Abstract

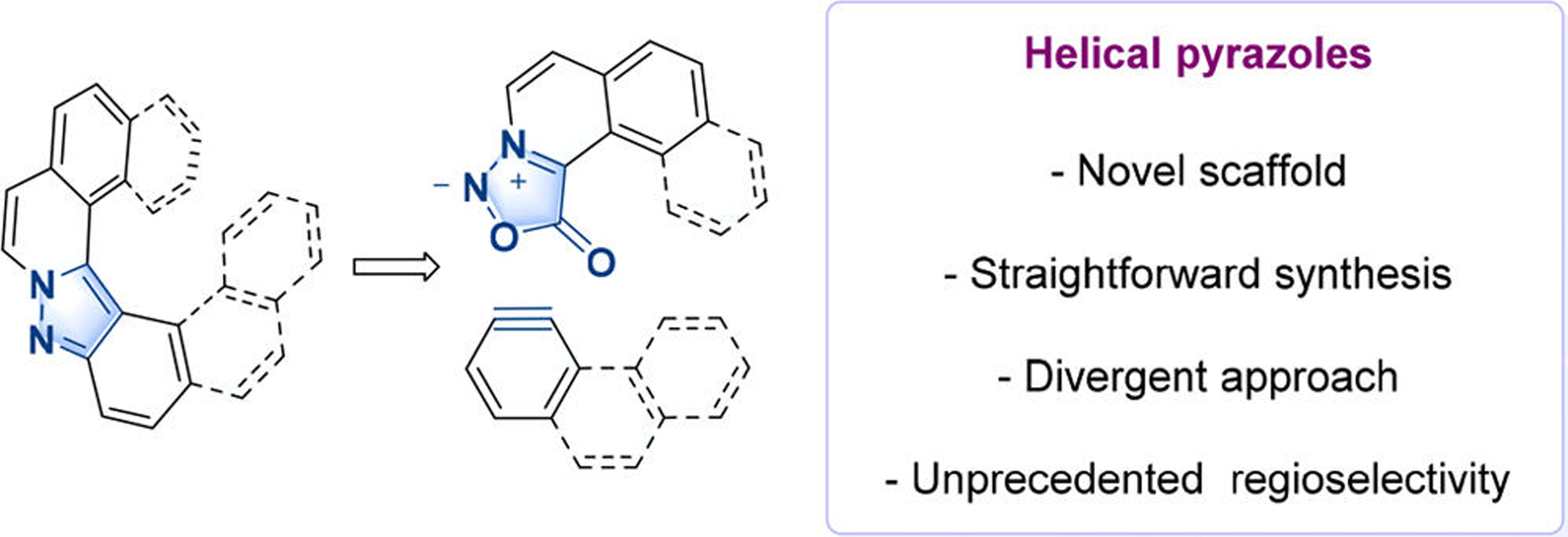

The first approach to pyrazole-containing helicenes via sydnone-aryne [3 + 2]-cycloaddition is described. An unprecedented regioselectivity in the cycloaddition step toward the more sterically constrained product was observed in the presence of extended aromatic scaffolds. DFT calculations enabled understanding the origin of this unexpected selectivity.

Ortho-fused aromatic rings belong to a class of helical-shaped molecules named helicenes.1 Since their discovery, these variegated aromatics have fascinated chemist practitioners due to their elegant architecture, inherent chirality, and structural complexity. Helical structures are particularly interesting, as they are found in many biomacromolecules inspiring chemists involved in the field of asymmetric catalysis,2 and their enhanced chiroptical properties have attracted much attention in material science.3 The presence of a heteroatom in the fused polycyclic system considerably alters the electronic structure and helps tune various optoelectrical properties.4 In particular, nitrogen-containing helicenes, including pyridine,5 pyrrole,6 pyrazine,7 and imidazolonium4a,8 have attracted much attention. Despite the broad interest in this family of compounds, synthetic access still remains challenging and often requires cumbersome multistep approaches.1 Ideally, the desired helical motif would be assembled in the last step of the sequence, thus enabling divergent opportunities for structure diversity. Sydnones are azomethine imines, well-known for their 1,3-dipolar-cycloadditions with linear and strained alkynes, generating pyrazoles, a pharmaceutically and agrochemically relevant heterocyclic scaffold.9 We reasoned that properly designed prohelical sydnones 3, bearing ortho-extended aromatic substitutions, would be suitable partners with arynes bearing an extended aromatic core.10 After cycloaddition, the subsequent loss of carbon dioxide would deliver the desired pyrazole-containing helicenes, a family of heterohelicenes so far unreported (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Design of pyrazole-based helicenes.

We now describe a novel disconnection allowing a direct access to a range of unreported helical pyrazoles, based on a key sydnone-aryne cycloaddition. In the process, we discovered a unique example of selective cycloaddition involving these mesoionic betaines in favor of the sterically hindered helical product and determined the reasons behind such selectivity with analysis of DFT calculations.

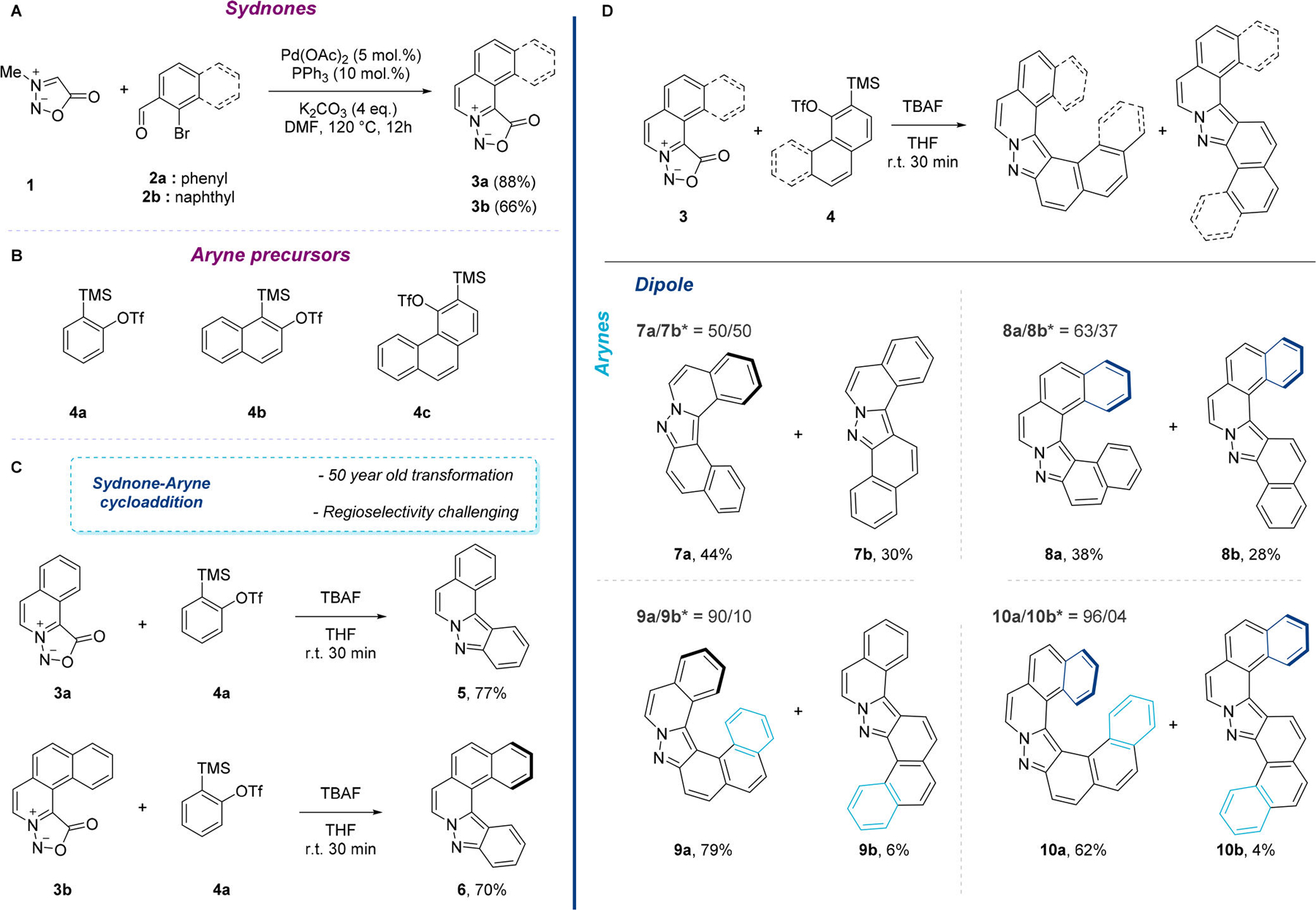

The implementation of this strategy relies on the prerequisite preparation of ortho-fused aromatic azomethine imine dipoles. N-Methyl sydnone 1 was identified as a key component to build up such ortho-aromatic structures. Readily available in two steps from commercial sarcosine, 1 provides a versatile handle for further derivatization. It was envisioned that metal catalyzed functionalization at the C4 position of the sydnone with 2-halobenzaldehyde would provide a key intermediate that might undergo intramolecular Knoevenagel condensation under basic conditions to give the desired product 3. Initial attempts showcased that the whole cascade could be performed in one single operation. Product 3a was first isolated in moderate yield together with the intermediate uncyclized aldehyde S3a.11 After some experimentation, it was found that, in the presence of catalytic amounts of Pd(OAc)2 and triphenylphosphine, with an excess of K2CO3 (4 equiv), the desired mesoionic compound 3a could be obtained in 88% yield. Similarly, the tetracyclic ortho-sydnone 3b could be isolated in 66% yield starting from the corresponding 1-bromo-2-naphthaldehyde (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) One-pot synthesis of polycyclic sydnones 3a and 3b; (B) aryne precursor; (C) synthesis of helical pyrazoles 5 and 6. (D) Synthesis of helical pyrazoles 7a, 8a, 9a, and 10a. * Isomer ratio was measured by 1H NMR of the crude mixture.

With a reliable access to the prerequisite ortho-fused aromatic azomethine imines 3a and 3b secured, we turned our attention to the key 1,3-dipolar-cycloaddition between polycyclic sydnones and aryne precursors. The sydnone-aryne cycloaddition is a 50 year old transformation pioneered by Gotthardt, Huisgen, and Knorr and later by Kato and Tsuge in 1974,12 but only recently the synthetic potential of this transformation has been studied in detail.13 Initially, we reacted sydnones 3a and 3b in the presence of silyl triflate 4a (1.5 equiv) and TBAF (1.5 equiv) at room temperature. As expected, the desired products 5 and 6 were isolated in good yields, 77% and 70%, respectively (Figure 2C). It is worth mentioning that 5 and 6 have been synthesized in only two steps from readily available N-methyl sydnone.14 The sequence could be extended to the ortho-fused 1,2-naphthyne precursor 4b (Figure 2D). In presence of tricyclic sydnone 3a the formation of the two possible cycloadducts, the desired hetero-[5]-helicene 7a and the S-shaped product 7b, was observed. As expected, no degree of selectivity was achieved and the cycloadducts were isolated in a 1:1 ratio and an overall 74% yield. The tetracylic sydnone 3b gave a low degree of selectivity in favor of the sterically hindered hetero-[6]-helicene 8a (8a/8b, ratio 63/37). The 1H NMR analysis of the two regioisomers showed well-resolved signals, which could be clearly assigned with COSY and NOESY measurements.11 Intrigued by this unexpected result, we investigated the reactivity of ortho-sydnones 3a and 3b in the presence of 3,4-phenanthryne precursor 4c (Figure 2D). This ortho-annulated aryne is particularly interesting because it should allow the formation of [6]- and [7]-helicenes. The reaction of 3a with 4c in the presence of TBAF in THF delivered a crude mixture with useful selectivity in favor of the helical product (crude 1H NMR ratio 90:10). After purification, the two components of the reaction could be isolated in 79% and 6% yield. The 2D-NMR measurements determined the identity of the major compound as the desired [6]-helical pyrazole 9a.15 When 4c was reacted in the presence of 3b, [7]-helicene 10a was isolated in 62% yield with high selectivity (10a/10b 96/4). Crystals of both isomers 10a and 10b were grown by slowly evaporating dichloromethane solutions, and the structures were determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 3A).

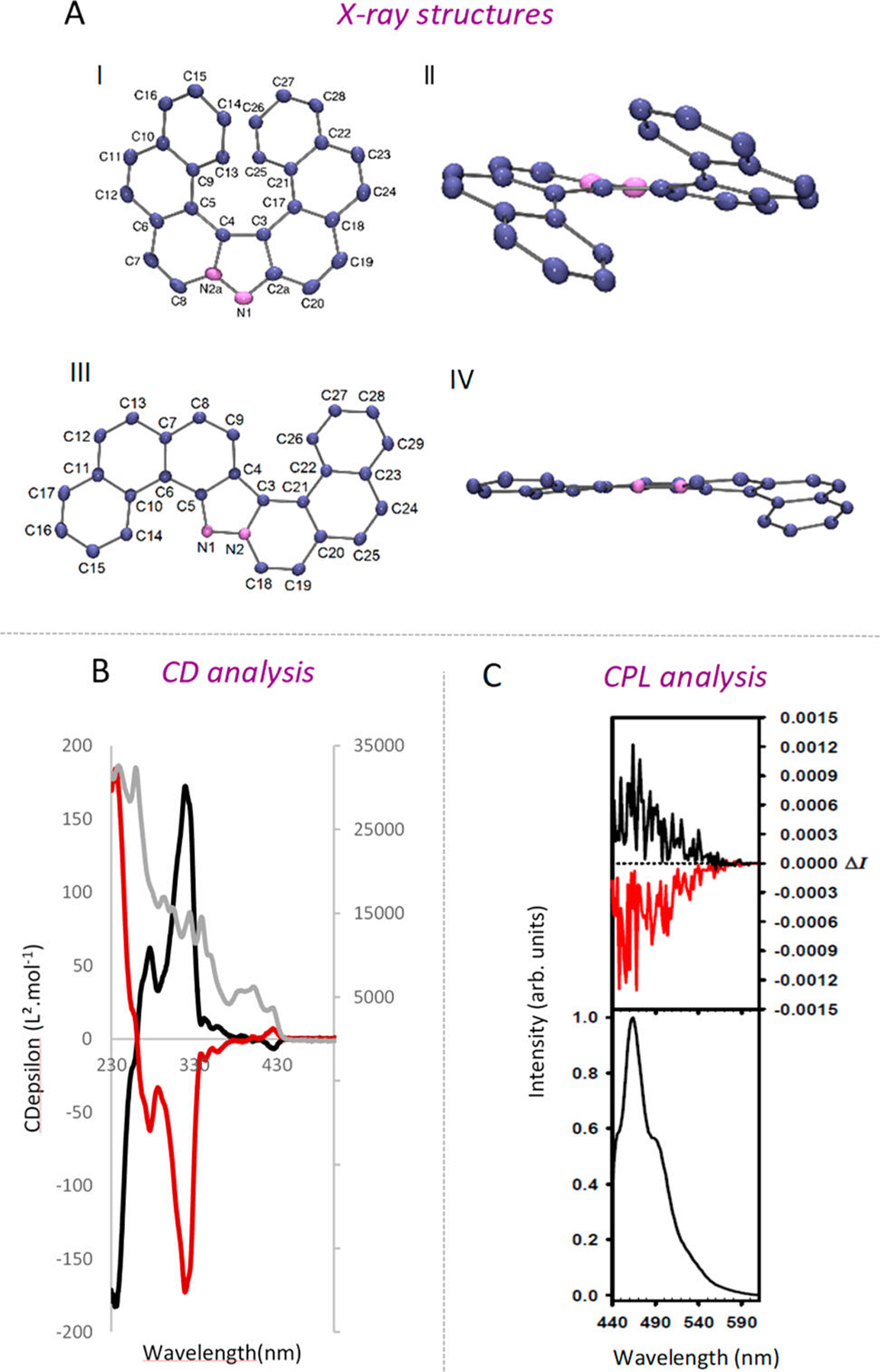

Figure 3.

(A) Molecular structure of 10a: (I) top and (II) side views. Molecular structure of 10b: (III) top and (IV) side views. Ellipsoids are set at 40% probability; hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. (B) UV (gray curve) and CD spectra of (+)-10a (black curve) and (−)-10a (red curve); (C) CPL (upper curve) and total luminescence (lower curves) spectra of (+)-10a (black curve) and (−)-10a (red curve) in degassed dichloromethane at 295 K, upon excitation at 430 nm. See Supporting Information for details.

The chiroptical properties of [7]-helicene 10a were subjected to a preliminary evaluation. Enantiomers of 10a were resolved from a racemic mixture using HPLC with a chiral-phase column.16 In Figure 3B, the circular dichrograms of the enantiopure samples are shown, which exhibit both positive and negative Cotton effects at 235 and 357 nm. The spectra of the enantiomers are mirror images of each other. The measurements conducted in degassed dichloromethane for the set of enantiomers led to the observation of a mirror-image CPL signal (Figure 3C). The glum values are −0.001 and +0.001 at about the maximum emission wavelength for 10a.17 These values are of the same order of magnitude as those for other examples of organic CPL-active helicenes.18 These results confirm that the solution of [7]-helicene 10a in degassed dichloromethane exhibits active CPL signals and also that the emitted light is polarized in opposite directions for the two enantiomeric forms for this helicene-like structure.

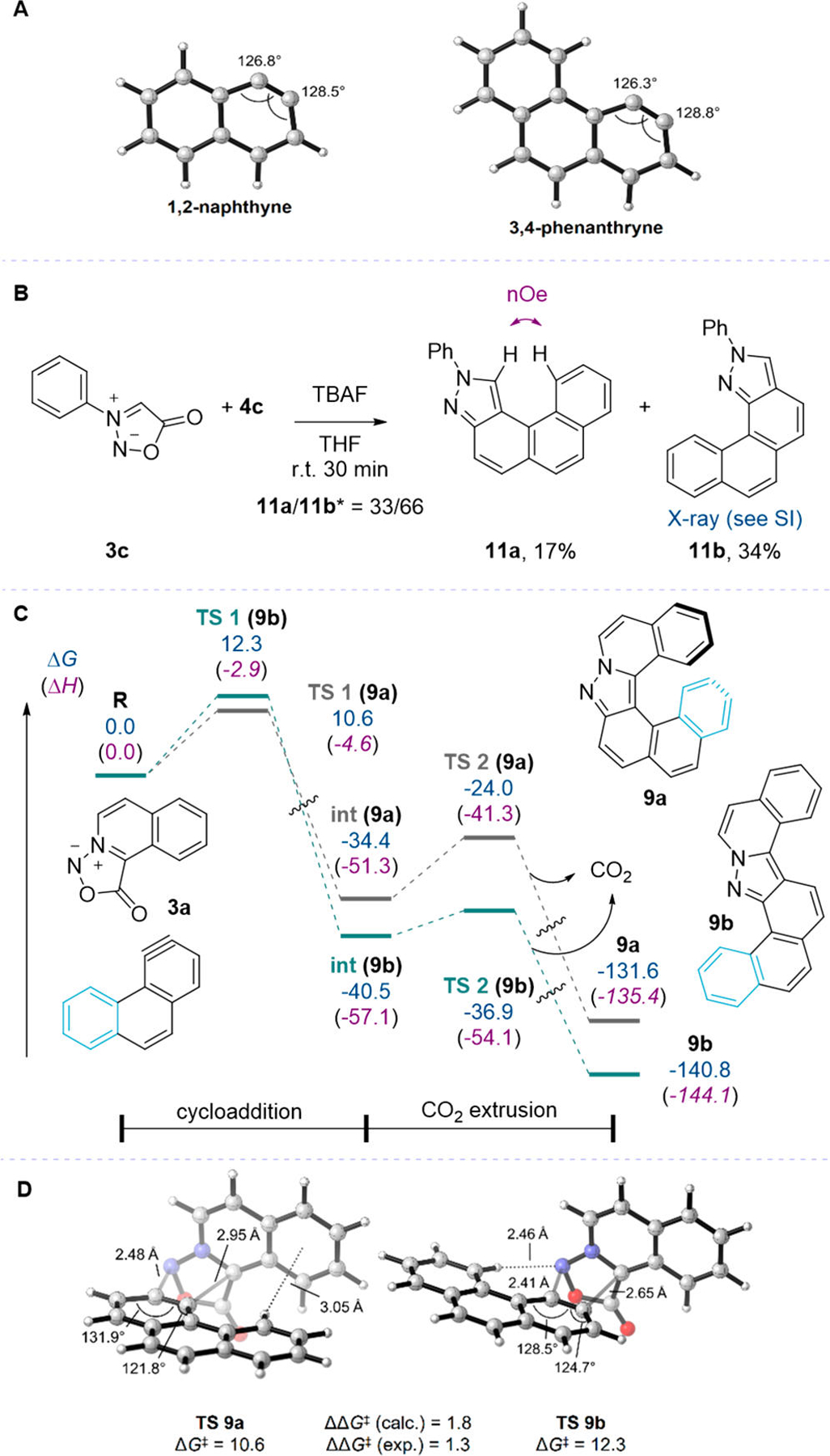

The selectivities observed for these sydnone-aryne cycloadditions were unexpected, given precedents in the literature. First, sydnones are known to be poorly regioselective in their cycloadditions with asymmetrical alkyne dipolarophiles.13,19–23 Moreover, the Houk–Garg distortion-based model to explain the preferred regioselectivity of attack of nucleophiles on strained alkynes,24 which is based on the difference in internal angles of the alkyne carbons, predicts low selectivity with 1,2-naphthyne or 3,4-phenanthryne, albeit in the observed direction. DFT optimizations of the two structures (M06–2X/6–31+G(d,p))11 reveal that the two aryne carbons have similar internal bond angles (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) DFT-optimized structures of polycyclic arynes derived from 4b and 4c. (B) Reaction between nonplanar N-phenyl sydnone 3c and 3,4-phenanthryne precursor 4c. * Isomer ratio was measured by 1H NMR of the crude mixture. (C) Energy profile for the reaction of 3a with 3,4-phenanthryne to form 9a or 9b. Free energies (enthalpies) are in kcal/mol and were obtained at the M06–2X/6–311+G(2d,2p)/SMD(THF)//M06–2X/6–31+G(d,p) level of theory. (D) Cycloaddition TSs leading to regioisomers 9a and 9b. M06–2X/6–311+G(2d,2p)/SMD(THF)//M06–2X/6–31+G(d,p). Free energies in kcal/mol.

In order to highlight whether the peculiar structure of sydnones 3a and 3b is responsible for the unusual selectivity, sydnone 3c was synthesized. As shown in Figure 4B, when N-phenyl sydnone 3c was reacted with 4c the opposite selectivity was observed (ratio 33:66 in favor of 11b).25 This result suggests that the origin of the selectivity might be related to the structure of the polycyclic sydnone itself. To understand the origins of such a dichotomy, we calculated the free energy profiles for the reactions of 3a–3c with both 1,2-naphthyne and 3,4-phenanthryne, using the same DFT method described above. Profiles for the reaction of 3a with 3,4-phenanthryne are shown in Figure 4C.11 In all cases examined, the regio-determining cycloaddition step is also rate-determining and fully irreversible, as the formation of the intermediate cycloadduct (int) is highly exergonic (ΔG = −33 to −58 kcal/mol). The CO2 extrusion step (TS 2) is then extremely facile and once again very exergonic. All cycloaddition transition states (TS 1) have very low activation barriers (ΔG‡ between 9 and 12 kcal/mol). Our calculations also quantitatively reproduce the experimental selectivities, that is formation of the helical regioisomer is predicted to be favored for sydnones 3a and 3b, but unfavored for 3c.

The TSs leading to the two regioisomers for the representative reaction of 3a with 3,4-phenanthryne are shown in Figure 4D. The TSs for the other pairs of reactants can be found in the Supporting Information (SI) and display similar arrangements. First, the TS leading to the major helical isomer is more asynchronous, with the shorter forming bond being between the more nucleophilic terminus of the azomethine imine of the sydnone and the more electrophilic (linear) carbon of the aryne.26 Indeed, for the fused sydnones 3a and 3b, the nitrogen atom bears more HOMO character than the carbon, while, for N-phenyl sydnone 3c, the opposite is found. Second, the forming bonds are fairly long, indicative of very early TSs, which are in accord with the high exergonicity of the cycloaddition steps and the Hammond postulate. Third, the major TS seems to benefit from stabilizing C–H⋯π interactions (also called face-to-edge π–π interactions) between the polycyclic backbones of the reactants, while the minor TS does not.27

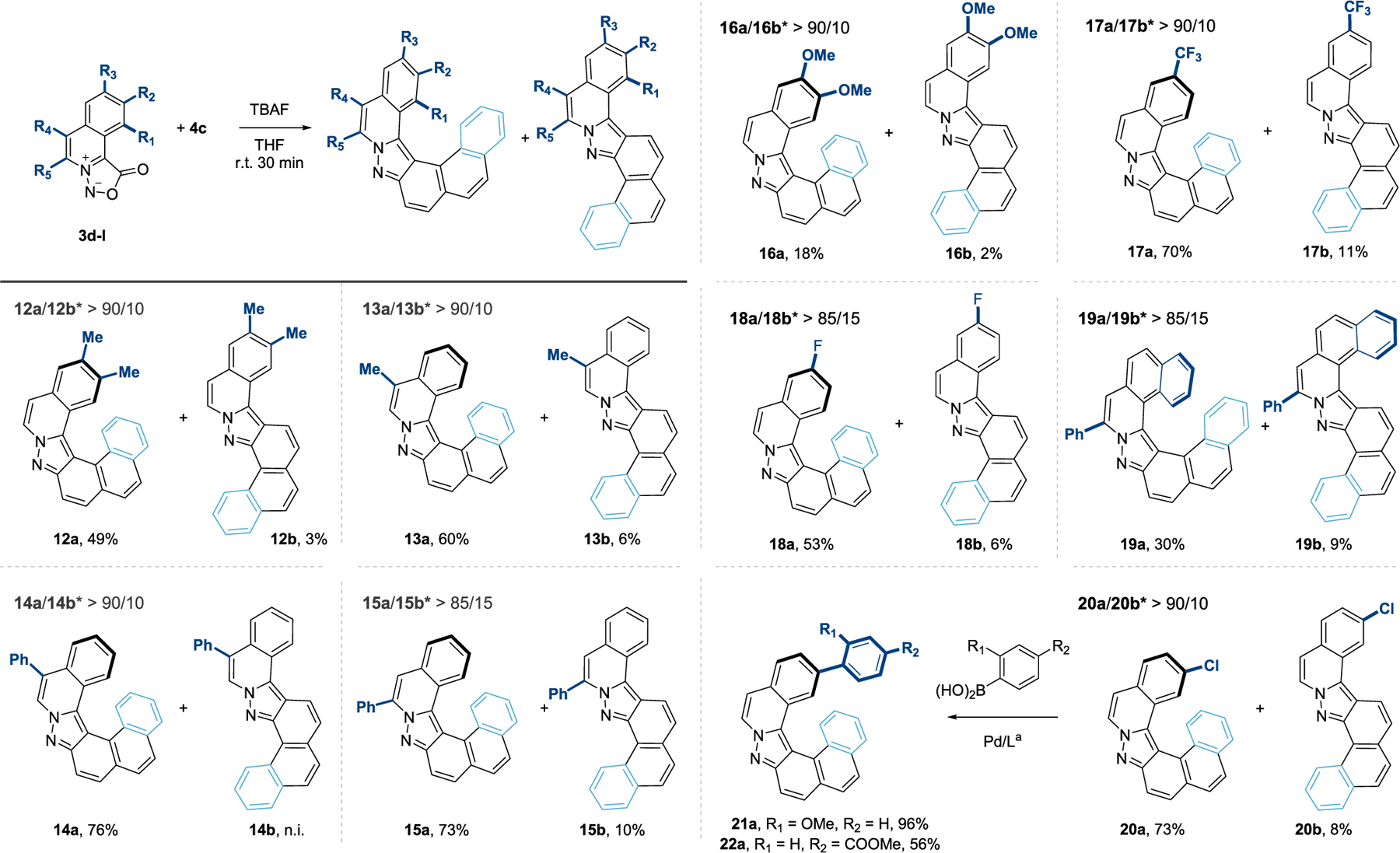

Distortion/interaction analysis28 confirms this behavior: as the TSs are so early, the reactants are barely distorted from their ground-state geometries, and total distortion energies are, at most, 4.0 kcal/mol. As such, even though the helical regioisomer of the cycloadducts and pyrazoles is more sterically encumbered and always higher in energy than the S-shape isomer, this effect is not important in TS 1 since the reactants are still far from each other. Conversely, interaction energies range from −7.4 to −12.4 kcal/mol, and are greater for the helical vs the S-shape regioisomer. In fact, for the six systems studied, the activation energies correlate with interaction energies, but have no correlation with distortion energies.11 To confirm the stabilization offered by the dispersive aromatic–aromatic interactions, we computed the binding energies of aromatic dimers in the same geometries as the helical TSs.11 For the four combinations evaluated, the binding energies were between −0.4 to −1.9 kcal/mol, demonstrating the stabilization offered by the C–H⋯π interactions for the helical TSs, in addition to the more favorable primary orbital interactions. Thus, the TSs that benefit from the most interactions are also earlier, further lowering the cost to distort the reactants. These results indicate that, with other very reactive partners, regioselective cycloadditions might be possible when interactions with polycyclic backbones are present. Indeed, when substituted sydnones 3d–3l were reacted with 4c, similar values of regioselectivity (>85/15) were observed in favor of the corresponding [6]- and [7]-helicenes 12a–20a (Figure 5). While the presence of electron-neutral and -withdrawing substituents on the sydnone does not affect the transformation, disubstituted electron-rich dipole 3h was poorly reactive and the desired [6]-helicene 16a was isolated in 18% yield.29 Derivative 20a with the presence of a chloride substituent offered a useful handle for further functionalization. Under catalytic conditions, the products of Sukuzi cross-coupling reaction 21a and 22a were isolated in 96% and 56% yield. This preliminary proof-of-concept showed the possibility to further monofunctionalize this helical scaffold by means of metal catalysis which could be of interest for potential applications.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of helical pyrazoles 12a–22a. * Isomer ratio was measured by 1H NMR of the crude mixture. n.i. = not isolated. a See Supporting Information for detailed conditions.

In summary, we have developed a method to access [4]-, [5]-, [6]-, and [7]-helicenes containing pyrazoles through sydnone 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. This process involves the design and synthesis of ortho-substituted polyaromatic sydnones, which are more nucleophilic than conventional ones, and highlights the first example of regioselective cycloaddition of such mesoionic dipoles with aryne derivatives. Calculations showed that primary orbital interactions and C–H⋯π dispersive interactions control the regioselectivity of this transformation. This reaction will ultimately provide a modular access to substituted derivatives and could be amenable to the synthesis of other helicenes families.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by CEA and ANR (ANR-17-CE07-0035-01) and the U.S. National Science Foundation (CHE-1361104). P.A.C. gratefully acknowledges the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Nature et Technologies for a postdoctoral fellowship. Computations were performed on the Hoffman2 cluster at UCLA. G.M. acknowledges the NIH Minority Biomedical Research Support (Grant 1 SC3 GM089589-08) and the Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award for financial support. The authors thank C. Chollet, E. Marcon, A. Goudet, S. Lebrequier, and D.-A. Buisson (DRF-JOLIOT-SCBM, CEA) for excellent analytical support. We wish to acknowledge Dr. P. Dauban (ICSN, CNRS, France) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b11465.

Experimental procedures and computational details NMR spectra for obtained compounds (PDF)

Crystallographic data for compounds 10a (CCDC 1544556), 10b (CCDC 1872990), and 11b(CCDC 1544557) (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Shen Y; Chen C-F Helicenes: synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 1463–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gingras M One hundred years of helicene chemistry. Part 1: non-stereoselective syntheses of carbohelicenes. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 968–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gingras M; Félix G; Peresutti R One hundred years of helicene chemistry. Part 2: stereoselective syntheses and chiral separations of carbohelicenes. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 1007–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gingras M One hundred years of helicene chemistry. Part 3: applications and properties of carbohelicenes. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 1051–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chen C-F; Shen Y Helicene Chemistry, From Synthesis to Applications, Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Takenaka N; Chen J; Captain B; Sarangthem RS; Chandrakumar A Helical Chiral 2-aminopyridinium ions: a new class of hydrogen bond donor Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 4536–4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aillard P; Voituriez A; Dova D; Cauteruccio S; Licandro E; Marinetti A Phosphathiahelicenes: synthesis and uses in enantioselective gold catalysis. Chem. - Eur. J 2014, 20, 12373–12376 and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) González-Fernández E; Nicholls LDM; Schaaf LD; Farés C; Lehmann CW; Alcarazo M Enantioselective synthesis of [6]carbohelicenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 1428–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ferreira M; Naulet G; Gallardo H; Dechambenoit P; Bock H; Durola F A Naphtho-fused double [7]helicene from a maleate-bridged Chrysene Trimer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 3379–3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Hatakeyama T; Hashimoto S; Oba T; Nakamura M Azaboradibenzo[6]helicene: carrier inversion induced by helical homochirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 19600–19603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang Y; da Costa RC; Fuchter MJ; Campbell AJ Circularly polarized light detection by a chiral organic semiconductor transistor. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Otani T; Tsuyuki A; Iwachi T; Someya S; Tateno K; Kawai H; Saito T; Kanyiva KS; Shibata T Facile two-step synthesis of 1,10-phenanthroline-derived polyaza[7]helicenes with high fluorescence and CPL efficiency. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3906–3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Collins SK; Vachon MP Unlocking the potential of thiaheterohelicenes: chemical synthesis as the key. Org. Biomol. Chem 2006, 4, 2518–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Míšek J; Teplý F; Stará IG; Tichý M; Šaman D; Císařová I; Vojtíšek P; Starý IA Straightforward route to helically chiral N-heteroaromatic compounds: practical synthesis of racemic 1,14-diaza[5]helicene and optically pure 1- and 2-aza[6]helicenes. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3188–3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Takenaka N; Sarangthem RS; Captain B Helical chiral pyridine N-oxides: a new family of asymmetric catalysts. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9708–9710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kaneko E; Matsumoto Y; Kamikawa K Synthesis of azahelicene N-oxide by palladium-catalyzed direct C–H annulation of a pendant (Z)-bromovinyl side chain. Chem. - Eur. J 2013, 19, 11837–11841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bosson J; Labrador GM; Pascal S; Miammay F-A; Yushchenko O; Li H; Bauffier L; Sojic N; Tovar RC; Muller G; Jacquemin D; Laurent AD; Guennic BL; Vauthey E; Lacour J Physicochemical and electronic properties of cationic [6]helicenes: from chemical and electrochemical stabilities to far-red (polarized) luminescence. Chem. - Eur. J 2016, 22, 18394–18403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Nakamura K; Furumi S; Takeuchi M; Shibuya T; Tanaka K Enantioselective synthesis and enhanced circularly polarized luminescence of S-shaped double azahelicenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 5555–5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nejedlý J; Šámal M; Rybáček J; Tobrmanová M; Szydlo F; Coudret C; Neumeier M; Vacek J; Chocholoušová JV; Buděšínský M; Šaman D; Bednárová L; Sieger L; Stará IG; Starý I Synthesis of long oxahelicenes by polycyclization in a flow reactor. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 5839–5843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Goto K; Yamaguchi R; Hiroto S; Ueno H; Kawai T; Shinokubo H Intermolecular oxidative annulation of 2-aminoanthracenes to diazaacenes and aza[7]helicenes. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10333–10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shi L; Liu Z; Dong G; Duan L; Qiu Y; Jia J; Guo W; Zhao D; Cui D; Tao X Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and application of a carbazole-based diaza[7]helicene in a deep-blue-emitting OLED. Chem. - Eur. J 2012, 18, 8092–8099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Upadhyay GM; Talele HR; Bedekar AV Synthesis and photophysical properties of aza[n]helicenes. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 7751–7759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Krzeszewski M; Kodama T; Espinoza EM; Vullev VI; Kubo T; Gryko DT Nonplanar butterfly-shaped π-expanded pyrrolopyrroles. Chem. - Eur. J 2016, 22, 16478–16488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sakamaki D; Kumano D; Yashima E; Seki S A Facile and versatile approach to double N-heterohelicenes: tandem oxidative CN couplings of N-heteroacenes via cruciform dimers. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5404–5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Čížková M; Šaman D; Koval D; Kašička V; Klepetářová B; Císařová I; Teplý F Modular Synthesis of Helicene-Like Compounds Based on the Imidazolium Motif. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2014, 2014, 5681–5685. [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Browne DL; Harrity JPA Recent developments in the chemistry of sydnones. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 553–568. [Google Scholar]; (b) Decuy-pére E; Plougastel L; Audisio D; Taran F Sydnone–lkyne cycloaddition: applications in synthesis and bioconjugation. Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 11515–11527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).For important pioneering work on helicenes formation by [4 + 2] cycloaddition of benzynes, see:; (a) del Mar Real M; Pérez Sestelo J; Sarandeses LA Inner–outer ring 1,3-bis(trimethylsilyloxy)-1,3-dienes as useful intermediates in the synthesis of helicenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 9111–9114. [Google Scholar]; (b) Truong T; Daugulis O Divergent reaction pathways for phenol arylation by arynes: synthesis of helicenes and 2-arylphenols. Chem. Sci 2013, 4, 531–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).See SI for additional details.

- (12).For the very first report, see:; (a) Gotthardt H; Huisgen R; Knorr R 1.3-Dipolare cycloadditionen, XXXVIII. Reaktionen der sydnone mit benz-in und mit einigen heteromehrfachbindungen. Chem. Ber 1968, 101, 1056–1058. For other pioneering reports, see: [Google Scholar]; (b) Nakazawa S; Kiyosawa T; Hirakawa K; Kato H Selectivity in the thermal and photochemical fragmentation of the cycloadduct from benzyne and a mesoionic thiazol-4-one. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1974, 621a. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kato H; Nakazawa S; Kiyosawa T; Hirakawa K Heterocycles by cycloaddition. Part II. Cycloaddition–extrusion reactions of five-membered mesoionic compounds with benzyne: prepartion of benz[c]azole and benzo[c]thiophen derivatives. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1976, 672–675. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tsuge O; Samura H The formation of 1H-dibenzo[b,g][1,4,5]triazapentalene from 2-(o-nitrophenyl)- and 2-(o-azidophenyl)-2H-indazole. Org. Prep. Proced. Int 1974, 6, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Wu C; Fang Y; Larock RC; Shi F Synthesis of 2H-indazoles by the [3 + 2] cycloaddition of arynes and sydnones. Org. Lett 2010, 12, 2234–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fang Y; Wu C; Larock RC; Shi F Synthesis of 2H-indazoles by the [3 + 2] dipolar cycloaddition of sydnones with arynes. J. Org. Chem 2011, 76, 8840–8851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Soares MIL; Nunes CM; Gomes CSB; Pinho e Melo TMVD Thiazolo[3,4-b]indazole-2,2-dioxides as masked extended dipoles: pericyclic reactions of benzodiazafulvenium methides. J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).For a previous synthesis of compound 5, see:; (a) Zhao J; Wu C; Li P; Ai W; Chen H; Wang C; Larock RC; Shi F Synthesis of pyrido[1,2-b]indazoles via aryne [3 + 2] cycloaddition with Ntosylpyridinium Imides. J. Org. Chem 2011, 76, 6837–6843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao J; Li P; Wu C; Chen H; Ai W; Sun R; Ren H; Larock RC; Shi F Aryne [3 + 2] cycloaddition with Nsulfonylpyridinium imides and in situ generated N-sulfonylisoquinolinium imides: a potential route to pyrido[1,2-b]indazoles and indazolo[3,2-a]isoquinolines. Org. Biomol. Chem 2012, 10, 1922–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zheng Q-Z; Feng P; Liang Y-F; Jiao N Pd-Catalyzed tandem C–H azidation and N–N bond formation of arylpyridines: a direct approach to pyrido[1,2-b]indazoles. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 4262–4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).In contrast to [6]-carbohelicenes, [6]-helicene 9a is not configurationally stable at room temperature. Computated racemization energy barrier is 22.5 kcal/mol (B3LYP/6–31G(d)). Enantiomers of 9a were resolved by chiral-phase HPLC, and a rapid racemization was observed. For additional information regarding the racemization barriers of other pyrazolohelicenes herein reported, see ref 11. For a nice overview on carbohelicenes racemization, see:; Barroso J; Cabellos JL; Pan S; Murillo F; Zarate Z; Fernandez-Herrera MA; Merino G Revisiting the racemization mechanism of helicenes. Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 188–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).The measured racemization barrier for pyrazolo[7]helicene 10a was found to be 32.7 kcal/mol. This value is in agreement with the calculated racemization energy barrier for 10a: 31.6 kcal/mol (B3LYP/6–31G(d)). See ref 11 for details.

- (17).The degree of CPL is given by the luminescence dissymmetry ratio, glum(λ) = 2ΔI/I = 2(IL − IR)/(IL + IR), where IL and IR refer, respectively, to the intensity of left and right circularly polarized emissions.

- (18).(a) Kaseyama T; Furumi S; Zhang X; Tanaka K; Takeuchi M Hierarchical assembly of a phthalhydrazide-functionalized helicene. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3684–3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sawada Y; Furumi S; Takai A; Takeuchi M; Noguchi K; Tanaka K Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis, crystal structures, and photophysical properties of helically chiral 1,1′-bitriphenylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 4080–4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shen C; Anger E; Srebro M; Vanthuyne N; Deol KK; Jefferson TD; Muller G; Williams JAG; Toupet L; Roussel C; Autschbach J; Réau R; Crassous J Straightforward access to mono- and bis-cycloplatinated helicenes displaying circularly polarized phosphorescence by using crystallization resolution methods. Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 1915–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).We are aware of only two single examples of regioselective sydnone-aryne cycloaddition (>85/15), in the presence of 3-silylbenzyne:; (a) Ikawa T; Masuda S; Takagi A; Akai S 1,3- and 1,4-Benzdiyne equivalents for regioselective synthesis of polycyclic heterocycles. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 5206–5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ikawa T; Masuda S; Nakajima H; Akai S 2-(Trimethylsilyl)phenyl trimethylsilyl ethers as stable and readily accessible benzyne precursors. J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 4242–4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Houk KN; Sims J; Duke RE; Strozier RW; George JK Frontier molecular orbitals of 1,3 dipoles and dipolarophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 7287–7301. [Google Scholar]; (b) Houk KN; Sims J; Watts CR; Luskus LJ Origin of reactivity, regioselectivity, and periselectivity in 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 7301–7315. [Google Scholar]; (c) Padwa A; Burgess EM; Gingrich HL; Roush DM On the problem of regioselectivity in the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of munchnones and sydnones with acetylenic dipolarophiles. J. Org. Chem 1982, 47, 786–791. [Google Scholar]

- (21).McMahon TC; Medina JM; Yang Y-F; Simmons BJ; Houk KN; Garg NK Generation and regioselective trapping of a 3,4-piperidyne for the synthesis of functionalized heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 4082–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Shah TK; Medina JM; Garg NK Expanding the strained alkyne toolbox: generation and utility of oxygen-containing strained alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 4948–4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Noteworthy, in the presence of unsymmetric cyclooctynes, sydnones have been reported to deliver a 1:1 mixture of regioisomers:; Narayanam MK; Liang Y; Houk KN; Murphy JM Discovery of new mutually orthogonal bioorthogonal cycloaddition pairs through computational screening. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 1257–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).(a) Cheong PH-Y; Paton RS; Bronner SM; Im G-YJ; Garg NK; Houk KN Indolyne and aryne distortions and nucleophilic regioselectivites. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 1267–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Medina JM; Mackey JL; Garg NK; Houk KN The role of aryne distortions, steric effects, and charges in regioselectivities of aryne reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 15798–15805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).The nature of pyrazoles 11a and 11b was unambiguously established by NOE and X-ray crystallography (see SI for details).

- (26).In all cases, the reactions are HOMO (sydnone) – LUMO (aryne) controlled. See SI for details.

- (27).For a review on aromatic interactions as control elements in stereoselective reactions, see:; Krenske EH; Houk KN Aromatic interactions as control elements in stereoselective organic reactions. Acc. Chem. Res 2013, 46, 979–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bickelhaupt FM; Houk KN Analyzing reaction rates with the distortion/interaction-activation strain model. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10070–10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Unreacted sydnone 3h was preset in the reaction crude even after a prolonged reaction time.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.