Abstract

Background

Lifestyle changes and cardiovascular prevention measures are a primary treatment for intermittent claudication (IC). Symptomatic treatment with vasoactive agents (Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC) for medicines from the World Health Organisation class CO4A) is controversial.

Objectives

To evaluate evidence on the efficacy and safety of oral naftidrofuryl (ATC CO4 21) versus placebo on the pain‐free walking distance (PFWD) of people with IC by using a meta‐analysis based on individual patient data (IPD).

Search methods

For this update the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Specialised Register (last searched October 2012) and CENTRAL (2012, Issue 9).

For the original review the authors handsearched the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (1984 to 1994) and checked relevant bibliographies. They contacted the registration holder of naftidrofuryl and the authors of identified trials for any unpublished data.

Selection criteria

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with low or moderate risk of bias for which the IPD were available.

Data collection and analysis

We collected data from the electronic data file or from the case report form and checked the data by a statistical quality control procedure. All randomized patients were analyzed following the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle. The geometric mean of the relative improvement in PFWD was calculated for both treatment groups in all identified studies.

The effect of the drug was assessed compared with placebo on final walking distance (WDf) using multilevel and random‐effect models and adjusting for baseline walking distance (WD0). For the responder analysis, therapeutic success was defined as an improvement of walking distance of at least 50%.

Main results

We included seven studies in the IPD (n = 1266 patients). One of these studies (n = 183) was only used in the sensitivity analysis so that the main analysis included 1083 patients. The ratio of the relative improvement in PFWD (naftidrofuryl compared with placebo) was 1.37 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.27 to 1.49, P < 0.001). The absolute difference in responder rate, or proportion successfully treated, was 22.3% (95% CI 17.1% to 27.6%). The calculated number needed to treat was 4.5 (95% CI 3.6 to 5.8).

Authors' conclusions

Oral naftidrofuryl has a statistically significant and clinically meaningful, although moderate, effect of improving walking distance in the six months after initiation of therapy for people with intermittent claudication. Access by researchers to data from RCTs that are suitable for IPD analysis should be possible through repositories of data from pharmacological trials. Regular formal appraisal of the balance of risk and benefit is needed for older pharmaceutical products.

Keywords: Humans; Administration, Oral; Intermittent Claudication; Intermittent Claudication/drug therapy; Nafronyl; Nafronyl/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Vasodilator Agents; Vasodilator Agents/therapeutic use; Walking; Walking/physiology

Plain language summary

Naftidrofuryl for intermittent claudication

Patients with narrowed arteries of the lower limbs may be hampered by pain in their calves after relatively short walks. This limits the distance they can walk, and hence their quality of life. This is a sure sign of atherosclerosis. These patients are at greater risk of cardiovascular death and should take preventive measures. The symptoms of the disease can be alleviated by smoking cessation and exercise. The question is whether specific drugs such as naftidrofuryl also reduce symptoms, more than placebo. To answer the question, we collected all published reports of randomized trials where the drug was compared with placebo. In addition, we went back to the original data of individual patients and made one big database with all data from all patients from all trials. We included seven studies with a total of 1266 patients. The improvement of pain‐free walking distance was 37% larger in the naftidrofuryl group than the improvement observed in the placebo group. In the naftidrofuryl group 55% of the patients improved by more than 50%, compared with 30% of patients on placebo. Naftidrofuryl 200 mg (taken three times a day by mouth) improved walking distance in the six months after the start of therapy.

Background

Atherosclerosis is a disease in which arteries become narrowed and hardened. Deposits of yellowish plaques (atheromas) containing cholesterol, lipoid material and lipophages are formed within the inner layer of blood vessels (the intima) and the inner media of large and medium‐sized arteries causing arterial narrowing and reduced blood flow to the lower limbs, at rest or during exercise. Atherosclerosis of the arteries of the lower extremities is commonly labeled as peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) and more recently as peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

A widely accepted international classification of PAD is Fontaine's classification (Fontaine 1954): asymptomatic patients (stage I), intermittent claudication (stages IIa and IIb), rest pain (stage III) and trophic lesions (stage IV) that include lower extremity ulcers, critical leg ischemia and ultimately gangrene of the affected extremity.

It is estimated that PAD, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, occurs in approximately 12% of the adult population in the Western world. The prevalence of PAD increases with advancing age such that almost 20% of people over the age of 70 years have the disease (Hiatt 1995). In the United Kingdom, one in five of the late middle‐aged (65 to 75 years) population have evidence of PAD on clinical examination, although only a quarter of them have symptoms (Fowkes 1991). In a German cross‐sectional study of a population of 6880 unselected patients who were aged 65 years or older the prevalence of PAD, as indicated by an ankle brachial index (ABI) < 0.9, was 19.8% and 16.8% for men and women, respectively. Patients with PAD were slightly older than patients without PAD and suffered more frequently from diabetes (36.6% compared with 22.6%, adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.8), hypertension (78.8% compared with 61.6%, OR 2.2), lipid disorders (57.2% compared with 50.7%, OR 1.3) and other co‐existing atherothrombotic diseases (any cerebrovascular event: 15.0% compared with 7.6%, OR 1.8; any cardiovascular event: 28.9% compared with 17.0%, OR 1.5) (Diehm 2004). PAOD is also prevalent in developing countries (16% prevalence in patients with a mean age of 68 years) (Li 2003).

In a recent epidemiological study in the Netherlands of 3649 participants (40 to 78 years of age) over a mean follow‐up time of 7.2 years, asymptomatic PAD was significantly associated with a cardiovascular morbidity hazard ratio (HR) of 1.6 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3 to 2.1), a total mortality HR of 1.4 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.8) and cardiovascular mortality HR of 1.5 (95% CI 1.1 to 2.1) (Hooi 2004). The natural history of patients with PAD is influenced primarily by the extent of co‐existent coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease (Coffman 1979). The majority of deaths are either sudden or secondary to myocardial infarction. The evolution from asymptomatic to symptomatic disease, the severity of symptoms in intermittent claudication and the transition to stages III and IV are influenced by the extent of the anatomical narrowing of the affected vessel(s) and any existence of a collateral circulation.

The symptoms of intermittent claudication (IC) are pain, ache, cramp or sense of fatigue in the muscles of the affected limb(s); which occurs during exercise and is relieved with rest. The occurrence of IC increases with age with a prevalence of < 1% among people younger than 49 years and as high as 24% among those aged 85 years and over; the prevalence of IC in people aged over 70 years approaches 18% (Carman 2000). Prevalence of IC is higher in males than females (two to three men for every woman) and there is no change in this ratio with increasing age (Dormandy 2000). According to the Edinburgh Artery Study the prevalence in men aged 50 to 59 years is 2.2% and rises to 7.7% for men aged 70 to 74 years (Fowkes 1991). Patients with IC have a three times higher incidence of cardiovascular mortality compared with patients without IC due to the presence of systemic atherosclerosis (Criqui 1985; Hiatt 1995). Smoking cessation plays a vital role in the management (Verhaege 1998). Regular exercise and smoking cessation can improve the symptoms of IC and may be beneficial for any associated coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease (Leng 2000). Conservative treatment should achieve improvement of functional capacity, that is an increase in walking distances, a reduction in symptoms, enhanced quality of life, inhibition of progression of atherosclerotic lesions and reduction of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality. To conform with the latest European and American regulatory guidelines (TASC II 2007), improvement of functional capacity for a patient is assessed by measuring the improvement of walking distance as the main study parameter.

The pharmacological management of IC remains to be defined precisely. To date, drugs with proven efficacy in the prevention of major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in PAD patients include antiplatelet agents (CLIPS 2007) and lipid‐lowering drugs (statins) (Burns 2003; Mohler 2003). Agents such as 'vasodilators' (naftidrofuryl, pentoxifylline, buflomedil), cilostazol and others (levocarnitine, ginkgo biloba and L‐carnitine) have been used although the availability of robust data to support their role remains lacking (Moher 2000). With regard to the so‐called vasoactive agents (the C04A class in the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification for medicines from the World Health Organisation) (WHO), controversy has reigned because evidence of clinical efficacy in improving functional capacity is not convincing. In an attempt to resolve this issue, several meta‐analyses of these drugs for intermittent claudication have been undertaken (De Backer 2000; Girolami 1999; Hood 1996; Lehert 1990; Walker 1995). Overall the conclusions of these reviews are that the effects of the C04A drugs are modest. However, since this class consists of such a heterogenous group of products, in terms of their mechanism of action, it is possible that there are differences between them in clinical efficacy. Hence, new reviews should focus on placebo‐controlled trials of the clinical efficacy of single drugs. In the most recent systematic review dedicated specifically to the class of vasoactive drugs, naftidrofuryl was singled out as a potential candidate for further research (De Backer 2000). The most recent narrative review, specifically on the use of naftidrofuryl in the treatment of intermittent claudication (Goldsmith 2005), also supports a clinical relevant effect of naftidrofuryl in patients with intermittent claudication.

All the previous reviews of class C04A drugs which engaged in meta‐analyses were based on published aggregate data, where the average results of several studies are pooled into one meta‐analytic result. Although this is the dominant method, and a valuable approach for synthesizing efficacy data on medicinal products, it may have several drawbacks. In meta‐analyses based on published aggregate data there may be insufficient information available on the variability of the results. Confidence intervals may be provided for baseline and final values but not for the mean change in the primary measure. It is possible to provide approximate estimates in such a situation by calculating the standard deviation (SD) of a difference from the SD of the initial and final visits but these estimates are inaccurate. In older papers the change in walking distance was recorded as an arithmetic mean. In more recent papers it is the geometric mean of the ratio between the walking distance at baseline and the walking distance at final assessment that is recorded. The difference between these two statistics could be important, depending on the skewness of the distribution of the results.

To overcome the limitations of a meta‐analysis based on published aggregate data methodology we undertook a meta‐analysis based on individual patient data (IPD). This allowed us to overcome differences in populations in the different studies over the last 20 years due to changes in study selection guidelines issued by regulatory authorities. In addition, it was possible to correct the usual approach of older studies, to report on a per‐protocol (PP) population, by performing an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis of all randomized participants as insisted upon in recent guidelines for randomized controlled trials. The inherent drawback of an IPD meta‐analysis is the considerable work involved in finding and reorganizing raw data. In this respect carrying out an IPD analysis for the C04A drugs combined would be a large and probably unfeasible task. Hence, we focused on naftidrofuryl as this is one of the only drugs in the class where a minimum of studies of acceptable methodological quality are available (De Backer 2000). In addition, preliminary contacts with the manufacturer (Merck laboratories) and with the study investigators led us to believe that it would be possible to get access to the individual patient data for most of the trials.

Naftidrofuryl is a vasoactive drug that has been marketed since 1968 for the treatment of PAD. The putative mechanisms of action are selective blockade of vascular and platelet 5‐hydroxytryptamine (5‐HT2) receptors and stimulation of the intracellular tricarboxylic acid cycle with increased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production (Lehert 1990). Although not a conventional vasodilator, naftidrofuryl is included in the ATC therapeutic class of peripheral vasodilators (C04A). Successive small trials with this drug have shown moderate but significant effects. However, the clinical relevance of a classical meta‐analysis based on the literature was questioned because of the heterogeneity among the trials (De Backer 2000). Naftidrofuryl is an old drug with an acceptable safety record that has been widely used. The recommended oral dosage for the indication of intermittent claudication has remained unchanged at 200 mg three times per day. Its patent has expired and there is a wide choice of generics in most countries. Consequently daily treatment costs are rather low (around one euro per day).

Objectives

To determine the efficacy of oral naftidrofuryl (600 mg daily) versus placebo in improving functional capacity in patients with intermittent claudication (IC) by conducting a meta‐analysis of individual patient data (IPD).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized placebo‐controlled clinical trials of oral naftidrofuryl.

Types of participants

Patients with intermittent claudication (Fontaine stage II) (Fontaine 1954).

Types of interventions

Oral naftidrofuryl (200 mg three times a day) compared with placebo.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome

Pain‐free walking distance (PFWD), defined as the distance walked (in meters) during a standardized exercise test before the onset of calf pain.

Secondary outcomes

Maximum walking distance (MWD), defined as the maximum distance walked (in meters) during a standardized exercise test.

Safety issues, defined as adverse effects directly or possibly related to the use of naftidrofuryl.

Search methods for identification of studies

There was no restriction on language.

Electronic searches

For this update the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (last searched October 2012) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2012, Issue 9, part of The Cochrane Library, www.thecochranelibrary.com. See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL. The Specialised Register is maintained by the TSC and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and through handsearching relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals and conference proceedings which have been searched, as well as the search strategies used are described in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group module in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Searching other resources

For the original review the authors handsearched the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (1984 to 1994), checked relevant bibliographies and contacted the registration holder of naftidrofuryl and the authors of identified trials for any unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection

From the results of the above search strategy, TDB and RVS selected the relevant RCTs based on the abstracts of the identified articles or, if necessary, the original publication.

Quality assessment

Assessment of the quality of trials based on the published reports

We assessed the methodological quality of the selected publications of trials and unpublished reports, for both the quality of the trial and the reporting, using the approach of a previous systematic review of vasodilators (De Backer 2000). The original report of all selected trials was transformed into a structured abstract (prepared by TDB and RVS).

We assessed internal validity using the validated scale developed by Jadad et al (Jadad 1996) which includes appropriateness of randomization, double blinding and a description of dropouts and withdrawals by intervention group.

As in the previous systematic review based on the literature (De Backer 2000b), we set three additional quality criteria: sufficient reporting of variability of results, minimum sample size of the study (30 participants) and minimum duration of the study (three months), in accordance with generally accepted methodological standards (Cameron 1988).

Two authors (TDB and RVS) assessed for quality the full publications and the structured abstracts of the clinical trials not identified in the previous systematic review (De Backer 2000b). A third author (LVB) arbitrated if there was disagreement. We only used data for the final analysis from unpublished reports or publications of trials with an acceptable quality. If trials were eliminated by quality criteria we performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the stability of the results.

Additional elements used to appraise the quality of the studies were:

obsolete dosage (< 600 mg daily);

a target population not corresponding to PAD stage II;

study conducted before 1980 (quality control considered too poor);

cross‐over design (because of important carry‐over effects).

Assessment of the quality of trials based on the individual patient data (IPD)

We checked the availability of IPD data for the selected trials by sending a request to the registration holder for unconditional delivery of blinded data.

Reasons to exclude studies were:

too many missing variables or an important overall rate of missing data (> 10% after case report form (CRF) consultation);

the following variables missing in > 5% of patients: randomization treatment code, walking distance (WD) at baseline, WD at final stage of analysis;

the following variables missing in > 20% of patients: age, gender, end‐of‐file status;

doubt about reliability of the computer data compared with CRF data;

questionable data (published results different from database). In our checks for data reliability we were able to isolate, in our database of all randomized patients, only the patients for which data were used in each of the historical publications (some data were per protocol and some by an intention to treat, see Methods section). Hence we were able to check whether the aggregate data from these patients, as presented in our IPD database, fully matched the results of the patients used in the historical publication; only a very small margin of error was allowed (less than 1% deviation).

This quality procedure resulted in the exclusion and inclusion of studies through a consensus discussion process involving all the authors of the original protocol. Studies were excluded because of serious quality flaws or unavailability of IPD data, or both. The included studies were divided into a group of main studies (acceptable quality and IPD available) and a second group of supportive studies (not compliant with all of the above quality criteria but IPD data available). Data from the main and supportive studies constituted the IPD database.

Data collection for the IPD meta‐analysis

Search for the original patient data

After identification of the relevant trials, the data collection in the IPD meta‐analysis constituted a long and complex process involving the different research teams of the included trials, and possibly the manufacturing company, with a request to access either the original data on printed CRFs or the databases into which the raw data were entered. Computerized data entry files are available in various mainframe formats whereas for other older studies only the CRFs are likely to have been retained. All available data were entered in a common pooled database.

Data integrity checks

For data collected from secondary databases, we performed a statistical quality control procedure against the original CRFs by using a military control process, 105D (Mil‐STD 105D), based on random sampling of cases to be checked. At database completion we sent the registration holder (keeper of the CRFs) a list of values randomly distributed among patients and variables, with patient and variable identification but without the value, with the aim of filling in each value at the CRF level. The returned values were compared with our database and a failure rate was calculated. A random subset of 150 values were sent, with a failure rate cut‐off of k = 0. The following key variables were retained: study, centre, patient number; gender; walking distance at baseline (WD0), last carried forward claudication distance (WDf); weight (kg) and age (years).

Checks for publication bias

We intended to assess possible publication bias through funnel plots and the method of Egger that is based on visual representation of the correlation between effect size and sample size (Egger 1997).

Final decision to proceed with the IPD analysis

Two authors (TDB and PL) supervised this procedure. As soon as the information on quality and availability of the individual patient data from the selected trials was finalized, a decision was made as to the continuation of this research. This decision was made by the authors, with consensus.

Data extraction

Construction of the pooled database

Any randomized patient for whom a CRF or database record was available was entered in the pooled database (using the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle or full analysis set (FAS) procedure). In particular, data from patients lost to follow up and excluded in per‐protocol analyses were retrieved. In addition, in some older studies it was possible that analysts retrospectively excluded patients from the final analyses based on post‐hoc criteria although fully completed CRFs or database records of these patients (excluded from the analysis but randomized) were available. The data on these patients were also retrieved.

Main variables

We considered the following variables to be important. If these variables were not documented in the secondary databases we then re‐examined the CRFs.

(1) Dates of visits, centre number and patient number.

(2) Termination status (or end‐of‐trial status), including detailed definition of the reason for early termination: 0 = normal termination; 1 = lost to follow up with no apparent reason; 2 = adverse drug‐related reaction; 3 = intercurrent disease, not drug related; 4 = interruption due to lack of compliance; 5 = refusal to participate any longer; 6 = interruption due to protocol violation; 7 = death or serious cardiovascular event; 8 = interruption for surgery; 9 = discontinuation due to local deterioration or progression to PAD stage III.

(3) Follow‐up variables. The ability to evaluate were described as: patient was excluded based on post‐hoc criteria; patient not evaluated on a per‐protocol analysis; patient included in the original analysis (ITT, restricted ITT or per protocol).

(4) Demographic variables: gender, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), illness duration, month of randomization, brachial systolic blood pressure and ankle systolic blood pressure at baseline.

(5) Various risk factors: history of smoking, hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, cerebrovascular or cardiovascular events.

(6) Walking distance measurement: pain‐free walking distance (PFWD) measured at selection, baseline, day 90, day 180 and last observation carried forward; maximum walking distance (MWD), if available.

Statistical analysis

Patient selection

The main analysis was based on intention to treat, where all the randomized patients were considered. Two other selections were used for support, essentially for checking consistency with historical results: per‐protocol patients (study completers and fully compliant to the regimen) and restricted intention‐to‐treat (rIT) patients (randomized patients with at least one post‐baseline value).

Analysis organization

During the data collection a statistical analysis plan (SAP) was agreed by the team. This analysis conformed with the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) regulatory guidelines for PAD (CPMP Working Party; EMEA). All the analyses were carried out with SAS (version 9.1). After the data integrity check the database was locked. The treatment codes were unknown at the time of the data collection and only provided at the end of the analysis process.

Missing data imputation

For missing main endpoint data, the worst case value was attributed to patients who interrupted the trial early for a reason related to PAD (progression to stage III and IV, aggravation, hospitalization or surgery). For all the other randomized patients who stopped for a reason unrelated to PAD, the last observation carried forward (LOCF) was used as occurs in most PAD trials. However, for sensitivity assessment purposes we carried out an alternative analysis by using summary statistics (mean of intermediate, non‐missing post‐baseline values) when at least two intermediate observations were available. For covariables, missing data were checked for at random and imputed by a systematic full information maximum likelihood (FIML) technique (Anderson 1957).

Main endpoint

Our primary measurement was the pain‐free walking distance (PFWD) measured at baseline and on final assessment, in both naftidrofuryl and placebo treatment groups. We used as the main endpoint the relative improvement RI = WDf/WD0, where WDf and WD0 designated final and baseline PFWD values respectively. The geometric mean with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was used for normality purposes. Treatment effect was measured by the ratio RInaftidrofuryl /RIplacebo. In addition, we calculated the traditional Cohen's effect size (Cohen 1988).

In our main analysis, the PFWD at the end of the study was taken as the final (WDf) if available, and the LOCF was used if the WDf was not available. Four studies had their final WD at six months, one at 12 months (Boccalon 2001) and two at three months (Kriessman 1988; Maass 1984). The LOCF is an approximation justified by: a) its recommendation in PAD guidelines; b) the short expected follow‐up time (six months in general); and c) for a majority of patients the final values were available. In addition, we did summary statistics analysis where we included all intermediate values of the PFWD (often measured at one, three and six months).

Main meta‐analysis statistical test based on the geometric means of WDf and WD0

We conducted the analysis in two independent ways: a one‐stage approach in which the database was considered as one data set and a two‐stage approach in which the aggregated results of each study were pooled and then analyzed with traditional peripheral artery disease meta‐analysis (MA‐PAD) techniques.

For the ratio RInaftidrofuryl / RIplacebo and for effect size we used, in the one‐stage approach, the multilevel (patient and trial) general linear mixed model (GLMM) (Higgins 2001) by considering random treatment effects, fixed‐study effects and adjusting for WD0. We conducted a supportive two‐stage analysis by calculating aggregate RI estimates for each treatment group within each study followed by a conventional random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986) that is more familiar to clinicians. Our postulated model is based on WD0 covariates, study and treatment factors. Exploratory stepwise research was carried out on all the available predictors (risk factors in particular) to detect the possible existence of additional determinant predictors.

Threshold for significance

The alpha level of error for a significant treatment effect was set at 0.01. We also calculated 95% CIs.

Responder analysis

We also analyzed the data as binary variables. A patient was considered as a responder to therapy when the PFWD improved by at least 50%, from baseline. We estimated the difference in success rates between naftidrofuryl and placebo, the derived number needed to treat (NNT), the relative benefit and the odds ratio (OR). These statistics were calculated with a similar mixed model as above for the one‐stage approach, adapted for binary data (Turner 2000). For the two‐step approach, again we used the random‐effects model of DerSimonian and Laird (DerSimonian 1986).

Secondary outcome measure

For analysis of the maximal walking distance (MWD) data in the trials for which data were available we used the same technique as for PFWD .

Sensitivity analysis

We tested the stability of the results by:

using all the available trials;

excluding or including trials considered as debatable;

comparing the results on the full intention‐to‐treat (ITT) sample with the other a priori selected subgroups, namely restricted intention to treat (rIT) and per‐protocol;

comparing LOCF and use of summary statistics allocation of missing data.

Safety

1. From the publications of the randomized controlled trials

A short description was given of reports on safety issues in the publications.

2. From the IPD

From the IPD, the safety of oral naftidrofuryl was assessed mainly from the mean of the reported adverse events in the naftidrofuryl‐treated patients compared with the mean in the placebo group. We extracted data from the source documents, clinical trials or the publications.

We carried out safety analysis from RCTs by estimating the proportion of participants experiencing at least one:

adverse event (AE) at a moderate level;

serious cardiovascular AE (including death);

serious non‐cardiovascular AE;

gastric AE.

For each of these events we calculated the relative risk in the naftidrofuryl and placebo groups, calculating the difference for each study and using the DerSimonian and Laird model.

3. From all trials and from post‐marketing surveillance (PMS) and periodic safety update (PSU) reports

From all the studies of naftidrofuryl (22,187 patients), two safety studies were carried out and the upper limit 95% CI of the serious adverse‐event incidence was calculated. From the PMS and PSU reports provided by the local authorities, the number of treatment years, during the period 1995 to 1998 and 1998 to 2000, and the number of declared serious adverse events, labeled and suspected drug‐related reports were calculated.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

See Appendix 1.

No additional studies were identified for inclusion or exclusion in this update.

We were able to retrieve from the international library system the original publication of all the trials. Subsequent confirmatory searches, based on this set of 11 trials and 20 reviews, using the "related articles" algorithm in PubMED and a search in the Science Citation Index did not reveal additional references; nor did a request for information to the company and to the authors of the retrieved studies. Our request for IPD data to the authors and to the company resulted in the information, provided by the company, that IPD data for nine of the 11 studies were available.

Of the 11 trials, three were published before 1984, six between 1984 to 2000 and two after 2000. Three trials used obsolete doses of naftidrofuryl, either 100 mg four times daily or 100 mg three times daily, and eight used either 200 mg three times daily or 300 two times daily. One study (Karnik 1988) was a cross‐over study. IPD were available from nine studies and covariates from seven studies.

Characteristics of excluded studies

(see also table 'Characteristics of excluded studies' and Table 1; Table 2; Table 3)

1. Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Placebo n=626 | Naftidrofuryl n=640 | All n= 1266 | ||||

| mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | p | |

| Age (y) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 57.06 | 8.67 | 57.04 | 8.32 | 57.05 | 8.46 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 59.34 | 8.85 | 59.43 | 8.68 | 59.39 | 8.73 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 61.04 | 8.51 | 61.97 | 8.72 | 61.48 | 8.61 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 61.87 | 8.29 | 60.37 | 8.3 | 61.12 | 8.3 | |

| Moody 1994 | 63.31 | 8.93 | 63.01 | 7.9 | 63.16 | 8.43 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 65.62 | 8.9 | 66.07 | 9.33 | 65.86 | 9.11 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 66.43 | 11.43 | 67.43 | 10.07 | 66.93 | 10.76 | |

| All studies | 62.36 | 9.58 | 62.45 | 9.39 | 62.41 | 9.48 | |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||||

| Adhoute 1986 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.12 | ||||

| Kriessman 1988 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.18 | ||||

| Adhoute 1990 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.09 | ||||

| Moody 1994 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.26 | ||||

| Boccalon 2001 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.25 | ||||

| Kieffer 2001 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||||

| All studies | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.18 | ||||

| Height (m) | 0.012 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 1.71 | 0.08 | 1.72 | 0.06 | 1.72 | 0.07 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 1.7 | 0.05 | 1.68 | 0.05 | 1.69 | 0.05 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 1.7 | 0.07 | 1.7 | 0.08 | 1.7 | 0.07 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 1.69 | 0.04 | 1.7 | 0.05 | 1.69 | 0.05 | |

| Moody 1994 | 1.7 | 0.08 | 1.68 | 0.09 | 1.69 | 0.08 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 1.68 | 0.06 | 1.69 | 0.07 | 1.69 | 0.07 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 1.68 | 0.08 | 1.67 | 0.08 | 1.67 | 0.08 | |

| All studies | 1.69 | 0.07 | 1.69 | 0.07 | 1.69 | 0.07 | |

| Weight (kg) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 76.35 | 9.35 | 75.51 | 10.23 | 75.92 | 9.79 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 70.94 | 8.88 | 68 | 8.68 | 69.31 | 8.86 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 74.34 | 11.13 | 74.03 | 11.87 | 74.19 | 11.46 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 69.24 | 8.47 | 69.97 | 9.33 | 69.6 | 8.9 | |

| Moody 1994 | 70.55 | 10.05 | 70.03 | 11.25 | 70.03 | 10.62 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 72.3 | 10.94 | 72.03 | 12.99 | 72.15 | 12.04 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 69.32 | 12.34 | 72.34 | 15.57 | 70.83 | 14.09 | |

| All | 71.82 | 10.62 | 71.75 | 11.94 | 71.79 | 11.3 | |

| BMI(kg/m2) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 26.01 | 2.4 | 25.36 | 2.97 | 25.67 | 2.72 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 24.61 | 2.17 | 24.09 | 2.21 | 24.32 | 2.2 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 25.66 | 3.2 | 25.63 | 3.17 | 25.65 | 3.18 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 24.19 | 2.15 | 24.22 | 2.52 | 24.2 | 2.34 | |

| Moody 1994 | 24.35 | 3.07 | 24.68 | 3.14 | 24.51 | 3.1 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 24.14 | 7.05 | 22.78 | 8.26 | 23.41 | 7.73 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 24.53 | 3.41 | 25.81 | 4.24 | 25.17 | 3.89 | |

| All | 24.79 | 3.75 | 24.67 | 4.42 | 24.73 | 4.1 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 152.13 | 20.9 | 154.42 | 22.91 | 153.32 | 21.93 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 145.62 | 14.99 | 148.7 | 12.89 | 147.33 | 13.9 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 151.3 | 19.34 | 151.93 | 19.23 | 151.6 | 19.25 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 149.98 | 23.1 | 145.55 | 19.04 | 147.76 | 21.22 | |

| Moody 1994 | 162.12 | 28.05 | 158.69 | 26.47 | 160.47 | 27.29 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 144.19 | 17.64 | 143.3 | 21.83 | 143.72 | 19.91 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 137.4 | 12.34 | 136.73 | 14 | 137.07 | 13.16 | |

| All | 149.14 | 21.42 | 148.24 | 20.94 | 148.69 | 21.17 | |

| ABI | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 0.61 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.14 | 0.61 | 0.14 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 0.66 | 0.1 | 0.66 | 0.12 | 0.66 | 0.11 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.58 | 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.12 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.18 | |

| Moody 1994 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.69 | 0.16 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 0.73 | 0.08 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 0.74 | 0.14 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 0.65 | 0.26 | 0.63 | 0.23 | 0.64 | 0.24 | |

| All | 0.65 | 0.17 | 0.65 | 0.17 | 0.65 | 0.17 | |

| Duration of PAD (y) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 2.77 | 3.51 | 2.74 | 3.05 | 2.75 | 3.27 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 2.65 | 3.19 | 3.85 | 5.68 | 3.32 | 4.46 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 2.47 | 2.52 | 2.15 | 2.54 | 2.32 | 2.53 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 2.89 | 3.55 | 3.41 | 4 | 3.15 | 3.78 | |

| Moody 1994 | 3.48 | 3.17 | 3.8 | 3.82 | 3.63 | 3.49 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 3.65 | 0.61 | 3.69 | 0.64 | 3.67 | 0.62 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 5.38 | 5.15 | 5 | 4.36 | 5.19 | 4.77 | |

| All | 3.35 | 3.47 | 3.51 | 3.76 | 3.43 | 3.62 |

2. Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Placebo n=626 | Naftidrofuryl n=640 | All n=1266 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Obesity (n, %) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 17 | 25 | 18 | 24.32 | 35 | 24.65 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 12 | 18.46 | 11 | 13.58 | 23 | 15.75 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 40 | 32.26 | 39 | 35.14 | 79 | 33.62 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 12 | 13.19 | 12 | 13.19 | 24 | 13.19 | |

| Moody 1994 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 23.86 | 40 | 21.86 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 18 | 22.22 | 18 | 19.78 | 36 | 20.93 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 21 | 21.43 | 36 | 36.73 | 57 | 29.08 | |

| All studies | 139 | 22.35 | 155 | 24.45 | 294 | 23.41 | |

| Smoking (n, %) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 38 | 55.88 | 49 | 66.22 | 87 | 61.27 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 42 | 64.62 | 46 | 56.79 | 88 | 60.27 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 44 | 35.48 | 47 | 42.34 | 91 | 38.72 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 49 | 53.85 | 50 | 54.95 | 99 | 54.4 | |

| Moody 1994 | 41 | 43.16 | 50 | 56.82 | 91 | 49.73 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 41 | 50.62 | 51 | 56.04 | 92 | 53.49 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 29 | 29.59 | 27 | 27.55 | 56 | 28.57 | |

| All studies | 284 | 45.66 | 320 | 50.47 | 604 | 48.09 | |

| AHT (n,%) | 0.103 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 25 | 36.76 | 29 | 39.19 | 54 | 38.03 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 14 | 21.54 | 26 | 32.1 | 40 | 27.4 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 39 | 31.45 | 41 | 36.94 | 80 | 34.04 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 25 | 27.47 | 22 | 24.18 | 47 | 25.82 | |

| Moody 1994 | 33 | 34.74 | 26 | 29.55 | 59 | 32.24 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 22 | 27.16 | 36 | 39.56 | 58 | 33.72 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 36 | 36.73 | 37 | 37.76 | 73 | 37.24 | |

| All | 194 | 31.19 | 217 | 34.23 | 411 | 32.72 | |

| Angina (n, %) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 3 | 4.41 | 7 | 9.46 | 10 | 7.04 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 11 | 16.92 | 12 | 14.81 | 23 | 15.75 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 11 | 8.87 | 13 | 11.71 | 24 | 10.21 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 8 | 8.79 | 13 | 14.29 | 21 | 11.54 | |

| Moody 1994 | 14 | 14.74 | 17 | 19.32 | 31 | 16.94 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 9 | 10.59 | 17 | 17.53 | 26 | 14.29 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| All | 56 | 10.61 | 79 | 14.58 | 135 | 12.62 | |

| Diabetes (n, %) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 7 | 10.29 | 15 | 20.27 | 22 | 15.49 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 10 | 15.38 | 10 | 12.35 | 20 | 13.7 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 6 | 4.84 | 7 | 6.31 | 13 | 5.53 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 11 | 12.09 | 15 | 16.48 | 26 | 14.29 | |

| Moody 1994 | 12 | 12.63 | 9 | 10.23 | 21 | 11.48 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 5 | 6.17 | 17 | 19.68 | 22 | 12.79 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 23 | 23.47 | 22 | 22.45 | 45 | 22.96 | |

| All | 74 | 11.9 | 95 | 14.98 | 169 | 13.46 | |

| Hyperlipaemia (n, %) | 0.015 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 27 | 39.71 | 33 | 44.59 | 60 | 42.25 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 2 | 33.85 | 23 | 28.4 | 45 | 30.82 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 55 | 44.35 | 53 | 47.75 | 108 | 45.96 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 30 | 32.97 | 29 | 31.87 | 59 | 32.42 | |

| Moody 1994 | 36 | 37.89 | 31 | 35.23 | 67 | 36.61 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 38 | 46.91 | 39 | 42.86 | 77 | 44.77 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 36 | 36.73 | 34 | 34.69 | 70 | 35.71 | |

| All | 244 | 39.23 | 242 | 38.17 | 486 | 38.69 | |

| Sedentarism (n, %) | 0.05 | ||||||

| Maass 1984 | 23 | 33.82 | 32 | 43.24 | 55 | 38.73 | |

| Adhoute 1986 | 35 | 53.85 | 35 | 43.21 | 70 | 47.95 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | 58 | 46.77 | 60 | 54.05 | 118 | 50.21 | |

| Adhoute 1990 | 43 | 47.25 | 39 | 42.86 | 82 | 45.05 | |

| Moody 1994 | 40 | 42.11 | 36 | 40.91 | 76 | 41.53 | |

| Boccalon 2001 | 29 | 35.8 | 31 | 34.07 | 60 | 34.88 | |

| Kieffer 2001 | 39 | 39.8 | 47 | 47.96 | 86 | 43.88 | |

| All | 267 | 42.93 | 280 | 44.16 | 547 | 43.55 |

3. Dates of accrual and of publication of the studies.

| Studies | Date of accrual | Date of publication |

| EXCLUDED | ||

| Ruckley | 1975‐1976 | 1978 |

| Pohle | 1976‐1978 | 1979 |

| Clyne | 1977‐1979 | 1980 |

| Karnik | 1985‐1987 | 1987 |

| INCLUDED | ||

| Maass | 1980‐1983 | 1984 |

| Adhoute | 1982‐1984 | 1986 |

| Kriessmann | 1983‐1985 | 1988 |

| Adhoute | 1985‐1989 | 1990 |

| Moody | 1987‐1989 | 1994 |

| Kieffer | 1996‐1999 | 2001 |

| Boccalon | 1996‐1999 | 2001 |

Ruckley 1978 This was a study of small but acceptable size (50 patients) that was of short duration (three months) with an obsolete dosage of 100 mg three times daily and with a flawed internal validity. Individual patient data were partially available but not the data on the covariables. An effect size of 1.25 was calculated.

Pohle 1979 This was a study of small but acceptable size (51 patients), a short study (12 weeks) with an obsolete dosage of 100 mg once daily and with an acceptable internal validity. Individual patient data were partially available but not the data on the covariables. An effect size of 0.63 was calculated.

Clyne 1980 This was a study of acceptable size (128 patients of whom 30 dropped out), duration (six months) and internal validity with an obsolete dosage of 100 mg once daily. There were no IPD and no covariables data available. An effect size of 0.45 was calculated.

Karnik 1988 This was a small trial (40 patients) using the usual dosage of 600 mg daily but of short duration in a cross‐over design (2 x 8 weeks). There were no IPD data available and no data on covariables. An effect size of 1.11 was calculated.

Characteristics of included studies (see also table 'Characteristics of included studies')

Maass 1984 This was a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled multicenter (seven) study performed in hospital and ambulatory care settings in Germany. One hundred and thirty‐three patients with PAOD stage II over at least six months and aged between 40 and 70 years were included. Twenty‐nine patients dropped out. After a four‐week wash‐out period the patients were randomly divided into two groups: 54 in the treatment group (51 men and three women) and 50 in the placebo group (46 men and four women) with a mean age of 57 years + 8.2 years and 57 years + 8.6 years, respectively. The patients were assigned to 12 weeks of oral treatment with either 200 mg naftidrofuryl three times daily or placebo. Measurements were taken in the wash‐out period and at one, two and three months. Pain‐free walking distance and MWD were measured on a treadmill (5 km/h at 10% elevation). Ankle brachial index was measured by Doppler and using a cuff. IPD sample size: 142.

Adhoute 1986 This was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized multicenter clinical trial performed in hospital and ambulatory care in France. One hundred and eighty‐six patients of both sexes, aged between 40 and 70 years with Fontaine stage II PAOD were selected out of 222 recruited patients following a wash‐out period of one month. Thirty‐six patients were excluded because they did not correspond to the protocol of the trial; 32 patients dropped out of the study because of a variation of PFWD > 20%. After the four‐week run‐in period patients were divided randomly in two groups: 64 in the treatment group (55 men and nine women) and 54 in the placebo group (50 men and four women). During the four‐week run‐in period patients received placebo tablets three times daily. Afterwards, patients received naftidrofuryl 200 mg three times daily or an identical placebo tablet for six months. Measurements were taken at days ‐30, 0, 90 and 180. Pain‐free walking distance was measured on a treadmill (3 km/h at 10% elevation). Ankle brachial index was measured by Doppler. Clinical compliance and tolerance were measured at each visit. IPD sample size: 146.

Kriessman 1988 This was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized multicenter trial performed in hospital and ambulatory care settings in Germany. Two hundred and seventy‐four patients aged between 40 and 70 years with Fontaine stage II PAOD were recruited. Fifty‐four patients were excluded from the study because they did not correspond to the study protocol; 27 stopped the therapy; 39 were not included in the study because their center did not reach the minimal level of recruitment and 18 were lost to follow up. One hundred and thirty‐six patients were included in the trial. After a four‐week run‐in period the patients were divided randomly into two groups: 71 in the treatment group (57 men and 14 women) with a mean age of 63+8 years and 65 in the placebo group (52 men and 13 women) with a mean age of 60 + 8 years. After a two‐week run‐in period where all patients received placebo, the patients received 12 weeks of oral treatment with either 600 mg naftidrofuryl (300 mg two times daily) or placebo. Measurements were taken at days ‐14, 0, 40 and 82. Pain‐free walking distance was measured on a treadmill (5 km/h at 7% elevation). Ankle brachial index was measured by Doppler. IPD sample size: 235.

Adhoute 1990 This was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized multicenter study performed in hospital and ambulatory care in France. One hundred and eighty‐three patients of both sexes, aged between 40 and 70 years with Fontaine stage II PAOD were recruited. Seventy‐one patients were excluded as they did not correspond with the protocol; 15 were lost to follow up and three discontinued treatment. After the four‐week run‐in period, 94 patients were divided randomly in two groups: 52 in the treatment group (48 men and four women) and 42 in the placebo group (36 men and six women). During the four‐week run‐in period all patients received placebo. During the trial the patients received either 316.5 mg naftidrofuryl or identical placebo tablets two times daily for six months. Measurements were taken at days ‐30, 0, 90 and 180. Pain‐free walking distance and MWD were measured on a treadmill (3 km/h at 10% elevation). Ankle brachial index was measured by Doppler. IPD sample size: 182.

Moody 1994 This was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized parallel group trial performed in a hospital setting. One hundred and eighty‐eight patients with intermittent claudication and aged between 40 and 80 years old were recruited from two centers with inclusion based on self‐estimated walking distance. Five patients did not enter the study and three were lost to follow up, leaving 180 patients. In the course of the study five patients in the active group and 10 patients in the control group withdrew from the study. After a four‐week run in period, the active treatment group (n = 85) received 316.5 mg naftidrofuryl fumarate two times daily for 24 weeks while the placebo group (n = 95) received placebo two times daily. Measurements were taken at weeks 0, 8, 16, and 24. Pain‐free walking distance and MWD were measured on a treadmill (slope of 100 at 3 km/h). Ankle brachial index was also measured. IPD sample size: 183. Boccalon 2001 This was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled randomized trial performed in an ambulatory care setting in France. The outpatients selected were of either sex, aged 40 to 80 years with chronic stable intermittent claudication (< 500 m) and an ankle brachial index (ABI) between 0.60 and 0.90. The patients received naftidrofuryl 200 mg three times daily or placebo for 12 months. They were seen by their general practitioner every three months: M0, M3, M6, M9 and M12; when ABI, tolerance and treatment effects were evaluated. Four visits were to the angiologists' office: M0, M3, M6 and M12; where walking distance was evaluated. The measurement of walking distance was undertaken using a device called the PADHOC (peripheral arterial disease holter control) worn by the patient. This was a registering box attached to a belt and linked to two ultrasonic patches and a command box held in the hand. The principle of the device is the measurement of walking distance and the speed profile in an ambulatory person. One hundred and eighty‐two patients were randomized and 168 entered the intention‐to‐treat analysis. The two groups were well matched for demographic variables, risk factors and history of vascular disease. IPD sample size: 182.

Kieffer 2001 This was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled randomized study performed in outpatients recruited from five hospitals in Paris and assessed in one single centre. Outpatients of either sex (80% male, mean age 66.9 years) aged between 35 and 85 years with moderately severe chronic, stable intermittent claudication of at least six months duration and who had been clinically stable during the last three months, with the diagnosis of PAOD confirmed by arteriography or duplex scan, were recruited. All patients had already undergone a course of exercise therapy. Only patients whose PFWD and MWD on the treadmill were between 100 and 300 meters were included in the study. It was also a requirement that the walking distance of the patients did not vary by more than 25% between recruitment and randomization. Of the 221 selected patients, 25 did not satisfy the entry criteria. One hundred and ninety‐six patients were randomized following a four‐week placebo run‐in period to: naftidrofuryl (n = 98) or placebo (n = 98) for six months. The patients were followed up for a further six months after discontinuation of treatment. The two groups were well matched for demographic variables (with the exception of BMI, which was significantly higher in the naftidrofuryl group), risk factors and history of vascular disease. Fifteen patients did not supply any further information after baseline, nine in the naftidrofuryl group and six in the placebo group, leaving 181 who entered the intention‐to‐treat analysis. A further 29 patients (13 naftidrofuryl, 16 placebo) did not complete the study according to the protocol, which left 152 patients available for the on‐treatment analysis. Following the end of the six months treatment phase, a further 18 patients dropped out before the final treadmill test at eight months, leaving 134 patients eligible for the final treadmill test at eight months. The primary outcome measures were PFWD and MWD measured on the treadmill using a constant workload and a specific device which recorded both time and gait (results of the latter measurements are not included in this review). The secondary measures of efficacy were the ABI. These measures were performed at all assessment points before, during and at the end of the active treatment phase and at eight months. Clinical tolerance was assessed at all timepoints. Biological tolerance, in particular measurement of liver and renal function, was also evaluated. IPD sample size: 196.

Risk of bias in included studies

(see also Table 4)

4. Quality evaluation of the excluded and included trials.

| Study | Sample size | Duration | Variability | Internal Validity | IPD available | Covariables availabl | Grade |

| EXCLUDED studies | |||||||

| Ruckley 1978 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | incomplete | no | C |

| Pohle 1979 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | incomplete | no | C |

| Clyne 1980 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | no | no | C |

| Karnik 1988 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | no | no | C |

| INCLUDED studies | |||||||

| Maass 1984 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | yes | yes | B |

| Adhoute 1986 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | yes | yes | B |

| Kriessman 1988 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | yes | yes | B |

| Adhoute 1990 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | yes | yes | B |

| Moody 1994 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | yes | yes | B |

| Boccalon 2001 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | yes | yes | B |

| Kieffer 2001 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | yes | yes | B |

Assessment of methodological quality

Excluded studies

We graded the trials of Ruckley 1978 and Karnik 1988 as C (high risk of bias) because of problems of internal validity. This evaluation was in line with our previous review (De Backer 2000). Two trials (Clyne 1980; Pohle 1979) were excluded, in contrast with evaluation of published results in our previous review. Pohle 1979 was excluded because of: incomplete IPD data, bad quality, no availability of covariables and the use of an obsolete drug dosage. The effect size was calculated as 0.63. Clyne 1980 was excluded because IPD were only available for 60% of the patients, covariates were not available and an obsolete dosage was used. The effect size was 0.45.

In conclusion, four trials (Clyne 1980; Karnik 1988; Pohle 1979; Ruckley 1978) were excluded and the reasons for exclusion are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Included studies

We included seven trials, which we graded B (moderate risk of bias). All trials were conducted with a common dosage of 600 mg oral naftidrofuryl daily and were from the period between 1984 and 2001. Individual patient data and covariables were available for all studies (see table 'Characteristics of included studies' and Table 3).

We did not exclude the trial by Moody et al (Moody 1994) as we did in our previous review, because no data on variability were given in the published report. In this review IPD data were available and hence variability could be directly assessed.

Checks for publication bias

The sample size of the included studies ranged from 142 to 235 so no study could be considered as small or large; in statistical terms this is interpreted by the square root of the sample size (11.9 to 15.3). This range is very small, thus funnel plots based on detection of a positive monotonic relationship between relative efficacy and sample size were of limited relevance here.

We did, however, apply a range of techniques to find unpublished trials: searches of trials registers, contacts with other researchers and contact with the manufacturing company. None of these approaches revealed evidence of unpublished studies. In addition, we meticulously reviewed the reference lists of relevant articles to find 'hidden' studies (a process called snowballing). In our literature search, undertaken over 10 years, we did not find any evidence of unpublished studies for naftidrofuryl. This is in contrast with documented publication bias for other products in this field where we did find references in the bibliography to studies which, judging by the abstract, were negative but never published (De Backer 2000).

Data extraction for the IPD meta‐analysis

Access to the original patient data

At our request, the company agreed to provide the IPD data unconditionally. Data were stored in CRFs and in individual databases per study, each with a different computer format. The data were extracted from these study databases and transferred to one common database with a common structure.

Data integrity checks

For data collected from secondary databases, we performed a check against the original CRFs using a military control process 105D (Mil‐STD 105D). We checked a random subset of 150 values (study, centre, patient number; gender; WD0, WDf; weight (kg) and age (years). We were able to retrieve all data except for the weight values in the Kriessman study and, instead of 150 values, 146 values were available. After comparison of the computer output with the results manually reported by Merck the number of mistakes was 0/146. This test provided some basic evidence of data reliability of at least 99%.

A total of 7.8% of secondary covariables were missing. After analysis these missing data were considered as missing at random and allocated by a full information maximum likelihood procedure (FIML).

Comparison with published results

For each trial and each treatment group we calculated the mean WD0, WDf and difference (WDf‐WD0); this was the calculation in all published results. We were able to determine which patients in our pooled database contributed to the results as published, from a selection by study design of the published study (per protocol or rIT). The analyses were originally carried out on a restricted intention‐to‐treat basis (Boccalon 2001; Kieffer 2001; Moody 1994) and per protocol for all other studies. This enabled us to check whether the mean values documented in the primary analyses matched with our own results in the pooled IPD database and this check was successful (margin of error less than 1%).

Final decision to proceed with the IPD analysis

Given the limited number of excluded trials, the successful data integrity check and match with the historical data as published and the size of the available pooled database, the authors decided to proceed with the IPD analysis.

There was some debate about two studies (Boccalon 2001; Moody 1994). The latter study (Moody 1994) that had been excluded in the previous review was now included because IPD were available. However, we considered the study to be of rather poor quality with regard to internal validity and more than 70% of the patients had a baseline PFWD of < 100 m. Therefore, this study was classified as a supportive study; it was not included in the main analyses and only analyzed in the sensitivity analysis.

Boccalon 2001 was considered to be of good quality, complying with the guidelines and internal validity criteria. The variability of the results was not well reported but this could be corrected by the IPD data. The trialists used the non‐conventional PADHOC method for measuring walking distance, claimed to represent a higher but more physiological WD0 and WDf. The inclusion of this trial had two consequences. Firstly, it was decided that a sensitivity analysis without the results of this study would be conducted. Secondly, in the main analysis where the Boccalon study was included, results could not be expressed in absolute terms (for example the number of meters gained in WDf ‐ WD0) and were expressed as relative improvement (WDf/WD0).

Effects of interventions

Sample description

(see Additional tables Table 1; Table 2)

One thousand, two hundred and sixty‐six patients (ITT) constituted the whole database of this IPD meta‐analysis (626 placebo, 640 naftidrofuryl); seven studies contributed to the database: Adhoute 1986 (146); Adhoute 1990 (182); Boccalon 2001 (182); Kieffer 2001 (196); Kriessman 1988 (235); Maass 1984 (142); and Moody 1994 (183).

The sample was characterized by a mean age of 62.8 years, 18% women, mean body mass index (BMI) 24.78 ± 4.29 kg/m2, mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) 148.86 ± 21.95 mm Hg, mean ankle brachial index (ABI) 0.65 ± 0.17, mean duration of illness 3.45 ± 3.44 years, 23.4% obese patients, 48% currently smoking, 32.7% hypertensives, 12.6% with angina pectoris, 13.4% type 2 diabetes patients, 38.7% of patients with hyperlipidemia and 43.6% sedentary patients (not performing any physical exercise). As expected, there were important differences among the studies for all these variables (inter‐study heterogeneity) but the two treatment groups matched well for each study as well as for the full set.

Final assessment data were available (per protocol) for 896 patients (71%). For 305 patients (24%) at least one assessment after baseline (not final assessment) was available (rIT). For 65 patients (5%) a randomization code was available but no outcome assessment data (ITT).

Details on the reasons for termination of data are given for 370 patients in Additional Table 5 and Table 6.

5. Termination Status by Study and by Treatment.

| Study | Treatment | Normal | Lost to FU | Adverse Drug R | Intercurr dis |

| Maass 1984 | Placebo | 59 | 3 | 1 | |

| Naftidrofuryl | 69 | 3 | |||

| Adhoute 1986 | Placebo | 46 | 3 | ||

| Naftidrofuryl | 58 | 7 | 4 | 1 | |

| Kriessman 1988 | Placebo | 102 | 6 | 3 | |

| Naftidrofuryl | 97 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Adhoute 1990 | Placebo | 60 | 9 | ||

| Naftidrofuryl | 75 | 7 | |||

| Moody 1994 | Placebo | 82 | 1 | 1 | |

| Naftidrofuryl | 80 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Boccalon 2001 | Placebo | 55 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Naftidrofuryl | 67 | 8 | 6 | ||

| Kieffer 2001 | Placebo | 69 | 10 | 3 | |

| Naftidrofuryl | 66 | 9 | 1 |

6. Termination status by Study and by Treatment.

| Study | Treatment | Non Compliance | Refusal further part | Protocol violation | Dead+CVE | Surgery | Local deterioration |

| Maass 1984 | Placebo | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Naftidrofuryl | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Adhoute1986 | Placebo | 1 | 3 | 10 | 2 | ||

| Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 7 | 2 | ||||

| Kriessman 1988 | Placebo | 2 | 6 | 5 | |||

| Naftidrofuryl | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Adhoute 1990 | Placebo | 1 | 2 | 16 | 3 | ||

| Naftidrofuryl | 1 | 7 | 1 | ||||

| Moody 1994 | Placebo | 1 | 4 | 6 | |||

| Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Boccalon 2001 | Placebo | 9 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |

| Naftidrofuryl | 9 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Kieffer 2001 | Placebo | 1 | 13 | 3 | |||

| Naftidrofuryl | 22 | 2 |

Outcome evaluation

Goodness of fit of the proposed model

We carried out a stepwise linear regression analysis of the WDf as a dependent variable, potential predictors being WD0, risk factors and other covariables (age, sex, duration of illness, obesity, diabetes, sedentary life, hypertension, angina pectoris, smoking, hyperlipemia). The analysis revealed that WD0 was the key predictor (R2 = 0.479), accounting for almost all the variability of the other baseline predictors.

Main analysis

Details of the relative improvement of PFWD by study and by treatment are given in Table 7.

7. Relative Improvement of Pain Free Walking Distance (PFWD) by study and by treatment.

| WDf/WD0 | Placebo | CI | Naftidrofuryl | CI |

| Maass 1984 | 1.167 | 0.944‐1.465 | 1.302 | 1.062‐1.656 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 1.316 | 1 ‐1.739 | 1.6 | 1.036‐2.069 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 1.293 | 0.933‐2.04 | 1.486 | 1.217‐2.111 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 1.176 | 1‐1.429 | 1.5 | 1.167‐2 |

| Moody 1994 | 1.16 | 0.838‐1.5 | 1.316 | 1‐1.841 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 1 | 0.713‐1.665 | 1.639 | 1.042‐2.688 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 1.135 | 0.946‐1.419 | 1.801 | 1.414‐2.248 |

| All | 1.176 | 0.926‐1.645 | 1.53 | 1.124‐2.149 |

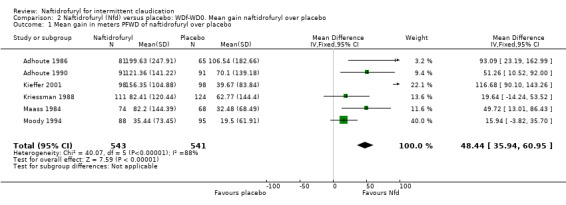

The main analysis was carried out on a full ITT basis for all participants of six trials (excluding Moody 1994). As explained above, Moody 1994 was not considered in the main analysis, leaving a total of 1083 patients (531 placebo, 552 naftidrofuryl).

Based on ITT samples of six trials, the main analysis based on RI = WDf/WD0 and secondary analyses on responder rate were carried out in a one‐stage multilevel linear mixed model. The treatment effect estimate was RInaftidrofuryl / RIplacebo 1.37 (95% CI 1.27 to 1.49, P < .001). The unadjusted geometric mean RIs were 1.21 and 1.60 for placebo and naftidrofuryl, respectively.

The treatment effect estimates of the two meta‐analytic techniques (one‐stage and two‐stage conventional random approach) were very similar, with somewhat wider estimates of CI in the two‐stage approach (Table 8).

8. Comparison of efficacy between placebo and naftidrofuryl for 1‐step and 2‐steps.

| Analysis | 1‐Step Estimates | 2‐Step Estimates |

| Ratio Relative Improvement PFWD: WDf/WD0 Naf/Plac | 1.37; 95% CI 1.27 to 1.49 | 1.38; 95%;CI 1.24 to1.56 |

| Effect Size ES WDf/WD0 | 0.69; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.84 | 0.57; 95%;CI 0.31 to 0.82 |

| Ratio Relative Improvement MWD: MWDf/MWD0 Naf/Plac | 1.40; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.63 | 1.38; 95%;CI 1.18 to 1.61 |

| Absolute difference succes proportion | 22.3; 95% CI 17.1 to 27.6 | 24.8; 95%;CI 12.2 to 37.4 |

| NNT | 4.48; 95% CI 3.62 to 5.85 | 4.03; 95%;CI 2.51 to 8.19 |

| Relative Benefit | 1.75; 95% CI 1.50 to 2.03 | 1.84; 95%;CI 1.36 to 2.45 |

| Odds Ratio | 2.65; 95% CI 2.10 to 3.37 | 2.90; 95%;CI 1.70 to 4.94 |

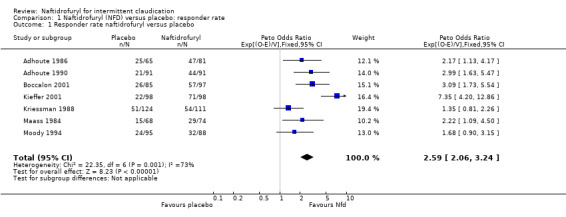

Our responder analysis identified 30.2% and 54.7% responders for placebo and naftidrofuryl, respectively. The absolute difference in responder rate, or success proportion, was 22.3% (95% CI 17.1 to 27.6). The number needed to treat was 4.48 (95% CI 3.62 to 5.85). Forest plots based on the Peto OR are shown with responder rates for naftidrofuryl over placebo. Additional tables (Table 9; Table 10; Table 11) show the responder analysis.

9. Responder rate (>50%). Response by study by treatment.

| Study ID | Rp | Np | Rn | Nn |

| Maass 1984 | 15 | 68 | 29 | 74 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 25 | 65 | 47 | 81 |

| Kriessmann 1988 | 51 | 124 | 54 | 111 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 21 | 91 | 44 | 91 |

| Moody 1994 | 24 | 95 | 32 | 88 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 26 | 85 | 57 | 97 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 22 | 98 | 71 | 98 |

| All | 184 | 626 | 334 | 640 |

10. Responder analysis. Difference in success proportion Rn‐Rp.

| Study | Responder rate Rp | Responder rate Rn | Difference Rn‐Rp | CI 1 | CI2 |

| Maass 1984 | 22.06 | 39.19 | 17.13 | ‐13.56 | 47.82 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 38.46 | 58.02 | 19.56 | ‐11.68 | 50.81 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 41.13 | 48.65 | 7.52 | ‐22.18 | 37.22 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 23.08 | 48.35 | 25.27 | ‐4.74 | 55.29 |

| Moody 1994 | 25.26 | 36.36 | 11.1 | ‐18.87 | 41.07 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 30.59 | 58.76 | 28.17 | ‐2.04 | 58.39 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 22.45 | 72.45 | 50 | 20.55 | 79.45 |

| All | 22.84 | 11.44 | 34.24 |

11. Responder analysis. Odds Ratio (Rn/1‐Rn)/(Rp/1‐Rp).

| Study | Rp/1‐Rp | Rn/1‐Rn | (Rn/1‐Rn)/(Rp/1‐Rp) | CI 1 | CI 2 |

| Maass 1984 | 28.3 | 64.44 | 227.7 | 97.75 | 357.66 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 62.5 | 138.24 | 221.18 | 95.21 | 347.14 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 69.86 | 94.74 | 135.6 | 16.91 | 254.29 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 30 | 93.62 | 312.06 | 187.59 | 436.52 |

| Moody 1994 | 33.8 | 57.14 | 169.05 | 44.74 | 293.35 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 44.07 | 142.5 | 323.37 | 200.13 | 446.6 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 28.95 | 262.96 | 908.42 | 783.36 | 1033.47 |

| All | 268.19 | 167.58 | 429.19 |

Heterogeneity

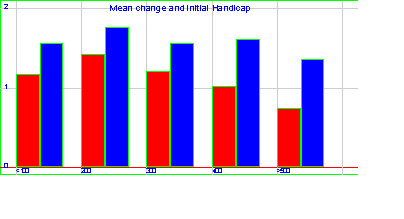

In the two‐stage approach, the test for heterogeneity using Peto OR was significant (P < 0.001). Hence we studied the influence of baseline handicap on treatment effect (presented in Additional Figure 1). The baseline handicap did not significantly affect the relative improvement (mixed model, P > 0.05), which remained constant for the naftidrofuryl group and the placebo group except for a larger walking distance at baseline where the placebo effect seemed to decrease. The heterogeneity was taken into account in the one‐stage approach by using multilevel techniques and in the two‐stage approach by using the random‐effects model of DerSimonian and Laird (DerSimonian 1986).

1.

Mean change and baseline handicap

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out various alternative analyses (Table 12); in particular, adding the excluded study (Moody 1994) resulted in a treatment effect estimate with a relative improvement ratio RInaftidrofuryl / RIplacebo of 1.37 (95% CI 1.28 to 1.48, P <0.001, n = 1266). Eliminating Boccalon 2001 (based on physiological walking distance), the ratio was 1.31 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.39, P < 0.001). In comparing our full intention‐to‐treat analysis with the per‐protocol sample (n = 726), we found a higher value of 1.42 (95% CI 1.22 to 1.65). The LOCF versus summary statistics showed a ratio of 1.37 (95% CI 1.28 to 1.48) versus 1.52 (95% CI 1.44 to 1.62).

12. Summary of efficacy in the different analyses. One stage analysis.

| Analysis | Sample size | Treatment estimate | RInaf/RIplac | ||

| n | Treatment | LogWD0 | Study | ||

| Main Analysis (All‐Moody) | 1083 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.115 | 1.37; CI 95% 1.27 to 1.48 |

| All studies | 1266 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | 1.37; CI 95% 1.28 to 1.48 |

| All studies ‐Boccalon | 1084 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.052 | 1.31; CI 95% 1.24 to 1.39 |

| All studies ‐Moody‐Boccalon | 901 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 1.32; CI 95% 1.24 to 1.40 |

| Per Protocol | 726 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | 1.42; CI 95% 1.22 to 1.65 |

Analysis of the secondary outcome

The maximum walking distance (MWD) was determined with the same selection and statistical techniques. This endpoint was not measured in all studies and for some studies only on a subset of patients (n = 968, six studies). The relative improvement was 1.40 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.63) and the responder rate absolute risk difference was 23.9% (95% CI 15.7 to 32.1).

Details of the relative improvement of MWD (WDf/WD0) by study and by treatment are given in Table 13.

13. Relative Improvement of Maximal Walking Distance (MWD) by study and by treatment.

| WDf/WD0 | Placebo | CI | Naftidrofuryl | CI |

| Maass 1984 | 1.25 | 1.09‐1.43 | 1.41 | 1.28‐1.54 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 1.44 | 1.27‐1.63 | 1.74 | 1.59‐1.89 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 1.18 | 1.05‐1.32 | 1.60 | 1.48‐1.73 |

| Moody 1994 | 1.13 | 1.02‐1.25 | 1.21 | 1.08‐1.35 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 1.01 | 0.86‐1.119 | 1.74 | 1.48‐2.05 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 1.14 | 1.07‐1.21 | 1.83 | 1.72‐1.94 |

| All | 1.17 | 1.12‐1.23 | 1.57 | 1.50‐1.64 |

Safety analysis

1. As reported in the publications of the randomized controlled trials

1. Maass 1984 reported as serious adverse events (SAE): in the naftidrofuryl group one requiring vascular surgery and one stroke during the wash‐out period; in the placebo group one embolectomy, one ischialgia (pain in the hip) and one ulcus cruris (foot ulcer). Reported non‐serious adverse events were: in the naftidrofuryl group one with nausea plus gastric pain, one urticaria, one dry mouth, one nausea and one loss of body weight; in the placebo group one with urticaria, one nausea and gastric pain. No relevant variations in biological data were detected.

2. Adhoute 1986 reported seven adverse events in the naftidrofuryl group and three in the placebo group. These were mainly gastrointestinal problems. In one patient receiving placebo the gastrointestinal problems were severe enough to discontinue treatment. In both groups laboratory data remained unchanged during the study period.

3. Kriessman 1988 reported serious adverse events for which treatment was discontinued: in the naftidrofuryl group four experienced deterioration of PAOD, two gastric pain and one death with reason unknown; in the placebo group five had deterioration of PAOD, two gastric pain, one fever and one pulmonary disorder. Other adverse events were: in the naftidrofuryl group 14 with gastric disorders, one dry mouth, one skin erythema (reddening of the skin), one articular stiffness, one pressure in the eyes and two with no details given; in the placebo group three experienced gastric disorders, one memory disorder, one sweating, one sleep disturbance, two headaches and three with no details given.

4. Adhoute 1990 reported 27 patients (30%) in the naftidrofuryl group with at least one adverse event. Of these, 20 reported at least one important adverse event and eight reported at least one non‐serious adverse event. In the placebo group 31 (34%) patients reported at least one adverse event of which 10 were important, five patients reported at least one non‐serious adverse event.

5. Moody 1994 stated that in the naftidrofuryl group there was one with angina pectoris and one suspected myocardial infarction. In the placebo group one participant experienced acute ischemia followed by bypass surgery, one myocardial infarction and one vascular occlusion followed by angioplasty. In the naftidrofuryl group a higher incidence of minor gastrointestinal symptoms was recorded.

6. Boccalon 2001 found that in the naftidrofuryl group 28 patients (29%) had at least one adverse event versus 15 (17%) in the placebo group during the double‐blind treatment period. In the naftidrofuryl group 17 patients (29%) had at least one serious adverse event versus eight (17%) in the placebo group, although this was not statistically significant. This difference is due to hospitalization for various pathologies (eight in the naftidrofuryl group versus three in the placebo group), among other factors. Five deaths occurred during the study (three in the naftidrofuryl group versus two in the placebo group). In the naftidrofuryl group eight non‐serious adverse events were reported, mainly gastro‐intestinal disorders (four); compared with five in the placebo group.

7. Kieffer 2001 reported that in the naftidrofuryl group 18 patients (18%) experienced one or more adverse events compared with 21 patients (21%) in the placebo group. In the naftidrofuryl group 11%, 12% in the placebo group, reported at least one serious adverse event. No serious adverse event was directly related to the study during the double‐blind treatment phase. One patient died in the naftidrofuryl group due to lung cancer. In the naftidrofuryl group nine non‐serious adverse events were reported versus 12 in the placebo group. The non‐serious adverse event for which a possible relationship with naftidrofuryl existed was one case of digestive disorder.

In summary, there were no significant differences for serious adverse events between naftidrofuryl and placebo. For the non‐serious adverse events there was a significantly higher incidence of gastro‐intestinal disorders.

2. From the IPD of randomized controlled trials

Table 14 shows the number of patients experiencing at least one adverse event at a moderate level for naftidrofuryl and for placebo. Table 15 shows the number of patients experiencing at least one gastric adverse event for naftidrofuryl and for placebo. Table 16 shows the number of patients experiencing at least one serious non‐cardiovascular adverse event for naftidrofuryl and for placebo. Table 17 shows the number of patients experiencing at least one serious cardiovascular event for naftidrofuryl and for placebo. Overall, there was no significant difference between both groups for moderately severe adverse events; the proportion of non‐cardiovascular adverse events was not significantly different and the proportion of cardiovascular adverse events was slightly higher in the placebo group. Only the proportion of gastric disorders was higher in the naftidrofuryl with a risk difference of 2.85% (95% CI 0.78 to 4.91%) compared with placebo. Table 5 and Table 6 show the reasons for prematurely leaving the study, including adverse drug reactions and cardiovascular events.

14. Safety calculation of Placebo versus Naftidrofuryl: Moderate AE.

| Study | Placebo | N Placebo | Naftidrofuryl | N Naftidrofuryl |

| Maass 1984 | 0 | 68 | 0 | 74 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 19 | 65 | 17 | 81 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 20 | 124 | 27 | 111 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 0 | 91 | 0 | 91 |

| Moody 1994 | 0 | 95 | 0 | 88 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 15 | 85 | 28 | 97 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 21 | 98 | 18 | 98 |

| All | 75 | 626 | 90 | 640 |

15. Safety calculation of Placebo versus Naftidrofuryl: Gastric AE.

| Study | Placebo | N Placebo | Naftidrofuryl | N Naftidrofuryl |

| Maass 1984 | 2 | 68 | 4 | 74 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 3 | 65 | 7 | 81 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 8 | 124 | 18 | 111 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 10 | 91 | 18 | 91 |

| Moody 1994 | 5 | 95 | 7 | 88 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 3 | 85 | 4 | 97 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 2 | 98 | 1 | 98 |

| All | 33 | 626 | 59 | 640 |

16. Safety calculation of Placebo versus Naftidrofuryl: Non CV AE.

| Study | Placebo | N Placebo | Naftidrofuryl | N Naftidrofuryl |

| Maass 1984 | 1 | 68 | 0 | 74 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 0 | 65 | 5 | 81 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 3 | 124 | 3 | 111 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 0 | 91 | 0 | 91 |

| Moody 1994 | 1 | 95 | 1 | 88 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 3 | 85 | 6 | 97 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 98 |

| All | 8 | 626 | 15 | 640 |

17. Safety calculation Placebo versus naftidrofuryl: CV AE.

| Study | Placebo | N Placebo | Naftidrofuryl | N Naftidrofuryl |

| Maass 1984 | 5 | 68 | 1 | 74 |

| Adhoute 1986 | 15 | 65 | 11 | 81 |

| Kriessman 1988 | 11 | 124 | 5 | 111 |

| Adhoute 1990 | 21 | 91 | 9 | 91 |

| Moody 1994 | 10 | 95 | 3 | 88 |

| Boccalon 2001 | 10 | 85 | 20 | 97 |

| Kieffer 2001 | 13 | 98 | 12 | 98 |

| All | 85 | 626 | 61 | 640 |

3. From periodic safety update reports (PSUR)

From all the studies of naftidrofuryl (n = 22,187 patients) two safety studies were carried out. The upper limit of serious adverse‐event incidence was 1.35 x 10‐4 (1/10,000).

During the period from 1995 to1998 there were 1,224,908 treatment years with 19 labeled adverse events. During the period 1998 to 2000 there were 2,823,546 treatment years with 18 labeled adverse events. These events were mainly gastric disorders. The observed incidence rate was 0.305 x 10‐5 and the upper 95% CI was 0.89 x 10‐5, so that the rate of drug‐related serious adverse events was likely to be less than 10‐5 (1/100,000).