Abstract

Citrus limon (L.) Burm is an important crop that grows between latitudes 30° North and 30° South, the main producers being China, the USA, Mexico, India, Brazil, and Spain. In Spain, lemon grows mainly in Mediterranean areas such as Murcia, Valencia, and Andalucía. The most cultivated varieties are “Fino” and “Verna”. In this study, five varieties of lemon, “Verna”, “Bétera”, “Eureka”, “Fino 49”, and “Fino 95” were evaluated on different rootstocks: three new Forner-Alcaide (“FA13”, “FA5”, “FA517”), Citrus macrophylla, Wester, and Citrus aurantium L. Hydrodistillation was used to obtain essential oil from fresh peels and then the volatile profile was studied by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). A total of 26 volatile compounds were identified, limonene being the main one followed by β-pinene, γ-terpinene, sabinene, and α-pinene. The results revealed that Forner-Alcaide rootstocks (“FA5” > “FA517” > “FA13”) proved to be the best rootstocks for the aroma quality as they led to high volatile contents, followed by C. aurantium and C. macrophylla. Among the other varieties, the most aromatic one was “Eureka”. The whole trend was as follows (in decreasing order): “Eureka” > “Bétera” > “Fino 95” > “Verna” > “Fino 49”.

Keywords: aroma composition, Citrus limon (L.), concentrations—monoterpene, GC-MS, limonene, sesquiterpenes, aldehydes

1. Introduction

Lemon is an important crop that grows in different parts of the world. The main lemon producers are in China, the United States, Mexico, India, Brazil, and Spain [1]. In Spain, it grows mainly in the Mediterranean areas of Murcia, Valencia, and Andalucía, which represent the highest productions [2]. These high productions are associated with selected, suitable, and compatible rootstocks [3]. Moreover, the use of rootstock influences quantitative and qualitative characteristics of agronomic variables which improve size, color, soluble solids, acidity, yield, and quality of the fruit [4,5,6].

Selecting the proper rootstock is decisive in order to succeed in a commercial citrus fruit plantation [4]. Fruit quality is currently valued, in addition to visual attributes (e.g., size, color), including chemical properties such as contents of vitamins, minerals, carotenoids, phenols, and volatile compounds [7]. The organic compounds are associated with the fruit aroma and are present in peel, flowers, leaves, and juice [8]. In citrus species, the main quality characteristic is the aroma [9]. The quality of the lemon is highly influenced by the rootstock [10]. Several factors may modify the volatile profile of the lemon, including factors such as rootstock and variety [11,12,13]. Among these factors we can include environment, soil fertility, the content of beneficial microorganisms, the state of immaturity (green color), and unpeeled vs. peeled fruit juice [14,15,16,17]. Additionally, the volatile fraction may be altered by analytical method, sampling, and equipment used [18,19].

Throughout the world, citrus flavors are some of the most important flavors in the global market [20]. In this sense, fresh lemon peel can be used to obtain volatile compounds which give the characteristic citrus aroma and flavor [21,22]. For this, many citrus cultivars have been analyzed to identify their volatile profile [20]. Several authors have studied the volatile profile of the oil from the lemon peel [22,23,24], but information on how the rootstock influences the odorous compounds is very limited.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify and quantify the volatile profile of five varieties of lemon grafted on five rootstocks and analyze the influence that the rootstock–graft interaction can have on the volatile profile of lemons.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Fruits were collected from 10-year-old, healthy trees, cultivated under the same pedoclimatic and cultural conditions. The climate was characterized by mild winters and slightly hot summers, temperatures ranging between 26 and 17 °C, and light rains concentrated in spring and autumn. Soil characteristics were as follows: sandy loam texture, 40% calcium carbonate, 8% active calcium, and pH = 8. The field was located at the IVIA (Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias) Experimental Station in Elche (latitude 38°14′56″ N, longitude 0°41′35.95″ E, altitude 149 m above sea level).

The selected varieties of Citrus limon used in this study were “Betera”, “Verna”, “Fino 49”, “Fino 95”, and “Eureka”; grafted on to the rootstocks Forner-Alcaide N°5 (“FA5”), Forner-Alcaide N°13 (“FA13”), Forner-Alcaide N°517 (“FA517”), C. macrophylla West, and C. aurantium L. The progenitors of hybrids Forner-Alcaide N°5 (“FA5”) and Forner-Alcaide N°13 (“FA13”) were “Cleopatra” mandarin × Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf., both characterized as being resistant to salinity and tolerant to waterlogging. Forner-Alcaide N°517 (“King” (mandarin) × P. trifoliata) is distinguished by its tolerance to limestone and its dwarfing character. All of them reside in the European Union (BOE/04/12/2007) and were obtained by targeted hybridizations by Forner in IVIA (Valencia) [25].

Twenty-five plots (a combination of variety and rootstock) were used for this study, with a completely randomized factorial design. Each plot was composed of six trees spaced at 6 m × 2.5 m.

Twenty lemons from each tree in each plot were collected. Next, the lemons were manually peeled with a peeler (no albedo was collected). Subsequently, the lemon peels were crushed with a grinder (Delhi model 180 W; Moulinex, Alençon, France) for 3 min and kept at −20 °C until analysis.

2.2. Determination of Volatile Compounds

For the determination of the volatile compounds, the essential oil was extracted using the protocol described by El-Zaeddi et al. [26] with slight modifications. Hydrodistillation (HD) using a Deryng system was used for isolating the essential oil in the lemons. Sixty grams of crushed lemon skin was placed in a 500 mL round-bottom flask with 200 mL of distilled water and 200 µL of isoamyl acetate, which was used as an internal standard. Once the mixture was boiling for 5 min, 2 mL of the essential oil was collected in a vial of 2.5 mL and maintained in refrigerated storage (4 °C) until the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses were conducted. All the samples were extracted in triplicate.

Volatile compounds were analyzed and identified using a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph coupled to a Shimadzu QP-5050A mass-spectrometry detector (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The GC-MS system was equipped with a Supelco (Supelco, Inc., Bellefonte, PA, USA) SLB-5 MS column (fused silica) 30 m × 0.25 mm, with a film thickness of 0.25 μm. The carrier gas used for this analysis was helium kept at a column flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1 and a total flow of 181.2 mL min−1 in a split ratio of 1:300. The program started with an increase of 3 °C min−1 from 80 to 170 °C. Afterwards, the temperature was increased at 25 °C·min−1 to 300 °C, maintaining this final temperature for 1 min. The temperature of the detector was 300 °C, and it was 230 °C for the injector.

Three methods were used to identify volatile compounds: (1) retention rates and their comparison with those in the literature; (2) retention times of pure chemical compounds; (3) mass spectra of authentic chemical compounds and the spectral library of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database. In this study, only fully identified compounds have been described. The analysis of the volatile composition was run in triplicate for each extraction and the results were expressed as the concentration of each of the volatile compounds as well as the concentration of the main chemical families of compounds.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple range test were performed to compare experimental data and to determine significant differences among varieties and rootstock (p < 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) using Pearson correlation was also run. The software XLSTAT (Addinsoft 2016.02.270444 version, Paris, France) was used.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Volatile Compounds in Lemon Peels

Twenty-six volatile compounds in the lemon peel oils were identified by GC-MS (Table 1). These compounds can be grouped into four main chemical families: (i) monoterpenes (20 compounds); (ii) sesquiterpenes (3 compounds); (iii) aldehydes (2 compounds), and (iv) esters (1 compound). Moreover, Table 1 shows the main sensory descriptors of each of the volatiles identified in the lemon peel oils.

Table 1.

Retention indexes of the volatile compounds by GC-MS in lemon peel oils.

| Compound | Chemical Family | Odor Properties | RT † (min) | KI (Exp.) ‡ | KI (Lit.) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-Thujene | Monoterpene | Wood, green, herb ⋆ | 5.09 | 930 | 933 |

| 2 | α-Pinene | Monoterpene | Pine, turpentine ⋆ | 5.28 | 939 | 944 |

| 3 | Camphene | Monoterpene | Camphor ⋆ | 5.64 | 969 | 964 |

| 4 | Sabinene | Monoterpene | Pepper, turpentine, wood ⋆ | 6.03 | 983 | 977 |

| 5 | β-Pinene | Monoterpene | Pine, resin, turpentine ⋆ | 6.21 | 990 | 990 |

| 6 | Octanal | Aldehyde | Strong and fruity smell ๏ | 6.62 | 1004 | 1001 |

| 7 | α-Phellandrene | Monoterpene | Turpentine, mint, spice ⋆ | 6.78 | 1010 | 1003 |

| 8 | α-Terpinene | Monoterpene | Lemon ⋆ | 7.04 | 1019 | 1018 |

| 9 | p-Cymene | Monoterpene | Woody and spicy ✠ | 7.25 | 1027 | 1026 |

| 10 | Limonene | Monoterpene | Lemon, orange ⋆ | 7.44 | 1034 | 1031 |

| 11 | γ-Terpinene | Monoterpene | Gasoline, turpentine ⋆ | 8.15 | 1059 | 1062 |

| 12 | cis-Sabinene-hydrate | Monoterpene | Herbal ⋆ | 8.64 | 1076 | 1074 |

| 13 | Terpinolene | Monoterpene | Herbal ⋆ | 8.99 | 1089 | 1089 |

| 14 | Linalool | Monoterpene | Flower, lavender ⋆ | 9.39 | 1103 | 1098 |

| 15 | Nonanal | Aldehyde | Rancid ✠ | 9.51 | 1106 | 1102 |

| 16 | Citronellal | Monoterpene | Fat ⋆ | 11.17 | 1152 | 1165 |

| 17 | Terpineol-4 | Monoterpene | Peppery, woody, sweet, musty ⋆ | 12.46 | 1189 | 1184 |

| 18 | α-Terpineol | Monoterpene | Oil, anise, mint ⋆ | 13.02 | 1204 | 1197 |

| 19 | Nerol | Monoterpene | Sweet ⋆ | 14.11 | 1231 | 1228 |

| 20 | Neral | Monoterpene | Lemon ⋆ | 14.63 | 1244 | 1239 |

| 21 | Geraniol | Monoterpene | Rose geranium ⋆ | 15.16 | 1257 | 1255 |

| 22 | Geranial | Monoterpene | Lemon, mint ⋆ | 15.82 | 1273 | 1277 |

| 23 | Neryl acetate | Ester | Fruit ⋆ | 19.43 | 1360 | 1366 |

| 24 | trans-Caryophyllene | Sesquiterpene | Wood and spicy ± | 22.18 | 1425 | 1420 |

| 25 | trans-α-Bergamotene | Sesquiterpene | Wood ⋆ | 22.59 | 1435 | 1437 |

| 26 | β-Bisabolene | Sesquiterpene | Balsamic ⋆ | 25.68 | 1509 | 1509 |

3.2. Effects of Rootstock/Scion Combination in the Profile Volatile Compounds

Table 2 shows the concentration of the 26 compounds, expressed in mg·kg−1, identified and quantified in lemon peel oils. The order from the highest to lowest concentration was: limonene, β-pinene, γ-terpinene, sabinene, α-pinene, geranial, neral, α-thujene, β-bisabolene, terpinolene, trans-α-bergamotene, α-terpineol, α-terpinene, neryl acetate, linalool, p-cymene, citronellal, trans-caryophyllene, terpineol-4, nerol, camphene, nonanal, geraniol, octylaldehyde, α-phellandrene, and cis-sabinene-hydrate. These results agreed with those previously obtained by Gonzalez-Mas et al. [30], Liu et al. [31], Cano-Lamadrid et al. [32], and Tekgül and Baysal [23].

Table 2.

Concentrations (mg·kg−1) of volatile compounds in lemon peel oils.

| ANOVA † | Variety | Rootstock | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | V | R | V*R | Verna | Betera | Eureka | Fino 49 | Fino 95 | FA 5 | FA 13 | FA 517 | C. macrophylla | C. aurantium |

| α-Thujene | *** | *** | *** | 195.1 a ‡ | 188.0 ab | 170.0 bc | 156.2 c | 120.8 d | 187.9 a | 179.5 a | 180.0 a | 140.4 b | 142.4 b |

| α-Pinene | *** | *** | *** | 797.3 a | 765.8 ab | 735.5 ab | 704.8 b | 648.5 b | 798.1 a | 743.8 ab | 743.2 ab | 685.5 b | 681.2 b |

| Camphene | *** | *** | *** | 24.8 a | 20.9 b | 20.9 b | 20.1 b | 13.1 c | 22.8 a | 21.2 ab | 18.9 b | 21.4 ab | 15.4 c |

| Sabinene | *** | *** | *** | 853.0 a | 758.8 b | 721.9 bc | 730.3 bc | 611.8 c | 802.6 a | 734.8 abc | 691.9 bc | 785.9 ab | 660.5 c |

| β-Pinene | *** | *** | *** | 5011 a | 4390 b | 4417 b | 4327 b | 3757 b | 4870 a | 4451 abc | 4193 bc | 4501 ab | 3888 c |

| Octanal | *** | *** | *** | 20.9 a | 18.8 a | 10.2 b | 18.5 a | 9.9 b | 16.2 a | 17.6 a | 15.1 ab | 19.0 a | 10.2 b |

| α-Phellandrene | *** | *** | *** | 15.5 a | 15.2 ab | 14.6 ab | 14.3 ab | 11.7 b | 16.0 a | 15.4 a | 15.9 a | 12.3 b | 11.7 b |

| α-Terpinene | *** | *** | *** | 101.0 a | 98.1 ab | 86.6 ab | 87.1 ab | 81.6 b | 101.9 a | 101.8 a | 99.2 a | 73.6 b | 77.9 b |

| p-Cymene | NS | NS | *** | 88.1 | 80.0 | 88.5 | 86.6 | 55.8 | 85.6 | 92.0 | 72.9 | 79.6 | 68.9 |

| Limonene | *** | *** | *** | 19,760 c | 21,140 b | 22,716 a | 20,398 bc | 22,107 ab | 22,248 a | 22,189 a | 22,726 a | 18,604 c | 20,354 b |

| γ-Terpinene | *** | *** | *** | 3849 a | 3786 a | 3439 ab | 3226 b | 3299 ab | 3967 a | 3807 a | 3882 a | 2770 b | 3172 b |

| cis-Sabinene-hydrate | *** | NS | *** | 15.3 a | 9.0 b | 7.7 b | 6.0 b | 3.8 b | 6.2 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 11.0 | 11.0 |

| Terpinolene | *** | *** | *** | 167.8 a | 166.2 a | 151.5 ab | 142.3 b | 145.2 ab | 175.5 a | 167.6 a | 171.2 a | 119.9 b | 138.8 b |

| Linalool | NS | NS | *** | 80.2 | 80.2 | 76.3 | 89.8 | 74.7 | 87.0 | 85.1 | 85.0 | 74.2 | 69.9 |

| Nonanal | NS | ** | ** | 21.1 | 21.4 | 17.8 | 23.9 | 14.8 | 19.0 ab | 19.1 ab | 14.7 b | 28.9 a | 17.4 b |

| Citronella | NS | *** | *** | 74.1 | 76.7 | 68.3 | 68.5 | 60.0 | 85.3 a | 77.2 a | 85.4 a | 49.7 b | 50.0 b |

| Terpineol-4 | * | NS | *** | 55.0 a | 52.7 a | 45.0 a | 52.3 a | 28.3 b | 50.7 | 57.1 | 46.7 | 46.7 | 32.1 |

| α-Terpineol | ** | NS | *** | 141.5 a | 141.7 a | 116.8 ab | 135.0 a | 60.6 b | 113.1 | 118.4 | 110.7 | 143.2 | 110.3 |

| Nerol | NS | NS | ** | 38.4 | 38.0 | 33.4 | 51.1 | 22.3 | 42.6 | 44.5 | 37.5 | 40.3 | 18.3 |

| Neral | NS | * | ** | 265.3 | 258.0 | 220.5 | 329.1 | 251.5 | 289.0 ab | 317.0 a | 287.3 ab | 237.4 ab | 193.5 b |

| Geraniol | NS | * | ** | 15.6 | 11.4 | 13.5 | 24.2 | 9.2 | 21.0 a | 21.2 ab | 14.5 ab | 12.4 ab | 3.8 b |

| Geranial | NS | NS | ** | 265.5 | 263.7 | 210.0 | 341.4 | 256.2 | 294.0 | 325.2 | 291.7 | 241.8 | 184.2 |

| Neryl acetate | NS | NS | *** | 107.8 | 92.3 | 122.2 | 86.1 | 59.9 | 99.5 | 82.7 | 89.4 | 92.5 | 104.1 |

| trans-Caryophyllene | *** | *** | *** | 64.8 ab | 61.4 ab | 75.8 a | 55.2 b | 46.9 b | 61.5 ab | 54.0 b | 71.2 a | 49.3 b | 68.0 ab |

| trans-α-Bergamotene | *** | *** | *** | 139.0 b | 142.5 ab | 168.2 a | 133.1 b | 124.0 b | 150.2 ab | 138.3 bc | 162.0 a | 117.5 c | 138.8 abc |

| β-Bisabolene | NS | *** | *** | 170.8 | 174.6 | 203.9 | 167.1 | 156.1 | 185.1 a | 171.9 ab | 197.0 a | 142.4 b | 176.1 ab |

| Total | NS | *** | *** | 32,338 | 32,851 | 33,950 | 31,473 | 32,029 | 34,796 a | 34,037 a | 34,310 a | 29,100 b | 30,399 b |

† NS = non-significant F ratio (p < 0.05); *, ** and *** significant at p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively. ‡ Values followed by the same letter within the same row were not significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s least significant difference test (n = 9).

The volatile profile of the five varieties of lemon studied was dominated by only five monoterpene hydrocarbon compounds (in decreasing order): limonene, β-pinene, γ-terpinene, sabinene, and α-pinene (Table 2). The most abundant volatile compound found in all varieties was limonene, and this volatile compound ranged from 19.76 g·kg−1 (“Verna”) to 22.71 g·kg−1 (“Eureka”). Limonene was followed by β-pinene, the content of which ranged from 3.75 g·kg−1 (“Fino 95”) to 5.01 g·kg−1 (“Verna”), γ-terpinene from 3.22 g·kg−1 (“Fino 49”) to 3.84 g·kg−1 (“Verna”), sabinene from 0.61 g·kg−1 (“Fino 95”) to 0.85 g·kg−1 (“Verna”), and α-pinene from 0.64 g·kg−1 (“Fino 95”) to 0.79 g·kg−1 (“Verna”). Among the varieties, the highest concentration of total volatile compounds was found (in decreasing order) in “Eureka”, followed by “Bétera” > “Fino 95” > “Verna” > “Fino 49”. The essential oil composition of the current five varieties of lemon was similar to that reported by Di Vaio et al. [33], who analyzed the peel of 18 lemon cultivars, and by Lota et al. [34] who analyzed the peel and leaf essential oils of 15 species of mandarins. Another 15 monoterpene hydrocarbons which had not been previously identified in lemon peel were also identified and quantified, but at lower contents (<0.2 g·kg−1). Di Vaio et al. [33] only identified 5 monoterpene in 18 lemon cultivars studied compared with the 20 monoterpenes identified in the present study. These differences may be due to the extraction methods, among other factors. Lu et al. [19] showed that differences in the presence or absence of volatile compounds depend on the oil distillation process; there is a greater presence of oxygenated compounds when hydrodistillated and a higher concentration of terpene compounds when pressed cold.

The results showed that rootstock strongly affected the total volatile contents (Table 2). The rootstocks of the Forner-Alcaide series (“FA517”, “FA13”, and “FA 5”) showed the highest values of limonene and γ-terpinene (>22 g·kg−1 and >3.8 g·kg−1, respectively), while the lowest values were in C. macrophylla and C. aurantium. In general, the series Forner-Alcaide rootstocks induced a greater content of all the volatile compounds identified compared to the traditional C. aurantium and C. macrophylla rootstocks. The reason for these differences among the rootstock of the Forner-Alcaide series and the C. aurantium and C. macrophylla rootstock might be to do with the specific rootstock/scion combinations which affect citrus fruit aroma volatiles levels, and these qualities may be governed by the level of rootstock/scion compatibility, which obviously affects the translocation of water, nutrients, plant growth regulators, and photosynthetic assimilates through the graft union.

The sesquiterpenes were the second most abundant chemical group in the lemon peel (Table 2). Only three compounds were identified (in decreasing order): β-bisabolene, trans-α-bergamotene, and trans-caryophyllene. Furthermore, the rootstocks of the Forner-Alcaide series showed the highest content for these three sesquiterpenes, while the C. macrophylla and C. aurantium had the lowest.

Two aldehyde compounds were identified: nonanal and octanal. The aldehyde concentrations were in the range of 14.7 to 28.9 mg·kg−1 in the varieties grafted on “FA 517” and C. macrophylla respectively for nonanal, and ranged between 10.2 mg·kg−1 to 19 mg·kg−1 in the varieties grafted on C. aurantium and “FA 5” respectively for octanal (Table 2).

Finally, regarding the esters, only one compound was identified: neryl acetate. No significant differences were observed in either the variety or the rootstock (Table 2).

In this study, we examined the effects of five rootstocks, three new in the Forner-Alcaide series, and two commercially important rootstocks (i.e., C. aurantium and C. macrophylla) on volatile compounds in the lemon peel oils of five varieties. The results indicate that the effect of rootstock on the volatile compounds is a rather complex phenomenon that greatly depends on specific interactions between the rootstock and each particular scion variety. Our results agreed with those reported by Benjamin et al. [4] in varieties of mandarins, Seker et al. [35] in the fruits of peach, and Wang et al. [12] in grapevines and in pistachios [36]—they all noted that rootstocks influenced the concentration and availability of volatiles. This could be explained by the fact that grafted plants generally increase the uptake of water and minerals due to the roots of rootstock or the compatibility of graft and canopy [37].

3.3. Principal Component Analysis

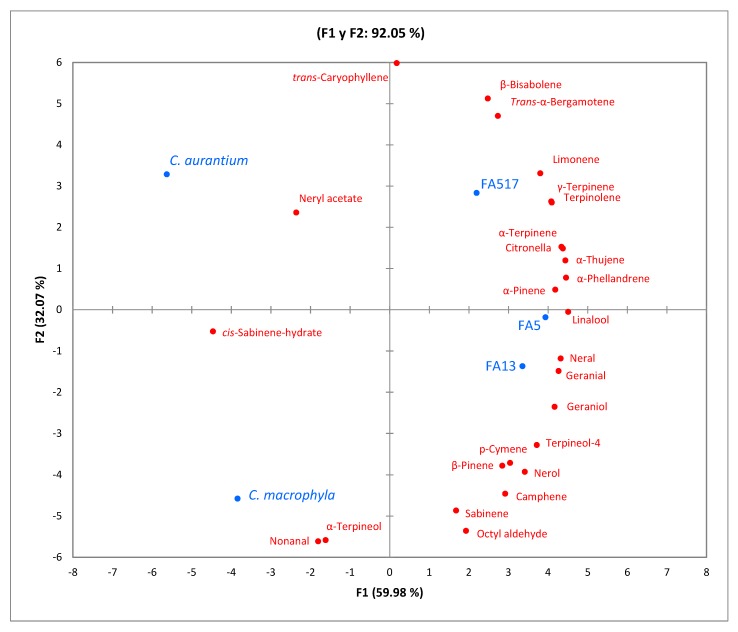

To better understand the relationships among the volatile compounds found (26 volatile compounds) in the different samples (varieties and rootstocks), principal component analyses (PCAs) were applied to the experimental results (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The PCA of the rootstocks (Figure 1) explained 92.05% of the variables in two axes, F1 (59.98%) and F2 (32.07%). Thanks to this statistical technique, it was very easy to observe that the C. macrophylla and C. aurantium rootstocks were isolated from the rest of the rootstocks, and were therefore characterized by volatile compounds such as nonanal and α-terpineol for C. macrophylla and neryl acetate in the case of C. aurantium. The rootstocks “FA517”, “FA5”, and “FA13” were linked to a higher number of volatile compounds, perhaps because genetically these rootstocks have a common parent and are characteristically smaller trees [25].

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing the relationships among volatile compounds and the factor “rootstock” (n = 9).

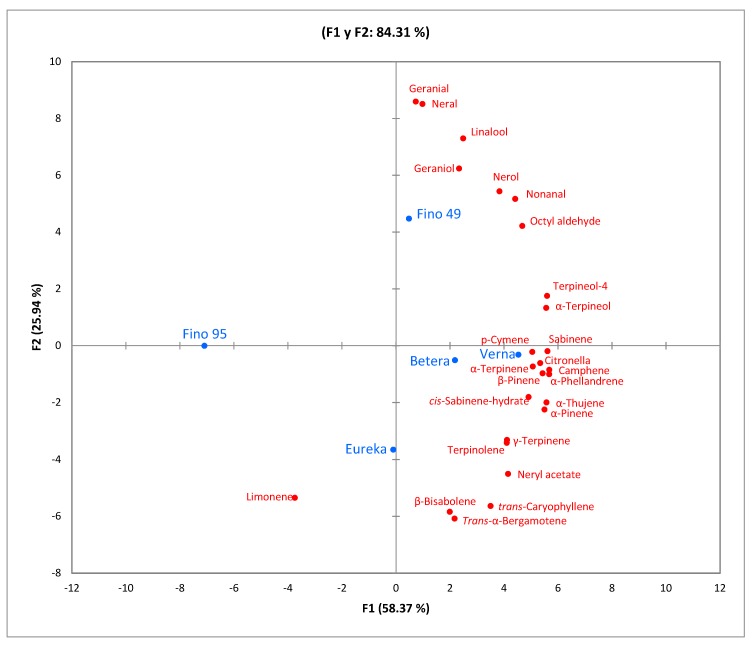

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing the relationship among volatile compounds and the factor “variety” (n = 9).

On the other hand, the PCA of the varieties (Figure 2) explained 84.31% of the variables in the F1 (58.37%) and F2 (25.94%) axes. This indicated that varieties such as “Betera”, “Verna”, and even “Eureka” had very similar aromatic profiles, while varieties such as “Fino 95” and “Fino 49” were isolated.

4. Conclusions

In this study, five rootstocks (three Forner-Alcaide rootstocks and two traditional C. macrophylla and C. aurantium rootstocks) were evaluated to study the effect on volatile composition of five commercial lemon varieties: “Bétera”, “Verna”, “Eureka”, “Fino 49”, and “Fino 95”. A total of 26 aromatic compounds were identified and quantified by GC-MS in lemon peel oils. Of all the aroma compounds identified in lemon peel oils, five monoterpene hydrocarbons (limonene, β-pinene, γ-terpinene, sabinene, and α-pinene) were present at the highest levels, followed by sesquiterpenes, aldehydes, and esters. The present experimental results demonstrate that Forner-Alcaide rootstocks (“FA5” > “FA517” > “FA13”) were the best rootstocks, leading to high content of volatile compounds, followed by C. aurantium and C. macrophylla. The order of total volatile contents was (in decreasing order): “Eureka” > “Bétera” > “Fino 95” > “Verna” > “Fino 49”. These results confirm that a strong relationship exists between the rootstock/scion combinations and the concentration of volatile compounds in the lemon peel oil. Aroma volatiles should be considered key parameters for the determination of rootstock-induced effects.

Author Contributions

M.G.A.-H. and P.S.-B. performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript; M.G.A.-H. and J.J.P.-P. analyzed the data; Á.A.C.-B. coordinated the study; F.H. and P.L. planned and designed the experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.FAOSTAT Production Lemons World’s. [(accessed on 24 September 2019)]; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QC.

- 2.Pérez A. Tonnes of Lemons Produced in Spain in 2018; Autonomous Community. [(accessed on 24 September 2019)]; Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/508962/producciones-de-limones-en-espana-por-comunidad-autonoma/

- 3.Dubey A., Sharma R. Effect of rootstocks on tree growth, yield, quality and leaf mineral composition of lemon (Citrus limon (L.) Burm.) Sci. Hortic. 2016;200:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2016.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin G., Tietel Z., Porat R. Effects of rootstock/scion combinations on the flavor of citrus fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:11286–11294. doi: 10.1021/jf402892p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lordan J., Fazio G., Francescatto P., Robinson T.L., II Horticultural performance of ‘Honeycrisp’ grown on a genetically diverse set of rootstocks under Western New York climatic conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2019;257:108686. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Continella A., Pannitteri C., La Malfa S., Legua P., Distefano G., Nicolosi E., Gentile A. Influence of different rootstocks on yield precocity and fruit quality of ‘Tarocco Scirè’ pigmented sweet orange. Sci. Hortic. 2018;230:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Molina E., Domínguez-Perles R., Moreno D.A., Garcia-Viguera C. Natural bioactive compounds of Citrus limon for food and health. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010;51:327–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molyneux R.J., Schieberle P. Compound identification: a journal of agricultural and food chemistry perspective. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:4625–4629. doi: 10.1021/jf070242j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.González-Mas M.C., Rambla J.L., López-Gresa M.P., Blázquez M.A., Granell A. Volatile compounds in citrus essential oils: A comprehensive review. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Legua P., Martinez-Cuenca M.R., Bellver R., Forner-Giner M.Á. Rootstock’s and scion’s impact on lemon quality in southeast Spain. Int. Agrophys. 2018;32:325–333. doi: 10.1515/intag-2017-0018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lado J., Gambetta G., Zacarias L. Key determinants of citrus fruit quality: metabolites and main changes during maturation. Sci. Hortic. 2018;233:238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.01.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Chen W.-K., Gao X.-T., He L., Yang X.-H., He F., Duan C.-Q., Wang J. Rootstock-Mediated Effects on cabernet sauvignon performance: vine growth, berry ripening, flavonoids, and aromatic profiles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:401. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamboa G.G., Garde-Cerdán T., Carrasco-Quiroz M., Del Alamo-Sanza M., Moreno-Simunovic Y., Pérez-Álvarez E.P., Gil A.M. Volatile composition of Carignan noir wines from ungrafted and grafted onto País (Vitis vinifera L.) grapevines from ten wine-growing sites in Maule Valley, Chile. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018;98:4268–4278. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barboni T., Muselli A., Luro F., Desjobert J.-M., Costa J. Influence of processing steps and fruit maturity on volatile concentrations in juices from clementine, mandarin, and their hybrids. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010;231:379–386. doi: 10.1007/s00217-010-1283-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourgou S., Rahali F.Z., Ourghemmi I., Tounsi M. Changes of peel essential oil composition of four Tunisian citrus during fruit maturation. Sci. World J. 2012;2012:1–10. doi: 10.1100/2012/528593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji X., Liu F., Shi X., Wang B., Liu P., Wang H. The effects of different training systems and shoot spacing on the fruit quality of ‘kyoho’ grape. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2019;52:1164–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lan Y., Qian X., Yang Z.-J., Xiang X.-F., Yang W.-X., Liu T., Zhu B.-Q., Pan Q.-H., Duan C.-Q. Striking changes in volatile profiles at sub-zero temperatures during over-ripening of ‘Beibinghong’ grapes in Northeastern China. Food Chem. 2016;212:172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baaliouamer A., Meklati B.Y., Fraisse D., Scharff C. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of petitgrain Eureka lemon essential oil by fused silica capillary column gas chromatography mass spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1985;36:1145–1154. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740361119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu Q., Huang N., Peng Y., Zhu C., Pan S. Peel oils from three Citrus species: Volatile constituents, antioxidant activities and related contributions of individual components. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;56:4492–4502. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03937-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y., Heying E., Tanumihardjo S.A. History, global distribution, and nutritional importance of citrus fruits. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012;11:530–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2012.00201.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forney C., Song J. Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2017. Flavors and aromas: chemistry and biological functions; pp. 515–540. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang B., Chen J., He Z., Chen H., Kandasamy S. Hydrothermal liquefaction of fresh lemon-peel: parameter optimization and product chemistry. Renew. Energy. 2019;143:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2019.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tekgül Y., Baysal T. Comparative evaluation of quality properties and volatile profiles of lemon peels subjected to different drying techniques. J. Food Process. Eng. 2018;41:e12902. doi: 10.1111/jfpe.12902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong S., Ren J., Chen D., Pan S., Wang K., Yang S., Fan G. Free and bound volatile compounds in juice and peel of Eureka lemon. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2014;20:167–174. doi: 10.3136/fstr.20.167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llosa M.J. Ph.D. Thesis. Polythecnic University of Valencia; Valencia, Spain: 2009. Evaluation of the Behavior of New Citrus Patterns against Ferric Chlorosis. [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Zaeddi H., Martínez-Tomé J., Calin-Sánchez Á., Burló F., Carbonell-Barrachina Á.A. Volatile composition of essential oils from different aromatic herbs grown in Mediterranean regions of Spain. Foods. 2016;5:41. doi: 10.3390/foods5020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis R.J. Hawley’s Condensed Chemical Dictionary. 15th ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2007. p. 998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bravo A., Hotchkiss J.H., Acree T.E. Identification of odor-active compounds resulting from thermal oxidation of polyethylene. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992;40:1881–1885. doi: 10.1021/jf00022a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benitez N.P., León E.M.M., Stashenko E. Essential oil composition from two species of Piperaceae family grown in Colombia. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2009;47:804–807. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/47.9.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed E.M., Dennison R.A., Dougherty R.H., Shaw P.E. Flavor and odor thresholds in water of selected orange juice components. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978;26:187–191. doi: 10.1021/jf60215a074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C., Cheng Y., Zhang H., Deng X., Chen F., Xu J. Volatile constituents of wild Citrus mangshanyegan (Citrus nobilis Lauriro) Peel Oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:2617–2628. doi: 10.1021/jf2039197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cano-Lamadrid M., Lipan L., Hernández F., Martínez J.J., Legua P., Carbonell-Barrachina Á.A., Melgarejo P. Quality Parameters, Volatile Composition, and Sensory Profiles of Highly Endangered Spanish Citrus Fruits. J. Food Qual. 2018;2018:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2018/3475461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Vaio C., Graziani G., Gaspari A., Scaglione G., Nocerino S., Ritieni A. Essential oils content and antioxidant properties of peel ethanol extract in 18 lemon cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2010;126:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2010.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lota M.-L., Serra D.D.R., Tomi F., Jacquemond C., Casanova J. Volatile Components of Peel and Leaf Oils of Lemon and Lime Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:796–805. doi: 10.1021/jf010924l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seker M., Ekinci N., Gür E. Effects of different rootstocks on aroma volatile constituents in the fruits of peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch cv. ‘Cresthaven’) N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2017;45:1–13. doi: 10.1080/01140671.2016.1223148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noguera-Artiaga L., Sánchez-Bravo P., Pérez-López D., Szumny A., Calin-Sánchez Á., Burgos-Hernandez A., Carbonell-Barrachina Á.A. Volatile, sensory and functional properties of HydroSOS pistachios. Foods. 2020;9:158. doi: 10.3390/foods9020158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ballesta M.M., Alcaraz-López C., Muries B., Mota-Cadenas C., Carvajal M. Physiological aspects of rootstock–scion interactions. Sci. Hortic. 2010;127:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2010.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]