Abstract

The study aimed to analyse the effectiveness of two variants of 8-week strength training (hypertrophy, strength) with different modes of resistance. Healthy male subjects (n=75) were allocated to five groups of equal size: hypertrophy training with a variable cam (Hyp-Cam), hypertrophy training with disc plates (Hyp-Disc), maximal strength training with a variable cam (Str-Cam), maximal strength training with disc plates (Str-Disc), and a control group (CG). The Hyp-Cam and Str-Cam groups trained with a machine where the load was adjusted to the strength capabilities of the elbow flexors. The Hyp-Disc and Str-Disc groups trained on a separate machine in which a load was applied with disc plates. The CG did not train. All groups were assessed for changes and differences in one-repetition (1RM) lifts, isokinetic muscle torque, arm circumference and arm skinfold thickness, and plasma creatine kinase (CK) activity. Within the 8-week training period the 1RM increased (p<.001) in all groups by over 20%, without significant between-group differences. Muscle torque increased significantly (p<.001) only in the Hyp-Cam group (by 13.7%). Arm circumference at rest increased by 1.7 cm (p<.001) and 1.1 cm (p<.001) in the Hyp-Cam and Hyp-Disc groups, respectively, but not in the Str-Cam (0.3 cm; p>.05) or Str-Disc (0.2 cm; p>.05) group. Skinfold thickness of the biceps and triceps decreased more within the 8-week period in Str-Cam (by 1.1 and 2.1 cm; p<.001 and p<.001 respectively) and Str-Disc (0.7 and 1.5 cm; p<.001 and p<.01 respectively) than in Hyp-Cam (by 0.4 and 1.8 cm; p>.05 and p<.01 respectively) and Hyp-Disc groups (by 0.2 and 1.4 cm; p>.05 and p<.05 respectively). CK activity was significantly (p<.05) elevated in each training group except Hyp-Cam (p>.05). The 8-week hypertrophy training with a variable cam results in greater peak muscle torque improvement than in the other examined protocols, with an insignificant increase in training-induced muscle damage indices.

Keywords: Variable cam, Creatine kinase, Muscle torque, Elbow flexors, Isokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Resistance training is widely used as an adjunct or primary training method to increase muscle size and strength in most sport disciplines. Typically, to increase muscle size (or induce hypertrophy), moderately heavy loads with moderate repetitions (8–12 range) and rest periods between sets depending on the kind of trained muscles and type of exercise, usually 1–3 min, are used [1–4]. By contrast, to improve muscle strength, maximal or near maximal loads with fewer repetitions (1–6 range) are often prescribed using primarily compound exercises, but with rest periods allowing for appropriate recovery between sets and exercises [5–7]. These schemes can be applied using either free weights and/or machines.

Resistance-training machines are recognized as safer to use and easy to learn, and support the performance of some exercises that may be difficult using free weights [3]. Machines help stabilize the body and limit movement about specific joints, whilst engaging specific muscle groups during exercise [3]. Different training machines are designed to provide resistance in a manner that activates muscle contractions in a different way. Hydraulic antagonistic resistance machines allow only a concentric muscle action in a push or pull system. This system is different from free weight training, where concentric elbow flexion (biceps curl) is followed by eccentric biceps work, while the elbow extends [8]. Isokinetic machines provide variable resistance, such that force is developed at a constant velocity, but this kind of muscle work is not natural compared to free weight exercises [9].

Most functional resistance-training machines are designed to provide resistance by a variable cam between the rotating lever arm, against which the user applies torque, and the load to be lifted. This is based on the assumption that in the human musculoskeletal system, the value of the strength depends on the muscle force as well as on its arm [10–11]. By adjusting the radius of the cam, it is possible to control the external load. Biomechanical analyses of human motion as a function of the angle have demonstrated that the muscles at the joints develop their maximum torque only within a specific range of motion. The range of changes in muscle strength potential is different for different groups of muscles and joints, and the differences between the maximum and minimum values can reach 90% [12–17]. It may be assumed that the most effective workout will occur using a machine where the load value, as a function of the angle, is best tailored to human strength abilities. That means that it is necessary to use a cam with a variable radius. The use of a specially adjusted variable-radius cam makes the external load suit the muscle abilities as a function of the angle [18].

Resistance training can produce significant muscle damage, as a possible stimulus for adaptation [19–20]. The amount and severity of muscle damage depend on multiple factors including the type of contraction, duration, and intensity of muscle work and sports level [21]. Collectively, these stimuli damage the muscle by causing an overstretching of the sarcomere to such an extent that it becomes disrupted, resulting in elevated levels of creatine kinase (CK) and other biomarkers [22].

Published studies were based mainly on single exercises in which have found that cams shapes hadn’t match to muscle torque with respect to the entire range of joint motion [18,23–25], which may then interfere with training-induced muscle size and strength adaptations over time. To address this problem, a recent study designed a variable cam based on optimal muscle torque and electromyographic activity [26]. Subsequently, a training study was performed that compared the effects of two training protocols, one using a variable cam and another the disc plate approach, on strength and power output. Both outcomes were found to be more pronounced with optimal design of the variable cam, which was, essentially, constructed to match the strength capabilities of elbow flexors [26].

The present study aimed to advance this work by investigating a hypertrophy and maximal strength training protocol, each performed using a machine with an optimized variable cam and disc plate method. Changes in muscle size and muscle torque were assessed at pre-, mid- and post-training time points. Each training variant was also evaluated for changes in plasma creatine kinase (CK) activity, as an indirect measure of muscle damage. We hypothesized that applying the variable cam in the elbow flexor training machine would have a greater influence on increasing the muscles force and hypertrophy than training without a specially designed variable cam.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The study encompassed 75 men, all physical education students (aged 21 ± 1 years) who declared that they had not engaged in regular sports training for at least six months before the study commenced. The number of participants was based on previous experiments and sample size calculations using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4, Germany). A priori sample size was calculated for a group by time interaction comparison (F test, ANOVA for repeated measures, within-between interaction) with the following specifications: alpha level = 0.05, power = 0.80, f effect size = 0.25. The estimated number of subjects was 45. To fulfil these requirements and accommodate dropouts (~10–20%) in training studies, a total of 75 men were recruited. During this experiment, the men only participated in exercise activities that were part of the physical education curriculum. All participants were informed about the study procedures, benefits, risks and their obligations, before signing informed consent. They were also informed that they could cease participation at any point, without any consequences. The study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee, approval no. SKE 001-106-01/2010.

Study protocols

The participants were intentionally divided into five groups of equal size (Table 1): hypertrophy training with a variable cam (Hyp-Cam), hypertrophy training with disc plates (Hyp-Disc), maximal strength training with a variable cam (Str-Cam), maximal strength training with disc plates (Str-Disc), and a control group (CG). The Hyp-Cam and Hyp-Disc groups were prescribed a muscle-size building protocol, involving four sets of 10 repetitions max (10RM) and 3-minute rest periods between the sets. The Str-Cam and Str-Disc groups were prescribed a typical maximal strength training regime, involving eight sets with maximal and submaximal loads (1st set: four repetitions x 75% RM; 2nd set: two repetitions x 85% RM; 3rd–8th set: 1RM), with 2-minute rest periods between sets. Training was performed on a Master-Sport machine (Poland) for elbow flexors on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays for eight consecutive weeks. The participants were required to overcome external resistance during flexion (concentric muscle work) and extension (eccentric muscle work) at both elbow joints at the same time. The range of motion of the forearm was between 180 degrees (fully extended elbow joint) and about 30 degrees of flexion. Before each training workout, the participants individually performed a warm-up for the relevant muscle groups.

TABLE 1.

Groups and training methods.

| Group | N | Body mass* [kg] | Height* [cm] | Training machine with: | Training method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyp-Cam | 15 | 76.3 ± 8.0 | 180.0 ± 6.0 | variable cam | hypertrophy |

| Hyp-Disc | 15 | 79.3 ± 9.9 | 183.0 ± 7.0 | disc plate | hypertrophy |

| Str-Cam | 15 | 74.8 ± 6.0 | 181.4 ± 6.5 | variable cam | maximal strength |

| Str-Disc | 15 | 75.7 ± 7.6 | 182.1 ± 4.3 | disc plate | maximal strength |

| CG | 15 | 79.2 ± 8.7 | 183.0 ± 6.0 | control group | |

Hyp-Cam (hypertrophy training with variable cam), Hyp-Disc (hypertrophy training with disc plate), Str-Cam (maximal strength training with variable cam), Str-Disc (maximal strength training with disc plate), CG (control group).

no significant differences between the groups, p >.05.

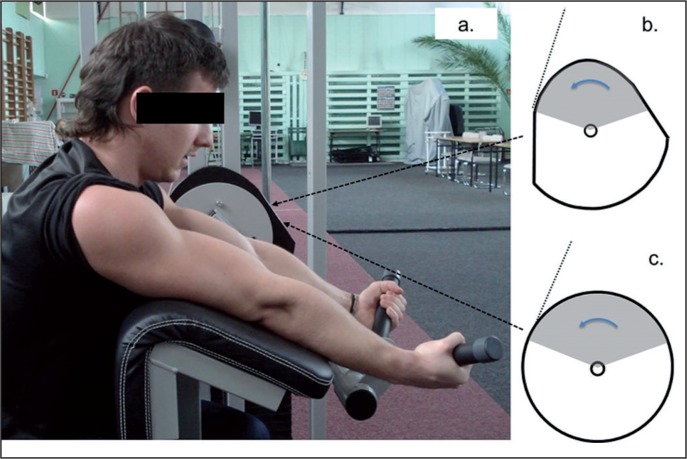

Two types of training machines were used (Fig. 1). One was equipped with a disc plate with constant resistance (for Hyp-Disc and Str-Disc groups) and the other with a variable-resistance cam adjusted to match muscle torque (for Hyp-Cam and Str-Cam groups). This second machine was based on a specially constructed cam that provides the optimal stimulation of the muscles regarding each given position of the elbow joint. The shape of the designed variable cam was based on the maximal muscle torque measurements taken also with the electromyographic (EMG) analysis of working muscles. The training load was selected individually for each person based on pre-training trials, with an accuracy of 5% 1RM. The external load was systematically monitored during training. Every other Monday, the one-repetition maximum (1RM) was measured on a training machine, immediately after a warm-up, but before the workout commenced. Subsequently, the exercise training load was increased in proportion to the increase in 1RM strength. The CG did not partake in any resistance training. All men participated in pre-training trials to familiarize themselves with the training machine, training protocols and testing procedures.

FIG. 1.

(a) Participant on the training machine, (b) shape of the specially designed cam, (c) shape of the disc plate. The active angle of the cam and disc (grey part) and rotation direction are indicated.

Muscle size, muscle strength and CK assessments

In all groups, muscle size and strength were assessed on three occasions: before training, after the fourth week of training, and after completion of training (at the end of eight weeks). Peak torque values of the elbow flexors were measured under isokinetic conditions, based on a 3RM effort, using a Biodex System 3 Pro (USA) device with angular velocity set at 30°/s, which was the closest value for movement velocity on the training machine. The participants received verbal motivation to apply maximum effort. Arm circumference at rest (halfway along the arm length) and with tension (at the broadest point) was measured using a metric tape with an accuracy of 1 mm. Skinfold thickness was assessed on the anterior (biceps brachii muscle) and posterior (triceps brachii muscle) sides of the arm using a Holtain Skinfold Caliper with an accuracy of 0.1 mm. The anthropometric measurements were taken using established principles. All data were taken by the same investigators to eliminate bias. It is assumed that the errors for anthropometric measurements are at a level below 10% for skinfold thickness and 2% for arm circumference [27–28].

On Monday, the week before training commenced, resting plasma creatine kinase (CK) activity was measured with follow-up assessments in the fourth and fifth weeks of training. Additionally, CK was measured on Monday mornings (pre-workout) and Friday afternoons (post-workout) to monitor for any muscle damage arising from exercise that week. Blood was collected from the earlobe after making a small incision with a sterile lancet. The samples were centrifuged and CK was measured using spectrophotometry, at a wavelength of 340 nm, using sets manufactured by Alpha-Diagnostics (Poland). The measurements were taken at 37°C and expressed in U/L.

Statistical analysis

The normality of distributions was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The observed differences were assumed to be significant at a probability level of p<.05. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measurements was used to evaluate within-group changes and between-group differences in physical performance and biomechanical and anthropometric parameters. Post-doc testing was conducted using Tukey’s honest significant different (HSD) test. Weekly changes in CK activity were similarly tested using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test. The CK data were log-transformed (natural logarithm) before analysis to meet normality assumptions. All data were analysed using the STATISTICA software package (version 10, StatSoft, Inc. 2011).

RESULTS

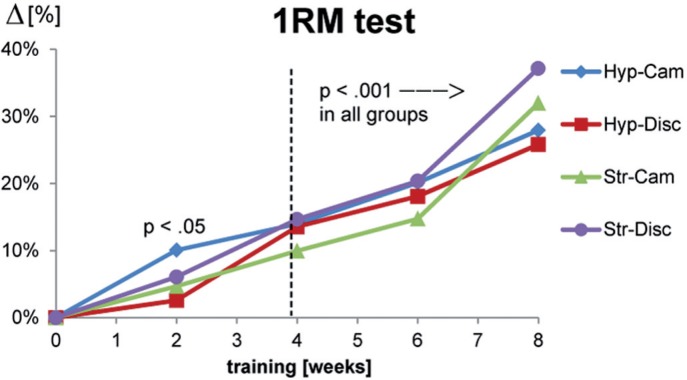

There were significant increases in 1RM test performance every two weeks in all training groups (p<.001), but no between-group differences in 1RM progression (p>.05). However, the 1RM test indicated that the Hyp-Cam group showed the most rapid response to the training load, whereby a higher 1RM test (p<.05) was found in the second week of training (Fig. 2). In the remaining training groups, 1RM performance increased (p<.001) after four weeks. After the 8-week training period, the highest 1RM values were observed after the strength training (Δ Str-Disc=37%; p<.001, Δ Str-Cam=32%; p<.001), with a smaller, several percentage increase after hypertrophy training (Δ Hyp-Disc=26%; p<.001, Δ Hyp-Cam=28%; p<.001), but the between-group differences were insignificant (p>.05).

FIG. 2.

Changes in the 1RM test on a training machine in relation to the pre-training data.

Hyp-Cam – hypertrophy training with variable cam; Hyp-Disc – hypertrophy training with disc plate; Str-Cam – maximal strength training with variable cam; Str-Disc – maximal strength training with disc plate. Significant difference in relation to pre-training data * p <.05, *** p <.001.

An increase in muscle torque (p<.001) was observed only in the Hyp-Cam group (Table 2). The increase in muscle torque in the Hyp-Cam group also differed significantly from the Str-Cam, Str-Disc and CG groups (p<.05).

TABLE 2.

Mean ± SD values of the evaluated biomechanical and anthropometric parameters measured at pre-training (pre), mid-training (mid) and post-training (post).

| Group | Peak torque [Nm] | Circumference at rest [cm] | Circumference in tension [cm] | Skinfold biceps [mm] | Skinfold triceps [mm] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyp-Cam | pre mid post |

64.9 ± 12.5 70.0 ± 11.1 73.8 ± 10.2c |

31.1 ± 2.7 31.4 ± 2.9 32.8 ± 3.1c |

34.6 ± 3.0 34.9 ± 2.8 35.7 ± 3.0c |

4.9 ± 1.1 4.8 ± 1.0 4.5 ± 0.9 |

8.7 ± 2.4 8.7 ± 2.2 6.9 ± 1.9b |

| Hyp-Disc | pre mid post |

63.3 ± 7.7 64.5 ± 9.2 66.8 ± 7.3 |

30.6 ± 2.6 30.7 ± 2.6 31.7 ± 2.6c |

34.2 ± 2.8 34.5 ± 2.9 35.2 ± 2.7c |

5.1 ± 2.2 5.2 ± 2.2 4.9 ± 1.9 |

9.6 ± 3.9 8.6 ± 2.9 8.2 ± 3.2a |

| Str-Cam | pre mid post |

63.3 ± 9.7 63.1 ± 8.5 63.4 ± 9.0 |

29.9 ± 1.6 30.0 ± 1.9 30.2 ± 1.8 |

33.3 ± 1.7 33.6 ± 1.9 33.9 ± 2.0b |

4.8 ± 1.0 3.8 ± 0.7c 3.7 ± 0.7c |

7.9 ± 2.2 6.5 ± 1.8b 5.8 ± 1.8c |

| Str-Disc | pre mid post |

62.4 ± 9.0 62.7 ± 8.9 64.3 ± 9.5 |

29.7 ± 2.5 29.8 ± 2.3 29.9 ± 2.4 |

33.0 ± 2.4 33.4 ± 2.4 33.6 ± 2.4b |

4.1 ± 0.8 3.7 ± 0.8a 3.4 ± 0.8c |

6.7 ± 2.4 5.3 ± 2.0a 5.2 ± 1.5b |

| CG | pre mid post |

66.1 ± 7.4 64.2 ± 7.5 66.7 ± 7.6 |

30.3 ± 2.2 30.0 ± 2.1 30.5 ± 2.1 |

33.4 ± 2.3 33.4 ± 2.3 33.5 ± 2.5 |

4.9 ± 1.3 4.9 ± 1.2 4.8 ± 1.3 |

8.2 ± 1.9 8.6 ± 2.6 8.1 ± 1.9 |

Significant difference in relation to pre-training data

p <.05,

p <.01,

p <.001.

Table 2 presents the absolute values of muscle torques, arm circumference and skinfold thickness measured before (pre), during (mid) and after (post) training. In both groups (Hyp-Cam and Hyp-Disc), the values of arm circumference at rest increased post-training by more than 1 cm (p<.001) and were statistically higher than in other groups. There were no significant changes in arm size with strength training. Arm circumference with hypertrophy training was greater compared to baseline values by over 1 cm (p<.001), whilst arm circumference with strength training increased by around 0.6 cm (p<.01).

Skinfold thickness on the anterior part of the arm (biceps) decreased only in the Str-Cam and Str-Disc groups (p<.001). Significant changes occurred after four weeks of training and were maintained until the experiment ceased. Skinfold thickness on the posterior part of the arm (triceps) decreased significantly in all four training groups (by 1.4–2.1 mm), although in the Str-Cam (p<.001) and Str-Disc (p<.01) groups, the changes appeared after four weeks, and in the Hyp-Disc (p<.05) and Hyp-Cam (p<.01) groups, significant differences from pre-training occurred only after eight weeks. The CG group did not exhibit any significant changes in any biomechanical or anthropometrical parameter.

The course of changes in CK activity was similar in all training groups (Table 3). We observed higher CK activity level on Friday compared to Monday. In terms of hypertrophy training, significant changes occurred only in the Hyp-Disc group (p=.006), while in the Hyp-Cam group there was no significant change (p=.411). For both strength-training groups, significant changes in CK activity were noted in the Monday-Friday system (Str-Cam p=.036, Str-Disc p=.021). In the control group, no significant changes in CK activity between Monday and Friday were noted during the same period (p=.569).

TABLE 3.

Mean ± SD values of plasma creatine kinase activity in each group during two consecutive weeks of training.

| Group | Monday [U/L] | Friday [U/L] | Monday [U/L] | Friday [U/L] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyp-Cam | 481 ± 258 | 675 ± 267 | 468 ± 247 | 706 ± 361 |

| Hyp-Disc | 348 ± 172 | 568 ± 234a | 347 ± 142 | 588 ± 372a |

| Str-Cam | 374 ± 165 | 598 ± 306a | 360 ± 136 | 561 ± 245a |

| Str-Disc | 288 ± 113 | 474 ± 169a | 334 ± 141 | 404 ± 154a |

| CG | 410 ± 299 | 442 ± 266 | 406 ± 233 | 413 ± 226 |

Significant difference in relation to CK activity on Monday

p <.05.

DISCUSSION

The exercises on the training machine used in this study proved to be an efficient form of elbow flexion training. As a direct outcome of the training, the values of maximal load (1RM) lifted in a test performed on a training machine every two weeks increased for all training groups. The value of 1RM is a parameter frequently used in sports practice to evaluate the efficiency of strength training [29–33]. Admittedly, the 1RM test does not allow peak torque of the working muscles to be determined. Nonetheless, the capability to overcome a higher external resistance, which increases due to the training, may be an indirect indicator of the increase in muscle strength that enables the trainee to overcome this load [34].

After eight weeks of training, muscle torque increased significantly, but only in men engaging in hypertrophy training on a machine with a variable cam (Hyp-Cam). The changes in the rest of the groups were not statistically significant (p>.05). Boyer [35] observed a similar phenomenon and reported that in the case of various measurement methods, the decidedly highest post-training increase in muscle torque was noted under the same conditions as the muscle training performed in this study. This is also confirmed in the study by Lehnert et al. [8], who, after a 12-week period of training (three times a week) of knee flexors and extensors using a hydraulic resistance machine, did not note a significant increase in torques measured under isometric conditions with an isokinetic dynamometer. However, when the measurements of maximal strength are conducted under the same conditions as the training effort, then for isometric conditions, as shown by Driss et al. [36], four weeks of training of the elbow flexors are enough to observe a significant increase in the torque of these muscles. Probably therefore, in our experiment greater final increases in the 1RM test occurred in groups performing maximal strength training because these athletes practised with the 1RM value in each training session. According to the training method, they improved their maximal strength capabilities on the training machine but not under isokinetic conditions.

Initial adaptations to resistance training are thought to be neural in origin (e.g. motor unit recruitment, threshold of recruitment, inter-muscular coordination), whereas structural changes in muscle morphology tend to occur later in the training process [37–39]. In the present study, changes in muscle size only appeared after eight weeks of training, especially in those groups prescribed hypertrophy training. However, strength training had a clear effect (i.e. decrease) on skinfold thickness in the upper arm, and this was evident after only four weeks of training. Notably, strength training produced a significant decrease in skinfold thickness, without a change of arm circumference. In such a case, we assume that some hypertrophy did occur, causing the simultaneous decrease in skinfold thickness. This is confirmed by Lowery et al. [40], who, based on the ultrasonographic measurements of the biceps brachii muscle, confirmed the hypertrophy effect after just four weeks of resistance training.

All training groups demonstrated a similar time course of changes in CK activity. It is worth noting that CK activity on consecutive Mondays was at a similar level, so two days without exercise (Saturday and Sunday) provided enough time for restoring CK levels back to baseline values. Because the CK changes were similar in the Str-Cam and the Str-Disc groups, it can be concluded that modification of the cam’s shape in maximal strength training did not result in additional muscle damage. On the other hand, hypertrophy training with a variable cam (Hyp-Cam group) was a less strenuous stimulus for inducing muscle damage than using a machine with a disc plate (Hyp-Disc group). It can be concluded that in resistance training methods requiring a greater number of repetitions in the sets, it is more effective to train on a machine with a custom-made variable cam. Damas et al. [41] found that resistance training protocols that do not promote significant muscle damage still induce similar muscle hypertrophy and strength gains compared to conditions that do promote initial muscle damage. Thus, they concluded that muscle damage is not the process that potentiates muscle hypertrophy in resistance training. Based on the above, in our experiment, the increase of CK activity indicates greater damage of muscles while training on the machine with the disc plate than with a variable cam, whereas use of a variable cam caused optimal muscle load during the whole range of motion, and therefore less damage of muscles fibres.

The use of a round disc plate for transferring the load causes the muscles to work with maximum load only in part of the range of motion. A properly constructed cam gives the opportunity to perform effort with the maximum load in the entire range of motion, which leads to higher values of mechanical work than using a round disc plate. It is connected with the safety and effectiveness of training. For the analysed flexion movement in the elbow joint, the maximum values are reached in the middle of the motion range and are greater than the values for the extreme ranges (start and finish of the elbow flexion) by about 30%. Thus, exercising the elbow flexors on the device with a round disc plate is possible but less effective than the device with a variable cam. The problem may occur in other human joints, where the characteristics of the course of forces as a function of the joint angle are different. Only an appropriate variable cam selected for a specific muscle function guarantees an equal load in the entire range of motion in the joint.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, the effectiveness of using the optimized training machine was confirmed in the measurement of maximal torque under isokinetic conditions, where changes were noted in the group performing hypertrophy training on a machine with a variable cam. The measurements of CK activity indicate smaller amounts of damage to muscle fibres in the efforts performed on the machine with a variable cam, but only in the case of hypertrophy training. This was due to adjustment of the shape of the variable cam to the strength capabilities throughout the entire range of motion of the elbow joint, which resulted in an equal load on the muscles during the entire exercise and provided a beneficial variant of muscle work. A greater overload of working muscles was observed for training using the machine with a disc plate and a constant resistance, where the elbow flexors were forced to work with a non-adjusted load, which resulted in greater damage to the structure of working muscles as shown by the accumulation of CK.

It is worth remembering that in every human joint, the characteristics of change in the values of muscle torques proceed differently. The appropriate choice of a cam in training machines seems to be an important element for conditioning the effectiveness of a training process, and the shape of the cam should match the strength capabilities of muscles throughout the entire range of motion in the joint. In methods of elbow flexion training involving a greater number of repetitions in a set, the use of an optimized variable cam has a positive effect on post-training outcomes. On the other hand, when the aim of the training is to increase maximal strength through single repetitions with maximal resistance, the method of transferring the load on a machine for exercising elbow flexors does not have a significant effect on the effectiveness of the training. But even if there are no differences in post-training effects, the optimally constructed cam has a positive influence on the safety and comfort of the exercises. Based on the results and conclusions, it seems necessary to continue research on optimising cam shapes for other muscle groups and to conduct further experiments to assess the effectiveness of their use in different training variants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education under Grant No. Ds-154 of the University of Physical Education in Warsaw.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahtiainen JP, Pakarinen A, Alen M, Kraemer WJ, Häkkinen Keijo. Short vs. Long rest period between the sets in hypertrophic resistance training: influence on muscle strength, size, and hormonal adaptations in trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(3):572–82. doi: 10.1519/15604.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher J, Steele J, Smith D. Evidence-based resistance training recommendations for muscular hypertrophy. Med Spor. 2013;17(4):217–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, Dudley GA, Dooly C, Feigenbaum MS, Fleck SJ, Franklin B, Fry AC, Hoffman JR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2002;34(2):364–80. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200202000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenfeld BJ, Pope ZK, Benik FM, Lhester GM, Sellers J, Nooner JL, Schnaiter JA, Bond-Williams KE, Carter AS, Ross CL, et al. Longer interset rest periods enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy in resistance-trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(7):1805–12. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baechle TR, Earle RW, Wathen D. Resistance training. In: Baechle TR, Earle RW, editors. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2008. pp. 381–411. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judge LW, Burke JR. The effect of recovery time on strength performance following a high-intensity bench press workout in males and females. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2010;5:184–96. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.5.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marinković M, Bratić M, Ignjatović A, Radovanović D. Effects of 8-week instability resistance training on maximal strength in inexperienced young individuals. Serb J Sports Sci. 2012;1(5):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehnert M, Stastny P, Sigmund M, Xaverova Z, Hubnerova B, Kostrzewa M. The effect of combined machine and body weight circuit training for women on muscle strength and body composition. J Phys Educ Sport. 2015;15(3):561–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manfredini Baroni B, Silveira Pinto R, Herzog W, Vaz MA. Eccentric resistance training of the knee extensor muscle: Training programs and neuromuscular adaptations. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2015;23(3):183–98. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoenfeld BJ, Contreras B, Tiryaki-Sonmez G, Willardson JM, Fontana F. An electromyographic comparison of a modified version of the plank with a long lever and posterior tilt versus the traditional plank exercise. Sports Biomech. 2014;13(3):296–306. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2014.942355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuchiya Y, Kikuchi N, Shirato M, Ochi E. Differences of activation pattern and damage in elbow flexor muscle after isokinetic eccentric contractions. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2015;23(3):169–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer JT, Beck TW, Housh TJ, Masseyc LL, Marekc SM, Danglemeierc S, et al. Acute effects of static stretching on characteristics of the isokinetic angle – torque relationship, surface electromyography, and mechanomyography. J Sports Sci. 2007;25(6):687–98. doi: 10.1080/02640410600818416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulig K, Andrews JG, Hay JG. Human strength curves. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1984;12:417–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHugh MP, Tetro DT. Changes in the relationship between joint angle and torque production associated with the repeated bout effect. J Sports Sci. 2003;21(11):927–32. doi: 10.1080/0264041031000140400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira LF, Matta TT, Alves DS, Garcia MAC, Vieira TMM. Effect of the shoulder position on the biceps brachii EMG in different dumbbell curls. J Sports Sci Med. 2009;8(1):24–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philippou A, Maridaki M, Bogdanis GC. Angle-specific impairment of elbow flexors strength after isometric exercise at long muscle length. J Sports Sci. 2003;21(10):859–65. doi: 10.1080/0264041031000140356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pigeon P, Yahia L, Feldman AG. Moment arms and lengths of human upper limb muscles as functions of joint angles. J Biomech. 1996;29(10):1365–70. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folland J, Morris B. Variable-cam resistance training machines: Do they match the angle - torque relationship in humans? J Sports Sci. 2008;26(2):163–9. doi: 10.1080/02640410701370663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasenoehrl T, Wessner B, Tschan H, Vidotto C, Crevenna R, Csapo R. Eccentric resistance training intensity may affect the severity of exercise induced muscle damage. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017;57(9):1195–204. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.16.06476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ide BN, Soares Nunes LA, Brenzikofer R, Macedo DV. Time course of muscle damage and inflammatory responses to resistance training with eccentric overload in trained individuals. Mediators Inflamm. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/204942. Article ID 204942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS, Abe T. Does blood flow restriction result in skeletal muscle damage? A critical review of available evidence. Scand J Med Sci Spor. 2014;24(6):e415–22. doi: 10.1111/sms.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado M, Pereira R, Sampaio-Jorge F, Knifis F, Hackney A. Creatine supplementation: effects on blood creatine kinase activity responses to resistance exercise and creatine kinase activity measurement. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2009;45(4):251–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabell L, Zebas C. Resistive torque validation of the nautilus multi-biceps machine. J Strength Cond Res. 1999;13(1):20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalleau G, Baron B, Bonazzi B, Leroyer P, Verstraete T, Verkindt C. The influence of variable resistance moment arm on knee extensor performance. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(6):657–65. doi: 10.1080/02640411003631976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagen M, Lemke M, Kutsch H, Lahner M. Development of a functional anatomical subtalar pronator and supinator strength training machine. Technol Health Care. 2015;23(5):627–35. doi: 10.3233/THC-151004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staniszewski M, Urbanik C, Mastalerz A, Iwańska D, Madej A, Karczewska M. Comparison of changes in the load components for intense training on two machines: with a variable-cam and with a disc plate. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017;57(6):782–9. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.16.06350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lochman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Illinoi, USA: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. Hall JG, Allanson JE, Gripp KW, Slavotinek AM. Handbook of Physical Measurements. Oxford University Press 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Thornton JC, Kolesnik S, Pierson RN. Anthropometry in body composition: an overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;904:317–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campanholi Neto J, Cedin L, Dato CC, Rodrigues Bertucci D, De Andrade Perez SE, Baldissera V. A single session of testing for one repetition maximum (1RM) with eight exercises is trustworthy. J Exerc Physiol Online. 2015;18(3):74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flores FJ, Sedano S, Redondo JC. Optimal load and power spectrum during snatch and clean: differences between international and national weightlifters. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2017;17(4):521–33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karsten B, Stevens L, Colpus M, Larumbe-Zabala E, Naclerio F. The effects of a sport-specific maximal strength and conditioning training on critical velocity, anaerobic running distance, and 5-km race performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;11(1):80–5. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribeiro AS, Do Nascimento MA, Mayhew JL, Ritti-Dias RM, Avelar A, Okano AH, Cyrino ES. Reliability of 1RM test in detrained men with previous resistance training experience. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2014;22(2):137–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verdijk LB, van Loon L, Meijer K, Savelberg HM. One-repetition maximum strength test represents a valid means to assess leg strength in vivo in humans. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(1):59–68. doi: 10.1080/02640410802428089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naclerio FJ, Jiménez A, Alvar BA, Peterson MD. Assessing strength and power in resistance training. J Hum Sport Exerc. 2009;4(2):100–13. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyer B. A comparison of the effects of three strength training programs on women. J Appl Sports Sci Res. 1990;4(3):88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Driss T, Serrau V, Behm DG, Lesne-Chabran E, Le Pellec-Muller A, Vandewalle H. Isometric training with maximal co-contraction instruction does not increase co-activation during exercises against external resistances. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(1):60–9. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2013.805238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Lemos Muller CH, Ramis TR, Ribeiro JL. Comparison of the effects of resistance training with and without vascular occlusion in increases of strength and hypertrophy: A review of the literature. Sports Med. 2015;11(4):2668–75. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mangine GT, Hoffman JR, Fukuda DH, Stout JR, Ratamess NA. Improving muscle strength and size: The importance of training volume, intensity, and status. Kinesiol. 2015;47(2):131–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tillin NA, Pain MG, Folland JP. Short-term training for explosive strength causes neural and mechanical adaptations. Exp Physiol. 2012;97(5):630–41. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.063040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowery RP, Joy JM, Loenneke JP, Souza EO, Machado M, Dudeck JE, Wilson I. Practical blood flow restriction training increases muscle hypertrophy during a periodized resistance training programme. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014;34(4):317–21. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damas F, Libardi CA, Ugrinowitsch C. The development of skeletal muscle hypertrophy through resistance training: the role of muscle damage and muscle protein synthesis. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118(3):485–500. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]