Abstract

Background

Currently, the most frequently used secondary treatment for patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) consists of vitamin K antagonists (VKA) targeted at an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.5 (range 2.0 to 3.0). However, based on the continuing risk of bleeding and uncertainty regarding the risk of recurrent VTE, discussion on the proper duration of treatment with VKA for these patients is ongoing. Several studies have compared the risks and benefits of different durations of VKA in patients with VTE. This is the third update of a review first published in 2000.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of different durations of treatment with vitamin K antagonists in patients with symptomatic venous thromboembolism.

Search methods

For this update, the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Specialised Register (last searched October 2013) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 9.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled clinical trials comparing different durations of treatment with vitamin K antagonists in patients with symptomatic venous thromboembolism.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors (SM, MP, and BH) extracted the data and assessed the quality of the trials independently.

Main results

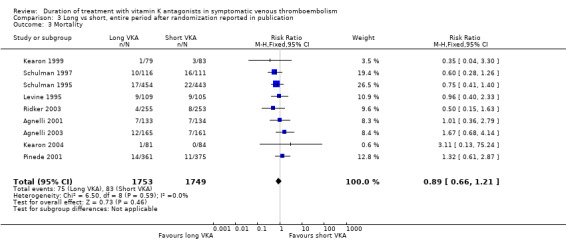

Eleven studies with a total of 3716 participants were included. A consistent and strong reduction in the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolic events was observed during prolonged treatment with VKA (risk ratio (RR) 0.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.11 to 0.38) independent of the period elapsed since the index thrombotic event. A statistically significant "rebound" phenomenon (ie, an excess of recurrences shortly after cessation of prolonged treatment) was not found (RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.70). In addition, a substantial increase in bleeding complications was observed for patients receiving prolonged treatment during the entire period after randomization (RR 2.60, 95% CI 1.51 to 4.49). No reduction in mortality was noted during the entire study period (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.21, P = 0.46).

Authors' conclusions

In conclusion, this review shows that treatment with VKA strongly reduces the risk of recurrent VTE for as long as they are used. However, the absolute risk of recurrent VTE declines over time, although the risk for major bleeding remains. Thus, the efficacy of VKA administration decreases over time since the index event.

Plain language summary

Length of treatment with vitamin K antagonists and prevention of recurrence in patients with venous thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurs when a blood clot is formed in a deep vein, or when it detaches itself and lodges in the lung vessels. These clots can be fatal if blood flow to the heart is blocked. Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) are given to people who have experienced a VTE, to prevent recurrence. The major complication of this treatment is bleeding. The continuing risk of bleeding with drug use and uncertainty regarding the extent of the risk of recurrence make it important to look at the proper duration of treatment with VKA for these patients. The review authors searched the literature and were able to combine data from 11 randomized controlled clinical trials (3716 participants) comparing different durations of treatment with VKA in patients with a symptomatic VTE. Participants receiving prolonged treatment had around five times lower risk of recurrence of VTE. On the other hand, they had about three times higher risk of bleeding complications. Prolonged treatment did not reduce the risk of death. Prolonged use of VKA strongly reduced the risk of recurrent clots as long as they were used, but benefit decreased over time and the risk of major bleeding remained.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Long‐term or short‐term treatment with vitamin K antagonists for patients with venous thromboembolism.

| Long‐term or short‐term treatment with vitamin K antagonists for patients with venous thromboembolism | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with venous thromboembolism Settings: hospitals and medical centers Intervention: long‐term treatment with VKA Comparison: short‐term treatment with VKA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Short‐term treatment with VKA | Long‐term treatment with VKA | |||||

| Incidence of recurrent VTE | 88 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (10 to 33) | RR 0.2 (0.11 to 0.38) | 3536 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| Incidence of major bleeding | 4 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (5 to 43) | RR 3.44 (1.22 to 9.74) | 1350 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Mortality | 38 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (13 to 51) | RR 0.69 (0.35 to 1.34) | 1049 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Relatively wide 95% confidence interval around the estimate. 2Only 4 studies (including 1 study without events) provided information on this outcome.

Background

Description of the condition

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), the collective term for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a disorder that is frequently encountered in medical practice, affecting two to three of every 1000 persons (general population) per year. Venous thromboembolism may occur after surgery, after trauma and immobilization, in cancer patients, during hormonal contraceptive use or pregnancy, and after delivery (provoked), but it also occurs in the absence of such clinical risk factors (unprovoked). Hereditary thrombophilic conditions such as antithrombin, protein C, and protein S deficiencies, as well as Factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A mutations, increase the risk for both provoked and unprovoked venous thromboembolic events.

Description of the intervention

The most important aim of treatment for patients with VTE is to prevent recurrence, including potentially fatal PE. Patients are usually treated with an initial course of heparin or low‐molecular‐weight heparin (for approximately six days) associated with vitamin K antagonists (VKA) started simultaneously and continued for a period thereafter. This prolonged use of VKA has proven efficacy in comparison with placebo and low‐dose heparin (Hull 1979; Lagerstedt 1985). The general consensus is that VKA should be targeted to prolongation of prothrombin time, compatible with an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0 to 3.0.

Why it is important to do this review

Based on the continuing risk of bleeding and uncertainty regarding the risk of recurrent VTE, discussion on the proper duration of oral anticoagulant treatment in patients with VTE is ongoing. Several studies have compared the risks and benefits of different durations of VKA treatment in patients with VTE.

Therefore we evaluated in this review the reduction in the incidence of recurrent VTE and the excess of major bleeding associated with different durations of VKA in patients with VTE.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of different durations of treatment with vitamin K antagonists in patients with symptomatic venous thromboembolism.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies in which participants were randomly allocated to different durations of VKA. Studies were excluded if they were duplicate reports or preliminary reports of data later presented in full.

Types of participants

Studies were included if participants had symptomatic VTE. Studies were excluded if the trialists had not used accepted objective tests to confirm the diagnosis of DVT (eg, venography, ultrasonography) or PE (eg, high‐probability ventilation‐perfusion lung scan, pulmonary angiography).

Types of interventions

Studies were included if different durations of treatment with a VKA, such as warfarin and acenocoumarol, were compared. Studies were excluded if different target INR ranges were used in the treatment arms, or if continuous use of another anticoagulant or antiplatelet drug was reported.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism (DVT or PE).

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of major bleeding.

Mortality.

Studies were excluded if no data for thromboembolic events and bleeding were available, if outcome assessment was performed by assessors who were aware of study allocation, or if no breakdown was provided for minor and major bleeding.

The following criteria were accepted for the diagnosis of recurrent symptomatic DVT: an extension of an intraluminal filling defect on a venogram; a new intraluminal filling defect or an extension of nonvisualization of proximal veins in the presence of a sudden cutoff defect on a venogram that was seen on at least two projections; if no previous venogram was available for comparison, an intraluminal filling defect; if no venogram was available, abnormal results of compression ultrasonography in an area where compression had been normal, or a substantial increase in the diameter of the thrombus during full compression at the popliteal or femoral vein (Koopman 1996; Levine 1996); or, if neither a venogram nor an ultrasonographic study was available, a change in the results of impedance plethysmography from normal to abnormal.

The following criteria were accepted for the diagnosis of (recurrent) PE: a new intraluminal filling defect, an extension of an existing defect, or the sudden cutoff of vessels larger than 2.5 mm in diameter on a pulmonary angiogram; if no prior angiogram was available, an intraluminal filling defect or sudden cutoff of vessels larger than 2.5 mm in diameter on a pulmonary angiogram; or if no pulmonary angiogram was available, a defect of at least 75% of a segment on the perfusion scan, with normal ventilation. If the ventilation‐perfusion scan was nondiagnostic (and no pulmonary angiogram was available), satisfaction on the criteria for DVT was acceptable, or PE could be demonstrated at autopsy.

Hemorrhages were classified as major if they were intracranial or retroperitoneal, led directly to death, necessitated transfusion, or led to interruption of antithrombotic treatment or (re)operation. All other hemorrhages were classified as nonmajor.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (last searched October 2013) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 9, part of The Cochrane Library, (www.thecochranelibrary.com). See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL. The Specialised Register is maintained by the TSC and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and through handsearching relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals and conference proceedings which have been searched, as well as the search strategies used are described in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group module in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Searching other resources

Additional studies were sought by a manual search through reference lists of relevant studies and through personal communication with experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Evaluation of potentially eligible studies to confirm eligibility and to assess methodological quality was performed independently by the three review authors (SM, MP, BH). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and consensus was reached.

Data extraction and management

Eligible articles were reviewed and summary information extracted. The following information was sought: participant characteristics (age, gender, comorbidity); number of participants in each treatment arm; duration, type, and intensity of VKA; incidence and timing of symptomatic recurrent VTE and major bleeding episodes; and mortality.

Data were extracted independently by the three review authors (SM, MP, BH), using a standard form. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and consensus was reached.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this update, two review authors (SM, BH) independently assessed the risk of bias of each trial according to Higgins 2011 and based on the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, care providers, or outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, and other bias. For each of the domains, we assessed whether the study was at high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias by using the guidance provided by Higgins 2011. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and consensus was reached.

Measures of treatment effect

The incidence of recurrent VTE, major bleeding, and mortality for the different treatment arms was used to calculate a risk ratio (RR) separately for each trial. Our outcomes were dichotomous, and we expressed results as RRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

The participant was the individual unit of analysis for all comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

We analyzed available data (ie, while ignoring missing data).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity of study results was evaluated using the Chi2 test and I2 statistic for each outcome separately. When the probability value of the Chi2 test was < 0.10 and/or the I2 statistic was > 40%, heterogeneity was considered significant.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess the risk of bias from selective reporting of outcomes, we searched in clinicaltrials.gov and controlled‐trials.com for a study protocol of each trial. If a study protocol was available, we evaluated whether all of the study's prespecified outcomes of interest in our review had been reported in the prespecified way in the final publication.

Data synthesis

All data were analyzed by using the Review Manager software of The Cochrane Collaboration (RevMan 2012). The incidence of recurrent VTE, major bleeding, and mortality for the different treatment arms was used to calculate an RR separately for each trial. These RRs were combined across studies, giving weight to the number of events in each of the two treatment groups in each separate study, using the Mantel‐Haenszel procedure, which assumes a fixed treatment effect (Collins 1987; Mantel 1959; Yusuf 1985).

The advisability of combining the trials was addressed by performing a statistical test of heterogeneity, which considers whether differences in treatment effect over individual trials are consistent with natural variation around a constant effect (Collins 1987). In addition, qualitative assessment of heterogeneity was performed if indicated. When the probability value of the Chi2 test was < 0.10 and/or I2 was > 40%, heterogeneity was considered significant. In cases of significant heterogeneity, data from the studies were combined using a random‐effects model according to the method of DerSimonian and Laird. A Z‐test was performed to test the overall effect. If no significant heterogeneity was observed, studies were combined by using a fixed‐effect model.

Analyses were performed separately for:

the period from VKA cessation in the shorter duration arm until VKA cessation in the longer duration arm;

the period after cessation of study medication until the end of follow‐up;

the entire period after randomization reported in the publication;

if available in more than one study, comparisons of two specific durations (eg, six weeks vs six months) of VKA use;

studies with adequately concealed randomization; and

studies without missing values.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity (ie, I2 > 60%), we performed subgroup analyses to explore heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

To determine whether conclusions were robust to decisions made during the review process, we performed analyses separately for studies with adequate randomization and for studies in which none of the participants dropped out or were lost‐to‐follow up, for the period from cessation of treatment with VKA in the short duration arm until cessation of treatment in the long duration arm.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

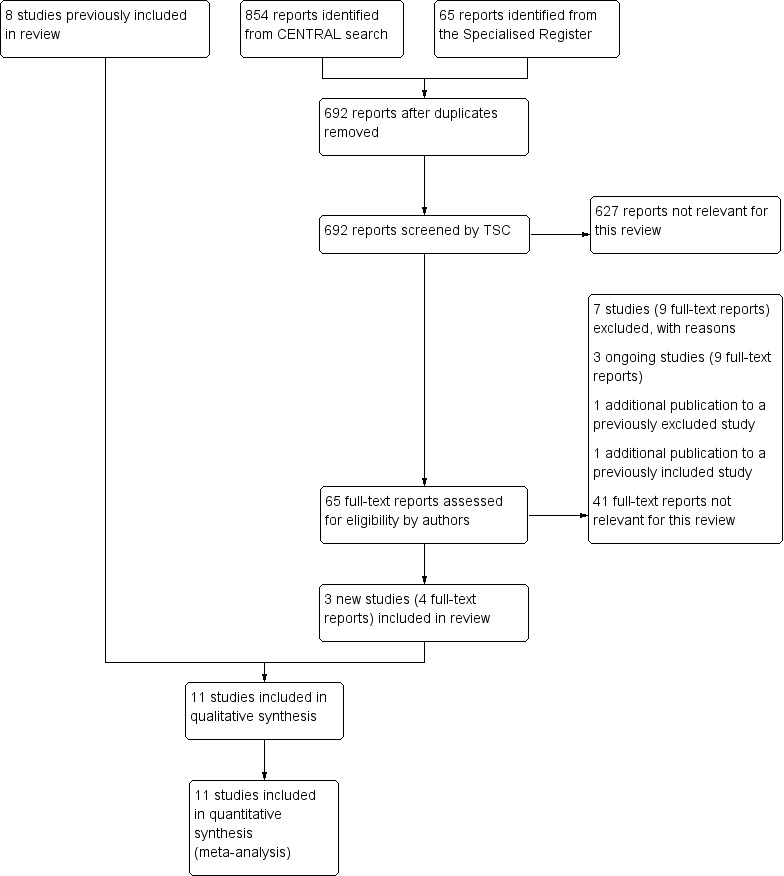

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Three additional studies were included in this update (Eischer 2009; Ridker 2003; Siragusa 2008), making a total of 11 included studies (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Eischer 2009; Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Ridker 2003; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997; Siragusa 2008), which were published between 1995 and 2009 with a total of 3716 participants. In seven studies (Agnelli 2001, Agnelli 2003, Eischer 2009, Kearon 1999, Kearon 2004, Schulman 1995, Siragusa 2008), participants with a first episode of VTE (ie, DVT,PE, or both) were included. Of these studies, Eischer 2009 included only participants with levels of FVIII above 230 IU/dL, and Siragusa 2008 included participants with residual vein thrombosis. In the study of Schulman 1997, participants with a second episode of VTE were included, and in the other two studies (Levine 1995; Pinede 2001), participants with acute proximal DVT were included. For the study of Ridker 2003, it was unclear whether participants with a first or second episode of VTE were included. In all studies, objective diagnostic tests were used to confirm the diagnosis.

The 11 studies compared the following different periods of treatment with VKA: four weeks versus three months (Kearon 2004; Levine 1995), six weeks versus 12 weeks (Pinede 2001), six weeks versus six months (Schulman 1995), three months versus six months (Agnelli 2003, Pinede 2001), three months versus one year (Agnelli 2001; Siragusa 2008), three months versus 27 months (Kearon 1999), four months versus 27 months (Ridker 2003), six months versus 30 months (Eischer 2009), and six months versus four years (Schulman 1997). For details of these studies, see the Characteristics of included studies section.

Excluded studies

For this update, seven additional studies were excluded (Agrawal 2011; Ascani 1999; Campbell 2007; Farraj 2004; Ferrara 2006; Palareti 2006; Prandoni 2009), making a total of 14 excluded studies (Agrawal 2011; Ascani 1999; Campbell 2007; Drouet 2003; Farraj 2004; Fennerty 1987; Ferrara 2006; Holmgren 1985; Lagerstedt 1985; O'Sullivan 1972; Palareti 2006; Prandoni 2009; Schulman 1985; Sudlow 1992). Studies were excluded for the following reasons (some studies were excluded for more than one reason): no objective tests used to confirm VTE for all participants (Campbell 2007; Fennerty 1987; Holmgren 1985; O'Sullivan 1972; Sudlow 1992); no blinded or partly blinded outcome assessment or unclear whether blinded outcome measurement was used (Agrawal 2011; Campbell 2007; Drouet 2003; Farraj 2004; Fennerty 1987; Ferrara 2006; Holmgren 1985; Lagerstedt 1985; O'Sullivan 1972; Schulman 1985; Sudlow 1992); INR target range not the same in the treatment arms (Ascani 1999); duration of VKA in one arm tailored on the basis of ultrasonography findings (flexible duration) (Prandoni 2009); and discontinuation of treatment by all participants for one month before randomization (Palareti 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

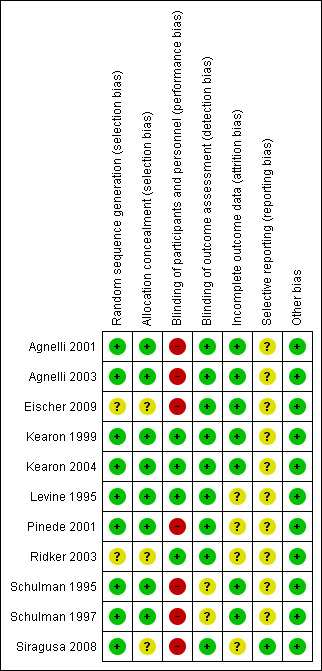

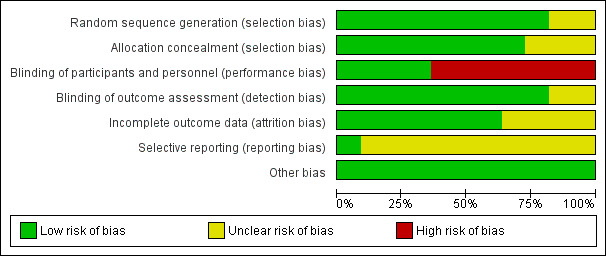

See also the Risk of bias in included studies summary (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Nine studies (82%) were deemed to have adequate sequence generation and therefore were classified as being at low risk of bias for this domain (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997; Siragusa 2008). The risk of bias was unclear for two studies because they did not provide information about the randomization process (Eischer 2009; Ridker 2003). In eight studies, the assigned treatment was adequately concealed before allocation (low risk of selection bias) (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997) and was unclear for the remaining three studies (Eischer 2009; Ridker 2003; Siragusa 2008).

Blinding

In four of the included studies, participants were randomly assigned to the sham duration of treatment with VKA and received placebo and sham monitoring (Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Ridker 2003). These studies were classified as being at low risk for performance bias. In the other seven included studies, treatment was not blinded (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Eischer 2009; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997; Siragusa 2008). Outcome assessment was performed by a committee unaware of treatment allocation in all studies. In two of these studies, blinded outcome assessment was performed only for recurrent VTE, not for bleeding events (Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997). For these studies, the risk for detection bias was classified as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

One trial reported that 0.6% of participants were excluded after randomization (Schulman 1995), and another study reported that 2.7% of participants withdrew shortly after randomization (Levine 1995). In two studies, 3% of participants were lost to follow‐up (Levine 1995; Pinede 2001). Schulman 1995 and Schulman 1997 mentioned that 4.9% and 6.2% of participants dropped out; however, the study authors were able to collect information about outcome events among these participants from computer registries.

Selective reporting

Only one study was registered at clinicaltrial.gov (Siragusa 2008), and all prespecified outcomes of interest in the review were reported in the prespecified way in the final publication. Therefore the risk for reporting bias was considered low in this study. For the remaining studies, the risk of reporting bias was classified as unclear.

Other potential sources of bias

Upon review of the studies, no other potential sources of bias were identified.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Incidence of recurrent VTE

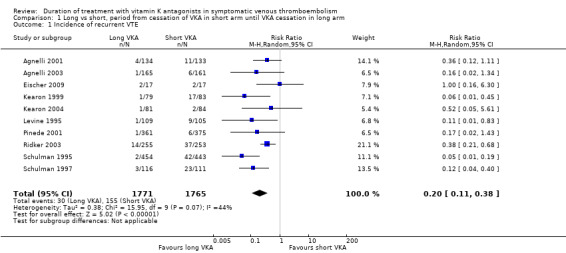

Ten of the 11 studies reported on the occurrence of symptomatic VTE during the period from cessation of treatment with VKA in the short duration arm until cessation of treatment in the long duration arm (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Eischer 2009; Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Ridker 2003; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997).

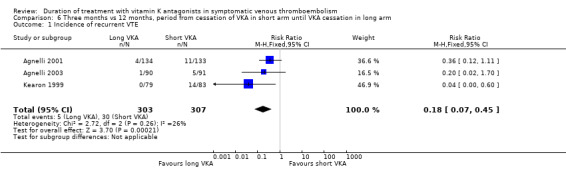

Five of the 10 studies showed statistically significant protection from recurrent venous thromboembolic complications during prolonged treatment with VKA (Kearon 1999; Levine 1995; Ridker 2003; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997). Four studies showed a clear trend (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Kearon 2004; Pinede 2001). The study of Eischer 2009 showed no difference (Analysis 1.1). Combining the ten studies revealed that 155 (8.8%) of 1765 participants had thromboembolic complications in the short arm, and only 30 (1.6%) of 1771 participants had thromboembolic complications in the long arm. Analysis of pooled data from these studies showed a statistically significant reduction in thromboembolic events during this period (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.38, P < 0.00001).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Long vs short, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm, Outcome 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE.

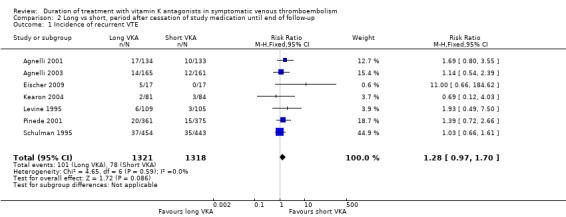

Seven of the 11 studies evaluated the incidence of recurrent VTE in the period after cessation of study medication until the end of follow‐up (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Eischer 2009; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995). These individual studies did not show a statistically significant increase in venous thromboembolic events among participants in the long arm after cessation of treatment. Combining these studies showed that 101 (7.6%) of 1321 participants who were treated for the longer period with VKA and 78 (5.9%) of 1318 participants who were treated for a shorter period experienced a recurrence (Analysis 2.1). Analysis of the pooled data showed a non–statistically significant difference in the incidence of recurrence during this period (RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.70, P = 0.09). Although a somewhat higher risk was found for participants in the long duration arm after cessation of treatment compared with those in the short duration arm, a rebound effect could not be clearly demonstrated.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Long vs short, period after cessation of study medication until end of follow‐up, Outcome 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE.

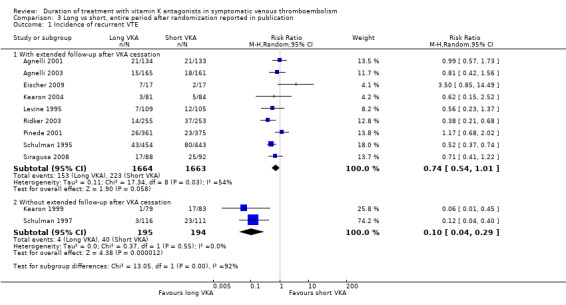

When the entire period after randomization reported in the publication was considered, four of the 11 studies showed statistically significant protection from recurrent thromboembolic complications (Kearon 1999; Ridker 2003; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997). See Analysis 3.1. Substantial heterogeneity could be observed between the studies (P = 0.0005, I2 = 68%). Graphically, two groups can be identified: those with extended follow‐up after cessation of treatment with VKA in the long arm (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Eischer 2009; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Ridker 2003; Schulman 1995; Siragusa 2008) (pooled data: RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.01) and those without extended follow‐up after cessation of treatment with VKA in the long arm (Kearon 1999; Schulman 1997) (pooled data: RR 0.10, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.29). Therefore, we decided to refrain from pooling all studies.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Long vs short, entire period after randomization reported in publication, Outcome 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE.

Comparisons of two specific durations

It was possible to extract data from more than one study for the following durations.

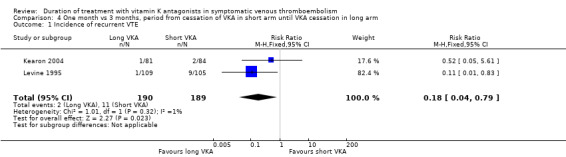

One month versus three months

Pooling the data from Kearon 2004 and Levine 1995 showed a significant reduction in recurrent VTE in participants who had received prolonged VKA treatment (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.79, P = 0.02). See Analysis 4.1.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 One month vs 3 months, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm, Outcome 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE.

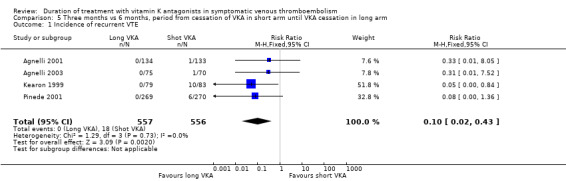

Three months versus six months

Pooling the data from Agnelli 2001, Agnelli 2003, Kearon 1999, and Pinede 2001 showed a significant reduction in recurrent VTE among participants who had received prolonged VKA treatment (RR 0.10, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.43, P = 0.002). See Analysis 5.1.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Three months vs 6 months, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm, Outcome 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE.

Three months versus 12 months

Pooling the data from Agnelli 2001, Agnelli 2003, and Kearon 1999 revealed a significant reduction in recurrent VTE among participants who had received prolonged VKA treatment (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.071 to 0.45, P = 0.0002). See Analysis 6.1.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Three months vs 12 months, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm, Outcome 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE.

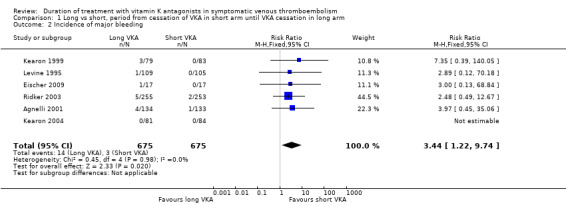

Incidence of major bleeding

Six studies reported on the incidence of major bleeding during the period from cessation of treatment with VKA in the short duration arm until cessation of treatment in the long duration arm (Agnelli 2001; Eischer 2009; Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Ridker 2003). None of the individual studies showed a statistically significant increase in bleeding complications during prolonged treatment with VKA. Combining these studies revealed that three (0.4%) of 675 participants had major bleeding in the short treatment arm versus 14 (2.1%) of 675 participants in the long treatment arm (Analysis 1.2). Analysis of pooled data from these studies showed a statistically significant increase in major bleeding complications during this period (RR 3.44, 95% CI 1.22 to 9.74, P = 0.02).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Long vs short, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm, Outcome 2 Incidence of major bleeding.

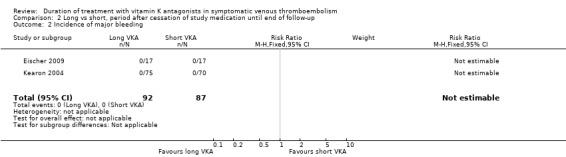

Two studies reported on the incidence of major bleeding in the period after cessation of study medication in the long duration arm until end of follow‐up (Eischer 2009; Kearon 2004). However, both studies reported no major bleeding events during this period.

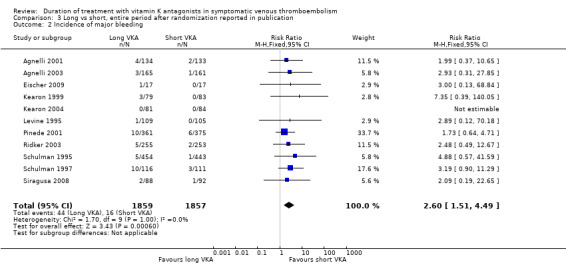

All included trials reported on the occurrence of major bleeding complications for the entire period after randomization until end of follow‐up (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Eischer 2009; Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Ridker 2003; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997; Siragusa 2008). None of the individual studies showed a statistically significant increase in bleeding complications during prolonged treatment with VKA. Combining these studies revealed that 44 (2.4%) of 1859 participants with prolonged treatment and 16 (0.9%) of 1857 participants with short treatment had major bleeding (Analysis 3.2). Analysis of pooled data showed an increase in major bleeding during the entire study period (RR 2.609, 95% CI 1.51 to 4.49, P = 0.0006).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Long vs short, entire period after randomization reported in publication, Outcome 2 Incidence of major bleeding.

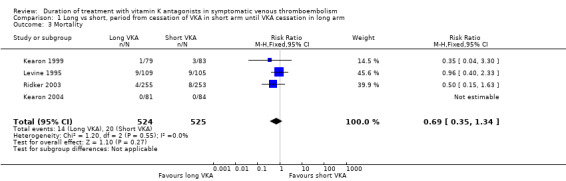

Mortality

Four studies reported mortality during the period from cessation of treatment with VKA in the short duration arm until cessation of treatment in the long duration arm (Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Ridker 2003). Two of these studies showed a non–statistically significant reduction in mortality during prolonged treatment with vitamin K antagonists (Kearon 1999; Ridker 2003). No trend was observed in Levine 1995. Combining these studies showed that 20 (3.8%) of 525 participants in the short arm died, as did 14 (2.7%) of 524 participants in the long arm (Analysis 1.3). Analysis of pooled data from these studies showed that prolonged treatment was associated with a non–statistically significant reduction in mortality (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.34, P = 0.27).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Long vs short, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm, Outcome 3 Mortality.

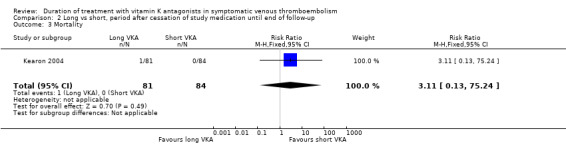

Only one study reported specifically on the number of participants who died during the period after cessation of study medication in the long arm until end of follow‐up (Kearon 2004). Nine studies reported on mortality for the entire period after randomization (Agnelli 2001; Agnelli 2003; Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Pinede 2001; Ridker 2003; Schulman 1995; Schulman 1997). None showed a statistically significant reduction in mortality. Combining these studies revealed that 75 (4.3%) of 1753 participants died with prolonged treatment and 83 (4.7%) of 1749 participants died without prolonged treatment with VKA (Analysis 3.3). Analysis of pooled data showed a non–statistically significant reduction in mortality during the entire study period (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.21, P = 0.46).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Long vs short, entire period after randomization reported in publication, Outcome 3 Mortality.

Sensitivity analysis

Analysis of studies with adequate concealment of allocation before randomization

Separate analyses for studies with adequate allocation concealment did not change the results significantly.

Analysis of studies without missing values

Separate analyses for studies in which none of the participants dropped out or were lost to follow‐up did not change the results significantly.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review, data from included studies were pooled to evaluate the efficacy and safety of different durations of treatment with VKA among participants with symptomatic VTE.

We found a statistically significant reduction in recurrent VTE during the period in which treatment with VKA was prolonged, which was independent of the period elapsed since the index thromboembolic event (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.38, P < 0.00001). Although the periods of treatment differed greatly between studies, these periods could be combined because the relative effect of oral anticoagulant treatment was considered and was homogeneous during the period of continuation. Reduction in recurrent VTE during the period that treatment with VKA was prolonged may be somewhat counterbalanced by an excess of recurrences shortly after cessation of prolonged treatment, but this finding did not reach statistical significance (RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.70, P = 0.09). In addition, a substantial increase in bleeding complications was observed among participants during the period in which VKA was prolonged (RR 3.44, 95% CI 1.22 to 9.74), and a non–statistically significant reduction in mortality was shown (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.34).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only four studies reported mortality during the period from cessation of treatment with VKA in the short duration arm until cessation of treatment in the long duration arm (Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Ridker 2003). Furthermore, as in all randomized controlled trials, stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, which means that the current evidence is applicable to patients without increased risk of bleeding. It is likely that absolute bleeding risk is higher in real‐world patients.

Quality of the evidence

See Table 1. In general, high‐quality evidence suggests that prolonged treatment with VKA reduces the risk for recurrent VTE. Moderate‐quality evidence indicates that prolonged treatment with VKA increases the risk for major bleeding events. We considered the quality of evidence as moderate because of relatively wide confidence intervals around the point estimate; however the point estimates were very similar across all included trials. Moderate‐quality evidence suggests that prolonged treatment with VKA does not reduce mortality significantly, although this was measured in only four studies, one of which reported no deaths (Kearon 1999; Kearon 2004; Levine 1995; Ridker 2003).

Potential biases in the review process

As two review authors selected and extracted the data independently, the risk of potential bias will be low. Furthermore, we consider it unlikely that we have missed important trials in our search for data because of the extensive literature searches that we conducted. As all studies were investigator‐initiated, we consider it unlikely that trials with a less favourable outcome have not been published.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Although the relative risk reductions remain stable over time elapsed since the index event (RRs varying around 80%), the absolute risk reduction is decreased over time. This can be illustrated by comparing the studies of Levine 1995 and Schulman 1995 with that of Schulman 1997. The studies of Levine 1995 and Schulman 1995 showed an absolute risk reduction of 8% to 9% achieved with only two to 4.5 months of prolonged treatment in the early phases after the thrombotic event. This is far more efficient than the absolute risk reduction of 18% achieved with 42 months of additional treatment in the study of Schulman 1997, six months after the index event. The decline in the incidence of recurrent VTE over time was also observed in the cohort studies of Prandoni 1996 and in the meta‐analysis of cohort studies and randomized controlled trials performed by van Dongen 2003. All of this indicates that a greater amount of effort (ie, years of treatment) will be needed to prevent one recurrent event when the time since the index event is increased. This fact is further complicated by a statistically significant and clinically important increase in bleeding complications, which continued during prolongation. A meta‐analysis of 33 trials and prospective cohort studies showed that absolute bleeding risk among participants with VTE treated for longer than three months with VKA was 2.7 per 100 patient‐years (Linkins 2003). The case fatality rate of major bleeding was 13.4% (9.4% to 17.4%), and the rate of intracranial bleeding was 1.15 (1.14 to 16) per 100 patient‐years (Linkins 2003). For participants who received anticoagulants for longer than three months, the case fatality rate of major bleeding remained high at 9.1% (2.5% to 21.7%), and the rate of intracranial bleeding was 0.65 (0.63 to 0.68) per 100 patient‐years. This adds to a further decrease in net clinical benefit of prolonged treatment with VKA after VTE.

The decrease in efficacy and the remaining risk for bleeding during continuing treatment indicate that at some point in time, further continuation is not cost‐effective, nor is it harmful. Given that the case fatality rate of recurrent VTE decreases over time (Carrier 2010), whereas the risk of major bleeding increases with age, the optimum length of anticoagulant treatment after an episode of VTE remains uncertain (De Jong 2012; Middeldorp 2011). As patients have different risk profiles, it is likely that this optimal duration will vary. However, on the basis of our results alone, the optimal duration cannot be defined. For this purpose, a decision analytic approach could be used by balancing benefit and risk on the basis of individual risk profiles (Prins 1999a; Prins 1999b).

In conclusion, this meta‐analysis shows that treatment with VKA reduces the risk of recurrent VTE for as long as they are used. However, the absolute risk of recurrent VTE declines over time, although the risk for major bleeding remains. Thus, the efficacy of VKA administration decreases over time from occurrence of the index event.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This systematic review indicates that prolonged treatment with VKA reduces the risk of recurrent VTE for as long as they are used. However, lifelong treatment seems not to be indicated, in that efficacy during continuing treatment decreases, while the risk for major bleeding remains.

Implications for research.

Further studies are required to determine for how long the duration of treatment with VKA should be extended. As patients have different risk profiles, the optimal duration will vary between specific groups. For this purpose, a decision analytic approach could be used by balancing benefit and risk on the basis of individual risk profiles. Furthermore, the expected increasing use of NOACs for prolonged treatment of VTE may modify the balance between recurrent VTE risk and bleeding.

Feedback

Anticoagulant feedback, 14 February 2011

Summary

Feedback received on this review, and other reviews and protocols on anticoagulants, is available on the Cochrane Editorial Unit website at http://www.editorial‐unit.cochrane.org/anticoagulants‐feedback.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 February 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New search run and review updated. Three additional studies included and seven additional studies excluded. All included studies assessed for risk of bias. Text updated. Summary of findings table added. No change to conclusions |

| 27 February 2014 | New search has been performed | New search run. Three additional studies included and seven additional studies excluded |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1999 Review first published: Issue 3, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 February 2011 | Amended | Link to anticoagulant feedback added |

| 6 March 2009 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 October 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The Peripheral Vascular Diseases Review Group for their assistance with searching the literature.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Thrombosis] this term only | 1186 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Thromboembolism] this term only | 999 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Venous Thromboembolism] this term only | 294 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Venous Thrombosis] explode all trees | 2187 |

| #5 | (thromboprophyla* or thrombus* or thrombotic* or thrombolic* or thromboemboli* or thrombos* or embol*):ti,ab,kw | 11899 |

| #6 | MeSH descriptor: [Pulmonary Embolism] explode all trees | 870 |

| #7 | PE or DVT or VTE:ti,ab,kw | 2183 |

| #8 | ((vein* or ven*) near thromb*):ti,ab,kw | 5065 |

| #9 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 | 13607 |

| #10 | MeSH descriptor: [Anticoagulants] this term only | 3378 |

| #11 | MeSH descriptor: [Coumarins] explode all trees | 1553 |

| #12 | k near/3 antagon* | 394 |

| #13 | VKA | 58 |

| #14 | anticoagula* | 6255 |

| #15 | anti‐coagula* | 166 |

| #16 | warfarin* | 2237 |

| #17 | *coum* | 866 |

| #18 | Jantoven or Marevan or Lawarin or Waran or Warfant or Dindevan | 23 |

| #19 | phenindione | 52 |

| #20 | Sinthrome or Sintrom | 16 |

| #21 | Marcumar or Falithrom | 16 |

| #22 | aldocumar or tedicumar | 8 |

| #23 | #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 | 7863 |

| #24 | #9 and #23 in Trials | 2318 |

| #25 | extend* or prolong*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 24359 |

| #26 | duration:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 42645 |

| #27 | long*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 73370 |

| #28 | continue:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 20076 |

| #29 | indefinite:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 62 |

| #30 | stop*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 6919 |

| #31 | short:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 43468 |

| #32 | #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 | 162919 |

| #33 | #24 and #32 in Trials | 854 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Long vs short, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE | 10 | 3536 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.11, 0.38] |

| 2 Incidence of major bleeding | 6 | 1350 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.44 [1.22, 9.74] |

| 3 Mortality | 4 | 1049 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.35, 1.34] |

Comparison 2. Long vs short, period after cessation of study medication until end of follow‐up.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE | 7 | 2639 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.97, 1.70] |

| 2 Incidence of major bleeding | 2 | 179 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Mortality | 1 | 165 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.11 [0.13, 75.24] |

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Long vs short, period after cessation of study medication until end of follow‐up, Outcome 2 Incidence of major bleeding.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Long vs short, period after cessation of study medication until end of follow‐up, Outcome 3 Mortality.

Comparison 3. Long vs short, entire period after randomization reported in publication.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 With extended follow‐up after VKA cessation | 9 | 3327 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.54, 1.01] |

| 1.2 Without extended follow‐up after VKA cessation | 2 | 389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.04, 0.29] |

| 2 Incidence of major bleeding | 11 | 3716 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.60 [1.51, 4.49] |

| 3 Mortality | 9 | 3502 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.66, 1.21] |

Comparison 4. One month vs 3 months, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE | 2 | 379 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.04, 0.79] |

Comparison 5. Three months vs 6 months, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE | 4 | 1113 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.02, 0.43] |

Comparison 6. Three months vs 12 months, period from cessation of VKA in short arm until VKA cessation in long arm.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of recurrent VTE | 3 | 610 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.07, 0.45] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Agnelli 2001.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: Randomization sequence was computer‐generated; no further details were given Concealment of allocation: yes, central randomization Blinding: open trial with independent, blinded assessment of outcome events Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: none |

|

| Participants | Country: Italy Setting: 10 hospitals Participants: 267 patients Mean age: 67 (SD 7) years Gender (M/F): 154/113 Inclusion criteria: Patients ranging from 15 to 85 years old with a first episode of symptomatic idiopathic proximal DVT, as demonstrated by compression ultrasonography or venography, were eligible for the study, provided they had completed 3 uninterrupted months of VKA without a recurrence of thromboembolism or bleeding Exclusion criteria: patients who required prolonged anticoagulant therapy for reasons other than VTE, patients with major psychiatric disorders with a life expectancy shorter than 2 years, those who could not return for follow‐up visits, and those who declined to participate |

|

| Interventions | Both groups were treated for 3 months with warfarin (in 97% of cases) or acenocoumarol. Participants were then randomly assigned to:

The dose of warfarin or other oral anticoagulant was adjusted to achieve a target INR between 2.0 and 3.0 |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrent VTE Secondary outcomes: bleeding complications and death Follow‐up: 33 months after randomization |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomization |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Agnelli 2003.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: Randomization was performed centrally in permuted blocks of 6 Concealment of allocation: yes, central randomization Blinding: independent, blinded assessment of outcome events Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: none |

|

| Participants | Country: Italy Setting: 19 hospitals Participants: 145 patients Mean age: 62 (SD 16) years Gender (M/F): 132/194 Inclusion criteria: consecutive patients ranging from 15 to 85 years of age with a first episode of symptomatic, objectively confirmed PE who had completed 3 uninterrupted months of VKA without a recurrence of bleeding Exclusion criteria: patients who required prolonged anticoagulant therapy for reasons other than VTE, patients with major psychiatric disorders with a life expectancy shorter than 2 years, those who could not return for follow‐up visits, and those who declined to participate |

|

| Interventions | Participants were first treated for 3 months with warfarin or acenocoumarol. Thereafter, they were randomly assigned to:

The dose of warfarin or other oral anticoagulant was adjusted to achieve a target INR between 2.0 and 3.0 |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrence of symptomatic, objectively confirmed VTE Secondary outcomes: cumulative incidence of adverse outcome events (recurrence of VTE, death, or major bleeding) Follow‐up: 33 months after randomization |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomization |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Eischer 2009.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: not reported Concealment of allocation: not reported Blinding: open study Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: none |

|

| Participants | Countries: Austria and Sweden Setting: 13 hospitals Participants: 34 patients Mean age: 53.5 (SD 17) years Gender (M/F): 11/23 Inclusion criteria: patients older than 18 years with a first DVT and/or PE. Diagnosis of VTE had to be objectified by venography or color‐coded duplex ultrasound in case of DVT, or by perfusion/ventilation lung scan or spiral CT in case of PE Exclusion criteria: VTE provoked by surgery, trauma, prolonged bed rest, pregnancy, or puerperium; deficiency of antithrombin, protein C, or protein S; antiphospholipid syndrome; active malignancy; poor compliance before study entry (less than 30% of international normalized ratio (INR) values within the therapeutic range); indication for long‐term anticoagulation other than VTE; acute‐phase reaction (C‐reactive protein > 1 mg/dL) at the time of factor VIII measurement; FVIII levels below 230 IU/dL; or refusal to participate |

|

| Interventions | All participants had been treated with unfractionated or low‐molecular‐weight heparin at therapeutic dosages and subsequently received VKA for 6 months. Thereafter, they were randomly assigned to:

|

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrent symptomatic VTE and major bleeding within 2 years | |

| Notes | In the publication, the methods section states: "The diagnosis of endpoints was established by an adjudication committee consisting of independent clinicians and radiologists unaware of the factor VIII levels." Because we were wondering whether the adjudicators were also blinded for the duration of treatment, we contacted the study authors. They confirmed on January 25, 2013 that the adjudicators were also blinded for the duration of treatment. For external validity: Only participants with high FVIII (measured repeatedly or at least 5 months after the acute VTE) were included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants randomly assigned but no information provided about the randomization procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants randomly assigned but no information provided about the randomization procedure |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Diagnosis of endpoint events established by an adjudication committee consisting of independent clinicians and radiologists unaware of allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Kearon 1999.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: computer‐generated, stratification according to whether participants presented with DVT alone or with PE and according to clinical center, randomly determined block size of 2 or 4 within each stratum Concealment of allocation: yes, randomization performed after eligibility was confirmed Blinding: double‐blinded and independent blinded outcome assessment Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: none |

|

| Participants | Countries: Canada and United States Setting: 11 Canadian hospitals and 2 hospitals in the United States Participants: 162 patients Mean age: 59 (SD 16) years Gender (M/F): 98/64 Inclusion criteria: patients with a first episode of idiopathic VTE and who had completed 3 uninterrupted months of VKA after an initial course of treatment with UFH or LMWH, patients with previous thromboembolism provided such episodes were secondary to a transient risk factor DVT demonstrated by bilateral compression ultrasonography of the proximal leg veins and (if possible) bilateral impedance plethysmography, and PE by ventilation‐perfusion lung scan Exclusion criteria: patients with other indications for, or contraindications to, long‐term anticoagulant therapy; who required long‐term treatment with nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, ticlopidine, sulfinpyrazone, dipyridamole, or more than 160 mg of aspirin per day; who had a familial bleeding disorder; who had a major psychiatric disorder; who were pregnant or could become pregnant; who were allergic to contrast medium; who had a life expectancy of less than 2 years; who were initially treated with a nonlicensed preparation of LMWH; who were considered likely to be noncompliant; or who were unable to complete follow‐up visits because of the distance from their residence to the medical center |

|

| Interventions | Participants were first treated for 3 months with warfarin. They were then randomly assigned to:

|

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrent VTE Secondary outcome: bleeding complications and mortality Follow‐up: 24 months after randomization |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization performed after eligibility was confirmed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Kearon 2004.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: stratification according to whether participants presented with asymptomatic DVT or with symptomatic VTE and according to clinical center Concealment of allocation: yes, randomization performed after eligibility was confirmed Blinding: double‐blinded and independent blinded outcome assessment Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: none |

|

| Participants | Countries: Canada and United States Setting: 11 Canadian hospitals and centers and 2 centers in the United States Participants: 165 patients Mean age: 56 (SD 16) years Gender (M/F): 87/78 Inclusion criteria: patients with a first episode of idiopathic VTE and who had completed 3 uninterrupted months of VKA after an initial course of treatment with UFH or LMWH; patients with previous thromboembolism provided such episodes were secondary to a transient risk factor DVT demonstrated by bilateral compression ultrasonography of the proximal leg veins and (if possible) bilateral impedance plethysmography, and PE by ventilation‐perfusion lung scan Exclusion criteria: patients with other indications for, or contraindications to, long‐term anticoagulant therapy; who required long‐term treatment with nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, ticlopidine, sulfinpyrazone, dipyridamole, or more than 160 mg of aspirin per day; who had a familial bleeding disorder; who had a major psychiatric disorder; who were pregnant or could become pregnant; who were allergic to contrast medium; who had a life expectancy of less than 2 years; who were initially treated with a nonlicensed preparation of LMWH; who were considered likely to be noncompliant; or who were unable to complete follow‐up visits because of the distance from their residence to the medical center |

|

| Interventions | Participants were first treated for 1 month with warfarin. They were then randomly assigned to:

|

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrent VTE Secondary outcomes: bleeding complications and mortality Follow‐up: 11 months after randomization |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization performed after eligibility was confirmed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Levine 1995.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: computer‐generated allocation schedule; stratification by clinical center, presence or absence of underlying malignancy, and recent therapy with thrombolytic therapy or not Concealment of allocation: yes, randomization performed after eligibility was confirmed Blinding: double‐blinded and independent blinded outcome assessment Exclusions post randomization: 4 participants in warfarin group and 2 in placebo group Losses to follow‐up: 7 participants (6 warfarin group and 1 placebo group) reported as lost to follow‐up |

|

| Participants | Countries: Canada and Italy Setting: 3 Canadian hospitals and 1 Italian hospital Participants: 220 patients Mean age: 63 (SD 15) years Gender (M/F): 109/105 Inclusion criteria: patients with a venographically confirmed acute proximal DVT (involving the popliteal or more proximal deep veins) Exclusion criteria: previous history of 2 or more episodes of DVT or PE; presence of a deficiency of antithrombin III, protein C, or protein S; current active bleeding process, active peptic ulcer disease, or familial bleeding disorder; need for continuing anticoagulant therapy not related to qualifying episode of DVT (eg, heart valve; inability to attend follow‐up visits because of geographic inaccessibility; expected survival of less than 3 months; presence of an underlying psychiatric or affective disorder; or pregnancy |

|

| Interventions | Participants were first treated for 4 weeks with sodium warfarin. They were then randomly assigned to:

|

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrent DVT or PE and major bleeding during first 8 weeks after randomization Secondary outcome: recurrent DVT or PE and major bleeding during the 11‐month period after randomization Follow‐up: 11 months after randomization |

|

| Notes | Before randomization, participants were initially treated with heparin. Vitamin K antagonists were commenced on the fifth day and overlapped with intravenous heparin. After 4 weeks of warfarin, a normal impedance plethysmogram (IPG) was performed. Participants were eligible for the randomized study if their IPG was normal at 4 weeks | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization performed after eligibility was confirmed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blind study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 2.7% withdrew shortly after randomization because they changed their mind; 3.3% of participants did not complete the 9‐month follow‐up after taking 8 weeks of study medication |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Pinede 2001.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: computer‐generated allocation schedule in blocks of 4; schedule stratified for calf DVT or proximal DVT/PE Concealment of allocation: yes, central randomization Blinding: open‐label and independent blinded outcome assessment Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: 22 participants (3%) were reported as lost to follow‐up (14 in the short treatment arm, 8 in the long treatment arm) |

|

| Participants | Country: France Setting: 94 hospitals Participants: 736 patients (males and females) Age: not reported Gender (M/F): not reported Inclusion criteria: older than 18 years of age, written informed consent, and symptomatic thrombus below popliteal vein or proximal DVT and/or PE confirmed by positive Doppler ultrasonography or venography Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, breast‐feeding, previous VTE, vena cava filter implantation, surgical thrombectomy, free‐floating thrombus in the inferior vena cava lumen, DVT or PE whose diagnosis did not fulfill the predefined criteria, evolutionary cancer or malignant hematological disease, known biological thrombophilia, severe PE, PE treated by thrombolysis, myocardiopathy, or other diseases justifying prolonged anticoagulation therapy, and liver insufficiency |

|

| Interventions | At the end of heparin therapy, participants were randomly assigned to:

Participants received fluindione with a target INR range of 2.0 to 3.0 |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrent VTE Secondary outcomes: bleeding complications (major, minor, and fatal) and death Follow‐up: 15 months after randomization |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomization |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 3% lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Ridker 2003.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: randomization performed centrally and stratified according to clinical site, time since index event (< 6 months or > 6 months), and whether the index event was the participant's first VTE Concealment of allocation: not reported Blinding: double‐blinded, including sham INR measurements and warfarin dose adjustments in the placebo group, and independent blinded outcome assessment Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: not reported |

|

| Participants | Countries: USA and Canada Setting: 52 hospitals Participants: 508 patients (male and female) Median (interquartile range) age: placebo 53 (47 to 64) years, warfarin 53 (46 to 65) years Gender (M/F): 268/240 Inclusion criteria: Men and women 30 years of age or older with documented idiopathic VTE were eligible if they had completed at least 3 uninterrupted months of oral anticoagulation therapy with full‐dose warfarin Exclusion criteria: history of metastatic cancer, major gastrointestinal bleeding, or hemorrhagic stroke, or a life expectancy of less than 3 years. Patients who were being treated with dipyridamole, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, heparin, more than 325 mg of aspirin, or drugs that affect prothrombin time and patients who had known lupus anticoagulant antibodies or antiphospholipid antibodies were excluded Before randomization to the blinded clinical trial, eligible patients participated in a 28‐day open‐label run‐in phase. They were excluded during the run‐in phase if they could not have their dose of warfarin titrated to a stable level that achieved an INR between 1.5 and 2.0 without exceeding a dose of 10 mg per day, or when their level of compliance was less than 85% |

|

| Interventions | After a 28‐day open‐label run‐in phase, participants were randomly assigned to:

|

|

| Outcomes | Symptomatic recurrent VTE Major bleeding Composite endpoint of recurrent VTE, major bleeding, and death from any cause |

|

| Notes | The trial was terminated by the independent data and safety monitoring board after 508 participants had undergone randomization, because of the emergence of a large and statistically significant benefit of low‐intensity warfarin therapy in the absence of any substantial evidence of harm | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants randomly assigned but no information provided about the randomization procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants randomly assigned but no information provided about the randomization procedure |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used, including sham INRs and sham dose adjustments |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All endpoints reviewed by a committee of physicians who were unaware of treatment group assignments |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participant flow chart not provided; no information provided about losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Schulman 1995.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: computer‐generated allocation schedule in blocks of 10 Concealment of allocation: yes, central randomization Blinding: open‐label study with independent blinded outcome assessment for recurrent VTE (for bleeding events unclear) Exclusions post randomization: 5 participants (unknown from which treatment group) Losses to follow‐up: 44 participants (23 in the short treatment arm, 21 in the long treatment arm). However, the study authors were able to collect information about deaths and hospitalizations among these patients from computer registries |

|

| Participants | Country: Sweden Setting: 16 hospitals Participants: 897 patients Mean age: 61 (SD 15) years Gender (M/F): 504/393 Inclusion criteria: patients with a first episode of VTE, patients at least 15 years of age who had acute PE or DVT in the leg, the iliac veins, or both Exclusion criteria: a diagnosis of DVT or PE that did not fulfil the criteria described in the article; unavailability of the patient for follow‐up; pregnancy; allergy to warfarin or dicoumarol; an indication for continuous oral anticoagulation (eg, an artificial heart valve, chronic atrial fibrillation); permanent, total paresis of the affected leg; arterial insufficiency of the same leg that was graded at functional class III (pain at rest) or worse, constituting a contraindication to the use of compression stockings; a current/previous venous ulcer; cancer; unwillingness to give oral informed consent; patients who had had more than 1 thromboembolic event. Furthermore, enrolled participants were later excluded from the analysis if results of the initial biochemical screening revealed congenital deficiency of antithrombin, protein C, or protein S |

|

| Interventions | All participants were initially treated with UFH or LMWH administered intravenously or subcutaneously for at least 5 days, until a prothrombin time within the target range had been achieved. Treatment with warfarin sodium or dicoumarol was started at the same time as heparin (target INR 2.0 to 2.85) Treatment: as above for 6 months Control: as above for 6 weeks |

|

| Outcomes | Principal endpoints: major bleeding during anticoagulation and death or recurrent VTE Follow‐up: 2 years after randomization |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomization |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Blinded outcome assessment for recurrent VTE; unclear for bleeding events |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 4.9% of participants reported in Table 1 as lost to follow‐up; however, these participants were reviewed for the primary outcome |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Schulman 1997.

| Methods | Study design: RCT Method of randomization: computer‐generated, in blocks of 10, stratified to medical center study Concealment of allocation: central randomization Blinding: open‐label study with independent blinded outcome assessment for recurrent VTE (for bleeding events unclear) Exclusions post randomization: none Losses to follow‐up: 14 participants dropped out (unknown from which treatment group). However, the study authors were able to collect information about deaths and hospitalizations among these patients from computer registries |

|

| Participants | Country: Sweden Setting: 16 medical centers Participants: 227 patients Mean age: 65.5 (SD 12) years Gender (M/F): 138/89 Inclusion criteria: patients with a second episode of VTE; patients at least 15 years of age who had acute PE or DVT in the leg, the iliac veins, or both Exclusion criteria: a diagnosis of DVT or PE that did not fulfill the criteria described in the article; unavailability of the patient for follow‐up; pregnancy; allergy to warfarin or dicoumarol; an indication for continuous oral anticoagulation (eg, an artificial heart valve, chronic atrial fibrillation); permanent, total paresis of the affected leg; arterial insufficiency of the same leg that was graded at functional class III (pain at rest) or worse, constituting a contraindication to the use of compression stockings; a current/previous venous ulcer; cancer; unwillingness to give oral informed consent; patients who had had more than 1 thromboembolic event. Furthermore, enrolled participants were later excluded from the analysis if results of the initial biochemical screening revealed congenital deficiency of antithrombin, protein C, or protein S |

|

| Interventions | All participants were initially treated with UFH or LMWH administered intravenously or subcutaneously for at least 5 days, until a prothrombin time within the target range had been achieved. Treatment with warfarin sodium or dicoumarol was started at the same time as heparin (target INR 2.0 to 2.85) Treatment: as above continued indefinitely Control: as above for duration of 6 months |

|

| Outcomes | Principal endpoints: major bleeding, death or recurrent VTE during the 4‐year period Follow‐up: 4 years after randomization |

|

| Notes | For external validity: only participants with second episode of VTE were included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomization |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Blinded outcome assessment for recurrent VTE; unclear for bleeding events |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 6.2% of participants dropped out; however, these participants were reviewed for the primary outcome |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available at clinicaltrials.gov or controlled‐trials.com |

| Other bias | Low risk | No concerns of other sources of bias |

Siragusa 2008.

| Methods | Study design: randomized clinical trial Method of randomization: a different randomization sequence for each study site was computer‐generated and balanced in blocks of 10 Concealment of allocation: not reported Blinding: outcomes were adjudicated by assessors who were blinded to treatment allocation Exclusions post randomization: none reported Losses to follow‐up: none reported |

|

| Participants | Country: Italy Setting: 3 medical centers Participants: 180 patients Mean age: 57.1 (SD 14.1) years in the treatment group, 61.1 (SD 11.5) years in the control group Gender (M/F): 95/85 Inclusion criteria: patients with a first episode of symptomatic proximal DVT who had received VKA for 3 months, and who were found to have residual vein thrombosis on compression ultrasonography (defined as thrombus occupying more than 40% of the vein diameter) Exclusion criteria: active cancer, limited life expectancy, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, or other known thrombophilic states (such as deficiencies of antithrombin and proteins C and S, homozygous for FV Leiden or FII 20210G > A mutations, or combined heterozygosity for the same), serious liver disease, renal failure, living too far from the recruiting center |

|

| Interventions | Initial treatment for the acute episode consisted of VKA for 3 months (no information is given about initial heparin treatment) Treatment: continue VKA (target INR 2.0 to 3.0) for 9 months Control: discontinue VKA |

|

| Outcomes | Endpoints: recurrent VTE and/or major bleeding Follow‐up: at least 1 year after VKA discontinuation |

|

| Notes | The patient population included in this review is part of a larger population of 258 patients with a first episode of VTE who had been treated for 3 months with VKA. 78 patients did not have residual vein obstruction, and all discontinued anticoagulant treatment; 180 patients with residual vein obstruction were randomly assigned to discontinue or continue treatment with VKA | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information given about the allocation procedure |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All suspected events evaluated by a central adjudication committee, whose members were unaware of the participant name, the center, and the group assignment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participant flow chart provided, but no information provided about losses to follow‐up |