Abstract

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and alcohol use disorder often co-occur, yet we know little about risk processes underlying this association. We tested two mechanistic pathways linking BPD symptoms and alcohol-related problems. In the “affective pathway,” we hypothesized that BPD symptoms would be associated with alcohol-related problems through affective instability and drinking to cope. In the “sensation-seeking pathway,” we proposed that BPD symptoms would be related to alcohol-related problems through sensation seeking and drinking to enhance positive experiences. We tested a multiple mediation model using age-18 cross-sectional data from the Pittsburgh Girls Study. Results supported both pathways: BPD symptoms had an indirect effect on alcohol-related problems by (1) affective instability and coping motives (β = .03, p < .05), and (2) sensation-seeking and enhancement motives (β = .02, p < .05). These results highlight coping and enhancement drinking motives as possible mechanisms that explain co-occurrence of BPD symptoms and alcohol-related problems in young females.

Keywords: alcohol-related problems, borderline personality disorder, coping motives, enhancement motives, pathways to alcohol problems

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by pervasive dysregulation in major areas of functioning, including emotional, behavioral, cognitive, interpersonal, and self (Linehan, 1993; Trull, 1995). Approximately 75% of individuals diagnosed with BPD are female (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), and about half also have a co-occurring alcohol use disorder (AUD; Trull, Jahng, Tomko, Wood, & Sher, 2010; Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, & Burr, 2000; Walter et al., 2009). Females are at greater risk for some types of alcohol-related problems compared to males (e.g., blacking out), underscoring the importance of examining both BPD and alcohol-related problems in female samples (Sugarman, DeMartini, & Carey, 2009). Although BPD symptoms and alcohol-related problems often co-occur, little is known regarding mechanistic pathways underlying their association. This study examined drinking motives, or the reasons that an individual consumes alcohol, as a possible mechanism that links BPD with alcohol-related problems. Examining drinking motives can provide insight into how personality characteristics could put individuals at risk for problem drinking, and inform intervention targets.

According to a motivational model of alcohol use (Cooper, Kuntsche, Levitt, Barber & Wolf, 2014; Cox & Klinger, 2011), individuals drink to meet specific needs, such as coping with negative affect. Coping and enhancement motives for drinking have, in turn, been associated with alcohol-related problems (Cooper, 1994; Merrill & Read, 2010; Studer et al., 2016). Importantly, drinking motives reflect specific needs that have been linked to personality features, such as affective instability and sensation seeking. Specifically, the BPD symptom of affective instability has been associated with coping motives for alcohol use (Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005; Theakston, Stewart, Dawson, Knowlden-Loewen, & Lehman, 2004). In contrast, sensation seeking, a personality trait that may also be elevated among individuals with BPD (Linehan, 1993), has been associated with enhancement motives for drinking (e.g., drinking to increase positive feelings) (Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005). Based on this prior research, we hypothesized that the BPD symptom of affective instability would be associated with coping motives, whereas sensation seeking would be associated with enhancement motives for drinking.

Since coping and enhancement drinking motives have shown associations with personality features and alcohol-related problems, these motives could link BPD features of affective instability and sensation seeking with alcohol-related problems through distinct mechanistic pathways. For example, research has shown that coping motives mediated the association between neuroticism and alcohol use (Hussong, 2003), whereas enhancement motives mediated the association between sensation seeking and alcohol use (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007; Simons et al., 2005). Although some research has explored drinking motives as mediators of the association between personality traits and substance use (Cooper et al., 2014), few studies have focused on specific BPD symptoms and related personality traits in relation to drinking motives, despite high rates of co-occurring BPD and AUD. Elucidating distinct pathways to alcohol-related problems among young women will increase our understanding of how BPD symptoms could put certain individuals at risk for alcohol-related problems, and help to identify targets for intervention (e.g., emotion regulation skills, drinking motives).

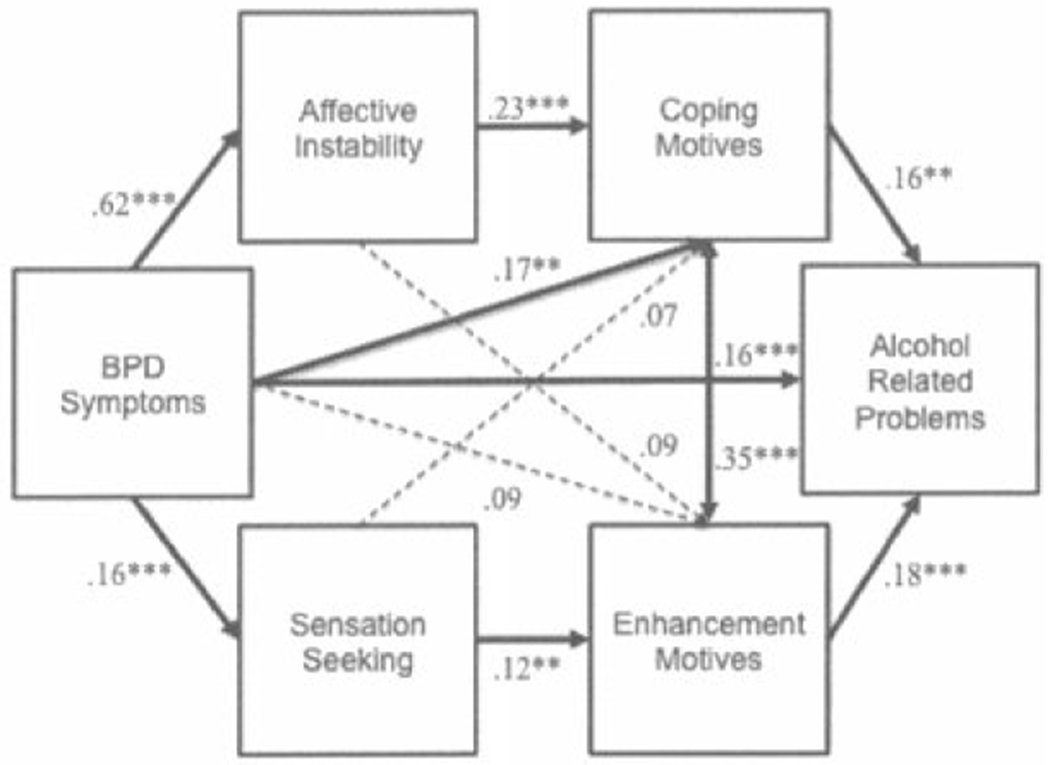

In the current study, we examined the extent to which affective instability and sensation seeking were associated with alcohol-related problems through two distinct pathways. In the “affective pathway,” we expected that BPD symptoms would be associated with alcohol-related problems through affective instability and coping motives. In the “sensation-seeking pathway,” we expected that BPD symptoms would be associated with alcohol-related problems through sensation seeking and enhancement motives (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Structural equation model results testing a conceptual model of affective and sensation-seeking pathways from borderline personality disorder symptoms to alcohol-related problems. N = 2,101. Model fit: χ2 = .45, p > .05, df = 2; RMSEA < .01; CFI/TLI = 1.00. All effects are standardized. Dashed lines show non-significant paths, solid lines show significant paths. Race and public assistance were included as covariates (not shown here). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

Data were drawn from the Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS), an ongoing longitudinal study using an accelerated longitudinal design that began in 2000 with 2,450 5- to 8-year-old girls. The sample was identified by a stratified sampling of 103,238 households in the city of Pittsburgh, in which households in low-income neighborhoods were oversampled. Of 3,118 age-eligible girls, 2,876 were asked to take part in the longitudinal study, and of these 2,450 (85%) agreed to participate. At assessment wave 1 (girl ages 5–8), 25% of families had an annual income below the poverty threshold, 53% of girls were Black, 41% were White, and 7% were more than one race (see further details in Hipwell et al., 2002). The current analyses focus on 2,101 females (86% of total sample) who completed the PGS assessment at age 18 (waves 11–14). Most participants were living at home with their caregivers (60%) and were either not working (47%) or working part-time (30%); 40% had received public assistance. Attrition analyses revealed that participants who identified as White and who were not receiving public assistance at wave 1 were less likely to complete the assessment at age 18.

PROCEDURE

In-home interviews were conducted annually by trained interviewers using a laptop computer. Written informed consent was obtained prior to conducting the interview. The study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Human Research Protection Office. Participants were compensated for completing the assessment.

MEASURES

Motivations for Drinking.

Motivations for drinking were reported using the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994) if the participant had consumed five or more drinks in the past year (n = 666). Two subscales were examined: four items assessing coping motives (e.g., drinking to forget problems, drinking when depressed/anxious) and five items assessing enhancement motives (e.g., drinking because it is fun; drinking because I like the feeling). Items were rated on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = never; 1 = some of the time; 2 = most of the time) and summed for each subscale (coping motives: range = 0–8; α = .87; enhancement motives: range = 0–10; α = .78).

BPD Symptoms.

The International Personality Disorders Examination (IPDE-BOR; Loranger et al., 1994) includes 10 items that reflect Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria for BPD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Participants reported on the presence (0 = no; 1 = yes) of symptoms within the past year. IPDE-BOR has shown convergent validity with interview and self-report measures of BPD (e.g., Chanen et al., 2008; Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007). Symptom levels ranged from 0 to 9 in the current sample, and internal consistency was acceptable (α = .69). In the current sample, 17% (n = 414) reported four or more symptoms, which is considered to be in the clinically significant range (Smith, Muir, Blackwood, 2005; Stepp, Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2011).

Affective Instability.

The seven-item Personality Assessment Inventory–Borderline Features (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991) was used to measure affective instability. Items (e.g., mood can shift quite suddenly, have little control over anger) were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = false, 2 = slightly true, 3 = mainly true, or 4 = very true; range = 0–21; α = .78). The PAI-BOR has been demonstrated to have excellent construct validity (Slavin-Mulford et al., 2012).

Sensation Seeking.

Sensation seeking was self-reported using the Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale (CADS; Lahey et al., 2008). The scale includes four items (e.g., daring or adventurous, enjoys risky or dangerous things) rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = just a little, 2 = pretty much, 3 = very much) that were summed to create the sensation-seeking score (range = 0–12; α = .80).

Alcohol Use.

Frequency of alcohol use in the past year was assessed using the Nicotine, Alcohol and Drug Use Questionnaire (Pandina, Labouvie, & White, 1984), coded as: 0 = none, 1 = less than 5 times, 2 = more than 5 times but less than 1 month, 3 = about once a month, 4 = about once a week, 5 = a couple times a week, 6 = nearly every day, and 7 = every day or more than once a day.

Alcohol-Related Problems.

Participants who responded “yes” to the following screening item, “Did you drink 5 or more full drinks (not sips) of alcohol, including beer, wine, and/or hard liquor in the past year?” were assessed for alcohol-related problems. One drink equals one full can of beer, one glass of wine, or one shot of liquor. Alcohol-related problems in the past year were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview–Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM; World Health Organization, 2001–2012) if the participant reported drinking five or more drinks in the past year (n = 666). The CIDI-SAM has good test-retest reliability (Rubio-Stipec, Peters, & Andrews, 1999) and validity (Compton, Cottler, Dorsey, Spitznagel, & Magera, 1996). Ten alcohol-related problems (e.g., alcohol use interfered with school/work, neglected responsibilities due to alcohol use, alcohol use resulted in physical fights, alcohol use despite interpersonal problems) were rated on a 4-point scale (0 = none to 3 = three or more times), and summed to create an alcohol severity scale (range = 0–30; α = .80).

Control Variables.

Race (0 = White, 1 = Black or other race/ethnicity) and use of public assistance in the past year (0 = no, 1 = yes) were assessed using a demographic questionnaire.

DATA ANALYSIS

Primary study hypotheses were evaluated using a structural equation model (see Figure 1) that tested mediation in Mplus version 8 (Muthén Muthén, 2017). We included all participants with data at age 18 (N = 2,101) in the analysis so that the paths between BPD symptoms and affective instability, and BPD symptoms and sensation seeking, would reflect all available data. The paths involving alcohol-related variables (e.g., drinking motives, alcohol-related problems) consisted of a smaller sample (n = 666 participants who reported drinking five or more drinks in the past year). When analyses were rerun including only participants who reported five or more drinks in the past year, the pattern of results was similar to analyses using all participants. Thus, we present results for analyses using all participants with data at age 18. We also tested a model in which frequency of alcohol use was the outcome, but since this model did not converge, we report results only for the model testing alcohol-related problems as the outcome.1

All models were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood estimation with standard errors and a chi-square statistic that is robust to non-normality (MLR estimator). Overall model fit was evaluated using chi-square statistic (Δχ2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the CFI/TLI, conventional cutoff values of .90 or greater indicate acceptable fit and .95 or greater indicate good fit (McDonald & Ho, 2002). RMSEA values below .08 represent an acceptable fit (Kline, 2005; McDonald & Ho, 2002) New York. All paths between constructs of interest were estimated, and hypothesized mediation pathways were tested using the INDIRECT command. Effects of race and public assistance were controlled in all analyses. Within the text and tables, we report effect sizes as standardized βs.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides sample descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between study variables. BPD symptoms were strongly correlated with affective instability (r = .63, p < .01) and weakly correlated with sensation seeking (r = .14, p < .01). Affective instability was weakly correlated with sensation seeking (r = .09, p < .01) and enhancement motives (r = .11, p < .01), but moderately correlated with coping motives (r = .37, p < .01) and alcohol-related problems (r = .24, p < .01). Sensation seeking was weakly correlated with coping motives (r = .10, p < .05) and moderately correlated with enhancement motives (r = . 16, p < .01) and alcohol-related problems (r = .19, p < .01).

TABLE 1.

Intercorrelations and Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Mean/% (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Race (African American/Other) | 61% | |||||||

| 2. Public Assistance | 40% | .35** | ||||||

| 3. BPD Symptoms | 1.97 (1.81) | .16** | .10** | |||||

| 4. Affective Instability | 5.92 (3.89) | .18** | .13** | .63** | ||||

| 5. Sensation Seeking | 4.99 (2.87) | −.09** | −.08** | .14** | .09** | |||

| 6. Coping Motives | 1.67 (1.95) | .09* | .06 | .36** | .38** | .10* | ||

| 7. Enhancement Motives | 4.79 (2.36) | −.10** | −.12** | .14** | .11** | .16** | .37** | |

| 8. Alcohol-Related Problems | 1.19 (2.70) | .04 | .01 | .29** | .24** | .19** | .31** | .28** |

Note. N = 2,101; except for drinking-related variables: coping and enhancement motives, alcohol-related problems (n = 666 who reported consuming live or more drinks in the past year); BPD = borderline personality disorder; SD = standard deviation.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1 depicts the structural equation model that fit the data well (χ2 = .45, p > .05, df = 2; RMSEA < .01; CFI/TLI = 1.00). First, affective instability mediated the association between BPD symptoms and coping motives (β = .23, p < .001), but not enhancement motives. On the other hand, sensation seeking mediated the association between BPD symptoms and enhancement motives (β = .02, p < .05), but not coping motives. Second, affective instability had an indirect effect on alcohol-related problems via coping motives (β = .05, p < .05). In parallel, sensation seeking had an indirect effect on alcohol-related problems via enhancement motives (β = .02, p < .05). In total, BPD symptoms had an indirect effect on alcohol-related problems by (1) the “affective instability” pathway through coping motives (β = .03, p < .05), and (2) the “sensation seeking” pathway through enhancement motives (β = .02, p < .05). Table 2 reports all estimated paths for the model.

TABLE 2.

Affective and Sensation-Seeking Pathways From Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms to Alcohol-Related Problems

| β | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Associations with Alcohol-Related Problems | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.07, 0.25 |

| Affective Instability | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.06, 0.13 |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.04, 0.21 |

| Coping Motives | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.07, 0.25 |

| Enhancement Motives | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.09, 0.26 |

| Associations with Coping Motives | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.07, 0.27 |

| Affective Instability | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.14, 0.33 |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.02, 0.15 |

| Associations with Enhancement Motives | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.01, 0.2O |

| Affective Instability | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.02. 0.19 |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.03, 0.20 |

| Associations with Affective Instability (AI) | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.59, 0.65 |

| Associations with Sensation Seeking (SS) | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.11, 0.22 |

| Indirect Effects | |||

| Affective pathway: | |||

| BPD → AI → Coping → Alcohol Problems | 0.023 | 0.009 | 0.006, 0.040 |

| Sensation-Seeking pathway: | |||

| BPD → SS → Enhancement → Alcohol Problems | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001, 0.006 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.012, 0.066 |

Note. N = 2,101; BPD = borderline personality disorder, CI = confidence interval.

Effects are after controlling for race and receipt of public assistance. Significant effects are bolded.

DISCUSSION

This study provides preliminary support for the hypothesis that among women the relationship between BPD symptoms and alcohol-related problems can be partially explained by two distinct pathways: an affective pathway involving BPD symptoms relating to elevated affective instability and drinking to cope, and a sensation-seeking pathway involving BPD symptoms relating to elevated sensation seeking and drinking to enhance positive feelings. These findings are consistent with a motivational model of alcohol use in which distinct personality characteristics can be linked to specific drinking motives (Cox & Klinger, 2011), which might help to explain why BPD symptoms could put individuals at risk for alcohol-related problems.

Although prior research has examined components of the affective pathway tested here (e.g., Garofalo & Velotti, 2015) or examined coping motives as a mediator of personality traits and substance use (Hussong, 2003), the current study expands on prior research by examining the specificity of coping (relative to enhancement) motives as a mediator of the association between BPD symptoms, affective instability, and alcohol-related problems. In this regard, young women who experience BPD symptoms, specifically affective instability, may engage in a problematic pattern of alcohol use (e.g., heavy episodic drinking) to regulate their affect (Garofalo & Velotti, 2015). Interventions to enhance emotion regulation and distress tolerance skills may aid in reducing use of alcohol to cope with negative emotions, and serve to reduce the disproportionate amount of alcohol-related problems experienced by individuals with BPD.

The sensation-seeking pathway identified in this study is consistent with prior research that found that enhancement motives linked sensation seeking with alcohol use (Simons et al., 2005; Magid et al., 2007). The current study builds on this research by examining sensation seeking in the context of BPD symptoms, rather than more broadly defined personality traits, and demonstrating relative specificity of enhancement motives as a mediator of the association between sensation seeking and alcohol-related problems. Among young women who report high sensation seeking and enhancement motives for drinking, enhancement motives for drinking may lead to episodes of high volume consumption or “binge drinking” (Adams, Kaiser, Lynam, Charnigo, & Milich, 2012). Thus, interventions for young women who report high sensation seeking and enhancement motives for alcohol use could focus on identifying and engaging in more adaptive ways to enhance positive feelings (e.g., exercise).

Findings from the current study should be considered within the context of the following limitations. First, generalizability of results may be limited (a) because this community-based sample represented 18-year-old women who reported relatively low average levels of BPD symptoms and alcohol-related problems, and (b) because of possible bias due to attrition over follow-up. Second, our model was tested using cross-sectional data, making it difficult to infer truly causal relationships among the constructs. However, we considered the present analyses to be exploratory. Additionally, we included only two drinking motives subscales. Although we found specificity of drinking motives for affective instability and sensation seeking in the mediation model tested here, further research is needed to examine other drinking motives. Individuals often report more than one reason for drinking, especially at higher levels of alcohol use (Cooper et al., 2014). Of note, coping and enhancement motives for drinking were moderately correlated in this sample (r = .37), and this association was accounted for in our mediation models, underscoring the unique contributions of coping and enhancement motives as mediators of two distinct risk pathways. Finally, while significant and in the expected direction, the main effects are small and best viewed as a proof of concept.

Results from this study suggest two pathways from BPD symptoms to alcohol-related problems among young women in a large urban community sample. In the affective pathway, BPD symptoms were linked to alcohol-related problems through affective instability and coping motives for alcohol use. In the sensation-seeking pathway, sensation seeking and enhancement motives for alcohol use mediated the association between BPD symptoms and alcohol-related problems. These two different motivational pathways suggest that skills-training interventions (e.g., emotion regulation or distress tolerance), which address specific BPD symptoms and corresponding drinking motives, could help to reduce alcohol-related harm among young women with BPD symptoms.

Supplementary Material

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Frequency of Number of Alcohol-Related Problems

| Number of problems | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 456 | 68.3 |

| 1 | 68 | 10.2 |

| 2 | 37 | 0.06 |

| 3 | 30 | 0.04 |

| 4 | 19 | 0.03 |

| 5 | 11 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 13 | 0.02 |

| 7 | 9 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 5 | 0.01 |

| 9 | 4 | 0.01 |

| 10 | 1 | 0.0 |

| 11 | 1 | 0.0 |

| 12 | 1 | 0.0 |

| 13 | 3 | 0.0 |

| 14 | 3 | 0.0 |

| 15 | 1 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 2 | 0.0 |

| 17 | 1 | 0.0 |

| 18 | 1 | 0.0 |

| 19 | 2 | 0.0 |

| Total | 668 | 100.0 |

Note. The number of participants who completed this measure is 668. Two participants reported drinking 5 + times during the past year but did not provide data on motivations for drinking.

TABLE A2.

Frequency of Alcohol-Related Problems by Item

| 0 Times |

1 Time |

2 Times |

3+ Times |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Description (n) | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| 1. Interfered with homework (643) | 575 | 89.4 | 24 | 3.7 | 28 | 4.4 | 16 | 2.5 |

| 2. Went to school drunk (656) | 621 | 94.7 | 19 | 2.9 | 9 | 1.4 | 7 | 1.1 |

| 3. Neglected responsibilities (668) | 604 | 90.4 | 23 | 3.4 | 21 | 3.1 | 20 | 3.0 |

| 4. Physical fights (668) | 625 | 93.6 | 25 | 3.7 | 11 | 1.6 | 7 | 1.0 |

| 5. Legal problems (668) | 653 | 97.8 | 12 | 1.8 | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Hazardous use (668) | 599 | 89.7 | 39 | 5.8 | 16 | 2.4 | 14 | 2.1 |

| 7. Risky sex (668) | 617 | 92.4 | 25 | 3.7 | 12 | 1.8 | 14 | 2.1 |

| 8. Frequently missed school (660) | 607 | 92.0 | 26 | 3.9 | 16 | 2.4 | 11 | 1.7 |

| 9. Frequent family arguments (668) | 614 | 91.9 | 30 | 4.5 | 13 | 1.9 | 11 | 1.6 |

| Yes |

No |

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| 10. Used despite interpersonal problems (54) | 33 | 61.1 | 21 | 38.9 | ||||

Note. These items create a summary construct of alcohol-related problems, which reflects a severity scale.

TABLE A3.

Affective and Sensation-Seeking Pathways From Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms to Alcohol Use

| β | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Associations with Alcohol-Related Problems | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.0, 0.19 |

| Affective Instability | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.08, 0.08 |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.16, 0.32 |

| Coping Motives | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02, 0.20 |

| Enhancement Motives | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.05, 0.20 |

| Associations with Coping Motives | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.08, 0.24 |

| Affective Instability | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.18, 0.35 |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.03, 0.17 |

| Associations with Enhancement Motives | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04, 0.14 |

| Affective Instability | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.06, 0.24 |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.07, 0.22 |

| Associations with Affective Instability (AI) | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.59, 0.64 |

| Associations with Sensation Seeking (SS) | |||

| BPD Symptoms | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.11, 0.21 |

| Indirect Effects | |||

| Affective pathway: | |||

| BPD → AI → Coping → Alcohol Problems | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.001, 0.019 |

| Sensation-Seeking pathway: | |||

| BPD → SS → Enhancement → Alcohol Problems | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000, 0.003 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.003, 0.021 |

Note. N = 2,101; BPD = borderline personality disorder; CI = confidence interval.

Effects are after controlling for race and receipt of public assistance. Significant effects are bolded.

Footnotes

We initially examined models with alcohol frequency defined as both continuous and count variables. We reran the model with alcohol frequency as a categorical, and results mirror those of the model predicting alcohol use problems. Specifically, there are significant indirect effects of BPD on alcohol use frequency via an affective pathway and a sensation-seeking pathway (see Appendix Table A3).

REFERENCES

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, & Milich R (2012). Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: Pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addictive Behavior, 37(7), 848–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, McDougall E, Yuen HP, Rawlings D, & Jackson HJ (2008). Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(4), 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Cottler LB, Dorsey KB Spitznagel EL, Magera DE (1996). Comparing assessments of DSM-IV substance dependence disorders using CIDI-SAM and SCAN. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 41(3), 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, & Mudar P (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S (2014). Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco In Sher KJ (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of substance use disorders, Volume 1 (e1–53). Oxford. UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, & Klinger E (2011). A motivational model of alcohol use: determinants of use and change In Cox WM & Klinger E (Eds.), Handbook of motivational counseling: Goal-based approach to assessment and intervention with addiction and other problems (2nd ed., pp. 131–158). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo C, & Velotti P (2015). Alcohol misuse in psychiatric patients and nonclinical individuals: The role of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity. Addition Theory and Research, 23(4), 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, Loeber R, Southamer-Loeber M, Keenan K, White HR, & Kroneman L (2002). Characteristics of girls with early onset disruptive and antisocial behavior. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 12 99–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM (2003). Social influences in motivated drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(2), 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Chronis AM, Jones HA, Williams SH, Loney J, Waldman ID (2008). Psychometrics characteristics of a measure of emotional dispositions developed to test a developmental propensity model of conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(4), 794–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, & Kessler RC (2007). DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 62(6), 553–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Linchan M (2015). DBT skills training manual. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, Berger P, Buchheim P, Channabasavanna SM, … Ferguson B (1994). The International Personality Disorder Examination. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(3), 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR (2007). Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors, 32(10), 2046–2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, & Ho MH (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, & Read JP (2010). Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 705–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC (1991). Personality Assessment Inventory, professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pandina RJ, Labouvie EW, & White HR (1984). Potential contributions of the life span developmental approach to the study of adolescent alcohol and drug use: The Rutgers Health and Human Development Project, a working model. Journal of Drug Issues, 14(2), 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Stipec M, Peters L, & Andrews G (1999). Test-retest reliability of the computerized CIDI (CIDI-Auto): Substance abuse modules. Substance Abuse, 20(4), 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, & Christopher MS (2005). An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(3), 326–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin-Mulford J, Sinclair SJ, Stein M, Malone J, Bello I, & Blais MA (2012). External validity of the personality assessment inventory (PAI) in a clinical sample. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94(6), 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Muir WJ, & Blackwood DHR (2005). Borderline personality characteristics in young adults with recurrent mood disorders: A comparison of bipolar and unipolar depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 87(1), 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Burke JD, Hipwell AE, & Loeber R (2012). Trajectories of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms as precursors of borderline personality disorder symptoms in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(1), 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer J, Baggio S, Dupuis M, Mohler-Kuo M, Daeppen J-B, & Gmel G (2016). Drinking motives as mediators of the associations between reinforcement sensitivity and alcohol misuse and problems. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, DeMartini KS, & Carey KB (2009). Are women at greater risk? An examination of alcohol-related consequences and gender. American Journal on Addictions, 18(3), 194–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theakston JA, Stewart SH, Dawson MY, Knowlden-Loewen SAB, & Lehman DR (2004). Big-Five personality domains predict drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(5), 971–984. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ (1995). Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: 1. Identification and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7(1), 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Jahng S,Tomko RL, Wood PK, & Sher KJ (2010). Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: Gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(4), 412–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks Brown C, Durbin J, & Burr R (2000). Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review; 20(2), 235–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M, Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM McGlashan TH, … Skodol AE (2009). New onsets of substance use disorders in borderline personality disorder over 7 years of follow-ups: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Addiction, 104(1), 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, & Reynolds SK (2005). Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality, 19(7), 559–574. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2001–2012). Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module. St. Louis, MO: Author [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.