Abstract

The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology. For additional information, and a full list of learning objectives for all three competencies, see http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289517715040.1

Keywords: pathology competencies, organ system pathology, hepatobiliary, molecular basis of biliary neoplasia, gallbladder, adenocarcinoma, morphology, clinical features

Primary Objective

Objective HB5.1: Extrahepatic Biliary Carcinoma. Describe the epidemiology, morphology, and clinical features of gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract carcinoma.

Competency 2: Organ System Pathology; Topic: (HB) Hepatobiliary; Learning Goal 5: Molecular Basis of Biliary Neoplasia.

Patient Presentation

A 54-year-old female presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain for 2 days. Initially, the pain was not constant but has become so with several episodes of nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting. The pain is severe, sharp, and constant right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain radiating to her right back. She has experienced similar, but much less severe abdominal pain for the last 3 years. She does not report fevers, dysuria, diarrhea, hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, fevers, chills, focal numbness, weakness, or weight loss. Her past medical history is significant for obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 1

Physical examination revealed stable vital signs temperature oral 37.0°C, heart rate 93 bpm, respiratory rate, 22 br/min, and blood pressure 191/96 mm Hg. Patient was alert and in pain but no acute distress. Cardiovascular and respiratory system were unremarkable. Abdominal examination showed epigastric and RUQ severe tenderness (Murphy sign) without jaundice or organomegaly. Referred pain to RUQ when palpating lower quadrants bilaterally without guarding or rebound. Other systems were unremarkable.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part 1

What Is in the Differential Diagnosis for an Acute Right Upper Quadrant Abdominal Pain?

Right upper quadrant pain is a common complaint with a very broad differential list including diseases mainly from biliary (colic, cholelithiasis, acute cholecystitis, and acute cholangitis), liver (acute hepatitis, perihepatitis, abscess, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and portal vein thrombosis), bowel (Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and colitis), pulmonary (pneumonia and embolus), and renal (nephrolithiasis and pyelonephritis).

In the present case, evaluation of the gallbladder (GB) is particularly important because cholelithiasis (and its complications) is one of the most common causes of RUQ pain. Gallstones are present in ∼10% of the general population.2 In addition to GB disease, liver diseases can potentially produce RUQ pain and should be strongly considered. Based on the patient’s symptoms and signs, cholelithiasis and acute cholecystitis are at the top of the differential list.

What Is the Role of Ultrasound, Scintigraphy, and Computed Tomography in Right Upper Quadrant Pain Workup?

Abdominal ultrasound test is the primary imaging modality for evaluation of RUQ pain. It is more effective at diagnosing and evaluating gallstones than any other imaging test. Sonography is similar in accuracy to scintigraphy in the evaluation of suspected acute cholecystitis and provides additional information that is not available on scintigraphy. For cholescintigraphy test, as known as Hepatobiliary IminoDiacetic Acid (HIDA) scan, a radioactive chemical is injected intravenously into the patient and the test chemical is removed from the blood by the liver and secreted into the bile and then disperses everywhere that the bile goes into including the GB. A “camera” detects radioactivity and create a “picture” of the liver, bile ducts, GB, and surrounding areas. HIDA is a valuable test of GB function that is very useful in the evaluation of suspected acute cholecystitis when ultrasound is indeterminate. Computed tomography (CT) is not a primary modality in the evaluation of RUQ pain but is very useful in further evaluating complicated cholecystitis and GB neoplasm. Computed tomography may be useful in the diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 2

The patient underwent an ultrasound of the GB as shown in Figure 1 (shadowing gallstones seen and the largest one is about 43 mm in greatest diameter). Abdominal ultrasound revealed cholelithiasis and biliary sludge with GB wall thickening and a positive sonographic Murphy sign, concerning for acute cholecystitis with cholelithiasis. Borderline hepatomegaly was seen.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image shows shadowing gallstones. The largest gallstone (green arrows) is about 43 mm in greatest diameter as labeled in the picture. Combined with patient’s clinical features, the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis and cholelithiasis was made.

The patient also underwent an abdominal CT scan. The abdominal CT revealed trace amount of pericholecystic and periportal fluid without visualized calcified stone in the GB or biliary ducts which suggested further evaluation with an RUQ ultrasound if clinically concerned for cholecystitis. Hepatomegaly was found.

These 2 reports reflect the roles of abdominal CT and ultrasound in the evaluation of RUQ pain due to GB disorder.

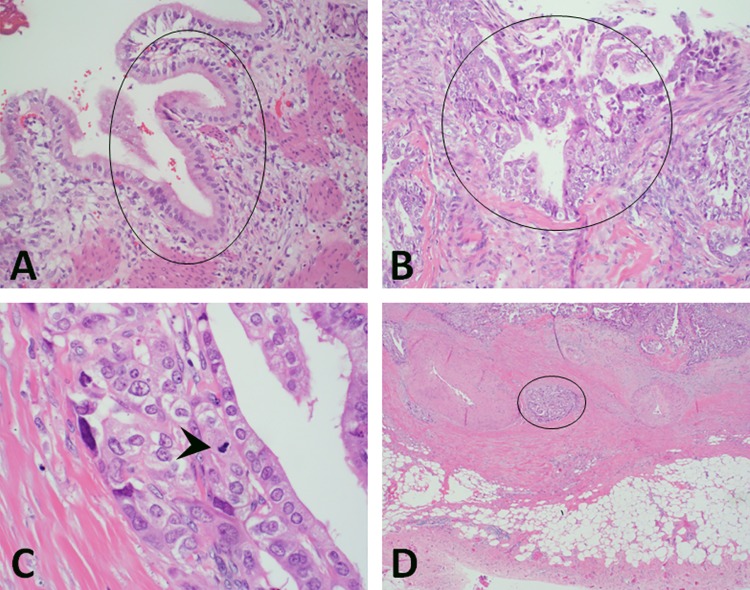

Patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy the next day after admission and recovered well postoperatively, stable for discharge after 2 days. However, pathologic gross examination of the surgical specimen GB revealed multiple black hard faceted gallstones and a firm 1.2 × 1.0 × 0.8 cm3 mass on the lateral fundus involving the muscularis propria layer. The histologic findings are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Histology features of gallbladder adenocarcinoma and uninvolved mucosa. A, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), ×200, normal mucosa (black circle) showing a single layer of columnar epithelium. The columnar epithelial cells have lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are aligned at the cell base or slightly more centrally. Nucleoli are absent or very small and inconspicuous; (B) H&E, ×200, adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder specimen (black circle) showing pleomorphic cells, pseudostratified nuclei, and distorted glands. C, Hematoxylin and eosin, ×600, mitosis (black arrow head) in the adenocarcinoma cells; (D) H&E, ×100, one nest of adenocarcinoma cells (black circle) invading the muscularis propria layer of the gallbladder.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part 2

What Is the Morphological Features of Gallbladder Carcinoma?

Histological examination demonstrated moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the GB. Most tumor glands with wide lumina were lined by few layers of highly atypical cuboidal cells, surrounded by a dense cellular stroma. The cytoplasm may be eosinophilic or pale, and almost clear or foamy (Figure 2B and C). The carcinoma infiltrated the fundus wall locally but was confined within the serosa (Figure 2D). The liver margin was negative for carcinoma cells, while tumor invaded perimuscular connective tissue on the peritoneal side without involvement of the serosa (visceral peritoneum). The remainder of the GB mucosa showed changes of acute and chronic cholecystitis.

What Is the Next Step for Evaluation of This Specimen?

Immunohistochemistry stains were needed to determine whether the mass is GB primary or metastatic tumor from other origin. Both P53 and CK7 are positive supporting the diagnosis of GB adenocarcinoma (Figure 3B and C, ×400). Proliferation index by Ki67 immunohistochemistry stain was high which indicates the tumor cells are dividing fast (Figure 3D, ×100). These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of GB adenocarcinoma.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry features of gallbladder adenocarcinoma. A, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), adenocarcinoma showing pleomorphic cells and distorted glands; (B) positive staining of P53 in tumor cells nuclei (brown color, ×400); (C) positive staining of CK7 in tumor cells’ cytoplasm (brown color, ×400); (D) IHC stain of Ki67, showing high proliferative index of tumor cells (brown color, nuclei staining, ×100).

What Is the Next Step for Evaluation of This Patient?

The pathological findings mandated a follow-up workup for possible metastatic tumor. Multiphase CT on liver revealed a 1.5-cm low-density hepatic lesion on arterial phase images. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple low-density hepatic lesions, concerning for metastatic GB carcinoma. Computed tomography-guided biopsy of the low-density hepatic lesion demonstrated metastatic poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The patient was started on appropriate chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin immediately.

What Is the Prevalence and Risk Factors of the Gallbladder Carcinoma?

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) is an aggressive disease with common local invasion and frequent distant metastases. There are more than 1000 new cases GBC each year in the United States.3 Of all, 70% of GBCs are in women, 64% GBC is diagnosed in Caucasians, 17% in Hispanics, 9% in African Americans, and 2% in Asian/Pacific Islanders.4,5 Although GBC is a rare cause of malignancy in the Western countries, it continues to be a significant source of mortality in Japan, India, and Chile, among other countries.6 The growing incidence of GBC may be partial due to the popularity of laparoscopic cholecystectomies and approximately 0.7% of laparoscopic cholecystectomies are found to have GBC.4

The most significant risk factors for development of GBC are female sex, advanced age, cholelithiasis, or other benign GB pathology,4,7 chronic infection with Salmonella species or Helicobacter pylori, anomalous pancreatobiliary duct junction, porcelain GB, GB polyps, and obesity.7 In patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for presumed benign disease, risk factors for finding incidental GBC include female sex,7 older age,7 jaundice,7 acute cholecystitis,7 dilated bile ducts,8 or GB wall thickening.8

What Are the Clinicopathologic Features of the GB Carcinoma?

As reported, clinical presentation of adenocarcinoma is vague and nonspecific.9,10 In the present case, cancer was found incidentally as acute and chronic cholecystitis with cholelithiasis expected. Most of the patients are 50 years of age or older at the time of diagnosis in the United States.3 Most common site of these tumors was the fundus and association with gallstones.9

These GB tumors are usually silent in initial stages and are detected in advanced stages. The early stage of the adenocarcinoma of GB presents with nonspecific symptoms or is asymptomatic, as in the present adenocarcinoma case which was diagnosed incidentally after laparoscopic cholecystectomy clinically due to cholecystitis with cholelithiasis.7 Most cases of GB adenocarcinoma are preceded by a sequence of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and carcinoma in situ.

What Is Known About the Molecular Basis in GBC?

In addition to environmental, microbial, and metabolic factors, GBC pathogenesis is also associated with molecular modulations. Molecular study on GBC includes cytokines/inflammatory factors in tumorigenesis, biomarkers for early diagnosis, molecules/pathways as treatment targets, and genetic alterations associated with prognosis. For example, chronic inflammation of GB due to presence of gallstone or microbial infection (eg, Salmonella or H. pylori) results in sustained production of inflammatory mediators in the tissue microenvironment, which can cause genomic changes linked to carcinogenesis. High throughput Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) are also used to determine genetic mutations in GB cancer.11 Gallbladder carcinoma develops through accumulation of multiple genetic alterations, involving oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and DNA repair genes. Among other common molecular alterations, KRAS mutations and inactivation of TP53 are the 2 main genetic changes associated with GB tumor.12 Different agents against molecular mutations targeting therapy are being tried, although there is dismal improvement in the survival of patients with GBC.13,14 Most recently, the role of DNA methylation in GBC is being studied for clinical implication and future prospects of biomarker development for early diagnosis and therapeutic interventions.15

What Is Known About The Metastatic Features of the GB Carcinoma?

Mechanism of spread of these tumors includes early metastasis as well as extension from the primary, as patients with adenocarcinoma typically present at an advanced stage.16 The present case is negative for tumor involvement of the GB liver-bed, but multiple metastases found in the liver lobes which confirmed by CT-guided biopsy. This suggests that lymphocytic or blood borne metastases could happen before the tumor direct invasion to the surrounding organs. The high risk patients may benefit from chemotherapy before resection.10

Teaching Points

Adenocarcinoma of the gall bladder is uncommon and found in approximately 0.7% of laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

Adenocarcinoma of the GB is usually silent in initial stages and often present at an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis.

Most cases of GB adenocarcinoma are preceded by a sequence of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and carcinoma in situ.

Although the exact etiology remains unknown, environmental, microbial, metabolic, and molecular factors are associated with GB carcinoma pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

KRAS mutations and inactivation of TP53 are the 2 main genetic changes associated with GB tumor.

Lymphatic or hematogenous metastases can occur before the tumor directly invades into the surrounding organs.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The article processing fee for this article was funded by an Open Access Award given by the Society of ‘67, which supports the mission of the Association of Pathology Chairs to produce the next generation of outstanding investigators and educational scholars in the field of pathology. This award helps to promote the publication of high-quality original scholarship in Academic Pathology by authors at an early stage of academic development.

References

- 1. Knollmann-Ritschel BEC, Regula DP, Borowitz MJ, Conran R, Prystowsky MB. Pathology Competencies for Medical Education and Educational Cases. Acad Pathol. 2017;4:1–36. doi:10.1177/2374289517715040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hopper KD, Landis JR, Meilstrup JW, McCauslin MA, Sechtin AG. The prevalence of asymptomatic gallstones in the general population. Invest Radiol. 1991;26:939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lau CSM, Zywot A, Mahendraraj K, Chamberlain RS. Gallbladder carcinoma in the United States: a population based clinical outcomes study involving 22,343 patients from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end result database (1973-2013). HPB Surg. 2017;2017:1532835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hickman L, Contreras C. Gallbladder cancer: diagnosis, surgical management, and adjuvant therapies. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99:337–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, Yadav A, Kumar A. Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and molecular genetics: recent update. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:3978–3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aloia TA, Jarufe N, Javle M, et al. Gallbladder cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koshenkov VP, Koru-Sengul T, Franceschi D, Dipasco PJ, Rodgers SE. Predictors of incidental gallbladder cancer in patients undergoing cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder disease. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rakić M, Patrlj L, Kopljar M, et al. Gallbladder cancer. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3:221–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherkassky L, D’Angelica M. Gallbladder cancer: managing the incidental diagnosis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2019;28:619–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mehrotra R, Tulsyan S, Hussain S, et al. Genetic landscape of gallbladder cancer: global overview. Mutat Res. 2018;778:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bal MM, Ramadwar M, Deodhar K, Shrikhande S. Pathology of gallbladder carcinoma: current understanding and new perspectives. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:509–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sicklick JK, Fanta PT, Shimabukuro K, Kurzrock R. Genomics of gallbladder cancer: the case for biomarker-driven clinical trial design. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35:263–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mishra SK, Kumari N, Krishnani N. Molecular pathogenesis of gallbladder cancer: an update. Mutat Res. 2019;816-818:111674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muhammad JS, Khan MR, Ghias K. DNA methylation as an epigenetic regulator of gallbladder cancer: an overview. Int J Surg. 2018;53:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dwivedi AN, Jain S, Dixit R. Gall bladder carcinoma: aggressive malignancy with protean loco-regional and distant spread. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:231–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]