ABSTRACT

Critical illness myopathy (CIM), critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP), and critical illness polyneuromyopathy (CIPNM) are the group of disorders that are commonly presented as neuromuscular weakness in intensive care unit (ICU) settings. They are responsible for prolonged ICU stay and failure to wean off from mechanical ventilation. We report a case of young female who was admitted with undiagnosed type I diabetes mellitus with diabetic ketoacidosis, severe hypokalemia, sepsis developed acute onset quadriplegia, and diaphragmatic palsy within 72 hours of ICU admission. On detailed investigation, CIPNM was diagnosed. In view of high morbidity, mortality, and poor prognosis, a guided approach to diagnose and treat in earliest possible duration might give better improvement and outcome of the illness. Despite all the odds, our patient showed good clinical improvement and finally got discharged.

How to cite this article

Mahashabde M, Chaudhary G, Kanchi G, Rohatgi S, Rao P, Patil R, et al. An Unusual Case of Critical Illness Polyneuromyopathy. Indian J Crit Care Med 2020;24(2):133–135.

Keywords: Diabetic Ketoacidosis, Intravenous immunoglobulin, Quadriplegia, Severe hypokalemia

INTRODUCTION

Critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP), critical illness myopathy (CIM), and critical illness polyneuromyopathy (CIPNM) have similar presentation that cannot be differentiated clinically. They might be seen in patients suffering from severe sepsis, hyperglycemia, metabolic syndrome such as diabetic ketoacidosis, severe electrolyte imbalances, multisystem organ failure, and patients who have been treated with neuromuscular blocking agents and large doses of corticosteroids. The symptoms may present as early as 72 hours of intensive care unit (ICU) admission.1

This case report highlights the diagnosis and management approach to the patient who develops CIPNM.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 27-year-old female was admitted with 2 days history of fever, abdomen pain, and three episodes of vomiting with severe dehydration. She was in altered sensorium, and her vitals were otherwise stable. On examination, no obvious abnormality was seen. On preliminary investigations, plasma blood sugar was high. Arterial blood gas analysis showed severe metabolic acidosis (pH: 6.95, PCO2: 15, and HCO3−: 6). Routine investigations were unremarkable except for severe hypokalemia (K+: 1.9), and urine ketone bodies were large, sugar: 3+. There was no significant past history, no significant family history, and no addictions.

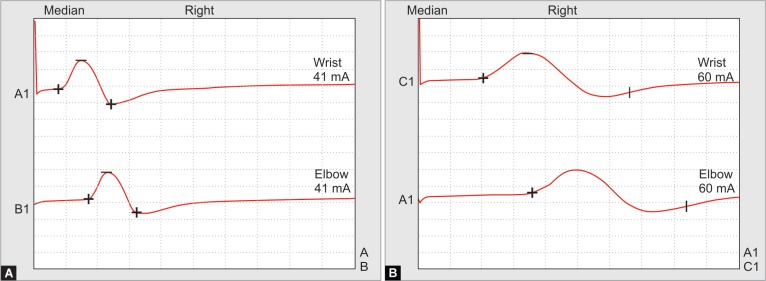

On second day, she started developing acute onset flaccid paralysis in all four limbs, symmetrical, proximal more than distal. On detailed examination, power was 1/5 in both upper limbs, 0/5 in both lower limbs, all deep tendon reflexes were diminished, and bilateral plantars were mute. Cranial nerves were intact, with no sensory loss. After 4–5 hours, she developed paradoxical breathing, not maintaining saturation in room air. We intubated her immediately and kept her on mechanical ventilation. Despite the correction of acidosis and large potassium deficits, her weakness continued to persist. On subsequent days, we were not able to wean her off from assisted ventilation. Then, we investigate further to evaluate acute onset quadriplegia. Neurophysician opinion was taken, and nerve conduction velocity (NCV) and electromyography (EMG) studies revealed primary muscle disease with axonal polyneuropathy (Fig. 1).

Figs 1A and B.

Nerve conduction velocity studies: (A) On admission; (B) 3 weeks later. Note, there is a marked decline in amplitude and increase in duration

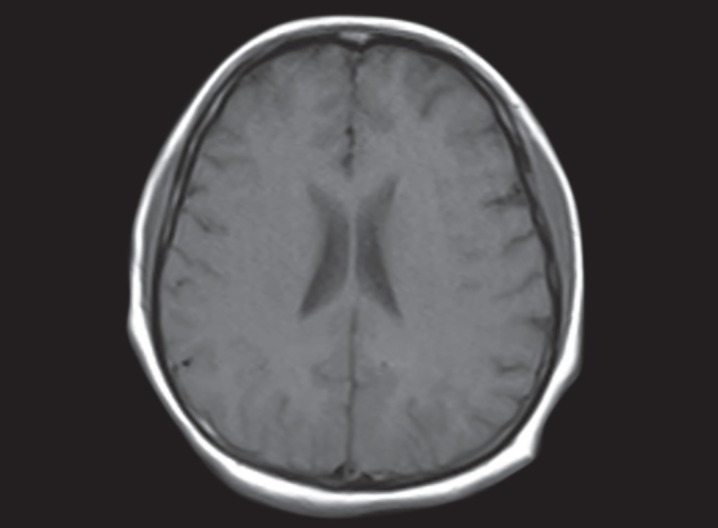

On further investigations, HBA1C was 7.5%, GAD antibodies were positive, CPK total increased to 1171 U/L, blood cultures isolated revealed coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, urine culture isolates budding yeast cells, cerebrospinal fluid examination was within normal limit, and magnetic resonance imaging brain revealed diffuse cerebral edema (Fig. 2). In view of prolonged mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy was done on day 18. Later on, she developed ventilator-associated pneumonia, and chest roentgenogram showed nonhomogeneous patches with ground glass appearance in both lower zones. High-resolution computed tomography of chest suggested bilateral infiltration of lung fields with ground glass appearance most likely pneumonia. Sputum culture was positive for Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Fig 2.

MRI of brain image showing diffuse cerebral edema

Finally, we made a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus with diabetic ketoacidosis, sepsis, severe hypokalemia, and CIPNM. Hyperglycemia was controlled, and diabetic ketoacidosis was corrected as per the protocol. Pneumonia and sepsis were treated with antibiotics according to the culture reports, and large potassium deficits were corrected with KCl, almost requiring 300 mEq./day. In the context of CIPNM, we decided to give intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) at 1 g/kg in divided doses for 5 days.2 Parenteral nutritional support, antioxidant therapy, and physiotherapy were given accordingly.

Later on, she was improved clinically, power was regained, and reflexes were present. We weaned off mechanical ventilation. Repeat electrophysiological (NCV and EMG) studies suggested the recovery phase of polyneuromyopathy, all other laboratory tests were improved, and she was discharged after 45 days of hospital stay with grade 4/5 power in all the limbs. She was advised to continue regular physiotherapy and insulin analogs.

DISCUSSION

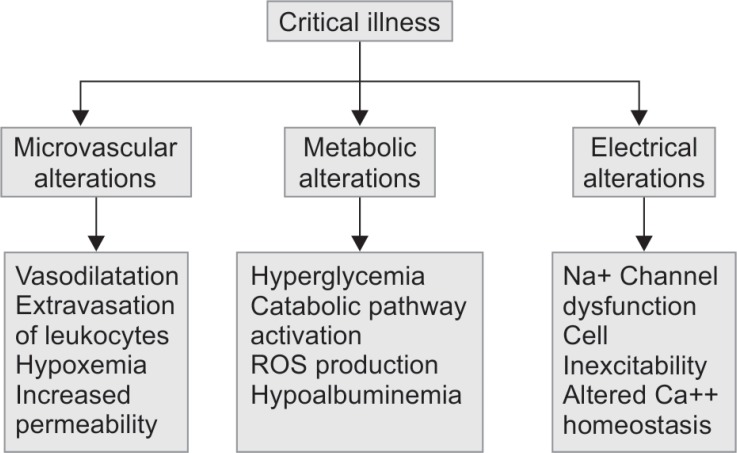

Critical illness polyneuropathy, CIM, and CIPNM are often referred to as ICU-acquired weakness (ICUAW). There are no probable etiological factors other than critical illness. The probable risk factors include severe sepsis, hyperglycemia, severe electrolyte imbalances, metabolic syndrome, increased duration of multiorgan failure, hyperosmolality, parenteral nutrition, renal replacement therapy, vasopressors, corticosteroids, neuromuscular blocking agents, and aminoglycosides1,3 (Flowchart 1).

Flowchart 1.

ICU-acquired weakness association with critical illness

Clinical suspicion is aroused when there is a failure to wean off from mechanical ventilation, despite the improvement in underlying critical illness. Muscle wasting is variable, and the sensory system may or may not be affected. Autonomic nervous system is preserved.2

The precise mechanism of developing CIPNM is unclear, but circulating factors include cytokines associated with sepsis, and multiorgan failure is thought to play a key role1 (Tables 1 to 4). It has been reported that 70% of the patients with sepsis syndrome have certain degree of neuropathy and severe respiratory muscle weakness requiring prolonged ventilation resulting in failure to wean off. There might be muscle wasting due to the loss of thick myosin filaments.4 However, the process may take place for many days and needs tracheostomy for prolonged mechanical ventilation. Some patients have residual long-term weakness with atrophy and muscle fatigue, which was not present in our patient.

Table 1.

Differential diagnoses of failure to wean from mechanical ventilation

| Motor neuron | Critical illness polyneuropathy |

| Critical illness polyneuropathy/myopathy | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | |

| Heavy metal toxicity | |

| Guillain–Barré syndrome | |

| Poliomyelitis vasculitis | |

| Neuromuscular junction | Neuromuscular blockade |

| Myasthenia gravis | |

| Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome | |

| Botulinum toxicity | |

| Muscle | Critical illness myopathy |

| Mitochondrial myopathy | |

| Muscular dystrophy (e.g., myotonic dystrophy) |

Adapted from Shepherd et al.1

Table 4.

Diagnostic criteria of critical illness polyneuromyopathy

|

Adapted from Appleton3

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

In summary, CIP, CIM, and CIPNM are commonly seen as neuromuscular weakness in patients admitted in ICU. In total, 45% of the patients who were diagnosed with ICUAW will die within their hospital admission and further 20% will die in an year after discharge.3 Once the diagnosis of ICUAW has been established, it is advisable to initiate the management as early as possible in early stages. Future management strategies should target the pro-inflammatory cytokines, free radical pathways, controlling the other risk factors that include hyperglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, and sepsis. According to the analysis in the study by Mohr et al.,5 early administration of IVIg might improve and mitigate the CIPNM. However, many trails have been going on to establish the role of IVIg in CIP/CIM.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria of critical illness polyneuropathy

|

Adapted from Bolton4

Despite high morbidity and mortality, our patient showed clinical improvement in her early phase of the hospital stay. She got discharged with minimal post illness residual weakness with almost complete recovery. In conclusion, maintaining high-level suspicion of critical illness-associated weakness in those patients admitted in ICU, early diagnosis, control of the risk factors, and the treatment given accordingly at the earliest possible duration might reduce the morbidity and mortality related to CIP/CIM.

Table 3.

Diagnostic criteria of critical illness myopathy

|

Adapted from Bolton4

SNAP, sensory nerve action potential; EMG, electromyography; MUP, motor unit potential; CMAP, compound muscle action potential

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Shepherd S, Batra A, Lerner DP. Review of critical illness myopathy and neuropathy. Neurohospitalist. 2017;7(1):41–48. doi: 10.1177/1941874416663279. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou C, Wu L, Ni F, Ji W, Wu J, Zhang H. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: a systematic review. Neural regeneration research. 2014;9(1):101–110. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.125337. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appleton R, Kinsella J. Intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Continuing education in anaesthesia, critical care and pain. 2012;12(2):62–66. doi: 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkr057. DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolton CF. Neuromuscular manifestations of critical illness. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32(2):140–163. doi: 10.1002/mus.20304. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohr M, Englisch L, Roth A, Burchardi H, Zielmann S. Effects of early treatment with immunoglobulin on critical illness polyneuropathy following multiple organ failure and gram-negative sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23(11):1144–1149. doi: 10.1007/s001340050471. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]