Abstract

Objective:

Many countries require examinations as a gateway to chiropractic licensure; however, the relevance of these exams to the profession has not been explored. The purposes of this study were to analyze perceptions of international stakeholders about chiropractic qualifying examinations (CQEs), observe if their beliefs were in alignment with those that society expects of professions, and suggest how this information may be used when making future decisions about CQEs.

Methods:

We designed an electronic survey that included open-ended questions related to CQEs. In August 2019, the survey was distributed to 234 international stakeholders representing academic institutions, qualifying boards, students, practitioners, association officers, and others. Written comments were extracted, and concepts were categorized and collapsed into 4 categories (benefits, myths, concerns, solutions). Qualitative analysis was used to identify themes.

Results:

The response rate was 56.4% representing 43 countries and yielding 775 comments. Perceived benefits included that CQEs certify a minimum standard of knowledge and competency and are part of the professionalization of chiropractic. Myths included that CQEs are able to screen for future quality of care or ethical practices. Concerns included a lack of standardization between jurisdictions and uncertainty about the cost/value of CQEs and what they measure. Solutions included suggestions to standardize exams across jurisdictions and focus on competencies.

Conclusion:

International stakeholders identified concepts about CQEs that may facilitate or hinder collaboration and efforts toward portability. Stakeholder beliefs were aligned with those expected of learned professions. This qualitative analysis identified 9 major themes that may be used when making future decisions about CQEs.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, Licensure, Certification/Standards, Internationality, Educational Measurement/standards

“There is no professional group . . . today that is pleased, much less sanguine, about the methods used to certify or license new candidates for practice.”

- William C. McGaghie1

INTRODUCTION

Qualifying examinations (QEs) are considered necessary by many professions and yet, as McGaghie1 described, have been the subject of much consternation. Since the early writings on professionalization, QEs have been recognized as a trait of professions. While the use of a QE does not define a profession, it is recognized by many authors as an important part of separating a profession from an occupation.2–10 Carr-Saunders,11 a seminal author on professionalization, stated that a profession is a vocation, the “entrance to which is only possible after passing an examination, taking the form of a test of special competence and following on a period of specialized intellectual training.” It has been opined by academics, practitioners, laypersons, students, and others that QEs are necessary for a variety of reasons, but most reasons relate to the importance of QEs to society.2–4,11

Price and colleagues12 presented a typology of QEs based on an exhaustive review of international requirements for medical licensure. They suggested that there are 4 options for licensure based on candidacy. In the first type, graduating students must pass a board exam in their country before licensure. In the second type, all prospective physicians, including those educated within the country and those from international programs, must pass a national licensing exam. In the third type, QEs are only for international graduates, and graduates from the national program do not sit for a QE. Finally, in the fourth type, institutional licensure, there is no independently administered examination, but candidates are considered qualified upon graduation from a training program. Such training programs may or may not be accredited by an external accrediting agency.

Similarly, in chiropractic, many jurisdictions require that candidates must pass 1 or more chiropractic qualifying examinations (CQEs) to be eligible for licensure to practice as a means of reassuring society of self-regulation of the profession. For this paper, we define CQEs (also known as certifying exams, licensing exams, or board exams) as those tests that relate to qualifying an individual for initial licensure. CQEs may be, and often are, administered by an organization independent from chiropractic training programs and we include this within our definition of CQE. In this discussion we do not include tests for specialty board certification or continuing professional development as CQEs.

QEs are high-stakes examinations and therefore receive a great deal of attention.1 There are numerous stakeholders involved with these exams. In jurisdictions where they are required, candidates are ineligible to practice without successful completion of the QEs. The public relies on practitioners having passed a QE as reassurance that the provider is competent and can practice safely. Accrediting agencies may assess teaching institutions on their board passing rates as an outcome measurement of student achievement. Training program administrators rely on researchers to produce data to identify variables that are important to successful completion of curricula and passing of examinations. The QE organizations must produce tests that are fair, reliable, and valid so that the public receives the reassurance it seeks regarding doctors being fit to practice. Licensing agencies rely on the QE organizations to provide scores in order to grant or deny licenses to candidates. Given the high stakes and wide range of stakeholders, it is unsurprising that such exams are a source of contention.13 These issues are not unique to chiropractic but exist as concerns for other healthcare professions that require a QE.1,12

However, in the chiropractic profession, there are additional important issues to consider with regard to CQEs. Chiropractic care is not yet available in all countries. Thus, as the profession develops in these areas, government agencies, regulators, and advocates will be confronted with the question of whether a CQE will be required and how it might be implemented. As healthcare systems transform, some jurisdictions may review and consider changing their CQE requirement in the future. Finally, the state of reciprocity is poor between jurisdictions, particularly countries and is the subject of debate.14 In all of these situations, decision making about CQE requirements could benefit from having an international perspective on these issues.

It is conceivable that changes to CQEs could be made without appropriate consideration of the stakeholders and the public that the profession serves. Knowing a wider range of stakeholder opinions and concerns pertaining to CQEs could be useful when considering the future of CQEs. At present, to our knowledge, there are no studies that have investigated stakeholders' perceptions of CQEs; therefore, this study aimed to fill the void related to stakeholder viewpoints.

The purpose of this study was 3-fold: to analyze the perceptions of international chiropractic stakeholders about CQEs; to observe if their beliefs were in alignment with those that society expects of learned professions; and to suggest how this information may be used when making future decisions about CQEs.

METHODS

This paper was organized according to the reporting guidelines for survey research suggested by Bennett et al.15 As this was a mainly qualitative survey with open-ended questions, not all items suggested by Bennett and colleagues were pertinent to this study.

Design of the Questionnaire

The survey was developed based on literature from the fields of healthcare, sociology, and psychology. This literature was obtained by searching PubMed, Scopus, PsychInfo, and Google Scholar. Search terms included professionalization, professions, qualifying examination, licensing examination, characteristics, traits, medicine, chiropractic, and various combinations thereof. The purpose of the literature search was to identify the key traits considered necessary to define a profession. Articles and books from this search were obtained, and pertinent information about professionalization was extracted. Relevant references from these sources were also retrieved.

The literature revealed that a number of benefits, controversies, facts, and myths exist about QEs. We developed the survey based on these writings.2–8,13,16–19 While reading the source materials, we took note of the concepts that those authors considered most important to professionalization, those that were most often misidentified as facts about professionalization, and the main stakeholder groups affected by QEs. The notes from these sources were used to create open-ended questions for our survey about perceptions of the benefits, myths, barriers, solutions, the future, and opinions regarding CQEs. Another open-ended question requested the name of the agency that administrates the CQE in the respondent's jurisdiction if a CQE was required. The remaining open-ended question gathered information on the primary role of the respondent (eg, faculty member, administrator). Respondents were asked to provide their demographic information and were offered the option to give permission to be acknowledged as a survey participant in the final paper.

Validation

The survey was piloted through peer review. Twelve peers (6 females) from the United States, Canada, Brazil, the United Kingdom, South Africa, France, and Australia were asked to pilot the survey as if they were respondents and then to provide critical commentary on the survey items. The peers were selected based on their expertise in the areas of chiropractic education and CQEs and their geographic distribution. Eight of the reviewers (4 females) completed the pilot process between July 24 and August 5, 2019, and represented the United States, United Kingdom, Brazil, South Africa, and Australia. The survey was then revised using the feedback from the peers. The final revised questionnaire (Appendix A) is available as online supplementary material attached to this article (www.journalchiroed.com).

Participants

To obtain a representative sample of stakeholder perspectives, we did not restrict the sample population to academia. The sampling frame was represented by the following: chief executive and chief academic officers of all chiropractic training programs worldwide as of August 2019, chiropractic students from all international regions, faculty members of all chiropractic training programs, accrediting body representatives, licensing board associations, CQE boards, researchers, presidents of all national chiropractic associations, private practitioners, and others listed below.

The sample was obtained from the list of stakeholders and included representatives of all groups obtained as follows. Academic program leaders were identified by searching the list of chiropractic training programs offered in the United States via the website of the Association of Chiropractic Colleges.20 International colleges and their leaders were identified by using the list of institutions available on the website of the World Federation of Chiropractic (WFC).21 Faculty members of chiropractic training programs were identified by personal contact. Students were identified through the list of leaders on the website of the World Congress of Chiropractic Students.22 Representatives of accrediting bodies, licensing board associations, and CQE organizations were identified by personal contact or through their respective websites. Leaders from all known national chiropractic associations were identified by the list of associations provided on the website of the WFC.23 Researchers from chiropractic institutions were identified by personal contact. Practitioners were identified by personal contact and by scouring recent journals with articles published by chiropractors in active practice. We did not attempt to recruit patients. However, we included this category and an “other” category as catchalls used in the event that we missed any particular stakeholder group. Suggestions for other potential survey participants were also sought from personal contacts.

The status of use of CQEs internationally is not known. Thus, we did not attempt to calculate a specific sample size. We attempted to contact representatives from all possible stakeholders. By including 2 academic leaders from each of the training programs, national representatives from all countries, and the other stakeholder groups, we felt the sample was representative of the study population.

Mode of Administration

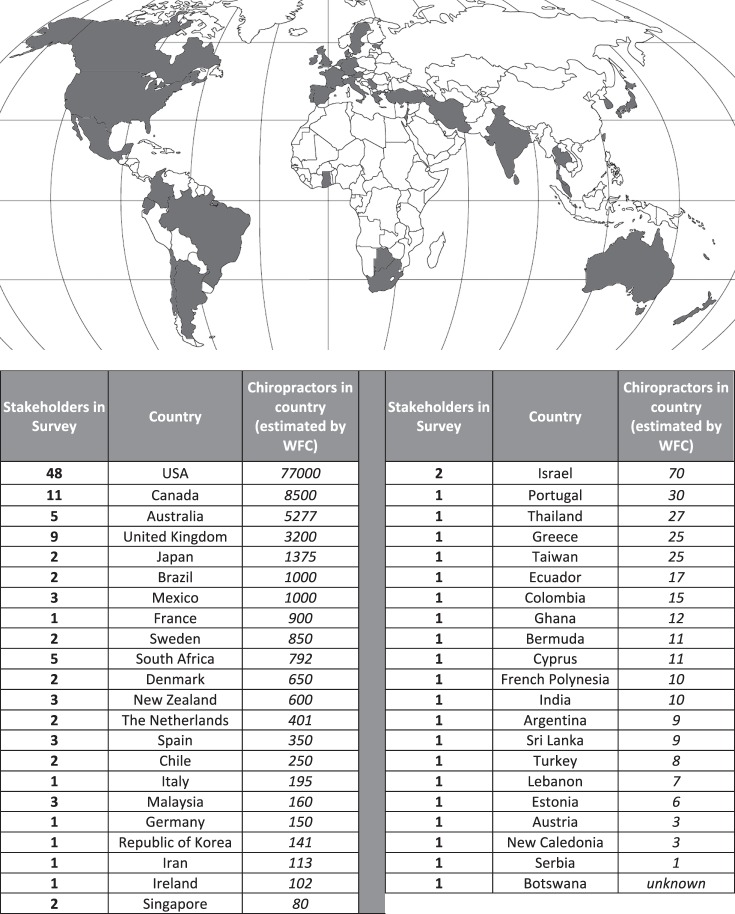

The survey was deployed from August 8 through 26, 2019, using the web-based software SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey, San Mateo, CA). Potential participants were first sent an email from the lead author informing them that they were being approached to take the survey. This email included the purpose and context of the survey, ethics information, and informed them that they would receive the survey link in a separate email invitation. This first email was used to alert potential participants that a second email with the survey link would be arriving in their in-boxes and also to test the sample for nonoperational email addresses. For those addresses that were nonoperational, we attempted to find a second email address via personal contacts or online searches. If no contacts were viable, the person was removed from the list. Once it was verified that an email was viable, the survey invitation with the link to the survey was sent to 234 people. A flowchart showing the recruitment of participants is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants.

Ethics

No financial incentives were provided to participants. As per the instructions, a partial or completed survey returned by the participant was considered consent to participate in the study. Participants were given the opportunity to provide their identifying information (name, affiliation) to be included in the list of participants in the manuscript. Those who did not give their information were not included in this list, but their data were included in the analysis. All data were deidentified and analyzed in aggregate, and no item responses associated with the person who provided them were reported in this paper. Data were kept securely on the SurveyMonkey platform until they were deidentified and stored on a password-protected computer in an electronic folder with a separate password. This study is part of an ongoing project examining the past, present, and future status of chiropractic educational research in order to make recommendations for enhancing research capacity. The project was reviewed and deemed exempt from review by the institutional review board of the National University of Health Sciences.

Data Analysis

The response rate was calculated by dividing the number of completed surveys by the number of valid email addresses. Representativeness by country was illustrated by comparing the number of respondents per country to the number of chiropractors registered in each country using data from the WFC. All data provided from each participant were recorded, including incomplete surveys. The first 2 authors (BNG and CDJ) then read the comments to identify patterns, themes, and categories. The qualitative method used was a practical and iterative process developed by Srivastava and Hopwood.24 It is a simple framework for qualitative analysis that employs a reflexive “process of continuous meaning-making and progressive focusing” as themes emerge.24 Questions that guide the process are related to what the data reveal, what the researcher wants to know, and the relationship between the data and what the researcher wants to know. The process does not rely on extensive coding of data and analysis via triangulation and other methods. It is a simple process designed for those who are not experts in qualitative analysis. The list developed by the first 2 authors was then further distilled by the authoring team via dialog.

RESULTS

Demographics

The response rate was 56.4% (134 completed surveys). Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the number of respondents at each stage of the survey process.

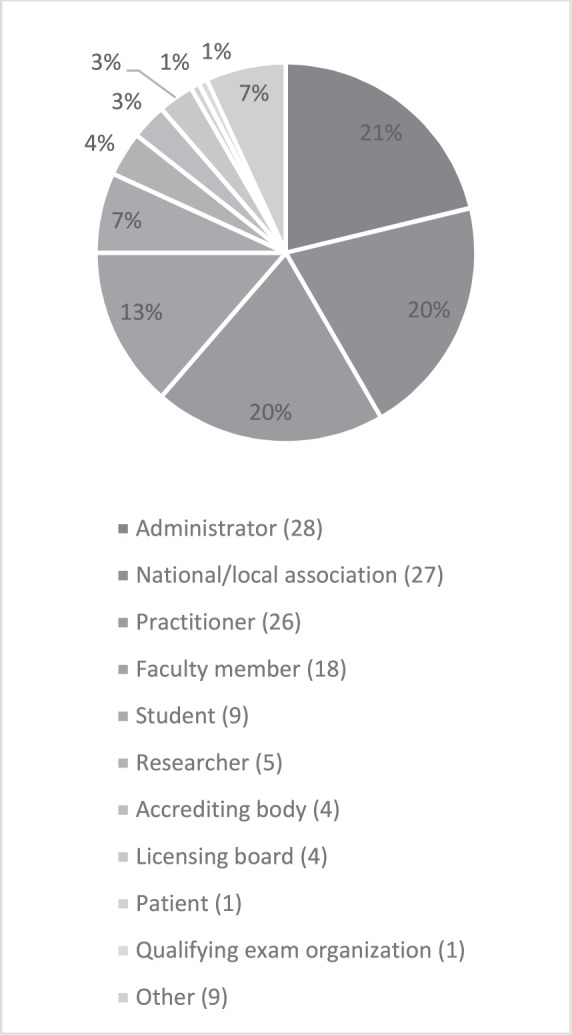

The greatest number of stakeholders represented administrators in chiropractic programs, national/local associations, practitioners, and faculty. The fewest stakeholders represented CQE organizations and patients. Figure 2 shows the number of participants per stakeholder category.

Figure 2.

Representation of stakeholders by self-selected category.

Females represented 28% of respondents (n = 37). Of the 125 participants who offered their birth year, the age range was 21 to 80 years of age. The mean women's age was 46.3 (median = 44.5 median), and the mean men's age was 54.0 (median = 55).

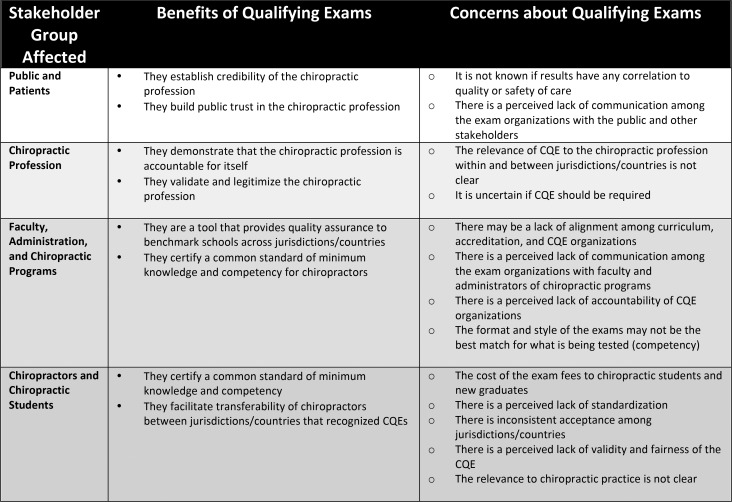

Respondents represented 43 countries. The number of respondents compared to the number of chiropractors per country, with the greatest number from the United States and Canada, is shown in the geographic map in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Participants' countries and estimated population of chiropractors per country as estimated by the World Federation of Chiropractic (WFC).

The majority of respondents (85.6%) provided consent to be acknowledged in the participant list (Appendix B, available as online supplementary material attached to this article at www.journalchiroed.com).

Qualitative Findings

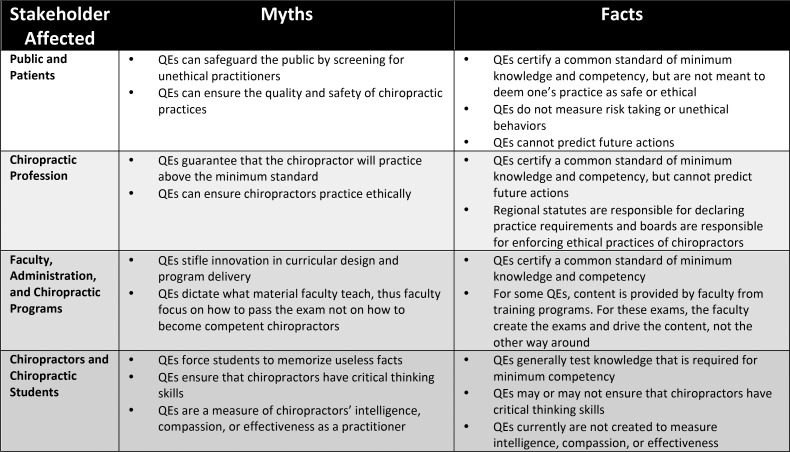

Figure 4 provides a summary of the main concepts presented in the literature about benefits and concerns of QEs and the groups the literature suggest are affected by QEs. The survey respondents submitted comments about CQEs that addressed all of the items, demonstrating alignment with societal values. There were many similarities in comments about the 4 open-ended questions related to concerns, solutions, thoughts for the future, and other comments. Respondents mentioned other items they felt were important and related to CQEs. Because of this, these question responses were collated into 9 topic areas for the sake of organization and presentation, which are: 1) whether CQEs should be required; 2) portability; 3) quality/safety of care; 4) cost of examinations; 5) alignment of curriculum, accreditation, and CQE; 6) accountability of CQE bodies to stakeholders; 7) validity/fairness of exams; 8) competency-based and higher order examinations; and 9) communication between testing organizations and stakeholders. Myths (ie, perceptions that are untrue) were clustered into concepts that mainly included misperceptions about what the exams were capable of doing and the creation/content of the exams. These are addressed in the discussion.

Figure 4.

Benefits and concerns related to key stakeholder groups that were identified from the literature and that survey respondents identified as important.

DISCUSSION

Profession and Professionalization

Professions develop in response to actual or perceived needs of society and require specialized training, knowledge, and skills.5,18 Professions are afforded privileges by the community allowing the profession to determine its own standards and control over training via accreditation, control over admission into the profession by completion of training in an accredited institution, and control via a licensing system to screen for those qualified to practice.6,8,10,25–27 Thus, professions are accountable to those served and to the wider society.18,28 Such a privilege, “. . . is given by, not seized from, society, and it may be allowed to lapse or may even be taken away.”26(p73)

Sociologists point out that one of the screening methods that follow the requisite training requires that candidates demonstrate competence by passing a test or a similar type of certification.2–10 In their comments, respondents of this study stated that CQEs are an important part of the social contract between the chiropractic profession and society. Respondents stated that they felt CQEs help to certify a common standard of minimum knowledge and competency, aid in improving public trust, serve as a quality assurance tool, and help to validate and legitimize the profession. Thus, many of their views were in accordance with the literature pertaining to professionalization and the traits of professions that are expected by the public.

Themes Identified in the Comments

Here we provide a nonhierarchical analysis of the 9 main themes that emerged from the comments, as the methodology did not employ a mechanism to assign levels of importance.

Whether CQEs Should Be Required

This topic emerged as important for many respondents. In some jurisdictions, there may be no CQEs. Other jurisdictions require a CQE in addition to graduation from an accredited program; others require just a CQE; and others require more than 1 CQE.14 Opinions varied with regard to a need for CQEs. Some respondents felt that CQEs are necessary and others did not. Essentially, what the chiropractic profession is grappling with is what type of QE, if any, may be best for the profession.

Proponents commented that CQEs are necessary to demonstrate a minimum level of professional knowledge. One respondent said, “I would like to see other countries that don't have qualifying exams to work to adopt them. In my opinion, it builds credibility with other professions knowing that we are held to a high standard before earning our license.”

Others felt that CQEs standardize the performance expectation in a manner that is independent from the training programs that have control over the quality of curricula and therefore the competence of graduates. Thus, the concern is that the CQE may set the bar so that the decision is made external to the training program. This is also an ongoing argument in medicine in favor of having QEs.12,13 For Europe, more medical educators preferred to have national licensing examinations than pan-European examinations, mainly from the perception of protecting the public from foreign medical graduates who might not have the same level of training, but also with regard to familiarity of language.29 Some respondents also felt CQEs are necessary in certain situations, thereby reestablishing their demonstration of requisite knowledge. For example, “Maybe have a cut-off limit: For fresh grads up to 5 years post-graduation you don't need to do board exams. For people that move to a very different jurisdiction (i.e. country/continent) and for people that have left the profession to later re-enter.”

These positions are supported by assessment experts in medicine. Swanson and Roberts30 predicted that QEs will become more common internationally because of the increase in the number of international medical schools, variation in quality of training, and level of familiarity of foreign doctors with local healthcare systems, cultures, and language.30

Opponents to CQEs felt that they are unnecessary. One perception is that the chiropractic profession developed outside mainstream medicine and universities, particularly, but not solely, in the United States. This situation necessitated the requirement of CQEs to provide a standard. Those with this perspective questioned if a CQE is necessary outside these countries. The argument is that training programs that developed after those in the United States, or have subsequent to their development aligned themselves with the higher education systems in their country, do not need CQEs. The argument is chiefly based on the contention that such programs have rigorous processes within their internal structures that are aligned with the requirements of the accreditation agency they fall under, the legislative body in their country, and higher education requirements in their country. This means that those graduates should have the requisite competencies to practice. Thus, the use of external CQEs may suggest that the training programs, reviews, and reaccreditation processes may be of insufficient quality.

A consistent position from opponents of independent CQEs was that the exams are not needed if one has graduated from a training program accredited by 1 of the 4 global Councils on Chiropractic Education, 3 of which are members of a body known as the Council on Chiropractic Education International (CCEI). If training programs were evaluated by accreditation agencies using rigorous standards, then variability in quality across training programs may be true.19 However, there are few studies that investigate this idea in the health professions and none that we are aware of in chiropractic. Said one respondent, “There should not be a chiropractic qualifying exam for those who graduated from CCEI accrediting bodies or CCE-USA. However, there is a need for those graduates from non-CCEI accrediting bodies or CCE-USA to ensure the minimum standards are met.”

Our survey defined CQEs as being administered by an organization independent from the training program, which could have influenced the respondents' comments as either for or against CQEs. Some respondents advocated that the determination of competence should be made by the training programs. For example, in replying to the question about what the respondent would like to see as the future of CQEs, one respondent replied, “To not be necessary! Ideally, all chiropractic institutions will produce the same high standard of chiropractors, thus eliminating the need to check the grads again.” Jolly19 posits that this may be an invalid argument. In Australia, for example, 49% of complaints about health care come from only 3% of the workforce.19 This suggests that accreditation or a QE may not necessarily relate to variability across training programs.19

The foregoing arguments about institutional licensure and accreditation may not be valid. It is apparent that many licensing authorities do not rely on the supposed quality of the teaching institutions, as evidenced by QEs in multiple countries where medical education is part of prestigious accredited universities and candidates are required to take a QE. Such examples are Germany, Switzerland, the United States, Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, and others.12 Furthermore, if perceived quality of education and alignment with accrediting and governing agencies is considered adequate to license doctors, then it might be questioned why the General Medical Council of the United Kingdom, after decades of using institutional licensure, will implement a national medical licensing examination in 2023 for UK medical students and for all international medical graduates who have previously taken the Professional and Linguistics Assessment Board.31

Respondents indicated that regardless of whether they were administered by an independent organization or approved via institutional licensure, some form of examinations and vetting process is important to proclaim professional candidates competent and honor the profession's pact with society. At what point in the educational process they are administered and by what vetting body, as well as many other logistics, represent current areas that need further exploration.

It is possible that some of the divergence in opinion about the need for independent CQEs originates in the reasons that jurisdictions adopted them. These reasons are largely out of the control of the chiropractic training programs because they are essentially legal hurdles. Thus, the training programs are unable to unilaterally decide to have or not have a CQE in their respective jurisdictions.

United States.

In the United States, the CQEs are essential since they are required for chiropractors to practice legally. In the formative years of the chiropractic profession in the United States, chiropractors argued that they possessed a specialized body of knowledge.32 The dominant healthcare profession (ie, orthodox medicine) controlled the licensing examinations in each of the states and was opposed to chiropractic from its inception.33,34 To legally practice, chiropractors were expected to take the same examinations as medical doctors in order to obtain a license to practice.33,34 This typically involved a test of basic sciences and a licensing examination, and each state had its own examinations. The overriding issue was that these examinations had been created with the express intention to keep chiropractors from obtaining licensure and therefore deemed them as illegally practicing medicine or osteopathy without a license.35 Therefore, in the absence of QEs designed specifically for the chiropractic profession, chiropractors were convicted and imprisoned for practicing medicine or osteopathy without a license in the states where QEs were required for licensure.36 The number of incarcerations was significant; hundreds, if not thousands of chiropractors were jailed.36 Imprisonment of chiropractors continued into the mid-1970s.37 As a consequence of this situation, there was a need to create licensing laws in each state, which created a variety of scopes of practice.38 Because each state developed its own CQE, the form and content of each examination was unique. Changing to a status of institutional licensure would require the majority of jurisdictions to repeal laws that currently allow chiropractors to practice chiropractic and may put chiropractors' professional status in jeopardy. Additionally, even if the chiropractic profession wanted to eliminate CQEs, this would be unlikely given these circumstances.

Chiropractic, as a form of healthcare, has been recognized legally in many countries after the profession first began in the United States in the late 1800s. Because its development and legal recognition occurred at various times and in different cultures, each area has its own way of recognizing chiropractic depending on the circumstances in which its legal status was obtained. As examples, the following describes and compares the differences in examinations and licensure in 4 additional countries to emphasize the variations among locations.

South Africa.

Institutional licensure is required in South Africa, where the attainment of rights to practice developed in a different fashion. In South Africa, the statutory council requires that graduates complete an internship program. This internship requires the completion of (1) an academic component comprising 75 hours within designated categories and (2) a practical/work experience component comprising 600 hours within designated categories.39 An examination is required only in the event that student candidates have not practiced for a period of more than 6 months. This examination is used to assess knowledge before the intern is allowed to continue an internship to completion prior to consideration for registration. Should the intern be found wanting through this examination, intern-specific remedial action is developed in order for the intern to address weaknesses prior to reentering the internship process. All portfolios are vetted by an internship committee against the published national guidelines. Additions are often requested for areas that are incomplete; this is then followed by a meeting between designated committee members and the intern prior to recommendation of the intern for registration.

Spain.

In Spain, since chiropractic is not regulated as a profession, there is no CQE. In general, there are no QEs for the majority of professions in Spain. In medicine, for example, once an individual has completed the requirements for graduation and the institution has issued a diploma, the graduate may apply for registration with the professional board. For a foreign graduate, the process is straightforward. The candidate must provide a notarized copy of his or her transcripts as well as a diploma and have them legalized in Spain. The documents need to be translated by a sworn translator and submitted to a committee of the Ministry of Education, together with a copy of all syllabi of all courses described in the transcripts. The committee of the Ministry of Education then analyzes the documentation and determines if the credits and subjects studied are equivalent to the education provided in Spain. If so, the committee issues a certificate of validation and homologation that allows the candidate to register with the professional board.40 In the case of chiropractic, the profession is self-regulated through the national chiropractic association. If it ever becomes regulated by law, the most likely scenario would be the one applied to the major health professions (eg, medicine) in which QEs are nonexistent.

Canada.

In Canada, the CQEs are independent licensing examinations, the content of which is established through a professional practice analysis and blueprint validation study. The exams consist of a 3-step process: Part A, which may be taken within 10 months of graduation; Part B, which may be taken within 6 months of graduation; and Part C, which may be taken within 3 months of graduation. All applicants must be graduates of, or enrolled in, a Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE)–accredited chiropractic educational institution. To a large extent, Part A tests chiropractic knowledge and to a lesser degree, interpretation of patient history and laboratory findings. Part B has less emphasis on rote knowledge and more on gathering patient data. Part C emphasizes physical examination skills.41

United Kingdom.

In the United Kingdom, the statutory regulator (the General Chiropractic Council) currently requires chiropractors having graduated from educational institutions outside the European Union to undertake a test of competence.42 This requires candidates to submit a portfolio of evidence and appear before a panel of examiners. They are required to demonstrate that they meet standards of competency set out in The Code: Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics for Chiropractors42 and that they are capable of practicing safely.

Solutions offered by survey participants were sparse with regard to changing the relative need for CQEs, other than to raise the quality of all training programs to an agreed upon international standard. One respondent commented, “We need support from world organisations.” Currently, countries award degrees ranging from bachelors level through clinical doctorates and some with further required training. The academic rigor between the awards is unknown but is suspected to be negligible. Should leaders in the profession desire to work toward a common international standard of education, we propose consideration of a higher degree that is the same level of educational attainment and to work through international agencies to coordinate this process.

Portability

Stakeholders voiced concern that the differing CQEs between countries have a profound effect on reciprocity of licensure, portability, and the international growth of the chiropractic profession. As one respondent stated, “Lack of standardization between jurisdictions can inhibit movement of practitioners from one jurisdiction to another.” The lack of standardization of examinations may be reflective of the deficiency of jurisdictional and scope of practice standardization. Thus, no matter how much debate centralizes on standardizing examinations, it will likely be hindered because the scopes of practice between jurisdictions are vastly different.

International portability has long been a concern of chiropractors.14 As recent as 2018, a point of consensus among international chiropractic educators at a recent conference was that “public confidence in chiropractic educational standards may be enhanced by global consistency in accreditation and assessment.”43 At the current time, there are few reciprocal agreements between countries. As it was with the need for CQEs, an issue at hand is that of the perceived quality of the education provided in all jurisdictions. Members of some jurisdictions feel that other jurisdictions contain some chiropractic training programs with lower educational standards, resulting in chiropractic graduates of inferior quality. Thus, representatives responding to the survey felt that mobility between countries should be based on whether a chiropractic training program is accredited rather than if a chiropractor can pass a licensing examination. As well, language in policies for the US Department of Education pertaining to foreign-trained chiropractors desiring to become licensed in the United States plays a part. Even if educational bodies can come to agreement, candidates coming from different countries still have to comply with local laws and therefore would still need to pass licensure exams in order to practice.

This is echoed in medical education literature where leaders of some jurisdictions do not feel that graduates of all colleges should take the same examination because portability should rely on the quality of academic programs.9 Also of importance is that jurisdictions have scopes that are not only based on historical development but also on the healthcare strategic imperatives in the country, and these are related directly to the patient disease profiles that are specifically unique to each country. Disorders that are highly prevalent in one jurisdiction may not be a concern in another, which introduces a hurdle to the international standardization of CQEs. Thus, the responses to the survey seem to reflect the reality of the present situation pertaining to the role of CQEs in aiding the mobility of chiropractors across borders. An underlying assumption here is that CQEs have a role in aiding mobility; this has not been answered in the chiropractic context based on the scope of practice variations between jurisdictions. It is possible that respondents and those holding similar opinions can be reassured knowing that the present situation in medicine is also problematic.9,44

We postulate that the struggle with this issue is merely a sign of an international educational system that is not yet mature. As said by William Potter45 in 1900:

It is, however, quite out of place to expect that such reciprocity can be established at present, while the methods of education are so different and while the preliminary requirements are so variable. It would be manifest injustice for a State that now demands a fixed and definite standard with reference to the granting of State license to practice, of those educated within the State, to admit to the same privileges those educated in another State where the standards are lower. Reciprocity is the final stage of this great reform, and is not to be seriously considered until all the conditions precedent thereto are fulfilled.

Proposed solutions related to achieving a more desirable future for reciprocity revolved around international collaboration and standardized tests internationally. Some respondents felt that the solution, in part, could involve the use of examinations prepared through the International Board of Chiropractic Examiners, while others dissented from this viewpoint. As the profession aspires to greater global and national jurisdictional reciprocity, the realities of the legal aspects of licensing will need to be addressed by international consensus. Some of the complexities of this process are being investigated by the International Chiropractic Regulatory Society and the Congress of Chiropractic State Associations.

In future discussions on standardization, stakeholders may consider lessons learned in other healthcare professions. The issues of quality of education, accreditation, and independent versus institutional licensure will also need to be addressed in order to make strides in this area.

Quality/Safety of Care

Comments included a concern about how CQEs might affect the quality or safety of care. Some respondents felt that CQEs provide a degree of protection against substandard care, but others felt that this is not the case. One respondent stated that a benefit of CQEs is that “the chiropractor will practice at or above the minimum standard of knowledge and competency.” Yet another respondent stated that a myth of CQEs is “that they are [an] accurate representation of capability and fitness to practice.”

These sentiments are similar to those in the literature. It has been advocated that QEs demonstrate that graduates are fit to practice and improve the quality and safety of health care.13,30,46 For example, for the Step 2, Clinical Knowledge examination of the US Medical Licensing Examination, there is an inverse relationship between each earned point on the score of the exam and mortality.47 However, the extent to which data demonstrate that passing a QE offers greater protection to the public is lacking.48

Many authors argue that such data represent only associations between exams and quality of care and that there is a lack of evidence supporting a cause and effect relationship.12,13,19,44,49 Such an argument is shown in a study of 30,288 malpractice claims matched to physicians. That study reported that doctors who had graduated from certain medical schools had higher rates of malpractice lawsuits filed against them, even though they had passed their QEs.50 Thus, the argument is that if QEs were protective, these examinations would have caught those doctors with malpractice allegations.19 However, this suggestion assumes that all cases of malpractice were in relation to clinical competence rather than issues of moral or ethical breaches and indiscretions and that the allegations were true.

The chiropractic literature is similar with regard to studies on CQEs; the available evidence is related to association between variables and passing board exams, not on if the exams have an impact on patient care. After searching the chiropractic literature and receiving input from the authors of this paper, we were unable to find a single paper pertaining to passing a CQE and the provision of safe or high-quality care. In short, QEs reassure the public that doctors are safe, but reassurance is not the same as conclusions based on scientific evidence.51

Greater clarity of these issues may include conducting research into the potential effects of CQEs on quality and safety of care.9,48 The process would be complex and time consuming48 and would involve case-control, cohort, or randomized trial types of research designs. At issue here are the costs, materials, personnel, and ethics involved in conducting such studies. Because healthcare professions do administer tests to reassure society that its members are practice worthy, it would seem that this is an important area for research. Should the profession decide to move forward in this area, it will need to decide if this is a research priority for which research capacity is available or can be created.

Cost of Examinations

Concerns included expenses related to CQEs. Many were concerned about the financial burden on candidates, the majority of whom are students or recent graduates with substantial loan debt. Such costs include registering for the examinations and travel to the location of the exam. As well, the cost to the profession of maintaining both accrediting systems and CQEs was raised in responses to the survey. Said one respondent, “Therefore currently there is an over subscription of money into having both the accreditation system as well as the examination system—money which could be spent more wisely on research in any sphere.” In low-income areas, adoption of CQE methodology similar to that in Canada and the United States could be cost prohibitive.

Some respondents were concerned about expenses required to provide psychometrically sound exams, which require qualified personnel, appropriate resources, and proper test item analyses. Whether CQEs are required for all candidates or just foreign graduates, the concern regarding cost is relevant. Costs are also borne by the candidates via the exam registration fees. These issues are not unique to chiropractic and are echoed in other health professions' literature.9,16

Solutions offered by respondents and available in the literature include having testing sites remote from main testing centers and web-based platforms overseen by certified proctors. While such changes may introduce short-term increases in costs for development, they may reduce financial burdens on stakeholders in the long run.16 Respondents also suggested that CQE organizations try to reduce their operating costs. Decision makers may want to consider conducting a needs assessment and a cost-benefit analysis with these suggestions in mind before making future decisions about the implementation of CQEs.

Alignment of Curriculum, Accreditation, and CQE

Concerns from respondents included alignment of curricula, accreditation, and use of CQEs. Some suggested that innovation in curricular design and pedagogy are negatively affected by CQEs and that qualifying exams cause students and faculty to focus on how to pass the exam (ie, drive learning), not on how to become competent doctors. Such concerns are echoed in the literature.13,16,19 Although assessment may drive what is learned, it is not accurate to say that it drives the learning process.19 If assessment has not been part of the curriculum, it is not a comprehensive or sufficient solution to qualify competent practitioners.19 It is also important for assessment to be based on instructional theory and to potentially incorporate both assessment for and of learning.52 Another concern is the selection of textbooks that may be approved for the CQE, as this would likely influence test content. Some commentators voiced concerns that student aggregate CQE scores could be an unfair representation of the training program as a student achievement benchmark.16

Solutions were offered in the comments. Several comments proposed that training program, accrediting agency, and CQE organization leaders work collaboratively to ensure that there is alignment of CQE content with the curricular content of chiropractic programs and accreditation standards. Comments suggested that accreditation and QEs are not mutually exclusive and may help in competency assessment if used in a complementary manner.16 Several participants asked for clearer guidelines for curriculum design and for these to be aligned with the expectations of the CQE administrators. How prescriptive this might be and its potential effect on accreditation standards and relationships between accreditors and training programs were not mentioned. As one respondent said, “It would be great to see that they not only support what is taught at chiropractic institutions but that they are connected to the accreditation bodies in which they serve.” However, we must be mindful that it is not the role of CQE organizations to support institutions; they are there to provide a test that candidates must pass to become members of the profession.

Many comments showed that collaborative work among the training programs, qualifying organizations, and accrediting agencies is valued, and future efforts involving this kind of work would be welcomed solutions. One person wrote, “This should be a collaborative approach to improve chiropractic education.” Another found current practices as a continuing solution, remarking, “I would like the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners board to continue to provide actionable data to improve the curriculum.” It seems that there is a struggle to have curricula, accreditation, and CQEs optimally positioned, but this is a process of continuous improvement and quality assurance. Collaboration of groups outside the jurisdictional group allows the groups to work together; however, this is not necessarily approved or sanctioned by the jurisdiction and therefore may not achieve the intended aims of improved mobility. As leaders move ahead with the future of CQEs, knowing that collaboration between entities is valuable to the stakeholders can be useful in creating and changing the CQEs and aligning the needs of the various stakeholder groups.

Accountability of CQE Bodies to Stakeholders

Concerns were voiced about how the various vetting bodies may be influenced by external pressures. How these influences might affect actions of the qualifying bodies was also mentioned. Some respondents felt that trade organizations exerted too much influence on CQE organizations. Some participants felt that there is a tepid relationship between the US Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards and the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners that may detract from the primary purpose of qualifying practitioners. Some participants felt that exam registration fees could be a financial motivator for CQE organization. Some suggested that qualifying agencies sometimes act independently and contrary to stakeholder opinion of best courses of action. Commentators mentioned that future considerations include increasing the transparency of qualifying organization operations, test development, and independent third-party oversight. Specific methods for achieving these solutions were not offered.

Validity/Fairness of Examinations

A variety of concerns were expressed regarding the validity or fairness of CQEs. One issue was that variability of concentration on subject matters between training programs may lead to candidates receiving poor marks or failing exams. As one person remarked, “I do not believe that all of the content on examinations is of equal value and should prevent an individual from licensing. For example, specific listing systems not used by all program or specific elements of chiropractic history/philosophy probably shouldn't stand between an individual and licensure if all schools don't teach it.”

Some comments reflected a concern that candidates who might be good in practice but are not good test takers could be excluded from the profession. Thus, the examinations may not screen for competence in practice but competence in taking a test. This begs the question if the right assessment tool is being used to measure fitness to practice. Other participants were concerned that it is difficult to demonstrate the breadth and depth of knowledge using the CQE process. One respondent commented, “Qualifying examinations seem inherently limited in their ability to effectively operationalize clinical competency beyond some lower limit of basic clinical knowledge and psychomotor skills.” Furthermore, there was some concern about the variability of examination contributors on written and practical exams and reliability between examiners on practical exams. These concerns are shared in the broader literature. One author has questioned whether QEs in medicine serve as a test of competence, asking, “Don't they all pass eventually?”13 The question is, “What is the eventual fail rate for jurisdictions with QEs?” Finally, there is concern seen in some comments and some literature that QEs may be unfair for foreign graduates since their curricula were not from the country in which they wish to relocate.13

Solutions were offered by respondents. Some suggested that more contributors from academic institutions be involved in the test creation process. Recommendations also included assuring that contributors be contemporary in their knowledge and skills of chiropractic. Some respondents also suggested the inclusion of people from other healthcare professions in the test creation process to provide an external perspective or review on the examinations. Finally, there were several recommendations to provide psychometric training or advanced psychometric training for people responsible for preparing examinations, if those personnel were not already trained in these theories, concepts, and skills. While it is known that some CQE organizations incorporate many of these suggestions as part of regular practice,53,54 this may not be the case across jurisdictions or within institutions where institutional licensure is used. These concerns and solutions brought forward by the stakeholders of this survey could serve as worthy items for CQE organizations and institutions to consider in the future.

Competency-Based and Higher-Order Examinations

Some respondents reflected that it is unreasonable to expect that every element of a chiropractor's knowledge and skills be tested in a single CQE. Comments expressed a preference for directing questions to common competencies and behaviors required in practice. One respondent commented, “If there are competencies set by the accrediting body, the examinations should assist in assessing the competencies.” These comments are similar to those in medicine where concern lies in the degree to which qualifying examinations match competencies expected to function in practice and that patients expect.9,49 As advocated by Tamblyn,48 if the potential impact of an examinee's performance on patient outcome is of interest, then the priority should be placed on evaluating performance in the subset of clinical situations where medical intervention is most strongly linked to the realization of better or worse patient outcomes. Of course, this requires that it is known what interventions are actually linked to patient outcomes.

Consensus exists that there is much work to be done in chiropractic education with regard to the use of competency-based curricula and assessment. International educators agreed at the 2018 WFC/Association of Chiropractic Colleges 10th Chiropractic Education Conference in London that chiropractic competency-based curricula should be seriously considered.43 Chiropractic lags behind medicine in this effort. As has been suggested by others,55 we recommend that if the chiropractic profession seeks to shift toward a competency-based model of assessment, then outcomes, not time spent learning, are of greatest importance. Should the chiropractic profession turn its attention to assessing students in the essential elements necessary for practice and their ability to be trusted to carry out these skills, then the critical variables are learning and assessment, not time.55

Solutions included creating CQEs that are outcome and competency based. Thus, the required competencies or outcomes would be outlined by the appropriate bodies, and then candidates should be assessed on those factors. Other solutions were to assess more clinically relevant materials and develop measures on competencies. For instance, one recommended that the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners could have questions on examinations that are matched to the CCE USA meta-competencies throughout examinations, which could assist training programs that utilize board exam pass rates as an external measure. Those conducting training programs would benefit from knowing who is performing higher in each of the competencies and be able to consider adapting the training program to the better-performing institution. Such changes would require the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners, CCE, and licensing boards to collaborate. Some suggestions were that available QE formats and experts in other healthcare professions could be resourced to improve competency-based assessment. Considering the direction of healthcare education, it seems that test creators and agencies should consider the development of competency-based CQEs. We also observed that none of the respondents mentioned that the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners in the United States produces the Practice Analysis and partly bases assessment on the Parts III and IV exams on this study of thousands of chiropractors in practice.53 Some significant work has been done with the Practice Analysis as a step toward competency-based CQE, and further work in this area could provide more solutions for the future.

Several respondents advocated for testing bodies to review examinations for topics most in accordance with the chiropractor that the profession desires to produce and that the public needs. Commentators also suggested making questions that test at higher levels of Bloom's taxonomy of the cognitive domain.56 These worries were not directed specifically at competency-based testing but at test questions that explore knowledge most needed in clinical practice. Medical educators have similar concerns.49 There was also concern that questions from some CQEs are not adequately based on scientific or clinical research. Additional comments pertained to what was perceived to be some level of redundancy of multipart examinations and that some parts could be combined. Combining parts might allow for more effective assessment of higher-order thinking and reduced costs for candidates.

Solutions were proposed. When writing about what they would like to see in the future for CQEs, one person wrote, “Design questions in a short clinical vignette format (appropriate to level of understanding at Part I) similar to what the USMLE has done for years. This will allow the exam taker to demonstrate concept integration and problem-solving skills in a relevant manner.”

Respondents suggested that test items reflect more current recent scientific or clinical literature and that they could be verified by the literature. Comments from respondents focused on whether candidates are adequately and appropriately tested on the most practice-relevant content. This reflects a concern about upholding the expectations of the public.

Communication Between Testing Organizations and Stakeholders

Stakeholders demonstrated a desire for improved communication with their qualifying organizations. Comments centered on inefficiencies in communicating with candidates, especially with regard to providing clear guidance on the requirements to sit for CQEs. Further concerns were about methods used to determine the number of questions per examination and the transparency of scoring.

Respondents provided several potential solutions for the perceived issues. They asked for improved communication between all stakeholders. They asked to have information about how the CQEs are scored published in terms that are understandable to most stakeholders. It was suggested that detailed test plans be available. One participant wrote, when stating what the future of CQEs could be, “Provision of a more detailed test plan–even if it was a list of conditions by system, or a list of enzymes/reactions, or a list of other content to be sure to know, even if of course it does not all end up on the exam.” It was also recommended that CQE organizations not just improve communication about examination preparation, methods, and results but also the potential social importance of having some form of a CQE. The information on communication should be helpful to CQE organizations and considered by leaders if they are considering implementing or changing their CQE process.

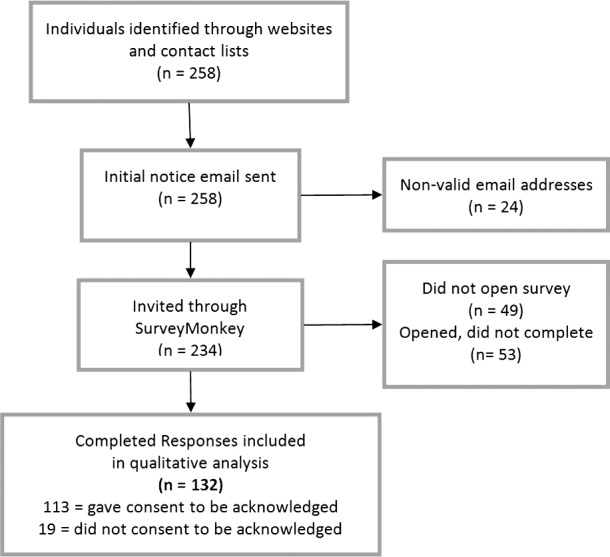

Consistency of Respondent Opinions with the Literature

The survey participants identified several myths associated with QEs, consistent with what has been identified in the literature.13,16,17,19,46,49 Figure 5 lists common myths associated with QEs. Many of these myths are addressed in the 9 topic areas of concern.

Figure 5.

Myths and facts related to qualifying exams identified in this analysis.

Strengths of the Study

The sample size was large, and the response rate of the survey was considered better than is reported in most online surveys.57 We obtained input not only from representatives from as many countries as possible but also from a wide array of stakeholders, and we were successful in obtaining responses from participants from approximately half of the countries where it is known that chiropractic has a presence. Another strength of the study was that we were able to identify nearly all of the chief academic officers and chief executive officers of the chiropractic training programs internationally. While not all of them responded to the survey, we did reach out to the entire population of academic administrators in charge of the programs.

Limitations of the Study

The definition of CQE used for this study was as follows:

A qualifying examination is one that a chiropractor must pass to be eligible for licensure to practice in a jurisdiction. These exams may also be known as certifying exams, licensing exams, or board exams and are typically administered during or after graduation from a chiropractic training program. These examinations are not administered by the chiropractic training program, but by an organization that is independent from chiropractic training programs. Thus, for this survey, a qualifying examination is related to initial licensure and not specialty board certification.

Respondents may have assumed that this definition was only for initial licensure requiring a CQE and not thought of them as a requirement for international graduates or doctors already in practice that desire to move to a different country. Thus, the survey may not provide accurate presentation of opinions. It does, however, seem to have opened up an important dialogue that has not previously been published.

Although we invited stakeholders from each country that had at least one practicing chiropractor, not all responded; therefore, not all countries were represented in our sample. Some invitees may have not responded because they did not think they qualified to take the survey since CQEs do not exist in their jurisdiction or they never had to take one. Regardless, we gathered perceptions of CQEs, and the opinions of these invitees may have shed additional light on the topic of CQEs and needs of stakeholders.

From some of the comments, it seems that some of those who responded were inexperienced or did not demonstrate adequate knowledge of the subject matter. For example, some people answered questions based on the misunderstanding that a jurisdiction ethics and law exam was equivalent to a CQE. While this may be a limitation of the present work, it also provides valuable information to decision makers that their stakeholders may not have a firm understanding of critical issues. If changes are considered in a jurisdiction, this may be an important hurdle to overcome.

There are some methodological shortcomings of this survey. The sample population was wide, resulting in difficulty in having a clear sample frame and assurance that there was a representative sample. Furthermore, we did not sample at random the practitioners, who make up the largest number of stakeholders within the profession. Thus, practitioner perceptions in this survey may not be of the average person in practice. The students sampled were mainly from the World Congress of Chiropractic Students, which does not have representatives from all chiropractic training programs. Thus, there may have been inadequate student input to this survey. Also, we did not conduct a study to determine the reliability or validity of the survey as it was open-ended to gather the widest possible range of responses. Finally, the survey was administered in English. Respondents from locations where English is not commonly spoken may have experienced difficulty in participating in the survey.

Suggestions for Future Research on CQEs

Since 1996, there have been periodic efforts to create and advance an education research agenda for the chiropractic profession in North America.58,59 Given that as of 2019 chiropractors are trained at 48 institutions globally and have presence in over 90 countries,60 this agenda has recently been rekindled on an international level to form research collaborations and to help determine where limited resources should be expended. CQEs receive a great deal of attention, and many resources are used including research capacity and the ability to perform useful and meaningful research. The chiropractic profession has scarce resources for conducting chiropractic education research because faculty members are mainly hired to teach, funds for education research are scarce, and research in the profession is focused on clinical effectiveness of chiropractic procedures.61–63

Currently, not much is known about the status of CQEs throughout the world. The type of examination required per international jurisdiction, the jurisdictions that require them, international reciprocity policies, and other topics related to CQEs are not well-documented and tracked in the scholarly literature available to the public. From the results of our survey, it seems that further research on CQEs is needed. Strong opinions were expressed by participants, and there appears to be a significant interest in furthering the investigation of CQEs. Where can candidates, government officials, licensing boards, and other stakeholders obtain information across jurisdictions? Which type of CQE is most common? We propose that these and other important questions be investigated.

An inventory of exam types by candidacy and by country, similar to that of Price et al,12 may be an important first step to assist in informing dialogue about portability across jurisdictions. As part of building research capacity for chiropractic education research, it is essential to determine research priorities. This study attempted to provide some guidance on whether CQEs should be a research imperative in international chiropractic education. We suggest that significant consideration be given to filling the CQE knowledge gap or risk losing the opportunity to do so to government intervention. As written by Hodson and Sullivan,27 such intercession may signal the beginning of deprofessionalization. This would be an unwelcome process for chiropractic.

A further suggestion for future research that emerged from the present study is to conduct a feasibility analysis to determine if CQEs have any association with outcomes or safety in chiropractic care. Currently, it is assumed that CQEs (of any type) ensure that candidates who pass the examinations are better or safer practitioners. This assumption requires evidence to support it. Finally, this research revealed that different CQE types should be evaluated to determine their applicability in the context of meeting minimum jurisdictional requirements and the cultures in which doctors practice.

CONCLUSION

International stakeholders in the chiropractic profession have a wide range of perceptions pertaining to CQEs. Many of the opinions are in alignment with those that society expects of learned professions. The chiropractic profession appears to be struggling with issues related to QEs similar to those of other health professions. Survey respondents provided many solutions for overcoming problems associated with CQEs. This input, in addition to literature from other healthcare fields, can assist in further development of CQEs globally. There are concerns about CQEs with regard to portability, suggesting that further education research on CQEs could be a research priority for the chiropractic profession. We hope that publishing stakeholder perceptions in an open and citable format will inform future dialogue and decisions related to the use of CQEs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David O'Bryon of the Association of Chiropractic Colleges and Sarah Villarba from the WFC for assistance in obtaining contact information for potential participants

FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No funding was received for this project. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to this work. The primary author is editor-in-chief of the journal and the other authors serve on the editorial board of the journal. Barclay Bakkum, DC, PhD (bbakkum@ico.edu) served as the refereeing editor for this manuscript. He was responsible for the management of peer review, decision, and acceptance of this manuscript. The authors were not involved in any decisions pertaining to this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGaghie WC. Professional competence evaluation. Educ Res. 1991;20(1):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr-Saunders A, Wilson P. The Professions. Oxford, UK: The Clarendon Press; 1933. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenwood E. Attributes of a profession. Soc Work. 1957;2:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millerson G. The Qualifying Associations: A Study in Professionalization. London: Routledge & Paul Humanities Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustafson JM. Professions as “callings.”. Soc Serv Rev. 1982;56(4):501–515. doi: 10.1086/644044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buijs JA. Teaching: profession or vocation. J Catholic Educ. 2005;8(3):326–345. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brante T. The professional landscape: the historical development of professions in Sweden. Professions and Professionalism. 2013;3(2):558. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen HS. Professional licensure, organizational behavior, and the public interest. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51(1):73–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulet J, van Zanten M. Ensuring high-quality patient care: the role of accreditation, licensure, specialty certification and revalidation in medicine. Med Educ. 2014;48(1):75–86. doi: 10.1111/medu.12286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svorny S. Licensing, market entry regulation. In: Bouckaert B, Geest GD, editors. Encyclopedia of Law and Economics Vol 3. The Regulation of Contracts. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Pub; 2000. pp. 296–328. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr-Saunders A. Current social statistics: the professions. Polit Q. 1931;2(4):577–581. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price T, Lynn N, Coombes L, et al. The international landscape of medical licensing examinations: a typology derived from a systematic review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(9):782–790. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Archer J, Lynn N, Coombes L, et al. The impact of large scale licensing examinations in highly developed countries: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):212. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0729-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liewer DM. Beyond the American borders: recognizing non-US education. In: Keating JC, Liewer DM, editors. Protection, Regulation and Legitimacy: FCLB and the Story of Licensing in Chiropractic Vol 2. Greeley, CO: Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards; 2012. pp. 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett C, Khangura S, Brehaut JC, et al. Reporting guidelines for survey research: an analysis of published guidance and reporting practices. PLoS Med. 2010;8(8):e1001069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bajammal S, Zaini R, Abuznadah W, et al. The need for national medical licensing examination in Saudi Arabia. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(1):74–76. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolly B. National licensing exam or no national licensing exam? That is the question. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):12–14. doi: 10.1111/medu.12941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association of Chiropractic Colleges. Find a school. 2019 http://chirocolleges.org/prospective-students/find-a-school/ Accessed May 30, 2019.

- 21.World Federation of Chiropractic. Chiropractic educational institutions. 2019 https://www.wfc.org/website/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=141&Itemid=140&lang=en. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- 22.World Congress of Chiropractic Students. Team of officials. 2019 https://www.wccsworldwide.org/team-of-officials. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- 23.World Federation of Chiropractic. List of national members of the World Federation of Chiropractic. 2019 https://www.wfc.org/ Accessed May 31, 2019.

- 24.Srivastava P, Hopwood N. A practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(1):76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwood E. Attributes of a profession. Soc Work. 1957;2(3):45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freidson E. Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge University of Chicago Press ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodson R, Sullivan TA. The Social Organization of Work 5th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swick HM. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(6):612–616. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Vleuten CP. National, European licensing examinations or none at all. Med Teach. 2009;31(3):189–191. doi: 10.1080/01421590902741171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson DB, Roberts TE. Trends in national licensing examinations in medicine. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):101–114. doi: 10.1111/medu.12810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.General Medical Council. Medical licensing assessment. 2019 https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/medical-licensing-assessment. Accessed October 6, 2019.

- 32.Martin SC. The limits of medicine: a social history of chiropractic, 1895–1930. Chiropr Hist. 1993;13(1):41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wardwell WI. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee LE. The chiropractic backbone. Harper's Weekly. 1915. pp. 285–288. September 18.

- 35.Derbyshire RC. Medical Licensure and Discipline in the United States. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimbrough ML. Jailed chiropractors: those who blazed the trail. Chiropr Hist. 1993;18(1):79–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flynn M. A legacy of professional sacrifice: a moment of silence for EJ Nosser, DC. Dynam Chiropr. 2011;29(18) http://www.dynamicchiropractic.com/mpacms/dc/article.php?id=55485. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keating JC. Birth of the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. J Chiropr Educ. 2003;17(2):89–104. [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Allied Health Professions Council of South Africa. 2019 Guidelines for Chiropractic Internship Programme. Pretoria, Republic of South Africa: The Council; 2019. https://ahpcsa.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Internship-handbook-PBCO-2019-002.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Government of Spain. Madrid: Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. Homologation of foreign titles of higher education to official Spanish university degrees of degree of master that give access to regulated profession in Spain. 2019 https://sede.educacion.gob.es/sede/login/inicio.jjsp?idConvocatoria=180. Updated September 17. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 41.Canadian Chiropractic Examining Board. Exam Content: Candidate Information. Calgary, AB: Canadian Chiropractic Examining Board; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.General Chiropractic Council. Test of competence. 2019 https://www.gcc-uk.org/ Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 43.World Federation of Chiropractic/Association of Chiropractic Colleges. WFC ACC Education Conference consensus statements. 2018 https://www.wfc.org/website/images/wfc/London_EdConference_2018/2018_Consensus_Statements.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 44.Gorsira M. The utility of (European) licensing examinations. AMEE symposium, Prague 2008. Med Teach. 2009;31:221–222. doi: 10.1080/01421590902741189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potter W. Interstate license reciprocity. Am Med Q. 1900;1(April):371. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutherland K, Leatherman S. Regulation and Quality Improvement: A Review of the Evidence. London: The Health Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norcini JJ, Boulet JR, Opalek A, Dauphinee WD. The relationship between licensing examination performance and the outcomes of care by international medical school graduates. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1157–1162. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamblyn R. Is the public being protected? Prevention of suboptimal practice through training programs and credentialing examinations. Eval Health Prof. 1994;17(2):198–221. doi: 10.1177/016327879401700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harden RM. Five myths and the case against a European or national licensing examination. Med Teach. 2009;31(3):217–220. doi: 10.1080/01421590902741155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waters TM, Lefevre FV, Budetti PP. Medical school attended as a predictor of medical malpractice claims. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(5):330–336. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.5.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuwirth L. National licensing examinations, not without dilemmas. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):15–17. doi: 10.1111/medu.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harrison CJ, Konings KD, Schuwirth LWT, Wass V, van der Vleuten CPM. Changing the culture of assessment: the dominance of the summative assessment paradigm. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0912-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christensen MG, Hyland JK, Goertz CM, Kollasch MW. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2015. Greeley, CO: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Canadian Chiropractic Examining Board. Results: following the exam. 2019 https://www2.cceb.ca/results/ Accessed October 15, 2019.

- 55.ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1176–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bloom B, Englehart MD, Furst E, Hill W, Krathwohl D. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I, Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nulty DD. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 2008;33(3):301–314. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adams AH, Gatterman M. The state of the art of research on chiropractic education. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20(3):179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mrozek JP, Till H, Taylor-Vaisey AL, Wickes D. Research in chiropractic education: an update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stochkendahl MJ, Rezai M, Torres P, et al. The chiropractic workforce: a global review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2019;27:36. doi: 10.1186/s12998-019-0255-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marchiori DM, Meeker W, Hawk C, Long CR. Research productivity of chiropractic college faculty. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ward RW. Separate and distinct: a comparison of scholarly productivity, teaching load, and compensation of chiropractic teaching faculty to other sectors of higher education. J Chiropr Educ. 2007;21(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]