Abstract

Background Advances in genetic screening can identify patients at high risk for common genetic conditions early in pregnancy and can facilitate early diagnosis and early abortion. Less common abnormalities might only be diagnosed with invasive testing is performed after structural abnormalities are identified.

Objective Our objective was to compare gestational age (GA) at diagnosis and abortion for genetic abnormalities identified based on screening with abnormalities that were not discovered after screening.

Study Design All prenatal diagnostic procedures from 2012 to 2017 were reviewed, and singleton pregnancies terminated following diagnosis of genetic abnormalities were identified. Cases diagnosed as the result of screening tests were compared with remaining cases. Conditions were considered “screened for” if they can be suspected by cell-free DNA testing, biochemistry, carrier screening, or if the patient was a known carrier of a single-gene disorder. When abnormal karyotype, microarray, or Noonan's syndrome was associated with abnormal NT, these cases were considered “screened for.” GA at abortion was the primary outcome. Fisher's exact test and Mann–Whitney's U test were used for statistical comparison.

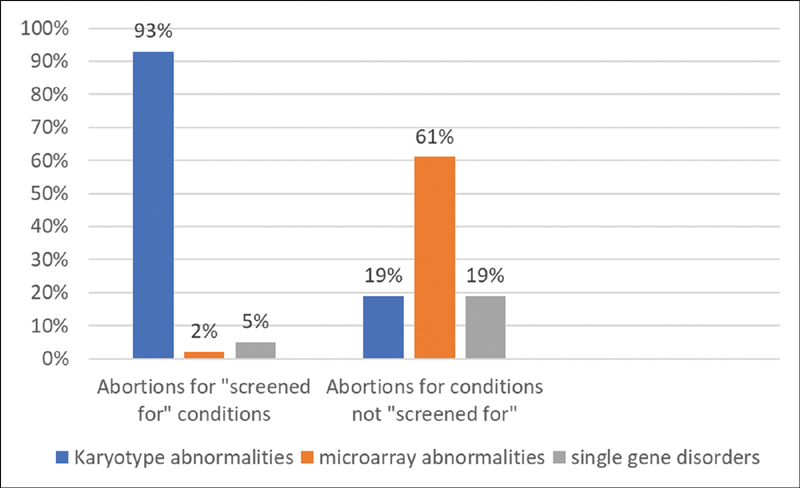

Results In this study, 268 cases were included. A total of 227 (85%) of abortions were performed for “screened for” disorders, with 210 (93%) of these for karyotype abnormalities, 5 (2%) for microarray abnormalities, and 12 (5%) for single-gene disorders. Forty-one (15%) of abortions were performed for conditions not included in screening, with 8 (19%) of those for karyotype abnormalities, 25 (61%) for microarray abnormalities, and 8 (19%) for single-gene disorders. Invasive testing and abortion occurred at earlier median GA for those with conditions that were screened for: 12 2/7 versus 15 5/7 weeks, p ≤0.001 and 13 5/7 versus 20 0/7 weeks; p ≤0.001.

Conclusion Most abortions were for abnormalities that can be suspected early in pregnancy. As many structural abnormalities associated with rare conditions are not identifiable until the mid-trimester, prenatal diagnosis and abortion occurred significantly later. Physicians and patients should be aware of the limitations of genetic screening.

Keywords: abortion, amniocentesis, chorionic villi sampling, chromosomal microarray, prenatal genetic screening, single gene disorders

About 1 in every 150 live births has a chromosomal abnormality that causes an abnormal phenotype in the fetus or neonate. 1 Prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic testing provide pregnant women with information that could lead some to consider terminating the pregnancy. Advances in prenatal genetic screening have enabled common chromosomal abnormalities to be suspected in the first trimester, with diagnosis achievable at <14 weeks' gestation in most cases.

Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have stated that prenatal genetic screening and invasive testing by chorionic villi sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis should be offered to any pregnant woman, regardless of age and risk factors. 2 3 4 ACOG and SMFM have also recommended that with appropriate genetic counseling, chromosomal microarray (CMA) testing can be offered to all women undergoing diagnostic testing, especially in cases in which a fetal structural abnormality is detected. 5 6 Another recent change in practice is the availability of expanded carrier screening for both parents, beyond screening for cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, fragile X permutation, and conditions related to ethnicity when appropriate. 7 8 When parents are found to be carriers of certain single-gene disorders, advances in sequencing techniques have made it possible to achieve early prenatal diagnosis through invasive testing. 9

These advances have enabled patients to not only have earlier genetic diagnosis but also earlier abortion when desired. A 2017 series conducted from 2004 to 2014 found that for women undergoing abortion for fetal aneuploidy, median gestational age (GA) at the time of abortion decreased from 19 to 14 weeks, but women who underwent abortion for fetal structural abnormalities did not have a decrease in GA at the time of abortion. 10 A study performed at our institution looking at timing of prenatal diagnosis and abortion over a 10-year period found that, with the increasing use of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) testing, the GA at prenatal diagnosis and abortion for Turner's syndrome (TS) 21 declined significantly, with most cases diagnosed in the first trimester in the most recent study interval. 11 Abortions performed in the first trimester or early second trimester are technically easier to perform, are less time consuming, and carry less risk for the patient. 12

Although advances in screening have led to earlier diagnosis and abortion, we cannot screen for all genetic conditions associated with abnormal development. In some cases, prenatal diagnosis occurs only after a structural abnormality is detected on ultrasound, often not until the second trimester. Other abnormalities, including copy number variants, may not be associated with any ultrasound findings, and may only be detected in “low-risk” patients who elect to undergo amniocentesis or CVS to have access to the best information.

In this study, our objective was to compare the GA at diagnosis and abortion for genetic abnormalities amenable to routine prenatal screening versus genetic abnormalities that cannot be suspected based on available screening tests. Our hypothesis was that the GAs at prenatal diagnosis and abortion are greater for uncommon genetic abnormalities not likely to be picked up by prenatal genetic screening.

Methods

This was a retrospective database review of all prenatal diagnostic procedures performed in our ultrasound unit from 2012 to 2017. This study was approved by our institution's Institutional Review Board. Patients who underwent abortion after diagnosis of a genetic abnormality were included. We compared cases of abortion with a diagnosis of a condition screened for during pregnancy with the remaining cases. Our primary outcome was GA at abortion. We only included patients who chose to terminate their pregnancy as timing of prenatal diagnosis is most relevant in these patients.

Cases included in the “screened” group included those with prenatal diagnoses of common chromosomal abnormalities (trisomies 21, 18, and 13, triploidy, and sex chromosome abnormalities including 45X, 47XXY, 47XXX, and 47XYY), conditions identified through parental carrier screening, and cases in which prenatal testing was done due to a known family history. Screening tests included nuchal translucency (NT), first- and second-trimester serum screening tests, and cfDNA testing. As NT is used as a nonspecific genetic screening tool, any chromosomal abnormality, CMA abnormality, or mutation associated with Noonan's syndrome diagnosed after abnormal NT was categorized with the “screened” group. All other cases which involved genetic conditions that could not have been suspected based on aneuploidy screening, carrier testing, or family history were categorized as “unscreened.” CMA abnormalities were included only when they were considered pathogenic, not if they were considered variants of unknown significance. When invasive testing was performed without a positive screening test (most commonly in women age ≥35 years), cases with a diagnosis of common chromosomal abnormalities were assigned to the “screened” group,, as screening tests with high sensitivity are available for these conditions. Group assignment was made based on the genetic diagnosis, and not based on the specific screening tests performed on individual patients. For example, patients who were screened with NT and cfDNA that was normal but had a diagnosis of a CMA abnormality when amniocentesis was performed following an abnormal ultrasound finding were assigned to the “unscreened” group. Patients who underwent CVS without prior screening and had a common autosomal trisomy diagnosed were assigned to the “screened” group. All patients with abnormal genetic results were counseled by genetic counselors, with the option of referral to pediatric geneticists if requested.

Fisher's exact test and Mann–Whitney U test were used for statistical comparison. A p -value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous data are expressed as median (interquartile range).

Results

There were 268 cases of abortion included in the study, and all patients underwent diagnostic testing via CVS or amniocentesis. A total of 227 (85%) were performed for genetic disorders considered to be “screened.” Most abortions for “screened” conditions were performed due to karyotype abnormalities (93%). The remainder was performed for single-gene disorders (5%) and CMA abnormalities (2%). The most common karyotype abnormality was TS 21 (46%) followed by TS 18 (16%), TS 13 (10%), and TS (4%).

The remaining 41 cases (15%) were abortions performed for genetic disorders that were not detected as a result of any screening process. The most common type of genetic finding in this group was CMA abnormalities (61%), followed by uncommon karyotype abnormalities (19%) and single-gene disorders (19%) ( Fig. 1 ). Abnormal sonographic findings were found in 19 (46%) of these cases overall, and were significantly more common in cases with single-gene disorders (100%) compared with CMA abnormalities (40%) or chromosomal abnormalities (11%) ( p < 0.001) ( Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Types of genetic disorders in the two study groups: abortions performed for “screened for” conditions and abortions performed for not “screened for” conditions.

Table 1. Genetic abnormalities of abortions performed for disorders that were not screened for.

| Unscreened genetic abnormalities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound findings | GA abortion (wk) | |

| Karyotype abnormality ( N = 8) | ||

| Mosaic TS 8 | None | 19 6/7 |

| Mosaic TS 8 | None | 19 2/7 |

| Mosaic TS 9 | None | 17 4/7 |

| Mosaic TS 9 | None | 17 2/7 |

| Mosaic TS 16 | None | 20 0/7 |

| Mosaic TS | None | 14 0/7 |

| Mosaic tetraploid/diploid | Micrognathia, bilateral clubfoot, echogenic kidneys | 14 5/7 |

| Mosaic tetraploidy | None | 18 0/7 |

| CMA finding ( N = 25) | ||

| Terminal mosaic deletion of 4p and terminal mosaic duplication of 10q | None | 13 2/7 |

| Isodicentric chromosome 14 | None | 16 2/7 |

| Ring chromosome 18 | None | 13 2/7 |

| Pericentric inversion of Y | None | 11 0/7 |

| Balanced transl 2 and 10 | None | 17 4/7 |

| Duplication chromo 10 | None | 14 0/7 |

| Unbalanced transl 8 and 21 | None | 13 2/7 |

| Del 9q34.3 (Kleefstra's syndrome) | Choroid plexus cysts, echogenic bowel, bilateral renal pyelectasis, absent nasal bone | 22 3/7 |

| Unbalanced transl 21q and 10q | Agenesis of corpus callosum, bilateral cleft lip | 23 0/7 |

| 5p duplication | Bilateral clubfoot | 23 0/7 |

| Duplication of chromosome 3, UPD chromosome 12 | Lagging growth, inferior cerebellar vermian agenesis | 22 5/7 |

| 11p deletion (WAGR syndrome) | Ambiguous genitalia | 22 2/7 |

| Unbalanced recombinant chromosome 16 | Bilateral clubfoot, cardiac abnormality, lagging growth | 25 4/7 |

| 22q11 deletion | Cardiac abnormality (truncus arteriosus) | 21 0/7 |

| Chromosome 15 duplication | Unilateral preaxial polydactyly | 23 0/7 |

| UPD chromosome 4 | Ventriculomegaly, lagging growth (MRI: intracranial hemorrhage) | 22 2/7 |

| 16p11 duplication | None | 19 2/7 |

| Chromosome 7 deletion | None | 22 0/7 |

| 22q duplication | None | 13 3/7 |

| 17q12 duplication | None | 22 5/7 |

| Mosaic interstitial deletion of 11Q12 | None | 18 5/7 |

| Interstitial deletion of homolog of chromosome 1 | None | 23 4/7 |

| Mosaic duplication chromosome 11 | None | 13 2/7 |

| Single-gene disorder ( N = 8) | ||

| FGR2 mutation (Apert's syndrome) | Syndactyly, brain abnormalities | 22 4/7 |

| FOXC2 mutation | Pedal edema | 21 0/7 |

| TD1 mutation (skeletal dysplasia) | Severe micromelia, bowing | 17 5/7 |

| TSC1 mutation (tuberous sclerosis) | Cardiac rhabdomyomas | 23 4/7 |

| FGR mutation (skeletal dysplasia) | Short long bones, lagging growth | 30 0/7, a |

| TSC1 mutation (tuberous sclerosis) | Cardiac rhabdomyomas | 32 5/7, a |

| TD2 mutation (thanatophoric dysplasia) | Micromelia, bilateral clubfoot | 20 0/7 |

| FGR3 mutation (thanatophoric dysplasia) | Short long bones, bowing, bell-shaped chest | 16 2/7 |

Abbreviations: CMA, chromosomal microarray; GA, gestational age; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TS, Turner's syndrome.

In these cases, abortion was delayed due to twin pregnancy.

There were 31 women (12%) who either had negative screening or had no screening for chromosomal abnormalities, with the listed indication for invasive testing as “advanced maternal age” for 25 (80.6%) of them. The median age in this group was 37 years. CVS was performed in 18 of these cases (58%) and amniocentesis in 13 (42%). Common chromosomal abnormalities were identified in nine cases, and assigned to the “screened” group. Of these 31 women, 22 (71%) were in the unscreened group, and copy number variants were detected in most of these cases (82%).

Invasive testing by CVS or amniocentesis and abortion occurred at earlier median GA for those with conditions that were screened for: 12 2/7 versus 15 5/7 weeks ( p ≤0.001) and 13 5/7 versus 20 0/7 weeks ( p ≤0.001). The median procedure-to-abortion interval was significantly longer in the cases of abortions performed for conditions in the “unscreened” group compared with the screened group (1 2/7 vs. 3 0/7 weeks, p < 0.001) ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. GA at the time of invasive procedure and abortion.

| Abortions performed for abnormalities that were screened for | Abortions performed for abnormalities that were not screened for | p -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (y, IQR) | 37 (34–40) | 35 (33–39) | 0.225 |

| GA at invasive procedure (wk) | 12 2/7 (11 5/7 –12 6/7 ) | 15 5/7 (12 1/7 –19 1/7 ) | <0.001 |

| GA at abortion (wk) | 13 5/7 (13 0/7 –15 1/7 ) | 20 0/7 (15 0/7 –22 5/7 ) | <0.001 |

| Procedure-to-abortion interval (wk) | 1 2/7 (0 6/7 –2 0/7 ) | 3 0/7 (1 4/7 –5 4/7 ) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: GA, gestational age; IQR, interquartile range.

Note : Data represented as median (interquartile range).

There were 27 abortions performed at ≥20 weeks' gestation, representing 10% of women terminating pregnancies due to genetic abnormalities. Of these, 19 (70%) were in the “unscreened” group, representing nearly half of the cohort that were not screened for the genetic abnormality detected. These included 12 (63%) CMA abnormalities, 6 (32%) single-gene disorders, and 1 (5%) karyotype abnormality. In the eight cases of abortion performed ≥20 weeks' gestation in the “screened” group, three (38%) were performed for TS 21, two (25%) for Noonan's syndrome, two (25%) for TS 18, and one (12%) for TS 13. Of the five chromosomal abnormalities in the “screened” group, four were for autosomal trisomy with false-negative screening, and one entered prenatal care at 17 weeks and therefore did not have first-trimester screening.

Discussion

In our population, prenatal diagnosis and abortion for genetic conditions amenable to screening occurred primarily in the first and early second trimesters. In contrast, prenatal diagnosis and abortions performed for abnormalities that were not screened for occurred at significantly later GAs, with abortion occurring at a median GA of 20 weeks. The interval between diagnostic procedure and abortion was also significantly longer for unscreened conditions, which is likely to reflect the increased time for laboratories to complete CMA and mutation testing. It is also likely that the lack of a clear phenotype associated with many CMA findings contributed to this longer interval, as patients may have sought genetic counseling and taken longer to reach a decision to terminate the pregnancy.

Our results are consistent with other studies that have demonstrated that as our ability to screen for the most common genetic abnormalities advances, the GA at the time of abortion has significantly declined. In those with conditions not detected by screening, ultrasound played an important role. Nearly half of the genetic conditions diagnosed in the “unscreened” cohort, including all with single-gene disorders, had structural abnormalities identified by ultrasound. In patients who would consider terminating a pregnancy for structural or genetic abnormalities, ultrasound earlier in the second trimester could lead to earlier prenatal diagnosis and abortion. This is especially important when there are strict GA limits on abortion, as CMA or single-gene disorder testing can take weeks to complete. Our results also suggest that a more detailed first-trimester ultrasound, which is more frequently performed in countries outside of the United States, may be able to diagnose major anomalies even earlier in gestation. A systematic review and meta-analysis recently found that up to 60% of fetal anomalies can be detected in the first trimester, which suggests that the development of international protocols with standard anatomic views can be undertaken to optimize first-trimester anomaly detection. 13 The detection of first-trimester fetal anomalies would likely result in earlier invasive testing and, subsequently, abortion at an earlier GA.

Some patients may consider invasive testing with normal screening results or without any screening. In our patients, 12% of abortions for fetal genetic conditions were in women without abnormal screening, and CMA abnormality was the most common type of abnormality. Most of these cases did not have ultrasound abnormalities. We practice in the northeast part of the country, where the rate of abortion is one of the highest in the country. 14 This may explain why many of the patients in our population seek invasive testing, often with the intent to terminate a genetically abnormal pregnancy. This may help explain why there were a significant amount of patients in our study who underwent invasive testing with no risk factors for having a genetically abnormal fetus. It is important to counsel patients about the limitations of genetic screening, and the fact that many conditions will not have sonographic findings but may still be associated with an abnormal phenotype. A large multicenter study identified a 1.3% rate of pathogenic or potentially pathogenic copy number variant in women undergoing invasive testing for “advanced maternal age.” As CMA abnormalities are not known to be age related, this may reflect the risk in a general population. 15 Patients who may be considered “low risk” for a genetic abnormality should not be discouraged from undergoing invasive testing in pursuit of more information. If a patient who would consider abortion is intent on undergoing invasive testing, CVS should be recommended to achieve the earliest possible diagnosis, as diagnosing and evaluating copy number variants are a longer process compared with common chromosomal abnormalities.

One of the strengths of this study was that it only included patients with a prenatal genetic diagnosis who chose to terminate the pregnancy. Thus, we did not need to speculate about the clinical impact of prenatal diagnosis in individual patients. The fact that patients in this study had their prenatal screening for chromosomal abnormalities, prenatal care, and pregnancy terminations at our institution enabled us to obtain precise information about the timing of prenatal diagnosis and abortion. These are clinically relevant outcomes, due to clear advantages in safety and availability of earlier abortion.

A limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which limited our ability to evaluate reasons for variation in decisions regarding timing of diagnosis and abortion between individuals. It is possible that a patient and/or physician's personal beliefs may have contributed to the delay between genetic diagnosis and abortion, and this information may not be reflected in the medical record. The study design is also a potential source of selection bias. Women who did not undergo a termination of pregnancy following the diagnosis of a genetic abnormality were not included, and these cases are not necessarily representative of all prenatally detected fetal genetic abnormalities. Another limitation is that our study does not include patients in whom genetic conditions were not identified, and we thus cannot determine the efficacy of prenatal screening and diagnosis in identifying all clinically significant genetic conditions. As most abnormalities in women without an abnormal screening test were in the “unscreened” group, it is likely that we are underestimating the true genetic disease burden attributable to uncommon conditions. Higher rates of “elective” CVS or amniocentesis in low-risk women are more likely to detect “unscreened” conditions such as CMA abnormalities.

In summary, our study highlights the achievements of prenatal screening for common chromosomal abnormalities as well as conditions identified by carrier testing, while also illustrating fact that a significant proportion of conditions not amenable to screening are unlikely to be diagnosed early in pregnancy. As some pathogenic conditions may not be suspected based on screening or ultrasound, any woman who might consider abortion for a genetic condition should consider invasive testing.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nussbaum R L, McInnes R R, Willard H F. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. Principles of clinical cytogenetics and genome analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Practice Bulletin No. 163 Summary: screening for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(05):979–981. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.et al. SMFM statement: clarification of recommendations regarding cell-free DNA aneuploidy screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(06):753–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.et al. Prenatal aneuploidy screening using cell-free DNA. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(06):711–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Microarrays and next-generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(06):262–268. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dugoff L, Norton M E, Kuller J A. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(04):B2–B9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics.Committee opinion no. 690: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine Obstetric Gynecol 201712903e35–e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics.Carrier screening for genetic conditions Obstet Gynecol 201712903e41–e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACOG Technology Assessment in Obstetrics and Gynecology No 14:Modern genetics in obstetrics and gynecology Obstet Gynecol 2018123e143–e168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis A R, Horvath S K, Castaño P M. Trends in gestational age at time of surgical abortion for fetal aneuploidy and structural abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(03):2780–2.78E7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hume H, Chasen S T. Trends in timing of prenatal diagnosis and abortion for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(04):5450–5.45E6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 135: second-trimester abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(06):1394–1406. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000431056.79334.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karim J N, Roberts N W, Salomon L J, Papageorghiou A T. Systematic review of first-trimester ultrasound screening for detection of fetal structural anomalies and factors that affect screening performance. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(04):429–441. doi: 10.1002/uog.17246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones R K, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2014. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(01):17–27. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wapner R J, Martin C L, Levy B et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2175–2184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]