Abstract

DDR1 is considered as a promising target for cancer therapy, and selective inhibitors against DDR1 over other kinases may be considered as promising therapeutic agents. Herein, we have identified a series of 3′-(imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxamides as novel selective DDR1 inhibitors. Among these, compound 8v potently inhibited DDR1 with an IC50 of 23.8 nM, while it showed less inhibitory activity against DDR2 (IC50 = 1740 nM) and negligible activities against Bcr-Abl (IC50 > 10 μM) and c-Kit (IC50 > 10 μM). 8v also exhibited excellent selectivity in a KINOMEscan screening platform with 468 kinases. This compound dose-dependently suppressed NSCLC cell tumorigenicity, migration, and invasion. Collectively, these studies support its potential application for treatment of NSCLC.

Keywords: DDR1, selective inhibitor, NSCLC, drug discovery, SAR

Discoidin domain receptors (DDR1 and DDR2), discovered by homology cloning in 1990s, are transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs).1,2 Unlike other RTKs, the endogenous ligands of DDRs are collagens.3,4 DDRs can undergo autophosphorylation to actively regulate basic cellular processes by collagen binding, e.g. differentiation, adhesion, proliferation, survival, and matrix remodeling.5−7 Earlier studies have indicated that DDRs may serve as potential targets of treating some diseases, such as fibrotic disorders, osteoarthritis, and cancers.8,9 For example, DDR1 was widely implicated in cell survival and invasiveness in a range of cancers, including lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and prostate cancer, etc.10,11 Overexpression or mutation of DDRs has also been detected in many cancer cell lines such as nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast cancer, and ovarian cancer.12−14 Experimental therapeutics targeting DDR1 by siRNA have indicated its potential to suppress tumorigenicity, inhibit lung cancer bone metastasis, and enhance cancer cell chemosensitivity.15−17 Consequently, DDR1 inhibitors could serve as new potential therapeutic agents for cancer treatment.9

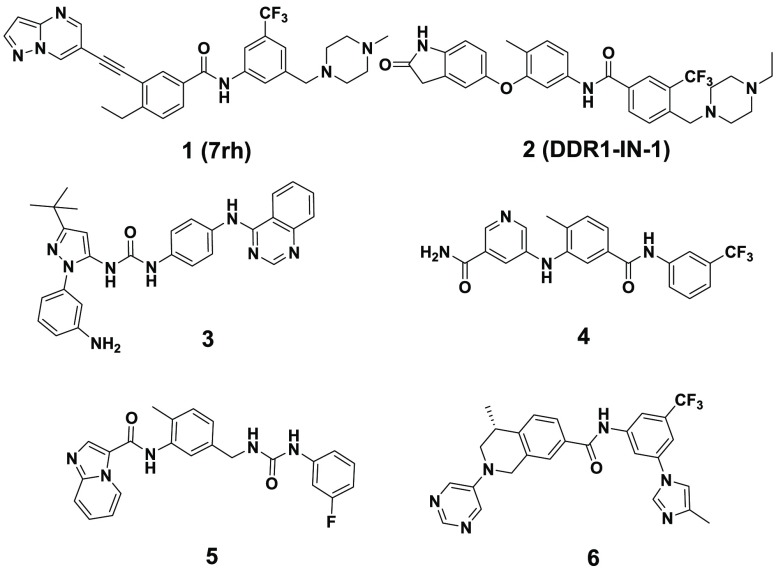

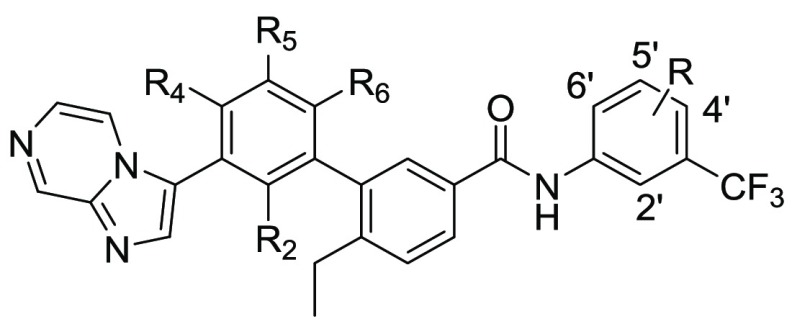

Numerous multikinase inhibitors have been reported to show good inhibitory activities against DDR1 and DDR2 functionality.9 However, few of them were developed primarily by targeting DDRs. During the recent five years, several selective DDR1 inhibitors were reported with various selectivity profiles (Figure 1).18−23 Compound 1 was the first reported by our laboratory as a promising DDR1-selective inhibitor for cancer therapy. However, its selectivity against DDR1 over DDR2 (14-fold) and Abl (52 fold) is still relatively inadequate.18 To further improve its selectivity profile, a series of 3′-(imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxamides were designed by featuring a novel substituted phenyl linker instead of the alkyne group in compound 1 and the nitrogen of imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine forming a critical hydrogen bond with Met704 of DDR1 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Structures of reported selective DDR1 inhibitors.

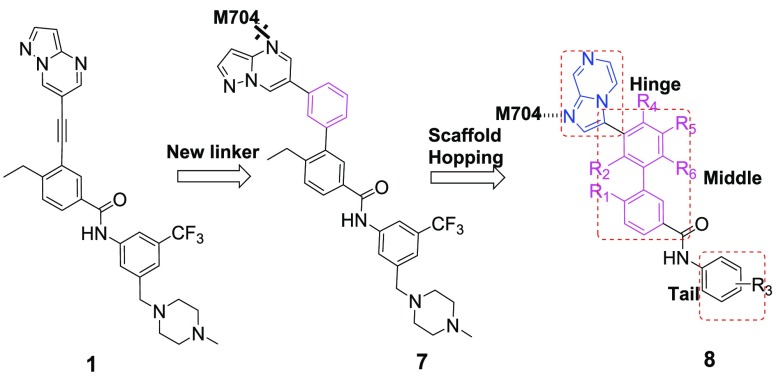

Figure 2.

Designing of new DDR1 inhibitors based on compound 1.

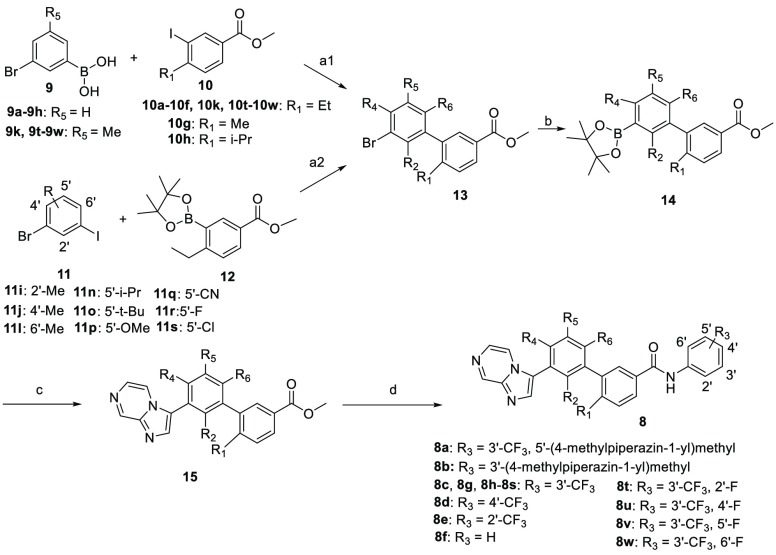

The title compounds were readily synthesized as described in Scheme 1. Substituted methyl 3′-bromo-[(1,1′-biphenyl)]-3-carboxylates 13 were prepared by coupling a substituted 3-bromophenylboronic acid 9 with substituted methyl 3-iodobenzoates 10 or by coupling substituted 1-bromo-3-iodobenzenes 11 with methyl 4-ethyl-3-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzoate (12). Compound 13 reacted with bis(pinacolato)diboron to give the intermediate 14, which underwent the classical Suzuki coupling reaction to yield the key substituted methyl 3′-(imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylates 15. The title compounds 8 were obtained through the amidation of the intermediate 15 with different anilines under basic conditions.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the Designed New DDR1 Inhibitors.

Reagents and conditions: (a1) Pd(PPh3)4, Na2CO3, PhMe/H2O (3:1), Ar, 90 °C, overnight, 58–98%; (a2) Pd(PPh3)4, K3PO4, dioxane, Ar, 90 °C, overnight, 55–91%; (b) Pd(dffp)Cl2, AcOK, Bis(pinacolato)diboron, dioxane, Ar, 90 °C, overnight, 64–92%; (c) Pd(PPh3)4, Na2CO3, PhMe/H2O (3:1), Ar, 90 °C, overnight, 42–82%; (d) t-BuOK, anilines, dry THF, −20 °C, 4–79%.

Our previous study indicated that 1 bound to the active pocket of DDR1 with a type II binding mode, and the alkynyl moiety served as a linking group for the pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine and the ethylbenzene.24 In our continuous efforts to improve its selectivity, the conformationally restricted bioisostere phenyl group of the alkynyl was first explored (Figure 2), similar to that of bioisostere triazol.25

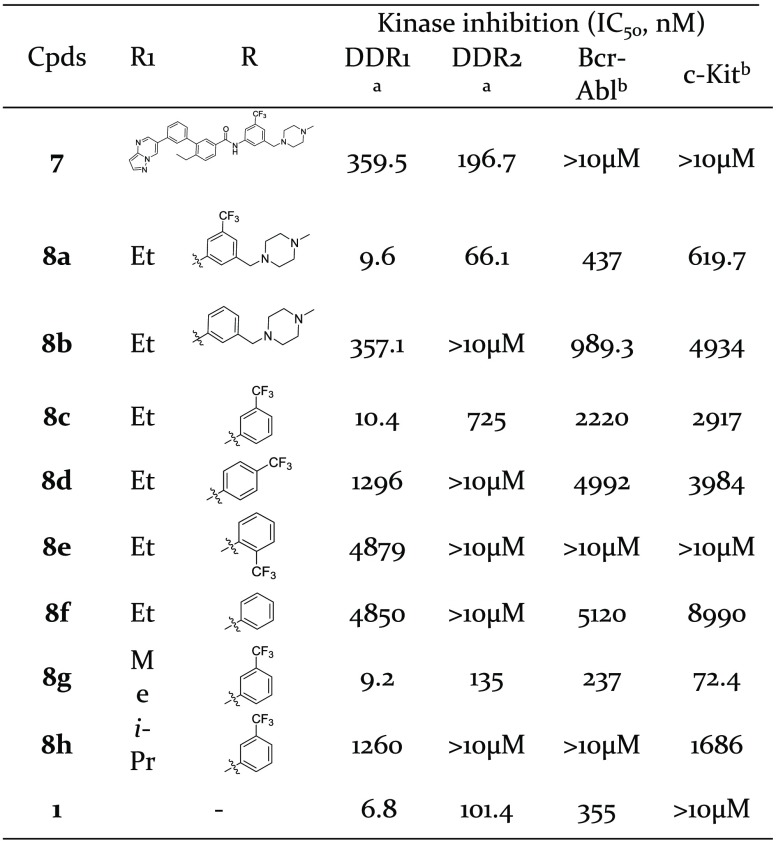

Starting with the simplest modification, compound 7 indeed improved the selectivity against Bcr-Abl and c-Kit, although it had about 50-fold decreased inhibitory activities against DDR1 and DDR2 (Table 1). In an investigation of the reason for the loss of activity, modeling studies suggested that compound 7 did not fit nicely into the DDR1 ATP binding pocket and could not achieve the essential hydrogen bond (HB) with Met704 in DDR1 (Figure 2). In view of the importance of the HB interactions in the hinge region of kinases, imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine was used as a privileged moiety to restore the key HB formed with Met704 of DDR1.26 Compound 8a exhibited 37-fold increased potency against DDR1 (IC50 = 8.7 nM), although its selectivity against other homologous kinases was unexpectedly decreased (Table 1).

Table 1. Kinase Inhibition of Compounds 7 and 8a–8h against DDR1, DRR2, Bcl-Abl, and c-Kit.

DDR1 and DDR2 inhibition were performed with the LanthaScreen Eu kinase assay.

Bcr-Abl and c-Kit inhibition were performed with the FRET-based Z′-Lyte assay. *Data means of three independent experiments, and the variations are <20%.

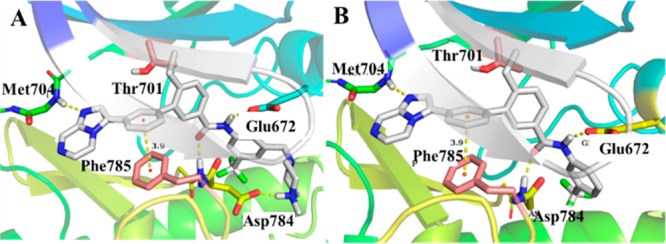

As a new scaffold for DDR1 inhibitor, compound 8a exhibited digital nM inhibitory activity against DDR1 and served as a promising lead molecule for further optimization. Further computational docking studies suggested that 8a bound to DDR1 with a classical type II bind mode (Figure 3A). The imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine moiety of 8a formed a critical HB with the Met704 of DDR1. The phenyl linker participated in an additional π–π interaction with Phe785, and this contributes greatly to its improved selectivity against Bcr-Abl and c-Kit. The amide of 8a also formed two HBs with Glu672 and Asp784 of DDR1, respectively. The modeling results suggested that the trifluoromethyl group of 8a was deeply bound in a DFG-out hydrophobic pocket and the 1-(4-methyl)piperazinyl moiety was extended to the solvent region of the protein. So, these two parts were first eliminated to investigate the contribution to DDR1 inhibitory activity, respectively.

Figure 3.

Binding modes of compounds 8a (A) and 8c (B) to DDR1 kinase (PDB: 4bkj). HBs and π–π interactions with key amino acids are indicated by yellow dotted lines.

Compound 8b in which R was replaced by 1-benzyl-4-methylpiperazine, showed a substantial potency loss toward DDR1 (IC50 = 357.1 nM), while compound 8c without the 1-(4-methyl)piperazinyl group was almost equally potent with 8a and had significantly improved selectivity over DDR2, Bcr-Abl, and c-Kit (Table 1). The results suggested the CF3 group is essential for the compounds to maintain DDR1 inhibitory activity and improve the selectivity over the aforementioned kinases. Moving the CF3 group to the ortho-(8d) or para-(8e) positions, or simply eliminating it (8f), totally negated the inhibitory activity against DDR1 kinase. The contribution of R1 substituents to the DDR1 potency and selectivity was also investigated. The methyl-substituted compound (8g) totally abolished the selectivity over DDR2, Bcr-Abl, and c-Kit (Table 1), although the inhibitory activity was maintained. The isopropyl-substituted compound (8h) also totally abolished the activity. These results clearly suggested that the R1 group, directed toward the gatekeeper Thr701 (Figure 3), played a crucial role in regulating kinase selectivity and activity.

Our previous study suggested that the π–π interaction between the phenyl linker of 8c and Phe785 contributed significantly to the selectivity against Bcr-Abl and c-Kit,23 and a detailed SAR study focusing on phenyl linker was undertaken. When a methyl group was added at the R2, R4, R5, or R6 position of 8c, the resulting compounds 8i–8l showed reduced inhibitory activity against DDR1 with IC50 values of 30.1, 107.8, 22.5, and 63.7 nM, respectively (Table 2). Although 8k, in which R5 was methyl, was about 2-fold less potent than 8c, it displayed superior selectivity over the other three kinases (DDR2, Bcr-Abl, and c-Kit). Next, we examined the contribution of the R5 substituent to the DDR1 inhibitory potency and selectivity. Obviously, as the bulk of the substituents increased, the potency against DDR1 decreased accordingly. For example, replacement of the R5-methyl with ethyl (8m), isopropyl (8n), or tert-butyl (8o) led to compounds with IC50 values of 42.3, 66.9, and 92 nM, respectively. Further study showed that this position was generally tolerant to both medium sized electron-donating and -withdrawing groups. For example, compounds with methoxy (8p), cyano (8q), fluorine (8r), and chlorine (8s) groups at this position exhibited IC50 values of 16.5, 15.6, 30.3, and 21.3 nM, respectively, against the DDR1 kinase, but the selectivity over DDR2, Bcr-Abl, and c-Kit was obviously decreased.

Table 2. Kinase Inhibition of Compounds 8i–8y against DDR1, DRR2, Bcr-Abl, and c-Kit.

| Kinase

inhibition (IC50, nM) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpds | R2 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R | DDR1a | DDR2a | Ablb | c-Kitb |

| 8i | Me | H | H | H | H | 30.1 | 663.5 | 1813 | 5978 |

| 8j | H | Me | H | H | H | 107.8 | >10 μM | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8k | H | H | Me | H | H | 22.5 | 1728 | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8l | H | H | H | Me | H | 63.7 | 610 | 1452 | >10 μM |

| 8m | H | H | Et | H | H | 42.3 | 3227 | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8n | H | H | i-Pr | H | H | 66.9 | 2631 | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8o | H | H | t-Bu | H | H | 92 | >10 μM | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8p | H | H | OMe | H | H | 16.5 | 1018 | 3696 | 4994 |

| 8q | H | H | CN | H | H | 15.6 | 947 | 5637 | 3721 |

| 8r | H | H | F | H | H | 30.3 | 1326 | 5345 | 6591 |

| 8s | H | H | Cl | H | H | 21.3 | 1080 | >10 μM | 8414 |

| 8t | H | H | Me | H | 2′-F | 73.8 | >5 μM | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8u | H | H | Me | H | 4′-F | 55.6 | >5 μM | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8v | H | H | Me | H | 5′-F | 23.8 | 1740 | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 8w | H | H | Me | H | 6′-F | 36.5 | >5 μM | >10 μM | >10 μM |

| 1 | 6.8 | 101.4 | 355 | >10 μM | |||||

DDR1 and DDR2 inhibition was performed with the LanthaScreen Eu kinase assay.

Bcr-Abl and c-Kit inhibition was performed with the FRET-based Z′-Lyte assay. *Data means of three independent experiments, and the variations are <20%.

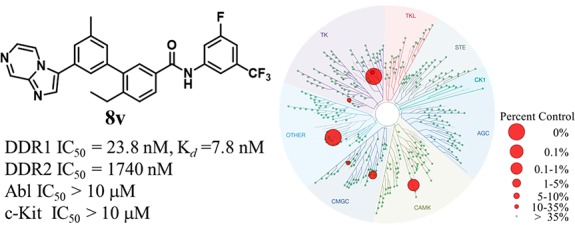

The fluorine atom is a bioisostere of hydrogen and can reduce the electrical properties of the phenyl group. We investigated the potential influence of the “tail phenyl” region of 8k by introducing a fluorine atom to the R position. The resulting 2′-F (8t), 4′-F (8u), and 6′-F (8w) compounds displayed decreased inhibitory activity against DDR1, while 5′-F (8v) exhibited a similar DDR1 inhibitory activity and selectivity to those of 8k. Compound 8v potently exhibited DDR1 inhibitory activity (IC50 = 23.8 nM) and also targeted selectivity over aforementioned kinases DDR2, Bcr-Abl, and c-Kit of 73-, 420-, and 420-fold, respectively.

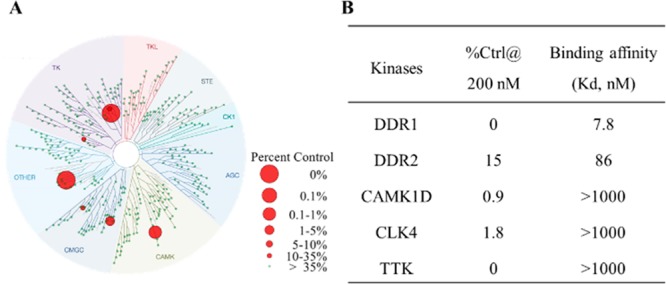

To further evaluate the selectivity of 8v over other kinases, a KINOMEscan screening platform with 468 kinases was conducted at DiscoveRx (San Diego, CA).27 The results demonstrated that 8v displayed extraordinary target selectivity (S-core (10) = 0.01 and S-core (1) = 0.007) (Figure 4A, Tables S1 and S2). The apparent “off-target” kinases included only DDR2, calcium dependent protein kinase ID (CAMK1D), CDC like kinase 4 (CLK4), and spindle assembly checkpoint kinase (TTK). The Kd values of 8v against the above “off targets” and DDR1 were further evaluated using DiscoveRx’s platform. The results showed that 8v tightly bound to DDR1 (Kd = 7.8 nM, Figure 4B), which was consistent with the in vitro kinase inhibitory activity. For potential “off-targets”, compound 8v had no detectable binding affinities to three apparent “off target” kinases (CAMK1D, CLK4, and TTK) at a >1 μM concentration except for DDR2 (Figure 4B). Although the Kd value of 8v to DDR2 appears to be as low as 86 nM, its IC50 value against DDR2 was 1739 nM in our kinase assay. In comparison, the IC50 value of compound 8v against DDR1 was determined to be 23.8 nM (73-fold selective). Taken together, these results suggested the extraordinary target selectivity of compound 8v against a panel of 468 kinases.

Figure 4.

KINOMEscan profiles of compound 8v. (A) KINOMEscan profiling of 8v at a concentration of 200 nM (25-fold Kd value) against 468 kinases. (B) Kd determination of compound 8v against DDR1 and the potential off targets.

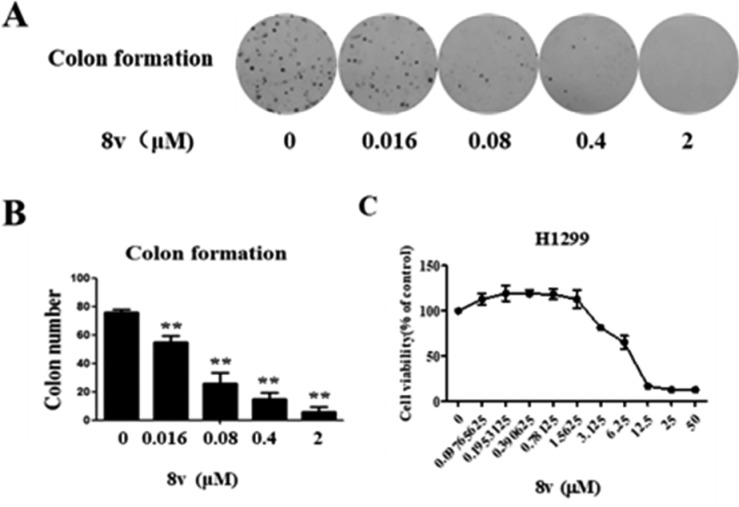

A previous study has shown that DDR1 inhibitors strongly suppress cancer tumorigenicity.18 The effect of 8v on the tumorigenicity of H1299 NSCLC cancer cells was first investigated by colony formation assay. The results demonstrated that compound 8v dose-dependently suppressed colony formation in H1299 NSCLC cancer cells after 10 continuous day treatment of cells with 8v (IC50 = 0.046 μM, Figures 5A and 5B). However, the direct antiproliferation of 8v against H1299 NSCLC cancer cells seemed to be moderate with an IC50 value of 6.6 μM (Figure 5C). It was suggested that compound 8v significantly suppressed the number of colony formations (not the size).

Figure 5.

Compound 8v suppresses H1299 NSCLC cell tumorigenicity and proliferation. (A) Compound 8v effectively inhibits H1299 NSCLC cell colony formation. (B) Quantitative result of Figure 5A. (C) Proliferation result of 8v evaluated with an CCK-8 assay. The data are means from three independent experiments.

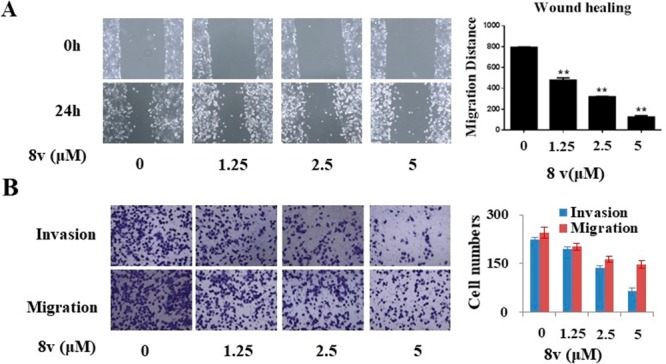

It has been reported that DDR1 plays important roles in tumor migration and invasion.18 The effect of 8v on the migration and invasion of H1299 NSCLC cancer cells was investigated using the wound healing assay and the transwell assay. As shown in Figure 6A, compound 8v suppressed wound closure in H1299 cells by 40%, 60%, and 84% at concentrations of 1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 μM, respectively, compared with blank control groups. Further, the study showed that 8v dose-dependently inhibits the invasion of H1299 cancer cells by 17%, 50%, and 71% at 1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 μM concentrations for 24 h, respectively (Figure 6B). These results clearly indicated that compound 8v can potentially suppress migration and invasion of H1299 NSCLC cancers.

Figure 6.

Compound 8v suppresses H1299 NSCLC cell migration and invasion. (A) Compound 8v inhibition of H1299 cell migration with wound healing assay. (B) Compound 8v inhibition of H1299 cell migration and invasion with transwell assay. The data are means from three independent experiments.

In summary, a series of 3′-(imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxamides were synthesized and investigated as highly selective DDR1 inhibitors. The comprehensive SARs study reported here led to the most promising compound 8v, which binds tightly to the DDR1 (Kd = 7.8 nM) and potently inhibits DDR1 kinase function (IC50 = 23.8 nM). Furthermore, 8v exhibits ideal target selectivity in KINOMEscan screen against the 468 kinases. Compound 8v also potently suppresses NSCLC cell tumorigenicity, invasion, and adhesion. However, the pharmacokinetic parameters of compound 8v are not ideal (T1/2 = 1.2 h and F = 3.9%). Further pharmacokinetics-oriented optimization of 8v is ongoing, and the results will be disclosed in due course. Collectively, compound 8v may be a promising lead compound for future studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81922062, 81874285, and 81820108029), National Key Research and Development Program of China (218YFE0105800), and Guangdong Province Science and Technology Program (2018A050506043) and Jinan University.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DDR1

discoidin domain receptor 1

- Kd

binding constant

- RTKs

receptor tyrosine kinases

- CF3

trifluoromethylphenyl

- CAMK1D

calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase ID

- NSCLC

nonsmall cell lung cancer

- CLK4

CDC like kinase 4

- SARstructure–activity relationshipTTK

structure–activity relationshipTTKspindle assembly checkpoint kinase

- DFG

Asp-Phe-Gly

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenytetrazolium bromide.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00495.

Synthetic procedures for compounds 8a–8w, results of the kinase selectivity profiling study of compound 8v, procedures for Kinomescan screening, in vitro kinase assay, colony formation assay, in vitro cell proliferation by MTT assay, wound healing, transwell assay, computational study, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds 8a–8w (PDF)

Author Contributions

# C.M., Z.Z., and Y.L. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Johnson J. D.; Edman J. C.; Rutter W. J. A receptor tyrosine kinase found in breast carcinoma cells has an extracellular discoidin I-like domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993, 90, 5677–5681. 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C.; Lemke G. Structure and expression of the Tyro 10 receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncogene 1994, 9, 877–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel W.; Gish G. D.; Alves F.; Pawson T. The discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinases are activated by collagen. Mol. Cell 1997, 1, 13–23. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitinger B. Molecular analysis of collagen binding by the human discoidin domain receptors, DDR1 and DDR2. Identification of collagen binding sites in DDR2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 16761–16769. 10.1074/jbc.M301370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H. L.; Valiathan R. R.; Arkwright R.; Sohail A.; Mihai C.; Kumarasiri M.; Mahasenan K. V.; Mobashery S.; Huang P.; Agarwal G.; Fridman R. Discoidin domain receptors: unique receptor tyrosine kinases in collagen-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 7430–7437. 10.1074/jbc.R112.444158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou G.; Vogel W. F.; Bendeck M. P. Tyrosine kinase activity of discoidin domain receptor 1 is necessary for smooth muscle cell migration and matrix metalloproteinase expression. Circ. Res. 2002, 90, 1147–1149. 10.1161/01.RES.0000022166.74073.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel W. F.; Abdulhussein R.; Ford C. E. Sensing extracellular matrix: an update on discoidin domain receptor function. Cell. Signalling 2006, 18, 1108–1116. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza C. M.; Pozzi A. Discoidin domain receptors in disease. Matrix Biol. 2014, 34, 185–192. 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Lu X.; Ren X.; Ding K. Small molecule discoidin domain receptor kinase inhibitors and potential medical applications. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3287–3301. 10.1021/jm5012319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K.; Nakamura M.; Ishida E.; Higuchi T.; Yamamoto H.; Tsujikawa K.; Konishi N. Prostate cancer antigen-1 contributes to cell survival and invasion through discoidin receptor 1 in human prostate cancer. Cancer Sci. 2007, 99, 39–45. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiathan R. R.; Marco M.; Leitinger B.; Kleer C. G.; Fridman R. Discoindin domain receptor tyrosine kinases: new players in cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012, 31, 295–321. 10.1007/s10555-012-9346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. E.; Lau S. K.; Zhu C. Q.; Andersson T.; Tsao M. S.; Vogel W. F. Expression and mutation analysis of the discoidin domain receptors 1 and 2 in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 808–814. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker K. T.; Martindale J. E.; Mitchell P. J.; Kamalati T.; Page M. J.; Phippard D. J.; Dale T. C.; Gusterson B. A.; Crompton M. R. Expression patterns of the novel receptor-like tyrosine kinase, DDR, in human breast tumors. Oncogene 1995, 10, 569–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan J.; Yahata T.; Adachi S.; Yoshihara K.; Tanaka K. Identification of receptor tyrosine kinase, discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1), as a potential biomarker for serous ovarian cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 971–982. 10.3390/ijms12020971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia K.; Ormazabal C.; Zandueta C.; Luis-Ravelo D.; Anton I.; Pajares M. J.; Agorreta J.; Montuenga L. M.; Martínez-Canarias S.; Leitinger B.; Lecanda F. Inhibition of collagen receptor discoidin domain receptor-1 (DDR1) reduces cell survival, homing and colonization in lung cancer bone metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 969–980. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.; Ongusaha P. P.; Yang Y. S.; Park J. M.; Aaronson S. A.; Lee S. W. Discoidin domain receptor 1 receptor tyrosine kinase induces cyclooxygenase-2 and promotes chemoresistance through nuclear factor-kappaB pathway activation. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 8123–8130. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. G.; Hwang S. Y.; Aaronson S. A.; Mandinova A.; Lee S. W. DDR1 receptor tyrosine kinase promotes prosurvival pathway through Notch1 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17672–17681. 10.1074/jbc.M111.236612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Gao M.; Duan L.; Luo J.; Zhang L.; Lu X.; Zhang Y.; Zhang Z.; Tu Z.; Xu Y.; Ren X.; Ding K. Discovery and optimization of 3-(2-(Pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyn yl)benzamides as novel selective and orally bioavailable discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3281–3295. 10.1021/jm301824k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. G.; Tan L.; Weisberg E. L.; Liu F.; Canning P.; Choi H. G.; Ezell S. A.; Wu H.; Zhao Z.; Wang J.; Mandinova A.; Griffin J. D.; Bullock A. N.; Liu Q.; Lee S. W.; Gray N. S. Discovery of a potent and selective DDR1 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2145–2150. 10.1021/cb400430t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richters A.; Nguyen H. D.; Phan T.; Simard J. R.; Grutter C.; Engel J.; Rauh D. Identification of type II and III DDR2 inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4252–4262. 10.1021/jm500167q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai H.; Tan L.; Beauchamp E. M.; Hatcher J. M.; Liu Q.; Meyerson M.; Gray N. S.; Hammerman P. S. Characterization of DDR2 inhibitors for the treatment of DDR2 mutated non-small cell lung cancer. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2687–2696. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. W.; Berdini V.; Buck I. M.; Carr M. E.; Cleasby A.; Coyle J. E.; Curry J. E.; Day J. E.; Day P. J.; Hearn K.; Iqbal A.; Lee L. Y.; Martins V.; Mortenson P. N.; Munck J. M.; Page L. W.; Patel S.; Roomans S.; Smith K.; Tamanini E.; Saxty G. Fragment-based discovery of potent and selective DDR1/2 Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 798–803. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Bian H.; Bartual S. G.; Du W.; Luo J.; Zhao H.; Zhang S.; Mo C.; Zhou Y.; Xu Y.; Tu Z.; Ren X.; Lu X.; Brekken R. A.; Yao L.; Bullock A. N.; Su J.; Ding K. Structure-based design of tetrahydroisoquinoline-7-carboxamides as selective discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 5911–5916. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang Y.; Pinkas D. M.; Fox A. E.; Luo J.; Huang H.; Cui S.; Xiang Q.; Xu T.; Xun Q.; Zhu D.; Tu Z.; Ren X.; Brekken R. A.; Bullock A. N.; Liang G.; Ding K.; Lu X. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of 3-(Imidazo[1,2- a]pyrazin-3-ylethynyl)-4-isopropyl- N-(3-((4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)benzamide as a Dual Inhibitor of Discoidin Domain Receptors 1 and 2. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 7977–7990. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Shen M.; Zhang Z.; Luo J.; Pan X.; Lu X.; Long H.; Wen D.; Zhang F.; Leng F.; Li Y.; Tu Z.; Ren X.; Ding K. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10033–10046. 10.1021/jm301188x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang Y.; Bartual S. G.; Luo J. F.; Xu T.; Du W.; Xun Q.; Tu Z.; Brekken R. A.; Ren X.; Bullock A. N.; Liang G.; Lu X.; Ding K. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-7-carboxamide derivatives as new selective discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1) Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 327–332. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian M. A.; Biggs W. H. 3rd; Treiber D. K.; Atteridge C. E.; Azimioara M. D.; Benedetti M. G.; Carter T. A.; Ciceri P.; Edeen P. T.; Floyd M.; Ford J. M.; Galvin M.; Gerlach J. L.; Grotzfeld R. M.; Herrgard S.; Insko D. E.; Insko M. A.; Lai A. G.; Lelias J. M.; Mehta S. A.; Milanov Z. V.; Velasco A. M.; Wodicka L. M.; Patel H. K.; Zarrinkar P. P.; Lockhart D. J. A small molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 329–336. 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.