Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease resulting in dementia. It is characterized pathologically by extracellular amyloid plaques composed mainly of deposited Aβ42 and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles formed by hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Recent clinical trials targeting Aβ have failed, suggesting that other polypeptides produced from the amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) may be involved in AD. An attractive polypeptide is AICD57, the longest APP intracellular domain (AICD) coproduced with Aβ42. Here, we show that AICD57 forms micelle-like assemblies that are proteolyzed by insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), indicating that AICD57 monomers are in dynamic equilibrium with AICD57 assemblies. The N-terminal part of AICD57 monomer is not degraded, but its C-terminal part is hydrolyzed, particularly in the YENPTY motif that has been associated with the hyperphosphorylation of tau. Therefore, sustaining IDE activity well into old age holds promise for regulating levels of not only Aβ but also AICD in the aging brain.

Keywords: Amyloid-β protein, amyloid-β precursor protein intracellular domain, insulin-degrading enzyme, CTF57

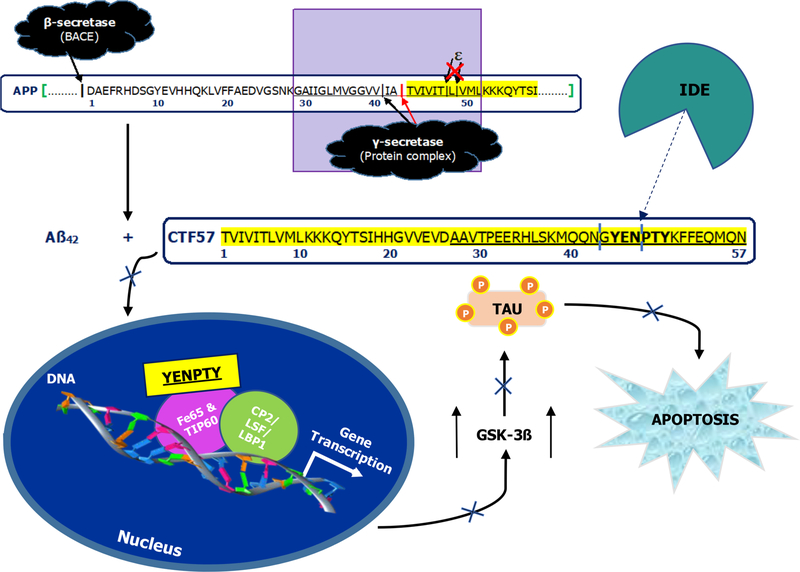

Graphical Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized clinically by progressive impairment of cognitive skills. Diagnostic lesions of AD include neuritic plaques composed mainly of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, primarily Aβ42, and neurofibrillary tangles made up of assemblies of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, AD currently affects approximately 5.7 million Americans, but by 2050, this number is projected to increase to 14 million.1 The leading hypothesis for the onset of AD is the amyloid-β oligomer hypothesis, discussed in recent reviews.2,3 According to this hypothesis, neurodegeneration leading to AD is initiated by soluble Aβ oligomers, primarily formed by Aβ42. However, after years of research on Aβ, there remains no cure for AD.4 Recent failures of clinical trials for potential drugs targeting Aβ can be understood if other polypeptides form oligomers that contribute to AD pathology and if tangle formation by hyperphosphorylated tau is the major pathological event leading to AD.3,4 If these are true, an attractive target is the amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) intracellular domain (AICD), which is coproduced with Aβ5,6 and has been linked to tau pathology.7–10

AICD is understudied relative to Aβ, but recent studies have shown its biological relevance. Two forms of AICD are produced by presenilin-mediated cleavage of APP: AICDε, produced by ε-site cleavage, and AICDγ, produced by γ-site cleavage. Following its release into the cytoplasm, AICD migrates to the nucleus, where it may have pathogenic transcriptional activity associated with AD,9–13 Parkinson’s disease (PD),14 and Down’s syndrome.15 In AD, AICD together with Fe65 and Tip60 form a ternary complex that interacts with transcription factors (i.e., CP2/LSF/LBP1) to increase the production of its precursor (i.e., APP)8 and alter the expression of other genes.16 For example, Kim and co-workers showed that AICD induces GSK-3β expression.7 Increased production of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) triggers tau hyperphosphorylation leading to neurofibrillary tangle formation and apoptosis.7–10

Although production and function are similar across AICDs, AICDε has received more attention than AICDγ. Recent studies of some mutations in APP and presenilin associated with AD indicate, however, that impairment of ε-site cleavage in APP may be a common feature in AD.17–20 AICD57, also known as CTF57 (i.e., the 57-amino-acid C-terminal fragment of APP), is one product of impaired ε-cleavage. Because it is contiguous to Aβ42, it is the longest form of AICD associated with the production of Aβ42. Intriguingly, mutations in APP and presenilin increase the Aβ42/Aβ40 concentration ratio,21 suggesting that if ε-cleavages are impaired, AICD57 levels are increased.

In this study, we determined (1) the global conformation of AICD57 in solution and (2) whether AICD57 is degraded by insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), one of the key proteases implicated in the degradation of Aβ.3,22 IDE is a 110-kDa, Zn2+ metalloprotease that also degrades glucagon, amylin, and other monomeric substrates having a size (less than 80 amino acids) that fits in the crypt of IDE (aka catalytic chamber).23,24 IDE’s crypt (~15700 Å3)25 is composed of negative N- and positive C-terminal halves connected by a flexible linker.23,24 The N-terminal half contains a highly conserved exosite ~30 Å away from a catalytically active E111 and a HXXEH motifcoordinated Zn2+. Although the exact mechanism remains unknown, it has been proposed that the anchoring of the substrate’s N-terminus to the exosite promotes cleavage by E111, with the open and closed states of IDE in equilibrium.24 Since elevated AICD levels are present in both human AD brains9 and IDE-deficient mice,26,27 we hypothesize that AICD degradation is hindered in AD and IDE is partly responsible for its clearance. In contrast to AICD50, the main AICD species in the normal human brain,13 which is completely degraded by IDE,26–29 our results show that AICD57 is only partially degraded by IDE due to the presence of β-sheet. Nonetheless, IDE cleaves AICD57 at the 6-amino-acid recognition motif, YENPTY, which is conserved in all species and has been implicated in the pathogenic function of the AICDs.

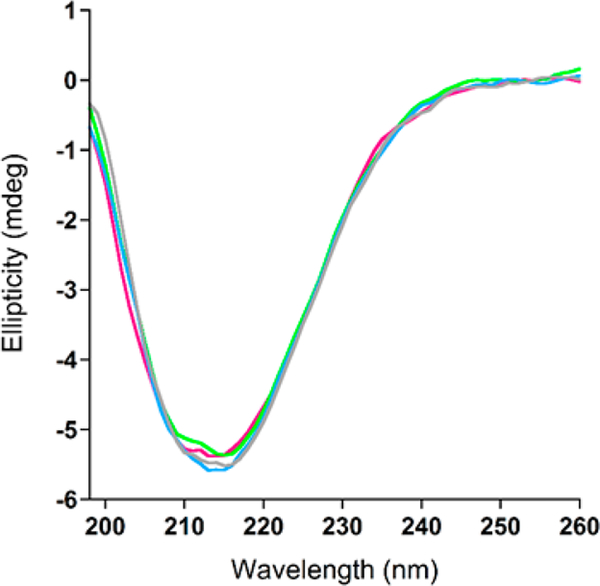

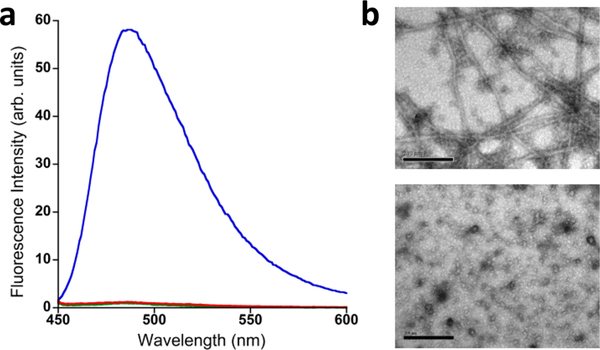

Our first aim was to characterize the global conformation of AICD57 in solution, which we accomplished using circular dichroism spectroscopy (CD). Figure 1 presents CD spectra of AICD57. The spectrum recorded immediately after sample preparation shows a minimum at 215 nm, indicating the dominant presence of β-sheet.30 Interestingly, the spectrum of AICD57 did not change with time. We did not observe an increase in the ellipticity at 215 nm that would have indicated an increase in β-sheet content nor did we observe a decrease in the ellipticity at 215 nm that would have indicated precipitation of large β-sheet-containing assemblies. We characterized the CD samples by thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence and noted that they are ThT negative, that is, the samples did not enhance the fluorescence of ThT (Figure 2a), indicating the absence of assemblies that contain cross-β-sheet,31,32 the quaternary structure present in protofibrillar and fibrillar β-sheet assemblies. Indeed, images obtained by TEM showed the absence of protofibrils and mature fibrils. However, micelle-like assemblies with an average diameter of ~15 nm were observed (Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

AICD57 contains stable β-sheet. Circular dichroic spectra of AICD57 (20 μM) recorded immediately after sample preparation (magenta) and after 6 h (green), 22 h (blue), and 6 days (gray) of incubation in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4).

Figure 2.

AICD57 forms assemblies that are ThT negative. (a) Fluorescence spectra of ThT only (green, negative control), ThT in the presence of AICD57 (red), and ThT in the presence of fibrils from hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL) (blue, positive control). (b) Electron micrograph of fibrils formed by HEWL (top). The fibrils have an average diameter of 38 nm. Electron micrograph of AICD57 (bottom). Micelle-like assemblies with an average diameter of 15 nm were observed. The scale bars in panel b correspond to 200 nm.

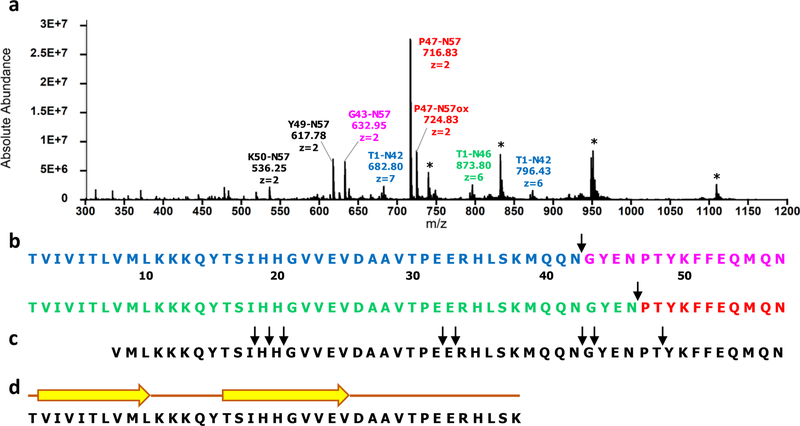

Given that the preexisting literature provides evidence for the complete degradation of AICD50 by IDE28,29 and given the results of our first aim, we next hypothesized that AICD57 is less susceptible to IDE-dependent degradation. To test this hypothesis, we used a combination of limited proteolysis monitored by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LP–LC/MS) and CD. We have successfully used LP–LC/MS to elucidate the fold of monomeric states of amyloidogenic peptides including Aβ33 and amylin.34 By applying the conditions for LP35 (i.e., substrate-to-enzyme molar ratios ≥100:1, digestion temperature of 4 °C, and short digestion times), the initial cleavage site(s) in the substrate can be unambiguously identified. This in turn can be used as a constraint in deciphering the orientation of the substrate in IDE’s crypt. Figure 3a presents the mass spectrum of AICD57 after incubation with IDE for 1 min. Fragments T1–N42 and T1–N46 were detected, along with G43–N57 and P47–N57. These data indicate initial cleavage sites at the peptide bonds between Asn42 and Gly43 and Asn46 and Pro47, respectively, both in the C-terminal part of AICD57 (Figure 3b, Table 1). In contrast, the initial cleavages in AICD50 were found in both N- and C-terminal parts of the polypeptide29 (Figure 3c), showing that AICD50 is more susceptible to IDE-dependent degradation, presumably because it is less structured than AICD57. Small amounts of Y49–N57 and K50–N57 were also detected in the spectrum of the 1 min digest of AICD57, but because peaks corresponding to their N-terminal halves were not observed, these fragments may have resulted from secondary cleavages in the G43–N57 and P47–N57 fragments. A similar digestion pattern of AICD57 was observed at longer digestion times (Figure S1, Tables S1–S4) in that the same primary cleavage sites were detected and short C-terminal fragments have the highest intensities relative to the longer N-terminal fragments. Additionally, no peaks consistent with secondary cleavages in the N-terminal fragments T1–N42 and T1–N46 were detected (Figure S1, Tables S1–S4), indicating that these fragments are resistant to IDE-dependent proteolysis. CD spectra of the reaction mixture acquired as a function of digestion time show that the β-sheet structure in AICD57 remains intact (Figure S2). Taking together our CD (Figures 1 and S2), ThT fluorescence (Figure 2a), TEM (Figure 2b), and LP–LC/MS results (Figure 3a–c) leads to the following conclusions. First, AICD57 monomer is only partially degradable by IDE in that its N-terminal part is resistant to hydrolysis while its C-terminal part is degraded. Second, because IDE is only able to degrade monomeric substrates with less than 80 residues,23,24 it follows that AICD57 monomers are in dynamic equilibrium with oligomeric assemblies of AICD57, that is,

Figure 3.

AICD57 is less susceptible to IDE-dependent proteolysis than AICD50. (a) Mass spectrum of AICD57 after incubation with IDE for 1 min. The fragment peaks are labeled by their identity (color coded if resulting from an initial cleavage), mass to charge ratio (m/z), and charge state (z). Peaks of undigested AICD57 are labeled with asterisks. (b) Peptide maps of AICD57 show two initial cleavage sites at the Asn42–Gly43 and Asn46–Pro47 peptide bonds. (c) Peptide map of AICD50 obtained by Venugopal and co-workers29 shows 8 initial cleavage sites including 3 near its N-terminus, 2 near the middle, and 3 near its C-terminus. (d) Structure prediction of the proteolytically resistant fragment of AICD57 (see text) using PSIPRED37 indicates the presence of two β-strands

Table 1.

Initial Cleavage Sites in AICD57 Determined by Limited Proteolysis Experiments Using IDE

| cleavage site | fragment | observed mass (Da) | theoretical mass (Da) | δ (observed mass – theoretical mass, Da) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asn42–Gly43 | T1–N42 | 4772.61 | 4772.60 | 0.01 |

| G43–N57 | 1895.85 | 1896.06 | −0.21 | |

| Asn46–Pro47 | T1–N46 | 5236.03 | 5236.05 | −0.02 |

| P47–N57 | 1431.99 | 1432.61 | −0.38 | |

| P47–N57ox | 1447.67 | 1448.61 | −0.94 |

Finally, peptide bond cleavages mediated by proteases require that the cleavage site exists in the middle of a 4–28 residue segment in an unstructured conformation.36 Taking the upper limit of 8 residues together with the locations of the initial cleavage sites in AICD57 (Figure 3b), we conclude that the N-terminal fragment ending in K38 contains structure. Indeed, structure prediction using PSIPRED37 indicates that this fragment contains two β-strands, V2IVITLVML10 and T16SIHHGVVEV25 (Figure 3d), that presumably come together to form a stable antiparallel β-sheet, which is more resistant to proteolysis than a parallel β-sheet. We speculate that β-sheet formation in AICD57 is driven by the TVIVITL segment (Figure 3b). Interestingly, this segment contains the TVIV motif that is a hot spot for mutations linked to familial forms of AD.21

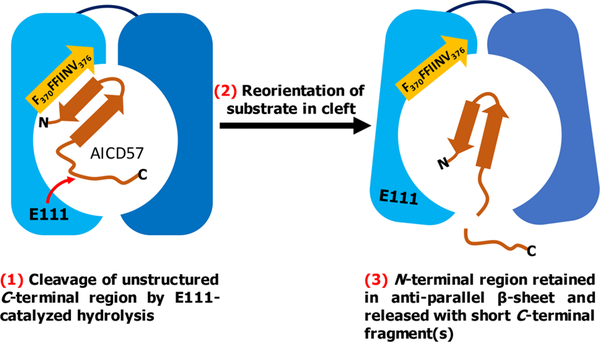

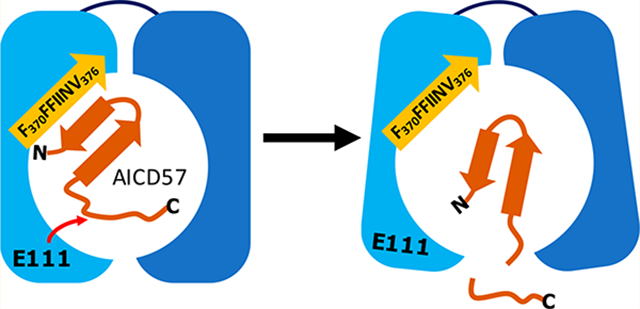

Figure 4 presents our proposed mechanism for the IDE-dependent degradation of AICD57. Examination of published X-ray structures of IDE reveals that its exosite contains an antiparallel β-sheet.25 IDE is specific to β-structure-forming substrates,23,24 and we speculate that in the case of AICD57, this specificity is mediated by hydrophobic interactions between the N-terminal β-strand (V2IVITLVML10) in AICD57 and the predominantly hydrophobic β-strand (i.e., F370FFIINV376) in IDE’s exosite. The AICD57 monomer is degraded in unstructured regions near its C-terminus, while the N-terminal β-sheet remains intact.

Figure 4.

Hypothesized mechanism of the IDE-dependent degradation of AICD57. The N-terminal half of IDE (light blue) comes together with the enzyme’s C-terminal half (dark blue) to form a catalytic chamber.23 Our mechanism proposes that the N-terminal β-strand of AICD57 interacts with the hydrophobic β-strand in IDE’s exosite (orange), resulting in proteolysis of the unstructured Cterminus of the polypeptide.

The results of our two aims indicate that the IDE-dependent degradation of AICD57 is dictated by AICD57’s global conformation in solution and toxic motifs. First, the β-sheet in AICD57 leaves the peptide unaffected by size limitations and allows it to enter IDE’s crypt (Figure 4). However, the β-sheet restricts cleavage to AICD57’s unstructured C-terminal half when in close proximity to E111. This observation contrasts with the less specific degradation of AICD5026–29 (Figure 3c), which we surmise has a less restricted structure. Second, the turnover of AICD57 can be explained by motifs within its unstructured C-terminal region. The sequence KFFEQ is common within soluble proteins like AICDs and signals them (and/or their fragments) for rapid lysosomal degradation.38 Moreover, the motif YENPTY is where AICDs interact with cofactors and transcription factors to form a nuclear complex, driving the transcription of APP itself and other genes.7,8,16 Our results demonstrate that IDE preferentially degrades the C-terminal part of AICD57 at or close to YENPTY (Figure 3c) while keeping KFFEQ intact. If these cleavages occur in the cytosol where most IDE in the cell is found,3 then the cascade of events that contributes to AD, including AICD’s nuclear translocation and induction of neurotoxic gene transcription,7–10 is prevented from taking place (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

IDE-dependent degradation of AICD57 prevents a cascade of events that contributes to AD. After APP is misprocessed through missed cleavages at the ε-sites by γ-secretase, AICD57 is produced along with Aβ42. Cleavage at the sites marked in light blue prevents the toxic function of the YENPTY motif. This includes nuclear translocation and neurotoxic gene transcription that promote downstream events such as elevated GSK-3β, hyperphosphorylated tau, and apoptosis. To compile this figure, we jointly considered our results and the preexisting literature on the relationship between AICDs and tau pathology.

Together, our results support AICD57’s existence as assemblies in dynamic equilibrium with β-sheet-containing monomers that are susceptible to partial degradation by IDE. If AICD57 tends to accumulate in the aging brain compared to smaller AICDs,26–29 this may arise from declining IDE activity and expression.3 Therefore, sustaining IDE expression and activity well into old age could represent a potential therapeutic strategy to prevent the accumulation of not only Aβ42 but also AICD57 in the aging brain. We noted that two residues in the unstructured C-terminal half of AICD57, T30 and Y44, have been reported to be phosphorylated in PD and AD, respectively.14,39 Because phosphorylation may cause long-range conformational changes40 that may impact the IDE-dependent hydrolysis of AICDs in the cytosol, preventing the phosphorylation of the AICDs may help sustain IDE activity. Finally, oligomeric assemblies of the Aβ peptides have been shown to contribute to AD.6 In light of a recent hypothesis that there could be other oligomeric assemblies that cause neurodegeneration,3 how the oligomeric assemblies of AICD57, first reported here, may contribute to AD requires further investigation.

METHODS

Pretreatment of AICD57

AICD57 (aka CTF57) was purchased from rPeptide. To ensure the absence of aggregates, the peptide was pretreated first with 100% 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-isopropanol and then with 2 mM NaOH, as described elsewhere.41 Pretreated AICD57 powder was stored at −20 °C until experimentation.

Expression and Purification of Insulin-Degrading Enzyme

The expression and purification of glutathione-S-transferase tagged human IDE (GST-IDE in pGEX-6p-1 vector, kindly provided by Dr. Malcolm Leissring of the University of California at Irvine) were accomplished following a protocol26 provided by Dr. Leissring with some modifications. Expression of GST-IDE in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus RIL was induced with 50 μM IPTG overnight at 25 °C. The non-metalloprotease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was added prior to cracking the cells. GST-IDE was purified using a 5 mL GST Trap Fast Flow column on an ÄKTA Pure FPLC (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and eluted with PBS containing 10 mM glutathione. After cleavage of the GST tag using GST PreScission protease, further purification of IDE was accomplished using a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex S-200 pg gel filtration column preequilibrated with PBS on the ÄKTA Pure FPLC. Purified protein concentration was determined by UV–vis spectroscopy using the molar extinction coefficient of IDE at 280 nm, ε280nm = 113570 M−1 cm−1.42 Flash-frozen IDE aliquots containing 1% glycerol (v/v) were stored at −80 °C in PBS (pH 7.4). Activity of IDE was confirmed using insulin (Sigma-Aldrich) or the fluorogenic peptide Mca-RPPGFSAFK(Dnp)-OH (R&D Systems) as substrates.

Preparation of Stock Solutions

Stock solutions of AICD57 and thioflavin T were prepared in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and their concentrations were determined by UV–vis spectroscopy using molar extinction coefficients of ε280nm = 4470 M−1 cm−143 and ε412nm = 36000 M−1 cm−1,32 respectively.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

Three types of samples were prepared for CD including (1) AICD57 only (20 μM), (2) IDE only (0.2 μM), and (3) AICD57 (20 μM) plus IDE (0.2 μM), that is, the substrate-to-enzyme ratio was 100:1 (mol/mol). All samples were incubated in quartz cuvettes (path length of 1 mm) at 4 °C. CD spectra were recorded at 4 °C using a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter. Spectra were recorded from 260 to 198 at 1 nm steps and averaged over eight accumulations.

Thioflavin-T (ThT) Fluorescence

ThT was added to aliquots taken from the CD samples such that the AICD57 to ThT ratio was 1:1 (mol/mol). Fluorescence spectra were recorded from 450 to 600 nm following excitation at 440 nm using a Cary Eclipse spectrometer (Agilent).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Aliquots of AICD57-containing samples (7 μL) were spotted on carbon-coated copper grids and stained with 1% uranyl acetate. After drying, the samples were stored at room temperature. Electron micrographs were recorded using a Phillips CM 10 transmission electron microscope at the Core Electron Microscopy Facility of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS)

Aliquots of CD samples containing AICD57 and IDE were retrieved periodically, and the reactions were quenched by acidification with 1% trifluoroacetic acid in water. The samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis by LC/MS at the Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Facility of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Peptide separation and mass spectrometry were performed using a NanoAcquity (Waters) UPLC system interfaced to an Orbitrap Q Exactive hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MS scans were acquired over 300–1750 m/z at 70000 resolution (200 m/z), and data-dependent acquisition chose the top ten most abundant precursor ions for MS/MS spectrometry by collision-induced fragmentation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Malcolm Leissring of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California at Irvine for generously providing the bacterial expression vector and protocol for the production of GST-tagged IDE.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH Grant R15AG055043 to N.D.L. Internal funding through the Lise Ann and Leo E. Beavers II endowment to Clark University supported preliminary parts of this study.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00305.

Mass spectrum of AICD57 after digestion by IDE for 6 h, CD spectra of AICD57 in the presence of IDE, peaks detected in mass spectra of AICD57 after digestion by IDE for 1 min and 2, 4, and 6 h (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. (2018) https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures.

- (2).Cline EN, Bicca MA, Viola KL, and Klein WL (2018) The amyloid-β oligomer hypothesis: Beginning of the third decade. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 64, S567–S610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kurochkin IV, Guarnera E, and Berezovsky IN (2018) Insulin-degrading enzyme in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 39, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Doig AJ, Del Castillo-Frias MP, Berthoumieu O, Tarus B, Nasica-Labouze J, Sterpone F, Nguyen PH, Hooper NM, Faller P, and Derreumaux P (2017) Why is research on amyloid-β failing to give new drugs for Alzheimer’s disease? ACS Chem. Neurosci 8, 1435–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Haass C, Hung AY, Schlossmacher MG, Oltersdorf T, Teplow DB, and Selkoe DJ (1993) Normal cellular processing of the β-amyloid precursor protein results in the secretion of the amyloid β peptide and related molecules. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 695, 109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lazo ND, Maji SK, Fradinger EA, Bitan G, and Teplow DB (2005) The amyloid-β protein, in Amyloid proteins-the beta sheet conformation and disease (Sipe JC, Ed.), pp 385–491, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kim HS, Kim EM, Lee JP, Park CH, Kim S, Seo JH, Chang KA, Yu E, Jeong SJ, Chong YH, and Suh YH (2003) C-terminal fragments of amyloid precursor protein exert neurotoxicity by inducing glycogen synthase kinase-3β expression. FASEB J. 17, 1951–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).von Rotz RC, Kohli BM, Bosset J, Meier M, Suzuki T, Nitsch RM, and Konietzko U (2004) The APP intracellular domain forms nuclear multiprotein complexes and regulates the transcription of its own precursor. J. Cell Sci 117, 4435–4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ghosal K, Vogt DL, Liang M, Shen Y, Lamb BT, and Pimplikar SW (2009) Alzheimer’s disease-like pathological features in transgenic mice expressing the APP intracellular domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 18367–18372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ryan KA, and Pimplikar SW (2005) Activation of GSK-3 and phosphorylation of CRMP2 in transgenic mice expressing APP intracellular domain. J. Cell Biol 171, 327–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cao X, and Sudhof TC (2001) A transcriptionally active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science 293, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gao YH, and Pimplikar SW (2001) The γ-secretasecleaved C-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein mediates signaling to the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 98, 14979–14984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Multhaup G, Huber O, Buee L, and Galas MC (2015) Amyloid precursor protein (APP) metabolites APP intracellular fragment (AICD), Aβ42, and tau in nuclear roles. J. Biol. Chem 290, 23515–23522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chen ZC, Zhang W, Chua LL, Chai C, Li R, Lin L, Cao Z, Angeles DC, Stanton LW, Peng JH, Zhou ZD, Lim KL, Zeng L, and Tan EK (2017) Phosphorylation of amyloid precursor protein by mutant LRRK2 promotes AICD activity and neurotoxicity in parkinson’s disease. Sci. Signaling 10, eaam6790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Trazzi S, Mitrugno VM, Valli E, Fuchs C, Rizzi S, Guidi S, Perini G, Bartesaghi R, and Ciani E (2011) APP-dependent upregulation of PTCH1 underlies proliferation impairment of neural precursors in down syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet 20, 1560–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ohkawara T, Nagase H, Koh CS, and Nakayama K (2011) The amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain alters gene expression and induces neuron-specific apoptosis. Gene 475, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kametani F, and Hasegawa M (2018) Reconsideration of amyloid hypothesis and tau hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci 12, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Dimitrov M, Alattia JR, Lemmin T, Lehal R, Fligier A, Houacine J, Hussain I, Radtke F, Dal Peraro M, Beher D, and Fraering PC (2013) Alzheimer’s disease mutations in APP but not γ-secretase modulators affect ε-cleavage-dependent AICD production. Nat. Commun 4, 2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kametani F (2008) ) ε-secretase: Reduction of amyloid precursor protein ε-site cleavage in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res 5, 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chen FS, Gu YJ, Hasegawa H, Ruan XY, Arawaka S, Fraser P, Westaway D, Mount H, and St George-Hyslop P (2002) Presenilin 1 mutations activate γ(42)-secretase but reciprocally inhibit ε-secretase cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and S3-cleavage of Notch. J. Biol. Chem 277, 36521–36526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Bertram L, and Tanzi RE (2012) The genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci 107, 79–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Saido T, and Leissring MA (2012) Proteolytic degradation of amyloid β-protein. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med 2, a006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Shen Y, Joachimiak A, Rich Rosner M, and Tang WJ (2006) Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature 443, 870–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tang WJ (2016) Targeting insulin-degrading enzyme to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 27, 24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Durham TB, Toth JL, Klimkowski VJ, Cao JX, Siesky AM, Alexander-Chacko J, Wu GY, Dixon JT, McGee JE, Wang Y, Guo SY, Cavitt RN, Schindler J, Thibodeaux SJ, Calvert NA, Coghlan MJ, Sindelar DK, Christe M, Kiselyov VV, Michael MD, and Sloop KW (2015) Dual exosite-binding inhibitors of insulin-degrading enzyme challenge its role as the primary mediator of insulin clearance in vivo. J. Biol. Chem 290, 20044–20059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Farris W, Mansourian S, Chang Y, Lindsley L, Eckman EA, Frosch MP, Eckman CB, Tanzi RE, Selkoe DJ, and Guenette S (2003) Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid β-protein, and the β-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 100, 4162–4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Miller BC, Eckman EA, Sambamurti K, Dobbs N, Chow KM, Eckman CB, Hersh LB, and Thiele DL (2003) Amyloid-β peptide levels in brain are inversely correlated with insulysin activity levels in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 100, 6221–6226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Edbauer D, Willem M, Lammich S, Steiner H, and Haass C (2002) Insulin-degrading enzyme rapidly removes the β-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD). J. Biol. Chem 277, 13389–13393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Venugopal C, Pappolla MA, and Sambamurti K (2007) Insulysin cleaves the APP cytoplasmic fragment at multiple sites. Neurochem. Res 32, 2225–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Sarkar PK, and Doty P (1966) The optical rotatory properties of the β-configuration in polypeptides and proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 55, 981–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Robbins KJ, Liu G, Lin G, and Lazo ND (2011) Detection of strongly bound thioflavin T species in amyloid fibrils by ligand-detected 1H NMR. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2, 735–740. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ivancic VA, Ekanayake O, and Lazo ND (2016) Binding modes of thioflavin T on the surface of amyloid fibrils studied by NMR. ChemPhysChem 17, 2461–2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lazo ND, Grant MA, Condron MC, Rigby AC, and Teplow DB (2005) On the nucleation of amyloid β-protein monomer folding. Protein Sci. 14, 1581–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Liu G, Prabhakar A, Aucoin D, Simon M, Sparks S, Robbins KJ, Sheen A, Petty SA, and Lazo ND (2010) Mechanistic studies of peptide self-assembly: Transient α-helices to stable β-sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 18223–18232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Fontana A, Polverino de Laureto P, De Filippis V, Scaramella E, and Zambonin M (1997) Probing the partly folded states of proteins by limited proteolysis. Folding Des. 2, R17–R26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hubbard SJ (1998) The structural aspects of limited proteolysis of native proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol 1382, 191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, and Jones DT (2013) Scalable web services for the PSIPRED protein analysis workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W349–W357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Buoso E, Biundo F, Lanni C, Schettini G, Govoni S, and Racchi M (2012) AβPP intracellular C-terminal domain function is related to its degradation processes. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 30, 393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Barbagallo AP, Weldon R, Tamayev R, Zhou D, Giliberto L, Foreman O, and D’Adamio L (2010) Tyr(682) in the intracellular domain of APP regulates amyloidogenic APP processing in vivo. PLoS One 5, e15503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ando K, Iijima K, Elliott JI, Kirino Y, and Suzuki T (2001) Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of the interaction of amyloid precursor protein with Fe65 affects the production of β-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem 276, 40353–40361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Fradinger EA, Maji SK, Lazo ND, and Teplow DB (2005) Studying amyloid β-protein assembly, in Amyloid precursor protein: A practical approach (Xia W, and Xu H, Eds.), pp 83–110, CRC Press, Boca Raton. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sharma SK, Chorell E, Steneberg P, Vernersson-Lindahl E, Edlund H, and Wittung-Stafshede P (2015) Insulin-degrading enzyme prevents α-synuclein fibril formation in a nonproteolytical manner. Sci. Rep 5, 12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, and Bairoch A (2005) Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server, in The proteomics protocols handbook (Walker JM, Ed.), pp 571–607, Human Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.