Abstract

Objectives: T'ai chi (TC) has been found effective for improving chronic low back pain (cLBP). However, such studies did not include adults over 65 years of age. This study was designed to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of TC in this population compared with Health Education (HE) and with Usual Care (UC).

Design: Feasibility randomized controlled trial.

Settings/Location: Participants were recruited from Kaiser Permanente Washington and classes took place in a Kaiser facility.

Patients: Adults 65 years of age and older with cLBP.

Interventions: Twenty-eight participants were randomized to 12 weeks of TC followed by a 24-week tapered TC program, 12 were assigned to a 12-week HE intervention and 17 were assigned to UC only.

Outcome Measures: Feasibility and acceptability were determined by recruitment, retention and 12-, 26-, and 52-week follow-up rates, instructor adherence to protocol, class attendance, TC home practice, class satisfaction, and adverse events.

Results: Fifty-seven participants were enrolled in two cohorts of 28 and 29 during two 4-month recruitment periods. Questionnaire follow-up completion rates ranged between 88% and 93%. Two major class protocol deviations were noted in TC and none in HE. Sixty-two percent of TC participants versus 50% of HE participants attended at least 70% of the classes during the 12-week initial intervention period. Weekly rates of TC home practice were high among class attendees (median of 4.2 days) at 12 weeks, with fewer people practicing at 26 and 52 weeks. By 52 weeks, 70% of TC participants reported practicing the week before, with a median of 3 days per week and 15 min/session. TC participants rated the helpfulness of their classes significantly higher than did HE participants, but the groups were similarly likely to recommend the classes.

Conclusion: The TC intervention is feasible in this population, while the HE group requires modifications in delivery.

Keywords: chronic low back pain, t'ai chi, older adults, randomized controlled trial, feasibility

Introduction

Roughly a quarter of older adults report low back pain (LBP)1 with prognosis worsening with age.2 Older adults commonly have more disabling back pain than adults under 652; an estimated 12% of adults over age 65 suffer from impairing chronic LBP (cLBP).3

In the United States, about $86 billion is spent annually on direct costs of medical care for back/neck pain,4 with particularly burgeoning costs for back pain in older Americans. While the Medicare population increased only 42% between 1991 and 2002, expenditures for back pain increased 387%.5 In addition, during a recent 12-year period, Medicare expenditures for epidural steroid injections increased 629%, expenditures for opioids for back pain increased 423%, the number of lumbar magnetic resonance images increased 307%, and the number of spinal fusion surgeries increased 220%.6 Despite these large investments in the care for BP, the health and functional status of Americans with MP has deteriorated.4

The management of cLBP can be especially challenging in older adults because they have more comorbidities with attendant polypharmacy7 and higher risk of adverse effects of commonly used treatments, due to normal physiological changes.3,8–10 Moreover, even some nonpharmacological therapies may be contraindicated or increase risk for older adults, for example high-velocity low-amplitude spinal manipulation in those with osteoporosis.11 Many standard yoga postures require modifications for older adults to enhance safety.12,13

In a systematic review14 of 18 studies of LBP in older adults (60+ years), manual therapies, acupuncture, percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, mindfulness, yoga, education, exercise, and medications were not clinically superior to sham, usual care (UC), or minimal interventions in terms of improved pain or dysfunction. However, this evidence base is limited and may well change with further research. There are no treatment guidelines for older adults with cLBP. The high prevalence of back pain in older adults and the rapid projected growth of this population ensure that the negative consequences of lacking a strong evidence base of treatments for cLBP in older adults will increase over time.

T'ai chi (TC) is a promising treatment for older adults with cLBP for multiple reasons. It is now recommended for the treatment of cLBP in adults based on two “fair-quality” trials reported in English.15 A recent meta-analysis16 with 10 trials (9 from China), mostly cLBP, found that TC was associated with lower pain and improved disability, and they rated most trials as “fair to good” quality. However, the studies appeared heterogeneous in dose (from 12 to 168 sessions) in terms of TC style, session length, classes/weeks, and weeks of classes. The average age of most trials ranged from 38 to 45 years of age. In a feasibility study17 of older adults with multiple pain sites who were at risk for falls, TC reportedly lowered pain severity and pain interference.

TC has several features that may make it a particularly attractive treatment for older adults. These include a multicomponent intervention that addresses both physical and psychosocial aspects of pain.18 TC includes gentle movements that may simulate activities of daily living. At least some evidence suggests TC may be effective for improving balance19 and fall prevention,20 congestive heart failure,21 bone health,22 osteoarthritis,23,24 and depression,25 conditions that are more common in older adults. We are unaware of studies of TC for cLBP that focused on older adults (and it is unclear if any were included in the published trials).16

This pilot randomized trial was designed to test the feasibility and acceptability of a TC intervention compared with Health Education (HE) and UC. We also present pilot data exploring suggestions for improving the interventions for a larger trial.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This feasibility trial was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA), an integrated health care system with roughly 660,000 members in Washington State. The Institutional Review Board approved the study. All participants provided consent for eligibility screening and study enrollment.

Participants were adults at least 65 years old who met the NIH Task Force definition for cLBP (i.e., back pain persisted at least 3 months and has resulted in pain on at least half the days in the past 6 months).26 In addition, they were required to report at least moderate pain intensity (≥4 on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale) and moderate pain-related activity limitation (≥3 on a similar 0 to 10 scale).

We excluded individuals who had complicated back pain (i.e., due to cancer, infectious or inflammatory causes or sciatica), had possible cognitive impairment (score of >2 on the 6-item Callahan screener),27 had prior lumbar surgery, had red flags of serious underlying illness (fever, recent weight loss of 10 lbs. or more), had practiced TC in the last year, or were unable to meet minimal requirements for TC practice (i.e., could not transfer weight from one leg to another or bend at the hips, had uncontrolled cardiac arrhythmia).

We sent invitation letters to patients identified through electronic health records who had visits to primary care providers for back pain. We supplemented these mailings with multiple strategies (i.e., posters at local senior centers and locations where older adults would get health care, presentations to the Senior Caucus (a KPWA group of older adults) and mailing to non-KPWA patients using purchased targeted mailing lists for back pain). Our goal was 32 participants in each cohort, with a total of 32 in TC, 12 in HE, and 20 in UC. (We had originally planned to compare TC with UC, but our funders asked us to include an attention control. We were skeptical we could develop an effective attention control, so we chose to recruit slightly more people for UC than for HE).

In the first cohort, participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to TC or UC. In the second cohort to meet each group's sample size, they were randomized in a 4:3:1 ratio to TC, HE, or UC. (the different randomization ratios occurred because we did not have a facilitator for HE for Cohort 1). Prospective participants were initially screened by phone and then completed an in-person visit that included final eligibility questions, written informed consent, two physical performance measurements, completion of a self-administered baseline questionnaire, and randomization and enrollment into the study. Both cohorts were informed of the intervention groups for their cohort.

Randomization

The study biostatistician created the random allocation sequence, which was embedded by the programmer into a tamperproof computer program. Thus, the study staff who randomized participants were unaware of their group assignment in advance.

Interventions

All participants had access to the insurance provided by their health plan. UC participants did not receive further interventions from the study. The TC and HE groups both received 12 weeks of twice-weekly 60-min classes for a total of 24 classes (Table 1). In addition, TC participants received another 24 weeks of maintenance classes: six-weekly classes, 6 weeks of biweekly classes, and 3 months of monthly classes.

Table 1.

Detailed Description of Interventions

| Descriptor | T'ai chi (TC) | Health education (HE) | Usual care (UC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of Intervention | 6 movements from the second portion of the Yang Style 24 short form is the center piece of the intervention; classes are progressive. Developed by one of our instructors, and informed by research literature and her experience. Reviewed by an experienced TC instructor who is also a researcher. | 24 topics about health likely of interest to older adults were chosen by our team of researchers (clinical trialist, geriatrician, nurse practitioner with doctoral work in gerontology, pain psychologist); used evidence-based sources for the course outlines. | This is the medical care that participants are entitled to by virtue of their insurance. |

| Rationale | Classes incorporated features of TC that are known to be beneficial for cLBP: simple classical TC movements to enhance musculoskeletal strength and flexibility, efficient posture, heightened body awareness, mindful diaphragmatic breathing, healing imagery and visualization. | The topics designed to educate older adults about a broad range of relevant health topics to keep interest high; there was an explicit connection made between each topic and back pain. The information should be unlikely to be a potent educational intervention for back pain. | Provides a comparison for interventions that includes the treatments that participants might get outside of the study |

| Frequency | 2 × /week for 12 weeks; then tapered schedule (1 × /week for 6 weeks, every other week for 6 weeks, monthly for 3 months) | 2 × /week for 12 weeks | As desired by patient |

| Duration | 1 h | 1 h | |

| How delivered | Face to face; | Face to face; | |

| Median of 10 attendees (range = 5–14) | Median of 6 attendees (range = 4–8) | ||

| Where delivered | Classroom at Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA) medical facility | Classroom at KPWA medical facility | |

| Who provided | Two professional TC teachers with more than 25 years of experience practicing TC; substitute teachers came from their TC schools; both teach Yang Style for beginners as well as other styles; they continue to study with master teachers in the USA and China. Both had prior experience teaching TC in studies and in working with people who have pain. | Primary educator had a background in both nursing and social work. She had prior experience leading groups and working with older adults. Three experts led several sessions (back pain, falls prevention, osteoarthritis). | |

| Adherence monitoring | Research Assistant (RA) took attendance. The RA contacted participants who missed a class without notifying them. | RA took attendance. The RA contacted participants who missed a class without notifying them. | |

| Class flow | Greeting and discussion of home practice and relevant Tai Chi principles | Greeting | |

| Relaxation sequence, abdominal breathing, and standing meditation (will teach these and posture in first lessons) | Assess knowledge of participants on topic | ||

| Warm-up exercises (teach and practice) | Didactic presentation | ||

| Practice previous movement flows (except for first class) | Discussion (was interspersed, in the middle or at the end of presentation, depending on the topic) | ||

| Learn and practice a new movement flow (complete flow is: “opening move: step out, raise, and lower arms”; “ward off left”; “grasping sparrow's tail”; “single whip”, “cloud hands”; “repeat of single whip”, “step back, lower arms”). | Topics included healthy aging, back pain, nutrition, using medications safely, flu/pneumonia prevention, osteoporosis, falls prevention, brain health, heart health & stroke, safe driving, diabetes, talking with your doctor, skin health, care-giving, sleep, osteoarthritis, housing options, depression, bladder problems, social support, stress reduction, footwear. | ||

| Student practice and individual corrections | |||

| Closing, centering breath & visualization | |||

| Multiple repetitions of each class (the number depended on the difficulty of the new movement). No new movements introduced after week 10, but refinements were made. | |||

| Home practice | On all non-TC class days. HP mirrors the class practice from the prior week, but took roughly 15 min to complete. | None (to reduce concern about the intervention improving back pain) | |

| Home practice supports | Summary of Practice for each week; DVDs and access to on-line videos showed experienced TC practitioners demonstrating the warm-ups and the movements students had already learned. In later classes, participants also given photos of the warm-up sequences to save them time in practicing. Not all relevant warm-ups were in all DVDs (videos) so some participants would need to access multiple DVDs (videos) if they needed guidance for their entire practice. | Not relevant | |

| Home practice adherence | Complete weekly home practice logs and questions on all follow-up questionnaires | Not relevant | |

| Tailoring | The intervention guide provided modifications for patients who could not do the standard movements (e.g., do in a chair). Instructors were permitted to vary the flow of the classes if appropriate. | We allowed the participants to guide some of the presentations, according to their interests and amount of knowledge on a topic. | |

| Modifications | Home practice videos were added that showed the movement flows with the instructors facing away from the camera so that participants could follow them exactly. | None | |

| Fidelity monitoring | Special checklists describing the key elements of each class (customized for each class) | Special checklist describing the class topic (customized for each class) and ensuring no discussion of CIH therapies for back pain | |

| RA checks off the key elements with the use of the TC protocol. | RA checks off the key elements with the use of the HE protocol. | ||

| Study Principal Investigator attended one class and completed a checklist. | |||

| Problems were brought to the attention of the study principal investigator (PI) by the instructor or the RA. | Problems were brought to the attention of the study principal investigator by the instructor or the RA. | ||

| The PI sent emails to the instructors after classes asking for open-ended comments on the class. Observations and suggestions for modifying the treatment protocol were collected. | Supervision by a nurse practitioner | ||

| Possible reasons for improvement | Tai Chi intervention improves functional status, reduces stress, increase body awareness, etc. (see Rationale) | Lifestyle changes due to health education | |

| Instructor and Class support | Instructor and Class support | ||

| Any interventions received | Any interventions received | Any interventions received | |

| Natural History | Natural history | Natural history | |

| Usual Care Cointerventions | None: 7 participants; One provider: 3 (1 PCP, 1 chiropractic visit, one had surgery); Two providers: 3 (1 massage and naturopathic doctor; 1 PCP and 10 PT visits; 1 massage and 5 acupuncture visits); 3 providers: 1 (PCP, massage, chiropractor, no. visits unknown), 6 providers: 1 (PCP, medical specialist, acupuncture, chiropractor, massage, PT) and took an MBSR class; 8 providers: 1 (acupuncture, massage (2 types), chiropractor, PT, PCP, medical specialist, naturopathic doctor) |

Using the TIDier framework,28 Table 1 provides detailed descriptions of the interventions, including the instructors, TC home practice, and assessments of adherence and fidelity.

The Yang-style TC intervention was developed by one of our instructors, based on her experience and the literature (Table 1). Standard TC was a progressive class series that included simple classical TC movements, efficient posture, enhanced body awareness, mindful diaphragmatic breathing, and healing imagery. Each class began with a short discussion of home practice and relevant TC principles, followed by a focus on posture and abdominal breathing, warm-up exercises, learning and practicing a movement flow that culminated in six distinct movements,29 and a closing centering breath and short visualization. Movements were added progressively during the 12-week period.

The HE classes had a structured, comprehensive curriculum designed to provide accurate, useful information on a variety of topics pertinent to healthy aging (e.g., medication safety, falls prevention, social support) and to elicit discussion by posing open-ended questions.

Outcomes and follow-up

Feasibility outcomes were recruitment rates (at least 85% of target), instructor intervention adherence, participant adherence to the interventions (classes/week, at least 70%30 of classes and for TC, home practice/week), and follow-up rates for the 12-, 26-, and 52-week time points (completion of self-administered questionnaires plus in-person measurements; goal of >80% completion of questionnaires and in-person measurements). Participants were provided $25 for completing each follow-up questionnaire.

We used outcome measures recommended by the NIH Task Force,26 which included PROMIS short-form measures31 for physical function,32 pain intensity,33 pain interference,34 sleep disturbance,33 and depression.35 Our anxiety measure was the GAD-2.36 Our coprimary outcome measures were the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire,37 a well-validated measure of back pain-related disability, and the 0–10-point pain intensity measure.33 The Short Physical Performance Battery38 and the Four Square Step Test,39 both well-validated measures of physical performance, assessed physical function, and balance, respectively.

Acceptability outcomes included data on the helpfulness of the interventions (0–10 scale), willingness to recommend the classes to others (very unlikely, moderately unlikely, not sure/don't know, moderately likely, very likely) and the Patient–Provider Connection scale (PPC scale).40 The PPC scale contains seven statements about the provider (satisfaction; trust; needs paid attention to; information; felt respected; felt understood; supported and encouraged). We modified the wording for use in our study by referencing the TC instructor or the HE facilitator. Using a five-item Likert scale (not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much), respondents were asked to select the most accurate response, which were averaged for a final score.

To assess intervention safety, we asked participants if there was anything in the TC (or home practice) or the HE that caused them significant discomfort or pain or that they felt was harmful.

We sent letters to participants before each follow-up time point to remind them a questionnaire would arrive the next week. We followed up by phone with participants who did not return the questionnaire within a few weeks.

After the 52-week interviews, qualitative feedback on improving the recruitment and enrollment experience and suggestions for class improvement was obtained from the TC and HE participants through 2-h focus groups. Participants were paid $50 for their time. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. In UC, similar feedback on logistics was obtained by self-administered questionnaire. We descriptively summarized participants' suggestions for improvement for use in a subsequent trial.

Sample size and statistical analyses

Sample sizes for feasibility studies need to be large enough to provide a high likelihood of surfacing any important problems that may exist.41 Our sample size of 64 was chosen based on practical considerations to provide ample opportunity to identify problems with the study procedures, intervention protocols (including adherence), outcome measures, and follow-up rates. The study is underpowered for detecting clinically important effects in our outcomes. We do not report on outcomes for that reason.

Descriptive data are presented as means, medians, and frequencies. Nonparametric descriptive statistics (Mann–Whitney U test, Fisher's exact test) were used for several feasibility aims.

Results

Recruitment

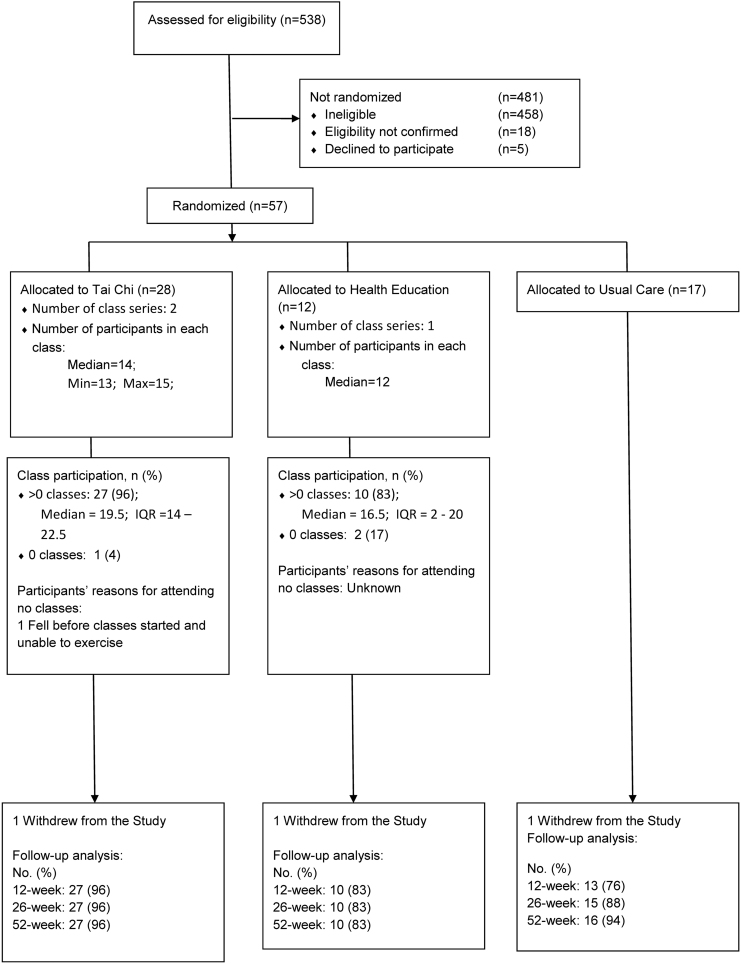

We enrolled 57 participants out of our goal of 64 (89%), with 29 and 28 participants in each cohort. Among 538 individuals assessed for eligibility between July and September 2017 (Cohort 1) or between October and January 2018 (Cohort 2), 57 (10.6%) were randomized, five declined to participate and most others were ineligible (Fig. 1). The most common reasons for ineligibility were not meeting our definition of chronic moderate LBP [not chronic (n = 135, 29.5%); too mild (n = 97, 21.2%)]; did not sufficiently interfere with daily activities (n = 58, 12.7%) or unable to attend classes (n = 37, 8.1%). The most successful method of recruitment was mailing letters to KPWA enrollees who sought care for back pain (n = 52) and the least successful was mailing to the general population (n = 0). All but one participant was from KPWA.

FIG. 1.

Flow Diagram for Trial Participants.

Population

Participants ranged between 65 and 89 years of age (mean of 72.9 years; 74% were 65–74 years; 23% were 75–84 years; 4% were 85–89 years). Most participants (61%) were women (Table 2). While 71.9% of participants were white, we recruited both African Americans (14%) and Asians (10.5%). Virtually all participants had attended college, roughly 4 in 5 were retired and around half were married.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants by Treatment Group

| T'ai chi | Health education | Usual care | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | 28 | 12 | 17 | 57 |

| Age, Mean (SD), years | 73.2 (5.9) | 73.6 (5.5) | 71.8 (3.8) | 72.9 (5.2) |

| Women, N % | 16 57.1 | 8 66.7 | 11 64.7 | 35 61.4 |

| Education - some college+, N % | 26 92.9 | 11 91.7 | 16a 100 | 53a 94.6 |

| Race - white, N % | 21 75.0 | 9 75.0 | 11 64.7 | 41 71.9 |

| Non-Hispanic, N % | 28 100 | 12 100 | 17 100 | 57 100.0 |

| Retired, N % | 25 89.3 | 10 83.3 | 12 70.6 | 47 82.5 |

| Married or living as married, N % | 20 71.4 | 5 41.7 | 6a 37.5 | 31a 55.4 |

| Back pain (BP) history and treatments | ||||

| BP an ongoing problem for >5 years, N % | 16 57.1 | 8 50.0 | 10 58.8 | 32 56.1 |

| BP a problem nearly every day in last 6 months, N % | 22 78.6 | 8 66.7 | 9 52.9 | 39 68.4 |

| Leg pain below knee, N % | 2 7.1 | 3 25.0 | 4 23.5 | 9 15.8 |

| Ever used opioid medications, N % | 6 21.4 | 5 41.7 | 5 29.4 | 16 28.1 |

| Ever used injections, N % | 2 8.0 | 1 8.3 | 2a 12.5 | 5a 9.4 |

| Ever used exercise therapy, % | 14b 53.9 | 9 75.0 | 7b 46.7 | 30d 56.6 |

| Ever used psychological counseling, N % | 1b 3.9 | 1 8.3 | 2a 12.5 | 4c 7.4 |

| Ever had surgery, % | 0 0.0 | 0 0.0 | 0 0.0 | 0 0.0 |

| Bothered by widespread pain, N % | 8 28.6 | 3 25.0 | 4 23.5 | 15 26.3 |

| Bothered a lot by pain, N % | 5 17.9 | 2 16.7 | 2 11.8 | 9 15.8 |

| Expectations (Tai Chi) [0–10 scale] | 7.0 (2.2) | 6.7 (1.8) | 7.0 (2.0) | 6.9 (2.0) |

| Expectations (Health Ed) [0–10 scale] | 5.1 (2.1) | 6.0 (1.8) | 6.6 (0.5) | 5.6 (1.9) |

| Other baseline descriptors | ||||

| Ever tried tai chi, N % | 5 17.9 | 1 8.3 | 5 29.4 | 11 19.3 |

| Current use of opioid medications, N % | 2 7.1 | 1 8.3 | 0 0.0 | 3 5.3 |

| Current use of medications for back pain, N % | 20 71.4 | 9 75.0 | 7 41.2 | 36 63.2 |

| Current use of NSAIDS, N % | 12 42.9 | 4 33.3 | 2 11.8 | 18 31.6 |

| Current use of back-specific exercise, N % | 13 46.4 | 7 58.3 | 12 70.6 | 32 56.1 |

| Current use of general exercise, N % | 19 67.9 | 8 66.7 | 10 58.8 | 37 64.9 |

| Never smoker, N % | 14 50.0 | 6a 54.6 | 11 64.7 | 31a 55.4 |

| Never drank or used drugs more than meant to, N % | 23 82.1 | 11 91.7 | 15 88.2 | 46 86.0 |

| Never felt wanted or needed to cut down on drinking or drug use, N % | 22 78.6 | 9 75.0 | 16 94.1 | 47 82.5 |

| Primary outcome measures | ||||

| RMDQ, mean (SD) [0–24 scale] | 11.4 (4.3) | 11.7 (3.7) | 9.4 (4.2) | 10.8 (4.2) |

| Pain intensity, mean (SD) [0–10 scale] | 5.5 (1.7) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.2 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.6) |

| Secondary outcome measures | ||||

| Believe it is unsafe to be physically active, N % | 2 7.1 | 0 | 0 | 2 3.5 |

| Believe back pain is terrible and will never improve, N % | 3 10.7 | 1 8.3 | 1 5.9 | 5 8.8 |

| PROMIS Pain Interference (T-score = 41.6–75.6), mean (SD) | 60.7 (5.0) | 59.5 (4.7) | 57.1 (5.1) | 59.4 (5.1) |

| PROMIS Physical Function (T-score = 22.9–56.9), mean (SD) | 33.4 (4.6) | 33.3 (3.2) | 31.8 (3.3) | 32.9 (4.0) |

| PEG (0–10 scale), mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.0) | 4.6 (1.9) | 4.2 (1.5) | 4.7 (1.8) |

| PROMIS Depression (T-score = 41.0–79.4), mean (SD) | 48.2 (7.9) | 49.6 (8.4) | 48.2 (6.9) | 48.5 (7.6) |

| PROMIS Sleep Disturbance (T-score = 32.0–73.3), mean (SD) | 52.2 (6.1) | 53.7 (6.3) | 52.7 (7.0) | 52.65 (6.3) |

| GAD-2 (0–6 scale), mean (SD) | 2.5 (0.9) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.1) |

| GAD-2 Score 3+, N % | 8 28.6 | 6 50.0 | 10 58.8 | 24 42.1 |

| Fear of Falling, mean (SD) [range = 7–28] | 11.1 (3.1) | 10.8 (3.6) | 9.8 (2.5) | 10.6 (3.1) |

| SPPB, mean (SD) [range = 0–12] | 10.4 (2.0) | 9.5 (2.8) | 11.0 (0.9) | 10.4 (2.0) |

| Four Square Step Test, mean (SD) (sec) | 9.8 (2.3) | 13.6 (6.5) | 8.9 (1.9) | 10.3 (3.9) |

One person has missing data.

Two participants have missing data.

Three participants have missing data.

Four participants have missing data.

Over half of participants had had back pain for over 5 years, the typical participant reported moderate dysfunction and pain intensity, and around a quarter reported widespread pain.

Intervention feasibility

Class attendance was excellent for standard TC, with all but one participant attending at least one class and 18 (64%) attending at least 70% of the 24 classes (Table 3). For HE, 10 of 12 (83%) attended at least one class and 6 of 12 (50%) attended at least 70% of the classes.

Table 3.

Intervention Adherence Including Home Practice

| |

T'ai chi (TC) |

Health education (HE) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Total N | Total N | ||||

| Adherence, First 12 weeks [from class attendance] | ||||||

| Class Attendance, % 1+ classes of 24 | 28 | 27 | 96% | 12 | 10 | 83% |

| Median number of classes attended of 24a | 28 | 28 | 19.5 | 12 | 12 | 16.5 |

| Median number of classes attended, if attended any | 27 | 27 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 17.5 |

| Attended at least 70% of 24 classes | 28 | 18 | 64% | 12 | 6 | 50% |

| Classes attended, N, % of total possible | 672 | 477 | 71% | 288 | 151 | 52% |

| Home practice [HP], first 12 weeks [HP logs] | ||||||

| Returned 11 or 12 completed home practice logs (27 possible participants), N % | 27 | 21 | 78% | |||

| Average number of days practiced (of 5 maximum) | 21 | 21 | 4.2 | |||

| Returned fewer than 11 home practice logs, N % | 27 | 4 | 15% | |||

| Average number of days practiced (of 5 maximum) | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Returned no home practice logs, N % | 27 | 2 | 7% | |||

| HP, 12-week follow-up questionnaire | ||||||

| Practice in prior week | 26 | 24 | 92% | |||

| Days/week, N, mean days week | 24 | 24 | 5.4 | |||

| Days/week, N, median days week | 24 | 24 | 6 | |||

| Minutes/practice session, median | 24 | 24 | 15 | |||

| Minutes/practice session, range (minimum, maximum) | 24 | 5 | 190 | |||

| Adherence, Last 24 weeks [from class attendance] | ||||||

| Class Attendance, % 1+ classes of 12 | 27 | 22 | 81% | |||

| Median number of classes attended of 12 | 27 | 22 | 8 | |||

| Median number of classes attended, if attended any | 22 | 22 | 8.5 | |||

| Attended at least 70% of 12 classes | 27 | 11 | 41% | |||

| Classes attended, N, % of total possible | 336 | 184 | 55% | |||

| HP, 12 class, 24-week maintenance period [HP logs] | ||||||

| Returned 21, 22, or 23 completed home practice logs, N % (of 22 possible participants) | 22 | 13 | 59% | |||

| Average number of days practiced (of 6–7 maximum/week) | 13 | 13 | 4.8 | |||

| Returned fewer than 20 home practice logs, N % | 22 | 5 | 18% | |||

| Returned no home practice logs, N % | 22 | 3 | 14% | |||

| Home practice, 26-week follow-up questionnaire | ||||||

| Practice in prior week | 26 | 19 | 73% | |||

| Days/week (N = 19 of 26 individuals), N, mean days week | 26 | 19 | 4.5 | |||

| Days/week, N, median days week | 19 | 19 | 5 | |||

| Minutes/practice session, N, median | 19 | 19 | 20 | |||

| Minutes/practice session, range | 19 | 10 | 55 | |||

| Home practice, 52-week follow-up questionnaire | ||||||

| Practice in prior week | 27 | 19 | 70% | |||

| Days/week, N, mean days week | 19 | 19 | 3.6 | |||

| Days/week, N, median days week | 19 | 19 | 3 | |||

| Minutes/practice session, N, median | 19 | 19 | 15 | |||

| Minutes/practice session, range | 19 | 3 | 60 | |||

Five participants in TC withdrew from classes prematurely: 1 had a fall before classes and never attended any, 1 had other health issues, 1 cited personal issues; 1 unexpectedly needed to care for their spouse after surgery; 1 unexpectedly had no transportation.

Four participants in HE withdrew from classes prematurely: 2 never attended any classes and gave no reasons; 1 withdrew after class 1, giving no reason (but stated they learned something about the importance of exercise and were very likely to continue using this material); 1 withdrew after class 2, giving no reason (but stated that they learned they needed to move and were moderately unlikely to use the material they learned).

As shown in Table 3, reported home practice was high (an average of 4.2 days/week) during the 12 weeks of standard classes. Only two class attendees never provided home practice logs (both of whom attended only three classes). At their 12-week follow-up, most participants reported practicing at home (median of 15 min/day for an average of 5 days/week).

During the 12 class, 24-week maintenance period, attendance at TC classes declined (Table 3). Among the 27 individuals attending at least 1 standard TC class, 22 (82%) attended at least 1 maintenance class but only 11 (41%) attended at least 70% of the 12 maintenance classes. Four of five who attended no maintenance classes stopped attending classes during the first 12 weeks.

Home practice also dropped off during the maintenance period (Table 3). Fewer participants provided home practice logs but reported practiced an average of 4.8 days on the logs we received. These data are consistent with the 26-week follow-up interviews, wherein 19 participants reported practicing an average of 4.5 days in the prior week.

At the 52-week follow-up, 19 of 27 (70%) TC participants reported practicing the previous week (Table 3). Of those, they practiced an average of 3.6 days/week (median = 3 days) and 18 min/practice (median = 15 min, range = 3–60 min).

The instructors largely adhered to the protocol, although they sometimes changed the order of activities slightly and the time we specified for each section was not always adhered to because of the need to respond to the students. Two major protocol violations were reported. In one case, the instructor added a movement from the following week, whereas in the other, the instructor added a preliminary exercise that was not in the protocol.

Table 1 describes the treatment that UC participants received.

Intervention acceptability

At 12 weeks, TC class attendees rated the helpfulness of classes, on a 0–10-point scale, significantly higher than did HE attendees (Table 4). TC class attendees rated the helpfulness of the classes similarly on all follow-up questionnaires.

Table 4.

Acceptability of Interventions

| |

T'ai chi (TC) |

Health education (HE) |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Total N | Total N | |||

| 12 weeks | |||||

| Helpfulness of classes (0–10-point scale), N, mean | 26 | 6.6 | 10 | 4 | |

| Helpfulness of classes, N, median | 26 | 7 | 10 | 3.5 | p < 0.02a |

| Helpfulness of classes, N, range (minimum/maximum) | 26 | 0–10 | 10 | 0–8 | |

| Moderately or very likely to continue practicing TC (using HE information), N % | 77% | 60% | |||

| Definitely or probably likely to recommend TC (HE) classes to others | 26 | 92% | 10 | 50% | p = 0.01b |

| Patient Provider Connection Scale (PPC) Scale (1–5-point scale), N mean | 24 | 4.6 | 10 | 4.1 | |

| PPC Scale, N median | 24 | 4.8 | 10 | 4.1 | |

| PPC Scale, N range (minimum/maximum) | 24 | 3–5 | 10 | 3.5–4.8 | |

| 26 weeks | |||||

| Helpfulness of classes, N, mean | 25 | 6.6 | |||

| Helpfulness of classes, N, median | 25 | 7 | |||

| Helpfulness of classes, N, range | 25 | 0–10 | |||

| Moderately or very likely to continue practicing TC (using HE information), N % | 26 | 65% | 8 | 75% | |

| Definitely or probably likely to recommend TC classes to others | 26 | 96% | |||

| PPC Scale, N mean | 24 | 4.4 | |||

| PPC Scale, N median | 24 | 4.8 | |||

| PPC Scale, N range | 24 | 2.2–5 | |||

| 52 weeks | |||||

| Helpfulness of classes, N, mean | 25 | 6.8 | |||

| Helpfulness of classes, N, median | 25 | 8 | |||

| Helpfulness of classes, N, range | 25 | 2–10 | |||

| Moderately or very likely to continue practicing TC (using HE information), N % | 27 | 52% | 10 | 60% | |

| Definitely or probably likely to recommend TC classes to others | 27 | 89% | |||

Mann–Whitney U test.

Fisher Exact Probability Test.

At 12 weeks, 76.9% of TC participants said they were moderately or very likely to continue practicing TC compared with six participants (60%) from HE who said they were moderately or very likely to continue using HE information (Table 4). By 26- and 52-weeks, fewer TC participants were moderately or very likely to continue practicing (Table 4), whereas the HE participants were equally likely to continue using HE information at those time points.

At least 89% of TC participants reported they were definitely or probably likely to recommend TC classes to others at all time points (Table 4) compared with half of the HE participants at 12 weeks.

At 12 weeks, participants in both groups rated the instructor (facilitator) highly on the 5-point PPC Scale (Table 4). The highest item ratings were satisfied with instructor and trusted instructor for TC and satisfied with instructor and respected by instructor for HE. The lowest item rating was: “instructor understands me.”

Harms of TC or HE

One participant reported they could not exercise immediately after TC classes because of transient back discomfort.

Follow-up feasibility

Overall, completion rates for questionnaires were high, with follow-up rates of 88%, 91%, and 93% at the 12, 26, and 52-week time points (Fig. 1). They were slightly higher for the TC group. Attendance at in-person measurements was substantially lower (12 weeks:75%; 26-weeks: 67%, 52 weeks: 40%), with the highest attendance in the TC group.

Key learnings for improvement from focus groups

Key learnings for improving the next study are provided in Table 5 and summarized briefly here. Participants in all focus groups and UC survey disagreed on the best methods for recruitment (Table 5). Multiple HE participants did not understand the concept of randomization, whereas those in the TC and UC group did. TC and UC participants liked the idea of offering a TC workshop after a year for those in the control groups.

Table 5.

Focus Group Learnings from T’ai Chi and Health Education and Health Education and Surveys from Usual Care

| Domain | T'ai chi (N = 18) | Health education (n = 6) and usual care (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | Some would prefer mail and others email. They get a lot of mail from Kaiser. Some wanted text messaging. Multiple ways of communicating. | HE: Some would prefer email and others mail. Having Kaiser name on the envelope is helpful for bringing attention to that piece of mail. But some are overwhelmed by mail. |

| UC: 7 had no suggestions, others mentioned online recruitment, social media, KP newsletter, and providing more information about the study | ||

| Combination of over the phone and in-person screen | Let information staff at facility know about the study so people can find it in the building if they lose their directions. Did not like the signs as much. Sometimes the in-person screens were chaotic. | HE: Too much information by phone. Some were confused about how they got HE, they somehow thought they were going to get TC when they came to the in-person screen. UC: most fine, several wanted in-person appointments at their medical center. |

| Randomization | Liked randomization on the spot. They understood what randomization meant. Most but not all would have been willing to be in the control group. | HE: Some did not realize that they were randomly assigned to the HE intervention. UC: 10 of 12 participants knew this, 2 were confused about randomization. |

| Class comments (contextual factors, what they valued, how to improve) | Valued relationship with the study team and reminders to come to class. | HE: Everyone wanted TC, but most learned a lot. UC: all wanted TC, some more than others |

| Valued relationship with their primary instructor; some liked substitutes as well. Others found substitutes hard to follow because they did not teach identically. | HE: Wanted more guest speakers. UC: Not relevant (NR) | |

| Liked the step-by-step approach, but many wanted to learn more movements both in first 12 weeks and in tapered period of maintenance classes. | HE: Wanted more adult-focused education, with more time to share with each other during the class instead of just during the designated discussion. Felt this would engage participants more. UC: NR | |

| Would have liked to get to know group better; in the beginning class, is there a way to let people get to know each other better. | HE: Instructor asked pre-chosen questions even when they discussed those concepts earlier in the session. She should have skipped those slides. UC: NR | |

| During tapering of classes, it was harder for people to maintain motivation (as they kept doing the same intervention) | HE: An older facilitator might have been helpful; current facilitator was too fixated on getting through her outline. UC: NR | |

| Wanted a web portal to make comments; also an online option for completing home practice logs and some wanted text reminders. | HE: Need to be able to weave class discussion into the presentation; UC: NR | |

| Offer more support for keeping in touch (e.g., blog) with other class members to maintain motivation. | HE: Acknowledged the need to have a strong outline (like we did) as a back-up as needed. UC:NR | |

| Wanted the entire routine on each video. | HE: Logical progression of topics. Liked the slides. UC:NR | |

| Did not like needing to change DVDs to practice | HE: Liked class topics. UC:NR | |

| Some people wanted less talking on the videos and more action, but others disagreed. Some wanted imagery on the videos. | HE: Some topics were worth more than an hour and others less. UC:NR | |

| Importance of your instructor creating the video because of minor differences in teaching. | HE: Suggest allowing some topics to spill over into the next session if needed. UC:NR | |

| HE: Wanted class on housing options to be more specific. UC:NR | ||

| Consider a TC workshop for control group after 1 year | Thought this was a great idea for those in the control group; would have been willing to wait | HE: Did not like this option, it was “too long” to wait. UC: all 12 liked the idea |

| Environment | Wanted better space (no posts, liked mirrors) | HE: Wanted more comfortable chairs. |

HE participants reported that they learned new material and liked the slides but wanted handouts. They wanted the facilitator to spend more time inviting the group to share their experiences and their views on the topic rather than always finishing her presentation.

TC participants appreciated the class instructors and study staff. They wanted introductions to each other. They liked emails and phone call reminders for class. They wanted to learn more movements than they did. They reported more difficulty maintaining motivation during the maintenance phase. They used the home practice videos to supplement the classes rather than as superficial reminders of the movements and sequences. As such, they suggested front and back views of the TC movements on the video. Additional video suggestions are found in Table 5.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the study was feasible, had acceptable recruitment, good adherence by instructors to the class protocols, few dropouts, high follow-up rates for questionnaire outcomes, and an excellent safety profile. Participant adherence to classes was acceptable for both groups, although slightly higher for TC (and consistent with17,24 or better than other studies30,42,43). Most TC participants practiced at home. Compared with HE, TC participants rated both the helpfulness of classes and their likelihood of recommending the classes to other significantly higher. This was compatible with our goal of providing useful information for general health, but not for improving back pain. Nonetheless, more than half of participants in both groups said they would continue to practice (TC) or use the information they had received (HE) at 12-, 26-, and 52-week follow-ups. Given the promising data from younger adults,42,44 the value of TC for older adults with cLBP remains worthy of investigation.

Recruitment for classes is typically more challenging than recruitment for individualized treatments because of the need to hold both classes in one location at one time. Future studies should consider offering additional times for classes as well as multiple locations, actions that were not possible within the constraints of this trial. In instances where we knew why TC classes were discontinued, they largely reflected life events, which are likely in this population. It is unclear that most can be minimized. In addition, we plan to use participant feedback to improve the recruitment and enrollment process, including randomization.

We received useful advice about improving the TC intervention. The participants' need for consistency in language across TC instructors and video recordings was surprising to the instructors. In a larger study, instructor training should address this concern. We suggest selecting teachers by evaluating their form when practicing our intervention movements (using Yang-style) and their ability to teach. Qualified teachers would then undergo a rigorous training program to facilitate consistency in delivering the intervention.

We have many notes on how to structure teacher training to increase consistency among teachers. Training would include discussion of the TC “ingredients” explicitly included in the intervention (e.g., ritual, imagery), how to help participants create good habits of practice, focus on teaching foundational TC elements (e.g., posture, abdominal breathing), discussion of all class elements, discussion of common difficulties experienced in our feasibility TC classes, and sufficient practice teaching to facilitate natural consistency. In addition, we would create home practice videos for each instructor (or having a voice over for each instructor) and incorporate the suggestions offered in Table 5.

Robust fidelity monitoring would be needed. Such monitoring includes three aspects: adherence to the intervention (including prescribed elements of the intervention), differentiation (avoiding proscribed elements), and competence of the instructor.45,46 More studies monitor adherence and differentiation47 than competence; we did this with structured checklists. Researchers need to think carefully about what it means to be faithful to the protocol. For our TC intervention, we doubt that the language used by instructors must be identical. TC movements should be done in order. Yet, it may not be necessary to do the preliminary activities in order. Assessing the competence of the instructor, including knowing when they should deviate from a tightly structured protocol, may be especially important for optimal outcomes.45

In this feasibility study, we used master teachers. It is unlikely that such expertise would be available in all locations in a full-scale clinical trial, so the training program we described earlier may be critical to achieve the necessary level of competence.

One challenge for TC was maintaining motivation for TC practice in the maintenance period. It could be that most participants need a class structure to keep practicing. Future trials should compare multiple methods for achieving long-term practice.

Our choice of control groups merits further consideration. In Table 1, we describe the possible reasons for improvement in each intervention. Improvement in all three intervention groups could be due to the natural history of cLBP or use of other LBP therapies. We designed our HE sessions to additionally control for instructor and class support. Thus, any benefits of TC versus HE would result from TC classes and/or home practice. However, HE is an imperfect control because HE participants could make other lifestyle changes, such as increasing exercise or better nutrition.

Focus group comments suggested that relationships in the TC groups were closer with their instructors but more distant with classmates, while the reverse was true in HE. Whether these differences “cancelled each other out” or led to superior instructor/class support for one intervention is unknown. Because of such challenges with HE and our ultimate interest in whether the addition of TC improves UC, we think a UC group is an essential second control group.

In a future study, we would revise the HE intervention according to focus group recommendations (i.e., present key health messages for the HE class as class handouts, ensure that the facilitator is skilled with adult learning methods to enhance discussion and improve the class experience). To increase satisfaction and possibly adherence in HE, we would also plan to offer TC workshops to both control groups after their participation in the trial was completed. The in-person follow-up measurements were secondary outcomes and we would not recommend including these in future studies due to relatively low importance relative to barriers for participants traveling to the assessment facilities.

Study limitations included small size, which is expected in a feasibility trial, one geographic location, the inability to have two control groups for both cohorts, and most patients under age 75. Strengths of our feasibility study include two control groups, carefully developed TC and HE classes, video support for TC home practice, comprehensive outcome measures, and focus groups to capture suggestions for improving a new study.

Conclusions

We think that modified TC and HE interventions are worth testing in a full-scale trial. Before undertaking such a study, further work is needed to improve recruitment processes, refine the interventions, improve TC home practice materials, create handouts for HE, create training programs for TC teachers and HE facilitators, and create a TC workshop to offer the control groups at the end of the study. Enhancing fidelity to both interventions warrants further work as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kim Ivy for development of the TC protocol and Kim Ivy and Viola Brumbaugh for teaching TC classes, Peter Wayne for reviewing the TC protocol, Manu Thakral for assistance in developing the HE classes, and Emily Bandy for leading most of the HE classes. They thank Kristin Delaney for programming and John Ewing, Karen Walker, and Margie Wilcox for staffing the classes and other assistance with the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This project was supported by grant R34 AT009052 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official view of NCCIH.

References

- 1. Docking RE, Fleming J, Brayne C, et al. Epidemiology of back pain in older adults: Prevalence and risk factors for back pain onset. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1645–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rundell SD, Sherman KJ, Heagerty PJ, et al. The clinical course of pain and function in older adults with a new primary care visit for back pain. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:524–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnstein P. Balancing analgesic efficacy with safety concerns in the older patient. Pain Manag Nurs 2010;11(2 Suppl):S11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA 2008;299:656–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weiner DK, Rudy TE, Morrow L, et al. The relationship between pain, neuropsychological performance, and physical function in community-dwelling older adults with chronic low back pain. Pain Med 2006;7:60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Martin BI. Overtreating chronic back pain: Time to back off? J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:62–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Makris UE, Abrams RC, Gurland B, Reid MC. Management of persistent pain in the older patient: A clinical review. JAMA 2014;312:825–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barkin RL, Beckerman M, Blum SL, et al. Should nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) be prescribed to the older adult? Drugs Aging 2010;27:775–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cooper JW, Burfield AH. Assessment and management of chronic pain in the older adult. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2010;50:e89–99; quiz e100–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fitzcharles MA, Lussier D, Shir Y. Management of chronic arthritis pain in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2010;27:471–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whedon JM, Mackenzie TA, Phillips RB, Lurie JD. Risk of traumatic injury associated with chiropractic spinal manipulation in Medicare Part B beneficiaries aged 66 to 99 years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:264–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greendale GA, Kazadi L, Mazdyasni S, et al. Yoga Empowers Seniors Study (YESS): Design and Asana Series. J Yoga Phys Ther 2012;2:pii: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salem GJ, Yu SS, Wang MY, et al. Physical demand profiles of hatha yoga postures performed by older adults. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:165763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nascimento P, Costa LOP, Araujo AC, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for non-specific low back pain in older adults. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2019;105:147–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: A systematic review for an american college of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qin J, Zhang Y, Wu L, et al. Effect of Tai Chi alone or as additional therapy on low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. You T, Ogawa EF, Thapa S, et al. Tai Chi for older adults with chronic multisite pain: A randomized controlled pilot study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2018;30:1335–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wayne PM, Kaptchuk TJ. Challenges inherent to t'ai chi research: Part I—t'ai chi as a complex multicomponent intervention. J Altern Complement Med 2008;14:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hackney ME, Wolf SL. Impact of Tai Chi Chu'an practice on balance and mobility in older adults: An integrative review of 20 years of research. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2014;37:127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lomas-Vega R, Obrero-Gaitan E, Molina-Ortega FJ, Del-Pino-Casado R. Tai Chi for Risk of Falls. A Meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:2037–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeh GY, McCarthy EP, Wayne PM, et al. Tai chi exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:750–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chyu MC, von Bergen V, Brismee JM, et al. Complementary and alternative exercises for management of osteoarthritis. Arthritis 2011;2011:364319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ye J, Cai S, Zhong W, et al. Effects of tai chi for patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci 2014;26:1133–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang C, Schmid CH, Iversen MD, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Tai Chi Versus Physical Therapy for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:77–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang F, Lee EK, Wu T, et al. The effects of tai chi on depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Med 2014;21:605–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Deyo RA, Dworkin RH, Amtmann D, et al. Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low-Back Pain. J Pain 2014;15:569–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care 2002;40:771–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang J-M. Yang Tai Chi for Beginners (DVD Set). Miranda, CA: YMAA, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang C, Schmid CH, Fielding RA, et al. Effect of tai chi versus aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia: Comparative effectiveness randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2018;360:k851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stone AA, Broderick JE, Junghaenel DU, et al. PROMIS fatigue, pain intensity, pain interference, pain behavior, physical function, depression, anxiety, and anger scales demonstrate ecological validity. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;74:194–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schalet BD, Hays RD, Jensen SE, et al. Validity of PROMIS physical function measured in diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;73:112–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deyo RA, Katrina R, Buckley DI, et al. Performance of a Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Short Form in Older Adults with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Med 2016;17:314–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;73:89–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim J, Chung H, Askew RL, et al. Translating CESD-20 and PHQ-9 Scores to PROMIS Depression. Assessment 2017;24:300–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skapinakis P. The 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale had high sensitivity and specificity for detecting GAD in primary care. Evid Based Med 2007;12:149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roland M, Fairbank J. The roland-morris disability questionnaire and the oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine 2000;25:3115–3124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994;49:M85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Whitney SL, Marchetti GF, Morris LO, Sparto PJ. The reliability and validity of the Four Square Step Test for people with balance deficits secondary to a vestibular disorder. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Greco CM, Yu L, Johnston KL, et al. Measuring nonspecific factors in treatment: Item banks that assess the healthcare experience and attitudes from the patient's perspective. Qual Life Res 2016;25:1625–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45:626–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hall AM, Maher CG, Lam P, et al. Tai chi exercise for treatment of pain and disability in people with persistent low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:1576–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lipsitz LA, Macklin EA, Travison TG, et al. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Tai Chi vs Health Education in Subsidized Housing: The MI-WiSH Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:1812–1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hall A, Maher C, Latimer J, Ferreira M. The effectiveness of Tai Chi for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:717–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Crane RS. Intervention integrity in mindfulness-based research: Strengthening a key aspect of methodological rigor. Curr Opin Psychol 2019;28:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Crane RS, Hecht FM. Intervention integrity in mindfulness-based research. Mindfulness (N Y) 2018;9:1370–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mars T, Ellard D, Carnes D, et al. Fidelity in complex behaviour change interventions: A standardised approach to evaluate intervention integrity. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]