS, Elliot DL, Sleigh AE, et al. . Efficacy of tart cherry juice to reduce inflammation biomarkers among women with inflammatory osteoarthritis (OA). J Food Stud 2012;1:14–25. 10.5296/jfs.v1i1.1927 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schumacher HR, Pullman-Mooar S, Gupta SR, et al. . Randomized double-blind crossover study of the efficacy of a tart cherry juice blend in treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. Osteoarthr Cartil 2013;21:1035–41. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NICE Clinical knowledge summary: gout, 2018. Available: https://cks.nice.org.uk/gout#!scenario:1 [Accessed 5 Sep 2019].

- 30.Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. . 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:29–42. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arthritis Research UK Gout, 2016. Available: https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/conditions/gout/ [Accessed 6 Jun 2019].

- 32.Mayo Clinic Gout: diagnosis and treatment, 2019. Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gout/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20372903 [Accessed 4 Jun 2019].

- 33.UK Gout Society All about gout and diet. Available: http://www.ukgoutsociety.org/PDFs/goutsociety-allaboutgoutanddiet-0917.pdf [Accessed 9 Feb 2019].

- 34.U.S. Food and Drug Administration List of firms receiving warning letters regarding cherry and other fruit-based products with disease claims in labeling, 2005. Available: http://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170406024549/https:/www.fda.gov/Food/ComplianceEnforcement/WarningLetters/ucm081724.htm [Accessed 5 May 2019].

- 35.Duyck SD, Petrie KJ, Dalbeth N. “You Don't Have to Be a Drinker to Get Gout, But It Helps”: A Content Analysis of the Depiction of Gout in Popular Newspapers. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1721–5. 10.1002/acr.22879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.NHS Choices Cherry juice touted as treatment for gout, 2014. Available: https://www.nhs.uk/news/food-and-diet/cherry-juice-touted-as-treatment-for-gout/ [Accessed 17 Jun 2018].

- 37.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. . Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caliceti C, Calabria D, Roda A, et al. . Fructose intake, serum uric acid, and cardiometabolic disorders: a critical review. Nutrients 2017;9:395 10.3390/nu9040395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alvarez-Hernández E, Peláez-Ballestas I, Vázquez-Mellado J, et al. . Validation of the health assessment questionnaire disability index in patients with gout. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:665–9. 10.1002/art.23575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalbeth N, Ames R, Gamble GD, et al. . Effects of skim milk powder enriched with glycomacropeptide and G600 milk fat extract on frequency of gout flares: a proof-of-concept randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:929–34. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothenbacher D, Primatesta P, Ferreira A, et al. . Frequency and risk factors of gout flares in a large population-based cohort of incident gout. Rheumatology 2011;50:973–81. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.